ABSTRACT

The aim of this article is to critically situate co-production methods such as that of the urban living lab within contemporary planning theory and in particular to the ideas of ‘agonistic planning’ and the ‘trading zone’. By critically review relevant literature and discussing the results of an ongoing interdisciplinary project, we will show a number of potentials and issues when translating the urban living lab idea to planning contexts. Potentially our urban living labs have opened up opportunities for local planners to discuss controversial issues by using the idea of nature based solution as a boundary-object/trading-zone. On the other hand, planners’ positivistic and incremental understanding of city making hinders a transformative understanding of the urban living lab and nature based solution in favour of more fashionable technological fixes.

1. Introduction

For quite some time, post-WWII urban planning has gone through dramatic changes and critiques. The pushes for increasing deregulation and liberalization of the economy in countries such as the US and UK during the 1980s have put into question the need for centralized urban planning. Klosterman (Citation1985) traces back this argument to the theses of Adam Smith and John Stuart Mill who emphasized the freedom of the individual, the self-regulating mechanism of the market and the rule of law as the main forces to guide economies. Two of the strongest critiques of planning are generally concerned with the inflexibility of the legal planning framework to accommodate an increasingly deregulated economy and/or the ‘dirigiste’ legacy of planning that allows very little inputs from society at large (Taylor Citation1998) – an aspect further complicated by the increased multicultural base of today’s society. Already in the 1950s, Lindblom (Citation1959) critiques long-term, comprehensive planning by noting that seldom a planner is able to have enough resources and time to deliver on all of the different social, economic aspects that shape cities. According to Lindblom, planning can be better practised for short-term, focused issues by using an incremental approach (also known as the partisan mutual adjustment method) that tries to reach a compromise/deal among the conflicting parties on circumscribed issues rather than aiming for a utopist, comprehensive agreement of the whole society at large. However, one of the major drawbacks of incremental planning is its intrinsic conservative nature as it seeks to develop solutions that adjust to the status quo. In Lindblom’s incremental planning questions related to (who has or has not) power are not answered. ‘What matters is whether your counterpart agrees with a concrete proposal, not why she/he agrees’ (Mäntysalo, Balducci, and Kangasoja Citation2011, 259). Regarding the second strand of criticism of planning, that of dirigisme, in its influential review of post-WWII urban planning theory, Taylor (Citation1998) adds that planners’ ‘social blindness’ and lack of consensus of the overarching planning values were at the root of their inability to manage the reconstruction process. Davidoff’s work (Citation1965) on advocacy planning sets the tone for a renewal of the planning discipline around the issue of pluralism and democracy. He criticizes the practice of ‘unitary planning’ (Davidoff Citation1965, 332), i.e. the idea that planning is the monopoly of cities’ planning departments. Advocacy in planning is for Davidoff ‘professional support for competing claims about how the community should develop’ (Davidoff Citation1965, 333). Several planning scholars have tried to deal with the irreducibility of disagreements on the fundamental normative principles of what a city is supposed to be by resorting to different models of rationality. Sager (Citation1999) reviews a number of these approaches: from Faludi’s use of the concepts of social rationality and human growth; to Friedmann’s work on substantial rationality to outline his view of ‘transactive planning’, being this latter a synthesis of expert and experiential knowledge for implementing actions into the public domain (Friedmann Citation1993); to Forrester’s idea of critical pragmatism as mutuated from Habermas’ theory of communicative rationality. While from the 1990s onward, ‘communicative planning’ (Healey Citation1997), i.e. urban planning based on an un-dominated communication between the parties at stake, gets traction in urban planning circles, from the turn of the 2000s Hillier (Citation2003) instead suggests turning to Mouffe’s (Citation2000) agonistic rationality to ‘provide [rather than negate] channels of expression in which conflicts can be expressed’ (Hillier Citation2003, 43). In Mouffe’s (Citation2000, 9) words, there is the need to reinvent the rules of (liberal democratic) decision making in terms of ‘agonistic pluralism’. Thus, similarly to Davidoff’s (Citation1965, 333) remarks about the positive effects of the ‘adversary nature of plural planning’ for knowledge-making, Mouffe (Citation2000, 14) sees ‘the category of the ‘adversary’ […] at the very centre of [her] understanding of democracy as “agonistic pluralism”’. While recent work by Sager (Citation2019) concedes that in light of today’s popularity of authoritarian populism the ‘credo of [the consensus planning theory] is meaningless’, Moroni (Citation2019) proposes a framework that go beyond the binary agonism V deliberative consensus; in his view consensus is required at the higher ‘constitutional’ level of the state, i.e. there needs to be an agreement about the role of the State in society and the so called rules of the game, while, at the level that is close to the political, agonism can be embraced as ethos.

Based on these above-mentioned premises, Balducci and Mantysalo (Citation2013) spin-off a synthesis between Lindblomian incremental planning and collaborative rationalities by resorting to the work of Galison on the ‘trading zones’ (Citation1997). At the same time, the concept of the trading zone attempts to go beyond the limitations described above of incremental and communicative planning. The idea of the trading zone is more aligned to Mouffe’s (Citation2000) idea of agonism who argues that the tensions between the liberalist and deliberative logics cannot be settled with rational communication. Mouffe argues for agonism (as the opposite of destructive antagonism) whereby the adversaries recognize (as Moroni (Citation2019) would argue, at a constitutional level) the legitimacy of each other and compete for their ideas. Galisons idea of the trading zone includes devices that enable such an agonistic exchange. One such device is hybrid languages (like those shown by Mäntysalo and Kanninen (Citation2013) in Kuopio or by Balducci (Citation2013) in Milan) or ‘thin descriptions’ that enable knowledge sharing across different epistemic communities. In this sense, the difference between incremental planning and the trading zone is that the former is strictly focused on reaching an agreement while the latter appreciates the exchange between two parties that have incommensurable ideas about society. It is, in other words, the difference between discussion and dialogue (Bohm and Peat Citation2000). Dialogues are open to exploration and do not necessarily aim to reach a deal. Discussions instead are narrower and aim at reaching a compromise between incommensurable principles. A ‘dialogue can be seen as necessary for arriving at conditions of discussion in the sense of meaningful bargaining’ (Mäntysalo, Balducci, and Kangasoja Citation2011, 264). Similarly to agonism, but unlike communicative rationality, the trading zone approach does not aim for a transcendental truth while acknowledging instead the existence of a public sphere (i.e. society is more than the sum of individual, partisan interests) that incremental planning does not recognize.

