ABSTRACT

In this article four main things are done. First, the difference between ‘disaster preparedness’ and the established field of ‘disaster planning’ is denoted. The latter, confusingly, is seen as post hoc aftermath response rather than prepared forethought. Second, there is a discussion about the similarities between ‘disaster clean-up’ in Roman times which was extorted as taxation from the poor to subsidize the rich and neo-liberal taxation policy in today’s advanced economies, which similarly expropriate the poor to enable the rich to extort more wealth at the poor’s expense. Third, we explore some weaknesses of ostensibly ‘green’ policy-making, which betrays traits of narcissism, egotism and vanity which should be avoided at all costs because they occasion failure and further raids on the taxpayer base in many cases. Finally, 10 papers are introduced, ranging from varieties of ‘circular City’, to rainfall harvesting, green space accounting and transition to wooden construction and revitalization of urban shrinkage settings.

Introduction

At EPS we had sought for many years to find a way into a crucial subject which ought to have been of central importance to urban and regional planners but on which they had been surprisingly silent. The subject, I had learnt by searching, was known as ‘Disaster Planning’ of the kind that specialist journals covered in the aftermath of storms, floods, fires and earthquakes, for example (Kyne Citation2020; Raikes Citation2019; van Berlaer et al. Citation2017). Each of these sample articles focused largely on the post facto disaster aftermath, crisis management or its absence. Possibly, as planners, our community was both more optimistic, design and future-oriented than the ‘collapse’ narrative associated with seemingly unpredictable catastrophes and the remediation implied by such shocking fragility. But ‘anticipation’ was surely built into the planner’s toolbox too? So at the behest of the EPS Global Head of Portfolio, Jonathan Manley, keen to repeat the success of EPS’ ‘25-Year Anniversary’ Special Issue in 2018 (Cooke Citation2018), we embark on this 30-year Jubilee Special issue. Whereas the previous commemoration was subtitled ‘from a new Dark Age to a new dawn of planning enlightenment’, this one possibly, hopefully marks a new low in ‘the darkness before dawn’. After recent years by relentless incremental increases in ‘global warming’ a narrative of ‘global heating’ is now becoming normal. The regular occurrence of albeit sporadic but huge and fatal conflagrations in flammable pine forests, the 22-year droughts in large swathes of the increasingly desertified marginal lands of all bar Antarctica, and the increased incidence of lethal floods brought by cloudbursts of biblical magnitude to valley confluences point to new priorities for planners to dust-off their tools for anticipatory action. To these must be added the increasing and highly lethal occurrence of successive pandemics, caused like Covid-19 by globalization encroaching upon the natural habitats of wild animals and insects. To which has to be added the first significant war in Europe occasioned by Vladimir Putin’s military invasion of Russia’s neighbouring state of Ukraine. Thus fossil energy dependence gave the autocrat what sociologists call ‘pure agency’ to hold the world to ransom by his accumulation of indigenous carboniferous energy wealth. Not even ‘military planners’ saw that coming despite Putin’s intention to invade ‘hiding in plain sight’.

That planners’ ‘plain sight’ tools may be of ancient provenance was a thought stimulated by September 2022s news that Cambridge University ‘innovators’ had fabricated paper ‘leaves’ coated with silicon powder that they claim can prevent water evaporation by being laid on water in reservoirs or aqueducts to stop them drying up (Parker Citation2022). Sounds expensive! Yet, the principle was something I learnt of already in 2012, 10 years earlier, in the Negev desert. Accompanied by Dan Kaufmann, EPS author and reviewer, via the Ramon desert sculpture park (), we were on our way to Eilat to present at the opening of the Eilat-Eilot ‘cleantech cluster’ project.

On the journey Dan explained that in the Negev, the indigenous civilization that inhabited it, also modern day south Jordan as well as Israel/Palestine, were the Nabateans. They were those who built the rock-carved Petra architecture. They conserved aqueducts by overshadowing them in tunnels or deep trenches through mountain rock. Furthermore, they conserved reservoir water by covering the surface with olive oil. It worked for the length of their civilization. Probably cheaper than silicon, although raw silicon is only expensive due to the fact it is complicatedly ‘processed’ sand. Stimulated by the old platitude that ‘there is nothing new under the sun’ I inquired of Google if or how the ancients dealt with disasters. This led me to speed-read a summary of a PhD (U. of Arkansas; McCoy Citation2014) on how the Roman Empire dealt with disasters. The dissertation focuses upon both the process of disaster aid delineating how Roman emperors were petitioned for assistance, the forms disaster relief took, and the political motives individual emperors had for dispensing disaster aid. Answer: Taxation, which those who suffered disasters also had to pay. Farmers, in particular, were not exempt, while elites were. Remoter regional interests were also exploited because they were not allowed to ‘lobby’ whereas Roman elites were expected to lobby because they kept the Emperor in power and benefited accordingly.

Fires, floods and other human-induced crises

I don’t know if the Nabateans were as exploitative as the Romans but from a ‘planning’ viewpoint they sound preferable to Rome’s ‘squeeze the poor’ policy confronted by an unanticipated crisis. Having said this, Rome also sounds like a prototype for the neoliberal approach to crises we have all recently been experiencing! I write on the day the UK’s new prime minister, Liz Truss and her chancellor Kwazi Kwarteng were forced to perform one of the more egregious political U-turns in UK history if they didn’t rescind their proposed tax cut for those earning £150,000 per year which was to be paid for by reducing the benefits of the poorest and unemployed recipients of the UK’s welfare-cum-workfare state. Their MP supporters in the UK parliament threatened to turn on them by voting down the policy along with other, related austerity lines that would pauperize millions of mortgage borrowers, inflation-hit consumers, striking public-sector health, teaching and refuse workers and privatized railway, bus, telecoms and postal employees. Even ‘lobbying’ remained as emphatic as in Roman times with corporate boards recommended by their remuneration committees, as approved by the UK government, to raise executive pay by 34% in 2021 while refusing to increase the living wage of shopfloor workers above 3% (e.g. Sainsbury’s Supermarkets as described by June 23rd Financial Times, Pooley Citation2022).

So finally, while little histories like ‘the Nabatean’ solution to drought are telling, so was an email message from a fellow academic in Jena, Germany on the drought issue. It told that Germans usually look towards the south in Germany for responses to drought. However, in 2022 with the forests between Saxony and the Czech Republic having been burning for weeks and expected to continue until early September - that region was widely impassable. More to the north, Brandenburg was also regularly suffering large-scale wildfires that summer of 2022. He concluded - there is hardly any rain in Winter – and 2022s summer was consecutively the fourth dry summer. It was further noted that the few German glaciers in the Alps may disappear during the summer – also affected by dust on the ice from the Sahara which interrupts solar reflection. Changing the narrative, by contrast, only a year earlier, in 2021 severe flooding hit the Eifel region, particularly the Ahrweiler district of the Mosel-Rhine valley in western Germany. At least 183 people were confirmed dead; Mosel vintners grappled with floodwaters while winemakers elsewhere sought to save their harvests as two months’ rain fell in 24 hours.

Meanwhile in France a year later, pine-forests burnt extensively over two months in the Landes area of south-west France. The Gironde was affected in July 2022 by two separate wildfires that destroyed more than 20,000 hectares of forest and leading to the evacuation of almost 40,000 people. Only sixteen houses were destroyed but fortunately there were no fatalities or serious casualties. Simultaneously, other parts of France experienced wildfires at the time, including in the southern areas of Lozère and Aveyron. Even the more distant Maine-et-Loire district in western France more than 1200 hectares were also burnt. Looking towards northern Italy the severe drought affecting the Po drainage area in a lengthy 2022 heatwave following a dry spring with little snowfall suggests worse environmental conditions. Italy is especially vulnerable to global heating, experiencing frequent extreme weather events. Thus in August 2021 temperatures reached 48.8, a European record. One such extreme event occurred in Alpine Italy where 10 people including seven hikers were killed in the Dolomite village of Punta Rocca in July 2022. This occurred beneath the range’s highest mountain of Marmolada when the overhanging end of a mountain glacier sheared off and crashed onto mountain paths and the settlement. Two months later, a severe rainstorm flooded out settlements in Marche region, drowning a further eleven residents with two missing and fifty injured in the flash flood. It occurred in Pianello del Ostra and neighbouring villages such as Senigallia in the vicinity of Ancona on the Adriatic coast. In 2022 Italian sea temperatures rose to five degrees higher than normal.

On some planning failures arising from the abundance of ‘Hubris’ and the poverty of Neglect

In some recent publications I have explored some of the undesirable, even ‘cruel’ outcomes of ‘hubristic’ planning projects, on the one hand, and simple irresponsible neglect, on the other, arguing for a less individualistic and narcissistic approach to the planning of change. Both types of outcome are caused by what psychologists refer to as ‘grandiose’ versus ‘vulnerable’ narcissism (Littrell, Fugelsgang, and Risko Citation2020). This distinguishes ‘grandiose’ from ‘vulnerable’ narcissism. Thus success enhances self-esteem but not critical reflexivity whereas failure leaves subjects more reflexive, insecure, defensive and introverted with lower self-esteem. The former captures the egotistic, over-confident and insouciant ‘starchitect’ and/or ‘design alchemist’ while the latter typifies the somewhat over-vilified ‘urban (or rural) planner’. The former promotes ‘exquisite designs’, frequently at someone else’s expense, e.g. the taxpayer, overcharged consumer, or unfortunate bystander, while the latter suffers criticism from the former and the ‘Build Absolutely Nothing Anywhere’ (BANA) constituency in equal measure. The former is impatient ‘to get things done’, including those with an ostensibly ‘green’ contribution to make to the built environment while the latter is responsible both for the interminable delays to the ‘planning process’ and for making ‘ostensibly crass determinations’, e.g. over fracking in a National Park, infringements upon hallowed views e.g. Goring Gap or Cuckmere Cottages, or allowing the demolition of heritage buildings in London’s Strand.

London’s Green ‘Garden Bridge’

The exemplar of this type of clash is London’s (unbuilt) ‘Garden Bridge’ over the Thames. It was dreamt up by Boris Johnson’s London Mayoral ‘chumocracy’ with once James Bond actress Joanna Lumley prominent and showman-designer Thomas Heatherwick’s Studio drawing up the plans. The development required the felling of mature trees on both sides of the river, including 28 plane trees at the approaches. More than replacing the loss of mature trees were to be some 270 immature trees, kept pruned to minimize wind loading on this exposed stretch of the river. The whole was underwritten by UK finance minister and ‘chumocracy’ member George Osborne, subsidized to the tune of £43 million by the taxpayer, some 90% of the outline design fee. The report into the failure of the London Garden Bridge pinpointed that:

Delays caused by failure to finalise land rights and planning permissions on both sides of the proposed bridge served to exacerbate the funding insecurity that plagued the project throughout. Further, the governance model established to deliver the project was not fit-for-purpose, which led to poor and non-transparent decision-making at critical stages to resolve these issues. (Cooke Citation2022a)

London’s Green Mound

At a smaller scale, but equally redolent of the hubristic, substantially over-ambitious but ultimately simply another vanity project aimed at ‘branding’ London as a ‘go-to’ destination was the (built but later demolished) London ‘Green Mound’. London’s Westminster Council, notably its deputy-leader Melvyn Caplan, hired Dutch design firm MVRDV for £6 million in 2021 to design a ‘Green Mound’ at the end of the city’s premier retail axis on Oxford Street, deserted after the Covid-19 ‘lockdowns’. This reincarnated the idea of an ‘artificial mountain’ from 2004 for the annual Serpentine Pavilion pop-up architectural exhibition in Hyde Park. This was never realized due to its excessive cost. While the ‘Green Mound’ was assembled in 2021, it was shut after only six months of desultory attendance. Subsequent reviews into the project’s failure blamed ‘hasty judgement’, ‘insufficient oversight’ and ‘circumvention’ of due diligence processes. These criticisms are so similar that they express something evolutionists call ‘pattern recognition’ about ‘agency’. Such ‘agency betrays evidently’ some common traits in certain metropolitan governance leadership that combines arrogance, ignorance, narcissism and vanity in the face of the urban ‘fragility’ Unlike Johnson, later disgraced, then ‘defenestrated’ from the post of UK Prime Minister, Caplan resigned for his incompetence with barely a whimper.

Arizona’s possible ‘15 minute City’

Our third vignette of ‘grandiose’ narcissism refers to another business ‘guru’, this time in the USA. Bill Gates who co-founded ‘Microsoft’ planned a ‘smart city’ at Belmont in Phoenix, Arizona after buying land for the project in 2017. However, much of the ‘Four Corners’ region is experiencing a 22-year and ongoing drought. This has caused a lower water table, meaning dry soil, dry vegetation and wind-driven wildfires. The future of the Colorado river drying up as a supplier of Phoenix reservoirs is contemplated as desertification beckons. However, Belmont remains unbuilt because of a fundamental error in Gates’ and his design team’s ignorance of sustainability development goals and constraints of the drought-ridden south-western region. The techno-utopian dream has thus been re-thought but with little visible outcome. Now, expert water energy management involving tidal and wave power are designed-in, as is the declining cost of solar power. Even if no aquatic sources prevail, for inland locations large-scale battery technology is feasible due to recent improvements involving advanced ‘powerpack’ battery storage. Vertical farming exists for salad and vegetable cultivation, sometimes in former urban workplaces emptied by the pandemic and digital homeworking. Hydroponics, aquaponics and vegan meat are also available with some products already in supermarkets. Reductions in commuting by wider adoption of the ‘15 minute city’ idea can be found in contemporary architectural designs (Harrop Citation2021). At such points, otherwise known as the ‘tipping point’ sustainability requires social leadership to ‘influence’ benign rather than malign outcomes.

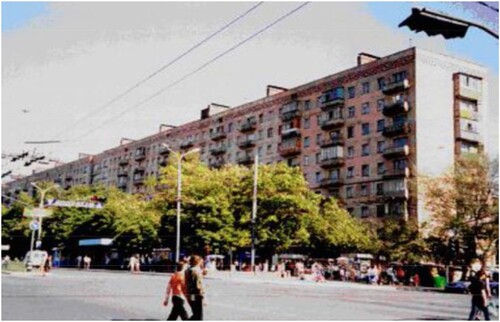

We may conclude that these mini-disasters having been avoided may offer exemplars of how not to do ‘dumb-city’ thinking but at least they avoided the potentially wasteful expenditure of substantially large sums of public or public-private development expenditure. Such lessons in future avoidance of humiliation for planners and ‘schadenfreude’ towards grandiose narcissism are to be welcomed rather than derided. They indicate just how tricky yet parsimonious can be anticipatory planning thinking compared to the waste of resources associated with catastrophes or human-induced disasters. It is worth noting that the costs of Putin’s war in Ukraine are astronomical. It is claimed that Ukraine alone uses up to $5 billion a month in armaments expenditure, while Russian bombing costs $4.5 billion per week in damaged urban fabric (Partington Citation2022). Third, that food supplies from one of the world’s breadbaskets is a globally vital resource but that producing it depends on carbonized agro-food production for fertilizer, herbicides, fungicides and insecticides, storage silos, transport and agro-machinery from coal, oil, gas and steel production that is a major contributor to global heating. One of the hidden tragedies of the destruction of Ukrainian city – Mariupol – is that it was largely built using zero carbon concrete by processing steelworks slag from blast furnaces. Concrete normally contributes 8% to global CO2 emissions but these Soviet era apartments were built from slag-based clay. Until blown up by Putin’s artillery, the apartment buildings attracted many western construction scientists to observe their innovative content and durability (). But for the future, the clean-up costs for the Donbas will be even greater. The World Bank (Citation2022) report outlines the problem as follows:

… Donbas is estimated to host about 900 large industrial plants, including 140 collieries, 40 metallurgical plants, 7 thermal power stations, and 177 chemically dangerous operations, including 113 operations that use radioactive materials. Environmentally, the most harmful industry is mining, which comprises 248 mines, many of which are run-down and nonfunctioning. In addition, the region is also traversed by 1,230 kilometres of oil, gas, and ammonia pipelines. By 2002, an estimated 10 billion tons of industrial waste had accumulated in Donbas, equivalent to a total of 320,000 tons per square kilometre. (World Bank Citation2022)

This represents a salutary case of the despoliation of a large part of this planet, managed unsustainably and irresponsibly. It is the kind of environmental planning challenge which could be a model for post-war reconstruction and environmental renewal if planned with forethought, multi-agency inclusiveness, sustainable implementation and the modern equivalent of Marshall Plan resources.

The following articles have been curated to read from the general to the more specific aspects of interest to sustainable development crisis preparation. As noted, this term is preferable to the more established ‘disaster planning’ epithet, which we nevertheless deployed in our previous EPS commemorative Special Issue of 2018. There it was referenced in relation to the aftermath of London’s Grenfell Tower high-rise housing disaster of 2017. The public inquiry, which completed its second phase of eight phases in July 2022, thus finished its second public evidence phase five years later. The next phases are technical evidence and not open to the public. The inquiry attorney noted the already vast gulf between the ‘terrible’ testimony of survivors and the jargon-heavy technical discourse of the construction industry defendants. Supply chains comprising multitudes of omissions and commissions ‘ … .discharging endless strings of emails … ’ were remote but had real ‘ … consequences’ for the victims. Indeed, incompetent fielding management of victim mobile phone messages to London’s fire officers was also highlighted as one the brigade’s major deficiencies contributing to the disaster. Training for such contingencies could have been modelled as early as 2010 had infrastructure system resilience been bought from logistics training experts like Training Regions International, part of a contingency planning consortium centred upon Lund University’s specialist Disaster Research institutes (Cooke, Citation2012). However, at the public inquiry the London fire brigade chief claimed she would not have done anything differently. The Commissioner subsequently resigned from her position (Cooke Citation2022b). So we now turn to summaries of the contributions to this second EPS commemorative issue, beginning with three articles on Circular Economies, which through Circular Development are augmented by conceptual innovations that have long been promoted by this journal such as ‘related variety’ that assists ‘path inter-dependence’ and even ‘revealed related variety’ (Neffke, Henning, and Boschma Citation2012) that facilitates ‘strange attractors’ to form unexpected, ‘crossover’ innovations.

Circular cities, water management, urban green space and urban shrinkage

The first contribution is by Jo Williams and entitled: ‘Circular cities: planning for circular development in European cities’. This paper provides insight into the circular development process. It discusses the role of planning in delivering circular development, using examples from four European cities. It identifies the tools for delivery and discusses the inherent limitations of using planning tools to deliver a circular transformation. Amsterdam has adopted a strategic, city-regional approach to resource looping, of construction and organic waste. Land has been designated for waste and bio-clusters to encourage industrial symbiosis in the port area. The development of bio-refineries has enabled organic materials to be recycled or energy to be recovered locally. In addition, nutrients are recovered from residual food for reuse (by restaurants or foodbanks) or composting. Space has also been designated in the city for resource banks to facilitate the circular construction processes’. Paris aims to create a local circular food system through the reuse of food waste and the regional production of food, both in the city and in surrounding districts. This is supported by the Parisculteurs initiative, which aims to cover the city’s roofs and walls with 100 hectares of vegetation by 2020. One-third of this space will be dedicated to urban farming. Food reuse is also legally enforced France-wide. London’s Olympic Park combines three circular actions. Bioremediation, local clean-up programmes and conservation schemes have helped ecologically to regenerate this previously industrial area. Diverse, natural species have been planted across the park. Waterways have been improved, while sustainable urban drainage systems have been fully integrated into the public realm. Finally, a celebrated eco-district of Stockholm (Hammarby) developed the infrastructure required to create a closed-loop, waste-to-energy system. It utilizes the existing city-wide infrastructural systems (district heating system, CHP plant and thermal power station) together with new technologies for converting sludge into fertilizer and biogas. Thus, sewage, waste-heat and refuse are used to produce energy. It is noteworthy that ‘food’ (i.e. pop and chocolate) firms create the worst waste, especially plastics, the global league table for which has been headed for the past four years by Coca-Cola, followed by Pepsi-Cola, Nestlé, Unilever, Mondelez and Mars (Cooke Citation2022b).

The next Circular Economy contribution comes from public Technology Consortium, ‘Tecnalia’, from the Basque Country, written by Marco Bianchi, Mauro Cordella and Pierre Menger and entitled: ‘Regional monitoring frameworks for the circular economy’. This paper contributes to a key research gap by, first, presenting a regional monitoring framework across three case studies; and, two, analysing the respective territorial patterns from a Circular Economy perspective. The three case studies include the central crossborder Scandinavian area, the regions of Switzerland and Liechtenstein, and the principality of Luxembourg. The results reveal that circular initiatives are generally designed on the basis of available local resources and, depending on these, regional strategies seek to optimize the technical and/or biological cycles of local economies. Furthermore, the increasing levels of waste generation observed in all case studies challenge traditional waste policy approaches, generally centred on end-of-life management, in favour of more ambitious initiatives aimed at optimizing use of resources and preventing waste.

The third Circular Economy contribution emphasizes its Aquatic dimension and is written by Jani Petteri Lukkarinen, Hanna Nieminen and David Lazarevic, and entitled: ‘Transitions in planning: transformative policy visions of the circular economy and blue bioeconomy meet planning practice’. They ask what happens when sustainability visions are exposed to planning practices, and vice versa, by developing an analytical framework to discuss processes of territorialization and mobilization. They draw lessons from two contextually differing case studies in Finland. First, the blue bioeconomy is framed as a source of solutions to provide sustainable food, energy and clean water. Technological innovations and the use of previously under-utilized resources, like algae, can contribute to meeting the increasing nutrient and protein demand and circular solutions have the potential in providing renewable energy. Second, water environments and landscapes perform an important role as a source of wellbeing and immaterial cultural services. Incumbent visions overlook the distributed cultural aspects of the environment, which also plays an increasingly important economic role because of global trends in nature tourism. Third, the protection of existing ecosystem potentials and the rejuvenation of declined capacities is a central aspect of the Finnish blue bioeconomy.

Moving on to the specific sustainability implications Urban Water Management, Franziska Ehnert provides a ‘Review of research into urban experimentation in the fields of sustainability transitions and environmental governance’. This paper explores urban experimentation planning in the context of transition studies. Transition studies conceive experiments as spatially and temporally circumscribed interventions. Clearly, these have to be scaled-up from niches (as protective spaces) to the regime and other contexts in order to generate fundamental change. This development and diffusion of experiments is captured by the transition mechanisms of deepening, broadening and scaling up. This approach was analysed by a study of changes to urban water planning in the Cooks River Catchment in Sydney, Australia, which emerged as an ongoing transition experiment. The development followed three phases of deepening, broadening and scaling up. More precisely, the deepening phase was characterized by lessons learned about alternative planning approaches towards water management within the local context. Frontrunners and partnerships were crucial to the success of this experiment. By comparing Urban Living Labs (ULL) in countries across Europe, municipalities most commonly adopt the partner role in ULLs, where partnership is based on shared leadership and participation on equal terms. Despite the highly diverse institutional settings of the countries they consider, similarities are evident as all roles are found to be represented in each country.

The next contribution is concerned with Rainwater Harvesting and written by Ender Peker in a study from Turkey. It is entitled: ‘Enabling widespread use of rainwater harvesting systems: challenges and needs in the twenty-first-century Istanbul’. He writes: Water supply has been a chronic challenge in Istanbul since its foundation. Authorities have sought alternative methods since the Roman and Byzantine periods. Cisterns, channels and wells surveyed in urban heritage sites in Istanbul provide evidence of rainwater harvesting as a working solution in the past but less in the modern era until recently. This contribution reports a participatory inquiry with water management actors. Current challenges are related to planning and development, legislation and governance, financing, society, infrastructure, installation and operation of systems. The potential solution is the establishment of a governance mechanism that enables collective action among relevant actors. In addition to the conflicts among different planning decisions, the unclear position of rainwater harvesting in the local urban development plan itself remains a problem. Crucial issues mentioned most frequently relate to the legislation and governance of planning, design and implementation of rainwater harvesting systems. The problem worsens in special areas such as conservation or coastal areas since different regulations and authorities become involved. The third most frequently mentioned group of issues concerns finance. The cost of initial infrastructure investment remains the main barrier to implementing rainwater harvesting systems. Interestingly, Istanbul is immune from conflicts affecting the subject that follows – urban green space – between 2% it has the lowest amount of any large global city (Cooke et al. Citation2022).

We now move on to a different specialty for development of sustainable solutions to ‘green’ cities, namely Urban Green Space. Nefta-Eleftheria Votsi writes from a study of Athens about ‘Green urban areas as ecological indicators: combining in situ data and satellite products’: The study investigated whether green urban areas (GUA) improve the urban environment. Field measurements were conducted to record noise and light pollution as well as other environmental characteristics in four GUA in Athens. The biodiversity status of the examined areas was derived from existing data. Only some GUA represent ecological refuges due to their varying configuration – human presence or not? Soundscape combined with artificial lighting and environmental and biodiversity status of a site clarifies the edge effect of ecosystems leading to an alternative, integrated, multidimensional management approach. Lack of a common methodological approach multiplies the complexities when attempting to plan GUA at coarse or finer scales. A limitation concerns the seasons chosen for field measurements as all seasons need to be considered independently in future research. Ecosystem quality in urban centres is of vital importance, also needing recognition to secure urban biodiversity but is still missing. In this paper, an innovative methodological approach was adopted, feasible to be implemented internationally, focusing on other characteristics (sound and light), revealing new dimensions of ecological information.

Our second Urban Green Space is presented by Megan Buckland and Dorina Pojani and the subject is: ‘Green space accessibility in Europe: a comparative study of five major cities’. In the current era of climate breakdown, access to green space is not optional – it is vital. This study investigates the current disparities in urban green space access in five medium-sized European cities: Birmingham, Brussels, Milan, Prague and Stockholm. Do disparities relate to income inequalities within cities and/or are they based on a city’s regional location within Europe. We find that Prague presents the highest green space accessibility, followed by Stockholm, Brussels, Birmingham and finally Milan. Higher-income residents have more access to green space in Brussels, Milan, Prague and Stockholm. In Birmingham, however, lower-income neighbourhoods presented higher green accessibility. Urban green spaces were distributed differently across the various European regions, each of which has a unique history and planning culture. Urban planners are challenged to redress these disparities – while considering the unique environmental, economic, social and cultural dimensions of each place.

Our final section is devoted to ‘green’ solutions to change in urban construction materials to advance the se of sustainable materials and to revitalize what are perceived as ‘shrinking cities’. The first of three contributions explores regulatory change that promotes ‘wooden buildings in Finland’. It is contributed by Florencia Franzini, Sami Berghäll, Anne Toppinen and Ritva Toivonen in an article entitled; ‘Planning for wooden multistorey construction – insights from Finland’s municipal civil servants’. Despite Finland’s abundance of wood, which was traditionally utilized in domestic dwelling construction, building practices changed when historic fire regulations banned wooden construction above two storeys. Accordingly, modern load-bearing construction replacing wood with concrete rapidly spread. Recently, though, stimulated by the country’s Bioeconomy Strategy of 2014, which coincided with a major downturn in the forest products sector as demand for pulp and paper declined, led to change that trajectory once again. Concrete had by then become associated with a massive CO2 surplus and the Prime Minister’s 2019 announcement of a Carbon Neutral Finland by 2035 triggered its demise. Simultaneously other government-supporting initiatives to promote wooden construction in place of concrete were implemented. Our question was: do attitudes towards implementing these alternatives stem from the opportunity to reduce carbon emissions or because these alternatives are perceived to improve local economies? Importantly, municipal planners holistically prioritize the project’s ecological and economic development outcomes. Other administrators chiefly prioritize economic development outcomes.

The two ‘Shrinking Cities’ contributions that round off this Jubilee Special issue are, first, contributed by Annamari Kiviaho and Saija Toivonen, also from Finland in: ‘Forces impacting the real estate market environment in shrinking cities: possible drivers of future development’. Their study deepens understanding of the forces affecting the real estate market environments of Shrinking Cities by examining the public discourse and the perceptions of local market participants, both of which steer future market development. To identify and analyse these forces, an environmental scanning method was employed, using as data sources 872 Finnish newspaper articles and 45 interviews with market actors in eight shrinking cities in Finland. The results categorize the identified forces under three themes that describe the drivers of future market development. The findings indicate that, although the Real Estate markets of Shrinking Cities face challenges, forces such as telecommuting, multi-local living and emerging industries may offer new opportunities and slow urban shrinkage. The findings may be utilized to steer the development of Shrinking Cities in a more resilient direction.

And our final Finnish contribution has a rather poignant title from Ria-Maria Adams, Alla Bolotova and Ville Alasalmi is called: ‘Liveability under shrinkage: initiatives in the ‘capital of pessimism’ in Finland’. This article focuses on local initiatives and the agency of residents in the shrinking town of Puolanka in Northern Finland. Structural opportunities and constraints are shaping individual and collective agency about the place as they constitute the way how people create and develop initiatives. We discuss how local initiatives impact the place perception of local people who want to stay in their rural hometown. A group of local activists sarcastically market Puolanka as the ‘most pessimistic town’ in the world, turning shrinkage, decay and pessimism into a brand for this place. Beyond the pessimism brand several other initiatives, which are either created by engaged local residents or are municipality-led, are revitalizing and enhancing the liveability of Puolanka. By applying ethnographic research methods, we aim to show how initiatives improve well-being and contribute to the place perception of residents. Such initiatives create jobs, albeit usually in small numbers, improve the physical space, stabilize the sense of community and can bring hope to a place characterized by increasing abandonment, decay and the loss of local services. The city has a remarkable and highly thought of health care system. One important initiative by Puolanka’s municipal administration was to invest in the local health care services. Our research results show that regardless of local residents’ intentions to stay or leave Puolanka, they were highly satisfied with the quality of local health services, which is quite in contrast to the other towns in the region of Kainuu. It is one of the key factors of well-being in a declining place with an ageing population. This initiative, regardless of age, status and gender, was perceived as ‘beneficial’ for all residents. Both the municipal leaders and the residents of Puolanka have regarded their privatized health care system (unique in Finland) as a better option for maintaining a high-quality service level in a rural town. In addition to the remarkable health care provision, the municipal administration has developed and executed a number of initiatives such as a biogas plant. This was built to generate energy from waste that potentially provides the entire town with thermal energy for heating their houses and water.

References

- Cooke, P. 2012. Complex Adaptive Innovation Systems. London: Routledge.

- Cooke, P. 2018. “Retrospect and Prospect: From a New Dark Age to a New Dawn of Planning Enlightenment.” European Planning Studies 26 (9): 1701–1713. doi:10.1080/09654313.2018.1499429

- Cooke, P. 2022a. “Callous Optimism: On Some Wishful Thinking ‘Blowbacks’ Undermining SDG Spatial Policy.” Sustainability 14: 4455. doi:10.3390/su14084455.

- Cooke, P. 2022b. “Beyond the Smart or Resilient City: In Search of Sustainability in the Sojan Thirdspace.” Sustainability 14. doi:10.3390/su14084455.

- Cooke, P., S. Nunes, L. Lazzeretti, and S. Oliva. 2022. “Open Innovation, Soft Branding and Green Influencers: Critiquing ‘Fast Fashion’ and ‘Overtourism’.” Journal of Open Innovation, Technology, Markets & Complexity. https://doi.org/10.3390/xxxxx.

- Harrop, P. 2021. “Rethinking Smart Cities: Setbacks and How to Move Forward.” IDTechEx. https://www.idtechex.com/en/research-article.

- Kyne, D. 2020. “Empirical Evaluation of Disaster Preparedness for Hurricanes in the Rio Grande Valley.” Progress in Disaster Science 5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pdisas.2019.100061.

- Littrell, S., J. Fugelsgang, and E. Risko. 2020. “Overconfidently Underthinking: Narcissism Negatively Predicts Cognitive Reflection.” Thinking and Reasoning 36 (3): 352–380. doi:10.1080/13546783.2019.1633404

- McCoy, M. 2014. “The Responses of the Roman Imperial Government to Natural Disasters 29 BCE-180 CE.” Ph.D. (History) diss., Fayetteville, University of Arkansas.

- Neffke, F., M. Henning, and R. Boschma. 2012. “The Impact of Aging and Technological Relatedness on Agglomeration Externalities: A Survival Analysis.” Journal of Economic Geography 12 (2): 485–517. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbr001

- Parker, C. 2022. “Artificial Leaf Turns Sunlight, Water and CO2 into Clean Fuel.” The Times, August 22, 11.

- Partington, R. 2022. “Russia’s War in Ukraine ‘Causing £3.6bn of Building Damage a Week’. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/may/03/.

- Pooley, C. 2022. “What Business Can Learn from the UK’s Public Sector Strikes.” Financial Times, June 23.

- Raikes, J. 2019. “Pre-Disaster Planning and Preparedness for Floods and Droughts.” International Journal for Disaster Risk and Reduction 38. doi:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2019.101207.

- van Berlaer, G., T. Staes, D. Danschutter, R. Ackermans, S. Zannini, R. Buyl, G. Gijs, M. Debacker, I. Hubloue, and G. Rossi. 2017. “Disaster Preparedness and Response Improvement: Comparison of the 2010 Haiti Earthquake-Related Diagnoses with Baseline Medical Data.” European Journal of Emergency Medicine 24 (5): 382–388. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000387.

- World Bank. 2022. Recovery and Peacebuilding Assessment: Ukraine. https://reliefweb.int/report/ukraine.