ABSTRACT

Legally protected by its own constitution since 1991, the greenbelt (or ‘GrünGürtel’) forms a ring of greenspace around Frankfurt, Germany and has been considered an effective reaction to municipal development pressures. As a response to Frankfurt’s embeddedness within a highly interconnected suburbanized region under extensive growth pressures, the Regionalpark RheinMain was established to upscale the greenbelt to the regional level. In this article, we explore the institutional complexities of upscaling a localized greenbelt to the regional scale in the Frankfurt Rhine-Main region, which is known for its fragmented institutional environment formed by numerous planning authorities and special purpose agencies with overlapping jurisdictions. Engaging with the literature on the governance of greenbelts from an institutional perspective, we analyse how the development of the Regionalpark RheinMain is shaped by horizontal, vertical and territorial coordination problems. We conclude that that the Regionalpark RheinMain is not appropriately institutionalized to serve as an effective regional greenbelt, resulting in localized initiatives and the delegation of greenbelt planning to municipalities.

Introduction

This article presents an institutional approach to explore the governance of regional greenbelts. By focusing on the institutional dimensions of regional governance and applying concepts of horizontal, vertical and territorial coordination to this research, this article aims to enrich regional governance literature both empirically, by focusing on regional greenbelts, and conceptually, through systematically addressing institutional problems in regional governance. To illustrate this argument, we explore a case study of regional greenspace planning in the Frankfurt Rhine-Main region which has been upscaled from the municipal Frankfurt greenbelt (or ‘GrünGürtel’) to the metropolitan Regionalpark RheinMain. Legally protected by its own constitution since 1991 and supported by nature conservation regulations, the Frankfurt greenbelt has been a successful response to municipal development pressures. However, this municipal greenbelt now hardly reflects Frankfurt’s embeddedness within a regionalized suburban environment – a sprawling landscape in-between a network of cities that form the Frankfurt Rhine-Main region. This polycentric region can best be characterized by what Sieverts (Citation2003) calls an ‘urbanized landscape’ or a ‘landscaped city’ – a mixture of developed and open spaces at the regional scale, under intense growth pressures that have recently been amplified by Brexit. This urban region, combining peripheral development and strong inter-municipal competition with a regional division of labour, faces considerable planning challenges: including the containment of development within its ‘system of central places’ and along regional growth and transportation corridors and as Germany’s main transportation hub. Within Frankfurt Rhine-Main’s suburban landscape, the municipal greenbelt can no longer be regarded as an effective solution for urban growth containment. Consequently, the Regionalpark RheinMain was established in 1994 with a mandate to safeguard regional greenspaces. The formation of the localized Frankfurt greenbelt has attracted academic attention (Husung & Lieser, Citation1996; Wei, Citation2017), while the Regionalpark RheinMain has been analysed regarding its policy ambitions but not the institutional challenges shaping its implementation (Dettmar, Citation2012; Rautenstrauch, Citation2015). However, the Frankfurt Rhine-Main region’s ambition to establish a regional greenbelt is particularly complex. As spatial strategies, the development of the regional greenbelt reveals key regional governance challenges. It requires not only a regulation of city–hinterland relationships but also between diverse interests associated with greenspace usage. These interests can range from providing recreational facilities, enabling new development and agriculture. From an institutional perspective, the governance of regional greenbelts overarches territorial jurisdictions of multiple municipalities and the Greater Frankfurt Planning Authority; it requires the coordination of multiple policy domains (e.g. nature conservation, land-use planning and transportation), private stakeholders and non-governmental organizations; and is shaped by policies from the municipal to the regional state (‘Länder’) levels. The regional governance challenges resulting from this ‘new generation’ of greenbelt schemes thus involve complex institutional problems of horizontal, vertical and territorial coordination that have rarely been addressed in the existing literature.

While some literature reflects the regionalism of greenbelts (Addie & Keil, Citation2015; Macdonald & Keil, Citation2012), the institutional complexities of regional governance are usually not discussed, with some exceptions (Röhring & Gailing, Citation2005). Therefore, we address this literature gap and bring together three concepts of institutional coordination – horizontal, vertical and territorial – to explore how the governance of greenbelts is shaped by their institutional environments. Based on an empirical case study of the Regionalpark RheinMain, the objective of this article is to explain how the governance of regional greenbelts is challenged by institutional arrangements within the Frankfurt Rhine-Main region. Thus, we ask: how could the development of the Regionalpark RheinMain be more effectively coordinated between different policy domains and their related stakeholders at multiple policy levels and across various municipal and special purpose agency jurisdictions? What lessons could be drawn for policymakers to improve greenbelt planning and for regional governance debates?

We examine these issues using a case study of regional greenspace planning in the Frankfurt Rhine-Main region, which has a reputation for its complex spatial planning system. This empirical research is based on a review of regional and state policy documents and promotional material about the Frankfurt greenbelt and the Regionalpark RheinMain. This was complemented by 37 interviews within the Frankfurt Rhine-Main region (September 2017–July 2019) with representatives from local, regional and state governments, environmental organizations and special purpose bodies. These interview participants were selected because they include all major interest groups involved in the Frankfurt greenbelt and Regionalpark RheinMain’s management. Discussions focused on how these greenspaces’ policy implementation has been influenced by coordination challenges between stakeholders at multiple policy levels and across numerous policy domains and municipalities’ jurisdictions. Using our conceptual framework, an analysis of the empirical literature was used to identify how the region’s institutional environment shapes greenbelt management. This article is organized as follows. First, we provide an overview of the literature on the governance of greenbelts focusing on institutional dimensions and introduce the conceptual framework applied to this research. Next, the governance and the institutional set-up of the Frankfurt greenbelt and Regionalpark RheinMain are outlined. Through a discussion of horizontal, vertical and territorial institutional coordination, we argue that the Regionalpark RheinMain is not appropriately institutionalized to serve as an effective regional greenbelt, resulting in activities being downscaled to the local level and the delegation of greenbelt planning to municipalities.

From urban to regional greenbelts

Urban regions around the world have responded to problems associated with rapid urbanization by developing numerous land-use policies to manage urban growth. Among those policies, the development of greenbelts has been an important approach to retain farmland and conservation areas surrounding cities. Greenbelts are designed to prevent urban sprawl by keeping undeveloped areas permanently open, to protect land for farming and recreation and to conserve natural habitats (Amati, Citation2008). The greenbelt concept is based on Ebenezer Howards’ Garden City idea with a focus on city-countryside separation and preserving greenspaces (Sturzaker & Mell, Citation2017). Following their 1930s introduction in UK planning policy, greenbelt principles spread internationally to locations such as Seoul, Melbourne, Toronto and Frankfurt (Sturzaker & Mell, Citation2017).