We confronted these issues in an ongoing interdisciplinary research project in which we have helped a number of European municipalities to establish Urban Living Labs (ULLs) to develop Nature-Based Solutions (NBS). From a European policy perspective, NBS reflects the European Commission interests in circular economy (EC Citation2015a,Citation2015b). NBSs are thus supposed to promote ‘the circular use of resources making use of closed nutrient, water, and energy cycles by reusing waste rather than discarding it’ (Katsou et al. Citation2020, 188). NBS can be seen as a vehicle to foster circular city processes. In a more technical language, NBS deals with climate resilience and human health in urban areas by broadening existing ecosystem service approaches to include environmental, social and economic resilience (Katsou et al. Citation2020). Living Labs (LLs), on the other hand, are generally known as an approach to manage open innovation processes where users are integrated into processes to co-create, test and evaluate innovations in open, collaborative, multi-contextual and real-world settings (Ståhlbröst Citation2008). In planning studies, this idea has been analysed by scholars studying the emergence of urban policy experiments to implement sustainability at the city and neighborhood scales (Evans Citation2011; Bulkeley and Castán Broto Citation2013; Karvonen and Van Heur Citation2014; Caprotti and Cowley Citation2017; Bulkeley et al. Citation2016, Citation2019). More recently, and thanks to funding frameworks such as JPI Urban Europe, the urban living lab (ULL) approach has become popular in Europe and beyond (Bylund, Riegler, and Wrangsten Citation2020). The research questions we aim to answer in this paper are how can ULLs help address the following binaries/tensions: unitary vs decentralized planning; communicative vs agonistic rationalities; planning praxis vs experimentation?

As we will see in Section 2, there are different understandings of what a ULL is supposed to be. Similarly to the neighborhood laboratory established by Calvaresi and Cossa (Citation2013) in Milan, in our ULL project we framed the NBS as a trading zone, or more specifically as a ‘boundary object’ (Star and Griesemer Citation1989), i.e. a vehicle that allows communication between different epistemic groups with different value principles. For example, in the capacity building meeting preceding the establishment of the ULL in Genoa, Italy the concept of the NBS was used as a bridge language between city planners, environmental engineers and politicians. While the planners were concerned with issues related to social justice and accessibility to a dilapidated area of the city (Lagaccio), the environmental engineers were eager to deploy environmental methods to deal with the periodic issue of flooding in Genoa, and the politicians were keen to redevelop an area that for a long time was blighted by segregation and poverty. In this way, we avoided a broader discussion on the comprehensive planning of the city (which anyways is ‘traveling’ on another, independent track and timeline) and focused on applied, opportunistic interventions that could anyway capitalize on disciplinary and citizens’ ‘plurality’ (Mouffe Citation2000) to re-discuss the status quo in very pragmatic ways. In our ULLs capacity workshops, we centred on the idea of urban experiment and social learning as a way to mobilize transdisciplinary understandings of space and society (Rizzo and Galanakis Citation2015, Citation2017) in order to produce alternative scenarios. In the remainder of this paper, we will first (Section 2) outline the relevant literature on LL and ULL originating from the field of organization and urban studies while in Section 3 we will outline the research methodology and case studies. In Section 4, we report the results of our workshops and survey while in Section 5 we will discuss the results in light of the threads raised in this section, highlighting the potentials and challenges of ULLs for innovating planning practice.

2. Literature: from living labs to urban living labs

Contemporary cities are going through an intense transformation phase driven by increasing urban complexity and grand societal challenges. Hence, there is a growing trend in public policy to align urban developments to the citizens’ needs by viewing cities as platforms for societal transformation towards addressing issues such as inclusion, equity and opportunities (Juujärvi and Pesso Citation2013; Scholl and Kemp Citation2016). To overcome the issues related to complex societal challenges and rigid, sectoral planning, cities are engaging with innovative solutions and championing urban experiments in order to deliver on these challenges (Bulkeley et al. Citation2019; Willis and Aurigi Citation2020). These innovations in society have touched a wide range of services from small scale, smartphone applications and Internet of Things (IoT) devices (Woodhead, Stephenson, and Morrey Citation2018), to wider socio-technical infrastructures such as the Nature-Based Solution (NBS) (Frantzeskaki et al. Citation2017; Lafortezza and Sanesi Citation2019). Consequently, Living labs have become popular also among urban researchers as a way to manage innovation processes in an open, inclusive and collaborative approach. The innovations are developed by integrating various stakeholders including public organizations, private sectors, universities and finally citizens (Bergvall-Kareborn and Stahlbrost Citation2009). Similarly to Friedmann’s (Citation1993) idea of transactive planning, the core idea of the living lab is to include external sources of knowledge and ideas, and the actors formulating them (see ) within the innovation process. This latter idea is consistent with the notion of ‘Open Innovation’, a term that first coined by Chesbrough (Citation2003).

Originating in the 1970s as part of the Scandinavian workplace democracy movement, participatory design processes were developed with worker unions to incorporate technology in ways that enhanced rather than replaced workers’ skills and local knowledge (Rizzo Citation2017; Rizzo et al. Citation2020). The traditional Scandinavian approach to participatory design is based on the right of the individual to influence her/his own development (Bergvall-Kåreborn and Ståhlbrost Citation2008; Bjerknes and Bratteteig Citation1995; Pekkola, Kaarilahti, and Pohjola Citation2006). However, the nature of involving people in traditional participatory design has fundamental differences with new approaches of user engagement such as Living Lab activities. In the Living Lab activities, participation must be voluntary (Mensink, Birrer, and Dutilleul Citation2010) and the contributors are not necessarily final end-users of the prototyped system, service or solution (Ståhlbröst and Bergvall-Kåreborn Citation2013). Living Lab is more of an umbrella term that emerged in early 2000 (Schaffers et al. Citation2007) with the initial focus on testing new technologies in home-like constructed environments. However, testing new technologies in a simulated lab environment was then replaced by the active engagement of potential users of a given innovation in a real-life situation throughout the whole process (Bergvall-Kåreborn et al. Citation2009; Ståhlbröst Citation2008). Consequently, Living Lab research is heavily inspired by both participatory design and open innovation (Björgvinsson, Ehn, and Hillgren Citation2010; Dell’Era and Landoni Citation2014). After launching the European Network of Living Labs (ENoLL) in November 2006, the living lab approach has been promoted also by the European Union with several grant schemes (such as the JPI Urban Europe) and meetings. What is common in living lab activities is that the innovations must be co-created by all engaged stakeholders and users (Puerari et al. Citation2018), and also these co-creation activities should create value for those involved partners (Schuurman Citation2015).

