ABSTRACT

Regions are often viewed like businesses that compete with each other for people, investments and jobs. Private-sector instruments are being adopted in this context without providing evidence for positive management outcomes and clarifying the conditions under which their application is meaningful. Against this background, the German Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture (BMEL) tested three instruments as part of a pilot programme: the selection of regions eligible for financial assistance through a competitive process, management based on quantifiable targets and the comprehensive decentralization of decision-making, including the administration of those funds that BMEL allocated to the regions. Based on 124 interviews, 61 participant observations and documentary research, we contribute to the literature on rural governance and entrepreneurial regions in showing that these instruments are less effective, efficient and legitimate than New Public Management theory purports. We argue that these deficits do not result essentially from an inappropriate use of the instruments as often proposed but from general problems associated with actor constellations, institutions and the policy context. Therefore, we suggest not to use the instruments tested and recommend instruments focusing on regional needs, mutual learning and democratically legitimized institutions.

1. Introduction

Rural development has shifted from a sectoral to a territorial and local approach. This change has been taking place during a time period in which our understanding of the role of the state – the private sector now being seen as the model for government, has been transformed as well (Cox Citation1993; Duckworth, Simmons, and McNulty Citation1986; Harvey Citation1989). With the new rural paradigm, the OECD and the EU have contributed to expanding the use of private-sector management instruments. Of central importance is the orientation towards competition, management by objectives (MBO) and decentralization. Elements of this management approach are, for example, part of the LEADER initiative of the EU (Bosworth et al. Citation2016; Marquardt et al. Citation2012), and an intensified use is proposed by the OECD (Citation2019) as well as expected for the coming period of European Structural and Investment Funds (Bachtler and Begg Citation2018).

Under the buzzword New Public Management (NPM), the management instruments that have been adopted from the private sector by public administration have been the focus of academic discussion during recent decades (Bevir Citation2011). Relevant instruments such as the allocation of financial assistance through competitions, contracts, MBO and evaluations are often part of current governance processes to regenerate urban and rural areas (Newman Citation2001; Powell and Exworthy Citation2002; Pugalis Citation2013). Despite the fact that NPM instruments are often criticized and their downsides is known, many elements of NPM do play a central role in rural development policies. For example, the Implementation Regulation 808/2014 for the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD) demands detailed and quantifiable target indicators of performance measurement. The introduction of private-sector instruments is, however, a result of a discontent with traditionally hierarchical, bureaucratic and politically influenced procedures. This is partly because results of traditional structural policies are often unverifiable (Bachtler and Ferry Citation2013), for instance, due to deadweight effects or diffuse and conflicting goals, and political lock-ins were suspected (Grabher Citation1993; Rehfeld and Terstriep Citation2019). Partly, the new instruments have been adopted from the private sector – reflecting the spirit of the age – often without analysing the extent to which the necessary prerequisites for proper functioning exist within the new context beforehand.

Therefore, the research question arises how and why private-sector management instruments are effective, efficient and legitimate for developing rural regions. The discussion about NPM emphasizes the effectiveness and efficiency of new management instruments, which is reflected in such justifications for introducing them as ‘value for money’ and ‘doing more with less’ (Pugalis Citation2013, 619 f.). Besides effectiveness and efficiency, the question of legitimacy plays an increasing role in governance research as well (Levelt and Metze Citation2014; Voets and Van Dooren Citation2011). Based on empirical results from a pilot programme in Germany, we argue that management instruments such as competition, MBO and comprehensive decentralization do not lend themselves to regenerating rural areas. This is due to the fact that the application of management instruments faces obstacles such as interest coalitions and institutions, and, furthermore, that regions unlike companies are not organizations with coherent goals and hierarchies. In the next section, we review the literature to show rival propositions and need for research. Then, we present our empirical case and the methods applied, followed by the results. Subsequently, we discuss our findings and conclude with policy recommendations.

2. The entrepreneurial region

The discourse about entrepreneurial cities since the 1980s (Cox Citation1993; Duckworth, Simmons, and McNulty Citation1986; Harvey Citation1989; Jessop Citation1997) has led to the notion of viewing spaces as businesses that compete with each other for investments, jobs, highly skilled labour, tourists and shoppers. Cities and regions, so the argument goes, ought to be managed and governed like corporations. This also involved a shift of governance away from traditional public administration to the adoption of new types of management instruments. Under the name of NPM, these instruments were borrowed from the supposedly cutting-edge private sector and applied to managing the development of rural areas. For example, management instruments, such as SWOT analysis, vision statements, target setting, lists of measures and evaluations (Bryson and Roering Citation1987), have been borrowed for the LEADER approach, which has been used across Europe for decades now. The following sections outline the arguments in the literature for and against the management instruments competition, MBO and decentralization as well as the causal mechanisms generally in the public sector and specifically in spatial development policy. Finally, we sum up the rival propositions in clarifying the need for research.

2.1 Competitions

A central conclusion in multi-level governance research is that network negotiations across different levels rather block innovations (Scharpf Citation2010). In contrast, the economic theory of federalism maintains that competition between jurisdictions creates opportunities to experiment with new policies and policy diffusion to win over or retain mobile tax payers (Qian and Weingast Citation1997; Tiebout Citation1956). While competition has been widely used in the United Kingdom since the 1970s (Woods, Edwards, and Anderson Citation2007), for example, it is less established in Germany (Fürst Citation2006). Here, the intended goal is not so much to reward achieved results but to select and support promising strategies and proposals (Benz Citation2012; Rehfeld and Terstriep Citation2019).

In institutional economics, the rationale for competitions is the exploration of solutions for principal-agent issues (Powell and Exworthy Citation2002). In this view, the principal should establish a (quasi-)market to have agents compete for a contract with the principal. Competition between local partnerships is supposed to stimulate innovations, increase effectiveness and improve the efficient use of resources (Lowndes and Skelcher Citation1998). For the government to function, it must rely on the voluntary cooperation of local actors (Fürst Citation2006). Competition is, therefore, important to mobilize local actors at the time when proposals are submitted and funding is applied for. Benz (Citation2012) adds that competition limits the role important politicians and upper-level administrators play in the decision-making process. By contrast, actors on the network periphery profit because success in the competition demands participation of experts and lower-level civil servants, small businesses, civil society organizations and groups that represent social interests often insufficiently organized.

