ABSTRACT

Marine Spatial Planning is labelled as ‘an idea whose time has come’ based on its applicability to address spatial conflicts and deliver sustainable use. Legislation such as the EU MSP Directive 2014/89/EU and the UK Marine and Coastal Access Act 2009 requires that neighbouring marine spatial plans are coherent and coordinated to address cross-border issues. However, the implementation of MSP in cross-border areas is complex due to different administrative processes, fiscal and legislative procedures. This study argues that cross-border MSP is challenging in areas that are faced with historically contested borders which limit effective delivery of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Two contested case study regions: Germany, Poland and the island of Ireland are compared. To help understand contemporary issues, a bespoke theoretical evaluative framework, the ‘Wheel of Integration and Adaptation’ is used to identify the challenges of cross-border MSP. An in-depth review of planning documents, policies, legislation was undertaken alongside interviews. This demonstrated that in contested areas, cross-border MSP must contend with the following challenges: ‘inter alia’ geographical peripheries syndrome, schema overload, limited transparency and blue justice, diplomatic consultation processes and differences in planning philosophies. This paper concludes by presenting five interventions as steps toward advancing cross-border MSP.

1. Introduction

Cross-border marine areasFootnote1 are faced with ‘marine problems’ which are multifaceted, wicked and complex with no optimal or single solution (Peel and Lloyd, Citation2014; Jentoft and Chuenpagdee, Citation2009; Ritchie and McElduff Citation2020). These problems span from deteriorating marine environments, biodiversity loss, climate change, marine pollution, competition for marine space, intensification of economic use of marine space, institutional fragmentation to limited capacity to address these problems (Ritchie and Ellis Citation2010). Although these marine problems occur in national waters they are exacerbated in cross-border areas due to fragmented cross-border processes, competing national interests, differing legislative and fiscal arrangements (Flannery et al. Citation2015). An assessment by Kuempel et al. (Citation2019) found that 63.4% of marine areas that are ecologically threatened occur in cross-border areas, when compared to areas in a single country. Moreover, 55% of maritime boundaries (228 boundaries) in the world are contested (Østhagen Citation2019). The World Ocean Assessment II (UN Citation2021) highlights that in such contested marine areas, access to resources, blue justice, marine policies and agreements focused on sustainability are often undermined. The EU MSP Directive 2014 and the UK Marine and Coastal Access Act 2009 require that Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) authorities ensure that marine spatial plans are coordinated and coherent with neighbouring plans to address these ‘marine problems’. However, ensuring contested areas are effectively planned is challenging, not least due to geopolitical differences and conflicts over resources especially in Europe (Twomey Citation2020; Jay et al. Citation2016). Thus one of the key problems of cross-border marine areas seems to be related to incompatibilities between institutional structures underpinning MSP.

MSP is both a national competence, and a political process, with a focus on the development of national and subnational plans (McAteer et al. Citation2022). In most cases, decisions relating to MSP are being made in urban and political centres, situated some distance from cross-border and contested areas. This renders them as unattended and geographical peripheries (Ehler, Zaucha, and Gee Citation2019). Maritime jurisdiction and border discussions are led by Ministries of Foreign Affairs of the respective country, beyond planning competence. Records documenting border discussions are often embargoed and thus nebulous to the public, further limiting synergies with MSP and decision making (Ansong, Ritchie, and McElduff Citation2022). The right for residents and citizens to directly participate in a neighbouring country’s planning process, which might affect them, is not clearly defined in international legislation MSP policies. For instance, VASAB-HELCOMFootnote2 guidelines on transboundary consultation, public participation and cooperation 2019 leave who should be informed and invited for consultation at the full discretion of the competent MSP authorities of the neighbouring countries. There is a historical gap in ocean science diplomacy capacities between which influences which State has better evidence for cross-border negotiations (Polejack Citation2021).

The logic of maritime delimitation emerged in the 1400s with European colonialism. The United Nation Convention of the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) 1982 and marine management approaches introduced after that have been structured around demarcating sea spaces like land (Peters Citation2020; Fairbanks et al. Citation2018). Subsequently, cross-border spatial planning has largely been considered in terrestrial planning domains whereas for marine space it is just emerging (Faludi Citation2013; Rauhut, Sielker, and Humer Citation2021). The fluidity and dynamism of the marine realm present different challenges for institutions and actors in planning cross-border areas. Faludi (Citation2019) notes that MSP is burdened with territoriality, which is the building block of the political order in a nation-state system and creates a delusion of territorial sovereignty. An integrated cross-border MSP, therefore, remains a planner’s dream with limited practicality. In recent years, MSP research has begun to consider its transboundary dimension (see Ansong et al., Citation2021; Giacometti et al. Citation2017). Research about the unique attributes of cross-border areas is needed due to issues of colonialism, jurisdictional disputes and geopolitical differences.

This paper seeks to address current knowledge gaps about institutional challenges of cross-border MSP (Ansong et al. Citation2021; Spijkerboer Citation2021; Kelly, Ellis, and Flannery Citation2018), limited comparative research in this area of MSP (Chalastani et al. Citation2021) and limited application of theories to planning cross-border marine areas (Wang et al. Citation2022; Morf et al. Citation2022). Contested and disputed maritime jurisdiction is raised as a critical factor influencing the effective delivery of global sustainability goals and international commitments such as United Nation (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and Ocean Decade. This paper explores contemporary challenges of planning cross-border areas and dealing with contested maritime jurisdictional issues by developing a bespoke research approach (Section 2). It further explores how contested maritime jurisdictional issues serve as a barrier in delivering coherence in MSP. It does so by presenting an overview of two case studies in Section 3 and discusses the perspectives of key stakeholders on the Island of Ireland (IOI) and the Pomeranian Bay (between Germany and Poland) where MSP must contend with maritime jurisdictional issues. Section 4 compares the MSP systems to understand the differences and similarities in approaches, how MSP has considered contested borders and ownership issues. Recognizing that there is no one size fits all approach to resolving such issues, Section 5 identifies pathways to inspire and serve as the basis for discussions and action towards integrated cross-border MSP.

2. Research approach

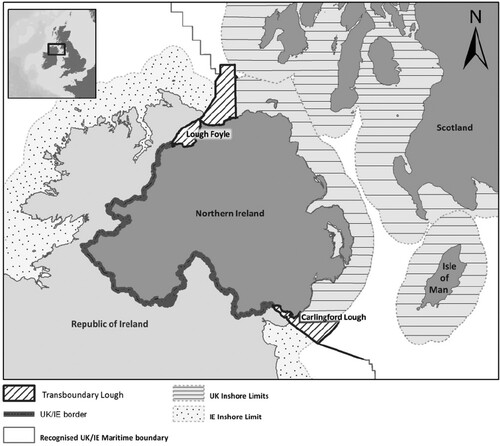

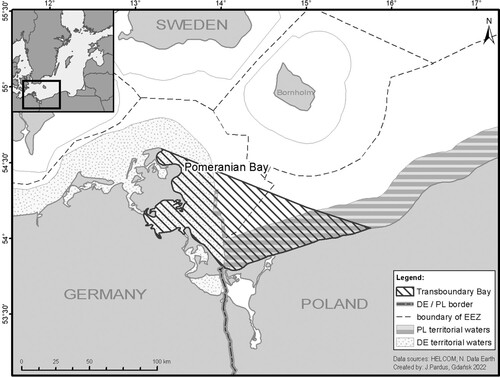

The research approach used for this study was categorized into four phases: (a) selection of case studies; (b) contextual and document analysis; (c) semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders and (d) comparative analysis of case studies. The first phase of the research design included establishing case study selection criteria. Following Carneiro et al. (Citation2017), the criteria includes existential drivers, issues and goals for MSP; advanced status of implementation, scope of MSP, collaboration and consultation involved in the MSP planning phase and emerging outcomes and lessons for effective MSP. The IOI (Carlingford Lough and Lough Foyle) and Pomeranian Bay ( and 3 below) were selected as they share similar contextual features, such as, sectoral conflicts, a contested ownership of water body and unclear border due to drivers such as colonialismFootnote3 or the redefinition of country borders. Of importance to this study, MSP is at a matured stage in both cases as Germany and the UK started their MSP processes before the MSP Directive in 2014 and are seen as frontrunners in the deployment of MSP.

