ABSTRACT

Despite the normative view that Quadruple Helix collaborations (with government, academia, industry and civil society) such as living labs are prescribed to enhance regional innovation performance, there is scarce knowledge of the sustainability of such collaborations from the perspective of the stakeholders who are supposed to engage in such initiatives. To address this gap, the purpose of this paper is to empirically explore the implementation of the Quadruple Helix for innovation from a stakeholder perspective, by understanding the expectations as well as the perceived benefits and challenges of the collaboration. Through a qualitative research design, this paper presents an in-depth case study of a living lab in the region of Catalonia. Our results challenge the normative view of Quadruple Helix approaches and of living labs; we also offer suggestions to manage future collaborations and to inform further evidence-based policy. On the whole, partnership leadership and coordination are critical to bridge the expectation-implementation gap towards stakeholder satisfaction and collaboration sustainability.

Introduction

Regional innovation systems (RISs) have been widely stylized as the intertwining of several helices (Carayannis et al. Citation2018). Among them, the Triple Helix is a well-established model of innovation, which encourages interaction among academia, industry and government (Etzkowitz and Leydesdorff Citation2000). This model is based on an underlying assumption of a dynamic and unstable equilibrium, in which there are likely tensions between two partners, and associating with the third helix will help to resolve these tensions and sustain the collaboration (Benneworth, Smith, and Bagchi-Sen Citation2015; Etzkowitz Citation2008). Nevertheless, the effectiveness of the Triple Helix model has been increasingly questioned in innovation and regional development (McAdam and Debackere Citation2018). In this sense, the Quadruple Helix model offers to be an improvement on the Triple Helix one, as it addresses some of the tensions for which the latter cannot resolve, especially the lack of society involvement (Carayannis and Campbell Citation2012).

Developing a Quadruple Helix approach consists of engaging an additional type of participants in the process, who are often considered to be ‘civil society’ or ‘users’ (Arnkil et al. Citation2010; Grundel and Dahlström Citation2016). The aim of this enlarged collaboration is to make the ‘fourth helix’ explicitly participate in the process of knowledge generation and innovation in general; this is done for many reasons, not the least being that they are the ultimate users or beneficiaries of innovation (McAdam, Miller, and McAdam Citation2018). One of the advantages of the Quadruple Helix model is the combination of both top-down and bottom-up approaches, in which bottom-up initiatives strengthened by top-down programmes are believed to lead to the most successful results (Etzkowitz Citation2003). Furthermore, with the engagement of a wider set of participants in the innovation process, the Quadruple Helix may offer a diversity of innovation outcomes rather than only technology-driven innovation (Nordberg Citation2015).

The helix models have generally been used as an ‘ideal-type’ and normative framework for researchers and policymakers (Benneworth, Smith, and Bagchi-Sen Citation2015; Cai Citation2015), but several authors have acknowledged the gap between the theory and the real functioning – what in practice means the discrepancy between expectations about the collaboration and the actual performance (Oliver Citation1980) – which can create tensions while generating innovation (Fogelberg and Thorpenberg Citation2012). In the same vein, McAdam and Debackere (Citation2018) state that there is a need to investigate the real functioning and effective management of such collaborations, because Quadruple Helix collaboration should not be taken for granted (Vallance, Tewdwr-Jones, and Kempton Citation2020). Furthermore, some argue that Quadruple Helix research is still in its infancy (Galvao et al. Citation2019; Miller, McAdam, and McAdam Citation2018) and that most research has focused on exploring the Quadruple Helix at a macro regional level, highlighting the need for further research at the micro project and individual levels (Cunningham, Menter, and O’Kane Citation2018; Höglund and Linton Citation2018; Miller, McAdam, and McAdam Citation2018). To address these micro-level gaps, the purpose of this paper is to empirically explore the expectations and perceptions of stakeholders in an ongoing Quadruple Helix initiative under the living lab (LL) form. In particular, this paper addresses the following research question: ‘How do expectations and perceived performance influence stakeholders’ engagement in the Quadruple Helix collaboration, such as LLs?’

LLs attract interests from diverse fields and sectors (Mastelic, Sahakian, and Bonazzi Citation2015) and are supposed to be capable of providing multiple benefits to stakeholders. Yet, sustaining collaboration is still a challenge, as evidenced by the slowing down of some European LL initiatives (Schuurman Citation2015) and their high failure rate (Nesti Citation2017b). Therefore, understanding the participants’ expectations is vital if these practices are to be sustained (Puerari et al. Citation2018; Von Wirth et al. Citation2019).

In the next section, we present the theoretical background on the implementation of the Quadruple Helix via LLs by exploring their expectations and performance. Then, we describe the qualitative methodology used and the case study of an urban LL in the region of Catalonia. Next is the findings section, in which we describe and analyse the viewpoints of all Quadruple Helix stakeholders regarding the manifested expectations, benefits and challenges of the collaboration. A final section ends the article with the main discussion and overview of its theoretical contributions, policy implications and future research proposals.

Implementing the Quadruple Helix model through LLs

LL is a ‘practice-driven phenomenon’ with a large community of practitioners (predominantly in Europe), which may explain why it lacks a consistent and commonly accepted definition among scholars (Ballon and Schuurman Citation2015; Leminen Citation2015). A LL can be defined as a methodology that is oriented by two main ideas: involving users at an early stage of the innovation process and experimenting in a real-life context (Almirall and Wareham Citation2011; Rizzo, Habibipour, and Ståhlbröst Citation2021). LLs facilitate co-creation based on public-private-civic partnerships, which are latterly known as the Quadruple Helix (Hyysalo and Hakkarainen Citation2014). The concept of co-creation can be constructed from a conglomerate of disciplines and practices but often underlines the need for an active role of citizens, in addition to the classical Triple Helix actors (Marušić and Erjavec Citation2020). Co-creation in LLs is facilitated by creating inclusive public spaces of multiple stakeholders, experimenting with new policies, co-designing and testing new methods, and exploring new governance models outside the conventional research and innovation models to produce pragmatic solutions for urban challenges (Bylund, Riegler, and Wrangsten Citation2020). These processes aim to develop tangible innovations, such as designs and services, or intangible ones, such as the generation of concepts and ideas (Feurstein et al. Citation2008; Hossain, Leminen, and Westerlund Citation2019). In this vein, some scholars argue that LLs focus more on promoting discussion or dialogue to reach hybrid understandings among different participants and therefore, possibly produce innovation outputs, rather than target measurable outcomes (Rizzo, Habibipour, and Ståhlbröst Citation2021). It implies that the expectations and outcomes of LLs are likely to be diverse.