Only in the last decade theses idea have filtered in urban and planning studies. Thanks to funding networks such as the Joint Programme Initiative (JPI) Urban-Europe (supported by the European Commission in collaboration with other national funding agencies) ULL inspired projects have mushroomed across Europe and beyond. A compact definition of ULL is ‘an approach, or set of methods (an umbrella), geared to make change happen in a co-creative way’ (Bylund, Riegler, and Wrangsten Citation2020, 18). As highlighted by Bulkeley and others (Citation2016, 13), ULL can be ‘seen as a means through which to set up demonstrations and to trial different kinds of intervention in the city’ aimed at achievienging urban sustainability as well as to ‘bring together multiple actors that seek to intervene […] through forms of open and engaged experimentation’. Urban experiments in planning have been analysed from different perspectives. Bulkeley and Castán Broto (Citation2013) look at them from the perspectives of state rescaling under neoliberalism (Brenner Citation2009), institutional innovation (Baccarne et al. Citation2014; Chronéer, Ståhlbröst, and Habibipour Citation2018; Steen and van Bueren Citation2017; see our ), and the design of urban futures (Evans Citation2011; Karvonen and Van Heur Citation2014; Savini and Bertolini Citation2019).

Table 1. Review of ULL literature.

Karvonen and Van Heur (Citation2014) find links with Science and Technology Studies (STS) and the work of Latour on turning societies in scientific laboratories. In this sense, they (Karvonen and Van Heur Citation2014) understand ULLs as performances aimed at persuading the public towards desirable futures. However, as Savini and Bertolini (Citation2019) have argued in their study of urban experiments, while experiments are often perceived as a positive outcome, they may lack the transformational potential to bring change. The choice of the location, direction (i.e. content) and resource allocation are intrinsically political and the interaction of market, political and societal forces may lead to different outcomes (Savini and Bertolini Citation2019). As noted by Bulkeley and others (Citation2019) in a recent survey of 40 ULLs can take quite different forms. They may lean towards strategic experimentation and function as testbeds for products and solutions or towards providing platform for community collaboration and civic demonstration.

Scanning the literature from the field of innovation studies, by assessing 90 sustainable urban innovation projects in the city of Amsterdam, Steen and van Bueren (Citation2017) identified four key characteristics of a ULL, namely: aim, activities, participants and context. Steen and van Bueren (Citation2017) also argued that excluding one or some of these basic components of living labs might lead to disappointing results in the whole societal transformation process. According to this study, the aims of ULL are innovation and formal learning. The main activities are innovation development, co-creation and iteration of the design and development process by considering feedback from the previous steps. When it comes to participants, public and private sectors, citizens and knowledge institutions are of vital importance and finally, the context is always real-life, everyday use context.

Furthermore, Juujärvi and Pesso (Citation2013) have identified three main types of ULLs when it comes to the level of engagement in the process. In the first type, the urban context can act as a technology-assisted research environment by collecting as many citizens’ feedback as possible (if needed, also by using different sensors and IoT deployments). In the second type, citizens can also be co-creators who contribute to designing and developing local services and urban artefacts (e.g. communal yards, day-care services, etc.,). The third type of ULL is when, by using new processes and tools, new kinds of planning processes are developed by actively engaging citizens. In this type, the objective is to plan procedures and facilitate vision planning which will lead to increase mutual learning between various stakeholders and citizens.

In order to present a typology for ULLs, Marvin and his colleagues (Citation2018) have identified three main types of ULLs, namely, strategic ULLs, civic ULLs and organic ULLs. Strategic ULLs mainly consider their national urban areas as the potential contexts to develop and implement different living lab activities that are mainly focused on testing the solutions. Civic ULLs tend to reflect on the particular urban contexts in order to overcome the barriers with the local infrastructures rather than national innovation priorities. Finally, the organic ULLs are mainly associated with the needs of particular communities, such as social needs, poverty, pollution and so forth.

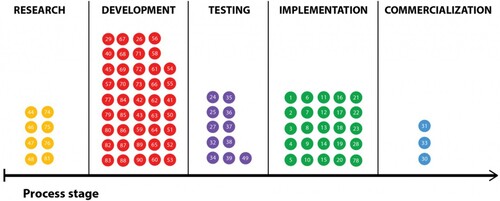

Veeckman and van der Graaf (Citation2015) identified three main benefits of viewing the city as a ULL, which are: (1) ULL facilitates citizen participation and collaboration; (2) ULL facilitates co-creation processes in the city and (3) ULL approach empowers citizens. They also suggested that by using different tools and techniques, citizens who do not have very high technical skills are also able to participate in the progress of their cities, and in the development of different solutions that are beneficial for the self and the city as a whole. Steen and van Bueren (Citation2017), identified five main innovation-related activities in ULLs, namely: (1) research, (2) development, (3) testing, (4) implementation and (5) commercialization. They then classified 90 potential living lab projects in the Amsterdam region under these five themes (see ). Their findings showed that the development of innovation in ULL is the most frequent innovation process phase. Steen and van Bueren argue that only projects that conduct development activities can be considered as a living lab project, although all of these 90 projects in Amsterdam labeled themselves as ‘living lab’ project. Accordingly, in a ULL context, the innovation must be developed in the city by including relevant stakeholders and citizens, and testing or implementing an innovation would be a complementary phase.

Figure 2. Classification of innovation process phase of 90 potential living lab projects in the Amsterdam region (Steen and van Bueren Citation2017).