The second phase included a contextual document analysis that examined the socio-economic and biogeographical context of each case. The document analysis considered the marine governance architecture, cross-border integration mechanisms and coherence between marine spatial plans based on the HELCOM/VASAB (Citation2022) guidance for the assessment of cross-border coherence in MSP.

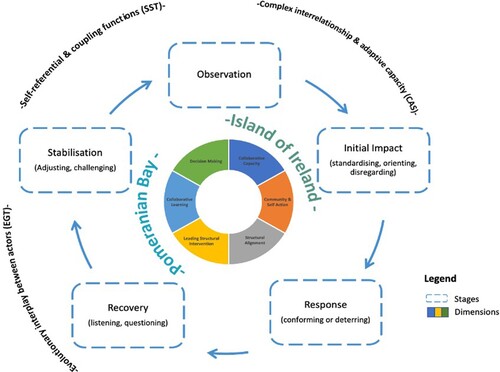

The third phase of the research involved semi-structured interviews conducted with key stakeholders. The ‘Wheel of Integration and Adaptation’ presents an evaluative framework consisting of stages of institutional integration (observation, initial impact, response, recovery and stabilization) and six dimensions that can influence activities at each stage (Ansong et al., Citation2021). The interview questions were therefore designed based on six dimensions that are proposed by the ‘wheel’ ().

Table 1. Dimensions of institutional integration forming the analytical framework for the study.

Purposeful sampling and snowball technique were used to identify relevant interview participants. The interviews were conducted remotely between March 2020 to March 2021. A total of 33 in-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted on the IOI and 7 in Pomeranian Bay (). Interviews were conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic which contributed limitations in recruiting interviewees due to social distancing regulations, potential participants on leave, furlough and language barriers for the Pomeranian Bay case study. Moreover, some stakeholders were unwilling to discuss issues considered by them as purely political where they have little possibility of influence, especially in the Polish case. All interviews were transcribed and analysed with the aid of QSRNVivo12. The interviews were inductively analysed to identify challenges and opportunities for cross-border MSP.

Table 2. Breakdown and number of Interviewees.

A comparative analysis was employed to map out and juxtapose the findings from desk analysis and semi-structured interviews on tables for case studies. This allowed the identification of differences and similarities between the two cases. The comparative analysis was further extended by using the ‘Wheel of Integration and Adaptation’ to evaluate the level of cross-border MSP integration.

3. Context and stakeholder perspectives on cross-border MSP

This section presents an overview of cross-border MSP first for the IOI followed by the Pomeranian Analysis of the context and planning documents is first discussed and followed by empirical evidence from interviews.

3.1. MSP on the island of Ireland

The IOI is a single biogeographic unit that comprises the Republic of Ireland (ROI) with 26 counties and Northern Ireland (NI) with 6 counties which is a devolved administration of the United Kingdom and Northern Ireland (UK) (). Approximately 43% of the population lives around the cross-border loughs of Lough Foyle and Carlingford Lough, the most deprived areas on the IOI (NISRA Citation2017). Both ROI and the UK claim ownership of the entire Loughs and neither country accepts the other country's position.Footnote4 The jurisdictional border that lies in the cross-border Loughs stops at the territorial sea between NI and the ROI.

The National Marine Planning Framework (NMPF) was published in July 2021 and led by the Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage (DHLGH) as Ireland’s first national framework for planning marine activities. The NI Department of Agriculture Environment and Rural Affairs (DAERA), under the Marine Act (NI) 2013, has prepared a draft Marine Plan NI (dMPNI) in 2018. However, the plan is yet to be published, amidst power struggles between unionist and nationalist parties, the lack of NI Executive, Brexit and the COVID-19 pandemic (Ritchie et al.,Citation2022). Overall, both plans largely take a policy-based, high-level, strategic and cascading approach, signifying some degree of coherence.Footnote5 The spatial aspect of both national plans is limited to existing uses, with little detail on policies for future allocations of marine activities.

The NMPF defines an overarching transboundary policy that emphasizes the importance of transboundary consultation for projects that might have transboundary environmental impacts. Whilst, the dMPNI does not define a specific transboundary policy, appropriate transboundary consultations are referenced under Air Pollution, Coastal Processes, Water Quality policies, to be considered where projects may have transboundary effects. Critically, both plans presented vague transboundary policies to address issues in both Loughs and jurisdictional issues were simply noted as outstanding and unresolved. For example, the NMPF (DHLGH Citation2021) states that:

The resolution of jurisdictional issues in Lough Foyle and Carlingford Lough remains outstanding. Following discussions in 2011 between the Minister for Foreign Affairs and the British Foreign Secretary, the UK and Irish Governments agreed to seek to resolve these issues. Since then, a series of meetings have taken place at official level between the Department of Foreign Affairs and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. (p.22)

However, these jurisdictional issues have contributed to several conflicts. One of many examples is the proliferation of unregulated oyster farming on the ROI side in Lough Foyle of which has had an adverse impact on both the marine environment and coastal communities. Specifically, the lack of husbandry, regulation and management has led to the spread of Bonamia ostreae which is a shellfish pathogen associated with pacific oyster production. Unlicensed oyster trestles, visibly in view of the public highway, along Lough Foyle have grown from around 2500 in 2010 to around 50,000 in 2018 with an estimated worth of £20 million if properly licensed. This has contributed to limited space for brent geese to feed, as well as increasing resource conflicts especially from the year 2000, in tandem with the introduction of pacific oyster farming. Resolving these long-standing issues would require recommencing actual bilateral negotiations and agreeing to commence the relevant parts of the Foyle and Carlingford Fisheries (NI) Order 2007 and Foyle and Carlingford Fisheries Act 2007 in the ROI. This will provide additional legal functions for aquaculture management by Loughs Agency (LA)Footnote6 in both Loughs.

From an MSP perspective, an inter-organizational MSP group was formed in 2018, led by ROI, with the five other marine planning authorities (NI, Wales, England, Scotland and Isle of Man) of the Irish Sea. However, the inception of the COVID-19 pandemic, Brexit, and the prioritization of national MSP implementation have paused the activities of the group. This group was high-level, without local, business nor community interest representation. Most stakeholders interviewed therefore noted that there are no extensive mechanisms in place for cross-border engagement on MSP:

When it comes to cross-border engagement, there is nothing or almost nothing. (Business Enterprise 1, NI)

Most stakeholders noted that MSP Advisory and inter-organizational groups were not tasked with specific outcomes and lacked indication of how the views of stakeholders and experts were taken on board. Subsequently, they are viewed as ‘talking shops’:

One of the problems in that group is you never really knew to what extent your thoughts were being taken on board … it had different interests represented, but it was more a mechanism for government to tell you what they were doing rather than to take your experience and feed it into how they were going to do things … It was advertised and heralded as an ‘Advisory Group’, but we could not advise. (Academia 3, ROI)

Communicating the tangibility and practical value of MSP was raised as a challenge that is exacerbated in cross-border areas by interviewees. Furthermore, its delivery and influence on the management of the contested areas were questioned:

I think one of the issues that’s becoming more apparent now is just what exactly the plans are going to do at a practical level. So, they [plan policies] may be quite good at the strategic level, but for practical activities my impression is people in different sectors can’t see how that’s going to have relevance. (Academia 3, ROI)

