ABSTRACT

The aim of this paper is to offer an empirically grounded conceptualization of the dialogical relationship between spatial planning and place branding in the context of regionalization. The analysis displays the discursive nature of such relationship by highlighting the intertwining of spatial planning with place branding as strategic actions devoted to, and included in, regional development processes. The analysis is based on two cases in Sweden. The first is linked to the emergence of the brand ‘Stockholm, the Capital of Scandinavia’, and the other is linked to the emergence of the brand ‘Swedish Lapland’. By combining data collected longitudinally, these cases represent two contrasting examples of dialogical relationships that materialize through two distinct yet somehow similar strategic processes of regionalization. Based on the two cases, the paper presents and discusses an empirically driven, albeit conceptual, model that highlights the dialogical relationship of regionalization as regional strategic policy and points out its spatial and political evolutionary features.

Introduction

Since the 1990s, the discourse of regionalization in Europe has affected the European Union landscape in terms of regional development initiatives. Regionalization, formulated as discourse about strategic policy for political integration and socio-economic development, is based on the notion that regions are important geographical entities that should foster endogenous growth and thus create stronger regions and achieve development and cohesion (Camagni & Capello, Citation2013). The narrative included in the European discourse on regionalization is also linked to an overall strategic and global orientation that creates a framework in which places and regions profile themselves against each other, if not in competition then in the pursuit of investments and tourists on a world market (Berg, Linde-Larsen, & Löfgren, Citation2002; Ek, Citation2005). Such a framework may be seen as being designed in relation to a neo-liberal development discourse of competition on a global scale, where places and regions participate in an ongoing struggle for mobile capital and mobile people (Hall, Citation2005; Harvey, Citation1989; Meethan, Citation2001).

The framework, translated as EU policy reform, despite containing a common model of proposed knowledge-intensive growth, stresses the importance of identifying regional strengths such as technological domains and industry sectors for the local economy (Camagni & Capello, Citation2013). The process of regionalization through such a framework has ‘trickled-down’ to regions as a form of normative strategic policy (see Swyngedouw, Moulaert, & Rodriguez, Citation2002). The overall aim of all this has been to design a region’s own policy and planning documents, such as regional innovation strategies and regional master plans, all while following a common narrative as presented in the common EU framework of regional policy development.

The implementation of such a framework in Swedish regions has followed a path similar to other places in Europe, leading to a focus on specific industrial sectors defined and prioritized by policy makers, still with the specificity of a major burden on local political processes and formal decision-making in municipalities. A peculiarity of the Swedish – as well as the general ‘Nordic’– approach to regional development policy is that not only are the processes of defining and communicating the assets and potential for innovation and economic growth in a specific region evolving into both planning and branding strategies, but, more crucially, the importance of the regional level for development, identity, and territorial assets is much more clearly observable and transparent due to the openness of the politico-institutional context (Barca, McCann, & Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2012;Wæraas, Bjørnå, & Moldenæs, Citation2015).

In this regard, by using examples from the Swedish context, the present paper offers an empirically grounded conceptualization of the relationship between spatial planning and place branding. It does so by departing from the idea that both spatial planning and place branding are strategic actions (see Oliveira, Citation2015), and that both spatial planning and place branding are discursive practices. By taking two cases (i.e. Greater Stockholm and Swedish Lapland) as analytical examples, the present paper aims to illustrate the dialogical relationship between spatial planning and place branding. The dual-case methodology is used to explore two strategic regional development processes in different Swedish contexts as a first step towards generalization. While the first case is linked to the emergence of the brand ‘Stockholm the Capital of Scandinavia’ and the other is linked to the emergence of the brand ‘Swedish Lapland’, the two cases represent contrasting examples of relationships between spatial planning and place branding discourses that emerge through two distinct yet similar processes of regionalization. Despite both regional development processes being crowned with a place brand, there is variation in the way these emerge.

Place branding and spatial planning discourses in the context of regionalization in Sweden

The process of regionalization in Sweden is directly related to the regional policy of the EU, which has strongly affected the ways in which regional divisions are constructed with reference to the regional policy frameworks, but also to branding activities that aim to create common regional identities. This is especially the case in Nordic cross-border regions, as they are often focused around developing tourism, but are not permanent nor institutionalized regional constructs (Heldt Cassel, Citation2003; Prokkola, Citation2011). The creation of ‘new’ temporary regions as a consequence of EU regional policy and the division according to the Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS), combined with an overlapping and complex regional division of Swedish national administration (Westholm, Amcoff, Falkerby, Gossas, & Stenlås, Citation2008), has caused confusion, but also overlaps between the tasks of the different planning bodies at different geographical levels in Sweden (SOU, Citation2007:Citation10).

Despite this complexity, both in northern and southern parts of the Nordic region, there have been various forms of interregional cooperation in recent decades. The main reasons for this are the weakening of national policies, difficulties related to structural changes in the economies of the peripheral northern areas, and the need for collaboration between small municipalities. For example, the interregional cooperation of the so-called North Calotte has focused on the development of tourism in Swedish and Finnish Lapland, and tourism and leisure have been the leading industries defining the border landscape as well as the regional policy agenda (Prokkola, Citation2011). Since tourism has been the driver of many regional development projects in Sweden and the Nordic countries, the regional strategic policy has also become increasingly intertwined, with place branding and spatial planning activities to promote attractiveness and to promote the area to visitors.

This overall neo-liberal shift is visible in most European countries, including Sweden, and has been discussed as a major trend in planning and urban development (Peck, Theodore, & Brenner, Citation2009). According to Koglin and Pettersson (Citation2017), the shift, which includes a more market-oriented planning approach, has to be understood in the context of the economic situation in the municipalities in Sweden (see also Persson, Citation2013). Given the increasing interrelation of public policy and place branding (Lucarelli, Citation2017), one can observe an increasing reliance of hiring and using external branding and communication consultancy firms in municipal and regional planning (Brorström, Citation2015, Citation2017) in a way that make spatial planning and place branding more similar and overlapping.

In Sweden as elsewhere, there is a common understanding that place branding could be seen as a form of brand management discourse applied to the public sphere (Kornberger, Citation2010). This widespread narrative has led to the rapid growth of different strategies, practices, and public and private investments in regions. As forms of identity-driven policies (Boisen, Terlouw, Groote, & Couwenberg, Citation2017), place-branding practices and theories generally recognize ‘place brands’ as particular phenomena. Furthermore, despite similarities to traditional corporate branding, place brands are indeed very peculiar (Govers, Citation2013) owing to the multiple spatial layers of places (Warnaby, Citation2018) and the complex- dynamic nature of branding (see Giovanardi, Lucarelli, & Pasquinelli, Citation2013).

