ABSTRACT

This paper explores and interrogates existing approaches to urban-rural digital divide reduction. The EU and its member states are applying fragmented and diverse digitalization of territories. Any systematic review of best practice and the juxtaposition of urban and rural areas is lacking. The authors present a taxonomy of key European rural digitalization approaches and determined EU country clusters according to the extent of their use, with a critical analysis of the context of their successes or failures. The key finding is identification of digital infrastructure and virtual sphere coherence as a challenge for bridging the urban-rural digital divide.

1. Introduction

EU strategy documents contain a number of normative proclamations regarding the promotion of rural digitalization (see OECD Citation2018; EC Citation2021a, Citation2021b), but in practice there is no clear idea of how to concretely apply these visions through different approaches. In addition, the literature points out that EU strategies generalize and simplify, thereby neglecting specific local needs (see Salemink, Strijker, and Bosworth Citation2017; Roberts et al. Citation2017a; Dubois and Sielker Citation2022). The digitalization of rural areas is thus taking place in fragmented directions. This problem is also confirmed by the European Commission (EC Citation2021a), which published its Rural Vision 2040, stating that it wants to create a common platform in order to share best practices. Although digitalization currently includes very important spatial processes, that will fundamentally affect rural resilience in the twenty-first century, there is no systematic review and taxonomy of best practice in bridging the urban-rural digital divide.

While the academic literature reflects upon the causes and consequences of the urban-rural digital divide (McFarland Citation2018; Onitsuka, Hidayat, and Huang Citation2018), barriers to rural digitalization (Wilson et al. Citation2018; Michels et al. Citation2020), rural vulnerability and resilience due to low digitalization and a lack of broadband connection (Ashmore, Farrington, and Skerratt Citation2017; Roberts et al. Citation2017a; Giannakis and Bruggeman Citation2020), and digital innovations in agriculture (Trendov, Varas, and Zeng Citation2019; Rotz et al. Citation2019a), it often does not offer a practical solution. There are several authors (Briglauer et al. Citation2019; Dyba et al. Citation2020; Rundel, Salemink, and Strijker Citation2020) who aim to describe the solutions to the urban-rural digital divide, but only with a focus on isolated examples, while systematic insight into how to address this issue is still lacking. The shortcoming of existing approaches is that they do not offer a practical solution to the digital divide and focus mainly on the causes and factors influencing the emergence of the digital divide in thematically closed studies.

The motivation of this paper is to synthesize and organize isolated cases of solutions to the digital divide applied in EU countries and to reflect these experiences in the existing academic discourse with the possibility of applying them in policy making. Therefore, the aim of this paper is to explore and interrogate existing approaches of reducing the urban-rural digital divide and creation of taxonomy of best practice examples. Based on the aforementioned research gap and the aim of this paper, the present authors define 2 research questions: What are the approaches of best practise used to bridge the urban-rural digital divide? What are the differences in the activity of EU members in developing the rural digitalization best practice? Created taxonomy of best practice examples, will allow to expose the activity of countries in this area. The importance of taxonomy is also in the systematization of fragmented approaches and digitalization models that are used in practice. The created taxonomy can significantly help scholars to systematically understand, empirically and analytically process the topic and for theory generation and development (see e.g. Keshet Citation2011; Rijswijk et al. Citation2021). Policy practitioners (such as national and regional policy makers, mayors and other local stakeholders) can be inspired and implement new concrete practices in reducing the digital divide between urban and rural areas, because at the moment there is not enough systematically sorted information, inspiration, or knowledge to meet the proclaimed EU objectives. In order to create a generally acceptable taxonomy of best practice examples, addressing the urban-rural digital divide, and given the fragmented nature of these approaches, this paper, through web content analysis, maps examples of the best practice implemented by the EU member states under different EU funds, programmes, sub-programmes and relevant platforms.

The paper is divided into the following sections. The introduction is followed by a literature review, that identifies the theoretical departures and the context of the digital territorial dynamics, and discusses normative proclamations of best practice in bridging the urban-rural digital divide. The third section describes the methodology. The fourth section focuses on presenting the results, according to the taxonomy of best practice, and distinguishes the digital activity of individual EU countries. The fifth section presents the discussion and concluding remarks, in the context of broader aspects of strategic planning and policy making. The conclusion considers not only a discussion of research questions and the aim of this paper, but also broader lessons for rural policy making in the period of 2021–2027.

2. Theoretical background

2.1. Theoretical departures

This paper focuses on bridging the urban-rural digital divide that aims to achieve rural digital resilience. However, it is not possible to identify a consensus in the academic literature on the urban-rural digital divide definition. Rotz et al. (Citation2019b) define the digital divide as unequal geographic access to information and communication technologies (ICT). Vassilakopoulou and Hustad (Citation2021) refer to the digital divide as encompassing all types of inequality, and they perceive it as a gap between those who can effectively use new information and communication tools, and those who cannot. Similarly, Esteban-Navarro et al. (Citation2020) understand the digital divide as the difference between individuals, companies, regions and countries in the access and use of ICT. According to Lembani et al. (Citation2020), the digital divide is given by the differences in access to and use of ICT, influenced by motivation, ownership, digital skills and usage patterns. This is in accordance with the work of Kos-Łabędowicz (Citation2017), which states that the digital divide is usually defined on two levels: material (physical access to a computer and the Internet) and immaterial (knowledge, motivations and needs fulfilled by the access). In the context of these definitions, factors influencing the digital divide can be identified. A relatively complicated approach in the categorization of factors was used by Furuholt and Kristiansen (Citation2007), who distinguish between infrastructural, socioeconomic, demographic and cultural categories. Philip et al. (Citation2017) simplify this but only in terms of socio-economic digital divides and digital infrastructure divides. Pelucha and Kasabov (Citation2020) understand digital divides in three areas – availability of digital infrastructure, availability and usage of digital services, and digital skills.

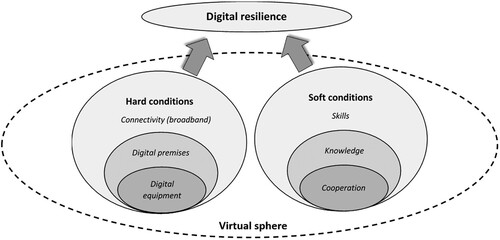

The territorial dimension of the digital divide was identified by Williams et al. (Citation2016), who emphasize digital exclusion in remote rural areas. Digital vulnerability of rural areas in the context of social, economic and cultural disadvantages has been confirmed by Roberts et al. (Citation2017b) and Michels et al. (Citation2020). In general, rural areas are facing problems with broadband coverage (Philip et al. Citation2017; Wilson et al. Citation2018; Bowen and Morris Citation2019; Lai and Widmar Citation2021). Also, attention should be paid to digital skills and knowledge (Erdiaw-Kwasie and Alam Citation2016; Kourilova Citation2019). Thus, the digital divide lies in the differential access of different groups in society to digital technologies (Townsend et al. Citation2013; Morgan et al. Citation2014), with education playing a significant role (Ashmore, Farrington, and Skerratt Citation2017; Young Citation2019). The multi-layered concept (Park Citation2017), in the sense of mutual conditionality of factors, is absolutely essential for achieving the positive benefits of digitalization. Progressive approaches and examples of best practice bridging the urban-rural digital divide are based on quality ICT infrastructure, and require creative sophisticated solutions and forms of cooperation at the local and micro-regional levels. In this context, it is possible to observe the default conditions for digital development, i.e. the quality and availability of ICT infrastructure (hard conditions) and digital skills (soft conditions). These default conditions represent the baseline of the urban-rural digital divide.

