ABSTRACT

High-growth firms – also called gazelles – have the potential to create jobs and to drive regional development. Yet, there remains a lack of understanding about how to best support these companies in their growth process. Hence, the types of support offered to these firms are often misdirected and fail to provide relevant support to appropriate types of businesses. This paper focuses on one support policy aimed at support gazelles to cope with their growth challenges, namely intermediary actors, who provide matchmaking, advise and networking activities directed to gazelles. More specifically, this paper aims at identifying what challenges are encountered by gazelles and whether the support provided by intermediary actors is matching the need of support. The empirical focus of the paper is on gazelles within the construction industry and situated in the Swedish municipality Norrköping. Findings indicate that challenges relate to recruitment, interactions with the public sector, lack of support and entrepreneurial personalities/skills. These challenges overwhelm the everyday work of entrepreneurs, who struggle to find solutions, despite the support of intermediaries. Implications for high-growth companies, intermediary actors and policymakers are discussed with the aim of finding a better match between high-growth challenges and intermediary support.

1. Introduction

Less privileged regions often struggle to undergo radical change processes due to a lack of representation from new businesses (Morgan and Nauwelaers Citation1999; Svensson, Klofsten, and Etzkowitz Citation2012). One interesting contrasting case is the medium-sized Swedish municipality Norrköping. Norrköping was hit by economic decline in the 1990s, it has recently received attention due to an unexpectedly high number of gazelle companies, especially in the construction (low-tech) industry (Hermelin Citation2018). This may be a sign that the region has started to catch up, since previous studies have shown that gazelles create jobs and drive regional development (Brown, Mawson, and Mason Citation2017; Georgallis and Durand Citation2017; Pitelis Citation2012; Porter Citation1998). These companies have the potential to revitalize geographic areas such as Norrköping and it is therefore important to ensure the continuous growth of these companies while dealing with the challenges of expansion (Lee Citation2014).

Although there is a reasonably high number of start-ups in Sweden, not many of these grow (Acs and Armington Citation2004). In comparison with the US, Europe has fewer growing firms (Bravo-Biosca Citation2010). Over the years, scholars have devoted considerable efforts at finding factors explaining business growth and the growth process of gazelles. (e.g. Brush, Ceru, and Blackburn Citation2009; Demir, Wennberg, and McKelvie Citation2017; Lerner and Haber Citation2001; McKelvie and Wiklund Citation2010; Wiklund, Patzelt, and Shepherd Citation2009). Yet, the fact that high-growth certainly is a sign of success, it does not mean that high-growth firms also face challenges in their daily operations and to achieve their long-term goals. Surprisingly, the challenges that gazelles encounter to keep on growing, remains largely understudied (Autio, Sapienza, and Almeida Citation2000; Cunneen and Meredith Citation2007; Hölzl Citation2014; Kane Citation2010; Markman and Gartner Citation2002). This is problematic because there remains a lack of understanding about how to best support these high-potential companies in their growth process. As a consequence, the types of support offered to these firms are often misdirected and fail to provide relevant support to appropriate types of businesses (Brown, Gregson, and Mason Citation2016; Brown, Mawson, and Mason Citation2017; Shane Citation2009).

Offering support services through private and public intermediaries, that provide advice, matchmaking and network opportunities, is one of the policy instruments largely implemented by policymakers on the regional and national levels (e.g. Bennett Citation2008; Fischer and Reuber Citation2003; Klerkx, Hall, and Leeuwis Citation2009; Laur, Klofsten, and Bienkowska Citation2012; Zhang and Li Citation2010). Theoretically, intermediaries have the potential to provide capabilities that are well needed by entrepreneurs on the path of developing their business (Howells Citation2006; Spithoven and Knockaert Citation2012). Nevertheless, intermediary services seem to lead to various levels of satisfaction among entrepreneurs (Bennett Citation2008) and studies have reported a lack of interest from entrepreneurs in participating in activities or other support activities organized by intermediaries (e.g. Brown, Gregson, and Mason Citation2016).

Against this background, this paper aims at filling this current gap by identifying challenges encountered by gazelles and investigating the match or mismatch between these challenges and the support provided by intermediary actors. More specifically, the paper intends to answer the following research questions: (RQ1) What are the challenges experienced by gazelles which may disrupt their growth? (RQ2) What services are offered by intermediary actors to support gazelles to cope with such challenges?

This study strives to provide an empirical insight into the development process of rapidly growing businesses and to develop policy recommendations aimed at supporting such process. More specifically, it focuses on growth challenges faced by Swedish high-growth businesses within the construction industry. Over the latest years, these firms have been overrepresented among gazelles in Sweden (and particularly in old industrial areas, such as Norrköping) (Daunfeldt and Halvarsson Citation2015; Davidsson and Delmar Citation2006; Svensson, Klofsten, and Etzkowitz Citation2012). Bearing in mind that several regions face similar problems to Norrköping, this study may be used as an illustrative example for solving development problems via the use of supporting mechanisms as intermediaries.

2. Theoretical framework

2.1. Gazelle companies

Gazelle companies have been compared to gazelles in the African savanna, where the health of these animals provides an indication on the health of the whole ecosystem. Birch (Citation1979) referred to high growth companies as ‘gazelles’, contrasting these with mice and elephants, which grow more slowly. Gazelles are the most common type of high-growing business in developed and developing European countries (Allen et al. Citation2007). They are defined by Birch, Haggerty, and Willliams (Citation1995) as businesses that have achieved a minimum of 20% growth in sales each year over initial and base revenue of USD 100,000.

Several attributes must be fulfilled to classify as a gazelle, according to the OECD (Citation2011): 20% employment growth per year within three years and at least ten employees during the start-up year. Any company that has achieved at least 50% sales growth during three consecutive financial years can be a gazelle, regardless of its industry affiliation, size, age and specialization (Autio, Sapienza, and Almeida Citation2000). While some scholars claim that gazelles outperform other companies through intense market entry, high risk-taking and strong growth strategies (Wells and Hungerford Citation2011), many scholars instead argue that only the most ambitious ventures contribute to growth, with the rest of ventures remaining out of the spotlight (Audretsch and Peña-Legazkue Citation2012; Autio, Sapienza, and Almeida Citation2000; Kane Citation2010).

Several types of gazelles are mentioned in the literature: fawns (which achieve profitability, but are not growing), prodigals (which large enough and grow substantially, but are not profitable) and premature infants (which are only growing, without exhibiting other aspects) (Virtanen and Kiuru Citation2013). On this basis, a study by Hölzl and Friesenbichler (Citation2010) states that the growth or decline of a high-growth company is a rare event, as most companies do not change in size. In other words, many gazelle companies can be classified as fawns. Gazelle growth seems to be short-term and slows dramatically after the gazelle peak. Danish gazelle data shows that many companies meet the gazelle criteria for a single year, but fewer than 5% manage to keep growing at a high pace after three years (Børsen Citation2008).

In the last years, gazelles have received much attention in the entrepreneurship and the societal planning literature. The main reason behind this interest is that gazelles generate jobs and contribute to economic wealth in society even in periods of recession (Anyadike-Danes, Hart, and Du Citation2015; Henrekson and Johansson Citation2010; Hoffmann and Junge Citation2006). According to NESTA (Citation2009), high growth companies have created about half of all new jobs in previous periods (in comparison, start-ups create only one in ten jobs (Kane Citation2010)). Moreover, studies have shown that gazelles are drivers for innovation and regional development (e.g. Bos and Stam Citation2014)

2.2. Factors enabling gazelles’ growth

Factors explaining venture growth have been discussed extensively in the entrepreneurship and strategic management literature (e.g. Delmar, Davidsson, and Gartner Citation2003; Geroski, Machin, and Walters Citation1997; Gupta, Guha, and Krishnaswami Citation2013; Penrose Citation2009). In the specific context of small fast-growing companies such as gazelles, authors have developed models highlighting determinants of growth (Demir, Wennberg, and McKelvie Citation2017; Lerner and Haber Citation2001; Moreno and Casillas Citation2008; Teruel and De Wit Citation2017; Wiklund, Patzelt, and Shepherd Citation2009). Overall, the factors that have received extensive attention for their influence on the growth of gazelles are related to the gazelles’ strategy, the environment and the institutional setting, resources and firm characteristics.

