ABSTRACT

This paper examines two atypical sparsely populated regions and their experience implementing a strategy of forest-based bioeconomy through smart specialization. Smart specialization is increasingly promoted as an opportunity for green transformations. Indeed, its recent evolution from S3 to S4 is an effort to address environmental sustainability challenges alongside regional development. In this paper, we argue that one of smart specialization’s early stages, the entrepreneurial discovery process (EDP), can help establish a basis for the green transformation of traditional industries located in sparsely populated areas. The EDP is a participatory process that gathers diverse actors interested in developing a common economic sector, mostly through innovation. We explain how multi-actor participation facilitate understanding innovation as a problem-solving process requiring the input of actors outside (but including) the firms. As the cases show, this can unlock the potential of place-based multi-actor interventions to identify and mobilize pre-existing conditions and resources that, when combined with a common agenda, can influence green path renewal. In our cases, those pre-existing conditions are a culture of collaboration, knowledge, infrastructure and access to natural resources. The common agenda is to transform the regional economy into a forest-based bioeconomy.

Introduction

The bioeconomy is part of a wider set of policies that aims for a green transformationFootnote1 of our economies. It is a policy realm striving for industry renewal, replacing fossil fuels and boosting economic growth. It is an important part of the European Union agenda and has been implemented in several regions (European Commission Citation2012, Citation2018; Fritsche et al. Citation2020). The bioeconomy covers all economic sectors and systems that rely on biological resources, animals, plants, microorganisms, or derived biomass, including organic waste (European Commission Citation2012). It encompasses primary economic activities like agriculture and forestry, and all industrial sectors that use biological resources, whether for processing food, energy or biotechnology. In this paper, we focus on the part of the bioeconomy that uses forest resources, also called forest-based bioeconomy.

The forest-based bioeconomy is a popular concept in northern Europe and in countries with a strong forest industry presence (Pülzl, Kleinschmit, and Arts Citation2014; Ramcilovic-Suominen and Pülzl Citation2018). It proposes to use biomass to replace fossil fuels, hence addressing climate change and stimulating economic growth, rural development and the modernization of the forest industry through innovation and technological development (Wolfslehner et al. Citation2016). The forest-based bioeconomy is also portrayed as a solution for rural unemployment and depopulation, conditions often found in sparsely populated areas (Pülzl et al. Citation2017; Hurmekoski et al. Citation2019), which are also regions of concern due to their supposed ‘lack of entrepreneurial capacities and the weakness of administrative capacities’ (Foray et al. Citation2012; Foray, Morgan, and Radosevic Citation2014).

The forest-based bioeconomy has been criticized for focusing on efficiency, productivity, and industrial competitiveness almost exclusively, while using sustainability as a selling point (Ramcilovic-Suominen and Pülzl Citation2018). Nevertheless, the bioeconomy has become an important part of the European Union’s environmental and economic agenda. It has the potential to impact sparsely populated regions, whose roles are often imagined as providers of forest biomass and containers for industrial path development (Morales and Sariego-Kluge Citation2021).

By looking at how a forest-based bioeconomy has been implemented through smart specialization and evolving towards S4 in Värmland (Sweden) and Finnish Lapland (Finland), two atypical and sparsely populated regions,Footnote2 this paper analyses the opportunities presented by the entrepreneurial discovery process (EDP) for green path renewal (Trippl et al. Citation2020). The question we address is: how does the EDP influence green path renewal? The case studies show that the EDP facilitates understanding innovation as a problem-solving process requiring the input of actors outside (but including) the firms. This can unlock the potential of place-based multi-actor interventions to identify and mobilize pre-existing conditions and resources that, when combined with a common agenda, can influence green path renewal in sparsely populated areas. Those pre-existing conditions include a strong culture of collaboration, knowledge, infrastructure and access to natural resources. When combined with a common agenda (a shared imagination of the forest-based bioeconomy), the institutional challenges that can prevent green path renewal in sparsely populated regions can be addressed.

We expect to contribute to advancing our understanding of how place-based innovation policies influence regional development, in this case, understood as green industrial development and modernization. This is an area of special concern to evolutionary economic geography, researchers and practitioners in the areas of sustainable development, regional studies and innovation studies. The paper begins by defining and contextualizing green path renewal, emphasizing the role of pre-existing conditions and imagined futures, followed by an explanation of smart specialization and the EDP. The following section describes the methods and data used for the analysis. The results and discussion section explain what and how the EDP identified and mobilized resources that are crucial for green path renewal, while creating a common agenda over an imagined future. Some conclusions are provided in the final section.

Green path renewal, innovation and the EDP

Path development and green path renewal

Path development is a key concept for understanding why certain industries and economic activities emerge in certain places and not others (e.g. Martin and Sunley Citation2006; MacKinnon Citation2008; Isaksen and Jakobsen Citation2017; Hassink, Isaksen, and Trippl Citation2019). It is commonly used to explain regional economic success and, in turn, regional failure to adapt to changing economic environments due to historically developed institutions, skills and industrial structure (Martin and Sunley Citation2006). Thus, regional economic and institutional evolution is one key to explain path development.

Another key to explain path development is the availability of knowledge and skills. Path development also responds to the availability of knowledge and skills in related industries in a region (Boschma and Wenting Citation2007). That knowledge can be combined with regional or extra-regional actors to enable innovation (Boschma et al. Citation2011).

Expectations and visions are another key to explaining path development, because of their ability to influence path development’s directionality. Besides historically developed institutions and industrial structure, knowledge and skills, path development is product of the activities and interactions of multiple actors. It is a place-dependent process where firms, policymakers, universities and local authorities participate, and whose collective expectations and imaginations influence decision-making (Tödtling and Trippl Citation2018; Hassink, Isaksen, and Trippl Citation2019). To summarize, path development is a process influenced by regional economic and institutional evolution, collective imaginations and knowledge availability and circulation.

Path development takes diverse forms: path creation, diversification, renewal, importation, upgrading, extension, exhaustion, and decline (Martin and Sunley Citation2006; Tödtling and Trippl Citation2013; Isaksen Citation2015; Grillitsch and Hansen Citation2019; Isaksen et al. Citation2019). Herein, path renewal is especially relevant. Often defined as a change in the path’s direction based on new technological development, knowledge, or innovations (Tödtling and Trippl Citation2013; Hassink, Isaksen, and Trippl Citation2019), it involves the growth of new activities via regional branching and the combination of knowledge and skills, as well as related or unrelated diversification (Isaksen and Jakobsen Citation2017).

In relation to green transformations and transformative change (see Coenen, Hansen, and Rekers Citation2015; Casula Citation2022), green path renewal has gained attention. It refers to intra-path changes in established industries, led by the adoption or development of environmentally friendly (or at least less harmful) technologies or practices, in an attempt to reconcile economic growth with sustainable development (Grillitsch and Hansen Citation2019; Trippl et al. Citation2020). Examples of green path renewal include industrial diversification to transform brown industries into green industries (Grillitsch and Trippl Citation2018), or branching towards technologically related sectors (Tödtling et al. Citation2014).