Other authors treat competition in a more critical manner. Jones and Little (Citation2000), for example, argue that only public actors, particularly in rural areas, possess the necessary resources to successfully participate in competitions. Small companies and civil society organizations typically lack the necessary familiarity with local and national politics; the economic, technical and legal knowledge; as well as the option of allocating staff hours to projects of this kind. As the result, these actors are not regarded as equal partners and are just being checked off on the competition participants list. Competition proposals are often also prepared under extreme time pressure. Because of an uncertain chance of success, the available resources for preparing proposals are limited, with the result that applications are either novel or viable (Küpper et al. Citation2018). Competition entries are not based on local demand but on the likelihood of being selected, why thematically open competitions are perceived as more suitable in initiating innovations (Kiese and Kahl Citation2017). Once selected, incomplete proposals lead to conflicts about what actually needs to be done and how funds will be allocated. As the result, there is a contradiction between the allocation of funds through competitions and the creation of enduring local partnerships (Jones and Little Citation2000; Newman Citation2001).

Lowndes and Skelcher (Citation1998) associate inefficiency and unfairness with competitions – all participants have to pay the application costs, but only a few are selected. The allocation of funds does not follow actual demand, but is based on the entrepreneurial ability of local actors to shape their application in such a way so as to reflect the preferences of the competition organizers. This leads to path dependencies because the winners acquire organizational capabilities and absorptive capacities (Kiese and Kahl Citation2017) that put them in a more advantageous position during the next round of the competition (Woods, Edwards, and Anderson Citation2007). Fürst (Citation2006) questions also the innovative nature of competitions. In addition to routines that are difficult to alter, those who will potentially lose because of changes will fight the new ideas. One strategy is paying lip service to supporting innovative strategies without allocating any resources for implementation. This could lead to regions receiving funding after successfully participating in a competition and using the funding for already planned but less innovative projects.

2.2 Management by objectives

MBO was adopted from business administration with the intention to improve coordination within an organization. Drucker (Citation1954) concluded this approach from the insight that managers do not automatically follow company objectives. Following this approach, managers should set their own objectives. Upper-level management, however, needs to either approve or reject these objectives. Every manager should also be part of the goal-setting process of the higher-level unit because mutual understanding across various levels can only be created from the ground up, not from the top down. Goal setting is supposed to lead to self-regulation and not to a command and control situation which would defeat the intended purpose (Drucker Citation1954). Every manager needs to gauge their level of goal achievement to be able to adjust their course of action. The results, however, are not to be submitted to the next higher level because this would lead to progress being measured by indicators only. MBO ought to minimize the level of control by having managers monitor themselves. Evidence shows that MBO also results in productivity gains in public organizations, whereas the effect depends on the top-management commitment to the reform (Rodgers and Hunter Citation1992).

Starting out as a bottom-up instrument, MBO has been used, however, mostly in a top-down manner to push through upper-management objectives which was also observed with NPM in the public sector (Osborne Citation2006; Powell and Exworthy Citation2002). This can be explained by keeping in mind that NPM derives not only from management theories but also from the new institutional economics (Hood Citation1991). Institutional economics emphasizes the need to create incentive and sanctioning mechanisms to align the interests of the agents with the goals of the principal. Informational asymmetry needs to be dissolved by including in contract management clear operational objectives, a regular reporting system and controlling mechanisms (OECD Citation2007). Work becomes more predictable once a contractual agreement specifies previously vague goals, sanctions and compensation, and provides protection in case a partner does not deliver agreed-upon results or trust is destroyed.

In the United Kingdom, for example, New Labour introduced many local partnerships and, at the same time, pushed through a change towards evidence-based policy-making (Pugalis Citation2013; Rummery Citation2002). This meant that only those policies that were quantifiable and verifiable were considered successful. Partnerships try to minimize the risk of failure by setting less ambitious goals and aiming for quantifiable outputs which are important for lobbying and public relations work (Pugalis Citation2013). An externally commissioned evaluation undermines the necessary steps of reflecting and adjusting that are the basis for success (Bosworth et al. Citation2016).

This type of target control indicates the national government’s lack of trust in local partnerships. Because the goals of the partnerships are typically determined by the national government, member organizations on the ground do not enjoy much strategic scope (Rummery Citation2002). This would be necessary, however, to ensure that the partnership operates successfully and sustain its work.

2.3 Decentralization

In the wake of an intensifying global competition with cycles of innovation getting shorter since at the least the 1990s, companies have reintegrated planning and implementation to be able to react flexibly to volatile markets. At the same time, the organizational structure of companies underwent a transformation by shifting responsibilities downward to those with experience in the day-to-day production process and to include them in the planning process – they are most familiar with the issues, potential solutions and are in the position to evaluate potential outcomes. In this context, there was also a call for public administration to adopt decentralized organizational forms from the private sector (OECD Citation2007; Sabel Citation1995). Decentralization is certainly not only proposed to copy private-sector models (Rehfeld and Terstriep Citation2019; Gherhes, Brooks, and Vorley Citation2020). However, decentralization forms an important part of NPM (Hood Citation1991; Sager and Sørensen Citation2011).

The expected benefits of a decentralized public sector include better democratic control, improved horizontal coordination and a broader focus on local issues and the needs of constituents. Hence, Eiser (Citation2020) shows for decentralized fiscal policy positive effects for tailored policies and innovation. Additionally, he detects higher accountability although increasing complexity hampers this effect. The drawbacks, however, include reduced vertical coordination, lower advantages through specialization, smaller economies of scale and intensified heterogeneity between regions leading to a greater territorial inequality. Ebinger, Grohs, and Reiter (Citation2011) detect only few positive effects of administrative decentralization and observe, instead, serious problems.

Decentralization plays also a central role in policies of regenerating cities and regions. By using local partnerships, national governments anticipate a more comprehensive policy, reduce transaction costs and achieve better policy outcomes due to the contribution of many actors from various sectors. Other anticipated outcomes include innovative approaches because of the bringing together of knowledge from different partners, and an increase in financial resources due to the involvement of private and non-profit organizations (Clarke and Glendinning Citation2002; Newman Citation2001).

