ABSTRACT

Previous work on shrinking cities has mainly addressed shrinkage and its effects in large and former industrial cities and not as much in municipalities in rural areas. In this paper, we focus on infrastructure challenges, responsibilities, and growth strategies in Swedish municipalities. We argue that there is a tension between the responsibilities connected to the municipal operations and infrastructure challenges posed by being a shrinking municipality on the one hand, and the ways the municipalities are planning for growth on the other hand. The municipalities are all struggling with the effects of population decline, leading to economic strains in all areas, including infrastructure management and development, but investments in infrastructure are many times directed towards the establishment of specific industries such as the tourism or mining industry with the belief of attracting new inhabitants, visitors, firms and industry. In addition, many of the municipalities lack the capacity and jurisdiction needed to manage the infrastructure development in some areas such as fibre optics, district heating, and electricity grids. Also, in some municipalities, the populations are spread over large geographical areas but must still provide infrastructure services to all inhabitants.

1. Introduction

The population of about half of Sweden’s 290 municipalities are shrinking and have done so for the past few decades (Statistics Sweden Citation2021). However, this is not only a Swedish phenomenon, cities and regions are shrinking all over the world and have done so for a long time (Hollander Citation2018). Even so, previous work on shrinking cities has principally addressed shrinkage in large and former industrial cities such as Detroit and Manchester and the so called ‘boom cities’ Las Vegas and Orlando in the Sun Belt in the US. Also the Shrinking Cities International Network (SCIRN) defined a shrinking city as a densely populated area with a minimum population of 10,000 residents, having faced population decline for more than two years (Hollander and Németh Citation2011). At the same time, about 50% of European cities are shrinking, where the majority of these are small and medium-sized cities, many with fewer than 10,000 inhabitants (Wolff and Wiechmann Citation2017). Thus, small towns and rural areas fall outside the definitions of shrinking cities and arguably face other problems compared to large, shrinking cities (Ganser and Piro Citation2012; Wiechmann and Bontje Citation2015; Hospers and Syssner Citation2017; Syssner Citation2020). For example, research has largely focused on theories and strategies for neighbourhood change and/or turning vacant areas into parks and recreational areas in larger cities, but such strategies may not work for small municipalities. Similarly, infrastructure matters have mainly been addressed by studying over-dimensioned infrastructures and rightsizing, or abandoned properties and vacant buildings in urban areas (e.g. Schilling and Logan Citation2008; Sousa and Pinho Citation2015; Jonsson and Syssner Citation2016). In addition, many local governments are developing growth strategies to increase their population (e.g. Schatz Citation2017; Syssner Citation2020) rather than strategies for how to deal with shrinkage and instead of dealing with the consequences of demographic decline. For example, many municipalities are investing and developing their infrastructure in relation to specific areas such as tourism attractions and ski resorts, industrial developments, mining, and attractive residential areas.

For already small, sparsely populated municipalities, as in the cases in Sweden, the possibilities to deal with decreasing populations, resulting in lower revenue streams through lower income taxes and fees, is today one of their biggest challenges. Thus, an obvious, albeit difficult task is to turn that trend around and increase the population again, often through growth strategies and investments to support growth (e.g. Syssner Citation2014; Syssner Citation2020). In addition, all municipalities have mandatory responsibilities and must provide welfare services such as childcare and elderly care, schools, spatial planning and rescue services, no matter the size of the municipality. The municipalities are also responsible for infrastructure development and maintenance as it is mandatory to handle water and sewage (WaS), deal with municipal roads, support the development of fibreoptic grids (FOGs), and (in many cases) in the energy sector, trough for example ownership of district heating (DH) and to produce electricity (Magnusson Citation2016; Syssner Citation2020). An urgent matter is the management of existing infrastructure, such as WaS, and municipal roads, out of which many are in urgent need of re-investment and upgrading (e.g. Jonsson and Syssner Citation2016; Pike et al. Citation2019). To be able to handle these tasks, the municipal capacity, being it in economic or organizational terms, or having the competence, is a key question. This also includes matters of jurisdiction, responsibility, capacity, and geographical sparsity. In certain areas, especially the energy sector, the municipalities have lost much of their jurisdiction over the last decades, through privatizations of energy companies (Magnusson Citation2016), but still they are highly dependent on these services.

On a more overall level, we start from a sociotechnical perspective on infrastructure systems. We mainly focus on what Hodson and Marvin (Citation2010) call ‘critical infrastructures’ such as WaS, DH, electricity, roads, telecommunications, and FOGs. These are all mature, grid-based systems with high investment and maintenance costs, but all have different ownership and management structures.

This means that not only do we interpret infrastructures as large technical systems, but we also link the development of infrastructure closely to society, and the institutions that regulate and manage it (Kaijser Citation1994; Jonsson Citation2000; Addie, Glass, and Nelles Citation2020). Thus, changes in either the organizational or the technical parts of these systems may have large effects in society (Jonsson Citation2000). For example, management and organizational changes, together with changing ownership, can affect the access of citizens to basic infrastructure and affect its pricing and terms of service. This can, in turn, lead to the inclusion or exclusion of certain groups and geographies and increase tensions between more rural and urban areas (Pike et al. Citation2019). Thus, there is a close relationship between such effects and uneven geographical development, shaped by various social, economic and political processes that produce and reproduce spatial inequalities (Harvey Citation1996). In addition, infrastructure systems have a clear geographical and spatial dimension since they, once they are built, are difficult to adapt to new realities (Humer Citation2018).

Against this background, we try to fill a gap in research on shrinkage and infrastructure management in smaller towns and rural areas by focusing on a municipal perspective on infrastructure challenges, responsibilities, and growth strategies. The focus is on tensions between the responsibilities connected to the municipal operations and infrastructure challenges posed by being a shrinking municipality on the one hand, and the ways the municipalities are planning for growth on the other hand. The aim is to account for the many and sometimes contradictory ideas local government representatives have regarding the management and planning of infrastructure in shrinking areas. More specifically, the aim is to highlight those contradictions and tensions that could be observed within and between those ideas by focusing on the following research questions:

RQ1: How do local government representatives relate to the responsibilities they have regarding critical infrastructure and in relation to what resources they have access to?

