ABSTRACT

Ongoing sustainability challenges create pressure on planning practices and institutional arrangements. Transformative policy visions, such as the circular economy and bioeconomy, create promises for designing and planning sustainable pathways in society. Moreover, research agendas on sustainability transitions, such as transition management, are developing toolkits and attempting to shift planning practice by applying evidence-based policy-making processes. In this paper, we ask what happens when sustainability visions are exposed to planning practices, and vice versa, by developing an analytical framework to discuss processes of territorialization and mobilization. We draw lessons from two contextually differing case studies in Finland; on the evaluation of spatial planning processes for the circular economy and a strategic planning intervention for the blue bioeconomy. The disparate cases show that the planning process act as a bidirectional intermediary space, refining both the general transition visions and established planning practices.

1. Introduction

The European Union’s (EU) Green Deal envisages restructuring of industrial sectors towards a more circular economy, promotes the role of blue resources in alleviating pressures on land and addresses the negative environmental impacts of production and consumption (European Commission Citation2019a). The strategy highlights the importance of sectorial connections and builds the basis for steering policies and resources towards ‘sustainability transformations’. In this sense, the Green Deal is a performative example standing out in a ‘sea of expectations’ (cf. van Lente Citation2012), as a vision of a more sustainable society to be created and made workable in a complex trans-scalar and trans-sectoral governance setting. It also brings together visions that have been articulated in different policy domains such as the circular economy and the blue economy, which build on the potential to deliver much needed ‘sustainable and inclusive growth’ (European Commission Citation2019a, 2). These visions are generative, as they build specific connections in society that simultaneously create a direction for transformation and stabilize existing economic and technological structures (cf. Borup et al. Citation2006; Jasanoff Citation2004). Moreover, especially in the EU context, the policy programmes are designed as general, mutable and flexible to become mobile and workable across different contexts of implementation and planning (Peck and Theodore Citation2015). The emerging sustainability visions have, therefore, become the general substance of planning activities across institutions leading to diverse experimental and co-productive planning assemblages that employ radically different kinds of spatial, temporal and procedural approaches (Fuenfschilling, Frantzeskaki, and Coenen Citation2019; Parks Citation2019).

In the context of societal expectations, sustainability transitions have emerged as a research field that provides methodological and conceptual approaches to facilitate the development of innovation pathways and governance frameworks for systemic change towards a more sustainable society (e.g. Köhler et al. Citation2019). According to the field’s basic assumptions, transitions take place by introducing and diffusing novel technologies and practices to break the status-quo, which shifts the focus towards policy implementation of larger scale transformations (Kivimaa et al. Citation2019; Rotmans, Kemp, and van Asselt Citation2001). These transitions, however, neither emerge in a vacuum nor do they follow any predetermined scripts. Rather, they require contextual work to address spatially divergent conditions, adverse societal, economic and environmental effects and complex power relations (Frantzeskaki et al. Citation2017). As sustainability visions are translated into planning practice, their content becomes ‘tested’, which affects their substance and societal scope. Here, planning is one key area for the interpretation and contextualization of visions, via their translation into diverse and spatially embedded planning processes, practices and stakeholder networks.

While the concepts and methodologies of sustainability transitions are well established, few studies investigate the impact of transformative visions on the work of urban and spatial planners, or their legitimation within planning institutions (Wolfram Citation2018). Transformative epistemologies emphasize normative goals, immediate action and experimentation as primary theories of change (Loorbach, Frantzeskaki, and Huffenreuter Citation2015; Voß, Smith, and Grin Citation2009), which are not readily compatible with the procedural requirements central to planning epistemologies (Albrechts Citation2004). Transformative policy agendas can enable the disruption of institutionalized practices, thus creating temporal and spatial openings, where existing societal relations and roles are opened for negotiations, and experimentation with novel practices is suggested to boost change ‘on the ground’ (Avelino and Grin Citation2017; Frantzeskaki et al. Citation2017). However, the policy influence and long-term impacts of transformative interventions remain an open question (Albrechts, Barbanente, and Monno Citation2020).

In recent years, the sustainability transitions literature has made progress in providing a conceptual dialogue with planning theories (Wolfram Citation2018). However, as Wolfram (Citation2018) notes, the epistemologies are not fully compatible, creating challenges that may surface only in empirical considerations that gain form in sectoral and spatial dynamics. In the circular economy context, several authors have called for the need to move beyond generalizations, to investigate spatial contexts in different sectors – especially in urban planning – and argued that a lack of focus in implementation can lead to the de-legitimization of such policy visions (Bolger and Doyon Citation2019; Campbell-Johnston et al. Citation2019; Prendeville, Cherim, and Bocken Citation2018). In the literature on blue growth, the blue economy and the blue bioeconomy, spatial planning is discussed in terms of establishing sustainability preconditions for economic activities, but little attention has been paid to the enabling role of planning processes in coordinating and connecting activities across sectors and spatial scales (Eikeset et al. Citation2018; Winder and Le Heron Citation2017).

In this paper, we analyse what happens to transformative visions when they meet planning practices. We develop a framework to reflect the transition dynamics from different planning angles, which is strengthened and operationalized by analysing cases on the circular economy and blue bioeconomy in spatial planning in Finland. The circular economy refers to a ‘set of practices that aim at the minimisation, in view of total elimination, of resource extraction and waste generation’ (Brandão, Lazarevic, and Finnveden Citation2020). As a transformative policy vision, it has been adopted by national and trans-national policy actors and intermediaries as a systemic response, and alternative, to modern, linear production and consumption systems (Brandão, Lazarevic, and Finnveden Citation2020). The blue bioeconomy, meanwhile, refers to governance reforms and blue technology developments that enhance the potential of aquatic environments in providing ecologically sustainable resources for diverse societal needs (Ligtvoet et al. Citation2019). As a transformative policy vision, the policy actors on different levels refer to it as means of mobilizing diverse ecosystem services of fluvial environments that displace old extractivist economic practices by supporting regulatory reforms and novel technological advances (Ligtvoet et al. Citation2019). Finland has been actively developing strategic policy goals and networks in both areas, while also establishing the salience of these areas on the EU policy agenda. Currently, the policy visions are being implemented in different contexts, which merits an empirical focus on planning. These contrasting cases provide critical perspectives on how the transformative visions become institutionalized in different practices of planning, e.g. in strategic and statutory spatial planning. In this paper, we develop a framework to reflect transition dynamics from these diverse planning angles. Through the two case studies, we aim to answer the following research questions:

How are transformative policy visions and agendas translated into spatial planning practices?

What kinds of planning dynamics are central in the institutionalization of sustainability transition agendas?

The paper is structured in four sections: first conceptualizing relation between planning and sustainability transitions literature, moving to the case context and methodological considerations, providing analysis of the two cases, and finally discussing the pragmatic and conceptual lessons.