Bureaucracy and financing terms, however, limit local decision-making scope. This raises the question to what extent government assistance for partnerships really leads to a decentralization of the power of the state or, instead is just a new technique for manipulating and controlling local actors (Bailey and Pill Citation2015; Gherhes, Brooks, and Vorley Citation2020). This indicates a transformation of governmentality with the intention to engage social actors away from political institutions, but also to tap those actors’ autonomy to achieve government objectives (Edwards et al. Citation2001, 306; Swyngedouw Citation2005). For Davies (Citation2002), supra-local requirements undermine local autonomy, discourage local actors and overburden them with a multitude of partnership initiatives. This leads to symbolic partnerships not supported by local resources, and the use of similar strategies and organizational structures no matter the location.

Local actors typically use their scope of action to achieve their own goals (Bosworth et al. Citation2016; Edwards et al. Citation2001). By using its mechanisms of power, the state can, however, reign in partnerships in case its key interests are at risk. Current decentralization approaches reflect the fact that the state determines the conditions, functioning and financing of partnerships as well as the spatial scale on which local actors have to cooperate.

2.4 Summary of rival propositions

Although private-sector management instruments are widely used for decades, the literature shows plausible rival propositions and thus need for research. summarizes the arguments supporting increased effectiveness, efficiency and legitimacy compared to traditional hierarchical instruments. Conflicting arguments challenge these assumptions and propose negative effects. This is firstly due to unintended consequences, which cancel out the positive results, like intensified disparities among regions through competition, the focus on quantifiable results in MBO or lacking economies of scale in decentralization. Negative effects may result secondly from an inadequate application such as unfair competitions, top-down MBO or conditioned regional autonomy.

Table 1. Pros and cons of competition, MBO and decentralization for effectivity, efficiency and legitimacy from the literature.

3. Case study of a pilot programme to develop peripheral rural regions

3.1 Case description

Rural development policies in Germany are, in spatial terms, relatively indiscriminate policies in that they propose the same measures in all rural areas, while providing only a certain degree of scope for setting priorities on the local level. Since rural areas in Germany develop in very different ways, the BMEL implemented a pilot programme that focused on the development of peripheral rural areas. Its goal was to identify and test new ways for supporting these areas. The BMEL adopted its management approach to a large extent from private-sector models following recommendations from a consulting firm. The intention was to use the pilot programme to test the management instruments competition, MBO and decentralization.

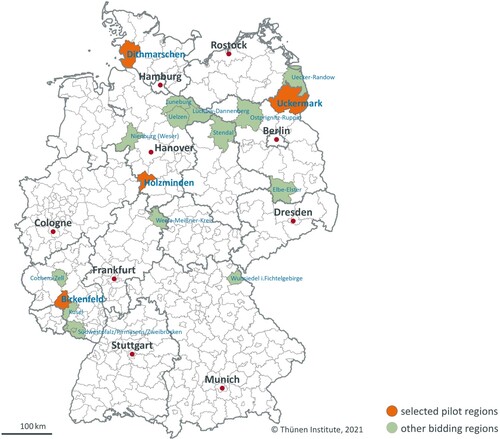

From 2011 to 2014, the BMEL implemented the pilot programme ‘RuralFuture’ (BMELV Citation2011). Based on socio-economic and spatial indicators, 17 counties were selected (Margarian and Küpper Citation2011) and invited to prepare their applications for the coming funding period as part of a competition. This application period lasted from September 2011 to February 2012. The counties received up to 30,000 euros each to pay for external expenditures such as consulting and analysis. In March 2012, a selection committee consisting of representatives from various federal ministries, the scientific community and interest groups selected four pilot regions that subsequently received 1.8 million euros each to implement their plans during the funding period from April 2012 to the end of 2014 ().

The BMEL designed the call for proposals in an intentionally open-ended way (BMELV Citation2011, 8). Local representatives were asked instead to outline their own strategic goals and quantified operational targets, local organizational structure and efforts to invite entrepreneurial individuals to the programme. The BMEL intended to delegate a large portion of the decision-making to the local level. The decision to have a regional partnership of public and private-sector actors selecting the projects to be funded was just one of them. Other decisions included the independent local administration and control of the available budget and the evaluation of achieved objectives. The BMEL requested evaluation reports to be submitted every year as the basis for adjusting the goals of the regions. This decentralization approach, particularly the autonomous administration of regional budgets, goes beyond regular programmes for regional development in Germany and other countries (Davies Citation2002, Citation2004; Rummery Citation2002; Shucksmith Citation2010; exceptionally in other pilot programmes similar budgets were tested: e.g. Elbe Citation2011). Consequently, the BMEL was hoping that its management approach would focus on the actual needs on the ground, test innovative strategies, ensure a high level of motivation on the part of the actors involved and support the creation of self-help competencies and capacities throughout the peripheral regions.

This pilot programme perfectly lends itself to analysing the employed management instruments because those in charge of the programme attempted to avoid those mistakes that often lead to criticisms of the instruments. Therefore, because the organizers of the competition tried to avoid amplifying regional differences, only peripheral rural regions were invited and each of them received the same amount of 30,000 euros to develop their proposals. The funding agency did not impose goals that needed to be achieved, instead, regional actors were given discretion to determine the strategic goals they wanted to pursue and to set the operational objectives to implement them. Finally, the decision-making process was largely decentralized to the fullest extent permitted by law, which included financial management of the pilot programme and budgetary discretion on the part of the regional actors. This approach prevented the federal government from rejecting projects because of content or financing.

We present empirical results from research accompanying the pilot programme. For the competition, we researched the 17 bidding regions, while we focus on the four selected pilot regions for our analysis of MBO and decentralization (). The four regions pursued very different strategies in different spatial contexts ().

Table 2. Basic information of the four pilot regions.

3.2 Methods

The empirical data were collected from 2012 to 2016. The study used qualitative methods because of the complexity of the processes, the comprehensive perspective and the difficulties in quantifying the various impacts and drivers. In the light of this, various sources were brought together to capture mechanisms in a comprehensive manner.