RQ2: How do local government representatives understand existing infrastructure in the light of limited resources?

RQ3: How do local government representatives relate infrastructure investments to growth strategies?

Firstly, we present an overview of the literature on shrinking municipalities in relation to policies and strategies for dealing with population shrinkage followed by a discussion on infrastructure challenges in shrinking areas. Next, the methods are introduced followed by three analysis subsections related to the study’s research questions. The paper ends with a concluding discussion.

2. Shrinking municipalities, strategies for growth and infrastructure challenges

Today, the variety of planning strategies and policies dealing with shrinkage are multiple and have mainly targeted population growth. Within the planning literature, more growth-oriented strategies for developing places are well known. For example, strategies for urban regeneration, cultural development and urban design have been used to change negative development paths (Bianchini Citation1993; Booth and Boyle Citation1993). Thus, many local and regional governments have dealt with shrinkage by steering their planning strategies towards strategic planning, focusing on long-term visions, growth strategies and place branding to attract new inhabitants, visitors, investments, firms and industries (Friedmann Citation2004; Healey Citation2004; Lucarelli and Heldt Cassel Citation2019). For example, municipalities struggle to attract investments by making themselves attractive for businesses, through, e.g. tax reduction, subsidizing private development, the (re)development of brownfield sites and old industrial areas, and/or supporting industrial clusters (Rhodes and Russo Citation2013). Even though research has shown that efforts to support tourism do not always lead to economic growth, employment and welfare, promoting tourism is often used as a growth strategy to find ‘new’ solutions and visions for sustaining rural communities (Syssner and Olausson Citation2019). Since the tourism and hospitality sectors have low entrance barriers for employment, it is believed that such action will help to retain a younger population in these places (Müller and Jansson Citation2006). Other growth strategies include urban regeneration processes, cultural development, and urban design to attract new inhabitants (e.g. Bianchini Citation1993; Florida Citation2002). In rural areas, similar strategies might address broader groups, but very often target potential returnees and/or families with children. However, these strategies have not been fruitful for population growth, at least not in the Swedish context (Hansen and Niedomysl Citation2008; Eimermann et al. Citation2018).

Some scholars have started to question this growth-oriented paradigm (e.g. Wiechmann and Bontje Citation2015; Pallagst et al. Citation2019; Syssner Citation2020), and calls for more nuanced planning strategies in shrinking municipalities. For example, Sousa and Pinho (Citation2015) differentiated between reaction and adaptation strategies. Reaction occurs when planning responses involve approaches, and strategies (recommendations) to reverse population decline and in turn reach population growth. On the contrary, adaptation refers to means of accepting the effects of shrinkage and to optimize its consequences. Syssner (Citation2020) argued that local governments in municipalities with a shrinking population must focus on developing ‘local adaptation policies’. This means that instead of a strict focus on population growth, local governments should focus on developing alternative ways of providing and maintaining service to their citizens in relation to the geographical and demographic conditions. For example, Hibbard and Lurie (Citation2019) showed that a well-developed local development strategy related to people’s ties to the locality where they are entangled can contribute to local development. However, these local development strategies must both recognize emerging challenges and problems as well as opportunities. Campos-Sánchez, Reinoso-Bellido, and Abarca-Álvarez (Citation2019) suggest that taking an environmental and low-cost measurement approach together with improving the quality of life for residents would be a sustainable strategy for shrinking municipalities. This included, for example, infrastructure flexibility, environmental mitigation, ecological restoration, local use of forests and green areas and the support of local initiatives to increase social cohesion.

One of the main challenges in many rural areas is the possibility to maintain and preserve services, both public and private, e.g. retail stores, pharmacies, healthcare, schools and other public service, bars and restaurants (Syssner Citation2020). Thus, the presence of a variety of service amenities is an important aspect of the further development of these areas (see also: Niedomysl and Amcoff Citation2011; Humer, Rauhaut, and Marques Da Costa Citation2013; Humer and Palma Citation2013; Garlandini and Torricelli Citation2017). Here, we argue that critical infrastructure systems have become increasingly entangled with planning strategies for growth and attractiveness. The ways in which these systems are governed and planned for affect the overall development of these places, which can reinforce inequality between and within regions (Naumann and Reichert-Schick Citation2013). Some of the most obvious consequences of lower population densities are over-dimensioned infrastructures and vacant buildings (Haase, Haase, and Rink Citation2014; Sousa and Pinho Citation2015). In large and densely populated cities, this may be considered to be positive (Schilling and Logan Citation2008), but that is not the case in small Swedish municipalities. Rather, the economic consequences and reduced fiscal bases are severe and pose long-term problems (Martinez-Fernandez et al. Citation2016), affecting the quality not only of services within the welfare system, but also of critical infrastructure. In addition, the liberalization, privatization and commercialization of services and welfare systems have led to more managerial forms of governance, also influencing the organizational and managerial principles of the development of local infrastructure systems (Magnusson Citation2016).

3. Methods and cases

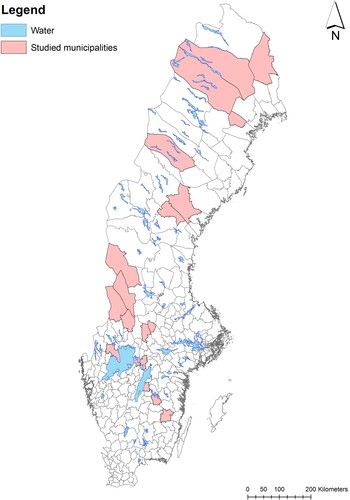

In order to study the infrastructure development and management in Swedish shrinking municipalities, we conducted case studies in 19 Swedish municipalities. All municipalities included have experienced long-term shrinkage and continuous population loss during the past 50 years (see ).