2. Transitions in planning

2.1. From strategic to transformative planning?

The concept of ‘transformative planning’ has been periodically brought up in the planning literature, responding to different societal challenges and requirements connected to the governing role and impacts of planning processes. Conceptually, it can be approached from three interconnected angles. From a ‘procedural perspective’, there have been calls to utilize transformative planning approaches to develop and generalize novel planning instruments to bridge the ontological divide between vision-based utopian planning practice and procedurally grounded realistic planning practice (Marcuse Citation2017). From a ‘practice perspective’, the role of transformative planning has been framed as a disruptive moment to de-align sectorial institutional arrangements and create space for normative and performance-based arrangements (Steele Citation2011). From an ‘agenda perspective’, calls have been made to explicitly engage with issues of urban social justice (Song Citation2015) and sustainability transitions (Wolfram Citation2018) to steer societal developments. The orientations share the prerequisite for a more adaptable and normatively engaged planning regime, and transformative planning has resurfaced due to the recent amplification of environmental and social sustainability issues. Moreover, the term ‘transformation’ has enough interpretive flexibility to accommodate several meanings and contextual translations and, thus, acts as a mediating concept.

The motivation for these transformative calls is grounded in the shortcomings of planning practice that are both epistemological and ontological. According to Albrechts (Citation2015), the dominant planning epistemologies favour an entrepreneurial view on immediate concerns that leaves little space for imaginative perspectives on longer term implications. The ontologies are grounded in the Euclidean singular view on space, which systematically overlooks the potential of alternative development trajectories and narrows down the sphere of possibilities (Albrechts Citation2015). Strategic spatial planning has been endorsed as an alternative to address these limitations by forming a more inclusive and accountable space for value-based visioning, as well as serving a trans-scalar role in mediating societal developments between, for example, municipal and state-level decision-making (Albrechts Citation2004). Building on new institutionalism, the strategic planning approach covers more integrated orientations in planning by building strategic and normatively grounded agendas and methodologies with stronger participation of societal stakeholders (Hiller and Healey Citation2008; Newman Citation2008). Moreover, Healey (Citation2006) has interpreted the transformative role of strategic planning through its capacity to frame attention on societal issues by mobilizing the governance of imagination that travels between different institutional contexts and carries sufficient authoritative force to maintain its shape over a considerable time span.

The strategic turn in planning practice has provided space for the emergence of a co-productive orientation, which has provoked discussions on the methodological capacities of planning. First, co-production aims to reach beyond the traditional narrowing of interactions in terms of procedural ‘citizen participation’ by facilitating emancipation and politics, where constructive capacities of diverse stakeholders are framed as central (Albrechts Citation2012). Co-production can be interpreted in terms of ‘civic governmentality’ by generating technologies of governing and self-rule that influence societal arrangements (Roy Citation2009). Second, co-production has expanded the planning community for non-human stakeholders (e.g. explicating active processes of nature, constructive power of physical surroundings, role of measuring techniques, etc.) that constantly shape the conduct of planning. Third, the positions and interests of stakeholders do not solely pre-exist the participatory planning designs, but are also products of collective co-productive processes, where issues are generated as relational products of ‘ontological choreography’ (Metzger Citation2013a).

Recently, the conceptualization of urban transformative capacities and the co-creation of future visions has built on the advancements in strategic planning literature (Bos, Brown, and Farrelly Citation2015; von Wirth et al. Citation2019; Wolfram, Frantzeskaki, and Maschmeyer Citation2016). The focus is geared by the recognition of cities’ untapped potential in generating transformative capacities to act as test beds for novel technologies and societal practices and build trans-scalar connections, where radically new lessons and designs can be transported across the globe (Wolfram Citation2016). Comparing planning experiences between different contexts is often used as a way of generating systemic transition lessons on planning practice (Frantzeskaki et al. Citation2017). Especially, transition management is framed as a promising experimental governance approach that provides planning processes and experts with an informal forum, a transition arena, to involve societal stakeholders in developing and legitimizing, as well as challenging and testing, transformative policies in terms of more specified and pragmatic considerations (Loorbach, Frantzeskaki, and Huffenreuter Citation2015). Transition management has the potential to complement institutionalized planning practices by opening them up to a variety of societal perspectives, although it also has several limitations that require pragmatic consideration (see Loorbach, Frantzeskaki, and Huffenreuter Citation2015; Wolfram Citation2018).

2.2. Analytical framework

Sustainability transitions call for a focus on pragmatic and procedural considerations at the different forms and stages of spatial planning processes. Planning processes can be distinguished as (i) statutory planning, emphasizing the spatial features of planning in terms of zoning processes, and (ii) strategic planning, focusing on the temporal and relational reach of planning outcomes (Mäntysalo Citation2013). Strategic planning is not suggested to be a substitute for statutory land-use and sectoral planning but, instead, a necessary complement at times, where the strategic choices can be made beyond ‘incremental policies’ (Albrechts and Balducci Citation2013). Thus, strategic planning orientations are more concerned with societal agenda setting, while statutory planning orientations emphasize procedural and formalized aspects, resembling Andreas Faludi’s distinction between ‘theory of planning and theory in planning’ (Wolfram Citation2018). The former discusses the rationality of planning as a societal action and its role in temporal development, while the latter focuses pragmatically on the instruments and techniques used in planning practice (Faludi Citation1973). Distinction between the two planning ontologies and orientations with respect to social governance has been coded deeply in planning thought, where planning as a visionary exercise for societal change and as a technocratic practice to maintain societal stability have reproduced an antagonistic relation (Davoudi Citation2001; Wolfram Citation2018). However, both visionary future building and professional specialism are relevant for the transformative perspective, especially when we consider the embedding of sustainability visions into planning practice.

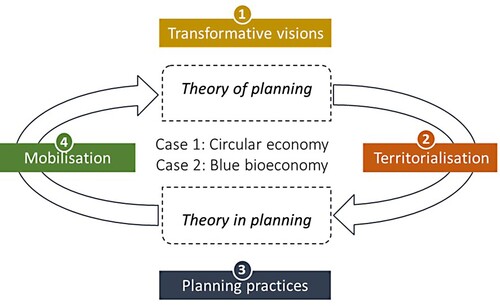

Our analytical framework builds on this planning dialectic by discussing the circular economy and blue bioeconomy transformative visions, their territorialization in planning processes, the role of planning practices in readjusting transition policies and the realignment of visions in terms of what elements become workable ().

‘Transformative visions’ are connected to the ‘theory of planning’ perspective by identifying how the future visions of sustainability influence the position of planning in society. The concepts of guiding visions and socio-technical expectations are commonly used when analysing the role of the future and collective imagination in socio-technical change. Guiding visions have been described as ‘collectively held and communicable schemata that represent future objectives and express the means by which these objectives will be realized’ (Berkhout Citation2006, 302). The term expectations have often been used ‘to refer to the less formalised, often fragmented and partial, beliefs about the future’ (Eames et al. Citation2006, 362). Although visions are more than expectations, enrolling specific constellations of modes of coordination and technologies in their representation of the future, the two have several common features (Bakker and Budde Citation2012; Bakker, Van Lente, and Meeus Citation2011; Borup et al. Citation2006; van Lente Citation2012). First, they establish common reference points to coordinate the action of different actor communities. In this sense, they provide heuristic guidance to direct search processes and reduce uncertainty. Second, they are performative, as they mobilize promising futures into the present, legitimize investments, define actor roles and create mandates to build mutually binding obligations. Third, they exhibit a degree of interpretive flexibility, which, on the one hand, can widen its relevance, but on the other hand, too much flexibility can cause visions to become unstable and lack credibility.