Related to strategy, it has been said, for instance, that entrepreneurial orientation reflected in the strategic orientation of the firm and captured through specific entrepreneurial aspects of decision-making styles, management approach, and practices have an impact of the growth of a gazelle (e.g. Demir, Wennberg, and McKelvie Citation2017; Muurlink et al. Citation2012; Wiklund, Patzelt, and Shepherd Citation2009). Likewise, whether the strategy is oriented towards searching for opportunities and growth, whether the growth strategy is based on the development of new products–technologies or new needs–markets (e.g. Brush, Ceru, and Blackburn Citation2009; Moreno and Casillas Citation2008; Teruel and De Wit Citation2017), or whether it is a broad-market strategy or a niche-market strategy (e.g. Brush, Ceru, and Blackburn Citation2009; Senderovitz, Klyver, and Steffens Citation2016) are aspects that are determinant for the success of a gazelle.

Aspects related the environment and the institutional setting surrounding the firm include e.g. location and market. Indeed, the location attractiveness, whether there is a good access to infrastructure and whether the environment is dynamic (or hostile) has a direct impact on gazelles’ growth (Moreno and Casillas Citation2008; Wiklund, Patzelt, and Shepherd Citation2009; Wiklund and Shepherd Citation2005). Which country a gazelle operates in are also determinant, as it affects, e.g. the level of education of its staff, the entrepreneurs’ status and legitimacy, as well as the economic and non-economic conditions encouraging or hampering business growth (e.g. Lerner and Haber Citation2001; Teruel and De Wit Citation2017)

Finally, many studies, both in the entrepreneurship and the strategy literatures, have stressed the importance for growth of resources, such as dynamic capabilities, human resources, financial resources and networks (e.g. Barbero, Casillas, and Feldman Citation2011; Brush, Ceru, and Blackburn Citation2009; Demir, Wennberg, and McKelvie Citation2017; Moreno and Casillas Citation2008; Wiklund, Patzelt, and Shepherd Citation2009) as well as firm characteristics, e.g. the education, experience, and skills and personality attributes of the entrepreneurs leading the business (e.g. Demir, Wennberg, and McKelvie Citation2017; Lerner and Haber Citation2001), firm activities (e.g. Keen and Etemad Citation2012; Lerner and Haber Citation2001), and firm size and age (e.g.Keen and Etemad Citation2012; Stam Citation2010). While these factors can be interpreted as both inducing or hampering, only few studies focus on the challenges of high-growth firms and how these challenges impact their growth. Among the few exceptions, Mason and Brown (Citation2013) and Lee (Citation2014) can be mentioned. In line with the growth factors listed above, Mason and Brown (Citation2013) found that gazelles faced challenges related to resources (more specifically, difficulties recruiting and absorbing new staff), to the environment (i.e. competition, regulations associated with planning permission) and finance. Similarly, Lee (Citation2014) found that challenges related to lack of capabilities such as human resources, managerial skills and shortage of skills in general, as well as challenges related to finances, cash flow and to availability and cost of premises are prevalent among gazelles.

Another interesting gap, in the existing literature, is that while there is a major focus on determinants hampering business growth in general, less attention is given to the specificities of gazelles’ industry context. Determinants are rather inward-oriented and are mainly related to firms’ internal attributes. Looking specifically at the construction industry, which this paper focuses on, a few studies have stressed challenges related to a lack of access to manpower (especially blue-colour builders) and skills (e.g. Fellini, Ferro, and Fullin Citation2007; MacKenzie et al. Citation2010), as well as limitations related to conservativeness and reluctance to change (e.g. Pries and Janszen Citation1995; Shehu and Akintoye Citation2010). The construction industry is also characterized by high competition between firms and uncertainty (Abd-Hamid, Azizan, and Sorooshian Citation2015), which surely influences the growth opportunities for young high-growth firms. Overall, despite these few studies, there is a lack of empirical studies exploring the current challenges of growth faced by construction gazelles.

2.3. Policy instruments for the support of gazelles

Interestingly, apart for a few exceptions (e.g. Lerner and Haber Citation2001; Teruel and De Wit Citation2017), the role of policies in gazelles’ growth has not received much attention in the previous literature about factors stimulating or hampering the growth of gazelles. Yet, we know that many studies have treated the topic of entrepreneurship policies in combination with high-growth companies (e.g. Brown, Mason, and Mawson Citation2014; Brown, Mawson, and Mason Citation2017; Koski and Pajarinen Citation2013; Mason and Brown Citation2013).

Many authors see high potential in gazelles (e.g. in comparison with start-ups) and base their recommendations to policymakers on the need to support these companies (e.g. Mason and Brown Citation2013; Shane Citation2009). Among the policy instruments used to support gazelles, the following ones are common:

Tax credits (e.g. Shane Citation2009)

Market entry schemes (e.g. grants intended to support the process of entering market overseas, university spin-out programs) (e.g. Kanda, Mejiá-Dugand, and Hjelm Citation2015; Mason and Brown Citation2013)

Provision of venture capital, e.g. aimed at encouraging early stage technology development and R&D activities (e.g. Lerner Citation2010; OECD Citation2011)

Business advising (e.g. business mentorship, advise related to marketing, financing, international market entry) and intermediation (e.g. matchmaking gazelles with actors and resources, fostering the creation of networks, platform development) services (Fischer and Reuber Citation2003; Mason and Brown Citation2013; Smallbone, Baldock, and Burgess Citation2002; Zhang and Li Citation2010).

The last policy instrument of the list above, i.e. business advising and intermediation services, has received a lot of attention in the last years. In particular, the importance of advisors and intermediaries has been noted for the support of entrepreneurs lacking networks and capabilities (e.g. Bennett Citation2008; Cannavacciuolo, Capaldo, and Rippa Citation2015; Fischer and Reuber Citation2003; Klerkx and Leeuwis Citation2009; Laur, Klofsten, and Bienkowska Citation2012; Zhang and Li Citation2010). Business advisors provide with inputs, such as (e.g. technological, business, financial) advise, (e.g. project, financial) planning, mentoring, education (e.g. Bennett Citation2008). Intermediaries provide support by creating missing links, that is to say by connecting entrepreneurs with other actors (e.g. venture capitalists, human resources), by creating platforms and networks where entrepreneurs can interact and mentor each other, or by acting as a ‘one stop shop’ for entrepreneurs, i.e. coordinating a number of actors and support organizations (Bennett Citation2008; Clark Citation2014; Fischer and Reuber Citation2003; Laur, Klofsten, and Bienkowska Citation2012; Moss Citation2009; Spithoven and Knockaert Citation2012). Advisors and intermediaries can be private or public (e.g. Bennett Citation2008; Fischer and Reuber Citation2003). They can support high-growth firms in the high-tech sector as well as in the low-tech sector (e.g. Clark Citation2014; Spithoven and Knockaert Citation2012).

From the perspective of entrepreneurs and gazelle managers, relational aspects of support are considered are determinant for sustainable growth (Mason and Brown Citation2013). Likewise, policy-makers seem to consider advise provision and brokering activities as crucial for the support of gazelles (Fischer and Reuber Citation2003). Nevertheless, advise and intermediation services still seem to lead to various levels of satisfaction among entrepreneurs and sometimes limited impacts at the local or national level (Bennett Citation2008; Cannavacciuolo, Capaldo, and Rippa Citation2015). Studies have reported a lack of interest from entrepreneurs in participating in networking activities or other support activities organized by public organizations (e.g. Brown, Gregson, and Mason Citation2016). It has also been underlined that intermediaries sometimes lack the competences needed to provide appropriate support (Cannavacciuolo, Capaldo, and Rippa Citation2015).

In general, among the studies focusing on the impact of policies on sustainable growth of start-up companies, many underline that the support provided to these companies is often ill-adapted (e.g. Brown and Mawson Citation2016; Brown, Mawson, and Mason Citation2017; Lerner Citation2010; Shane Citation2009; Stam Citation2015). For instance, the focus on R&D support over-emphasises the importance of technology sectors as a source of gazelles and underestimates the opportunities for rapid entrepreneurial growth in other sectors of the economy (Autio, Kovalainen, and Kronlund Citation2007). Another challenge is that gazelles’ challenges are very diverse; policy interventions may at the same time be good for some companies but ineffective or contra-productive for others (Nightingale and Coad Citation2014).