In order to assess the role of urban experiments for local planning processes, Scholl and Kemp (Citation2016) conducted a case-based analysis of the city of Maastricht and identified five key characteristics of ULLs (which they labeled as ‘city lab’) as a distinct analytical category for looking at urban labs and urban experiments from a planning perspective. First, city labs are hybrid organizational forms purposefully positioned at the border of local administration and society. Second, city labs are places of experimental learning and are learning environments for new forms of governance. The third characteristic is that city labs are multi-stakeholder settings including the local administration and focus on co-creation. Fourth, city labs use co-creation in conducting experiments. And fifth, city labs approach complex problems in a multi-disciplinary way, by drawing on knowledge from different disciplines.

3. Case studies and methods

The case studies we will report on are part of an ongoing, large interdisciplinary project which is funded by the European Commission under the Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme. The project aims to develop smarter, more inclusive, more resilient and increasingly sustainable societies through the application of nature-based solutions (NBS). Several recent projects have reflected upon NBSs within the urban context. One example of such a project is URBAN GreenUp projectFootnote1 that aims at developing, applying and validating a methodology for Renaturing Urban Plans to mitigate the effects of climate change, improve air quality and water management and increase the sustainability of our cities through innovative NBSs. Another example is Nature4Cities projectFootnote2 that aims to create a comprehensive reference platform for NBSs, by offering technical solutions, methods and tools to empower urban planning decision making. GrowGreen projectFootnote3 is also a project that aims at investing in NBS (high-quality green spaces and waterways) to develop habitable cities, capable of dealing with major urban challenges, such as flooding, heat stress, drought, poor air quality, unemployment and biodiversity-loss. Common to all these projects is that NBSs aim to overcome urban challenges and accordingly, NBSs are developed in the context of cities. Despite this, none of the abovementioned projects have considered ULLs as the overall approach in which facilitates the NBS development process. In our project, we take up this challenge, namely using the ULL approach to develop NBS.

The project partners (including ten municipalities plus research, business and industry) commit to addressing the challenges that cities around the world are facing today, by focusing on climate and water-related issues, within an innovative and citizen-driven paradigm. The project has three frontrunner cities, Eindhoven, Genova and Tampere, each with a track record of employing smart, citizen-driven solutions for sustainable development. These front-runners support seven follower cities: Stavanger, Prague, Castellon, Cannes, Basaksehir, Hong Kong and Buenos Aires; plus share experiences with observers located in the City of Guangzhou and the Brazilian network of Smart Cities. In this study, we will mainly report on the cities of Eindhoven, Genova, Tampere, Stavanger, Prague, Castellon, Cannes and Basaksehir.

Within this project, we understand the ULL as a process tied to an urban experiment (Savini and Bertolini Citation2019) that aims at triggering social learning and institutional change. Our idea of ULL capitalizes on the idea of ‘plurality’ (Davidoff Citation1965; Mouffe Citation2000) and deploys the NBS idea as a boundary object/trading zone to bridge interests and values across different epistemic and stakeholder groups on a circumscribed issue. In this regard, the city can be seen as a living laboratory in which citizens and other stakeholders will actively be involved in the process of designing, developing, implementing, testing and evaluating innovative ideas and solutions (Veeckman Citation2015).

In our project, we have defined three levels of citizen engagement. In the first type, the citizens are affected by the NBS, but may not be actively engaged in the process. In the second type, the citizens are affected by the NBS and participate in their development. In the third type, the citizens as well as other stakeholders are affected by NBS, can influence their development, and have the power of decision making. These three levels of engagement are in line with the classic levels of user engagement in design and development processes (Briefs, Ciborra, and Schneider Citation1983), namely: design for users (first type), design with user (second type) and finally design by users (third type). In order to obtain a better understanding of the ULL from city representatives’ perspective, two workshops were organized, followed by an open-ended questionnaire to validate the collected data in the two workshops (). To promote stronger and more reliable results, the collected data were analysed by three researchers; Microsoft Excel 2016 was used as a spreadsheet tool for combining the collected information.

Table 2. Methodology.

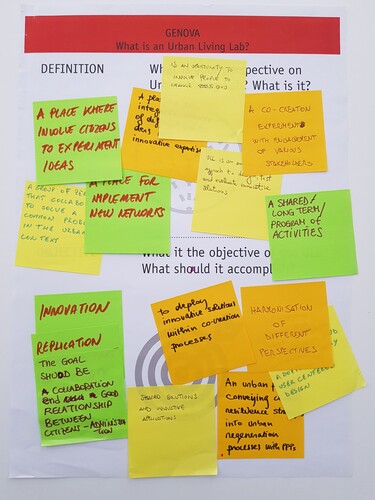

The first workshop was held in November 2017 with seven project partners in the front-runner city of Genova, Italy to deepen the participant’s knowledge and understanding of the ULL concept; while at the same time gathering the partners’ initial reflections on the key components of a ULL (). The participants were asked to respond to questions such as: what aims should the ULL achieve at the end of the project; what is the problem or challenge ULLs should aim to solve; what is an ideal urban context to experiment in; what is the NBS in that context; who should be engaged in the process and how; and finally, how the management structure for the governance of a ULL should look like. The workshop involved 35 participants with representatives from both front-runner and follower cities and lasted for approximately 60 min. In this workshop, the discussion was also captured on post-it notes posted on the templates (). At the end of the workshop, the main outcomes per each discussion-table were shared in a short debriefing by the participants.

The aim of the second workshop carried out in November 2018 in the follower city of Basaksehir, Turkey, was to validate the results obtained in the previous workshop, as well as to exchange knowledge on ULLs and to gain a rich picture of the current situation of the cities by reflecting on the key components of ULLs. In this workshop, we were also interested in knowing in what phase of ULL development the cities were and how were they progressing with setting up and running their own Labs. Seven participants from both front-runners as well as follower cities attended the workshop which lasted approximately 80 min. In this workshop, general discussions around three tables were captured on templates aiming to support the set-up of ULL. At the end of the workshop, a feedback form was distributed among the participants. Accordingly, they reflected on the main learning outcome of the session as well as the next step of developing the ULL framework from their perspective.

4. Results

4.1. The first workshop: Genova, Italy

In the first workshop, seven templates were distributed between participants to identify the key components of a ULL. The templates were focused on the definition and objectives of a ULL in general, the innovation, an urban context, citizens, methodologies and the management structure of a ULL, and finally the conclusion (i.e. one introductory template, five key components and one for sharing the conclusion). In total, the main challenges with the innovative NBSs were identified as involving stakeholders, increasing trust among stakeholders and co-creating with the citizens.