2.2. Dynamics of urban-rural digital divide research

Early studies on the digital divide were mostly focused on the dichotomy between people who use and people who do not use the Internet. This simple view of the digital divide has opened a space for academic and political debate. Influencing factors such as age, gender, income, level of education, or residency began to be investigated, but the increasing penetration of the Internet in developed countries helped to start the decline of these types of studies. This was followed by criticism that the earlier view of the digital divide in research was too simplistic, and that the concept was theoretically underdeveloped; hence, the concept of the digital divide began to be redefined (Selwyn Citation2004; Barzilai-Nahon Citation2006; Van Dijk Citation2006). Therefore, more complex, and sophisticated concepts of the digital divide have emerged which provide a broader perspective than the earlier research (Onitsuka, Hidayat, and Huang Citation2018).

Nevertheless, Salemink, Strijker, and Bosworth (Citation2017), who conducted a systematic review of 157 papers on rural digital development in developed countries and identified two main research themes, namely, connectivity and inclusion, argue that the scholarly debate is still highly fragmented. This indicates that approaches to bridging the rural-urban digital divide are very superficial, focusing on isolated cases, and that the comprehensive overview and evaluation of approaches is still lacking. Moreover, the conclusions of studies on these themes are not very positive, as they conclude that differences in the quality of data infrastructure between urban and rural areas persist and even grow. This is also highlighted by Rural Vision 2040 (EC Citation2021a), which states that while rural digitalization is ongoing, the gap between urban and rural areas is still widening, cities are more dynamic in terms of infrastructure quality, and wired connectivity is developing relatively fast, while rural areas are still mostly connected via wireless Internet services.

2.3. Normative proclamations and actual implementation of best practice in bridging the urban-rural digital divide

EU and national strategic documents present a myriad of normative proclamations. In the new EU Rural Vision 2040 (EC Citation2021a), the European Commission stresses that remote rural areas face a number of challenges, including a still significant urban-rural digital gap. This should be bridged through four complementary areas of action that embody a long-term vision of stronger, connected, resilient and prosperous rural areas by 2040. Similarly, 2030 Digital Compass (EC Citation2021b) states that by 2030: (1) all European homes will be covered by gigabit networks and all populated areas will be covered by 5G networks, (2) all key public services available to European citizens and businesses will be online, (3) all European citizens will have access to health e-documentation and (4) 80% of citizens will use digital identity solutions. However, any specific procedures to meet these objectives are not proposed. These strategic documents are subsequently adopted by individual states at the national level, but in the absence of concrete procedures and examples of how to address the issue at the local level, the set objectives often cannot be met because individual actors simply do not have enough information, inspiration, or knowledge on how to achieve the proclaimed objectives.

The OECD (Citation2018) report seems to be a notable exception, and highlights a set of best approaches and experiences, while stressing that bridging the rural digital divide obviously comes with challenges, especially for policy makers, in ensuring that relevant information is available to advise on the best approaches and technological options. But, Alam et al. (Citation2018, 60) note that even with such specified approaches, implementation itself can be complicated, as EU and national strategy documents and even the academic literature share a ‘techno-optimist approach’, yet regional readiness to adopt new technological challenges is still often lagging (Alam and Shahiduzzaman Citation2014) and in the case of rural regions, the situation is significantly worse because they are internally very heterogeneous. All available resources will, therefore, be needed to bridge the rural digital divide.

From the above literature review, the significance of this research lies in the fact that there is no comprehensive database of rural digitization approaches or projects in the current literature (to the best of our knowledge). This fact is underlined by the need of the European Commission to create such a database, expressed in Rural Vision 2040 (EC Citation2021a). The ways in which current approaches to bridging the digital divide are presented are highly fragmented, as the academic literature generally focuses on single case studies (see e.g. Briglauer et al. Citation2019; Dyba et al. Citation2020; Rundel, Salemink, and Strijker Citation2020). Creation of a more comprehensive view of best practice cases, in the form of a taxonomy, can thus contribute significantly to this cause. The taxonomy can provide an overview of options and inspiration for both policy makers and implementers in rural regions, and enhance adoption of digital solutions.

3. Methodology

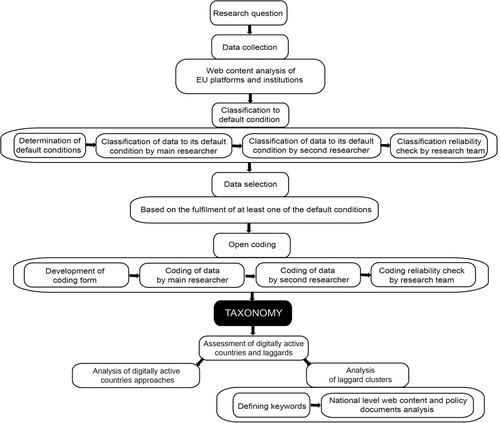

The research methodology was designed to lead to the fulfilment of the aim of this paper and provide answers to the research questions specified in the introduction. The research was executed and finished in June 2021. Projects included in the analysis were executed or started in the period of 2014–2021. All steps of the methodological procedure that is described in this section are visualized in .

The first step in our research was the collection of data (i.e. projects presented by EU institutions as examples of best practice in reducing the digital divide between urban and rural areas). This has been done through web content analysis (Weare and Lin Citation2000; Kim and Kuljis Citation2010) of current and historical information on examples of best practice in the development of rural digitalization. The initial analysis was carried out based on two simple criteria, namely that the projects had to relate to digitalization and rural areas. To create a generally acceptable framework and taxonomy of best practice, it was necessary to explore and map the approaches that have been applied by the EU within individual funds, programmes, sub-programmes and relevant platforms. The analysis was based on studying all relevant content on the platforms listed below, not just keyword searches. In total, 133 projects relating to rural digitization were selected. The web content analysis that was carried out map's projects and examples that are presented mainly within the Horizon 2020 funded projects. This programme represents a notional laboratory for exploring and partly testing the application of different approaches in international cooperation among a large European consortium of different research institutions and application partners. Furthermore, the authors mapped approaches and examples of best practice in rural digitalization that were presented in the following funds, platforms and institutions at the EU level:

− The European Network for Rural Development (ENRD)

