ABSTRACT

In recent years, regional innovation policies across Europe have relied on the smart specialisation approach to support new path development. However, its focus on endogenous knowledge flows remains a major weakness of the approach. This article argues that smart specialisation has to adopt an outward-looking approach that combines knowledge flows external and internal to the region. Based on four stylised types of regions, the article proposes generic strategies that can be pursued through smart specialisation. In terms of its policy implications, the article argues that policymakers should develop their regions’ external connectedness strategically to leverage complementarities in global knowledge flows for new path development.

1. Introduction

Smart specialisation has become the cornerstone of some regional innovation policy in Europe. The past few years have witnessed ever-growing literature on the conceptual foundations of smart specialisation (Foray Citation2014) and its uptake in different types of regions (European Commission Citation2014; Foray Citation2014; McCann and Ortega-Argilés Citation2016; Trippl, Zukauskaite, and Healy Citation2020).

Smart specialisation and its underlying concepts champion policy support for place-based development, highlighting the mobilisation of endogenous potentials for innovation and new path development. This strategic focus on region-specific characteristics and potentials reflects an important deviation from previous ‘one size fits all’, place-neutral and spatially blind policy approaches and practices (Tödtling and Trippl Citation2013; Barca, McCann, and Rodríguez-Pose Citation2012). Yet, the approach is problematic for a variety of reasons (e.g. Hassink and Gong Citation2019; Benner Citation2020; Hassink and Kiese Citation2021). In this article, we focus on the particular weakness of the inward-looking orientation of smart specialisation. We contend that despite the recognition of the role of extra-regional linkages in the literature (e.g. Foray et al. Citation2012; Camagni and Capello Citation2013; McCann and Ortega-Argilés Citation2015), smart specialisation and its underlying concepts, such as regional innovation systems (RISs), regional diversification and new path development, tend to over-emphasise the endogenous determinants of a region’s innovation capacity and do not provide a nuanced view on the importance of external connectedness, linkages and (inter-)dependencies for inducing innovation-based structural change (see also Hassink, Isaksen, and Trippl Citation2019; Yeung Citation2021).

New path development in regions is often strongly shaped by exogenous influences. These may range from the rise of new competitors elsewhere to global technological development, institutional change (e.g. new standards, laws, regulations and policy programmes set at higher spatial scales) and changing market conditions. While we acknowledge the importance of non-local dynamics besides knowledge acquisition from external sources (Binz, Truffer, and Coenen Citation2016), we focus on exploring how flows of knowledge may affect new path development in regions. The latter is the key aim of smart specialisation where knowledge and innovation play a decisive role in developing new specialisations in regions.

Recent years have seen calls for a more outward-looking smart specialisation approach (Uyarra, Marzocchi, and Sorvik Citation2018). Regarding conceptual foundations, arguments for bringing the RIS concept and the new path development approach closer to the literature on global production and multiscalar innovation systems have been voiced (Hassink, Isaksen, and Trippl Citation2019; Yeung Citation2021). This article seeks to contribute to academic and policy debates on the role of external connectedness in innovation-based regional structural change (e.g. Crescenzi and Iammarino Citation2017; Trippl, Grillitsch, and Isaksen Citation2018; MacKinnon et al. Citation2019; Balland and Boschma Citation2021) by analysing how extra-regional knowledge acquisition could be combined with intra-regional knowledge circulation in different types of regions. More precisely, the aim of this article is to examine the role of a region’s external connectedness in relation to its endogenous knowledge circulation and to explore possibilities for policymakers to develop external knowledge acquisition strategically in smart specialisation. The article argues that regional innovation policies need to balance place-specific factors and external connectedness and proposes a typology of regions according to knowledge acquisition and circulation and by elaborating on specific strategies for each type of region. On the basis of these strategies, we draw conclusions for how smart specialisation strategies can promote tapping into extra-regional knowledge pools and disseminating knowledge regionally. We draw inspiration from concepts such as the ‘new argonauts’ (Saxenian Citation2007;Saxenian and Sabel, Citation2008) or ‘knowledge gatekeepers’ (Giuliani Citation2007; Giuliani and Bell, Citation2005; Morrison Citation2008) and follow the core idea that interlinkages between regions should not be seen as zero-sum game but as supportive for regions to enhance innovation (Saxenian Citation2007). These insights provide a rationale for developing smart specialisation into an outward-looking approach and for assessing how external connectedness can become an integral part of the design and implementation of smart specialisation policies.

The remainder of this article is organised as follows. First, we present the key concepts of smart specialisation, new path development and the multiscalarity of innovation. On this conceptual basis, we discuss exogenous sources for regional industrial transformation. We continue with a discussion of how the identified external connections interact with place-specific factors and how policymakers can support these interactions. Finally, we outline an agenda for future research.

2. Smart specialisation and multiscalarity

Smart specialisation incorporates concepts from economic geography (especially evolutionary economic geography) and innovation studies. So far, these concepts have focused more on local factors and less on the multiscalar nature of innovation-led structural change processes. In this section, we discuss the key concepts underlying smart specialisation and elaborate on recent scholarly debates on outward-looking perspectives to innovation and regional transformation.

2.1. Smart specialisation: core principles and limitations

An important cornerstone of smart specialisation is to achieve regional structural change by building on ‘local knowledge’ and ‘existing structures’ (Foray Citation2014, 498). The focus is on identifying potential activities with relevant scale and on doing so in an entrepreneurial discovery process (EDP) that includes actors from government, business, academia and society (Foray, David, and Hall Citation2009; Foray et al., Citation2012). The approach follows the logic of benefiting from agglomeration effects supposed to enhance the creation of synergies and enable structural change based on related diversification (Foray Citation2014; McCann and Ortega-Argilés Citation2015; Foray, Eichler, and Keller Citation2021).

A key difference to traditional regional development strategies is that smart specialisation moves learning and innovation to the fore for all types of regions, assuming that not only core areas but also traditional industrial regions and peripheral places show potentials to innovate and to promote new paths based ‘on their specific strengths, potentials and opportunities, rather than doing as others do’ (Foray, Eichler, and Keller Citation2021, 98).

In general, smart specialisation builds on an interactive understanding of innovation and acknowledges its place-specific nature. Inspired by evolutionary thinking, regional industrial change is seen as a branching process, particularly in regions with a high degree of related variety (Frenken and Boschma Citation2007; Foray Citation2014), hence reflecting the path dependence of regional industrial transformation (Martin and Sunley Citation2006). Therefore, smart specialisation addresses the promotion of innovation-based structural change and underlines the importance of regional context when designing policies. Hence, smart specialisation follows calls for more place-based regional innovation policies building on local knowledge and existing capabilities (Barca Citation2009; OECD Citation2009a, Citation2009b, Citation2011).

However, by focussing on endogenous transformation through related diversification (branching), smart specialisation faces two key limitations. First, the concept narrows structural change down to only one type of transformation, neglecting other forms of new path development (e.g. Martin and Sunley Citation2006). This is especially problematic when considering weakly developed or peripheral regions whose related diversification potential is usually low (Isaksen and Trippl Citation2016). More recently, work on new regional industrial path development (Martin and Sunley Citation2006; Tödtling and Trippl Citation2013; Isaksen and Trippl Citation2016; Grillitsch, Asheim, and Trippl Citation2018) has brought forward a nuanced understanding of regional structural change by identifying other forms of new path development than branching such as path creation, unrelated path diversification, path importation and path renewal.