There seems to be a mismatch between the needs of gazelles, i.e. the challenges that they are faced with, and the supporting instruments. In this paper, we will hence identify the challenges of gazelles in the specific context of the construction industry in a less privilege Swedish region, and will investigate whether there is a match or mismatch between these challenges and the support provided by intermediary actors.

3. Methodology

3.1. The study and its empirical focus

In order to answer the research questions of this study, qualitative research approach was applied using multiple case studies of gazelle companies and intermediaries operating within Norrköping municipality.

Overall, empirical focus and chosen methods strive towards delivering a story about Norrköping municipality gazelle firms and its growth as well as attending the most important changes in this process. The study focus on Norrköping municipality can be motivated in several ways. To start with, Norrköping municipality is an example showing contrasting features – from being a thriving industrial area to becoming lagged behind old industrial or less privileged areas with regards to e.g. unemployment rates, jobs and education level (Fredin Citation2016; Svensson, Klofsten, and Etzkowitz Citation2012). As a matter of fact, it is particularly interesting that Norrköping’s strong industrial culture and the presence of former manufacturing giants have been highlighted as a negative influence on a number of start-ups (cf. Morgan and Nauwelaers Citation1999; Svensson, Klofsten, and Etzkowitz Citation2012). Additionally, the municipality works intensively with industrial growth and attraction of businesses. Supporting this, recent empirical study on Norrköping’s economic development shows that the town has many gazelle companies, especially in the construction (low-tech) industry (Hermelin Citation2018). It could be seen as a new growth wave after a stagnation period, where small fast-growing businesses play an important role. Such fluctuation of local development from peaks to downs and opposite wakes an interest to study this particular case. Therefore, it is important to identify what causes such dramatic changes and what can be done to sustain the peak development phase.

The construction industry is based locally in Sweden. Governmental subsidies, regulations and culture have protected Swedish construction industry from global competition. The financial crisis in the real estate sector and decrease of governmental support in the 1990s reduced the demand in construction projects. Instead starting from 2000 till now, due e.g. to the creation of governmental housing loans, low loan interest rates and subsidies allocated to new residential buildings, the demand of new flats in apartment blocks and single houses started to increase, which stimulated the demand in entrepreneurs executing such construction projects (Kalbro, Lind, and Lundström Citation2009).

In Sweden, the building industry is dominated by young small firms with less than 50 employees (99% of all firms). Generally, these are one-man companies operating in a certain field of specialized skills created due to the growing demand on construction projects. Approximately 75% and more of the product’s value is built with help from local suppliers and subcontractors – small construction firms – in construction projects (Dubois and Gadde Citation2000). These construction firms can be the main supplier in some development projects or be positioned as first or even second tier supplier in other projects (London and Kenley Citation2000). Overall productivity in the construction sector is considered to be low (Vrijhoef and Koskela Citation2000). Finally, in the industry, there is a rather high customer involvement, particularly in the project development phases (Briscoe et al. Citation2004).

3.2. Data collection

In this study, we have used different types of empirical sources to describe the development and change within Norrköping gazelles. We have used yearly gazelle lists as a secondary data source and conducted interviews with gazelles and intermediary actors.

Secondary sources consisted of extracts from the business newspaper Dagens Industri, which annually publishes a list of gazelle companies. These were used to comprehensively illustrate the growth potential within the municipality as well as the industry which gazelles belong to. This step served as the main tool to select companies and interview respondents in the following step of the data collection.

The interviews with gazelle firms and intermediaries were aimed at exploring the variety and complexity of challenges met by gazelle companies as well as support action provided. We interviewed two groups of respondents: 2016 gazelle companies in Norrköping and their supporting intermediaries. These interviews took place between May 2017 and February 2019, and they focused on the challenges encountered by companies while growing, as well as intermediary services, manner of their delivery and match with entrepreneurial expectations.

Twenty-seven organizations were initially selected. Seventeen gazelle companies were selected because they were listed as gazelles in 2016. Among these, two lacked contact information, either because the companies had closed down or had been taken over. Four gazelle firms decided not to participate in the study, e.g. because of a lack of time or interest as well as mainly focused their work within transport industry. For the 11 gazelles included in this study (see Table A1 in appendix), interviews were conducted with the managers or founders/managers of the companies. Managers were the persons that managed the daily operations at the time of the interviews, while founders/managers were the persons that both started the business and managed the daily operations at the time of our interviews. One important criterion for the selection was that the respondent had a central role in firm’s management and had been at the position for at least a year. Only a person taking leading role could provide the information about internal firm information together with data on interactions with supporting agencies related to overall growth challenges and effectiveness of supporting actions over time. Another important selection criterion was that these gazelles had earlier turned to intermediary organizations for assistance related to different matters as for example recruitment and mark exploitation. All gazelles included in the study had been in contact with an intermediary at least 2–3 times prior to the interview. As Table A1 (in the appendix) illustrates, the gazelle firms included in this study are of different sizes, age and turnover. We interviewed one respondent per gazelle firm.

Ten intermediary actors were initially selected based on three selection criteria. First, they can be defined as intermediaries according to the widely accepted intermediary definition by Howells (Citation2006, 720):

An organization or body that acts an agent or broker in any aspect of the innovation process between two or more parties. Such intermediary activities include: helping to provide information about potential collaborators; brokering a transaction between two or more parties; acting as a mediator, or go-between, bodies or organizations that are already collaborating; and helping find advice, funding and support for the innovation outcomes of such collaborations.

Three out of ten intermediaries primarily included in the study were gazelle firms themselves, meaning that their growth on latest years were more than doubled (Birch et al., Citation1995). Additional intermediaries were selected because they had been suggested during explorative interviews with municipal employees and construction entrepreneurs. Among the ten intermediaries initially selected, nine participated in the study. Interviews were mainly conducted, as in the previous respondent group, with manager/owner/founders occupying a leading strategic role for the intermediary for at least a year. This secured the accuracy of the information as well as allowed in-depth investigation of intermediary work in relation to entrepreneurial challenges. As Table A2 illustrates, the intermediaries included in this study originate from both public and private sector and they support entrepreneurs by providing various activities for instance networking, matchmaking and coordinating services.

In total, 20 interviewees participated in the study. Each interview took approximately 40–70 min and was semi-structured in nature. Most of interviews were carried out in person, while some respondents were contacted by telephone or email (only three firms). The interview guide was designed as part of a larger explorative study and contained 13 topic-oriented open questions, relating in depth to subjects such as growth patterns, recruitment, contracts, internal and external relationships, growth challenges and intermediary services. For the current study, answers to the questions related to growth challenges and intermediary services were analysed specifically. The responses touched upon both the respondents’ own organizations and more general reflections on developments within areas of interest. The interview data was manly recorded and stored in the form of working notes, which were transcribed directly after each interview.

3.3. Data analysis

The data in this study analysed using a cross-case approach (Khan and VanWynsberghe Citation2008), which aims to underline similarities and differences in the activities and processes occurring between the stakeholders, i.e. among entrepreneurs, among intermediaries, and between entrepreneurs and intermediaries. Such approach suits to our study purpose for the reason that it allows to extract factors that may have contributed to the certain outcome which could particularly be illustrated within the match and mismatch of services and entrepreneurial challenges (Ragins Citation1997). Moreover, cross-case analysis allows articulating hypothesis from a single case, which in this study where generated after each of the interviews, and later enriched via cross-case comparison. Some of the cornerstones used for the comparisons were development phase, variation of services and demands, drivers in search for assistance as well as interaction potential. It should be noted that these cornerstones and themes of analysis were not decided prior to the data collection based, for instance, on the previous literature. Instead these cornerstones and themes emerged from the data, according to the explorative approach taken in the study.