In Carlingford Lough, confusion and tension have arisen over the exclusion of local stakeholder in cross-border consultation as exemplified by the construction of a carbon dioxide (CO2) gas import and distribution terminal at Warrenpoint port:

We found out that people in Omeath, on the Carlingford side [ROI] were not included in a lot of the assessments that were done [for CO2 plant application]. They fail to recognise them as residents in the visual impact that the CO2 plant was having. So, our planning legislation here is not considering the people across the border and that’s wrong. (eNGO 4, NI)

The limited engagement of coastal communities in MSP was identified as a critical weakness given the valuable experience and knowledge residents and community groups have regarding the marine environment. Critically, even when their views were invited, it was reported that they find consultation materials too technical for them to understand and provide meaningful input:

I am aware of it [MSP consultation]. I just felt very overwhelmed by the questions they were asking, and I didn’t really understand the questions. I just didn’t feel it was a public consultation for the community. It’s more specialised to certain backgrounds. You can’t present the community with a complex, overwhelming question. I’m very connected to the marine environment here and I just didn’t think I even had the competency to fill something like that in. (eNGO 4, NI)

Mapviewers such as the Marine Irish Digital Atlas and Ireland's Marine Atlas in ROI existed before the inception of MSP and were mainly designed for Marine Strategy Framework Directive compliance (Ansong, Ritchie, and McElduff Citation2022). Yetlack of understanding and appreciation of MSP issues by stakeholders were identified as a barrier by government officials:

The challenge is, you are starting from a lower knowledge base in terms of people knowing about subjects or being comfortable with putting in place policies to deal with things. So, you must do more of the legwork to get people up to scratch and build that knowledge. You just got more miles to tread. (Public Agency 3, ROI)

Local Authorities in cross-border regions noted limited capacity and skills to carry out their new remit for regional MSP under the NMPF and to further consider cross-border issues:

There are no resources available to deal with a lot of implementation issues arising from the NMPF especially technical marine expertise … This goes beyond existing local authority structures. (Local Authority 1, ROI)

As an all-island institution, the LA could offer a more integrated approach to managing and planning the Loughs. However, their role is limited by a lack of political leadership:

There needs to be high-level agreement about how our officials and politicians see the Loughs being used. There needs to be a bit more direction about priorities in the loughs. Is it fishing or aquaculture? Is it shipping? What is the direction? In terms of where they see the loughs being 10, 20 years? (Public Agency 4, NI)

Most interviewees also noted that there is a lack of transparency in their engagement with stakeholder and users of the Loughs:

I always find the Loughs Agency difficult to deal with to be honest. They are friendly but they are not that open. Everyone there is constantly looking over their shoulder and very careful with what they say. (Business Enterprise 2, ROI).

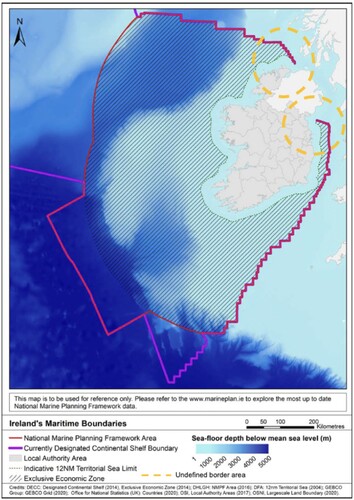

Overall, these first-generation marine plans on the IOI sets high-level Government's vision, objectives and marine planning policies for marine activities. Both plans grey out the contested area without making any designation or planning consideration (). The lack of ambition by both governments to address ownership issues, tensions between stakeholders on both sides of the border, and long-standing environmental management issues have hindered effective MSP.

Figure 2. Republic of Ireland Marine Plan Area.Source: Adapted from DHLGH (Citation2021) to show the undefined border and contested area in dashed circles.

3.2. MSP in Poland and Germany: Pomeranian Bay

The Pomeranian BayFootnote7 is situated between Adlergrund and Oder Estuary between Mecklenburg-Vorpommem (Germany) and West Pomerania region (Poland) (). The GDP per capita for Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (M-V) is €25,400 and €18,100 in West Pomerania which are both lower than the EU 27 average of €27,640 (Eurostat Citation2020). The Baltic Sea has a long-standing history of transboundary cooperation on environmental and spatial issues. They have institutional frameworks such as HELCOM established in 1974, a joint VASAB-HELCOM Working Group on MSP, as well as a wide range of transboundary MSP projects that have taken place between 2006 and 2022, implemented ‘inter alia’, developing knowledge, methodologies and enhancing cross-border MSP discourse. At a regional level, Poland and Germany have established an MSP working group in 2014 under the German-Polish Spatial Planning Committee (GPSPC) to support knowledge exchange and intensified cross-border cooperation on MSP strategies and consultations.

Figure 3. The Pomeranian Bay and unclear maritime border at the northern approach to seaports in Poland highlighted in deep dashed lines.

Both countries claim jurisdiction over the northern approach to the port of Świnoujście and Szczecin (in Poland). The contested area partly falls in an area demarcated by the German State as part of the German EEZ but hosts anchorages and access to the ports of Szczecin and Świnoujście, which are in the Polish State. Poland makes their claim to the area based on the ‘Agreement between the Polish People’s Republic (PRP) and the German Democratic Republic (GDR) on the Delimitation of the Sea Areas in the Oder Bay’ on 22 May 1989 which states that:

The section of the Northern Approach to the ports of Szczecin and Świnoujście which is situated east of the outer limit of the territorial sea of the German Democratic Republic as defined in Article 3 of the present Treaty and anchorage No. 3 shall not constitute continental shelf, fishery zone or potential exclusive economic zone of the German Democratic Republic.

Although the Treaty clarified that the anchorages do not constitute continental shelf or EEZ for the GDR, it still did not resolve the border issue. It does not categorically state which areas Germany can claim as territorial waters. Historically, this led to a series of reported cases of ramming Polish boats and yachts by the GDR between 1985 and 1989 (Jackowska Citation2008). On the Polish side, a key current concern is to secure access to the aforesaid ports, which requires regular dredging activities. There are also plans to expand port container facilities. On the German side, key interests are military use and Natura 2000 sites, which protect bird species and harbour porpoises. Beyond these interests, the disputed Nord Stream and Nord Stream 2 gas pipelinesFootnote8 are situated close to the contested area. The expansion of container terminals at the port of Świnoujście, the Nord stream pipeline, dredging of the shipping channel and their impact on the environment have been raised and campaigned against by the German Green Party and residents in Usedom (Emerging Europe Citation2021). Although German EEZ plan secures the access to the Polish ports, due to other governance processes, beyond MSP, the northern approach to the port of Świnoujście and Szczecin has been designated as a German nature reserve which makes dredging and shipping problematic (Giacometti et al. Citation2017).