As a second limitation, the smart specialisation concept has been criticised for lacking an outward-looking dimension (Radošević and Ciampi Stancova Citation2018; Uyarra, Marzocchi, and Sorvik Citation2018; Balland and Boschma Citation2021; Hassink and Kiese Citation2021) and neglecting that novelty generation in the globalised learning economy is not exclusively a localised phenomenon but is strongly influenced by external connectedness (Crevoisier and Jeannerat Citation2009; Binz and Truffer Citation2017; Isaksen and Trippl Citation2017; Trippl, Grillitsch, and Isaksen Citation2018). As Yeung (Citation2021, 992) states, regions ‘capitalize on region-specific assets and yet their key actors and institutions tap into extra-regional markets, production capabilities and flows of people, capital and technology’. Given the role of extra-regional linkages to acquire non-local knowledge (e.g. Foray et al. Citation2012; Camagni and Capello Citation2013), what drives regional transformation is the combination of endogenous and exogenous knowledge sources (Binz, Truffer, and Coenen Citation2016; Aslesen, Hydle, and Wallevik Citation2017; Chaminade et al. Citation2019) and, thus, the interplay between regional embeddedness and connectivity (McCann and Ortega-Argilés Citation2015; see also Camagni and Capello Citation2013). These insights lead to a multiscalar view of innovation.

2.2. The multiscalarity of innovation

In recent decades, non-local linkages have attracted increasing interest in economic geography and innovation studies. It has been argued that too much geographical proximity can increase lock-in due to too close social or cognitive proximity (Grabher Citation1993; Boschma Citation2005). Further, because globalisation has increased the fragmentation of innovation and knowledge creation, innovation processes have become less sticky in space (Markusen Citation1996) and can be understood in multiscalar frameworks (Ernst and Kim Citation2002a, Citation2002b; Coe and Bunnell Citation2003; Binz and Truffer Citation2017).

Innovation processes occur on and between various spatial scales (Bunnell and Coe Citation2001; Binz and Truffer Citation2017). Multiscalarity enables actors to zoom in and out when pursuing their strategies across space (Smith Citation1992; Swyngedouw Citation2004). Thus, ‘companies are simultaneously, intensely local and intensely global’ (Swyngedouw Citation2004, 38, emphasis in the original). Arguably, the same might hold true for other types of innovation actors, such as research institutes or networked professionals (Bergek et al. Citation2015; Binz and Truffer Citation2017).

In a multiscalar perspective, place-specific factors and external linkages can be thought to meet at ‘structural couplings’ (Bergek et al. Citation2015, 53) where ‘actors, actor networks or institutions span across or overlap between various subsystems’ (Binz and Truffer Citation2017, 1285). These couplings are the result of closed ‘conduits’ or open ‘channels’ as types of ‘network pipelines’ (Owen-Smith and Powell Citation2004). Bathelt, Malmberg, and Maskell (Citation2004) argue that pipelines cutting across spatial scales interact with the ‘local buzz’ of localised innovation processes and inject new knowledge. Pipelines and, more broadly, external linkages can enhance local innovation by bringing new knowledge to the region (Bathelt, Malmberg, and Maskell Citation2004; Morrison, Rabellotti, and Zirulia Citation2013). In the literature, these actors diffusing new knowledge into a focal region have been termed ‘knowledge gatekeepers’ (Giuliani and Bell Citation2005; Giuliani, Citation2007; Morrison Citation2008), such as universities (Goddard and Chatterton Citation1999) and regional innovation agencies (Morisson Citation2019).

However, to what degree these gatekeepers can diffuse knowledge to other actors is affected by their relative cognitive distance and absorptive capacity (Cohen and Levinthal Citation1990; Giuliani and Bell Citation2005; Giuliani, Citation2007; Morrison Citation2008). More generally, external connectedness can have negative consequences as well and even disrupt one path while favouring another, leading to serious friction in regional innovation and transformation strategies (Breul, Hulke, and Kalvelage Citation2021). More specifically, global knowledge pipelines can have a ‘dark side’ (Phelps, Atienza, and Arias Citation2018) because a too strong focus of actors on external relations can weaken the vibrancy of a regional innovation system (Bathelt, Malmberg, and Maskell Citation2004). These possible barriers need to be kept in mind when promoting the acquisition of extra-regional knowledge.

3. Unpacking exogenous knowledge sources for new path development

So far, new path development has widely been understood as an endogenous process. Over the past few years, scholars have begun to examine the role of extra-regional linkages in regional industrial transformation. The focus has largely been on FDI-related processes while neglecting other types of extra-regional sources (Yeung Citation2021). We follow Trippl, Grillitsch, and Isaksen (Citation2018) and distinguish between the arrival of non-local actors and non-local knowledge linkages. The arrival of actors can refer to organisations (such as firms or research institutes) and individuals (Trippl, Grillitsch, and Isaksen Citation2018; Wu Citation2021). Both types of actors may ‘inject’ new knowledge into the region. Non-local knowledge linkages can cover both formal and informal linkages. illustrates these exogenous knowledge sources and related mechanisms.

Table 1. Exogenous knowledge sources.

3.1. Arrival of actors from outside the region

Various studies support the view that external actors can play a powerful role in regional structural transformation. Focusing on Swedish regions, Neffke et al. (Citation2018) show that non-local firms and non-local entrepreneurs are important actors for diffusing unrelated knowledge in regions. This finding is corroborated by Elekes, Boschma, and Lengyel (Citation2019), who find that foreign MNCs in the manufacturing sector in Hungarian regions are key drivers for unrelated new-to-the-region activities. Bellandi, De Propris, and Vecciolini (Citation2021) find that indigenous firms in Italian industrial districts learn from MNCs and their localised subsidiaries.

The relocation of research and development (R&D) activities provides another mechanism for the inflow of non-local knowledge. Firms have expanded their R&D operations abroad to tap into regional knowledge pools and adapt to specific market demands (Malecki Citation2010). Apart from corporate R&D operations, the relocation of public research institutes can trigger structural change in regional economies. For instance, the case of the ICT and software cluster in Mühlviertel (Upper Austria) reveals that the transplantation of university research institutes to a less-developed region may pave the way for the creation of a path that is new to the region (Isaksen and Trippl Citation2017).

New path development may also be shaped by the mobility of individual actors. Saxenian (Citation2005, Citation2007) addresses the cases of highly-skilled migrant entrepreneurs in Silicon Valley who not only created start-ups in the host economy but also facilitated trade and investment flows to their home regions (see also Saxenian and Sabel Citation2008). Yeung (Citation2009) notes that transnational entrepreneurs gain experience by first being active in large MNCs and using these experiences later when operating their own firms (Yeung Citation2009). Binz, Truffer, and Coenen (Citation2016) find that returning highly-skilled entrepreneurs played a decisive role in the early formation of Beijing’s on-site wastewater recycling (OST) technology path. Their experiences gained abroad and their networks to these places provided knowledge linkages that underpinned the creation of a new path in Beijing (Binz, Truffer, and Coenen Citation2016). In the rise of biotechnology in Portugal’s Centro-Norte, Carvalho and Vale (Citation2018) observe how highly educated returnees started companies and maintained connections to their former research institutes. External knowledge was constantly pumped into the region through linkages to distant places (Carvalho and Vale Citation2018). Finally, highly skilled scientists represent another type of individual actors entering a region and possibly affecting regional path development (Trippl Citation2013). Generally, the outflows of highly skilled people are not only beneficial for the receiving region but could lead to the initiation of knowledge flows between the sending and the receiving region (Agrawal, Cockburn, and McHale Citation2006; Saxenian Citation2005; Trippl Citation2013).