Before the four pilot regions were selected, we conducted two semi-structured interviews in each of the 17 regions with the consultant commissioned and the officer of county administration in charge. These interviews focused the perception of the competition and the effects on strategy development. At the beginning of the funding phase, 44 semi-structured interviews with regional representatives (members of the decision-making board, regional management and financial administration) were completed in the four pilot regions focusing on the implementation of MBO. Another 11 interviews were conducted with representatives from the federal (BMEL and consultant) and state levels (public officers accompanying the regional process) to analyse MBO and decentralization from the perspective of higher-level governments. At the end of the funding period, an additional 35 interviews were conducted with the key actors (the most important actors from the first round) and external observers (not directly involved LEADER-managers, local journalists and members of the county council) in the four pilot regions to collect the experiences with the management instruments and examine capacity building. An analysis of application documents, reports, project applications and reports, meeting minutes, etc. complemented the 124 interviews which lasted 1–2.5 h. The third research method consists of 61 participant observations, including observations of decision-making board meetings and working groups throughout the regions, interregional network events and telephone conferences during the entire duration of the pilot programme. Thereby, we were able to directly observe discussions and decisions in important arenas. Power constellations, arguments and interests witnessed were extremely instructive to complement the interviews which were influenced by social desirability, selective retention and ex-post rationalization.

To organize and interpret the huge material, we used the analytical strategy of examining plausible rival propositions (Yin Citation2014). Therefore, we compare the rival patterns about outcome and process in with our data from the case so that we can corroborate or falsify propositions or develop new hypotheses. We compose our results using cross-case syntheses for the three instruments. For each analytical category, we report the main findings in tables and illustrate the interpretation. We focus on what is supported from different regions, groups of actors and methods to ensure validity. Additionally, we also present fundamental discrepancies.

Based on the case description and the literature review, we can differentiate the analytical categories from further. Concerning the effectivity, we address the effects of the management instruments on the programme’s objectives. The competition should initiate innovative strategies in the participating regions and allow BMEL to select the best proposals. BMEL used MBO to improve the governance within the regions and among the different policy levels. Therefore, MBO should motivate relevant actors, make decision-making more goal-orientated, improves the coordination of different activities and enable controlling processes. Finally, BMEL pursued the goal of capacity building and regionally specific policies by using decentralization.

The efficiency of applying instruments is rarely evaluated because synergy effects are simply assumed, and costs and benefits are difficult to measure. With our methods, we are not able to quantify efficiency. We, however, contrast the governance outcomes with efforts needed to apply the management instruments. This includes not only tangible costs but also the time invested by those involved or side effects of the instruments. Resulting costs for the Ministry as well as for the participating regions are analysed because both perspectives are important and may differ significantly.

In contrast to the private sector, raising the question about the extent to which the employed instruments are legitimate is important because public funds are used. The literature review shows different ways of legitimation which can be systematized using a typology from policy research (Risse and Kleine Citation2007; Scharpf Citation2010). Input legitimacy signifies that people accept the mechanisms for their participation in the decision-making process. Based on the central components transparency and accountability, throughput legitimacy is concerned with the extent to which the mechanisms and processes of decision-making itself are accepted. Finally, output legitimacy is about accepting the outcomes of the decision-making process.

4. Applying private-sector instruments in practice

The results show empirical evidence describing occurrences relevant for assessing effectivity, efficiency and legitimacy as well as hypotheses about the causes for these observations. After presenting the findings for each instrument, we ask for the fundamental causes for overall outcomes.

4.1 Competition to develop and select innovative proposals

The experiences gained from implementing the pilot programme ‘RuralFuture’ () indicate that the competition was not very effective in developing innovative proposals in the participating regions and selecting the most promising ones for further funding. For example, the evidence shows that most strategies proposed were built on already existing projects in the regions. The reason was the comprehensive requirements of the BMEL for the documents submitted for competition. Seeing that BMEL considers a programme not using all the available funds a political failure, the BMEL emphasized in its requirements for the proposal preparation the fact that projects need to start shortly after being selected so that funds can be spent immediately. This in turn promotes strategies relying on existing projects and networks as the following quotation demonstrates:

And here it was really important for us that we propose projects that were worthy of its name, that could start with the implementation immediately or with a short warm-up time added. (…) What is directly connected is certainly the point that it is based on existing approaches. Sure! Since you only thereby achieve feasible projects in this short period of time. The actors – also related to that – have to be there, for the implementation too. (representative of a bidding region)

Table 3. Synopsis of the results concerning competition.

4.2 MBO for governing rural development

The effectiveness of the MBO instrument can be demonstrated by the fact that objectives motivate actors to act focused on regional priorities, serve as selection criteria, help coordinate various activities and allow for controlling. The results in indicate that MBO at the pilot programme hardly fulfilled any of the four functions. The reasons involve the restricted possibility and motivation to reach a consensus on a strategic focus and on SMART goals. Due to the meagre benefits, efficiency was rather low despite the fact that MBO did not cost much for both the national and the regional level.

Table 4. Synopsis of the results concerning MBO.

With only a few democratically elected actors being involved in designing and applying the target system, the input legitimacy of the management instrument was limited. As for throughput legitimacy, it was obvious that particularly the consulting firms used their discretion to conduct the pre-evaluation of project proposals and the goal achievement monitoring. Furthermore, additional criteria to selecting projects for funding were applied which made decisions less transparent. Thereby, the outflow of funds was the main underlying cause, as this citation suggests:

You could have said, we (…) also reject certain projects, because we say, they don‘t focus on strategic goal achievement exclusively. This is a process we couldn‘t stick to politically. If we for example had said, we wouldn’t have used 300.000 or 400.000 euro of the funds. But if you really look closely (…) what do I want to reach with this pilot programme here in the region, you would have implemented it in a different way. (representative of a pilot region)

4.3 Decentralization for addressing local needs and capacity building

There are mixed results for the effectiveness of decentralization (). The option of addressing regional needs directly was only partly used in practice. The strategy that was actually implemented largely depended on actors who were able to provide their own resources and who came with their own experience in applying for and implementing projects. In the Birkenfeld region, for example, an initial analysis had emphasized a lack of entrepreneurial spirit as the main regional problem. However, the largest part of the funding went to projects of the local university of applied sciences due to its extensive experience in obtaining third-party funding. Capacity building throughout the regions meant to a large extent acquiring and managing government funding. Only in the Holzminden region, the county administration used the pilot programme to specifically support a recently created tourism agency and to further the regional tourism strategy. Concerning the efficiency, the regions had to spend considerable resources because those in charge were inexperienced and very insecure about how to manage the financial aspects of the programme. An interviewee puts it as follows:

In order to become really good here [in the sourcing and application of funds], you need much experience and respective off-the-job training in these fields too. (…) Otherwise it actually doesn’t work out. Here, everything was learning by doing, because all of us didn’t have a clue about it. (representative of a pilot region)

Table 5. Synopsis of the results concerning decentralization.