Table 1. Overview of the municipalities included in the study in relation to the current population, population density and population change.Footnote2

Twelve of the 19 municipalities have less than 10,000 inhabitants and are defined as rural, meaning that at least 50% of their population live in rural areas (Tillväxtverket Citation2020). The municipalities all have smaller populations and lower densities than the Swedish mean values (35,971 and 159.5 inhabitants/km2). In line with Syssner (Citation2020), arguing that the implications of shrinkage must be treated as context-dependent, i.e. that it depends on the local and central political, economic and geographical conditions of the municipalities, we ensured that the municipalities were located throughout Sweden ().

The municipalities were also chosen to represent a variety of economic activities. Due to time limitation of the project and to be able to conduct an equal number of interviews in all municipalities, we had to limit the number of municipalities in the study to 19.

In total, 53 interviews were conducted with local government representatives, including planners (19), local politicians (17), representatives for energy companies (15), and others (3), between January and December 2020. The interviews were semi-structured and conducted in Swedish. They were focused on themes such as infrastructure challenges, organization of the municipality, external collaborations, and the planning strategies used to deal with a shrinking population. The Covid-19 pandemic meant that we were compelled to conduct the interviews (usually about 60 min long) using digital tools. We would have preferred to conduct the interviews in person, but the tools used allowed us and the interviewee to see each other and read the body language, components that are important in interviews (Kvale and Brinkmann Citation2014).

In addition, strategic planning documents were extensively analyzed. These documents included the comprehensive plans (20), other strategic documents (28), and the municipal annual reports for the years 2014–2019 (106). Even though the municipal comprehensive plans are not legally binding, they guide the overall development path and land use within the municipality borders. Thus, they are one of the main instruments that guide spatial planning in Sweden (Persson Citation2013). The texts were carefully read by the authors, and a code book was developed focusing on specific themes, such as population development, future visions, and infrastructure development and management.

4. Results

In the following section, we present the results of our study based on the research questions presented in the introduction; concerning responsibilities, existing infrastructure in relation to limited resources, and infrastructure in relation to growth strategies.

4.1. Local government responsibilities in relation to resources

The municipalities studied describe similar challenges related to their shrinking populations. The overall challenges are related to demographic matters, such as outmigration and low birth rates, aging populations and a large part of the workforce reaching retirement in the coming years. As a result, there is an increasing need for highly skilled labour in both public and private sectors, and the municipalities will need to attract people with a variety of skills (e.g. Syssner Citation2020). These changing demographic patterns lead to decreasing revenues and tax incomes to cover public services and, as will be shown below, to manage and develop sparse and over-dimensioned infrastructure (e.g. Syssner and Jonsson Citation2020).

One of the major concerns in the municipalities is how to dimension the infrastructure to fit the current population size. This especially regards roads, buildings (in particular public housing that was built in the 1960s and 1970s), and the WaS system. Larger cities that face shrinkage can adapt to smaller populations by downsizing (e.g. Sousa and Pinho Citation2015), but this is not the situation in the cases studied here. The quotation below points to these differences:

… it is my absolute biggest challenge, the expansion of WaS. We have almost indebted the municipal residents up to a billion SEK to be able to expand WaS, but also to fix the existing WaS systems with waterworks and treatment plants and so on. Now I do not remember exact figures, but I think we have 14 treatment plants in the municipality, compared to our neighboring municipality which has one. And we have 21 waterworks, so it is a huge infrastructure. Each inhabitant owns approximately 1.5 kilometers of water supply and sewerage line, compared with Vallhallavägen (in Stockholm, authors’ note), which may have 25 cm. So, the WaS collective is quite strained. (Interview 49, municipal official)

In many municipalities, multi-dwelling buildings have been demolished to adapt to the population size, while others struggle with unattractive housing that is expensive to maintain. Demolition can lower the cost of maintenance of empty apartments, but buildings are not isolated entities, and affect other infrastructure. The demand for heat will decrease and, as these buildings mainly have DH, technical measures may be necessary to handle changed pressure in the system and to plug the DH-pipes. In addition, most of the municipalities cover large geographical areas and are characterized by a low population density, also meaning that the infrastructure systems cover large geographical areas. It becomes a complex matter for the municipalities to manage and provide their citizens with the mandatory critical infrastructure and people in more rural parts still need this infrastructure as part of their daily life. Especially, the WaS systems and roads cannot be easily removed, since they are spread over large geographical areas where people are living:

We used to be almost 12,000 inhabitants and now we are about 4,700. But we have not been able to, for example, dismantle kilometers of roads. We still have the same number of roads, and we still have the same number of conduits to transport water and sewage. […] and it gets more and more expensive the fewer we are to share the costs. (Interview 26, politician)

In Sweden, the governance of WaS is mandatory for the municipalities and are run either within the municipal administration or as a municipal company, and the municipalities are not permitted to make a profit on. Electricity systems are structured as national, regional, and local grids, where the national grid is owned by the state, and the others by diverse actors. In recent decades municipal ownership has decreased and the electricity market has been liberalized with production and sales open for competition, while the grids remain as natural monopolies (Bladh Citation2020). Roads are managed similarly to electricity grids, with state ownership and maintenance of main roads, and municipal ownership of local roads, especially within cities and towns (Trafikverket Citation2021). Today, roads and WaS systems require most re-investment and maintenance and in line with other studies most municipalities have their largest maintenance deficit in these systems (e.g. Jonsson and Syssner Citation2016; Syssner and Jonsson Citation2020):

In all budget preparations, the WaS network is like a ticking bomb. Everything was built during the 50s, 60s and 70s, just like in all of Sweden actually, and now pipes are getting old and in need of maintenance. They were built for 30,000 in a municipality which now has 19,000. (Interview 38, politician)

