ABSTRACT

Regional restructuring in the context of societal dynamics involves the development of several, possibly interacting regional industrial paths. Conceptualizations in evolutionary economic geography and innovation studies analyze the effects of relating regional industrial paths in the same regional or national context. While policy makers at EU, national and regional scales support research and development of transformative activities in different regions across countries, scholarly contributions on interpath relations across regions and the role of regional preconditions to enable paths in shaping them are scarce. This article combines recent conceptualizations of interpath relations within regions with considerations about the multi-scalarity of asset availability and modification to conceptualize interpath relations across regions. A framework is developed to explain how reinforcing or impeding effects of interpath relations across regions are related to regional preconditions. Empirically, transformative food sector innovations initiated to tackle societal challenges are investigated as an under-researched topic in the path development literature. Two case studies in a peripheral and a core region provide exemplified results about regional differences in supporting asset modification at multiple scales and demonstrate reinforcing or impeding effects for path development resulting from interpath relations across regions. The article offers policy recommendations and presents avenues for further research.

Introduction

In light of rising societal challenges, policy makers increasingly aim to support research about and the development of transformative activities evolving around new technologies or other innovations that promise to enable regional structural change towards sustainability in different regions across countries. Since more than a decade, it has been argued that regional restructuring to meet societal challenges necessitates the development and interaction of several paths based on different innovative and more sustainable solutions (Stern Citation2007). Relations between different existing and emerging industrial entities (i.e. technologies, paths, or technological innovation systems) have been studied to better understand and conceptualize the effects of complementarities and synergies as well as competitive relations on regional industrial activities (Sandén and Hillman Citation2011; Bergek et al. Citation2015; Boschma et al. Citation2017; Steen and Hansen Citation2018; Frangenheim, Trippl, and Chlebna Citation2020). So far, however, they focussed on relations between different paths in the same regional or national context. This ignores that assets needed for path development in different regions, such as human or financial resources or institutional settings also come from or are modified at national or international sources and scales, which points to interpath relations not only within but also across regions and countries. More recent contributions point to various cumulative or combined effects of interpath dynamics to better account for their impact on whole regions (Breul, Hulke, and Kalvelage Citation2021; Chlebna, Martin, and Mattes Citation2021). Our knowledge on regional preconditions to enable or support regional industrial paths to shape interpath relations across regions is, however, limited.

In this analysis, I draw on contributions of evolutionary economic geography (EEG) and the regional innovation system (RIS) literature to consider how regional preconditions enable path development to benefit from assets at multiple scales. Combining these insights with conceptualizations of interpath relations, the distribution of agency and the multi-scalarity of asset availability and modification, I provide a framework that explains how regional preconditions shape the outcome of interpath relations across regions. Empirically, the article is positioned within the growing debate on transformative activities from the food sector as expressed in diverse international policy initiativesFootnote1 and research projects (e.g. Wepner et al. Citation2018; Engelhardt, Brüdern, and Deppe Citation2020). Strengthening this topic in EEG, I acknowledge the recent wave of food sector innovations that aim to tackle urgent societal challenges around climate change, biodiversity loss and healthy nutrition of a growing world population. Comparing findings from two case studies of early path development located in an urban and a peripheral region in the same national context, my aim is further to contribute to knowledge development of the changing urban–rural geography in the food sector, where cities increasingly position themselves as new centres of innovation in the otherwise peripherally characterized sector. With the article, I seek to answer the following research questions: How are reinforcing or impeding effects of interpath relations across regions generated? How affect regional preconditions the outcome of interpath relations across regions?

The article proceeds by discussing conceptualizations of EEG and innovation studies about industrial change, interpath dynamics and regional preconditions. Carving out multi-scalar mechanisms and systemic relations between actor networks and assets, considerations about interpath relations within regions will be complemented by those across regions. The theoretical part concludes with regional preconditions to modify assets at multiple scales and compiles the conceptual framework. The testing of the conceptual framework is undertaken with two case studies, the diversification of aquaculture towards recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS) originating in the peripheral region of Waldviertel, Lower Austria and the creation of an insect-based food and feed path originating in the capital city of Vienna. The concluding section summarizes the results, provides policy recommendations and avenues for further research.

Interpath dynamics and regional preconditions

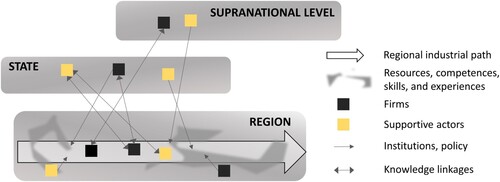

EEG explains the emergence, growth, transformation and decline of industries by acknowledging its dependence on previously developed industrial structures in territorial contexts (Martin Citation2010). A regional industrial path () is represented by related firms and supportive actors. It is stimulated or enabled by place-specific resources, competences, skills, and experiences obtained from previous rounds of path development (Frenken, van Oort, and Verburg Citation2007; Martin Citation2010). New path development additionally depends on institutions and policy interventions of local and non-local organizations as well as knowledge linkages to actors across scales (Binz, Truffer, and Coenen Citation2016; Trippl, Grillitsch, and Isaksen Citation2018).

This section first reflects on current accounts of industrial change and interpath relations and adds considerations on the generation of reinforcing or impeding effects of interpath relations. To better understand industrial dependencies across regions, it carves out what is known by EEG and innovation studies regarding the multi-scalarity of assets. Finally, it provides an overview of knowledge on regional preconditions to access and modify assets at multiple scales and compiles the theoretical pieces for the conceptual framework.

