ABSTRACT

Public procurement of innovation is a key policy instrument for improving the quality of public services and achieving wider benefits for society. Recently, innovation contests have re-emerged as a means to procure innovative new solutions. There is, however, limited understanding of how innovation contests should be organized in the public sector. In this study, we investigate the organization of two smart city hackathon-style innovation contests in Tampere, Finland. We examine the contests’ structure and goals, the definition of a problem statement, the motivation of potential participants, and their outcomes. We find that innovation contests may be used for, not only sourcing novel technologies, but also for engaging in conversations with companies, and developing an understanding of local problems and potential solutions. We further discuss the issues that arise from the integration of multiple goals in a single contest. We provide practical guidance for organizing innovation contests and evaluate their role for public procurement of innovation and local development.

Introduction

Public procurement of innovation has recently emerged a key innovation policy instrument (Edquist and Zabala-Iturriagagoitia Citation2012; Uyarra et al. Citation2020; Uyarra and Flanagan Citation2010). Via procurement, the public sector may encourage private companies to invest more in the innovation (Uyarra et al. Citation2014), help them cross the ‘valley of death’ between development and commercialization (Edler and Georghiou Citation2007), and facilitate the diffusion of innovative solutions (Edquist and Zabala-Iturriagagoitia Citation2012). Public procurement of innovation is considered to hold potential for fulfilling the procurement needs of public organizations better than existing solutions and achieving wider benefits for society (Uyarra et al. Citation2020).

Public procurers have recently turned their eyes on innovation contests to support public procurement of innovation. Innovation contests are an open innovation method where an organization posts a challenge and promises a reward to attract multiple companies to develop solutions to solve the challenge (Adamczyk, Bullinger, and Möslein Citation2012). In the US, public agencies such as NASA and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) have long offered innovation inducement prizes for incentivising the development of new technologies (Williams Citation2012). In the UK, the Big Green Challenge, where a contest with £1 m prize was designed to encourage and support community-led responses to climate change is a well-known example (Tjornbo and Westley Citation2012). Recently, innovation contests have gained more attention due to legislative changes and rapidly progressing digitization (Liotard and Revest Citation2018). There is a wide variety of contests that are in use in the public sector. They vary from massive competitions that last for months and have multi-million dollar prizes to small-scale hackathons that are over in a day or less.

However, there is a lack of understanding of how to organize innovation contests in the public sector. In the private sector, contests are typically targeted at well-defined (technical) problems, and it is possible to identify some best practices (Ford, Richard, and Ciuchta Citation2015; Gillier et al. Citation2018). Public sector organizations, in contrast, have more broad aims than corporations, including promoting open governance and civic engagement and supporting the emergence of innovative businesses and economic development in their respective regions (Bleda and Chicot Citation2020; Carr and Lassiter Citation2017; Hartmann, Mainka, and Stock Citation2016; Johnson and Robinson Citation2014; Mergel and Desouza Citation2013; Sotarauta Citation2009). In making decisions on innovation contest design, various trade-offs need to be considered (Dahlander, Jeppesen, and Piezunka Citation2019), and, in the public sector, the integration of priorities from various policy areas creates additional trade-offs that need to be balanced, generating a complex managerial challenge between strategic leadership and operational environment (Sotarauta Citation2005; Sotarauta and Mustikkamäki Citation2012). Procurers often lack skills and experience in procuring for innovations in general (Georghiou et al. Citation2014; Obwegeser and Müller Citation2018), especially when it comes to innovation contests (Carr and Lassiter Citation2017). Unfortunately, few studies address their organization, apart from reports of well-known ambitious innovation contests (Adler Citation2011; Kay Citation2012; Mergel and Desouza Citation2013; Stine Citation2009), such as the Ansari X-prize contest organized by NASA. However, such examples are relevant for only a few because of their massive size and resource needs. In sum, despite the recent attention to innovation contests as an innovation policy tool, there is a lack of understanding of organizing them. This is the research gap that this study aims to address.

We adopt a case study research design to investigate two smart city hackathon-style innovation contests organized by the city of Tampere, Finland. We identify key dimensions of organizing contests from a literature review of public sector innovation contests. These include decisions related to several key questions, such as the hackathon type, definition of the problem statement, and ways to motivate the participants. We argue that these decisions influence the extent to which a hackathon's outcomes may fulfil the organizers’ aims. We then conduct an in-depth investigation of our case contests and examine the aims, implementation, and outcomes of the hackathons. In specific, we seek answers to the following research question.

RQ: How should a city organize innovation contests for the public procurement of innovation?

Theoretical framework

Public procurement of innovation

The goal of public procurement has traditionally been efficiency: obtaining desired goods or services at the lowest price. Recently, the potential of public procurement as an innovation policy tool has received attention (Edquist and Zabala-Iturriagagoitia Citation2012; Uyarra et al. Citation2020). Traditional public procurement typically targets ready-made products and services. In contrast, when public organizations engage in public procurement of innovation, they place orders to fulfil specific needs and expect companies to address them by offering innovative solutions (Edquist, Vonortas, and Zabala-Iturriagagoitia Citation2015). The primary goal of public procurement of innovation is ensuring the quality of public services by gaining access to the best available products and services (Uyarra and Flanagan Citation2010). Also, there may be secondary goals linked with broader policy objectives, such as promoting the growth of innovative companies.

By creating demand for innovative solutions, public organizations may stimulate private sector innovation. Public organizations, such as local city governments, may facilitate innovation activities in their region and beyond and innovate new solutions for the local city government needs in collaboration with the private sector (Makkonen, Merisalo, and Inkinen Citation2018). They may also act as a lead user for novel products and services by being the first customer to buy and apply them. As a lead user, the government takes the risk of working with technologies that may not be fully optimized yet in exchange for achieving desired solutions to identified problems more quickly and providing valuable references for companies (Edler and Georghiou Citation2007). Procurement processes also provide opportunities for socially and spatially embedded ‘conversations’ that facilitate knowledge exchange and collective learning that promote innovation by helping different actors understand their individual needs and available resources and create shared future visions (Lester and Piore Citation2004; Rutten Citation2017; Uyarra et al. Citation2017; van Winden and Carvalho Citation2019). Besides economic goals, public procurement of innovation is often associated with promoting social and environmental objectives (Lember, Kalvet, and Kattel Citation2011). Public organizations may, for example, aim to achieve their carbon neutrality goals through the procurement of innovative clean technologies (Alhola and Nissinen Citation2018). In the recent discussions on transformative and mission-oriented innovation policy (Mazzucato Citation2018; Schot and Steinmueller Citation2018), public procurement of innovation is considered a critical method for responding to grand challenges such as climate change and ageing (Edquist and Zabala-Iturriagagoitia Citation2012; Uyarra et al. Citation2020).