3.2. Knowledge linkages

Regions can acquire non-local knowledge by establishing connections to actors located elsewhere. Depending on regional circumstances, regions may gain in various ways from the insertion into knowledge linkages. In the last years, access to non-local knowledge has been acknowlegded as particularly relevant for new path development in structurally weak regions (Barzotto et al. Citation2019; McCann and Ortega-Argilés Citation2015). Global or inter-regional knowledge linkages are often formal in nature, and these formal linkages are often associated with ‘pipelines’ and are developed through trade relations and outsourcing, R&D collaborations or subsidiaries of MNCs tapping into internal global innovation networks (Bathelt, Malmberg, and Maskell Citation2004; Lorenzen and Mudambi Citation2013; Owen-Smith and Powell Citation2004).

Strategic alliances or partnerships act as important channels for knowledge flows (Yeung Citation2021). For example, a technological lead firm from one (e.g. advanced) region can create linkages with suppliers in another (e.g. emerging) region through various mechanisms such as FDI, licensing, the transfer of machinery or technical assistance and thus link both regions (Ernst and Kim Citation2002b). The literature on global production networks (GPNs) refers to this as ‘strategic coupling’ (Coe and Yeung Citation2015). Hassink (Citation2021) observes that strategic coupling often occurs in clusters and proposes the notion of ‘strategic cluster coupling’. Yeung (Citation2021) argues that strategic coupling, for example, through a strategic partnership between an MNC from California and firms in Taiwan, leads to related diversification in both regions.

As for innovation networks as another mechanism for knowledge flows, MNCs control knowledge flows between subsidiaries dispersed in geographical space through ownership structures. Regional economies can benefit from subsidiaries’ internal knowledge dynamics as they act as knowledge diffusion actors in a RIS. Aslesen, Hydle, and Wallevik (Citation2017) show for specialised regions the importance of subsidiaries’ connections to their internal global networks, which are important extra-regional sources for incremental innovation. While ‘organizational proximity’ is relevant for learning within non-spatial innovation networks, ‘geographical proximity’ helps to bring this knowledge into the region (Aslesen, Hydle, and Wallevik Citation2017). The interplay of these knowledge networks with the RIS has led to path extension, rather than showing clear signs of new path development (Aslesen, Hydle, and Wallevik Citation2017). Informal linkages are of similar importance, for example, those held by highly qualified returnees. Both OST in Beijing (Binz, Truffer, and Coenen Citation2016) and biotechnology in Centro-Norte (Carvalho and Vale Citation2018) benefitted from the importance of informal knowledge linkages of individuals.

Crescenzi and Iammarino (Citation2017) emphasise that analyses of the connectivity of a region should not only focus on inflows but also on outflows, as individuals or firms can tap into new knowledge elsewhere. In their study of Italian regions, Ascani et al. (Citation2020) found that local innovation activities are complemented by external knowledge linkages provided by subsidiaries abroad, suggesting that outward foreign direct investment plays a crucial role for regional innovation. According to Ascani et al. (Citation2020), the local parent company building global networks acts as a gatekeeper in the region, although how this process works depends on the region’s absorptive capacity (Bathelt, Malmberg, and Maskell Citation2004; Trippl, Grillitsch, and Isaksen Citation2018). Balland and Boschma (Citation2021) suggest that external linkages can provide regions with further capabilities, but these linkages should occur with regions that can complement existing capabilities. Njøs, Orre, and Fløysand (Citation2017) examine inward investments of foreign MNCs and outward investments of local MNCs. The practices of incoming MNCs are found to support the further diversification of a cluster’s economic structure, while outward investment practices are found to further support existing structures leading to increasing specialisation. Hence, the interplay of inward and outward investments is important for continuing an existing path and leads to regional specialisation (Njøs, Orre, and Fløysand Citation2017).

4. Combining place-specific factors and exogenous knowledge sources

We argue that the interplay between place-specific factors and exogenous knowledge sources, in the form of either the arrival of new actors to a region or knowledge linkages, is beneficial for innovation-based structural change. A key question is how smart specialisation policies could support such an interplay.

4.1. Strategic coupling and anchoring in regional economies

As ‘no region is an “island” devoid of connectivity to the wider national and global economy’ (Yeung Citation2021, 996), a focus on the interplay between non-local linkages and place-specific factors is required. Scholarly debates on strategic coupling and anchoring can provide an inroad to gain a better understanding this interplay.

The global production networks (GPN) approach has enhanced our understanding of the role of non-local linkages in the value creation und upgrading process of regions. The GPN approach emphasises ‘the interactive complementarity (…) between localized growth factors and the strategic needs of trans-local actors in propelling regional development’ (Coe et al. Citation2004, 469). Here, the concept of ‘strategic coupling’, which is at the core of the GPN literature (Coe and Yeung Citation2015), provides a perspective for policymakers to support new path development. Regions adjust their assets to couple with the specific needs of lead firms’ globally organised production networks (Coe, Dicken, and Hess Citation2008; Coe and Yeung, Citation2015) and can leverage external linkages to create new assets (Binz, Truffer, and Coenen Citation2016) or support regional diversification and structural change (Neffke et al. Citation2018; Yeung Citation2021). While this view has a strong production-related focus and originally developed out of the ‘catching-up’ literature in the East Asian context (e.g. Coe and Yeung Citation2015; Yeung Citation2015), the notion of anchoring suggested by Crevoisier and Jeannerat (Citation2009) focuses on knowledge generation and innovation. Anchoring stresses the role of knowledge generation by mobilising and contextualising knowledge from other places. Accordingly, the mobility of knowledge from one place to another place leads to interaction with different contexts (Crevoisier and Jeannerat Citation2009). The incorporation of this de-contextualized knowledge from distant places by actors in a region through their relations with other actors within or outside a region is understood as anchoring (Crevoisier and Jeannerat Citation2009; Dahlström and James Citation2012). In this perspective, policy should target the ‘capacity to participate in multilocation knowledge dynamics and to anchor them’ (Crevoisier and Jeannerat Citation2009, 1233). Binz, Truffer, and Coenen (Citation2016) expand the notion of anchoring by extending it beyond knowledge to other important sources for early path creation, such as the mobilisation of markets, legitimation and investments.

4.2. A knowledge acquisition and circulation typology of regions

The role of anchoring knowledge from a different place and context becomes more crucial as interregional and international mobility increases (Crevoisier and Jeannerat Citation2009). Regional innovation policies should thus consider which activities are the most beneficial for a region and how they can be anchored. This trade-off will depend particularly on the specific interplay between endogenous and exogenous knowledge flows.

