ABSTRACT

Spatial planning as a field in continuous transition needs a way of working that allows for questioning its professional practice. In this paper, we focus on the design of 4-days long ‘studios’ for planning professionals that aim to reflect on new notions of democratic practice and participatory planning. During these studios, different methods to enhance a collective reflective attitude among participants were tested. The paper describes how the tutors of the studios tried to encourage participants to develop their own theory of practice by iteratively (re)designing the learning artefacts, learning content and learning modes of the studio. In the conclusions of this paper, we introduce the idea of a Participation Studio Conjecture Map to support and structure a culture of collective reflection-in (participatory planning) organizations.

1. Critical reflection on professional practice

The work of Donald Schön and more specifically, his concept of the reflective practitioner (Schön Citation1983; see also Argyris and Schön Citation1978; Fischler Citation2012; Kadlec Citation2006) and the idea of reflection-in-action has already for a long time been a popular concept in planning theory and practice (a.o. Bertolini et al. Citation2010; Scott Citation2019). In line with the pragmatic tradition in planning (Healey Citation2009; Friedmann Citation2008; Forester Citation1989, Citation1993; Innes Citation1995), reflective practice highlights the possibility to become attentive to, through action, the transformative potential of planning and its socio-political consequences.

Reflection-in-action starts from the competence of planning practitioners to reflect on the room for manoeuvre of spatial practice or in the words of Forester ‘to routinely move behind the routine and look out for transformative potentials’ (Forester, Citation1989 in Healey Citation2009, 286). Following Argyris and Schön (Citation1996), this process of reflection can best be described by different levels of learning. In their work, Argyris & Schön distinguish single-loop and double-loop learning. Single-loop learning focuses on the management of problems and the factual knowledge and skills that are necessary to engage in the process of problem-solving. Double-loop learning explores the possibilities of questioning underlying values and assumptions and finding ways to translate these reflections into new mental frameworks and action. Through double-loop learning, participants explore ‘the assumptions that frame their understanding of the problems and search for responses to these problems’ (Goh Citation2019, 2).

Building upon the work of Argyris & Schön, several authors in planning theory (Forester Citation2013; De Leo and Forester Citation2017) and adult learning sciences (Bradbury et al. Citation2010; Goh Citation2019; Boud and Hager Citation2012; Wenger Citation1998) have been stressing that if the reflective practice should trigger double-loop learning and question underlying assumptions, it essentially depends on the collective nature of the endeavour. Learning in action should take both the experience of all the practitioners engaged in an activity and the socio-political context in which the activity occurs into account. By collectively reflecting on individual learners’ experience ‘practitioners can recognize and research the assumptions that undergird our thoughts and actions within relationships, at work, in community involvements, in avocational pursuits, and as citizens’ (Brookfield Citation2010, 216).

Collective reflective practice can happen in different settings and can take different forms (see Goh Citation2019 for an overview). Focussed on professional practice we understand collective reflection in line with Collin and Karsenti (Citation2011, 6) as ‘individual reflection in groups or with the presence of the ‘other’’. Put simply, collective reflection can be viewed as ‘practitioners belonging to either the same or different communities of practice, having shared interest and shared purpose, coming together to reflect on issues relevant to the improvement of work’ (Boud Citation2010, 34). The main challenge of this collective reflection is to provide an environment that allows practitioners to learn from each other by reflecting on their own professional practice experiences (DiSalvo et al. Citation2017; Beauchamp Citation2015). By doing so they can further develop their own theories of practice: the basis to evaluate and understand their own practice in relation to underlying (often shared) assumptions (Gardner Citation2014; Fook Citation2010).

In this paper, we want to reflect on the kind of environment that helps planning practitioners to collectively reflect-in-action. How can we make a collection of planners, who do not necessarily know each other, who are not involved in the same planning process, reflect on decisive transitions taking place in their profession? How can we encourage them to explore together the values and assumptions that shape their practical experiences? How can we train them to engage in both single- and double-loop learning and turn critical collective reflection into an inseparable part of the planning discipline?

2. Participation as collective learning

The collective reflective practice we describe and analyse in this paper focuses on transitions taking place within the domain of participatory planning. Over the last years, we see a double movement in participatory planning practices. While participatory trajectories are again becoming part of the professional planning standards (a.o. Kuhk et al. Citation2019) and self-organizational practices are more and more recognized as important drivers for socio-spatial transformation (a.o, Boonstra Citation2015; Boonstra and Rawls Citation2021), the transformative potential of deliberative democratic practice and its possibility to respond to existing networks of power, is questioned (Zakhour Citation2020; Metzger, Soneryd, and Linke Citation2017;Gualini Citation2015; Parker and Street Citation2015; Campbell, Tait, and Watkins Citation2014; Sager Citation2011).

In conversations with planning practitioners, we felt the need to reflect over these dynamics taking place within the field of participatory planning. Their contradictory insights fundamentally challenge planning practice to question underlying mechanisms and definitions of power, agency, democracy, representation and aligned concepts. To understand these underlying mechanisms of participatory practice requires planning practitioners to conceive participation as a set of processes of collective learning in which ‘(changing) groups of people actively and collectively try to (re)define and test how, why, what and in relation to who they are organizing themselves’ (De Blust, Devisch, and Schreurs Citation2019, 22).