Different types of public procurement of innovation have been identified. Researchers and practitioners widely use a distinction between pre-commercial procurement (PCP) and public procurement of innovative solutions (PPI). PCP concerns the phase before commercialization, where further R&D is needed before a solution may be used (Edquist and Zabala-Iturriagagoitia Citation2015). When engaging in PCP, a public organization provides funding to a company to develop a concept, prototype or a demonstration of a new solution. PCP does not automatically lead to the procurement of the developed solution. However, it decreases the level of risk associated with innovation and may lead to the generation of solutions that would otherwise have not realized. In contrast, PPI facilitates the wide diffusion of innovative solutions on the market by providing ‘a large enough demand to incentivise industry to invest in wide commercialization to bring innovative solutions to the market with the quality and price needed for mass-market deployment’ (European Commission Citation2018).

The broad acknowledgement of the benefits of public procurement of innovation has encouraged public organizations to seek novel procurement methods that help achieve them. Since 2016, the public procurement rules in the European Union have allowed a new procurement procedure – innovation partnership – that combines the development of a new solution and the purchase of the developed solution in a single procurement (Directive 2014/24/EU (49)). Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs), where public sector bodies enter into long-term contractual agreements with private companies have been found valuable in stimulating innovation in the infrastructure construction sector (Carbonara and Pellegrino Citation2018). Finally, public agencies have adopted open innovation tools and methods, such as co-creation workshops, crowdsourcing, and stakeholder engagement, to foster interactions with the private sector (Liotard and Revest Citation2018; Timmermans and Zabala-Iturriagagoitia Citation2013; Torvinen and Ulkuniemi Citation2016).

Innovation contests as a policy instrument

Innovation contests are an open innovation method currently experiencing a sort of renaissance within innovation policy. Different prizes and contests have been in use for hundreds of years to stimulate innovation (Scotchmer Citation2004). However, only recently have they been studied as policy tools (Liotard and Revest Citation2018). In an innovation contest, an organization posts a challenge and promises a reward to attract multiple participants to develop solutions to solve the challenge (Adamczyk, Bullinger, and Möslein Citation2012). Innovation contests can be considered a form of crowdsourcing, where a task is outsourced to an undefined network of people or organizations in the form of an open call (Howe Citation2008).

The increased attention on innovation contests can be explained by legislative changes and rapidly progressing digitization (Liotard and Revest Citation2018). In 2010, the America COMPETES Act was adopted in the US that allows public agencies to conduct prize competitions. After this legislative change, innovation contests have been applied in solving hundreds of problems related to topics ranging from health care and education to environment and national security (Desouza Citation2012). European Commission has also promoted open data competitions to foster the development of new information services (European Commission Citation2011). Whether they focus on commercialization or the stimulation of new ideas, innovation contests may include elements of either of the PCP and PPI types of public procurement of innovation (Liotard and Revest Citation2018).

There is a wide variety of contests that are in use in the public sector. Smaller contests often take the form of hackathons, that is events that bring together participants (often programmers) to work intensively over a short time to solve a problem (Briscoe and Mulligan Citation2014). Smart cities have been identified as an area where innovation contests have particularly significant potential. The concept of smart cities refers to urban areas where information and communications technology is used to improve its operations (Caragliu, Del Bo, and Nijkamp Citation2011). By collecting and using data from various sources, it becomes possible to generate improvements both in the ‘hard domain’, such as buildings, energy grids, natural resources, water management, waste management, mobility, and logistics and in the ‘soft domain’, such as education, culture, policy innovations, social inclusion, and government (Albino, Berardi, and Dangelico Citation2015). Access to big data, which may be sensor-based or user-generated, provides ample opportunities for service development. Many cities use innovation contests to find ways to identify and benefit from these opportunities (Hartmann, Mainka, and Stock Citation2016; Johnson and Robinson Citation2014).

Organizing innovation contests

As public organizations have adopted public procurement of innovation in their policy repertoire and started to use methods such as hackathons, concerns have been raised about their capability to carry such activities out successfully. Innovative companies face numerous barriers related to processes, competencies, procedures, and relationships that prevent the generation of innovations in public procurement (Uyarra et al. Citation2014). In terms of the stimulation of private R&D effort, many innovation contests may be considered successful. Whether that effort is transformed into valuable innovations is not so clear. Many of the services that they generate are already available in more mature forms from the market (Carr and Lassiter Citation2017). Johnson and Robinson (Citation2014) argue that more research is needed to conclude whether innovation contests are useful in generating long-term impacts or whether they are mere ‘stunts’ to create short-term buzz. Some authors, however, argue that a broader perspective on the benefits from innovation contests should be adopted. In addition to acquiring new solutions, contests may enable the creation of new public resources (e.g. new data repositories), increase awareness of social issues, facilitate learning on public procurement of innovation, or establish new partnerships in the public sphere (Mergel and Desouza Citation2013; van Winden and Carvalho Citation2019). They may also provide a stimulus for new companies and job creation and orient consumers toward defined markets (Liotard and Revest Citation2018).

Nevertheless, concerns over the effectiveness of innovation contests should not be disregarded. Innovative procurement activities are complex, and their management requires expertise beyond procurers’ traditional domain (Obwegeser and Müller Citation2018). Innovation contests are inherently an open-ended and risky activity that requires strategic leadership (Sotarauta and Mustikkamäki Citation2012). However, procurers often lack skills and experience in procuring for innovations, resulting in high costs or modest outcomes (Georghiou et al. Citation2014). Carr and Lassiter (Citation2017) argue that despite a high degree of enthusiasm for innovation contests, the results remain modest due to a lack of professionalism in organizing them. According to them, more understanding of best practices in organizing innovation contests is needed before becoming a useful policy tool.