This shows that the municipalities must manage the expected and mandatory basic critical infrastructure for its citizens, this, even though the population decrease, and the costs and fees for the local population increase. In municipalities with a strong tourism sector, the adjustment of the infrastructure systems to fit the variations in the population over the year is another challenge. This makes roads, WaS systems and FOGs heavily used during certain periods of the year, and underutilized at others:

We must have capacity when everyone is flushing their toilets on New Year's Eve, so we can take care of everything. And in May and June, we have a huge overcapacity. […] And not all infrastructures can handle that. (Interview 27, municipal official)

Another key obstacle in small municipalities is the municipal capacity, in terms of staffing and economy:

I do not think that we can have 100% perfect solutions, but if we can have 70% solutions so that we dońt break all the laws, I think we have done enough. Every morning I get up, I think about which of these ordinances and laws I will break today? Because it is a jungle in all the areas we work in. (Interview 49, municipal official)

Some municipalities have sought collaborations with neighbouring municipalities to fill the need for expertise, especially regarding planning and the organizational structure, and the degree of such collaboration is expected to increase (e.g. Syssner Citation2020). Traditionally, such collaborations have concerned the school sector and rescue services but have expanded to such areas as IT, technical services, and infrastructure management. This development brings both negative and positive effects. The positive side is that it becomes easier to attract skilled personnel to certain positions and that the pool of expertise available in the municipalities becomes wider. In one municipality, this made it possible to employ a water engineer together with other municipalities, something that would not have been economically viable within their own organization. This competence available and the degree of collaboration also made it possible to connect the WaS systems between the municipalities, which reduced problems with an over-dimensioned WaS system. The negative side is that moving their entire planning offices and technical service departments can lead to certain questions regarding maintenance and infrastructure development being moved further away from the municipality’s own organization. For municipalities covering large geographical areas, this kind of collaborations are, however, not always possible due to the sheer distance (Slutbetänkande av Kommunutredningen Citation2020). There is also a risk that local politicians and officials only see the benefits of their own locality. Thus, increased collaboration demands an understanding of other municipalities challenges and to make such collaborations work it is important to find appropriate structures (Rutgers-Zoet and Hospers Citation2018), which might be difficult under economic pressure.

All these matters show the complexity of sociotechnical systems. Few of the challenges are purely technical, they can all be managed, but social, economic, and political matters are the largest problems, together with the obduracy of the systems (Hommels Citation2005). Investments made are sunken costs and geographically fixed for decades to come.

4.2. Existing infrastructure and limited resources

In later years, many infrastructure systems have been under pressure from liberalization processes, where municipalities to some extents have lost control over the development and management of certain infrastructures. This is a particular concern of DH and is largely dependent on its ownership. Today DH systems are usually run within energy companies, often started by the municipality, but because of liberalization processes during the past 25 years, ownership has become more diversified and may be municipal, private, state, or intermunicipal and are run on market principles (Magnusson Citation2016). Even though the use of DH is an important component to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases, many municipalities have sold their DH operations due to a lack of economic resources. In this way they lose control and the strategic work carried out:

We sold our part of the DH company, we had 49 percent, and 51 percent was owned by X company, that in turn is owned by different kinds of venture capitalists. […] We sold in 2017 or 2018 and that was simply because we knew they were going to make investments and that for us would mean around SEK 130 million, and we do not have that money. (Interview 41, municipal official)

After a privatization, the municipality often loses control of the DH completely, often because of a lack of communication and weak relationships with the new owners:

We do not have any structured collaboration with X company. Sometimes we have contacted them since we wanted to connect more clients. After several years of nagging, we managed to connect the fire station, but they are not really interested. […] And the collaboration has decreased since they have raised the prices significantly and it has become a very expensive solution. (Interview 26, politician)

The consequence is that the municipalities lack jurisdiction and control over infrastructure systems that are crucial for the municipality itself and its inhabitants. Another consequence is that expertise and knowledge about the systems are moved further away from the municipal organization. The same is true for the development and investments in the capacity of electricity grids, where decreased ownership means that municipalities lose control over investments in power grids. A constant dialogue is necessary, especially in developing areas. This shows that another issue regarding the lack of jurisdiction in the municipalities is their ability to keep up with necessary investments for infrastructure development, especially where the responsibility for its expansion is unclear. Another example is the development of FOGs and masts for mobile telephony:

Now they are closing down the copper net, also in the main town, and that relates to another aspect of accessibility, because somehow access to the network is as important as access to electricity and water, and now we do not have complete cover for the mobile network in the municipality. And that is very serious, the operators are not doing what they should when they are getting their frequencies. There is no market-based reason for building masts in the municipality, but the operators should take responsibility and they are not, and that is serious. (Interview 41, municipal official)

FOGs are often developed in public–private partnerships while the mobile net has been developed mainly in competition, following liberalization logics in infrastructure development. The company structure, however, has often ensured a strong municipal influence. FOGs are run for profit (Falch et al. Citation2016), which might affect their future development in shrinking municipalities. Even though most of the municipalities studied here have relatively well-developed FOGs, some geographical areas lack access. If the mobile networks also are poor in such locations, problems arise when the copper net used for telecommunications is dismantled. There are several examples in the municipalities of the difficulties this can lead to. In some municipalities there were problems for the tourism sector to handle internet bookings and on-line payments:

We have companies and citizens where the copper net has been dismantled and who do not have mobile coverage and therefore cannot use their phones and they do not have access to fiberoptics. And that is a great challenge. We have a person in charge of this, but no tools to develop it. We can only support, and try to find external funding, maybe also to build municipal mobile masts in the future. We have tourism entrepreneurs who have to take their cars to check if they have any bookings in the booking system since they don’t have coverage in their facilities. (Interview 23, municipal official)

This development leads to ‘white spots’ with poor internet and poor mobile access. As investments in infrastructure in these areas are lower than in dense areas due to low expectations among investors, this can generate a downward spiral and increasing disparities between rural and urban areas (Matern, Binder, and Noack Citation2020). Other challenges regard the possibilities for people to stay in more rural areas of the municipalities, especially for the elderly:

The copper net has been dismantled, as they call it. But at the same time, we are not located in an area where they put up new masts and give us mobile solutions. […] At home I must sit next to the kitchen window to make it work, but that is not the worst. The problem is, when we talk about elderly care and when people want to stay in their old houses in more rural areas. (Interview 15, politician)

In addition, many of the municipalities under study here show an increasing frustration towards the national level. They feel abandoned in many matters and see economic resources being directed elsewhere and there is a growing criticism towards the current lack of investment in infrastructure systems from the national level:

One question is: does the state want a living countryside? At some point the state must ‘put its foot down’ and say, ‘Yes, we want that, and therefore we give these preconditions’. LIS areasFootnote1 or housing closer to water, financial support and regulations regarding FOGs, and all other things needed to develop the countryside. (Interview 21, politician)

4.3. Infrastructure and growth strategies

Even though statistical estimations predict that the current trend with shrinking populations in Swedish municipalities will continue, the majority are developing growth strategies and visions for increasing populations. These are intended to attract new inhabitants, visitors, investments, firms and industries, and focuses mainly on attractiveness and growth rather than on the necessary investments in infrastructure development and maintenance. It is taken for granted that appropriate infrastructure is available since its functioning and maintenance is also one of the main responsibilities of the municipalities. Many of the municipalities are also using infrastructure development as part of their growth strategies and expect that such development will change the current trajectory. As shown above, large investments in WaS systems in Swedish municipalities will be necessary to keep up with the required maintenance of these systems in the coming years. At the same time, the municipalities are also investing in and planning for major infrastructure expansions in e.g. the WaS systems. In this study, it was clear that the municipalities focused their investments on infrastructure in relation to specific areas in the locality, such as tourism attractions and ski resorts, industrial development and mining, and attractive residential areas. This development was especially strong in municipalities with an important winter-tourism:

Now, we are not only the central town, but we also have the same number of inhabitants during winter in the skiing area, [ … ]. Now, we are building a large WaS facility in the area. That is a SEK 300 million investment with WaS to these households. (Interview 43, politician)

Another strategic plan used by the municipalities to increase their attractiveness are known as ‘LIS’ areas. These plans were introduced in 2010 as an amendment to the comprehensive plans, and allow exemptions from the shoreline protection rules such that residential houses and second homes can be built, and small-scale tourism or farming businesses can be established close to shorelines or beaches in rural areas (Boverket Citation2014). Many municipalities see LIS areas as an opportunity to develop new and attractive residential areas, and thus to attract new inhabitants, mainly younger families. Due to their ‘attractive’ location in closeness to shorelines, LIS areas increase the probability of being granted bank credits and loans for housing, something that might not be possible in other parts of the municipalities. The use of LIS areas is also a strategic tool to support the development of the tourism sector to attract visitors, and thus to maintain services in more rural areas of the municipalities. The existing tourism activities may be expanded, together with strategic investments in infrastructure, including roads, WaS, railroads, local and regional airports, or for example, new ski lifts, scooter trails and camping lots:

A development of already existing activities is expected to contribute to rural development in the municipality through more job opportunities and it will generate more visitors. For the development of existing activities, the access to beaches and water is a prerequisite or at least a considerable advantage. (Torsby kommun Citation2020, 91)

The municipalities also see the availability of a well-functioning and well-developed FOG as an important aspect of their own attractiveness, especially in terms of increased digitalization, and possibilities for distance learning and remote work. The Corona pandemic has increased a renewed interest in the countryside, and an expectation that more people will move to rural areas when working from home. Also, high-quality FOGs have become taken for granted and part of the basic infrastructure of a municipality, which must, therefore, invest in such a grid:

We have invested approximately SEK 100 million in fiber expansion. There are no commercial forces that are interested in expanding fiber in our municipality. […] When we put WaS there and X company puts electricity, we also install fiber. So, it has become a must, you do not buy a plot if you do not have fiber. (Interview 49, municipal official)

I am a bit unsure of how new developer agreements have been agreed upon with new players in the remote villages and especially in (ski resort Y). How much costs they have taken in the fiber extension, but the municipality has been incredibly generous. It is clear that there is a vision that more and more people would want to become permanent residents in (ski resort Y), because you have every opportunity in the world to work from there. (Interview 46, politician)

The municipalities do not only support the development of the tourism industry, but also new developers and already established industries and firms by preparing land and making necessary investments in infrastructure. Even though these strategies can lead to new job opportunities, it brings large economic risks, when preparing and setting up the necessary infrastructure before the benefit of the planned development has been realized:

They had interested actors for the plots, but then failed because there was no infrastructure. Then the actor who wants to buy the plot and establish themselves there says: ‘Well, if you won’t have a road in place for two years, then we’ll go somewhere else’. Then they have to make this investment by having the main infrastructure in place to be able to sell these plots. (Interview 24, municipal official)

In several of the municipalities with a strong mining industry, there is a belief that this industry can expand and thus bring new job opportunities and population growth. One municipality believes that such a development could lead to a three-fold population increase. Another municipality states:

In Gällivare, a minimum scenario is seen with a labor need of at least 2000 people that could lead to a total population growth of about 4000 people, but also a maximum scenario has been painted where 3600 jobs could give a population growth of about 7000 people. (Gällivare kommun, Citation2012, 4)

In another municipality, hopes of reopening a mine brought optimism, accompanied by challenges:

And then it will be a big challenge for the municipality if it should now be a positive decision (to re-open the mine). Because we have to make sure people have somewhere to live and things like that. That the infrastructure is sufficient. There is so much to do. (Interview 50, municipal official)

A paradox in many of the strategies supporting growth is that the main advantage is connected to secondary gains. For example, Swedish industries do not pay municipal taxes and large shares of the labour in both mining industries, especially new ones, and tourism resorts, are workers registered in other municipalities, or even countries. It means that they do not pay income tax in the municipality, and the effects are that resource-intensive municipalities might still have weak economies. The effects of these enterprises are thus often the other services and companies that develop around them, where local inhabitants work.