‘Territorialization’ refers to the dynamics of translating visions into action through contextual planning processes, where policy visions become attached to particular places by establishing a territorial logic (Gomart and Hajer Citation2003; Metzger Citation2013a). Planning carries the ontological property of stabilizing and transporting issues beyond a bounded context and making them actionable (Callon and Law Citation2005), and the territorial politics of sustainability visions create wider publics around the issues (Marres Citation2007). This process includes demarcating the boundaries of societal interaction and enrolling actors into future-oriented dialogue, leading to the emergence of novel connections, interpretations and values. Engaging actors in co-production for planning is a future-oriented act, where the ‘stakeholderness’ of different parties becomes constituted through the relational work of identifying workable issues and creating novel connections (Metzger Citation2013a). The creation of territorial interest and actor-networks around issues is an outcome of a planning process, which specifies and alters the original transformative visions. However, the stakeholders are often predefined in the planning contexts, which limits space for new connections and emergence of wider issue-based publics (Baker, Hincks, and Sherriff Citation2010).

Illustrating ‘theory in planning’ perspective, ‘planning practices’ refer to planning instruments, procedural designs and the roles of the planner. The necessary perspective here is to view planning as a ‘practical skill’ (Mäntysalo Citation2013) relying on specific instruments, techniques, procedures and methodologies to provide legitimation and justification for the outcomes. The instruments range from regulatory and legally binding specifications to economic assessments, information guidelines and voluntary commitments, while specific techniques include development of timeframes, periodic elaborations, creativity techniques as well as modelling, foresight and simulation methods (Wolfram Citation2018).

Finally, ‘mobilization’ is considered as feedback from the planning practice to the policy visions by generalizing knowledge on contextual impacts and material constraints. Planning creates a moment of collective action, but there are always elements that reach beyond the context and scope of planning (Newman Citation2008). The planning work, thus, demarcates abstract visions in the terms of relatable, identifiable and workable content. As noted, planning also brings also procedural and regulative requirements that narrow down the content of the visions working as a pragmatic test for the workability of visions. Planning processes may also serve an ‘agonising’ role by opening critical discussions and the potential augmentation of transformative visions – positioning planning well beyond neutral policy mediation (Hillier Citation2003).

3. Methodology: empirical contexts and research data

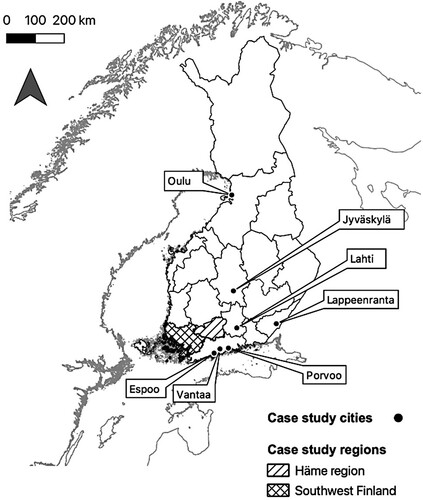

The four transformative elements in planning, generalized above, provide interpretative scrutiny on empirical contexts of planning. The empirical section builds on two case studies on institutionalizing sustainability transition concepts and methods in the planning practice in Finland, focusing on science-policy dialogues related to circular economy and blue bioeconomy planning (). The two cases are not strictly comparative, but rather serve to illustrate the robustness of the analytical framework and its operationalization in different contexts (see Flyvbjerg Citation2006). Finland has been one of the policy forerunners in both areas. The national circular economy roadmap was published in 2016 (Sitra Citation2016), and Finland was heavily influencing the development of the EU circular economy action plan in 2019. Also, in 2016, the Finnish development plan for a blue bioeconomy until 2025 and accompanying innovation agenda were published (Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry Citation2016; Ministry of agriculture and Forestry Citation2018), and blue growth policies have gained a strong foothold in EU policies over the last decade (e.g. European Commission Citation2012, Citation2020). The cases share characteristics in institutional contexts and temporal execution, but they differ in substance area, data collection and planning dynamics examined ().

Table 1. Case overview.

Case 1 builds on an evaluation project of the circular economy in municipal and regional land-use planning (Vierikko et al. Citation2020). The objective was to analyse the implications of the circular economy for spatial planning, its application, and the challenges and opportunities, it presents. Primary data from 9 expert interviews with 20 interviewees were collected in 7 cities and 2 regional councils, from March to May 2020. The cities and regions were selected based on geographical (from different parts of Finland), thematical (variety of ‘circular planning solutions’) and planning coverage (different spatial planning levels covered). The municipal and regional planning cases are pioneering areas that have actively developed experiments and policies for the circular economy in land-use planning. Case 2 focuses on a transition arena intervention on the blue bioeconomy carried out in the Southwest Finland region in 2019 (Valve et al. Citation2019). The arena was hosted by the regional council and aimed at understanding and managing regional preconditions for the development of a sustainable blue bioeconomy. By constructing future pathways and formulating policy actions, the transition arena constituted an informal planning process for stakeholders from different societal areas (business, academia, civil society, knowledge intermediation and administration) to elaborate novel modes of governance for blue resources and provide regional planners with strategic tools to better cope with sustainability challenges (Hyysalo et al. Citation2019). Primary data consisted of 10 ex-post interviews conducted 6–7 months after the process. Coastal location, long history and identity building in the Finnish Archipelago Sea, and aquatic business development and knowledge production in the regional capital Turku make the area interesting for blue bioeconomy planning. The two cases were analysed iteratively focusing on four key aspects in the coding process: definitions of transformative policies, territorial interpretations, implications for planning practice and feedbacks on policy mobilization.

4. Transitions and planning: two Finnish experiences

4.1. Circular economy in planning

4.1.1. Transformative visions

The circular economy has become one of the key governance frameworks for policymakers, businesses and academia who are looking to reconfigure how value is extracted from resources (Hobson Citation2021). It has emerged from the long-held concern for the need to situate economic growth within the earth’s carrying capacity (e.g. Boulding Citation1966; Georgescu-Roegen Citation1971) and is commonly operationalized through ‘re’strategies that seek to transform resource flows into loops, for example, reuse, repair, recycling and remanufacturing (see Reike, Vermeulen, and Witjes Citation2018). The circular economy has become a performative ideal that now guides EU policy-making: an ‘irreversible, global mega trend’ according to the European Commission (European Commission Citation2019b, 10). The vision presented in EU policy documents is one of a future without waste; although waste is produced, it is not considered an externality of socio-economic metabolism but fed back into production as an input (Kovacic, Strand, and Völker Citation2020).

Expectations for the EU’s circular economy have been categorized into four distinct areas (see Lazarevic and Valve Citation2017), which are also be found in Finland’s circular economy roadmap (Sitra Citation2016). First, ‘a perfect circle of slow material flows’ is supported by actions such as nutrient recycling, industrial symbiosis, the valorization of mining and construction waste, which slows the flow of materials within the economy. Second, the ‘shift from consumer to user’ differentiates actions for consumers (of biological materials) and users (of technical materials, i.e. inorganic material), specifically highlighted in the development of user-oriented mobility services. Third, ‘growth through circularity and decoupling’ is given as the primary motivation for the country’s circular economy work, with the circular economy driving investment and export growth. Fourth, as a ‘solution to renewal, security and competitiveness’ the circular economy provides a competitive advantage that ‘supports competitiveness – a reduction in import dependency and new export advantages’ (Sitra Citation2016, 47).