Processes of industrial change and interpath relations

EEG and innovation studies provide broad insights on regional preconditions, generic mechanisms, agentic processes, multiple actors and assets involved in regional industrial path development (Isaksen and Trippl Citation2016; Boschma Citation2017; Isaksen et al. Citation2019; MacKinnon et al. Citation2019; Grillitsch and Sotarauta Citation2020). Inherent to the path development literature is the resource-based view explaining economic competitiveness with the access to and control over assets possibly also needed by other industrial activities (Maskell and Malmberg Citation1999b). To understand path development in a broad and comprehensive manner, recent accounts relate to Maskell and Malmberg (Citation1999b) who identify five types of assets: (i) human and (ii) industrial knowledge and skills, (iii) infrastructural and material assets in the shape of financial resources, (iv) natural resources and (v) formal and informal institutional assets, such as norms and values. To better understand the dynamics of path development, time-wise historical and future processes of asset development, erosion, and substitution (Maskell and Malmberg Citation1999a) are reflected in agentic processes of asset modification, more specifically the reuse, creation or destruction of assets (Trippl et al. Citation2020).

Interpath relations are conceptualized as resulting from the same asset needs. Whether their effects are reinforcing or impeding for regional industrial path development, arguably depends on the outcome of agentic processes of asset modification. In dynamic processes of path development, agency is understood as being distributed among firm and firm-related actors, scientific organizations and those of collective agency from the state, governance and community (Boschma et al. Citation2017; Isaksen et al. Citation2019). Acknowledging the distribution of agency among different actor groups, Frangenheim, Trippl, and Chlebna (Citation2020) argue that assets (and markets) needed for path development are not only modified by agents working for the focal path but also by those working for other paths. Actors’ involvement in distributed agency then again is unstable and with different degrees (Garud and Karnøe Citation2003) and the intentions and meanings of actors engaging in agentic processes are negotiated and reframed (Pesch Citation2015). Assets, therefore, tend to be interpreted towards, oriented at and used by specific paths, which in turn means that other paths may have limited access to them or that the modification of such assets is to the detriment of those paths. Examples are for what kind of use financial resources are available for, at which paths education, industrial standards or infrastructures are oriented at or how laws are interpreted or used. While reinforcing effects may increase the attention of path actors, impeding effects may let them reorient towards other assets and possibly also towards other, more reinforcing interpath relations.

The modification of assets by other paths, e.g. new or adapted policy interventions or regulations, elements in educational schemes, regional infrastructures or shifting consumer preferences, may however not only change the access to or orientation of single assets. Though empirical evidence suggests that in early path development stages the modification of institutions is crucial, further asset modification for path development happens in parallel, overlapping and intertwined processes of asset reuse, creation and destruction (Rypestøl et al. Citation2021). Due to the inter-connectedness of functionally related asset stocks with its needed coordination and learning between assets at multiple scales (Maskell and Malmberg, Citation1999a), concerned paths have to (re-)interpret, (re-)orient and (re-)use the remaining asset base by complementary asset modification. Hence, the outcomes of many asset modifications in the context of industrial restructuring processes affect whether and which interpath relations are reinforcing or impeding for regional industrial path development. Before elaborating on the regional preconditions to enable paths to (complementary) modify assets across scales, the next section compiles insights on the availability and modification of assets at regional, national and international scales.

Multi-scalarity of asset availability and modification

Contributions pointing out the role of extra-regional companies and skilled individuals, innovation partnerships across regions and financial or institutional assets at higher scales for regional industrial change processes (Binz, Truffer, and Coenen Citation2016; Trippl, Grillitsch, and Isaksen Citation2018) indicate the need to broaden the debate about interpath relations beyond single regions. Indeed, a regional industrial path distinguishes from other paths by specific actors’ compositions and networks, regulations, values and norms, as well as access to policy and financial support. Nevertheless, different regional paths may have similarities in multi-scalar asset needs. The recent literature at the intersection of EEG, geographical political economy and innovation system studies has brought forward valuable frameworks that contribute to a comprehensive and integrative understanding of multi-scalar industrial change processes (Binz and Truffer Citation2017; MacKinnon et al. Citation2019). Gaining from the broad collection of insights, I deepen what MacKinnon et al. (Citation2019) summarize as regional and extra-regional assets and distinguish between regionally, nationally and internationally available assets. Moreover, while being consistent with the broad consideration of resources or assets formed in industrial development processes (Binz and Truffer Citation2017; MacKinnon et al. Citation2019), I focus on the outcome of agentic processes of asset modification distributed among actors of different paths. I argue that the availability, orientation, or interpretation of assets at multiple scales affect the orientation of path development. This is not to claim that interpath relations are a static phenomenon. To the contrary, earlier analyzes pointed out the transformability of interpath relations (Bergek et al. Citation2015; Frangenheim, Trippl, and Chlebna Citation2020). Asset interpretation, orientation and use as a result of interpath relations are subject to change over time. Hence, the same applies to the orientation of paths towards assets and interpath relations.

Different types of assets are located and modified at different scales. Due to their inter-connectedness, regional industrial paths orient at complex and context-dependent multi-scalar asset stocks. Natural assets, such as water bodies, wind or solar radiation are available in the region (Isaksen, Langemyr Eriksen, and Rypestøl Citation2020) as far as they are identified, produced or used through knowledge interaction with actors from the same region or from beyond (Andersen Citation2012). Financial or infrastructural assets are positioned at multiple, often national or international scales (Isaksen, Langemyr Eriksen, and Rypestøl Citation2020) and agents modify them thanks to their engagement in regional, national or international political and transdisciplinary committees. Bergek et al. (Citation2015) demonstrate the synergetic development of national funding paired with the feed-in tariff through agents of different renewable energy paths located in different German regions. Human and industrial knowledge and skills need to be harnessed and aligned from within the region as well as from outside through knowledge linkages between firms, industry-university linkages, firm-user interaction or the arrival of new actors (Trippl, Grillitsch, and Isaksen Citation2018). Pflitsch and Radinger-Peer (Citation2018) show how actors of different disciplines and sectors but with shared interests contribute to developing region-specific research topics and integrating sustainability aspects into university’s teaching activities. Finally, institutions exist at various scales (Binz and Truffer Citation2017). Fuenfschilling and Binz (Citation2018) demonstrate with a case study of Chinese wastewater that international institutional assets must be transferred, (re-)interpreted and implemented at national or regional scales. Moreover, institutional rationalities emerge and gain influence beyond their place of origin in the form of international, institutionalized structures, i.e. institutional asset modification undertaken by regional path’ actors also relates to regulative changes at national or supra-national scales.