5. Concluding discussion

We set out to discuss the many and sometimes contradictory ideas local government representatives have regarding the management and planning of infrastructure in shrinking areas. Our study supports the argument that there is a tension between municipal planning for growth while at the same time maintaining the existing municipal structures, especially critical infrastructure. By analyzing infrastructures as sociotechnical systems, and the relationship between physical, technical, political, social, organizational, and economical aspects, we show how obduracy and sunken costs of infrastructure generate problems difficult for the municipalities to manage. As shown, the municipalities are struggling with the effects of population decline, leading to economic strains in all areas, including infrastructure management and development. The tensions between responsibilities and jurisdictions are several. Regarding WaS and municipal roads, the municipalities have mandatory responsibilities to manage, but there are large needs for re-investments. They are also tied economically, as they cannot make profit and cannot operate these systems on market principles as, for example, DH and electricity. In some systems such as FOG, DH and electricity grids, the municipalities many times lack the capacity and jurisdiction needed to manage their development and are rather left to maintaining good communication with the infrastructure owners, both in terms of maintenance and growth. In the case of FOGs and telecommunications, they also need to step in to fill the white spots when the market principles of cherry-picking do not work. Municipalities have to take the perspective of the inhabitants, while market actors can think of people as customers and markets, which means that they often take investments that are necessary to maintain a ‘lowest level of service’ but with little potential for return on that investment. Another major challenge is that the population, in many cases, are spread over large geographical areas, but the municipalities must still provide infrastructure services to all inhabitants.

At the same time, the majority of the municipalities use growth strategies in relation to investments in infrastructure development and management, also closely related to the place-specific conditions in the municipality (e.g. Gustavsson, Elander, and Lundmark Citation2009; Syssner Citation2020). In municipalities without an already strong industry sector, focus was especially on developing infrastructure to create attractive living conditions close to beaches or coastal areas. In municipalities with an already strong tourism or mining industry, considerable investments were being made also in infrastructures such as WaS, FOGs, and mobile masts to prepare for future growth opportunities. Especially, the provision of broadband has become a necessity and digitalization important for making it possible for people to remain in, and move to, more rural areas. Some studies have shown that places with an already strong tourism industry might benefit from these kinds of investments as these places already have a high degree of public and commercial services as well as infrastructure systems, while places that do not already have these features tend to fall behind (Pettersson and Jonsson Citation2022). Thus, there is a tension between the responsibilities connected to the municipal operations and infrastructure challenges posed by being a shrinking municipality on the one hand, and the ways the municipalities are planning for growth on the other hand. There is a conflict between growth strategies requiring significant investments in new infrastructure, well before the revenues arrive, and other urgent investments.

This study also shows that the urban-rural divide is strong politically and seems to generate an ‘us vs. them’ attitude, in two aspects. Firstly, towards the national level, as the municipalities express a lack of support, especially for infrastructure investments. This is especially visible when the copper net used for telecommunications is dismantled and the further lack of development of FOG and mobile masts in some of the municipalities. The other ‘them’ is private actors, with new business models following a market logic of telecommunications and FOG development. Historically, the public involvement in infrastructure development and management was an over-arching principle, but as privatization and public–private partnership strategies have become more common, cherry-picking (Graham and Marvin Citation1994; Guy et al. Citation1999) has led to investments being directed towards the most lucrative areas, which are often the urban areas. A market-driven logic does not favour areas in rural, or rather non-metropolitan areas, and with international ownership from venture capitalists, as in the case of DH, the distance between inhabitants and companies grows. Other studies have also shown that inequalities in terms of access to basic service, income, education and welfare are increasing between and within regions, especially between urban and rural areas in Sweden (e.g. Enflo Citation2016; Enflo and Henning Citation2022), but not in terms of critical infrastructure development. Thus, there is a need for more studies pointing to the relationship between, on the one hand, increasing disparities between urban and rural areas and infrastructure development and, on the other hand, the ways municipalities are dealing with these increasing disparities.

Acknowledgements

In developing the ideas presented here, we especially thank Salvador Perez and fellow researchers and colleagues in Stripe/TEVS for their valuable comments on the text. The authors would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their input and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Areas identified by municipalities for development of residential buildings close to water and to allow exemptions from the shoreline protection rules.

2 Starting year 1968 is based on the first year with comparable statistics from Statistics Sweden. This was due to the municipal mergers taking place around these years (Statistics Sweden, Citation2021).

References

- Addie, J.-P., M. Glass, and J. Nelles. 2020. “Regionalizing the Infrastructure Turn: A Research Agenda.” Regional Studies, Regional Science 7: 10–26. doi:10.1080/21681376.2019.1701543

- Bianchini, F. 1993. “Remaking European Cities: The Role of Cultural Policies.” In Cultural Policy and Urban Regeneration: The West European Experience, edited by M. Parkinson, and F. Bianchini, 1–20. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Bladh, M. 2020. Vägskäl i svensk energihistoria – Den ena omställningen efter den andra. Stockholm: BoD.

- Booth, P., and R. Boyle. 1993. “See Glasgow, See Culture.” In Cultural Policy and Urban Regeneration: The West European Experience, edited by M. Parkinson, and F. Bianchini, 21–47. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Boverket. 2014. Vision for Sweden 2025. Karlskrona: Boverket.

- Campos-Sánchez, F., R. Reinoso-Bellido, and F. Abarca-Álvarez. 2019. “Sustainable Environmental Strategies for Shrinking Cities Based on Processing Successful Case Studies Facing Decline Using a Decision-Support System.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16: 3727. doi:10.3390/ijerph16193727

- Eimermann, M., P. Agnidakis, E. Åkerlund, and A. Woube. 2018. “Rural Place Marketing and Consumption-Driven Mobilities in Northern Sweden: Challenges and Opportunities for Community Sustainability.” The Journal of Rural and Community Development 12: 114–126. https://journals.brandonu.ca/jrcd/article/view/1487

- Enflo, K. 2016. “Regional ojämlikhet i Sverige. En historisk analys.” SNS.