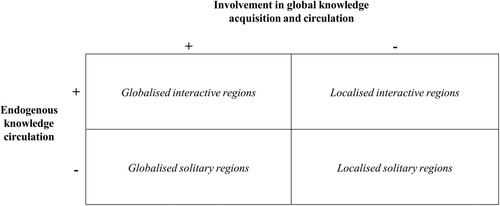

According to the RIS literature, regions differ in their industrial structures and their support systems, that is, they feature different endowments of industries, firms, research, education and knowledge transfer organisations (Tödtling and Trippl Citation2013; Isaksen and Trippl Citation2016). Hence, the specific arrangement and quality of place-based organisational set-ups are assumed to have a major influence on the innovation performance of regions. However, the focus of this literature is first and foremost on the internal innovation capacities (Isaksen and Trippl Citation2016). We seek to complement this perspective by stressing that a region’s external connectivity should be considered as a further important characteristic of regions and their innovation systems (see also McCann and Ortega-Argilés Citation2015). For example, Capello and Lenzi (Citation2013) argue that regions with their locally specific context can be classified under different modes of innovation, based on different innovation patterns, and these modes have implications for the interplay of internal and external knowledge. Hence, we suggest a typology of regions that distinguishes regions along their endogenous knowledge base and the quality of the internal knowledge circulation on one axis and their involvement in global knowledge acquisition on another axis (). This framework draws inspiration from earlier typologies suggested by Cooke (Citation2004), Isaksen and Trippl (Citation2016), Oinas, Trippl, and Höyssä (Citation2018), Tödtling and Trippl (Citation2013) and Trippl, Grillitsch, and Isaksen (Citation2018) but focuses specifically on the interactions between the two dimensions of knowledge circulation.

The following section discusses potential knowledge circulation strategies for each of the four region types and outlines implications for smart specialisation.

5. Towards an outward-looking approach for smart specialisation

Smart specialisation encourages internationalisation, including strategic alliances, outsourcing licencing, joint research or mergers and acquisition and FDI (Foray et al. Citation2012). For regional innovation policy, it is, therefore, necessary to understand the benefits of internationalisation strategies based on place-specific factors and to combine both strategically.

How external knowledge sources contribute to new path development is likely to vary according to the knowledge acquisition and circulation region types () which calls for a differentiated approach drawing on specific strategies for each type of region. These types include dynamic, prosperous regions but also structurally weak regions, which can benefit even more from a combination of external knowledge acquisition and internal knowledge circulation promoted through smart specialisation strategies (Barzotto et al. Citation2019).

5.1. Towards region-specific strategies

Globalised interactive regions are the most advanced regions in our framework. These regions are characterised by a strong and diversified industrial structure as well as a strong and diversified research and education base. This assures a dynamic and vivid knowledge circulation within the region and strong involvement in global knowledge flows (Isaksen and Trippl Citation2016; Oinas, Trippl, and Höyssä Citation2018; Trippl, Grillitsch, and Isaksen Citation2018). This might be due to the existence of MNCs, in many cases acting as global lead firms, and/or strong small specialised firms with international outreach (Cooke Citation2004). Gatekeepers in industry and the support system are responsible for a high degree of knowledge diffusion within the region and prevent regional lock-in (Boschma Citation2015; Morrison, Rabellotti, and Zirulia Citation2013). Globalised interactive regions have a high absorptive capacity with the proper abilities to internalise new knowledge (Oinas, Trippl, and Höyssä Citation2018). Diversity may provide many opportunities for innovation-based structural change but can create challenges when it comes to developing sound innovation strategies and prioritisation processes (Isaksen and Trippl Citation2016). A promising strategy is to target complex external knowledge, which can complement local knowledge circulation. Put differently, these regions should focus on anchoring external knowledge that complements and further advances the regional knowledge base (see also Capello and Lenzi Citation2013). It is thus important to enhance gatekeeper and boundary spanning activities between the region and distant places (Wu Citation2021). For smart specialisation this means to prioritise those clusters and activities with an intermediate cognitive distance that complement each other and focus on keeping the interaction between locally and globally interconnected actors intact. The EDP phase should incorporate this. It is further important to constantly observe a regions’ diversification progress and to monitor those more distant or emerging clusters that might not yet be sufficiently connected internationally.

Localised interactive regions have both a strong economic structure (often specialised in one or a few industries) and education base and therefore exhibit a high degree of endogenous knowledge circulation. Under the influence of key incumbent interest groups, those regions often feature resistance to change (Hassink and Kiese Citation2021). This lack of farsighted behaviour risks the missing of new technological opportunities, the maturation of industries and the outflow of talents. With the maturation of industries and constant homogenisation of knowledge (Menzel and Fornahl Citation2010), in the long term, these regions need access to non-local knowledge sources to renew their industrial base and gatekeepers for the diffusion of external knowledge within the region. What is more, local knowledge is not leaving the region, thus not undergoing a process of de-contextualisation (Crevoisier and Jeannerat Citation2009). The latter is important as highly specialised knowledge can act as a complementary asset in global value chains. Production stages have become increasingly fragmented, with specialised knowledge being a key requirement (Baldwin Citation2011). Localised interactive regions can tap into global value chains with more relational governance structures where knowledge is complementary, and learning processes are mutual (Gereffi, Humphrey, and Sturgeon Citation2005; Pietrobelli and Rabellotti Citation2009) and firms can obtain key high value-added tasks. Capello and Lenzi (Citation2013) stress that specialised knowledge in a region does not necessarily lead to innovation but can depend on inter-regional ‘co-invention’ (Foray, David, and Hall Citation2009). Further, as the example of industrial districts in Italy shows (Bellandi, De Propris, and Vecciolini Citation2021), internationalisation through offshoring and outsourcing of tasks will support regional transformation processes through unlearning or forgetting key tasks in some activities while learning new skills in others. This is a favourable strategy where de-contextualised knowledge from a distant place is anchored in a region and re-contextualised. Smart specialisation strategies should promote a closer interaction between the endogenous specialised knowledge base with external knowledge as the former could provide many unused potentials. This includes coupling between regional specialised firms and GPNs to obtain a key function, for example, through international partnerships or strategic alliances (Yeung Citation2015). Policymakers can design networking schemes to support linkages between internationalising and regionally-oriented actors. Another key strategy is to continuously evaluate regional networks to identify needs for renewal. A focus should be given on boundary spanning activities such as brokerage and trade fairs, which attract new actors to the region and develop strategic partnerships or collaborative research (Wu Citation2021).

Globalised solitary regions are characterised by the presence and dominance of foreign MNCs. The research and education base often features little or no linkages to those actors, resulting in weak knowledge diffusion. Here, cognitive distance to co-located firms and little interest in participating in regional networks limit the (innovation) benefits for the hosting regions (see also Giuliani and Bell Citation2005). A reason for this is that inward investments are mainly focused on exploiting natural resources or low labour costs (Barrientos, Gereffi, and Rossi Citation2011; MacKinnon Citation2013; Oinas, Trippl, and Höyssä Citation2018). Examples for these regions can be found in Southeast Asia or in Central and Eastern European transition countries (Blažek Citation2016). In globalised solitary regions, there is an opportunity to upgrade the existing firm base and to build stronger connections to branch plant firms. Furthermore, with the influx of new knowledge, the region can skip a step in the value chain ‘ladder’. As for challenges, a high dependency on external actors means a constant risk through disinvestments and external decision making (Oinas, Trippl, and Höyssä Citation2018). Another mechanism of anchoring new knowledge is to become a strategic partner in GPNs (Yeung Citation2021). In terms of development strategies, policymakers should consider de-coupling strategies (Horner Citation2014; MacKinnon Citation2012; Yang Citation2013) if current couplings do not provide beneficial outcomes. This includes de-prioritisation of specific investment attracting schemes. The regional industrial and research base should be supported by upgrading skills and capacities to enhance interaction with the relevant branch plant firms in the region. Finally, important lead firms in global value chains should be integrated into the design and implementation of place-based policies. These firms act as important boundary spanners (Wu Citation2021). The EDP of smart specialisation offers a good opportunity to include externally owned firms in regional innovation strategies and to bring them together with local actors.

