ABSTRACT

Inspired by the European Landscape Convention, landscape conservation policies in European countries are increasingly becoming connected to cultural heritage policies. In some European countries such as Spain, the vision of the ELC has been enriched with that of the guidelines on the inclusion of Cultural Landscapes on the World Heritage List. The Spanish National Cultural Landscape Plan, an instrument for the implementation of the ELC promoted by the Spanish Institute of Cultural Heritage, expressly states that its definition of cultural landscape should be based on the definition of the UNESCO World Heritage Convention, but incorporating the ELC. However, this confluence is ultimately reflected in confronting guidelines. This study deepens this duality of the concept of cultural landscape, explores its conflicting spatial implications, and discusses its use in Spanish regional instruments. Through the statistical study of a sample of Spanish cultural landscapes, our study recognizes the need for guidelines for the identification of landscapes of special interest, especially if they are to be converted into cultural properties afterwards. Although the study cannot provide a method that solves the problem of the spatial dimensions of the landscape without major concessions, it has provided a classification of the dominant typology.

1. Introduction

Landscape conservation policies in European countries are increasingly becoming connected to cultural heritage policies (Mascari, Mautone, Moltedo, & Salonia, Citation2009; Scazzosi, Citation2004). Landscapes are a diverse and complex form of heritage, in which it is necessary that ‘due weight be given to the full range of values represented in the landscape, both cultural and natural’ (UNESCO, Citation1994, item 43). A systematic analysis of the spectrum of landscape initiatives in the European context has demonstrated how the protection and promotion of cultural heritage prevails as one of the main goals of a large percentage of the existing organizations, laws and regulations (see García-Martína, Bieling, Hartc, & Plieninger, Citation2016). The European Landscape Convention (ELC) – and the European Territorial Strategy – justify this phenomenon in part, because they explicitly express the alliance among landscape, cultural heritage and spatial planning (Déjeant-Pons, Citation2006; De Montis, Citation2014; Scott, Citation2011).

Each European country has implemented the ELC differently based on its system of government and its tradition in landscape planning. In Italy and Spain, the coordination and implementation of the ELC are the responsibility of the ministries specializing in the area of culture; while in countries like France, Switzerland and the Netherlands, they are the responsibility of the environmental departments (De Montis, Citation2014). Nonetheless, the impact of the ELC on various countries shows that the existence of a variety of approaches among the States also occurs among the regions and municipalities of a single country (De Montis, Citation2016; Linkola, Citation2015; Roe, Citation2013; Sandström & Hedfors, Citation2018).

In Spain, the implementation of the ELC is coordinated by the National Plan for Cultural Landscape (PNPC), an instrument promoted by the Spanish Institute of Cultural Heritage. The goal of the PNPC is to provide references for activities that are to be carried out by the regions, to promote research and to conduct joint evaluations (Consejo de Patrimonio Histórico, Citation2012). A technical commission formed by the regional and state parties that are responsible, in addition to experts and social organizations, monitors the implementation of the PNPC. However, the responsibility for the environment, cultural heritage and territorial planning has been delegated to the Spanish regions. Therefore, they enjoy legislative, methodological and economic autonomy in implementing the ELC. The protagonist-nature of the region is an objective of the ELC, which encourages delegating the management of the landscape as far as possible to its users (Council of Europe, Citation2001; Dempsey & Wilbrand, Citation2017). Consequently, in Spain, there is a wide variety of regional instruments, but they generally start from certain common principles.

When Spain ratified the ELC in 2007, it already had considerable background with the valuing of exceptional landscapes as cultural heritage sites. ‘Cultural Landscapes’ were considered cultural assets and were included in the World Heritage List during the UNESCO World Heritage Convention of 1992 (Jacques, Citation1995; Rössler, Citation2006; UNESCO, Citation1992). In Spain, the cultural landscape of the Pyrénées – Mont Perdu was included in the World Heritage List in 1999, Aranjuez in 2001 and Serra de Tramuntana in 2011. These facts determined, at least in part, the selection of the Ministry of Culture as the department responsible for coordinating the implementation of the ELC and the drafting of a National Plan for Cultural Landscape. The Spanish regions tend to delegate the drafting of the informational documentation on landscape (from a cultural point of view) to departments of cultural heritage, and their departments of spatial planning are in charge of putting these documents into practice later.

The term ‘cultural landscape’, which is the origin of the title of the National Plan, is confusing because its use is very widespread; and it is employed with different meanings depending on the context (Jones, Citation2003; Phillips, Citation1998; Wu, Citation2010). In some European countries such as Spain, the expression is frequently used to designate a type of cultural property on the lines of those on the World Heritage List. However, the expression is also commonly employed by academics to stress on how the European landscapes as a whole, including those most appreciated for their natural value, depend on traditional human activities (Plieninger, Höchtl, & Spek, Citation2006; Tieskensa et al., Citation2017). In this case, ‘cultural landscape’ also implies recognition of the heritage value of the landscapes, but without exactly identifying the cultural assets (Arnaiz-Schmitz et al., Citation2018; Plieninger & Bieling, Citation2012).

Both ideas about the relationship between landscape and heritage coexist in the Spanish National Plan for Cultural Landscape. To stress and illustrate this point, accompanying the Plan was an indicative list of Spanish landscapes. With a remarkable capacity for coordination, the Spanish Institute of Cultural Heritage worked with every autonomous region to select the different places. Finally, this work was published under the title ‘100 Cultural Landscapes in Spain’ (Cruz & Carrión, Citation2015) aiming to be an exercise of reflection on the concept. At the same time and in that same vein, a commission to map and characterize those 100 landscapes was made to the research group that authors this article. It is precisely the critical observation of that work what serves as the basis for the research presented here.

This process of mapping and characterization made evident some issues that brought us to question the selection process of the different landscapes. Most noticeable was the fact that among them appeared a great disproportion in size. The fact that in that list of a 100 landscapes some were over 250,000 ha and others under 1 ha, seemed to indicate certain differences among regions in the understanding of what a cultural landscape was. Moreover, it made us question if all of them should be considered as such.

Therefore, the research presented here could be considered a continuation of the work carried on in 2015 for the Spanish Institute of Cultural Heritage. Taking the area size of the landscape as a central component for its protection and management, we have made a statistical study on the selection of the 100 landscapes. From this, we have deduced and discussed a classification of frequent situations.

Our work assumes the possibility of complementing the decision making processes of the different regional authorities for the selection of cultural landscapes. We assume that there are no possibilities of a short term replacement of these processes by others more adjusted to the nature of cultural landscapes. Thus, the data obtained in the study are useful in identifying spatial criteria to permit the regions, according with its current practices, to identify and delineate landscapes of special cultural interest. In other words, the statistical analysis herein indicates certain issues that we think must be resolved for the future demarcation of properties.