Regional preconditions for asset accessibility and modification at multiple scales

A conceptual lens to analyze the structural preconditions that influence actors’ involvement, capabilities, knowledge and their networks nurturing path development is the RIS. Besides advocating multi-actor approaches (Isaksen and Trippl Citation2016), RIS studies increasingly point to multi-scalar industrial, political, educational or financial dynamics (Trippl, Grillitsch, and Isaksen Citation2018) and path development has been conceptualized as evolving in an open RIS (Asheim, Isaksen, and Trippl Citation2020). Against this background, it is evident to also look at the regional support structure for modifying assets at national and international scales.

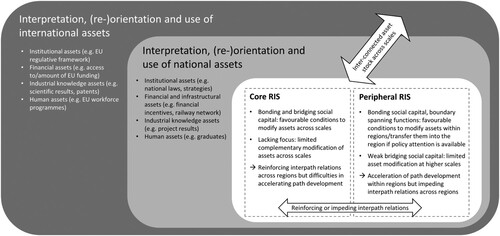

To understand differences in regional preconditions to support paths in modifying assets at multiple scales, the article contrasts a typical RIS of peripheral regions with one of core regions. In the following, idealistic capacities of both RIS types are distinguished and insights will be combined with the multi-scalarity of asset modification to assert their propensity for reinforcing or impeding interpath relations across regions. Adding the considerations of asset interpretation, orientation and use from the point of view of different paths and the need to complementarily modify assets across scales to adapt to or benefit from interpath relations helps building the framework to understand how regional preconditions relate to reinforcing and impeding effects of interpath relations across regions.

Peripheral regions tend to have weak endowments with knowledge generation and diffusion organizations and accordingly little, predominantly local knowledge exchange (Isaksen Citation2015; Isaksen and Trippl Citation2016). Internal coordination and learning between asset modification activities, i.e. building complementarity in asset modification, across scales is therefore limited as well as beneficial modification of human, financial or formal institutional assets at higher scales. Peripheral regions access external opportunities resulting from newly created or adapted assets at higher scales thanks to local organizations with boundary-spanning functions, who contribute to knowledge spillovers and build crucial competence internally by linking to resourceful firms, national or international customers, R&D organizations and experts (Isaksen Citation2015; Isaksen and Trippl Citation2016). Complementary asset modification within the region is likely supported by the existence of networks with strong bonding social capital that keep actors together by similar values and norms (Isaksen and Trippl Citation2016). On the downside, strong bonding ties and the existence of only few industrial paths may limit innovation and change and even risk falling into negative lock-in when regional policy interventions are lastingly oriented at established paths (Isaksen and Trippl Citation2016). While limited asset modification capacities at higher scales make peripheral regions prone to impeding effects of interpath relations across regions, the acceleration of path development as a reaction on externally created or adapted assets is likely through complementary asset modification within the region.

In larger and more centrally located regions, besides bonding social capital also bridging networks exist that link actors from different groups or organizations (Isaksen and Trippl Citation2016), thus providing high potentials for interpath relations. According to Isaksen and Trippl (Citation2016), they are equipped with diverse and geographically open knowledge networks involving providers of information about new markets and technologies, organizations offering counselling services, bridging organizations, technology transfer agencies, incubators, and others. They provide favourable conditions to benefit from assets created or adapted by other paths at multiple scales. As core centres of continuous change, they nonetheless risk exploring new industrial activities without their exploitation due to the existence of multiple paths at different development stages and differing orientation of regional policies. According to Isaksen and Trippl (Citation2016), this may result in a lack of policy focus hindering emerging industries to achieve a critical mass. Moreover, the empirical results of this analysis show that a restrictive focus of policy actors towards existing regulative frameworks may limit modification and reorientation of assets to meet new requirements (cf. structural maintenance agency, Jolly, Grillitsch, and Hansen Citation2020). While emerging paths in core regions might be well equipped to benefit from reinforcing interpath relations across regions, a lack of focus or attention by policy and support organizations can limit complementary asset modification across scales, i.e. adapting the orientation of research and educational programmes, policy support structures, financial sources or laws and regulations accordingly to accelerate path development.

The conceptual framework () understands path development as being stimulated by an open RIS but in need of accessible, interpretable and usable assets at multiple scales. Depending on how well the RIS enables path actors to shape the outcome of asset modification at higher scales, regional industrial paths are rather constrained or reinforced by interpath relations across regions. If needed assets are interpreted for, oriented at or used by extra-regional paths, impeding interpath relations may result in a stagnation or decline of path development (cf. diversification of aquaculture towards RAS in a peripheral region). If assets, modified by extra-regional paths or in cooperation with them, are instead interpreted and oriented in favour of, or possibly used by the regional path, reinforcing interpath relations provide opportunities for path development. Nevertheless, their uptake is not given, if complementary modification of the inter-connected asset stock fails (cf. insect-based food path creation in a core region). As long as reinforcing effects attract the attention of path actors, the path may orient at respective assets. Impeding effects in turn may let path actors reorient towards other assets and possibly also towards other, more reinforcing interpath relations (cf. synergetic relations between aquaculture and insect-based feed).

Methodology of case study comparison

When focussing on a contemporary phenomenon within a real-life context, posing ‘how’ or ‘why’ questions and having limited control over behavioural events, the case study method is the preferred strategy (Yin Citation2009). The selection of cases has been guided by the theoretically developed framework and undertaken by means of a literature and document analysis, as well as three explorative expert interviews with actors from the City of Vienna, a research institute, and a food sector consulting firm. To ensure familiarity with the Austrian food sector and enable the choice of two appropriate cases, emerging Austrian food paths have been investigated as regards the two main conceptual parts of the framework, regional preconditions and interpath relations across regions. Inspired by Seawright and Gerring (Citation2008), two cases that are most similar across their background conditions, relevant to reinforcing or impeding effects of interpath relations across regions, have been selected: Both emerging paths have external relations to other paths within Austria as well as in other EU regions. Both belong to the same sector, their activities are at a very early stage (less than ten years) and they focus on ecological sustainability. How regional preconditions shape interpath relations across regions is exemplary assessed through the comparison of the diversifying aquaculture in the peripheral region of Waldviertel with insect-based food and feed path creation by urban actors located in Vienna.