− European Innovation Partnership for Agricultural productivity and Sustainability (EIP-AGRI)

− Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development (DG AGRI)

− European Regional Development Fund (ERDF)

− European Economic and Social Committee (EESC)

− European Committee of the Regions (CoR)

− European Commission (EC)

The second step was to categorize the identified examples according to the default hard and soft conditions identified through the literature review. From the identified examples, one more default condition emerged, namely, the virtual sphere, which brings together the field of mobile applications, web portals and other online platforms that are aimed at simplifying and streamlining the lives of people in rural areas. The virtual sphere (shown in ) represents concrete online tools of the digital economy that combine both hard and soft conditions and is, therefore, classified as the third default condition (horizontal/cross-cutting pillar). Finally, 95 individual and multi-stakeholder projects were assessed as meeting the criterion of having, or with the potential to have, an impact on reducing the rural-urban digital divide, i.e. fulfilling at least one of the default conditions. Where non-EU countries were involved in multilateral European projects aimed at reducing the digital divide, these countries were also mentioned in the research. Although all of the identified best practices have been analyzed, not every case is referred to in the text of the analysis, for readability reasons.

Figure 1. Digital resilience in the context of its default conditions. Source: own elaboration, based on conducted research.

The subsequent step was the analysis of the identified dataset of 95 observations through open coding (Corbin and Strauss Citation1990). Observations were grouped into thematic categories, based on common characteristics of analyzed projects that emerged from the dataset which, to varying degrees, fulfil the elements of the default conditions. These categories then formed the basis for the taxonomy of rural digitization approaches (see ). Following this categorization, was then assessed the level of activity of the countries, and digitally active countries and digital laggards were identified (see ). For each category, the representation of countries in each project was mapped (see ). If a country participated in a project through multiple representatives (universities, research labs, municipalities, farms, etc.), only one representation was counted each time. Attention was paid to the digitally active countries (that appear most frequently among the best practice examples), and an analysis of their approach to the issue of reducing the rural-urban digital divide, and a description of specific best practice examples applied, were carried out. An assessment of digital laggards was also made. Territorial clusters of digital laggards were identified (see section 4.4) and subsequently an individual analysis of their approach to the rural-urban digital divide was carried out. Within the thematic categories identified, additional examples of best practice (both at national level and possible further involvement in European projects) were sought, that may not have been identified during the initial analysis of EU-level projects. Mapped were websites and policy documents at national level of:

− Ministries of Agriculture and Regional Development

− Agricultural unions and associations

− Country digitalization offices

− Local Action Groups

Table 1. Taxonomy of the identified rural digitalization best practice. Source: own elaboration, based on conducted research.

Table 2. Participation of European countries in identified best-practice projects (the EU level). Source: own elaboration, based on conducted research.

4. Results – assessment of country representation in the taxonomy of digital best practice

4.1. Taxonomy of identified projects

Due to the common characteristics of each identified best practise, it was possible to divide them into 7 categories (see ). The taxonomy clearly presents a disproportion between the identified examples of best practice, with an overwhelming number of them presenting broadband-focused and other physical infrastructure projects. Soft projects focused on human resource development and on providing access to knowledge, and digital tools are in a clear minority. This indicates that the digital infrastructure in rural areas is still underdeveloped. Hence, logically, without a well-developed digital infrastructure in rural areas, soft skills practices are not feasible.

4.2. Participation of European countries in identified best-practice projects (the EU level)

For each project, the representation of the countries has been mapped and their ranking from best, i.e. as of digitally active countries, to worst, i.e. as of digital laggards, is shown in . These data were then entered into a map for better spatial representation and possible identification of geographical clusters (see ).

4.3. Digitally active countries

Based on the analysis, France, Germany, Finland, Spain, the United Kingdom and the Netherlands appear to be the digitally active countries in reducing the urban-rural digital divide. Among the identified examples of best practice of digitally active countries, the category Accelerators and focus groups has the lowest representation. France, in its rural DIH (Digital Innovation Hub) Pep’it Lab and Fablab, organizes workshops for the public to increase digital literacy (Devillers Citation2019). Finland has launched a programme providing financial support to start-ups in rural areas (Kalliokoski Citation2017). The Netherlands is organizing a Masterclass in Rotterdam: an accelerator programme including lectures and networking activities for rural enterprises working in the food industry (ENRD Citation2017a). Also noteworthy is the Belgian Academy on Tour, which is an all-day bus tour to another country with 24 agri-food entrepreneurs and about ten experts and advisors that has proved to be an innovative way of developing business ideas, and the skills and confidence to implement them (ENRD Citation2017b). There is also Greece's AgriEnt Business Accelerator, a programme for accelerating agripreneurship in Greece, which aims to support promising ideas of innovative applicability of start-up teams (or companies) in agri-food, agri/biotech, agri-tourism and products or services to improve rural life (ENRD Citation2017c).

The second least represented is the category of Smart villages. France, Germany, Finland and Spain are involved in the Smartrural21 project (Smart Rural Areas Citation2021). However, while Spain and Germany have strategic objectives that are focused mainly on digitalization, the Finnish and French Smartrural21 projects aim more generally at agriculture, ecology and self-sufficiency. France, Finland, Germany and the UK still have their individual Smart Village projects, some of which are not EU funded but are presented by the European Commission as best practice digital and smart solutions, that are aimed at preventing rural depopulation (ENRD Citation2018a, Citation2018b; Smart Country Citation2021; Smart Village Scotland Citation2021).

In the Agriculture 4.0 category, the Netherlands appears to be the strongest player with four identified best practices focusing on the use of GPS, remote sensing, soil moisture probes, weather stations, soil scanners, drones, etc. Within the category of Online tools, Spain and Finland dominate with four and three identified best practices, respectively, focusing on online ecosystems for farmers or other rural actors and web portals for information sharing. The category of Broadband is dominated by projects from Finland and Germany, focusing on the deployment of high-speed cable connections to remote mountainous (EC Citation2020a) areas or beyond the Arctic Circle (EC Citation2019). The category of DIH is dominated by identified best practice examples from France and the UK. In Scotland, for example, village halls are being converted into digital hubs (ROBUST Citation2021) and within the project #hellodigital (ENRD Citation2017d) demonstration centres are being established. In France, ‘economic development hubs’ are springing up in rural areas, offering flexible office space ranging from individual ‘closed’ office spaces to conference rooms for training, video conferencing and economic development (ENRD Citation2017e).

What the digitally active countries have in common is the representation in the category of Research Projects. Especially, it is necessary to note international research projects such as DESIRA (Citation2019), CORA (Citation2021), LIVERUR (Citation2018), SMART-AKIS (Citation2021) or ROBUST (Citation2021) in which regional Living Labs are being created.