2. Recognizing cultural landscapes: characterization vs. designation

Even in the aforementioned book ‘100 Cultural Landscapes in Spain’, an article was dedicated to the difficulties in the selection process while also hinting the conflict of criteria between regional administrations (De Miguel Rodríguez, Citation2015). Giving how open the concept of cultural landscape can be, its management has been derived to professionals of different fields; mostly from geography, archeology and heritage studies. These fields have confronting opinions about the conservation of space. As we can see in this section, we think that this confrontation is what most affects the differences found in the 100 landscapes being studied. Their wide range of surface area could be the result of a conflict between the opposing concepts of ‘characterization’ and ‘designation’ – both approached from the field of cultural heritage. A conflict that has accompanied cultural landscapes since UNESCO decided to include them in the World Heritage List.

Considering landscapes as heritage posed, more than ever, the question of how the cultural reality relates to space. This generated two divergent theoretical answers that are ultimately reflected in contradictory regulations and guidelines. The first consists of designating cultural properties by recognizing well-defined areas to which exceptional values are attached (Aplin, Citation2007). This position is defended by the World Heritage Committee (WHC) and applied to the inclusion of properties on the WHL (Rössler, Citation2006). As in the case of real estate, gardens and historic sites, those landscapes included on the WHL are precisely delimited and are valued on the basis of their authenticity, integrity and historical, social or environmental relevance (Gullino & Larcher, Citation2013; ICOMOS, Citation1994; UNESCO, Citation2007).

However, the tendency of the WHC to emphasize exceptional spaces has been accused of contradicting its own initial objectives. The main argument is that the distinction between selective and non-selective landscapes is artificial (Priore, Citation2001). Even during the 90s, David Jacques (Citation1995), whose works were of great importance for the WHC of 1992, criticized the decision by UNESCO to ‘designate a portion of land’, thereby isolating it like it were a building. As an alternative, he proposed ‘characterising the landscape’ – that is, determining the cultural attributes on the continuum of the physical medium. In his opinion, this would overcome the dual notion of the protected and unprotected, and link landscapes to territorial planning policies.

From this idea, we can derive a second theoretical approach to the spatial study of cultural realities: considering the continuity of the territory according to its historical development (Moylan, Brown, & Kelly, Citation2009; Simensen, Halvorsen, & Erikstad, Citation2018). Currently, there are official programmes employing this approach for heritage assessment and management, such as the English Historic Landscape Characterization and the Scottish Historic Land-Use Assessment (Herring, Citation2009). Contrary to designation, characterization is based on the notion that ‘particular groupings and patterns of components which recur throughout the county can be seen to have been determined by similar histories’ (Herring, Citation1998, p. 11). Therefore, mapping and describing these components indicates the nature and variation of the historic character of a landscape.

Since the year 2000, the aforementioned criticism of the WHC has found recognition in the European Landscape Convention (ELC) (Council of Europe Citation2000) due to its on-segregationist position (Déjeant-Pons, Citation2006). So much so that it is possible to speak of a school of thought that sees the ELC as an instrument that ‘brings with it a modern, rich and wide-ranging approach to Landscape’ (Scazzosi Citation2004, p. 335). Against the singularization of places of excellence, the document considers culture as an ongoing reality manifesting in different forms and intensities on a geographical space, yielding an integrated understanding of European landscape heritage (Bruun et al., Citation2016).

Nonetheless, the superiority of the ELC has been questioned by those supportive of the WHC. Fowler (Citation2001) discussed the topic during the tenth anniversary of the incorporation of cultural landscapes as protected features, later underlining the need ‘to look around the world to identify landscapes arising from, associated with or representing the major cultures’ (Fowler, Citation2003a, p. 56). According to him, as important as it is to protect the landscape in general it is also important to distinguish and conserve those places that better reflect historical activities and cultures as sources of knowledge. Without contradicting the tenets of the ELC, Cultural Landscapes would become what Goodschild had already defined, ten years earlier, as ‘a very important resource, because they enable mankind to explore the history of his own development and to some extent they enable him to experience it’ (Goodschild, Citation1993, p. 48).

We see here the persistence of a conflict between the protection of landscape as a continuum and the protection of landscapes as particular expressions of culture. However, in some countries, we find that the institutions that regulate heritage management have reached a common ground in this confrontation. In Switzerland, for example, the protection of historical traffic routes begins with a global interpretation of the territorial scale through historical maps (Schneider, Citation2001). A similar case is the aforementioned programme of Historic Landscape Characterization carried out by Historic England. The programme approaches the continuum of landscape in a holistic way with the purpose of finding and protecting particular places (Clark, Darlington, & Fairclough, Citation2004). It is in this context that we can put the case of Spain and its National Plan for Cultural Landscapes.

The PNPC has needed to find a balance between the two positions of characterizing the continuum and designating the particular. While the plan originated with the ratification of the ELC, heritage policies in Spain are widely influenced by its 46 properties included on the WHL. The PNPC expressly states that its definition of cultural landscape

should be based on the definition of the UNESCO World Heritage Convention, but incorporating other contributions, specifically that of the ELC […] whose scope of action not only addresses the cultural landscapes of exceptional universal value but also landscapes as a whole. (Consejo de Patrimonio Histórico, Citation2012, p. 20)

In this sense, the theoretical body of the plan is open to the essential ideas of the ELC, in assuming that a landscape is a quality of each territory, resulting from the perception of the population. However, its methodological development contends that some portions of territory be individualized when qualifying a landscape according to its cultural interest. As such, the plan prioritizes identifying, characterizing and valuing landscapes of special cultural interest, as well as establishing objectives, guidelines and courses of action for their protection. In practice, this means accepting a designation policy, while incorporating an essential objective: portions should be valued and identified as inserts within higher territorial levels of protection.

This search for balance between characterization and designation has guided the implementation of the ELC by the Spanish regions, while observing the institutional framework of the National Plan for Cultural Landscape. Despite of the efforts made to advance in this sense, the conflict between characterization and designation persist. The respective administrative branches in charge of cultural landscape eventually follow one or the other procedure: they either characterize the territorial continuum or they identify areas of particular cultural interest. As a result, there is a disparity between cultural landscapes of different regions. A disparity that, as said, is noticeable mostly in their dimensions.

2.1. Research aims

The sample of 100 cultural landscapes indirectly shows the conflict between these different ways of understanding the spatialization of culture. Simply put, considering cultural heritage value in the continuing geographical surface leads to the inclusion of great territories; on the other hand, thinking that heritage value gathers in very particular places causes the delimitation of spaces sometimes very small in size.

This situation brings some questions: Can all of the places listed be considered as cultural landscapes? Is it possible to distinguish which places can be considered as such based on their surface area? Can this way of differentiation support the decision making processes for cultural landscapes identification? From the analysis of the 100 landscapes listed by the Spanish Institute of Cultural Heritage, our work tries to give answers to these. Thus, in a general sense, this research focuses on the problems of spatialization related to the identification of cultural landscapes. In a particular level, it tries to improve the criteria used by the Spanish administration.