Innovation and smart specialization in green path renewal

Green path renewal and innovation go hand in hand. Innovation is needed to create or diversify economic activities and propose greener solutions, which will ultimately drive green transformations. Innovation as a concept has a long history of multidisciplinary contributions that cannot be addressed here (see Coenen and Morgan Citation2020), thus, we briefly refer to Regional Innovation Systems (RISs) literature because of its geographical focus. RIS approaches innovation as an iterative process where knowledge and new technologies are created and disseminated (Etzkowitz and Leydesdorff Citation2000; Doloreux and Parto Citation2005; Iammarino Citation2005). An important contribution of RIS literature is the acknowledgment of innovation as a process that concerns diverse actors from multiple scales (Cooke Citation2007, Citation2010). It is argued that innovation has the ability to unlock regional development, although mostly measured in creation of jobs and economic growth (Marques and Morgan Citation2021). Here, elements that are relevant for green path renewal are also relevant for innovation. For example, skills, knowledge and infrastructure, sometimes referred to as hard elements of the RISs, are as relevant as other soft elements such as informal institutions that facilitate collaboration (Sandulli, Gimenez-Fernandez, and Rodriguez Ferradas Citation2021).

Notwithstanding the contributions of RIS literature, there is a persistent focus on economic growth that appears insufficient to address societal challenges such as climate change. This has been already identified in recent contributions, which appeal for an approach where innovation is valued because of its capacity to solve problems and not for its capacity to produce growth (Truffer and Coenen Citation2012; Coenen and Morgan Citation2020).

Innovation has been the focus of several public policies, being smart specialization the most prevalent in the framework of the European Union. Smart specialization is a regional innovation agenda that emphasizes on collaborations between firms, universities and governments to realize regional priorities, needs and assets (Foray et al. Citation2012). Despite its place-based intent, it has been criticized for continue to hold traditional views on innovation, whilst the label ‘specialisation’ can deflect goals of diversification of regional economies (Capello and Kroll Citation2016; Cooke Citation2016). However, the new smart specialization programme (S4) links smart specialization with policies to address broader regional societal challenges such as sustainable development (McCann and Soete, Citation2020). Whether the inclusion of sustainable development is sufficient to shift how innovation is understood and sought remains to be seen. Yet, smart specialization has already been used by some European regions to implement sustainable development strategies, as the regions we are investigating here. With S4, it is expectable that more regions will modify their strategies to include sustainability goals.

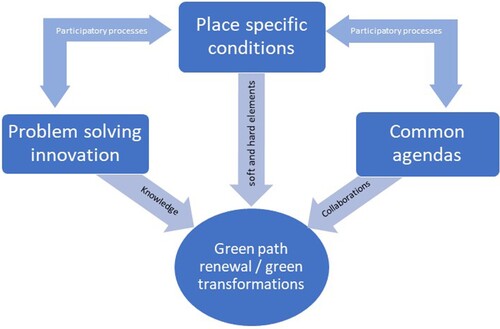

The changes in S4 relate to what Coenen and Morgan (Citation2020) had identified as a ‘socio-ecological’ model of innovation within smart specialization (5). It refers to innovation that meets human needs and ecological challenges, and where social innovation and civil society actors are essential. This understanding of innovation requires investing in collective learning and collective knowledge dissemination. It also requires enhancing place specificities to facilitate common agendas (Sotarauta and Suvinen Citation2019), where participatory processes can play an important role.

Green path renewal and the EDP

As noted by Gianelle et al. (Citation2020), smart specialization implies selecting specialization areas after ‘an interactive process between policy makers and the private sector, the so-called entrepreneurial discovery process’ (EDP) (1378; italics in original). The EDP serves to identify the regional conditions, assets and potentials, while building a common agenda about where to focus resources and efforts (Pugh Citation2018). It determines a ‘direction of travel’ and helps to coordinate efforts, but risks becoming inflexible, especially when funding depends on staying on a pre-determined path (Nieth et al. Citation2018). In relation to green transformations, Veldhuizen (Citation2020) identify two additional challenges. First, the EDP’s susceptibility to focus on measurable deliverables rather than social empowerment and learning. Second, the EDP’s vulnerability to be captured by vested interests and rent seeking behaviours.

The EDP is a participatory process led by the regional authorities, a role that is not easily fulfilled. It requires large efforts and institutional capacities that may be lacking in certain sparsely populated regions. The regional authorities are expected to lead, coordinate and articulate actors and interventions with different interests (Veldhuizen Citation2020). They are also expected to drive the EDP, articulate and maintain multi-actor agreements, guarantee inclusive governance systems, and take informed decisions on where and how to invest human and financial resources (Morgan, Citation2017; Morgan & Marques, Citation2019; Pugh, Citation2014).

The EDP builds over and looks for strengthening existing networks amongst relevant regional actors (Ranga Citation2018). Therefore, it is facilitated by an existing culture of collaboration. However, despite the ambition of having representation of relevant regional actors, Aranguren et al. (Citation2019) found that civil society and firm involvement in the EDP tends to be scarce.

Although the link between smart specialization and green transformations has been identified, more research is needed to better understand how place-based innovation policies influence regional development, in this case, understood as green industrial development and modernization. This is because place-specific approaches have not only been advocated for in geography and regional studies, but now also by international policies. The most recent IPCC report emphasizes the role of regional approaches to adaptation and mitigation of climate change (IPCC Citation2022), while policies like smart specialization and the Green Deal (in the European context), link innovation, renewal and sustainability.

To summarize, our analytical framework gathers the elements that previous research and theoretical development have identified as key to explaining green path renewal. In our framework, such elements are connected through participatory processes, being such connections are the mechanism influencing green path renewal (see ).

Methods

To answer the research question, how does the EDP influence green path renewal, we use the case studies of Finish Lapland (Finland) and Värmland (Sweden). The analyses included quantitative data on the socio-economic context surrounding these cases, but it mostly relied on qualitative data, since we needed to unpack the processes of implementing smart specialization highlighting the experiences of the actors involved. The data were obtained from several sources (see Appendix 1). First, semi-structured interviews were conducted in situ during March and April 2019 in Lapland, and online during October 2020 and May 2021, complemented by conversations and follow-up research dissemination pieces (Morales, Citation2020a,Citationb). The interviewees included representatives of the regional councils, private organizations participating in the bioeconomy and smart specialization, research centres, universities and business start-ups. The interview questions referred to the rationales, strategies, challenges and opportunities of smart specialization and the forest-based bioeconomy. Second, participant observation and informal conversations during meetings, workshops and conferences with practitioners. These served to gain a deeper understanding about the implementation of the bioeconomy and smart specialization. Secondary data was obtained from websites and policy reports from the European Union, national policies, research organizations, national and regional public and private research centres.

We focused on sparsely populated because of the expectations placed on them by the bioeconomy and smart specialization (economic growth and creation of jobs). The cases were selected because of their prompt inclusion of smart specialization (in early 2015), where the forest-based bioeconomy is a top area of specialization. Thus, these regions have a longer trajectory and more data available than others when studying smart specialization in green transformations. These regions also share a long economic and industrial history in the forest industry, and a longstanding cultural attachment to the forests, making them suitable to analyse processes of path renewal.