In recent decades, a ‘new generation’ of greenbelts has emerged from those UK policies which are based less on an industrial past, instead forming multi-purpose policy frameworks. Going beyond the traditional greenbelt policy goals of urban growth containment and farmland preservation, the expected benefits from this new generation of greenbelts include providing ecosystem services, mitigating and adapting to climate change and developing green infrastructures (Natural England and the Campaign to Protect Rural England, Citation2010). These multi-functional greenbelt policies are also expected to support urban regions’ economic competitiveness and contribute to regional identity by promoting landscape attractiveness (Macdonald & Keil, Citation2012). In several cases, these new generation greenbelts have been upscaled to be more regional in scope, reflecting recent trends of metropolitanization of urban growth (Macdonald & Keil, Citation2012) and regionalism (Addie & Keil, Citation2015), with expanding regions that see their settlement cores becoming increasingly interconnected. With greenbelt policies addressing multiple purposes, contemporary environmental management becomes institutionally more complex involving a network of government agencies, non-governmental organizations and public-private partnerships (Kortelainen, Citation2010).

Particularly in the German case, greenbelt planning shows some significant differences from the UK cases. As the rise of regional parks since the early 1990s demonstrates, greenbelts in Germany are often designed as strategies to contain urban growth and protect greenspace at ‘regional’ scales (Siedentop, Fina, & Krehl, Citation2016). These regional greenbelts have been developed to address the growing complexity of city-regions, as strong inter-regional competition increased development pressure on greenspaces with the municipal land-use planning system failing to reduce sprawl and greenspace loss (Gailing, Citation2007). Apart from often being at the regional scale, German greenbelt management is characterized by limited legal requirements or guidance from the national government (Siedentop et al., Citation2016). As both greenbelts and regional parks are not formally defined under national nature conservation or spatial planning laws, regional and municipal authorities have flexibility in their implementation resulting in heterogeneous planning practices (Siedentop et al., Citation2016). In particular, regional parks are project-oriented landscape development strategies whose features include the multi-functionality of different land-uses as well as their strengthening of regional competitiveness and identity (Gailing, Citation2007). Prominent examples include the Emscher Landscape Park, the Regionalpark RheinMain and the Berlin-Bradenburg regional parks. In contrast to traditional greenbelt policies, these regional parks represent specific forms of greenspace governance which are designed to complement formal spatial planning and nature conservation policies (Gailing, Citation2007). Strong cooperation is necessary for successful regional park development, as these regional greenbelts are designed as inter-authority initiatives involving collaboration between state, regional and municipal authorities, along with private and civil society stakeholders (Gailing, Citation2007). These greenbelts thus involve coordination across multiple policy domains, various jurisdictions and between policy levels. They challenge government-led forms of greenbelt planning and include collaborative arrangements with private and civil society stakeholders, which are increasingly involved in greenbelt management that was previously the primary purview of the state.

Institutional complexities and the governance of regional greenbelts

Given the conditions of increasingly multi-purpose greenbelts involving arrangements between numerous stakeholders, we argue that applying a regional governance lens is most appropriate when studying German greenbelt development. Similar to broader regional development processes, it can be argued alongside Willi, Pütz, and Müller (Citation2018, p. 12) that the governance of regional greenbelts happens through ‘network-like coordination […] processes and comprises vertical and horizontal coordination of state and non-state actors in a functional space.’ To understand the challenges involved in governing new generation greenbelts, it becomes necessary to analytically shift the focus away from hierarchical systems of the state government to include more networked arrangements bringing an array of stakeholders into policy analysis (Stoker, Citation1998). Based on the observation that state responsibilities in greenbelt management have been partially redistributed to non-state actors who operate at different geographical scales and whose scope crosses jurisdictional borders (Kortelainen, Citation2010), this indicates a re-scaling of decision-making to address regional problems (Brenner, Citation2003). However, managing the interdependencies between the various institutions and stakeholders involved in new generation greenbelt management creates coordination challenges.

The governance of regional greenbelts is significantly shaped by their institutional environments – an aspect that has hardly been addressed in current literature (exceptions with regards to German and UK cases include Röhring & Gailing, Citation2005 and Mace, Citation2018). Institutional environments shape the model of greenbelt planning used in that city or region, influencing greenbelt policy implementation (Han & Go, Citation2019). Behind all the stakeholders involved in greenbelt governance are institutions, which we define as the practices and rules that are situated within structures that are relatively resilient in the face of changing external circumstances (March & Olsen, Citation2011). Thus, institutions distribute power relations, enable and constrain actors and create order (March & Olsen, Citation2011). What constitutes an institution varies across the disciplines, yet the focus in all institutional analyses is on the connection between institutions and actors’ behaviour and exploring how institutions are established and change (Hall & Taylor, Citation1996). Institutions provide the structures necessary for governance, as institutional arrangements shape actors’ interactions and influence the outcomes of those interactions (Hohn & Neuer, Citation2006). Within governance debates, institutions are seen as key elements of metropolitan governance, yet questions remain about which institutional arrangements are best to address regional problems (Galland & Harrison, Citation2020). Prominent institutional perspectives within the governance literature include the metropolitan reform model, the public choice school and new regionalism, which each advocate different approaches to governing city-regions (see Glass, Citation2018; Nelles, Citation2012). Once established, urban planning-related institutions can become increasingly hard to change over time (Sorensen, Citation2015). Thus, as stakeholders see greenbelt policies sustained for years, they adjust their behaviours accordingly, particularly landowners within a greenbelt which have the assurance that development is unlikely to occur within these protected areas (Mace, Citation2018).

Through applying an institutional lens to greenbelt development, we identify three institutional dimensions impacting the effectiveness of regional greenbelt governance.Footnote1 ‘Horizontal coordination’ results from interdependencies between institutions at the same policy level – municipal, regional or state. The number of policy fields affected through horizontal interactions complicates greenbelt management, which includes spatial planning, nature conservation and transportation and their associated stakeholders in the public, private and civil society sectors. Institutions are often created within siloed policy domains without considering their interdependencies with other policy fields, leading to conflicts affecting regional parks (Röhring & Gailing, Citation2005). At the same time, greenbelt governance is often strongly influenced by powerful private stakeholders such as developers (Cadieux, Taylor, & Bunce, Citation2013), resulting in stakeholder self-interests impacting policy implementation.

‘Vertical coordination’ results from the interdependencies between institutions at different policy levels – municipal, regional or state. A significant issue affecting regional greenspace governance is that the vertical institutional design of regional greenbelt policies requires cooperation between stakeholders at different policy levels. However, as greenbelt policies are usually set by a higher-level government and then implemented by a lower-level of government, coordination problems between these stakeholders can cause implementation issues (Carter-Whitney, Citation2010).

There is also a need for territorial coordination between institutions as regional greenspaces do not match boundaries of municipal or regional jurisdictions, but often cross jurisdictional borders, resulting in institutional ‘misfits’ (Röhring & Gailing, Citation2005; Young, Citation2002). Thus, regional greenbelt management requires ‘territorial coordination’ across multiple municipal and special purpose bodies’ jurisdictions, which influences policy implementation. Greenbelt management can also be hindered by conflicts arising along boundaries between institutions and the interaction of stakeholders from multiple policy fields, which can have separate yet overlapping memberships. Each of these types of coordination is contested, involving entrenched power relations. Combining these three forms of institutional coordination allows for an analysis of the difficulties of greenbelt management as well as to examine the institutional problems associated with regional greenbelt governance, which will be discussed later in the article.