First, we compare the size of the landscapes with the cultural attributes that define them. This way, we can identify patterns of relation between their size and the characteristics that justify their inclusion on the list. From this simple diagram, we infer several classifications which, eventually, each can be defined as a relation between the designated landscape and the territorial continuum.

In conclusion, taking the surface area as a central component of a cultural landscape, we intend to observe common patterns among a sample of 100 elements. Additionally, we propose the possibility of outlining spatial criteria that could improve current processes of identification. For the results to be considered by the Spanish public authorities, the study is linked with their current planning practices.

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Sample of landscapes and starting documentation

The study begins with the indicative sample of one hundred Spanish cultural landscapes. As said before, this sample was elaborated by a commission of the PNPC, in collaboration with a group of regional administrations, with the sole objective of representing great typological and geographical variety (Caro, Citation2016; Cruz & Carrión, Citation2015). We find this condition especially valid for statistical treatment. The committee began elaborating a sample of landscapes by requesting that regional technicians identify a limited number of possible cultural landscapes within their respective districts. A total of 173 candidates were selected from throughout Spain. For each landscape, the committee completed a document describing their unique features, identifying their constituent elements and defining their dominant character (agricultural, livestock and forestry; industrial; urban, historic and defensive; and symbolic). Then, the committee selected the sample, consisting of one hundred chosen on the basis of the described criteria of typological representativeness and geographical diversity. After several work sessions, the list was endorsed by the PNPC Monitoring Commission. The resulting selection shows a wide range of surface areas: from a landscape affiliated to a country villa (la Casa Massieu, Gran Canaria) to a landscape associated with a historic region (La Serena, Badajoz). The field origin of the technicians and territorial characteristics of each region have been identified as the main reasons for the wide range of locales. However, in broad terms, the 100 selected landscapes fit the definition of Cultural Landscapes provided by the PNPC.

In addition to publishing an informative book, the committee delivered all this information to our team in order to map and characterize all of the landscapes in a GIS file and in a website.Footnote1 The sample lacked the graphic and alphanumeric spatial information required to carry out our statistical study, in that it included only photographic and written descriptions for heritage valuation. While this information allows property identification, it is not sufficient for a comparative reading. Therefore, obtaining the spatial information and arranging systematically the cultural data for each landscape was part of the investigative process.

This task was carried out in two complementary phases consisting on homogenizing the information from both a spatial and a heritage perspective. On the one hand, the surface area occupied by each of the one hundred cultural landscapes was mapped using a common criterion. This part of the work provided us with the spatial variables. On the other hand, a cultural characterization of each property was carried out, which systematized the cultural variables. This information, described next in further detail is the base that we used to elaborate the statistical study.

3.2. Mapping the landscapes to obtain the spatial variables

The goal of mapping the cultural landscapes was not to generate precise cartography but to obtain spatial descriptors such as the surface area, continuity and form. The fundamental criterion for mapping consists of linking the entire landscape with the area occupied by the human activity that lends it its dominant nature; the extension of the landscapes was defined by considering the activity’s dependence on elements of the physical geography. That is to say, territorial identification is limited to the landscape’s existing characteristics and does not concern itself with discretionary factors of heritage discussion. For instance, for Palmeral de Elche, all 9300 ha of palm grove were considered, instead of separating the 507 ha included on the WHL.

This work used a scale of 1:50,000. There are European precedents in which this scale is used for cultural landscape mapping (Opach, Citation2003, Citation2004). The obtained definition is sufficient for determining spatial descriptors, while also allowing for a reduction in the precision of boundary delimitation and omitting cartographic conventions such as coding and projection. In summary, this scale can be used to obtain the dimension and shape of a surface area in which human activities of special intensity have occurred, without the need to define a precise outline.

Google Earth was used as a remote sensing tool. The platform allowed for cross-checking remote sensing results in an easy fashion through thematic maps of diverse origin.Footnote2 Map documentation sources include academic articles, conservation plans, land-use plans and documents included on the WHL. They belong to various fields and, although they served as guidance, their use has been conditioned to the general criterion of remote sensing linked to the main activity’s land uses and geographical elements. The results of this task were exported to a geographic information system.

At this point, we feel obligated to acknowledge that a cultural landscape frequently transcends municipal, regional and even national limits. In fact, within the selected places there are 6 cross-border landscapes shared with Portugal and France. The statistical study presented here, however, considers only the Spanish side for two reasons. First, because it is the side considered by the state and local authorities, at the time of making the listFootnote3; given that this is a critical study on the selection process of cultural landscapes, we cannot alter the criteria provided to us. And second, after a case by case evaluation, we have concluded that keeping the study only to the Spanish area does not affect the general results.

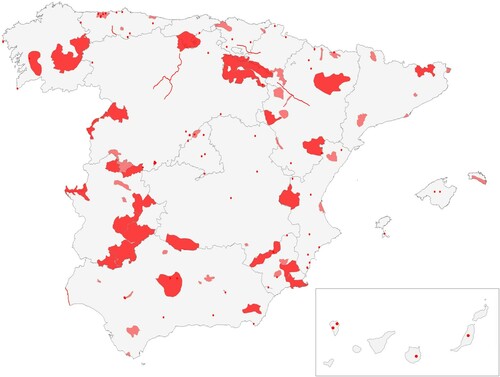

Beyond the specific information, this task provided preliminary results for the comparative study. As we can see in , the overview obtained by integrating the landscapes into one map allowed easy identification of descriptor trends. The most noticeable is the aforementioned wide range with respect to surface area.Footnote4 Such amplitude exceeds by large other examples of national maps of exceptional landscapes. For example, while the selection of Spanish landscapes ranges between 1 and 250,000 ha, the area of the 160 elements in the Swiss Federal Inventory of Landscapes and Natural Monuments ranges between 35 and 40,000 ha.

3.3. Studying landscape activities and elements to obtain the cultural variables

Various productive activities are frequently observed in the process of configuring and modelling the historic qualities of a landscape. Another commonly observed feature is the way that territory is organized with respect to complex lifestyles, resulting in a diachronic sequence. This is observed even in cultural landscapes in which one main activity is concretely dominant. On quite a few occasions, secondary activities can significantly alter the spatial structure of a landscape, preventing a proper analysis when only one classification, based on the primary activity, is employed.

This matter has been discussed since UNESCO proposed an initial classification of cultural landscapes into three categories: designed, organic and associative. These categories have been considered as rather impractical (Fowler, Citation2003a) and because of that, ICOMOS (Citation2004) elaborated several thematic frameworks for a deeper and more diverse understanding of Cultural Landscapes. Similarly, the Spanish PNPC establishes a classification based on activities that generate landscapes and acknowledges their variance depending on the physical medium. On the basis of these activities, in Spain, the Andalusian Historical Heritage Institute (IAPH) has developed a series of physical and symbolic attributes that facilitate a more complex reading of landscapes according to their heritage features (Rodrigo Cámara et al., Citation2012).