Värmland and Finnish Lapland are classified as sparsely populated areas (Finnish Lapland has the lowest population density in the EU). They also rank above the European average for institutional capacities and innovation (EC, Citation2019), making them ‘atypical’ sparsely populated regions. Since the aim of this paper is to advance the debate about placed-based innovation policies on green path renewal, studying these atypical regions allowed us to go beyond debates of institutional capacities, to explore other conditions influencing green path renewal. Yet, whether atypical or not, sparsely populated regions also warrant a closer examination because the challenges they face are quite distinct from regions (often urban) with high institutional capacities and thickness.

There is a relevant methodological caveat to raise in relation to one of the authors’ positionality. The empirical material was gathered by two researchers, one of whom has been, for around ten years, engaged in research and interaction with key actors in the RIS in Värmland (and more widely within the Nordic countries). Hence a part of the data was collected by this researcher while being involved in developing the smart specialization strategy in Värmland. This involvement includes taking part in workshops, commenting on the strategy’s draft and encouraging the inclusion of quadruple helix actors, assisting to meetings, interviews and conferences with actors from the forest industry, cluster organizations, the regional authorities, other researchers and civil society actors such as Non-Governmental Organizations. The other part of the material was gathered by the second researcher who oversaw the research design, fieldwork, and data collection for a research project carried out from January 2019 until February 2021. Although the data collected can appear, after these caveats, somewhat imbalanced, the material that supports this paper has been systematically selected to make sure that both cases contribute to answer the research question. In particular, we conducted more interviews in Lapland than in Värmland, as a manner to balance the availability of qualitative primary data, and used the same or similar type of secondary data for each case (see Appendix 1).

Results

The forest bioeconomy in smart specialization ‘á la Värmland’

Värmland county, located in western Sweden and bordering on Norway, has approximately 282,000 inhabitants, a population density of 16 inhabitants per km2, and about 70% of its area covered in forest. The capital city is Karlstad, with 94,000 inhabitants (in 2021). Värmland’s economic history is heavily influenced by the forestry sector; mainly sawmills, paper and pulp and related engineering. From a multiplicity of mills in the nineteenth century, Värmland’s forest industry now has fewer and larger mills (including several global firms) and firms in related activities that are identified as a forest-based bioeconomy (Jolly, Grillitsch, and Hansen Citation2020). These related activities include packaging materials, tissue paper, machinery, cross-laminated timber and consultancy services (Region Värmland Citation2015). Employment in the forest-based bioeconomy is estimated at 13,500–15,000 employees (SCB Kontigo Citation2018).

Goals of green growth were already part of Värmland’s smart specialization strategy before S4 came to replace S3 in the European Union new programming period (Dahlström and Hermelin Citation2022). Smart specialization is understood as a way to organize and develop existing regional assets to create value and sustainable economic development, with the forest bioeconomy as one of the specialization areas (Region Värmland Citation2015, Citation2021). The forest-based bioeconomy was already an established and growing sector when the smart specialization strategy emerged, making its inclusion as a priority rather straightforward (Interview Citation1, Karlstad 2020).

Aside from the firms and regional authorities (Region Värmland), the main regional actors in the forest-based bioeconomy are the cluster organization Paper Province and Karlstad University. In 2012, this triple helix partnership (with some other local and regional authorities) resulted in a successful bid for €13 million of external funding by the Swedish Innovation Agency Vinnova (Kempton Citation2015; Jolly, Grillitsch, and Hansen Citation2020). The initiative, titled Paper Province 2.0, aimed to develop Värmland as a leading node for the forest-based bioeconomy.

Apart from the funding committed by Vinnova, the regional council has invested approximately €4 million in 59 related projects between 2015 and 2020 (Interview Citation2, Karlstad 2020), while some of the largest firms and mills have made significant financial investments to build plants while greening and increasing production. For example, a new production line for cross-laminated timber for construction costing approximately €45 million (Stora Enso Citation2019), or the new state-of-the-art board-making machine at the Billerud Korsnäs plant costing approximately €700 million (Paper Province Citation2019). Although these corporate decisions cannot be attributed to the smart specialization strategy, the long-term commitment with implementing a forest-based bioeconomy and the council’s regional branding efforts played a role in these decisions.

Region Värmland and Karlstad University have long collaborated to strengthen the connections between the clusters and the education system and research, improve regional branding and increase the visibility and participation of the region in decision-making processes both nationally and at the EU level (Kempton Citation2015; Jolly, Grillitsch, and Hansen Citation2020). From 2010 to 2014, Region Värmland and Karlstad University had an agreement to co-finance research and innovation with funding of approximately €10 million. The flagship programme was the so-called ‘10 Professors Program’, for which eight professors were hired to serve as both academics and links between the innovation needs of the industry and the research and education programmes in the university (Kempton Citation2015). From 2016 to 2020, Region Värmland and Karlstad University had another agreement called ‘the Academy for Smart Specialisation’, with co-funding of approximately €10 million. This was a funding platform for research, innovation, debate, and exchange between researchers and other RIS actors. By November 2020, the Academy had generated research funding for a further €31 million and has been described as key to new industrial path development (Jolly, Grillitsch, and Hansen Citation2020), contributing to research and innovation goals within both the public and private sectors (OECD Citation2020).

In terms of promoting entrepreneurship and inter-firm collaborations, Värmland has several test beds located in firms and at Karlstad University (Dahlström and Hermelin Citation2022). Examples include LignoCity, which focuses on the commercialization of processes and products made with ligninFootnote3 (LignoCity Citation2021), and Packaging Greenhouse, which allows national and international companies to test new packaging-related products and services.

The forest bioeconomy in ‘Arctic smartness’

Bordering Sweden, Norway, Russia and the Baltic Sea, Finnish Lapland is the northernmost region of Finland. It has a population density of 2 inhabitants per km2 and its capital city, Rovaniemi, has approximately 63,000 inhabitants. Finnish Lapland holds 25% of Finland’s forested areas, of which half are state-owned (Viitanen and Mutanen Citation2018; Interview Citation3, Rovaniemi 2019). Forestry in this region dates from the nineteenth century and, alongside the steel and tourism industries, remains core to the regional economy. The forest industry has evolved from a few sawmills at the end of the nineteenth century (Ahvenainen Citation1990), to become a more diversified and efficient industry. It has secured large private investments to transform mills into biorefineries, including an approved plan to build the largest biorefinery in the Northern hemisphere. Investments in this plant amount to €1.6 billion, 40% financed by domestic equity and 60% by public and private debt (Matthis Citation2021).

The core of Lapland’s forest-based bioeconomy lies in the pulp and paper industry, timber and wood production. The aim is to continue growing in the production of biomaterials, biochemicals, soil improvement substances, biogas and biorefineries (Lapland University of Applied Sciences Lapin Amk Citation2019). The industry employs 3500 people and has a €1.7 billion economic output, largely from pulp and paper, representing 12% of the regional economy (Regional Council of Lapland, Citationno date). Forests have been a central part of Finnish Lapland’s culture and lifestyle; the forest industry coexists with reindeer husbandry, tourism and conservation.

In Lapland, the bioeconomy is a regional policy contained in the smart specialization programme Arctic Smartness, which promotes collaborations between the regional council, universities and research centres. As Värmland, Arctic Smartness already contained strategies for green growth and sustainable development before S4. Arctic smartness is a priority for regional development and an important tool for place branding.

