ABSTRACT

This paper proposes a conceptual reading of the issues and theories that have cumulatively formed the backbone of current ‘innovatized’ territorial development policies. It emphasizes the broadening of a technological innovation perspective to a cultural and, subsequently, social and societal innovation perspective. While this broader perspective encourages systemic changes that are crucial in order to reach global sustainability goals, it tends to under-conceptualize how to make transformative change economically viable. The paper, therefore, develops a transformative territorial innovation policy approach focused on ‘territorial value’, which is understood as the result of locally interdependent production, consumption and living advantages in the long run. Such a policy should be based on enlarged anchoring milieus of actors engaged in place-based experiments at the nexus of export-, visitor- and household-based income systems. To do so, it should promote policy mixes that support co-innovation, entrepreneurship, sensemaking and institutionalizing across multiple scales and locations. The paper finally calls for further research and conceptualizations on territorial value and territorial valuation and for a new role of the social sciences and humanities in innovation.

1. Introduction

The last 40 years have led to the establishment of the innovation paradigm as a set of public policies to support the competitiveness of regions and nations in a globalized economy. From a theoretical perspective, various territorial innovation models have emphasized the interdependency of local dynamics of innovation and territorial development (Moulaert and Sekia Citation2003), and have promoted instruments to support regional entrepreneurship, collective learning, knowledge transfer, creativity and business networking (Lagendijk Citation2011).

More recently, innovation has gained new momentum in general policymaking, whereby conventional competitiveness policy paradigms are being reconsidered in line with sustainable development goals (SDGs) (United Nations Citation2020) such as global warming, social equalities, demographic change and urbanization. In this context, innovation policy is no longer seen merely as a driver of technological and economic change, but also as a driver of institutional, environmental and societal transformation (Diercks, Larsen, and Steward Citation2019). These changes in the innovation policy paradigm are not without consequence for territorial policy issues and scope. Current territorial innovation policies must deal with tensions between economic and societal purposes and must be conceived, beyond a region, in the context of multi-local and multi-scalar frameworks (Coenen, Benneworth, and Truffer Citation2012).

How can territorial innovation be addressed within a transformative innovation paradigm? How is it possible to manage tensions between economic, environmental and societal rationales and, if possible, to turn them into local synergies that increase territorial value? How should current territorial innovation policies be conceptualized therefore? How can we systematize the place-based policy levers of a multi-local and multi-scalar transformative policy? This paper discusses these questions and argues, in line with recent literature in geography of innovation, that a renewed conceptualization of territorial innovation models is needed.

The first part of the paper proposes a historical reading of the successive issues and theories that underlie the ‘innovatization’ of territorial development policy (Jeannerat et al. Citation2017). This reading emphasizes the broadening of a technological innovation perspective to a cultural and, subsequently, a social and societal innovation perspective that goes hand in hand with generalized innovation-focused policy rhetoric. While this broader perspective encourages systemic changes that are crucial in order to reach global sustainability goals, it tends to under-conceptualize how to make transformative change economically viable.

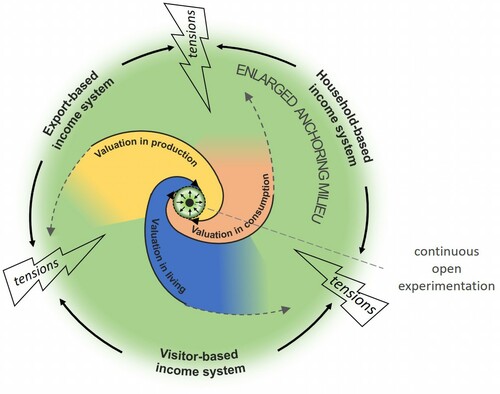

The second part of the paper puts forward a general transformative territorial innovation policy approach focused on ‘territorial value’, which is understood as the result of locally interdependent production, consumption and living advantages in the long run. Such a policy should be based on ‘enlarged anchoring milieus’ of actors (companies, authorities, media, research centres as well as civil and non-governmental organization) engaged in place-based experiments at the nexus of export-, visitor- and household-based income systems. To do so, it should promote policy mixes that support societal transformation through co-innovation, entrepreneurship, sensemaking and institutionalizing across multiple scales and locations. The paper concludes with future directions for territorial innovation policy research.

1.1 The ‘innovatization’ of territorial policy: from technological to cultural, social and societal innovations

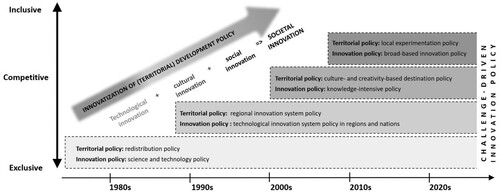

The progressive adoption, development and expansion of innovation in policy designs can be outlined as a historical ‘innovatization’ process that has concerned policymaking as a whole and territorial innovation policy in particular (Jeannerat et al. Citation2017). This process is depicted in the next sections in terms of a cumulative series of generations of territorial policies, pertaining first to (Section 1.1) technological, then to (Section 1.2) cultural and finally to (Section 1.3) social and societal innovation ().

1.2 Technological innovation: from post-war to post-Fordist global competition

The first generation of territorial policies in Western countries was motivated by the industrial boom of the post-war 1960s and 1970s, which increased regional disparities (Maillat Citation1998). Public concern was about maintaining a balanced development of income and infrastructure between the different regions of a national territory, and policymaking focused on offering financial incentives and creating low-cost production conditions to attract investment and jobs into peripheral regions. Innovation policy was mainly conceived from the exclusive perspective of public spending on technological and scientific developments which were justified in a cold war context (e.g. military technologies and space-race missions) and which it was foreseen would generate new technology-driven economic opportunities (Godin Citation2017). Both regional and innovation policies were considered from an exogenous perspective that placed public intervention in a linear causal relationship between resources created ‘there’ (capital, production or technology assets) and economic development generated ‘here’.

Exogenous support for development based on expenditure and on redistribution and allocation of wealth governed by a Keynesian welfare state (Scott and Storper Citation1992) became inoperative, even counterproductive (Maillat Citation1998), in the Fordist crisis of the 1970s and 1980s. While many large-scale American and European industrial regions were experiencing an unprecedented and rapid decline, regional and innovation policies converged towards a new paradigm of economic development and public intervention led by two strands of theoretical studies.

A first strand of industrial economics shed light on the non-linear, multi-agent and systematic interactions that underpin technological change, and on how this change is endogenous to economic development (Dosi et al. Citation1988; Landau and Rosenberg Citation1986). Previously considered to be an exogenous variable, technological development came to be seen as essential in order to stimulate companies and help them adapt to the new international situation. A second strand of regional science and economic geography pointed to the pre-existing economic, socio-cultural, political and institutional conditions of innovation that enabled certain regions to innovate in a globalized economy of flexible industries (Scott Citation1988; Camagni Citation1991; Cooke Citation1992).

Emphasizing the systemic nature of technological change and entrepreneurship, these two cross-fertilized strands of innovation studies contributed, in a dialectical and complementary manner, to a first innovatization phase of territorial development policy seeking to increase the competitive advantage of nations and regions. The first strand explains the functioning of complex technological innovation systems (TISs) that are implemented through region-focused innovation policies (McCann and Ortega-Argilés Citation2013). The second explains the functioning of specific regional innovation systems (RISs) that need to be boosted and developed through innovation-focused policies (Morgan Citation2016). Public policies are conceived in terms of innovation systems that are anchored in specific national (Lundvall Citation1985; Edquist Citation1997; Sharif Citation2006; Soete, Verspagen, and Ter Weel Citation2010; Lundvall Citation2010) and regional (Moulaert and Sekia Citation2003; Cooke Citation2008; Doloreux Citation2002; Lagendijk Citation2006) contexts.