In detail, the data analysis comprises three stages: underlying singles case facts, cross-case facts and comparison of facts. Firstly, two researchers have individually highlighted some main aspects related challenges and mismatches in supporting actions of each respondent and jointly discussed the results whereby enriching the list of facts. The purpose of such procedure was to extract as many important facts valuable for the purpose of this work as possible with a setting to focus on both implicit and explicit reveal. Therefore, joint discussion carried also an import quality-securing function (Yin Citation2003). Secondly, the confirmed facts from single cases were summarized and synthesized schematically jointly by both researchers. This allowed visualization of repetitive facts and their correspondence with different respondents’ explanations. This step shed the light on some uncommon facts, which were only mentioned by one or two of the respondents. These uncommon facts were discussed again and classified either under existing repetitive groups of facts, in case if they had similarities or under their own group, if they illustrated something unusual as for instance company specific, project development phase or driven by clients demands. Lastly, the cross-case comparison was performed solely, where in the explanations for each repetitive and uncommon facts were suited. This way the researcher was able to notice incompatibilities between challenges and supportive actions and find potential reasons for such mismatch.

4. Empirical findings

4.1. The Norrköping municipality – the study context

In 1850, Norrköping was a thriving manufacturing town with flourishing textile and paper industries. It also became a distribution hub with an established port. Between the 1950s and the 1990s, the town’s textile industry shut down due to tough competition, a drop in demand and the relocation of production to lower cost countries. Later on, two major companies, the telecommunication company Ericsson AB and the electronic company Philips ended their production in the city. In the 1960s, 73% of Sweden’s blue-collar workers lived and worked in Norrköping (Almroth and Kolsgård Citation1981).

Despite having several assets such as an international airport, highway and rail links, an active university and a river running through the city centre, Norrköping still struggles to find new ways to develop and avoid stagnation. From once being the fourth largest city in Sweden, it is now the tenth largest city with a population of 100,000 people. Until recently, instead of prioritizing entrepreneurship and the growth of small companies, Norrköping municipality and the local trade unions have had as their main strategy to try to attract other large manufacturing companies as a way to reduce unemployment.

Following a national strategy to re-dynamize the region, as a result of the expansion and the higher education reform of 1994, Linköping University (created in the neighbour city of Linköping in 1975) opened a new campus in Norrköping in 1997. This created new dynamics associated with a flow of students and with many new jobs. This could be seen as a way out of the region’s locked-in thinking (Fredin Citation2016). Active municipal and university roles and government support led to incubators, a science park and transfer centres being established here. This is a good mix for triple helix collaborations, giving Norrköping a focus on high technology and visualization. Later, local inhabitants started to launch small businesses in fields such as IT and fitness. In addition, the municipality focused on other central aspects of development such as attractiveness in terms of cultural value, education, child-friendliness and a green town. This has relied mainly on individual efforts, due to a lack of collaboration between the various actors involved (Svensson, Klofsten, and Etzkowitz Citation2012). However, the municipality has started to put entrepreneurship and supporting the creation of business on its primary agenda.

From a labour perspective, Norrköping is a former industrial town with many workers who were previously employed by industrial plants (Almroth and Kolsgård Citation1981; Qvarsell, Cederborg, and Linnér Citation2005). They have fairly low levels of education and their incomes are below the national average. Most of these former workers did not recover from the employment crisis, and still are long-term unemployed and far from the labour market. Together with newly arrived immigrants, they represent a challenge for the municipality which also faces other economic challenges in terms of delivering public services (Fredin Citation2016; Järvstråt Citation2011; Wallsten et al. Citation2013). Students who graduate from Linköping University often choose to move to other more developed cities in Sweden (Hermelin Citation2018). This is despite the fact that the local focus on entrepreneurship and business development appears to be achieving some positive results.

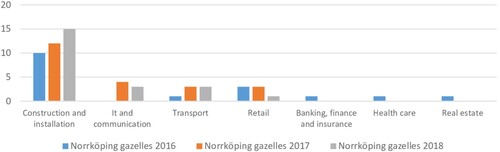

An analysis of gazelles in Norrköping from 2016 to 2018 shows a prevalence of fast growth among construction companies, which represent two-thirds of all high-growth firms in the municipality (see ). There also is a number of high-growing firms within retail industry, but they proportion represent a small share (see ).

4.2. Matches and mismatches between gazelles’ growth challenges and intermediaries’ support

4.2.1. Network and collaboration challenges

The interviews conducted with gazelle companies indicate that gazelles have good collaborations with large firms in the construction industry (Interviews 1, 2, 4-6, 10, 11). It should however be noted that in these collaborations, gazelles most often act as sub-contractors of the larger firms. Such collaboration is also quite rare, i.e. a few times per year (Interview 10). The main motivation to act as sub-contractors is to build a reputation and to get a chance to become more visible than their competitors. Interviewees underlined that, although it is not a primary motivation, the partnerships with larger firms often lead to new projects (Interview 1, 2, 4-6). Yet, finding new projects is not a priority, especially because the demand from new clients is high and that gazelles are having issues to actually deliver the ongoing projects. A major number of these clients originate from the public sector organizations. Since these organizations actively contribute to building gazelles’ reputations (i.e. by spreading their experiences of contracting them for projects to new potential clients), they are considered by gazelles as key pillars of their network (Interview 1, 2, 4-6).

Surprisingly, collaborations are scarce when it comes to other construction actors with similar size and profile. Several of the interviewees mentioned that they avoid contacts and collaboration with other small firms within their industry (Interviews 1, 2, 4-6). Their counterparts are considered as threatening competitors, not only with regard to future projects, but also when it comes to recruiting qualified staff, which are scarce resources (Interview 3, 7, 9). Some interviewees mentioned cases of – what they considered as – unethical competitors’ behaviours such as poaching (i.e. employing from competitors) as well as deliberate lowering of costs in project offers.

This illustrates the fact that gazelles seem to have limited professional networks (Interviews 4-6, 10, 11). Such lack constitutes a real challenge for gazelles, particularly when professional networks are necessary, e.g. for projects taking place outside of the municipal boundaries and where it is essential to be able to rely on collaborators and suppliers during project execution and delivery (Interviews 3, 9). To cope with the challenge of a lack of professional network, gazelles instead turn to their private networks, e.g. close friends and family. Several interviewees for instance mentioned that they managed to access lacking resources, such as human resource, information or skills, that way (Interviews, 4-6, 10,11).

4.2.2. Intermediary support for networks and collaborations

Among the intermediaries supporting gazelles with challenges related to networks and collaborations, employer and trade associations, as well as intermediaries at the municipal administration (e.g. geographic planners) are the most active ones (Interviews 12-20).

Associations, as well as, to a lesser degree, other intermediaries from abovementioned, provide support by organizing networking activities and events, as well as by actively linking gazelles with useful contacts. These activities are, however, not very valued by gazelles, who express frustration with the fact that it does not give the intended results (Interviews 1, 2, 4-6, 10). The frustration is due to what is perceived by gazelles as too many organized networking events, narrow topics of discussion during the events, and overlap of events by different intermediary actors. This leads gazelles to question the real results of such support activities and, as a consequence, they do not prioritize participating in network activities.

Intermediaries at the municipal administration level support gazelles by informing them about upcoming projects and by facilitating access to lacking resources such as office space, human resources and suppliers (Interviews 16-20). For instance, geographical planners at the municipality inform construction entrepreneurs about land available for construction. They also let them know about houses that are vacant or for sale, which are considered as valuable in term of office spaces, especially since gazelles (due to their quick growth) often need larger office spaces. Surprisingly, several interviewees also mentioned that geographical planners at the municipal organization had put them in contact with other construction entrepreneurs in order, for example, to discuss the possibility to share one larger piece of land or a building (Interviews 3,16,18).

4.2.3. Institutional challenges

Gazelles have faced with challenges in the contact with public organizations. To start with, interviewees expressed that they struggle with the high bureaucracy, particularly at the municipal level. More specifically, the long and complex process for construction permits (Interviews 4-6, 11) as well as the process to obtain media installation licences (Interviews 1, 2) seem to be very challenging.

Additionally, the delays in decision-making by the public administrations, such as land planners, land exploitation agency and employment agencies, has a direct impact on project deliveries. For instance, some building permits can take more than two years to obtain, which is hardly bearable considering that the average project execution time for gazelle firms is about six months. Likewise, while according to the rules, it should take two weeks to obtain support from the employment agency for an unemployed person, in practice, it can take up to one month and the person cannot start working before the decision is ready. These delays cause frustration among gazelles. For instance, some interviewees explain that they expect results from authorities immediately regarding their applications or requests – they believe that there is no room for discussion, and it is simply a matter of doing things (Interviews 1, 2, 4).