Expectations from LLs

A longitudinal literature search suggests that the expectations surrounding LLs have extended over time from solely having technological and commercial benefits for the private sector (e.g. Almirall and Wareham Citation2011; De Moor et al. Citation2010) to also offering public and social value for the public and civic sector (e.g. Bulkeley et al. Citation2019; Kronsell and Mukhtar-Landgren Citation2018). One plausible explanation for this broader expectation is a shift in the (European) RIS approach. The RIS concept has been used as a framework to analyse the differential innovativeness of regions (Asheim, Isaksen, and Trippl Citation2019), inspiring regional innovation policy questioning ‘one size fits all’ policy solutions (Tödtling and Trippl Citation2005). Several authors have called for more place-based and inclusive innovation processes where a variety of agents collaborate towards regional development (Tödtling, Trippl, and Desch Citation2021). Considering that LLs have become popular policy instruments, the more diverse participants in RISs there are, the more likely various expectations from LLs they hold.

Actually, LLs ‘have been said to offer multiple benefits to businesses, society and users’ (Hossain, Leminen, and Westerlund Citation2019, 986). For example, LLs contribute to product development and the market expansion of private companies by matching products and consumer demands, providing ideas for new products/services and quickening the product’s entry into the market (Almirall and Wareham Citation2011). Their capacity in organizing different stakeholders also assists public authorities in promoting entrepreneurial ecosystems (Rodrigues and Franco Citation2018) or in responding to urban challenges through experimental governance (Bulkeley and Castán Broto Citation2013; Voytenko et al. Citation2016). Regarding universities, they wish to join LLs to conduct research that addresses local challenges (Salomaa Citation2019) and to transfer knowledge more effectively from the university to regional business (Van Geenhuizen Citation2013). Lastly, citizens may expect both personal and social benefits when joining LLs or when doing co-creation to be more specific, depending on the purpose of the activities (Nesti Citation2017a). Acquiring knowledge, achieving a sense of belonging to the network, and developing ideas independently have been identified as the citizens’ main motivations (Gascó Citation2017).

The extant literature offers some insight into specific stakeholders’ expectations in terms of LL collaboration. We however contend that aligning these diverse needs is extremely complex in the local and regional context, where current research falls short in providing a holistic picture to address all of the participants’ expectations (Benneworth, Pinheiro, and Karlsen Citation2017; Gascó Citation2017; Höglund and Linton Citation2018).

From expectations to performance

Understanding the sources of stakeholder satisfaction is the basis for successful stakeholder engagement (Hietbrink, Hartmann, and Dewulf Citation2012). In a consumer or user context, satisfaction is commonly considered as an outcome of consumption, where the quality of products and services from the supply side is the main external determinant towards recipients’ evaluation (Cronin and Taylor Citation1992; Vigoda Citation2002). On the other side, satisfaction could be understood as a process where internal factors of consumers also play a role in their perception on results (Parker and Mathews Citation2001). ‘Expectancy disconfirmation theory’ (Oliver Citation1980) is an effort of combining these two dimensions of satisfaction attributable to both external outcomes (supply side) and internal processes (consumption side).

From this approach, stakeholder satisfaction in innovation collaboration is partly related to the discrepancy between the perceived performance and the initial expectations about collaboration outcomes. This discrepancy of expectations can be negative if performance is below the expectations, or it can be positive if the performance exceeds the expectations (Oliver and Burke Citation1999). Expectancy disconfirmation theory has been applied to several fields, initially in marketing for the private sector but then gradually expanding to public management in order to evaluate citizen satisfaction (e.g. Grimmelikhuijsen and Porumbescu Citation2017; Van Ryzin Citation2004). This theory, though, has not been explored in regional innovation collaboration research despite its advantage in recognizing how expectations, implementation performance, and the gap between them influence stakeholders’ satisfaction and participation.

Once LLs are established and functioning, stakeholders will interact with them to supply some types of assets or capital (e.g. financial, human, physical, social) and receive in turn outcomes, with similar or different nature. Most likely, the perceived outcomes are not going to perfectly match the original expectations of the collaboration. While the anticipated advantages of LLs are undeniable, especially with its participatory innovation approach focusing on connecting users and other actors in a real-life environment, concerns over LL implementation are also visible (Hyysalo and Hakkarainen Citation2014; Von Wirth et al. Citation2019; Voytenko et al. Citation2016). For one, simultaneously addressing societal, economic and environmental issues, which is expected by various stakeholders, is evidently challenging in practice (Mastelic, Sahakian, and Bonazzi Citation2015).

Methodology and case overview

Methodology

We adopt an exploratory qualitative approach to address the under-investigated research question and to develop new insights about this complex topic (Creswell Citation2013). An in-depth single case study has been chosen for three main reasons. First, it is useful in investigating the dynamics in single settings or examining complicated phenomena evolving over time (Eisenhardt Citation1989; Yin Citation2003), which is the case of the expectations and satisfaction of stakeholders in LL collaborations. Second, it is highly recommended for understanding behaviours in inter-sectional relationships in network studies (Halinen and Törnroos Citation2005). Finally, it is consistent with the call for micro-level and place-based analysis in Quadruple Helix collaborations (McAdam, Miller, and McAdam Citation2018).

Data were collected from the end of 2017 to early 2019, a period when most activities of the chosen case (Library Living Lab, hereafter referred as L3) were limited to permanent working group discussing to re-define its governance and (financial) sustainability model. This seemed to be a difficult transition moment for L3, yet was an ideal time to look back to what was achieved and learnt after approximately four years of planning and three years of implementation. Primary data comprise 12 semi-structured interviews (on average 65 min each) with 17 key stakeholders: academics at both management and research levels (identified as Aca1 to 6); five authorities at local, provincial and regional management levels in charge of innovation and public services (Gov1 to 5); four local residents (User1 to 4); and two innovation managers in large companies (Ind1 and 2). Interviewees were recruited based on a snow-ball technique, in which active participants in the LL recommended the partners for interviewing. Thanks to this snow-ball technique, we are confident that the research has included the majority of significant stakeholders and the number of interviewees revealed quite properly the engagement level of the four helices in the LL activities.