The three marine plansFootnote9 covering the contested northern approach have been prepared by five different authorities: the Federal Maritime and Hydrographic Agency (BSH) for the German EEZ, the Ministry for Energy, Infrastructure and Digitalization for the state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (M-V) in Germany, and the Directors of Maritime Offices in Gdynia, Słupsk, Szczecin in Poland. In Germany, MSP competences and functions are distributed across Bund (Federal) and Länder levels (Jay et al. Citation2012). The second-generation MSP for the German EEZ in the North and Baltic Sea was adopted in 2021, whilst the current Spatial Development Programme Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (LEP M-V) which borders the Pomeranian Bay and covers territorial waters was adopted in 2016. The Polish maritime national plan (the Maritime Spatial Plan of Polish Sea Areas in the scale 1: 200,000, 2021) covers the entire EEZ and territorial sea and the internal sea waters apart from ports and lagoons. Beyond different plans covering the contested area, there are differences in the governance architecture of the countries:

It took us 10 years to learn that we are working in two different systems. Poland has a centralised system and Germany a federal system. For me as a person working on the regional level, 10 or 15 years ago I had to approach the competent ministry in Warsaw, Poland. For the Polish colleagues that would have been something of disrespect because that’s just a person from the regional level. (Public Agency 2, Germany)

This illustrates that these differences are difficult for the two sides to work with because of the multiple layers involved, including different planning traditions, governance traditions and administrative procedures. It follows that such differences take time (in this case 10 years) to manifest and understand, which makes it difficult to develop tailored measures to address them. Both Germany and Poland highlighted the importance of the continuity of planning staff on both sides of the border to build personal relations, trust and mutual understanding overtime:

Clearly what helps is this continuity of staff and people who have been there for a while. It’s also personal contacts between these key players. It is important in terms of trust. (Academic 2, Germany)

However, such relations are sometimes complicated by differences in national language:

Let’s say scientists at the national level [in Poland] can speak English but the local politicians say they don’t know English, so we had a problem. The same problem exists in Germany as English is very unpopular. So even at the Länder (regional) government, it’s not so easy to find a person speaking English. (Academia 1, Poland)

Beyond language barriers, most interviewees argued that the plans are not easy to understand:

It’s [German plans] not so easy to understand. It’s a very legal language. It’s very German planning law, so you might not get a good understanding right away if you read it. (Public Agency 1, Germany)

It could be argued that if even German speakers find the plan to be complex, then it must be incredibly difficult for a non-native speaker to understand the plan especially during international consultations. Beyond that, there are existing challenges in engaging and ensuring representation by coastal authorities and communities. In Germany, it was noted that there are differences between the federal and regional planning processes as they address different stakeholders. For example, although the state/regional plan has direct local involvement, the EEZ/federal plan does not primarily address coastal residents, although they can comment:

You know, technically speaking, the plans [German EEZ and German MV] may be coordinated. But there’s no dialogue happening. At least you need to have that dialogue to discuss issues that will affect both. Whether it’s cables or whatever that just does not seem to be happening. It’s all a very formal process. And if there is dialogue happening behind the scenes, then there’s no transparency. (Consultant 1, Germany).

A similar challenge was raised by some stakeholders during cross-border and international consultations:

In our national process we have some [representation from coastal communities], but not very many representations from counties along the coast. But when it comes to cross-border consultation [Poland consulting Germany on their plans], there’s almost nothing coming up from our coastal communities. (Public Agency 1, Germany)

Outside MSP, consultation on transboundary projects goes between the national contact person and between lead authorities. Coastal communities and residents are not able to directly engage in cross-border consultation. For example, in the case of the container terminal expansion at the port of Świnoujście (Poland) and its potential impact on tourism in Usedom (Germany), one interviewee noted:

On the Polish side in the port of Świnoujście, there is a plan for a large container port. On the German island of Usedom which is nearby, the main economic focus is tourism. They are now concerned that the container port 5 km from the border might have an impact on the tourist activities and possible environmental effects. They [residents] would like to get more involved in the debate. The way we do these cross-border consultations in the SEA or EIA framework does not foresee that there is a direct interaction between the Polish planner and the German people. It all goes over to the responsible agencies. There is no direct consultation event where you could just participate. (Public Agency 2, Germany)

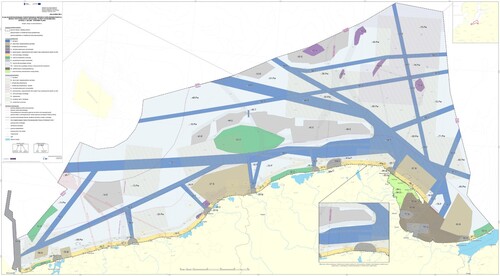

In cross-border areas, such tensions are escalated at the community level and during stakeholder engagement. The MSP process must contend with such tensions and explore approaches for cooperation and coherency. Both the German and Polish maritime spatial plans are coherent from a planning philosophy perspective as they apply a zoning and regulatory approach. Critically, there are differences in how the contested area (215.76 km2) is represented. Whilst the German EEZ plan uses a fuzzy approach without designating uses for the contested area, the Polish plan makes a port function designation (POM.01.Ip). The POM.01.Ip basic function is the functioning of a port or haven to ensure safe access and development of the ports in Szczecin and Świnoujście. This has led to different MSP approaches for the contested area and subsequent tension between planners in each jurisdiction:

It is kind of a disputed area, and you know in a Polish plan, the whole grey colour means that this is a port function, so you can see that it looks strange because a huge area, even going through the EEZ, has been given a function of port, not transportation function. Poland did not solve very much of the transboundary issue, or rather strengthen the discussion. Unfortunately, the plan is a mixture of the good sense of planners and the crazy sense of politicians. I think that this port function is something that ruins everything. (Academic 2, Poland).

It can be argued that the function of transport/shipping by the Polish side would indirectly support the current use of the disputed area as a roadstead.Footnote10 However, although planners from both sides of the border agreed on a technical and practical way forward for addressing the contested area in MSP, this solution did not move up to a higher political level. Thus the border issue remains unclarified. From a sea basin-wide perspective, it was noted that transboundary processes through the HELCOM-VASAB frameworks are slow and largely voluntary limiting coherency in MSP:

It is a slow process [HELCOM-VASAB] and so they have taken years to come up with a [transboundary] position on MSP … ., and it’s a voluntary recommendation. Which I think is a pity, but there is still room for improvement. (eNGO 1, Baltic Sea)

Overall, concrete outcomes to address MSP issues and guide the management of the contested area are yet to be achieved for the Pomeranian Bay as the Polish plan makes spatial designation of ports for the contested area, whilst the German EEZ and Länder plans make no designation ().

Figure 4. The Maritime Spatial Plan of Polish Sea Areas on a scale of 1: 200,000.

Source: Adapted from Polish Maritime Administration (Citation2021) to highlight the port function designation for the contested area.

4. Comparative discussion

The outcomes of the document review and semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders for the two case studies present the following findings:

First, findings show that whilst contested borders and maritime conflicts are pronounced at the local level, they are distant from political and government officials who are responsible for acting on such issues. In the Pomeranian Bay, international discussions about the contested area and related conflicts occur between Foreign Offices in Berlin and Warsaw while agencies responsible for plan preparation are in Hamburg and Szczecin respectively. Moreover, regional governments in both countries have not been actively engaged in resolving border disputes, nor have they actively pushed for a resolution for the contested area. Similarly, for the IOI’s loughs, maritime boundary negotiations occur between the Irish and UK Governments in Dublin or London, over 200 and 600 km, respectively. This finding is illustrative of arguments by other authors who found that border areas are often geographically and politically peripheral to administrative capitals, thus limiting their capacity to influence decision making (Guo Citation2018; Cons and Sanyal Citation2013; Wilson and Donnan Citation2012). The challenge of geographical peripherality is exacerbated by the fact that MSP occurs offshore with limited engagement of communities within the MSP process. Moreover, MSP and its cross-border dimension is a minor policy area and normally not a ‘vote winner’ for politicians. The potential for ‘schema overload’ and ‘firefighting’ approach is prominent where planners have too many pressing day-to-day issues but cannot have time to plan strategically and address the source of these cross-border issues (Gottfredson and Reina Citation2020).