4.4 Summary and main underlying causes

Overall, competition, MBO and decentralization was ineffective in ‘RuralFuture’ to achieve BMEL’s goals. Only Holzminden used somewhat of the potential of MBO and decentralization for steering and capacity building. Concerning efficiency, the instruments result in high costs for regions and BMEL compared to the instruments’ benefit, although costs for MBO are rather low and decentralization goes particularly at the expense of the regionally responsible actors. The analysis of legitimacy shows the strong influence of the administration and the consultants on participation and decision-making, whereas democratically elected politicians, newly involved experts or social interest groups remain weak. However, the legitimacy is only challenged if the output affects core interests of regional elites. To explain these results of the management instruments, we can identify three main underlying causes.

Firstly, the interest coalitions consist of the BMEL, regional actors and project sponsors and limit the proper functioning of private-sector instruments. The identified coalitions focus on applying for and making full use of the available funding, thereby agreeing to something to the detriment of an uninvolved third party – the tax payer. Therefore, BMEL focused on practicability in the organization of the competition. Regional actors chose strategies already planned or projects transferred from other regions, so that implementation was ensured. Nevertheless, these strategies were presented as innovative to meet selection committee’s expectations and make it difficult to select the best concepts, what in turn challenges the output legitimacy if regions were not selected for funding. Furthermore, the interest coalition lead to the missing commitment of BMEL and regional representatives to apply MBO. Subsequently, target values were easily adjusted, and regional representatives and BMEL both had no interest in investigating target control to detect measurement problems. MBO was thus used for public relations although the effect for output legitimacy was scarce since funds flow was the main indicator of success. Concerning decentralization, spending the funds was the lowest common denominator for cooperation throughout the regions. County administrations and consulting firms could refer to financial requirements to block critical discussions about project applications with low target contribution or exclude sceptical actors who did not belong to the established coalition from decision-making. In addition, financial administrations had no interest in an efficient assignment of funding or to test the compliance of their application because clawback actions would have reduced the money spent.

Secondly, the institutional framework interferes with private-sector instruments. By German constitution, the states are in charge of the implementation of rural development policy and federal government can only conduct pilot projects. Therefore, BMEL lacks administrative capacities, political assertiveness and financial resources to fund more than a few regions. Consequently, BMEL needed the competition to transfer accountability for selecting the pilot regions to an independent jury. However, BMEL could not provide resources needed to gather relevant information for jury members even though an objective selection of the best concepts seems hardly possible given differences between regions, concepts and unspecific assessment criteria. The lacking resources of BMEL also led to comprehensive decentralization leaving most of the costs to the regions. Existing funding rules, missing experience and low economies of scale required high efforts of regional financial administration. Moreover, discretion for innovative approaches was not used because regional actors feared penalties of the audit court which would have been problematic particularly for economically weak regions. The general rules of government funding also impede that control efforts did not slow down with MBO and the trust put in those implementing the programme – intended to increase motivation – was undermined.

Thirdly, performance benchmarks, common goals and hierarchies are prerequisites of the instruments and all missing here. In the private sector, profit and survival in the competition are clear yardsticks and common goals of corporations. In the competition, the applicants could use the information asymmetry concerning the degree of innovation in their favour. Regional actors experienced with competitions also trusted that the funding institution would agree to changes to the submitted proposals because it depended on the engagement of regional actors and planned on showing off the programme as a success. MBO was also not able to provide an objective yardstick. Regional representatives and project sponsors used the flexibility in measuring indicators and their information asymmetries to claim that target values have been reached. Furthermore, the partnerships often set only vague goals to integrate heterogeneous interests in the regions. This led to conflicts and consequently to high efforts to integrate all partners compromising the focus on the regional goals and needs. Finally, the actors involved were not embedded in a hierarchy but in reciprocal relationships. BMEL and regional representatives did not use opportunities for sanctioning because demands for the repayment of funds would have hurt those actors whose (future) engagement and cooperation was considered vital by their partners. The multi-year development process, however, depend on the cooperation and imagination of a variety of regional actors. Hence, financial control was not independent on the one hand and transparency as well as accountability of decisions and outputs are blurred on the other.

5. Discussion: the wrong management instruments or just improperly applied?

Private-sector instruments like competition, MBO and decentralization are widely used in rural and regional development policy. As the literature review has shown, there are, however, rival propositions whether these instruments are effective, efficient and legitimate. Our case study supports the arguments against the instruments demonstrating that the effectiveness, efficiency and legitimacy of the instruments are considerably limited for developing peripheral rural areas. The results confirm the often negative assessment of NPM instruments (Hood Citation1991; Osborne Citation2006) and partnerships (Edwards et al. Citation2001; Scott Citation2012). These issues persist although the BMEL tried to apply the instruments in such ways as suggested in the scholarly discussion. So, the competition was restricted to peripheral rural regions and every bidding region received money to even differences in capacities and experiences as the most important success factors (Kiese and Kahl Citation2017; Woods, Edwards, and Anderson Citation2007). BMEL also organized a thematically open competition to avoid regionals actors aligning to national expectation (Lowndes and Skelcher Citation1998; Rehfeld and Terstriep Citation2019). In fact, these measures did not suffice to solve the problems so that all contra propositions in were identified in our case.

Concerning MBO, BMEL applied a bottom-up approach as the literature suggests (Drucker Citation1954; Rodgers and Hunter Citation1992). Therefore, the regional level did not reject the objectives being able to propose them. However, project sponsors could reject operational goals because they were often not participated in goal setting. Beyond that, the results support all propositions against MBO except that actors only focused on measurable goals (Pugalis Citation2013) was at best the case in one region. BMEL and regional representatives hardly committed to MBO as a prerequisite of its functioning (Rodgers and Hunter Citation1992). Besides the focus on spending the budget, this was also because decision-makers did not see quantified targets as useful since their goals were not prioritizable, often conflicting or permanently changing as Sager and Sørensen (Citation2011) also show.

Decentralization was as comprehensive as possible in German funding regulations. Therefore, BMEL could mitigate negative effects of conditions and limits of regional competences (Davies Citation2002, Citation2004; Rummery Citation2002; Shucksmith Citation2010). The results, however, support the other arguments against decentralizations from .