Whilst the national circular economy roadmap highlights the need for regulatory change, the role of spatial planning has only recently become acknowledged at the national level. The circular economy is raised as one of the targets in the ongoing reform of the Land Use and Building Act. The legislative framework mediates how the sustainability visions become interpreted as rules in the planning realm. To support this shift, other governmental development strategies (Ministry of Finance Citation2020) and programmes (Ministry of Environment Citation2021) discuss circular economy in the planning context. However, these initiatives express objectives and means for the circular economy on a general level, leaving space for territorialization work at the local level of implementation.

4.1.2. Territorialization

Territorialization of the transformative vision requires translating it into ‘planning language’. The circular economy is used in city and regional council documents, from general strategies to detailed zoning codes, but the planning practitioners have had difficulties to comprehend its potential impacts, benefits and actions required for implementation. The practitioners build their interpretations in two primary ways: by finding commonalities and connections with institutionalized concepts, such as resource efficiency and sustainable development, and by looking for circularity from the existing activities. Therefore, the practitioners prefer ‘incremental circularity’, focusing on continuums rather than a more holistic evaluation of existing planning principles and conventions, which in fact might contradict the objectives and means of the circular economy vision. When approached through sectoral planning processes, such as controlling and coordinating the reuse of excavated soil and rocks and construction sector waste (e.g. demolished concrete and other materials), the material substance becomes a focal point. Essentially, focusing on the material flows make sustainability benefits more visible and diverse actor-networks easier to comprehend. In the interviews, several sectors were explicated as central to circular economy advancement ().

Figure 3. Identified circular economy sectors (larger the oval size marks centrality in planning practice).

Reuse and circulation of infrastructure and other construction-related waste materials (e.g. landmasses and demolished concrete) were referred to in each of the interviews, and specific existing and planned measures to promote it were identified. Topics focusing on societal practices, such as flexible and shared use of indoor and outdoor spaces (e.g. yards) and infrastructure for sharing goods (e.g. cars and bicycles) also gained a lot of interest, but with less specific actions, instruments and practices.

In this case study, there were three main forums for translating the circular economy vision into action. Firstly, the cities and regional councils have applied the circular economy vision in their local strategies and programmes both in general and in more detail (e.g. explicate sectoral objectives). In five of the cities, the strategy work was facilitated by an R&D project in which they developed circular economy roadmaps at the city level, while also promoting ‘hands-on’ activities (e.g. on recycling). Furthermore, according to the planners, the circular economy objectives were often approached in strategies through established policy concepts, such as resource efficiency and sustainable development, without much specification. Another highlighted issue was related to the temporality of planning processes, as novel objectives introduced in the middle of processes raised resistance. Though remaining unspecific, the local strategic objectives were considered important as giving a ‘backbone’ for planners and to encourage piloting when legitimizing new ways of working.

Secondly, different types of experimental governance approaches were considered important in dealing with more pragmatic implications related to sectoral activities. For example, the cities utilized spatial planning pilot projects to experiment and understand the pragmatic prerequisites for change in land-use planning procedures ‘on the ground’. Such pilots provide a protected space for testing new rules in public properties, ‘since it is city-owned, it is easier for us there to search and execute [–] define goals and schedules’ (I1a). Different types of temporary organizations, such as collaborative research and development projects, have also been central in generating resources and circumventing existing procedural restrictions. The practical experiences of coordinating the reuse of excavated soil and rocks through spatial planning processes were considered valuable in developing, formulating, and implementing new kinds of zoning codes in collaboration with relevant stakeholders. Moreover, two of the cities have engaged in cross-city in-situ collaboration by establishing working groups, hiring landmass coordinators and adding zoning codes aimed to facilitate the reuse of materials. Especially, the landmass coordinators provide a spatial link by monitoring the supply and demand of surplus soils between project contexts. However, the planners also considered the complexities in reaching beyond informal coordination by pointing out potential procedural conflicts and risk of appeals caused by the too rapid integration of vague and difficult-to-measure circular economy targets into legally binding spatial plans.

Finally, the institutionalization of the circular economy might eventually narrow the policy scope to an ‘internal matter of urban environment service area’ (I4a). To avoid such sectoral silos, dedicated circular economy coordinators were raised as a step to facilitate the territorial development and implementation of strategies, programmes and knowledge sharing between sectoral experts often lacking in planning practice. The coordinators are given the role of intermediaries, internally (e.g. raising awareness) and between public sector and other actors (see Kanda et al. Citation2019). Overall, the intermediary actors are gaining importance in the operationalization of the circular economy visions and can also open space for novel connections and meanings (Baker, Hincks, and Sherriff Citation2010).

4.1.3. Planning practice

The planning practice serves complementary roles of controlling and enabling emerging activities. In Finland, statutory planning is managed on three primary legislative land-use planning levels: regional, master and detailed. There are few examples to build upon, when engaging with novel and experimental policy visions, like the circular economy. For planners, this means formulating new regulations from scratch, starting from phrasing, titles and symbols. As planning processes are strictly regulated and plans legally binding, this isn’t a straightforward task. Technical details also vary between the sectors in question calling for specialized skills across the sectors: ‘the planner should be then wiser than the sectoral experts if one decides to use regulations’ (I7b). If the planning processes are utilized to test and scale up novel modes of action, for example, in use of demolished materials, the best-available solutions may change drastically over the plan’s implementation timeframe, rendering detailed regulations challenging. In addition, amending an officially approved detailed level plan is only possible through bureaucratic alteration processes. As a solution, some planners emphasize the centrality of permitting processes – a technocratic rather than an inclusive practice – in steering land-use activities towards a more circular economy.

Despite reservations regarding the controlling role, the planners unanimously note the enabling role of planning processes in enhancing and setting conditions for circular economy actions – although the mix of practices was very diverse. For example, strategic thematical regional and master plans and general outline plans were considered to provide flexibility, a broader planning horizon and the inclusion of stakeholders, although possibly losing some regulatory power in steering circular activities. Also, public–private partnerships in planning processes were identified as solutions in acknowledging the interests of private-sector actors early in the spatial planning process and sharing responsibilities in planning and implementation more evenly. These are important considerations since planning is also seen as co-productive process rather than a performance-based activity evaluated solely on the basis of immediate outcomes. Moreover, in the interviews, the role of planning instruments is explicated for facilitating and guiding the reuse of landmasses, which has direct land-use impacts, but has little capacity in orchestrating the more immaterial aspects of circular economy, such as mobility and energy. As one planner states

… in all of these energy and other environmental issues there is always a hope of solving things with putting it into the plan [–] but I try to highlight to myself that plan is a document focused on land-use planning, so we need to think what land-use issues there are to be solved. (I7a)

From the planner’s perspective, controlling and enabling roles are not separate but require constant dialogue and navigation. A fundamental aspect of the planner’s daily work is balancing different, and often conflicting, interests, value claims, legal obligations and policies. For the circular economy, systemic transitions are difficult to break down into clear benefits for individual actors. Current legislation offers little pragmatic steering towards circular practices, which places further pressure on the planner: ‘it [circular economy] doesn’t get realised only with planning regulations, it must be added to legislation as well so that there will be changes on a larger scale’ (I4b). The issue will be addressed partially in the ongoing reform but requires the mobilization of lessons from planning practice into the policy sphere. The planners from the different cities agree on the necessity to reconsider the knowledge base and instruments for the circular economy. However, the implementation differs in terms of positioning planning as a process to enable transitions or a statutory plan as an outcome to control transitions.

