ABSTRACT

In the last few years, chrono-urbanism has welcomed a novel perspective, namely, that of the 15-minute city concept, which has recently emerged in the present planning debate. During the current pandemic, this has coincided with a drive to highlight the importance of merging more activities in the neighbourhood to improve urban vitality and reduce daily commuting. In addition, increasing digitalization and knowledge-intensive activities have transformed the nature of work itself, thus affecting the choice of the workplace with new working spaces (NWS) emerging for collaborative and flexible work environments. Therefore, within this context, this study discusses recent chrono-urbanism approaches applied to urban planning and the role of NWS. The phenomenon is empirically examined in Oslo and Lisbon through a qualitative analysis of planning documents and a spatial analysis. The results show that most NWS are fairly accessible by public transport to users in both cities; although the NWS neighbourhoods in Lisbon have a greater diversity of functions compared to Oslo. However, in both cities, the distribution of NWS is non-uniform. This may limit residents’ choice to live and work (outside home) in the same neighbourhood. The study contributes to the current planning debate on new urban models for sustainable neighbourhoods.

1. Introduction

New urban models are currently being debated by planners and policy-makers as they aim to enable more sustainable, liveable and healthier cities post-COVID-19 by reducing air pollution, noise and heat island effects, as well as by increasing green space and physical activity (Nieuwenhuijsen Citation2021). In addition to superblocks, a low-traffic neighbourhood, car-free city and a mixture of these models (Nieuwenhuijsen Citation2021), the 15-minute city concept has gained greater momentum (Moreno et al. Citation2021). Living and working within a walking and biking distance can affect people’s habits and change mobility patterns, as well as the use of urban spaces, including non-traditional workplaces. However, from the planning perspective, little is known about the use of the 15-minute city and related concepts and the role of New Working Spaces (such as coworking spaces – CSs, and libraries which provide formal and informal spaces for working) in creating more sustainable and liveable neighbourhoods.

Prior to COVID-19, the increasing use of digital technologies, knowledge-intensive work and changes in the labour regimes have impacted the choice of the workplace (and related interdependence of residence and workplace) and mobility patterns (Samek Lodovici Citation2021). Cities are increasingly offering NWS to their residents (Reuschke and Ekinsmyth Citation2021). These NWS provide shared and flexible spaces, access to physical and digital services as well as opportunities for interaction and collaboration (Avdikos and Merkel Citation2020). They attract not only self-employed workers and entrepreneurs but also an increasing number of employees (whose tasks can be remotely performed) as well as corporate teams (Burchell, Reuschke, and Zhang Citation2021). For example, the localization of new working spaces (NWS), such as CSs, in the neighbourhood we live would reduce gas emissions and commuting distances (Ohnmacht, Z’Rotz, and Dang Citation2020). Thus, residents can choose flexible workplaces at a short distance from their homes, thus allowing them to reconcile work and private life. Although the long-term effects of the COVID-19 pandemic are not well known, several studies have shown an increase in remote-working, the use of more flexible workspaces and digital services (Franken et al. Citation2021). Therefore, in a post-pandemic scenario, NWS may grow due to many workers aiming to maintain more flexible working arrangements and avoid daily commuting, as well as a desire to retain high levels of productivity and achieve their work tasks (Ohnmacht, Z’Rotz, and Dang Citation2020).

In this context, the study aims to understand the possible effects of NWS in promoting the new urban sustainable model of a 15-minute city that considers the proximity (in terms of daily minutes of walking and cycling) and accessibility to a variety of urban functions including the non-traditional workplaces. Thus, this paper seeks to contribute to the current planning debate on working and living in the same neighbourhood, as well as future sustainable strategies for urban planning.

Oslo and Lisbon are selected considering that the official planners of both cities have embedded the new framework of the chrono-urbanism approach and related concepts including NWS in the new processes of urban densification, in comparison to other cities (see for example, London, Paris). Policy and planning documents from the two cases are used to analyze concepts and their argumentations Through the two case studies, the study explores the ways in which the 15-minute city concept and NWS are (or can be) applied in different urban contexts (see urban density and transportation networks). In addition, the article focuses on the ways NWS can be used as part of the planning policy and strategies for revitalizing both central and peripheral neighbourhoods. Comparisons between different local planning and socio-economic contexts across European cities are still limited. Although the results naturally cannot be generalized to all contexts, this study is an opportunity to discuss planning approaches that recognize the role of NWS which can, in turn, create flexible work opportunities in proximity to other urban functions, as well as analyze the space-temporal dimensions around NWS in different urban settlements.

Hence, the study addresses the following research questions: RQ1) How have Lisbon and Oslo embedded chrono-urbanism and related concepts as well as NWS in their city planning strategies? RQ2) What is the current degree of proximity and accessibility to urban functions in 15’ from those NWS?

In Section 2, the study first discusses the novel understanding of chrono-urbanism approaches and related concepts within the current planning debate and, secondly, the role of NWS in revitalizing neighbourhoods and supporting people’s work life. Section 3 presents the two cases of Oslo and Lisbon, and Section 4 introduces the methods used in the study. In Section 5, the paper shows the main outcomes from the analysis of strategic visions and planning approaches, including findings from the spatial analysis of NWS and their surroundings. Section 6 discusses the distribution of the NWS in the two cities, including the accessibility and proximity to urban functions (and the degree of diversity) in 15’ and 10’ from the NWS, related to the planning vision. Finally, Section 7 concludes by suggesting future studies and strategies.

2. Literature review

2.1. 15, 20 and 30-minute city concepts in the current planning debate

Since the end of the 1990s, chrono-urbanism has been acknowledged as one of the most influential time policies among several European cities (Osman, Ira, and Trojan Citation2020). The goal was to ensure equal access to public services and respond to inhabitants who have irregular everyday activities (Osman, Ira, and Trojan Citation2020 referring to Ascher Citation1997). This approach aimed to provide collective services that support local economic activities and individuals to develop spatio-temporal rhythms and configurations (Mulíček, Osman, and Seidenglanz Citation2014; Gwiazdzinski Citation2015; Osman, Ira, and Trojan Citation2020). The 15-minute and 20-minute city concepts follow the principle of chrono-urbanism while supporting the need for proximity-based approaches to better service urban areas and access to essential goods, services and well-being opportunities (Moreno et al. Citation2021; Guzman et al. Citation2021). During recent years, several cities have incorporated these new concepts in the city planning (see for example, 15-minute city concept in London, Paris, Milan, Shanghai and New York; 20’ concept in Sydney and Portland). The 15-minute city can transform a city into one which is experienced as more pleasant, healthy, and flexible (Nieuwenhuijsen Citation2021). Thus, developing multiple activities and functions, including workplaces, would improve urban liveability and reduce daily commuting as well as counteract any undesirable consequences of urban sprawl.