The governance of the Frankfurt greenbelt and Regionalpark RheinMain

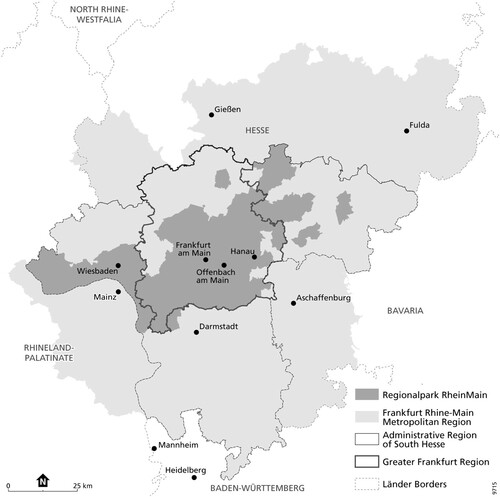

This section outlines how the Frankfurt greenbelt and Regionalpark RheinMain are embedded within the Frankfurt Rhine-Main region’s complex institutional environment. The greenbelt is located within the City of Frankfurt, which has approximately 740,000 residents and is the largest among the 75 municipalities forming of the Greater Frankfurt region (Regionalverband, Citation2018). As a politically defined territory of the Regional Authority Frankfurt Rhine-Main, the Greater Frankfurt region has 2.34 million people (Regionalverband, Citation2018), including a network of cities (Frankfurt and Offenbach), smaller towns and the government centres of Wiesbaden, Mainz and Darmstadt. The City of Frankfurt constitutes the biggest urban node in the Frankfurt Rhine-Main Metropolitan region – established to strengthen the region’s international competitiveness – which has 5.7 million inhabitants and 468 municipalities (Diller, Citation2016; Regionalverband, Citation2018) (). In recent years, the Greater Frankfurt region has experienced strong demographic growth and is expected to grow by 191,000 inhabitants by 2030 (Regionalverband, Citation2018). Frankfurt has significant functional interdependencies with its surrounding region through commuter flows, a regional division of labour and the suburbanization of service industries. Other than the Frankfurt greenbelt and the Regionalpark RheinMain, the Frankfurt Rhine-Main region has a greenspace network including the Offenbach greenbelt, the Nature Park Hochtaunus and the Hessische Ried agricultural area.

Figure 1. Frankfurt Rhine-Main Metropolitan Region and the Greater Frankfurt Region. Source: Regionalverband (Citation2018).

The governance of regional greenspaces in the Frankfurt Rhine-Main region is strongly shaped by regional institutional reform and organized through inter-municipal planning. Already in 1975, the state government forced 43 municipalities in the Greater Frankfurt Area to collaborate within the ‘Umlandverband Frankfurt’ (Greater Frankfurt Association). Faced with the increasing embeddedness of Frankfurt within a metropolitanized region, multiple municipal planning tasks were upscaled to the level of the Greater Frankfurt Area. The ‘Umlandverband Frankfurt’ was the planning association responsible for the creation and initial management of the Regionalpark RheinMain in the early 1990s, including 43 municipalities and 1.5 million residents until its dissolution in 2001 (Freund, Citation2003). In 2001, the state government created an enlarged Greater Frankfurt Region with 75 municipalities. A new planning association was installed, the ‘Planungsverband Ballungsraum Frankfurt/RheinMain’, which briefly managed the Regionalpark RheinMain in the early 2000s. Due to the Umlandverband’s alleged inefficiencies, the responsibility for several public services that were previously concentrated in the Umlandverband were either ‘re-municipalized’ or delegated to a plethora of voluntary inter-municipal agencies and special purpose organizations (Monstadt, Zimmermann, Robischon, & Schönig, Citation2012). This also applies to the development of the regional greenbelt whose management is not overseen by a government administration but has since 2005 been delegated to a special purpose organization, ‘the Regionalpark Ballungsraum RheinMain GmbH’. Other responsibilities delegated to such single-purpose organizations include the provision of water, waste and transportation services, and promoting business development activities, which operate within task-specific geographies and often only partly overlapping jurisdictions (Hoyler, Freytag, & Mager, Citation2006; Monstadt et al., Citation2012). In 2011, the Planungsverband was disbanded and a new regional institution was created, known as the Regional Authority (‘Regionalverband FrankfurtRheinMain’). The Regional Authority prepared a regionalized land-use plan and landscape plan for its 75-member municipalities and 2.34 million residents in the Greater Frankfurt region.

While the city of Frankfurt held the responsibility for land-use planning within its jurisdiction when the Frankfurt greenbelt was designed, the Regionalpark RheinMain is influenced by various levels of spatial planning policies by its member municipalities, the Regional Authority and the state government. The Regional Authority developed a regionalized land-use plan (‘regionaler Flächennutzungsplan’) that came into effect in 2011, replacing previous municipal plans in its member municipalities. The result is that these cities need to negotiate their interests at the regional scale. Drawing on the German ‘central place system’ principle in spatial planning (Schmidt, Siedentop, & Fina, Citation2018), the regionalized land-use plan prioritizes development within existing urban areas and along transportation corridors, securing greenspaces and expanding the Regionalpark RheinMain (Regierungspräsidium Darmstadt and Regionalverband, Citation2010). Organized by a ‘counterflow principle’ in which the federal, state and municipal levels influence each other’s plans (Schmidt, Citation2009), the State development plan for Hesse (‘Landesentwicklungsplan’) and the regional plan for South Hesse set general objectives, which are detailed in the regionalized land-use plan. Both the regionalized land-use plan and spatial development plan by the state government include policies protecting the Regionalpark RheinMain and Frankfurt greenbelt.

This greenbelt and Regionalpark are strongly shaped by nature conservation and landscape planning policies. The Federal Nature Conservation Act is the main source of German nature conservation law. Landscape planning runs parallel to the spatial planning system at the Länder, regional and municipal levels and landscape plans only become binding when they are integrated into spatial planning policies (Federal Agency for Nature Conservation, Citation2008). An important principle of German nature conservation law is that greenspace destruction through development must be compensated for by the person or organization responsible for that project, in case it cannot be avoided (Rautenstrauch, Citation2015). Both the Frankfurt greenbelt and the Regionalpark RheinMain have benefited from these compensation policies, particularly because of the airport extension, further securing their protection.

From the Frankfurt greenbelt to the Regionalpark RheinMain

The histories of the Frankfurt greenbelt and Regionalpark RheinMain reflect regionalization processes within the Frankfurt Rhine-Main region over the past three decades. The Frankfurt greenbelt is an 8000-hectare protected greenspace forming a 70-km belt around the city. Apart from endangered species protection, the conservation of cultural landscapes and its function as a fresh air corridor, there is a focus on recreation within the greenbelt. Influenced by planner Ernst May’s work, the greenbelt has an extended history including the forest to the south of Frankfurt and two previous smaller greenbelts (Wei, Citation2017). As one of the most important environmental policies of a newly elected coalition of Frankfurt’s Social Democrats and Green Party in 1989, the current greenbelt was a product of an innovative planning process overseen by both the office of Tom Koenigs (the Head of the Environment Department) and the GreenBelt Project office, and approved by city council (Ronneberger & Keil, Citation1993). In 1991, the Frankfurt City parliament unanimously passed the ‘GreenBelt constitution.’ A key principle of this legally non-binding agreement was to refrain from development and, if not feasible, to compensate for land removed from the greenbelt by adding land of the same size and quality to the greenbelt elsewhere (Husung & Lieser, Citation1996).