The case study results point to three underlying causes. The identified interest coalitions focus on applying for and making full use of the available funding, what Bernt (Citation2009) called grant coalitions. Grant coalitions do not only exist on the local level, as he shows, but our results suggest they include actors on all levels of multi-level governance. Our results confirm what was found for EU structural policy that financial absorption was the only publicly visible and politically important performance indicator (Bachtler and Ferry Citation2015). Accordingly, measures to accelerate the spending of the budget result in lower effectivity of resource allocation. The institutional framework determines the resources of the actors and therefore the functionality of the instruments. Selection committees lack the resources to assess the degree of innovation of each submitted application (cf. Küpper et al. Citation2018). The applicants could use this information asymmetry in their favour – in a similar way as the regional actors did in MBO. The costs for reducing these asymmetries would be high (Groeneveld and Van De Walle Citation2011). There are also not many incentives for this because it has potentially negative effects on how success stories may be propagated. Irrespective of MBO and decentralization, general funding rules by the government had to be applied, what led to a mixing of self-regulation and control undermining the motivating function of MBO (Drucker Citation1954). As the result, regional actors were not always forthcoming in sharing valid information with authorities impeding mutual learning opportunities. Moreover, the regularities produce bureaucracy discouraging particularly civil society actors from participating, as Davis (Citation2004) argues. Governance research often ignores the enormous implementation costs particularly of financial decentralization which requires specific resources often missing on the regional level as our results highlight.

Finally, there are certain preconditions that ensure functionality of the instruments in private sector, but these are missing in rural development. In the policy arena, objective quality or performance measures are missing. Pugalis (Citation2013, 620) points in the context of MBO to the important role of consultants who sometimes deliberately keep quiet about methodological inconsistencies to portray actions as ‘objectively’ correct and efficient. Competitions potentially may increase project quality and widen the circle of recipients of funds, but this requires an independent jury familiar with the problems on the ground (Rehfeld and Terstriep Citation2019). Both conditions can be satisfied for competitions within a region but are improbable for selecting funding regions. In addition, we have argued, that there are, unlike corporations, heterogeneous interests, goals and needs within a region (cf. Gherhes, Brooks, and Vorley Citation2020; Jones and Little Citation2000). Accordingly, there is a trade-off between effective and efficient regional partnerships and inclusive democratic processes (Davies Citation2004; Rehfeld and Terstriep Citation2019).

Participation in a partnership depends on the willingness and capacity of the actors involved leading to a selective participation and various opportunities to influence the process (Davies Citation2007; Edwards et al. Citation2001; Swyngedouw Citation2005). As our results show as well, the elite nature of partnerships reproduces power relations, excludes unwanted actors from power, and blurs responsibilities (Clarke and Glendinning Citation2002; Scott Citation2012). Sørensen and Torfing (Citation2009) even argue that these types of partnerships and the parallel political structures they generate actually weaken representative democracy.

Our case covers a careful conception of the private-sector instruments tested to avoid common application mistakes. However, we could only marginally observe the results the NPM literature purports. We conclude that the three instruments are not suitable for rural development. In principle, interest coalitions and institutions can be altered or their negative consequences mitigated. The funding authority could, for instance, reduce the regional budgets or introduce an n + x rule, as in EAFRD possible but not in German regulation, to diminish the pressure to spend the money. Or the state could have been in charge of financial administration as in LEADER. However, missing preconditions for the proper functioning of the instruments in rural development remain an insurmountable obstacle. Private-sector instruments were introduced to make rural policy more rational and independent from political and bureaucratic wangling. Our results rather suggest lower effectivity, efficiency and legitimacy and even an increase in these issues.

An important limitation of our study is the focus on the pilot programme. Therefore, we cannot compare the results with alternative instruments, particularly more traditional hierarchical top-down instruments or investigate interactions in different instrument mixes (Howlett, Kim, and Weaver Citation2006). Therefore, we compared our results with theoretical propositions and were able to analyse effectivity, efficiency and legitimacy what has never been done as comprehensively before. Consequently, there is considerable demand for further research about comprehensive effects of instruments for the development of rural areas and about the transferability of our results to regional policy in general.

6. Conclusions

The analysed private-sector instruments for developing rural areas appear not to be very effective, efficient and legitimate. This is because the goals of interest coalitions and existing institutions thwart such an outcome, and because regions are not structured like corporations. Which alternative approach can we now recommend? The most efficient and democratically legitimate way would be to increase local government receipts. However, such an approach would not necessarily foster policy innovations und could reinforce policy lock-ins. Concluding from our results, we cannot recommend competitions for initiating innovations. Therefore, peripheral rural regions, where organizational capabilities and absorptive capacities are scarce (Kiese and Kahl Citation2017), need long-term support and essentially sustaining cooperation with external experts for specific development problems as a ‘regeneration outreach’ (Küpper et al. Citation2018). Rehfeld and Terstriep (Citation2019) implied that comprehensive strategies are often too complex for a fluid context, like structural development, and therefore thematically focused processes with selective participations are required.

Because nobody really knows how regional development can optimally be supported, a collective learning process is needed that connects both local knowledge and expertise (High and Nemes Citation2007). The various levels depend on each other. Although higher-level governments can provide funding and know-how, they still rely on local actors’ engagement and willingness to participate in the process. Our results indicate that MBO cannot organize such mutual learning and cooperation, since there are no incentives for sharing information about failures. Furthermore, MBO requires stability and the ability to control the environment (Hood Citation1991). Necessary target adjustments, accordingly, block the positive outcomes of target agreements by reducing their binding effects. The theory of contracts (OECD Citation2007) suggests that relational contracts are better suited to developing peripheral rural regions than the studied instruments. Relational contracts stipulate the requirements for mutual decision-making and exchange of information across the levels of governance. The contract neither regulates the means nor the ends but the processes for negotiation and arbitration in case of conflicts. By rules of transparency, political accountability replaces juridical enforcement. The contract can contain targets with the purpose of structuring the dialogue about expected outcomes. As planning practice shows, targets facilitate intensive dialogue between experts and politicians which enhances mutual trust and democratic quality of decisions (Sager and Sørensen Citation2011).