These planning discourses are linked to scholars’ arguments on compact city models and the characteristics of urban developments in suburban areas (Mouratidis Citation2018). Modern economies which are increasingly characterized by soft activities, knowledge economy and services led to high density and the development of mixed-use locations in our cities more than at any time in the past (Batty Citation2020). The assumption is ‘that more than one activity or function exists in the same location and/or at the same time, which only strictly holds if we consider a neighbourhood or time interval in which these activities exist together’ (Batty et al. Citation2004, 325). Compared to the past years, the new suburban sprawl is much more homogeneous than previous developed residential districts which were closer to the urban core (Batty Citation2021; Frenkel and Ashkenazi Citation2008). On one hand, there is the growth of residential areas, outside the city centres. This is caused by the search for more spacious dwellings in neighbourhoods promising better environmental quality and infrastructures regardless of any increased distance to the workplace (Howley, Scott, and Redmond Citation2009). On the other hand, the decentralization of companies, the development of business parks (adjacent to universities, hospitals and shopping malls), as well as secondary business districts in peripheries can create new centralities (Smętkowski, Moore-Cherry, and Celińska-Janowicz Citation2021). These planning approaches have often led to the development of new monofunctional districts in peripheral areas and increased dependence on private-car use (Smętkowski, Moore-Cherry, and Celińska-Janowicz Citation2021). However, people are now much more capable of organizing their working days around access to different uses and activities in time as well as space (Batty Citation2021). The development of NWS can become strategic in the peripheral areas and attract remote workers who prefer to commute less to urban cores (Babb, Curtis, and McLeod Citation2018). However, there is not yet a clear picture of the direction into and form in which cities might be transformed.

In this context, the 15-minute concept proposes an alternative way of approaching the development of the city by ‘(… .) bringing activities to the neighborhoods rather than people to activities (…)’ (Pozoukidou and Chatziyiannaki Citation2021, 22). Every neighbourhood should provide a variety of housing and workplaces as well as public spaces and services that enable more people to live closer to the neighbourhood (Nieuwenhuijsen Citation2021). For example, Moreno et al. (Citation2021) envisioned Paris stating that residents may enjoy a higher quality of life if they can fulfil the following six essential urban social functions in the space–time frame of 15’: (a) living, (b) working, (c) commerce, (d) healthcare, (e) education and (f) entertainment. In the 15-minute city, functions are mixed, enabling inhabitants to reach everything they need within a quarter of an hour on foot or by bicycle.

Prior to the COVID-19 period, the 20’ city concept was already acknowledged in the mobility policies of several cities, such as Melbourne, Portland, as well as Auckland and Bogota, and Liverpool (Calafiore et al. Citation2022). In addition to walking and cycling, the trip from home using public transport to required activities and urban functions is considered among the planners (Capasso Da Silva, King, and Lemar Citation2020) meaning that residents should locally access shops, health and community facilities, such as education, parks and playgrounds, as well as ideal employment, and all without using a private car (Mackness, White, and Barrett Citation2021). However, in this context, there are limited studies on workplaces. In the recent case of the Liverpool region studied by Calafiore et al. (Citation2022), the increase in work-at-home during the COVID-19 pandemic was acknowledged, but both the work amenities and NWS were neglected in the analysis. In contrast, the 30-minute city (e.g. Los Angeles) is an example of the cumulative opportunities concept of accessibility. This approach focuses on the variety of possible destinations (such as jobs, schools and stores) reachable within a given travel time of 30’by a certain mode and at a certain time of day (Levinson Citation2020).

The concepts mentioned above are based on the principles of proximity to urban functions (urban density and mixed-use), walkability (and biking) and accessibility (easy access to active and public transportation) (Nieuwenhuijsen Citation2021). Proximity refers to the location of people, services, and activities near one another and, consequently, the access to spatially distributed opportunities for residents’ interactions in their neighbourhoods (Diaz-Sarachaga Citation2021). Proximity is introduced in combination with urban density; mixed-use; and accessibility to jobs, through public transport or slow modes of transportation. More sustainable urban forms currently focus on the daily proximity trips in which the distance is measured by walking or cycling. Walkability can be conceptualized in several ways, such as ‘the extent to which characteristics of the built environment and land use may or may not be conductive to residents in the area walking for either leisure, exercise or recreation, to access services, or to travel to work’ (Leslie et al. Citation2007, 113). In addition, new multimodal and shared mobility services are promoted, for which a relatively dense and diversified urban structure is a precondition for their operation (Pajares et al. Citation2021).

However, several neighbourhoods are not yet prepared to offer adequate proximity to urban functions, including traditional and non-traditional workplaces. Thus, there is a risk that the 15-minute city concept may become rhetorical if it is not accompanied by policies and plans (Guzman et al. Citation2021). There is a need to further understand the services and spaces that cities currently provide as well as future functions that can contribute to the development of sustainable neighbourhoods (Guzman et al. Citation2021; Calafiore et al. Citation2022).

2.2. New working spaces for a new sustainable urban model

In the 15-minute city model, the workplace is one of the vital urban functions of the neighbourhood, in addition to other urban amenities (Pozoukidou and Chatziyiannaki Citation2021). New ways of working should focus on the combination of remote-working and coworking schemes as well as analyzing the practices of relocation of workplaces and co-location of organizations in the 15-minute neighbourhood (Moreno et al. Citation2021). In the case of Paris, this approach would require great flexibility from the local NWS in terms of time and space. This change would also assume new models of employment to be discussed with and among unions of workers and organizations. After the pandemic, large and centralized premises will probably move to more flexible and hybrid forms of working that will require a lighter presence of employees in the physical workspace (Moreno et al. Citation2021).

Under COVID-19, workplaces have become more varied in several countries. In addition to first and second homes, a European survey reported an increasing use of ‘various other locations’ across the European countries (Eurofound Citation2020). The increased use of ICTs can lead to new ways of working from peripheral districts and rural areas (Samek Lodovici Citation2021). However, prior to the pandemic several workers have already chosen to work remotely from CSs, public libraries or cafeterias rather than regularly travelling to their offices (López-Igual and Rodríguez-Modroño Citation2020; see multilocal studies in Di Marino, Lilius, and Lapintie Citation2019). CSs or other NWS in the neighbourhoods might help to overcome the social isolation and loneliness that working from home may cause as well as provide workspaces and fast IT connections. NWS may also support the re-design of neighbourhood and public services, as well as housing and mobility policies.

Lately, the business model of some coffee shops and restaurants has changed by offering new facilities, such as several spaces for working, meeting rooms, Wi-Fi, video for Skype-conferences and other facilities, in addition to coffee and food (Di Marino and Lapintie Citation2018). Additionally, public libraries have reinvented their spaces as networked hubs, community centres, innovation labs and makerspaces with facilities for artists and digital inventors (see examples in Australia and Canada) (Leorke and Wyatt Citation2019). Recently, public libraries have offered their residents several free spaces and services in which to work (Bouncken and Reuschl Citation2018; Di Marino et al. Citation2021; Weijs-Perrée et al. Citation2019). Furthermore, private and public organizations offer CSs as alternative spaces for work to their own employees in areas of the city which are more accessible (Di Marino et al. Citation2021). The NWS can also revitalize peripheral areas which are less dense and more car-oriented by attracting new workers both by public transport and private cars as well as by creating suburban models of NWS (Babb, Curtis, and McLeod Citation2018). This ‘scalable model’ should be considered relevant to the development of the outer-suburban neighbourhoods (Babb, Curtis, and McLeod Citation2018).