The objective of these actions is to foster landscape interpretation as a combination of multiple components. This study established a sample of attributes that is broad enough to reveal more deeply the differences between the landscapes, yet specific enough to maintain a similar descriptive level of each. These attributes may explain why some landscapes show spatial characteristics that would not initially be associated with a dominant category. Likewise, they show how multifunctional landscapes, in which several categories can be identified, are configured.

The initial information was prepared by the regional technicians and the national coordinators that developed the selection of a 100 landscapes. Afterwards, it was revised and homogenized by our team. To provide a basis for our list of attributes, we have taken the work of IAPH, as it is the most comprehensive one in terms of Spanish landscapes. In this document, attributes are organized according to the systems that allowed human beings to connect with the physical medium in order to meet needs such as livelihood, communication, settlement or symbolic ownership (Fernández Cacho et al., Citation2010). In our case, we included non-local-scale subsections, such as the Andalusian urban agglomerations.

Also, we included attributes that represent physical elements instead of open systems, as the previous existence of a system does not guarantee the current existence of material elements allowing its visibility. Therefore, we believe it appropriate to differentiate between ways of interacting with the medium and the remnants of said relationship that are currently found there. Finally, we added to this structure some of the characteristics established by Fowler (Citation2003a, Table 2), such as the presence of historic gardens and the existence of geographical elements that structure the spatial development of a landscape. In we can see the list of attributes used in the study.

Table 1. List of landscape attributes used in the study.

With this table of attributes, we can obtain a more thorough description of landscape. Each landscape is studied to determine if a specific activity was ever present, to determine the interaction with the physical medium and to determine possible tangible remains to date. The resulting association holds interest in itself, as it shows important heritage characteristics and allows a more accurate way of establishing character dominance in a particular place. That is why, as said before, this type of attribute list is frequently used in qualitative analyses of landscapes in order to better determine their nature.

As we have established in our research aims, our main objective is reaching some spatial criteria that could improve current processes of identification. That is the reason why the characterization based on tabulated attributes is linked with current Spanish practices. The PNPC classification based on activities that generate landscapes is at the core of Spanish assessment documents. These identify human activities, their physical and immaterial traces through time, and, finally, they are valued according to historic, artistic and cultural criteria. This manner of proceeding is also coherent with UNESCO recommendations if we take into account the work of Fowler (Citation2003b) on the use of World Heritage criteria for the inscription of cultural landscapes.

Now, another heritage descriptor that tends to be overlooked but is quite revealing is obtained from a quantitative reading of the tabulated descriptors: the number of landscape attributes. UNESCO has already detected a fundamental difference between landscapes based on the number of historic human activities comprising them. Thus, along with landscapes that have unique traits derived from clear functional and economic orientations, we find more complex landscapes configured by multiple layers of process. That is, landscapes that ‘have several cultural values at once [and] can be important for social, scientific, historical and aesthetic reasons, or any other combination of values, depending on the features and the layers of history and associations attached to these features’ (Mitchell, Rössler, & Tricaud, Citation2009, p. 52). As our table comprises those aspects that provide cultural values, we can say that the sum of descriptors identified for each landscape provides a measurement of cultural complexity.

4. Results and discussions

4.1. Statistical study

After standardizing the parameters for comparing landscapes, the data were formally analysed. Mapping and characterization resulted in two spatial variables (dimension and structure) and two cultural variables (cultural nature and number of landscape attributes). Both spatial structure and nature are non-quantifiable parameters; therefore, comparing them with other parameters does not offer a broad and varied vision of the space-culture relationship. Consequently, the statistical study began by cross-matching the surface and number of attributes of the mapped landscapes. Both values describe different quality aspects of the landscapes. On the one hand, the number of attributes renders the complexity of the internal structure of the landscape, in which different activities are somewhat interconnected. On the other hand, the surface describes a conditioning factor that is crucial in the debate around heritage property identification presented at the beginning.

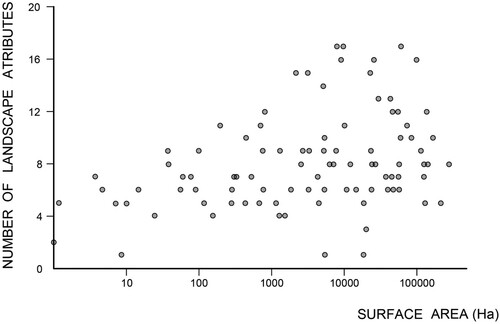

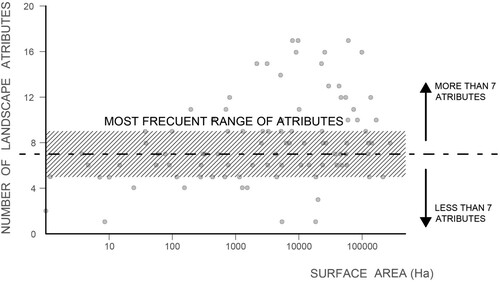

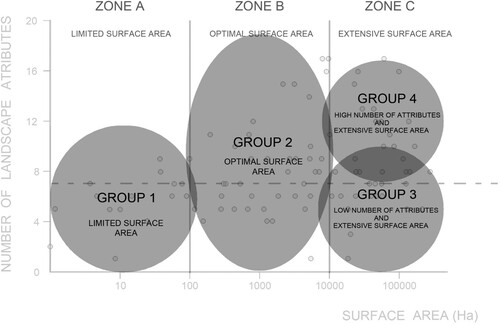

In order to cross-match both variables, a scatter plot with an axis for each variable was elaborated (). The surface of mapped landscapes numerically expresses the extension obtained through cartographic representation, in hectares. This is represented on the horizontal axis with a logarithmic scale, as required to visually represent the distribution. The number of landscape attributes is represented on the vertical axis; it is measured up to a maximum of 18, which none of the studied one hundred landscapes achieved.

The table yields several conclusions. The most obvious one is that, generally, an increase in surface area correlates with an increase in number of attributes. But also, a not so obvious one is that generally, and without relation to their size, most landscapes keep an even amount of attributes. Most frequently, they embody between five and nine of the attributes; this represents 62% of the sample. Landscapes that exhibit more than nine attributes account for 27%; these generally contain multiple productive activities and a wide presence of elements of different eras and purposes. Only 11% of the sample, comprising landscapes with only one dominant human activity, showed less than five attributes ().

While landscapes of over 100 ha represent a small percentage of those that exceed the standard range of attributes, almost half of the landscapes with more than 1000 ha have more than nine attributes. This may seem obvious, given the high chances of a specific surface area having more elements and cultural systems than one of smaller size. Therefore, the cultural configuration of larger areas is logically more complex and inclusive. But we find that this dimension- number of attributes ratio does not apply to all landscapes. A large number of smaller landscapes still show a range of 5–9 attributes.