Regarding the stakeholders, the city representatives in the workshop highlighted the importance of identifying and engaging multiple citizen groups ranging from elderly to children, and incorporating different groups as business owners, public servants, researchers, visitors of the ‘space’ and disable.

Looking at the cities’ individual urban challenges, i.e. what the cities want to accomplish, they all highlighted environmental issues both at a global and local levels. On a global level, climate change and natural ecosystem restoration were highlighted. On a city level, the focus was on bringing nature back into the city while on a lower urban level the focus was on decreasing and managing climate hazards as e.g. flooding. These findings are consistent with those reviewed in Section 2, whereby ULLs are more oriented towards ‘urban’ or ‘civic’ innovation (Baccarne et al. Citation2014).

The objectives discussed by the city representatives were in several cases similar to those of the more general LL concept (Bergvall-Kåreborn et al. Citation2009; Ståhlbröst Citation2008) such as providing a framework for research work, a platform for innovating, experimenting, knowledge transfer and co-creation (Karvonen and Van Heur Citation2014; Bulkeley et al., Citation2016; Savini and Bertolini Citation2019). These were, however, supplemented by urban-related aspects, e.g.: the environment where citizens participate in designing solutions, the way to co-construct solutions with citizens and local authorities, a physical place to gather and involve citizens, a shared long-term programme of activities, get people involved in creating their future neighborhood/city, real-life experimentation, and, finally, a focus on long-term scaling of the transformative nature of innovative ideas and solutions. In addition, some city representatives highlighted other specific urban-related aspects such as: developing solutions that could benefit other city objectives, solving the urban problems effectively and sustainably by adopting a user-centred design, making visible NBSs, improving livability, sustainability and social-hydrological resilience of the urban area, raising awareness around ongoing issues and including citizens in decision making regarding issues related to their living environment, and creating a good ULL ‘ecosystem’ and joint value system model.

The most difficult components to discuss in the workshop were the potential management structure for governance of the ULL and also the long-term financing of it. (Almost) all groups identified these as the most difficult to answers. Here, the city representatives discussed issues such as how to finance a ULL and the NBS on a long-term basis, who should be responsible for it, how should the ULL be managed, and by whom. Based on these discussions, it could be concluded that the ULL is much more complex when being implemented in a real city context as the opposite of a scientific lab. Other aspects mentioned by the workshop participants, when asked to explain and elaborate on the key defining components of a ULL, were: testing new solutions, a way to co-construct the city with citizens and local authorities, an innovative governance experience in a real urban context, and a place for implementing new networks.

4.2. The second workshop: Basaksehir, Turkey

To validate the results obtained in the previous workshop, seven templates were developed. The structure of these templates was mainly based on the previous workshop and literature related to the concept of ULL. However, ICT-infrastructure and key stakeholders were added to the previous templates (based on the feedback from the previous phase). The second workshop in Basaksehir resulted in knowledge exchange between participants to obtain a rich picture of the current situation of the cities and reflecting on the key components of a ULL. The workshop also enabled the cities to understand the timing of the project regarding the development of ULL and how to proceed with setting up and running their own ULL. The workshop participants were first introduced to the seven ULL key components that were identified in the previous discussions (i.e. definition and objectives of a ULL, innovative NBS, the context, partners and stakeholders, approach and methodology, the management structure of a ULL, and finally ICT-infrastructure).

At a glance, the results of the workshop showed that some practical aspects are influential in the process of NBS development. The participants highlighted a need of addressing more questions than we had expected such as: how long does the NBS development and experimentation take, how much does it cost, what kind of human resource is needed, and so forth. Also, regarding the partners and stakeholders, the cities sought more help and support to understand what stakeholders should be involved in the NBS development process, and which phase. In relation to citizens, it was suggested that the way in which citizens are affected by the NBS should be taken into account in the templates, not only during the NBS development and implementation process but also after finishing the whole process. With respect to the ICT-infrastructure, questions such as how the data, hardware, software and networks can be put to work were important from the participants’ perspective. Moreover, there emerged the need for identifying the allocation of responsibilities within the ULL infrastructure. Finally, city representatives wanted to make a clear distinction between open and closed data and the way these should be managed within a ULL.

4.3. The questionnaire

When analysing the results from the second workshop, we realized that the concept of ULL was all but clear to our partners. Hence, an open-ended questionnaire (in December 2018) was distributed online to the front-runner and follower cities with the aim to gain more insights into how the concept of Urban Living Lab was understood and implemented (or planned to be implemented) in the front-runner cities. We got back nine responses, of which five were from the front-runner cities and four from the follower cities. When asking the question of ‘what is your view on what an Urban Living Lab is’, the results showed that different cities have interpreted the concept of ULL in different ways. Some of them have viewed ULL as an approach to managing the NBS development process, some have seen it as a testbed to experiment with the NBS, some have considered it as a physical environment (e.g. park, housing block, district, even whole city), and some have understood a ULL as a tool that can transformative thinking and social learning in the city context by involving citizens and other relevant stakeholders.

However, some responses showed that the ULL was equated mostly with that of a technology testbed. For example, one participant from a follower city stated: ‘I don’t have much experience in this field. I’ve listened in many places the concept Urban Living Lab but my definition is an urban space for citizens to test innovations’. Other responses hinted at a strong interest in highly complex technological innovation, which might not be a solution to address socio-technical challenges such as climatic and environmental challenges. A smaller subset of respondents could not still tell apart ULL from a NBS.

In the online questionnaire, we also asked in what phase of NBS development the front-runner and follower cities are and where do they see themselves in the process of setting up and running their own ULL. In so doing, the respondents were asked to answer the question of ‘from your perspective, have you implemented an Urban Living Lab in your city?’ One front-runner city respondent believed that they have fully implemented it in their city. Two of them said ‘yes, we are almost done’; one said ‘yes, we are planning to, but have not started yet’; one mentioned ‘no, we will not implement an Urban Living Lab’; and one city representative also did not know whether they will implement a ULL or not. The one who argued that the ULL has been fully implemented in the city mentioned:

it is not implemented for NBS or as part of the project. The municipality has several ULL-initiatives regarding social issues in specific city districts. The ULLs are financed by the municipality and also partly by the Government to improve living conditions. The municipality is responsible for the ULLs. A range of activities is used for citizen involvement – meetings, workshops, and office days for the municipal workers in the field.