Arctic Smartness organizes the areas of specialization in clusters, with two of the five areas prioritized being relevant for the forest-based bioeconomy: The Arctic Smart Rural Cluster (hereafter rural cluster), and the Arctic Industry and Circular Economy (hereafter industrial cluster). The rural cluster targets rural inhabitants, entrepreneurs and SMEs. It is managed through collaboration between the regional council and Proagria, a cooperative organization integrated by rural communities and entrepreneurs with a national presence and regional branches. The rural cluster conceptualizes the bioeconomy as the entrepreneurial activities carried out by rural inhabitants. From this perspective, rural businesses in Lapland have been always practising the bioeconomy, as they already work with agriculture and forest products. The concern is not how to change production systems but to ensure the survival of rural businesses and villages, promote rural development and wellbeing. Their activities are oriented to support rural businesses (small and family businesses mostly), while advocating for decentralized energy systems and local food production.

On the other hand, the industrial cluster targets the larger economic actors in the region (steel and forestry), and SMEs linked to them. It conceptualizes the bioeconomy as the activities carried out by larger industries (interview 10). The cluster is hosted at Digipolis OY, a technological centre located in the Kemi-Tornio sub region (southwest, frontier with northern Sweden). The industrial cluster aims to promote innovation and collaboration, circular solutions to industrial production to find ‘eco-innovative-ways to modernise production, manage by-products and by-processes’, and entrepreneurship and sustainability (Interview Citation4, Rovaniemi). In other words, the concern is that the arctic industry’s production systems are circular and more efficient while more actors can create businesses by taking advantage of side streams produced by forestry.

The EDP in Värmland and Lapland

In both regions, the EDP was carried out through a series of meetings, workshops and agreements amongst diverse regional actors including regional universities, research and innovation centres, the public sector (regional council, administrative board, and municipalities), the chamber of commerce, industrial actors, private organizations such as Paper Province (Värmland), Digipolis and Proagria (Lapland), and an array of local and global firms. Värmland focused on markets and entrepreneurship, trying to reach solutions to wider societal challenges and developing categories of specialization. In contrast, Lapland decided on three main themes: refining natural resources, use of Arctic conditions, and innovation for growth (Mäenpää and Teräs Citation2018). For both regions, the decision to include the forest-based bioeconomy as an area of specialization was rather straightforward, since this was an established and growing sector, and a strong mobilizer of regional economic development (in terms of jobs and revenue).

In Värmland, the EDP acknowledged a series of advantages and weaknesses to advance the areas of specialization. Advantages include an existing culture of collaboration between the university and private sector and within the private sector itself, which was already organized in clusters and networks (Dahlström and Hermelin Citation2022). Other advantages were the strength of the RIS and the high position of Sweden and Värmland in the European innovation scores. In terms of weaknesses, the EDP highlighted the low output of the RIS (measured by the number of new businesses and start-ups), the high costs of innovation, the lack of a skilled workforce, and an unbalanced business community (Region Värmland Citation2015).

Lapland’s EDP highlighted regional strengths like natural resources, potential for innovation, and entrepreneurship despite a ‘lack of critical mass’ (Interview Citation4, Rovaniemi 2019) and a strong RIS. The EDP also pointed out the fragility of Lapland’s ecosystem and the need for sustainable use of natural resources. It concluded that efforts were needed to promote the creation of spin-offs and new firms related to the regional economy’s core areas. The strategies include funding plans to increase firms’ innovation capacities, promoting efficient use of the existing R&D infrastructure, promoting collaborations among diverse actors, and organizing the prioritized areas in a ‘modern cluster approach’ (Interviews Citation4 and Citation5, Rovaniemi 2019) ().

Table 1. Summary of results.

Discussion – the EDP and green path renewal

The EDP is an iterative and participatory process amongst regional actors. It aims to identify the conditions, assets and potentials for path renewal, innovation and economic growth. EDP is the name given to this participatory process within smart specialization, yet we aim to highlight that, whether it is called EDP or has another name, participatory processes for planning and decision-making that gather a diversity of actors (beyond the firms), are crucial to recognize the nature of innovation beyond economic growth. The EDP is a participatory process that mobilizes knowledge from actors outside (but including) the firms, unlocking the potential of place-based strategies to influence green path renewal.

The cases show that place-specific conditions such as a strong culture of collaboration, knowledge, infrastructure and access to natural resources, combined with a shared agenda (the forest-based bioeconomy), counterweight the institutional constrains that can limit green path renewal. Place-specific constrains include lack of critical mass (stated by the interviewees to refer to number of qualified actors able to enter the RIS), overspecialization and strong dependences on one or few industries, smaller budgets for regional authorities, and rules that limit fund sourcing from the European Union (interviews, Paulsson Citation2019). The cases show that these constrains are counterweighted by the mobilization of resources and collaborations, identified and promoted through participatory processes. Thus, soft elements of the RISs are equally important as hard elements of the RISs to compensate for institutional constrains preventing green path renewal.

Innovation, resources and preconditions influencing green path renewal

The innovation process of the industry is pretty obvious, but we also have and account for social entrepreneurship and innovation, and these come from a different channel. (Interview Citation7, Rovaniemi 2019)

Conversations and exchanges facilitated by the EDP served to recognize innovation as a process where diverse actors, including the state and civil society, are needed. As the quote above shows, innovation is conceptualized as both technological development and social innovation that can enhance social capital (see also Coenen and Morgan Citation2020). The first conceptualization, innovation as technological development, often passes as an unquestioned goal for green growth via industrial modernization and technological advancement. The second conceptualization is stressed when innovation is seen as a participatory process that mobilizes knowledge from actors outside the firms.

[the regional council in the smart specialisation strategy] we have two main roles. One is understanding the policy (…) The other is to engage with the actors within the innovation system and transform the knowledge we have and the knowledge they have (…) it is a co-creation role. (Interview Citation2, Karlstad 2020)

What is compelling about these cases’ approach is their focus on innovation as a social process that values practices within the public sector and beyond large industries. Around the forest industry, collaborations between the universities or research centres, industry and the public sector have existed since before smart specialization in both regions. However, in their role as leaders of the smart specialization strategy, regional authorities are making efforts to communicate, inform and engage citizens and the civil society, in what is often called a quadruple helix collaboration. An example is the project Climate Smart Innovation (2015–2019), a partnership between Region Värmland and Paper Province. The project consisted of a series of workshops with civil society representatives from different municipalities, where ideas for projects that could contribute to a sustainable bioeconomy were discussed (Nordfeldt and Dahlström, Citationforthcoming). Despite the efforts, the actual materialization of the quadruple helix approach has proven difficult to grasp. Civil society’s role in the forest bioeconomy regions remains unclear in both regions. As one of the interviewees said, the quadruple helix approach ‘sounds interesting in theory but we have not understood how to apply it’ (Interview Citation6, Rovaniemi 2019). It is interesting that a civil society organization has highlighted the difficulty in operationalizing the quadruple helix concept.