These innovation models position technological change as the main driver of socio-economic change and transformation (Foray and Freeman Citation1993). Regions are considered strategic contexts to promote ‘smart specialization’ strategies focused on techno-productive innovations and cumulative learning (Foray, David, and Hall Citation2009). The managerial concept of innovation ‘clusters’ has become a generic term for regional studies but also for the implementation of standardized policies based on this approach (Porter Citation1998; Martin and Sunley Citation2003). On the one hand, they promote knowledge transfer, entrepreneurship and innovation networks in areas of regional specialization which are identified as competitive. On the other hand, they create attractive learning and investment conditions for large companies wishing (a) to benefit from external learning opportunities offered by the local innovative environment, and (b) to limit the technological, productive and market uncertainties induced by innovation.

1.3 Cultural innovation: from product(ion) to knowledge and creativity

By the end of the 1990s, the generation and exploitation of knowledge had become the explanatory framework for the development of TIS (Lundvall and Johnson Citation1994) and RIS (Cooke Citation1992). On the one hand, innovation is driven by interdependent learning between science, technology, industry and the markets, which co-evolve with the socio-economic context in which they are embedded. On the other hand, innovative regions are ‘learning regions’ (Florida Citation1995; Asheim Citation1996; Rutten and Boekema Citation2012; Maillat and Kebir Citation2011) capable of endogenous regeneration while positioning themselves within and interacting with other production and knowledge spaces.

In the 2000s, the innovatization of regional policy took an additional step forward with the growing economic value of knowledge-intensive goods and services, and in the trends initiated by the massive deployment of ICT, technology became not an end in itself, but began to facilitate the creation and dissemination of innovations increasingly driven by a constant cultural evolution of consumption practices. Furthermore, creative activities dedicated to the design and marketization of manufactured goods (rather than the manufacturing process itself) became a new determinant of innovation-based competitive advantage and of post-industrial regeneration.

The growing centrality of intangible components in economic value activities underlines the importance of ‘symbolic’ knowledge (Asheim Citation2007) (marketing, design, advertising, experience, etc.) in goods and services (Kebir and Crevoisier Citation2008; Cooke and Lazzeretti Citation2008; Power and Scott Citation2004; Pratt and Jeffcutt Citation2009; Lazzeretti Citation2012) and also marks the growing role of consumers and users in innovation and value creation (Von Hippel Citation2005).

Thus the dynamics of competition, traditionally based on (tangible) use value, increasingly revolve around the (intangible) sign value of products (Lash and Urry Citation1994). Moreover, with increased mobility, the emphasis is less on obtaining a coherent and integrated production or innovation system on the regional scale, and more on regional anchoring of knowledge circulation networks (Crevoisier and Jeannerat Citation2009). Innovation policies tend to focus increasingly on the contexts and creative processes upstream of innovation, of which culture (together with technology) represents a constituent element. There is also now a greater focus on human capital and networks of actors than on firms and innovation networks (Rutten and Boekema Citation2012).

From a spatial point of view, economic value is increasingly created in places where new uses are invented and less in places where advanced technologies are produced (Crevoisier and Jeannerat Citation2009). Territorial innovation policy is no longer confined to the techno-productive aspects of innovation but has also become a ‘destination policy’ based on culture and creativity (Cooke and Lazzeretti Citation2008; Pratt Citation2009; Cooke and Lazzeretti Citation2008; Power and Scott Citation2004). Territorial innovation policy should thus promote local cultural amenities that can retain and/or attract creative talents who are regarded as lead innovation agents within the knowledge economy (Florida Citation2005). At the same time, they should also promote competitive cultural attractions for the increasingly mobile visitors looking for local consumer experiences (Lorentzen and Jeannerat Citation2013).

Cities are regarded as privileged cultural environments for creative activities and knowledge-intensive business services (KIBS) that can act either as competitive export-oriented clusters or as central spaces within global production and innovation networks (Simmie and Strambach Citation2006; Strambach Citation2008; Shearmur and Doloreux Citation2015). Furthermore, cities are also attractive consumption systems for visitors and the creative class. The concept of the ‘creative city’ has become a precept of urban innovation policies to regenerate the competitiveness of territories through endogenous development dynamics supported by local culture circles and citizens (Landry Citation2000) as well as through exogenous development dynamics based on attractiveness for the global creative class (Florida Citation2005).

The common fundament of these territorial innovation policies is that culture plays a central role as shared meaning giving sense to artefacts and activities. Cultural innovation consists in creating and exploiting new shared meanings assigned to goods and services. The value of innovation is therefore no longer about embodying energy, work and knowledge in new products or processes, but about embedding these meanings within and across regions and communities (Crevoisier Citation2016).

1.4 Social and societal innovation: from competitive to transformative innovation policy

The financial crisis of 2008 and 2009 added new momentum to the innovatization of territorial policy, along with public calls for a new paradigm of economic policy (OECD Citation2011). Ecological and societal grand challenges such as global warming, demographic change, food security, energy transition and social disparities were now on the agenda (Kuhlmann and Rip Citation2018), and the interdependence of the problems and solutions required a systemic management of collective actions, bringing together heterogeneous actors with diverse and often conflicting interests. This implies not only a new role for research, enterprises and public authorities but also new actors in innovation such as citizens, consumers and non-governmental organizations.

The concept of ‘social innovation’, promoted by the Europe 2020 strategy (Moulaert et al. Citation2017) to support science initiatives, and of societal solutions developed ‘with and for society’ are emblematic of a changing approach to innovation. New policy mixes and more inclusive innovation policies have been put in motion against the hegemony of techno-scientific policies focused on research and companies (Flanagan and Uyarra Citation2016), and social innovation has come to be seen as a lever of community building and collective empowerment to address social problems (Owen, Macnaghten, and Stilgoe Citation2012; Van Der Have and Rubalcabac Citation2016; Moulaert et al. Citation2017). In contrast to previous innovation policies, which essentially focused on actors upstream of the value creation chain, social innovation policy should consider participatory and democratic processes within enlarged communities of living, and should empower enterprises as well as citizens to develop new collective sustainable solutions (Moulaert Citation2009).

Social innovation has gained further strategic attention in recent research and policy agendas as a crucial driver of a sustainable societal change that cannot be achieved merely through technological solutionism and market mechanisms (Loorbach et al. Citation2020). The integration of social innovation issues into a general societal change reflects a further broadening of innovation purposes and transformative policy considerations raised in particular by sustainability transition research in recent years (Markard, Raven, and Truffer Citation2012). Innovation policy should foster the emergence, within specific urban and regional contexts, of niche innovations that diffuse and create institutional change on larger scales and in a variety of locations (Geels Citation2002; Geels and Schot Citation2007; Smith et al. Citation2016; Loorbach et al. Citation2020). Conceived not merely as catalysts of innovation but as active agencies of systemic change, transition policies should give directionality to societal goals and should co-evolve with new solutions, practices and knowledge generated by innovations. Policy innovation is therefore an inherent and constitutive element of innovation policies (Perez Citation2013; Weber and Rohracher Citation2012).

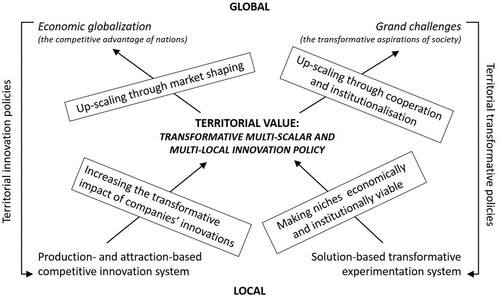

From this perspective, territorial innovation policies have mainly drawn on niche management strategies consisting of supporting pilots and demonstration experiments taking place in specific local living contexts. From this point of view, regions are conceived of as the context for solution-based transformative experimentation ( and ). Above and beyond supporting niche innovations, the new role of cities and regions in the success or failure of diffusing and institutionalizing place-based problems and solutions is crucial (Coenen, Hansen, and Rekers Citation2015). Territorial innovation policies must be conceived of as local interventions anchored in specific cities and regions as well as operations reaching multiple institutional scales and locations (Coenen, Benneworth, and Truffer Citation2012).