Second, the geopolitical legacy and history of contested areas have created path-dependent factors, influencing institutions and approaches to planning. On the IOI, the geopolitical history, and sensitivities about the ownership of the Loughs play out in the limited transparency between the LA and stakeholders. Findings from the interviews indicate that stakeholders from ROI felt the LA is NI centred, and there is a lack of transparency when engaging with stakeholders. From a biogeographical point of view, most of the Foyle and Carlingford catchment falls within the NI jurisdiction compared to the ROI. This might explain why stakeholders from ROI have such view about LA. In the Pomeranian Bay, path-dependent factors were evident in how Poland represented the contested border differently in their plan. Although there is a long-standing cooperation between Germany and Poland, these cooperation structures could not influence an agreement on how the contested area should be represented. Both countries took different approaches in the designation of the contested area. The Polish plan made a spatial designation of ports for the contested area, whilst the German EEZ and Länder plan greys the area without any designation (). German planners felt there was an informal agreement with the Polish not to designate any use for the area. Eventually, this informal agreement did not find its way into the Polish MSP.

Third, the type of planning philosophy and culture prevalent in each country can influence how cross-border issues are considered in the plan. In the Pomeranian Bay, the zoning approach used by both Poland and Germany is more technical and detailed than the IOI cases. Both Germany and Poland term their planning process as ‘Maritime Spatial Planning’ with specific focus on the spatial aspects of the plan. This allows for specific cross-border issues (the transboundary impact of designated areas) to be identified and discussed during international MSP consultation. In comparison, ROI’s NMPF and NI’s dMPNI are both strategic, high level and mainly use cascading policies. These plans do not by themselves demarcate spatial designations for marine and coastal sectors. Although the NMPF recommends that DMAPs (locally zoned areas) can be proposed by government departments, the marine plan is a high-level strategy. Reflecting this omission of spatial aspects, and their focus on how policies can be used to guide the location of a project, both NI and ROI term their planning process as ‘Marine Planning’. Although the UK and Irish planning cultures across borders align, the discretionary nature of marine plans makes its approach less technical and more flexible. It rarely identifies, or addresses, specific cross-border issues especially for infrastructure projects that span multiple maritime jurisdictions, such as offshore grid connection.

Fourth, there were instances where cross-border consultations excluded or omitted neighbouring coastal communities, users and residents. Within the framework of the Aarhus and Espoo Conventions, and the HELCOM-VASAB guidelines, there is the potential for exclusion during such consultations as who should be informed and invited is voluntary and left to the full discretion of the MSP competent authorities. Findings from both cases highlighted those discussions regarding border delimitation are mainly conducted through diplomatic channels, typically occurring between the Ministries of Foreign Affairs and falls out of the MSP competences. It was noted in both cases that coastal communities and users have challenges in directly engaging in cross-border consultations especially when it is led by a neighbouring country planning authority. In the Pomeranian Bay, the container terminal expansion in Poland and its impact on tourism in Usedom (Germany) is an example. The residents in Usedom despite their concerns could not have direct engagement and consultation with Polish planning authorities. In Carlingford Lough, the construction of the CO2 terminal along Omeath’s lower shore raised concerns by residents. Interviewees noted that they were not consulted during the landscape and noise assessment, because they live in a different jurisdiction, although the CO2 storage tanks are less than hundred metres from their homes. Officials in Louth County Council confirmed that they did not receive any transboundary notification and consultation for the CO2 gas facility. Issues of lack of transparency, limited dialogue with stakeholders and plans being developed behind closed doors were highlighted during the interviews with stakeholders.

Fifth, existing cross-border institutional mechanisms are not sufficient to address contested borders and ownership. In the Pomeranian Bay, although there is engagement between Poland and Germany through HELCOM-VASAB and the GPSPC, this has not directly contributed to addressing the border issues and having formal agreement on MSP outcomes. For example, Poland still made a spatial designation for the contested area based on political direction, although, at a planning level there was an informal agreement with Germany to have no designation. This is mainly due to tension between national drivers in Poland and Germany, as well as specific local drivers in Germany. Szczecin and Świnoujście are key metropolitan areas in Poland and drivers for national development. In comparison, the eastern Baltic Sea coast in Germany is a peripheral region with high nature conservation values and fewer competing uses for the EEZ plan to contend with; local economies are largely driven by tourism. This finding resonates with the argument by Schultz-Zehden and Gee (Citation2016) that there is a gap between informal transboundary MSP dialogue and tangible influence on formal national MSP processes. In contrast, it can be argued that the Polish plan takes a proactive approach in presenting the type of use and interests that the government envisions for the contested area. However, this can be regarded as a political decision that might cause some tension on both sides of the border. Alternatively, on the IOI both plans take a less proactive approach leaving the contested areas as fuzzy boundaries and less consideration in the plans (). Subsequently, existing cross-border mechanisms through the LA have not provided any formal planning approaches to address issues such as unlicensed oyster farming.

Turning to the ‘Wheel of Integration and Adaptation’ offers insights to assess the level of cross-border integration for both cases. On the IOI, institutions and actors may be regarded as being at the first stage of cross-border integration: observation (). This stage is characterized by the consideration of approaches and mechanisms for adopting the MSP Directive and the Marine and Coastal Access Act 2009 into national legislative frameworks such as the Marine Act (NI) 2013 and the Marine Area Planning Act (2021) (ROI). However, cross-border MSP appears to sit at the bottom of the Government's priority list, amidst Brexit, the lack of NI Executive and recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. Findings from the interviews indicate that IOI actors are starting to move towards stage 2 (initial impact). Stage 2 is characterized by initial preparation to have a cross-border mechanism for discussing MSP issues although this is marred by limited knowledge exchange and paused cross-border actions due to political issues such as Brexit.

Figure 5. Stages of cross-border MSP integration in the Island of Ireland and Pomeranian Bay.

Source: Adapted from Ansong et al. (Citation2021).

In comparison, institutions in Germany and Poland have had a long-standing transboundary collaboration on MSP, meaning they straddle the recovery and stabilization stage (). The stabilization stage in the Pomeranian Bay has been characterized by increased knowledge sharing, stakeholder networking, specialized expertise and development of specific transboundary MSP guidelines. The HELCOM-VASAB MSP Working Group and the introduction of the Guidelines on Transboundary MSP Consultation are examples of this stage (HELCOM-VASAB Citation2016). Formal and active cross-border consultation between Germany and Poland on MSP is quite recent and mostly tied to the development of the plans. There has been long-standing cooperation through various MSP projects and years of understanding to address structural constraints. Although the HELCOM-VASAB framework and related projects have been used to promote sea-basin-wide thinking, high-level political concerns and bilateral ambitions have not been a major theme or issue for discussion since it falls out of the remit of planners. These issues are mostly taken as a given based on decisions by the Foreign Ministries. At a cross-border level, although there is goodwill between MSP officials and planners to resolve the contested issues and tensions, this has not moved on to resolution between high-level government officials. The ‘Wheel of Integration and Adaptation’ indicates practices that these countries must demonstrate to achieve an integrated cross-border MSP. The following section considers various pathways for action towards addressing these complex issues.

5. Finding a way forward: pathways towards integrated cross-border MSP

The challenges of cross-border MSP call for a more comprehensive planning approach. The following are presented as pathways for advancing cross-border MSP.

5.1. Restructuring existing cross-border marine governance architecture

The findings indicate the need to restructure existing nation-state governance frameworks for greater cross-border institutional alignment. The development of shared visions and political direction is needed. Although this exists in the Baltic Sea, shared visions and political direction are needed for the Pomeranian Bay. A formal agreement on the use of these areas through local plans, either strategic or regulatory, will be beneficial. A nested approach and planning hierarchy could foster the development of local plans that will consider cross-border specific issues as compared to national plans which might be more strategic. In the Pomeranian Bay, issue-specific cross-border working groups in addition to existing state-level institutions are proposed as critical in advancing cross-border integration (Hassler et al. Citation2018). Planning for increasing shipping activities, subsea pipeline infrastructure and nature conservation is critical to manage related conflicts. This can be addressed by the preparation of joint strategic projects such as the Baltic Pipe (Poland and Denmark)Footnote11 to align the strategic interests of respective countries.

