ABSTRACT

This paper reports on a study of how TOD can contribute to sustainable development locally and regionally in sparse settlement structures. While TOD theory focuses on large cities and densely populated areas, it also tends to be applied in less populated areas. ‘Station communities’ are of great interest in Sweden, given the opportunities they apparently offer to combine economic growth through regional enlargement with decreased climate impact. This idea is, in many ways, inspired by the transit-oriented development (TOD) theory, and applied in the Västra Götaland region, aiming for regional development and increased public transportation use. The study has examined how the conditions for TOD are met in small towns with train stations located in sparse settlement structures through a case study and semi-structured interviews. The results indicate that train stations, together with planning approaches inspired by TOD theory, are regarded as important in municipal planning when identifying future developments, although the prerequisites for TOD are absent and the demand for new housing and businesses is weak. One conclusion is that a new concept is needed that does not focus on densification and urban qualities, but draws on the place qualities, where the connections to the train stations are enforced.

1. Introduction

How do you plan for sustainable transportation in sparsely populated areas? The phenomenon of regional enlargement results in more frequent and longer-distance commuting, due to enlarged labour market areas. Transit-oriented development (TOD) has been applied on the regional level, and is commonly considered a planning strategy that facilitates sustainable transport systems (Calthorpe Citation1993; Cervero and Sullivan Citation2011). Using the TOD strategy to achieve sustainable ‘regional’ enlargement is, however, problematic as TOD, which is intended for large cities and densely populated areas (Stojanovski and Kottenhoff Citation2013, 9–13) is then also used in areas with less urban characteristics (Qviström Citation2015; Qviström and Bengtsson Citation2015). Moreover, TOD planning at the regional level and its interactions with the local level, in areas with sparse settlement structures, are less explored (Staricco and Vitale Brovarone Citation2018; Hrelja et al. Citation2020).

In Sweden, the term ‘stationsnära läge’ (‘in English: station proximity location’), including TOD, has been used in regional planning (Qviström and Vicenzotti Citation2016). With one answer to sustainable and economically viable regional enlargement being ‘station communities’, i.e. places with access to public transportation, preferably trains, where it is possible to live, work, and access services, yet retain access to larger cities (Boverket Citation2012, 84). This paper aims to examine how the conditions for TOD are met in small towns with train stations located in sparse settlement structures, and how TOD is aligned with municipal planning in small towns in the case of Västra Götaland, Sweden, a region with significant variation in population density. The overarching objective is to scrutinize whether TOD can contribute to sustainable societal development locally and regionally. In the following sections, the theoretical basis of TOD is presented, after which the Västra Götaland region is described. The research methods are then presented, followed by the results of the case study. In the final section, the findings are discussed and conclusions are drawn.

2. Development, transportation, and regional enlargement

Integrating transportation and land use development at railway stations is high on the agenda in many areas (Renne, Curtis, and Bertolini Citation2009, 3–4). In Sweden, the term ‘station community’, a settlement with an existing train station, has been used when discussing TOD in several projects. This refers mainly to development around public transport that facilitates sustainable transitions, but sometimes also refers to a specific type of built-up area with urban qualities. In this section, TOD is first introduced and related to a place perspective, including how the approach has been discussed and criticized.

2.1. TOD

The station community combines what Luca Bertolini (Citation1999) describes as local place qualities and regional node qualities. Bertolini has been leading the way for method development within TOD, which since the late 1980s has discussed the interplay between transport and land use planning that arises around interchanges for public transport (Cervero Citation2007; Papa and Bertolini Citation2015; Qviström, Luka, and De Block Citation2019). In American and European contexts, a TOD is commonly described as dense and mixed-use development with relatively high density; it is pedestrian and bicycle friendly and situated near transport nodes or facilities (Cervero et al. Citation2004; Renne, Curtis, and Bertolini Citation2009; Cervero and Sullivan Citation2011; Qviström Citation2015; Staricco and Vitale Brovarone Citation2018; Thomas et al. Citation2018). TOD planning strategies are usually based on the idea that social and economic benefits will accrue from TOD implementation (Westerink et al. Citation2013; Thomas et al. Citation2018) and that TOD can be used as a strategy to achieve sustainable regional enlargement. Common goals when planning for TOD are to increase public transportation ridership, economic development, and job growth as well as to attain social goals, such as enhanced quality of life and a wider choice of housing for consumers (Cervero et al. Citation2004, 9–10; Westerink et al. Citation2013).

Although TOD and the goals of TOD planning strategies are often defined similarly by different actors, as shown above, there is no universally accepted definition of TOD, because what is considered dense, pedestrian friendly, and transit supportive varies between places (Cervero et al. Citation2004, 5). Moreover, Renne (Citation2009) suggested that TOD implementation does not always result in those characteristics. Such ‘failure’ has been termed transit-adjacent development (TAD) (Cervero et al. Citation2004; Renne Citation2009; Kamruzzaman et al. Citation2014). Renne (Citation2009) defined a TAD as an area within a 10-minute walk of a station but that, although physically near transit, lacks functional connectivity to transit since it is not as pedestrian friendly, dense, or mixed use as is stipulated for a TOD. Renne (Citation2009) also stated that most station areas fall on a spectrum ranging from TAD to TOD. TAD has been seen as problematic compared to TOD, as car usage is generally higher compared to TOD.

Thomas et al. (Citation2018) question whether TOD theory and practice is transferable between different areas and across scales. They conclude that the exact model that works in one context is unlikely to work in another, and that local planners and experts must develop their own context-specific solutions (Thomas et al. Citation2018). It has also been claimed that TOD must be specifically tailored to particular urban forms, political and planning contexts, and cultural preferences for implementation to succeed (Qviström Citation2015; Thomas et al. Citation2018). Yet, Hrelja et al. (Citation2020) identified a lack of studies trying to define TOD in peripheral or low density contexts. Therefore it is of interest to find out in what way TOD ideas can be of value in planning of sparse settlement structures, and if the planning ideas already in place could be supported by applying the TOD-concept (at least in part).

Critical research on TOD indicates that densification and density is not enough to drive sustainable development (Westerink et al. Citation2013; Qviström and Bengtsson Citation2015; Qviström, Luka, and De Block Citation2019). If relevant knowledge about a station community is not taken into account, or a more nuanced and holistic understanding of how site-specific qualities can be incorporated into the concrete planning process is lacking, then the possibilities for long-term sustainable development are limited (Qviström and Bengtsson Citation2015; Qviström, Luka, and De Block Citation2019). A focus on a radial measure of station proximity risks limiting the understanding of the more complex contexts found around a station and a more nuanced understanding of the local conditions. What Qviström, Luka, and De Block (Citation2019) demand is a relational understanding of space through which proximity to stations is developed through which more functions and heterogeneous site-specific qualities are included in the examination and how places are shaped by people’s usage of them.