In order to explore and engage with these processes of second-loop learning, we organized a series of five so-called ‘participation studios’ between 2018 and 2021. During these studios, we tried to collectively reflect on the transformative potential of participatory planning practice and related (practical) questions such as: how should we organize a participatory process that is truly open and inclusive? How to diversify the type of actors that participatory planning? How can we convince involved politicians to invest in a sustained participatory process? Or how can we stimulate self-organization? We organized these participation studios as experimental learning trajectories in line with what one of the pioneers of adult education research describes as

small groups of aspiring adults who desire to keep their minds fresh and vigorous; who begin to learn by confronting pertinent situations; who dig down into the reservoirs of their experience before resorting to texts and secondary facts; who are led in the discussion by teachers who are also seekers after wisdom and not oracles. (Lindeman Citation1926, 7)

Each studio was prepared in advance, with detailed scripts, presentations, exercises, and fill-in templates. But quite often, we had to leave aside our preparations. For instance, whenever we had the feeling that our approach was not triggering reflection, we adjusted it. Whenever we had the experience that something was working, we fine-tuned it. And whenever a participant came up with a proposal, we experimented with it. The result was an iterative process of both questioning grounding assumptions of democratic practice in participatory planning and collectively reflecting on new possible ways to respond to these new insights.

The dynamic of such a process is the result of at least three instances of collective learning (a) the collective learning within the chosen local participatory planning process as presented by the participants, (b) the collective learning trajectory that each of the studios has fostered among the participants and (c) the collective learning of the organizing team. In this paper, we focus on this last instance of collective learning and our endeavour to set-up an environment that allows practitioners to learn from each other by reflecting on their own experiences in professional practice.

The reason to focus on our own learning trajectory came from the observation that after three participation studios (2018–2020), we had the feeling that we developed a methodology for collective reflection without a clear understanding of the choices, discussions and design attempts that lead to its conception. In order to share and implement the methodology, we believed we needed a better understanding of its iterative design process and the key choices we made along the way: which of the choices were motivated by our observations that double-loop learning as a key level of learning for collective reflection could be further enhanced? Can we derive principles that would help spatial planners to reflect over transitions taking place in their daily practice and organizations?

3. Conjecture mapping

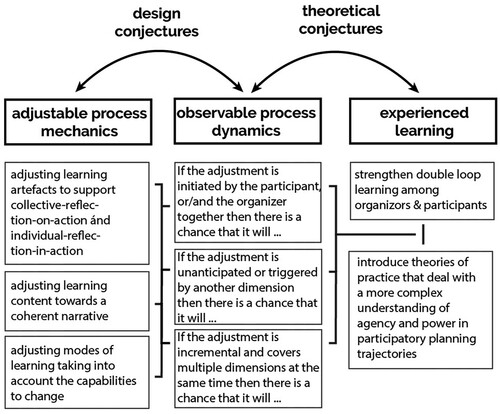

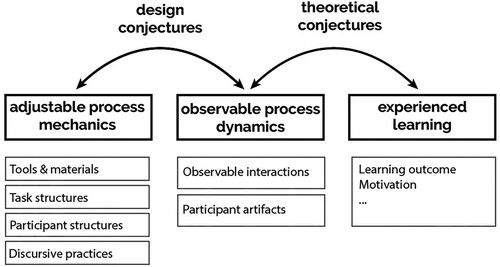

To analyse our own process of collective learning, we, as members of the organizing team, used the conjecture mapping model of Sandoval (Citation2014). This model helps to make the choices behind design decisions explicit by distinguishing three building blocks (): (1) the embodiment of a specific design (Sandoval Citation2014) or what we call the ‘adjustable process mechanics’: tools and materials, task structures, participant structures and discursive practices, (2) the mediating processes (Sandoval Citation2014) or what we call the ‘observable process dynamics’: the specific manifestations of collective reflection and interaction that we can observe as a result of adjusting our process mechanics and (3) the outcomes (Sandoval Citation2014) or what we call the ‘experienced learning’: the degree of learning that we assume took place during the observed process dynamics.

Figure 1. Conjecture mapping model (After Sandoval Citation2014).

The reasoning behind these three building blocks is that the process mechanics generate certain process dynamics that produce types of learning (Sandoval Citation2014, 21). Each time a design team adjusts the process mechanics, they have expectations regarding the dynamics that this change will generate. Sandoval refers to these expectations as ‘design conjectures’. These conjectures are complemented with ‘theoretical conjectures’ or the expectations a team has on how these dynamics will influence the degree of learning of its participants.

In this paper, the model of Sandoval was not actively used as a methodology to draft and question the design of our learning process but as an analytical heuristic for ex-post evaluation. As discussed, we felt the need after studio 3 to analyse our own learning trajectory. Inspired by the design decisions that were discussed during the preparatory meetings of the participation studios, we activated the model of Sandoval to analyse the empirical material we collected during the three participation studios (completed templates, homework, questionnaires, observation notes from the organizers and reports of preparatory meetings). In order to stay close to our initial process, we adapted some of the adjustable process dynamics of Sandoval’s model to better represent the design choices and discussions that were activated during our collaboration.

Tools & materials were taken together in a focus on ‘learning artefacts’, the task structure was replaced by a focus on ‘learning content’, analyzing the introduced frameworks of participatory practice and the participant structure and discursive practice were taken together in a focus on ‘forms of learning’, tracing how different group constellations were activated during the participation studios.