Focusing on innovation as a participatory solving-problem process, soft resources such as culture of collaboration and place specificities become as significant as other hard conditions like infrastructure and knowledge to promote green path renewal. Regarding an existing culture of collaboration, informal institutions that build trust have played key roles during the EDP and smart specialization in Värmland and Lapland. Formal and informal institutions influence trust, collaboration and effective communication, all of which are relevant for developing a successful EDP (Rodríguez-Pose and Wilkie Citation2017). The demographic conditions have enabled collaborations and exchange between different actors, whether they belong to the public or private sector (or both at the same time), facilitating agreements towards a common agenda. On the other hand, strategic collaborations needed for implementing a forest-based bioeconomy were made with well-established organizations (Proagria, Digipolis, Paper Province), which in turn have strong pre-existing relationships with the target population, facilitating innovative strategies to be applied (Morales and Sariego-Kluge Citation2021). The EDP in both regions showed that pre-existing collaborations were key for smart specialization, and that developing such relationships depends on long-term commitment.

Regarding the existence and mobilization of knowledge, it is known that firms’ knowledge and skills play a crucial role in influencing path development (see Boschma and Wenting Citation2007; Boschma et al. Citation2011). The cases show that collaborations built around smart specialization helped mobilize that knowledge. Both regions have several programmes to create spaces for interaction and exchange between firms and entrepreneurs. The aim is to promote innovation and entrepreneurship, through the creation of spin-off companies and new firms transforming forest resources, or providing different services related to the forest bioeconomy.

The cases also show that firms’ knowledge is only part of the knowledge that can influence green path renewal. Expertise and information regarding the forest industry, forest uses, as well as sustainability and economic growth needs and potentials are also important. Knowledge in forest management is an example. This might be very particular to these cases, yet it is central to discussions surrounding sustainability. Research shows that sustainable use of forest biomass needs to be assessed using stricter measurement than the actual harvest-growth rate (e.g. Nordström et al. Citation2016; Zhang et al. Citation2020). This type of knowledge can lead to innovation that achieves sustainable goals, though not necessarily growth and profit.

Regarding the localized sustainable and economic growth needs and potentials, it is key to highlight the role of civil society. Civil society participation shows localized needs for sustainable solutions (regional sustainability needs change according to the urban and rural contexts). It also helps unpacking knowledge to address those needs. The EDP can help to access and unlock knowledge from different actors, and to pinpoint the needs and challenges that innovation is expected to solve. Indeed, including the civil society is crucial to understand the sustainability challenges faced by inhabitants of sparsely populated areas:

The challenge with the distances, for example, [there is much said about] cities but here villages are too far away … when you live in cities it is easier, the energy is cheaper, you don’t need your own car for transportation, and so on … for farmers, food and energy are big issues. Right now, farming is not profitable. (Interview Citation6, Rovaniemi 2019)

Although larger economic actors continue to have a dominant role within the forest-based bioeconomy, the participatory nature of the EDP helps to account for a wider diversity of concerns and interests:

The villagers’ concerns about the future and the survival of the village motivated them to join meetings and discussions. The possible transition from fossil-based energy to self-produced bioenergy has also opened business opportunities for them. (Timonen et al. Citation2018, 6)

Finally, infrastructure and access to raw materials are existing conditions used by regional authorities to enhance collaborations and make the regions attractive for private investment. As mentioned, both regions focused their smart specialization efforts on areas related to their most powerful industrial and economic actors. The rationale was to harness the entrepreneurial potential within strong and established sectors, taking advantage of existing natural resources, industrial infrastructure, and ‘supply of equipment and knowledge, research facilities both private and public, and a strong stand to move from fossil products to renewable products’ (Interview Citation1, Karlstad 2020).

Attracting private investments was part of a regional branding process that showcased both regions as forest-based bioeconomy leaders, thus making them attractive for ‘the industries to be here and to be sustainable here’ (Interview Citation2, Karlstad 2020). Although the governments in both regions have made important financial investments and have sought external funding (e.g. national innovation agencies, the EU), the most important investments came from the private sector. Indeed, a significant part of Region Värmland’s role has been to attract private investment by promoting the existing industrial infrastructure, easy access to raw material, relatively low-cost production for the Nordic countries, subsidies for energy, lower wages and what one of the interviewees called a loyal workforce. On the other hand, Lapland showcases itself as an attractive region in which industries can invest by highlighting its access to forest biomass, existing infrastructure, flexible labour conditions based on collective agreements, and existing international markets. A significant example of private investment is the agreement reached with Metsä Group to build the largest mill in the Northern hemisphere. Such agreement exceeded the regional council’s competence and capabilities is beyond its financial commitments and required the Finnish government to allocate funding to improve the transport network and infrastructure to support mill operations. This also raises questions about power imbalances between large corporate actors and regional authorities of sparsely populated regions (this, however, which opens a new stream for research that we cannot address in this paperFootnote4).

As noted, pre-existing conditions such as skills, knowledge, and infrastructure shape green path renewal, and those can be identified through participatory process such as the EDP. However, because green path renewal is a process in which multiple actors with diverse interests participate, collective expectations, visions and an imagined future become crucial for decision-making (Hassink, Isaksen, and Trippl Citation2019). The following sections emphasize this final point.

The EDP and formalization of future imaginations

The forest-based bioeconomy proposes a route for economic growth in rural areas: replacing fossil fuels with forest biomass to address climate change while stimulating economic growth, rural development and the modernization of the forest industry. These narratives endorse imagined futures which are translated into strategies and institutional arrangements, pledging for bringing a solution to rural unemployment, industrial development and depopulation (Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry of Finland Citation2014; European Commission Citation2018).

As stated by one interviewee, the importance of visions and imagined futures was acknowledged in past regional innovation strategies. However, with smart specialization, the regional authorities are leading the realization of those visions and are given more tools to create a common agenda (Interview Citation8, Karlstad 2020). Indeed, those visions did not come into existence with smart specialization or the EDP, the forest-based bioeconomy had been established in both regions long before. However, the EDP served to articulate otherwise isolated or unconnected efforts, gathering them under the same expectations and a common language to facilitate communication and collaboration.

One of the concerns expressed by researchers about the EDP is its potential to become inflexible, to fix the efforts in pre-determined goals that are not revisited (Nieth et al. Citation2018). The cases show that participatory processes to address green path renewal cannot be applied once and then exhausted; creating a common agenda that pinpoints areas for diversification does not end with the EDP. The rural cluster targets entrepreneurs, agriculture producers, the municipalities, and villages. A large part of their effort is put on disseminating information and gathering feedback from villages and rural entrepreneurs. The forest-based bioeconomy, in this context, is not so much about a transformation or industrial diversification but about providing adequate support for entrepreneurs who already use forest biomass as a means for income, which requires constant support and adjustment of the strategies. Similarly, the industrial cluster promotes innovation and collaboration to find ‘eco-innovative-ways to modernise production, manage by-products and by-processes and promote entrepreneurship and sustainability’ (Interview Citation4, Rovaniemi 2019). Their concern is that the Arctic industry’s production systems are circular and more efficient, and that other actors can create businesses by taking advantage of side streams. This also requires building over existing networks, as much as a constant effort to find new partners and redefine goals. As for Värmland, the longstanding collaborations between the RIS actors show that revisiting goals and strategies is key to successfully implement a forest bioeconomy (OECD Citation2020).

In sum, the EDP has served to formalize a common agenda resulting in agreements, collaborations and projects that determine investments, innovation directionality and decision-making, influencing green path renewal.