In localised solitary regions, both the industrial structure and the research and education base are weak. Therefore, internal knowledge circulation is low, as is the integration into external knowledge flows (Trippl, Grillitsch, and Isaksen Citation2018). The absorption capacity of firms is low and these regions will often show characteristics of thin regions (Isaksen and Trippl Citation2016). However, the weakly developed industrial structure offers opportunities due to the absence of dominant incumbents resisting change and low levels of path dependency, thus facilitating experimentation (Baumgartinger-Seiringer et al. Citation2021). For MNCs, these regions are interesting locations to benefit from first-mover advantages (Mudambi and Santangelo Citation2016). Due to their peripherality, these regions are exposed to a constant outflow of the local workforce which generates diaspora networks. Returnees could provide an interesting development opportunity (Carvalho and Vale Citation2018; Saxenian Citation2007), but a constant brain-drain remains an issue. In addition, as the supporting infrastructure such as research institutes and universities are not sufficiently developed, attracting subsidiaries and branches of these organisations can be promising, fostering ripple effects such as spin-offs in the region (Isaksen and Trippl Citation2017) and bring new impulses and science-based knowledge to the region. Adoption of innovations from other places in the local context is considered a promising strategy (Capello and Lenzi Citation2013). In the past, policies in these types of regions have generated ‘cathedral in the desert’ phenomena when being too ambitious. Hence, smart specialisation strategies should pursue a hands-on approach since small-scale activities and the weak structures allow for more experimentation. These places can therefore act as test-bed regions for regional and non-regional actors. In the latter case, building on diaspora networks either by building connections to or by attracting returnees might be a sound strategy. Given that transnationally mobile entrepreneurs are a source of knowledge flow into regions (Saxenian Citation2005, Citation2007; Saxenian and Sabel, Citation2008), policy interventions that support their individual mobility and network building can form part of smart specialisation strategies. For example, Schäfer and Henn (Citation2018) report about German and British policy initiatives to bring Israeli entrepreneurs to Berlin and London, respectively, and Rohde, Warnecke, and Wloka (Citation2019) point to activities to connect the Ruhr region with Tel Aviv’s high-tech scene.

illustrates how smart specialisation policies can support favourable external connections according to knowledge circulation types of regions. Apart from these specific strategies, some general considerations can further inform regional policymaking under the umbrella of smart specialisation.

Table 2. An outward-looking smart specialisation approach.

5.2. Further implications for smart specialisation

When assessing regional strengths, weaknesses and potentials for innovation-based new path development, a focus on endogenous structures and internal connectivity is not enough but should be complemented by analyses of the region’s external connectedness. Such accounts should cover both the bright and the dark sides of external connectedness. While there is a growing awareness of the virtues of external connections, potential drawbacks tend to be overlooked in current discussions. The dark side (Phelps, Atienza, and Arias Citation2018) of external connectedness can manifest itself in various ways. Regions may be locked into unstainable path dependent inter-regional production and innovation networks (Martin and Sunley Citation2006; MacKinnon Citation2012) or may suffer from the outflow of firms, other organisations and individuals with potential negative effects on (new) path development in the region. Further, exogenous knowledge sources can affect the relationship between different paths and thus affect existing paths positively or negatively (Hassink, Isaksen, and Trippl Citation2019; Frangenheim, Trippl, and Chlebna Citation2020; Breul, Hulke, and Kalvelage Citation2021).

Another core issue relates to the inclusion of external actors such as MNCs in governance set-ups and their involvement in and contributions to the development of visions and the selection of policy priorities. While including them is important, problems of policy capture should be considered, notably if these actors are powerful (Hassink and Gong Citation2019; Benner Citation2020; Hassink and Kiese Citation2021).

Another cross-cutting issue in smart specialisation highlighted by Uyarra, Marzocchi, and Sorvik (Citation2018) is inter-regional policy collaboration. Regional policymakers can stimulate the inflow of knowledge ‘on their own’ or they could collaborate with policymakers from other regions and seize opportunities for mutual policy learning (Uyarra, Marzocchi, and Sorvik Citation2018). For example, policy partnerships such as twinnings between cities and regions (Liu and Hu Citation2018) can serve as a platform. As regional development agencies can act as knowledge gatekeepers (Morisson Citation2019), inter-regional policy collaboration can establish pipelines and diffuse knowledge gained from outside within the region. Inter-regional policy collaboration may take different forms and intensities, ranging from an exchange of information and experiences and sporadic collaboration to the implementation of mechanisms for longer-term policy coordination and the development of a joint innovation strategy (Nauwelaers Citation2014). The latter could include setting up joint education programmes and supporting the mobility of students and researchers, jointly attracting highly qualified people and promoting research or jointly establishing knowledge infrastructure (e.g. competence centres, technology parks and incubators) or promoting entrepreneurship (Nauwelaers Citation2014). However, active policy coordination is still in its infancy (Uyarra, Marzocchi, and Sorvik Citation2018).

6. Conclusions

In this article, we have argued that smart specialisation policies should combine place-specific factors and non-local knowledge sources to promote new regional industrial path development. The geography of knowledge flows has been a significant theme in economic geography and innovation studies over the past years. How these flows translate into new path development in regions remains poorly understood though. Our article has addressed this question, arguing that an outward-looking approach to smart specialisation should include the strategic development of a region’s external connectedness by following strategies adapted to specific types of regions. We sought to advance academic and policy debates on the external connectedness by outlining knowledge acquisition and circulation strategies for different region types.

Arguably, more scholarly work is needed to further develop an outward-looking smart specialisation approach. A key issue that should rank high on future research agendas is to unravel the relative importance of different types of non-local knowledge flows in different regional and industrial (technological) contexts. Further, a dynamic view on knowledge flows is crucial since one type of knowledge flow may well give rise to subsequent rounds of knowledge flows. For example, attracting firms, research organisations and individuals leads not only to the localisation of new knowledge but also to new networks with other regions. In the same vein, individuals who left the region provide opportunities to establish connections to firms or research institutes located in other places.

New path development stimulated or supported by exogenous sources can affect other paths in the region, in either positive or negative ways, as the emerging literature on inter-path relations (Hassink, Isaksen, and Trippl Citation2019; Frangenheim, Trippl, and Chlebna Citation2020; Breul, Hulke, and Kalvelage Citation2021) suggests. Further analysing the role of exogenous knowledge sources for inter-path relationships can build on this literature and could provide important conclusions for policymaking.

Another core issue relates to the involvement of non-local firms, research institutes, other organisations and individuals who enter the region in smart specialisation processes. While the inclusiveness of the EDP is a critical question (e.g. Benner Citation2014; Roman et al., Citation2020), little is known about these actors’ willingness and motivations for getting involved in inclusive governance setups. More research will be needed to elucidate under which conditions they can be new voices in such settings.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to two anonymous reviewers for their valuable and constructive comments on an earlier version of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agrawal, A., I. Cockburn, and J. McHale. 2006. “Gone but not Forgotten: Knowledge Flows, Labor Mobility, and Enduring Social Relationships.” Journal of Economic Geography 6 (5): 571–591. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbl016

- Ascani, A., L. Bettarelli, L. Resmini, and P. Balland. 2020. “Global Networks, Local Specialisation and Regional Patterns of Innovation.” Research Policy 49 (8): 104031. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2020.104031

- Aslesen, H., K. Hydle, and K. Wallevik. 2017. “Extra-regional Linkages Through MNCs in Organizationally Thick and Specialized RISs: A Source of New Path Development?” European Planning Studies 25 (3): 443–461. doi:10.1080/09654313.2016.1273322

- Baldwin, R. 2011. 21st century regionalism: Filling the gap between 21st century trade and 20th century trade rules, WTO Staff Working Paper, No. ERSD-2011-08, Geneva: World Trade Organization (WTO). https://doi.org/10.30875/c67646a3-en.