4.4. Digital laggards

While the group of digitally active countries is relatively clear, the group of countries that can be considered as digital laggards is very diverse. Except for countries with a specific position like Luxembourg, Malta where their small size is an assumption or Switzerland, Norway and Serbia as non-EU members, or Iceland, where almost all of the populations live in the cities, it is possible to classify the other countries into 3 clusters: Trichotomous Baltic States, Central European countries (the so-called Visegrad Four as middle laggards, except Poland) and the Lagging group of Danube countries are, therefore, the subject of the following detailed analysis.

4.4.1. Trichotomous Baltic states in the application of the urban-rural digital divide taxonomy

This section is focused on the Baltic states, which are trichotomous. Estonia is a country that is generally considered to be a digital leader (Kattel and Mergel Citation2019); compared to Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania are lagging in digitalization. However, there are also quite significant differences between these two countries (see ).

Nevertheless, Estonia participates in only four identified projects/examples of fighting the rural-urban digital divide. This is precisely because Estonia is significantly ahead, and a lot of measures are realized by national funds (without the EU support). In Latvia, best practices were recognized in all categories, except accelerators, but the role of accelerators is played by institutions and associations, such as the Ministry of Agriculture, Latvian rural network, LAG network, farmer and municipality associations, smart agrihubs, universities, etc. In Lithuania the situation is different, whereby, at the EU level the best practices were found only in the Broadband category in the context of broadband coverage of rural areas and in the DIH category. Lithuania, as well as Latvia, is involved in the EU ‘Smartagrihubs’ project. Both countries use their own funds to support activities in the field of smart villages, on-line tools, agriculture and research.

Estonia is clearly a leader in digitalization, and not only in the Baltics. However, a comparison between Latvia and Lithuania shows differences between these countries, and Latvia seems to be more active in digitalization than Lithuania. This could be influenced by Latvia having better broadband coverage than Lithuania (EC Citation2020b, Citation2020c).

4.4.2. Context and background of the weak application of digital best practice in the Visegrad four countries (Czechia, Poland, Slovakia, Hungary)

The position of the Visegrad countries within the EU is weaker. Poland is the best performer, followed by the remaining three countries. Given their low participation in the EU best practice, the present authors also focused on additional mapping of other rural digitalization activities taking place at the national level.

In terms of the development of the necessary digital infrastructure, all Visegrad countries have developed relevant strategic documents on digitalization with targets for high-speed internet coverage in their territories. However, full coverage is not expected to be achieved until the 2021–2027 programming period or later.

Poland is involved in five of the identified categories of the EU best practices. It could be influenced by the importance of agricultural and rural issues in the Polish territory (Kamińska Citation2013; Wrzochalska and Chmielevska Citation2017). The remaining categories of On-line tools and Accelerators are interconnected, and their role is played by national networks (rural national networks, associations of municipalities, LAG networks, etc.) in Poland as well as in the other three Visegrad countries. Czech Republic and Hungary are mentioned in four categories, while Slovakia is mentioned in three categories (see ).

In all Visegrad countries, elements of digital agriculture (sensors, drones, etc.) are being introduced but their use is limited, particularly due to financing, a lack of qualifications and generation problems (Somosi and Számfira Citation2020). All four countries are trying to develop and use online tools (farmer's portal, digital maps of farmland, websites with the offer of local products and services, farm management support, etc.). Slovakia, unlike the other three countries, is also involved in the EU project AURORURAL supporting on-line tools (Aurorural Citation2021). All four countries are involved in the European project SmartAgriHubs on digital innovation hubs (EC Citation2021c), but only research and support e-infrastructures (living labs) have been established there. Czechia, Poland and Hungary participate in EU research projects that are aimed at the issue of the urban-rural digital divide, and all Visegrad countries have also their own research facilities and their own research projects. However, the results of the empirical investigation by Pelucha et al. (Citation2021) showed that the emphasis in practice is, generally, on the modernization of agricultural technology and not on the digitalization of agriculture.

4.4.3. Lagging Danube countries – Bulgaria and Romania

Bulgaria and Romania are among the countries that can be described as lagging in terms of digitalization. They suffer from insufficient infrastructure (EC Citation2021d, Citation2021e), which influences other activities. At the EU level, best practices in both countries were found only in two categories. Bulgaria and Romania are involved in the EU project Smartrural21 (Smartrural21 Citation2021a, Citation2021b), but their pilot projects are not primarily aimed at the introduction of smart solutions. Both countries make the effort to inform about possibilities that are related to the issue of smart villages, through various networks (national rural networks, association of municipalities, etc.). In the DIH category, Romania and Bulgaria are involved in the European project ‘SmartAgriHubs’ within the South-East Europe Regional Cluster (SmartAgriHubs, Citationundated), but these DIH are rather livings labs.

In both countries digital agriculture is developing with certain limits. Romanian digital agriculture development is limited by the lack of qualified staff, finance and digitalization costs (Anitei, Veres, and Pisla Citation2021) and there is a large digital divide between big and small farmers (Fertu, Dobrota, and Stanciu Citation2019). Similarly, the role of big farms in digitalization and precise agriculture in Bulgaria is emphasized by Beluhova-Uzunova and Dunchev (Citation2021). Both countries are trying to develop and use online tools provided by, for example, ministries of agriculture, national rural networks, LAG networks, advisory services, SmartAgriHubs and other partners (e.g. universities); hence, they play the role of accelerators. Both countries have their own national research programmes and a network of research institutions, including universities (Popescu et al. Citation2020). In summary, although both countries try to make progress in digitalization, there are significant barriers that are related to both IT infrastructure and what Park (Citation2017) refers to as the second level of the digital divide.

5. Discussion

EU strategic documents present a countless number of normative proclamations concerning the urban-rural digital gap (e.g. EC Citation2021a, Citation2021b). However, no specific procedures to fulfil these proclamations at the local level are proposed. Moreover, the academic debate in this field is fragmented, often superficial, focusing on isolated cases, and the systematic overview or evaluation of approaches is still lacking (Salemink, Strijker, and Bosworth Citation2017). The creation of a more comprehensive view of best practice cases, in the form of taxonomy thus significantly contributes to this issue. The territorial dimension in the sense of different types of rural areas does not need to be distinguished in the taxonomy, as its main purpose is to capture spatial processes and examples of approaches enhancing digitization and virtual connections. According to the academic literature (Philip et al. Citation2017; Pelucha and Kasabov Citation2020), digital resilience is generally based on hard and soft conditions. Nevertheless, the analysis confirmed the importance of the virtual sphere, which represents the conceptual tools of the digital economy. Within EU countries, there are significant differences in readiness in all assessed default conditions.

The group of Western European countries that emerged as digitally active is relatively clear and homogeneous. These countries share common characteristics. They are highly integrated into EU research framework programmes and are also intensively developing physical digital innovation hubs, and implementing local broadband projects in remote rural areas. Their approach to the introduction of precision agriculture, which is based on the intensive use of digital technologies in farming, is also fundamental. Therefore, in order for a country to be a digital leader in the application of best practice, two factors appear to be important, i.e. firstly, the ability of actors in the country to engage in international research projects and, secondly, to have clearly targeted investments in the categories of the taxonomy, which uses a mix of all default conditions (hard, soft and virtual sphere).