Conclusion

To answer the research question, how does the EDP influence green path renewal? This paper analysed two similar regions implementing a forest-based bioeconomy agenda through smart specialization. These cases demonstrate that recognizing innovation as a participatory and problem-solving process that mobilizes knowledge from actors outside (but including) the firms, unlocks the potential of place-based multi-actor interventions to influence green path renewal. It also allows identifying and mobilizing resources that counterweigh institutional constrains such as lack of critical mass, overspecialization and strong dependences on one or few industries, regional authorities with smaller budgets and limitations to raise European funds. The cases show that the EDP has served as a mechanism to mobilize pre-existing conditions that, combined with a common agenda (a forest-based bioeconomy), green path renewal is facilitated.

Pre-existing conditions such as infrastructure, access to natural resources and a strong culture of collaboration are crucial not only to formalize a shared imagined future but to achieve long-term commitments that exceed the smart specialization framework. Indeed, most of the actions and investments that determine innovation and path renewal achieved in these regions (which are still in progress), exceed the EDP and smart specialization. However, the policy support that smart specialization implies provides regional authorities with spaces and tools to build common agendas, reach multi-actor agreements, mobilize key resources and attract new funding.

The cases show that the EDP, or rather the processes to define, learn and design forest-based bioeconomy policy, are not bound to specific timeframes. Agreements and discussions among different actors, as well as new projects, strategies and investments occur throughout the policy implementation and are not limited to an EDP timeframe.

We identify two limitations to this research. First, is not having engaged with power imbalances between the actors participating in the EDP. The forest-based bioeconomy is embedded in uneven power relations, and powerful corporate interests could determine the use of natural resources in geographically remote rural areas and co-opt the bioeconomy narratives, as indeed seen in both Finland (Ahlqvist and Sirviö Citation2019) and Sweden (Holmgren et al. Citation2022). It is uncertain, yet highly unlikely, that the EDP or participatory processes alone are an effective strategy to counterweight those power imbalances and avoid smart specialization to favour incumbent and powerful actors disproportionately. Second, having focused on atypical sparsely populated regions, potential problems such as an inability to deliver on the expectations that smart specialization sets on regional authorities, due to lack of training or capacities, escaped our analysis.

Appendix.pdf

Download PDF (79.1 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Though green transformation is itself a contested notion, in this paper it is taken as the transition from fossil fuels to a biomass-based economy.

2 Atypical in the sense of ranking above the European Union average in institutional and innovation capacities.

3 A wood component present in all plants; this is the ‘glue’ that bonds cellulose and fibres and contributes to the strength of the tree (LignoCity Citation2021).

4 A further research question would address the issues of power relations and imbalances between regional authorities and large economic actors in the framework of green transformations. In both regions, implementing the forest-based bioeconomy appeared to be an obvious choice. However, regional economies and transformations are entangled among national, subnational and supranational institutions, often involving large corporations that are looking for places to invest. This creates a need for regional actors to formulate attractive strategies and incentives, while posing challenges for sustainable and inclusive transformations.

References

- Ahlqvist, T., and H. Sirviö. 2019. “Contradictions of Spatial Governance: Bioeconomy and the Management of State Space in Finland.” Antipode 51 (2): 395–418. doi:10.1111/anti.12498.

- Ahvenainen, J. 1990. “The Forests and Timber Industry of Finnish Lapland.” Forest & Conservation History 34 (4): 198–203. doi:10.2307/3983706.

- Aranguren, M. J., E. Magro, M. Navarro, and J. Wilson. 2019. “Governance of the Territorial Entrepreneurial Discovery Process: Looking Under the Bonnet of RIS3.” Regional Studies 53 (4): 451–461. doi:10.1080/00343404.2018.1462484.

- Boschma, R., K. Frenken. 2011. “Technological Relatedness, Related Variety and Economic Geography.” In Handbook of Regional Innovation and Growth, edited by P. Cooke, 187–197. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Boschma, R. A., and R. Wenting. 2007. “The Spatial Evolution of the British Automobile Industry: Does Location Matter?” Industrial and Corporate Change 16 (2): 213–238. doi:10.1093/icc/dtm004.

- Capello, R., and H. Kroll. 2016. “From Theory to Practice in Smart Specialization Strategy: Emerging Limits and Possible Future Trajectories.” European Planning Studies 24 (8): 1393–1406. doi:10.1080/09654313.2016.1156058.

- Casula, M. 2022. “Implementing the Transformative Innovation Policy in the European Union: How Does Transformative Change Occur in Member States?” European Planning Studies 0 (0): 1–27. doi:10.1080/09654313.2021.2025345.

- Coenen, L., T. Hansen, and J. V. Rekers. 2015. “Innovation Policy for Grand Challenges. An Economic Geography Perspective.” Geography Compass 9 (9): 483–496. doi:10.1111/gec3.12231.

- Coenen, L., and K. Morgan. 2020. “Evolving Geographies of Innovation: Existing Paradigms, Critiques and Possible Alternatives.” Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift 74 (1): 13–24. doi:10.1080/00291951.2019.1692065.

- Cooke, P. 2007. “To Construct Regional Advantage from Innovation Platforms.” European Planning Studies 15 (1): 179–194. doi:10.1080/09654310601078671.

- Cooke, P. 2010. “Regional Innovation Systems: Development Opportunities from the ‘Green Turn’.” Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 22 (7): 831–844. doi:10.1080/09537325.2010.511156.

- Cooke, P. 2016. “‘Four Minutes to Four Years: The Advantage of Recombinant over Specialized Innovation – RIS3 Versus ‘Smartspec’.” European Planning Studies 24 (8): 1494–1510. doi:10.1080/09654313.2016.1151482.

- Dahlström, M., and B. Hermelin. 2022. “Smart specialisering som modell för regional utvecklingsarbete – regionalt ledarskap och nya former för samverkan.” In Regioner och regional utveckling i en föränderlig tid Ymer, edited by I. Grundel, 121–143. Stockholm: Svenska Sällskapet för Antropologi och Geografi.

- Doloreux, D., and S. Parto. 2005. “Regional Innovation Systems: Current Discourse and Unresolved Issues.” Technology and Society 27 (2): 133–153. doi:10.1016/j.techsoc.2005.01.002.

- Etzkowitz, H., and L. Leydesdorff. 2000. “The Dynamics of Innovation: From National Systems and ‘Mode 2’ to a Triple Helix of University–Industry–Government Relations.” Research Policy 29 (2): 109–123. doi:10.1016/S0048-7333(99)00055-4.

- European Commission. 2012. “Innovating for Sustainable Growth: A Bioeconomy for Europe.”

- European Commission. 2018. “A Sustainable Bioeconomy for Europe: Strengthening the Connection Between Economy, Society and the Environment.” Updated Bioeconomy Strategy.

- European Commission. 2019. “The EU regional competitiveness index.” Regional and Urban Policy. https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docgener/work/2019_03_rci2019.pdf

- Foray, D., G. John, G. B. Xabier, L. Mikel, M. Philip, M. Kevin, N. Claire, and O.-A. Raquel. 2012. “Guide to Research and Innovation Strategies for Smart Specialization (RIS3).” doi:10.2776/65746.

- Foray, D., K. Morgan, and S. Radosevic. 2014. “The Role of Smart Specialisation in the EU Reserach and Innovation Policy Landscape.” 1–20. https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/information/publications/brochures/2018/the-role-of-smart-specialisation-in-the-eu-research-innovation-policy-landscape.