Interviewees also mentioned challenges related to the lack of flexibility in employment regulations (Interviews 16-19). In particular, complex controlling procedures and demanding requirements for employment of prentices are considered as challenging for entrepreneurs. Prentices are seen as an engaged and handy workforce in the industry, but it seems to be very challenging to handle more that one or two prentices at the time. Indeed, the work of prentices is strictly regulated, e.g. they can only work limited number of hours and carry out task-focused work mirroring their educational speciality. Such requirements require efforts from leaders/entrepreneurs in finding appropriate tasks and limiting working duration. Similarly, while competence pools are necessary to get access to staff, when other options are not available, these pools also have strict rules related to procurements and employment, which several interviewees mentioned as challenging (Interviews 16,17,19). For instance, one entrepreneur mentioned that he employed one inexperienced installer from the resources pool, whom he still had to pay a wage equivalent to the one paid to a specialist that had been working for 10 years within the company (Interview 7).

Finally, some interviewees mentioned some gaps in the knowledge infrastructure in the construction industry (Interviews 1-4). According to them, some of the knowledge included in educational programs for construction technicians are obsolete and key skills are lacking on the employment market. The professional schools, from their words, are still running out-of-date educational programs for carpenters and electricians, which do not deliver specialists being able to work with new technologies and materials.

4.2.4. Intermediary support for institutional challenges

The most active intermediaries when it comes to the support for coping with institutional challenges are the recruitment companies (Interviews 3, 8, 11). They help in handling the administrative burden for gazelles when it comes to the recruitment process. For instance, one interviewee explained that the recruitment company which provides manpower to the company always provides ready permissions from the employment agency (Interview 3). These intermediaries also manage to use their personal contacts with public organization employees to speed up the administrative procedures. Such support has a direct positive impact on the way gazelles’ leaders use their time and it provides well-needed breathing-space.

Gazelles expressed frustration over the weak support from the public sector intermediaries (Interviews 1-8, 13,14). Interviewees clearly see the bureaucracy and administrative burden at the municipal level as an obstacle for company growth and development.

One type of support that gazelles receive from the public sector intermediaries, as for example employment agency and association, is aimed at getting access and managing prentices (Interviews 2, 4, 10, 20). Although they see it as minor, gazelle entrepreneurs still appreciate such contribution in handling of human resource shortages.

4.2.5. Challenges related to competence development

Gazelles develop their competences in different ways. First, competence development takes place among employees, e.g. through mentorship or experience sharing (Interviews 4, 5, 10). Learning-by-doing and learning from peers seem to take place continuously through every-day hands-on work in projects. Usually, in projects, there are always two persons assigned to different tasks – a junior one and a senior -one (Interview 4). This creates a natural learning context to learn from each other, to learn from mistakes and learn things which deviate from the standard practices. Such exchanges often take place even during social events and celebrations and are considered as productive.

Second, training sessions, courses or seminars are also organized at the organization level, in larger groups (Interviews 5, 10). Such events are sometimes led by the managers of the gazelles, or by other key persons in their professional networks, e.g. suppliers, clients and possibly large construction companies (Interviews 5, 10).

Third, competence development can also be at the individual level. It happens for instance that specific employees participate in trainings or courses organized outside of the gazelle firms (Interviews 4, 9, 10). Such training is most often based on the initiative of employees that want to develop. Managers for instance expect the employee to come with a plan about what and where he or she wants to be trained. It should be noted that such initiatives depend on resource availability – especially when it comes to time and staff availability; in case of time pressure or resource scarcity, project delivery is always prioritized in front of competence development (Interviews 9, 11).

Based on the interviews, it appears that the main challenge with regard to competence development is that it is carried out reactively, rather than proactively. The lack of competence is usually discovered when the competence is needed the most, i.e. during project execution (Interviews 1, 7). Following the same logic, future projects are not considered as a basis for competence development, even when it is clear that there is no experience in specific techniques and practices (Interviews 1, 5, 7).

4.2.6. Intermediary support for competence development

Our interviews show that the intermediaries that are the most active in the support for competence development are consultancy firms, professional schools and employer associations. These intermediaries either deliver training program themselves or they find an appropriate actor to do so. Interestingly, interviewees explained that the main criterion considered by gazelles to select training program is the time aspect (i.e. short courses or short delays for the delivery of the program), before aspects such as price is not considered as determinant (Interviews 1, 2, 4-10).

Professional schools are invited to provide short-termed course packages on certain topics related to construction, which despite not always been up to date, still provide opportunities for learning (Interviews 4-6). Consultants are considered to be more up-to-date and are hired to focus either on theoretical or practical specific of the work (Interviews 4-6, 7-11). Employer associations also offer seminars and shorter courses opened to gazelles, where management skills, such as entrepreneurship, marketing or recruitment strategies, are in focus. Nevertheless, it is noticeable that gazelles’ participation is very low in such courses (Interview 20).

4.2.7. Challenges related to human resource management

Among the challenges mentioned by gazelles, challenges related to human resource management were prevalent (Interviews 1-6, 8-11). The interviewed gazelles experience challenges regarding recruiting and retaining personnel, particularly among professions such as technicians, installation specialists and experienced engineers. To illustrate the lack of manpower, several interviewees (Interviews 1, 2, 4, 9) mentioned that ongoing projects would require at least twice as many workers as are currently employed. This explains why construction gazelles are constantly in search for workers. Retention of staff is also problematic with personnel leaving to other industries or to competitors (Interviews 1-5, 9-11).

These challenges have a direct impact on the planning and execution of projects. As a consequence, employees are often overloaded and gazelles have to settle with underqualified staff. They employ for instance prentices who lack experience, immigrant workers with uncertified education and experience, as well as people that are part of rehabilitation programmes (i.e. recovering alcoholics) (Interviews 5, 6, 9). To cope with these challenges, some interviewees have started to use more creative approaches for recruitment such as assistance in finding place to live, children care and school places, as important means to motivate new employees to relocate. In order to retain their current employees, gazelles offer, as a norm, permanent contracts and rather high salaries (Interviews 1-6, 8-11).

Another challenge mentioned by some interviewees in relation to human resource management is the lack of diversity in their personnel. They would like to recruit more women and workers with different nationalities (Interviews 1, 2, 4, 6, 11). Some companies were proud to state that they have recently employed two women in their construction projects (Interview 4). Some gazelles have developed close collaboration with supporting firms from Baltic region, which provide qualified constructors upon a short notice. They believe that a diversity-rich personnel profile might improve working environment and reduce conflicts among the employees (Interviews 8, 18, 20).

Finally, gazelles are often keen on recruiting prentices, but they complain about the strict requirements in regard to the working conditions and tasks (Interviews 1, 4, 11). Prentices are for instance not allowed to work full time but rather divide time for studies and work. They are also required, by their educational programs, to focus on specific tasks that are not always available in gazelle projects (Interview 20).

4.2.8. Intermediary support for human resource management

The intermediaries that provide the most support to cope with challenges associated with human resource management are the recruitment companies (Interviews 3, 6, 9). They link job seekers with gazelles, as well as lower the administrative burden related to recruitment. This support, although perceived as useful by gazelles, is however not flowless. Gazelles do not always find that the human resources provided by recruitment companies actually match their needs and they find the intermediation services very expensive (Interviews 1, 2, 4, 8, 10). Because of that, several interviewees mentioned that the support is only used in case of emergency, i.e. when no other options are available. Public Employment Agency, despite a very bureaucratic setting, seems to be supportive by providing access to immigrant or non-professionalized working force.

Apart from recruitment agencies, other intermediaries such as employer associations and municipal organization provide some support to gazelles in handling human resources shortages. Their support is often not a part of their primary mission, but the result is often valued by the gazelle entrepreneurs. Employer associations, for instance, establish relationships with European intermediaries in order to gain wider access to the workforce within the industry. Moreover, they have developed relationships with entrepreneurs operating recruitment agencies in the Baltic countries, giving access to a new workforce with good skills.

5. Discussion

5.1. Gazelle challenges

The findings indicate that gazelle faced a variety of challenges mainly related to (lack of) network and collaboration, complex and long administrative procedures and lack of resources (in particular, time and qualified workforce) (see ).

Table 1. Overview of gazelle challenges and intermediary support.