Following a period of management by the ‘GreenBelt GmbH’, the GreenBelt Group – a collaboration of 13 staff members within multiple city departments – has been responsible for greenbelt development since 1997. It has an annual budget of €200 thousand for investments in new construction or maintenance and shares €150 thousand per year with other departments for planning programs (Interview 1). The greenbelt is strongly protected under spatial planning and nature conservation regulations. Through the designation as an area under protection by the Federal Nature Conservation Act, the greenbelt and areas in neighbouring municipalities enjoy far-reaching building restrictions that are adopted in municipal, regional and state spatial plans. Making land-use changes to the greenbelt is thus difficult as this requires amendments at numerous policy levels given that greenbelt policies are included in the regionalized land-use plan and the state development plan for Hesse (Interview 2). In 2015, the ‘Spokes and Rays’ (‘Speichen und Strahlen’) Plan released an updated greenbelt concept making stronger connections between the Frankfurt greenbelt and regional greenspaces (Stadt Frankfurt am Main, Citation2015), although ultimately, this plan was not adopted. Similar greenspace developments took place in Offenbach, which developed its green ring (‘Grünring’) before Frankfurt’s greenbelt. Enclosing the city’s core and connecting greenspaces along the Main river, the green ring was initially protected in Offenbach’s 1984 land-use plan, later included in the Regionalpark RheinMain in 2000 and secured in the Regional Authority’s landscape plan (Stadt Offenbach, Citation2017). Despite several regional reforms (see above), greenspace policies in the Greater Frankfurt region have mostly adhered to traditional municipal or regional jurisdictions. However, regional policymakers have long recognized its greenbelt’s regional connections, with Frankfurt’s or Offenbach’s localized greenbelt policies no longer reflecting the highly interconnected regional context within which these greenspaces are situated. The establishment of the Regionalpark RheinMain can thus be seen as a response to the increasingly metropolitanized region and as an ambition to upscale localized initiatives to a (more functional) regional scale and to integrate them into a regionalized greenspace network.

Similar to other German regions, the Greater Frankfurt greenbelt is called a Regionalpark. The Regionalpark RheinMain stretches across the metropolitan region as a green corridor network reaching to the Nature Park Hochtaunus. Comparable to traditional greenbelt policies such as those in the UK, the Regionalpark was designed to protect regional greenspaces, provide recreational spaces (Dettmar, Citation2012) and to control the direction of development (Interview 3). The Regionalpark also includes contemporary greenbelt policy goals such as contributing to economic development and promoting regional identity. However, since the Regionalpark is comprised of a regional greenspace network, it differs from one of the main purposes of traditional greenbelts, as its policies were not intended to create a boundary around the growth of a city. Approved in 1994 by the Umlandverband and following a transitional period of management by the Planungsverband, a regional greenbelt agency (‘Regionalpark Ballungsraum RheinMain GmbH’) was founded in 2005 (Rautenstrauch, Citation2015). The Regionalpark is coordinated by this agency, which was planned as a public-private partnership with its implementation delegated to six inter-municipal implementation bodies that are responsible for developing sub-projects. The greenbelt agency is supported by 15 shareholders, including 123 municipalities, the Regional Authority and the state government, which each pays an annual fee to the company (Dettmar, Citation2012). The financial model of the greenbelt agency is based on an annual contribution of €75 thousand from each of its shareholders, the Regional Authority and the state government, amounting to €1.25 million per year (Interview 4). The remaining budget comes from Fraport AG’s contribution – the operator of Frankfurt’s airport – and since 1997 the only private sponsor for the park (Dettmar, Citation2012). In 1997, Flughafen AG (now known as Fraport AG) established a voluntary fund for nature conservation projects, giving the Regionalpark top priority (Rautenstrauch, Citation2015). Fraport has provided approximately €800 thousand per year to the greenbelt agency and as of 2016, €17 million from this fund has gone to the park (Dettmar, Citation2012; Krug, Citation2016). However, the Fraport AG has announced its intention to reduce its contribution to €400 thousand per year in 2020 and to fully withdraw from financing the greenbelt in 2021 (Interview 5).

The size of the Regionalpark has increased significantly since its introduction. Starting with 3 municipalities, it grew to 129 municipalities by 2012 (Dettmar, Citation2012) and is currently 4463 km2. As the greenbelt agency has no planning authority over its territory, its staff must consult with the Regional Authority and the Regional Planning Authority for South Hesse to ensure that its greenspaces are integrated into spatial planning policies. However, despite the strong German spatial planning system, the Regionalpark RheinMain is only weakly protected. Its only formal protection is under the land-use category of ‘regional green corridors’ (‘Grünzüge’) in the regional plan for South Hesse and the regionalized land-use plan. Also, several areas within the Regionalpark are protected by different types of nature conservation areas with varying levels of protection. The Regionalpark’s establishment and development was strongly supported by key individuals such as Lorenz Rautenstrauch. These individuals’ commitment over the past three decades and the creation of informal networks of public, private and civil society stakeholders supporting park projects contribute to the fact that the Regionalpark still exists today.

The complexities of planning a greenbelt for the Frankfurt Rhine-Main region

In this section, we explore how institutional coordination at various policy levels and between public and private actors across numerous municipalities in the Frankfurt Rhine-Main region impact the Regionalpark’s implementation. Through a discussion of institutional coordination at different policy levels, between several policy fields and across administrative jurisdictions related to the Regionalpark, we analyse the challenges involved in planning a regional greenbelt for Frankfurt Rhine-Main.

Horizontal coordination: how interdependencies between policy fields influence Regionalpark implementation

The Regionalpark RheinMain’s management is complicated by connections to numerous policy fields including nature conservation, economic growth and their related stakeholders in the public, private and civil society sectors. First, the Regionalpark is displayed prominently within nature conservation policies. One of the regionalized landscape plans’ main targets in securing greenspaces is through the park, giving priority to nature compensation measures within the Regionalpark and the Frankfurt and Offenbach greenbelts (Planungsverband, Citation2001). By integrating the Regionalpark into the regionalized landscape and land-use plans, planners are required to incorporate these objectives into local policies, reinforcing park protection (Gailing, Citation2007). However, the region’s landscape plans are outdated and do not reflect the current regional conditions, as the Regional Authority’s most recent landscape plan is from 2001.

Also, the Regionalpark is promoted beyond nature conservation policies as an important mechanism contributing to economic development strategies. The Frankfurt and Offenbach greenbelts and Regionalpark promote regional attractiveness, which is becoming increasingly important to regional competitiveness, particularly considering Brexit and the resulting ambitions by municipal and Länder governments to incentivize businesses to relocate from London to Frankfurt. The regionalized land-use plan states that so-called ‘soft location factors’ such as greenspaces contribute to regional competitiveness and that the Regionalpark is a ‘significant soft location factor that improves the image of the region’ (Regierungspräsidium Darmstadt and Regionalverband, Citation2010, p. 89).Footnote2 The Strategic Vision ‘Frankfurt/RheinMain 2020’ also promotes landscapes such as the Regionalpark and supports greenspace protection (Planungsverband and Regierungspräsidium, Citation2005). Frankfurt’s ability to attract investment rests on the region’s capacity to provide a range of supportive services, while the region’s economic competitiveness and inter-municipal competition are linked to its polycentric structure (Hoyler et al., Citation2006). In practice though, power asymmetries between Frankfurt and its neighbouring municipalities often challenge the institutionalization of regionalism within the Greater Frankfurt region (Keil, Citation2011).