On the IOI, plans could recognize and design MSP policies informed by site-specific challenges, preferences, competencies and of different actors. Future regional and local marine plans must take account of the activities in contested waters, such as the proliferation of unregulated oyster trestles in Lough Foyle. Local plans could consider recreation, local well-being, tourism, restoration and nature-based solutions. There is potential for the respective governments to consider the establishment of cross-border ‘marine peace parks’ as a means for reconciliation and resolving conflicts between users (Mackelworth Citation2012). However, the vision for a local marine spatial plan and/or cross-border marine peace park should be clear on its contribution to reconciliation, resolving conflicts and enhancing co-existence between uses. These priorities should be supported by joint agreements, as well as budgets from local councils, provinces and sponsoring departments to address entrenched political divides.

5.2. Enhancing community action and capacity for blue justice

Both case studies highlighted the need to empower coastal communities through stronger social and blue justice, greater transparency and equity in planning decision making (Bennett et al. Citation2021). Currently, the consideration of social sustainabilityFootnote12 is limited in MSP as planners rarely assess that as a routine or compulsory procedure of MSP (Saunders et al. Citation2020). Prescriptive legal principles for direct stakeholder involvement in cross-border MSP and infrastructure projects are needed. This should have specific requirements for the neighbouring country to host mandatory community consultation events, rather than a voluntary approach which is decided by the MSP contact person. This will reduce the high level and diplomatic nature of transboundary consultation where residents and coastal interests cannot directly engage with neighbouring planning authorities, even where proposed projects may have social and economic impacts. Such cross-border consultation should ensure representation by marginalized and vulnerable groups who also derive their well-being from the management of shared resources. This may require proactively engaging them to reveal their stakes indirectly (Piwowarczyk et al. Citation2021). The role of ocean science diplomacy and better evidence is also critical here as countries with better evidence can easily dominate cross-border consultation.

Ocean knowledge management should be part of the MSP process and made accessible to various groups of stakeholders including vulnerable and community groups to support effective consultation (Saunders et al. Citation2017). It is advisable for MSP authorities to develop comprehensive non-technical documents and infographics on MSP and plans to make content more understandable for different audiences. This is especially needed in the case of technical plans such as in Germany and Poland.

The establishment of coastal partnerships, including Solway Firth and Severn Estuary Partnership in Great Britain, are good examples of encouraging community and user representation in cross-border MSP. These partnerships are important in garnering greater understanding and evidence of marine activities, contributing to policy developments. They serve as platforms to engage with local political appointees and communicate their issues to higher political levels. The establishment of such coastal partnerships should be backed with direct funding from MSP authorities to ensure their sustainability. For the Pomeranian Bay, a bilateral MSP platform/conferences for all stakeholders and an MSP blog in Polish and German led by eNGOs in collaboration with the GPSPC will be advisable to discuss MSP challenges.

Interviewees on IOI called for equal rights of appeal to give communities the same rights as applicants, which is the case in ROI through the third-party rights of appeal mechanism. Current planning legislation in the UK, provides developers the right to appeal against the refusal of planning permission and marine licences, but members of the public and communities have no right to appeal against the granting of permission. Their only recourse is via Judicial Review: an expensive and time-consuming process, and which is dependent on finding a procedural irregularity with the planning process. This is even more complicated for transboundary projects with different project application filing system involved for the public to appeal a decision. Alternatives to ensuring more equal rights in MSP could be through internal review and decisions by a tribunal or regional sea organization such as OSPAR or HELCOM-VASAB.

5.3. Facilitating collaborative learning

Collaborative learning through transboundary MSP projects must transition from individuals and projects leads to cross-border authorities delivering sector plans. This will involve better training of decision makers, marine officers and in higher education institutions on the benefits of MSP, environmental law, and marine conservation issues as exemplified through the SEAPLANSPACE project.Footnote13 Such training could create awareness of the complexity of issues that need to be overcome to generate greater involvement in decision-making (Ansong et al., Citation2021; O'Higgins et al. Citation2019). There needs to be the cultivation of shared knowledge, exchange of data and information in both formal and informal environments. The HELCOM-VASAB MSP framework is a prime example. It allows ministers and government representatives to discuss transboundary MSP issues and develop regional positions and guidelines. The LA has a long-standing cross-border remit for fisheries. This covers the whole catchment of the Loughs that can be built on by advancing the legislative remits for the LA regarding aquaculture licensing. A central repository of information with environmental data, survey information, contact details of interested parties, relevant stakeholders, resident groups, non-statutory stakeholders to contact would be useful. Moreover, it would be beneficial if MSP map viewers could work together and have an option to integrate (switch on/off) the layers of the other neighbouring marine plans especially on the IOI.

5.4. Sustaining cross-border engagement after plan adoption

One of the key barriers to coherent cross-border solution is temporal fragmentation and mismatch in MSP as plans of neighbouring countries are rarely executed in parallel. For instance, the Polish plan was prepared prior to the revision of the German EEZ plans which resulted in limited extensive cross-border discussions. Similarly, the NMPF was adopted in 2021, whilst the dMPNI is yet to be adopted. This makes alignment of stakeholder engagement, data collection and discussion about planning solutions even more difficult due to differences in priorities at different times. To cope with this challenge, a structured online repository of comments and suggestions, or a ‘consultation hub’ could be run by each MSP authority and made available in national languages of neighbouring countries. Such a repository would help in sustaining interest, aid plan implementation and review by better inclusion of stakeholders concerns across governance levels from neighbouring countries.

5.5. Fostering innovative interventions and leadership

Proactive leadership beyond the current firefighting approach from Governments to address contested border and ownership issues and consider priority uses/conflicts is needed. Many States across the world have embarked on innovative approaches to addressing maritime jurisdictional issues. One approach to delimit the contested area on IOI could be the establishment of an official ‘closing line agreement’ in accordance with UNCLOS. This will indicate that the contested area and catchment are internal waters, allowing both States to use the area without infringing on the right of passage of the other country (Symmons Citation2009).

The implementation of joint cross-sectoral MOU, management agreements and plans (strategic or regulatory) between neighbouring countries can be explored without necessarily delimiting the maritime border. A more subtle approach would be to ensure that there is political direction and agreement on how these areas will be planned and managed, as well as which bodies will lead in enforcing and implementing such actions. The use of a management agreement is currently being explored in the Lough Foyle case. However, this has been stymied by political wrangling and failure to agree on the ownership of the seabed in Lough Foyle. A Joint Development Zone approach which was used in Nigeria and Sao Tome and Principe, or Timor Sea Treaty between Australia and East Timor can be explored (Tanga Citation2010). Such an approach can consider accepting the contested area as a joint area for development and/or giving specific rights and measures to a particular country. Moreover, the UNCLOS and related stipulations about maritime delimitation need to consider the complexity of cross-border marine areas and fluidity of marine ecosystems to promote shared management (Ansong, Gissi, and Calado Citation2017).

Continuity of national and cross-border level planning staff is essential in advancing personal relations. As noted in the Pomeranian Bay, the longevity of staff in Germany and Poland has been successful in settling potential conflicts based on trust that has been built over time.

6. Conclusion

This paper aimed to compare two MSP systems for the Island of Ireland and the Pomeranian Bay to understand the contemporary challenges of planning cross-border areas and dealing with contested borders. Results show that the delivery of cross-border MSP especially in contested areas remains ‘a planner's dream’ as strong political leadership is needed to resolve jurisdictional ownership issues and related MSP conflicts. Beyond this complex challenge, this study identified five key findings: (i) most contested borders are geographical peripheries and are distant from decision makers who act on respective maritime conflicts, (ii) geopolitical legacy and history affect transparency and introduces tension between stakeholders, (iii) there are cases where citizens are excluded from direct consultations with neighbouring planning processes, (iv) planning culture prevalent in each country can influence the effectiveness of identifying cross-border issues, (v) differences in the good will of planners or informal cross-border discussions and actual impact on formal national MSP processes. This paper has set out the perspectives of key stakeholders and presents potential intervention pathways as a first step in advancing discussions about the implementation of cross-border MSP in contested marine waters.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express sincere gratitude to all the interview participants for their responses.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Cross-border MSP refers to engagement on MSP issues between two or more entities (e.g neighbouring countries) that share a common political border which is either agreed or contested (Ansong, Ritchie, and McElduff Citation2022).