Among these challenges, the lack of network and collaboration, as well as the lack of resources are challenges that have been identified in previous studies as prevalent for high-growth enterprises (e.g. Demir, Wennberg, and McKelvie Citation2017; Keen and Etemad Citation2012; Lerner and Haber Citation2001; Wiklund, Patzelt, and Shepherd Citation2009). The lack of network and of human resources can for instance easily been explained by the fact that gazelles lack the legitimacy, visibility and stability that larger incumbent firms can have. For instance, when it comes to recruiting and retaining staff, gazelles may not, from the perspective of employees, be able to offer the same stability or advantages that a large establish firm may have. Related to collaborations, it clearly showed in our interview data, that while firms of the same size and profile compete aggressively with each other, larger established firms do not consider gazelles as a strength and instead use them as subcontractors.

As previous studies have shown (e.g. Demir, Wennberg, and McKelvie Citation2017; Wiklund, Patzelt, and Shepherd Citation2009), our results also show that gazelles struggle to manage the operations strategically. For instance, it appears particularly difficult for fast-growing companies to strategically select projects. Our interviews show that gazelles are overloaded with projects for which they sometimes lack competences, adding to the time pressure and worthening the working conditions for employees. Under such time pressure, time-consuming activities, e.g. competence development and networking, are not prioritized, despite their strategic relevance.

In line with what has been argued in the previous literature (e.g. Moreno and Casillas Citation2008; Teruel and De Wit Citation2017; Wiklund, Patzelt, and Shepherd Citation2009; Wiklund and Shepherd Citation2005), some of the challenges that were prevalent in our interviews are specific to the environment and environmental setting surrounding the gazelles, i.e. the construction industry, its dynamism and hostility and its governmental obstacles (e.g. delays in permit decisions, complex administrative processes). It may be argued that such challenges are not unique to gazelles but are instead shared by all companies within the industry. However, the fact that gazelles, due to their intensive growth process, characteristics (e.g. young age, size) and limited resources, is reinforcing the impact of these challenges.

As a matter of fact, our results also uncover that these challenges associated with high growth are in fact causing gazelles not to be able to benefit from the support provided by intermediaries. Indeed, as will be further discussed in the following section, although the support provided by intermediaries is well-needed and often relevant, due to a lack of resources and long-term strategy orientation, gazelles are not able to prioritize time-consuming activities, e.g. competence development and networking, provided by intermediaries.

5.2. Mismatch between the short-term orientation of intermediaries and the time-consuming support from intermediaries

As our findings indicate, an ecology of intermediaries is providing support to gazelles. Among them, there are associations, individuals (e.g. at the municipal administrative level), private companies (e.g. consultancy or recruitment firms) and public organizations (e.g. unemployment agency). It is interesting to note that the majority of intermediaries mentioned by the interviewed gazelles indeed do not have a vision in supporting gazelles (notable exceptions include the regional economic development agency and the new business development office). Instead, they support them on the side of other non-gazelle actors. Another interesting note is that gazelles mentioned support from actors that do not have a formal intermediating or supporting role, e.g. land planners at the municipal administration. Instead, they combine intermediation activities with non-intermediation activities. This stresses what has previously been suggested in the intermediary literature, namely that intermediation is linked to activities (i.e. what is done?), rather than formal positions or missions (i.e. who does it?) (Bergek Citation2020; Poncet, Kuper, and Chiche Citation2010).

From our interviews with both intermediaries and gazelles, it can be said that there is a real effort from intermediary actors to provide support targeted at the areas where gazelles have challenges (see ). In particular, offering support in network and competence development was prevalent in the interviews. Intermediaries also provide some support to cope with institutional challenges and access to (human) resources, e.g. help facilitating the administrative processes or facilitating the process to access prentices and manpower. Despite these attempts of matching the intermediary support to the gazelles’ challenges, our study confirms that gazelles are rather unsatisfied with the services provided by intermediaries. There is a limited interest in the activities/support offered, and they complain about a lack of support that is not being provided. This type of limited interest and low satisfaction level has also been noticed in previous studies (e.g. Bennett Citation2008; Brown, Gregson, and Mason Citation2016; Cannavacciuolo, Capaldo, and Rippa Citation2015).

The problem is that challenges related to institutional rules, delays, administrative processes are not always solvable. In several of the interviewees with gazelles, the managers actually complained or questioned the rules and processes themselves, rather than their lack of skills in dealing with the process. Likewise, challenges related to access to human resources that are hard to solve without investing time or without a long-term perceptive. It is difficult – and maybe even counterproductive – for intermediaries to offer quick-fix solutions. Instead, since time seems to be the missing key for gazelles to be able to think more strategically and to lower the frustration linked to administrative processes, one area of intermediary development may be to support gazelles by acting on their behalf in some tasks that do not necessarily need to be handled by gazelles’ managers. In some interviews, gazelles were indeed satisfied with the opportunity to delegate some administrative processes to intermediaries. Externalizing tasks is not a new type of intermediation activity; tasks such as accounting, advertising, contract formulating, etc. are often delegated to consultancy firm (e.g. Bessant and Rush Citation1995; Mignon Citation2017).

Our results show that there seems to be a lack of understanding of gazelles’ specific challenges among gazelles’ stakeholders. Municipalities, national and regional agencies, recruitment firms and training/education institutions are either not aware, or ill-adapted to handle gazelles and their needs. One solution may be to create functions in these instances to specifically deal with gazelles, for instance, to explain the background between the rules and processes, gather inputs related to better processes and programmes, etc. This perspective contrasts with one argument expressed in the previous literature (e.g. Nightingale and Coad Citation2014), which states that gazelles have a variety of challenges and hence that support targeted at gazelles is inefficient. While this may be true geographically (i.e. gazelles in the same region or country indeed have many different types of challenges), we would argue that it is not the case when putting the lens on gazelles of a specific industry. In our study, through the focus on the construction industry, we were able to find a clear pattern of gazelle challenges.

6. Conclusion

The aim of this study was to identify challenged encountered by gazelles and the support provided by intermediary actors to cope with such challenges. Focusing gazelles in the construction industry in the geographic area of Norrköping (Sweden), we conducted interviews with gazelle companies and with the intermediary actors supporting (either formally or informally) the gazelles.

Results indicate that gazelles are faced with challenges related to a lack of network and collaborations, institutions, competence development and human resource management. Some of these challenges are a consequence of the environment and the industry and hence are not specific to gazelles. Nevertheless, in line with previous literature, we argue that the fact that gazelles, due to their intensive growth process, characteristics (e.g. young age, size) and limited resources, is reinforcing the impact of these challenges.

This study contributes to one more empirical example of gazelles faced with challenges related to strategy and resources. The gazelles interviewed in this study lack long-term strategy, e.g. when building networks and collaborations, competences or when choosing projects. Surprisingly, the resources that were lacking the most were not related to financial resources. Instead, the lack of manpower, competences and time were prevalent.

Our findings also shed a light on the support provided to gazelles by intermediary actors. It was found that an ecology of actors support gazelles; some of them are formal intermediaries, i.e. they have a mission to support gazelles, and some are informal ones, i.e. they provide support to gazelles on the side of their main mission. Likewise, the large majority of intermediaries do not target gazelles, but instead provide support to a variety of actors. This lack of targeted support, combined with the lack of long-term strategy of gazelles, may explain why, in line with previous literature, gazelles are rather unsatisfied with the support they receive from intermediaries.

We draw some implications based on the observed mismatch between gazelles’ challenges and intermediary support. First, we suggest that gazelles should get the opportunity to delegate administrative tasks to intermediaries. Our results indicate that some tasks may be externalized for gazelles’ managers to get more time to focus on long-term strategic issues. Externalizing tasks is not a new type of intermediation activity, but it may be a management approach that gazelles are not used to apply. Second, we suggest that specific functions at the municipal, regional and national institutions are created to communicate with gazelles, for instance, by guiding them through complex administrative processes or to gather inputs on current challenges. For such strategy, having the appropriate intermediary competences at the right institutional level is however crucial for a maximal impact on growth (cf. Cannavacciuolo, Capaldo, and Rippa Citation2015).