3. The two cases studies of Oslo and Lisbon

The two cities of Oslo and Lisbon are chosen as our case studies. The comparative study between Oslo and Lisbon provides an opportunity to analyze and compare the phenomenon of NWS, the 15-minute concept, and related notions. The two local contexts are not yet been investigated from the planning perspective. The outcomes from the comparison can contribute to rethinking the planning approach to functions and activities in the 15-minute neighbourhood, including the workplace, and considering future challenges post-pandemic.

Our first case study concerns the City of Oslo, which is the largest municipality of the Oslo Region consisting of 46 municipalities. Oslo municipality is populated by 697,010 inhabitants (Statistics Norway Citation2021). There has been a constant growth of the population through the high net of immigration and rather high fertility rate, resulting in the phenomenon of the aging population becoming less evident compared to other European countries (Statistics Norway Citation2021). Greater Oslo is predominantly monocentric with one dominant downtown area in which many jobs are concentrated. There is a limited number of second-order centres, while there are many local centres (Tiitu, Naess, and Ristimäki Citation2021). In addition, new housing construction has occurred as densification in the whole Oslo region. Suburban residents and employees in suburban workplaces tend to travel longer distances when commuting to Oslo (Tiitu, Naess, and Ristimäki Citation2021). Our second case study, Lisbon, is one of 18 municipalities in the Lisbon Metropolitan Area (LMA). Between 1981 and 2021, there was a progressive decrease in population, from 807,937 to 544,851 inhabitants, while adjacent municipalities increased their population and urban density (INE Citation2021). In addition to the aging of the population (which has particularly affected the inner-city centre and the western riverside area), the continuous process of tertiarization and decentralizing of economic activities and residential areas has contributed to urban sprawl and intense daily commuting (the number of commuters increases by more than 70% per day) (CML Citation2020; Louro, Marques da Costa, and Marques da Costa Citation2021).

Despite some differences in sociodemographic and economic conditions, as described, both cities intend to plan more sustainable neighbourhoods. Therefore, a good combination of urban functions and high accessibility (including soft-mode mobility) are recommended, including attractive connections with urban spaces and green areas. In this sense, the City of Oslo recently adopted the city of 10-minute (or nearby city) as a planning principle (Ministry of Local Government and Modernization, MLGM Citation2019). The development of such a model is not explicit in Lisbon’s strategic documents thus far. Instead, an urban development model has been proposed based on dense and multifunctional neighbourhoods, strengthened by a mobility network for the interconnection of different polarities (CML Citation2012), which fits within the new chrono-urbanism framework.

There is also an emerging debate about the NWS within the planning discourses. In Oslo, CSs are partially recognized in the planning strategies and can contribute to increasing innovation and creation by supporting a zero-emission society and more jobs (City of Oslo Citation2018). In Lisbon, the promotion of an entrepreneurial ecosystem (incubators, accelerators, CSs and makerspaces) is part of this strategic plan that aims to simultaneously foster both innovation and entrepreneurship as well as the regeneration of degraded and abandoned industrial areas (CML Citation2016).

To this end, CSs have recently proliferated in both cities, not only for independent workers but also for a wide variety of professionals, including employees who rent a desk in an open space or single office. In Oslo, CSs are for-profit and non-profit, while in Lisbon they are mainly for profit. The semi-public and public CSs are owned and managed by OsloMet and University of Oslo, and some informal CSs (including makerspaces) are provided by public libraries (see Deichman Bjørvika). Large private corporates manage several premises in the most strategic and accessible areas of the city. In addition, in Oslo, high-tech is the most dominant industry in which numerous CSs host incubators and start-ups have been rapidly growing, along with creative industries and less social innovation. The situation of CSs in Lisbon presents some contrasts. For example, many initially started spontaneously by gathering a small number of people to work together or for the incubation of start-ups. Currently, many CSs are managed by large corporations such as in Oslo. Several CSs are not limited to sharing office space but provide a range of spaces from workshops for artists to co-living solutions, among others; they occupy historical buildings (e.g. Liberdade 229) in prestigious areas of the city as well as old maritime containers and double-decker buses including the Village Underground. Both public and most non-profit CSs are linked to the municipality and are part of the urban revitalization processes (see Cowork Baldaya).

Furthermore, the study considers the rate of remote working in the two capitals (and national trends) before and after the pandemic. In Norway, 37% of people usually used to work remotely (9% as a permanent solution and 27% when necessary) (Nergaard et al. Citation2018), while in Portugal, only 6.5%. During the pandemic, the statistics reported an overall share of 39% in Norway (Holgersen, Jia, and Svenkerud Citation2021) and 15.6% in Portugal (Eurofound Citation2020). During the pandemic, in Oslo, it has been estimated that 43% of jobs have been carried out remotely from home (Holgersen, Jia, and Svenkerud Citation2021). Unlike in the Lisbon Metropolitan Area, in which 27.9% of the population have worked remotely (INE Citation2021). The remote workers are mainly highly specialized people in both cities. Despite the different figures, there is a higher concentration of flexible workers in the two capitals compared to other parts of the country. This may impact the use of NWS, the typical commuting (from home to office) and, more generally, living and working in the same neighbourhood.

4. Research methods and materials

The overall research design of the study is based on qualitative, quantitative and GIS-based analyses. A qualitative content analysis is used to explore the ways in which the two cities of Lisbon and Oslo address the chrono-urbanism approaches and related concepts as well as NWS in planning strategies. Spatial data analysis is used to examine the density of NWS in the urban districts as well as the diversity of urban functions that can be reached in 15-minute (and 10-minute) by walking from the existing NWS of the two cities.

4.1. Planning document analysis

The qualitative content analysis focused on the policy and planning documents of the cities of Oslo and Lisbon. The aim is to examine the differences and similarities between the planning approaches and the novel understanding of chrono-urbanism and related concepts, as well as the incorporation of NWS. Thus, we analyzed the contents of policy and planning documents coding the statements in texts and their frequencies (see ) (Bengtsson Citation2016). The qualitative content analysis focuses on the three selected categories: (1) novel approach to chrono-urbanism and related concepts, including implicit references; (2) acknowledgement of concepts basis for chrono-urbanism approach (such as walkability, proximity, accessibility and density); and (3) embedding of NWS in planning (such as the role of CSs, public libraries). These three categories were considered relevant themes to explore considering the findings from the literature review.

Table 1. Selected content analysis of the planning documents: Differences and similarities in approaching chrono-urbanism and related notions, as well as approach and role of NWS, and their frequencies.

For the qualitative content analysis, we have employed a number of selected planning documents providing long-term strategies, visions and objectives for the future development of the two cities as follows:

Network of Public Spaces. An idea Handbook (MLGM Citation2019). The handbook shows several planning criteria and tools for achieving the 10-minute or nearby town, reaching the UN Sustainable Development Goals and creating more attractive Norwegian municipalities. This programme was under the Nordic Council of Ministers involving 18 small- and medium-sized Nordic towns, including Oslo. The handbook also includes a summary of interesting, executed projects that have contributed to the development and new way of thinking about the 10-minute city concept.