Central to the discourse on place branding is the element of regions adopting and presenting themselves according to various strategies such as houses of brands, alliances, or brand umbrellas. One cannot disregard the fact that the emergence of branding practices applied to public places has pushed regions to adopt a sort of brand orientation (Gromark & Melin, Citation2013), which has important strategic and political implications for regional development (Hospers, Citation2004).

In other words, while being attentive to building strong brands for socio-economic development, recent place branding practices, given their public-political dimension (see Eshuis & Edwards, Citation2012; Ooi, Citation2004), are mainly orientated towards reputation building and management. Thus, in Sweden and elsewhere, this process is political because it is a process of shaping and making new places (Lucarelli, Citation2017), but also spatial because its different geographical layers are contested by both public and private stakeholders (Syssner, Citation2010). Hence, the process emerges as spatio-political discursive (Lucarelli & Giovanardi, Citation2016). Thus, place branding is thereby an integrated part of general urban and regional strategies and a cornerstone of territorial governance (Boisen, Citation2015; Eshuis & Klijn, Citation2012; Oliveira, Citation2016).

In equal terms, the context of spatial planning in Sweden may be described as being shaped by both centralized and decentralized policy; the municipalities have a strong role in providing welfare services and there is a regulated formal monopoly that is in the hands of municipalities, which heralds the main decision on spatial planning and place branding practices and policies. However, as found in studies on recent changes in urban and regional planning practices (Koglin & Pettersson, Citation2017), the strong role of the municipalities has been reduced as a consequence of new collaborative forms of policy making and public−private partnerships, together with a focus on pro-growth policies.

However, the pro-growth perspective in planning, discussed by Inch (Citation2015), is also affecting the ways in which participation in planning is discursively articulated and executed in practice. Growth orientation in spatial planning has suggested a stronger focus on improving efficiency in decision-making, which is also related to the strengthening of relations between local authorities and the private development sector in order to facilitate development initiatives and to implement decisions.

A dialogical approach to the relationship between spatial planning and place branding

The democratic, participatory aspects of strategic policy and planning initiatives may be understood as being interrelated and intertwined with place branding and regional development in ways that make them difficult to analyse in isolation from one another. However, this is not entirely new or specific to Sweden. Recent studies have attempted to bridge the two research fields, namely that of place branding and the field of spatial planning. These studies have been useful for the framing of such relationship as a form of strategic policy. As shown in the cases of Portugal (Oliveira, Citation2015, Citation2016), Italy, and the United States (Van Assche & Lo, Citation2011), studies have analyzed the dual strategic nature of place branding and planning (Albrechts, Citation2004, Citation2013; Oliveira, Citation2015) by recognizing that both spatial planning (Van Assche & Djanibekov, Citation2012) and place branding are forms of strategic policy that are imbued with spatial and discursive features.

However, in the Swedish context, there is often no clear distinction between the top-down, policy-driven planning perspective and the bottom-up, local or participatory perspective. Instead, complex visualizations and narratives that represent the identity of the branded region are created by various actors, namely tourists, businesses, public organizations and the local population. Previous studies in other contexts have overlooked the explicit ‘dialogical’ nature of spatial planning and place branding in praxis by instead offering diverse, yet primarily dialectical views of such relationship. As Oliveira (Citation2015) pointed out, integrating place branding into strategic spatial planning initiatives could support a structural change, such as image reorientation, repositioning, and moving forward to a higher level of social and economic development. By departing from the idea of place branding as a strategic spatial instrument, the relationship between place branding and strategic spatial planning can be refined according to focal points for the adoption of an approach that integrates place branding and spatial planning on a regional level (Oliveira, Citation2016). Nonetheless, as shown by Boisen et al. (Citation2017), the above-mentioned process could also happen the other way around, with place branding having a strong influence on both material and immaterial aspects of urban and spatial governance.

For this reason, the Swedish context of the discourse of regional development is a suitable ‘field study’ to perform an analysis of the dialogical relationship of spatial planning and place branding in which both discourses are emerging as form of strategic policy for places imbued with spatial features (see Giovanardi, Citation2015). Thus, in the integration and analysis of place branding and spatial planning discursive practices, not only should both poles be given full consideration (Boisen et al., Citation2017), but the fact that both could also be seen as emerging trajectories upon which their relationship differently emerges and materializes.

Compared to the purely dialectical view in previous studies, a dialogical approach towards the relationship and analysis of spatial planning and place branding research implies a relational view to knowledge (Crossley, Citation2015), which assumes a focus on interactions, nodes and relations. This also means that whereas dualism could be still remaining an important analytical object of analysis in analyzing the discourses of place branding vis-à-vis spatial planning, what is at stake in a dialogical analysis is not the dualism per se, but the relationship between the discursive practices across time and space. This view suggests that relationships between place branding and spatial planning is a ‘living conversation’, in dialogue where everything that is said is in relationship to the others.

Based on this specification, in order to offer a framework that allows an analysis of their dialogical relationship, the present paper considers spatial planning and place branding as (meso) discourses, which are both constituting and constituent of regional strategic development policy as form of (macro) discourse. This means that the specific spatial planning and place branding analyzed here are discursive practices that constitute the becoming of regional development policy. In this regard, rather than endorsing an ostensive approach to the relationship between place branding and spatial planning like the one framed by Oliveira (Citation2015), the present study considers the way in which place branding and spatial planning discourses are based on co-occurrences of driving and driven mechanisms in the evolution of strategic regional processes. This approach is in line with a discursive perspective to place branding (Lucarelli & Giovanardi, Citation2016) and spatial planning (Vanolo, Citation2014) that attempts to unpack the political dimensions and consequences of branding and planning places. It is also in line with an ecological model of politics (Lucarelli, Citation2017) and evolutionary model of governance (Van Assche, Beunen, & Duineveld, Citation2013), which implies an emic and emerging relationship between different dimensions and materializations of place branding and spatial planning.