- Balland, P., and R. Boschma. 2021. “Complementary Interregional Linkages and Smart Specialisation: An Empirical Study on European Regions.” Regional Studies 55 (6): 1059–1070. doi:10.1080/00343404.2020.1861240

- Barca, F. 2009. An Agenda for a Reformed Cohesion Policy: A place-based approach to meeting European Union challenges and expectations. Brussels: European Communities.

- Barca, F., P. McCann, and A. Rodríguez-Pose. 2012. “The Case for Regional Development Intervention: Place-based Versus Place-Neutral Approaches.” Journal of Regional Science 52 (1): 134–152. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9787.2011.00756.x

- Barrientos, S., G. Gereffi, and A. Rossi. 2011. “Economic and Social Upgrading in Global Production Networks: A new Paradigm for a Changing World.” International Labour Review 150: 319–340. doi:10.1111/j.1564-913X.2011.00119.x

- Barzotto, M., C. Corradini, F. Fai, S. Labory, and P. Tomlinson. 2019. “Enhancing Innovative Capabilities in Lagging Regions: An Extra-Regional Collaborative Approach to RIS3.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 12 (2): 213–232. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsz003

- Bathelt, H., A. Malmberg, and P. Maskell. 2004. “Clusters and Knowledge: Local Buzz, Global Pipelines and the Process of Knowledge Creation.” Progress in Human Geography 28 (1): 31–56. doi:10.1191/0309132504ph469oa

- Baumgartinger-Seiringer, S., L. Fuenfschilling, J. Miörner, and M. Trippl. 2021. “Reconsidering Regional Structural Conditions for Industrial Renewal.” Regional Studies 56 (4): 579–591. doi:10.1080/00343404.2021.1984419.

- Bellandi, M., L. De Propris, and C. Vecciolini. 2021. “Effects of Learning, Unlearning and Forgetting on Path Development: The Case of the Macerata-Fermo Footwear Industrial Districts.” European Planning Studies 29: 259–276. doi:10.1080/09654313.2020.1745156

- Benner, M. 2014. “From Smart Specialisation to Smart Experimentation: Building a New Theoretical Framework for Regional Policy of the European Union.” Zeitschrift für Wirtschaftsgeographie 58 (1): 33–49. doi:10.1515/zfw.2014.0003

- Benner, M. 2020. “Six Additional Questions About Smart Specialization: Implications for Regional Innovation Policy 4.0.” European Planning Studies 28 (8): 1667–1684. doi:10.1080/09654313.2020.1764506

- Bergek, A., M. Hekkert, S. Jacobsson, J. Markard, B. Sandén, and B. Truffer. 2015. “Technological Innovation Systems in Contexts: Conceptualizing Contextual Structures and Interaction Dynamics.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 16: 51–64. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2015.07.003

- Binz, C., and B. Truffer. 2017. “Global Innovation Systems—A Conceptual Framework for Innovation Dynamics in Transnational Contexts.” Research Policy 46: 1284–1298. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2017.05.012

- Binz, C., B. Truffer, and L. Coenen. 2016. “Path Creation as a Process of Resource Alignment and Anchoring: Industry Formation for On-site Water Recycling in Beijing.” Economic Geography 92 (2): 172–200. doi:10.1080/00130095.2015.1103177

- Blažek, J. 2016. “Towards a Typology of Repositioning Strategies of GVC/GPN Suppliers: The Case of Functional Upgrading and Downgrading.” Journal of Economic Geography 16 (4): 849–869. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbv044

- Boschma, R. 2005. “Proximity and Innovation: A Critical Assessment.” Regional Studies 39 (1): 61–74. doi:10.1080/0034340052000320887

- Boschma, R. 2015. “Towards an Evolutionary Perspective on Regional Resilience.” Regional Studies 49 (5): 733–751. doi:10.1080/00343404.2014.959481

- Breul, M., C. Hulke, and L. Kalvelage. 2021. “Path Formation and Reformation: Studying the Variegated Consequences of Path Creation for Regional Development.” Economic Geography, 97 (3): 213–234. doi:10.1080/00130095.2021.1922277

- Bunnell, T., and N. Coe. 2001. “Spaces and Scales of Innovation.” Progress in Human Geography 25 (4): 569–589. doi:10.1191/030913201682688940

- Camagni, R., and R. Capello. 2013. “Regional Innovation Patterns and the EU Regional Policy Reform: Toward Smart Innovation Policies.” Growth and Change 44 (2): 355–389. doi:10.1111/grow.12012

- Capello, R., and C. Lenzi. 2013. “Territorial Patterns of Innovation and Economic Growth in European Regions.” Growth and Change 44 (2): 195–227. doi:10.1111/grow.12009

- Carvalho, L., and M. Vale. 2018. “Biotech by Bricolage? Agency, Institutional Relatedness and New Path Development in Peripheral Regions. Cambridge Journal of Regions.” Economy and Society 11 (2): 275–295. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsy009

- Chaminade, C., M. Bellandi, M. Plechero, and E. Santini. 2019. “Understanding Processes of Path Renewal and Creation in Thick Specialized Regional Innovation Systems.” Evidence from two Textile Districts in Italy and Sweden. European Planning Studies 27 (10): 1978–1994.

- Coe, N., and T. Bunnell. 2003. “‘Spatializing’ Knowledge Communities: Towards a Conceptualization of Transnational Innovation Networks.” Global Networks - A Journal of Transnational Affairs 3 (4): 437–456. doi:10.1111/1471-0374.00071

- Coe, N., P. Dicken, and M. Hess. 2008. “Global Production Networks: Realizing the Potential.” Journal of Economic Geography 8 (3): 271–295. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbn002

- Coe, N., M. Hess, H. Yeung, P. Dicken, and J. Henderson. 2004. “‘Globalizing’ Regional Development: A Global Production Networks Perspective.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 29: 468–484. doi:10.1111/j.0020-2754.2004.00142.x

- Coe, N., and H. Yeung. 2015. Global Production Networks: Theorizing Economic Development in an Interconnected World. First edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cohen, W., and D. Levinthal. 1990. “Absorptive Capacity: A New Perspective on Learning and Innovation.” Administrative Science Quarterly 35: 128–152. doi:10.2307/2393553

- Cooke, P. 2004. “Introduction: Regional Innovation Systems – An Evolutionary Approach.” In Regional Innovation Systems: The Role of Governances in a Globalized World, edited by P. Cooke, M. Heidenreich, and H.-J. Braczyk, 2nd ed., 1–18. London: UCL Press.