For all of the lagging countries, there is one common trait, which is the lack of broadband coverage of rural areas. This corresponds with findings in academic research (Philip et al. Citation2017; Wilson et al. Citation2018; or Bowen and Morris Citation2019). However, the group of digital laggards is very diverse and, therefore, authors distinguish between three clusters of countries, i.e. Baltic, Visegrad and Danube countries.

The trichotomous cluster of the Baltics shows large differences between Estonia, on the one hand, and Lithuania and Latvia, on the other. Estonia appears to be a false laggard because it started to address this issue early and is now one of the digital leaders, not only in Europe. It is a paradox that approaches from this country have not been presented in the best practice at the EU level, which is probably due to the fact that most of Estonia's activities have been financed only from national sources. The authors do not consider such an approach to be appropriate, as the practices of a generally recognized digital leader should be an inspiration. Latvia represents, in essence, a ‘half’ leader because it shows a higher number of applied examples of best practice. It is represented in all of the identified categories except for accelerators, but these are generally underrepresented, even for all identified digitally active countries. In contrast, Lithuania is an outright digital laggard in best practice application. From this, it is evident that being a real digital leader requires having a long-term vision that the country can implement realistically and intensively (as with Estonia). It is also important, in addition to participating in the research framework programmes, to be unafraid to implement projects, cross-cutting in all the identified categories of best practice.

The cluster of Visegrad countries is relatively homogeneous, although Poland is slightly more active in examples of best practice. Characteristics of this group include the absence of physical digital innovation hubs, only online living labs, which greatly affects the availability of digital technologies in rural areas. This fact obviously has a negative impact on the ability of residents to acquire digital skills. The non-existence of DIHs in rural areas also reduces the opportunities for entrepreneurs who could use these spaces for their business. Since DIHs offer the security of stable connectivity, they provide space for testing new technologies, hosting events, or mentoring, and through them the synergistic potential of hard infrastructure, skills and the virtual sphere can be ideally exploited.

The cluster of Danube countries shows very weak involvement in best practice, only in two categories (smart village and DIH), but this is precisely because these projects are directly funded by the European Union. The complementary content analysis on national initiatives, showed some efforts on different activities that are related to informing about the opportunities that rural digitalization brings, but this is totally inadequate regarding the potential and possibilities of the digital economy at the threshold of the third decade of the new millennium. Default conditions are not sufficiently developed or supported in these countries.

The above-mentioned information shows that ICT infrastructure is a logical basis for the development of the digital economy (see e.g. Bowen and Morris Citation2019; Rotz et al. Citation2019a; Lai and Widmar Citation2021) but approaches that combine all default conditions are essential in order to fully develop the potential of the rural digital economy. In general, the main message from the analysis is relatively simple, namely, ‘make ICT infrastructure available and teach people how to use it’. However, there is also a need to look critically at the preparation and application of digitalization. In this context, it must be noted that examples of best practice can be very inspiring but, on the other hand, the well-known saying of rural studies that ‘one size does not fit to all situations’, still applies. The potential transfer of best practice must always be linked to the specific traits of rural regions and localities and must have its own uniqueness.

In terms of the policy making some key challenges clearly emerge. The need to accentuate synergies in the strategic planning of investments in hard and soft conditions of digital development seems to be crucial. At the same time, it should be noted that both are necessary to strengthen the virtual sphere, which represents the potential for reaping the benefits of the digital economy. Therefore, careful consideration should be given to the financing configuration of the respective investments. While the 2021–2027 programming period looks very positive for supporting the digitalization theme, the fragmentation of approaches and possible lack of coordination in the support that is provided is a major risk. These include mainstream ESIF, the EU’s Common Agriculture Policy funds, The Recovery and Resilience Facility, Just Transition Mechanism and national funding. For this reason, it is precisely those countries with inadequate and insufficient conditions in their digital agenda that should be very vigilant in the readiness of their peripheral stakeholders, in order to put concrete approaches and examples of digitalization into practice.

6. Conclusions

The uniqueness of the presented study lies in the fact that it systematizes specific approaches to reducing the urban-rural digital divide across key thematic categories in EU countries. This fills an existing research and policy-making gap, as existing solutions have been presented in rather isolated studies and analyzes. Therefore, the aim of this paper was to explore and interrogate existing approaches to reducing the urban-rural digital divide and creation of taxonomy of best practice examples. This context was analyzed in relation to the first research question, concerning the approaches of best practice that are used to bridge the urban-rural digital divide. Based on the existing literature, digital resilience stands on 2 default conditions (hard and soft). However, during the content analysis, the present authors elaborated one more default condition, namely, the virtual sphere. Within these conditions emerged a total of 7 thematic categories in the evaluated approaches. These categories form a taxonomy of best practice examples in the implementation of rural digitalization. In that, the current literature has not yet produced any framework typology of the main directions in digitalization (see the theoretical section), and that even strategic documents at the EU level usually do not contain specific procedures or examples of best practice, in order to achieve the desired objectives, which could be used as a guide for individual countries. This taxonomy of best practice examples can be crucial to inspire how individual goals can be achieved. The developed taxonomy will contribute scholars to the generation and refinement of theoretical knowledge. At the same time, it goes beyond the academic dimension and can help policymakers at all levels and other actors (private sector, NGOs, individuals) to navigate the issue and find the right solutions and approaches relevant to the context of their rural areas.

The second research question explored the differences in the activity of EU members in developing rural digitalization best practice. The analysis clearly showed a group of Western countries that can be of concern as digitally active. Their common characteristic is involvement in international research projects, development of physical digital innovation hubs in rural areas, local projects of broadband coverage, and engagement of all of the three default conditions. Countries that are identified as digital laggards are very diverse, and partial specifics were analyzed for clusters of Baltic countries, Visegrad countries and Danube countries. In general, however, it is possible to identify a common feature in these countries, i.e. inadequate broadband coverage. Unlike the digitally active countries, there are no efforts to create physical digital innovation hubs in rural areas, which greatly affects the availability of digital technologies in rural areas and reflects negatively on opportunities for digital skills and business development. Default conditions in these countries are not sufficiently developed or supported and, although there are some long-term visions of rural digitalization at national levels, their application is not adequate regarding the requirements of today's digital rural society.