One of the city participants that believed they have almost implemented a ULL said: ‘the city has opened this planning phase area for R&D projects, experiments, people and culture’. From their perspective, systematic methods to run a ULL (vision, data management and learning) are being developed. However, they emphasized that the next steps (experimenting) of the ULL is currently under planning. As another respondent put it:

some ULLs are already working – on other subjects. For NBS, we have existing projects in the inner city where we implement NBS. The learning part is what we want to improve. This needs more focus and organization. Finance and co-creation or other engagement of stakeholders is part of the existing project.

One of the front-runner cities was planning to start setting up and running their ULL. However, from their perspective, a ULL needs a physical place to be operationalized. As they said: ‘the administration is thinking of finding a physical place where to install the ULL, but it has not yet been decided how to implement it. It will probably be managed by the municipality’.

One city participant emphasized that they are not going to set up a ULL. In response to the question of ‘what is the main reason why you will not implement an Urban Living Lab?’ they mentioned that they do not have enough power and influence to implement a ULL in their city. As they said

We are the body in charge of developing the concept behind the city’s architecture, urbanism, development, and formation. We mainly draft and coordinate documents in the following areas: strategic and spatial planning and development, public space, transport, technical matters, landscape such as economic infrastructure and can’t implement projects.

In the last question, we asked the participants to share any other feedback or insights which can be relevant to the main aim of the questionnaire. In general, most of them found the concept of ULL as a very interesting concept and were interested in knowing further about the concept of ULL. Some city representatives asked for more concrete examples, step by step guidelines, and precise instructions in order to gain knowledge on how to set up and run a ULL in the cities. They were also seeking more training sessions on the topic by Living Lab experts to be able to exchange knowledge in this field.

5. Tentative conclusions: ULL and the challenges for planning

This paper builds on the ongoing results of a project that is due by 2023. Therefore, at this stage, we can only attempt to suggest some tentative conclusions for a process that is still ongoing. In the introduction, we presented at length the tensions between incremental and agonistic planning. Our above results show that an incremental understanding of planning, i.e. piecemeal and result-oriented, hinders a broader understanding of co-produced knowledge-making that challenges conventional public participation (see in the famous Arnstein’s (Citation1969) ‘ladder’ the categories ‘consultation’ V ‘partnership’).

We argue that a conservative, incremental understanding of planning practice counters the idea of ULL – that is centred on the active involvement of residents and other relevant stakeholders in an experimental setting – while favouring instead techno-solutions that have little to do with the fundamental shortcomings of planning practice (dirigisme and lack of democracy; see Section 1). Although all parties showed genuine interest in the boundary-object/trading-zone represented by the NBS, planners found it difficult to understand how ULLs could take further this idea in their everyday work.

Furthermore, it must be observed that in traditional living lab settings, the innovation, in our case the NBS, is not regarded as a key component as such since the living lab is viewed as a milieu for innovation, i.e. the goal is to support the dialogue around innovation activities and engage different stakeholders in the development process. In this sense, the idea of ULL is rather different from the usual participatory planning workshop whereby stakeholders are asked to compromise on their values in order to finalize (in the best of the scenarios) a win-win deal.

Finally, and going back to our research questions, how can ULLs help address the threads raised in the introduction? There is no doubt that by working on smaller ULL areas, rather than at the comprehensive city scale, one might misinterpret the real scale of issues such as the socio-spatial segregation and deprivation of Lagaccio in Genova, or the climate adaptation imperative of Dutch cities threatened by sea rise. On the other hand, ULLs are ecosystems that enable dialogues (in our case around the benefits of NBS) that aim at building hybrid understandings between different value systems (Mäntysalo and Kanninen Citation2013): while some stakeholders are drawn by their interest to test already available technological solutions, others focus on people empowerment, while some other are keen to expand their portfolio of NBS to other locations (see also Bulkeley et al., Citation2019). The experimental character of ULLs enables a broad engagement of society in developing understanding of complex urban issues. Our findings show tensions between different city actors whereby an ecological understanding of the city was juxtaposed to a positivistic idea of social and economic progress. Moreover, and in line with their positivistic, technocratic education, while planning experts were keen on avoiding political disputes in ULL, on the other hand, toying with the boundary object of NBS could reveal highly political issues that relate to needs and aspirations for a just and livable city (e.g. access to safe green areas, equitable transport solutions, etc.). We hope to be able to report on these latter issues in future research follow-ups.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the following funding: ‘UNaLab’ is funded by the European Commission under the Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (730052-2) and ‘Eco-district’ funded by the Swedish Research Council Formas (grant #2018-01267). A previous version of this paper was discussed at the 2019 Plannord conference in Norway. The authors further acknowledge two anonymous reviewers who helped improve this paper with their comments in earlier drafts. The usual disclaimers apply.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 UrbanGreenUP, 2019. Accessed 25 September 2020. https://www.urbangreenup.eu/.

2 Nature4cities, 2019. Accessed 25 September 2020. https://www.nature4cities.eu/.

3 Growgreen, 2019. Accessed 25 September 2020. http://growgreenproject.eu/about/project/.

References

- Arnstein, S. R. (1969). “A Ladder of Citizen Participation.” Journal of the American Institute of Planners 35 (4): 216–224.

- Baccarne, B., P. Mechant, D. Schuurman, P. Colpaert, and L. De Marez. 2014. “Urban Socio-Technical Innovations with and by Citizens.” Interdisciplinary Studies Journal 3 (4): 143–156. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-5854-4

- Balducci, A. (2013). “‘Trading Zone’: A Useful Concept for Some Planning Dilemmas.” In Urban Planning as a Trading Zone, edited by A. Balducci and R. Mantysalo, 23–36. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Balducci, A., and R. Mäntysalo. 2013. Urban Planning as a Trading Zone. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Bergvall-Kåreborn, B., C. Eriksson, A. Ståhlbröst, and J. Svensson. 2009. “A Milieu for Innovation: Defining Living Labs.” ISPIM Innovation Symposium, December 6–9. http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2:1004774

- Bergvall-Kåreborn, B., and A. Ståhlbrost. 2008. “Participatory Design: One Step Back or Two Steps Forward?” Proceedings of the Tenth Anniversary Conference on Participatory Design 2008, 102–111.