The extant literature on public sector innovation contests suggests different contest design elements that organizers need to acknowledge. A key to organizing a successful innovation contest is aligning the design elements with the contest’s goals. Therefore, organizations need the ability to align the organization’s strategic goals with more specific project goals (Sotarauta Citation2009). While more detailed lists of relevant design elements are available (Adamczyk, Bullinger, and Möslein Citation2012), the main aspects can be summarized in three points: structure, problem statement, and participant motivation.

An innovation contest's structure concerns the overall set-up regarding its size, timespan, process phases, and practical arrangements (e.g. face-to-face vs online). Innovation contests may take many forms ranging from online idea platforms that require little commitment from the participants to intensive long-term development endeavours. Depending on the chosen format, contests may vary in length, the intensity of interactions, and the number of involved stakeholders (Liotard and Revest Citation2018). Crowdsourcing platforms, which are often provided by private companies such as Innocentive or NineSigma, may be used to attract numerous solvers with little interactions (Davis, Richard, and Keeton Citation2015). However, they may remain too detached from the public sector organization and its goals (Blohm et al. Citation2018). Hackathons typically comprise a 1–3-day event at a determined location, whereas more massive app competitions may last for several months before a solution is submitted (Hartmann, Mainka, and Stock Citation2016). Large competitions may attract more participants and lead to better solutions, but they are arduous to manage (Desouza Citation2012). On the other hand, smaller competitions may be unable to tackle large and complex challenges (van Winden and Carvalho Citation2019). Contests also vary in the number of phases. Sometimes multiple rounds are used to raise the elaborateness of the submissions in each phase (Adamczyk, Bullinger, and Möslein Citation2012), and each development phase is followed by an elimination round that only the most promising solutions survive (Terwiesch and Ulrich Citation2009). Multi-phase contests allow organizers to invest in the most promising solutions, but they come with increased bureaucracy and longer procurement processes (van Winden and Carvalho Citation2019). This variety of contest structures makes innovation contests a versatile tool for acquiring new ideas and solutions, but at the same time requires careful consideration from the organizers: a suitable contest type needs to be decided for the specific problem at hand.

In innovation contests, defining a problem statement is the leading way for guiding the participants in developing needed solutions. With a clear problem statement, a public organization’s need is crystallised in a condensed and accessible format. Hartmann, Mainka, and Stock (Citation2016) note that the scope of innovation contests varies greatly from broad themes, such as mobility, to specific solutions and tools for APIs. The more ‘difficult, intractable or wicked’ the problem is, the more complex and challenging this process of demand articulation becomes (Uyarra et al. Citation2020, 3). Carr and Lassiter (Citation2017) suggest that it is complicated for outsiders to understand the context of the problem in a short time and produce meaningful and valuable solutions. Hence, the organizers need to provide a clear description of their problem (Adamczyk, Bullinger, and Möslein Citation2012). To help in this, Spradlin (Citation2012) proposes that organizations should first clarify the need for a solution internally, articulate why it is essential, research how others have already tried to solve the problem, and finally create a clear and complete description of the previous points for the participants. The problem statement functions as a basis on top of which other contest guidelines and materials can be produced. The organizers also need to specify with what kind of solutions the solution providers are eligible to participate, how the solutions will be evaluated, and the practical context that the problem is embedded in (Mergel and Desouza Citation2013).

A critical task in organizing innovation contests is deciding who is eligible or wanted to participate (Liotard and Revest Citation2018). This enables the organizers to think of appropriate incentives for them; in other words, how to motivate the participants. The most visible motivational factor in innovation contests is usually a monetary prize for the winner solution. The prize sums are typically defined in advance, but the payment size can also be proportional to the measured impact of the winning solutions (Masters and Delbecq Citation2008). In many cases, non-monetary rewards may, however, have a significant role in attracting participants. The contests may offer the opportunity to increase knowledge and personal skills, network with public sector organizations and other developers, gain reputation, visibility, and credibility that may be beneficial for seizing future commercial opportunities (Liotard and Revest Citation2018; Mergel and Desouza Citation2013; van Winden and Carvalho Citation2019). Mergel and Desouza (Citation2013) emphasize that a good understanding of the desired participants’ expectations and social and economic realities is needed to choose the right kind of incentives. This notion, however, presumes that potential participants have already been identified. The core logic of innovation contests relies on some degree of open-endedness: instead of asking known companies to submit a proposal, the challenge is broadcasted to more or less undefined audiences. If the contest is targeted to a pre-defined group, motivating the participants is easier, but the solutions’ diversity and innovativeness may suffer (Dahlander, Jeppesen, and Piezunka Citation2019). In contrast, motivating people without understanding who they may be is difficult as their motivation and goals may differ. Almirall, Lee, and Majchrzak (Citation2014) find that, when using hackathons, cities should engage with established hacker communities. This relieves them from attracting contributors and makes their primary role to provide open datasets for the contestants. Cities should, however, be aware that participants from hacker communities may operate under a different logic than companies, and the two groups are unlikely to respond to similar motivating efforts (O’Mahony and Bechky Citation2008).

Methodology

We chose the city of Tampere, Finland, for our case organization based on it having a high strategic priority on and experience of public procurement of innovation. Based on discussion with city representatives, we identified two recent smart city hackathons. The hackathons shared a theme, both relating to ongoing smart city development projects, including an EU-funded STARDUST smart city project, but differed in the actual implementation. Investigating two hackathon processes allows us to deepen our inquiry by paying attention to their differences while controlling some variation that could arise from differences in the subject matter.