In this enlarged approach to territorial innovation policy, competitive and transformative purposes are partly antagonist: competitive activities may compromise societal change in the long term and vice versa. If so, the territorial value of a place may stagnate or even decrease. Consequently, not only the spatial shape, but also the aim, of a territorial innovation policy must be reconsidered with a renewed focus on place-based levers and enlarged local conditions of sustainable territorial value creation ().

2 Between competitive and transformative policies: creating territorial value through enlarged anchoring milieus

The innovatization of territorial policies has built upon generations of innovation policies with different rationales () driving controversial debates on their primary technological, economic, or societal purposes (Hassink Citation2020). Competitive and transformative approaches to innovation policies coexist around tensions concerning their possible or impossible complementarities (Schot and Steinmueller Citation2018; Diercks, Larsen, and Steward Citation2019).

2.1 Two approaches in tension

Contemporary tensions at stake in the conception and implementation of territorial innovation policy can be depicted as a stretch between two ideal-typical approaches to territorial innovation and the associated policies.

The first ideal type is the competitive approach, which conceives of territorial policy as a response to economic globalization driven by the mobility of goods, production factors and consumers. Territorial innovation policies, which are production- and attraction-based, are intended to promote new export-based income for the region; this can be achieved either by focusing on the export of goods and services (e.g. industrial innovation clusters) or by capturing income from mobile consumers-visitors or consumer-residents (e.g. cultural and creative cities or tourism resorts). This focus on export-based income flows driven by innovation has been subject to criticism because it views sustainability concerns as an afterthought rather than a motive. Economic viability is considered to be the prior condition for generating profit, which is then invested in social and ecological causes. It postulates, first, that money must be made in the global market regardless of the effects of regional exports on sustainability in other places and, second, that money inflows will automatically resolve regional sustainability issues.

This vision is assumed within a socio-economic system evolving with sequential waves of technological paradigms driven by the search for competitive production. However, it does not provide tenable policy insights when it comes to transforming this system (Diercks, Larsen, and Steward Citation2019). To be transformative, innovation policy must create the conditions for new paths that are future-oriented. In this regard, innovation is about transforming established competition practices by shaping markets in line with global sustainability goals (Mazzucato, Kattel, and Ryan-Collins Citation2020). Sustainability goals have become mission statements and represent prior conditions for economic prosperity, rather than the reverse.

For traditional territorial innovation policy driven by production and competitiveness, these multi-local and multi-scalar issues are difficult to handle. On the regional scale, innovation policy should not only focus on productivity gains and export sales but on transforming industries in line with local sustainable living conditions that do not jeopardize the attractiveness of the region for inhabitants and visitors in the longer term (Crevoisier and Rime Citation2021; Bailey and De Propris Citation2020). On extra- and supra-regional scales, territorial innovation policy should ensure that the transformative effects on local economies do not have an adverse impact on sustainable development elsewhere and that they contribute, together with upper-scale policies, to changes in the global markets, as well as social, cultural and institutional settings (Miörner and Binz Citation2020).

The second ideal typical approach is the transformative approach, which interprets territorial policy as a means to promote, manage and operate new disruptive modes of production, consumption and living to tackle contemporary grand challenges. Innovation policy aims towards societal change that gives prominence to influential niche innovations and institutional reforms actuated in concrete places, spaces and multi-scalar institutional contexts (Fuenfschilling and Truffer Citation2014). From this perspective, transformative territorial innovation policies are mainly based on promotional tools and support programs for pilot and demonstration experiments, and the local and multi-local dissemination thereof (Sengers and Raven Citation2015; Carvalho and Lazzerini Citation2018; Loorbach et al. Citation2020). The local scale is conceived of as an experimentation system that actuates, in specific places of action, the abstract transformative aspirations of society, expressed on the global scale, in concrete problem settings ().

However, up-scaling these experiments remains a crucial policy challenge (Miörner and Binz Citation2020). Niche experiments are solution-driven and strongly place-dependent, and cannot be exported as they are. They must be translated from one context to another. Society-driven, transformative experiments are primarily valued in use and experience rather than through exchange, and the absence of market incentives often hinders diffusion and growth to upper-scale developments (Von Hippel Citation2016). Consequently, many experiments fail to go beyond the boundary of their initial supportive community or beyond the time horizon of their initial public funding and sponsorship.

In brief, transformative territorial innovation policies currently face two major hurdles: making territorial innovation systems more transformative through sustainability-oriented incentives, and increasing the institutional and economic viability of niche innovations (Section 2.2). Ideally, these policies should also contribute to shaping the sustainability of global markets and promoting better institutional and cooperation settings on the upper scales (). This is probably, at least in part, outside of the direct reach of territorial policy but must be conceived holistically to envisage territorial interdependencies of policy mixes (Section 2.4).

2.2 Territorial value at the centre

Although territorial innovation policies today claim to contribute to sustainability and include a narrative about sustainability which bears witness to a responsible attitude, combining transformative values for the future with the need to create new regional monetary income is difficult (Kebir et al. Citation2017). To make economic activities transformative and transformative activities economically viable, the export-based rationale that money must come first as a primary and necessary condition of development to achieve sustainability goals is not tenable.

Up to the middle of the twentieth century, standard economic theory used to consider three production factors, each with its own, specific and irreducible contribution to production: capital, labour and land. Since that time, it has been stated that land no longer makes a full contribution because it can be replicated by capital and labour: fertilizers, and not land, are used to generate more food; cars and other transport allow urban land to extend infinitely, etc. Today, land (and more broadly the earth) is seen as the most limiting and endangered factor for both life and production. Accordingly, strategies of competitiveness and attractiveness that underlie current territorial innovation policies must be revised.

Furthermore, the sustainable territorial income systems to be addressed by new transformative territorial innovation policies must take account of the fact that traditional production and consumption-based territorial revenue has been disrupted by the increase in the mobility of profits, knowledge and, above all, consumers. Nowadays, value is increasingly captured by people other than those who created it and spent in places other than those in which it was created (Segessemann and Crevoisier Citation2016; Talandier Citation2020; Srnicek Citation2017; Bailey, Pitelis, and Tomlinson Citation2018). This is well illustrated by various emblematic cases. In Europe and North America, for example, even highly productive manufacturing regions are among the poorest in their countries, despite high incomes from industrial exports, because profits are no longer reinvested locally. Moreover, workers are increasingly likely to spend their wages in other, more attractive, regions, on leisure, studies, health, retirement, etc. Equally, cities that are highly attractive for tourists increasingly have a negative impact on the quality of life of their inhabitants. Furthermore, real-estate investments and gentrification may also destroy the original creativity conditions of a place (Peck Citation2005).

These examples emphasize the crucial and potentially destructive interdependencies that export-, visitor- and household-based income systems have on territorial value creation as well as on the natural and social living environment of the region:

An increase in export-based income through the development of productive activities often affects household- and visitor-based income systems through pollution, unattractive industrial sites, etc.

An increase in – usually richer and more mobile – visitors in a region can negatively affect residents’ quality of life, through traffic congestion and the saturation of public spaces by tourists, for example. It can also reduce their purchasing power, through price increases in shops, restaurants, housing, etc.

Taking stock of these potentially destructive interdependencies, contemporary transformative territorial innovation policy should compromise on the tensions between export-, visitor- and household-based income systems and synergize them as much as possible in order to create and capture territorial value for a region or a city.