2 HELCOM-VASAB is an intergovernmental group for Baltic Sea established to cooperate on environmental policy and spatial planning issues.

3 Colonialism refers to the territorial, juridical, cultural, linguistic, political, mental/epistemic and/or economic domination of one group of people or groups of people by another (external) group of people.

4 Ireland retained a constitutional claim to all waters around the island until the Good Friday Agreement in 1998. In the associated referendum, Articles 2 and 3 of the Irish Constitution estopped the claim to the territorial waters around NI. Both UK and Irish governments continue to claim full jurisdiction of the loughs whilst acknowledging their respective positions are disputed by the other party.

5 The NMPF allows the development of regional and sectoral plans known as Designated Marine Area Plans (DMAPs) for a range of sectors e.g., offshore renewable energy.

6 The LA is a cross-border institution established under the Good Friday Agreement to address fisheries management in the cross-border Loughs.

7 The name Pomerania comes from Slavic language ‘po more’, which means ‘land by the sea’.

8 The gas pipelines connect Russia directly to Germany under the Baltic Sea and bypasses Poland. However, the Nord Stream 2 is at a complete standstill and pending a final operating permit due to the escalation of the Ukraine conflict and potential sanctions against Russia.

9 A national and centralised state maritime spatial plan in Poland and two plans including Länder and Federal in Germany.

10 According to Article 12 of the UNCLOS roadstead situated wholly or partly outside the outer limit of the territorial sea, are included in the territorial sea.

12 The consideration of culture, identity, gender, status, lifestyles, wellbeing, effective participation and equitable distribution of access, risks, benefits and capacities.

References

- Ansong, J., H. Calado, and P. Gilliland. 2021b. “A Multifaceted Approach to Building Capacity for Marine/Maritime Spatial Planning Based on European Experience.” Marine Policy 132, 103422. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2019.01.011.

- Ansong, J., E. Gissi, and H. Calado. 2017. “An Approach to Ecosystem-Based Management in Maritime Spatial Planning Process.” Ocean & Coastal Management 141: 65–81. doi:10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2017.03.005.

- Ansong, J., L. McElduff, and H. Ritchie. 2021a. “Institutional Integration in Transboundary Marine Spatial Planning: A Theory-Based Evaluative Framework for Practice.” Ocean & Coastal Management 202, 105430. doi:10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2020.105430.

- Ansong, J., H. Ritchie, and L. McElduff. 2022. “Institutional Barriers to Integrated Marine Spatial Planning on the Island of Ireland.” Marine Policy 141, 105082. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2022.105082.

- Armitage, D., A. Charles, and F. Berkes. 2017. Governing the Coastal Commons: Communities, Resilience and Transformation. London: Routledge.

- Bennett, N., J. Blythe, C. White, and C. Campero. 2021. “Blue Growth and Blue Justice: Ten Risks and Solutions for the Ocean Economy.” Marine Policy 125: 104387. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104387.

- Carneiro, G., H. Thomas, S. Olsen, D. Benzaken, S. Fletcher, and Mendez-Roldan. 2017. Cross-Border Cooperation in Maritime Spatial Planning. European Commission Report.

- Chalastani, V., V. Tsoukala, H. Coccossis, and C. Duarte. 2021. “A Bibliometric Assessment of Progress in Marine Spatial Planning.” Marine Policy 127: 104329. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104329.

- Cons, J., and R. Sanyal. 2013. “Geographies at the Margins: Borders in South Asia–an Introduction.” Political Geography 35: 5–13. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2013.06.001.

- DHLGH. 2021. National Marine Planning Framework: Government of Ireland.

- Diggon, S., C. Butler, A. Heidt, J. Bones, R. Jones, and C. Outhet. 2021. “The Marine Plan Partnership: Indigenous Community-Based Marine Spatial Planning.” Marine Policy, 132: 103510.

- Ehler, C., J. Zaucha, and K. Gee. 2019. “Maritime/Marine Spatial Planning at the Interface of Research and Practice.” In Maritime Spatial Planning, edited by J. Zaucha, and K. Gee, 1–21. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-98696-8_1.

- Emerging Europe. 2021. A Polish ‘mega Port’ Project is Worrying German Environmentalists. Accessed 07 December 2021. https://emerging-europe.com/news/a-polish-megaport-project-is-worrying-german-environmentalists/.

- Epstein, G., J. Pittman, S. Alexander, S. Berdej, T. Dyck, and U. Kreitmair. 2015. “Institutional Fit and the Sustainability of Social-Ecological Systems.” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 14: 34–40. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2015.03.005.

- Eurostat. 2020. Real GDP Per Capita. Accessed 07 December 2021. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/sdg_08_10/default/table?lang=en.

- Fairbanks, L., L. Campbell, N. Boucquey, and K. St. Martin. 2018. “Assembling Enclosure: Reading Marine Spatial Planning for Alternatives.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 108 (1): 144–161. doi:10.1080/24694452.2017.1345611.

- Faludi, A. 2013. “Territorial Cohesion, Territorialism, Territoriality, and Soft Planning: A Critical Review.” Environment & Planning A: Economy and Space 45: 1302–1317. doi:10.1068/a45299.

- Faludi, A. 2019. “New Horizons: Beyond Territorialism.” Europa XXI 36: 35–44. doi:10.7163/Eu21.2019.36.3.

- Flannery, W., A. O'Hagan, C. O'Mahony, H. Ritchie, and S. Twomey. 2015. “Evaluating Conditions for Transboundary Marine Spatial Planning: Challenges and Opportunities on the Island of Ireland.” Marine Policy 51: 86–95. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2014.07.021.

- Giacometti, A., J. Moodie, M. Kull, and A. Morf. 2017. Coherent Cross-Border Maritime Spatial Planning for the Southwest Baltic Sea – Results from Baltic SCOPE.

- Gottfredson, R., and C. Reina. 2020. “Exploring Why Leaders Do What They Do: An Integrative Review of the Situation-Trait Approach and Situation-Encoding Schemas.” The Leadership Quarterly 31 (1): 101373. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2019.101373.

- Guo, R. 2018. Cross-Border Resource Management. San Diego: Elsevier.

- Hassler, B., K. Gee, M. Gilek, A. Luttmann, A. Morf, F. Saunders, I. Stalmokaite, H. Strand, and J. Zaucha. 2018. “Collective Action and Agency in Baltic Sea Marine Spatial Planning: Transnational Policy Coordination in the Promotion of Regional Coherence.” Marine Policy 92: 138–147. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2018.03.002.

- HELCOM-VASAB. 2016. Guidelines on Transboundary Consultations, Public Participation and Co-operation.

- HELCOM/VASAB. 2022. Voluntary Guidance for Assessment of Cross-border Coherence in Maritime Spatial Planning. HELCOM-VASAB MSP WG 23-2021.

- Jackowska, N. 2008. “The Border Controversy Between the Polish People’s Republic and the German Democratic Republic in the Pomeranian Bay.” Przegląd Zachodni 3: 145–159.

- Jay, S., F. Alves, C. O'Mahony, M. Gomez, A. Rooney, M. Almodovar, et al. 2016. “Transboundary Dimensions of Marine Spatial Planning: Fostering Inter-Jurisdictional Relations and Governance.” Marine Policy 65: 85–96. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2015.12.025.