- Fritsche, U., B. Gianluca, C, David, G. Charis, H. Stefanie, M. Robert, and P. Calliope. 2020. “Future Transitions for the Bioeconomy Towards Sustainable Development and a Climate-Neutral Economy—Knowledge Synthesis Final Report.”

- Gianelle, C., D. Kyriakou, P. McCann, and K. Morgan. 2020. “Smart Specialisation on the Move: Reflections on Six Years of Implementation and Prospects for the Future.” Regional Studies 54 (10): 1323–1327. doi:10.1080/00343404.2020.1817364.

- Grillitsch, M., and T. Hansen. 2019. “Green Industry Development in Different Types of Regions.” European Planning Studies 27 (11): 2163–2183. doi:10.1080/09654313.2019.1648385.

- Grillitsch, M., and M. Trippl. 2018. “Innovation Policies and new Regional Growth Paths.” In Innovation Systems, Policy and Management, edited by J. Niosi, 329–358. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hassink, R., A. Isaksen, and M. Trippl. 2019. “Towards a Comprehensive Understanding of new Regional Industrial Path Development.” Regional Studies 53 (11): 1636–1645. doi:10.1080/00343404.2019.1566704.

- Holmgren, S., G. Alexandru, J. Johanna, S. K. Christoffer, S. Tove, and F. Klara. 2022. “Whose Transformation is This ? Unpacking the ‘Apparatus of Capture’ in Sweden’ s Bioeconomy.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 42 (May 2021): 44–57. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2021.11.005.

- Hurmekoski, E., L. Marko, L. Nataša, H. Lauri, and W. Georg. 2019. “Frontiers of the Forest-Based Bioeconomy – A European Delphi Study.” Forest Policy and Economics 102 (March): 86–99. doi:10.1016/j.forpol.2019.03.008.

- Iammarino, S. 2005. “An Evolutionary Integrated View of Regional Systems of Innovation: Concepts, Measures and Historical Perspectives.” European Planning Studies 13 (4): 497–519. doi:10.1080/09654310500107084

- IPCC. 2022. “6th Assessment Report.” https://www.ipcc.ch/ar6-syr/

- Isaksen, A. 2015. “Industrial Development in Thin Regions: Trapped in Path Extension?” Journal of Economic Geography 15: 585–600. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbu026.

- Isaksen, A., and S. E. Jakobsen. 2017. “New Path Development Between Innovation Systems and Individual Actors.” European Planning Studies 25 (3): 355–370. doi:10.1080/09654313.2016.1268570.

- Isaksen, A., S. Jakobsen, R. Njøs, and R. Normann. 2019. “Regional Industrial Restructuring Resulting from Individual and System Agency.” Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research 32 (1): 48–65. doi:10.1080/13511610.2018.1496322.

- Jolly, S., M. Grillitsch, and T. Hansen. 2020. “Agency and Actors in Regional Industrial Path Development. A Framework and Longitudinal Analysis.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 111 (February): 176–188. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.02.013.

- Kempton, L. 2015. “Delivering Smart Specialization in Peripheral Regions: The Role of Universities.” Regional Studies, Regional Science 2 (1): 489–496. doi:10.1080/21681376.2015.1085329.

- Lapland University of Applied Sciences Lapin Amk. 2019. “The Usage of Forest Resources in Finnish Lapland. Forest Resources and Bioeconomy.” Presentation made at Karlstad University (Sweden), November 14.

- LignoCity. 2021. “About Us.” Accessed June 23, 2021. https://lignocity.se/en/om-oss/.

- McCann, P. and L. Soete. 2020. “Place-based innovation for sustainability, Publications Office of the European Union.” Luxembourg, doi:10.2760/250023, JRC121271.

- MacKinnon, D. 2008. “Evolution, Path Dependence and Economic Geography.” Geography Compass 2 (5): 1449–1463. doi:10.1111/j.1749-8198.2008.00148.x.

- Marques, P., and K. Morgan. 2021. “Innovation Without Regional Development? The Complex Interplay of Innovation, Institutions, and Development.” Economic Geography 97 (5): 475–496. doi:10.1080/00130095.2021.1972801.

- Martin, R., and P. Sunley. 2006. “Path Dependence and Regional Economic Evolution.” Journal of Economic Geography 6 (4): 395–437. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbl012.

- Matthis, S. 2021. “Metsä Group to Build New Bioproduct Mill in Kemi, Finland.” Accessed March 3, 2021. https://www.pulpapernews.com/20210211/12251/metsa-group-build-new-bioproduct-mill-kemi-finland.

- Mäenpää, A., and J. Teräs. 2018. “In Search of Domains in Smart Specialisation: Case Study of Three Nordic Regions.” European Journal of Spatial Development 68: 1–20. doi:10.30689/ejsd2018:68.1650-9544.

- Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry of Finland. 2014. “Sustainable Growth from Bioeconomy. The Finnish Bioeconomy Strategy.” https://biotalous.fi/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/The_Finnish_Bioeconomy_Strategy_110620141.pdf.

- Morales, D., 2020a. CRS Policy brief No. 1. Regional bioeconomies in Catalonia and Finnish Lapland. Karlstad University https://www.kau.se/files/2020-02/Policy%20Brief%201-2020%20eng.pdf

- Morales, D., 2020b. CRS Policy brief No. 3. Public sector innovation in Värmland (Sweden) and Finnish Lapland (Finland). Karlstad University https://www.kau.se/files/2020-12/CRS_PolicyBrief_nr3-2020_en_final.pdf

- Morales, D., and L. Sariego-Kluge. 2021. “Regional State Innovation in Peripheral Regions: Enabling Lapland’s Green Policies.” Regional Studies, Regional Science 8 (1): 54–64. doi:10.1080/21681376.2021.1882882.

- Morgan K. 2017. “Nurturing novelty: Regional innovation policy in the age of smart specialisation.” Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 35 (4): 569–583. doi:10.1177/0263774X16645106

- Morgan, K., M. Pedro. 2019. “The Public Animateur: mission-led innovation and the ‘smart state’ in Europe,” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 12 (2): 179–193. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsz002

- Nieth, L., P. Benneworth, D. Charles, L. Fonseca, C. Rodrigues, M. Salomaa, M. Stienstra, et al. 2018. “Embedding Entrepreneurial Regional Innovation Ecosystems: Reflecting on the Role of Effectual Entrepreneurial Discovery Processes.” European Planning Studies 26 (11): 2147–2166. doi:10.1080/09654313.2018.1530144.

- Nordfeldt, M., and M. Dahlström. forthcoming. “Civil Society in Local Sustainable Transformation—Can Bottom-up Activities Meet Top-Down Expectations?”

- Nordström, E.-M., F. Niklas, L. Anders, K. Anu, B. Johan, H. Petr, K. Florian, F. Stefan, F. Oliver, L. Tomas, and N. Annika. 2016. “Impacts of Global Climate Change Mitigation Scenarios on Forests and Harvesting in Sweden.” Canadian Journal of Forest Research 46 (12): 1–52.

- OECD. 2020. “Evaluation of the Academy for Smart Specialisation.”

- Paper Province. 2019. “Nyheter: Seperator KM7 tar BillerudKorsnäs rakt in i framtiden.” Accessed December 14, 2021. https://paperprovince.com/varldens-modernaste-kartongfabrik-invigd/.