Oslo Campus Strategy (City of Oslo Citation2020) is a strategic document developed by the city council that is acknowledged in the planning regulations and guidelines of the Oslo Master plan. The strategy identifies three innovation districts in the city, as well as institutions, stakeholders and NWS that can play a key-role. This strategy seeks to increase cultural functions, urban functions, and housing to create more attractive, liveable and sustainable districts. In order to fulfil these aims, the city has developed a car-free programme by investing in soft and shared mobility as well as public transport (City of Oslo Citation2019).

The Lisbon Master plan (CML Citation2012) developed by the Lisbon City Council is a strategic and regulatory planning document in line with national and regional policies and plans, which establishes a new strategic vision for the city structured around four major priorities: (i) affirming Lisbon in global and national networks; (ii) regenerating the consolidated city; (iii) promoting urban rehabilitation; and (iv) stimulating participation and improving the governance model.

The Strategic Urban Development Plan of Lisbon Municipality (SUDP_Lx) (CML Citation2016) is supported by the Lisbon Regional Operational Programme 2014–2020. The SUDP_Lx defines three prior interventions of: (1) attracting more inhabitants by providing affordable housing, parking for residents, creating a healthy urban environment and quality public facilities of proximity; (2) drawing more companies and jobs to the area by promoting business incubators and start-ups, as well as projects that reuse abandoned or vacant spaces; and (3) boosting urban rehabilitation of public spaces in conjunction with sustainable mobility (CML Citation2016).

4.2. Spatial data analysis

The study selected private and public CSs from the available databases on NWS of the two cities constructed by the authors. For the case of Oslo, we also considered those public libraries which provide formal and informal workspaces. At the time of writing, 57 CSs (private 37, public libraries 16, semi-private 1, public 3) are located in the city of Oslo, while in Lisbon, 105 CSs (all private, except two from the municipality; and five non-profit associations) were active.

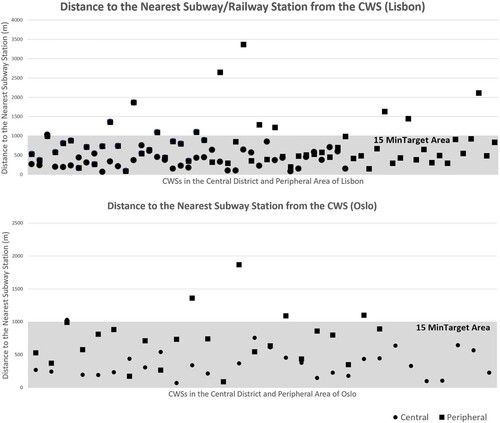

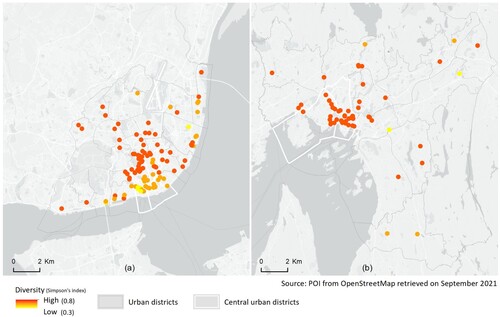

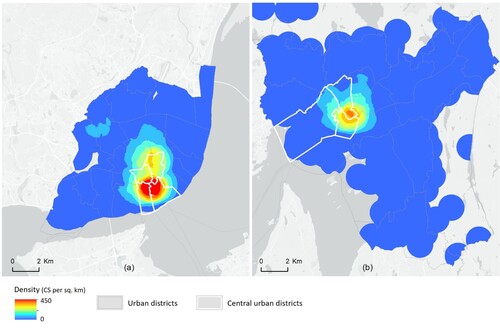

Spatial and statistical analysis supported by GIS tools are carried out to examine both the distribution of CSs within the urban districts (bydeler in Norway and freguesias in Portugal) of the cities of Oslo and Lisbon as well as the diversity of urban functions surrounding these CSs. To visualize the distribution of CSs in both cities (showing areas of greater or lesser concentration), heat maps are created. To understand the diversity of urban functions of the surrounding areas of the existing CSs, data are used from the OpenStreetMap road network and Points of Interest (POI) by September 2021. POI are classified into six main categories: public and private services, food and beverages services, retail trade, nature, leisure and sports, entertainment, arts and culture and transportation facilities. These constitute the urban functions under analysis. The surrounding areas of 15’ of the existing CSs were calculated considering travelling through the street network (instead of Euclidean distance) and based on a pedestrian speed of 4 km per hour. The diversity of urban functions (POI) is mapped and statistically analyzed. The Simpson's Diversity Index (Simpson Citation1949) is applied to the CSs allowing us to understand which ones are located in a more or less diverse neighbourhood. The results of the GIS-based and statistical analyses are presented in showing the density of CSs in Oslo and Lisbon as well as the diversity of the surrounding areas.

Figure 1. Density of existing CS in urban districts of Lisbon (a) and Oslo (b). Source: Tomaz et al., Citation2021.

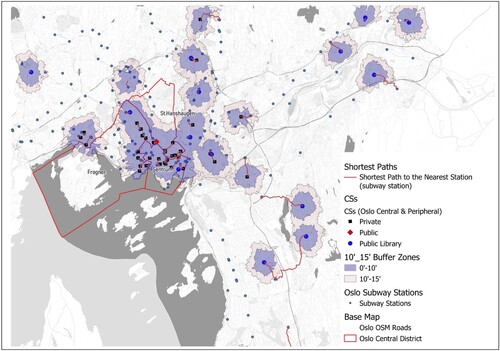

Figure 2. Accessibility of CSs to the nearest subways station within 10’ and 15’ walking distances Oslo.

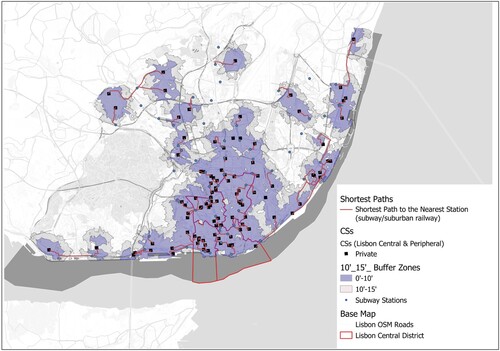

Figure 3. Accessibility of CSs to the nearest subways station within walking distances (10’ and 15’) Lisbon.