Consequently, the value of innovation and experimentation should be assessed by their contribution to territorial value. Territorial value is a socio-economic construction, comparable to a certain degree to the valuation on the financial markets (Orléan Citation2011). It is the valuation by society of all the resources preserved or built in the past, as well as their usefulness for the future, and reflects not only the assets themselves, but also their organization and functioning. It has a qualitative dimension that relates to the social debate about the valuation of both the components and the system, but also a quantitative and monetarized aspect, measured by rent prices and total of the rents paid within the region or the city (Camagni Citation2016). It is both absolute and viewed in comparison with other regions and cities, as in modern times, they all coexist within a large, interterritorial market of places. This comparison is performed by major real estate companies, cultural or ecological epistemic communities, trip advisers, etc. as well as by migrating workers and inhabitants. In this view, the region is not merely seen as a production space, but also as a living space, and as land with natural and cultural value.

2.3 Enlarged anchoring milieus as creators of territorial value

Transformative innovation is a valuation process that is also a political ‘inquiry’ process (Dewey Citation1946): it consists of co-developing, co-defining, negotiating, and legitimizing future societal values through inclusive and demonstrative experiments that take place within concrete production, consumption and living milieus (Huguenin and Jeannerat Citation2017). These foreseen values, actuated by concrete projects, underlie a new sustainability-driven moral in markets (Balsiger Citation2021) as well as new justifications for further niche innovations and system changes (Binz and Truffer Citation2017; Jeannerat and Kebir Citation2016; Binz, Truffer, and Coenen Citation2016; Hipp and Binz Citation2020; Xiao et al. Citation2020; Van Winden and Carvalho Citation2019; Dewald and Truffer Citation2012).

This valuation process activates interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary research, collaborative experimentation and participatory public assessment within ‘enlarged anchoring milieus’ primarily focused on living conditions (Kebir et al. Citation2017; Crevoisier and Rime Citation2021). It involves companies, NGOs, media, public authorities, city planners and architects, active citizens, consumers, research and training institutions as well as economic organizations. Coordination between all of these actors does not result from centralized negotiations but rather occurs alongside successive and parallel debates and discussions across the contexts of production, consumption and living within the region. This coordination is essential in order to maintain and increase territorial value.

In this regard, territorial innovation should drive a value-based anchoring of export-, visitor- and household-based incomes (Kebir et al. Citation2017). The London 2012 Olympic strategy of trying to balance the ephemeral benefits of a global tourist attraction with the need to regenerate local living conditions is a good illustration (Thiel and Grabher Citation2015). It is also particularly salient within contemporary smart city and smart urbanism policy (Carvalho Citation2015; Söderström, Paasche, and Klauser Citation2014). The development of new place-based creative offerings, anchored in local circular and touristic economies, within rural spaces for both visitors and inhabitants is also representative of such issues (Manniche, Topsø Larsen, and Brandt Broegaard Citation2021; Manniche and Sæther Citation2017; Mayer and Knox Citation2010). New ecological, energy and building technologies incubated in sophisticated residential markets enable adaptive and higher value industrial solutions to be developed and exported, rather than mass-standardized industrial products (Huguenin Citation2017; Livi, Jeannerat, and Crevoisier Citation2014; Strambach and Lindner Citation2017; Kebir et al. Citation2017; Xiao et al. Citation2020).

In these examples, anchoring means dealing with tensions and transforming local production, consumption and living conditions to sustain a constant regeneration of development capacities and revenue flows within and across regions. Anchoring experiments should actuate, test, realize and reflect on value propositions that reveal, deal with and reduce antagonisms between export-, visitor- and household-based income systems. They encompass but go beyond traditional start-up companies, which are integrated into broader project-based ecosystems of demonstration, reflexive learning and societal change in progress.

An enlarged anchoring milieu can therefore currently be defined as a set of local varied actors (companies, associations, public actors, media, etc.) interacting within a globalization process that is both economic (due to the increasing mobility of goods and factors towards other regions) and environmental; these actors develop activities capable of articulating the resulting tensions in concrete terms. This definition places the conversion of tensions into place-based synergies as the central focus of territorial innovation policies. It is a question of reconciling development with nature, visitors with inhabitants, the production of goods and services with tourism, local supply chains with global competition, and general values of sustainability with their realization within concrete places of action ().

2.4 Towards a multi-local and multi-scalar territorial innovation policy mix

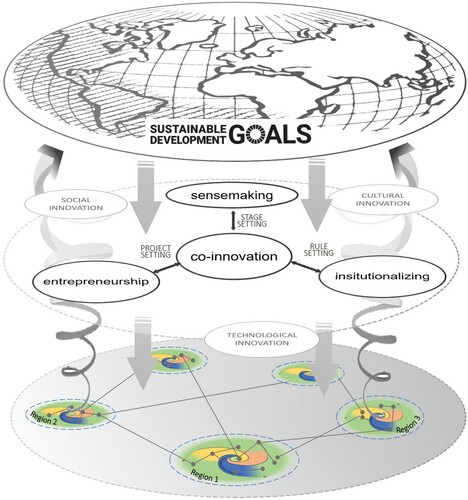

Further to local anchoring strategies, transformative territorial innovation policy must also be able to address global SDGs across multiple scales and locations. To do so, local policy intervention should be seen as part of a wider territorial innovation policy mix (Uyarra and Flanagan Citation2021). Along with the above arguments, this policy mix should be structured around four strategic pillars (). These four pillars have already been emphasized and scrutinized in various ways by innovation and transition studies, but have not been conceptualized together in a systematic manner.

Figure 4. Co-innovation, entrepreneurship, sensemaking and institutionalizing across scales and locations. Source: author’s elaboration, design of SDGs: United Nations (Citation2020).

The first pillar is co-innovation. While innovation has for some time been recognized as a collective process, co-innovation is a further step consisting in a motion to instigate collaborations. Experiments have become a central modality of territorial innovation policy as they enable investigation of uncertain future developments (Huguenin and Jeannerat Citation2017). Inclusive, demonstrative and future-oriented, these experiments act as anchoring points between regional and extra-regional innovation resources (Schmidt et al. Citation2018). For instance, urban labs, living labs, fabrication labs, etc. promote the dynamics of co-ideation and co-creation, co-development and co-implementation at the junction of different sectoral policies (Gill, Pratt, and Virani Citation2019; Nevens et al. Citation2013; Von Wirth et al. Citation2019). These labs are anchoring drivers of territorial value in specific locations, together with networked hubs in multi-local relations (Loorbach et al. Citation2020).

More generally, an experimentation-based territorial innovation policy mix should stimulate hybrid, collective entrepreneurial projects that bring together policymakers with fields of research, business and civil society. Co-innovation drives experiments and vice versa (Ryghaug and Skjølsvold Citation2021). This dual process is central for addressing the policy mix in relationship with the three next interrelated innovation policy pillars.

The second pillar is ‘entrepreneurship’, which is usually addressed in innovation systems literature and policy as the concretization and implementation of co-innovation. In a transformative approach, entrepreneurship goes beyond the Schumpeterian role of recombining resources into new market offerings (Tödtling and Trippl Citation2018). It is viewed as the individual and collective capacity to implement concrete projects to bring about change (Grillitsch and Sotarauta Citation2020). In this sense, territorial innovation policy should give prominence to entrepreneurship ecosystems that are not only about developing new production and market opportunities but also about shaping the future social conditions of these opportunities (Stam and Welter Citation2021). Entrepreneurship concerns the development of new social and user-based solutions, as well as influential leadership, to shape visions and demonstrate, through concrete projects, new possible societal development paths. Entrepreneurship emerges and develops within project-based organizations that involve both local and multi-local communities and may target local, national or global change (Grabher Citation2002). Transformative experiments are a product of the co-innovation process and provide solutions to specific local problems while at the same time inspiring new solutions in other proximate and distant contexts and revealing the needs of upper-scale institutional change.