4.2. Blue bioeconomy in planning

4.2.1. Transformative visions

The blue bioeconomy is another novel transformative policy vision that lacks a uniform definition and is operationalized in multiple ways. In the EU, it emerged in the later 2010s, at the intersection of oceanic and terrestrial strategies. The oceanic interpretation focuses on blue resource management in oceans, e.g. introducing more sensitive technologies and techniques and promoting safeguards for the most vulnerable areas and species (Eikeset et al. Citation2018). The terrestrial blue bioeconomy strategies emphasize the development of new types of products and knowledge, and more efficient utilization of water in land-based production chains (Vieira, Leal, and Calado Citation2020). The European bioeconomy roadmap defines the strategic importance of the sector by promoting the role of aquatic environments in meeting the increasing global food demand, the capacity of blue biotechnology in harnessing underutilized aquatic resources and the reinstated focus on ecosystem-based solutions that help to acknowledge potential sustainability trade-offs (Ligtvoet et al. Citation2019, 9–11).

The Finnish National Development Plan for Blue Bioeconomy discusses the role of water resources in coping with global sustainability challenges and creates three distinct transformative visions (Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry Citation2016). First, the blue bioeconomy is framed as a source of solutions to provide sustainable food, energy and clean water. Technological innovations and the use of previously underutilized resources, like algae, can contribute to meeting the increasing nutrient and protein demand and circular solutions have the potential in providing renewable energy. However, blue resource-use carries long extractivist histories (e.g. over-fishing) that cast a shadow of doubt over the sustainability of policies aimed at underutilized blue resources (Winder and Le Heron Citation2017). Second, water environments and landscapes perform an important role as a source of wellbeing and immaterial cultural services. Incumbent visions overlook the distributed cultural aspects of the environment, which also plays an increasingly important economic role because of global trends in nature tourism. Third, the protection of existing ecosystem potentials and the rejuvenation of declined capacities is a central aspect of the Finnish blue bioeconomy. This economic expectation is also aligned with the policy goal of good ecological status of all water bodies institutionalized in the European Water Framework Directive (WFD) (European Commission Citation2000). Due to their generalized nature, the policies overlook the more nuanced spatialities, histories and stakeholder perspectives on blue resource geographies (Albrecht and Lukkarinen Citation2020). Furthermore, the existing planning instruments, like the marine spatial planning (MSP) procedures, remain poorly equipped in facilitating dialogues regarding socio-ecological developments and extensive growth policies (Kidd and Ellis Citation2012; Winder and Le Heron Citation2017).

4.2.2. Territorialization

In this case study, a transition arena was formed as the forum for territorializing the blue bioeconomy vision from a regional perspective in Southwest Finland. The arena process was not part of the official strategic regional planning procedures but offered an informal space for the planners to reflect on future developments with key stakeholders across the blue bioeconomy sectors. At the beginning of the process, the stakeholders, facilitators and regional planners translated the vision through three principles: (1) focusing on food system transitions; (2) setting the boundary conditions of the Archipelago Sea’s good ecological status (necessitated in the WFD); and (3) identifying measures to enhance sustainable production solutions and consumption practices. The construction of a ‘regional stakeholder’ (Metzger Citation2013a) does not assume full consensus over the framing, rather a shared diagnosis of the agenda to facilitate meaningful discussions. More explicitly, the transition arena focused on building transition pathways for reorganizing fish aquaculture, economizing underutilized blue resources and developing innovative water protection solutions for manure processing (). Each of the topics poses specific systemic challenges and they also inform spatial planning more generally. Alternative themes focusing on the development of blue biotechnology, energy production and the recreational role of water resources were brought up in the discussions but were considered secondary from the spatial planning perspective, and thus excluded from the process. Furthermore, there were issues too politically sensitive to be included in the blue bioeconomy vision, especially dispersed nutrient discharges from forestry and point sources of urban waste-water treatment, which can be considered as ‘elephants in the blue bioeconomy room’.

4.2.3. Planning practice

In each of the subject areas, the territorialization of the blue bioeconomy unfolds around two recurring dynamics. On the one hand, the inadequate coordination and alignment of governmental policies was considered to hinder the implementation of regional blue bioeconomy development. The vague national targets do not ‘scale down’ to territorial planning decisions without active dialogue and intermediation, which has not been embraced by the responsible ministries. The problem was pinned down to ‘lacking’ or ‘patchy’ food policy at the national scale that evades explicit sustainability goals and deals incrementally with ‘end of the pipe’ impacts which are not equipped to deal with land-based nutrient sources. Therefore, spatial planning becomes positioned to combine and implement non-compatible growth and sustainability goals on an ad hoc basis. On the other hand, to be effective, the planning processes should build on socio-material networks linked to emerging collaborative practices, business models and production techniques. In manure processing, system operators or farmer co-operatives could establish processes to gather excess manure to centralized processing facilities to produce biogas and organic fertilizers, while simultaneously minimizing nutrient flows to the sea. In fish aquaculture, incentives, such as nutrient compensation markets, could formulate the basis for technological advancements (e.g. multitrophic aquaculture). The use of underutilized resources requires a strategic planning push to develop new integrated production chains for harnessing dispersed resources. Furthermore, the emergence of such networks and practices requires a societal push for coordination to be taken up by, and between, the responsible ministries (especially the Ministry of Environment and Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry).

The transition arena, therefore, emerged as an intermediary space that reveals important governance mismatches in the blue bioeconomy context. First, vertically, efficient spatial planning in regional and local contexts requires initiative at the national level to become effective. Second, horizontally, the sectoral developments narrow the view unnecessarily, and for example, the sustainable fish aquaculture practices cannot emerge in a vacuum but require a holistic view of all the activities taking place in spatial proximity. Finally, the lack of coordination between land-based and sea-based developments constitutes a situation, where there are little transition incentives for the sector-specific developments. The blue bioeconomy transitions and their interactions have to be simultaneously considered in land-based and sea-based planning.

From a strategic planning practice perspective, the transition arena opened critical discussions. For the regional planners, the tools and instruments of collaborative visioning, pathway creation and scenario building were familiar, for example, to the processes of marine spatial planning and regional strategic planning. However, the detailed discussions crossing sectoral boundaries and explicit focus on regional transition visions complement the existing planning practice by explicating the links between sea-based and land-based planning regimes and emphasizing the enabling role of planning. The arena – together with other existing developments – created a strong push for regional navigation and the coordination of business collaboration around underutilized blue resources, especially Baltic herring (Clupea harengus membras). Baltic herring is the most important commercial fish catch in the region, with an annual catch of over 100 million kg over the last decade, but around 75% of the catch ends up as animal feed and only 3% as food production (Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry Citation2021). Therefore, the efforts to alter the herring value chains were considered necessary in creating new markets also for other underutilized blue products and changing the operational environment for the blue bioeconomy. The boundaries set by national policies and legislation, however, confine the operational space of transformative planning for the blue bioeconomy and require a policy instrument mix to enhance coherence between the land-based and sea-based activities.