At the same time, the Regionalpark’s implementation is vulnerable through its financial dependency upon the airport operator Fraport. It has recently been decided that Fraport’s funding to the park will end in 2021 (Interview 5). In response, the park’s shareholders have pledged to increase their annual payments in the next few years to compensate for Fraport’s funding withdrawal (Interview 5). However, no long-term official decisions have been made as of the time of writing. This financial uncertainty currently affecting the Regionalpark reflects a larger concern within greenbelt planning. While there is an increasing reliance upon public-private partnerships in environmental management, the Regionalpark’s financial structure highlights the weakness of this governance model, given that greenbelt policy implementation can be threatened by shifting funders’ priorities.

In addition to the complexities created by horizontal connections to nature conservation and economic policies, the Regionalpark’s effective implementation is vulnerable to the region’s powerful growth politics. Regional greenspaces are under increasing pressure due to the regional housing shortage. Despite strong spatial planning policies, the inter-municipal land-use planning system has failed to contain suburbanization, and development patterns are influenced by local growth coalitions and municipal competition for taxes, resulting in a spatially fragmented suburban landscape (Monstadt & Meilinger, Citation2020). This is particularly a problem since the greenbelt agency has no planning authority to confine regional growth patterns. In the past 25 years, there have been few cases of Regionalpark land being lost to development (Interview 4). Regional politicians have generally adhered to these policies, seeing the park as a regional asset (Interviews 4 and 6). However, long-held views on the firm protection of regional greenspaces are beginning to shift, as these natural areas may no longer be considered ‘untouchable’ to future development (Interview 7). Thus, the strong dynamics of regional growth politics, the Regionalpark’s weak institutional design and shifting opinions on greenspace protection combine to make park’s policies vulnerable to local self-interests.

In summary, as the Regionalpark policies intersect with numerous policy domains, this increases the number of stakeholders involved in park management. However, this process can create conflicting demands between policy goals, with some stakeholders disproportionately influencing Regionalpark implementation.

Vertical coordination: collaboration challenges between policy levels results in localized greenbelt initiatives

To effectively manage a regional greenbelt, coordination between stakeholders is needed at multiple policy levels including municipal, regional and state governments. However, analysis of the Frankfurt Rhine-Main’s governance arrangements reveals significant tensions in vertical interactions between institutions at these different policy levels. These coordination problems challenge the ability to have an effective regional greenbelt, resulting in the delegation of greenbelt planning to the local level. The strong connections between multiple policy fields at different policy levels that promote nature conservation and compact development, at first glance, appear to promote favourable conditions within the Frankfurt Rhine-Main region for a regional greenbelt to emerge. However, further investigation shows that vertical coordination issues between state, regional and local authorities create challenges for greenbelt implementation. Nonetheless, on the positive side, the German spatial planning system restrains municipal growth, as development approvals require either respective designations as building areas in land-use plans or changes of such plans, which require approval by upper-tier planning authorities. Moreover, the Federal Nature Conservation Act provides several instruments to protect greenspaces including a multi-tier system of landscape planning at the Länder, regional and municipal level, a system of protected areas and compensation schemes for the destruction of nature. The Frankfurt and Offenbach greenbelts, and Regionalpark RheinMain are protected by a system of protected areas and their development is promoted by the landscape plan at the inter-municipal level.

However, the agency managing the Regionalpark has only limited authority over its member municipalities to effectively implement a regional greenbelt. On the one hand, regional greenbelt management is coordinated by a special purpose body with limited planning authority, staff and resources, and these resources became further strained by increasing membership (Dettmar, Citation2012). The main institutional resources and the authority to designate protected areas, to confine urban growth and to develop greenspaces are horizontally and vertically distributed between nature conservation and spatial planning authorities at different levels. On the other hand, Regionalpark implementation has been delegated to six inter-municipal implementation bodies, giving municipalities more freedom in developing their own sub-projects. Given its weak institutionalization, the greenbelt agency’s mandate shifted to tourism promotion since 2008 from its original focus on protection from development (Rautenstrauch, Citation2015).

A weakness in the vertical institutional design of regional greenbelt management is that the state government (and its spatial planning authorities at the Länder level and level of South Hesse) has no active role in greenbelt development. However, the Regional Authority has greater involvement in Regionalpark planning as its staff collaborates with the greenbelt agency on relevant projects (Interview 6) and the Regionalpark is integrated into the regionalized land-use and landscape plans. Apart from this collaboration with spatial planning and nature conservation authorities, the greenbelt agency has no power to enforce compliance to its goals, making it vulnerable to local self-interests. However, there appears to be no desire by the state government or the Regional Authority to give more powers or resources to the greenbelt agency (Interview 6), and municipalities would likely resent further development restrictions (Interview 5). Because of these factors, the Regionalpark RheinMain faces considerable institutional challenges in effectively fulfilling a mandate in regional growth and greenspace management.

With these concerns in mind, the Regional Authority seems to be the appropriate organization to manage a regional greenbelt, given its mandate in metropolitan development, its planning authority for the Greater Frankfurt region and its policies on nature conservation and smart growth as formulated in its regionalized land-use and landscape plans. However, the Regional Authority’s capacity for effective growth management is challenged by its embeddedness within a complex and fragmented institutional environment including state, municipal and special purpose organizations. The Regional Authority as an inter-municipal body established by the state government needs to coordinate not only with its 75-member municipalities but also with the region of South Hesse and the state government, each of which has their own development interests (Monstadt & Meilinger, Citation2020). Thus, while the Regional Authority has the statutory powers to define land-use and has more resources available than a special purpose body does, it also faces challenges that would impact regional greenbelt management.

Due to these institutional constraints that influence the effectiveness of regional greenbelt implementation, key authority for greenbelt planning is de facto with the municipalities. Here, particularly the Frankfurt greenbelt has been successful in that almost no land has been lost to development since its introduction (Wei, Citation2017). However, given the local scale of the Frankfurt greenbelt, it cannot effectively manage regional growth, nor was it designed to address regional concerns. Thus, if regional authorities want to achieve the benefits a regional greenbelt could offer, localized initiatives such as the Frankfurt greenbelt cannot realize those goals. The discussion about horizontal and vertical coordination reveals the challenges of implementing a regional greenbelt within the Frankfurt Rhine-Main region. Ultimately, greenbelt planning must occur at the regional scale and must be properly institutionalized with strong regulatory protection.