Methodology and methods

The following analysis is based on a dual case study (Cova & White, Citation2010) of two strategic regional development processes in Sweden. A dual case study allows for an effective exploration of two cases in similar contexts in order to offer not only an empirically led analysis of specific phenomena, but also a contextual analysis as a first step towards generalization. In fact, whereas the first case is linked to the emergence of the brand ‘Stockholm the Capital of Scandinavia’ and the second is linked to the emergence of the brand ‘Swedish Lapland’, the two cases represent contrasting examples of relationships among spatial planning and place branding, which materializes through two different, yet somehow similar processes of strategic and discursive regionalization. In actuality, despite both regional development processes being crowned with a place brand, there is variation in how these emerge.

The choice of the cases (that is, Sweden and Swedish regional development processes) is relevant for contextual-based theory building, since departing from a rather already familiar field effects researchers’ senses and emotions, stimulates discovery, and invites description and comparison. Ultimately, it allows for the context to be the generator of theoretical insights. Also, more crucially, as suggested by Gromark and Melin (Citation2013), not only do ‘Swedish public sectors work with brands’ but ‘Sweden is very appropriate for conducting this type of research because the nation has a very ambitious and diversified public sector’.

The data collection follows a longitudinal research design (Eisenhardt, Citation1989) and is comprised of both primary and secondary data collected during a period of 10 years in total. Specifically, the empirical study constituting the case of the regionalization of Greater Stockholm lasted about six years (2010–2016), and the one constituting the case of the regionalization of Swedish Lapland was undertaken in two periods, one between 2007 and 2009 (with a focus on spatial planning and the branding of Kiruna) and the other from 2013–2017 (focusing on the development of the brand/region Swedish Lapland). The research was carried out by two researchers (i.e. the authors of this paper) separately and co-jointly in terms of analysis and interpretation.

The authors had separately collected both qualitative and quantitative data through one-time and recurrent semi-structured interviews (20); official documents (about 40 pages); participant observations of general assemblies (7) and board meetings (5); statistical and archival documents (250 pages); and informal chats with entrepreneurs, residents, and public officers in the Greater Stockholm area, in Kiruna, and in the administrative region of Norrbotten.

Kiruna is the northernmost municipality in Sweden and belongs to the County of Norrbotten, which is the northernmost county. Since Swedish Lapland is not an official name of any administrative region, material for the analysis have been collected from municipalities and county level, but also from the specific websites related to the branding of Swedish Lapland as a region and a destination. The documents analyzed were related to the region of Swedish Lapland as for example the website of Swedish Lapland Visitor Board, strategic regional Masterplan plans of Kiruna-Lapland (e.g. Masterplan Kiruna-Swedish Lapland, Citation2015), development plans from the County of Norrbotten (e.g. Länsstyrelsen Norrbottens län, Citation2012), strategies for regional growth of the municipality of Kiruna and documents related to the branding platform of Kiruna-Lapland (e.g. Kiruna Kommun, Citation2016; Swedish Lapland, Press information, Citationn.d.). These documents were available online through the municipalities and region’s website. In regarding to Greater Stockholm, the documents analyzed instead were related to Stockholm County regional and planning documents (e.g. RUFS, Citation2010), the branding and promotional material of Stockholm as well as the neighbouring municipalities (e.g. Stockholm the Capital of Scandinavia brand book) available online, and several strategic regional plan for regional growth Mälarregion (e.g. Mälartinget Annual Reports). This last one represents an important linkage in the evolution through time of the brand ‘Stockholm the Capital of Scandinavia’ as Mälarregion is an imaginary geographical area including 56 municipalities and approximately the 40% of Swedish population, located around the lake Mälren that through the activities promoted since 1992 by Mälardalsrådet (i.e. Council of Mälarregion) also serves as platform for collaboration between politics and business to promote common strategy goals.

The authors also performed a more recent search of different websites belonging to the actors involved (that is, various authorities, companies, blogs, and communities) that used the visual and textual elements of the Greater Stockholm area and Kiruna-Lapland/Swedish Lapland. More than 80 websites belonging to different actors were scanned and included in the analysis. The analytical processes of the cases follow the guidelines of performativity research (Hansen, Citation2011; Haseman, Citation2006) in the sense that the research had been performative both in the process of going back and forth from the field to the desk for data collection, but also in the production of the narration in the cases (see Hansen, Citation2011). In other words, at a mature stage of their respective research, the authors performed a joint discussion (see Ekström, Citation2006) based on our own work, and this discussion produced several written texts upon which the present final analysis and outcome was performed.

The regionalization discourse in Greater Stockholm

In Stockholm, the discourse of place branding had already emerged in the mid-1990s due to a narrative that claimed that that the best way to strategically develop a stronger city and region would be to create regional clusters and market them through a new brand. Hence, in addition to (older) brands such as ‘Beauty on the Water’, ‘Nobel City’, ‘Venice of the North’ and ‘Gateway to the Baltic Sea Region’, a new brand for Greater Stockholm was conceptualized and then launched in 2003: ‘Stockholm, the Capital of Scandinavia’(SCS). The new branding was conceived following a corporate-like branding strategy, as can be seen by the publication of the brand book in 2005. This book textually and visually describes three position statements reflecting Stockholm: Stockholm the Central Capital of Scandinavia, Stockholm the Culture Capital of Scandinavia, and Stockholm the Business Capital of Scandinavia. The main body managing the brand is the Stockholm Business Alliance (SBA), a Stockholm-based collegial assembly formed and representing a partnership between the City of Stockholm, Stockholm County and 51 other municipalities in the Greater Stockholm area.

The driven process of branding

The Stockholm Business Alliance executive body consists of the Stockholm Business Region SBR, a company wholly owned by the City of Stockholm that also owns the Stockholm Visitors’ Board (SVB). Whereas the SVB aims to promote Stockholm as a destination, the SBR targets the business sector and functions as an investment promotion office that offers information about the region, pinpoints prospects, responds to inquiries, and follows up on investments.

Whereas the SVB and SBR in their daily activities act more as executive bodies, the SBA functions both as an assembly and an umbrella organization to which membership is allowed by payment of a fee. What is peculiar for the Stockholm case, as already pointed out by Metzger (Citation2013), is that the brand ‘Stockholm the Capital of Scandinavia’ has emerged as a branding process in direct relationship with the creation and branding of another loosely organized assembly, namely the Mälarregion. This assembly includes a similar constellation of stakeholders (mainly public sectors organization as municipalities, local transportation companies), all of which are located in the territory around Lake Mälaren. In the 1990s, 10 years before the launch of the SCS brand, the same stakeholders that were also involved in SCS development were the main driving actors in creating a regional vision. This process of ‘brandification’ of the region, which was identified with the brand itself in the brand book written in 2005, could already be traced back in several Mälardalen official documents.