In this paper, we try to understand how the adjustment of one of these process mechanics (artefacts, content and mode of learning) influenced our understanding of how to create the right environment for collective reflection. We do this by reconstructing our Participation Studio Conjecture Map; a map that defines a hierarchy in the dimensions one can play with to tune an environment for collective reflection; that specifies how particular settings of these dimensions trigger particular learning dynamics; and that makes clear how particular dynamics either point at single or double-loop learning.

In the first part of the paper, we shortly introduce each of the participation studios. In three subsequent parts, we reconstruct our design conjectures for each studio and process mechanic separately. We code each adjustment based on the idea that each adjustment (what) is initiated by someone (who) and triggered by something (why). For each observed dynamic, we specify the learning experience and highlight if we experienced the adjustment as a moment of double-loop learning: in what way did we expect that the adjustment can lead to a (collective) reflection on the assumptions of participatory planning trajectories?

What lies beyond the focus of our empirical analysis is how the learning that was stimulated during the studios had a specific impact on the still-ongoing participatory practices and the professional actions of the participants. We did get indications of these learning effects in what participants told us in the subsequent session of a studio, for example, about how they started to approach their professional actions differently and what conversations they had had with colleagues about the changes they wanted to make. But an in-depth and nuanced insight into these learning effects requires a more focused and specific survey after the studios have been completed. Our choice in this research was entirely on properly mapping the learning opportunities during the studios and thus opening up the black box of this kind of continuing education initiatives for participatory planning practitioners.

In the conclusion of this paper, we compare the three participation studios and describe how conjecture mapping can help to better understand and develop processes of collective reflection-in professional practice. We describe how we used the learning environment, developed throughout the first three studios, in participation studio 4 and 5 and how this can support to introduce similar modes of collective reflection on participatory planning in the professional planning field.

4. Organizing three studios for collective reflection

In Studio 1, we agreed that each organizer, two academics and two practitioners, would be responsible for one day programme and would select the learning artefacts, content and modes that he/she considered appropriate. We assumed as theoretical conjectures that (1) the potential for DLL is higher in case a participant or a participant together with an organizer takes the initiative to adjust a process mechanic, (2) anticipated and triggers that belong to the same process mechanics have a lower potential for DLL, as these types of triggers typically only require minor, technical adjustments and (3) adjustments across multiple process mechanics might likely be the result of DLL.

In Studio 2, we decided to limit the number of learning artefacts, content and modes, and to use the studio to co-produce a coherent participatory planning narrative. To frame this narrative, we started the studio with our own definition of participation, namely, as a process of collective learning. During the studio, we invested quite some time in the development of learning artefacts that supported this coproduction process. Towards the end, we realized that our approach remained too abstract. Instead of spending so much time on the analysis of finished participatory trajectories, we should have asked the participants to bring ongoing trajectories in which we could try things out.

In Studio 3, we started with a coherent framework to both analyse and design participatory trajectories. We thought we found the ideal combination of learning artefacts, content and modes. The participants did also react enthusiastically, but to our surprise, on the last day, it turned that nobody seemed to have experienced DLL. They still asked us the same questions as on the first day. We decided to organize one extra session, during which we met with two of the participating organizations separately and worked on their participatory cases. Finally, things started to work.

A quick scan of the overall trajectory suggests that our learning artefacts evolved from isolated schemes into one coherent poster structured around a series of DIY exercises. Our learning content gradually grew from stand-alone concepts into one integrated, narrative on ‘participation as collective learning’. And our learning mode changed from mainly lecturing and inducing questions by externals in the first studio, to plenary discussion sessions in the second studio, to groupwork sessions in the third studio. In sum, we did make serious adjustments in all three process mechanics. Where two out of the three mechanics, learning artefacts and content, evolved in a clear direction, the third mechanic, learning mode, evolved in different directions. In order to understand how we expected these adjustments to strengthen DLL, we will look at the observable process dynamics in more detail.

4.1. Participation Studio Vlaams Brabant: a multitude of practical adjustments

summarizes the main adjustments that we made throughout our first studio. A first reading of the table suggests that we adjusted all process mechanics after the first studio-day. This feels quite logical, given that this was the first time that we organized such a studio. We mainly made practical adjustments: introducing a studio-book, collective sessions, etc. There was no time, or not enough shared experience yet, for deep reflections on the learning process. On the last studio-day, one of the participants told us that he made a presentation of what he learned throughout the studio and asked us if he could present it to the group. What he presented was a scheme that integrated the multitude of participatory concepts that we introduced. He talked about ‘an adjustable hourglass model’ and explained how participatory planners should learn to strategically manage the degree of co-creation during a participatory process. We interpreted this incident as a clear indication of DLL as this presentation was a serious attempt of a participant to integrate the ‘multitude’ that we, as organizers, provided and develop our own theory of practice. Based on his own experience, the participant selected frameworks that could help him to navigate across different perspectives on participatory planning. But, apart from this ‘incident’, none of the empirical data suggests that there was much DLL among the other participants, as they kept asking for a manual that they could share with their colleagues, puzzled by the open format of our studio.

Table 1. Reconstruction of participation studio Vlaams Brabant.

To reconstruct the design conjectures that guided our process design and understand which choices were motivated by our believe that double-loop learning could be further enhanced, we use three questions: who initiated each adjustment? Why did he/she do this? And what did he/she do?