Acknowledgments

The support of the Swedish Energy Agency (Project 49379-1) is gratefully acknowledged by I. Mignon.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abd-Hamid, Z., N. Azizan, and S. Sorooshian. 2015. “Predictors for the Success and Survival of Entrepreneurs in the Construction Industry.” International Journal of Engineering Business Management 7: 12. doi:10.5772/60530

- Acs, Z., and C. Armington. 2004. “Employment Growth and Entrepreneurial Activity in Cities.” Regional Studies 38: 911–927. doi:10.1080/0034340042000280938

- Allen, I., A. Elam, N. Langowitz, and M. Dean. 2007. “2007 Report on Women and Entrepreneurship.” In G. E. Monitor (Eds.). Wellesley, MA: Babson College.

- Almroth, P., and S. Kolsgård. 1981. “Näringsliv.” In Linköpings Historia V, 1910–1970, edited by S. Hellström, 29–105. Örebro: Ljungföretagen.

- Anyadike-Danes, M., M. Hart, and J. Du. 2015. “Firm Dynamics and Job Creation in the United Kingdom: 1998–2013.” International Small Business Journal 33: 12–27. doi:10.1177/0266242614552334

- Audretsch, D., and I. Peña-Legazkue. 2012. “Entrepreneurial Activity and Regional Competitiveness: An Introduction to the Special Issue.” Small Business Economics 39: 531–537. doi:10.1007/s11187-011-9328-5

- Autio, E., A. Kovalainen, and M. Kronlund. 2007. High-Growth SME Support Initiatives in Nine Countries: Analysis, Categorization, and Recommendations: Report Prepared for the Finnish Ministry of Trade and Industry, Helsinki.

- Autio, E., H. Sapienza, and J. Almeida. 2000. “Effects of Age at Entry, Knowledge Intensity, and Imitability on International Growth.” Academy of Management Journal 43: 909–924.

- Barbero, J., J. Casillas, and H. Feldman. 2011. “Managerial Capabilities and Paths to Growth as Determinants of High-Growth Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises.” International Small Business Journal 29: 671–694. doi:10.1177/0266242610378287

- Bennett, R. 2008. “SME Policy Support in Britain Since the 1990s: What Have We Learnt?” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 26: 375–397. doi:10.1068/c07118

- Bergek, A. 2020. “Diffusion Intermediaries: A Taxonomy Based on Renewable Electricity Technology in Sweden.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 36: 378–392. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2019.11.004

- Bessant, J., and H. Rush. 1995. “Building Bridges for Innovation: The Role of Consultants in Technology Transfer.” Research Policy 24: 97–114. doi:10.1016/0048-7333(93)00751-E

- Birch, D. 1979. The Job Generating Process. Cambridge, MA: MIT.

- Birch, D., A. Haggerty, and P. Willliams. 1995. Who is creating jobs? Boston: Cognetics Inc.

- Bos, J., and E. Stam. 2014. “Gazelles and Industry Growth: A Study of Young High-Growth Firms in The Netherlands.” Industrial and Corporate Change 23: 145–169.

- Børsen, T. 2008. “Developing Ethics Competencies Among Science Students at the University of Copenhagen.” European Journal of Engineering Education 33: 179–186. doi:10.1080/03043790801987735

- Bravo-Biosca, A. 2010. Firm Growth Dynamics Across Countries: Evidence from a New Database, Nesta and FORA Working Paper, London.

- Briscoe, G., A. Dainty, S. Millett, and R. Neale. 2004. “Client-led Strategies for Construction Supply Chain Improvement.” Construction Management and Economics 22: 193–201. doi:10.1080/0144619042000201394

- Brown, R., G. Gregson, and C. Mason. 2016. “A Post-Mortem of Regional Innovation Policy Failure: Scotland's Intermediate Technology Initiative (ITI).” Regional Studies 50: 1260–1272. doi:10.1080/00343404.2014.985644

- Brown, R., C. Mason, and S. Mawson. 2014. Increasing'the Vital 6 Percent': Designing Effective Public Policy to Support High Growth Firms.

- Brown, R., and S. Mawson. 2016. “Targeted Support for High Growth Firms: Theoretical Constraints, Unintended Consequences and Future Policy Challenges.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 34: 816–836. doi:10.1177/0263774X15614680

- Brown, R., S. Mawson, and C. Mason. 2017. “Myth-Busting and Entrepreneurship Policy: The Case of High Growth Firms.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 29: 414–443. doi:10.1080/08985626.2017.1291762

- Brush, C., D. Ceru, and R. Blackburn. 2009. “Pathways to Entrepreneurial Growth: The Influence of Management, Marketing, and Money.” Business Horizons 52: 481–491. doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2009.05.003

- Cannavacciuolo, L., G. Capaldo, and P. Rippa. 2015. “Innovation Processes in Moderately Innovative Countries: the Competencies of Knowledge Brokers.” International Journal of Innovation and Sustainable Development 9: 63–82. doi:10.1504/IJISD.2015.067349

- Clark, J. 2014. “Manufacturing by Design: The Rise of Regional Intermediaries and the re-Emergence of Collective Action.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 7: 433–448. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsu017

- Cunneen, D., and G. Meredith. 2007. “Entrepreneurial Founding Activities That Create Gazelles.” Small Enterprise Research 15: 39–59. doi:10.1080/13215906.2007.11005831

- Daunfeldt, S., and D. Halvarsson. 2015. “Are High-Growth Firms One-Hit Wonders?” Evidence from Sweden. Small Business Economics 44: 361–383. doi:10.1007/s11187-014-9599-8

- Davidsson, P., and F. Delmar. 2006. High-Growth Firms and Their Contribution to Employment: The Case of Sweden 1987–96. Entrepreneurship and the Growth of Firms. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Delmar, F., P. Davidsson, and W. Gartner. 2003. “Arriving at the High-Growth Firm.” Journal of Business Venturing 18: 189–216. doi:10.1016/S0883-9026(02)00080-0

- Demir, R., K. Wennberg, and A. McKelvie. 2017. “The Strategic Management of High-Growth Firms: A Review and Theoretical Conceptualization.” Long Range Planning 50: 431–456. doi:10.1016/j.lrp.2016.09.004

- Dubois, A., and L. Gadde. 2000. “Supply Strategy and Network Effects—Purchasing Behaviour in the Construction Industry.” European Journal of Purchasing & Supply Management 6: 207–215. doi:10.1016/S0969-7012(00)00016-2

- Fellini, I., A. Ferro, and G. Fullin. 2007. “Recruitment Processes and Labour Mobility: The Construction Industry in Europe.” Work, Employment and Society 21: 277–298. doi:10.1177/0950017007076635

- Fischer, E., and A. Reuber. 2003. “Support for Rapid-Growth Firms: A Comparison of the Views of Founders, Government Policymakers, and Private Sector Resource Providers.” Journal of Small Business Management 41: 346–365. doi:10.1111/1540-627X.00087

- Fredin, S. 2016. “Breaking the Cognitive Dimension of Local Path Dependence: An Entrepreneurial Perspective. Geografiska Annaler: Series B.” Human Geography 98: 239–253.

- Georgallis, P., and R. Durand. 2017. “Achieving High Growth in Policy-Dependent Industries: Differences Between Startups and Corporate-Backed Ventures.” Long Range Planning 50: 487–500. doi:10.1016/j.lrp.2016.06.005

- Geroski, P., S. Machin, and C. Walters. 1997. “Corporate Growth and Profitability.” The Journal of Industrial Economics 45: 171–189. doi:10.1111/1467-6451.00042

- Gupta, P., S. Guha, and S. Krishnaswami. 2013. “Firm Growth and its Determinants.” Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship 2: 15. doi:10.1186/2192-5372-2-15

- Henrekson, M., and D. Johansson. 2010. “Gazelles as Job Creators: A Survey and Interpretation of the Evidence.” Small Business Economics 35: 227–244. doi:10.1007/s11187-009-9172-z

- Hermelin, B. 2018. Norrköpings arbetsmarknad i förändring: Strukturomvandling och lokal sysselsättning. Linköping: Linköping University Electronic Press.

- Hoffmann, A., and M. Junge. 2006. Documenting Data on High-Growth Firms and Entrepreneurs Across 17 Countries. (First Draft), FORA Working Paper, Copenhagen.