- Crescenzi, R., and S. Iammarino. 2017. “Global Investments and Regional Development Trajectories: The Missing Links.” Regional Studies 51 (1): 97–115. doi:10.1080/00343404.2016.1262016

- Crevoisier, O., and H. Jeannerat. 2009. “Territorial Knowledge Dynamics: From the Proximity Paradigm to Multi-Location Milieus.” European Planning Studies 17 (8): 1223–1241. doi:10.1080/09654310902978231

- Dahlström, M., and L. James. 2012. “Regional Policies for Knowledge Anchoring in European Regions.” European Planning Studies 20 (11): 1867–1887. doi:10.1080/09654313.2012.723425

- Elekes, Z., R. Boschma, and B. Lengyel. 2019. “Foreign-owned Firms as Agents of Structural Change in Regions.” Regional Studies 53 (11): 1603–1613. doi:10.1080/00343404.2019.1596254

- Ernst, D., and L. Kim. 2002a. “Global Production Networks, Information Technology and Knowledge Diffusion.” Industry and Innovation 9 (3): 147–153. doi:10.1080/1366271022000034435

- Ernst, D., and L. Kim. 2002b. “Global Production Networks, Knowledge Diffusion, and Local Capability Formation.” Research Policy 31: 1417–1429. doi:10.1016/S0048-7333(02)00072-0

- European Commission. 2014. “National/regional innovation strategies for smart specialisation.” Cohesion Policy fact sheet. DG Regio.

- Foray, D. 2014. “From Smart Specialisation to Smart Specialisation Policy.” European Journal of Innovation Management 17 (4): 492–507. doi:10.1108/EJIM-09-2014-0096

- Foray, D., P. David, and B. Hall. 2009. “Smart specialisation–the concept.” Knowledge economists policy brief, 9. European Commission.

- Foray, D., M. Eichler, and M. Keller. 2021. “Smart Specialization Strategies—Insights Gained from a Unique European Policy Experiment on Innovation and Industrial Policy Design.” Review of Evolutionary Political Economy 2 (1): 83–103. doi:10.1007/s43253-020-00026-z

- Foray, D., J. Goddard, X. Goenaga Beldarrain, M. Landabaso, P. McCann, K. Morgan, C. Nauwelaers, and R. Ortega-Argilés. 2012. Guide to Research and Innovation Strategies for Smart Specialization (RIS3). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the EU.

- Frangenheim, A., M. Trippl, and C. Chlebna. 2020. “Beyond the Single Path View: Interpath Dynamics in Regional Contexts.” Economic Geography 96 (1): 31–51. doi:10.1080/00130095.2019.1685378

- Frenken, K., and R. Boschma. 2007. “A Theoretical Framework for Evolutionary Economic Geography: Industrial Dynamics and Urban Growth as a Branching Process.” Journal of Economic Geography 7 (5): 635–649. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbm018

- Gereffi, G., J. Humphrey, and T. Sturgeon. 2005. “The Governance of Global Value Chains.” Review of International Political Economy 12 (1): 78–104. doi:10.1080/09692290500049805

- Giuliani, E. 2007. “The Selective Nature of Knowledge Networks in Clusters: Evidence from the Wine Industry.” Journal of Economic Geography 7: 139–168. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbl014

- Giuliani, E., and M. Bell. 2005. “The Micro-determinants of Meso-level Learning and Innovation: Evidence from a Chilean Wine Cluster.” Research Policy 34: 47–68. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2004.10.008

- Goddard, J., and P. Chatterton. 1999. “Regional Development Agencies and the Knowledge Economy: Harnessing the Potential of Universities.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 17: 685–699. doi:10.1068/c170685

- Grabher, G. 1993. “The Weakness of Strong Ties; the Lock-In of Regional Development in the Ruhr Area.” In The Embedded Firm: On the Socioeconomics of Industrial Networks, edited by G. Grabher, 255–277. London: Routledge.

- Grillitsch, M., B. Asheim, and M. Trippl. 2018. “Unrelated Knowledge Combinations: The Unexplored Potential for Regional Industrial Path Development. Cambridge Journal of Regions.” Economy and Society 11 (2): 257–274.

- Hassink, R. 2021. “Strategic Cluster Coupling.” In The Globalization of Regional Clusters: Between Localization and Internationalization. Cheltenham, edited by D. Fornahl and N. Grashof, 15–32. Northampton: Elgar.

- Hassink, R., and H. Gong. 2019. “Six Critical Questions About Smart Specialization.” European Planning Studies 27 (10): 2049–2065. doi:10.1080/09654313.2019.1650898

- Hassink, R., A. Isaksen, and M. Trippl. 2019. “Towards a Comprehensive Understanding of New Regional Industrial Path Development.” Regional Studies 53 (11): 1636–1645. doi:10.1080/00343404.2019.1566704

- Hassink, R., and M. Kiese. 2021. “Solving the Restructuring Problems of (Former) Old Industrial Regions with Smart Specialization? Conceptual Thoughts and Evidence from the Ruhr.” Review of Regional Research 41 (2): 131–155.

- Horner, R. 2014. “Strategic Decoupling, Recoupling and Global Production Networks: India’s Pharmaceutical Industry.” Journal of Economic Geography 14 (6): 1117–1140. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbt022

- Isaksen, A., and M. Trippl. 2016. “Path Development in Different Regional Innovation Systems: A Conceptual Analysis.” In Innovation Drivers and Regional Innovation Strategies, edited by M. D. Parilli, R. D. Fitjar, and A. Rodríguez-Pose, 66–84. London: Routledge.

- Isaksen, A., and M. Trippl. 2017. “Exogenously Led and Policy-Supported New Path Development in Peripheral Regions: Analytical and Synthetic Routes.” Economic Geography 93 (5): 436–457. doi:10.1080/00130095.2016.1154443

- Liu, X., and X. Hu. 2018. “Are ‘Sister Cities’ from ‘Sister Provinces’?” An Exploratory Study of Sister City Relations (SCRs) in China. Etworks and Spatial Economics 18 (3): 473–491.

- Lorenzen, M., and R. Mudambi. 2013. “Clusters, Connectivity and Catch-up: Bollywood and Bangalore in the Global Economy.” Journal of Economic Geography 13 (3): 501–534. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbs017

- MacKinnon, D. 2012. “Beyond Strategic Coupling: Reassessing the Firm-region Nexus in Global Production Networks.” Journal of Economic Geography 12 (1): 227–245. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbr009

- MacKinnon, D. 2013. “Strategic Coupling and Regional Development in Resource Economies: The Case of the Pilbara.” Australian Geographer 44 (3): 305–321. doi:10.1080/00049182.2013.817039

- MacKinnon, D., S. Dawley, A. Pike, and A. Cumbers. 2019. “Rethinking Path Creation: A Geographical Political Economy Approach.” Economic Geography 95: 113–135. doi:10.1080/00130095.2018.1498294

- Malecki, E. 2010. “Global Knowledge and Creativity: New Challenges for Firms and Regions.” Regional Studies 44 (8): 1033–1052. doi:10.1080/00343400903108676

- Markusen, A. 1996. “Sticky Places in Slippery Space: A Typology of Industrial Districts.” Economic Geography 72 (3): 293–313. doi:10.2307/144402

- Martin, R., and P. Sunley. 2006. “Path Dependence and Regional Economic Evolution.” Journal of Economic Geography 6 (4): 395–437. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbl012

- McCann, P., and R. Ortega-Argilés. 2015. “Smart Specialization, Regional Growth and Applications to European Union Cohesion Policy.” Regional Studies 49 (8): 1291–1302. doi:10.1080/00343404.2013.799769

- McCann, P., and R. Ortega-Argilés. 2016. “The Early Experience of Smart Specialization Implementation in EU Cohesion Policy.” European Planning Studies 24 (8): 1407–1427. doi:10.1080/09654313.2016.1166177