Regarding ‘who’ initiated the adjustments, suggests that we, as organizers of the studio, mainly adjusted the learning artefacts (e.g. the introduction of a studio-book) and the learning mode (e.g. the introduction of collective reflection sessions). A lot of adjustments were made collectively, such as the decision that each participant would bring a participatory project that inspired him/her or the decision to each bring an inspiring participatory method. According to our theoretical conjectures, these collective initiatives trigger DLL. They certainly motivated the one participant to spontaneously draw up an insightful summary of everything he learned, in turn triggering us, the organizers, to be more explicit of our own perspective on participatory planning. This also means that in order for the participants to learn, we needed to make clear that we were also learning, that we were also trying to find out how different participatory cases and methods start from different assumptions on agency and power and how through collective reflection these can be traced.

Regarding ‘why’ these adjustments were made, a recurring trigger seemed to be the demand for extra clarifications from the participants. The participants struggled with the learning content, which was too ‘academic’ and the learning artefacts, which were not considered interactive enough and too remote from their daily planning practice. At the start of the studio, we anticipated this type of reaction. It was our first time, after all. But the participants kept on asking for manuals, up to the last day, despite adjustments such as the collective decisions to all bring in more cases and methods. We observed that bringing in more cases led to a shift from thinking in participatory moments to participatory processes and challenged the participants to reflect on their own actions but did not trigger the development of their own theories of practice. Going through all our empirical material () shows that there were, in fact, many triggers that could have led to DLL (e.g. we invited a pedagogue to participate in the studio in order to assess our approach), but it took us until the last studio-day to finally realize that we not only needed to adjust the learning artefacts and mode but also our learning content. We were mainly occupied with small technical adjustments like how to keep track of the notes of the participants, how to make the participants exchange experiences, etc. This prevented us from deeper reflection and more drastic adjustments.

Regarding ‘what’ changed, shows one adjustment that covers multiple mechanics, namely the decision, on the last studio-day, to invite external experts (learning mode) challenged the participants to make posters (learning artefacts) on which they had to summarize their lessons-learned. The table also shows two incremental adjustments. The first one was triggered by the recurring demand for extra clarifications, leading to the gradual introduction of more collective reflection moments. The second incremental adjustment was the decision (made during the collective evaluation at the end of the second studio-day) to ask the participants to bring their own cases, which later triggered the decision to discuss with the other participants the methods they already are using in their own participatory practices.

In sum, our unorganized multitude only seemed to trigger DLL with one of the participants; the one who spontaneously brought his own summary. If we look at from the perspective of the adjustable process mechanics, then it becomes clear that we made quite some adjustments, but that these hardly ever cover multiple mechanics. We did play around with the learning artefacts (e.g. from individual templates to one studio-book, to three studio-books) and we did change the learning mode (e.g. introduced collective reflection and evaluation moments). Some of these adjustments were iterative, but they never crossed mechanics, except on the last day where we asked the participants to develop posters (a new learning artefact) and present these to externals (a new learning mode). also shows that it was mainly us, the organizers, who introduced adjustments. The collective evaluations at the end of each studio-day did trigger some collective decisions, but these typically remained limited to practical improvements without generating deep collective insights. It took us until the final day, on which all triggers – the posters, the summary, the external experts, the collective evaluations – seemed to hint at an important insight, namely that what we were lacking was a coherent narrative on participatory planning; one that was in tune with the daily practices of the participants. More importantly, what we seemed to have realized, is that we needed to develop such a coherent narrative together with the participants.

4.2. Participation Studio Antwerpen: reflecting collectively on ongoing participatory trajectories

Based on our experiences with our first studio, we decided to introduce a more coherent focus in our unorganized multitude. As makes clear, we did introduce several adjustments on the first studio-day. The main adjustment was to start from an own definition of participation as collective learning (starting from the existence of different parallel coalitions of actions and the need to strategically navigate between them) and to use this definition to collectively question and deconstruct the participatory trajectories of the participants. We assumed that starting from an own working definition of participation instead of a loose set of methodological frameworks would help to directly introduce a different reading of participatory practice while giving them room to explore how this helps to trace and engage with power differences.

Table 2. Reconstruction of participation studio Antwerpen.

What also shows is that we kept on adjusting the process mechanics. This either means that our new approach did not work or that it did work, but that we kept on finding new ways to improve it.

What stands out after the first analysis of is that we agreed, on the second studio-day, to do every activity collectively. This was triggered by the unexpected absence of one-third of our participants and organizers on that day. It remained our learning mode for all the other studio-days. What also stands out is that we kept on adjusting our learning artefacts to make them truly interactive. Both these adjustments suggest that we were deliberately working, with the participants, on the writing of a coherent narrative, neatly in line with what we, at the end of our first studio, argued to be a precondition for DLL. also shows a third remarkable adjustment, namely the collective decision, also on the second studio-day, to allow one participant to bring in the participatory trajectory that she was engaged in at that moment. In the first studio, we asked the participants to only bring finished cases, in order to then look back and exchange experiences. The participants evidently did translate their insights to running cases, but they did this individually. From that second studio-day, all participants started bringing along ongoing participatory trajectories on which they then reflected collectively. This would later turn out to be a crucial adjustment.

Regarding ‘who’ initiated each adjustment, just like in the first studio, it only took until the second studio-day for the participants to propose changes. One of these collective decisions, namely, to discuss everything in the plenum, made it clear for the participants that we, as organizers, were also learning. This became very obvious as we simply could not answer all their questions. The recurring question was, for instance, how to introduce a more diverse group of people in participatory trajectories. We tried to answer it collectively by both discussing the possibility to approach a participatory process as a series of parallel trajectories, allowing to directly respond to a diversity of needs, and exploring different modes of non-violent communication to trace those needs and make them explicit.