All interviews, except for two upon request of the interviewed, were recorded and transcribed. We adopted a thematic analysis technique, a foundation of qualitative analysis, due to its flexibility in categorizing themes (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). Nvivo12 software was used to assist in data organization and analysis. Accordingly, narratives of interviewees were coded chronologically following three main themes: initial expectations, achieved benefits and identified challenges. We synthesized and compared for all helices repeatedly. Furthermore, we triangulated the empirical data with secondary documents and through several visits to the premise, including observation and participation in some L3 activities (). Secondary data, especially documents at the early stage of LL operation and its webpage, were also valuable in understanding the communication that partially set the stakeholders’ expectations.

Table 1. Complementary data sources (to interviews).

Case overview

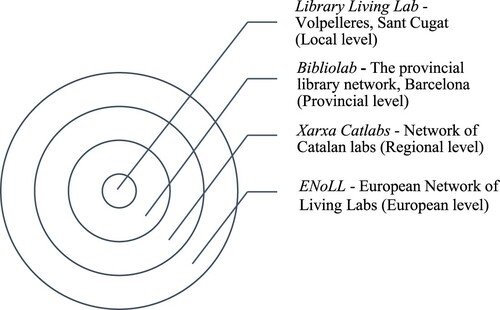

Our chosen case study is L3, which makes part of a public library in Volpelleres, the neighbourhood of Sant Cugat del Vallès, in a close radius of Barcelona, Catalonia (Spain). L3 describes itself as ‘an open, participatory, experimentation and co-creation space’ aiming to create links among culture, technology and society. The initiative seeks to explore how technology can transform users’ experience into new services and applications, thereby fostering research and innovation in the cultural domain. L3 is relevant in a broad context (). It is an outstanding case of multi-stakeholder collaboration with a Quadruple Helix approach and has been presented as a successful and promising project of being citizen-rooted. Yet L3 is also an example of the struggles involved in individual and inter-institutional collaboration (Vilariño, Karatzas, and Valcarce Citation2018).

The idea of setting up the L3 was born in the context of the neighbourhood construction stagnation in early 2010s, following 2008–09 financial crisis. At that moment, many promising projects got frozen and there was almost no activity offered to citizens in the area. A group of active residents was passionate about making the neighbourhood more innovative. They mobilized themselves under the Association of Residents of Volpelleres Neighbourhood (AVBV) and sought consultation from several academics of the Computer Vision Centre (CVC), located nearby in the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB) campus. Coincidentally, this research centre was looking for a model to realize their institutional strategy of transferring some research outcomes faster to the real world. These two collectives worked together on the proposal of L3, which was positively supported by the municipality of Sant Cugat. This initiative later gained attention from the Barcelona province aiming to promote its library network, and the UAB in the efforts to enhance their territorial impacts. These five stakeholders were committed enough to serve in the governance board of L3.

The LL welcomed users in October 2015, after the opening of the public library in May of the same year. 2016 was the most productive year of L3, while its activities visibly decreased in 2017 but then rebounded at the end of 2018. presents details of the LL stakeholders.

Table 2. Main Quadruple Helix stakeholders in L3.

Findings

This section presents the main findings regarding expectations from the LL collaboration, perceived benefits and challenges, according to the views of all four helices.

Expectations

The establishment and operation of L3 were facilitated by the initial positive expectations about its mutual benefits (). L3 represented a collective effort, in which local stakeholders voluntarily worked together to seek to address social challenges and further innovate the city. Most interviewees expected that the unique collaboration among stakeholders, who were ‘normally difficult to engage in the same consortium’ (Aca3) and supported by the novel participatory and experimental methodologies of LLs, would lead to a number of innovation projects. This collaboration also expectedly assisted each stakeholder in fulfilling their institutional missions as well as addressing their interrelated needs.

Table 3. Stakeholders’ expectations from the collaboration.

Initially, the municipality supported the initiative in accordance with the current norms on the democratization of knowledge and under the pressure of external stakeholders: ‘This library and the LL within the library were the demands from the neighbourhood. Any demand the citizens must be at least heard. And if it is reasonable, why don’t we promote this initiative?’ (Gov1). Local, provincial and regional governments then quickly realized that the LL could be a pilot initiative and an experimental place to improve public services, including museums and libraries, in the midst of ‘digital and technological changes leading to a decrease in number of users’ (Gov2). In the meantime, the city hall desired to ‘promote innovation projects transversally around the city’ (Gov1), and it was believed that the LL could support the creativity and entrepreneurship of citizens in the long term.

Concerned with improving the neighbourhood’s well-being, the CSO instigator of L3 shared some expectations with the governments and felt strongly entitled to influence local decisions in providing its residents with public innovative places. Upon L3’s opening, the dominant group of users were local residents, mostly employees of surrounding companies. They expected to pursue their personal interests by accessing physical resources (e.g. a 3D printer) and networking with people (e.g. sharing information among peers with the same hobbies and/or complementary skills) via various LL activities:

One day, I was bringing my kids to do homework here, and then I just walked by and saw people with a 3D printer. I thought: ‘Oh, what is this? I like this hobby’. Later I came and found out this is the place to build car models and to talk about these things. (User4)

From the academia side, supporting LL was driven by an institutional strategy of both the research centre and university. As proposers of the LL idea, they conveyed its prospect as a ‘vehicle’ to efficiently transfer technology and create impacts through developing innovation with different stakeholders. The idea derived from the need of having different transfer activities, particularly in the challenging cultural domain:

We are very very [emphasizing voice] close to industry, and we are doing a lot of technology transfer. […] The reasonable and easy ways to do technology transfer are license, contracts for research and contracts for companies. But there are different areas where creating impacts and transferring the results of our research are not so straightforward. One of them is culture. (Aca4)

Finally, both interviewees from the industry wished to approach end-users and customers directly for product development in the context of fast-changing buying habits and technological progress. The LL had potential in facilitating this access because it was typically challenging for the companies, as producers, to understand the customers’ needs through the perspectives of the distributors or retailers in their value chain, whose analysis was ‘not always with the same level of deepness that we [producers] would like’ (Ind2). In addition, one of the interviewees expected to capture value from the exploration side of innovation by means of giving supports to entrepreneurs’ new ideas. Nevertheless, the latter expectation was quite low based on a previous negative experience in another initiative, where they did not get any value and thus looked for more proactive behaviours from other partners: ‘We can place a 3D printer there, but then they [lab managers and users] have to manage and explore its application’ (Ind2).