The 2021–2027 programming period is, therefore, crucial for further bridging of the urban-rural digital divide in EU countries, as a wider range of funding is available to leverage this agenda. This does not include only the mainstream Structural Funds or the possibility to strengthen Agriculture 4.0 in the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development, but also the new Recovery and Resilience Facility, for which the EU has borrowed money for the first time in its history. This facility also supports, among other things, the digitalization of territories. Rural localities in coal regions will also be able to benefit from the Just Transition Fund, which will also channel funding for, among other things, digitalization. Therefore, a major challenge in the 2021–2027 programming period will be to significantly strengthen this agenda, and in a coordinated way, to promote the application of best-practice examples in all digitally less active countries. Finding synergies in the policy instruments used will not be easy and will be a crucial issue for EU Member States, not only in policymaking but also in ongoing and ex post policy evaluation. The importance of digitalization was also demonstrated during the Covid-19 pandemic, when it became clear that digitalization needed to be intensified. During both 2020 and 2021, it was evident that it is not just about the need for affordable broadband coverage, but that the options are much more complex. As the taxonomy in this paper demonstrates, it is necessary to choose approaches that consider a combination of all three default conditions.

The limitations of this paper stem from the fact that digitalization is a very dynamic and complex process. On the one hand, there are many different approaches in the practice of local and regional planning in bridging the urban-rural digital divide, which may not always be publicly presented either in the press, media or academic papers. Thus, this study is conditioned by the availability of key approaches presented on European and national platforms. Therefore, the generalization of the findings of the level of activity of particular countries in the digitalization process is limited in this study precisely by the availability of information on key approaches. On the other hand, examples of best practice in rural digitalization can emerge every day. To better understand the topic of bridging the urban-rural digital divide, it would be useful to analyze the context and implementation processes of particular best practice examples. However, for the current decade the authors assume that the taxonomy itself and its categories will be functional and applicable, not only in research, but also in policy making. It can be expected that new sub-categories may emerge in the coming decades, or that the currently defined categories may need to be slightly modified. This will require further research on the best practices, that can lead to a successful resolution of the digital divide between urban and rural areas.

Acknowledgements

The authors of this manuscript would also like to thank Dr. Matthew Copley for his proofreading and overall English editing.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alam, K., and M. Shahiduzzaman. 2014. “Shapin Our Economic Future: An E-impact Study of Small and Medium Enterprises in the Western Downs Region, Queensland.” University of Southern Queensland, Toowoomba. http://eprints.usq.edu.au/id/eprint/27420

- Alam, K., M. Erdiaw-Kwasie, M. Shahiduzzaman, and B. Ryan. 2018. “Assessing Regional Digital Competence: Digital Futures and Strategic Planning Implications.” Journal of Rural Studies 60: 60–69. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2018.02.009.

- Anitei, M., C. Veres, and A. Pisla. 2021. “Research on Challenges and Prospects of Digital Agriculture.” Proceedings 2020 63 (1): 67. doi:10.3390/proceedings2020063067.

- Ashmore, F., J. Farrington, and S. Skerratt. 2017. “Community-led Broadband in Rural Digital Infrastructure Development: Implications for Resilience.” Journal of Rural Studies 54: 408–425. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.09.004.

- Barzilai-Nahon, K. 2006. “Gaps and Bits: Conceptualizing Measurements for Digital Divide/s.” The Information Society 22 (5): 269–278. doi:10.1080/01972240600903953.

- Bowen, R., and W. Morris. 2019. “The Digital Divide: Implications for Agribusiness and Entrepreneurship. Lessons from Wales.” Journal of Rural Studies 72: 75–84. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.10.031.

- Briglauer, W., N. Dürr, O. Falck, and K. Hüschelrath. 2019. “Does State Aid for Broadband Deployment in Rural Areas Close the Digital and Economic Divide?” Information Economics and Policy 46: 68–85. doi:10.1016/j.infoecopol.2019.01.001.

- Corbin, J., and A. Strauss. 1990. “Grounded Theory Research: Procedures, Canons, and Evaluative Criteria.” Qualitative Sociology 13 (1): 3–21. doi:10.1007/BF00988593.

- Dubois, A., and F. Sielker. 2022. “Digitalization in Sparsely Populated Areas: Between Place-Based Practices and the Smart Region Agenda.” Regional Studies 56 (10): 1–12.

- Dyba, M., I. Gernego, O. Dyba, and A. Oliynyk. 2020. “Financial Support and Development of Digital Rural Hubs in Europe.” Management Theory and Studies for Rural Business and Infrastructure Development 42 (1): 51–59. doi:10.15544/mts.2020.06.

- Erdiaw-Kwasie, M., and K. Alam. 2016. “Towards Understanding Digital Divide in Rural Partnerships and Development: A Framework and Evidence from Rural Australia.” Journal of Rural Studies 43: 214–224. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2015.12.002.

- Esteban-Navarro, MÁ, MÁ García-Madurga, T. Morte-Nadal, and A. Nogales-Bocio. 2020. “The Rural Digital Divide in the Face of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Europe—Recommendations from a Scoping Review.” In Informatics (Vol. 7, No. 4, p. 54). Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute. doi:10.3390/informatics7040054

- Fertu, C., L. Dobrota, and S. Stanciu. 2019. “Precision Agriculture in Romania. Facts and Statistics.” In Proceedings of 34th International Business Information Management Association Conference: Vision 2025: Education Excellence and Management of Innovations Through Sustainable Economic Competitive Advantage. November 13-14, 2019, Madrid, Spain, edited by K. S. Soliman.

- Furuholt, B., and S. Kristiansen. 2007. “A Rural-Urban Digital Divide?” Regional Aspects of Internet use in Tanzania. The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries 31 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1002/j.1681-4835.2007.tb00215.x.

- Giannakis, E., and A. Bruggeman. 2020. “Regional Disparities in Economic Resilience in the European Union Across the Urban–Rural Divide.” Regional Studies 54 (9): 1200–1213. doi:10.1080/00343404.2019.1698720.

- Kalliokoski, J. 2017. “Incentives for Development of Entrepreneurship in Rural Areas through the RDP for Mainland Finland 2014 2020.” ENRD Seminar on the Rural Business Innovation. https://enrd.ec.europa.eu/sites/enrd/files/s4_rural-businesses-entrepreneurship_kalliokoski.pdf

- Kamińska, W. 2013. “Rural Areas in Poland: Educational Attainment vs. Level of Economic Development.” Quaestiones Geographicae 32 (4): 63–79. doi:10.2478/quageo-2013-0034.

- Kattel, R., and I. Mergel. 2019. “Estonia’s Digital Transformation: Mission Mystique and the Hiding Hand.” In Book: Great Policy Successes, edited by Paul't Hart, and Mallory Compton, 143–160. Oxford: Oxford Academic. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198843719.003.0008

- Keshet, Y. 2011. “Classification Systems in the Light of Sociology of Knowledge.” Journal of Documentation 67 (1): 144–158. doi:10.1108/00220411111105489.

- Kim, I., and J. Kuljis. 2010. “Applying Content Analysis to Web-Based Content.” Journal of Computing and Information Technology 18 (4): 369–375. doi:10.2498/cit.1001924.

- Kourilova, J. 2019. “Role lidských zdrojů v rozvoji venkovských oblastí v rámci nových výzev digitální ekonomiky – kontext pro formování nové politiky rozvoje venkova.” In Sborník příspěvků z 10. mezinárodní vědecké konference Region v rozvoji společnosti. November 10-11, 2019. Brno: Mendelova univerzita v Brně.