Territorial coordination: coordination problems across jurisdictions results in the downscaling of activities to the local level

Frankfurt Rhine-Main provides a perfect case to study a common regional governance problem: the misalignment of administrative and functional spaces (Nelles, Citation2012). These institutional misfits create coordination challenges with conflicts arising along these overlapping boundaries. The Regionalpark RheinMain and its institutional arrangements contain misfits, given that it is situated within various layers of regional governance structures including multiple municipalities, the Regional Authority and the regional planning authority of South Hesse – none of which match the boundaries of the park (). For example, when the Regionalpark was created, two cities – Darmstadt and Mainz – were excluded. Neither city was part of the Umlandverband, which could only finance projects within its own boundaries (Interview 4). However, the city of Wiesbaden is located within the Regionalpark, yet it is not within the jurisdiction of the Regional Authority (see ) (Interview 5). An additional layer of territorial complexity is that the Regionalpark is part of a larger regional greenspace network including the Frankfurt and Offenbach greenbelts, a national park, a biosphere reserve and nature parks, each having different and partially overlapping territorialities.

Figure 2. The fragmented regional governance landscape in Frankfurt Rhine-Main. Source: Regionalverband (Citation2018) and Regionalpark RheinMain GmbH.

Navigating these multi-layered territorialities presents significant governance challenges for the greenbelt agency, as it must coordinate with municipal, regional and state agencies. For example, coordination is complex when the greenbelt agency tries to promote its activities, resulting in staff contacting eight tourism organizations that overlap the park’s area. Thus, collaborating with many organizations challenges the delivery of a consistent message to the public (Interview 5). Analysing the Regionalpark reveals a regional governance landscape within the Greater Frankfurt region that has multiple administrative jurisdictions overlapping with geographies of special purpose bodies. While the Greater Frankfurt region has undergone waves of governance reforms, the territorial scope of its planning associations has only partially reflected functional relationships. Moreover, special purpose organizations’ jurisdictions often do not coincide with the planning association’s borders, reinforcing inter-municipal competition (Freund, Citation2003; Nelles, Citation2012).

Because of these institutional misfits, a coping mechanism has been to downscale activities to the local level. Park project development has been delegated to the municipal scale, as inter-municipal implementation bodies are responsible for delivering these activities. At the local level, governance processes are facilitated by providing stakeholder participation opportunities for farmers, park users and businesses, particularly through the park’s popular educational programs (Krause, Citation2014). Also organized at this scale are civil society initiatives for nature conservation, which are historically rooted in local engagement activities. Examples are BUND – the Federation for Environment and Nature Conservation (‘Bund für Umwelt- und Naturschutz e.V.’), NABU – the German Association for Nature Conservation (‘Naturschutzbund Deutschland e.V.’) and initiatives for the protection of the Taunus, which are either organized at the scale of neighbourhoods, cities, municipal districts (‘Kreise’) or the state level of Hesse. While they have been effective in lobbying for the Frankfurt and Offenbach greenbelt or the Nature Park Hochtaunus, their engagement with regional issues have been mostly limited to protests against the airport extension. However, regional environmental issues such as regional greenspace conservation overreach local groups’ jurisdictions, thus regional greenbelt initiatives are largely absent.

Also missing is public awareness about the Regionalpark, resulting in part due to this greenspace’s vast territorial scope. Indeed, the increasing size of the park and member municipalities’ diverging interests influenced the greenbelt agency’s decision to concentrate its resources on the area of the park within the agglomeration to increase public awareness (Interview 6). This lack of recognition reflects the Greater Frankfurt region, which ‘remains internally fragmented both politically and administratively and lacks a clear regional identity’ (Hoyler et al., Citation2006, p. 133). To conclude, there will never be a perfect fit between administrative and functional boundaries, thus numerous mechanisms are needed to overcome these institutional mismatches. However, the Frankfurt Rhine-Main region’s complex and overlapping institutional structures present significant challenges to finding effective strategies to overcoming institutional misfits, resulting in the downscaling of greenbelt activities to the local scale to address issues in a simpler institutional context.

Conclusion

This article examined the institutional complexities of upscaling a greenbelt to the regional scale in the Frankfurt Rhine-Main region, shaped by horizontal, vertical and territorial coordination problems. By exploring these three dimensions, we analysed the institutional challenges of regional greenbelt governance, which showed the diverse policy fields affecting greenbelt implementation, the interdependencies between institutions at different policy levels and territorial misfits. Embedded at the interface of multiple policy domains, the Regionalpark’s implementation is affected by inter-policy conflicts. While nature conservation authorities and environmental groups promote greenspace protection, powerful economic development policies and their related private stakeholders lobby against land-use restrictions. Coordination problems between stakeholders at different policy levels and across municipal and special purpose bodies’ territorial jurisdictions create significant challenges for Regionalpark management, resulting in localized initiatives. Also, several factors negatively influence its implementation including weak policy protection and the greenbelt agency’s lack of spatial planning authority, low staffing levels, fiscal uncertainty and its embeddedness within a fragmented institutional environment. In a region with a history of land-use conflicts affecting greenspaces (e.g. airport runway expansions), the greenbelt agency made a decision to concentrate its activities on an uncontroversial tourism mandate and moved away from its initial focus of the park serving as a buffer from urban sprawl, thus trying to avoid conflicts with other organizations. Therefore, we conclude that the Regionalpark RheinMain’s agency is not properly institutionalized to manage an effective regional greenbelt, resulting in a delegation of greenbelt planning to the municipal level. Progressive for their time, the Frankfurt and Offenbach greenbelts were significant steps in urban environmental protection. However, as both cities are now embedded within a region experiencing extensive growth pressures, more ambitious efforts are needed to effectively manage regional greenbelts.

When assessing the effectiveness of the Regionalpark RheinMain to serve as a regional greenbelt, it is important to reflect upon what its original purposes were, which included protecting greenspaces from development and providing recreational opportunities (Rautenstrauch, Citation2015). While the multi-layered spatial planning system has been moderately effective in directing development away from greenspaces and minimal land within the Regionalpark has been lost to urban growth (Interview 4), we find that it is unlikely that the park can fulfil larger ambitions as a regional greenbelt.

Traditionally, greenbelt policies were designed as an urban growth buffer through restrictive land-use planning instruments that provide long-term protection against urban development. In contrast, regional park policies reflect more flexible institutional arrangements, providing municipalities much leeway in park project implementation. As Frankfurt Rhine-Main is a polycentric region experiencing substantial peripheral growth pressures, the spatial shape of a traditional urban greenbelt forming a ring of greenspace separating a central city from the surrounding countryside is no longer suitable. Instead, similar to other international greenbelts such as that in Milan, a regional greenspace network is more appropriate for these current regional conditions. However, regional greenbelts require adequate institutional arrangements to contain growth and protect greenspaces at a regional scale.

While Frankfurt Rhine-Main would benefit from a regional greenbelt, overly complex arrangements in the governance of the Regionalpark make this goal almost impossible to achieve. Thus, our research indicates that the Regionalpark agency’s institutional design as a special purpose body does not enable effective regional greenbelt implementation. Accordingly, strategies could be applied to improve the existing situation. First, Regionalpark policies need to be monitored and evaluated to assess their effectiveness in meeting their policy goals and then updated regularly based on this data. Also, the greenbelt agency could capitalize on the park’s potential to provide ecosystem services and create educational programs promoting these features. Finally, the greenbelt agency could build upon their successful relationships with local stakeholders to diversify their collaborations beyond their tourism mandate. Thus, the greenbelt agency could form strategic partnerships with nature conservation authorities, environmental groups and agriculture and forestry-related organizations, which would allow this agency to pool resources together with relevant stakeholders to create larger programs supporting the Regionalpark.