16 qualitative interviews with experts identified based on the literature review and recommendations followed between June 2019 and September 2020. Interviews included questions structured along three blocks, namely potentials and barriers for path development at different scales, efforts made to support potentials or overcome barriers, other path development activities across regions and how they are supported by regional preconditions. Including site visits, interviews lasted between one and two and a half hours and – apart from one telephone call – they took place at the actors’ premises, where often a visit of the experimental or industrial activities has been possible. Since new path development is in a very early stage lacking established structures, the rather small network of actors exchanges informally at open or closed networking events. During the field studies period, the participation in industrial and policy events allowed for mostly planned, some random fieldwork conversations including ongoing activities by earlier interviewees. Transcribed interviews and systematically documented discussions and presentations at industrial and policy events have been confronted with a coding system, derived from the analytical dimensions of the conceptual framework and complemented empirically where appropriate. Within the qualitative content analysis, re-theorizing helped to consolidate the conceptual framework.

Case rationale

The non-alpine Austrian peripheral regions accommodate large parts of traditional economic activities, such as agricultural production, dairy, meat, milling, bakery, sugar and starch. Established food sector structures with high path dependency are confronted with more and more innovative activities, often originating in cities and aiming to react to urgent societal challenges, such as climate change, loss of biodiversity and an increase in food-related diseases (IR-NAT2). Initiated by Austria’s EU accession in 1995, food sector innovation is also a consequence of the gradual embedding of the sector into the international institutional framework regulated by the EU and WTO, accompanying rising international competition, the accessibility of research programmes and funding. Fish production in RAS and the production of insect protein are among the emerging transformative activities in Austria, which are – despite their only modest number of actors and activities – internationally considered as potentially contributing to the transformation of our food systems (van Huis et al. Citation2013; Engelhardt, Brüdern, and Deppe Citation2020). Both emerging paths belong to the group of small food producers, being associated with the places where they originate, who recently gain public national and EU subsidies. provides an overview of both cases and the consulted empirical material.

Table 1. Case description and empirical material.

Diversification of aquaculture originating in a peripheral region

Fish production in Austria is a small, yet very old sector with over 500 years of fishpond cultivation and 50–60 years of flow-through systems. With 4.250 tons of edible fish produced by 500 aquaculture operators in 2019, the degree of self-sufficiency is only around 6% (AP-NAT2). Carp production traditionally depends on the limited availability of 683 fishponds larger than one hectare (and some not counted smaller ponds) owned by rather few small- and medium-sized family businesses localized in the peripheral regions of Waldviertel, Lower Austria, close to the Czech border, as well as in Southern Styria (AP-NAT1). While carp production stagnates at less than 700 tons per year, trout production in streams or small rivers, mostly located in Upper Austria, Styria and Carinthia, has a slightly larger growth potential (AP-NAT1; AP-REG).

The diversification of aquaculture towards RAS in the peripheral region of Waldviertel has been driven by carp producers and supportive actors who have been involved in the participative development process of the national aquaculture strategy in 2012. This strategy has set ambitious targets to mitigate climate and environment-related challenges, such as rising water temperatures and scarcity and the occurrence of predators, as well as meeting the growing Austrian demand for healthy and sustainable fish products (BMLFUW Citation2012; (AP-REG)). RAS have been identified as most promising in terms of environment-friendly and rising production rates (AP-NAT1) and soon, fish production in RAS has been exported to other Austrian regions. In 2019, 500 tons of regional fish species like carp and zander as well as foreign species like African catfish or tilapia have been produced by 10 bigger RAS operators and some smaller ‘garage projects’ located in Upper Austria, Lower Austria, Vienna and Burgenland and the production rate is predicted to grow (AP-REG).

Regional innovation system preconditions

In the peripheral region of Waldviertel, diverse firm, public and educational actors have been traditionally engaged in fishpond carp production. The RIS supports these activities with a longtime established network of education facilities, a publicly supported research institute and the regional chamber of agriculture. Peripheral carp production has been characterized by strong informal networks with similar values and norms of actors that well support the aquaculture path in incrementally adapting to changing natural foundations of the economy, such as dryness and the occurrence of predators (AP-NAT4; AP-NAT5). A small number of actors and the limited accessibility of natural resources for long time impeded knowledge exchange, experimentation and learning with, or the entry of new actors, therefore, enforcing mere path extension. Firm as well as public interviewees described the established, inward-oriented path as being characterized by informal knowledge transfer and closed regional networks that are neither well organized, nor are they supported by a functioning articulation beyond the region or are scientifically backed (AF2-INT; AF3-REG; AF4-REG; AF5-REG; AP-NAT6).

Successful complementary asset modification within the region, failed at higher scales

Involved in the participative development process of the aquaculture strategy 2012 (BMLFUW Citation2012), a farmer’s cooperative and distribution partner of many pond farmers located in Waldviertel, became aware of the opportunity to increase fish production through water-reduced, medication-independent, climate- and predator-resistant RAS (AC-REG). Engaging in regional industrial knowledge development through excursions to and cooperation with RAS path actors in Burgenland, German, Czech and Dutch regions, the cooperative had an important boundary-spanning function contributing to knowledge spillovers from resourceful extra-regional firms (AP-REG). Building on long-term established cooperation structures, the cooperative, the Federal Agency for Water Management and the chamber of agriculture in Lower Austria (an organization of the federal state) organized a conference at an agricultural training organization located in the center of Waldviertel. They invited several regional and extra-regional speakers and key firm actors of the region to initiate knowledge and skill development (AP-NAT5). Resulting from these discussions, a publicly supported training and testing plant was built by the cooperative who imported knowledge from plant operators located in the regions of Saxony (Germany) and Burgenland (Austria) and cooperated with an association of the Government of Lower Austria and a regional agricultural school (AC-REG; AP-REG; AP-NAT5; AF1-REG). The fact that this plant was built by the cooperative, representing traditional fish farmers, has been initially contested:

Established fish farmers have been very critical so that we had to prove ourselves. We knew, we showcase ourselves with the project and from that perspective, its success has been very important. (AC-REG)

In 2019, though rooted in Waldviertel, RAS is known beyond the region for its high potential to increase production in an economic and environment-friendly way (AP-REG):

Knowledge transfer happens automatically through our educational offerings, since many trainees come from the rest of Austria to complete the training here in Waldviertel. (AC-REG)

My role in preparing information and educational material is central in Austria since most other chambers of agriculture do not have the resources to employ a specialised consultant. (…) Beyond that, the capacities to engage in EU negotiations are very limited (… and) despite of first dialogues, there is no association of RAS producers yet. (AP-REG)

(w)ithout appropriate training and education about innovative solutions, university graduates working in public authorities view RAS with scepticism (…), are reluctant to engage in financial resource development, (or) oversee the need to adjust regulations. (AP-REG)

Impeding interpath relations across regions

The limited asset modification capacities at higher scales make the diversifying aquaculture path prone to impeding interpath relations across regions. Out of more than 200 graduates from the Agricultural training organization, only few firm actors establish RAS in Waldviertel or beyond due to limited financial and (EU) policy support (AE2-REG). The empirical analysis revealed that scarce financial assets and regulations from national and EU scales are used by or oriented at (1) other food paths in Austrian regions, (2) aquaculture (including RAS) paths in other EU regions and (3) traditional trout production in streams or small rivers located in other Austrian regions.

First, the attention of Austrian agricultural policy actors is oriented at other, larger and better organized paths. Although the demand for fish is rising, it is still negligible in comparison to other agricultural paths. This prepares the ground for agricultural lobbyists to pressure politicians to maintain rigid institutions and results in limited resources of national policy actors to engage at the EU level for increasing financial resources from the European Maritime and Fisheries Funds (EMFF) (AP-NAT4):

It is not only a matter of the single wish of aquaculture but Austrias agriculture has also other topics, such as alpine farming etc. In the end, it is a political issue. If Austria decides to engage in EU Agriculture Policy to support farming, then there are less resources to engage for increasing financial resources from the EMFF. (AP-REG)

Third, there was no reorientation in the implementation strategies of the EMFF at national and regional scales from established fish production methods towards RAS as needed to finance the high investment costs. Interviewees underlined the strong resistance against RAS by firms, public policy representatives and the Austrian fisheries association in favour of trout production in flow-through systems (located in Upper Austria, Styria and Carinthia). They feared competition about the limited financial assets and losing reputation of domestic production in close touch with nature (AP-NAT6; AA-NAT) – reflecting modern brandings around naturally produced food. The Austrian 2014–2020 EMFF operational programme still includes only 16% of funding for RAS activities (as compared to 45% in Slovakia) (AP-EU).

Insect-based food and feed path creation originating in Vienna

Insect protein production in Vienna, as well as in other EU regions found inspiration in a seminal report entitled Edible insects: Future Prospects for Food and Feed Security published by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) (van Huis et al. Citation2013) and its accompanying first ‘insects to feed the world conference 2014’, organized by the FAO in Wageningen, the Netherlands. Insect-based food path production and distribution in Vienna is represented by a slowly emerging, internationally embedded, university-driven path borne by few Viennese start-ups and two research institutes of the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences Vienna and the University of Veterinary Medicine in Vienna (IR-NAT2; IP-NAT4). Soon, initial network building and market creation activities by pioneering actors prompted the production of insects as human food in established and new firms located in rural areas of Vorarlberg, Burgenland, Carinthia and Upper Austria (Gugerell and Penker Citation2020; (IF-REG1; IP-NAT4)). In 2018, a group of researchers at JOANNEUM University of Applied Sciences in Graz started engaging in the integration of insect protein into the Austrian food chain (IR-NAT3). To circumvent restrictive regulations in the food sector, firm and research actors occasionally navigate between insect-based food and feed production (IF-REG2; IR-NAT3).

Regional innovation system preconditions

In the recent past, research and educational organizations combine biotechnological knowledge with competences relevant for food industries thus contributing to a changing urban-rural geography in the food sector, in which cities increasingly position themselves as new centres of innovation in the otherwise peripherally characterized sector (IP-NAT4; IR-NAT2). Vienna builds on a long tradition of food-related university-industry cooperation and recently gets involved in the production of novel foods, plant-based and alternative animal protein, aromas, enzymes, and genetically modified products (IR-NAT2; IP-NAT2). The RIS has favourable conditions to modify industrial skills within the region and access human, institutional and financial assets at higher scales. Firms and universities profit from knowledge exchange at network events and industrial working groups, they attract workers from all over the world, as well as EU funding (IF-REG2; IF-NAT1; IF-NAT2; IR-NAT1). As a downside, research-intensive, technology-driven food-related activities are disfavoured by food policies aligned with existing, rather low-tech food paths, such as alpine farming, forestry or grain farming (AP-NAT4) – a tradition that is strengthened by modern brandings favouring naturally produced foods. Limited attention of policy actors and support structures restrain complementary asset modification across scales. Insect-based food path creation with its technological innovations and foreign species has a difficult starting position also due to a centralistic and strict interpretation of regulations in the sector and a long-term established food identity associated with nature and regionality (IP-NAT4; IF-NAT1; IF-NAT2; IR-NAT1).