The insight that the organizers were also there to learn, combined with the fact that we were a small group, made one of the participants feel confident enough to ask the group if they could help her with her ongoing participatory project. ‘We had a big event yesterday and things did not work out as expected. I have no idea what to do next’. We immediately agreed and saw it as an opportunity to make abstract concepts more tangible. At first, this spontaneous adjustment may read like an SLL reflex, a practical change in our approach, but as we will illustrate later, it turned out to be the start of a process of DLL.

Regarding ‘why’ we adjusted, makes clear that the lessons that we drew from our previous studio were our main trigger to introduce changes. Besides, there seem to have been quite some non-anticipated triggers, such as the absence of participants and organizers (on both day 2 and 3), the participant asking advice on her participatory case, a participant introducing the concept of participation culture, etc. Our initial theoretical conjecture was that these non-anticipated triggers form the ideal ground for DLL. Whether or not this was the case in this studio, we did embrace all these triggers and adjusted our process mechanics: we worked collectively, we dived into the ongoing case and discussed how to start changing the participatory culture of the organizations of which the participants were part. Note that, though these triggers might not be anticipated, they are related, with one trigger triggering the others. Working collectively created the right conditions for the participants to propose ongoing cases and introduce new concepts during the studio ().

Regarding ‘what’ was adjusted, the reconstruction suggests that we mainly worked on the learning artefacts, spurred by changes in the learning mode (all activities were organized collectively) and the learning content (a running case). There is one series of small adjustments: we began with one fill-in template, added open templates, and finally reworked everything into a gamified set of fill-in cards. In our theoretical conjectures, we argued that such incremental changes suggest a searching process and thus could enhance DLL. In hindsight, this indeed proved to be the case, as the gamified set of cards led to three basic questions that will structure the third studio: (1) how do I start a collective learning trajectory? (2) how do I steer a collective learning trajectory? and (3) how do I introduce a participatory culture in my organization?

In sum, our second studio did generate quite some room for DLL, partly triggered by a series of coincidences but also by a consistent search for interactive and coherent learning artefacts. suggests that we mostly made adjustments that cover multiple mechanics. The introduction of a collective template, for instance, was reinforced by the decision to keep all discussions collective. Or the (spontaneous) decision to also reflect on an ongoing case led to the decision to work with blank templates. also suggests that most adjustments were discussed and agreed upon collectively. For instance, each time an organizer or a participant introduced a new concept, we collectively positioned it within the common narrative that we were developing as a group. This is quite different from the first studio in which one participant surprised us on the final day with his own synthesis.

Our main insight came at the end of the final studio-day, when we realized that DLL not only required a (collective) reflection-on-action but also reflection-in-action. Otherwise, things remain too abstract, too remote from the practice of the participants, and thus unable to (fundamentally) change this practice. We already wrote that participants started to make these reflections-in-action by themselves: one, in her ongoing case; others, in discussions with colleagues. During these moments of reflection, the participants started discussing how to introduce a strategic understanding of participation that allows to navigate between different participatory collectives. At the end of our second studio, we realized that this reflection-in-action should be part of our next studio.

4.3. Participation Studio Limburg: redesign-exercises of participatory practices

Following our insights from our second studio, we decided to focus more explicitly on reflection-in-action in Studio Limburg. We agreed that in the morning session of each studio-day, we would analyse finished cases, just like we did in the previous studios. But that we would, in the afternoon sessions, redesign these cases by practicing the insights that each of us gained during the morning.

We decided to structure the analysis around the three, so-called, ‘basic questions’ which we formulated on the basis of the gamified template that we used on the final day of our second studio: (1) how do I start a collective learning trajectory? (2) how do I steer a collective learning trajectory? and (3) how do I introduce a participatory culture in my organization? We summarized these questions on a poster and included sub-questions, exercises and templates, which should all help to answer these basic questions. By working on three basic questions, we thought we could introduce a more complex and power-sensitive understanding of participatory planning by adopting a step-by-step approach: first working on diversifying the collectives that one works with during a participation trajectory (question 1), then redefining the different activities of this trajectory in order to connect the diversified collectives at strategic moments in time (question 2) and finally reflecting on how this notion on participation can be introduced in larger (planning oriented) administrative structures (question 3).

The course of the afternoon sessions was less predetermined. We agreed upon the content of the redesign-exercises together with participants, so these would relate to the participatory challenges that they were struggling with in their daily practice at that moment. Some of the afternoon sessions were supervised by us, some by external practitioners. Each brought their own learning artefacts and content to the studio.

illustrates that we radically altered our studio compared to the previous one, but that we hardly introduced any changes during the studio. It appears that we had the feeling that our approach worked. Until the last day, when we agreed upon a drastic adjustment, namely, to organize two extra coaching sessions.