5. Discussion and conclusions

The transformative visions of the circular economy and the blue bioeconomy pose challenges for spatial planning in combining novel economic activities and production methods with existing sectoral practices and materialities in a spatially diverging way. The transformative visions often emerge as flexible, formless and underdeveloped, but they can also designate practices that in fact are maintaining incumbent ways of doing (Nylén Citation2019; Valve et al. Citation2021). This places interpretation, evaluation and legitimation pressures on planners and planning processes, as identified in the two cases. In this paper, we have developed a framework that focuses on the mobilization of transformative policy visions, territorialization work in different contexts and implications for established planning practices – answering our first research question: ‘how are transformative policy visions and agendas translated into planning practices?’ (see ).

Table 2. Case study summary.

In the following, we turn to the ‘mobilization’ of transformative planning to answer our second research question: ‘what kinds of planning dynamics are central in the institutionalization of sustainability transition agendas?’ Firstly, the intervention by performative policy visions and related sustainability challenges opens ‘temporal space for novel practices and planning methodologies’, where public actors utilize experimentation as a mode of governance to coordinate previously isolated activities and actors (Huitema et al. Citation2018). However, in practice, governance experimentation often ties the sustainability transition orientations to steer existing large-scale activities (Loorbach, Frantzeskaki, and Huffenreuter Citation2015; Peck and Theodore Citation2015) – such as landmass coordination and reuse of demolition materials in the circular economy case or fish aquaculture in the blue bioeconomy case. On one hand, this materialist transition orientation has favoured an incremental framing of sectoral dynamics. The risk is that it might come at the expense of establishing new institutional rules and enabling conditions for novel and more transformative types of activities that do not readily fit the institutional context, such as circular mobility transitions or algae biomass value chains in our case studies. On the other hand, planning can fulfil an active orchestrating role by establishing novel connections and operational practices, such as manure processing in the blue bioeconomy case, while specifying directions, where detached sustainability concerns can be approached simultaneously. Our cases also show that the public sector can utilize publicly coordinated processes and dedicated public–private partnerships to institutionalize transformative practices in contextually defined ways, which is a highly policy-relevant notion meriting further empirical research.

Secondly, both cases offer perspectives on how planning processes perform ‘an intermediary role of arranging knowledge co-production in the territorial contexts’ (cf. Kanda et al. Citation2019), while also revealing institutional obstacles in the legislation, incentive structures and sector-specific practices. An important aspect is that the mediation can be profoundly bidirectional, such as reflecting lessons and providing generalizations on, e.g. land-use pilots, network building and experimental arrangements towards policy instrument design. For example, the ongoing revisions of the Finnish Land Use and Building Act are aiming to build on the circular economy experiences from the case study cities, although in an ad hoc and piecemeal way. The planning processes also define boundaries for the abstract visions by providing safeguards and setting standards for activities, such as the reuse of landmasses in the circular economy case. This is a pragmatic test for the sustainability and value claims of new practices necessary for the longer term legitimacy of the societal transformations. Explicating and navigating these different and potentially contradictory temporalities of transitions is an important aspect of the co-productive planning processes (Hiller and Healey Citation2008). However, many planners question the permanence of the change brought by governance experimentation, because the activities are sheltered from some of the procedural complexities and rigorous legislative definitions.

Finally, transformative visions are not translated to planning practice as packages, but rather broken down to contextual priorities and prerequisites. A planning perspective explicates ‘the multi-scalar dynamics of sustainability transitions’ since the territorial orchestration of diverse interests also requires a reconfiguration of regime policies on the national and EU level. Our empirical cases emphasize the regional preconditions for change and identification of misaligned policy incentives especially between the national level and regional level, as well as considering the patchy land-based and sea-based governance frameworks in the case of the blue bioeconomy. The construction of a ‘regional stakeholder’ (Metzger Citation2013b) calls for the identification of systemic links between sectoral activities, stakeholder contexts and planning regimes, which can, consequently, dispel the interpretively flexible transformative visions. Therefore, the role of planning for transitions should be more nuanced than spatial plans or policy visions acknowledge, carrying out in practice the necessary dialogue also between the theory of and theory in planning.

To conclude, it is necessary to note that the translating role of planning in transitions reaches beyond the passive implementation of transformative policy visions in specific spatial contexts. Although the territorializing function helps to identify concrete sectoral dynamics, where policies become workable in a contextually sensitive way, planning practices are struggling to combine the controlling and enabling functions. Moreover, the planning instruments and methods serve also legitimizing and inclusive roles in societal transitions reaching beyond imminent material concerns of sectorally embedded actors.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge participants in the 2020 YHYS fall colloquium session “The spatial and regional dimensions of sustainability transitions” and researcher Aino Rekola for constructive comments on the initial paper idea as well as the anonymous reviewer for critical remarks that significantly improved our argumentation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Albrecht, M., and J. Lukkarinen. 2020. “Blue Bioeconomy Localities at the Margins: Reconnecting Norwegian Seaweed Farming and Finnish Small-Scale Lake Fisheries with Blue Policies.” Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 38 (7–8): 1465–1483. doi:10.1177/2399654420932572.

- Albrechts, L. 2004. “Strategic (Spatial) Planning Reexamined.” Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 31 (5): 743–758. doi:10.1068/b3065.

- Albrechts, L. 2012. “Reframing Strategic Spatial Planning by using a Coproduction Perspective.” doi:10.1177/1473095212452722

- Albrechts, L. 2015. “Ingredients for a More Radical Strategic Spatial Planning.” Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 42 (3): 510–525. doi:10.1068/b130104p.

- Albrechts, L., and A. Balducci. 2013. “Practicing Strategic Planning: In Search of Critical Features to Explain the Strategic Character of Plans.” Disp 49 (3): 16–27. doi:10.1080/02513625.2013.859001.

- Albrechts, L., A. Barbanente, and V. Monno. 2020. “Practicing Transformative Planning: The Territory-Landscape Plan as a Catalyst for Change.” City, Territory and Architecture 7 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1186/s40410-019-0111-2.

- Avelino, F., and J. Grin. 2017. “Beyond Deconstruction. a Reconstructive Perspective on Sustainability Transition Governance.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 22: 15–25. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2016.07.003.

- Baker, M., S. Hincks, and G. Sherriff. 2010. “Getting Involved in Plan Making: Participation and Stakeholder Involvement in Local and Regional Spatial Strategies in England.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 28: 574–595. doi:10.1068/c0972.

- Bakker, S., and B. Budde. 2012. “Technological Hype and Disappointment: Lessons from the Hydrogen and Fuel Cell Case.” Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 24 (6): 549–563. doi:10.1080/09537325.2012.693662.

- Bakker, S., H. Van Lente, and M. Meeus. 2011. “Arenas of Expectations for Hydrogen Technologies.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 78 (1): 152–162. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2010.09.001.

- Berkhout, F. 2006. “Normative Expectations in Systems Innovation.” Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 18 (3–4): 299–311. doi:10.1080/09537320600777010.

- Bolger, K., and A. Doyon. 2019. “Circular Cities: Exploring Local Government Strategies to Facilitate a Circular Economy.” European Planning Studies 27 (11): 2184–2205. doi:10.1080/09654313.2019.1642854.