Failed complementary asset modification across scales

The international debate about insects as a sustainable protein source initiated by the widely received FAO report (van Huis et al. Citation2013) motivated the EU to adopt the novel food regulation in 2015. With its implementation in 2018, the decision of which species and form of insects may be sold as edible has been rescaled from the member states to the EU. Viennese firm actors and their cooperation partners have put great hope in using new institutional assets created at higher scales, however, the translation of institutional assets to lower scales has led to rigid interpretation and shows only low innovative ambition (IF-REG1; IF-REG2; IR-NAT3). The ‘National Guideline for Cultivated Insects as Food’ (BMGF Citation2017) restricted the sale for human food to whole insects despite of claims to allow their processing by involved scientific partners and firm actors in the working group (IP-NAT2; IF-REG1; IF-REG2; IP-NAT3). Arguing for consumer protection, this restrained further complementary development of region-specific industrial knowledge and skills in the form of product development like pasta, flour or meat substitutes (IF-REG1; IF-REG2; IP-NAT1).Footnote2

The working group insects as food (coordinated by the Federal Ministry of Labour, Social Affairs, Health and Consumer Protection) has not changed the direction (…), because until we do not know the needed criteria for food safety, such foods should not come onto the market. (IP-NAT3)

The European Union supports much research and innovation. Only later, actors understand that in terms of legal conditions, the new activities are not well aligned to the existing (national) regulative framework (…) guided by the very old, strict and rigid Austrian Food Code. (IP-NAT4)

The economic chamber and other advocacy groups bat the ball of legal processing effort back and forth. (…) Firm actors miss legal and technical advice and assistance in providing scientific evidence for risk assessment or demonstrating the safe use of new products. (IP-NAT4)

Reinforcing interpath relations across regions

Path agents follow two strategies to benefit from reinforcing interpath relations. First, since complementary modification of institutional assets at the national scale failed in the first instance, Viennese firm actors adopt a passive attitude waiting for the creation of further novel food approvals at the EU level, e.g. extracted insect protein or fat by non-Austrian or supra-national actors (IP-EU):

Austrian actors wait for applications made by large breeding establishments or the IPIFF (International Platform of Insects for Food and Feed) at the EU level, since it is also a question of financial and other expenses. (IP-NAT3)

Insects as livestock feed are currently allowed for fish but soon regulations will be adapted for chicken and then pigs. The more markets can be served, the more actors will enter the field. (IF-REG2)

We want to place a whole range of products and tell a story of how insect-based food and feed is able to solve sustainability problems along the food supply chain – from using old bread to feeding insects producing fish, human food, dog snacks, and fertilizer, among others. (IF-REG2)

Discussion and conclusion

Regional restructuring to meet societal challenges involves the development of several, possibly interacting regional industrial paths. In this article, I build on EEG conceptualizations of interpath relations ‘within’ regions and combine them with recent insights from EEG and innovation system studies on the multi-scalar availability and modification of assets to conceptualize interpath relations ‘across’ regions and countries. Conceptualizing interpath relations as resulting from the same asset needs, their modification decides upon whether interpath relations have reinforcing or impeding effects on involved paths. This is because the modification of assets at multiple scales is distributed among different actor groups working for different industrial paths evolving in different regions and its outcome specifies for which paths assets are accessible, usable, can be best interpreted, or at which paths they are oriented at.

The article contributes a reflection on the dynamic mechanisms of acceleration and (re-)orientation of path development as a reaction to reinforcing or impeding asset modification by other paths. When reinforcing interpath relations increases the attention of path actors, the inter-connectedness of functionally related asset stocks (Maskell and Malmberg, Citation1999a) impels them to (re-)interpret, (re-)orient and (re-)use the remaining asset base by complementary asset modification. Impeding interpath relations instead stimulate paths to reorient towards other assets and possibly also towards other, more reinforcing interpath relations. Considering the need to modify institutions in the early phase of path development (Rypestøl et al. Citation2021), the insect-based food case proofs the significance of interpath relations in processes of path (re-)orientation when actors navigate between insect-based food and feed production, the latter benefiting from relations with the RAS path.

To build the conceptual framework, I employ the RIS approach to analyze how regional preconditions tend to affect the outcome of asset modification at national and international scales. Comparing the RIS of a peripheral with a core region stimulating two intertwined cases of early path development in the food sector, I contribute empirical material of a rather under-researched topic in EEG (recent exceptions are Martin and Martin Citation2021; Baumgartinger-Seiringer et al. Citation2022). The results emphasize that regional preconditions play a meaningful role in complex multi-scalar governance mechanisms. In return, regions rely on national support to enable complementarity in the multi-scalar asset stock for path development. This leads to the question of how the multi-scalarity of asset availability and modification needed for path development can be reflected in regional and national innovation policies. The aquaculture case has demonstrated that limited competencies in the peripheral region to modify national education schemes and EU financing has contributed to the non-achievement of the objectives in the national aquaculture strategy. The insect-based food and feed case in Vienna revealed a lack of focus by policy and supporting organizations that limited the attention for complementary modification of the national and international regulative framework. In order to capture a competitive advantage for new path development in light of interpath relations across regions, the need to support (complementary) asset modification across scales deserves more attention (i) in urban regions to support the acceleration of path development but also in (ii) peripheral regions to enhance their capacities to modify assets at higher scales and thus their engagement in interpath relations across regions. To begin with, policy should more explicitly consider the tendency of different types of assets to exist at multiple scales. To not only support path agents to make use of externally created assets but also to take care of multi-scalar policy strategy alignment, interventions should take a more integrated approach acknowledging the inter-connectedness of different types of assets across scales.

The empirical analysis showed that the reorientation of both paths towards each other helps complementing missing pieces of the asset stock. On the one hand, regulative barriers can be circumvented by producing animal feed instead of human food until needed institutional asset modification at the EU scale is completed by insect-based food paths evolving in other EU regions. On the other hand, the increasingly scarce, expensive and unsustainable oceanic fishmeal can be replaced with insect-based feed for aquacultures to close the loop in regional fish production. This demonstrates that besides regional preconditions to support path development, relations between several industrial paths evolving in different regions should not be overlooked by structural change policies. To support paths in benefitting from reinforcing interpath relations, policy actors should strategically balance and coordinate the timing of letting path agents wait for further asset modification by other paths (e.g. of the regulative framework, insect-based food) and supporting them to reorient to other reinforcing interpath relations by initiating the debate and providing networking events and support structures (e.g. synergetic development of industrial skills, insect-based feed and aquaculture). To avoid impeding interpath relations, policy actors should question whether path development is in line with their strategic policy orientation to then possibly engage in the creation or reorientation of needed assets (e.g. financial support for RAS to meet the objectives of the national aquaculture strategy).