- Kos-Łabędowicz, J. 2017. “The Issue of Digital Divide in Rural Areas of the European Union.” Ekonomiczne Problemy Usług 126 (1): 195–204. doi:10.18276/epu.2017.126/2-20.

- Lai, J., and N. Widmar. 2021. “Revisiting the Digital Divide in the COVID-19 Era.” Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy 43 (1): 458–464. doi:10.1002/aepp.13104.

- Lembani, R., A. Gunter, M. Breines, and M. Dalu. 2020. “The Same Course, Different Access: The Digital Divide Between Urban and Rural Distance Education Students in South Africa.” Journal of Geography in Higher Education 44 (1): 70–84. doi:10.1080/03098265.2019.1694876.

- McFarland, C. 2018. Bridging the Urban–Rural Economic Divide. Washington, DC: National League of Cities. http://www.nlc.org/sites/default/files/2018-03/nlc-bridging-the-urban-rural-divide.pdf

- Michels, M., W. Fecke, J. Feil, O. Musshoff, F. Lülfs-Baden, and S. Krone. 2020. ““Anytime, Anyplace, Anywhere” A Sample Selection Model of Mobile Internet Adoption in German Agriculture.” Agribusiness 36 (2): 192–207. doi:10.1002/agr.21635.

- Morgan, A., A. Dix, M. Phillips, and C. House. 2014. “Blue Sky Thinking Meets Green Field Usability: Can Mobile Internet Software Engineering Bridge the Rural Divide?” Local Economy 29 (6–7): 750–761. doi:10.1177/0269094214548399.

- OECD. 2018. Bridging the Rural Digital Divide, OECD Digital Economy Papers, No. 265. Paris: OECD Publishing. doi:10.1787/852bd3b9-en.

- Onitsuka, K., A. Hidayat, and W. Huang. 2018. “Challenges for the Next Level of Digital Divide in Rural Indonesian Communities.” The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries 84 (2): e12021. doi:10.1002/isd2.12021.

- Park, S. 2017. “Digital Inequalities in Rural Australia: A Double Jeopardy of Remoteness and Social Exclusion.” Journal of Rural Studies 54: 399–407. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2015.12.018.

- Pelucha, M., and E. Kasabov. 2020. Rural Development in the Digital Age: Exploring Neo-Productivist EU Rural Policy. 1st ed. Abinngdon: Routledge. 242 p. Regions and Cities. ISBN 978-0-367-35658-3.

- Pelucha, M., J. Kourilova, E. Kasabov, and M. Feurich. 2021. “Expanding the Ontological Horizons of Rural Resilience in the Applied Agricultural Research Policy: The Case of the Czech Republic.” Journal of Rural Studies 82 (3): 340–350. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.01.030.

- Philip, L., C. Cottrill, J. Farrington, F. Williams, and F. Ashmore. 2017. “The Digital Divide: Patterns, Policy and Scenarios for Connecting the ‘Final Few’in Rural Communities Across Great Britain.” Journal of Rural Studies 54: 386–398. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.12.002.

- Popescu, M., B. Chiripuci, A. Orindaru, M. Constantin, and A. Scrieciu. 2020. “Fostering Sustainable Development Through Shifting Toward Rural Areas and Digitalization—The Case of Romanian Universities.” Sustainability 12 (10): 4020. doi:10.3390/su12104020.

- Rijswijk, K., L. Klerkx, M. Bacco, F. Bartolini, E. Bulten, L. Debruyne, J. Dessein, I. Scotti, and G. Brunori. 2021. “Digital Transformation of Agriculture and Rural Areas: A Socio-Cyber-Physical System Framework to Support Responsibilisation.” Journal of Rural Studies 85: 79–90. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.05.003.

- Roberts, E., B. Anderson, S. Skerratt, and J. Farrington. 2017a. “A Review of the Rural-Digital Policy Agenda from a Community Resilience Perspective.” Journal of Rural Studies 54: 372–385. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.03.001.

- Roberts, E., D. Beel, L. Philip, and L. Townsend. 2017b. “Rural Resilience in a Digital Society.” Journal of Rural Studies 54: 355–359. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2017.06.010.

- Rotz, S., E. Duncan, M. Small, J. Botschner, R. Dara, I. Mosby, M. Reed, and E. Fraser. 2019a. “The Politics of Digital Agricultural Technologies: A Preliminary Review.” Sociologia Ruralis 59 (2): 203–229. doi:10.1111/soru.12233.

- Rotz, S., E. Gravely, I. Mosby, E. Duncan, E. Finnis, M. Horgan, J. LeBlanc, R. Martin, H.T. Neufeld, A. Nixon, and E. Fraser. 2019b. “Automated Pastures and the Digital Divide: How Agricultural Technologies are Shaping Labour and Rural Communities.” Journal of Rural Studies 68: 112–122. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.01.023.

- Rundel, C., K. Salemink, and D. Strijker. 2020. “Exploring Rural Digital Hubs and Their Possible Contribution to Communities in Europe.” Journal of Rural and Community Development 15 (3).https://journals.brandonu.ca/jrcd/article/view/1793

- Salemink, K., D. Strijker, and G. Bosworth. 2017. “Rural Development in the Digital age: A Systematic Literature Review on Unequal ICT Availability, Adoption, and use in Rural Areas.” Journal of Rural Studies 54: 360–371. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2015.09.001.

- Somosi, S., and G. Számfira. 2020. “Agriculture 4.0 in Hungary: The Challenges of 4th Industrial Revolution in Hungarian Agriculture Within the Frameworks of the Common Agricultural Policy.” In 2020: Proceedings of the 4th Central European PhD Workshop on Technological Change and Development. University of Szeged, edited by B. Udvari, 162–189. http://eco.u-szeged.hu/download.php?docID = 105465

- Selwyn, N. 2004. “Reconsidering Political and Popular Understandings of the Digital Divide.” New Media & Society 6 (3): 341–362. doi:10.1177/1461444804042519.

- Townsend, L., A. Sathiaseelan, G. Fairhurst, and C. Wallace. 2013. “Enhanced Broadband Access as a Solution to the Social and Economic Problems of the Rural Digital Divide.” Local Economy 28 (6): 580–595. doi:10.1177/0269094213496974.

- Trendov, N., S. Varas, and M. Zeng. 2019. Digital Technologies in Agriculture and Rural Areas. FAO: Rome, Italy. ISBN: 978-92-5-131546-0. http://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/ca4985en/

- Van Dijk, J. 2006. “Digital Divide Research, Achievements and Shortcomings.” Poetics 34 (4–5): 221–235. doi:10.1016/j.poetic.2006.05.004

- Vassilakopoulou, P., and E. Hustad. 2021. “Bridging Digital Divides: A Literature Review and Research Agenda for Information Systems Research.” Information Systems Frontiers, 1–15. doi:10.1007/s10796-020-10096-3.