To be transformative across scales and locations, co-innovation and entrepreneurship must inherently contribute to ‘sensemaking’, a third pillar of transformative territorial innovation policy. On the one hand, sensemaking is both a driver and outcome of co-innovation, as it is about identifying the societal expectations carried by innovation and conceiving of potential futures. On the other hand, and more pragmatically, it is also about influencing options, legitimizing new solutions and, in particular, prioritizing specific public problems. In this respect, territorial innovation policy mixes are also about staging place-based concrete realizations of entrepreneurial initiatives communicated at national and international media scales (Jeannerat and Kebir Citation2016; Hipp and Binz Citation2020; Heiberg, Binz, and Truffer Citation2020; Costa Citation2017; Guex and Crevoisier Citation2015). From this perspective, support within territorial innovation policy for cultural activities, which has been largely oriented towards heritage since the 2000s, should give more strategic attention to creative and imaginative future-oriented cultural activities, in interplay with co-innovation processes and entrepreneurial projects. Demonstration trips around the world with solar-powered boots or planes undertaken by public figures considered as ‘adventurer entrepreneurs’ (Livi, Jeannerat, and Crevoisier Citation2014), smart urbanism in cities (Söderström, Paasche, and Klauser Citation2014), or smart farming in rural areas (Pauschinger and Klauser Citation2021) are emblematic of global narratives staged through local experiments. The sustainability projects and ‘slow’ movements developing within and across small towns are another examples (Mayer and Knox Citation2009).

From this perspective, ‘institutionalizing’ appears as a fourth pillar of transformative territorial innovation policies. In the traditional territorial innovation policy paradigm, innovation is mainly conceived of as an institutionalized process, where the primary focus is on spatial ‘down-scale’ institutions that facilitate and direct regional and national innovation along the lines of the global rules of the economy. Institutional ‘relatedness’ and ‘thickness’ have been regarded as local determinants of innovations to address in policymaking (Boschma Citation2017; Zukauskaite, Trippl, and Plechero Citation2017). Perhaps more crucially today, transformative territorial innovation policy mix should conceive of innovation also as an up-scaling, ‘institutionalizing’ process (Fuenfschilling and Truffer Citation2014; Miörner and Binz Citation2020). Institutionalizing innovation can be the outcome of both private and public entities seeking to establish priority agendas and rules and making sense of new cultural horizons.

In innovation system policy, institutionalization is regarded as the triggering or structuring of mature innovations by market norms, whereas in transformative territorial innovation policy, it is an intrinsic process of transformative co-innovation (Fuenfschilling and Truffer Citation2014). From this perspective, territorial innovation policies are themselves evolutive institutions that must adapt to co-innovation processes. Nevertheless, global rules change neither smoothly nor rapidly, as they are the subject of controversies and power decisions. In this sense, from policy target to political arenas, co-innovation must also be conceived of as a tool for multi-scalar transformations that is local and democratic (Huguenin and Jeannerat Citation2017) as well as global and political (Hu and Hassink Citation2015; MacKinnon et al. Citation2019).

3. Conclusion

We live in an innovation society where innovation has become ‘ubiquitous’, ‘heterogenous’ and ‘reflexive’ (Rammert et al. Citation2018). Innovation is to be found all around us in the everyday domains of economy and society. As an overarching concept, it upholds various interpretations and provokes critical debate about its drivers and purposes. Furthermore, it embodies a general approach which gives prominence to questioning and (self-) reflection around what could be (done) rather than what is (being done) in order to transform established activities and practices and to tackle the ‘grand challenges’ of sustainability (Coenen, Hansen, and Rekers Citation2015).

Since the postwar era, the value of innovation has increasingly been disconnected from material production factors. Policies have given prominence to technological, human and financial capital, and have minimized the importance and limits of material resources for innovation-based competitive advantage. Global SDGs require the reintroduction of these material resources and their limitation as a primary innovation driver. This does not only concern sustaining production conditions but also sustaining consumption and living conditions. In line with the arguments exposed in this paper, two main issues should be addressed for the future of regional studies.

The first issue is to further develop research and conceptualizations on territorial value and territorial valuation processes at stake in innovation. Nowadays, innovation consists in redesigning economic models based on the cultural aspirations of society, i.e. in translating global challenges into local multi-contributive activities. Innovation that tends to diminish resources or to degrade the quality of life should be abandoned. Territorial value should thus be redefined as the capacity of a region, city or nation to regenerate or to grow its natural, human and built resources.

In this view, regional innovation studies and policymaking should focus on the local anchoring of experiments. This is not an easy task and must be organized across places and scales. A general research agenda would be to further investigate the value of innovation in relationship with enlarged anchoring milieus that contribute to positive interdependencies between export-, visitor- and household-based income systems. Territorial innovation policy mixes should seek to re-associate physical and cultural resources valued by and across interdependent production, consumption and living activities.

The second main issue relates to the role of the social sciences and humanities (SHS) in innovation, particularly regarding the co-innovation, entrepreneurship, sensemaking and institutionalization pillars of territorial innovation policy emphasized above. As sciences in society, SSH innovate within society and not in laboratories, and are present throughout the innovation process: (i) at an implementation level, they transform the inventions developed by Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) into products and market experiences; (ii) culturally, they create shared meaning and values that make it possible to imagine and initiate economic and social change; (iii) at a social, political and institutional level, they allow innovations to be disseminated and oriented in a desirable direction. In this sense, the role of SSH should be profoundly reconsidered when questioning and investigating these transformative issues for territorial innovation policy (Moulaert et al. Citation2017; Jeannerat et al. Citation2020; Foulds and Robison Citation2018).

The study of SSH is usually confined to critical observers of innovation, or to disciplines which accompany the technoscientific inventions of the STEM disciplines (Kitson Citation2019). Through the research they conduct and the training they provide, SSH encourages the identification and emergence of innovation opportunities, enabling innovations to acquire both monetary and cultural value. From this perspective, regional studies are called upon to play not merely a supporting but rather a participating and animating role in all innovation policies.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ariane Huguenin for her inspiring early thoughts.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Asheim, B. 1996. “Industrial Districts as ‘Learning Regions’: A Condition for Prosperity.” European Planning Studies 4 (4): 379–400. doi:10.1080/09654319608720354

- Asheim, B. 2007. “Differentiated Knowledge Bases and Varieties of Regional Innovation Systems.” Innovation – The European Journal of Social Science Research 20 (3): 223–241. doi:10.1080/13511610701722846

- Bailey, D., and L. De Propris. 2020. “Industry 4.0 and Transformative Regional Industrial Policy.” In Industry 4.0 and Regional Transformations, edited by L. De Propris and D. Bailey, 238–252. Abington: Routeledge.

- Bailey, D., C. Pitelis, and P. Tomlinson. 2018. “A Place-Based Developmental Regional Industrial Strategy for Sustainable Capture of Co-created Value.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 42 (6): 1521–1542. doi:10.1093/cje/bey019

- Balsiger, P. 2021. “The Dynamics of ‘Moralized Markets’: A Field Perspective.” Socio-Economic Review 19 (1): 59–82. doi:10.1093/ser/mwz051

- Binz, C., and B. Truffer. 2017. “Global Innovation Systems – A Conceptual Framework for Innovation Dynamics in Transnational Contexts.” Research Policy 46 (7): 1284–1298. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2017.05.012

- Binz, C., B. Truffer, and L. Coenen. 2016. “Path Creation as a Process of Resource Alignment: Industry Formation for On-site Water Recycling in Beijing.” Economic Geography 92 (2): 172–200. doi:10.1080/00130095.2015.1103177

- Boschma, R. 2017. “Relatedness as Driver of Regional Diversification: A Research Agenda.” Regional Studies 51 (3): 351–364. doi:10.1080/00343404.2016.1254767

- Camagni, R. 1991. Innovation Networks: Spatial Perspectives. London: Belhaven Press.