- Menzel, M., and D. Fornahl. 2010. “Cluster Life Cycles—Dimensions and Rationales of Cluster Evolution.” Industrial and Corporate Change 19 (1): 205–238. doi:10.1093/icc/dtp036

- Morisson, A. 2019. “Knowledge Gatekeepers and Path Development on the Knowledge Periphery: The Case of Ruta N in Medellin, Colombia.” Area Development and Policy 4: 98–115. doi:10.1080/23792949.2018.1538702

- Morrison, A. 2008. “Gatekeepers of Knowledge Within Industrial Districts: Who They are, How They Interact.” Regional Studies 42: 817–835. doi:10.1080/00343400701654178

- Morrison, A., R. Rabellotti, and L. Zirulia. 2013. “When Do Global Pipelines Enhance the Diffusion of Knowledge in Clusters?” Economic Geography 89 (1): 77–96. doi:10.1111/j.1944-8287.2012.01167.x

- Mudambi, R., and G. Santangelo. 2016. “From Shallow Resource Pools to Emerging Clusters: The Role of Multinational Enterprise Subsidiaries in Peripheral Areas.” Regional Studies 50 (12): 1965–1979. doi:10.1080/00343404.2014.985199

- Nauwelaers, C. 2014. “Smart specialisation strategies: the transfrontier challenge.” Presentation at the event: Smart Specialisation Strategies: Implementing European Partnerships. Committee of Regions – Brussels 18 June 2014.

- Neffke, F., M. Hartog, R. Boschma, and M. Henning. 2018. “Agents of Structural Change: The Role of Firms and Entrepreneurs in Regional Diversification.” Economic Geography 94 (1): 23–48. doi:10.1080/00130095.2017.1391691

- Njøs, R., L. Orre, and A. Fløysand. 2017. “Cluster Renewal and the Heterogeneity of Extra-regional Linkages: A Study of MNC Practices in a Subsea Petroleum Cluster. Regional Studies.” Regional Science 4 (1): 125–138. doi:10.1080/21681376.2017.1325330

- OECD. 2009a. How Regions Grow: Trends and Analysis. Paris: OECD.

- OECD. 2009b. Regions Matter: Economic Recovery, Innovation and Sustainable Growth. Paris: OECD.

- OECD. 2011. Regions and Innovation Policy. Paris: OECD.

- Oinas, P., M. Trippl, and M. Höyssä. 2018. “Regional Industrial Transformations in the Interconnected Global Economy.” Cambridge Journal of Regions Economy and Society 11 (2): 227–240. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsy015.

- Owen-Smith, J., and W. Powell. 2004. “Knowledge Networks as Channels and Conduits: The Effects of Spillovers in the Boston Biotechnology Community.” Organization Science 15 (1): 5–21. doi:10.1287/orsc.1030.0054

- Phelps, N., M. Atienza, and M. Arias. 2018. “An Invitation to the Dark Side of Economic Geography.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 50: 236–244. doi:10.1177/0308518X17739007

- Pietrobelli, C., and R. Rabellotti. 2009. “The Global Dimension of Innovation Systems: Linking Innovation Systems and Global Value Chains.” In Handbook of Innovation Systems and Developing Countries, edited by B.Å. Lundvall, K. J. Joseph, C. Chaminade and Jan Vang, 214 – 238. Cheltenham: Elgar.

- Radošević, S., and K. Ciampi Stancova. 2018. “Internationalising Smart Specialisation: Assessment and Issues in the Case of EU New Member States.” Journal of the Knowledge Economy 9 (1): 263–293. doi:10.1007/s13132-015-0339-3

- Rohde, S., C. Warnecke, and L. Wloka. 2019. “Brücke ins gelobte Land: Start-up-Ökosysteme im Ruhrgebiet und in Tel Aviv.” Standort 43: 92–99. doi:10.1007/s00548-019-00584-3

- Roman, M., H. Varga, V. Cvijanovic, and A. Reid. 2020. “Quadruple Helix Models for Sustainable Regional Innovation: Engaging and Facilitating Civil Society Participation.” Economies 8: 48. doi:10.3390/economies8020048

- Saxenian, A. 2005. “From Brain Drain to Brain Circulation: Transnational Communities and Regional Upgrading in India and China.” Studies in Comparative International Development 40 (2): 35–61. doi:10.1007/BF02686293

- Saxenian, A. 2007. The new Argonauts: Regional Advantage in a Global Economy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Saxenian, A., and C. Sabel. 2008. “The New Argonauts, Global Search, and Local Institution Building.” Economic Geography 84: 379–394. doi:10.1111/j.1944-8287.2008.00001.x

- Schäfer, S., and S. Henn. 2018. “The Evolution of Entrepreneurial Ecosystems and the Critical Role of Migrants. A Phase-model Based on a Study of IT Startups in the Greater Tel Aviv Area.” Cambridge Journal of Regions Economy and Society 11: 317–333. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsy013

- Smith, N. 1992. “Contours of a Spatialized Politics: Homeless Vehicles and the Production of Geographical Scale.” Social Text 33: 54–81. doi:10.2307/466434

- Swyngedouw, E. 2004. “Globalisation or ‘Glocalisation’? Networks, Territories and Rescaling.” Cambridge Review of International Affairs 17: 25–48. doi:10.1080/0955757042000203632

- Tödtling, F., and M. Trippl. 2013. “Transformation of regional innovation systems: From old legacies to new development paths. In Reframing Regional Development, edited by P. Cooke, 297–317. London: Routledge, 297–317.

- Trippl, M. 2013. “Scientific Mobility and Knowledge Transfer at the Interregional and Intraregional Level.” Regional Studies 47 (10): 1653–1667. doi:10.1080/00343404.2010.549119

- Trippl, M., M. Grillitsch, and A. Isaksen. 2018. “Exogenous Sources of Regional Industrial Change.” Progress in Human Geography 42 (5): 687–705. doi:10.1177/0309132517700982

- Trippl, M., E. Zukauskaite, and A. Healy. 2020. “Shaping Smart Specialization: The Role of Place-Specific Factors in Advanced, Intermediate and Less-Developed European Regions.” Regional Studies 54 (10): 1328–1340. doi:10.1080/00343404.2019.1582763

- Uyarra, E., C. Marzocchi, and J. Sorvik. 2018. “How Outward Looking is Smart Specialisation? Rationales, Drivers and Barriers” European Planning Studies 26 (12): 2344–2363. doi:10.1080/09654313.2018.1529146

- Wu, D. 2021. “Forging Connections: The Role of ‘Boundary Spanners’ in Globalising Clusters and Shaping Cluster Evolution.” Progress in Human Geography 46 (2): 484–506, doi:10.1177/03091325211038714.

- Yang, C. 2013. “From Strategic Coupling to Recoupling and Decoupling: Restructuring Global Production Networks and Regional Evolution in China.” European Planning Studies 21 (7): 1046–1063. doi:10.1080/09654313.2013.733852

- Yeung, H. 2009. “Transnationalizing Entrepreneurship: A Critical Agenda for Economic Geography.” Progress in Human Geography 33 (2): 210–235. doi:10.1177/0309132508096032

- Yeung, H. 2015. “Regional Development in the Global Economy: A Dynamic Perspective of Strategic Coupling in Global Production Networks.” Regional Science Policy & Practice 7 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1111/rsp3.12055

- Yeung, H. 2021. “Regional Worlds: From Related Variety in Regional Diversification to Strategic Coupling in Global Production Networks.” Regional Studies 55 (6): 989–1010. doi:10.1080/00343404.2020.1857719