However, these are only incremental strategies aimed at improving the existing situation, and institutional reforms are required to develop the Regionalpark into an effective greenbelt that confines (sub)urban growth. Regional greenbelt planning should be re-integrated into the Regional Authority (‘Regionalverband FrankfurtRheinMain’), as they have the authority for spatial and landscape planning in Greater Frankfurt and can lead strategically important processes for the metropolitan region such as facilitating cooperation amongst regional companies. The Regionalpark has a well-established history with the Regional Authority, as it was previously managed by its predecessor (‘the Planungsverband’), and staff from the greenbelt agency and Regional Authority already work together on park planning. If the Regional Authority were to be given more authority and resources to effectively manage the Regionalpark (e.g. by integrating the greenbelt agency as its own department within the Regional Authority), the park could reinforce the growth management goals of the regionalized land-use plan and this reform could partially reduce regional institutional fragmentation. Although not having the formal responsibility for greenbelt development, the Regional Authority currently complements the soft approach of the regional greenbelt agency by its formal planning instruments that are used to protect open spaces from urban sprawl. These include the designation of nature conservation areas or the use of financial compensation schemes for the destruction of greenspaces through nature conservation policies or the designation of Priority and Reserve Areas (‘Vorrang- und Vorbehaltsgebiete’) for agriculture, nature and landscape and green corridors in regional plans. Hereby, it would be more efficient to concentrate key responsibilities for the Regionalpark with the Regional Authority, as it could synergistically combine hard and soft planning approaches in greenbelt governance. However, regional greenbelt development cannot be effectively sustained by the Regional Authority alone without the support of civil society initiatives. The localized scope of nature conservation groups in the Frankfurt Rhine-Main region and their limited engagement with regional issues are thus important challenges to overcome. Regional collaboration of these localized environmental groups is equally important to effectively support regional greenbelt implementation.

The Frankfurt case provides insights for regional governance debates related to greenbelts and institutions. Within the regional governance literature, there is a greater focus on more flexible institutional arrangements including soft spaces of governance (Zimmerbauer & Paasi, Citation2019) and the increased use of special purpose agencies to provide public services (Lucas, Citation2016). Urban regions have thus become increasingly institutionally fragmented with numerous authorities at multiple policy levels, which creates governance problems (Storper, Citation2014). However, our research indicates that these flexible and collaborative arrangements can also entail ‘governance failures’ (Jessop, Citation2000) and that more effective institutional frameworks are required to ensure regional greenbelt management. Special purpose agencies often have limited authority and institutional capacity, can contribute to regional fragmentation and may not be situated at the appropriate territorial scale to properly undertake the responsibilities assigned to them. However, successful greenbelt management – understood as confining (sub)urban growth and protecting greenspaces – needs an effective allocation and re-allocation of land-use rights against the resistance of municipalities and developers. This redistribution of land-use rights that comes with urban growth containment and greenspace protection, though, requires strong planning authority and thus cannot be undertaken by special purpose bodies. Instead, we argue that new generation greenbelt management requires government organizations with sufficient regulatory powers and resources to effectively implement greenbelt policy goals. To conclude, the Regionalpark RheinMain and the Frankfurt and Offenbach greenbelts are important environmental assets to the Frankfurt Rhine-Main region. However, the Regionalpark RheinMain is now at a crossroads due to increasing regional development pressures. While it is more important than ever to strengthen the Regionalpark’s future protection, it remains uncertain if that is possible given the significant institutional constraints within which it is situated in the Frankfurt Rhine-Main region.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the valuable feedback we received from Jörg Dettmar, Valentin Meilinger, Roger Keil, Michael Collens, Susanne Heeg and Bernd Belina and the anonymous reviewers on earlier versions of this article. The authors would like to thank the numerous interview partners for their support and Maximilian Hellriegel for his research assistance on this project.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 For similar analytical categories, see Röhring and Gailing (Citation2005), Young et al. (Citation2008) and Young (Citation2002).

2 All translations are done by the authors.

References

- Addie, J., & Keil, R. (2015). Real existing regionalism: The region between talk, territory and technology. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 39(2), 407–417. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12179

- Amati, M. (2008). Urban green belts in the twenty-first century. Hampshire: Ashgate.

- Brenner, N. (2003). Metropolitan institutional reform and the rescaling of state space in contemporary Western Europe. European Urban and Regional Studies, 10(4), 297–324. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/09697764030104002

- Cadieux, K., Taylor, L., & Bunce, M. (2013). Landscape ideology in the Greater Golden Horseshoe Greenbelt plan: Negotiating material landscapes and abstract ideals in the city's countryside. Journal of Rural Studies, 32, 307–319. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2013.07.005

- Carter-Whitney, M. (2010). Ontario’s Greenbelt in an international context. Friends of the Greenbelt Foundation. Retrieved from https://www.greenbelt.ca/ontario_s_greenbelt_in_an_international_context2010

- Dettmar, J. (2012). Weiterentwicklung des Regionalparks RheinMain. In J. Monstadt, B. Schönig, K. Zimmermann, & T. Robischon (Eds.), Die diskutierte region: Probleme und Planungsansätze der Metropolregion Rhein-Main (pp. 231–254). Frankfurt am Main: Campus Verlag.

- Diller, C. (2016). The development of metropolitan regions in Germany in light of the restructuring of the German states: Two temporally overlapping discourses. European Planning Studies, 24(12), 2154–2174. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2016.1258040

- Federal Agency for Nature Conservation. (2008). Landscape planning. The basis for sustainable landscape development. Retrieved from https://www.bfn.de/fileadmin/MDB/documents/themen/landschaftsplanung/landscape_planning_basis.pdf

- Freund, B. (2003). The Frankfurt Rhine-Main region. In W. G. Salet, A. Thornley, & A. Kreukels (Eds.), Metropolitan governance and spatial planning: Comparative case studies of European city-regions (pp. 125–144). London: Spon.

- Gailing, L. (2007). Regional parks: Development strategies and intermunicipal cooperation for the urban landscape. German Journal of Urban Studies, 46, 1.

- Galland, D., & Harrison, J. (2020). Conceptualising metropolitan regions: How institutions, policies, spatial Imaginaries and planning are influencing metropolitan development. In K. Zimmermann, D. Galland, & J. Harrison (Eds.), Metropolitan regions, planning and governance (pp. 1–24). Cham: Springer.

- Glass, M. (2018). Navigating the regionalism–public choice divide in regional studies. Regional Studies, 52(8), 1150–1161. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2017.1415430

- Hall, P., & Taylor, R. (1996). Political science and the three new institutionalisms. Political Studies, 44(5), 936–957. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.1996.tb00343.x

- Han, A., & Go, M. (2019). Explaining the national variation of land use: A cross-national analysis of Greenbelt policy in five countries. Land Use Policy, 81, 644–656. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.11.035

- Hohn, U., & Neuer, B. (2006). New urban governance: Institutional change and consequences for urban development. European Planning Studies, 14(3), 291–298. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09654310500420750

- Hoyler, M., Freytag, T., & Mager, C. (2006). Advantageous fragmentation? Reimagining metropolitan governance and spatial planning in Rhine-Main. Built Environment, 32(2), 124–136. doi: https://doi.org/10.2148/benv.32.2.124

- Husung, S., & Lieser, P. (1996). Greenbelt Frankfurt. In R. Keil, D. Bell, & G. Wekerle (Eds.), Local places in the age of the global city (pp. 211–222). Montreal, QC: Black Rose Books.