5. Results

5.1. Planning perspectives of Oslo and Lisbon

In the case of Oslo, the concept of a 10-minute town (also named as nearby town) is explicitly embedded in a national report (MLGM Citation2019). Thus, this principle is (or should be) adopted across all Norwegian cities. The 10-minute town is acknowledged as an everyday perspective on town and neighbourhoods, In the nearby town, the target points of everyday life (housing, school, kindergarten, businesses, jobs, leisure activities, public spaces and green spaces) can be reached within walking distance of 10’ (OCU, n = 6). In the city of Lisbon, the chrono-urbanism approach is implicitly embedded in the model of local development, which is based on a dense network of small neighbourhood centralities and a multifunctional planning approach that ‘brings the workplaces closer to the dwellings and fosters a neighbourhood experience of 24 hours a day, as well as increasing the residential attractiveness of Lisbon’ (CML, 22). In Oslo, the notion of a compact city is often mentioned as synonymous with the 10-minute or nearby town concept. Compact city centres are also seen as compact public developments that may have positive consequences on public life (OCU, n = 6). In Lisbon, urban densification is essential to the organization of a territory (LDEN, n = 2). The promotion of a compact city is associated with the creation of urban polarities, which correspond to ‘areas of the city with high accessibility by public transport, where land-use compact model and the location of more central urban functions is advocated, without compromising the multifunctionality of the urban fabric’ (CML Citation2012, 43) (LCU, n = 4). In addition, the creation of multifunctional districts and provision of several urban functions capable of boosting the local economy also means allocating spaces for public and private companies within the urban fabrics closer to residential units (LCUmult, n = 6). In connection with the urban regeneration strategy, the municipality has also sought to attract talents, companies and investors who consequently draw in new services and residents.

Referring to proximity, there is a great emphasis in Oslo on the proximity and access to different types of public spaces within one kilometre, that is, about a 10’ walk (OCUprox, n = 2). Although the workplace is considered part of the structural plan of the 10-minute city, there are limited tools and examples to reach this target point in a quotidian perspective. Similarly, Lisbon depicts a network of proximity that includes the creation of affordable housing supply as well as safe and healthy public spaces that are served by a sustainable mobility network. In addition, Lisbon’s strategy recognizes that proximity can also support several issues: the residential attractiveness of central areas, the social cohesion of disadvantaged areas and the location of workplaces (LCUprox, n = 2).

The principle of sustainable mobility in Oslo states that pedestrians and cyclists have the first priority, public transport the second and vehicles have third (OMOB, n = 2). The general aim is to connect overall regional and municipal structures, such as public transport, bike paths, lakes/river courses, green structure and recreational areas (MLGM Citation2019, 56). The promotion of sustainable mobility is a primary objective of the new Lisbon Master plan to ensure the quality of life for their residents. Notable stress is laid on multimodal mobility that combines different modes of transport in a daily journey as well as the construction of an extensive network of bike paths and inclusive walking route. On the one hand, this would protect the residential areas from the car traffic; on the other, it would support local experiences and improve the environment in the neighbourhoods (LMOB, n = 8).

Furthermore, in Oslo, the intentions behind ‘the planning of public space network are that everyday activities should be located within walking or biking distance’ (MLGM Citation2019, 32) (OWB, n = 24). The public spaces should be designed for different purposes and activities that are needed by residents and society and organized connections that promote local identity’ (MLGM Citation2019, 7) (OPS, n = 22). Similarly, in Lisbon, the rehabilitation of public spaces (LPS, n = 5) is connected with the building of equipment and green spaces of proximity within urban regeneration processes as well as the promotion of sustainable mobility infrastructures between the new urban polarities (i.e. Pedibus and Bilkebus, CML Citation2016, 24–25) (LWB, n = 8). In the 10-minute city concept of Oslo, the traditional workplace is mentioned within the large network of urban functions without any significant emphasis. Unlike Lisbon, there is a clearer statement about the need for a more homogeneous distribution of workspaces and the creation of new centralities that reduce displacements and encourage the use of soft modes of transport (CML Citation2012).

Additionally, in Oslo, the NWS are recognized within the three innovation districts of the city: Oslo Sentrum, Hovinbyen and around the districts of Gaustad, Blindern, Marienlyst and Majorstuen, in the north-eastern and north-western part of the city, respectively (City of Oslo Citation2020). The municipal strategies aim to render the three urban areas more multifunctional and attractive to actors, businesses and citizens as well as managers and users of NWS. New local cultural and recreational services, and housing as well as vibrant streets must be further developed (Oinn/entr, n = 12). In the strategy, the libraries are also considered as important meeting places for the local communities in establishing and strengthening networks among residents as well as disseminating research and knowledge (Olibr, n = 1). In Lisbon, the strengthening of the entrepreneurial ecosystem of the city supports a network of incubators, accelerators and CSs. Some CSs are located in converted buildings holding historical and cultural value as well as former degraded and abandoned industrial areas which have been (or are being) regenerated (Linn/entr, n = 5). The aim is to foster innovation and internationalization of the region's business base as well as enhance the city’s competitiveness, thus attracting business and talents. This is reinforced by the creation of conditions for strategic access to international markets, the existence of a competitive, qualified and flexible workforce, excellent quality of life, as well as modern structures and available spaces (CML Citation2016). The CSs can connect the community of entrepreneurs, professionals and creatives, and a growing number of digital nomads.

5.2. Results from the spatial analyses

The analysis of the distribution of the CSs within the urban districts of Oslo and Lisbon reveals that the central districts host 53% and 39%, respectively, of the total number of CSs of each city. shows the geographic concentration of these CSs in the central districts of both cities, albeit Lisbon reveals a relatively higher clustering in the central area. A short distance outside the city centre fringe zone, several districts of Lisbon include CSs, while they are more scattered in Oslo.

In Oslo, the majority of CSs are located in the central urban districts, namely Sentrum (which is characterized by high accessibility and functional mix, and a low number of residents), as well as Frogner (with a higher number of residents and St. Hanshaugen in which the two campuses of University of Oslo and Oslo Met University are located). These districts are among the most affluent areas of the city, although housing only 14% of the total number of city residents. Less CSs are located in Grünerløkka (a gentrified and creative district), Ullern (a wealthy and residential district) and Gamle Oslo (a multi-cultural district). Other public and private CSs are in more peripheral areas but are mainly located in multifunctional buildings, while some of them are placed in mono-functional science parks (in which Simula Lab and Start-up Lab are located).

Most of the CSs in Lisbon are located in the central urban districts (Santa Maria Maior, Misericódia, Arroios and Santo António) and along the central axis of the city (between Cais do Sodré and Campo Pequeno). These are historical and prime central business districts with a greater concentration of private and public offices, easily accessible by public transport, but with only 12% of the population of the city living therein. In addition, fewer CSs are located in more peripheral and residential areas, such as the urban districts of Belém or Lumiar. There is a representative number of CSs in Marvila and Beato urban districts, in which the riverfront axis has been the subject of urban rehabilitation interventions, attracting a wide range of occupiers (e.g. from the Central Business District) and from creative industries and technology companies due to the availability of more ample and affordable spaces.

The high concentration of CSs in the centre of Oslo and Lisbon is related to the higher concentration of jobs and proximity to other businesses. In Oslo, the relatively monocentric structure of the city has rendered the city centre very multifunctional and provides several public transport services. In Lisbon, although less monocentric, the multifunctionality and the diversity of public transport modes of the city centre heightens its attractiveness to the CSs.