Benefits

L3 brought several benefits to each partner, with the lowest positive level perceived by industry (). The first year of LL operation sought to create projects in which they ‘basically tested out different ways to do the idea of Quadruple Helix because everybody speaks about it, but not many people have actually implemented it’ (Aca4). Accordingly, most of the interviewees appreciated L3’s advantage in terms of the institutional learning regarding the needs and working dynamics of other sectors thanks to the proximity with them: ‘It is mainly mutual learning, we learnt to understand each other’ (Gov4). This learning process also helped participants, especially knowledge institutes, to better communicate and explain themselves to the community, following the encouragement of European Union’s research and innovation programmes (e.g. Horizon 2020):

With the interactions with other actors in the LL, we are improving our communication and our how-to. We are getting close to doing something together; so for me, that’s something that we are gaining; we are learning. It’s very important for us to do work with other helices. (Aca1)

Table 4. Collaboration benefits.

Citizens reaffirmed the accomplishments: ‘I didn’t remember the last time I came to a library. If it wasn’t for the LL, maybe I wouldn’t be here’ (User1), and ‘it’s a nice use of the library’ (User3). All interviewees agreed that the LL fulfilled their interests and further reinforced the connection of the local community. They were able to produce their own products using the available equipment with course instructors, share activities with their family members and get closer to other local residents through courses and other events. It was ‘more useful coming here [to L3] for an hour than spending one day at home’ (User1). The presence of L3 appeared to improve the local living conditions.

From the academia side, the mentioned benefits from L3 included data collection, research outputs (e.g. doctoral theses) and other academic activities (e.g. seminars). Researchers were better enabled to spread their knowledge and to review the research implication through gaining outsider opinion in LL activities (e.g. public debates). The participating researchers explained: ‘The community has more knowledge and are more accepting of what we do, and they encourage it; it’s a kind of benefit’ (Aca6). According to them, participating in these public engagement sessions also brought ‘satisfaction of helping’ or ‘self-fulfilment in impacting the community’. With the assistance of a facilitator from their institution, researchers expressed that it was feasible for them to participate in these public engagement activities.

Industry in turn found it difficult to obtain relevant benefits under the current form of the LL. However, since the companies’ branch name was recognized by users, participating in the LL was reputationally positive.

Challenges

Despite the perceived benefits, respondents indicated that expectations on entrepreneurship growth and industry engagement via experiments and testing had yet to be realized. Industry engagement had been inconsistent and the lowest among all stakeholders. Ongoing activities were also subject to several challenges. outlines the stakeholders’ concerns.

Table 5. Collaboration challenges.

Each stakeholder faced their own challenges. Participating public authorities referred to their internal challenge of fitting L3 activities into their organizational activities or their regular responsibilities of their staff: ‘Someone in the staff has to learn that; it’s a new task, a new programme for a member of our team. And yes, it’s a complicated issue because we have a lot of work’ (Gov5). Citizens, as the daily users, struggled in receiving timely support and responses related to the utilization of the LL resources. According to them, ‘every party focuses on their part’ (User3), and ‘there are a lot of interests, nobody has dedicated to our problems’ (User2). Regarding individual researchers, one of their challenges appeared to be how to prioritize upcoming activities. Their presence in L3’s public engagement sessions depended on whether they ‘would have time to join or not’ (Aca5), considering these sessions brought ‘more personal benefit than professional one’ (Aca6). One of the concerns from industry was the replication and scalability of the LL model, as a regional initiative to a more global practice: ‘We want something that can be scaled up globally; we don’t want to limit ourselves to the people here’ (Ind2).

Regarding shared concerns, they referred mainly to the difficulties in LL activity initiation, the weak strategy and legal framework and a lack of effective communication, which will be analysed in the following sections.

Difficulty in activity initiation

Most of the interviewees pointed out how they struggled to initiate L3 collaborative projects proven by an interrupted time without activities just one year after their opening. Although the activities started again later, the discontinuity undermined the interests of both current and potential partners. Some interviewees emphasized the need of having ‘different activities, not more [typical] activities’ (Gov3) because there was ‘not enough input to make people want to do more’ (User2). One representative from academia summarized the situation:

I think that in the beginning, we were a little bit naive because we expected a lot of things […] that it could be very easy to create a new project and to interact with the citizens, with the users of the library. But it is very difficult because it’s a process where we are learning about how to explain ourselves, how to explain to create a new model of education. (Aca1)

It is very difficult because we don’t have a white paper on this methodology. (Aca4)

From our sector, it is very difficult to understand this [the LL], and until this day, it is still not clear for us because we do not see it. It has been a year and a half since I was told this, and I do not really see what’s happening. (Gov3)

Coming from the history and art worlds, it was very difficult to understand the potential of a LL for us […] to define a project. Because it was like speaking in different languages. (Gov5)

It is difficult to collaborate with the university, because some departments or groups […] are too dynamic. They want to change the strategy too quickly. […] Also, students and professors are changing all the time. So it’s difficult for those departments to have a continuity in their team and their lines of research. (Gov5)

The dynamics of how the LL like this was created is difficult to co-align with the dynamic of companies. The companies don’t want things that happen in five years; they want things would be much faster. (Aca3)

We have seen that we need to foster this [citizenship] participation, it’s not a spontaneous collaboration. […] And this is the difficulty of managing this LL: defining the point of interest of these four stakeholders with their own languages and interests. It’s possible but it’s not easy. And we are here still nowadays working on it. (Gov1)

Weak strategy and legal framework

The lack of a clear strategy was the probable cause for some interviewees finding it problematic to measure the LL performance to continue engagement:

Nowadays, our concern is just to explain it was a good investment, but it’s difficult to explain […] It's more difficult to evaluate the return. And perhaps the long-term goal is to explain to our colleagues, to the citizens, the importance of a resource like this [LL]. (Gov1)

Since I invest money, I need some types of monitoring, some types of indicators to evaluate how this project is performing. And I am always asking what’s the number of users, of projects, of companies. (Aca1)

Finally, the absence of an official contract or ‘a legal document’ could also explain the low level of industry participation, considering their concerns about finance, confidentiality, and IP protection.