More important is the fact that some landscapes that show less than five attributes can be rather large; for example, the Albufera in Valencia, which is dedicated to rice cultivation, reaches a surface area of almost 19,000 ha while exhibiting only one attribute.

These ratios seem to indicate an intrinsic difference between landscapes that in some cases relates to their size and in others it does not. The number of landscape attributes is a condition that depends on historical and cultural influences, but the evidence of certain surface ratio principles calls for a deeper analysis of the dimensional aspect by adding into the table extrinsic variables.

4.2. Establishing an optimal range of surface area

As opposed to the intrinsic nature of the number of landscape attributes, landscape extension is a characteristic that is widely discussed in the scientific community. The WHL already includes cultural landscapes of uneven extension. For instance, compare the Royal Hill of Ambohimanga, with an area of 59 ha, with the African landscape of Lopé-Okanda, which is eight thousand times more extensive. This range of extension produces issues by excess and by default: what is the extension limit that tells us whether we are looking at a cultural landscape and not a cultural site? Similarly, what is the maximum acceptable dimension for considering cultural landscape values related to a community? Given the sample variety, it seems difficult to establish fixed numbers for designation. However, we can discuss some conceptual limits. This discussion, which is relatively new in the field of cultural landscape protection, already has a long tradition with respect to nature reserves (Higgs & Usher, Citation1980).

According to Rössler ‘[cultural landscapes] made people aware that sites are not isolated islands, but that they have to be seen in the ecological system and with their cultural linkages in time and space beyond single monuments’ (Citation2003, p. 340). This affirmation inherently includes the definition of a minimum extension for cultural landscapes: that which allows them to be differentiated from cultural sites. In the UNESCO Handbook, Rössler added that, ‘in determining boundaries, the linkage with the larger context is important’ (Mitchell et al., Citation2009, p. 50). In summary, the minimum extension of a cultural landscape shall be that which allows, aside from certain heritage elements and spatial phenomena, for the inclusion of the integrity of a relational and active socio-ecological system. This understanding has been about since the inclusion of cultural landscapes on the WHL in 1992. At that point, collaboration with the International Union for Conservation of Nature was already needed for rendering a specifically ecological, systematic vision to the assessments of ICOMOS, which were more conservative (Phillips, Citation2003).

Regarding the maximum extension, the concepts of ‘management’ and ‘governance’ are emphasized for nature reserves: ‘while “management” addresses what is done about a given protected area or situation, “governance” addresses who makes those decisions and how’ (IUCN Citation2008, 1). UNESCO insists that this ‘governance’ must be the responsibility of a local community as much as possible, as it considers that supra-regional management bodies are detached from the landscape values (Mitchell et al., Citation2009, p. 35). Other authors even talked of the need for a ‘decentralization of Landscape ruling and legislation, which favours regional solutions’ (Vos & Meekes, Citation1999, p. 3). Thus, a maximum extension could be established based on the management capabilities of local agents. In other words, in order to allow local control, cultural landscapes should not surpass dimensions that prevent a given community from implementing ‘adequate long-term legislative, regulatory, institutional and/or traditional protection and management to ensure their safeguarding’ (UNESCO Citation2017, paragraph 97).

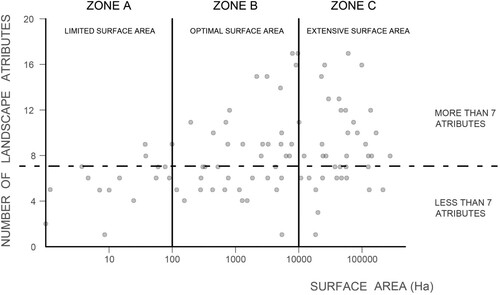

It is possible to establish an optimal surface range, without having to exclude those landscapes outside of it.Footnote5 In our case, based on the aforementioned conceptual guidelines, we have established guiding values that cover an extension from 100 to 17,000 ha; these were determined on the basis of Spanish and European precedent. European WHL landscapes, on the smaller side, tend to be around 100 ha, while the larger ones exceed an area of 100,000 ha.Footnote6 Those Spanish sites that are classified as Protected Landscapes – sites requiring special protection because of their natural, aesthetic and cultural value (Spanish Government, Citation2007, p. 29) – have a minimum extension of 100 ha and a maximum of 17,000 ha. The difference between the Spanish and international maximums lies in the geographical and historical realities of the country. Clearly, the results of the Spanish landscape group match the regional results of the IAPH in the Register of Landscapes of Cultural Interest of Andalusia (Fernández Cacho et al., Citation2015).

In this sense, we can observe in which landscapes are outside the range of the scatter plot. Within the range, in what we have called ZONE B, we found 48% of cultural landscapes with a surface area that allows a management that can be carried out by local communities. Meanwhile 15% of the properties were found on the left (ZONE A), raising doubts regarding their classification as cultural landscapes or cultural sites. On the other side (ZONE C) were 37% of the landscapes, which suggests serious difficulties for local communities in managing them. As opposed to the ‘number of landscape attributes’, an inherent characteristic, the delimitation of surface directly affects cultural landscape designation.

4.3. Classification

Including both the division based in size and number of landscape attributes we can derive the model seen in . About 43% of the sample landscapes have what we have determined to be optimal area (GROUP 2), regardless of their number of attributes. Most of them are close to average in this regard, with a lesser trend towards a large number of attributes.

Figure 5. Tendencies of the different landscapes, with respect to surface area and number of attributes.

However, groups outside of the optimal surface range, in which the number of landscape attributes is more important, should be analysed. The following cases were found:

Landscapes of limited surface area (GROUP 1–15%): Landscapes that are mostly average with respect to number of attributes, but that do not have sufficient extension. This is because they are landscapes based on one specific element, e.g. an archaeological area (such as the Son Real landscape), or on a group of elements, such as the mills of Mota del Cuervo, of high symbolic nature but limited territorial impact.

Landscapes of extensive surface area (Group 3 and 4–37%): This group is more varied and complex than the former, for which a differentiation based on the number of landscape attributes must be established:

− Landscapes of extensive surface area that tend towards a low number of landscape attributes (GROUP 3). Formed by the presence of a dominant activity throughout its extension, without including other considerable attributes or a relationship beyond the activity itself. We can say that these landscapes belong to a clear type and, consequently, can be compared to others belonging to the same type. This is the case in landscapes like the aforementioned Albufera in Valencia, whose rice fields cover a great area, yet without any additional elements, and therefore can be compared to other landscapes formed similarly by the cultivation of rice in the Mediterranean Coast.

− Landscapes of extensive surface area that tend toward containing a high number of landscape attributes (GROUP 4). The presence of multiple historic human activities has led to a high number of physical traces, with perceptive and social phenomena linked to them. This is the case in historic regions such as La Vera, whose historic evolution has been determined by different cultures and human activities over a very long period of time. Giving the highly particular nature of these landscapes, they cannot be typified clearly.