In sum, previous research points to a need for the local modification of TOD implementation, though how this can be done remains unclear. This paper addresses this matter by examining how the conditions for TOD are met in small towns with train stations located in sparse settlement structures, and how TOD is aligned with municipal planning in small towns through applying a relational understanding of their spaces.

3. Setting: the region of Västra Götaland, Sweden

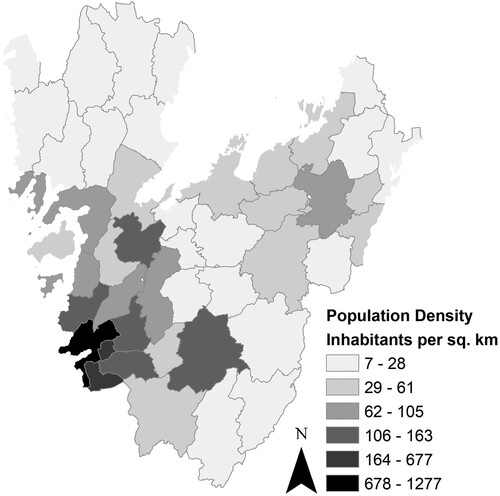

The Västra Götaland region (), home to Sweden’s second largest city (Gothenburg, with almost 580,000 inhabitants), covers 23,800 km2 (Västra Götalands län Citationn.d.). With a population of 1,725,881 (SCB Citation2020), the population density varies significantly within the region, with the highest density found in areas around Gothenburg (almost 1300 inhabitants km2) and the lowest in the northern part of the region (7 inhabitants km2; ).

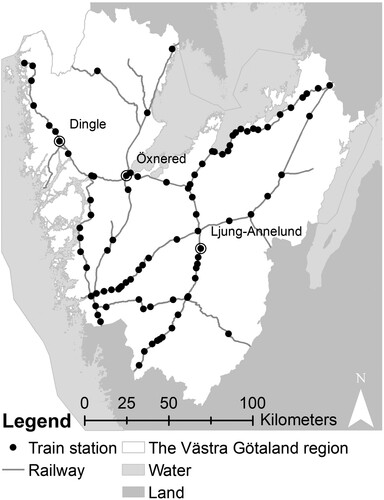

There is rail-associated infrastructure throughout the region, with several railway stations along the lines (). Most of the railway stations were established more than 70 years ago, and are found in the municipalities’ administrative centres, as well as in smaller towns with 5000 or fewer inhabitants.

Figure 3. The railway infrastructure in the Västra Götaland region. Sources: Trafikverket (Citation2017).

While Swedish municipalities are responsible for land-use planning, the national and regional levels have the responsibility for transport planning. Region Västra Götaland (VGR) is the regional authority in the Västra Götaland region responsible for public transport. VGR stresses the importance of transportation and reduced travel time for regional development, incorporating both regional enlargement and densification. As such, VGR intend to triple train travel in the region between 2006 and 2035 (VGR Citation2013, 6). One strategy for achieving regional enlargement, in which the region’s inhabitants have the opportunity to use the region’s aggregate offering of services and functions, has been to foster ‘station communities’. The idea is that when more housing and functions are concentrated at nodes on transportation routes, the prerequisites for attractive and competitive public transportation improve (VGR Citation2016, 2).

4. Methods

4.1. Case selection

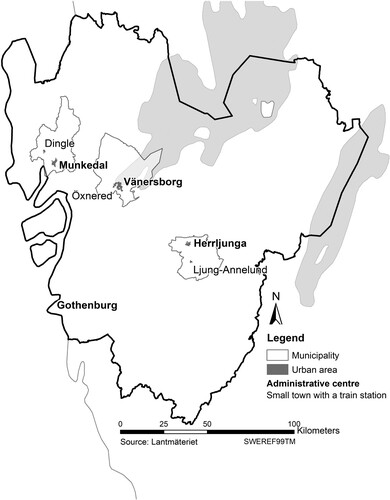

To explore how the conditions for TOD (i.e. density, mixed use, pedestrian and bicycle friendliness, and proximity to transportation nodes or transit facilities) are met in small towns with train stations in sparse settlement structures and how TOD is aligned with municipal planning in small towns, a single-case study design with multiple units of analysis (Yin Citation2018, 47–54) was chosen. The study was conducted qualitatively in the Västra Götaland region in Sweden, examining TOD related ideas in three ‘station communities’: Dingle in Munkedal municipality, Öxnered in Vänersborg municipality, and Ljung-Annelund in Herrljunga municipality ().

Figure 4. The small towns with train stations, shown in their respective municipalities with the administrative centres marked.

The populations and population densities of the studied municipalities and their administrative centres are presented in . The settlements were chosen based on the following criteria: (i) have a train station; (ii) not in the Gothenburg labour market area; (iii) under 5000 inhabitants; and (iv) not a municipal administrative centre. The justification of the criteria is that an existing train station would avoid discussion on future station communities, as is discussed in Västtågsutredningen (VGR Citation2018); avoiding the Gothenburg labour market area assures little commuting to the regional centre; and the limited number of inhabitants was to complement other cases studied in the project ‘Co-creative urban planning for energy-efficient and sustainable urban station communities’. The last criterion was set to foster discussion of municipal and sub-municipal contexts. The varied situations of the settlements allow for a rich and dynamic understanding of municipal development in settlements with a train station.

Table 1. The populations and population densities of the studied municipalities, their administrative centres, and their settlement with train station. Source: SCB (Citation2019a, Citation2019b).

4.2. Research approach

In each settlement, three one- to two-hour interviews were conducted with four or five officials and planners and with two politicians in spring 2018 (). The officials and planners were interviewed in groups; the politicians, one each from the leading and opposition parties, were interviewed individually. All interviews took place in municipal offices, except one that was conducted by phone.

Table 2. List of the interviews made in each municipality and the title(s) and role(s) of participating informants.

The interviews were structured according to the following themes:

the importance of the settlement and its role as a place

the settlement’s role as a node

‘station community’ as both place and node

future plans for and development of the settlement.

The full interview script is presented in the Appendix. The themes were developed and formulated so that it would be possible to see whether and how TOD, as a concept and strategy, was used in the municipalities.

Municipal planning documents were also examined, specifically comprehensive plans and available detailed plans for the smaller ‘station communities’. All interviews were partially transcribed, and the transcriptions, together with municipal planning documents, were organized, studied, and analysed in NVivo through the qualitative coding of the data. Categories and themes were developed from the collected empirical material, though the intention was not to compare the settlements but to provide a thicker description and understanding of the local contexts and any associated variation in the region.

When analysing the data, it was considered whether and, if so, to what extent TOD relates to the settlements in regard of the following TOD characteristics:

density

mixed use

pedestrian and bicycle friendliness

near transport nodes or transit facilities.

These characteristics were then analysed through a relational understanding of the settlements where their potential for development was discussed.

5. Results

The results from each of the settlements are presented in terms of: the situations in the municipalities and in the settlements with train stations; the municipal views of the settlements as concerned with planning and development; and the role of infrastructure and transportation in the development of these settlements. The results are presented separately to give a better contextual understanding for each settlement.