In this regard, if the Mälarregion was, at its inception, a regional assemblage conceived of by following regionalization as EU policy, it has, over the years through a series of informal and formal meetings, been institutionalized as the strategic body holder of the regionalization discourse in all of Central Sweden. However, whereas in 1990s spatial planning was ‘inviting’ place branding into the conversation, in the 2000s the relationship was inverted, with SCS representing both the internal and external ‘branded’ extension of the new political and spatial development and organization of Greater Stockholm. It follows that the pairing of branding processes during the 1990s with the narrative of planning a ‘functional region’ was a trajectory development that, years and meetings later, pushed the Mälararegion to be not only considered a loosely organized territory but also a de facto spatial layer of a ‘branded’ region. By the 2000s, some of the actors involved in the modular system of assemblage (such as the City of Stockholm) assumed the role of being the main drivers in the process of transformation from functional region to a ‘branded’ region.

This transformation materialized not only in terms of a different (brand) orientation, but also symbolically; for example, through the progressive disappearance of the label ‘Mälarregionen’ in the original sense of its more geographical meaning. It was transformed first as ‘Stockholm-Mälardalen’ (see Mälartinget Annual Report, Citation2000), and then ‘Stockholm the Capital of Scandinavia’ (see Mälaren Annual Report, Citation2005). Central in this phase was the inward-branding orientation processes within the City of Stockholm that were translated into a number of entrepreneurial activities that positioned Stockholm as a key-actor in the region. Whereas the City of Stockholm was very active in starting projects and various collaborations at the beginning of the 2000s, the action of the politico-business development cohort inside the Mälartinget had been an important driving mechanism in the full adoption of branding as the primary philosophy. It is precisely in that historical moment that stakeholders who had thus far been only marginal observers of the Mälartinget assembly – such as private entrepreneurs and companies like the Airport of Stockholm Arlanda, the Scandinavian airline company SAS, as well as other local entrepreneurs in the tourism industry such as hotels groups, chains, and restaurant associations – started to gather and pursue the vision of internationalizing Stockholm in branding terms.

Contested border of Stockholm – strategic policy or belonging?

The creation of the brand book in 2005 and the growth of the SBA can be seen as a material transformation of the regional area that through implementation of ‘branding orientation’ were spelled out in clear terms in the brand book. This is important to note, especially since the geographical claim of the brand did not match the original territorial definition as framed by the Mälarregionen or other territorial definitions of Stockholm as a city (see Metzger, Citation2013). The enrolment of municipalities up to 250 km away from Stockholm as members may be interpreted as an impressive overcoming of physical and ideological borders, creating a totally new branded space.

Today, the SBR is internationally recognized as the voice of the SCS brand. Through SCS, ‘Stockholm’ is representing a space that stretches far beyond individual municipal borders. By participating as paying members, the 51 municipalities’ physical and legal spatial connections to Stockholm are changing drastically. In fact, by claiming that Stockholm is the ‘only true’ region that can be the capital of Scandinavia (The Stockholm brand book, Citation2005, p. 6), the municipalities that decide to be members of the alliance – thus embodying the brand SCS – are not only forced to re-negotiate their own individual geographical (brand) identity, but are also paving the way for ‘Stockholm the Capital of Scandinavia’ to orient itself towards the construction of a new regional-political landscape.

The digital presence of SCS has not only mobilized municipalities, but also a number of public and private companies located in the Greater Stockholm area. Hence, SCS is now oriented not only locally inwards, but also globally outwards, and it is portrayed and used in different arenas, in different media channels. Examples include the show that was performed by two Stockholm–based artists on behalf of the City of Stockholm at the international property event MIPIM in Cannes 2012; the naming of SCS in several international newspapers such as the Norwegian Aftonposten or the American New York Times, as well as debates in several social media platforms such as official and un-official Facebook pages, YouTube clips and webpages, and on-going debates based on Twitter.

The increased number of webpages on which SCS is mentioned, discussed, called upon, opposed, and criticized indicates that the orientation of the brand is strong enough to attract additional stakeholders. Since 2005, there has been steady growth in the number of websites that belong to individuals and collective communities, as well as private companies and public organizations that purposefully and explicitly adopt the brand and interpret or reproduce the message of SCS in various ways. Some examples of this are the Dutch Chamber of Commerce, London City Airport and the interesting case of the Skellefteå Convention Centre, located 800 km north of Stockholm, which is also part of Swedish Lapland.

The regionalization discourse in Swedish Lapland

Swedish Lapland (SL) is a newly coined name of a region located in the north of Sweden, although ‘Lapland’ is also the name of a province in the northernmost parts of Sweden and a regional division of northernmost Finland. However, these existing regions do not coincide with this newly emerged region in branding and regional policy known as Swedish Lapland. The municipalities and counties in the northern parts of Sweden decided around 2005 to start cooperating within a loosely assembled broader region that was later called the Swedish Lapland Visitor Board, founded in 2007. Swedish Lapland is a collaboration among 16 municipalities in the northern part of Sweden with the purpose of branding the region to visitors, with a focus on international tourists (see Swedish lapland Visitors Board, Citation2017).

By constructing this new region, geographical borders have been proposed along with the symbolic content of the regional identity within the framework of the brand. The main purpose of the strategic alliance and the regional branding is to articulate and acknowledge the regional strengths and potential for development in a national Swedish context, but also in an international tourism context, where the North of Sweden is competing for attention and resources with other similar regions in northern Nordic countries. This process of branding was driven as a re-orientation of strategic regional policy decided on by the municipalities, towards regional initiatives focused on tourism and destination development as a consequence of the shift towards a more market-oriented and multi-level collaborative type of governance in municipal planning (Koglin & Pettersson, Citation2017). As in the northern Nordic region in general, tourism development has been promoted as the main economic activity that supports cross-border collaboration and collaboration between municipalities (Prokkola, Citation2011). The process of branding was accordingly initiated as part of a collaborative strategy between municipalities and merged with regional growth initiatives and strategies of business development in the broader region of northern Sweden. This was also in line with ambitions to try to attract more EU-funds through territorial arrangements that would facilitate development projects in the area.