- Borup, M., N. Brown, K. Konrad, and H. Van Lente. 2006. “The Sociology of Expectations in Science and Technology.” Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 18 (3/4): 285–298. doi:10.1080/09537320600777002.

- Bos, J., R. Brown, and M. Farrelly. 2015. “Building Networks and Coalitions to Promote Transformational Change: Insights from an Australian Urban Water Planning Case Study.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 15: 11–25. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2014.10.002.

- Boulding, K. 1966. “The Economics of the Coming Spaceship Earth.” Environmental Quality Issues in a Growing Economy 1–8. doi:10.4324/9781315064147.

- Brandão, M., D. Lazarevic, and G. Finnveden. 2020. “Prospects for the Circular Economy and Conclusions.” In Handbook of the Circular Economy, edited by M. Brandão, D. Lazarevic, and G. Finnveden, 505–514. Cheltenham: Edward Edgar Publishing.

- Callon, M., and J. Law. 2005. “On Qualculation, Agency, and Otherness.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 23 (5): 717–733. doi:10.1068/d343t.

- Campbell-Johnston, K., J. ten Cate, M. Elfering-Petrovic, and J. Gupta. 2019. “City Level Circular Transitions: Barriers and Limits in Amsterdam, Utrecht and The Hague.” Journal of Cleaner Production 235: 1232–1239. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.06.106.

- Davoudi, S. 2001. “Planning and the Twin Discourses of Sustainability.” In Planning for a Sustainable Future, edited by S. Batty, S. Davoudi and A. Layard, 81–94. New York: Taylor & Francis.

- Eames, M., W. Mcdowall, M. Hodson, and S. Marvin. 2006. “Negotiating Contested Visions and Place-Specific Expectations of the Hydrogen Economy.” Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 18 (3–4): 361–374. doi:10.1080/09537320600777127.

- Eikeset, A.., A. Mazzarella, B. Davíðsdóttir, D. Klinger, S. Levin, E. Rovenskaya, and N. Stenseth. 2018. “What Is Blue Growth? The Semantics of ‘Sustainable Development’ of Marine Environments.” Marine Policy 87: 177–179. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2017.10.019.

- European Commission. 2000. “Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council Establishing a Framework for Community Action in the Field of Water Policy.” OJ L327, 22.12.2000. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:32000L0060:en:NOT

- European Commission. 2012. “COM (2012) 494 final. Blue Growth Opportunities for Marine and Maritime Sustainable Growth.” https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A52012DC0494

- European Commission. 2019a. “COM(2019) 640.” The European Green Deal 53 (9): 1689–1699. doi:10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004.

- European Commission. 2019b. Report from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions on the implementation of the Circular Economy Action Plan.

- European Commission. 2020. The EU Blue Bioeconomy Report 2020.

- Faludi, A. 1973. Planning Theory. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

- Flyvbjerg, B. 2006. “Five Misunderstandings About Case-Study Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 12: 219–245. doi:10.1177/1077800405284363

- Frantzeskaki, N., V. Castán Broto, L. Coenen, and D. Loorbach, eds. 2017. Urban Sustainability Transitions. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315228389.

- Fuenfschilling, L., N. Frantzeskaki, and L. Coenen. 2019. “Urban Experimentation & Sustainability Transitions.” European Planning Studies 27 (2): 219–228. doi:10.1080/09654313.2018.1532977.

- Georgescu-Roegen, N. 1971. The Entropy Law and the Economic Process. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Gomart, E., and M. Hajer. 2003. “Is That Politics? For an Inquiry into Forms in Contemporary Politics.” In Social Studies of Science and Technology: Looking Back, Ahead, edited by B. Joerges and H. Nowotny, 33–61. doi:10.1007/978-94-010-0185-4

- Healey, P. 2006. “Relational Complexity and the Imaginative Power of Strategic Spatial Planning.” European Planning Studies 14 (4): 525–546. doi:10.1080/09654310500421196.

- Hiller, J., and P. Healey. 2008. Contemporary Movements in Planning Theory. Critical Essays in Planning Theory. London: Routledge.

- Hillier, J. 2003. “Agon’izing Over Consensus: Why Habermasian Ideals Cannot Be ‘Real’.” Planning Theory 2 (1): 37–59. doi:10.1177/1473095203002001005

- Hobson, K. 2021. “The Limits of the Loops: Critical Environmental Politics and the Circular Economy.” Environmental Politics 3 (1–2): 161–179. doi:10.1080/09644016.2020.1816052.

- Huitema, D., A. Jordan, S. Munaretto, and M. Hildén. 2018. “Policy Experimentation: Core Concepts, Political Dynamics, Governance and Impacts.” Policy Sciences 51 (2): 143–159. doi:10.1007/s11077-018-9321-9.

- Hyysalo, S., J. Lukkarinen, P. Kivimaa, R. Lovio, A. Temmes, M. Hildén, T. Marttila, et al. 2019. “Developing Policy Pathways: Redesigning Transition Arenas for mid-Range Planning.” Sustainability 11 (3): 1–22. doi:10.3390/su11030603.

- Jasanoff, S. 2004. “Ordering Knowledge, Ordering Society.” In States of Knowledge: The Co-Production of Science and Social Order, edited by S. Jasanoff, 13–45. New York: Routledge.

- Kanda, W., P. del Río, O. Hjelm, and D. Bienkowska. 2019. “A Technological Innovation Systems Approach to Analyse the Roles of Intermediaries in Eco-innovation.” Journal of Cleaner Production 227: 1136–1148. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.04.230.

- Kidd, S., and G. Ellis. 2012. “From the Land to Sea and Back Again? Using Terrestrial Planning to Understand the Process of Marine Spatial Planning.” Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning 14 (1): 49–66. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2012.662382.

- Kivimaa, P., S. Hyysalo, W. Boon, L. Klerkx, M. Martiskainen, and J. Schot. 2019. “Passing the Baton: How Intermediaries Advance Sustainability Transitions in Different Phases.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 31: 110–125. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2019.01.001.

- Köhler, J., F. Geels, F. Kern, J. Markard, E. Onsongo, A. Wieczorek, F. Alkemade, et al. 2019. “An Agenda for Sustainability Transitions Research: State of the Art and Future Directions.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 31: 1–32. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2019.01.004.

- Kovacic, Z., R. Strand, and Thomas Völker. 2020. The Circular Economy in Europe: Critical Perspectives on Policies and Imaginaries. London: Routledge.

- Lazarevic, D., and H. Valve. 2017. “Narrating Expectations for the Circular Economy: Towards a Common and Contested European Transition.” Energy Research & Social Science 31: 60–69. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2017.05.006.

- Ligtvoet, A., F. Maier, L. Sijtsma, B. van den Broek, A. Doranova, D. Eaton, T. Guznajeva, et al. 2019. Blue Bioeconomy Forum: Roadmap for the Blue Bioeconomy. doi:10.2826/605949

- Loorbach, D., N. Frantzeskaki, and R. Huffenreuter. 2015. “Transition Management Taking Stock from Governance Experimentation.” The Journal of Corporate Citizenship 58: 48–66.