Finally, other instruments for supporting rural development may have shortcomings as well. We have not found, however, any evidence to conclude that those private-sector instruments we analysed perform especially well. We would like to warn against succumbing to the zeitgeist by trusting consulting firms’ talk about panaceas. The utility of new instruments needs to be tested and demonstrated first before being applied on a large scale – as happened with the EAFRD programme.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the German Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture (BMEL) [grant number 1005-68601-01063225]. We thank Will Poppe for assistance with the English language, and Jessica Brensing for comments that greatly improved the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- AK VGRdL. 2020. Bruttoinlandsprodukt, Bruttowertschöpfung in den kreisfreien Städten und Landkreisen der Bundesrepublik Deutschland 1992 und 1994 bis 2018. https://www.statistikportal.de/sites/default/files/2020-11/vgrdl_r2b1_bs2019.xlsx(26.01.2021)

- Bachtler, J., and I. Begg. 2018. “Beyond Brexit: Reshaping Policies for Regional Development in Europe.” Papers in Regional Science 97 (1): 151–170. doi:10.1111/pirs.12351

- Bachtler ohn and Martin Ferry. 2013. “Conditionalities and the Performance of European Structural Funds: A Principal–Agent Analysis of Control Mechanisms in European Union Cohesion Policy.” Regional Studies. doi:10.1080/00343404.2013.821572

- Bachtler, J., and M. Ferry. 2015. “Conditionalities and the Performance of European Structural Funds: A Principal–Agent Analysis of Control Mechanisms in European Union Cohesion Policy.” Regional Studies 49 (8): 1258–1273. doi:10.1080/00343404.2013.821572

- Bailey, N., and M. Pill. 2015. “Can the State Empower Communities Through Localism? An Evaluation of Recent Approaches to Neighbourhood Governance in England.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 33 (2): 289–304. doi:10.1068/c12331r

- BBSR. 2020. Indikatoren und Karten zur Raum- und Stadtentwicklung. www.inkar.de (26 January 2021).

- Benz, A. 2012. “Yardstick Competition and Policy Learning in Multi-level Systems.” Regional & Federal Studies 22 (3): 251–267. doi:10.1080/13597566.2012.688270

- Bernt, M. 2009. “Partnerships for Demolition: The Governance of Urban Renewal in East Germany's Shrinking Cities.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 33 (3): 754–769. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2009.00856.x

- Bevir, M. 2011. “Democratic Governance: A Genealogy.” Local Government Studies 37 (1): 3–17. doi:10.1080/03003930.2011.539860

- BMELV. 2011. Modellvorhaben LandZukunft: Denkanstöße für die Praxis. Berlin: BMELV.

- Bosworth, G., I. Annibal, T. Carroll, Liz Price, Jessica Sellick, and John Shepherd. 2016. “Empowering Local Action Through Neo-endogenous Development; The Case of LEADER in England.” Sociologia Ruralis 56 (3): 427–449. doi:10.1111/soru.12089.

- Bryson, J., and W. Roering. 1987. “Applying Private-sector Strategic Planning in the Public Sector.” Journal of the American Planning Association 53 (1): 9–22. doi:10.1080/01944368708976631

- Clarke, J., and C. Glendinning. 2002. “Partnership and the Remaking of Welfare Governance.” In Partnerships, New Labour and the Governance of Welfare, edited by C. Glendinning, M. A. Powell, and K. Rummery, 33–50. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Cox, K. 1993. “The Local and the Global in the New Urban Politics: A Critical View.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 11 (4): 433–448. doi:10.1068/d110433

- Davies, J. 2002. “The Governance of Urban Regeneration: A Critique of the ‘Governing Without Government’ Thesis.” Public Administration 80 (2): 301–322. doi:10.1111/1467-9299.00305

- Davies, J. 2004. “Conjuncture or Disjuncture? An Institutionalist Analysis of Local Regeneration Partnerships in the UK.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 28 (3): 570–585. doi:10.1111/j.0309-1317.2004.00536.x

- Davies, J. 2007. “The Limits of Partnership: An Exit-Action Strategy for Local Democratic Inclusion.” Political Studies 55 (4): 779–800. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.2007.00677.x

- Drucker, P. 1954. The Practice of Management. New York: Harper & Row.

- Duckworth, R., J. Simmons, and R. McNulty. 1986. The Entrepreneurial American City. Washington, DC: Department of Housing and Urban Development.

- Ebinger, F., S. Grohs, and R. Reiter. 2011. “The Performance of Decentralisation Strategies Compared: An Assessment of Decentralisation Strategies and Their Impact on Local Government Performance in Germany, France and England.” Local Government Studies 37 (5): 553–575. doi:10.1080/03003930.2011.604557

- Edwards, B., M. Goodwin, S. Pemberton, and M. Woods. 2001. “Partnerships, Power, and Scale in Rural Governance.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 19 (2): 289–310. doi:10.1068/c12m.

- Eiser, D. 2020. “Will the Benefits of Fiscal Devolution Outweigh the Costs? Considering Scotland’s New Fiscal Framework.” Regional Studies 54 (10): 1457–1468. doi:10.1080/00343404.2020.1782875

- Elbe, S. 2011. “Regionalbudgets im Modellvorhaben Regionen Aktiv - und wie geht das in Zukunft?” In Finanzierung regionaler Entwicklung, edited by S. Elbe and F. Langguth, 69–84. Aachen: Shaker.

- Fürst, D. 2006. “The Role of Experimental Regionalism in Rescaling the German State.” European Planning Studies 14 (7): 923–938. doi:10.1080/09654310500496313

- Gherhes, C., C. Brooks, and T. Vorley. 2020. “Localism Is an Illusion (of Power): the Multi-scalar Challenge of UK Enterprise Policy-making.” Regional Studies 54 (8): 1020–1031. doi:10.1080/00343404.2019.1678745

- Grabher, G. 1993. “The Weakness of Strong Ties: The Lock-in of Regional Development in the Ruhr Area.” In The Embedded Firm. On the Socioeconomics of Interfirm Relations, edited by G. Grabher, 255–277. London: Routledge.

- Groeneveld, S., and S. Van De Walle. 2011. “Steering for Outcomes: The Role of Public Management.” In New Steering Concepts in Public Management, edited by S. Groeneveld and S. Van De Walle, 1–8. Emerald: Bingley.