The driving process of planning

The process leading to the establishment of the regional brand SL has been driven by several other initiatives that have merged over time as the different stakeholders within business alliances and municipalities decided to join forces to market and brand the whole region of the North of Sweden as a tourism destination. The main driving force was to develop better conditions for businesses and create attractiveness for inhabitants in the municipalities, where there was a political ambition to join the cooperation of strategic reasons that were motivated by regional policy and regional growth strategies (see Swedish Lapland Visitors Board, Citation2017).

One of the sub-processes of strategic policy and planning that led to this branding strategy was the development of the municipality of Kiruna since the beginning of the 2000s. Kiruna is a town that is strongly connected to and defined by mining, and the mine is a major employer at the core of local identity. However, an emerging international tourism industry have demanded a broader strategy from the municipality, which slowly started to acknowledge tourism as an important emerging sector that could potentially strengthen the economy and offer employment opportunities, mainly from the 2000s onwards (Municipal officials, Kiruna, personal communication, March 2008). Over the last decade, the emerging tourism industry, which has attracted new international markets, has become strategically oriented towards the branding of places and products through the connection to the snow, ice, vast natural landscapes, Northern Lights, midnight sun, and related conceptualizations of ‘the Arctic’ (Website of Kiruna Municipality Citation2008; Visit Kiruna, Citation2017; see also Keskitalo & Schilar, Citation2016). This emerging parallel identity of the town of Kiruna as an international destination was articulated through the overall regional policy and strategic plan to connect Kiruna to the regional level and create the brand ‘Kiruna-Lapland’. This brand was given the role of a driver, and in terms of content it expressed the core articulations of narratives and representations of the re-invention of the broader region of Swedish Lapland as an Arctic destination. However, most municipalities within the region are facing structural problems and do not have a large tourism industry, as is the case in most Arctic and northern areas in the Nordic countries (Viken & Müller, Citation2017).

Lapland is the official name of the Finnish northernmost region, so the use of the term Lapland is not possible without implying a relationship to the Finnish region with the same name. The area has been geographically extended and broadened to include all the municipalities that have a political will to be part of the branding alliance. The municipalities have been adding the name Swedish Lapland after the municipality name on their websites and in communication, such as Skellefteå (Swedish Lapland) or Luleå (Swedish Lapland).

It follows that the current narrative is the one of region presented as a destination with the clear purpose of attracting international visitors and increasing international tourism and business in the region. As evinced by the official website, one can learn that Swedish Lapland is a destination that does not necessarily relate to the official borders and regional constructs known by its citizens, but the region is primarily targeting tourists.

Thus, the cooperation and strategic alliances are stressed and motivated by the potential for maximizing growth and regional development. The argument that motivates the existence of collaboration and branding platform is formulated in relation to an implicit and underlying critique that the public resources are not used in the optimal way to maximize economic growth without collaboration with the platform of Swedish Lapland. The formulations that explain the reason behind the cooperation and the way the brand has emerged are presented in an argumentative and persuasive manner.

However, as the collaboration platform and the SL brand are driven mainly by tourism and organized as a visitors’ board, tourism is not the only industry around which activities are organized. The target of collaboration and branding aims at a broader area of regional growth policy and branding of the area as an attractive place for investors and citizens. The inward branding process is then not just related to businesses and tourism sales, but closely connected to other geographical areas that are commonly used in the branding of northern places in Nordic countries, such as ‘the Arctic’ and to the land of the Sami people, ‘the Sapmi’. By connecting the SL brand to these other geographical and highly symbolic place constructs and markers of local identity, the band is infused with value.

Contested borders of Swedish Lapland – strategic policy or belonging?

The symbolism and meaning of the Arctic are complex and diverse, but it is used in marketing contexts as a marker of something exotic, of wilderness, of the harsh and cold, and of the extreme and pristine. It is closely related to features of nature, cold climate, and practices of exploration and colonization, such as science expeditions and mining (Heldt Cassel & Pashkevich, Citation2018).

In this context, one can observe differences in the way that the region is presented and narrated on different platforms in different languages (namely Swedish and English), which further highlights the spatial features of regionalization as not only exogenous policy, but also as the geo-political dimension of branding and planning. Whereas the English version of the destination focuses on possible experiences and adventures in the area, the Swedish one is also concerned with trying to explain and justify the existence of the brand and the regional borders of the destination. It is clear that the borders and the brand name are controversial, especially in the municipalities that do not belong to the part of the region that actually belongs to the province of Lapland. The website of the municipality of Skellefteå says that ‘Skellefteå is the southern entry into Swedish Lapland’, but also that one is welcome to share ‘our Arctic lifestyle’. This shows that how the municipality of Skellefteå uses the reference to the Arctic and to nature and outdoors to communicate its relation to the SL brand. However, in the Swedish version of the text there are reasons for representing Skellefteå as a part of Lapland on the website. This need to explain the relation and inclusion in Swedish Lapland is based on the fact that the administrative region to which the Skellefteå municipality officially belongs is a different one. Therefore, the belonging to Swedish Lapland is not unproblematic and is not necessarily in line with identification among its citizens.

The branding as SL is portrayed as beneficial for all of the partners and should be used to attract more international tourists to the area. In fact, this is the way that the Swedish Lapland Visitors board communicates the main purpose of the brand: to target people and businesses outside of the area, and not as a brand for strengthening the regional identity among citizens. The narrative present above highlights the contested borders of the region and the symbolism that the SL carries, still presented in a way that seems to be attractive enough for the municipalities to engage in, regardless of critical voices. On the other hand, it also reflects the dialogical relationship between the hard and soft factors of the relationship between place branding and spatial planning (see Giovanardi, Citation2012).

Discussion

The dual case presented above highlights the specific contextually-based spatio-political features of the dialogical relationship between place branding and spatial planning with regard to regionalization. This is a way in which the discursive practices (that is, place branding and spatial planning) seen as constituting nodes of the assembling process may open the way for an analysis of the interaction of political orientation and spatial layerings, (see Haughton, Allmendinger, & Oosterlynck, Citation2013).

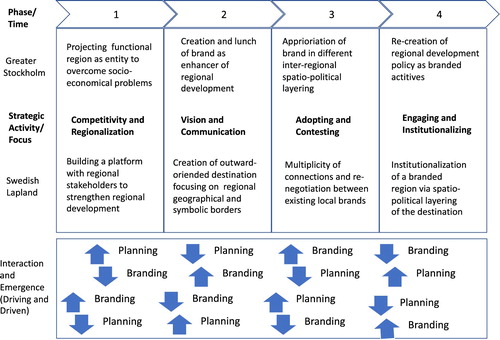

Overall, as can be summarized by below, although in both regional areas one can register a common trend in being affected by strategic policy that has led to the creation of regional brands, the way in which the process emerged has been different. Both cases represent an example of the manner in which the dialogical relationship between spatial planning and place branding is materializing, thus pointing out the multiple trajectories that this relationship can take, both in regard to the type of evolutionary governance (Van Assche & Djanibekov, Citation2012) and ecological form of politics (Lucarelli, Citation2017).