- Mäntysalo, R. 2013. “Coping with the Paradox of Strategic Spatial Planning.” Disp 49 (3): 51–52. doi:10.1080/02513625.2013.859009.

- Marcuse, P. 2017. “From Utopian and Realistic to Transformative Planning.” In Encounters in Planning Thought, edited by B. Haselsberger, 35–50. doi:10.4324/9781315630908

- Marres, N. 2007. “The Issues Deserve More Credit: Pragmatist Contributions to the Study of Public Involvement in Controversy.” Social Studies of Science 37 (5): 759–780. doi:10.1177/0306312706077367.

- Metzger, J. 2013a. “Placing the Stakes: The Enactment of Territorial Stakeholders in Planning Processes.” Environment and Planning A 45 (4): 781–796. doi:10.1068/a45116.

- Metzger, J. 2013b. “Raising the Regional Leviathan: A Relational-Materialist Conceptualization of Regions-in-Becoming as Publics-in-Stabilization.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 37 (4): 1368–1395. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12038.

- Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry. 2016. Kasvua vesiosaamisesta ja vesiluonnonvarojen kestävästä hyödyntämisestä: Sinisen biotalouden kansallinen kehittämissuunnitelma 2025.

- Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry. 2021. Kotimaisen kalan edistämisohjelma. Accessed November 3, 2021. https://mmm.fi/kalat/strategiat-ja-ohjelmat/kotimaisen-kalan-edistamisohjelma.

- Ministry of agriculture and Forestry. 2018. Out of the Blue: Sinisen biotalouden tutkimus- ja osaamisagenda. Accessed April 2, 2022. http://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/handle/10024/160942

- Ministry of Environment. 2021. Strategic Programme to Promote a Circular Economy. Accessed July 5, 2021. https://ym.fi/en/strategic-programme-to-promote-a-circular-economy.

- Ministry of Finance. 2020. Stronger Together: Cities and Central Government Creating Sustainable Future. Accessed April 2, 2022. http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-367-319-9.

- Newman, P. 2008. “Strategic Spatial Planning: Collective Action and Moments of Opportunity.” European Planning Studies 16 (10): 1371–1383. doi:10.1080/09654310802420078.

- Nylén, E. 2019. “Can Abstract Ideas Generate Change? The Case of the Circular Economy.” In Leading Change in a Complex World: Transdisciplinary Perspectives, edited by A. Kangas, J. Kujala, A. Heikkinen, A. Lönqvist, H. Laihonen, and J. Bethwaite, 281–299. Tampere: Tampere University Press.

- Parks, D. 2019. “Energy Efficiency Left Behind? Policy Assemblages in Sweden’s Most Climate-Smart City.” European Planning Studies 27 (2): 318–335. doi:10.1080/09654313.2018.1455807.

- Peck, J., and N. Theodore. 2015. “Fast Policy: Experimental Statecraft at the Thresholds of Neoliberalism.” In Fast Policy: Experimental Statecraft at the Thresholds of Neoliberalism. doi:10.1177/0094306116671949mm.

- Prendeville, S., E. Cherim, and N. Bocken. 2018. “Circular Cities: Mapping Six Cities in Transition.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 26: 171–194. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2017.03.002.

- Reike, D., W. Vermeulen, and S. Witjes. 2018. “The Circular Economy: New or Refurbished as CE 3.0? – Exploring Controversies in the Conceptualization of the Circular Economy Through a Focus on History and Resource Value Retention Options.” Resources Conservation & Recycling 135: 246–264. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2017.08.027.

- Rotmans, J., R. Kemp, and M. van Asselt. 2001. “More Evolution than Revolution: Transition Management in Public policy.” Foresight 3 (1): 15–31. doi:10.1108/14636680110803003.

- Roy, A. 2009. “Civic Governmentality: The Politics of Inclusion in Beirut and Mumbai.” Antipode 41 (1): 159–179. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8330.2008.00660.x.

- Sitra. 2016. Leading the Cycle Finnish Road Map to a Circular Economy 2016–2025. Helsinki: Sitra.

- Song, L. 2015. “Race, Transformative Planning, and the Just City.” Planning Theory 14 (2): 152–173. doi:10.1177/1473095213517883.

- Steele, W. 2011. “Strategy-making for Sustainability: An Institutional Learning Approach to Transformative Planning Practice.” Planning Theory and Practice 12 (2): 205–221. doi:10.1080/14649357.2011.580158.

- Valve, H., J. Lukkarinen, A. Belinskij, P. Kara, L. Kolehmainen, A. Klap, R. Leskinen, et al. 2019. Lisäarvoa kalasta ja maatalouden sivuvirroista Varsinais-Suomessa: Sinisen biotalouden murrosareenan tulokset. Accessed April 2, 2022. https://blueadapt.fi/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Lisa%CC%88arvoa-kalasta-ja-maatalouden-sivuvirroista-Varsinais-Suomessa_Sinisen-biotalouden-murrosareenan-tulokset_BlueAdapt.pdf

- Valve, H., D. Lazarevic, and N. Humalisto. 2021. “When the Circular Economy Diverges: The Co-evolution of Biogas Business Models and Material Circuits in Finland.” Ecological Economics 185: 107025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2021.107025.

- van Lente, H. 2012. “Navigating Foresight in a sea of Expectations: Lessons from the Sociology of Expectations.” Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 24 (8): 769–782. doi:10.1080/09537325.2012.715478.

- Vieira, H., M. Leal, and R. Calado. 2020. “Fifty Shades of Blue: How Blue Biotechnology Is Shaping the Bioeconomy.” Trends in Biotechnology 38 (9): 940–943. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2020.03.011.

- Vierikko, K., H. Nieminen, V. Salomaa, J. Häkkinen, J. Salminen, and J. Sorvari. 2020. Kiertotalous maankäytön suunnittelussa Kaavoitus kestävän ja luonnonvaroja säästävän kaupunkiympäristön edistäjänä. https://helda.helsinki.fi/handle/10138/322882.

- Voß, J., A. Smith, and J. Grin. 2009. “Designing Long-Term Policy: Rethinking Transition Management.” Policy Sciences 42 (4): 275–302. doi:10.1007/s11077-009-9103-5

- von Wirth, T., L. Fuenfschilling, N. Frantzeskaki, and L. Coenen. 2019. “Impacts of Urban Living Labs on Sustainability Transitions: Mechanisms and Strategies for Systemic Change Through Experimentation.” European Planning Studies 27 (2): 229–257. doi:10.1080/09654313.2018.1504895.

- Winder, G., and R. Le Heron. 2017. “Assembling a Blue Economy Moment? Geographic Engagement with Globalizing Biological-Economic Relations in Multi-use Marine Environments.” Dialogues in Human Geography 7 (1): 3–26. doi:10.1177/2043820617691643.

- Wolfram, M. 2016. “Conceptualizing Urban Transformative Capacity: A Framework for Research and Policy.” Cities 51: 121–130. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2015.11.011.

- Wolfram, M. 2018. “Urban Planning and Transition Management: Rationalities.” Instruments and Dialectics 11: 415. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-69273-9.

- Wolfram, M., N. Frantzeskaki, and S. Maschmeyer. 2016. “Cities, Systems and Sustainability: Status and Perspectives of Research on Urban Transformations.” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 22: 18–25. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2017.01.014.