- Enflo, K., and M. Henning. 2022. “Ekonomiska skillnader mellan svenska regioner under efterkrigstiden.” In Regioner och regional utveckling i en föränderlig tid, edited by I. Grundel, 63–80. Stockholm: Svenska Sällskapet för Geografi och Antropologi.

- Falch, M., A. Henten, R. Tadayoni, and I. Williams. 2016. “New Investment Models for Broadband in Denmark and Sweden.” Nordic and Baltic Journal of Information and Communications Technologies 2016: 1–18. doi:10.13052/NBICT.2016.001

- Florida, R. 2002. The Rise of the Creative Class: And How It's Transforming Work, Leisure, Community and Everyday Life. New York: Basic Books.

- Friedmann, J. 2004. “Strategic Spatial Planning and the Longer Range.” Planning Theory & Practice 5: 49–67. doi:10.1080/1464935042000185062

- Gällivare Kommun. 2012. Bostadsförsörjning Gällivare kommun, 2012–2030. Gällivare: Gällivare kommun.

- Ganser, R., and R. Piro. 2012. Parallell Patterns of Shrinking Cities and Urban Growth. Spatial Planning for Sustainable Development of City Regions and Rural Areas. Surrey: Ashgate Publishing Limited.

- Garlandini, S., and G. Torricelli. 2017. “Services for Citizens in Peripheral Areas: A Hierarchy of Centrality Based on Their Availability and Accessibility.” IJPP – Italian Journal of Planning Practice 7: 50–79. http://www.ijpp.it/index.php/it/article/view/74/65

- Graham, S., and S. Marvin. 1994. “Cherry Picking and Social Dumping: Utilities in the 1990s.” Utilities Policy 4: 113–119. doi:10.1016/0957-1787(94)90004-3

- Gustavsson, E., I. Elander, and M. Lundmark. 2009. “Multilevel Governance, Networking Cities, and the Geography of Climate-Change Mitigation: Two Swedish Examples.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 27: 59–74. doi:10.1068/c07109j

- Guy, S., S. Graham, S. Marvin, and O. Coutard. 1999. Splintering Networks. London & New York: Routledge.

- Haase, D., A. Haase and D. Rink. 2014. “Conceptualizing the Nexus between Urban Shrinkage and Ecosystem Services.” Landscape and Urban Planning 132: 159–169.

- Haikola, S., and J. Anshelm. 2020. “Evolutionary Governance in Mining: Boom and Bust in Peripheral Communities in Sweden.” Land Use Policy 93: 104056. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.104056

- Hansen, H., and T. Niedomysl. 2008. “Migration of the Creative Class: Evidence from Sweden.” Journal of Economic Geography 9: 191–206. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbn046

- Harvey, D. 1996. Justice, Nature and the Geographies of Difference. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers Ltd.

- Healey, P. 2004. “The Treatment of Space and Place in the New Strategic Spatial Planning in Europe.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 28: 45–67. doi:10.1111/j.0309-1317.2004.00502.x

- Hibbard, M., and S. Lurie. 2019. “If Your Rural Community Is Failing, Just Leave? The Revival of Place Prosperity in Rural Development Planning.” Journal of Planning Education and Research, doi:10.1177/0739456X19895319.

- Hodson, M., and S. Marvin. 2010. “Can Cities Shape Socio-Technical Transitions and How Would we Know if They Were?” Research Policy 39: 477–485. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2010.01.020

- Hollander, J. 2018. A Research Agenda for Shrinking Cities. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Hollander, J., and J. Németh. 2011. “The Bounds of Smart Decline: A Foundational Theory for Planning Shrinking Cities.” Housing Policy Debate 21: 349–367. doi:10.1080/10511482.2011.585164

- Hommels, A. 2005. “Studying Obduracy in the City: Toward a Productive Fusion between Technology Studies and Urban Studies.” Science, Technology, & Human Values 30: 323–351. doi:10.1177/0162243904271759

- Hospers, G.-J., and J. Syssner, eds. 2017. Dealing with Urban and Rural Shrinkage: Formal and Informal Strategies. Zürich: Lit Verlag.

- Humer, A. 2018. “Strategic Spatial Planning in Shrinking Regions.” In Dealing with Urban and Rural Shrinkage: Formal and Informal Strategies, edited by G.-J. Hospers, and J. Syssner, 73–86. Zürich: Lit Verlag.

- Humer, A., and P. Palma. 2013. “The Provision of Services of General Interest in Europe: Regional Indices and Types Explained by Socio-Economic and Territorial Conditions.” Europa 23: 85–104. doi:10.7163/Eu21.2013.23.5

- Humer, A., D. Rauhaut, and N. Marques Da Costa. 2013. “European Types of Political and Territorial Organisation of Social Services of General Interest.” Romanian Journal of Regional Science 7: 142–164.

- Jonsson, D. 2000. “Sustainable Infrasystem Synergies: A Conceptual Framework.” Journal of Urban Technology 7: 81–104. doi:10.1080/713684136

- Jonsson, R., and J. Syssner. 2016. “Demografianpassad infrastruktur?: Om hantering av anläggningstillgångar i kommuner med minskande befolkningsunderlag.” Nordisk Administrativt Tidsskrift 93: 45–64.

- Kaijser, A. 1994. I fädrens spår: den svenska infrastrukturens historiska utveckling och framtida utmaningar. Stockholm: Carlsson.