- Harvey, D. 1989. “From Managerialism to Entrepreneurialism: The Transformation in Urban Governance in Late Capitalism.” Geografiska Annaler. Series B, Human Geography 71 (1): 3–17. doi:10.1080/04353684.1989.11879583

- High, C., and G. Nemes. 2007. “Social Learning in LEADER: Exogenous, Endogenous and Hybrid Evaluation in Rural Development.” Sociologia Ruralis 47 (2): 103–119. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9523.2007.00430.x

- Hood, C. 1991. “A Public Management for all Seasons?” Public Administration 69 (1): 3–19. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9299.1991.tb00779.x

- Howlett, M., J. Kim, and P. Weaver. 2006. “Assessing Instrument Mixes Through Program- and Agency-Level Data: Methodological Issues in Contemporary Implementation Research.” Review of Policy Research 23 (1): 129–151. doi:10.1111/j.1541-1338.2006.00189.x

- Jessop, B. 1997. “The Entrepreneurial City: Re-imaging Localities, Redesigning Economic Governance, or Restructuring Capital?” In Transforming Cities: Contested Governance and New Spatial Divisions, edited by N. Jewson and S. MacGregor. London: Routledge, 28–41.

- Jones, O., and J. Little. 2000. “Rural Challenge(s): Partnership and New Rural Governance.” Journal of Rural Studies 16 (2): 171–183. doi:10.1016/S0743-0167(99)00058-3

- Kiese, M., and J. Kahl. 2017. “Competitive Funding in North Rhine-Westphalia: Advantages and Drawbacks of a Novel Delivery System for Cluster Policies.” Competitiveness Review 27 (5): 495–515. doi:10.1108/CR-09-2016-0062

- Küpper, P., S. Kundolf, T. Mettenberger, and G. Tuitjer. 2018. “Rural Regeneration Strategies for Declining Regions: Trade-off Between Novelty and Practicability.” European Planning Studies 26: 229–255. doi:10.1080/09654313.2017.1361583.

- Levelt, M., and T. Metze. 2014. “The Legitimacy of Regional Governance Networks: Gaining Credibility in the Shadow of Hierarchy.” Urban Studies 51 (11): 2371–2386. doi:10.1177/0042098013513044

- Lowndes, V., and C. Skelcher. 1998. “The Dynamics of Multi-Organizational Partnerships: An Analysis of Changing Modes of Governance.” Public Administration 76 (2): 313–333. doi:10.1111/1467-9299.00103

- Margarian, A., and P. Küpper. 2011. “Identifizierung peripherer Regionen mit strukturellen und wirtschaftlichen Problemen in Deutschland.” Berichte über Landwirtschaft 89: 218–231.

- Marquardt, D., J. Möllers, and G. Buchenrieder. 2012. “Social Networks and Rural Development: LEADER in Romania.” Sociologia Ruralis 52 (4): 398–431. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9523.2012.00571.x

- Newman, J. 2001. Modernizing Governance: New Labour, Policy and Society. London: Sage.

- OECD. 2007. “A Contractual Approach to Multi-level Governance.” In Linking Regions and Central Governments. Contracts for Regional Development, edited by OECD. Paris: OECD, 21-70.

- OECD. 2019. Rural Policy 3.0. People-centred Rural Policy. Paris: OECD.

- Osborne, S. 2006. “The New Public Governance?” Public Management Review 8 (3): 377–387. doi:10.1080/14719030600853022

- Powell, M., and M. Exworthy. 2002. “Partnerships, Quasi-networks and Social Policy.” In Partnerships, New Labour and the Governance of Welfare, edited by C. Glendinning, M. Powell, and K. Rummery, 15–32. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Pugalis, L. 2013. “Hitting the Target but Missing the Point: The Case of Area-based Regeneration.” Community Development 44 (5): 617–634. doi:10.1080/15575330.2013.854257

- Qian, Y., and B. Weingast. 1997. “Federalism as a Commitment to Reserving Market Incentives.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 11 (4): 83–92. doi:10.1257/jep.11.4.83

- Rehfeld, D., and J. Terstriep. 2019. “Regional Governance in North Rhine-Westphalia – Lessons for Smart Specialisation Strategies?” Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research 32 (1): 85–103. doi:10.1080/13511610.2018.1520629

- Risse, T., and M. Kleine. 2007. “Assessing the Legitimacy of the EU's Treaty Revision Methods.” Journal of Common Market Studies 45 (1): 69–80. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5965.2007.00703.x

- Rodgers, R., and J. Hunter. 1992. “A Foundation of Good Management Practice in Government: Management by Objectives.” Public Administration Review 52 (1): 27–39. doi:10.2307/976543

- Rummery, K. 2002. “Towards a Theory of Welfare Partnerships.” In Partnerships, New Labour and the Governance of Welfare, edited by C. Glendinning, M. Powell, and K. Rummery, 229–245. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Sabel, C. 1995. “Bootstrapping Reform: Rebuilding Firms, the Welfare State, and Unions.” Politics & Society 23 (1): 5–48. doi:10.1177/0032329295023001002

- Sager, T., and C. Sørensen. 2011. “Planning Analysis and Political Steering with New Public Management.” European Planning Studies 19 (2): 217–241. doi:10.1080/09654313.2011.532666

- Scharpf, F. 2010. Community and Autonomy: Institutions, Policies and Legitimacy in Multilevel Europe. Frankfurt: Campus.

- Scott, A. 2012. Partnerships: Pandora’s Box or Panacea for Rural Development? Birmingham: Birmingham City University.

- Shucksmith, M. 2010. “Disintegrated Rural Development? Neo-endogenous Rural Development, Planning and Place-Shaping in Diffused Power Contexts.” Sociologia Ruralis 50 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9523.2009.00497.x

- Sørensen, E., and J. Torfing. 2009. “Making Governance Networks Effective and Democratic Through Metagovernance.” Public Administration 87 (2): 234–258. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9299.2009.01753.x

- Swyngedouw, E. 2005. “Governance Innovation and the Citizen: The Janus Face of Governance-Beyond-the-State.” Urban Studies 42 (11): 1991–2006. doi:10.1080/00420980500279869

- Tiebout, C. 1956. “A Pure Theory of Local Expenditures.” Journal of Political Economy 64 (5): 416–424. doi:10.1086/257839

- Voets, J., and W. Van Dooren. 2011. “Search of Network Performance.” In New Steering Concepts in Public Management, edited by S. Groeneveld and S. Van De Walle, 185–203. Emerald: Bingley.

- Woods, M., B. Edwards, J. Anderson, and G. Gardner. 2007. “Leadership in Place: Elites, Institutions and Agency in British Rural Community Governance.” In Rural Governance: International Perspectives, edited by L. Cheshire, V. Higgins, and G. Lawrence, 211–225. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Yin, R. 2014. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. London: Sage.