Table 3. Reconstruction of participation studio Limburg.

does not give us many clues on whether these adjustments led to DLL. The amount of process dynamics is so low that our theoretical conjectures do not help us out here. There are no non-anticipated activities. All adjustments, except for one on the second studio-day, were planned. There are no collective decisions to change, and there are no incremental changes. This could either mean that we were in the process of DLL from the start or that there was no DLL at all. The empirical data suggests that we initially believed in the first scenario. On the first studio-day, the participants reacted positively to our poster, our definition, the cases, the exercises, etc. There were many ‘eureka’ moments: ‘Does this mean that we could use participatory activities in a strategic way’ or ‘So, we do not always have to strive for a representative segment of the community’. Encouraged by so much enthusiasm, we kept on going along the same track. Until the last studio-day when, against all expectations, one of the participating organizations expressed that ‘we still do not know what to do next’. In hindsight, we overlooked quite some signals that suggested that not all participants were engaged in DLL. Already on the evaluation of the second studio-day, one of the participants told us that ‘today was very interesting, but we are not ready for this’. Similar remarks were made during the evaluation of the third day ‘fantastic exercises, but we lack the expertise to apply this in our organisation’. ‘Though we would really like to, we simply lack the time to do all this’. On the last day, it finally got to us. The participants simply did not see how they could adopt their insights into their organizations, despite all our exercises. So, maybe the second conjecture (there was no DLL) was more correct?

Let us, in search of explanations, make a more detailed analysis of our empirical material. We will again begin with looking at ‘who’ introduced the adjustments. As argued earlier, we hardly made any changes during the studio. We must have assumed that we had developed the most effective approach and therefore, no more changes were needed. One of the reasons why this might not have been the case, is that our approach had become too coherent, leaving no room for the collective writing of a narrative. Maybe we were so happy with the reactions on the first studio-day that we kept on playing the role of teachers hoping for more eureka moments. In hindsight, it was us who reflected on each studio-day, not the participants. It was us who developed the basic questions and sub-questions, not the participants. We had already forgotten the lessons-learned after the first studio. During the collective evaluation on the last day, we agreed to go for two extra coaching sessions. However, it was again us who prepared these sessions.

Regarding ‘why’ these adjustments were introduced, makes clear that the previous studio is again the main trigger. Once again, this trigger results in adjustments over all three process mechanics. The collective evaluations at the end of each studio-day seem to have only triggered small, practical adjustments in the course of the studio. The most crucial trigger appears only at the end. As argued earlier, there were signs from the second studio-day onwards, but we simply did not notice them. Until one of the participants boldly stated that ‘The studio did not deliver what it promised. It did not help us improve our participatory process’. We definitely did not anticipate this reaction. That was the moment when we realized that switching between ‘reflection-on-action’ and ‘reflection-in-action’ is not evident. It requires insight in the capabilities of each participant, and more specifically, in how aware the participant is of the participatory culture that he/she is part of, his/her position in this organization, his/her capability to challenge this culture, etc. These insights became even more clear to us after the two extra sessions.

Finally, regarding ‘what’ was changed, there seems to be only one adjustment that was not planned at the start of the studio, namely the decision to also frame the afternoon exercises with other design frameworks (e.g. introducing the approach of non-violent communication). Judging from the feedback of the participants, these exercises seemed to work very well: they were hands on and immediately deployable. We planned, from the beginning, to develop a game (i.e. a new learning artefact) that would integrate all concepts and exercises. Again, the participants reacted enthusiastically. In hindsight, the game did help the participants to see the bigger narrative, it helped to literally experience the strategic potential of a more political understanding of participation: thinking in strategic alliances, adapting activities to changes in the process, changing the own participatory culture of an organization by shifting roles in participatory trajectories, but it did not help them to link this narrative to the particularities of their own daily practice.

Regarding the two extra sessions, shows how we made ‘radical’ adjustments, across all three process mechanics. According to our initial conjectures, this hints at DLL. These adjustments did indeed lead to a completely new approach for our fourth studio. We decided to drop the poster and work with a set of cards. These are, on the one hand, more open than the poster as they do not impose any hierarchy between concepts. One can always reshuffle them. At the same time, we made the cards more self-explanatory, so that the exercises needed less introduction. This allowed for more informal use, during which the participants could just ‘play around’ with the cards. We hoped that this would trigger more collective reflection.

In sum, our third studio imposed a very ‘closed’ narrative on participatory planning, summarized in a poster and a game (learning artefacts) and a limited set of balanced concepts (learning content), resulting in a hierarchical relation between organizers and participants (learning mode). The narrative did at first inspire the participants – ‘we can also work differently’ – but at the same time overwhelmed them ‘we are not equipped to do all this’. This made us realize that to truly learn, we not only needed to reflect on/in the cases but also on/in the participatory culture of the organizations involved in these cases. Do the organizations have the capability to implement the activities that we develop for our participatory case? Do we first need to restructure the organization of our own studio before we can continue our trajectory?

5. Conclusion

The aim of this paper was to reflect on the kind of processes that could help planning practitioners to reflect-in-action. We argued that this required a collective double-loop learning process which we defined as a process of critical reflection during which a collective of planners questions and redefines the values and assumptions on which they rely when they facilitate participatory planning trajectories. We adopted the approach of conjecture mapping (Sandoval Citation2014) to analyse an intuitively designed process of collective reflection in order to understand why we expected some of the adjustments that we made along the way to trigger DLL.

This reconstruction resulted in the Participation Studio Conjecture Map, a more detailed description of the process mechanics that were activated during the studios ().