- Bergvall-Kareborn, B., and A. Stahlbrost. 2009. “Living Lab: An Open and Citizen-Centric Approach for Innovation.” International Journal of Innovation and Regional Development 1 (4): 356–370. doi:10.1504/IJIRD.2009.022727.

- Bjerknes, G., and T. Bratteteig. 1995. “User Participation and Democracy: A Discussion of Scandinavian Research on System Development.” Scandinavian Journal of Information Systems 7 (1): 73–98. https://aisel.aisnet.org/sjis/vol7/iss1/1

- Björgvinsson, E., P. Ehn, and P.-A. Hillgren. 2010. “Participatory Design and ‘Democratizing Innovation.’.” Proceedings of the 11th Biennial Participatory Design Conference, 41–50. doi:10.1145/1900441.1900448.

- Bohm, D., and F. Peat. 2000. Science, Order, and Creativity. New York: Psychology Press.

- Brenner, N. 2009. “Open Questions on State Rescaling.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 2 (1): 123–139. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsp002.

- Briefs, U., C. Ciborra, and L. Schneider. 1983. “Systems Design For, With, and By the Users.” Proceedings of the Ifip Wg 9.1 Working Conference on Systems Design For, With, and by the Users, Riva Del Sole, 20–24 September 1982.

- Bulkeley, H., and V. Castán Broto. 2013. “Government by Experiment? Global Cities and the Governing of Climate Change.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 38 (3): 361–375. doi:10.1111/j.1475-5661.2012.00535.x.

- Bulkeley, H., L. Coenen, N. Frantzeskaki, C. Hartmann, A. Kronsell, L. Mai, S. Marvin, et al. 2016. “Urban Living Labs: Governing Urban Sustainability Transitions.” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 22: 13–17. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2017.02.003.

- Bulkeley, H., S. Marvin, Y. Palgan, K. McCormick, M. Breitfuss-Loidl, L. Mai, T. von Wirth, and N. Frantzeskaki. 2019. “Urban Living Laboratories: Conducting the Experimental City?” European Urban and Regional Studies 26 (4): 317–335. doi:10.1177/0969776418787222.

- Bylund, J., J. Riegler, and C. Wrangsten. 2020. “Are Urban Living Labs the New Normal in co-Creating Places?” In Co-Creation of Public Open Places. Practice – Reflection – Learning, edited by C. Smaniotto Costa, M. Mačiulienė, M. Menezes, and B. Goličnik Marušić, 17–21. Lisbon: Lusófona University Press.

- Calvaresi, C., and L. Cossa. 2013. “A Neighbourhood Laboratory for the Regeneration of a Marginalised Suburb in Milan: Towards the Creation of a Trading Zone.” In Urban Planning as a Trading Zone, edited by A. Balducci and R. Mäntysalo, 95–109. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Caprotti, F., and R. Cowley. 2017. “Interrogating Urban Experiments.” Urban Geography 38 (9): 1441–1450. doi:10.1080/02723638.2016.1265870.

- Chesbrough, H. 2003. Open Innovation. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- Chronéer, D., A. Ståhlbröst, and A. Habibipour. 2018. “Towards a Unified Definition of Urban Living Labs.” ISPIM Innovation Symposium, 1–13, Manchester. https://search.proquest.com/docview/2076295160/abstract/C436365E60044007PQ/1

- Davidoff, P. 1965. “Advocacy and Pluralism in Planning.” Journal of the American Institute of Planners 31 (4): 331–338. doi:10.1080/01944366508978187.

- Dell’Era, C., and P. Landoni. 2014. “Living Lab: A Methodology Between User-Centred Design and Participatory Design.” Creativity and Innovation Management 23 (2): 137–154. doi:10.1111/caim.12061.

- EC. 2015a. Towards an EU Research and Innovation Policy Agenda for Nature-based Solutions & Re-Naturing Cities. Brussels: EC.

- EC. 2015b. “Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economicand Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions.” Closing the Loop – An EU Action Plan for the Circular Economy. European Commission, Brussels.

- Evans, J. 2011. “Resilience, Ecology and Adaptation in the Experimental City.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 36 (2): 223–237. doi:10.1111/j.1475-5661.2010.00420.x.

- Frantzeskaki, N., S. Borgström, L. Gorissen, M. Egermann, and F. Ehnert. 2017. Nature-Based Solutions Accelerating Urban Sustainability Transitions in Cities: Lessons from Dresden, Genk and Stockholm Cities, 65–88. Germany: Springer. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:kth:diva-214441

- Friedmann, J. 1993. “Toward a Non-Euclidian Mode of Planning.” Journal of the American Planning Association 59 (4): 482–485. doi:10.1080/01944369308975902.

- Galison, P. 1997. “Material Culture, Theoretical Culture and Delocalization.” In Science in the Twentieth Century, edited by J. Krige and D. Pestre, 669–682. Paris: Harwood.

- Healey, P. 1997. Collaborative Planning: Shaping Places in Fragmented Societies. London: Macmillan International Higher Education.

- Hillier, J. 2003. “Agon’izing Over Consensus: Why Habermasian Ideals Cannot be Real’.” Planning Theory 2 (1): 37–59. doi:10.1177/1473095203002001005.

- Juujärvi, S., and K. Pesso. 2013. “Actor Roles in an Urban Living Lab: What Can We Learn from Suurpelto, Finland?” Technology Innovation Management Review 3: 22–27. November 2013: Living Labs. doi:10.22215/timreview/742.

- Karvonen, A., and B. Van Heur. 2014. “Urban Laboratories: Experiments in Reworking Cities.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 38 (2): 379–392. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12075.

- Katsou, E., C. Nika, D. Buehler, B. Marić, B. Megyesi, E. Mino, J. Babí Almenar, et al. 2020. “Transformation Tools Enabling the Implementation of Nature-based Solutions for Creating a Resourceful Circular City.” Blue-Green Systems 2 (1): 188–213. doi:10.2166/bgs.2020.929.

- Klosterman, R. 1985. “Arguments for and Against Planning.” Town Planning Review 56 (1): 5–20. doi:10.3828/tpr.56.1.e8286q3082111km4.