- Camagni, R. 2016. “Urban Development and Control on Urban Land Rents.” The Annals of Regional Science 56 (3): 597–615. doi:10.1007/s00168-015-0733-6.

- Carvalho, L. 2015. “Smart Cities from Scratch? A Socio-technical Perspective.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 8 (1): 43–60. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsu010

- Carvalho, L., and I. Lazzerini. 2018. “Anchoring and Mobility of Local Energy Concepts: The Case of Community Choice Aggregation (CCA).” In Beyond Experiments: Understanding How Climate Governance Innovations Become Embedded, edited by B. Turnheim, P. Kivimaa, and F. Berkhout, 49–68. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Coenen, L., P. Benneworth, and B. Truffer. 2012. “Towards a Spatial Perspective on Sustainability Transitions.” Research Policy 41: 968–979. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2012.02.014

- Coenen, L., T. Hansen, and J. Rekers. 2015. “Innovation Policy for Grand Challenges. An Economic Geography Perspective.” Geography Compass 9 (9): 483–496. doi:10.1111/gec3.12231

- Cooke, P. 1992. “Regional Innovation Systems: Competitive Regulation in the New Europe.” Geoforum: Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 23 (3): 365–382. doi:10.1016/0016-7185(92)90048-9

- Cooke, P. 2008. “Regional Innovation Systems: Origin of the Species.” International Journal of Technological Learning, Innovation and Development 1 (3): 393–409. doi:10.1504/IJTLID.2008.019980

- Cooke, P., and L. Lazzeretti. 2008. Creative Cities, Cultural Clusters and Local Economic Development. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Costa, P. 2017. “Bairro Alto Revisited: Sustainable Innovations, Reputation Building and Urban Development.” In Sustainable Innovation and Regional Development: Rethinking Innovative Milieus, edited by L. Kebir, O. Crevoisier, P. Costa, and V. Peyrache-Gadeau, 127–152. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Crevoisier, O. 2016. “The Economic Value of Knowledge: Embodied in Goods or Embedded in Cultures?” Regional Studies 50 (2): 189–201. doi:10.1080/00343404.2015.1070234

- Crevoisier, O., and H. Jeannerat. 2009. “Territorial Knowledge Dynamics: From the Proximity Paradigm to Multi-location Milieus.” European Planning Studies 17 (8): 1223–1241. doi:10.1080/09654310902978231

- Crevoisier, O., and D. Rime. 2021. “Anchoring Urban Development: Globalisation, Attractiveness and Complexity.” Urban Studies 58 (1): 36–52. doi:10.1177/0042098019889310

- Dewald, U., and T. Truffer. 2012. “The Local Sources of Market Formation: Explaining Regional Growth Differentials in German Photovoltaic Markets.” European Planning Studies 20 (3): 397–420. doi:10.1080/09654313.2012.651803

- Dewey, J. 1946. The Public and Its Problems. An Essay in Political Inquiry. Chicago: Gateway.

- Diercks, G., H. Larsen, and F. Steward. 2019. “Transformative Innovation Policy: Addressing Variety in an Emerging Policy Paradigm.” Research Policy 48 (4): 880–894. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2018.10.028

- Doloreux, D. 2002. “What We Should Know About Regional Systems of Innovation.” Technology in Society 24 (3): 243–263. doi:10.1016/S0160-791X(02)00007-6

- Dosi, G., C. Freeman, R. Nelson, G. Silverberg, and L. Soete. 1988. Technical Change and Economic Theory. London: Pinter.

- Edquist, C. 1997. Systems of Innovation: Technologies, Institutions and Organizations. London: Pinter.

- Flanagan, K., and E. Uyarra. 2016. “Four Dangers in Innovation Policy Studies – And How to Avoid Them.” Industry and Innovation 23 (2): 177–188. doi:10.1080/13662716.2016.1146126

- Florida, R. 1995. “Toward the Learning Region.” Futures 27 (5): 527–536. doi:10.1016/0016-3287(95)00021-N

- Florida, R. 2005. Cities and the Creative Class. New York: Routledge.

- Foray, D., P. David, and B. Hall. 2009. Smart Specialisation – The Concept. Knowledge Economists Policy Brief Number 9, June. Brussels: European Commission, DG Research.

- Foray, D., and C. Freeman. 1993. Technology and the Wealth of Nations. London: Pinter.

- Foulds, C., and R. Robison. 2018. Advancing Energy Policy Lessons on the Integration of Social Sciences and Humanities. Cham: Palgrave.

- Fuenfschilling, L., and B. Truffer. 2014. “The Structuration of Socio-technical Regimes: Conceptual Foundations from Institutional Theory.” Research Policy 43 (4): 772–791. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2013.10.010

- Geels, F. 2002. “Technological Transitions as Evolutionary Reconfiguration Processes: A Multi-level Perspective and a Case-Study.” Research Policy 31 (8): 1257–1274. doi:10.1016/S0048-7333(02)00062-8

- Geels, F., and J. Schot. 2007. “Typology of Sociotechnical Transition Pathways.” Research Policy 36 (3): 399–417. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2007.01.003

- Gill, R., A. Pratt, and T. Virani. 2019. Creative Hubs in Question: Place, Space and Work in the Creative Economy. London: Palgrave.

- Godin, B. 2017. Models of Innovation: The History of an Idea. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Grabher, G. 2002. “Cool Projects, Boring Institutions: Temporary Collaboration in Social Context.” Regional Studies 36: 205–214. doi:10.1080/00343400220122025

- Grillitsch, M., and M. Sotarauta. 2020. “Trinity of Change Agency, Regional Development Paths and Opportunity Spaces.” Progress in Human Geography 44: 704–723. doi:10.1177/0309132519853870

- Guex, D., and O. Crevoisier. 2015. “A Comprehensive Socio-economic Model of the Experience Economy: The Territorial Stage.” In Spatial Dynamics in the Experience Economy, edited by A. Lorentzen, L. Schrøder, and K. Topsø Larsen, 119–138. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Hassink, R. 2020. “Advancing Place-Based Regional Innovation Policies.” In Regions and Innovation Policies in Europe: Learning from the Margins, edited by M. González-López and B. Asheim, 30–45. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Heiberg, J., B. Binz, and B. Truffer. 2020. The Geography of Technology Legitimation: How Multi-scalar Legitimation Processes Matter for Path Creation in Emerging Industries. Papers in Evolutionary Economic Geography, 2020/34. Utrecht: Utrecht University – Human Geography and Planning.

- Hipp, A., and C. Binz. 2020. “Firm Survival in Complex Value Chains and Global Innovation Systems: Evidence from Solar Photovoltaics.” Research Policy 49 (1). doi:10.1016/j.respol.2019.103876

- Hu, X., and R. Hassink. 2015. “Explaining Differences in the Adaptability of Old Industrial Areas.” In Routledge Handbook of Politics and Technology, edited by U. Hilpert, 162–172. London: Routeldge.

- Huguenin, A. 2017. “Transition énergétique et territoire: une approche par le « milieu valuateur ».” Géographie, économie, société 19 (1): 33–53. doi:10.3166/ges.19.2017.0002

- Huguenin, A., and H. Jeannerat. 2017. “Creating Change Through Pilot and Demonstration Projects: Towards a Valuation Policy Approach.” Research Policy 46: 624–635. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2017.01.008

- Jeannerat, H., O. Crevoisier, G. Brulé, and C. Suter. 2020. L’apport des sciences humaines et sociales à l’innovation en Suisse. Étude dans le cadre du rapport « Recherche et innovation en Suisse 2020 » Partie C, étude 2. Berne: Secrétariat d’Etat à la formation, la recherche et l’innovation SEFRI.