Figure 1. Representation of the dialogical relationship between spatial planning and place branding in the context of regionalization in Sweden. Authors own elaboration.

indicates how the processes of planning and branding are intersecting and working in dialogue with each other. Although the figure refers to the specific empirical cases, it also offers a way to conceptualize how discursive practices dialogically intersect in the emergence of the two brands ‘Stockholm the Capital of Scandinavia’ vis-à-vis ‘Swedish Lapland’. More specifically, the upper part of the figure (i.e. the phase/time line) represents the temporal dimension, which in relationship with the text included in the sections below gives a summative empirical account of how, inside the two regional areas (Greater Stockholm and Swedish Lapland), their brands (Stockholm the Capital of Scandinavia’ and ‘Swedish Lapland’ respectively) emerge as different intersection of branding and planning across time. Further, at a more abstract level, the figure also represents what the two cases have in common. This is a commonly followed path in the emergence of the two brands (i.e. competitiveness vision and communication, adopting and contesting, and engaging and institutionalizing), and also signifies a common framework in which regionalization is materializing as a common strategic framework in the Swedish context. These discursive practices, as presented under each phase/time and regional area (Greater Stockholm and Swedish Lapland) are represented in the lower part of the figure; these are presented in their dialogical form of driving and driven and appear as the coupling of divergent and convergent arrows which reflects different performative features (i.e. in the figure directions) of dialogical relationship. The two cases, with their emerging ‘brands’, represent the proxy of the dialogical relationship among positive and regressive soft spaces. The dual case shows that, in Greater Stockholm, the discursive materialization of regionalization as strategic regional policy emerges primarily as driving (i.e. branding-dictated) from the branding activities. In Greater Stockholm, the branding of Stockholm and the brand ‘The Capital of Scandinavia’ has acted as the focal discourse around which regionalization as strategic policy has come to be ‘real’. With this brand, the City of Stockholm seized the opportunity to accelerate the internationalization and regionalization process not only of Stockholm, but of the entire Mälarenregion. In this ‘branding’ process through the SBA, the City of Stockholm, together with various Stockholm-based companies, have become the main branding actors in attempting to shape branding policies and efforts that are not only aimed at increasing tourism turnouts, but also achieving international recognition in order to attract businesses and the creative class, and to enhance inhabitants’ sense of belonging.

In contrast to Greater Stockholm, the materialization of regionalization as strategic policy in Swedish Lapland has emerged primarily as driven (i.e. spatial planning-dictated) from spatial planning and regional growth policies. In Swedish Lapland, the spatial planning in the area and in several municipalities such as Kiruna and Skellefteå have acted as the focal discourse around which regionalization as strategic policy has come to be ‘real’. The idea of regionalization, appearing as spatial planning, has materialized as a way to strategically brand the area as Swedish Lapland with the purpose of planning for regional development, mainly through international tourism. Both the strategic policy of regional growth and specialization of tourism as an industry and the regionalization of Swedish Lapland can be analyzed as a political process driven by the municipalities, where contested borders of the region are constructed and maintained through the creation of a brand for the region. The policy-driven process and the focus on tourism as a growth engine for peripheral and economically weak municipalities, which could offer a possibility of public−private partnerships, has led to the need to construct a new regional umbrella with an attached brand that defines the geographical as well as the symbolic and socio-political dimensions of the region.

As Syssner (Citation2006) pointed out, in the Swedish context, regional development, spatial planning, regional policy implementation, and the branding of regions are becoming much more visible and intertwined practices within the overall discourse on strategic regional development. As shown by the two cases, and reinforced conceptually by , this discourse is influencing different policy fields, such as business development, tourism, and spatial planning. The relation between spatial planning and place branding may then be conceptualized as a relation where the policy and governance discourses are transformed into discourses of branding, but also that branding is seen as both the ends and the means of spatial planning practices, in a context of regional competition and pro-growth policy.

Conclusion and research implication

This paper has offered an empirically grounded conceptualization of the dialogical relationship between spatial planning and place branding. The analysis has highlighted the encounter between these discourses in their ‘outside-in’ relationship with each other (see Lucarelli, Citation2017). In this context, the present study contributes to the literature by performing a dialogical analysis on the relationship between spatial planning and place branding, which, by departing from previous research on strategic orientation (e.g. Oliveira, Citation2016), has shed light on the inherent spatio-political dimension of this relationship in the context of regional development process. The present study contextually extends Giovanardi’s (Citation2015) research on multi-scalarity in place branding, and also empirically translates Lucarelli’s (Citation2017) research on place branding as form of regional policy. It follows that the present study offers an analysis of the way in which regionalization emerges as a modular, evolutionary form of governance (Van Assche et al., Citation2013) for regions that are crowned with place brands. That means that planning for growth and business development in a region on various levels is taking place in dialogue with place branding practices and that the place brads are in themselves interconnected with, and not possible to separate from regional policy discourse. All this, as shown above, is performing a series of multiple variable relations where regionalization emerge as multi-level governance pattern of variable relations that are assembled relative to each ease; and where the changing of the relation between branding and planning is likely to be influenced by the relation between the two on another level (i.e. regionalization). At each scale and level, planning and branding is dialogical in a way that they variables, maintaining unity of narrative and action, while at the same time performing differences in the mechanism of appearance, as an overarching adaptive ‘rhizomatic’ governance.

In the case of Swedish Lapland as well as in the case of Greater Stockholm, the multiple and multileveled formal governance of the municipalities has been replaced by public−private partnerships that work towards modular umbrella structures. These include defining new regions through regionalization processes while at the same time creating and maintaining territorial brands based upon values and target markets outside of the region, such as international tourists and investors. These processes are visible also in other regions in Sweden and the Nordic countries, such as the Öresund region (Copenhagen-Malmö), Västra Götaland (Western Sweden), and others smaller regions with more rural features, such as Skärgården (the Cross-border Archipelago-region). However, the cases presented in this study represents two types of processes that shed light on the specific features of regionalization/branding related to urban metropolitan regions on the one hand and rural peripheral regions on the other. However, they differ in terms of the structuring of their geopolitical layering. In Lapland, the regional branding and strategic regional policy aims to position the region within Sweden and within the northern Nordic area (Arctic), whereas the regionalization processes of Stockholm aim to position the city region within an international context, as a metropolitan area of Europe.