5.1. Ljung-Annelund in Herrljunga municipality

5.1.1. Setting of the settlement and its municipality

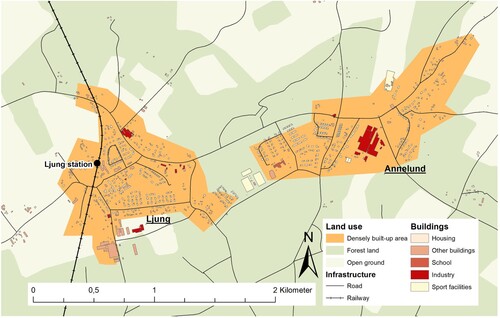

Ljung-Annelund is oblong in form with Ljung in the west and Annelund in the east; between them is a recreation area and a sports field (). The town is characterized by single-family and terraced housing. Ljung is the older part of Ljung-Annelund, with the establishment of the train station in 1863 and courthouse in 1776 (Järnvägsmuseet Citation2020; Turistrådet Västsverige Citationn.d.) accounting for its development. Annelund developed much later, in connection with the establishment of industry (Herrljunga municipality Citation2017).

Figure 5. Map of Ljung-Annelund showing the town’s oblong structure with the recreation area and sports field between the two more densely built-up areas, which include one larger and two smaller industries and a school. Source: Lantmäteriet (Citation2019).

Ljung-Annelund is the second largest town in Herrljunga municipality, in terms of both population and services. Over half of the municipality’s population live in the town of Herrljunga (the municipality’s administrative centre), and in Ljung-Annelund () (Herrljunga municipality Citation2017; SCB Citation2019b); the remainder live in smaller towns or in the countryside, with few or no services (Herrljunga municipality Citation2017). The largest economic sectors in Ljung-Annelund are farming and industry, including one large and two smaller factories (Herrljunga municipality Citation2017; interviews A and B). Ljung-Annelund provides various services: grocery stores, a petrol station, a preschool, a school for children aged 6–12 years, elderly care, a fire station, leisure services, a restaurant, and a café. For other services and functions the inhabitants of Ljung-Annelund must go to other centres, such as the town of Herrljunga or a larger town or city in another municipality. Overall, a strong local spirit supports this part of the municipality, and active associations run several functions in the town, such as sports activities and a big yearly market (interview A; Mörlanda Marknad Citationn.d.). The area’s natural values of peace and quiet, and cultural/historical values are prized and are the main reasons for people moving there.

5.1.2. Transportation

Herrljunga municipality is located centrally in the Västra Götaland region, which, according to municipal planners, is regarded as boosting its development potential. However, Herrljunga municipality lies in the outskirts of the association of local authorities (i.e. the administrative division in which strategic discussions of infrastructure investments are held) of which it is part. Herrljunga municipality is thus simultaneously in the outskirts and in the centre. Its centrality in the region is reinforced by the junction of two railway lines in the town of Herrljunga, one national line between Gothenburg and Stockholm and one regional line running north–south. Hence it is a local and regional railway junction, with the municipality describing it as a strategic location, from a regional perspective (Herrljunga municipality Citation2017; interview A).

Ljung-Annelund is an inter-municipal transportation node, having a railway station on the regional north–south line (see ). Public transport in Ljung-Annelund consists mostly of trains. Buses stop in various parts of the town, but run infrequently. It is also possible to take the bus from Annelund to the train station in Ljung, but the modes of transportation do not always interconnect. Cars are needed for longer trips since the train does not operate during the evening and night hours. Hence, car dependence is high in Ljung-Annelund (interviews A, B, and C). Maintenance of the regional railway has been neglected, meaning that trains run relatively slowly. The frequency of service is considered more important than the travel time in Ljung-Annelund, whose ‘inhabitants are not as fussy as in larger cities’, as one official put it (interview A). Functioning public transport is understood as important, as it means that young people without a driving license can stay in the town (interviews A and C), and it is seen as crucial for retaining inhabitants, who are the basis for public transport. These factors lead to prerequisites for planning public transportation and development around public transport nodes that differ from those in cities.

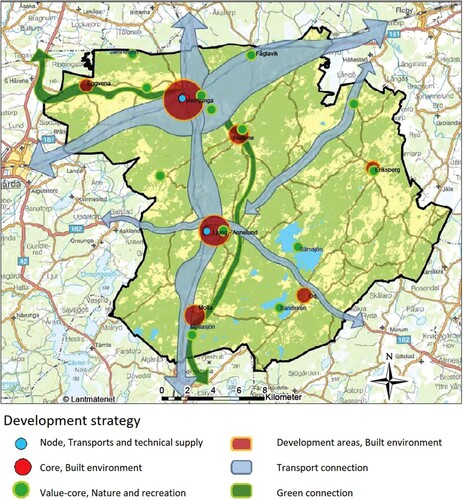

Figure 6. Herrljunga’s development strategy. Source: Herrljunga municipality (Citation2017, 13).

5.1.3. Planning

The municipal plan is to develop Ljung-Annelund by adding 100 housing units by 2035 (Herrljunga municipality Citation2017, 21). This is a somewhat optimistic goal, since the population of Ljung-Annelund decreased by about 2% from 2010 to 2018 (SCB Citation2019b). According to the municipal planning documents, the railway is among the most important prerequisites for the municipality’s long-term development, and a sustainable lifestyle could be promoted by effectively using the municipality’s good location with the railway station in Herrljunga (Herrljunga municipality Citation2017). The idea of a ‘station community’ is presented as a model, highlighting the ambition that it should be convenient and safe to travel on foot or by bike in all towns in the municipality (Herrljunga municipality Citation2017).

The town of Herrljunga is a top priority for municipal development and is expected to grow more and faster than Ljung-Annelund (interview A). The municipality’s long-term traffic strategy calls for infrastructure for sustainable travel to be developed locally and regionally, and the recommendation is to strengthen both towns’ functions as travel centres (Herrljunga municipality Citation2017, 17). The towns’ railway stations are clearly important for municipal planning, and the comprehensive plan states:

Herrljunga and Ljung-Annelund will be developed as ‘station communities’ with dense and mixed cores. The starting point for the planning is that residential buildings that are added in the towns should preferably lie within walking and biking distance of the stations. (Herrljunga municipality Citation2017, 21)

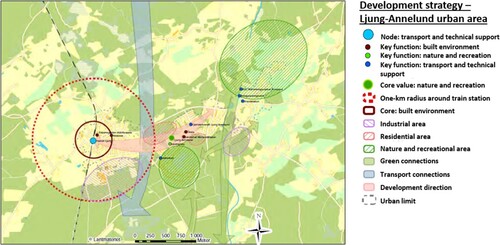

Figure 7. Ljung-Annelund in the municipal comprehensive plan, with circles around the town centre and train station. Note the 1-km-radius area around the train station (dotted circle). Source: Herrljunga municipality (Citation2017, 71).

An important starting point for planning in Herrljunga is its proximity to the station and to services in the town core. In Ljung-Annelund, the station is significant to planners, but it is also considered important that the two towns should grow together (interview A). Complementary new development and densification on land within the small town have been prioritized, especially in areas that can tie the two parts of the town together, on the outskirts, and in connection with the station area west of the railway. Ljung-Annelund’s natural qualities are to be preserved, and the development should be aligned with the priorities of the small town. In the future, it might be possible to build some taller buildings of two, three, or maybe four storeys (interview C).

A difficulty in developing Ljung-Annelund is the low demand for new housing (interview A). Another is that even though the cost of building a new house is the same in a small town as in a larger city, banks do not approve the same-sized loans in smaller towns such as Ljung-Annelund (interview B). The planners and officials say that the issue of demand is challenging to address, since demand is difficult to influence and modify (interview A).

5.2. Dingle in Munkedal municipality

5.2.1. Setting of the settlement and its municipality

Dingle is a fairly young settlement, built and developed around a junction between the road and the railway when the station opened in 1903 (Karlsson Citation2008, February 26). The town is described as a community surrounded by farmland and forests, and also as a town with committed inhabitants and entrepreneurship (interviews D, E, and F). Dingle has been characterized by agricultural industries, though several newly established space-demanding and transport-dependent businesses have put a new mark on the town and its surroundings (Munkedal municipality Citation2017). Central Dingle lies at the southern end of a valley extending northwards, with buildings climbing a hillside to the east and industrial development on the plain to the south-west. Many of the buildings in central Dingle were developed in connection with the station, but the significance of the station, situated on the eastern hillside, has decreased. Kunskapens hus (Eng. The Knowledge House) is a centre that offers various adult education and training programmes. This new facility is on the former site of a school of land management and agriculture, which once was the most notable feature of Dingle in its regional context. European route E6 formerly went through Dingle, but has been relocated west of the town (Munkedal municipality Citation2017).

The town of Munkedal is the municipality’s administrative centre (Munkedal municipality Citation2017). The most important issue regarding the development of the municipality’s hinterland is population growth to provide a stronger basis for local services for both smaller towns and the administrative centre (Munkedal municipality Citation2017). It is important for the municipality to keep the town of Munkedal as a service centre, since this is seen as a prerequisite for developing the municipality and countryside (Munkedal municipality Citation2017, 28). Dingle provides services for its hinterland. These services include: a grocery store, postal service, a preschool, a school for children aged 6–12 years, a home for the elderly, a petrol station, garages, and healthcare. There are other sources of employment, such as hairdressers, one large company and several smaller ones, and several restaurants (especially pizzerias); there are leisure facilities, such as a library, sport facilities, and a youth recreation centre (interviews D, E and F; Munkedal municipality Citation2018). For other services and functions the inhabitants of Dingle must go to other nearby centres, such as Munkedal, or larger towns or cities in other municipalities.

5.2.2. Transportation

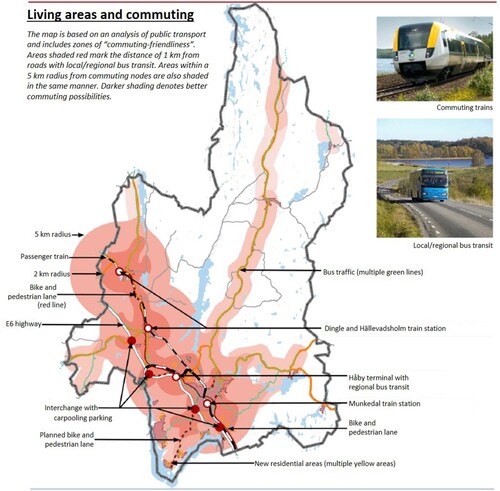

Regional commuting is important for Munkedal municipality, as it means better opportunities to recruit qualified workers and access other labour markets (interviews D and F). There are good transportation connections through access to the motorway and railway, offering potential for trade, logistics, and tourism (Munkedal municipality Citation2017; see ). The municipality is sparsely populated. The main mode of transportation is the car (Munkedal municipality Citation2017, 28; interviews D, E, and F), which is seen as faster and more convenient than other modes (interviews D, E, and F). Even though the railway gives the municipality access to larger cities, there are few departures from Dingle, and the railway’s poor condition makes travel between Munkedal and Gothenburg 50 min slower by train than by car (interviews D and E).

Figure 8. Munkedal’s strategy for housing and commuting. Source: Munkedal municipality (Citation2017, 12).

5.2.3. Planning

According to Munkedal municipality there is a need to develop rental housing in its towns, to allow inhabitants of all ages to stay in the municipality, as it is crucial for the municipality to stop its population decline (Munkedal municipality Citation2017). Moreover, new housing development should be located primarily to facilitate coordination of the installation of utilities (i.e. water and sewage) and so that public transport can be developed and utilized. New housing should preferably be built near existing towns and cities, to constitute a natural supplement to existing buildings, but the municipality is also open for more single homes in the countryside (Munkedal municipality Citation2017, 35). According to the comprehensive plan, housing development in Dingle should occur through densification of the central areas and through new development eastwards, where there are good opportunities for attractive housing sites on a hillside (Munkedal municipality Citation2017, 41).

From a municipal planning perspective, the railway is important for Dingle even though the significance of the train station and railway has decreased. The Dingle station area can be said to lie on the ‘wrong side’ of most of the built-up area, and the accessibility of the station could be improved (interview D). The municipality prizes its location and natural values (i.e. open landscape, lakes, forests, and scenic topography) and the social values connected with associations that foster community engagement (interviews D, E, and F). There are several vacant housing lots in the town, indicating low housing demand, although there are plans to build a home for the elderly and the Kunskapens hus was recently completed (Munkedal municipality Citation2017, Citation2018).

The comprehensive plan articulates a general strategy for the public transportation system, i.e. to decrease travel time within the municipality (Munkedal municipality Citation2017, 20). Eventually it should be possible to develop fast commuting from Dingle and three other towns/settlements to the two larger municipal centres, Munkedal and Håby (Munkedal municipality Citation2017, 20). A map () based on an analysis of public transportation presented in the comprehensive plan shows ‘commuter-friendly’ zones for public transportation, with darker colours indicating assumed better commuting conditions (Munkedal municipality Citation2017, 12). The timeframe considered in the commuting analysis is 10–15 min, representing about 1 km by foot, 2 km by bike, and 10 km by car (or a radius of 5 km) (Munkedal municipality Citation2017, 12). There are some issues when it comes to the comparability of measures defining locations near commuter nodes and areas with conditions for commuting partially or entirely by public transport.

According to the municipality, commuting is seen from a regional rather than municipal perspective, and municipal public transportation is nearly nonexistent. The municipality also assumes that the main means of regional commuting is via a combination of car and other transportation modes from one of the nodes. When it comes to the railway, the focus is on the town of Munkedal, not on Dingle. Politicians and planners want to develop and improve the railway incrementally, starting in Munkedal before addressing Dingle, which is why the Dingle service remains poor (interviews D and F). In addition, there is a missing link between train and bus in Dingle, as they do not stop in the same place.

5.3. Öxnered in Vänersborg municipality

5.3.1. Setting of the settlement and its municipality

Öxnered differs from Ljung-Annelund and Dingle in that the village lies closer to the municipal administrative centre, to which it is possible to bike within 20 min. Öxnered is not considered a separate village in Vänersborg municipal planning; rather, Öxnered is treated as a district of the municipality’s main city of Vänersborg (interviews G and H). Öxnered is at a junction where the north–south and east–west railways cross. This junction was the reason for Öxnered’s development, with a train station being established in 1878 (Sandberg Citation2018). This settlement is today characterized by its train station, nearness to nature, and proximity to the main city of Vänersborg. Öxnered’s buildings are mostly housing, mainly single-family housing, with some duplexes and apartment buildings, with a daytime population that is small (interviews G, H, and I; field study).

Vänersborg municipality is the largest municipality examined here, and its biggest city is Vänersborg (SCB Citation2019b; Vänersborg municipality Citationn.d.). About 10,000 of the municipality’s inhabitants live in smaller towns or in the countryside. In Öxnered there is: a preschool, a school for children aged 6–12 years, home services, some employment in the municipal sector, several small private companies, a small shop (no groceries), a pizzeria, a car repair shop, a carpentry workshop, craftsmen, entrepreneurs, and sheltered housing (interviews G, H, and I; field study). There is no longer a village centre in Öxnered with shops and services, though the old station building provides a link to the past, when the station was the centre of the community.

5.3.2. Transportation

There are transportation routes in all directions to and from Öxnered, via roads and railways accessible by car, bus, or train. The train to Gothenburg is of considerable importance for Öxnered itself, as well as for Vänersborg municipality. In the regional context, Öxnered is a public transport node thanks to its train station, used either for commuting or changing trains. Moreover, people in adjacent municipalities find it convenient to drive to Öxnered to catch the train to Gothenburg, making Öxnered station important in the sub-regional context as well. Öxnered is connected to several labour market areas, so one can live there and still work in a variety of professions. However, not all these labour market areas are accessible by train, so the car is the foremost mode of travel, making for car dependency in Öxnered, as in the other two cases (interviews G and I).

5.3.3. Planning

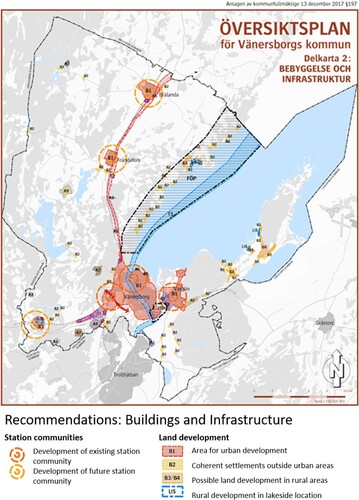

According to municipal planners and officials, the railway is necessary if Öxnered is to develop, but it is not required for Öxnered’s existence (interview G). From a longer-term perspective, it is a municipal ambition to develop Öxnered into an important node in the Trestad area (i.e. Trollhättan, Uddevalla, and Vänersborg). One idea is that if a commuting system is set up in Trestad, Öxnered will become one of its important central transportation nodes (interview G). So far, Öxnered has been more of a transportation node than a ‘station community’ (interviews G and H), yet there are more concrete plans for the Öxnered area than for the other settlements studied here. Öxnered’s location near the city of Vänersborg should facilitate its development, as it offers commuting possibilities as well as proximity to lakes and the city (interviews G, H, and I; Vänersborg municipality Citation2017b, 97).

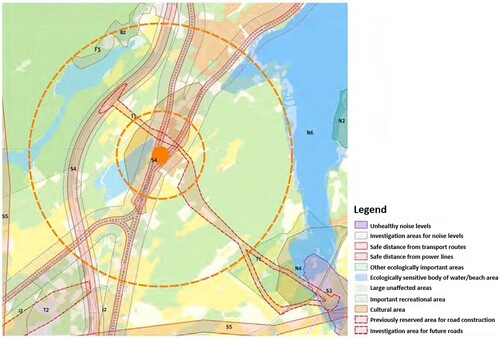

The comprehensive plan of Vänersborg municipality articulates the development principle of ‘developing existing and new “station communities”’, and a map from the plan () shows such ‘station communities’, including Öxnered, as circles (Vänersborg municipality Citation2017b, 97). In these areas, the plan recommends that land around existing train stations and tracks be reserved for the development of ‘station communities’ (Vänersborg municipality Citation2017b). Accessibility by bike and public transportation is central to this plan. Land should be reserved for commuter parking lots and new urban cores, should they develop. Planning should allow for the construction of a great deal of housing within walking and cycling distance of the stations (Vänersborg municipality Citation2017b, 70).

Figure 9. Map of existing and future ‘station communities’ in Vänersborg municipality. Source: Vänersborg municipality (Citation2017b).

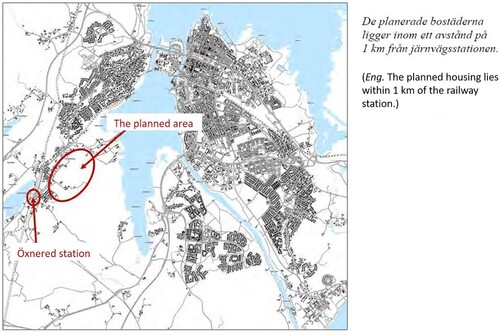

A detailed development plan has been decided on (Vänersborg municipality Citation2017a), which calls for building housing ‘close to nature’ on previously undeveloped land near Öxnered train station (). Nevertheless, the zones or circles drawn in the comprehensive and detailed plans ( and ) are not seen in the final version of the plan for the new development of about 600 housing units in Öxnered, as the area is located north-east of the train station ().

Figure 10. Location of planned new housing, within one km of the train station. Source: Vänersborg municipality (Citation2017a).

Figure 11. Visualization of Öxnered and the principle of developing existing and new ‘station communities’. Source: Vänersborg municipality (Citation2012, 5).

Clearly, Öxnered is being actively planned as a locus for development in the municipality and is part of the development of the municipality’s main city of Vänersborg. The future planning of Öxnered is therefore concentrating on new housing, expanded services, including a small grocery store, and ongoing transportation improvement. The demand for new housing in the municipality is strong (Vänersborg municipality Citation2017a, n.d.), but not all inhabitants of Öxnered favour densification, which planners are trying to facilitate near the train station (interview G). However, it was noted that it is important to assess and maintain the attractiveness of Öxnered, which includes preserving its tranquillity, even though it is near the city of Vänersborg (interview G).

6. Discussion

6.1. The settlements in relation to TOD

Dingle, Öxnered, and Ljung-Annelund are considered important in the municipal context as they provide services for their surrounding areas, but they lack the prerequisites for TOD as a specific type of built-up area in terms of high density and mixed use (e.g. Cervero et al. Citation2004; Renne, Curtis, and Bertolini Citation2009; Cervero and Sullivan Citation2011). Instead, this study has identified seven partly overlapping characteristics and features of these communities that are inconsistent with TOD:

Low population density, low-rise buildings, with train stations not centrally located

Low demand for (new) housing

High car dependency

Poor condition of railway

Resistance of inhabitants and local authorities to higher housing density

Small daytime population

Importance of preserving natural values.

All three settlements are of low population density with low-rise buildings, and the train stations are not centrally located. Low demand for (new) housing is a critical issue. The demand is weak in Ljung-Annelund and Dingle, while it is stronger in Öxnered, where trains departing for Gothenburg every 45 min make the town attractive for developers. The results indicate high car dependency, since the car is the most important mode of transportation in all three settlements. Longer travel times by train than by car and/or infrequent train departures are issues in Ljung-Annelund and Dingle. The poor condition of the railway tracks means that the trips take longer, and the infrequent train departures, especially from Dingle with easy access to the motorway, are hindrances when choosing travel mode. This is not seen as an issue in Öxnered, which is near the municipal administrative centre and where the train departure frequency is high. Inhabitants and local authorities are resistant to higher housing density in the studied towns, most obviously in Öxnered, where inhabitants have protested densification around the train station.

The daytime populations are small, and the lack of services and functions in the three settlements means that these settlements cannot be classified as mixed use. As for Öxnered, there are also few workplaces, and the dominance of housing strengthens the incoherence of implementing TOD given the prerequisite of mixed use. Since the settlements are small there are no difficulties moving around by foot or bike; however, the benefits of density and a variety of services and functions around the train stations are absent. In all cases, the importance of preserving natural values is mentioned and given a greater emphasis than in placeswhere TOD is commonly implemented (interviews A, B, C, D, E, F, and G).

6.2. Municipal planning of settlements in relation to TOD

Despite the three settlements lack of TOD characteristics, the planners in each municipality marked TOD-inspired development zones in their comprehensive plans in areas near train stations. The maps show that areas near train stations are a priority in municipal development. The zones around the train stations in Ljung-Annelund and Öxnered have the train station in the centre, although existing built-up areas display a different structure, and the zones in Munkedal are instead based on distance and time. A problem with these zones is that they do not correspond either to the actual distances from the station that people experience, or to the actual time it would take to go to or from the train station. In several municipal documents, maps show the typical ‘station community’ pattern with the train station in the centre. If using a 1-km-radius circle, which is the case for the studied settlements, one should consider that this does not take account of road locations or sizes.

Aside from the fact that it matters how the zones are defined, the main problem in these cases is lack of reflection on what the zones currently mean and what they will imply later in the planning process. In the case of Öxnered, new housing is positioned close to natural sites and water – understood as equally important factors when locating new development in Öxnered – instead of near the train station. Looking at Ljung-Annelund, it is clear that existing built-up areas are all located east of the station, while this was not considered when circles were drawn with the station in the centre in municipal planning documents.

Although densification is spoken of in all cases, this diverges from TOD theory. Added to that, in the three settlements densification means more housing, but not necessarily higher buildings or more offices, services, or functions, making mixed-use development seem a remote possibility. As TOD implementation must be specific to particular urban forms, planning contexts, and cultural preferences (Qviström Citation2015; Thomas et al. Citation2018), the case characteristics identified here must be considered before trying to implement a strategy – i.e. TOD – developed in a quite different context. Hence, the idea of relational understanding of place (Qviström, Luka, and De Block Citation2019) could be useful in developing the settlments in a more sustainable direction by partly applying the TOD-concept. To completely dismiss TOD as a planning concept could be difficult in these settlements, as there are planning ideas already in place that could be supported by the TOD-concept, although it is in need of adjustment and contextual adaptation.

6.3. Interface: local planning in the regional context

As argued in the introduction, common goals of TOD are to increase public transportation ridership, economic development, and job growth as well as to pursue social goals such as enhanced quality of life and a wider choice of housing for consumers (Cervero et al. Citation2004; Westerink et al. Citation2013). These goals are similar to those set for the Västra Götaland region. If a theory, such as TOD, inspires regional strategies and the associated municipal planning strategies, such as ‘station communities’ in this case, it is important to note when it does or does not work in all localities.

The results indicate that TOD has influenced municipal plans and strategies in relation to settlements with train stations, as well as on a larger municipal scale, which supports the conclusions of Qviström (Citation2015). Although TOD theory inspired the studied municipal plans (intentionally or unintentionally), the municipalities are aware that these ideas must be adapted to local conditions. Other than that, however, the findings reveal a scarcity of reflection on the extent to which TOD ideas have influenced the plans, and on the possible implications of this. Dingle and Ljung-Annelund are secondary to their municipalities’ administrative centres. In Munkedal municipality, the focus is on the municipal administrative centre because it is at risk of losing its services and functions. Keeping the town of Munkedal as the municipality’s service centre is important to the municipality, thus Dingle is secondary. Herrljunga municipality focuses on its administrative centre because of its role as a railway junction, while Ljung-Annelund is merely a node on a smaller railway line. Öxnered has a clearer role in the regional context, compared with that of Dingle or Ljung-Annelund, thanks to its role as a railway junction. Öxnered offers a wider range of train services and the train to Gothenburg takes just 45 min, so one can live in Öxnered and work in the region’s largest city. Additionally, Öxnered is seen as part of the city of Vänersborg, the municipality’s administrative centre, hence development in Öxnered is also understood as development of the municipality’s main city.

Since TOD, as referring to a built-up area with significant urban characteristics, is inapplicable in the studied settlements, should TOD theory really guide their development? TOD theory was not developed for sparsely populated areas or for sparse settlement structures. Although TOD therefore could be regarded as inapplicable in these settlements, this does not mean that these communities lack development potential in their areas. Rather, these settlements exemplify places where municipalities would like to see development, but are stymied in various ways. Therefore there is a need for ideas on how to do this, for example by adopting a relational understanding (Qviström, Luka, and De Block Citation2019) of the places when adjusting the TOD-inspired plans. If TOD were made the goal in these places, failure to realize it could be seen as the ‘failure of TOD’, as the outcomes would probably instead resemble small-scale forms of TAD. However, an informed adaptation of the concept to the local conditions could be beneficial and helpful in planning for sustatinable transportation locally and regionally.

At the regional level, it is important to understand that if TOD is used as a regional development strategy for developing ‘station communities’ to facilitate sustainable transitions, the development of settlements will largely fail where the towns lack TOD characteristics, as this case study shows. Moreover, the failed development of settlements with train stations will in turn affect regional development as a whole, as it will not lead to the intended social and economic benefits as outlined by Thomas et al. (Citation2018).

6.4. Alternative concepts for sparse settlement structures

Following the reasoning above, it is important to distinguish between a ‘station community’ and a town with a train station. A ‘station community’ is not necessarily a form of TOD, but the concept echoes the meaning of TOD or evokes TOD-like characteristics and implications (Qviström and Vicenzotti Citation2016). As the TOD literature states (Cervero et al. Citation2004; Qviström Citation2015; Staricco and Vitale Brovarone Citation2018; Thomas et al. Citation2018), a public transportation station is only part of what constitutes TOD, while smaller settlements, like the three studied here, lack dense, mixed-use, or pedestrian-friendly settlement structures. Recalling the ideas of Qviström (Citation2015), the intentional or unintentional incorporation of ideas related to TOD means that municipalities having small towns with train stations seem to be aiming at TOD-like development, although its prerequisites are lacking. Urban values, as described in the TOD literature, are an established idea seen as the ultimate result of TOD. This should be problematized: not the idea or theory of TOD per se, but the uncritical implementation of TOD in plans for settlements with train stations that lack the prerequisites for TOD. In line with Thomas et al. (Citation2018), who stated that local planners and experts must develop their own context-specific solutions, the lack of reflection on what would be likely and/or suitable for settlements with train stations in the context of sparse settlement structures should be addressed. Additionally, how the settlements could be developed, if not in terms of TOD, merits discussion. One idea would be to explore whether a form of TAD or something on the TOD–TAD spectrum (Renne Citation2009) might be a better fit in these locations. Drawing on the place qualities, through a relational understanding of the settlements where the connections to the train stations are enforced, could work in sparse settlement structures. Approaching the TAD-end of the spectrum, through a focus on place qualities that would bring positive connotations (instead of a TOD- failure approach), could be a way forward as the TOD-inspired ideas are already in place.

If neither TOD nor the ‘station community’ concept is applicable in the studied settlements, what should guide their planning? Since the train stations are in place with running traffic, it is logical to want to keep and enforce this connection within the planning of the settlements. However, how to incorporate the station is dependent on site-specific qualities, and a holistic understanding of the settlements and their location municipally and regionally. A shared regional and municipal planning strategy might articulate a version of TOD tailored to the context of small towns within sparse settlement structures. Another alternative is to regard TAD as a possibility in its own right and not as ‘failed’ or weak TOD. TAD is physically near transit but lacks functional connectivity to transit because it is not as pedestrian friendly or dense with mixed uses as is TOD. The criticism of higher car usage in TAD than in TOD also recalls the situation of the studied settlements. However, these cases should not be seen as possible failures of or weak realizations of TOD. Rather, a focus on the place qualities is needed that take into account the local prerequisites when TOD, at a regional level, is intended in order to foster sustainable transitions. If TOD as a strategy, and TOD as referring to a certain built-up area, could be distinguished more clearly, it could advance the development of sparsely populated regions, such as smaller towns and villages (with train stations) unsuited for densification, while seeing the train stations as offering potential for local and municipal development and sustainable transitions.

Furthermore, when integrating the location of central functions through planning, there is always a tension between an economic criterion (e.g. thresholds and viability, through the frequency of use) and a social criterion (e.g. range, or the maximum distance that someone must travel to access a central function). Given the challenges of regional sustainability, public policy could more strongly consider the social criterion to the detriment of the economic criterion. This could be useful, especially since this change of policy might bring economic and social benefits (e.g. population attraction, attraction and retention of talent, viability of existing equipment, and deepening the centrality of the territory) in the longer term to low density territories which, without this concern, may possibly end up bringing global economic costs difficult to deal with later.

7. Conclusions

This paper has analysed the extent to which TOD ideas relate to conditions in sparse settlement structures and whether TOD can contribute to sustainable societal development locally and regionally. So how can you plan for sustainable transportation in sparsely populated areas? The results indicate that the studied settlements are not aligned with TOD characteristics as they are neither dense nor mixed use, hence not as pedestrian or bicycle friendly, nor as near transport nodes or transit facilities as TOD requires. Instead, seven characteristics and features inconsistent with TOD were detected. Yet, one conclusion is that TOD influenced municipal planning work in these settlements, whether intentionally or unintentionally, though it should not be seen as the only approach or planning strategy for small towns with train stations.

Another conclusion is that not every town with a train station can be called a ‘station community’, especially not if this implies TOD as referring to a certain built-up area. Given local development prerequisites, critical questioning is needed regarding the type of development to be planned for in the specific contexts of settlements with train stations. Densification and other urban values seem to be mainstream in planning, but the purpose of a train station can differ between a small town in a sparse settlement structure and a TOD in a metropolitan area. I therefore advocate further studies of how regional planning could support the sustainable development of smaller settlements with train stations. A more nuanced definition of the TOD concept is needed in which TOD as a regional strategy and TOD as referring to a certain built-up area are differentiated, and not always necessarily connected.

Additionally, a new concept is needed for the development of small towns and villages with train stations that suits their prerequisites, and that does not advocate densification and urban qualities as goals in themselves – perhaps something like a small-scale TAD – where the idea is to provide public transportation and services while also providing a variety of living options at the regional level. This could include public policy which more strongly considers the social criterion to the detriment of the economic criterion. A change of policy might bring economic and social benefits in the longer term to low density territories which, without this concern, might end up bringing global economic costs difficult to deal with later. Therefore, striving for sustainable regional enlargement through regional planning should be better harmonized with local prerequisites, as regional decisions affect local plans.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bertolini, L. 1999. “Spatial Development Patterns and Public Transport: The Application of an Analytical Model in the Netherlands.” Planning, Practice & Research 14 (2): 199–210. doi:10.1080/02697459915724.

- Boverket. 2012. Vision för Sverige 2025. Karlskrona: Boverket.

- Calthorpe, P. 1993. The Next American Metropolis: Ecology, Community, and the American Dream. New York: Princeton Architectural Press.

- Cervero, R. 2007. “Transit-oriented Development's Ridership Bonus: A Product of Self-Selection and Public Policies.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 39 (9): 2068–2085. doi:10.1068/a38377

- Cervero, R., S. Murphy, C. Ferrell, N. Goguts, T. Yu-Hsin, G. Arrington, J. Boroski, et al. 2004. Transit-Oriented Development in the United States: Experiences, Challenges and Prospects—TCRP Report 102. Washington, DC: Transportation Research Board.

- Cervero, R., and C. Sullivan. 2011. “Green TODs: Marrying Transit-oriented Development and Green Urbanism.” International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology 18 (3): 210–218. doi:10.1080/13504509.2011.570801.

- Herrljunga municipality. 2017. Översiktsplan för Herrljunga kommun.

- Hrelja, R., L. Olsson, F. Pettersson-Löfstedt, and T. Rye. 2020. Transit Oriented Development Literature Review. (K2 research 2020:2) K2. https://www.k2centrum.se/sites/default/files/fields/field_uppladdad_rapport/k2_research_2020_2_0.pdf.