The data set for the study comprises documents and interviews. The city had prepared two detailed 20-page reports of the two procurement processes that provided a sound basis for getting to know the cases (Vehviläinen Citation2019; Vilhula and Vehviläinen Citation2020). Further documents such as presentations, procurement documents, and news articles were collected to complement the report. Moreover, we interviewed five key people who contributed to the planning and implementation of the hackathons at Tampere and three hackathon participants. The documents include information about the hackathon processes and their outcomes, and the interviews focused on normative evaluations and experiences of them. A semi-structured interview guide was used in all of the interviews. The guide included following themes: background and aims for the hackathon, process of the problem statement and ways to motivate the participants, implementation of the hackathons, a reflection of the hackathons’ success, and critical decisions. Same themes were discussed with the hackathon participants from their perspectives (e.g. background and aims of the company to participate, and the problem statement from the company perspective). All interviews were then recorded and transcribed verbatim.

The analysis process was structured by the critical organizing categories identified based on extant research. Relevant material from the documents and interview transcripts were summarized into a reduced form. By organizing the material into cross-case matrixes, similarities and differences between the two studied cases could be identified (Miles, Huberman, and Saldaña Citation2014). Key insights are summarized in .

Table 1. A summary of the cases.

Results

Background and structure of the hackathons

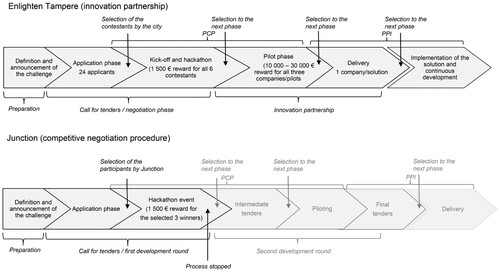

We explored two different hackathons called Enlighten Tampere and Junction, whose processes are depicted in . The first hackathon, Enlighten Tampere, was organized in June 2018 by the city itself in cooperation with an external facilitator. The challenge of Enlighten Tampere was announced in the national public procurement announcement platform HILMA and on the facilitator’s website. Twenty-four companies applied to the hackathon and six teams were selected. Before the actual hackathon, an introductory event was organized where information about the challenge and available resources and mentors were disseminated. The teams started working on their solutions already before the actual hackathon event, i.e. a two-day co-development camp. The second hackathon, Junction, is a big yearly technology event that gathers over 1 000 international participants every year. The two-day event is organized by a volunteer-based non-profit organization, Startup Foundation, which promotes the Nordic startup ecosystems.

Figure 1. Two hackathon processes organized by the city of Tampere. Modified from Vehviläinen (Citation2019).

Both hackathons were joint actions by multiple city initiatives: three EU-funded research and development projects and a Smart Tampere development programme. The projects implemented new methods for supporting the city’s transformation to a smart, efficient, and citizen-orientated organization, and to create an opportunity for startups to develop new services and get customer references (Vehviläinen Citation2019). Finding innovative solutions was one of the main goals for the hackathons as the following quote shows:

We wanted to see what kinds of innovative services or solutions can be found from the market. That is the main goal in the public procurement of innovation that the buyer knows the need but not the best solution. Markets or companies are the best to tell how the need could be solved and what are the new technologies to be used. This was our main point that the city does not know all the opportunities from the market, and this pushed us to find solutions through the contest and the challenge.

Also, the communicative side [was important]. We want to show outside that the city also procures by these methods. We wanted to show that the city can be an interesting partner also for smaller companies.

This was an opportunity to do [procurement] in a different way. A key motivation for the city was to learn different methods and how to implement those. Thus, to educate your organisation and to learn [were important goals].

We had not enough time for the selection. The event space was big, and the teams were spread out all over the big space. It took time to find where the teams situated. The space was noisy, and it was difficult to hear. Also, our group of judges was big, and we needed to make compromises. None of the solutions ended up to a pilot.

In Junction, we did not get mentors from the city organisation [to participate in the event]. All, or at least majority, of our employees in the event, were project officers. This led to the situation that the solutions we selected were not new for the city.

Problem statements of the hackathons

The hackathons’ problem statements were co-designed with the three EU-funded projects, the Smart City development programme, public procurement experts of the city, and the hackathon facilitator in Enlighten Tampere. The projects decided to join forces to create more prominent hackathons than what would have been possible if the different projects worked separately. In Enlighten Tampere, the challenge addressed new data-driven applications and experiments. The city’s street lighting system was adopted as a starting point. The challenge had two themes: ‘Enabling a smarter city with data science’ and ‘Designing data-enabled services for the citizens’. Junction’s two challenges, ‘New solutions of mobility’ and ‘New solutions of guidance’, did not have connections to specific technologies.

In both hackathons, the problem statements were relatively openly defined. The interviewees described that the problem statements’ design processes did not derive from a clearly defined problem but a mixture of goals and actors. The processes were described difficult:

It was very, very difficult [to form the problem statement]. Both contests derived from broad goals, and there were no clearly defined problems to be solved. Thus, how to form a clear statement of what we want, it was yes [difficult], we had many workshops to design what we are after.

The reason why we included more people to design the problem statement for Junction was that during Enlighten Tampere we noticed that if we do this in a very project-oriented manner but aim to generate new services that would be used for a long time, we need to have owners for the solutions from the city organisations and that they need to be involved already when formulating the problem statement in order to commit them to the process. Thus, [I now see that] the challenge definitions should come from the owners [of the possible new solutions] from the city organisation whereas the projects should have more financial role in development and testing phase.

Motivating the participants

The city published procurement announcements for both hackathons in national public procurement platform HILMA to raise awareness. In Enlighten Tampere, the city also relied on the hackathon facilitator’s networks and marketing in finding suitable companies. The primary means for motivating the participants was a public procurement of innovation contract that the winner(s) would be offered after the contest. Each team selected to participate in the pilot phase received a reward of 1500 euros and additional compensation of 10 000–30 000 euros for their work during the phase.

In Junction, the city representatives competed for participants’ attention with other organizations, including major corporations. In the event, participants had an opportunity to discuss with different organizations and choose which challenge they start working. Thus, motivating the participants in the event was important. For both hackathons, the city decided that the participants selected for further collaboration need to be companies. However, in Junction, most of the participants were domestic and international students who did not have a company, or a possibility to start a company in Finland. One interviewee assumed the large companies’ challenges were more attractive for the students because they provided them with an opportunity to show their skills for potential future employees. Presumably, these reasons discouraged some participants from starting working on Tampere’s challenge. This issue arose from a poor understanding of the targeted participants:

In Junction, we needed to find a company as a partner, but we did not understand beforehand that there would be that many students. We thought that if we make the precondition that the selected partner needs to be a company, the challenge will motivate especially companies. Also, because the pilot phase was our reward, we thought our challenge would primarily interest companies. However, in the event, and after it, when we received statistics, we understood that only a minority of the participants were companies.