- Lafortezza, R., and G. Sanesi. 2019. “Nature-based Solutions: Settling the Issue of Sustainable Urbanization.” Environmental Research. http://agris.fao.org/agris-search/search.do?recordID=US201900104251

- Lindblom, C. 1959. “The Science of Muddling Through.” PublicAdministrationReview 19 (2): 79–88. https://doi.org/10.2307/973677

- Marvin, S., H. Bulkeley, L. Mai, K. McCormick, and Y. Palgan. 2018. Urban Living Labs: Experimenting with City Futures. London: Routledge.

- Mäntysalo, R., A. Balducci, and J. Kangasoja. 2011. “Planning as Agonistic Communication in a Trading Zone: Re-Examining Lindblom’s Partisan Mutual Adjustment.” Planning Theory 10 (3): 257–272. doi:10.1177/1473095210397147.

- Mäntysalo, R., and V. Kanninen. 2013. “Trading Between Land use and Transportation Planning: The Kuopio Model.” In Urban Planning as a Trading Zone, edited by A. Balducci and R. Mäntysalo, 57–73. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Mensink, W., F. Birrer, and B. Dutilleul. 2010. “Unpacking European Living Labs: Analysing Innovation’s Social Dimensions.” Central European Journal of Public Policy 4 (1): 60–85. ISSN: 1802-4866.

- Moroni, S. 2019. “Constitutional and Post-Constitutional Problems: Reconsidering the Issues of Public Interest, Agonistic Pluralism and Private Property in Planning.” Planning Theory 18 (1): 5–23. doi:10.1177/1473095218760092.

- Mouffe, C. 2000. The Democratic Paradox. London: Verso.

- Pekkola, S., N. Kaarilahti, and P. Pohjola. 2006. Towards Formalised End-user Participation in Information Systems Development Process: Bridging the Gap Between Participatory Design and ISD Methodologies, 21–30. New York: Association for Computing Machinery.

- Puerari, E., J. De Koning, T. Von Wirth, P. Karré, I. Mulder, and D. Loorbach. 2018. “Co-creation Dynamics in Urban Living Labs.” Sustainability 10 (6): 1–18. doi:10.3390/su10061893.

- Rizzo, A. 2017. “Managing the Energy Transition in a Tourism-Driven Economy: The Case of Malta.” Sustainable Cities and Society 33: 126–133. doi:10.1016/j.scs.2016.12.005.

- Rizzo, A., B. Ekelund, J. Bergström, and K. Ek. 2020. “Participatory Design as a Tool to Create Resourceful Communities in Sweden.” In Co-Creation of Public Open Places. Practice – Reflection – Learning, edited by C. Smaniotto Costa, M. Mačiulienė, M. Menezes, and B. Goličnik Marušić, 95–108. Lisbon: Lusófona University Press.

- Rizzo, A., and M. Galanakis. 2015. “Transdisciplinary Urbanism: Three Experiences from Europe and Canada.” Cities 47: 35–44. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2015.01.001.

- Rizzo, A., and M. Galanakis. 2017. “Problematizing Transdisciplinary Urbanism Research: A Reply to ‘Seeking Northlake’☆.” Cities 64: 98–99. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2016.11.001.

- Sager, T. 1999. “The Rationality Issue in Land-use Planning.” Journal of Management History 5 (2): 87–107. doi:10.1108/13552529910249869.

- Sager, T. 2019. “Populists and Planners: ‘We Are the People. Who Are You?’” Planning Theory 19 (1): 80–103. doi:10.1177/1473095219864692.

- Savini, F., and L. Bertolini. 2019. “Urban Experimentation as a Politics of Niches.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 51 (4): 831–848. doi:10.1177/0308518X19826085.

- Schaffers, H., M. Cordoba, P. Hongisto, T. Kallai, C. Merz, and J. Van Rensburg. 2007. “Exploring Business Models for Open Innovation in Rural Living Labs.” In 2007 IEEE International Technology Management Conference (ICE), June, 1–8. IEEE.

- Scholl, C., and R. Kemp. 2016. “City Labs as Vehicles for Innovation in Urban Planning Processes.” Urban Planning 1 (4): 89–102. doi:10.17645/up.v1i4.749.

- Schuurman, D. 2015. “Bridging the Gap Between Open and User Innovation?: Exploring the Value of Living Labs as a Means to Structure User Contribution and Manage Distributed Innovation.” Diss., Ghent University. http://hdl.handle.net/1854/LU-5931264

- Star, S., and J. Griesemer. 1989. “Institutional Ecology, Translations’ and Boundary Objects: Amateurs and Professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907–39.” Social Studies of Science 19 (3): 387–420. doi:10.1177/030631289019003001.

- Ståhlbröst, A. 2008. “Forming Future IT – The Living Lab Way of User Involvement.” Doctoral diss., Luleå tekniska universitet.

- Ståhlbröst, A., and B. Bergvall-Kåreborn. 2013. “Voluntary Contributors in Open Innovation Processes.” In Managing Open Innovation Technologies, 133–149. Berlin: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-31650-0_9

- Steen, K., and E. van Bueren. 2017. “The Defining Characteristics of Urban Living Labs.” Technology Innovation Management Review 7 (7): 21–33. doi:10.22215/timreview/1088.

- Taylor, N. 1998. Urban Planning Theory Since 1945. Sage. http://doi.org/10.4135/9781446218648

- Veeckman, C., & S. van der Graaf. 2015. "The City as Living Laboratory: Empowering Citizens with the Citadel Toolkit." Technology Innovation Management Review 5 (3): 6–17. http://doi.org/10.22215/timreview/877

- Voytenko, Y., K. McCormick, J. Evans, and G. Schliwa. 2016. “Urban Living Labs for Sustainability and Low Carbon Cities in Europe: Towards a Research Agenda.” Journal of Cleaner Production 123: 45–54. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.08.053.

- Willis, K., and A. Aurigi. 2020. The Routledge Companion to Smart Cities. New York: Routledge.

- Woodhead, R., P. Stephenson, and D. Morrey. 2018. “Digital Construction: From Point Solutions to IoT Ecosystem.” Automation in Construction 93: 35–46. doi:10.1016/j.autcon.2018.05.004.