- Jay, S., T. Klenke, F. Ahlhorn, and H. Ritchie. 2012. “Early European Experience in Marine Spatial Planning: Planning the German Exclusive Economic Zone.” European Planning Studies 20 (12): 2013–2031. doi:10.1080/09654313.2012.722915.

- Jentoft, S., and R. Chuenpagdee. 2009. “Fisheries and Coastal Governance as a Wicked Problem.” Marine Policy 33 (4): 553–560.

- Keijser, X., H. Toonen, and J. van Tatenhove. 2020. ““Learning Paradox” in Maritime Spatial Planning.” Maritime Studies 19: 333–346. doi:10.1007/s40152-020-00169-z.

- Kelly, C., G. Ellis, and W. Flannery. 2018. “Conceptualising Change in Marine Governance: Learning from Transition Management.” Marine Policy 95: 24–35. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2018.06.023.

- Kuempel, C., K. Jones, J. Watson, and H. Possingham. 2019. “Quantifying Biases in Marine-Protected-Area Placement Relative to Abatable Threats.” Conservation Biology 33: 1350–1359. doi:10.1111/cobi.13340.

- Mackelworth, P. 2012. “Peace Parks and Transboundary Initiatives: Implications for Marine Conservation and Spatial Planning.” Conservation Letters 5 (2): 90–98. doi:10.1111/j.1755-263X.2012.00223.x.

- McAteer, B., L. Fullbrook, W. Liu, J. Reed, N. Rivers, N. Vaidianu, A. Westholm, et al. 2022. “Marine Spatial Planning in Regional Ocean Areas: Trends and Lessons Learned.” Ocean Yearbook Online 36 (1): 346–380. doi:10.1163/22116001-03601013.

- Morf, A., J. Moodie, E. Cedergren, S. Eliasen, K. Gee, M. Kull, S. Mahadeo, S. Husa, and M. Vološina. 2022. “Challenges and Enablers to Integrate Land-Sea-Interactions in Cross-Border Marine and Coastal Planning: Experiences from the Pan Baltic Scope Collaboration.” Planning Practice & Research 37 (3): 333–354. doi:10.1080/02697459.2022.2074112.

- NISRA. 2017. Northern Ireland Multiple Deprivation Measures 2017.

- O'Higgins, T., L. O'Higgins, A. M. O'Hagan, and J. O. Ansong. 2019. “Challenges and Opportunities for Ecosystem-Based Management and Marine Spatial Planning in the Irish Sea.” In Maritime Spatial Planning, edited by J. Zaucha, and K. Gee, 47–69. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-98696-8_3.

- Østhagen, A. 2019. Lines at Sea: Why Do States Resolve Their Maritime Boundary Disputes?. Doctoral Dissertation, University of British Columbia.

- Peel, D., and M. G. Lloyd. 2004. "The Social Reconstruction of the Marine Environment: Towards Marine Spatial Planning?" Town Planning Review 75 (3): 359–378.

- Peters, K. 2020. “The Territories of Governance: Unpacking the Ontologies and Geophilosophies of Fixed to Flexible Ocean Management, and Beyond.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 375: 20190458. doi:10.1098/rstb.2019.0458.

- Piwowarczyk, J., J. Zaucha, A. Koroza, P. Pakszys, J. Pardus, M. Rakowski, K. Romancewicz, and T. Zieliński. 2021. Integrating Cultural Values in Marine Spatial Planning and the Blue Growth. Case study. Gulf of Gdańsk, Poland.

- Polejack, A. 2021. “The Importance of Ocean Science Diplomacy for Ocean Affairs, Global Sustainability, and the UN Decade of Ocean Science.” Frontiers in Marine Science 8: 248. doi:10.3389/fmars.2021.664066.

- Polish Maritime Administration. 2021. Maritime Spatial Plan for Polish Sea Areas in Scale of 1:200 000.

- Rauhut, D., F. Sielker, and A. Humer. 2021. EU Cohesion Policy and Spatial Governance. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Ritchie, H., J. Ansong, and W. Flannery. 2022. “Marine Spatial Planning for Northern Ireland: From Fragmentation Towards Integration.” In 2nd Edition Planning Law and Practice in Northern Ireland, edited by S. McKay and M. Murra, 307–325. London: Routledge.

- Ritchie, H., and G. Ellis. 2010. “‘A System That Works for the Sea'? Exploring Stakeholder Engagement in Marine Spatial Planning.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 53 (6): 701–723. doi:10.1080/09640568.2010.488100.

- Ritchie, H., and L. McElduff. 2020. “The Whence and Whither of Marine Spatial Planning: Revisiting the Social Reconstruction of the Marine Environment in the UK.” Maritime Studies 19 (3): 229–240. doi:10.1007/s40152-020-00170-6.

- Sander, G. 2018. “Ecosystem-based Management in Canada and Norway: The Importance of Political Leadership and Effective Decision-Making for Implementation.” Ocean and Coastal Management 163: 485–497. doi:10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2018.08.005.

- Saunders, F., M. Gilek, K. Gee, K. Dahl, B. Hassler, A. Luttmann, A. Morf, et al. 2017. BONUS BALTSPACE Deliverable D2.4: Msp as a Governance Approach? Knowledge Integration Challenges in MSP in the Baltic Sea. Stockholm: BONUS BALTSPACE project. Accessed 6 December 2022. https://www.baltspace.eu/files/BONUS_BALTSPACE_D2-4.pdf

- Saunders, F., M. Gilek, A. Ikauniece, R. V. Tafon, K. Gee, and J. Zaucha. 2020. “Theorizing Social Sustainability and Justice in Marine Spatial Planning: Democracy, Diversity, and Equity.” Sustainability 12 (6): 2560. doi:10.3390/su12062560.

- Schultz-Zehden, A., and K. Gee. 2016. “Towards a Multi-Level Governance Framework for MSP in the Baltic.” Bmi 31 (1): 34–44.

- Spijkerboer, R. 2021. “The Institutional Dimension of Integration in Marine Spatial Planning: The Case of the Dutch North Sea Dialogues and Agreement.” Frontiers in Marine Science 8: 1078. doi:10.3389/fmars.2021.712982.

- Symmons, C. 2009. “The Maritime Border Areas of Ireland, North and South: An Assessment of Present Jurisdictional Ambiguities and International Precedents Relating to Delimitation of Border Bays.” International Journal of Marine and Coastal Law 24: 457–500. doi:10.1163/157180809X455584.

- Tafon, R., D. Howarth, and S. Griggs. 2019. “The Politics of Estonia’s Offshore Wind Energy Programme: Discourse, Power, and Marine Spatial Planning.” Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 37 (1): 157–176. doi:10.1177/2399654418778037.

- Tanga, B. 2010. The Joint Development Zone Between Nigeria and Sao Tome and Principe: A Case of Provisional Arrangement in the Gulf of Guinea. New York: United Nations.

- Twomey, S. 2020. Seeking Pathways Towards Improved Transboundary Environmental Governance in Contested Marine Ecosystems. Doctor of Philosophy, University College Cork.

- van Tatenhove, J. 2017. "Transboundary Marine Spatial Planning: A Reflexive Marine Governance Experiment?" Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning 19 (6): 783–794.

- UN. 2021. The Second World Ocean Assessment II. New York: United Nations. ISBN: 978-92-1-1-130422-0.

- Wang, S., C. Liu, Y. Hou, and X. Xue. 2022. “Incentive Policies for Transboundary Marine Spatial Planning: An Evolutionary Game Theory-Based Analysis.” Journal of Environmental Management 312: 114905. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.114905.

- Wilson, T., and H. Donnan. 2012. Borders and Border Studies. A Companion to Border Studies. Chicester: John Wiley & Sons, 1–25.