Finally, a further contribution that this study brings to the fore by offering a dialogical view is that not only place branding and spatial planning as discourses may be conceived as emerging and dialogic language communities; also, any organizations, actors, and institutions, as well as planning documents, logos, slogans, and marketing plans should be understood in equal terms. Only in this way is it possible to understand and further analyze the meaning of public bids, planning sketches, maps, or embodied practices such as consulting, as dialogically contested, negotiated and created inter-subjectively by people in their relationally responsive dialogical activities. In this way, as presented in the present study, place branding and spatial planning, analyzed as regional development discourses, should not be understood as having specific features constituting specific ‘objects’ (that is, regionalization), but more as shared ways of talking, shared meanings, and metaphors (for example, through the use of branding vocabulary, regional vision and mission taglines). For this reason, further analysis adopting such a view would go beyond the limitations of the present paper and analyze place branding and spatial planning in dialogical relationship against a more diverse assemble of policies and practices that also deals with other land use activities or other actual forms of coordinating policies and practices affecting space.

On a more practical implication note, one can consider how the present study and the dual-case analysis helps suggest to practitioners, consultants, planners, clerks, and politicians that managing, driving, and taking part in regionalization, especially in today’s context where place branding and spatial planning co-exist, is a relational and dialogic process. This means that each action is always a self-in-relation with others; no act is performed in isolation. This means in other words that through branding and planning cities and regions can increasingly seek to establish even more flexible governance arrangements based on stakeholders’ interests and perspectives rather than following a spatial logic of administrative boundaries, but also, that branding and planning can create newer forms of multi-layered spatial and political agglomerations in unwanted directions which can escape the control of different public and private stakeholders’ interests.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Albrechts, L. (2004). Strategic (spatial) planning re-examined. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 31(5), 743–758. doi: 10.1068/b3065

- Albrechts, L. (2013). Reframing strategic spatial planning by using a coproduction perspective. Planning Theory, 12(1), 46–63. doi: 10.1177/1473095212452722

- Barca, F., McCann, P., & Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2012). The case for regional development intervention: Place-based versus place-neutral approaches. Journal of Regional Science, 52(1), 134–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9787.2011.00756.x

- Berg, P. O., Linde-Larsen, A., & Löfgren, O. (Eds.). (2002). Öresundsbron på uppmärksamhetens marknad: regionbyggare i evenemangsbranschen. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Boisen, M. (2015). Place branding and nonstandard regionalization in Europe. In S. Zenker & B. Jacobsen (Ed.), Inter-regional place branding (pp. 13–23). Cham: Springer.

- Boisen, M., Terlouw, K., Groote, P., & Couwenberg, O. (2017). Reframing place promotion, place marketing, and place branding-moving beyond conceptual confusion. Cities, 80, 4–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2017.08.021

- Brorström, S. (2015). Styra städer: om strategier, hållbarhet och politik. Stockholm: Studentlitteratur.

- Brorström, S. (2017). The paradoxes of city strategy practice: Why some issues become strategically important and others do not. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 33(4), 213–221. doi: 10.1016/j.scaman.2017.06.004

- Camagni, R., & Capello, R. (2013). Toward smart innovation policies. Growth and Change, 44, 355–389. doi: 10.1111/grow.12012

- Cova, B., & White, T. (2010). Counter-brand and alter-brand communities: The impact of Web 2.0 on tribal marketing approaches. Journal of Marketing Management, 26(3–4), 256–270. doi: 10.1080/02672570903566276

- Crossley, N. (2015). Relational sociology and culture: A preliminary framework. International Review of Sociology, 25(1), 65–85. doi: 10.1080/03906701.2014.997965

- Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532–550. doi: 10.5465/amr.1989.4308385

- Ek, R. (2005). Regional Experiencescapes as Geo-economic Ammunition. In T. O’Dell, & P. Billing (red.), Experiencescapes. Tourism, culture and economy (pp. 69–89). Copenhagen: Copenhagen Business School Press.

- Ekström, K. M. (2006). The emergence of multi-sited ethnography in anthropology and marketing. Handbook of Qualitative Research Methods in Marketing, 497. doi: 10.4337/9781847204127.00049

- Eshuis, J., & Edwards, A. (2012). Branding the city: The democratic legitimacy of a new mode of governance. Urban Studies, 50(5), 1066–1082. doi: 10.1177/0042098012459581

- Eshuis, J., & Klijn, E.-H. (2012). Branding in governance and public management. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Giovanardi, M. (2012). Haft and sord factors in place branding: Between functionalism and representationalism. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 8(1), 30–45. doi: 10.1057/pb.2012.1

- Giovanardi, M. (2015). A multi-scalar approach to place branding: The 150th anniversary of Italian unification in Turin. European Planning Studies, 23(3), 597–615. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2013.879851

- Giovanardi, M., Lucarelli, A., & Pasquinelli, C. (2013). Towards brand ecology: An analytical semiotic framework for interpreting the emergence of place brands. Marketing Theory, 13(3), 365–383. doi: 10.1177/1470593113489704

- Govers, R. (2013). Why place branding is not about logos and slogans. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 9(2), 71–75. doi: 10.1057/pb.2013.11

- Gromark, J., & Melin, F. (2013). From market orientation to brand orientation in the public sector. Journal of Marketing Management, 29(9–10), 1099–1123. doi: 10.1080/0267257X.2013.812134

- Hall, M. (2005). Tourism. Rethinking the social science of mobility. Harlow: Pearson Education Ltd.

- Hansen, A. (2011). Relating performative and ostensive management accounting research: Reflections on case study methodology. Qualitative Research in Accounting & Management, 8(2), 108–138. doi: 10.1108/11766091111137546

- Harvey, D. (1989). The condition of postmodernity. London: Blackwell.

- Haseman, B. (2006). A manifesto for performative research. Media International Australia Incorporating Culture and Policy, 118(1), 98–106. doi: 10.1177/1329878X0611800113

- Haughton, G., Allmendinger, P., & Oosterlynck, S. (2013). Spaces of neoliberal experimentation: Soft spaces, postpolitics, and neoliberal governmentality. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 45(1), 217–234. doi: 10.1068/a45121

- Heldt Cassel, S. (2003). Att tillaga en region. Den regionala maten i representationer och praktik: exemplet Skärgårdssmak. Geografiska regionstudier nr 56. Uppsala: Kulturgeografiska institutionen, Uppsala universitet.