- Jessop, B. (2000). The dynamics of partnership and governance failure. In G. Stoker (Ed.), The new politics of British local governance (pp. 11–32). Basingstoke: Macmillan.

- Keil, R. (2011). The global city comes home: Internalised globalisation in Frankfurt, Rhine-Main. Urban Studies, 48(12), 2495–2517. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098011411946

- Kortelainen, J. (2010). The European green belt: Generating environmental governance-reshaping border areas. Quaestiones Geographicae, 29(4), 27–40. doi: https://doi.org/10.2478/v10117-010-0029-y

- Krause, R. (2014). Placemaking in the RhineMain Regionalpark (Master’s thesis). Blekinge Institute of Technology, Karlskrona. Retrieved from http://www.diva-portal.se/smash/get/diva2:832027/FULLTEXT01.pdf

- Krug, M. (2016, December 27). Fraport AG stockt Umweltfonds auf fünf Millionen Euro auf. Hessen-Depesche-Wirtschaft. Retrieved from https://www.hessen-depesche.de/wirtschaft/fraport-ag-stockt-umweltfonds-auf-fC3BCnf-millionen-euro-auf.html

- Lucas, J. (2016). Fields of authority: Special purpose governance in Ontario, 1815–2015. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

- Macdonald, S., & Keil, R. (2012). The Ontario Greenbelt: Shifting the scales of the sustainability fix? The Professional Geographer, 64(1), 125–145. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00330124.2011.586874

- Mace, A. (2018). The metropolitan green belt, changing an institution. Progress in Planning, 121, 1–28. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progress.2017.01.001

- March, J., & Olsen, J. (2011). Elaborating the ‘new institutionalism’. In R. Goodin (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Political Science (pp. 159–175). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Monstadt, J., & Meilinger, V. (2020). Governing suburbia through regionalized land-use planning? Experiences from the Greater Frankfurt region. Land Use Policy. Online first. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.104300

- Monstadt, J., Zimmermann, K., Robischon, T., & Schönig, B. (2012). Die diskutierte region. Probleme und Planungsansätze der Metropolregion Rhein-Main. Frankfurt am Main: Campus-Verlag.

- Natural England and the Campaign to Protect Rural England. (2010). Green Belts: a greener future. Retrieved from https://www.cpre.org.uk/resources/housing-and-planning/green-belts/item/1956-green-belts-a-greener-future

- Nelles, J. (2012). Comparative metropolitan policy: Governing beyond local boundaries in the imagined metropolis. London: Routledge.

- Planungsverband Ballungsraum Frankfurt/Rhein Main and Regierungspräsidium Darmstadt. (2005). Frankfurt/Rhein-Main 2020 – the European metropolitan region. Strategic vision for the regional land use plan and for the Regionalplan Sudhessen. Frankfurt: Author.

- Planungsverband Frankfurt Region RheinMain. (2001). Landschaftsplan UVF. Aufbau, Ziele, Umsetzung. Retrieved from https://www.region-frankfurt.de/media/custom/1136_3_1.PDF

- Rautenstrauch, L. (2015). Regionalpark RheinMain – Die Geschichte einer Verführung. Regionalpark RheinMain Ballungsraum GmbH. Frankfurt am Main: Societaets Verlag.

- Regierungspräsidium Darmstadt and Regionalverband. (2010, October 17). Regionalplan Südhessen/Regionaler Flächennutzungsplan, Allgemeiner Textteil of October 17, 2010. Darmstadt: Author.

- Regionalverband=Regional Authority FrankfurtRhineMain. (2018). Regionales Monitoring 2018. Daten und Fakten – Metropolregion FrankfurtRheinMain. Frankfurt: Author.

- Ronneberger, K., & Keil, R. (1993). Riding the tiger of modernization: Red-green municipal reform politics in Frankfurt am Main. Capitalism Nature Socialism, 4(2), 19–50. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/10455759309358542

- Röhring, A., & Gailing, L. (2005). Institutional problems and management aspects of shared cultural landscapes: Conflicts and possible solutions concerning a common good from a social science perspective. Erkner: Leibniz-Institut für Regionalentwicklung und Strukturplanung eV (IRS).

- Schmidt, S. (2009). Land use planning tools and institutional change in Germany: Recent developments in local and regional planning. European Planning Studies, 17(12), 1907–1921. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09654310903322397

- Schmidt, S., Siedentop, S., & Fina, S. (2018). How effective are regions in determining urban spatial patterns? Evidence from Germany. Journal of Urban Affairs, 40(5), 639–656. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2017.1360741

- Siedentop, S., Fina, S., & Krehl, A. (2016). Greenbelts in Germany's regional plans – an effective growth management policy? Landscape and Urban Planning, 145, 71–82. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2015.09.002

- Sieverts, T. (2003). Cities without cities: An interpretation of the zwischenstadt. London: Routledge.

- Sorensen, A. (2015). Taking path dependence seriously: An historical institutionalist research agenda in planning history. Planning Perspectives, 30(1), 17–38. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/02665433.2013.874299

- Stadt Frankfurt am Main. (2015). Prozessdokumentation: Specichen und Strahlen Frankfurt am Main. Frankfurt am Main: Author.

- Stadt Offenbach. (August 4, 2017). 30 Jahre Grünring Offenbach: Wegweisende Entscheidung gegen die Südumgehung. Retrieved from https://www.offenbach.de/leben-in-of/planen-bauen-wohnen/gruene_stadt/regionale_routen/dreissig-jahre-gruenring-offenbach-7.8.17.php

- Stoker, G. (1998). Governance as theory: Five propositions. International Social Science Journal, 50(155), 17–28. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2451.00106

- Storper, M. (2014). Governing the large metropolis. Territory, Politics, Governance, 2(2), 115–134. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2014.919874

- Sturzaker, J., & Mell, I. (2017). Green Belts: Past; present; future? London: Routledge.

- Wei, L. (2017). Multifunctionality of urban green space – an analytical framework and the case study of Greenbelt in Frankfurt am Main, Germany (Doctoral dissertation). Technische Universität Darmstadt, Darmstadt.

- Willi, Y., Pütz, M., & Müller, M. (2018). Towards a versatile and multidimensional framework to analyse regional governance. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 36(5), 775–795. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654418760859

- Young, O. (2002). The institutional dimensions of environmental change: Fit, interplay, and scale. London: MIT Press.

- Young, O., King, L., Schroeder, H., Galaz, V., & Hahn, T. (2008). Institutions and environmental change: Principal findings, applications, and research frontiers. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Zimmerbauer, K., & Paasi, A. (2019). Hard work with soft spaces (and vice versa): problematizing the transforming planning spaces. European Planning Studies, 1–19. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1653827