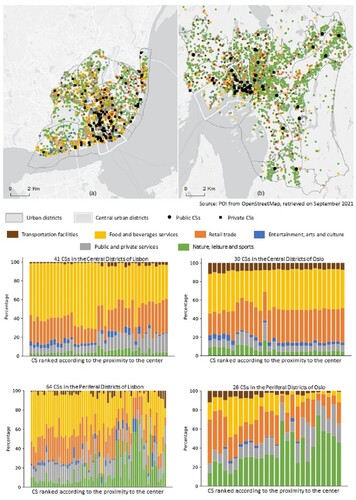

The degree of accessibility to public transport and proximity to other services are observed as important factors in the majority CSs, with some local variations. and demonstrates the accessibility of CSs to the nearest metro stops within walking distances, namely 10’ and 15’ calculated along the OpenStreetMap road network. 10’ walking distance is also considered because the Oslo city plan is addressing 15-minute city concept. Additionally, it provides a holistic view of the impacts of shifting to either a 10- or 15-minute city plan based on the results of a spatial analysis of the CSs locations. As can be seen, most of the CSs are located in the vicinity of the metro stops in both cities. In Oslo and in Lisbon, the majority (higher in Oslo) of CSs in peripheral districts are located within 15’ to the nearest metro stops ().

Additionally, and also shows the distribution of different types of CSs concerning ownership, including public and private CSs. As private and public CSs, and illustrates that the public libraries of Oslo serving as CSs (formal and informal) and maker spaces are located in areas providing immediate access to the metro and bus stops. This analysis was conducted considering that the different business models and the degree of proximity of urban functions might affect the CSs users and their choices to work in one or another CS.

illustrates the diversity of the classified POI and their distribution within city districts. Peripheral CSs are within the proximity of more diverse amenities and services in Lisbon than in Oslo, in which the semi-peripheral and peripheral public libraries benefit more from their proximity to green spaces rather than more diverse amenities and services. This analysis also corroborates the assertion that Oslo is more of a monocentric city, and that Lisbon has adopted in recent years a policy of promoting distributed centralities. The concentration of functions within the 15’ (from the CSs) is higher in Lisbon (81.8%) than Oslo (56.5%). The diversity of functions is similar among the two cities, except for green spaces (11% in Lisbon and 37% in Oslo) and food and beverage services (44% in Lisbon and 20% in Oslo). Most of the CSs are accessible by public transport; the public transport network is well developed in both central and peripheral districts, although in the western districts of Lisbon, there is a lack of subway stations.

projects the density and diversity of urban functions (POI) within 15’ walking distance of each individual CS. It is clear that in the central districts of Oslo, POI are distributed more evenly than those of Lisbon. For example, in the central district of Oslo, CSs are more accessible to ‘Transportation facilities’ than that of Lisbon. In addition, it is obvious that as we move from the central district towards peripheral districts in both cities, CSs are closer to ‘Nature, leisure, and sport’ services and infrastructures. Moreover, in the peripheral districts of Oslo, there is a lower density of ‘Food and beverages services’ by increasing distance from the centre. In contrast, the ‘Food and beverages services’ are evenly distributed.

Simpson's Diversity Index accounts for the number of POI present in the 15’ of each CS as well as the relative abundance of each category of POI. demonstrates the degree of diversity of POI for each individual CS in both Lisbon (a) and Oslo (b) within the 15’ area, both in central and peripheral urban districts. It can be interestingly seen that in the central district of Lisbon, the CSs do not benefit from a diverse neighbourhood as only specific POIs, namely ‘Food, beverages services’ and ‘Retail trade’ are more dominant than any other categories. Nevertheless, in the central districts of Oslo, the CSs are located in more diverse neighbourhoods concerning different categories of POI.

To conclude, the results show that the CSs are fairly accessible by public transport to co-workers and remote workers in both cities. However, the neighbourhoods of CSs in Lisbon are more diverse than in Oslo in which there are less services and amenities within a 15’ walking distance. These are important factors to consider for the development of sustainable and attractive neighbourhoods due to co-workers being traditionally attracted to urban amenities and proximity to other businesses. In both cities, the distribution of NWS is non-uniform, which limits the choice of residents to live and work (outside home) in the same neighbourhood.

6. Discussion

The outcomes from this study contribute to elaborating new planning strategies for sustainable 15-minute neighbourhoods which embed the emerging NWS in Oslo and Lisbon as other cities which present similar characteristics. The study also provides a comprehensive understanding of the concentration of NWS in the two cities (such as CSs and public libraries, which provide spaces for working), as well as degree of proximity and accessibility in 15 and 10’.

First, the findings show that the planning strategies of Oslo and Lisbon have recently embraced chrono-urbanism approaches and related concepts. To specify, an explicit concept of the 10-minute city or nearby town is used in Oslo, while in Lisbon, the development of multifunctional urban centralities implicitly incorporates concepts related to chrono-urbanism. Nonetheless, both cities aim to develop more sustainable neighbourhoods by embedding the concepts of proximity, walkability (and biking), as well as easy access to active and public transportation and green areas. These outcomes are in line with recent research on the 15-minute city concept (Moreno et al. Citation2021; Nieuwenhuijsen Citation2021; Calafiore et al. Citation2022). Furthermore, the discourses analyzed in the planning documents show that the chrono-urbanism approaches and related concepts are not used in a rhetorical way (Guzman et al. Citation2021). There is an awareness that there are currently limitations in effectively applying the 15-minute (or the 10-minute) city concept everywhere, but it is important to embed it in future sustainable urban developments.

Secondly, the study reveals that in both cities, planning orientations do not yet exist focusing on the use of CSs in the neighbourhood as alternative workplaces to the office (or in combination with the office and remote working) (Moreno et al. Citation2021). However, several references to the role of CSs in creating vibrant streets, a vital neighbourhood and/or buildings are found in the documents which address innovation and are used as a basis for current planning strategies. CSs, its users and managers can play a key role in further enlivening the districts after working hours.

Thirdly, similar to other cities, the CSs of Oslo and Lisbon are mainly located in very dense and diverse areas. Oslo is relatively monocentric with a limited number of sub-centres, whereas Lisbon is rather polycentric. This may explain the higher concentration of CSs in the centre of Oslo (see the higher degree of proximity to urban amenities and multi-modal public transports). This contrasts with Lisbon, where sub-centres are more multifunctional and accessible. Moreover, the peripheral CSs in Oslo are closer to green spaces but less served by urban amenities, but in the case of Lisbon, they enclose more ‘Food and beverage services’. However, the concentration of CSs in the peripheric areas is relatively low. Thus, it is possible to infer that they are not yet sufficiently attractive for opening CSs. The study also shows the current challenges of contemporary cities which present rather compact and mixed-use centres and relatively sprawled peripheries (Batty Citation2021), resulting in a different level of access to urban amenities by remote workers and co-workers in the neighbourhood. In addition to spatial and statistics analysis, this novel understanding of chrono-urbanism approach should be further investigated by focusing on individuals and their different spatio-temporal rhythms (Osman, Ira, and Trojan Citation2020) and everyday life needs (e.g. through surveys and interviews).

Another finding indicated that most of the CSs in Oslo and Lisbon are accessible by public transport as earlier discussed in the literature (Babb, Curtis, and McLeod Citation2018). In addition to the accessibility to public transport, it would be important for future studies to explore the reachability of NWS by soft and sharing mobility (e.g. bikes and electric scooters), which are considered among the main factors bringing benefits to people within the 15-minute city (Pajares et al. Citation2021).