- Weare, C., and W. Lin. 2000. “Content Analysis of the World Wide Web: Opportunities and Challenges.” Social Science Computer Review 18 (3): 272–292. doi:10.1177/089443930001800304.

- Williams, F., L. Philip, J. Farrington, and G. Fairhurst. 2016. “Digital by Default’ and the ‘Hard to Reach’: Exploring Solutions to Digital Exclusion in Remote Rural Areas.” Local Economy 31 (7): 757–777. doi:10.1177/0269094216670938.

- Wilson, B., J. Atterton, J. Hart, M. Spencer, and S. Thomson. 2018. Unlocking the Digital Potential of Rural Areas Across the UK. London: Rural England. https://www.sruc.ac.uk/download/downloads/id/3613/unlocking_the_digital_potential_of_rural_are as_across_the_uk.pdf

- Wrzochalska, A., and B. Chmielevska. 2017. “Economic and Social Changes in Rural Areas in Poland.” Rural Areas and Development 14: 1–14. doi:10.22004/ag.econ.273083.

- Young, J. 2019. “Rural Digital Geographies and New landscapes of Social Resilience.” Journal of Rural Studies 70: 66–74. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.07.001

Online sources

- Aurorural. 2021. [Online 24.8.2021]. From: https://www.auroral.eu/#/p-about

- Beluhova-Uzunova, Rositsa, and Dobri Dunchev. 2021. Precison Agriculture in Bulgaria. [Online] August 8, 2021. https://ispag.org/article_display/?id = 609&title = Precision + Agriculture + in + Bulgaria

- CORA. 2021. Interreg VB North Sea Region Programme. [Online] August 24, 2021. https://northsearegion.eu/cora/

- Devillers, O. 2019. Le Pep’it LAB contribue à la Transition Numérique du Val d’Amboise. Banque des Territoires. [Online] August 23, 2021. https://www.banquedesterritoires.fr/le-pepit-lab-contribue-la- transition-numerique-du-val-damboise-37

- DESIRA. 2019. Digitisation: Economic and Social Impacts on Rural Areas. [Online] August 24, 2021. https://desira2020.eu/

- EC. 2019. Finnish co-operatives bring high-speed connectivity into the Arctic Circle. Shaping Europe’s Digital Future. [Online] August 24, 2021. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/news/finnish-co- operatives-bring-high-speed-connectivity-arctic-circle

- EC. 2020a. High-speed broadband for 25 rural communities in the mountainous Black Forest. Shaping Europe’s Digital Future. [Online] August 24, 2021. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/news/high- speed-broadband-25-rural-communities-mountainous-black-forest

- EC. 2020b. EU Funds Broadband Access for Underserved Households in Rural Latvia. [Online] August 24, 2021. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/news/eu-funds-broadband-access-underserved- households-rural-latvia

- EC. 2020c. EU Funds Bring High-Speed Broadband to Rural Lithuanian Agri-Businesses. [Online] August 24, 2021. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/news/eu-funds-bring-high-speed-broadband-rural- lithuanian-agri-businesses

- EC. 2021a. A long-term vision for the EU’s rural areas. European Commission. [Online] August 24, 2021. https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/new-push-european-democracy/long-term- vision-rural-areas_en#documents

- EC. 2021b. A Europe fit for the digital age. European Commission. [Online] August 24, 2021. https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/europe-fit-digital-age_en#documents

- EC. 2021c. “SmartAgriHubs.” Connecting the dots to unleash the innovation potential for digital transformation of the European agri-food sector. [Online] August 24, 2021. https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/818182

- EC. 2021d. Broadband in Romania. [Online] August 24, 2021. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/ policies/broadband-romania

- EC. 2021e. Broadband in Bulgaria. [Online] August 24, 2021. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/ policies/broadband-bulgaria

- ENRD. 2017a. “Short Food Supply Chain Masterclass.” ENRD case study: Rural Business Accelerators. Working Document. [Online] August 24, 2021. https://enrd.ec.europa.eu/sites/enrd/files/tg_rural- businesses_case-study_masterclass.pdf

- ENRD. 2017b. Academy on Tour. [Online] August 24, 2021. https://enrd.ec.europa.eu/projects- practice/academy-tour_en

- ENRD. 2017c. “AgriEnt Business Accelerator. ENRD Case Study: Rural Business Accelerators.” Working Document. [Online] August 24, 2021. https://enrd.ec.europa.eu/sites/enrd/files/tg_rural- businesses_case-study_agrient.pdf

- ENRD. 2017d. “#hellodigital. ENRD CASE STUDY: REVITALISING RURAL AREAS THROUGH DIGITISATION.” Working Document. [Online] August 24, 2021. https://enrd.ec.europa.eu/sites/enrd/files/tg_rural- businesses_case-study_hello-digital.pdf

- ENRD. 2017e. ENRD Seminar on ‘Revitalising Rural Areas through Business Innovation’. The European Network for Rural Development (ENRD). [Online] August 24, 2021. https://enrd.ec.europa.eu/news- events/events/enrd-seminar-smart-and-competitive-rural-businesses_en

- ENRD. 2018a. Smart Villages: ‘Reciprocity contracts’. The European Network for Rural Development (ENRD). [Online] August 24, 2021. https://enrd.ec.europa.eu/publications/smart-villages-reciprocity- contracts_en

- ENRD. 2018b. Smart Villages: ‘Smart countryside study’ The European Network for Rural Development (ENRD). [Online] August 24, 2021. https://enrd.ec.europa.eu/publications/smart-villages-smart- countryside-study_en

- LIVERUR. 2018. H2020 Innovative Business Model in Rural Areas. [Online] August 24, 2021. https://liverur.eu/

- ROBUST. 2021. Rural Urban Europe. [Online] August 24, 2021. https://rural-urban.eu/sites/default/files/MW_Good-practice_Village-Halls_end.pdf

- SmartAgriHubs. undated. South-East Europe Regional Cluster. [Online] August 24, 2021. https://www.smartagrihubs.eu/regional-cluster/south-east-europe

- SMART-AKIS. 2021. [Online] August 24, 2021. https://www.smart-akis.com/

- Smart Country. 2021. Projektbeschreibung. [Online] August 24, 2021. https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/de/unsere-projekte/smart-country/projektbeschreibung/

- Smart Rural Areas. 2021. Smart Rural Areas – in the 21st Century. [Online] August 24, 2021. https://www.smartrural21.eu/

- Smartrural21. 2021a. Remetea. [Online] August 24, 2021. https://www.smartrural21.eu/villages/remetea_ro/

- Smartrural21. 2021b. Brestovo. [Online] August 24, 2021. https://www.smartrural21.eu/villages/brestovo_bg/

- Smart Village Scotland. 2021. Smart Village Scotland Community. [Online] August 24, 2021. https://www.smartvillage.scot/