5. Discussion

In Spain, the decision making process for designation of a cultural landscape is very similar to the ones employ for other cultural properties like historic gardens or historic sites. Our work accepts that there is no real possibility of substituting these procedures with others more adequate to the nature of cultural landscapes. Therefore, the data obtained in the study are useful in identifying spatial criteria that allows Spanish regions, according with its current practices, to identify and delineate landscapes of special cultural interest. The statistical analysis herein indicates certain issues that must be resolved for the future demarcation of properties.

This way, the research presented here ads on to other Spanish initiatives in this same vein. The Spanish regions are progressively opting to develop informative instruments that treat landscapes on two scales to implement the ELC: (i) on a larger scale, the process begins with the construction of a regional map, through the cultural characterization of its landscapes; and (ii) on a smaller scale an inventory of landscapes of special cultural interest is developed (Dempsey & Wilbrand, Citation2017; Fernandez Cacho, Fernández Salinas, Hernández León, López Martín, & Quintero Morón, Citation2008; Rodrigo Cámara et al., Citation2012; Santé et al., Citation2019).

Going back to the questions posed in the introduction, the diagram in allows us to start discussing different kinds of relation between the designated landscape and the territorial continuum. We do not pretend these to be definitive, but rather to start a debate that helps bring administrative practices in line with the ELC:

Tendency towards group 1: Landscapes of limited surface area, regardless of the number of landscape attributes. First, it is worth asking whether these properties should be treated as cultural landscapes, or if alternative protection programmes may be more suitable to their spatial reality such as those of cultural sites or historic gardens. To this end, it is necessary to verify whether they include a coherent socio-ecological system. In general terms, this percentage of landscapes shows a spatial structure in which one sole element stands out because of its peculiarities, establishing an area of influence around itself. Therefore, for verification purposes, studying whether the demarcation comprises the area of influence adequately or not is necessary.

Tendency towards group 2: These landscapes can be considered as balanced given that they have an optimal surface area to be managed.

Tendency towards group 3: Landscapes with a low number of attributes and an extensive surface area. These landscapes are too large to be managed by a local community. Therefore, a reduction in surface area is necessary to carry out proper stewardship. Given that these landscapes belong to one clear type, we are of the opinion that the corresponding authorities would have to determine the portion of the landscape that best represents the characteristics of this type. Thus, the specific cultural landscape can be related to the continuum through its typological representativeness.

Tending towards group 4: Landscapes with a high number of attributes and an extensive surface area. These landscapes need to be reduced for the same reason as above. However, in this case, their high number of attributes show a complexity that prevents them from belonging to any clear type. In this case, we think that the corresponding administration would need to localize a portion of the overall area that includes a majority of characteristics that define the landscape. While the rest of the landscape can be managed broadly through laws that address the continuum, this sample area can be preserved more carefully as a representation of the particularities of the place in question. Thus, the specific cultural landscape can be related to the continuum through its intrinsic representativeness.

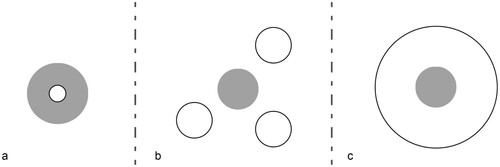

We find four tendencies of spatial domains that cover a wide variety of landscapes. The landscapes of group 2 are characterized by their uniqueness ((a)), that is, landscapes that stand out for their rarity or excellence that clearly manifests in space. Their surface area is generally optimal for management. The landscapes of groups 3 and 4 can be demarcated by spatial criteria of typological or intrinsic representativeness, respectively. These criteria are based on the World Heritage framework and, although the UNESCO literature serves as a reference (Anthamatten & Hazen, Citation2007; Castillo Ruiz & Martínez Yáñez, Citation2014; Pressouyre, Citation1996), its use is different: here we select an optimal area within a large area, and do not discuss whether a landscape should be included in the list ().

Figure 6. Derived relations between designated landscapes and territorial continuum: (a) Singular element that needs to include an area of influence; (b) Landscape designated because it best represents a clear typology and (c) Landscape designated because it represents the main characteristics of a bigger geographical entity.

Typological representativeness ((b)) can answer the following question: does this landscape have exceptional value within the landscapes of the same category, function, or associated activity? In turn, intrinsic representativeness ((c)) can answer the following question: is it a fragment of landscape that, as part of a continuum, is of exceptional value to represent the total? In short, these concepts are proposed as a means to star debate over spatial criteria for demarcation. This new set of criteria can be easily incorporated to current practices of designation. They would allow working with intrinsic characteristics to relate landscapes of special cultural interest to the physical continuum that they belong to. Furthermore, they could set some standards for management based on empirical experience.

6. Conclusions

In Spain, regions are responsible for implementing the ELC. However, there are some aspects that particularize the Spanish case as a whole: (i) the vision of the ELC has been enriched with that of the WHL; (ii) there is minimal coordination between the state and the regions through the National Plan for Cultural Landscape; (iii) the drafting of new landscape information to implement the ELC has been preferentially assigned to cultural heritage departments; (iv) most regions work with information and tools that combine the large scale (characterization) with the scale of identification of landscapes of special cultural interest (designation); and (v) the departments of culture of the regions assume the implementation of the ELC, which corresponds to the designation of landscapes of special cultural interest.

Our study recognizes the need for guidelines for the identification of landscapes of special interest, especially if they are to be converted into cultural properties afterwards. Although the study cannot provide a method that solves the problem of the spatial dimensions of the landscape without major concessions, it looks towards a possible classification of spatial relations. Landscapes valued for their uniqueness rarely present spatial problems for their demarcation. However, we do believe that some thought should be given to the fact that some properties should first be considered historical sites or gardens rather than cultural landscapes. Especially, when they have little relevance within the socio-ecological system of the territory. In the same way, we are of the opinion that it is not appropriate to identify surfaces that escape the management of the local inhabitants as cultural properties. In these cases, it is possible to resort to designating a more adjusted area or consider protective figures other than the designation as cultural landscape.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The website (www.100paisajes.es) works as an online exhibit of the work carried on by the Spanish Institute of Cultural Heritage and it was done by the research group that authors this article.

2 Taking advantage of the fact that all landscapes are acknowledged by local communities and, therefore, have been studied both by scholars and administrations.

3 Nonetheless, the PNPC aims to “driving forward cooperation with cultural landscape policies and networks on a European scale, specifically in matters to do with the study and safeguarding of cross-border landscapes, in compliance with the provisions of the European Landscape Convention” (PNPC 2011, 23).

4 Another noticeable trend refers to spatial structure. The shapes of the surface footprints can be classified in basic geometric terms as follows: dots, for activities focused on one concrete element; lines, for activities carried out along a river, valley or linear infrastructure; and planes, for extensive activities. Although interesting, this information departs from the main objective of this paper and we may consider it as a follow up.