They [large companies] were here, but we didn’t have the chance to tight them because we didn’t have the contract. (Aca4)

Especially with new ventures with many partners, everyone is worried about who is going to own the patent. […] It can take ages. (Ind1)

The company has always been working on protecting intellectual property. […] We try to keep the IP inside and sometimes limit the collaboration. (Ind2).

Lack of effective communication

Citizens expressed their concern about the L3’s insufficient communication to both potential and current users: ‘I’m not sure if people know this place exists, because there is not a lot of news, advertising’ (User1). Information on LL activities was mainly circulating informally among users: ‘If it were not to be WhatsApp group [among users], I could hardly know what is going on, hardly’ (User3).

The lack of a proper communication might also be the reason why some activities did not reach sufficient audience or the desired citizens:

I am a bit disappointed to see that a big part of the people that went there were already part of research community and that there were only a few people who were not actually from our field. […] I hope that this spreads the word, and people start coming because that would be useful for us. (Aca5)

Discussion and conclusions

Our findings suggest that expectations reasonably explain the engagement of stakeholders in the mobilization phase. These expectations are shaped by three main premises: LL concept perception, context evaluation (Clarke and Fuller Citation2010) and prior experience (Oliver Citation1980). In this case, partners with high expectations (i.e. civil society, academia and governments) joined with greater apparent commitment. Their enthusiasm derived from the first two premises. First, these partners were persuaded by the theoretical promises of Quadruple Helix in general, and LLs as the particular instrument, in producing regional development and innovation while fulfilling individual partner needs. Second, they perceived the geographical context with the right preconditions to implement the LL collaboration; counting with pioneering public institutions, engaged knowledge institutes, an exceptional community of active and well-educated residents, and a large number of technological companies nearby. The remaining helix, industry, was the stakeholder with weaker engagement in the LL, a finding which is consistent with previous research (Gascó Citation2017; Voytenko et al. Citation2016). However, our research offers a deeper explanation for this finding, which is industry’s lower expectations of the collaboration, based on negative previous experiences. As a compromise to reduce their concern, industry wished for a formal collaboration and asked for official contracts right from the beginning. Industry was also oriented to outputs more than processes of understanding and dialogue (Rizzo, Habibipour, and Ståhlbröst Citation2021).

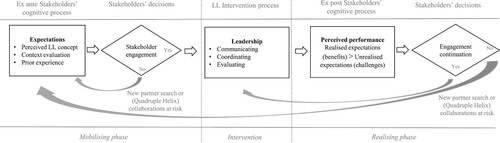

When it comes to continuing LL collaboration, stakeholders assessed their actual outcomes in the realization phase. We called benefits to the realized expectations, which are incentives for further stakeholder engagement, and unrealized expectations were analysed as challenges. The logic and main findings of this research can be represented as the cognitive and decision process of stakeholders in . The process includes a continuous cycle of a first mobilizing phase where expectations are determinants for stakeholder engagement, followed by an intervention phase of LL functioning where communication, coordination and evaluation are managed, and finally, a realizing phase when stakeholders evaluate their experience including a comparison with expectations to decide their engagement continuation.

In this case, the LL outcomes and performance were partly consistent with the stakeholders’ expectations in the short term, but there were also relevant unachieved ones, such as entrepreneurship growth. They possibly caused dissatisfaction among the stakeholders that eroded their interest in continuing the collaboration. Most observed interactions in the LL were in the form of education and learning, while the core part of the LL concept as communicated, such as experimenting in real-life contexts, had not really been implemented. Accordingly, stakeholders perceived insufficient new and varied innovation projects. One explanation could be that ‘experiment’ remains a vague and broad concept leading to different interpretation among partners. Only recently has the literature begun to question LLs’ purposes and implications, particularly their experimentation characteristic (Bulkeley et al. Citation2019; Rizzo, Habibipour, and Ståhlbröst Citation2021; Von Wirth et al. Citation2019). Although learning could serve as the first step to building partners’ capacity and identify citizens’ interest, our findings suggest that there is a need to have further experimental and co-creation activities or necessary resources to stimulate the entrepreneurial spirit.

Despite some frustration, the data revealed that governments, academia and civil society remained positive because they could obtain some benefits; at the same time, there was a shared understanding of the challenges facing stakeholders and a set of proposed solutions to be implemented. The positiveness demonstrates the advantages of governance structures in form of collaborative leadership as proposed in the literature and policies (Foray et al. Citation2012; Menny, Voytenko Palgan, and McCormick Citation2018). Nevertheless, the process has been time-consuming (and not always productive) in this case, considering the heterogeneity of stakeholders. Furthermore, representatives of these participants took the most important responsibilities in their home institutions, leaving citizens, as daily users, neglected. This situation requires ‘honest brokers’ or dedicated coordinators to accelerate the process of decision-making and user engagement activities (Palomo-Navarro and Navío-Marco Citation2018; Von Schnurbein Citation2010). We see here the importance of differentiating between steering and coordinating functions. While the governance board, as steering committee, has a role to play in navigating the partnerships, coordinators are responsible for smooth operations and building relationships with the stakeholders (Palomo-Navarro and Navío-Marco Citation2018).

Theoretical and empirical contributions

This article contributes to the extant literature on RISs, particularly the debate about citizen engagement under the Quadruple Helix model and LLs (Arnkil et al. Citation2010; McAdam and Debackere Citation2018). It is among the scarce number of studies offering a micro-level understanding of all four participants’ view. The article proposes a cognitive and decision-making model that can have both a descriptive and analytic use for theory and can also be informative for the practice of LL management. Its main conceptual originality is the extension of expectancy disconfirmation framework (Oliver Citation1980; Van Ryzin Citation2004), with an emphasis on the intervention of partnership governance and management, as orchestrators, which communicates and further bridges the stakeholder expectation gap to sustain the collaboration.

Taking a macro-level view, this research underscores the significance of the civil society, including citizens and CSOs, in stimulating the relevance of research, innovation and entrepreneurial discovery in the region (Bunders, Broerse, and Zweekhorst Citation1999; García-Terán and Skoglund Citation2018). The access to final users or citizens was found attractive to all stakeholders. Nevertheless, the engagement from industry in the case was extremely low, despite previous contacts and closeness with academia. The complexity of interactions, with conflicting logics and priority, challenges the straightforward extension from the Triple to Quadruple Helix as theoretically claimed, which ended not even in a functional Triple Helix collaboration. The transition to a Quadruple Helix does not function seamlessly in reality, as heroic efforts are required with a likely trade-off or compromise of value. Our empirical evidence resonates with a recent conceptual study, which argues that among the several ways to promote active citizenship, ‘simply following the path of extending RIS by a further dimension, for instance, civil society, is not promising’ (Terstriep, Rehfeld, and Kleverbeck Citation2020, 17).