Outcomes of the hackathons and key success factors

In Junction, the city received many good ideas and rewarded three winners with 1500 euros: two for the mobility challenge and one for the guidance challenge. However, the process stopped after the hackathon because none of the solutions originated from an established company. Thus, the contest’s outcomes were restricted mainly to gaining visibility and a positive reputation as experimental city organization, developing a ‘hackathon culture‘ in the city, and capability building for innovation contests and public procurement for innovation. This outcome also raised thoughts of an alternate method of first buying the intellectual property rights to an idea, and later finding a company to implement it.

Enlighten Tampere was successful in filling its goals. All six participants left proposals. The city selected three winners to continue developing and forming a joint solution in three separate pilots focused on mobility, modelling sunlight, and an intelligent light system. One of the solutions also generated subsequent innovation through continuous development. The city’s mobile application Tampere.Finland that was initially planned to gather mobility data for a smart lighting system has later been developed to an extensive city service platform for Tampere residents. This procurement contract is, at the time of writing, continuing having found an owner from the city organization.

The interviewees reflected the hackathons’ goals and outcomes and the success factors and challenges in the process. The process enhanced the city’s capability-building to conduct public procurement of innovation and use hackathons for stimulating innovation. Critical points to consider are partly practical, such as ensuring that the hackathons are organized professionally as they influence the perceptions of the city. Also, a hackathon's nature is critical to match the organization’s goals to find contestants with suitable profiles for the task. Motivating participants, e.g. monetary rewards, is also essential to consider concerning companies’ desired population. Moreover, the findings suggest that formulating a problem statement is one of the most critical factors because it translates the organization's goals and needs to the participants and has a considerable impact on attracting suitable solutions. The problem formulation process demands considerable time and effort from multiple actors from the city. Especially those who would be long-term owners of the procured solution in the organization should be involved.

Discussion

It has been previously noted that innovation contests ‘can supply diverse organizational architectures or designs’ (Liotard and Revest Citation2018, 59) and promote both PCP and PPI (van Winden and Carvalho Citation2019). We propose that they may also fulfil diverse city needs. Whereas at the core of a contest is the idea of giving ‘rewards for new inventions’ (Williams Citation2012, 752), secondary goals were considered highly important in Tampere. Hackathons were understood to produce favourable spillovers by promoting the city’s brand image and supporting economic activity, similar to previous studies’ findings (Liotard and Revest Citation2018; Mergel and Desouza Citation2013). Hackathons were also thought to give business opportunities, especially to small companies, often at a disadvantage in public procurement (Karjalainen and Kemppainen Citation2008; Loader Citation2015). Similar to the organizer, the participants were also motivated by multiple factors. Besides the reward money, they sought contacts, future business opportunities, and an opportunity to learn.

The picture that the studied hackathons paints of innovation contests in the public sector goes beyond the transactional view of crowdsourcing where the interest is on solving a defined task in an effective way (Dahlander, Jeppesen, and Piezunka Citation2019). Instead, they may be viewed as ‘conversations’ – interactive processes where innovations are developed among people from different backgrounds and with different perspectives (Lester and Piore Citation2004; Rutten Citation2017; Uyarra et al. Citation2017). Following Lester and Piore (Citation2004), public officers’ essential tasks then become establishing contacts to interesting parties and initiating a conversation while contributing to it with novel ideas. Being relative lightweight to organize, innovation contests may promote conversations, especially between cities and startups (van Winden and Carvalho Citation2019). Cities have an opportunity to articulate their needs and wishes, and companies may showcase their abilities.

It has been argued that a majority of public procurements of innovation should focus on proximate policy goals instead of broader innovation policy goals (Uyarra and Flanagan Citation2010). For cities, this typically means prioritizing solutions that fulfil local needs. Facilitating interactions between local actors can benefit procurement by connecting people with different backgrounds and shaping interpretations of desired and feasible innovations (Edquist and Zabala-Iturriagagoitia Citation2012; Rutten Citation2017). Being more exciting and less bureaucratic than traditional procurement (cf. van Winden and Carvalho Citation2019), innovation contests may be useful by acquiring new perspectives to local problems. Consequently, contests may have lasting benefits, even if their direct outcomes are often modest (Carr and Lassiter Citation2017; Johnson and Robinson Citation2014; van Winden and Carvalho Citation2019).

Suppose innovation contests stress conversations over solving individual tasks. In that case, some of the organizing principles should be re-evaluated. Let us first consider the structure of a contest. To ensure connections to the participants, the city cannot outsource interactions with them to intermediaries. In the Junction hackathon, interactions between the end-users and the participants were limited, and the contestants’ profiles did not match the city’s needs. The lack of social and spatial embeddedness restricted the outcomes to internal learning in lieu of generating lasting relationships and interactive learning, which are known to facilitate public procurement of innovation (Edquist and Zabala-Iturriagagoitia Citation2012). Moreover, in Enlighten Tampere, the winning solution had connections to multiple stakeholders within the city and strengthened their collaboration. Therefore, the hackathon facilitated also internal conversations among different groups with various interests, which has been recognized as a critical factor in taking advantage of emergent regional development paths (Sotarauta and Mustikkamäki Citation2012). Concerning size, whereas massive competitions with rewards in millions may be required for solving complex technological challenges (Adler Citation2011), smaller hackathons may help solve more straightforward and local problems (cf. van Winden and Carvalho Citation2019).