5 At a global scale, we find that landscapes on the WHL have an approximate range of 35–1.000.000 ha, and, in Europe, of 90–150.000 ha. At a national scale, Spain has a range of 100–17.000 ha, while at a more local scale, in Andalucía, there is a range of 3.000–17.000 ha.

6 Without counting the landscape of Kujataa, in Greenland, the smallest cultural landscapes on the list are the Royal Botanic Gardens in the UK, at 132 ha; the Medici Villas and Gardens in Tuscany, at 125 ha and the Sacri Monti of Piedmont and Lombardy, at 91 ha.

References

- Anthamatten, P., & Hazen, H. (2007). Unnatural selection: An analysis of the ecological representativeness of natural world heritage sites. The Professional Geographer, 59(2), 256–268. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9272.2007.00611.x

- Aplin, G. (2007). World heritage cultural landscapes. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 13(6), 427–446. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13527250701570515

- Arnaiz-Schmitz, C., Schmitz, M., Herrero-Jáuregui, C., Gutiérrez-Angonese, J., Pineda, F., & Montes, C. (2018). Identifying socio-ecological networks in rural-urban gradients: Diagnosis of a changing cultural landscape. Science of The Total Environment, 612, 625–635. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.08.215

- Bruun, M. (2016). How and why was the European Landscape Convention conceived? In K. Jørgensen, M. Clemetsen, T. Richardson & K. H. Thorén (Eds.), Mainstreaming landscape through the European Landscape Convention (pp. 5–11). London: Routledge.

- Caro, C. (2016). The National Plan of Cultural Landscape: 100 Cultural Landscapes in Spain. In 18th Council of Europe Meeting of the workshops for the implementation of the European Landscape Convention. Proceedings, 133–137. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing Division. Attnumber.

- Castillo Ruiz, J., & Martínez Yáñez, C. (2014). The agrarian heritage: Definition, characterization and degree of representation on the UNESCO framework. Boletín de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles, 66, 457–461. doi: https://doi.org/10.21138/bage.1782

- Clark, J., Darlington, J., & Fairclough, G. (2004). Using historic landscape characterisation. London: English Heritage/Lancashire County Council.

- Consejo de Patrimonio Histórico. (2012). Plan Nacional de Paisaje Cultural [ National Plan for Cultural Landscape]. Madrid: Gobierno de España.

- Council of Europe. (2000). European Landscape Convention. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing Division.

- Council of Europe. (2001). The role of local and regional authorities towards the adoption and implementation of European Landscape Convention. First conference of the contracting and signatory states to the European Landscape Convention 7, CoE Publ., Strasbourg.

- Cruz, L., & Carrión, M. (eds.). (2015). 100 paisajes culturales en España. Madrid: Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte.

- Déjeant-Pons, M. (2006). The European Landscape Convention. Landscape Research, 31(4), 363–384. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01426390601004343

- De Montis, A. (2014). Impacts of the European Landscape Convention on national planning systems: A comparative investigation of six case studies. Landscape and Urban Planning, 124, 53–65. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2014.01.005

- De Montis, A. (2016). Measuring the performance of planning: The conformance of Italian landscape planning practices with the European Landscape Convention. European Planning Studies, 24(9), 1727–1745. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2016.1178215

- De Miguel Rodríguez, A. (2015). 100 paisajes culturales: ¿Por qué y cómo? en L. Cruz Pérez, y M. Carrión Gútiez (Eds.), 100 paisajes culturales en España (pp. 17–23). Madrid: Secretaría General Técnica del Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte.

- Dempsey, K., & Wilbrand, S. (2017). The role of the region in the European Landscape Convention. Regional Studies, 51(6), 909–919. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2016.1144923

- Fernandez Cacho, S., Fernández Salinas, V., Hernández León, E., López Martín, E., & Quintero Morón, V. (2008). Caracterización patrimonial del mapa de paisajes de Andalucía. PH Boletin del Instituto Andaluz del Patrimonio Historico, 66, 16–31. doi: https://doi.org/10.33349/2008.66.2526

- Fernández Cacho, S., Fernández Salinas, V., Hernández León, E., López Martín, E., Quintero Morón, V., & Rodrigo Cámara, J. (2010). El paisaje y la dimensión patrimonial del territorio. Valores culturales de los paisajes andaluces. In VI Congreso Internacional de Musealización de Yacimientos y Patrimonio. Arqueología, Patrimonio y Paisajes Históricos para el Siglo XXI, Toledo, 59–73.

- Fernández Cacho, S., Fernández Salinas, V., Rodrigo Cámara, J., Díaz Iglesias, J., Durán Salado, M., Santana Falcón, I., … López Martín, E. (2015). Balance y perspectivas del Registro de Paisajes de Interés Cultural de Andalucía. Revista ph, 88, 166–189. doi: https://doi.org/10.33349/2015.0.3667

- Fowler, P. (2003a). World heritage cultural landscapes 1992–2002. A review. Paris: UNESCO World Heritage Centre.

- Fowler, P. (2003b). World heritage cultural landscapes, 1992–2002: A review and prospect. In P. Ceccarelli & M. Rössler (Eds.), World heritage papers 7. Cultural landscapes: The challenges of conservation (pp. 16–32). Paris: UNESCO.

- Fowler, P. (2001). Cultural landscape: Great concept, pity about the phrase. In R. Kelly (Ed.), The cultural landscape. Planning for a sustainable partnership between people and place (pp. 64–82). London: ICOMOS UK.

- García-Martína, M., Bieling, C., Hartc, A., & Plieninger, T. (2016). Integrated landscape initiatives in Europe: Multi-sector collaboration in multi-functional landscapes. Land Use Policy, 58, 43–53. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.07.001

- Goodschild, P. (1993). The general significance of historic landscapes. ICOMOS – Hefte des Deutschen Nationalkomitees, 11, 48–50. doi: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.11588/ih.1993.0.22590

- Gullino, P., & Larcher, F. (2013). Integrity in UNESCO world heritage sites. A comparative study for rural landscapes. Journal of Cultural Heritage, 14(5), 389–395. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2012.10.005

- Herring, P. (1998). Cornwall’s historic landscape: Presenting a method of historic landscape character assessment. Truro: Cornwall County Council.

- Herring, P. (2009). Framing perceptions of the historic landscape: Historic landscape characterisation (HLC) and historic land-use assessment (HLA). Scottish Geographical Journal, 125(1), 61–77. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/14702540902873907

- Higgs, A., & Usher, M. (1980). Should nature reserves be large or small? Nature, 285, 568–569. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/285568a0

- ICOMOS. (1994). The Nara document on authenticity. Nara: UNESCO.

- ICOMOS. (2004). The world heritage list: Filling the gaps – An action plan for the future. Paris: ICOMOS.