Regarding our ‘learning artefacts’, we observed that we started with isolated schemes and ended with one coherent poster structured around three sets of exercises. The detailed analysis of how we adjusted these learning artefacts throughout the three studios led to a first design conjecture, namely that DLL requires artefacts that support both collective reflection-on-action and individual-reflection-in-action. Each participant is involved in his/her own participatory project. The artefacts should help these participants to exchange experiences gained during these projects. This requires structured collective reflection-on-action. What do we have in common? What is particular to my own situation? But it should also help them to apply insights from these collective reflections back into their individual projects. This requires individual reflection-in-action. How will I translate it back to my process? And into my organization?

Regarding our ‘learning content’, we observed that our concepts and frameworks gradually grew more integrated, from an unorganized multitude into one coherent narrative on ‘participation as collective learning’. The detailed analysis of how we played around with the learning content throughout the three studios led to a second design conjecture, namely that DLL requires the participatory development of a coherent narrative, involving both the participants and the organizers.

Regarding our ‘learning mode’, we made the initial observation that there was no clear evolution: it changed from mainly individual reflections supported by externals in the first studio, to collective sessions in the second studio, to group sessions in the third studio. The detailed analysis led to a third design conjecture, namely that DLL requires insights in the capabilities to change, both of the participants and of the organizations that these participants are part of. This means in particular that the dynamic of a learning trajectory depends on the capability of the collective to reflect together, to develop a narrative together, to work out proposals together (that fit within this narrative), to try these proposals individually, to then reflect again, translate it back into the narrative, etc.

When we look closely at the analysis of our three participation studios, it becomes clear that there is no such thing as an ideal trajectory (or an ideal integration of the three described process mechanics). Turning each group of participants into a unique learning collective requires a unique learning trajectory. Participants arrive with different experiences, belong to different types of organizations, possess different capabilities to adopt insights in their practice; have different capabilities to function in a learning collective; etc.

In studios 4 and 5, we tried to integrate these insights and the Participation Studio Conjecture Map that we developed during the first three studios (). We began with scanning the group of participants, as the reconstruction of our first three studios made clear that how we enter our conjecture map (i.e. how we choose the initial settings of our mechanics [e.g. more or less theory; more or less groupwork; etc.]) should be in tune with the collective capacities of the group.

In participation studio 4, all participants were currently engaged in participatory processes that were stuck. Key actors simply refused to continue; committees only wanted to take up the role of ‘watchdog’ or local policy makers could not reach a consensus on how to continue. In line with our conjecture map, we, therefore, decided to keep the amount of theory (learning content) low and focus on going through the exercises (learning artefacts) in duo’s (mode of learning) with the aim to develop concrete action-plans with which each of the participants could then start to address their particular participatory situations. This approach worked until session 2 when one of the participants concluded ‘The first session was really hands-on. It made sense. But today things became really complex. I lost the link between all the exercises’. We saw others nod in agreement. As all our exercises were based on learning theories, we decided to collectively analyse their action-plans with the help of some of these theories. And it worked.

At first I thought that the second exercise was nothing new, but then I realised that it is in fact turning things around and no longer approaches participation as a means to get a better project but uses projects to get better participation.

In both studios, we did not have to develop any new learning artefacts, include other learning theories, or invent alternative modes of working together. The components of our Participation Studio Conjecture Map that became more and more precise during the first three studios were there and represented in a set of cards that we could use in a flexible manner. What did call for our full attention was to make sure that the initial setting of our mechanics was in tune with our learning collective.

We started this paper with the observation that collective learning-in-action is an essential part of the planning profession to discover and sharpen its transformative potential. The participation studios were the first test to install a safe haven to reflect and experiment with an environment that allows to rethink assumptions (of participatory planning) and new professional practices.

After running and analysing five participation studios, it became clear how learning to reflect collectively needs to realign the (collective) critical analysis of planning practice with a reflection on the professional (learning community) and organizational (learning environment) dimensions of planning. In order to be successful, the collective learning trajectory in the studio needed to be organized in relation to the collective learning trajectories of the cases and in relation to the collective learning trajectory of the organizing team to acknowledge the variety of professional positions and expectations that form a group.

The analysis described in this paper gives a first idea on how such a triple process of learning can be structured and as such introduced in a variety of planning organizations. Not as a blueprint or fixed methodology but as an active process of navigating in and with the collective learning trajectory of the very different engaged learning communities, the different represented cases and the existing learning environments of the involved organizations. The Participation Studio Conjecture Map helps to make the different directions a process of collective reflection can take explicit by deciding which process mechanics to activate and how to acknowledge the positions and room for manoeuvre of the individual members of the learning collective.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Argyris, C., and D. Schön. 1978. Organizational Learning: A Theory of Action Perspective. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Argyris, C., and D. Schön. 1996. Organisational Learning II: Theory, Method and Practice. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Beauchamp, C. 2015. “Reflection in Teacher Education: Issues Emerging from a Review of Current Literature.” Reflective Practice 16 (1): 123–141. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2014.982525

- Bertolini, L., D. Laws, M. Higgins, R. Scholz, M. Stauffacher, J. Vanaken, and T. Sieverts. 2010. “Reflection in Action, Still Engaging the Professional? Introduction Practising “Beyond the Stable State” Building Reflectiveness Into Education to Develop Creative Practitioners.” Planning Theory & Practice 11: 597–619. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2010.525370

- Boonstra, B. 2015. Planning Strategies in an Age of Active Citizenship: A Post-structuralist Agenda for Self-organization in Spatial Planning. Groningen: InPlanning.