- Kvale, S., and S. Brinkmann. 2014. Den kvalitativa forskningsintervjun. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Lucarelli, A., and S. Heldt Cassel. 2019. “The Dialogical Relationship Between Spatial Planning and Place Branding: Conceptualizing Regionalization Discourses in Sweden.” European Planning Studies 28: 1375–1392. doi:10.1080/09654313.2019.1701293

- Magnusson, D. 2016. “Who Brings the Heat? – From Municipal to Diversified Ownership in the Swedish District Heating Market Post-Liberalization.” Energy Research & Social Science 22: 198–209. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2016.10.004

- Martinez-Fernandez, C., T. Weyman, S. Fol, I. Audirac, E. Cunningham-Sabot, T. Wiechmann, and H. Yahagi. 2016. “Shrinking Cities in Australia, Japan, Europe and the USA: From a Global Process to Local Policy Responses.” Progress in Planning 105: 1–48. doi:10.1016/j.progress.2014.10.001

- Matern, A., J. Binder, and A. Noack. 2020. “Smart Regions: Insights from Hybridization and Peripheralization Research.” European Planning Studies 28: 2060–2077. doi:10.1080/09654313.2019.1703910

- Müller, D., and B. Jansson. 2006. Tourism in Peripheries: Perspectives from the far North and South. Wallingford: CAB International.

- Naumann, M., and A. Reichert-Schick. 2013. “Infrastructure and Peripheralization: Empirical Evidence from North-Eastern Germany.” In Peripheralization. The Making of Spatial Depencencies and Social Justice, edited by A. Fischer-Tahir, and M. Naumann, 145–167. Berlin: Springer VS.

- Niedomysl, T., and J. Amcoff. 2011. “Is There Hidden Potential for Rural Population Growth in Sweden?” Rural Sociology 76: 257–279. doi:10.1111/j.1549-0831.2010.00032.x

- Pallagst, K., R. Fleschurz, S. Nothof, and T. Uemura. 2019. “Shrinking Cities: Implications for Planning Cultures?” Urban Studies 58: 164–181. doi:10.1177/0042098019885549

- Persson, C. 2013. “Deliberation or Doctrine? Land Use and Spatial Planning for Sustainable Development in Sweden.” Land Use Policy 34: 301–313. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2013.04.007

- Pettersson, R., and A. Jonsson. 2022. “Turism och Regional Utveckling.” In Regioner och regional utveckling i en föränderlig tid, edited by I. Grundel, 145–162. Stockholm: Svenska Sällskapet för Geografi och Antologi.

- Pike, A., P. ÓBrien, T. Strickland, G. Thrower, and J. Tomaney. 2019. Financialising City Statecraft and Infrastructure. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Rhodes, J., and J. Russo. 2013. “Shrinking ‘Smart’?: Urban Redevelopment and Shrinkage in Youngstown, Ohio.” Urban Geography 34: 305–326. doi:10.1080/02723638.2013.778672

- Rutgers-Zoet, J., and G.-J. Hospers. 2018. “Regional Cooperation in Rural Areas: The Case of Actherhoek.” In Dealing with Urban and Rural Shrinkage: Formal and Informal Strategies, edited by G.-J. Hospers, and J. Syssner, 87–99. Zürich: Lit Verlag.

- Schatz, L. 2017. “Going for Growth and Managing Decline: The Complex Mix of Planning Strategies in Broken Hill, NSW, Australia.” The Town Planning Review 88: 43–57. doi:10.3828/tpr.2017.5

- Schilling, J., and J. Logan. 2008. “Greening the Rust Belt: A Green Infrastructure Model for Right Sizing America's Shrinking Cities.” Journal of the American Planning Association 74: 451–466. doi:10.1080/01944360802354956

- SFS 2006:412 Lag (2006:412) om allmänna vattentjänster.

- SOU. 2020. 8 Starkare kommuner - med kapacitet att klara välfärdsuppdraget. Stockholm: Regeringskansliet.

- Sousa, S., and P. Pinho. 2015. “Planning for Shrinkage: Paradox or Paradigm.” European Planning Studies 23: 12–32. doi:10.1080/09654313.2013.820082

- Statistics Sweden. 2021. Folkmängden efter region, civilstånd, ålder och kön. År 1968 - 2020. Örebro: Statistics Sweden.

- Svenskt Vatten. 2020. Investeringsbehov och framtida kostnader för kommunalt vatten och avlopp – en analys av investeringsbehov 2020–2040. Bromma: Svenskt Vatten.

- Syssner, J. 2014. Politik för kommuner som krymper. Norrköping: Centrum för kommunstrategiska studier.

- Syssner, J. 2020. Pathways to Demographic Adaptation. Cham: Perspectives on Policy and Planning in Depopulation Areas in Northern Europe, Springer.

- Syssner, J., and R. Jonsson. 2020. “Understanding Long-Term Policy Failures in Shrinking Municipalities: Examples from Water Management System in Sweden.” Scandinavian Journal of Public Administration 24: 3–19.

- Syssner, J., and A. Olausson. 2019. “Att främja utveckling inom besöksnäringen.” In Entreprenörskap för en levande landsbygd, edited by K. Wennberg, 279–294. Växjö: Familjen Kamprads Stiftelse.

- Tillväxtverket. 2020. Städer och landsbygder. Forskning, fakta och analys. Stockholm: Tillväxtverket.

- Torsby Kommun. 2020. Tillägg till översiktsplanen: områden för landsbygdsutveckling i strandnära lägen (LIS-områden). Torsby: Torsby kommun.

- Trafikverket. 2021. Väghållaransvar [Online]. Accessed March 24, 2021. https://www.trafikverket.se/for-dig-i-branschen/vag/vaghallaransvar/

- Wiechmann, T., and M. Bontje. 2015. “Responding to Tough Times: Policy and Planning Strategies in Shrinking Cities.” European Planning Studies 23: 1–11. doi:10.1080/09654313.2013.820077

- Wolff, M., and T. Wiechmann. 2017. “Urban Growth and Decline: Europe’s Shrinking Cities in a Comparative Perspective 1990–2010.” European Urban and Regional Studies 25: 122–139. doi:10.1177/0969776417694680