Finally, during the Covid-19 pandemic, the ways of living, working and moving have substantially changed. In addition to alternative mobility patterns, such as walking or biking, we have further recognized the importance of open and green spaces for our well-being and physical and mental health. In this context, the dimension of proximity-based planning that has gained relevance with the pandemic will probably remain in the post-pandemic urban jargon (Moreno et al. Citation2021). Thus, considering the high digitalization and flexibility of working practices in the two cities (see Section 3), planners and other professionals should rethink the planning of both central and peripheral neighbourhoods having in mind NWS as with other functions.

7. Conclusions

The aim of this paper was to understand the possible contribution of NWS to promoting a new urban sustainable model of a 15-minute city. First, the study discussed the embedding of chrono-urbanism and related approaches in the planning strategies of Oslo and Lisbon. Secondly, the study provided a comprehensive analysis (qualitative and quantitative) of NWS phenomenon in the cities of Oslo and Lisbon. The study showed that both cities embrace a new urban sustainable model for neighbourhoods, while the role of the NWS is only partially acknowledged.

The type of documents and spatial analyses presented in the study have never been earlier conducted in the two cities. Moreover, similar studies are very limited in the literature and have not yet developed from the planning perspective. On the one hand, the comprehensive mapping and analysis of the existing NWS in the neighbourhoods reveals the limitations of some districts to adopt the 15-minute city concept (or 10-minute as the case of Oslo). On the other, it can suggest future strategies to the official planners of the two cities and other cities with similar characteristics when developing additional sub-centres, including workplaces after the pandemic.

Future studies on novel approaches to chrono-urbanism should include surveys and interviews of the users and managers of NWS in order to examine the positive and negative features of the neighbourhoods in which residents live and work (e.g. proximity, accessibility and walkability), as well as the reasons for working there. The study contributes to the current debate on liveable communities and long-term sustainable urban development, which has gained greater momentum during the pandemic.

Acknowledgements

This study is also based upon work from COST Action CA18214 ‘The geography of New Working Spaces and the impact on the periphery’ supported by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology) www.cost.eu

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ascher, F. 1997. “Du vivre en juste à temps au chrono-urbanisme.” Les Annales de la recherche urbaine 77 (1): 112–122. doi:10.3406/aru.1997.2145.

- Avdikos, V., and J. Merkel. 2020. “Supporting Open, Shared and Collaborative Workspaces and Hubs: Recent Transformations and Policy Implications.” Urban Research & Practice 13 (3): 348–357. doi:10.1080/17535069.2019.1674501.

- Babb, C., C. Curtis, and S. McLeod. 2018. “The Rise of Shared Work Spaces: A Disruption to Urban Planning Policy?” Urban Policy and Research 36 (4): 496–512. doi:10.1080/08111146.2018.1476230.

- Batty, M. 2021. “Science and Design in the age of COVID-19.” Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science 48 (1): 3–8. doi:10.1177/2399808321989131.

- Batty, M., E. Besussi, K. Maat, and J. J. Harts. 2004. “Representing Multifunctional Cities: Density and Diversity in Space and Time.” Built Environment 30 (4): 324–337. doi:10.2148/benv.30.4.324.57156.

- Bengtsson, M. 2016. “How to Plan and Perform a Qualitative Study Using Content Analysis.” NursingPlus Open 2: 8–14. doi:10.1016/j.npls.2016.01.001.

- Bouncken, R. B., and A. J. Reuschl. 2018. “Coworking-spaces: How a Phenomenon of the Sharing Economy Builds a Novel Trend for the Workplace and for Entrepreneurship.” Review of Managerial Science 12 (1): 317–334. doi:10.1007/s11846-016-0215-y.

- Burchell, B., D. Reuschke, and M. Zhang. 2021. “Spatial and Temporal Segmenting of Urban Workplaces: The Gendering of Multi-locational Working.” Urban Studies 58 (11): 2207–2232. doi:10.1177/0042098020903248.

- Calafiore, A., R. Dunning, A. Nurse, and A. Singleton. 2022. “The 20-Minute City: An Equity Analysis of Liverpool City Region.” Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 102: 103111. doi:10.1016/j.trd.2021.103111.

- Capasso Da Silva, D., D. A. King, and S. Lemar. 2020. “Accessibility in Practice: 20-Minute City as a Sustainability Planning Goal.” Sustainability 12 (1): 129. doi:10.3390/su12010129.

- City of Oslo. 2018. “Vår by, vår framtid. Kommuneplan for Oslo 2018.” Oslo kommune. https://www.oslo.kommune.no/politikk/sentrale-planer-og-styringsdokumenter/#gref

- City of Oslo. 2019. “The Car-free Livability Programme 2019.” https://daf9627eib4jq.cloudfront.net/app/uploads/2020/01/The-Car-free-Livability-Programme-2019.pdf

- City of Oslo. 2020. “Campus Oslo. Strategi for utvikling av kunnskapshovedstaden.” https://tjenester.oslo.kommune.no/ekstern/einnsyn-fillager/filtjeneste/fil?virksomhet=976819853&filnavn=vedlegg%2F2018_12%2F1281595_1_1.pdf

- CML. 2012. “Regulamento do Plano Director Municipal de Lisboa [Regulation of the Lisbon Municipality Master Plan]—PDM.” Câmara Municipal de Lisboa. https://www.lisboa.pt/fileadmin/download_center/normativas/regulamentos/urbanismo/Regulamento_PDM.pdf

- CML. 2016. “PEDU Lx—Plano Estratégico de Desenvolvimento Urbano do Município de Lisboa [The Strategic Urban Development Plan of Lisbon Municipality].” https://www.lisboa.pt/cidade/urbanismo/planeamento-urbano/teste-outros-estudos-e-planos/plano-estrategico-de-desenvolvimento-urbano

- CML. 2020. “Economia de Lisboa em Números 2020.” Câmara Municipal de Lisboa. https://www.lisboa.pt/fileadmin/atualidade/publicacoes_periodicas/economia/economia_lisboa_em_numeros_2020.pdf

- Di Marino, M., and K. Lapintie. 2018. “Exploring Multi-local Working: Challenges and Opportunies in Contemporary Cities.” International Planning Studies 25 (1): 1–21.

- Di Marino, M., J. Lilius, and K. Lapintie. 2018. “New Forms of Multi-local Working: Identifying Multi-locality in Planning as Well as Public and Private Organizations’ Strategies in the Helsinki Region.” European Planning Studies 26 (10): 2015–2035. doi:10.1080/09654313.2018.1504896.

- Di Marino M., A. Rehunen, M. Tiiu and K. Lapintie 2021. “New Working Spaces in the Helsinki Metropolitan Area: Understanding Location Factors and Implications for Planning.” European Planning Studies. doi:10.1080/09654313.2021.1945541

- Diaz-Sarachaga, J. M. 2021. “Linking Sustainable Urban Development With Town Planning Through Proximity Trade.” European Journal of Sustainable Development 10 (4): 121–121. doi:10.14207/ejsd.2021.v10n4p121.