Food sector innovations do not only increasingly restructure the food production system to cope with urgent societal challenges. Moreover, due to the changing urban-rural geography accentuating the role of cities as new centres of innovation in the peripherally characterized sector, there is scope for policy intervention. Synergetic relationships between the urban insect-based food and feed path and the diversifying rural aquaculture path triggered the establishment of new firms, cooperation projects with NGOs and policy actors in core as well as peripheral regions. These insights point to policy interventions that specifically aim to strengthen core–periphery linkages and bridging ties between scales and paths. Examples could be to open university curricula and research programmes for topics specifically relevant in peripheral regions, to establish dedicated organizations, platforms and living labs and provide determined networking events and conferences.

The focus on two most similar case studies allowed a confirmation as well as empirical complementation of the conceptual framework (Seawright and Gerring Citation2008), reflecting on idealistic capacities of core and peripheral RIS to modify assets at national and international scales. Nevertheless, this is also a limitation of the analysis that points to the importance of future cross-country comparative studies within the food sector and beyond to prove and extend conceptualizations of how interpath relations are shaped by place-specific preconditions, also taking into account other types of regions and industries. Moreover, the article points to the need for complementary asset modification due to the inter-connectedness of asset stocks. How different (types of) assets across scales are related to each other has, however, not been captured by this article and would warrant further examination.

The role of RIS to influence the routes of path development has recently been further investigated (Trippl et al. Citation2021). In this article, I accentuate opportunities as well as barriers evolving from interpath relations across regions. This reflects that also the preconditions of other regions may have unintended spillovers on regional industrial path development. I therefore argue that RIS studies should be more open to the influence of RIS beyond the considered region including also questions of rationality or directionality of innovation-based change (Tödtling, Trippl, and Desch Citation2021). In this way, combined effects of multiple paths (Chlebna, Martin, and Mattes Citation2021) on cross-regional sustainable development could be addressed, which is specifically desirable in the context of rising societal challenges.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Marianne Penker, Camilla Chlebna and one anonymous reviewer for helpful comments on earlier versions of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Sustainable Development Goals, Food 2030, EU Green Deal, EU Farm to Fork Strategy, EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030, IPES Food, Milan Urban Food Policy Pact

2 The national guideline for cultivated insects as food is regularly updated and due to institutional asset modification activities by firm and research actors, regulative changes are expected.

References

- Andersen, A. 2012. “Towards a New Approach to Natural Resources and Development: The Role of Learning, Innovation and Linkage Dynamics.” IJTLID 5: 291–324. doi:10.1504/IJTLID.2012.047681

- Asheim, B., A. Isaksen, and M. Trippl. 2020. “The Role of the Regional Innovation System Approach in Contemporary Regional Policy: Is It Still Relevant in a Globalised World?” In Regions and Innovation Policies in Europe, edited by M. González López and B. T. Asheim, 12–29. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Baumgartinger-Seiringer, S., D. Doloreux, R. Shearmur, and M. Trippl. 2022. “When History Does not Matter? The Rise of Quebec’s Wine Industry.” Geoforum 128: 115–124. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.12.013

- Bergek, A., M. Hekkert, S. Jacobsson, J. Markard, B. Sandén, and B. Truffer. 2015. “Technological Innovation Systems in Contexts: Conceptualizing Contextual Structures and Interaction Dynamics.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 16: 51–64. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2015.07.003

- Binz, C., and B. Truffer. 2017. “Global Innovation Systems – A Conceptual Framework for Innovation Dynamics in Transnational Contexts.” Research Policy 46: 1284–1298. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2017.05.012

- Binz, C., B. Truffer, and L. Coenen. 2016. “Path Creation as a Process of Resource Alignment and Anchoring: Industry Formation for On-Site Water Recycling in Beijing.” Economic Geography 92: 172–200. doi:10.1080/00130095.2015.1103177

- BMGF. 2017. Guidance for Cultivated Insects as Food. Vienna: Federal Ministry for Women and Health.

- BMLFUW. 2012. Aquakultur 2020 – Österreichische Strategie zur Förderung der Nationalen Fischproduktion. Vienna: Federal Ministry for Agriculture and Environment.

- Boschma, R. 2017. “Relatedness as Driver of Regional Diversification: A Research Agenda.” Regional Studies 51: 351–364. doi:10.1080/00343404.2016.1254767

- Boschma, R., L. Coenen, K. Frenken, and B. Truffer. 2017. “Towards a Theory of Regional Diversification: Combining Insights from Evolutionary Economic Geography and Transition Studies.” Regional Studies 51: 31–45. doi:10.1080/00343404.2016.1258460

- Breul, M., C. Hulke, and L. Kalvelage. 2021. “Path Formation and Reformation: Studying the Variegated Consequences of Path Creation for Regional Development.” Economic Geography 97: 213–234. doi:10.1080/00130095.2021.1922277

- Chlebna, C., H. Martin, and J. Mattes. 2021. “Grasping Transformative Regional Development from a Co-evolutionary perspective – A Research Agenda,” GEIST Working Paper Series, 1–31.

- Engelhardt, H., M. Brüdern, and L. Deppe. 2020. Nischeninnovationen in Europa zur Transformation des Ernährungssystems. Dessau-Roßlau: Umweltbundesamt.