- Paulsson, D. 2019. “Report on the Implementation of Smart Specialisation in Sweden.”

- Pugh, R. 2014. “‘Old wine in new bottles’? Smart Specialisation in Wales, Regional Studies,” Regional Science, 1 (1): 152–157. doi:10.1080/21681376.2014.944209

- Pugh, R. 2018. “Questioning the Implementation of Smart Specialisation: Regional Innovation Policy and Semi-Autonomous Regions.” Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 36 (3): 530–547. doi:10.1177/2399654417717069.

- Pülzl, H., A. Giurca, D. Kleinschmit, B.J.M. Arts, I. Mustalahti, A. Sergent, L. Secco, D. Pettenella, and V. Brukas. 2017. “The Role of Forests in Bioeconomy Strategies at the Domestic and EU Level, Towards a Sustainable European Forest-Based Bioeconomy – Assessment and the Way Forward.”

- Pülzl, H., D. Kleinschmit, and B. Arts. 2014. “Bioeconomy – An Emerging Meta-Discourse Affecting Forest Discourses?” Scandinavian Journal of Forest Research 29 (4): 386–393. doi:10.1080/02827581.2014.920044.

- Ramcilovic-Suominen, S., and H. Pülzl. 2018. “Sustainable Development – A ‘Selling Point’ of the Emerging EU Bioeconomy Policy Framework?” Journal of Cleaner Production 172: 4170–4180. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.12.157.

- Ranga, M. 2018. “Smart Specialization as a Strategy to Develop Early-Stage Regional Innovation Systems.” European Planning Studies 26 (11): 2125–2146. doi:10.1080/09654313.2018.1530149.

- Region Värmland. 2015. “Värmland’s Research and Innovation Strategy for Smart Specialisation 2015–2020.” https://www.regionvarmland.se/globalassets/global/utveckling-och-tillvaxt/naringsliv-forskning-innovation/vris3.pdf.

- Region Värmland. 2021. “Värmlands forsknings- och innovationsstrategi för hållbar smart specialisering 2022-2028. Remissversion.” Karlstad.

- Regional Council of Lapland. n.d. “Arctic Smartness. Implementing Smart Specialisation in Lapland.” Accessed January 11, 2022. https://arcticsmartness.eu/.

- Rodríguez-Pose, A., and C. Wilkie. 2017. “Revamping Local and Regional Development Through Place-Based Strategies.” Cityscape: A Journal of Policy Development and Research 19 (1): 151–170.

- Sandulli, F. D., E. M. Gimenez-Fernandez, and M. I. Rodriguez Ferradas. 2021. “The Transition of Regional Innovation Systems to Industry 4.0: The Case of Basque Country and Catalonia.” European Planning Studies 29 (9): 1622–1636. doi:10.1080/09654313.2021.1963049.

- SCB Kontigo. 2018. “Bioekonomi – regional statistik. Bioekonomi regioner i samverkan.” Accessed December 14, 2021. https://app.powerbi.com/view?r=eyJrIjoiMjQ4NTFkZjgtMmIyZC00NGNkLTgwNzAtN2MzOTFhZGU2NjBlIiwidCI6IjIyZjA4NWJlLWI1MjMtNGVhYS05YTI3LTQyZjZjYjExZTBlNiIsImMiOjh9.

- Sotarauta, M., and N. Suvinen. 2019. “Place Leadership and the Challenge of Transformation: Policy Platforms and Innovation Ecosystems in Promotion of Green Growth.” European Planning Studies 27 (9): 1748–1767. doi:10.1080/09654313.2019.1634006.

- Stora Enso. 2019. “Press Release.” Accessed December 14, 2021. https://www.storaenso.com/sv-se/newsroom/press-releases/2019/5/stora-ensos-nya-produktionslinje-for-korslimmat-tra-vid-gruvons-sagverk-ar-invigd.

- Timonen, K., R. Anu, K. Sirpa, S. Keijo, M. Pekka, and L. Helsinki. 2018. “Green Economy Process Modelling. Natural Resources and Bioeconomy Studies.” Helsinki.

- Tödtling, F., H. Christoph, S. Tanja, and A. Alexander. 2014. “Factors for the Emergence and Growth of Environmental Technology Industries in Upper Austria.” Mitteilungen der Osterreichischen Geographischen Gesellschaft 156 (April): 115–140. doi:10.1553/moegg156s115.

- Tödtling, F., and M. Trippl. 2013. “Transformation of Regional Innovation Systems.” In Re-framing Regional Development: Evolution, Innovation, and Transition, edited by P. Cooke, 262–297. London and New York: Routledge.

- Tödtling, F., and M. Trippl. 2018. “Regional Innovation Policies for New Path Development – Beyond Neo-Liberal and Traditional Systemic Views.” European Planning Studies 26 (9): 1779–1795. doi:10.1080/09654313.2018.1457140.

- Trippl, M., S. Baumgartinger-Seiringer, A. Frangenheim, A. Isaksen, J. Rypestøl, et al. 2020. “Unravelling Green Regional Industrial Path Development: Regional Preconditions, Asset Modification and Agency.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 111 (February): 189–197. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.02.016.

- Truffer, B., and L. Coenen. 2012. “Environmental Innovation and Sustainability Transitions in Regional Studies.” Regional Studies 46 (1): 1–21. doi:10.1080/00343404.2012.646164.

- Veldhuizen, C. 2020. “Smart Specialisation as a Transition Management Framework: Driving Sustainability-Focused Regional Innovation Policy?” Research Policy 49 (6): 103982. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2020.103982.

- Viitanen, J., and A. Mutanen. 2018. “Finnish Forest Section Economic Outlook 2018–2019.” Helsinki.

- Wolfslehner, B., L. Stefanie, P. Helga, B.-B. Annemarie, C. Andrea, and M. Marco. 2016. “Forest Bioeconomy. A New Scope for Sustainability Indicators.” From Science to Policy 4. European Forest Institute.

- Zhang, J., Bojie Fu, Mark Stafford-Smith, Shuai Wang, Wenwu Zhao. 2020. “Improve Forest Restoration Initiatives to Meet Sustainable Development Goal 15.” Nature Ecology & Evolution 5 (1): 10–13. doi:10.1038/s41559-020-01332-9.

Interviews

- Interview 1. Regional Government Strategist in Innovation and Development, Karlstad (Värmland), 2020. Online.

- Interview 2. Regional Government Strategist in Innovation, Karlstad (Värmland), 2020. Online.

- Interview 3. Researcher in the Forest-Based Bioeconomy at Luke, Rovaniemi (Finnish Lapland), 2019.

- Interview 4. Regional Government and Industrial Cluster Representative, Rovaniemi (Finnish Lapland), 2019.

- Interview 5. Advisers at Proagria, Rovaniemi (Finnish Lapland), 2019.

- Interview 6. Research and Innovation Office at University of Lapland, Rovaniemi (Finnish Lapland), 2019.

- Interview 7. Future Bioeconomies Group Manager at University of Applied Sciences, Rovaniemi (Finnish Lapland), 2019.

- Interview 8. Regional Government Strategist in Innovation and Development, Karlstad (Värmland), 2021. Online.