- Järnvägsmuseet. 2020. Vy vid Ljung. Station från 1863. Identifier: JvmKDAD00046. Accessed April 6, 2020. https://digitaltmuseum.se/021018162820/vy-vid-ljung-station-fran-1863-trastationshus-i-tva-vaningar-1924-nytt.

- Kamruzzaman, M., L. Wood, J. Hine, G. Currie, B. Giles-Corti, and G. Turrell. 2014. “Patterns of Social Capital Associated with Transit Oriented Development.” Journal of Transport Geography 35 (C): 144–155. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2014.02.003.

- Karlsson, S. 2008. Dingle station blir inte byggnadsminnesförklarat. BOHUSLÄNINGEN, February 26. https://archive.is/20120525144139/http://212.3.11.251/artikel_pm_standard.php?id=360747&avdelning_1=101&avdelning_2=105&avdelning_3=0.

- Lantmäteriet. 20119. GSD-Property Map, Vector.

- Mörlanda Marknad. n.d. Mörlanda marknad genom tiderna. Accessed June 1, 2020. https://morlandamarknad.com/historik/.

- Munkedal municipality. 2017. Framtidsplan ÖP18 Munkedal – del 1 Strategier och förslag. Samrådshandling.

- Munkedal municipality. 2018. Lediga tomter i Dingle. Accessed May 21, 2019. https://www.munkedal.se/bygga-bo-och-miljo/bostader-och-offentliga-lokaler/lediga-fastigheter-och-tomter/dingle.

- Papa, E., and L. Bertolini. 2015. “Accessibility and Transit-Oriented Development in European Metropolitan Areas.” Journal of Transport Geography 47: 70–83. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2015.07.003

- Qviström, M. 2015. “Putting Accessibility in Place: A Relational Reading of Accessibility in Policies for Transit-oriented Development.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 58: 166–173. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2014.11.007

- Qviström, M., and J. Bengtsson. 2015. “What Kind of Transit-Oriented Development? Using Planning History to Differentiate a Model for Sustainable Development.” European Planning Studies 23 (12): 2516–2534. doi:10.1080/09654313.2015.1016900

- Qviström, M., N. Luka, and G. De Block. 2019. “Beyond Circular Thinking: Geographies of Transit-Oriented Development.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 43 (4): 786–793. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12798

- Qviström, M., and V. Vicenzotti. 2016. Urban sprawl på skånska?. Fakulteten för landskapsarkitektur, trädgårds- och växtproduktionsvetenskap.

- Renne, J. 2009. “From Transit-Adjacent to Transit-oriented Development.” Local Environment 14 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1080/13549830802522376

- Renne, J., C. Curtis, and L. Bertolini. 2009. Transit Oriented Development: Making It Happen [Elektronisk resurs]. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Group.

- Sandberg, Ola. 2018. Öxnereds Stationshus.

- SCB. 2019a. Befolkningstäthet (Invånare per kvadratkilometer efter kommun och år). Accessed February 13, 2020. http://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/sv/ssd/START__BE__BE0101__BE0101C/BefArealTathetKon/table/tableViewLayout1/.

- SCB. 2019b. Tätorter 2015; befolkning 2010–2018, landareal, andel som överlappas av fritidshusområden. www.scb.se/MI0810. Publicerad 2019-03-28.

- SCB. 2020. Folkmängd i riket, län och kommuner 31 december 2019 och befolkningsförändringar 1 oktober–31 december 2019. Totalt. Accessed April 2, 2020. https://www.scb.se/hitta-statistik/statistik-efter-amne/befolkning/befolkningens-sammansattning/befolkningsstatistik/pong/tabell-och-diagram/kvartals–och-halvarsstatistik–kommun-lan-och-riket/kvartal-4-2019/.

- Staricco, L., and E. Vitale Brovarone. 2018. “Promoting TOD Through Regional Planning. A Comparative Analysis of Two European Approaches.” Journal of Transport Geography 66: 45–52. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2017.11.011.

- Stojanovski, T., and K. Kottenhoff. 2013. Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) och Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) - Stadsutveckling för effektiv kollektivtrafik: Erfarenheter från Sverige och andra länder - Vilka krav ställer BRT på bebyggelsen? - Hur kan svenska städer anpassas för BRT?

- Thomas, R., D. Pojani, S. Lenferink, L. Bertolini, D. Stead, and E. Van Der Krabben. 2018. “Is Transit-oriented Development (TOD) an Internationally Transferable Policy Concept?” Regional Studies 52 (9): 1201–1213. doi:10.1080/00343404.2018.1428740.

- Trafikverket. 2017. Sverige järnvägsnät.

- Turistrådet Västsverige. n.d. Gäsene Tingshus Ljung, Herrljunga. Accessed April 6, 2020. https://www.vastsverige.com/herrljunga/produkter/gasene-tingshus/.

- Vänersborg municipality. 2012. PROGRAM för Detaljplaner för Skaven och delar av Öxnered Vänersborg municipality. Revised in July 2016.

- Vänersborg municipality. 2017a. Detaljplan för Skaven och del av Öxnered Vänersborgs kommun Miljö- och byggnadsförvaltningen. Revised in March 2019.

- Vänersborg municipality. 2017b. Översiktsplan 2017.

- Vänersborg municipality. n.d. Om Vänersborg. Accessed May 24, 2019. http://www.vanersborg.se/kommun–politik/press–och-informationsmaterial/informationsmaterial/om-vanersborg.html.

- Västra Götalands län. n.d. In Nationalencyklopedin. Accessed April 6, 2020. https://www-ne-se.ezproxy.ub.gu.se/uppslagsverk/encyklopedi/l%C3%A5ng/v%C3%A4stra-g%C3%B6talands-l%C3%A4n.

- VGR. 2013. Målbild Tåg 2035 – utveckling av tågtrafiken i Västra Götaland.

- VGR. 2016. Regionalt trafikförsörjningsprogram Västra Götaland. Programperiod 2017-2020 med långsiktig utblick till 2035. Vänersborg: Västra Götalandsregionen.

- VGR. 2018. Västtågsutredningen huvudrapport - en komplettering av Målbild Tåg 2035 med nya stationer.

- Westerink, J., D. Haase, A. Bauer, J. Ravetz, F. Jarrige, and C. Aalbers. 2013. “Dealing with Sustainability Trade-Offs of the Compact City in Peri-Urban Planning Across European City Regions.” European Planning Studies 21 (4): 473–497. doi:10.1080/09654313.2012.722927

- Yin, R. 2018. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods. 6th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Interview A Herrljunga planners and officials.

- Interview B Herrljunga politician, Political opposition.

- Interview C Herrljunga politician, Ruling party.

- Interview D Munkedal planners and officials.

- Interview E Munkedal politician, Political opposition.

- Interview F Munkedal politician, Ruling party.

- Interview G Vänersborg planners and officials.

- Interview H Vänersborg politician, Ruling party.

- Interview I Vänersborg politician, Political opposition.