- Eurofound. 2020. Living, Working and COVID-19 (COVID-19 Series). Luxemburg: Publications Office of the European Union. https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/sites/default/files/ef_publication/field_ef_document/ef20059en.pdf

- Franken, E., T. Bentley, A. Shafaei, B. Farr-Wharton, L. Onnis, and M. Omari. 2021. “Forced Flexibility and Remote Working: Opportunities and Challenges in the new Normal.” Journal of Management & Organization 26 (6): 1–19.

- Frenkel, A., and M. Ashkenazi. 2008. “Measuring Urban Sprawl: How Can We Deal with It?” Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 35 (1): 56–79. doi:10.1068/b32155.

- Guzman, L. A., J. Arellana, D. Oviedo, and C. A. Moncada Aristizábal. 2021. “COVID-19, Activity and Mobility Patterns in Bogotá. Are we Ready for a ‘15-Minute City’?” Travel Behaviour and Society 24: 245–256. doi:10.1016/j.tbs.2021.04.008.

- Gwiazdzinski, L. 2015. “The Urban Night: A Space Time for Innovation and Sustainable Development.” Articulo-Journal of Urban Research 11: 1–14. http://articulo.revues.org/3140 ISSN: 1661-4941

- Holgersen, H., Z. Jia, and S. Svenkerud. 2021. “Who and how Many Can Work from Home? Evidence from Task Descriptions” Journal for Labour Market Research 55 (1): 4. doi:10.1186/s12651-021-00287-z.

- Howley, P., M. Scott, and D. Redmond. 2009. “Sustainability Versus Liveability: An Investigation of Neighbourhood Satisfaction.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 52 (6): 847–864. doi:10.1080/09640560903083798.

- INE, Instituto Nacional de Estatística [Statistics of Portugal]. 2021. https://ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpgid=ine_main&xpid=INE

- Leorke, D., and D. Wyatt. 2019. Public Libraries in the Smart City. Singapore: Palgrave Pivot Singapore.

- Leslie, E., Coffee Neil, L. Frank, N. Owen, A. Bauman, and G. Hugo. 2007. “Walkability of Local Communities: Using Geographic Information Systems to Objectively Assess Relevant Environmental Attributes.” Health & Place 13: 111–122. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2005.11.001.

- Levinson, D. 2020. “The 30-Minute City.” Transfers Magazine, 5. https://transfersmagazine.org/magazine-article/issue-5/the-30-minute-city/

- Louro, A., N. Marques da Costa, and E. Marques da Costa. 2021. “From Livable Communities to Livable Metropolis: Challenges for Urban Mobility in Lisbon Metropolitan Area (Portugal).” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18 (7): 3525. doi:10.3390/ijerph18073525.

- López-Igual, P., and P. Rodríguez-Modroño. 2020. “Who is Teleworking and Where from? Exploring the Main Determinants of Telework in Europe.” Sustainability 12 (21): 8797.

- Mackness, K., I. White, and P. Barrett. 2021. “Towards the 20 Minute City.” Build 183: 71–72.

- Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation (MLGM). 2019. “Public Spaces—An idea handbook.” https://www.regjeringen.no/en/dokumenter/network-of-public-spaces—-an-idea-handbook/id2524971/

- Moreno, C., Z. Allam, D. Chabaud, C. Gall, and F. Pratlong. 2021. “Introducing the “15-Minute City”: Sustainability, Resilience and Place Identity in Future Post-pandemic Cities.” Smart Cities 4 (1): 93–111. doi:10.3390/smartcities4010006.

- Mouratidis, K. 2018. “Is Compact City Livable? The Impact of Compact Versus Sprawled Neighbourhoods on Neighbourhood Satisfaction.” Urban Studies 55 (11): 2408–2430. doi:10.1177/0042098017729109.

- Mulíček, O., R. Osman, and D. Seidenglanz. 2014. “Urban Rhythms: A Chronotopic Approach to Urban Timespace.” Time Soc 24: 304–325.

- Nergaard, K., R. K. Andersen, K. Alsos, and J. Oldervoll. 2018. “Fleksibel arbeidstid. En analyse av ordninger i norsk arbeidsliv (2018:15; Fafo Report).” https://www.fafo.no/images/pub/2018/20664.pdf

- Nieuwenhuijsen, M. J. 2021. “New Urban Models for More Sustainable, Liveable and Healthier Cities Post covid19; Reducing air Pollution, Noise and Heat Island Effects and Increasing Green Space and Physical Activity.” Environment International 157: 106850. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2021.106850.

- Ohnmacht, T., J. Z’Rotz, and L. Dang. 2020. “Relationships Between Coworking Spaces and CO2 Emissions in Work-related Commuting: First Empirical Insights for the Case of Switzerland with Regard to Urban-Rural Differences.” Environmental Research Communications 2 (12): 125004. doi:10.1088/2515-7620/abd33e.

- Osman, R., V. Ira, and J. Trojan. 2020. “A Tale of Two Cities: The Comparative Chrono-Urbanism of Brno and Bratislava Public Transport Systems.” Moravian Geographical Reports 28 (4): 269–282. doi:10.2478/mgr-2020-0020.

- Pajares, E., B. Büttner, U. Jehle, A. Nichols, and G. Wulfhorst. 2021. “Accessibility by Proximity: Addressing the Lack of Interactive Accessibility Instruments for Active Mobility.” Journal of Transport Geography 93: 103080. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2021.103080.

- Pozoukidou, G., and Z. Chatziyiannaki. 2021. “15-Minute City: Decomposing the New Urban Planning Eutopia.” Sustainability 13 (2): 928. doi:10.3390/su13020928.

- Reuschke, D., and C. Ekinsmyth. 2021. “New Spatialities of Work in the City.” Urban Studies 58 (11): 2177–2187. doi:10.1177/00420980211009174.

- Samek Lodovici, M. 2021. “The impact of teleworking and digital work on workers and society.” European Parliament. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2021/662904/IPOL_STU(2021)662904_EN.pdf

- Simpson, E. H. 1949. “Measurement of Diversity.” Nature 163 (4148): 688–688. doi:10.1038/163688a0.

- Smętkowski, M., N. Moore-Cherry, and D. Celińska-Janowicz. 2021. “Spatial Transformation, Public Policy and Metropolitan Governance: Secondary Business Districts in Dublin and Warsaw.” European Planning Studies 29 (7): 1331–1352. doi:10.1080/09654313.2020.1856346.

- Statistics Norway. 2021. “Population and land area in urban settlements.” SSB. https://www.ssb.no/en/befolkning/folketall/statistikk/tettsteders-befolkning-og-areal

- Tiitu, M., P. Naess, and M. Ristimäki. 2021. “The Urban Density in Two Nordic Capitals – Comparing the Development of Oslo and Helsinki Metropolitan Regions.” European Planning Studies 29 (6): 1092–1112. doi:10.1080/09654313.2020.1817865.

- Tomaz, E., and C. Henriques. 2021. “Georeferenced Database of Coworking Spaces in Lisbon Municipality (Version 1) [Data set].” Zenodo, doi:10.5281/zenodo.5105075.

- Weijs-Perrée, M., J. van de Koevering, R. Appel-Meulenbroek, and T. Arentze. 2019. “Analysing User Preferences for Co-working Space Characteristics.” Building Research & Information 47 (5): 534–548. doi:10.1080/09613218.2018.1463750.