- IUCN. (2008). Implementing the conservation of biological diversity programme of work on protected areas: Governance as key for effective and equitable protected area systems. IUCN CEESP Briefing note 8, February ‘08.

- Jacques, D. (1995). The rise of cultural landscapes. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 1(2), 91–101. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13527259508722136

- Jones, M. (2003). The concept of cultural landscape: Discourse and narratives. In H. Palang & G. Fry (Eds.), Landscape interfaces: Cultural heritage in changing landscapes (pp. 21–51). Dordrecht: Springer.

- Linkola, H. (2015). Administration, landscape and authorized heritage discourse – Contextualising the nationally valuable landscape areas of Finland. Landscape Research, 40(8), 939–954. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2015.1074988

- Mascari, G., Mautone, M., Moltedo, L., & Salonia, P. (2009). Landscapes, heritage and culture. Journal of Cultural Heritage, 10(1), 22–29. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2008.07.007

- Mitchell, N., Rössler, M., & Tricaud, P. (2009). World heritage cultural landscapes: A handbook for conservation and management. Paris: UNESCO.

- Moylan, E., Brown, S., & Kelly, C. (2009). Toward a cultural landscape Atlas: Representing all the landscape as cultural. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 15(5), 447–466. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13527250903072781

- Opach, T. (2003). Map of the natural and cultural heritage 1:50.000 as a form of promoting ‘small homelands’. Geographica, 1, 331–337. https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=es&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Map+of+the+natural+and+cultural+heritage+1%3A50+000+as+a+form+of+promoting+%22small+homelands&btnG=

- Opach, T. (2004). The problem of cartographic representation in relation to the Polish cultural landscape. Miscellanea Geographica, 11, 301–310. doi: https://doi.org/10.2478/mgrsd-2004-0033

- Phillips, A. (1998). The nature of cultural landscapes – A nature conservation perspective. Landscape Research, 23(1), 21–38. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01426399808706523

- Phillips, A. (2003). Cultural landscapes: IUCN’s changing vision of protected areas. In P. Ceccarelli & M. Rössler (Eds.), World heritage papers 7. Cultural landscapes: The challenges of conservation (pp. 40–49). Paris: UNESCO.

- Plieninger, T., & Bieling, C. (2012). Connecting cultural landscapes to resilience. In T. Plieninger & C. Bieling (Eds.), Resilience and the cultural landscape: Understanding and managing change in human-shaped environments (pp. 205–223). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Plieninger, T., Höchtl, F., & Spek, T. (2006). Traditional land-use and nature conservation in European rural landscapes. Environmental Science & Policy, 9(4), 317–321. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2006.03.001

- Pressouyre, L. (1996). The world heritage convention, twenty years later. París: UNESCO Publishing.

- Priore, R. (2001). The background to the European Landscape Convention. In R. Kelly, L. Macinnes, D. Thackray, & P. Whitbourne (Eds.), The cultural landscape: Planning for a sustainable partnership between people and place (pp. 31–37). London: ICOMOS-UK.

- Rodrigo Cámara, J., Díaz Iglesias, J., Fernández Cacho, S., Fernández Salinas, V., Hernández León, E., Quintero Morón, V., … López Martín, E. (2012). Registro de paisajes de interés cultural de Andalucía. Criterios y metodología. Revista ph, 81, 64–75. doi: https://doi.org/10.33349/2012.81.3280

- Roe, M. (2013). Policy change and ELC implementation: Establishment of a baseline for understanding the impact on UK national policy of the European Landscape Convention. Landscape Research, 38(6), 768–798. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2012.751968

- Rössler, M. (2003). Linking nature and culture: World heritage cultural landscapes. In P. Ceccarelli & M. Rössler (Eds.), World heritage papers 7. Cultural landscapes: The challenges of conservation (pp. 40–49). Paris: UNESCO.

- Rössler, M. (2006). World heritage cultural landscapes: A UNESCO flagship programme 1992–2006. Landscape Research, 31(4), 333–353. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01426390601004210

- Sandström, U., & Hedfors, P. (2018). Uses of the word ‘landskap’ in Swedish municipalities’ comprehensive plans: Does the European Landscape Convention require a modified understanding? Land Use Policy, 70, 52–62. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.07.060

- Santé, I., Fernández-Ríos, A., Tubío, J., García-Fernández, F., Farkova, E., & Miranda, D. (2019). The Landscape Inventory of Galicia (NW Spain): GIS-web and public participation for landscape planning. Landscape Research, 44(2), 212–240. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2018.1444155

- Scazzosi, L. (2004). Reading and assessing the landscape as cultural and historical heritage. Landscape Research, 29(4), 335–355. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/0142639042000288993

- Schneider, G. (2001). Investigating historical traffic routes and cart-ruts in Switzerland, Elsass (Alsace, France) and Aosta Valley (Italy). The Oracle, 2, 12–22. https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Investigating+historical+traffic+routes+and+cart-ruts+in+Switzerland+Elsass+(France)+and+Aosta+Valley+(Italy)&publication+year=2001&author=Schneider+G.&journal=The+Oracle+(Journal+of+the+Grupp+Arkeologiku+Malti)&volume=2&pages=12-22

- Scott, A. (2011). Beyond the conventional: Meeting the challenges of landscape governance within the European Landscape Convention? Journal of Environmental Management, 92(10), 2754–2762. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2011.06.017

- Simensen, T., Halvorsen, R., & Erikstad, L. (2018). Methods for landscape characterisation and mapping: A systematic review. Land Use Policy, 75, 557–569. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.04.022

- Spanish Government. (2007). Ley 42/2007, de 13 de diciembre, del Patrimonio Natural y de la Biodiversidad. https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2007-21490

- Tieskensa, K., Schulpa, C., Levers, C., Lieskovský, J., Kuemmerle, T., Plieninger, T., & Verburg, P. (2017). Characterizing European cultural landscapes: Accounting for structure, management intensity and value of agricultural and forest landscapes. Land Use Policy, 62, 29–39. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.12.001

- UNESCO. (1992). Convention concerning the protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage. Report of the World Heritage Committee Sixteenth Session (Santa Fe, United States of America, 7–14 December 1992). Santa Fe: UNESCO.

- UNESCO. (1994). Operational guidelines for the implementation of the world heritage convention. Paris: UNESCO.

- UNESCO. (2007). Report and recommendations on integrity and authenticity of world heritage cultural landscapes. Aranjuez: UNESCO.

- UNESCO. (2017). Operational guidelines for the implementation of the world heritage convention. Paris: UNESCO.

- Vos, W., & Meekes, H. (1999). Trends in European cultural landscape development: Perspectives for a sustainable future. Landscape and Urban Planning, 46(1), 3–14. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-2046(99)00043-2

- Wu, J. (2010). Landscape of culture and culture of landscape: Does landscape ecology need culture? Landscape Ecology, 25, 1147–1150. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-010-9524-8