Policy implications

The study is highly relevant to the contemporary discussion, as the smart specialization strategy, a keystone of European regional innovation policy since 2011, has been widely implemented and thus its practical evolution needs to be understood (Foray Citation2020). The core feature of this strategy is the entrepreneurial discovery process, which embraces a Quadruple Helix approach in collaborative leadership and experimental platforms to give voice to underrepresented actors in innovation systems (Foray et al. Citation2012). This research identifies the challenge of a common understanding of the LL concept and of experimentation itself. Policy should consider that experimentation may be understood at different levels, such as science or technology, types and nature of collaborations, entrepreneurial business models or citizens’ behaviour.

The article also highlights that institutional learning from place-based pilot projects may ease barriers of future collaborations. Yet one should be aware of the risk of stakeholders opting out in the next initiatives due to their sceptical attitudes towards the collaboration’s incentives and transaction costs. This suggests that policy design should avoid being idealistic (Flanagan and Uyarra Citation2016) whilst not lowering stakeholders’ expectations (Filtenborg, Gaardboe, and Sigsgaard-Rasmussen Citation2017; Grimmelikhuijsen and Porumbescu Citation2017). Overall, it is important to devise guidelines that assist regional actors in assessing and prioritizing their focus, including a consideration of both the benefits and challenges, to narrow the expectation versus implementation gap. It is particularly significant in the policy context to seek a transition to a voluntary RIS with territorial development strategies that go beyond industry-focused ones (Capello and Kroll Citation2016).

Limitations and future research

We realize that the small scale of our case study limits generalizability. However, the extant literature and practices call for more research on the micro-foundations of the Quadruple Helix, and in this article, we offer an exploration of the main sources that inform the stakeholders’ decisions to commit to a regional collaboration, such as LLs. A slight under-representation of industry following the characteristic of our case restricts the investigation based on the perception of few large companies. This invites further research on citizens inclusion from the views of other types of businesses, such as small and medium enterprises, in collaborations. In addition, innovation and entrepreneurship are long processes where evaluating their performances and stakeholder satisfaction would benefit from a longitudinal observation.

We also acknowledge that stakeholders’ durable engagement in a partnership requires their adaptable internal institutional arrangement (Vitale Citation2010). Hence, this article poses important questions about how each Quadruple Helix partner seeks to embed inclusive collaboration into their institutional level and gain benefits accordingly. Future studies could also explore the model that we propose and test if the arguments raised hold for other (local and regional) collaborations, especially in other settings. Quantitative approaches would also be applicable when theoretical propositions have become better developed.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Almirall, E., and J. Wareham. 2011. “Living Labs: Arbiters of Mid and Ground-level Innovation.” Technology Analysis and Strategic Management 23 (1): 87–102. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09537325.2011.537110.

- Arnkil, R., A. Järvensivu, P. Koski, and T. Piirainen. 2010. Exploring Quadruple Helix: Outlining User-oriented Innovation Models (University of Tampere: No. 85/2010).

- Asheim, B., A. Isaksen, and M. Trippl. 2019. Advanced Introduction to Regional Innovation Systems. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

- Ballon, P., and D. Schuurman. 2015. “Living Labs: Concepts, Tools and Cases.” Info 17 (4), info-04-2015-0024. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/info-04-2015-0024.

- Benneworth, P., R. Pinheiro, and J. Karlsen. 2017. “Strategic Agency and Institutional Change: Investigating the Role of Universities in Regional Innovation Systems (RISs).” Regional Studies 51 (2): 235–248. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2016.1215599.

- Benneworth, P., H. Smith, and S. Bagchi-Sen. 2015. “Special Issue: Building Inter-organizational Synergies in the Regional Triple Helix.” Industry and Higher Education 29 (1): 5–10. doi:https://doi.org/10.5367/ihe.2015.0242.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Bulkeley, H., and V. Castán Broto. 2013. “Government by Experiment? Global Cities and the Governing of Climate Change.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 38 (3): 361–375. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5661.2012.00535.x.

- Bulkeley, H., S. Marvin, Y. Palgan, K. McCormick, M. Breitfuss-Loidl, L. Mai, T. von Wirth, and N. Frantzeskaki. 2019. “Urban Living Laboratories: Conducting the Experimental City?” European Urban and Regional Studies 26 (4): 317–335. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776418787222.

- Bunders, J., J. Broerse, and M. Zweekhorst. 1999. “The Triple Helix Enriched with the User Perspective: A View from Bangladesh.” The Journal of Technology Transfer 24 (2–3): 235–246. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007811607384.

- Bylund, J., J. Riegler, and C. Wrangsten. 2020. “Urban Living Labs as the New Normal in Co-Creating Place?” In Co-Creation of Public Open Places. Practice – Reflection – Learning, edited by C. S. Costa, M. Mačiulienė, M. Menezes, and B. G. Marušić, 17–21. Lisbon: Lusofona University Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.24140/2020-sct-vol.4.

- Cai, Y. 2015. “What Contextual Factors Shape ‘Innovation in Innovation’? Integration of Insights from the Triple Helix and the Institutional Logics Perspective.” Social Science Information 54 (3): 299–326. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0539018415583527.

- Capello, R., and H. Kroll. 2016. “From Theory to Practice in Smart Specialization Strategy: Emerging Limits and Possible Future Trajectories.” European Planning Studies 24 (8): 1393–1406. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2016.1156058.

- Carayannis, E., and D. Campbell. 2012. Mode 3 Knowledge Production in Quadruple Helix Innovation Systems. SpringerBriefs in Business 7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-2062-0_1.

- Carayannis, E., E. Grigoroudis, D. Campbell, D. Meissner, and D. Stamati. 2018. “The Ecosystem as Helix: an Exploratory Theory-Building Study of Regional Co-Opetitive Entrepreneurial Ecosystems as Quadruple/Quintuple Helix Innovation Models.” R&D Management 48 (1): 148–162. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/radm.12300.