Related to defining the problem statement, we identified how multiple interests influenced the contests’ goals and expectations at different organizational levels. The contests integrated the goals of multiple development projects and the city’s strategic goals, which had different emphases. This multitude of secondary goals associated with innovation contests reflects the general trend of viewing public procurement as a strategic innovation policy tool (Edquist and Zabala-Iturriagagoitia Citation2012; Uyarra et al. Citation2020). It, however, clashes with the best practices of innovation contest design. It is argued that, in a contest, the problem statement should be crystal clear (Adamczyk, Bullinger, and Möslein Citation2012; Carr and Lassiter Citation2017; Mergel and Desouza Citation2013; Spradlin Citation2012), and that in the case of multiple goals, a contest should be split into a multitude of individual goals to ensure that the problems are sufficiently self-explanatory and straightforward (Blohm et al. Citation2018). Merging multiple distinct goals is likely to reduce the clarity of the problem statement and the contest's effectiveness in generating suitable solutions.

Our study produced a more nuanced understanding of the upsides and downsides of multiple goals. The findings support the concern that integrating multiple goals in a single contest may reduce its clarity as the contestants have less concrete ideas of what is expected of them. In both contests, the problem statements were defined at a relatively abstract level, which gives plenty of room for proposing innovative solutions but offers little guidance to specific directions for developing solutions. The findings suggest that this difficulty may be mitigated by ensuring effective interaction between the contestants and the organizers during the contest. Communication with the organizers enabled the gradual clarification of the problem during the process. In Junction, the organizers included even more people in the design phase to ensure the submissions’ relevance and the end-users’ commitment to implementing the solutions. Including more viewpoints may be a risk in terms of clarity but help contestants understand the city’s needs and improve the organizer’s ability to put the ideas that they receive into practice. Hence, there may exist a trade-off between clarity and implementability in innovation contests determined by the number of distinct viewpoints involved in contest design: acknowledging multiple viewpoints may help manage implementation-related risks but harm clarity. Furthermore, difficulties may arise if end-users are not involved throughout the process as project officers may lack the ability to engage in in-depth conversations as happened in Junction. This may harm the adaptation of participants’ solutions to local needs (Uyarra and Flanagan Citation2010), the selection of the best solutions (as in Junction), and the broader adoption of the solutions within the city (van Winden and Carvalho Citation2019).

Regarding motivation, previous studies emphasize the importance of identifying desired participants and understanding their incentives comprehensively (Liotard and Revest Citation2018; Mergel and Desouza Citation2013). Our findings support this notion. The Junction case provides an illustrative example of how poor knowledge of potential participants’ profiles and restrictions may lead to a lack of interest in participating. Sometimes, especially when seeking more ambitious innovations, it may be beneficial to attract large and diverse crowds (Dahlander, Jeppesen, and Piezunka Citation2019). However, given the difficulties of solving large challenges with small-scale contests (van Winden and Carvalho Citation2019) and the fact that conversations often benefit from being connected to a place (Uyarra et al. Citation2017), it may be both efficient and feasible to target a defined set of actors. Local actors should be considered because they may be straightforward to identify, more receptive to reputational incentives, and easier to develop long-term relationships with, instead of one-off discussions (van Winden and Carvalho Citation2019).

Conclusions

In contrast to the typical view of innovation contests where the seekers and solvers operate separately, our findings suggest that cities may benefit from hackathons by engaging in conversations with participants: interactive processes to facilitate mutual learning and rich alignment of views of people with different perspectives. Hackathons may bring together actors for developing an understanding of local problems and potential solutions. This differs from contests that strictly prioritize the identification of new developers and technologies.

This research has some implications for practice. While we do not dispute the value of existing insights on the efficient design of innovation contests (Adamczyk, Bullinger, and Möslein Citation2012; Dahlander and Piezunka Citation2014; Desouza Citation2012), we emphasize that if secondary goals such as networking and brand benefits are considered important, special attention should be paid to interactions during the contests, the involvement of relevant viewpoints from the city organization, and acknowledging incentives other than monetary rewards. In such cases, a contest's success cannot be evaluated merely based on acquiring new ideas or innovations. Instead, more comprehensive benefits that may emerge over long periods of time need to be assessed.

Our study suggests value in involving various internal stakeholders in hackathons. We consider investigating the dynamics between temporary development projects and the broader city organization an exciting avenue for future research. On the one hand, there is the challenge of ensuring that the contests have a lasting impact. On the other hand, there lies an interest in examining how contests may facilitate cross-functional thinking and collaboration (Athanasaw Citation2003; Sotarauta and Mustikkamäki Citation2012).

While our study is limited by its empirical focus on smart city hackathons, we see a potential for examining how contextual factors such as a contest’s domain and size influence its organization. Overall, the literature on innovation contests is scarce and scattered, and there is a need to combine insights from crowdsourcing, hackathons, public procurement, regional policy, and innovation policy, to understand their potential and organization. We have taken a step in this direction, but more work is needed to understand the transferability of the findings from one context to another. We also welcome quantitative assessments of the relationships between contests’ elements such as their structure, problem statement, and means to motivate participants, and their outcomes. In our study, we touched upon the participant’s subjective motivations to participate in the contests. However, our data in this respect is limited: while we interviewed all key organizers, we did not extensively investigate the participants’ viewpoints. As there is little experience in organizing innovation contests, we consider it important to give voice to the participants’ experiences. Here, innovation contest researchers could learn from studies on crowdsourcing (e.g. Acar Citation2019; Zheng, Li, and Hou Citation2011).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Acar, O. A. 2019. “Motivations and Solution Appropriateness in Crowdsourcing Challenges for Innovation.” Research Policy 48 (8): 103716. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2018.11.010.

- Adamczyk, S., A. C. Bullinger, and K. M. Möslein. 2012. “Innovation Contests: A Review, Classification and Outlook.” Creativity & Innovation Management 21 (4): 335–360. doi:10.1111/caim.12003.

- Adler, J. H. 2011. “Eyes on a Climate Prize: Rewarding Energy Innovation to Achieve Climate Stabilization.” Harvard Environmental Law Review 35 (1). doi:10.2139/ssrn.1576699.

- Albino, V., U. Berardi, and R. M. Dangelico. 2015. “Smart Cities: Definitions, Dimensions, Performance, and Initiatives.” Journal of Urban Technology 22 (1): 3–21. doi:10.1080/10630732.2014.942092.

- Alhola, K., and A. Nissinen. 2018. “Integrating Cleantech Into Innovative Public Procurement Process – Evidence and Success Factors.” Journal of Public Procurement 18 (4): 336–354. doi:10.1108/JOPP-11-2018-020.