- Heldt Cassel, S., & Pashkevich, A. (2018). Tourism development in the Russian Arctic: Reproducing or challenging hegemomic masculinities of the frontier? Tourism Culture & Communication, 18(1), 67–80. doi: 10.3727/109830418X15180180585176

- Hospers, G. J. (2004). Place marketing in Europe. Intereconomics, 39, 271–279. doi: 10.1007/BF03031785

- Inch, A. (2015). Ordinary citizens and the political cultures of planning: In search of the subject of a new democratic ethos. Planning Theory, 14(4), 404–424. doi: 10.1177/1473095214536172

- Keskitalo, E. C. H., & Schilar, H. (2016). Co-constructing “northern” tourism representations among tourism companies, DMOs and tourists. An example from jukkasjärvi, Sweden. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 17(4), 406–422. doi: 10.1080/15022250.2016.1230517

- Kiruna Kommun. (2016). Branding platform Kiruna-Lapland. Kiruna: Author.

- Koglin, T., & Pettersson, F. (2017). Changes, problems, and challenges in Swedish spatial planning—An analysis of power dynamics. Sustainability, 9(10), 1836. doi: 10.3390/su9101836

- Kornberger, M. (2010). Brand society: How brands transform management and lifestyle. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Länsstyrelsen Norrbottens län. (2012). Näringslivsstrategi/Strategy for growth and business development, Norrbotten County.

- Lucarelli, A. (2017). Place branding as urban policy: The (im) political place branding. Cities, 80, 12–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2017.08.004

- Lucarelli, A., & Giovanardi, M. (2016). The political nature of brand governance: a discourse analysis approach to a regional brand building process. Journal of Public Affairs, 16(1), 16–27. doi: 10.1002/pa.1557

- Mälardalsrådet. (2000). Annual Report: Stockholm: Mälardalsrådet.

- Mälardalsrådet. (2005). Annual Report: Stockholm: Mälardalsrådet.

- Masterplan Kiruna-Swedish Lapland. (2015). Norrbotten County Council.

- Meethan, K. (2001). Tourism in a global society. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Metzger, J. (2013). Raising the regional L eviathan: A relational-materialist conceptualization of regions-in-becoming as publics-in-stabilization. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 37(4), 1368–1395. doi: 10.1111/1468-2427.12038

- Oliveira, E. (2015). Place branding as a strategic spatial planning instrument. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 11(1), 18–33. doi: 10.1057/pb.2014.12

- Oliveira, E. (2016). Place branding as a strategic spatial planning instrument: A theoretical framework to branding regions with references to northern Portugal. Journal of Place Management and Development, 9(1), 47–72. doi: 10.1108/JPMD-11-2015-0053

- Ooi, C. S. (2004). Poetics and politics of destination branding: Denmark. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 4(2), 107–128. doi: 10.1080/15022250410003898

- Peck, J., Theodore, N., & Brenner, N. (2009). Neoliberal urbanism: Models, moments, mutations. SAIS Review of International Affairs, 29(1), 49–66. doi: 10.1353/sais.0.0028

- Persson, C. (2013). Deliberation or doctrine? Land use and spatial planning for sustainable development in Sweden. Land use Policy, 34, 301–313. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2013.04.007

- Prokkola, E. K. (2011). Cross-border regionalization, the INTERREG III A initiative, and local cooperation at the Finnish-Swedish border. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 43(5), 1190–1208. doi: 10.1068/a43433

- RTK. (2010). Regional Utvecklingsplan för Stockholmsregionen – RUFS 2010. Stockholm: RTK.

- SOU 2007:10. (2007). Ansvarskommittéen slutbetänkande, Hållbar samhällsorganisation med utvecklingskraft. Statens offentliga utredningar. Stockholm.

- Stockholm Business Region. (2005). The Stockholm brand book. Stockholm: Stockholm Business Region.

- Swedish Lapland, Press information and “Press kit”. (n.d.). Retreived from www.Swedishlaplandvisitorsboard.com

- Swedish Lapland Visitors Board. (2018). Retrieved from https://www.swedishlaplandvisitorsboard.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Presskit-Swedish-Lapland_190617_SV.pdf

- Swyngedouw, E., Moulaert, F., & Rodriguez, A. (2002). Neoliberal urbanization in Europe: Large–scale urban development projects and the new urban policy. Antipode, 34(3), 542–577. doi: 10.1111/1467-8330.00254

- Syssner, J. (2006). What kind of regionalism? Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

- Syssner, J. (2010). Place branding from a multi-level perspective. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 6(1), 36–48. doi: 10.1057/pb.2010.1

- Van Assche, K., Beunen, R., & Duineveld, M. (2013). Evolutionary governance theory: An introduction. Cham: Springer Science & Business Media.

- Van Assche, K., & Djanibekov, N. (2012). Spatial planning as policy integration: The need for an evolutionary perspective. Lessons from Uzbekistan. Land Use Policy, 29(1), 179–186. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2011.06.004

- Van Assche, K., & Lo, M. C. (2011). Planning, preservation and place branding: A tale of sharing assets and narratives. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 7(2), 116–126. doi: 10.1057/pb.2011.11

- Vanolo, A. (2014). Smartmentality: The smart city as disciplinary strategy. Urban Studies, 51(5), 883–898. doi: 10.1177/0042098013494427

- Viken, A., & Müller, D. K. (Eds.). (2017). Tourism and indigeneity in the Arctic. Bristol: Channel View Publications.

- Visit Kiruna. (2008). Website of Kiruna Municipality 2008.

- Visit Kiruna. (2017). Website of Kiruna Municipality and Visit Kiruna-Lapland 2017.

- Wæraas, A., Bjørnå, H., & Moldenæs, T. (2015). Place, organization, democracy: Three strategies for municipal branding. Public Management Review, 17(9), 1282–1304. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2014.906965

- Warnaby, G. (2018). Taking a territorological perspective on place branding? Cities forthcoming. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2018.06.002

- Westholm, E., Amcoff, J., Falkerby, J., Gossas, M., & Stenlås, N. (2008). Regionen som vision: det politiska projektet Stockholm-Mälarregionen. Stockholm: SNS förlag.