- Boonstra, B., and W. Rawls. 2021. “Ontological Diversity in Urban Self-organization: Complexity, Critical Realism and Poststructuralism.” Planning Theory, 20 (4): 303–324. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095221992392

- Boud, D. 2010. “Relocating Reflection in the Context of Practice.” In Beyond Reflective Practice: New Approaches to Professional Lifelong Learning, edited by H. Bradbury, N. Frost, S. Kilminster, and M. Zukas, 25–36. London: Routledge.

- Boud, D., and P. Hager. 2012. “Rethinking Continuing Professional Development Through Changing Metaphors and Location in Professional Practices.” Studies in Continuing Education 34: 17–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0158037X.2011.608656

- Bradbury, H., F. Nick, S. Kilminster, and M. Zukas. 2010. Beyond Reflective Practice: New Approaches to Professional Lifelong Learning. London: Routledge.

- Brookfield, S. 2010. “Critical Reflection as an Adult Learning Process.” In Handbook of Reflection and Reflective Inquiry: Mapping a way of Knowing for Professional Reflective Inquiry, edited by N. Lyons, 215–236. London: Springer.

- Campbell, H., M. Tait, and C. Watkins. 2014. “Is There Space for Better Planning in a Neoliberal World? Implications for Planning Practice and Theory.” Journal of Planning Education and Research 34: 45–59. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X13514614

- Collin, S., and T. Karsenti. 2011. “The Collective Dimension of Reflective Practice: The How and Why.” Reflective Practice 12: 569–581. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2011.590346

- De Blust, S., O. Devisch, and J. Schreurs. 2019. “Towards a Situational Understanding of Collective Learning: A Reflexive Framework.” Urban Planning 4: 19–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v4i1.1673

- De Leo, D., and J. Forester. 2017. “Reimagining Planning: Moving from Reflective Practice to Deliberative Practice – a First Exploration in the Italian Context.” Planning Theory & Practice 18: 202–216. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2017.1284254

- DiSalvo, B., J. Yip, E. Bonsignore, and C. Disalvo. 2017. Participatory Design for Learning, Perspectives from Practice and Research. London: Routledge.

- Fischler, R. 2012. “Reflective Practice.” In Planning Ideas That Matter, edited by B. Sanyal, L. Vale, and C. Rosan, 313–332. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Fook, J. 2010. “Beyond Reflective Practice: Reworking the ‘Critical’ in Critical Reflection.” In Beyond Reflective Practice: New Approaches to Professional Lifelong Learning, edited by H. Bradbury, N. Frost, S. Kilminster, and M. Zukas, 37–51. London: Routledge.

- Forester, J. 1989. Planning in the Face of Power. Berkley: University of California Press.

- Forester, J. 1993. Critical Theory, Public Policy, and Planning Practice: Toward a Critical Pragmatism. Albany, NY: Albany State University of New York.

- Forester, J. 2013. “On the Theory and Practice of Critical Pragmatism: Deliberative Practice and Creative Negotiations.” Planning Theory 12: 5–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095212448750

- Friedmann, J. 2008. “The Uses of Planning Theory A Bibliographic Essay.” Journal of Planning Education and Research 28: 247–257. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X08325220

- Gardner, F. 2014. Being Critically Reflective. London: Red Globe Press.

- Goh, A. 2019. “Rethinking Reflective Practice in Professional Lifelong Learning Using Learning Metaphors.” Studies in Continuing Education 41: 1–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0158037X.2018.1474867

- Gualini, E. 2015. Planning and Conflict. Oxford: RTPI and Routledge.

- Healey, P. 2009. “The Pragmatic Tradition in Planning Thought.” Journal of Planning Education and Research 28: 277–292. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X08325175

- Innes, J. 1995. “Planning Theory's Emerging Paradigm: Communicative Action and Interactive Practice.” Journal of Planning Education and Research 14: 183–191. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X9501400307

- Kadlec, A. 2006. “Reconstructing Dewey: The Philosophy of Critical Pragmatism.” Polity 38: 519–542. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.polity.2300067

- Kuhk, A., H. Heynen, L. Huybrechts, J. Schreurs, and F. Moulaert. 2019. Participatiegolven. Leuven: Leuven University Press.

- Lindeman, E. 1926. The Meaning of Adult Education. New York, NY: New Republic.

- Metzger, J., L. Soneryd, and S. Linke. 2017. “The Legitimization of Concern: A Flexible Framework for Investigating the Enactment of Stakeholders in Environmental Planning and Governance Processes.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 49: 2517–2535. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X17727284

- Parker, G., and E. Street. 2015. “Planning at the Neighbourhood Scale: Localism, Dialogic Politics and the Modulation of Community Action.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 33: 794–810. doi:https://doi.org/10.1068/c1363

- Sager, T. 2011. “Neo-liberal Urban Planning Policies: A Literature Survey 1990–2010.” Progress in Planning 76: 147–199. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progress.2011.09.001

- Sandoval, W. 2014. “Conjecture Mapping: An Approach to Systematic Educational Design Research.” Journal of the Learning Sciences 23: 18–36. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2013.778204

- Schön, D. A. 1983. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. London: Temple Smith.

- Scott, M. 2019. “Reflecting on Theory and Practice.” Planning Theory & Practice 20: 3–7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2019.1574380

- Wenger, E. 1998. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Zakhour, S. 2020. “The Democratic Legitimacy of Public Participation in Planning: Contrasting Optimistic, Critical, and Agnostic Understandings.” Planning Theory 19: 349–370. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095219897404