- Clarke, A., and M. Fuller. 2010. “Collaborative Strategic Management: Strategy Formulation and Implementation by Multi-Organizational Cross-Sector Social Partnerships.” Journal of Business Ethics 94 (1): 85–101. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0781-5.

- Creswell, J. 2013. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and mix Methods Approaches. 4th ed. London: SAGE.

- Cronin, J., and S. Taylor. 1992. “Measuring Service Quality: A Reexamination and Extension.” Journal of Marketing 56 (3): 55–68. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1252296.

- Cunningham, J., M. Menter, and C. O’Kane. 2018. “Value Creation in the Quadruple Helix: A Micro Level Conceptual Model of Principal Investigators as Value Creators.” R&D Management 48 (1): 136–147. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/radm.12310.

- De Moor, K., K. Berte, L. De Marez, W. Joseph, T. Deryckere, and L. Martens. 2010. “User-driven Innovation? Challenges of User Involvement in Future Technology Analysis.” Science and Public Policy 37 (1): 51–61. doi:https://doi.org/10.3152/030234210X484775.

- Eisenhardt, K. 1989. “Building Theories from Case Study Research.” The Academy of Management Review 14 (4): 532–550. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/258557.

- Etzkowitz, H. 2003. “Innovation in Innovation: The Triple Helix of University-Industry-Government Relations.” Social Science Information 42 (3): 293–337. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026276308287.

- Etzkowitz, H. 2008. The Triple Helix: University–Industry–Government Innovation in Action. New York: Taylor & Francis.

- Etzkowitz, H., and L. Leydesdorff. 2000. “The Dynamics of Innovation: From National Systems and “Mode 2” to a Triple Helix of University–Industry–Government Relations.” Research Policy 29 (2): 109–123. doi:https://doi.org/10.22503/inftars.XVII.2017.4.2.

- Feurstein, K., A. Hesmer, K. Hribernik, T. Thoben, and J. Schumacher. 2008. “Living Lab: A New Development Strategy.” In European Living Labs – A New Approach for Human Centric Regional Innovation, edited by Jens Schumacher, 1–14. Berlin: Wissenschaftlicher.

- Filtenborg, A., F. Gaardboe, and J. Sigsgaard-Rasmussen. 2017. “Experimental Replication: An Experimental Test of the Expectancy Disconfirmation Theory of Citizen Satisfaction.” Public Management Review 19 (9): 1235–1250. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2017.1295099.

- Flanagan, K., and E. Uyarra. 2016. “Four Dangers in Innovation Policy Studies – and How to Avoid Them.” Industry and Innovation 23 (2): 177–188. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13662716.2016.1146126.

- Fogelberg, H., and S. Thorpenberg. 2012. “Regional Innovation Policy and Public-Private Partnership: The Case of Triple Helix Arenas in Western Sweden.” Science and Public Policy 39 (3): 347–356. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scs023.

- Foray, D. 2020. “Six Additional Replies – One More Chorus of the S3 Ballad.” European Planning Studies 28 (9): 1685–1690. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2020.1797307.

- Foray, D., J. Goddard, X. Beldarrain, M. Landabaso, P. McCann, K. Morgan, C. Nauwelaers, and R. Ortega-Argilés. 2012. Guide to Research and Innovation Strategies for Smart Specialization (RIS3). Luxembourg. doi:https://doi.org/10.2776/65746.

- Galvao, A., C. Mascarenhas, C. Marques, J. Ferreira, and V. Ratten. 2019. “Triple Helix and its Evolution: A Systematic Literature Review.” Journal of Science and Technology Policy Management, 2053–4620. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/jstpm-10-2018-0103.

- García-Terán, J., and A. Skoglund. 2018. “A Processual Approach for the Quadruple Helix Model: The Case of a Regional Project in Uppsala.” Journal of the Knowledge Economy, doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-018-0521-5.

- Gascó, M. 2017. “Living Labs: Implementing Open Innovation in the Public Sector.” Government Information Quarterly 34 (1): 90–98. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2016.09.003.

- Grimmelikhuijsen, S., and G. Porumbescu. 2017. “Reconsidering the Expectancy Disconfirmation Model. Three Experimental Replications.” Public Management Review 19 (9): 1272–1292. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2017.1282000.

- Grundel, I., and M. Dahlström. 2016. “A Quadruple and Quintuple Helix Approach to Regional Innovation Systems in the Transformation to a Forestry-Based Bioeconomy.” Journal of the Knowledge Economy 7 (4): 963–983. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-016-0411-7.

- Halinen, A., and J-Å Törnroos. 2005. “Using Case Methods in the Study of Contemporary Business Networks.” Journal of Business Ethics 58 (9): 1285–1297.

- Hietbrink, M., A. Hartmann, and G. Dewulf. 2012. “Stakeholder Expectation and Satisfaction in Road Maintenance.” Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences 48: 266–275. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.06.1007.

- Höglund, L., and G. Linton. 2018. “Smart Specialization in Regional Innovation Systems: A Quadruple Helix Perspective.” R&D Management 48 (1): 60–72. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/radm.12306.

- Hossain, M., S. Leminen, and M. Westerlund. 2019. “A Systematic Review of Living Lab Literature.” Journal of Cleaner Production 213: 976–988. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.12.257.

- Hyysalo, S., and L. Hakkarainen. 2014. “What Difference Does a Living Lab Make? Comparing Two Health Technology Innovation Projects.” CoDesign 10 (3–4): 191–208. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2014.983936.

- Kronsell, A., and D. Mukhtar-Landgren. 2018. “Experimental Governance: The Role of Municipalities in Urban Living Labs.” European Planning Studies, doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2018.1435631.

- Leminen, S. 2015. “Q&A. What are Living Labs?” Technology Innovation Management Review 5 (9): 29–35. doi:https://doi.org/10.22215/timreview/928

- Marušić, B., and I. Erjavec. 2020. “Understanding Co-Creation Within Open Space Development Process.” In Co-Creation of Public Open Places. Practice – Reflection – Learning, edited by C. S. Costa, M. Mačiulienė, M. Menezes, and B. G. Marušić, 25–37. Lisbon: Lusofona University Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.24140/2020-sct-vol.4.

- Mastelic, J., M. Sahakian, and R. Bonazzi. 2015. “How to Keep a Living Lab Alive?” Info 17 (4): 12–25. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/info-01-2015-0012.