- Frangenheim, A., M. Trippl, and C. Chlebna. 2020. “Beyond the Single Path View: Interpath Dynamics in Regional Contexts.” Economic Geography 96: 31–51. doi:10.1080/00130095.2019.1685378

- Frenken, K., F. van Oort, and T. Verburg. 2007. “Related Variety, Unrelated Variety and Regional Economic Growth.” Regional Studies 41: 685–697. doi:10.1080/00343400601120296

- Fuenfschilling, L., and C. Binz. 2018. “Global Socio-Technical Regimes.” Research Policy 47: 735–749. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2018.02.003

- Garud, R., and P. Karnøe. 2003. “Bricolage Versus Breakthrough: Distributed and Embedded Agency in Technology Entrepreneurship.” Research Policy, 277–300. doi:10.1016/S0048-7333(02)00100-2

- Grillitsch, M., and M. Sotarauta. 2020. “Trinity of Change Agency, Regional Development Paths and Opportunity Spaces.” Progress in Human Geography 44: 704–723. doi:10.1177/0309132519853870

- Gugerell, C., and M. Penker. 2020. “Change Agents’ Perspectives on Spatial–Relational Proximities and Urban Food Niches.” Sustainability 12: 1–18. doi:10.3390/su12062333

- House, J. 2018. “Insects as Food in the Netherlands: Production Networks and the Geographies of Edibility.” Geoforum 94: 82–93. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.05.011

- Isaksen, A. 2015. “Industrial Development in Thin Regions: Trapped in Path Extension?” Journal of Economic Geography 15: 585–600. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbu026

- Isaksen, A., S.-E. Jakobsen, R. Njøs, and R. Normann. 2019. “Regional Industrial Restructuring Resulting from Individual and System Agency.” Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research 32: 48–65. doi:10.1080/13511610.2018.1496322

- Isaksen, A., E. Langemyr Eriksen, and J. Rypestøl. 2020. “Regional Industrial Restructuring: Asset Modification and Alignment for Digitalization.” Growth and Change 51: 1454–1470. doi:10.1111/grow.12444

- Isaksen, A., and M. Trippl. 2016. “Path Development in Different Regional Innovation Systems: A Conceptual Analysis.” In Innovation Drivers and Regional Innovation Strategies, edited by M. D. Parrilli, R. Dahl-Fitjar, and A. Rodriguez-Pose, 66–84. New York and London: Routledge.

- Jolly, S., M. Grillitsch, and T. Hansen. 2020. “Agency and Actors in Regional Industrial Path Development. A Framework and Longitudinal Analysis.” Geoforum 111: 176–188. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.02.013

- MacKinnon, D., S. Dawley, A. Pike, and A. Cumbers. 2019. “Rethinking Path Creation: A Geographical Political Economy Approach.” Economic Geography 95: 113–135. doi:10.1080/00130095.2018.1498294

- Martin, R. 2010. “Roepke Lecture in Economic Geography – Rethinking Regional Path Dependence: Beyond Lock-in to Evolution.” Economic Geography 86: 1–27. doi:10.1111/j.1944-8287.2009.01056.x

- Martin, H., and R. Martin. 2021. “The Role of Demand for Regional Development – Green Transformations in the Food Industries in Scania and Värmland,” CRA Working Paper, 1–19.

- Maskell, P., and A. Malmberg. 1999a. “Localised Learning and Industrial Competitiveness.” Cambridge Journal of Economics, 167–185. doi:10.1093/cje/23.2.167

- Maskell, P., and A. Malmberg. 1999b. “The Competitiveness of Firms and Regions. ‘Ubiquitification’ and the Importance of Localized Learning.” European Urban and Regional Studies 6: 9–25. doi:10.1177/096977649900600102

- Pesch, U. 2015. “Tracing Discursive Space: Agency and Change in Sustainability Transitions.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 90: 379–388. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2014.05.009

- Pflitsch, G., and V. Radinger-Peer. 2018. “Developing Boundary-Spanning Capacity for Regional Sustainability Transitions – A Comparative Case Study of the Universities of Augsburg (Germany) and Linz (Austria).” Sustainability 10. doi:10.3390/su10040918

- Rypestøl, J., A. Isaksen, E. Eriksen, T. Iakovleva, S. Sjøtun, and R. Njøs. 2021. “Cluster Development and Regional Industrial Restructuring: Agency and Asset Modification.” European Planning Studies 29: 2320–2339. doi:10.1080/09654313.2021.1937951

- Sandén, B., and K. Hillman. 2011. “A Framework for Analysis of Multi-Mode Interaction among Technologies with Examples from the History of Alternative Transport Fuels in Sweden.” Research Policy 40: 403–414. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2010.12.005

- Seawright, J., and J. Gerring. 2008. “Case Selection Techniques in Case Study Research.” Political Research Quarterly 61: 294–308. doi:10.1177/1065912907313077

- Steen, M., and G. Hansen. 2018. “Barriers to Path Creation: The Case of Offshore Wind Power in Norway.” Economic Geography 94: 188–210. doi:10.1080/00130095.2017.1416953

- Stern, N. 2007. The Economics of Climate Change: The Stern Review. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 692.

- Tödtling, F., M. Trippl, and V. Desch. 2021. “New Directions for RIS Studies and Policies in the Face of Grand Societal Challenges.” GEIST Working Paper Series, 1–20.

- Trippl, M., S. Baumgartinger-Seiringer, A. Frangenheim, A. Isaksen, and J. Rypestøl. 2020. “Unravelling Green Regional Industrial Path Development: Regional Preconditions, Asset Modification and Agency.” Geoforum 111: 189–197. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.02.016

- Trippl, M., S. Baumgartinger-Seiringer, E. Goracinova, and D. Wolfe. 2021. “Automotive Regions in Transition: Preparing for Connected and Automated Vehicles.” Environment & Planning A 53: 1158–1179. doi:10.1177/0308518X20987233

- Trippl, M., M. Grillitsch, and A. Isaksen. 2018. “Exogenous Sources of Regional Industrial Change: Attraction and Absorption of Non-Local Knowledge for New Path Development.” Progress in Human Geography 42: 687–705. doi:10.1177/0309132517700982

- van Huis, A., J. van Itterbeeck, E. Mertens, A. Halloran, G. Muir, and P. Vantomme. 2013. “Edible Insects: Future Prospects for Food and Feed Security.” FAO Forestry Paper 171, Rome.

- Wepner, B., S. Giesecke, M. Kienegger, D. Schartinger, and P. Wagner. 2018. Fit4Food2030 – Report on Baseline and Description of Identified Trends, Drivers and Barriers of EU Food System and R&I.

- Yin, R. 2009. Case Study Research Design and Methods. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications.