ABSTRACT

Leisure-led regional development refers to leisure as a mechanism to achieve broad societal goals within a region: economic revenue, employment and service levels but also cultural or conservationist ambitions. Engaging in such leisure-led regional development proves a complex matter. Based on ethnographies of leisure in the Dutch province of Fryslân conducted over a five-year period between 2013 and 2018, this paper argues that combining theoretical understanding of complexity theories with analyses based on both evolutionary and discursive approaches results in enhanced understanding of the interactions shaping uncertainty in leisure development. Results of field observations, interviews, participation and document analysis show that planning for leisure-led regional development should consider autonomous and evolutionary processes, whilst focusing on purposefully influencing the interactions and perspectives of actors in leisure. More precisely, this means shaping the narratives and practices in these institutions which make specific interactions more likely to develop. This can be undertaken by including in planning efforts the individual perspectives and emotions among actors in the regional leisure sector. To cope with uncertainty at the heart of leisure-led regional development, an adaptive strategy should be adopted, both in the planning efforts taken and in how such efforts are monitored and evaluated.

Introduction

Planning for leisure-led regional development concerns purposeful interventions in space and place to support leisure development. Additionally, this entails the understanding that sustainable and long-term development of leisure contributes economically to employment, serves as incentive to preserve cultural and physical heritage, and increases well-being within a community. Planning for such leisure-led regional development can, however, be challenging mainly due to leisure complexities with which planning is often faced. These complexities include: fragmentation of the leisure sector through many small business and individual actors; the precarious balance between developing leisure and protecting the amenities on which it is based such as nature, peace and quiet; and the crossovers between (socio-)economic goals such as developing leisure as a way to maintain higher service levels for the local community (Meekes, Buda, and De Roo Citation2017b). These complexities can have profound spatial ramifications, creating regional differences in development. This paper employs complexity theories to discuss the development of leisure, tourism and recreation, referred to simply as leisure in this paper, exemplifying this with the case of the Dutch province of Fryslân (Jeuring Citation2015; Meekes, Buda, and de Roo Citation2020). Development in this perspective progresses non-linearly, due to processes of self-organization, co-evolution and emergence (Chapman Citation2009; Martin and Sunley Citation2007; O’Sullivan Citation2009). This is applied in this paper to leisure and tourism, highlighting the way in which a complexity perspective can help in planning for leisure-led regional development. The main argument of this paper is that for leisure, the main source of complexity lies in the interactions between the people or actors involved. Analyzing the non-linear development of leisure, the focus should therefore be on these interactions between people as a driving force of (spatial) variation. This requires an approach that allows for the inclusion of the views, experiences, habits and emotions of actors in leisure.

To allow for a focus on the interactions between actors in leisure as drivers of complex non-linear development, this paper draws on regional ethnographies. Ethnography is understood as a research strategy rather than simply as methodology per se, because it entails the project’s research design, methods, analytical tools, theoretical perspectives and representational forms (Denzin and Lincoln Citation2018). Ethnography is time intensive, iterative and open ended. The ethnography in this study comprised of five years (2013–2018) of working and doing research in leisure in Fryslân. The regional ethnography used here includes observing as participant observation, listening and reflecting along with collecting mass media and policy documents, employing a historiography-based analysis and most importantly learning from participants via interviews. This allows for the inclusion in the research process of diverse views, perspectives and emotions of actors in the leisure sector, more so than would be the case with case study research. The questions that ethnographers ask always change during the research process, because a significant part of any study entails being sensitive to the socio-economic relationships and ethical responsibilities associated with framing, generating, co-creating and representing knowledges.

The conceptual question central to this paper is: what does planning for leisure-led regional development entail from the perspective of complexity theories? Such a perspective is based on the idea that the whole of leisure-led regional development is often not simply the sum of its parts. This paper explores the value of a complexity perspective for planning by discussing the various forms of analysis that can inform the potential for planning interventions, concluding that complexity mainly derives from the interactions between individuals. First, complexity theories provide planning with a conceptual understanding of non-linear processes through which leisure-led regional development takes place. Secondly, because complexity focuses on development over time, an evolutionary analysis reveals how such processes have taken place and which interactions have a profound influence on leisure-led regional development (cf. Hodgson Citation2006). Thirdly, focusing on these interactions, the values and meanings of people involved in leisure simultaneously structure and are structured by their interactions (Meekes, Buda, and de Roo Citation2020). This paper argues that, when considering these three forms of analysis, planning for leisure-led regional development ought to move past simplification of quantitative evaluation criteria and targets to focus on institutional structures and existing discourses as driving and constraining forces of interactions between actors.

Complexity approaches are not new to planning. The ways in which planners can deal with these complexities have been debated in both academia and practice during the last decade. Complexity theories offer valuable perspectives for both leisure and tourism studies (Farsari, Butler, and Szivas Citation2011; Speakman Citation2016) and spatial planning theory (Chettiparamb Citation2013; De Roo Citation2017). Both leisure and spatial planning have often relied on the reduction of uncertainty, whether through a technical rational approach or a focus on consensus building. The value of complexity theories, however, lies in taking into account unpredictable developments without reducing uncertainty, by calling for more adaptive strategies (Boonstra Citation2015; Hartman Citation2015; Rauws, Cook, and Van Dijk Citation2014). Combining ethnographic research on leisure and spatial planning, this paper debates how theories on complexity can be used in planning for leisure, specifically for coping with uncertainty arising through the different perspectives of actors. Using an ethnographical approach to analyzing leisure allows for a focus on individual actors and their interactions as the main source of non-linear complex development.

Theories of leisure and tourism planning

Leisure, in this paper, is employed as a shorthand for leisure, tourism and recreation and is considered to be a volatile sector; it is fragmented, manifests a precarious balance between developing and protecting (landscape) qualities and has a contested potential to contribute to broader regional development (Milne and Ateljevic Citation2001). Leisure is often considered, mainly by local governments, a means to achieve regional development, especially in rural and peripheral locations (Dana, Gurau, and Lasch Citation2014). This translates into spatial government policies directed towards stimulating leisure-led regional development. However, planning for leisure-led regional development, especially with goals that transcend the economic into goals of well-being or identity, proves to be a complex and unpredictable practice due to the many interacting actors and sometimes conflicting policy goals (Hartman Citation2015; Stebbins Citation1982). Planning here is defined as any actions taken by either government or other actors with the goal of influencing future developments towards a desired direction.

During the 1950s, planning was based on a rational perspective in which the idea was that planning could command a future reality, with plans expected to turn out the way they were intended. Over time, aspects of uncertainty were more and more taken into consideration in planning theory and practice. Scenarios were a first step in this development, conceived as a way to integrate a certain sense of flexibility between possible future outcomes (Harrison Citation2013). Still, such scenario planning was largely based on the idea that the effects of planning could be predicted within a certain (slim) margin of error, and that margin of error was known. With the communicative turn in planning, a new perspective on the role of planners was introduced (Healey Citation1992). The development of an area was deemed to be strongly dependent on the perspectives of actors in that area, and means were developed to include the necessity for a consensus among actors to achieve the desired goals.

Theories on leisure planning, by which we mean planning specifically for the development of leisure and tourism, have shown similar historical approaches largely due to having emerged as a specialization of spatial planning (Costa Citation2001). The main difference that can be observed is the stronger involvement of the private sector within leisure planning than in the more government-oriented focus of broader spatial planning. Dealing with uncertainty, perhaps it could be said that through the work on the Tourism Area Life Cycle (TALC, Butler Citation1980) the concept of non-linearity was brought to the field of leisure at a stage in which this was not yet common place in spatial planning. Nonetheless, despite the TALC model taking a step away from traditional rational growth models, it is still reflective of a view of planning and development based on a seemingly predictable future. In this sense, the TALC model is more reminiscent of scenario planning. The communicative turn, which followed scenario planning in the development of spatial planning, is mirrored in leisure planning through a shifting focus towards community-based planning (e.g. Jamal and Getz Citation1995).

One thing these approaches – from rational to communicative planning – have in common, is that they ingrain a sense of reduction of uncertainty in planning efforts (Speakman Citation2016). The development of complexity theories, and their application to planning theory and practice, have posed a new question of how to deal with a uncertainty that cannot be reduced through means of data analysis, consensus building or participative processes (Olssen Citation2008). This implies creating a planning approach that is not based on reduction towards certainty, but allows for non-linear and unpredictable developments through adaptive strategies. Similar to the development in spatial planning, some academics in leisure planning have recently focused more on non-linear development. A growing interest in evolutionary approaches, for instance in evolutionary economic geography (EEG) is visible in leisure studies (Brouder et al. Citation2017; Ma and Hassink Citation2013; Saarinen, Rogerson, and Hall Citation2017). Additionally, some academics have focused on unpredictability in leisure through the lens of complexity theories (Farsari, Butler, and Szivas Citation2011; McDonald Citation2009; Milne and Ateljevic Citation2001; Zahra and Ryan Citation2007). This paper explores such a complexity approach to leisure planning and argues that this approach can take into account the broader goals of leisure-led regional development that transcend the economic. However, this requires a shift in focus, particularly in terms of the analysis and evaluation that support planning efforts and decisions.

Complexity of leisure

A central theme of complexity theories is the idea that the whole is not necessarily equal to the sum of its parts (Heylighen, Cilliers, and Gershenson Citation2007). This arises from the multitude of interactions between these parts, which cannot be reduced merely to the characteristics of the parts themselves, but develop through processes of co-evolution, emergence, self-organization and path-dependence. Because developments cannot be determined based solely on an analysis of their constructing parts, a fundamental uncertainty arises (Byrne Citation2003; Cilliers Citation2005). This creates non-linear and often unpredictable behaviour in which small changes can have major effects, or vice versa large developments can have very little effect on a structural level. This also implies that development over time can show path dependency, but cannot be extrapolated based purely on an analysis of past and existing patterns (Gerrits Citation2008).

Coping with uncertainty is one of the central issues for practitioners and academics in spatial planning with even the best thought-out plans sometimes failing due to unforeseen circumstances (e.g. Balducci et al. Citation2011; Hillier Citation2008). Academics have recently attempted to approach uncertainty differently: not by reducing such uncertainty, but accepting the unknown as part of a theoretical framework that embraces complexity (Boelens and de Roo Citation2016; Gerrits Citation2008; Heylighen, Cilliers, and Gershenson Citation2007). Complexity theories offer in-depth understandings of the mechanisms through which space develops. Translating these complexity theories to the practice of planning has proven a challenge. Although these theories offer insights into the abstract analysis of development over time, their direct impacts on the practice of planning is less clear (Dobrucká Citation2016). This paper builds on the idea that planning based on complexity theories provides a way to add a dimension to existing planning approaches in a manner that acknowledges the complexity and unpredictability of the real world. This means allowing for both the more objectivist background of design and control planning and the constructivist approaches of a communicative planning approach, while simultaneously including a more temporal perspective. The use of these planning approaches then becomes more situationally and temporally dependent (De Roo Citation2012).

Leisure, and particularly leisure-led regional development, provides an illustration of the value of complexity theories in planning. Leisure is fragmented, both as a socio-spatial phenomenon and as a policy issue. It often exists on the fringes of urban and rural areas, and sometimes falls outside of the more traditional planning categories of nature and agriculture used in rural land-use planning and policy (e.g. in the Netherlands, Hartman and De Roo Citation2013). The leisure sector consists of a multitude of actors, which is reflected in a high proportion of small local firms (Ecorys Citation2009). The leisure sector in a region then is made up of the aggregated actions of these firms, which together make up one product, a destination. Strengthening this product requires a form of interaction, and often cooperation, between various actors. However, such actors are simultaneously competing among each other. The complexity, therefore, lies on the one hand in the leisure sector being shaped by the sometimes contradicting actions of actors, but on the other hand in the unpredictability of how these actions will affect the whole of the leisure sector.

When, from a planning perspective, leisure is understood as a way of stimulating regional development, this complexity is further enhanced due to the inclusion of more interactions; not just those within the leisure sector but also relating to other policy goals. Development of leisure can be detrimental to the qualities and amenities that actually form the basis of the leisure sector. Especially in rural and peripheral areas, amenities like nature and a sense of peace and quiet can be driving forces of a leisure economy (Heslinga, Groote, and Vanclay Citation2018). Further developing the leisure sector can diminish these qualities; for instance, adding more holiday homes in or around a nature area can harm the attractiveness of that nature area. This means that measures that are taken with the goal of further developing leisure can end up having the opposite effect. Finally, leisure-led regional development is often aimed not only at economic benefits, but thought to affect a region positively in other aspects as well, for instance through offering leisure-related amenities for people living and working in the region. The fact that leisure is often aimed at pluriform goals further enhances the complexity of planning for leisure-led regional development. It is such characteristics of the leisure sector that make it distinctly suited for an analysis based on complexity theories.

Complexity theories provide planning theory and practice with a challenge. The act of planning presumes some sort of knowledge of the future. This future, however, contains elements which are considered fundamentally uncertain in complexity theory. This could lead to a view of planning as ‘a contradiction in terms’ (Block et al. Citation2012, 984), because if the future is fundamentally uncertain planning efforts cannot be expected to result in predefined outcomes. However, uncertainty is of course not new to planning, nor does it stand in the way of directing ways to influence future development. Complexity theory does not suggest that all predictions are futile. Despite a fundamental uncertainty that makes accurate prediction impossible in the long run, processes of self-organization, emergence, co-evolution and path dependency do create patterns that are to some extent predictable and can be influenced.

To understand the value of complexity theory to planning, complexity must be considered not as a new approach to planning. In contrast, planning that incorporates complexity theories should combine various aspects of planning theory and practice in a way that focuses on patterns that provide some sense of predictability while simultaneously aiming for the adaptive capacity to cope with unpredictable outcomes (Block et al. Citation2012). Perhaps the most important contribution of a complexity perspective to planning theory and practice is the focus on interactions as driving forces of uncertainty (Cilliers Citation2005). This provides planning with a perspective for analysis that does not aim at reducing uncertainty, but takes into account the mechanisms through which this uncertainty arises. This focus on interactions means that structures that influence these interactions become the main sphere of influence for planning. Institutions play an important role in governing interactions, making some more and others less likely to develop. An evolutionary analysis can show how such interactions are shaped over time and are influenced by these institutions (Martin and Sunley Citation2007). Additionally, interactions are influenced by the individual values and meanings actors assign. Actors in leisure are more likely to form interactions with those who share their interpretation of leisure-led regional development, and the meanings and values they assign to leisure determine which course of action they are more likely to take (Meekes, Buda, and de Roo Citation2020). This requires an analysis that encompasses the role of individual actors in leisure. In the end, complexity and non-linearity in leisure derive largely from the actions of the people involved.

Regional ethnographies of planning and leisure in Fryslân

This paper employs regional ethnographies of planning and leisure in Fryslân to focus on the role of individual actors as driving forces of complex and non-linear development (Bryman Citation2008). Deriving from anthropology, the most common ethnography is the one intensively focused on one site of observation and participation. A single-site whereby the ethnographer probes local situations and people. Over the past two decades, ethnography moves from its conventional single-site location, contextualized by these larger socio-political orders, to multiple sites of observation and participation (Marcus Citation2012). Moving out from the single sites and local situations of conventional ethnographic research to multi-sited global locations, ethnographers examine the circulation of cultural meanings, objects, and identities in diffuse time-space. In-between single-sited and multi-sited ethnographies, we situate regional leisure ethnography whereby a dynamic mechanism such as planning for leisure is followed across the Dutch province of Fryslân.

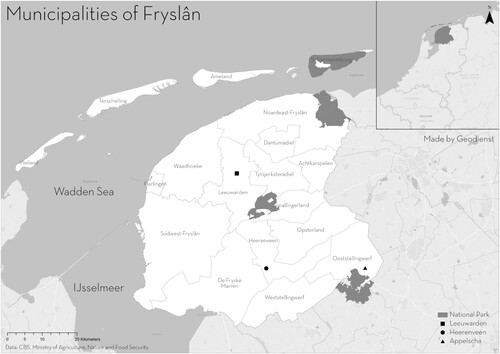

Ethnographic insights include tools such as participant observation at leisure sites, note taking, collecting mass media and policy documents and conducting semi-structured interviews to observe, gather, record and interpret the material. This ethnographic study focuses on the role of planning in leisure-led regional development. The first author has worked as a researcher on leisure in the province of Fryslân for a period of five years between 2013 and 2018, immersed in the leisure sector as an observer-as-participant (Bryman Citation2008). In this period, the author, as ethnographer, has collected material through various methods: a historiography based on the study of newspaper articles, collecting and curating local and regional policy documents, conducting semi-structured interviews with 37 actors in the leisure sector, site visits to multiple leisure facilities and destinations in Fryslân and a set of statistical information on the development of leisure in the province. The interviews, observations and other research activities took place in a multitude of Frisian municipalities, although some interviews were focused more specifically on the municipalities of Leeuwarden, Ooststellingwerf, Noardeast-Fryslân, Heerenveen and Harlingen (). Triangulating these methods provides a comprehensive, in-depth ethnographic overview of how planning for leisure-led regional development in Fryslân is affected by non-linearity and unpredictability. This provides insights into how planning can cope with complexity in the case of leisure in Fryslân, but also how a complexity perspective can be beneficial in spatial planning as a whole. The experience gained throughout these years of research means that positionality also developed throughout the research period. Where the ethnographer was positioned as more of an outsider looking in during the first period of the research, this developed into a position more embedded in the leisure sector during the course of the research. This development is a valuable addition to the research, as the research notes from both situations are used for the interpretation in this paper.

The use of an ethnographic approach to studying leisure-led regional development in Fryslân allows for insights that are not easily obtained through more conventional approaches in leisure and planning research. The main value of the ethnographic approach employed in this study is the possibility to explore and describe the motives and attitudes of actors in leisure in a comprehensive manner. Through immersion within planning and leisure in Fryslân, the project’s first author as ethnographer is able to gain enhanced understanding and interpretations of the choices and mechanisms that determine the way in which actors behave. This allows for a stronger focus on emotions, habits and experiences of leisure actors than would be the case in a more traditional qualitative research approach. Additionally, this means focusing on planning not only as a government task, but as a set of practices shaped by actors involved in leisure (Christensen and Albrecht Citation2020). This approach is central to the main argument of this paper, as the focus on the personal views of actors allows for analyzing complexity deriving from the interactions of people involved in leisure.

Analyzing complex leisure

Fryslân is a province in the north of the Netherlands. It comprises 24 municipalities and has a population of nearly 650.000 people on a total land area of just over 3300 km2 (Provincie Fryslân Citation2015). In this province, population decline in rural areas combined with an overall restructuring of the labour market has led to leisure being seen as a potential sector for growth of the economy and especially the labour market (Hartman, Parra, and de Roo Citation2015). Leisure is not new to the area, as various parts of the province have developed a significant leisure economy through the years. Most strongly this is the case for two regions: the Wadden islands, north of the mainland, which function largely as a separate destination; and the Frisian lake district, which has developed into a major destination for sailing and other water-related leisure activities (Heslinga, Groote, and Vanclay Citation2018). However, leisure has developed in some areas of the province, but, in others, this is less the case. As a whole, the leisure sector comprises a sizeable part of the economy, although it is characterized by a strong fragmentation, with a high number of small firms each contributing to the overall destination of Fryslân. Therefore, planning efforts to further develop the leisure sector, especially with a broader goal of regional development, are not easily contrived.

The complexity of leisure-led regional development is visible within Fryslân. Leisure-led regional development depends on a multitude of actors, balances development with protecting existing qualities and focuses not only on economic but also other policy goals such as liveability and nature protection (Meekes, Buda, and De Roo Citation2017b). When viewed over time, the combination of these aspects of complexity creates non-linear and unpredictable development. An example of this can be seen in the village of Appelscha, in the southeast of Fryslân, which the ethnographer visited on multiple occasions (cf. Meekes, Parra, et al., Citation2017). For a long time, this village was a strong tourism and leisure destination in Fryslân. Many people from the north of the Netherlands visited the town, in which one of the central attractions was the amusement park, Duinen Zathe. During the ethnographer’s immersion in this area, it was ascertained that this actor, the amusement park, was connected to many other actors in the village, for instance restaurants, camp sites and at one point also a miniature park. As such, all these actors together formed a destination that was stronger than just one of these amenities on its own. However, due to the need to expand, the amusement park was moved from the heart of the village to the outskirts. In this process, the connections with other actors and amenities were affected, and the ‘whole’ that was the destination of Appelscha no longer functioned as such. Although the amusement park was only moved by a few hundred metres, the effect was that the various leisure facilities no longer acted as one destination. From the discussions and interviews, the ethnographer was informed by numerous actors in leisure in Appelscha that they felt the move left a hole in the centre of the village. The effect was a disruption of the existing interactions. The patterns created by these interactions (for instance of combined visits to multiple attractions) therefore no longer existed. Instead of a linear progression, such a disruption represents a non-linear development: the system, or ‘whole’, may be more or less sensitive to small events (Suteanu Citation2005), meaning that cause-effect relationships can be disproportionate. What may seem a small event can have a great impact and, vice versa (Rauws, Cook, and Van Dijk Citation2014). Such events highlight the need to consider the complexity that is created through connections between actors in leisure.

The complexity of leisure-led regional development affects planning for leisure in other ways as well. This is for instance made clear in the case of the Frisian bid for Leeuwarden as European Capital of Culture (ECOC) in 2018, which was closely observed and analyzed by the ethnographer. The province of Fryslân bid for, and eventually was awarded, the title of European Capital of Culture for the year 2018. This bid was aimed at leisure-led regional development, not just by attracting tourists to the region during the year as ECOC, but also as a ‘large scale cultural intervention’, meant to tackle the social, economic and ecological challenges facing the city of Leeuwarden and the region of Fryslân (Stichting Kulturele Haadstêd Citation2013). In this sense, the bid for the ECOC acknowledged leisure as strongly connected to the socio-economic development of the region, something that was also expressed to the ethnographer by multiple interviewees involved in the organization of the event. The complexity of leisure-led regional development was acknowledged in policy texts. However, the evaluation criteria and targets listed largely abandoned this more holistic approach, as they were reduced to simple statistical measures that did not grasp the complexity of the goals of the project. This increased the chance of efforts being aimed solely at these limited evaluation criteria, for instance, the number of tourists or the average spending. This narrower scope thereby disregarded the actual goals of the year as European Capital of Culture, which had a broader societal focus through concepts such as community building and inclusion. It is unsurprising that policy is often translated into quantifiable targets and evaluation criteria, to facilitate political inference. However, from a complexity perspective, a broader analysis that incorporates a more evolutionary approach and allows for a focus on the interactions shaping non-linear processes is warranted (Martin and Sunley Citation2015).

The two examples in leisure-led regional development given here show that a complexity approach to leisure-led regional development necessitates an analysis that accounts for time: it is in the evolution over time that non-linear mechanisms of complexity are made apparent. If planning measures are to include this non-linearity and complexity, planners and policymakers need to understand the process in which adaptations can emerge through the interactions between actors. An evolutionary perspective centred on the actions of individual actors and the way these actions influence others through interactions can explain how such adaptations can create larger-scale spatial patterns (Meekes, Buda & De Roo, Citation2017a). The analysis of leisure-led regional development stresses the evolution of interactions between actors in leisure and the way in which changing institutional structures affect such interactions. In this way, such an analysis can unveil the autonomous processes in a region.

An analysis of the development of leisure in Fryslân over time reveals differences in the dynamics of development of leisure between regions within the province. Some regions show positive development, where others seem more stagnant. Part of this difference can be explained through the influence of what Russell and Faulkner (Citation1999) call ‘movers and shakers’: innovative actors that through their connections with others can change the direction of development in an area. Additionally, the differences could be explained through the presence or absence of a shared sense of urgency among actors in the leisure sector. The ethnography shows that in some areas developments such as population decline and diminishing importance of agriculture had created a sense of urgency for the development of leisure. For example, an interviewee stated:

I think that for an area like this tourism is mega important, because we’re dealing with decline here and there are few answers to decline and I think leisure is one of the few sectors that should really still be able to change things here. – Kollumerpomp, November 27th 2015

The ethnography of leisure-led regional development in Fryslân highlights how a shared sense of urgency affected the way in which interactions were formed and the way in which this led to structural changes in leisure (Meekes, Buda & De Roo, Citation2017a). In areas where actors shared the view that cooperation and communal effort was needed to develop the leisure sector, a more dynamic development of leisure was observed. In contrast, in areas where a vision expressed from a government level was not shared by individual actors, this could lead to a more cynical view on cooperation from actors. In the Frisian municipality of Heerenveen, another ethnographic site for this project, the efforts of the municipality to create a single frame to capture the leisure efforts in the area was met with scepticism by multiple actors who had differing views and interests. The interests of a sailing school, a modern art museum or a hotel in the middle of a wooded area did not coincide with each other, or with the municipal frame which built on Heerenveen’s national fame as a centre for sports excellence stemming from the local football club and speed skating arena. In discussions with the ethnographer, the various leisure actors in the area consequently expressed little interest and in some cases even fatigue with the local initiatives aimed at fostering cooperation within this frame. For example, one interviewee stated:

I mean, I’ve been here for eight years now, I know how it works. It sounds a bit haughty, a little arrogant maybe, but I’m not going to lose my time anymore with little projects or meetings where with all the best intentions we’re told what we really should be doing, but which never lead to anything. – Heerenveen, 8th of December 2015

The perspectives and views of individual people involved in leisure condition the way in which leisure-led regional development evolves by structuring the cooperation and interactions between actors. Analyzing the views, meanings, emotions and discourses with relation to leisure that pervade among actors in leisure can help further understand the development of leisure. This stems from the notion that future actions are strongly influenced by the individual outlooks of actors. Additionally, the existence of less prominent, more subordinate discourses, could reveal the possibilities for unforeseen future bifurcations. The role of planning can then be interpreted in two separate ways: from a more proactive perspective of planning the dominance of certain existing discourses could be reinforced or challenged, depending on the desired goals. In this case, planning is aimed at specific development paths that are deemed to be the most desired. A more reactive view on planning would consist of an analysis of existing discourses, both dominant and subordinate, allowing for the facilitation of multiple paths of development. In this view, planning is not directive, in the sense of aiming for a specific future development, but responsive to perceived autonomous development which can be facilitated if so desired.

Planning for leisure-led regional development

Ethnographies in Fryslân primarily show that leisure is a complex matter, especially when seen in the perspective of leisure-led regional development, where broader societal goals are targeted through the development of leisure. Planning for leisure is affected by such complexity: when planning measures do not take into account the fundamental uncertainties at the heart of leisure, planning can lead to results which are not expected or desired. An example of this is seen in the case of Appelscha described above, but is also visible in less tangible planning efforts and the importance of discursive and personal relations between actors. However, incorporating this complexity, non-linearity and fundamental uncertainty is a challenge. An evolutionary perspective that considers the development of leisure over the years can be beneficial to understanding processes over time. The way meaning is given to such processes by actors in leisure further shapes future development. Discourses on leisure and leisure-led regional development, which simultaneously shape and are shaped by the evolution of leisure, can therefore provide insight in the potential directions for long-term changes in leisure. Because of the plurality of processes and mechanisms influencing such changes, this also calls for a mix of planning measures and processes that can affect different aspects of development. Therefore, this paper proposes four steps in planning for leisure-led regional development, based on the experiences in Fryslân.

The first step in this planning approach deals with the institutional structures within which development takes place. A complexity perspective focuses on interactions between actors as the main drivers of uncertainty. These interactions can shape the development of a region but are (partially) bounded by the institutional structures within which they take place. As such, institutions form the ‘rules of the game’ within which complex development can take place and thereby determine which interactions can be formed and broken. In Fryslân, some interactions between leisure actors are promoted through institutional structures, whereas others are less likely to be formed. This happens through the existence of marketing agencies, subsidy programs or formal and informal networks. Such institutions can have a profound effect on the development of leisure when rooted in the interests of individual actors. Recognizing the way in which both formal and informal institutions in a region influence leisure-led regional development and using these structures as a way to influence interactions is the first step in planning for leisure-led regional development.

However, the way such institutional structures affect development is not straightforward. The second step of a planning approach to leisure-led regional development is therefore shaped by the necessity for adaptivity. Adaptivity in this perspective means the ability to adapt to changing circumstances and developments that stem from interactions within leisure. The realization that institutional structures influence the development of leisure but that the direction in which this development takes place is fundamentally uncertain requires such institutional structures to not be fixed and static. This also means that the way in which goals and ambitions are formulated should allow for this flexibility. An oversimplified framing of ambitions, for instance in terms of quantified targets such as economic spending or number of visits, can lead to a lack of adaptivity in the way in which the broader societal goals are thought to be achieved. Additionally, such framing can lead to cynicism among actors who do not recognize their own goals and ambitions in the dominant frame. The need for adaptivity that stems from uncertainty also requires a different way of operationalizing goals and targets in planning. A more qualitative approach to goals and targets, not based on statistics but on the values and meanings attached to development, is thus part of adaptivity as a second step in planning for leisure-led regional development.

Based on these ethnographies, a more qualitative approach to goals and targets also requires a different form of monitoring and evaluation, which relates to the third step of planning for leisure-led regional development. To be able to analyze how complex development relates both to past development and to qualitative goals and targets, an evolutionary analysis is needed that places development into its non-linear context. In this way, the aspect of time, which is central to both planning and complexity, is included in the planning for leisure-led regional development. For leisure, this implies incorporating the autonomous development of the leisure sector and the differences between areas with a more dynamic or more stagnant evolutionary process. Such an evolutionary analysis is not aimed at deterministic predictions of the effects of planning measures, but uncovers the mechanisms through which development and structural change takes place. In complex development processes, such as leisure-led regional development, small changes can have large effects on development as a whole. This evolutionary analysis therefore can show the asymmetry that lies at the core of uncertainty in planning. Understanding this asymmetry uncovers which planning measures may be more likely to have an effect on a structural level.

The final step of planning for leisure-led regional development focuses on the people as the driving forces of complexity. As explained above, the interactions between actors in leisure drive complex development, and it is through influencing such interactions that structural change can occur. Through an evolutionary analysis, the interactions that are most likely to affect structural change can be identified. However, a perspective that more closely includes the views, emotions and discourses of people involved in leisure is necessary the complex development of leisure is to be understood. As the example from Heerenveen shows, if the personal views and emotions of actors affect their actions and interactions. Therefore, excluding this personal level in planning efforts, this can result in skepticism among those people who could otherwise be driving forces of new and innovative development. By considering the personal views of those people most directly involved in the leisure sector, planners can be more effective in aiming for structural change or development. Additionally, the focus on the emotions and discourses of those involved in leisure highlights the temporality of meanings and values attached to leisure-led regional development. Including the personal views of actors in leisure also means taking into account the fact that both actors and the views they hold can change over time and that this can have a profound effect on the development of leisure. This means that efforts to stimulate leisure-led regional development cannot be set in stone, but should develop along with the changing conditions of the leisure sector.

Drawing on the ethnographies in this paper, a complexity perspective on planning for leisure-led regional development entails acknowledging uncertainty, rejecting simplified evaluation criteria and targets, encompassing autonomous developments and evolutionary processes and acknowledging the importance of emotions and discourses of people involved leisure in shaping interactions between actors. In the practice of planning this requires a temporal view of development, both retrospectively and in terms of planning for the future. An adaptive form of planning that can be adjusted to changing perspectives of goals and aims is needed. Discursive analysis that focuses on the emotions and discourses of people involved in leisure is required to be able to identify changing and evolving values and meanings among actors. Such discursive analysis is needed both in the designing and the monitoring and evaluation of planning efforts.

Conclusion

This paper discusses planning for leisure, describing how leisure planning has largely followed trends in spatial planning in general. Moreover, we argue for the use of a complexity perspective on leisure planning to account for the broader goals of leisure-led regional development. The paper employs regional ethnographies to explore how a complexity perspective affects planning for leisure-led regional development. The ethnographic approach used in this paper allows for a more in-depth analysis of leisure-led regional development in Fryslân than traditional qualitative approaches. The ethnographic approach not only creates a greater understanding of the mechanisms of development within the leisure sector through immersion in leisure in Fryslân, but also allows for a stronger focus on the more personal perspectives of actors. The main argument of this paper is that a complexity perspective calls for a plurality of roles for planners and policymakers in influencing autonomous developments and initiating structural change. This involves not only a more adaptive form of planning, but also a change in the way development over time is analyzed and evaluated. This is explained through the case of leisure in the Dutch province of Fryslân, analyzing its complex development and showcasing how a complexity perspective could propose an alternative approach to the practice of planning for leisure. These regional ethnographies lead to the description of a planning approach to leisure-led regional development that consists of multitude of combined strategies.

An approach to planning for leisure-led regional development based on complexity theories consists of a combination of adaptivity, evolutionary analysis and a focus on discourses which both shape and are shaped by non-linear evolutionary development. The use of a complexity perspective in both the analysis of and planning for leisure-led regional development helps mitigate the intricate matter of planning for leisure-led regional development. Such a perspective acknowledges a fundamental uncertainty in the effects of planning measures. Pessimistically, planning could then be seen as futile, but it is clear that planning efforts in the past have had results that to a large extent have also lead to desired consequences. Nonetheless, small deviations from the envisioned effects can have drastic effects, especially in the long run. A complexity perspective incorporates this fundamental uncertainty.

Based on regional ethnographies of leisure in the Dutch province of Fryslân, this paper concludes that planning for leisure-led regional development from a complexity perspective takes into account uncertainty in planning, rejects simplification through solely quantitative evaluation criteria and targets, includes autonomous and evolutionary developments and focuses on values and meanings as driving forces of interactions between actors. By not focusing on quantified targets and evaluation criteria but taking a more qualitative approach to evaluation (both ex ante and ex post) the effect of planning measures on the actual societal and developmental goals of such planning measures can be judged more comprehensively. Additionally, considering the autonomous and evolutionary processes in a region, planning measures can be more directed at the complex processes and interactions within leisure and leisure-led regional development. Finally, such interactions can be best understood by incorporating a discursive analysis that reveals how the choices of actors both shape and are shaped by the values, meanings and emotions they hold.

The main argument in this paper is that planners need to take up a plurality of roles in planning for leisure-led regional development in which people are the driving force of complexity. The acknowledgment of uncertainty that is central within a complexity perspective points to adaptive strategies, as reacting to unexpected outcomes is required. However, it is not only in outcomes that uncertainty is reflected. A complexity perspective highlights the temporal aspects of planning. This perspective calls for an analysis based on an evolutionary perspective, as well as incorporating the effect of discourses that shape the interactions between actors. Finally, the acknowledgement of uncertainty should extend to the evaluation of planning efforts. These insights are valuable in planning for leisure-led regional development, but can also be used to inform planning in a broader sense.

The results of this paper open up a number of avenues for future research. An important finding is that a complexity perspective calls for adaptivity not only in the development and deployment of planning interventions, but also in the monitoring and evaluation of these efforts. Further research should focus on how such an adaptive approach to evaluation can be achieved. A main challenge here is combining the adaptivity required with the need for (political) accountability often required in democratic processes. Furthermore, an important finding in this paper is the influence of the personal level on the interactions between actors in leisure. Further research could focus more on this personal level, for instance by exploring more thoroughly the emotions of actors in leisure and how this influences their actions. Additionally, a further exploration of combining evolutionary and discursive analysis in complexity research can provide planning practice with more tangible recommendations. This paper has provided a clear direction towards making the use of a complexity perspective more tangible for planning practice. Further research that expands on the use of complexity in planning can help both planning theory and practice further embrace uncertainty as integral part of the planning process.

Acknowledgments

This work is part of a research program which is financed by the Province of Fryslân

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Balducci, A., L. Boelens, J. Hillier, T. Nyseth, and C. Wilkinson. 2011. “Introduction: Strategic Spatial Planning in Uncertainty: Theory and Exploratory Practice.” Town Planning Review 82 (5): 481–501. doi:10.3828/tpr.2011.29.

- Block, T., K. Steyvers, S. Oosterlynck, H. Reynaert, and F. De Rynck. 2012. “When Strategic Plans Fail to Lead. A Complexity Acknowledging Perspective on Decision-Making in Urban Development Projects – The Case of Kortrijk (Belgium).” European Planning Studies 20 (6): 981–997. doi:10.1080/09654313.2012.673561.

- Boelens, L., and G. de Roo. 2016. “Planning of Undefined Becoming: First Encounters of Planners Beyond the Plan.” Planning Theory 15 (1): 42–67. doi:10.1177/1473095214542631.

- Boonstra, B. 2015. Planning Strategies in an Age of Active Citizenship. Groningen, The Netherlands: InPlanning.

- Brouder, P., S. Anton Clavé, A. Gill, and D. Ioannides. 2017. “Why Is Tourism Not an Evolutionary Science? Understanding the Past, Present and Future of Destination Evolution.” In Tourism Destination Evolution, edited by P. Brouder, S. Anton Clavé, A. Gill, and D. Ioannides, 1–18. London: Routledge.

- Bryman, A. 2008. “Ethnography and Participant Observation.” In Social Research Methods, 400–434. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Butler, R. 1980. “The Concept of a Tourist Area Cycle of Evolution: Implications for Management of Resources.” The Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe Canadien 24 (12): 5–12. doi:10.1111/j.1541-0064.1980.tb00970.x.

- Byrne, D. 2003. “Complexity Theory and Planning Theory: A Necessary Encounter.” Planning Theory 2 (3): 171–178. doi:10.1177/147309520323002.

- Chapman, G. 2009. “Chaos and Complexity.” International Encyclopedia of Human Geography 43 (4): 31–39. doi:10.1016/B978-008044910-4.00412-0.

- Chettiparamb, A. 2013. “Complexity Theory and Planning: Examining “Fractals” for Organising Policy Domains in Planning Practice.” Planning Theory 13 (1): 5–25. doi:10.1177/1473095212469868.

- Christensen, M., and P. Albrecht. 2020. “Urban Borderwork: Ethnographies of Policing.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 38 (3): 385–398. doi:10.1177/0263775820928678.

- Cilliers, P. 2005. “Complexity, Deconstruction and Relativism.” Theory, Culture & Society 22 (5): 255–267. doi:10.1177/0263276405058052.

- Costa, C. 2001. “An Emerging Tourism Planning Paradigm? A Comparative Analysis Between Town and Tourism Planning.” International Journal of Tourism Research 3 (6): 425–441. doi:10.1002/jtr.277.

- Dana, L., C. Gurau, and F. Lasch. 2014. “Entrepreneurship, Tourism and Regional Development: A Tale of Two Villages.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 26 (3–4): 357–374. doi:10.1080/08985626.2014.918182.

- De Roo, G. 2012. “Spatial Planning, Complexity and a World ‘Out of Equilibrium’ Outline of a Non-Linear Approach to Planning.” In Complexity and Planning; Systems Assemblages and Simulations, edited by G. De Roo, J. Hillier, and J. Van Wezemael, 129–165. Farnham: Ashgate Publishers.

- De Roo, G. 2017. “Ordering Principles in a Dynamic World of Change – On Social Complexity, Transformation and the Conditions for Balancing Purposeful Interventions and Spontaneous Change.” Progress in Planning 125: 1–32. doi:10.1016/j.progress.2017.04.002.

- Denzin, N., and Y. Lincoln (Eds.). 2018. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Dobrucká, L. 2016. “Reframing Planning Theory in Terms of Five Categories of Questions.” Planning Theory 15 (2): 145–161. doi:10.1177/1473095214525392.

- Ecorys. 2009. Study on the Competitiveness of the EU Tourism Industry (Issue September). http://ec.europa.eu/DocsRoom/documents/1556/attachments/1/translations/en/renditions/native.

- Farsari, I., R. Butler, and E. Szivas. 2011. “Complexity in Tourism Policies.” Annals of Tourism Research 38 ((3): 1110–1134. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2011.03.007.

- Gerrits, L. 2008. The Gentle Art of Coevolution. Rotterdam: Erasmus University.

- Harrison, P. 2013. “Making Planning Theory Real.” Planning Theory 13 (1): 65–81. doi:10.1177/1473095213484144.

- Hartman, S. 2015. “Towards Adaptive Tourism Areas? A Complexity Perspective to Examine the Conditions for Adaptive Capacity.” Journal of Sustainable Tourism 24 (2): 299–314. doi:10.1080/09669582.2015.1062017.

- Hartman, S., and G. De Roo. 2013. “Towards Managing Nonlinear Regional Development Trajectories.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 31 (3): 556–570. doi:10.1068/c11203r.

- Hartman, S., C. Parra, and G. de Roo. 2015. “Stimulating Spatial Quality? Unpacking the Approach of the Province of Friesland, the Netherlands.” European Planning Studies 24 (2): 297–315. doi:10.1080/09654313.2015.1080229.

- Healey, P. 1992. “Planning Through Debate: The Communicative Turn in Planning Theory.” The Town Planning Review 63 (2): 143–162. doi:10.3828/tpr.63.2.422x602303814821.