- Almirall, E., M. Lee, and A. Majchrzak. 2014. “Open Innovation Requires Integrated Competition-Community Ecosystems: Lessons Learned from Civic Open Innovation.” Business Horizons 57: 391–400. doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2013.12.009.

- Athanasaw, Y. A. 2003. “Team Characteristics and Team Member Knowledge, Skills, and Ability Relationships to the Effectiveness of Cross-Functional Teams in the Public Sector.” International Journal of Public Administration 26 (10–11): 1165–1203. doi:10.1081/PAD-120019926.

- Bleda, M., and J. Chicot. 2020. “The Role of Public Procurement in the Formation of Markets for Innovation.” Journal of Business Research 107: 186–196. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.11.032.

- Blohm, I., S. Zogaj, U. Bretschneider, and J. M. Leimeister. 2018. “How to Manage Crowdsourcing Platforms Effectively?” California Management Review 60 (2): 122–149. doi:10.1177/0008125617738255.

- Briscoe, G., and C. Mulligan. 2014. Digital Innovation: The Hackathon Phenomenon (CREATIVEWORKS LONDON WORKING PAPER NO.6).

- Caragliu, A., C. Del Bo, and P. Nijkamp. 2011. “Smart Cities in Europe.” Journal of Urban Technology 18 (2): 65–82. doi:10.1080/10630732.2011.601117.

- Carbonara, N., and R. Pellegrino. 2018. “Fostering Innovation in Public Procurement Through Public Private Partnerships.” Journal of Public Procurement 18 (3): 257–280. doi:10.1108/JOPP-09-2018-016.

- Carr, S. J., and A. Lassiter. 2017. “Big Data, Small Apps: Premises and Products of the Civic Hackathon.” In Seeing Cities Through Big Data, edited by P. (Vonu) Thakuriah, N. Tilahun, and M. Zellner, 543–559. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-40902-3_29

- Dahlander, L., L. B. Jeppesen, and H. Piezunka. 2019. “How Organizations Manage Crowds: Define, Broadcast, Attract, and Select.” In Managing Inter-Organizational Collaborations: Process Views (Research in the Sociology of Organizations, Vol. 64), edited by J. Sydow, and H. Berends, 239–270. doi:10.1108/S0733-558X20190000064016

- Dahlander, L., and H. Piezunka. 2014. “Open to Suggestions: How Organizations Elicit Suggestions Through Proactive and Reactive Attention.” Research Policy 43 (5): 812–827. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2013.06.006.

- Davis, J. R., E. E. Richard, and K. E. Keeton. 2015. “Open Innovation at NASA: A new Business Model for Advancing Human Health and Performance Innovations.” Research Technology Management 58 (3): 52–58. doi:10.5437/08956308X5803325.

- Desouza, K. C. 2012. Challenge.gov: Using Competitions and Awards to Spur Innovation. http://www.businessofgovernment.org/report/challengegov-using-competitions-and-awards-spur-innovation

- Edler, J., and L. Georghiou. 2007. “Public Procurement and Innovation-Resurrecting the Demand Side.” Research Policy 36: 949–963. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2007.03.003.

- Edquist, C., N. Vonortas, and J. Zabala-Iturriagagoitia. 2015. “Introduction.” In Public Procurement for Innovation, edited by C. Edquist, N. S. Vonortas, J. M. Zabala-Iturriagagoitia, and J. Edler, 1–34. Edward Elgar Publishing. doi:10.4337/9781783471898.00006

- Edquist, C., and J. M. Zabala-Iturriagagoitia. 2012. “Public Procurement for Innovation as Mission-Oriented Innovation Policy.” Research Policy 41 (10): 1757–1769. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2012.04.022.

- Edquist, C., and J. M. Zabala-Iturriagagoitia. 2015. Pre-commercial procurement: A demand or supply policy instrument in relation to innovation? R & D Management. doi:10.1111/radm.12057

- European Commission. 2011. Open data an engine for innovation, growth and transparent governance. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2011:0882:FIN:EN:PDF

- European Commission. 2018. Public Procurement of Innovative Solutions: Shaping Europe’s digital future. https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/public-procurement-innovative-solutions

- Ford, R. C., B. Richard, and M. P. Ciuchta. 2015. “Crowdsourcing: A new way of Employing non-Employees?” Business Horizons 58: 377–388. doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2015.03.003.

- Georghiou, L., J. Edler, E. Uyarra, and J. Yeow. 2014. “Policy Instruments for Public Procurement of Innovation: Choice, Design and Assessment.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 86: 1–12. doi:10.1016/J.TECHFORE.2013.09.018.

- Gillier, T., C. Chaffois, M. Belkhouja, Y. Roth, and B. L. Bayus. 2018. “The Effects of Task Instructions in Crowdsourcing Innovative Ideas.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 13: 34–44. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2018.05.005.

- Hartmann, S., A. Mainka, and W. Stock. 2016. “Opportunities and Challenges for Civic Engagement: A Global Investigation of Innovation Competitions.” International Journal of Knowledge Society Research 7 (3), doi:10.4018/IJKSR.2016070101.

- Howe, J. 2008. Crowdsourcing : how the Power of the Crowd is Driving the Future of Business. London: Random House Business.

- Johnson, P., and P. Robinson. 2014. “Civic Hackathons: Innovation, Procurement, or Civic Engagement?” Review of Policy Research 31 (4): 349–357. doi:10.1111/ropr.12074.

- Karjalainen, K., and K. Kemppainen. 2008. “The Involvement of Small- and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Public Procurement: Impact of Resource Perceptions, Electronic Systems and Enterprise Size.” Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management 14 (4): 230–240. doi:10.1016/j.pursup.2008.08.003.

- Kay, L. 2012. “Opportunities and Challenges in the Use of Innovation Prizes as a Government Policy Instrument.” Minerva 50: 191–196. doi:10.1007/s11024-012-9198-2.

- Lember, V., T. Kalvet, and R. Kattel. 2011. “Urban Competitiveness and Public Procurement for Innovation.” Urban Studies 48 (7): 1373–1395. doi:10.1177/0042098010374512.