- Jeannerat, H., T. Haisch, O. Crevoisier, and H. Mayer. 2017. Pour une politique de communs innovatifs, Papier de perspectives, INNO-Futures: Universités de Neuchâtel et Berne. www.communs-innovatifs.ch

- Jeannerat, H., and L. Kebir. 2016. “Knowledge, Resources and Markets: What Economic System of Valuation?” Regional Studies 50 (2): 274–288. doi:10.1080/00343404.2014.986718

- Kebir, L., and O. Crevoisier. 2008. “Cultural Resources and the Regional Development: The Case of the Cultural Legacy of Watchmaking.” In Creative Cities, Cultural Clusters and Local Economic Development, edited by P. Cooke and L. Lazzeretti, 48–69. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Kebir, L., O. Crevoisier, P. Costa, and V. Peyrache-Gadeau. 2017. “Introduction: Sustainability, Innovative Milieus and Territorial Development.” In Sustainable Innovation and Regional Development: Rethinking Innovative Milieus, edited by L. Kebir, O. Crevoisier, P. Costa, and V. Peyrache-Gadeau, 1–24. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Kitson, M. 2019. “Innovation Policy and Place: A Critical Assessment.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 12 (2): 293–315. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsz007.

- Kuhlmann, S., and A. Rip. 2018. “Next-Generation Innovation Policy and Grand Challenges.” Science and Public Policy 45 (4): 448–454. doi:10.1093/scipol/scy011

- Lagendijk, A. 2006. “Learning from Conceptual Flow in Regional Studies: Framing Present Debates, Unbracketing Past Debates.” Regional Studies 40 (4): 385–399. doi:10.1080/00343400600725202

- Lagendijk, A. 2011. “Regional Innovation Policy Between Theory and Practice.” In Handbook of Regional Innovation and Growth, edited by P. Cooke, B. Asheim, R. Boschma, R. Martin, D. Schwartz, and F. Tödtling, 597–608. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Landau, R., and N. Rosenberg. 1986. The Positive Sum Strategy: Harnessing Technology for Economic Growth. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

- Landry, C. 2000. The Creative City: Toolkit for Urban Innovation. London: Earthscan Publications.

- Lash, S., and J. Urry. 1994. Economies of Signs and Spaces. London: Sage.

- Lazzeretti, L. 2012. Creative Industries and Innovation in Europe: Concepts, Measures and Comparative Case Studies. London: Routledge.

- Livi, C., H. Jeannerat, and O. Crevoisier. 2014. “From Regional Innovation to Multi-local Valuation Milieus: The Case of the Western Switzerland Photovoltaic Industry.” In The Social Dynamics of Innovation, Networks, edited by R. Rutten, P. Benneworth, D. Irawati, and F. Boekema, 23–41. London: Routledge.

- Loorbach, D., J. Wittmayer, F. Avelino, T. von Wirth, and N. Frantzeskaki. 2020. “Transformative Innovation and Translocal Diffusion.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 35: 251–260. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2020.01.009

- Lorentzen, A., and H. Jeannerat. 2013. “Editorial: Urban and Regional Studies in the Experience Economy: What Kind of Turn?” European Urban and Regional Studies 20 (4): 363–369. doi:10.1177/0969776412470787

- Lundvall, B-Å. 1985. Product Innovation and User-Producer Interaction. Aalborg: Aalborg Universitetsforlag.

- Lundvall, B. 2010. National Systems of Innovation: Toward a Theory of Innovation and Interactive Learning. London: Anthem Press.

- Lundvall, B., and B. Johnson. 1994. “The Learning Economy.” Journal of Industry Studies 1 (2): 23–42. doi:10.1080/13662719400000002

- MacKinnon, D., S. Dawley, A. Pike, and A. Cumbers. 2019. “Rethinking Path Creation: A Geographical Political Economy Approach.” Economic Geography 95 (2): 113–135. doi:10.1080/00130095.2018.1498294

- Maillat, D. 1998. “Innovative Milieux and New Generations of Regional Policies.” Entrepreneurship and Regional Development 10: 1–16. doi:10.1080/08985629800000001

- Maillat, D., and L. Kebir. 2011. “The Learning Region and Territorial Production Systems.” In Theories of Endogenous Regional Growth. Advances in Spatial Science, edited by B. Johansson, C. Karlsson, and R. Stough, 255–277. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.

- Manniche, J., and B. Sæther. 2017. “Emerging Nordic Food Approaches.” European Planning Studies 25 (7): 1101–1110. doi:10.1080/09654313.2017.1327036

- Manniche, J., K. Topsø Larsen, and R. Brandt Broegaard. 2021. “The Circular Economy in Tourism: Transition Perspectives for Business and Research.” Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism 21 (3): 247–264. doi:10.1080/15022250.2021.1921020

- Markard, J., R. Raven, and B. Truffer. 2012. “Sustainability Transitions: An Emerging Field of Research and Its Prospects.” Research Policy 41 (6): 955–967. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2012.02.013

- Martin, R., and P. Sunley. 2003. “Deconstructing Clusters: Chaotic Concept or Policy Panacea?” Journal of Economic Geography 3 (1): 5–35. doi:10.1093/jeg/3.1.5

- Mayer, H., and P. Knox. 2010. “Small-Town Sustainability: Prospects in the Second Modernity.” European Planning Studies 18 (10): 1545–1565. doi:10.1080/09654313.2010.504336

- Mazzucato, M., R. Kattel, and J. Ryan-Collins. 2020. “Challenge-Driven Innovation Policy: Towards a New Policy Toolkit.” Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade 20: 421–437. doi:10.1007/s10842-019-00329-w

- McCann, P., and R. Ortega-Argilés. 2013. “Modern Regional Innovation Policy.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 6 (2): 187–216. doi:10.1093/cjres/rst007

- Miörner, J., and C. Binz. 2020. Toward a Multi-scalar Perspective of Transition Trajectories. Papers in Innovation Studies, 2020/10. Lund: Centre for Innovation Research – Lund University.

- Morgan, K. 2016. “Nurturing Novelty: Regional Innovation Policy in the Age of Smart Specialization.” Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 35 (4): 569–583. doi:10.1177/0263774X16645106

- Moulaert, F. 2009. “Social Innovation: Institutionally Embedded, Territorially.” In Social Innovation and Territorial Development, edited by D. MacCallum, F. Moulaert, K. Hiller, and V. Haddock, 11–24. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Moulaert, F., A. Mehmood, D. MacCallum, and B. Leubolt. 2017. Social Innovation as a Trigger for Transformations – The Role of Research. Brussels: European Commission.

- Moulaert, F., and F. Sekia. 2003. “Territorial Innovation Models: A Critical Survey.” Regional Studies 37: 289–302. doi:10.1080/0034340032000065442

- Nevens, F., N. Frantzeskaki, L. Gorissen, and D. Loorbach. 2013. “Urban Transition Labs: Co-creating Transformative Action for Sustainable Cities.” Journal of Cleaner Production 50: 111–122. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.12.001

- OECD. 2011. OECD at 50: Evolving Paradigms in Economic Policy Making, OECD Economic Outlook, 2011/1. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Orléan, A. 2011. L’empire de la valeur: refonder l’économie. Paris: Le Seuil.

- Owen, R., P. Macnaghten, and J. Stilgoe. 2012. “Responsible Research and Innovation: From Science in Society to Science for Society, with Society.” Science and Public Policy 39 (6): 751–760. doi:10.1093/scipol/scs093

- Pauschinger, D., and F. Klauser. 2021. “The Introduction of Digital Technologies into Agriculture: Space, Materiality and the Public–Private Interacting Forms of Authority and Expertise.” Journal of Rural Studies. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.06.015.

- Peck, J. 2005. “Struggling with the Creative Class.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 29 (4): 740–770. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2005.00620.x

- Perez, C. 2013. “Innovation Systems and Policy for Development in a Changing World.” In Innovation Studies. Evolution and Future Challenges, edited by J. Fagerberg, B. Martin, and E. Sloth Andersen, 90–110. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Porter, M. E. 1998. “Clusters and the New Economics of Competition.” Harvard Business Review 76 (6): 77–90.