- Howells, J. 2006. “Intermediation and the Role of Intermediaries in Innovation.” Research Policy 35: 715–728. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2006.03.005

- Hölzl, W. 2014. “Persistence, Survival, and Growth: A Closer Look at 20 Years of Fast-Growing Firms in Austria.” Industrial and Corporate Change 23: 199–231. doi:10.1093/icc/dtt054

- Hölzl, W., and K. Friesenbichler. 2010. “High-Growth Firms, Innovation and the Distance to the Frontier.” Economics Bulletin 30: 1016–1024.

- Järvstråt, L. 2011. Analys av flyttmönster i Norrköpings kommun. Linköping: Linköping University.

- Kalbro, T., H. Lind, and S. Lundström. 2009. “En flexibel och effektiv bostadsmarknad-problem och åtgärder. Fastigheter och byggande.” Rapport 4: 111.

- Kanda, W., S. Mejiá-Dugand, and O. Hjelm. 2015. “Governmental Export Promotion Initiatives: Awareness, Participation, and Perceived Effectiveness Among Swedish Environmental Technology Firms.” Journal of Cleaner Production 98: 222–228. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.11.013

- Kane, L. 2010. “Community Development: Learning from Popular Education in Latin America.” Community Development Journal 45: 276–286. doi:10.1093/cdj/bsq021

- Keen, C., and H. Etemad. 2012. “Rapid Growth and Rapid Internationalization: The Case of Smaller Enterprises from Canada.” Management Decision 50: 569–590. doi:10.1108/00251741211220138

- Khan, S., and R. VanWynsberghe. 2008. Cultivating the Under-Mined: Cross-Case Analysis as Knowledge Mobilization, Forum qualitative Sozialforschung/forum: Qualitative social research.

- Klerkx, L., A. Hall, and C. Leeuwis. 2009. “Strengthening Agricultural Innovation Capacity: Are Innovation Brokers the Answer?” International Journal of Agricultural Resources Governance and Ecology 8: 409–438.

- Klerkx, L., and C. Leeuwis. 2009. “Establishment and Embedding of Innovation Brokers at Different Innovation System Levels: Insights from the Dutch Agricultural Sector.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 76: 849–860. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2008.10.001

- Koski, H., and M. Pajarinen. 2013. “The Role of Business Subsidies in Job Creation of Start-ups, Gazelles and Incumbents.” Small Business Economics 41: 195–214. doi:10.1007/s11187-012-9420-5

- Laur, I., M. Klofsten, and D. Bienkowska. 2012. “Catching Regional Development Dreams: A Study of Cluster Initiatives as Intermediaries.” European Planning Studies 20: 1909–1921. doi:10.1080/09654313.2012.725161

- Lee, N. 2014. “What Holds Back High-Growth Firms? Evidence from UK SMEs.” Small Business Economics 43: 183–195. doi:10.1007/s11187-013-9525-5

- Lerner, J. 2010. “The Future of Public Efforts to Boost Entrepreneurship and Venture Capital.” Small Business Economics 35: 255–264. doi:10.1007/s11187-010-9298-z

- Lerner, M., and S. Haber. 2001. “Performance Factors of Small Tourism Ventures: The Interface of Tourism, Entrepreneurship and the Environment.” Journal of Business Venturing 16: 77–100. doi:10.1016/S0883-9026(99)00038-5

- London, K., and R. Kenley. 2000. Mapping Construction Supply Chains: Widening the Traditional Perspective of the Industry, EAIRE 2000: Proceedings 27th Annual European Association of Research in Industrial Economic EARIE Conference, 7–10 September, 2000, Lausanne, Switzerland.

- MacKenzie, R., C. Forde, A. Robinson, H. Cook, B. Eriksson, P. Larsson, and A. Bergman. 2010. “Contingent Work in the UK and Sweden: Evidence from the Construction Industry.” Industrial Relations Journal 41: 603–621. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2338.2010.00588.x

- Markman, G., and W. Gartner. 2002. “Is Extraordinary Growth Profitable? A Study of Inc. 500 High–Growth Companies.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 27: 65–75.

- Mason, C., and R. Brown. 2013. “Creating Good Public Policy to Support High-Growth Firms.” Small Business Economics 40: 211–225. doi:10.1007/s11187-011-9369-9

- McKelvie, A., and J. Wiklund. 2010. “Advancing Firm Growth Research: A Focus on Growth Mode Instead of Growth Rate.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 34: 261–288. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00375.x

- Mignon, I. 2017. “Intermediary-user Collaboration During the Innovation Implementation Process.” Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 29 (7): 735–749. doi:10.1080/09537325.2016.1231299

- Moreno, A., and J. Casillas. 2008. “Entrepreneurial Orientation and Growth of SMEs: A Causal Model.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 32: 507–528. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2008.00238.x

- Morgan, K., and C. Nauwelaers. 1999. Regional Innovation Strategies: The Challenge for Less Favoured Regions. London: Psychology Press.

- Moss, T. 2009. “Intermediaries and the Governance of Sociotechnical Networks in Transition.” Environment and Planning A 41: 1480–1495. doi:10.1068/a4116

- Muurlink, O., A. Wilkinson, D. Peetz, and K. Townsend. 2012. “Managerial Autism: Threat–Rigidity and Rigidity's Threat.” British Journal of Management 23: S74–S87. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8551.2011.00790.x

- NESTA. 2009. The Vital 6 Per cent: How High-Growth Innovative Businesses Generate Prosperity and Jobs, edited by A. Bravo-Biosca, and S. Westlake. London.

- Nightingale, P., and A. Coad. 2014. “Muppets and Gazelles: Political and Methodological Biases in Entrepreneurship Research.” Industrial and Corporate Change 23: 113–143. doi:10.1093/icc/dtt057

- OECD. 2011. High-Growth Enterprises: What Governments Can do to Make a Difference, Paris: A Study by the OECD Working Party on SMEs and Entrepreneurship. Paris: OECD.

- Penrose, E. 2009. The Theory of the Growth of the Firm. Oxford: Oxford university press.

- Pitelis, C. 2012. “Clusters, Entrepreneurial Ecosystem co-creation, and Appropriability: A Conceptual Framework.” Industrial and Corporate Change 21: 1359–1388. doi:10.1093/icc/dts008

- Poncet, J., M. Kuper, and J. Chiche. 2010. “Wandering Off the Paths of Planned Innovation: The Role of Formal and Informal Intermediaries in a Large-Scale Irrigation Scheme in Morocco.” Agricultural Systems 103: 171–179.

- Porter, M. 1998. “Clusters and the New Economics of Competition.” Harvard Business Review 76: 77–90.

- Pries, F., and F. Janszen. 1995. “Innovation in the Construction Industry: The Dominant Role of the Environment.” Construction Management and Economics 13: 43–51. doi:10.1080/01446199500000006

- Qvarsell, R., A. Cederborg, and B. Linnér. 2005. Campus Norrköping. En studie i universitetspolitik. Centrum för kommunstrategiska studier, Norrköping.

- Ragins, B. 1997. “Diversified Mentoring Relationships in Organizations: A Power Perspective.” Academy of Management Review 22: 482–521. doi:10.5465/amr.1997.9707154067

- Senderovitz, M., K. Klyver, and P. Steffens. 2016. “Four Years on: Are the Gazelles Still Running? A Longitudinal Study of Firm Performance After a Period of Rapid Growth.” International Small Business Journal 34: 391–411.

- Shane, S. 2009. “Why Encouraging More People to Become Entrepreneurs is Bad Public Policy.” Small Business Economics 33: 141–149. doi:10.1007/s11187-009-9215-5

- Shehu, Z., and A. Akintoye. 2010. “Major Challenges to the Successful Implementation and Practice of Programme Management in the Construction Environment: A Critical Analysis.” International Journal of Project Management 28: 26–39. doi:10.1016/j.ijproman.2009.02.004

- Smallbone, D., R. Baldock, and S. Burgess. 2002. “Targeted Support for High-Growth Start-Ups: Some Policy Issues.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 20: 195–209. doi:10.1068/c0049

- Spithoven, A., and M. Knockaert. 2012. “Technology Intermediaries in Low Tech Sectors: The Case of Collective Research Centres in Belgium.” Innovation 14: 375–387. doi:10.5172/impp.2012.14.3.375

- Stam, E. 2010. “Growth Beyond Gibrat: Firm Growth Processes and Strategies.” Small Business Economics 35: 129–135. doi:10.1007/s11187-010-9294-3