- Heslinga, J., P. Groote, and F. Vanclay. 2018. “Understanding the Historical Institutional Context by Using Content Analysis of Local Policy and Planning Documents: Assessing the Interactions Between Tourism and Landscape on the Island of Terschelling in the Wadden Sea Region.” Tourism Management 66: 180–190. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2017.12.004.

- Heylighen, F., P. Cilliers, and C. Gershenson. 2007. “Complexity and Philosophy.” In Complexity, Science and Society, edited by J. Bogg, and R. Geyer, 117–134. Abingdon: Radcliffe Publishing.

- Hillier, J. 2008. “Plan(e) Speaking: A Multiplanar Theory of Spatial Planning.” Planning Theory 7 (1): 24–50. doi:10.1177/1473095207085664.

- Hodgson, G. 2006. “What Are Institutions?” Journal of Economic Issues 40 (1): 1–25. doi:10.1080/00213624.2006.11506879.

- Jamal, T., and D. Getz. 1995. “Collaboration Theory and Community Tourism Planning.” Annals of Tourism Research 22 (1): 186–204. doi:10.1016/0160-7383(94)00067-3.

- Jeuring, J. 2015. “Discursive Contradictions in Regional Tourism Marketing Strategies: The Case of Fryslân, The Netherlands.” Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 5 (2): 65–75. doi:10.1016/j.jdmm.2015.06.002.

- Ma, M., and R. Hassink. 2013. “An Evolutionary Perspective on Tourism Area Development.” Annals of Tourism Research 41: 89–109. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2012.12.004.

- Marcus, G. 2012. “Multi-sited Ethnography: Five or Six Things I Know About It Now.” In Multi-Sited Ethnography, edited by S. Coleman and P. von Hellerman, 24–40. London: Routledge.

- Martin, R., and P. Sunley. 2007. “Complexity Thinking and Evolutionary Economic Geography.” Journal of Economic Geography 7 (5): 573–601. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbm019.

- Martin, R., and P. Sunley. 2015. “Towards a Developmental Turn in Evolutionary Economic Geography?” Regional Studies 49 (5): 712–732. doi:10.1080/00343404.2014.899431.

- McDonald, J. 2009. “Complexity Science: An Alternative World View for Understanding Sustainable Tourism Development.” Journal of Sustainable Tourism 17 (4): 455–471. doi:10.1080/09669580802495709.

- Meekes, J.F., D.M. Buda, and G. De Roo. 2017a. Adaptation, interaction and urgency: a complex evolutionary economic geography approach to leisure. Tourism Geographies 6688(May), 1–23. doi:10.1080/14616688.2017.1320582.

- Meekes, J., D. Buda, and G. De Roo. 2017b. “Leeuwarden 2018: Complexity of Leisure-Led Regional Development in A European Capital of Culture.” Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie 108 (1): 129–136. doi:10.1111/tesg.12237.

- Meekes, J., D. Buda, and G. de Roo. 2020. “Socio-spatial Complexity in Leisure Development.” Annals of Tourism Research 80: 102814. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2019.102814.

- Meekes, J.F., C. Parra, and G. De Roo. 2017. Regional development and leisure in Fryslân: a complex adaptive systems perspective through evolutionary economic geography. In Tourism Destination Evolution, edited by Patrick Brouder, Salvador Anton Clavé, Allison Gill, Dimitri Ioannides, 165–182. London & New York: Routledge.

- Milne, S., and I. Ateljevic. 2001. “Tourism, Economic Development and the Global-Local Nexus: Theory Embracing Complexity.” Tourism Geographies 3 (4): 369–393. doi:10.1080/146166800110070478.

- Olssen, M. 2008. “Foucault as Complexity Theorist: Overcoming the Problems of Classical Philosophical Analysis.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 40 (1): 96–117. doi:10.1111/j.1469-5812.2007.00406.x.

- O’Sullivan, D. 2009. “Complexity Theory, Nonlinear Dynamic Spatial Systems.” In International Encyclopedia of Human Geography, edited by Rob Kitchin, Nigel Thrift, 239–244. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Provincie Fryslân. 2015. Fryslân in cijfers [Fryslân in Numbers]. Leeuwarden: Provincie Fryslân.

- Rauws, W., M. Cook, and T. Van Dijk. 2014. “How to Make Development Plans Suitable for Volatile Contexts.” Planning Practice and Research 29 (2): 133–151. doi:10.1080/02697459.2013.872902.

- Russell, R., and B. Faulkner. 1999. “Movers and Shakers: Chaos Makers in Tourism Development.” Tourism Management 20 (4): 411–423. doi:10.1016/S0261-5177(99)00014-X.

- Saarinen, J., C. Rogerson, and C. Hall. 2017. “Geographies of Tourism Development and Planning.” Tourism Geographies 19 (3): 307–317. doi:10.1080/14616688.2017.1307442.

- Speakman, M. 2016. “A Paradigm for the Twenty-First Century or Metaphorical Nonsense? the Enigma of Complexity Theory and Tourism Research.” Tourism Planning & Development 14 (2): 282–296. doi:10.1080/21568316.2016.1155076.

- Stebbins, R. 1982. “Serious Leisure: A Conceptual Statement.” The Pacific Sociological Review 25 (2): 251–272. doi:10.2307/1388726.

- Stichting Kulturele Haadstêd. 2013. iepen mienskip Leeuwarden-Ljouwert’s application for European Capital of Culture 2018. Leeuwarden: Stichting Kulturele Haadstêd Leeuwarden-Ljouwert 2018.

- Suteanu, C. 2005. “Complexity, Science and the Public: The Geography of a New Interpretation.” Theory, Culture & Society 22 (5): 113–140. doi:10.1177/0263276405057196.

- Zahra, A., and C. Ryan. 2007. “From Chaos to Cohesion – Complexity in Tourism Structures: An Analysis of New Zealand’s Regional Tourism Organizations.” Tourism Management 28 (3): 854–862. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2006.06.004.