- Power, D., and A. Scott. 2004. Cultural Industries and the Production of Culture. London: Routledge.

- Pratt, A. 2009. “Urban Regeneration: From the Arts ‘Feel Good’ Factor to the Cultural Economy: A Case Study of Hoxton, London.” Urban Studies 46 (5–6): 1041–1061. doi:10.1177/0042098009103854

- Pratt, A., and P. Jeffcutt. 2009. Creativity, Innovation and the Cultural Economy. London: Routledge.

- Rammert, W., A. Windeler, H. Knoblauch, and M. Hutter. 2018. “Expanding the Innovation Zone.” In Innovation Society Today: Perspectives, Fields, and Cases, edited by W. Rammert, A. Windeler, H. Knoblauch, and M. Hutter, 3–12. Wiesbaden: Springer.

- Rutten, R., and F. Boekema. 2012. “From Learning Region to Learning Socio-spatial Context.” Regional Studies 46 (8): 981–992. doi:10.1080/00343404.2012.712679

- Ryghaug, M., and T. Skjølsvold. 2021. Pilot Society and the Energy Transition, the Co-shaping of Innovation, Participation and Politics. Cham: Palagrave Pivot.

- Schmidt, S., F. Müller, O. Ibert, and V. Brinks. 2018. “Open Region: Creating and Exploiting Opportunities for Innovation at the Regional Scale.” European Urban and Regional Studies 25 (2): 187–205. doi:10.1177/0969776417705942

- Schot, J., and W. Steinmueller. 2018. “Three Frames for Innovation Policy: R&D, Systems of Innovation and Transformative Change.” Research Policy 47 (9): 1554–1567. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2018.08.011

- Scott, A. 1988. “Flexible Production Systems and Regional Development: The Rise of New Industrial Space in North America and Western Europe.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 12: 171–186. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.1988.tb00448.x

- Scott, A., and M. Storper. 1992. “Le développement régional reconsidéré.” Espaces et sociétés 66 (1): 7–38. doi:10.3917/esp.1992.66.0007

- Segessemann, A., and O. Crevoisier. 2016. “Beyond Economic Base Theory: The Role of the Residential Economy in Attracting Income to Swiss Regions.” Regional Studies 50: 1388–1403. doi:10.1080/00343404.2015.1018882

- Sengers, F., and R. Raven. 2015. “Toward a Spatial Perspective on Niche Development: The Case of Bus Rapid Transit.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 17: 166–182. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2014.12.003

- Sharif, N. 2006. “Emergence and Development of the National Innovation Systems Concept.” Research Policy 35: 745–766. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2006.04.001

- Shearmur, R., and D. Doloreux. 2015. “Knowledge-Intensive Business Services (KIBS) Use and User Innovation: High-Order Services, Geographic Hierarchies and Internet Use in Quebec's Manufacturing Sector.” Regional Studies 49 (10): 1654–1671. doi:10.1080/00343404.2013.870988

- Simmie, J., and S. Strambach. 2006. “The Contribution of Knowledge-Intensive Business Services (KIBS) to Innovation in Cities: An Evolutionary and Institutional Perspective.” Journal of Knowledge Management 10 (5): 26–40. doi:10.1108/13673270610691152

- Smith, A., T. Hargreaves, S. Hielscher, M. Martiskainen, and G. Seyfang. 2016. “Making the Most of Community Energies: Three Perspectives on Grassroots Innovation.” Environment and Planning A 48 (2): 407–432. doi:10.1177/0308518X15597908

- Söderström, O., T. Paasche, and F. Klauser. 2014. “Smart Cities as Corporate Storytelling.” City 18 (3): 307–320. doi:10.1080/13604813.2014.906716

- Soete, L., B. Verspagen, and B. Ter Weel. 2010. “Systems of Innovation.” In Handbook of the Economics of Innovation, edited by B. Hall and N. Rosenberg, Vol. 2, 11259–11802. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Srnicek, N. 2017. Platform Capitalism. London: Polity Press.

- Stam, E., and F. Welter. 2021. “Geographical Contexts of Entrepreneurship: Spaces, Places and Entrepreneurial Agency.” In The Psychology of Entrepreneurship: The Next Decade, edited by M. Gielnik, M. Frese, and M. Cardon, 263–281. London: Routeledge.

- Strambach, S. 2008. “Knowledge-Intensive Business Services (KIBS) as Drivers of Multilevel Knowledge Dynamics.” International Journal Services Technology and Management 10 (2/3/4): 152–174. doi:10.4337/9781784712211.00011.

- Strambach, S., and F. Lindner. 2017. “Crossing Sustainable Innovation Processes – German Knowledge-Intensive Business Services (KIBS) in Green Construction.” In Sustainable Innovation and Regional Development: Rethinking Innovative Milieus, edited by L. Kebir, O. Crevoisier, P. Costa, and V. Peyrache-Gadeau, 63–85. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Talandier, M. 2020. “Les activités productives locales, un enjeu d'intermédiation et de résilience: des KIBS (knowledge intensive business services) aux LIBS (local intensive business services).” Géographie, Economie et Société 22 (3-4): 305–327. doi:10.3166/ges.2020.0014.

- Thiel, J., and G. Grabher. 2015. “Crossing Boundaries: Exploring the London Olympics 2012 as a Field-Configuring Event.” Industry and Innovation 22 (3): 229–249. doi:10.1080/13662716.2015.1033841

- Tödtling, F., and M. Trippl. 2018. “Regional Innovation Policies for New Path Development – Beyond Neo-liberal and Traditional Systemic Views.” European Planning Studies 26 (9): 1779–1795. doi:10.1080/09654313.2018.1457140

- United Nations. 2020. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2020. New York: United Nations Publications.

- Uyarra, E., and K. Flanagan. 2021. “Going Beyond the Line of Sight: Institutional Entrepreneurship and System Agency in Regional Path Creation.” Regional Studies. doi:10.1080/00343404.2021.1980522.

- Van Der Have, R., and L. Rubalcabac. 2016. “Social Innovation Research: An Emerging Area of Innovation Studies.” Research Policy 45 (9): 1923–1935. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2016.06.010

- Van Winden, W., and L. Carvalho. 2019. “Intermediation in Public Procurement of Innovation: How Amsterdam’s Startup-in-Residence Programme Connects Startups to Urban Challenges.” Research Policy 48: 9. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2019.04.013

- Von Hippel, E. 2005. Democratizing Innovation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Von Hippel, E. 2016. Free Innovation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Von Wirth, T., L. Fuenfschilling, N. Frantzeskaki, and L. Coenen. 2019. “Impacts of Urban Living Labs on Sustainability Transitions: Mechanisms and Strategies for Systemic Change Through Experimentation.” European Planning Studies 27 (2): 229–257. doi:10.1080/09654313.2018.1504895

- Weber, K., and H. Rohracher. 2012. “Legitimizing Research, Technology and Innovation Policies for Transformative Change: Combining Insights from Innovation Systems and Multi-Level Perspective in a Comprehensive ‘Failures’ Framework.” Research Policy 41: 1037–1047. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2011.10.015

- Xiao, S., B. Truffer, L. Deyu, and Heimeriks Gaston. 2020. “From Knowledge-Based Catching up to Valuation Focused Development: Emerging Strategy Shifts in the Chinese Solar Photovoltaic Industry.” Papers in Evolutionary Economic Geography 20(59). Utrecht: Utrecht University – Human Geography and Planning.

- Zukauskaite, E., M. Trippl, and M. Plechero. 2017. “Institutional Thickness Revisited.” Economic Geography 93 (4): 325–345. doi:10.1080/00130095.2017.1331703