- Lester, R. K., and M. J. Piore. 2004. Innovation – The Missing Dimension. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Liotard, I., and V. Revest. 2018. “Contests as Innovation Policy Instruments: Lessons from the US Federal Agencies’ Experience.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 127: 57–69. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2017.07.008.

- Loader, K. 2015. “SME Suppliers and the Challenge of Public Procurement: Evidence Revealed by a UK Government Online Feedback Facility.” Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management 21 (2): 103–112. doi:10.1016/j.pursup.2014.12.003.

- Makkonen, T., M. Merisalo, and T. Inkinen. 2018. “Containers, Facilitators, Innovators? The Role of Cities and City Employees in Innovation Activities.” European Urban and Regional Studies 25 (1): 106–118. doi:10.1177/0969776417691565.

- Masters, W. A., and B. Delbecq. 2008. Accelerating Innovation with Prize Rewards: History and Typology of Technology Prizes and a New Contest Design for Innovation in African Agriculture. In International Food Policy Research Institute.

- Mazzucato, M. 2018. “Mission-oriented Innovation Policies: Challenges and Opportunities.” Industrial and Corporate Change 27 (5): 803–815. doi:10.1093/icc/dty034.

- Mergel, I., and K. C. Desouza. 2013. “Implementing Open Innovation in the Public Sector: The Case of Challenge.gov.” Public Administration Review 73 (6): 882–890. doi:10.1111/puar.12141.

- Miles, M., M. Huberman, and J. Saldaña. 2014. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Obwegeser, N., and S. Müller. 2018. “Innovation and Public Procurement: Terminology, Concepts, and Applications.” Technovation 74–75: 1–17. doi:10.1016/j.technovation.2018.02.015.

- O’Mahony, S., and B. A. Bechky. 2008. “Boundary Organizations: Enabling Collaboration among Unexpected Allies.” Administrative Science Quarterly 53 (3): 422–459. doi:10.2189/asqu.53.3.422.

- Rutten, R. 2017. “Beyond Proximities: The Socio-Spatial Dynamics of Knowledge Creation.” Progress in Human Geography 41 (2): 159–177. doi:10.1177/0309132516629003.

- Schot, J., and W. E. Steinmueller. 2018. Three frames for innovation policy: R&D, systems of innovation and transformative change. Research Policy. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2018.08.011

- Scotchmer, S. 2004. Innovation and Incentives. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Sotarauta, M. 2005. “Shared Leadership and Dynamic Capabilities in Regional Development.” In Regionalism Contested: Institution, Society and Governance, edited by I. Sagan, and H. Halkier, 53–72. New York: Ashgate.

- Sotarauta, M. 2009. “Power and Influence Tactics in the Promotion of Regional Development: An Empirical Analysis of the Work of Finnish Regional Development Officers.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 40 (5): 895–905. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2009.06.005.

- Sotarauta, M., and N. Mustikkamäki. 2012. “Strategic Leadership Relay: How to Keep Regional Innovation Journeys in Motion?” In Leadership and Change in Sustainable Regional Development, edited by M. Sotarauta, I. Horlings, and J. Liddle. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203107058

- Spradlin, D. 2012. “Are you Solving the Right Problem?” Harvard Business Review 90 (9): 85–93.

- Stine, D. 2009. Federally funded innovation inducement prizes.

- Terwiesch, C., and K. T. Ulrich. 2009. Innovation Tournaments: Creating and Selecting Exceptional Opportunities. Boston: Harvard Business Press.

- Timmermans, B., and J. M. Zabala-Iturriagagoitia. 2013. “Coordinated Unbundling: A way to Stimulate Entrepreneurship Through Public Procurement for Innovation.” Science and Public Policy 40 (5): 674–685. doi:10.1093/scipol/sct023.

- Tjornbo, O., and F. R. Westley. 2012. “Game Changers: The Big Green Challenge and the Role of Challenge Grants in Social Innovation.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 3 (2): 166–183. doi:10.1080/19420676.2012.726007.

- Torvinen, H., and P. Ulkuniemi. 2016. “End-user Engagement Within Innovative Public Procurement Practices: A Case Study on Public–Private Partnership Procurement.” Industrial Marketing Management 58: 58–68. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2016.05.015.

- Uyarra, E., J. Edler, J. Garcia-Estevez, L. Georghiou, and J. Yeow. 2014. “Barriers to Innovation Through Public Procurement: A Supplier Perspective.” Technovation 34 (10): 631–645. doi:10.1016/j.technovation.2014.04.003.

- Uyarra, E., and K. Flanagan. 2010. “Understanding the Innovation Impacts of Public Procurement.” European Planning Studies 18 (1): 123–143. doi:10.1080/09654310903343567.

- Uyarra, E., K. Flanagan, E. Magro, and J. M. Zabala-Iturriagagoitia. 2017. “Anchoring the Innovation Impacts of Public Procurement to Place: The Role of Conversations.” Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 35 (5): 828–848. doi:10.1177/2399654417694620.

- Uyarra, E., J. M. Zabala-Iturriagagoitia, K. Flanagan, and E. Magro. 2020. “Public Procurement, Innovation and Industrial Policy: Rationales, Roles, Capabilities and Implementation.” Research Policy 49 (1): 103844. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2019.103844.

- van Winden, W., and L. Carvalho. 2019. “Intermediation in Public Procurement of Innovation: How Amsterdam’s Startup-in-Residence Programme Connects Startups to Urban Challenges.” Research Policy 48 (9): 103789. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2019.04.013.

- Vehviläinen, M. 2019. D3.2 Report of tendering and procurement processes. STARDUST project deliverable.

- Vilhula, A., and M. Vehviläinen. 2020. D3.4 Hackathon - STARDUST challenge - results and the implementation report. STARDUST project deliverable.

- Williams, H. 2012. “Innovation Inducement Prizes: Connecting Research to Policy.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. doi:10.1002/pam.21638.

- Zheng, H., D. Li, and W. Hou. 2011. “Task Design, Motivation, and Participation in Crowdsourcing Contests.” International Journal of Electronic Commerce 15 (4): 57–88. doi:10.2753/JEC1086-4415150402.