- McAdam, M., and K. Debackere. 2018. “Beyond ‘Triple Helix’ Toward ‘Quadruple Helix’ Models in Regional Innovation Systems: Implications for Theory and Practice.” R&D Management 48 (1): 3–6. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/radm.12309.

- McAdam, M., K. Miller, and R. McAdam. 2018. “Understanding Quadruple Helix Relationships of University Technology Commercialisation: A Micro-Level Approach.” Studies in Higher Education 43 (6): 1058–1073. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2016.1212328.

- Menny, M., Y. Voytenko Palgan, and K. McCormick. 2018. “Urban Living Labs and the Role of Users in Co-Creation.” GAIA – Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society 27: 68–77. doi:https://doi.org/10.14512/gaia.27.S1.14.

- Miller, K., R. McAdam, and M. McAdam. 2018. “A Systematic Literature Review of University Technology Transfer from a Quadruple Helix Perspective: Toward a Research Agenda.” R&D Management 48 (1): 7–24. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/radm.12228.

- Nesti, G. 2017a. “Co-production for Innovation: The Urban Living Lab Experience.” Policy and Society, 1–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2017.1374692.

- Nesti, G. 2017b. “Living Labs: A New Tool for Co-Production?” In Smart and Sustainable Planning for Cities and Regions, edited by A. Bisello, D. Vettorato, R. Stephens, and P. Elisei, 267–281. Cham: Springer.

- Nordberg, K. 2015. “Enabling Regional Growth in Peripheral non-University Regions—The Impact of a Quadruple Helix Intermediate Organisation.” Journal of the Knowledge Economy 6 (2): 334–356. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-015-0241-z.

- Oliver, R. 1980. “A Cognitive Model of the Antecedents and Consequences of Satisfaction Decisions.” Journal of Marketing Research 17 (4): 460–469. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378001700405

- Oliver, R., and R. Burke. 1999. “Expectation Processes in Satisfaction Formation: A Field Study.” Journal of Service Research 1 (3): 196–214. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/109467059913002.

- Palomo-Navarro, Á, and J. Navío-Marco. 2018. “Smart City Networks’ Governance: The Spanish Smart City Network Case Study.” Telecommunications Policy 42 (10): 872–880. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2017.10.002.

- Parker, C., and B. Mathews. 2001. “Customer Satisfaction: Contrasting Academic and Consumers’ Interpretations.” Marketing Intelligence & Planning 19 (1): 38–44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/02634500110363790.

- Puerari, E., J. De Koning, T. Von Wirth, P. Karré, I. Mulder, and D. Loorbach. 2018. “Co-Creation Dynamics in Urban Living Labs.” Sustainability 10 (6): 1893. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/su10061893.

- Rizzo, A., A. Habibipour, and A. Ståhlbröst. 2021. “Transformative Thinking and Urban Living Labs in Planning Practice: A Critical Review and Ongoing Case Studies in Europe.” European Planning Studies, doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2021.1911955.

- Rodrigues, M., and M. Franco. 2018. “Importance of Living Labs in Urban Entrepreneurship: A Portuguese Case Study.” Journal of Cleaner Production 180: 780–789. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.01.150.

- Salomaa, M. 2019. “Third Mission and Regional Context: Assessing Universities’ Entrepreneurial Architecture in Rural Regions.” Regional Studies, Regional Science 6 (1): 233–249. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2019.1586574.

- Schuurman, D. 2015. Bridging the Gap Between Open and User Innovation? Exploring the Value of Living Labs as a Means to Structure User Contribution and Manage Distributed Innovation. Ghent University & Vrije Universiteit Brussel. https://biblio.ugent.be/publication/5931264/file/5931265.pdf

- Terstriep, J., D. Rehfeld, and M. Kleverbeck. 2020. “Favourable Social Innovation Ecosystem(s)?–An Explorative Approach.” European Planning Studies, doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1708868.

- Tödtling, F., and M. Trippl. 2005. “One Size Fits All?: Towards a Differentiated Regional Innovation Policy Approach.” Research Policy 34 (8): 1203–1219. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2005.01.018.

- Tödtling, F., M. Trippl, and V. Desch. 2021. New Directions for RIS Studies and Policies in the Face of Grand Societal Challenges. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2021.1951177.

- Vallance, P., M. Tewdwr-Jones, and L. Kempton. 2020. “Building Collaborative Platforms for Urban Innovation: Newcastle City Futures as a Quadruple Helix Intermediary.” European Urban and Regional Studies, 1–17. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776420905630.

- Van Geenhuizen, M. 2013. “From Ivory Tower to Living Lab: Accelerating the Use of University Knowledge.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 31 (6): 1115–1132. doi:https://doi.org/10.1068/c1175b.

- Van Ryzin, G. 2004. “Expectations, Performance, and Citizen Satisfaction with Urban Services.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 23 (3): 433–448. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.20020.

- Vigoda, E. 2002. “From Responsiveness to Collaboration: Governance, Citizens, and the Next Generation of Public Administration.” Public Administration Review 62 (5): 527–540. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6210.00235.

- Vilariño, F., D. Karatzas, and A. Valcarce. 2018. “The Library Living Lab: A Collaborative Innovation Model for Public Libraries.” Technology Innovation Management Review 8 (12): 17–25. doi:https://doi.org/10.22215/timreview/1202.

- Vitale, T. 2010. “Building a Shared Interest. Olinda, Milan: Social Innovation Between Strategy and Organisational Learning.” In Can Neighbourhoods Save the City? Community Development and Social Innovation, edited by F. Moulaert, F. Martinelli, E. Swyngedouw, and S. González, 81–92. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Von Schnurbein, G. 2010. “Foundations as Honest Brokers Between Market, State and Nonprofits Through Building Social Capital.” European Management Journal 28 (6): 413–420. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2010.06.008.

- Von Wirth, T., L. Fuenfschilling, N. Frantzeskaki, and L. Coenen. 2019. “Impacts of Urban Living Labs on Sustainability Transitions: Mechanisms and Strategies for Systemic Change Through Experimentation.” European Planning Studies 27 (2): 229–257. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2018.1504895.

- Voytenko, Y., K. McCormick, J. Evans, and G. Schliwa. 2016. “Urban Living Labs for Sustainability and Low Carbon Cities in Europe: Towards a Research Agenda.” Journal of Cleaner Production 123: 45–54. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.08.053.

- Yin, R. 2003. Case Study Research. Design and Methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.