ABSTRACT

Digital platforms play a central role in the development of the Digital Entrepreneurial Ecosystem (DEE). The growing body of research addressing the issue of imbalances in DEEs has raised the challenge of how to recommend policies specifically designed to overcome the causes of such imbalances. This paper explores the issue of platformization in three developed and high-income countries in the European Union: Germany, France and Austria. The framework and empirical measurement of the Digital Platform Economy (DPE) Index are used to analyze the state of DEE in these three countries, identify the most prominent weaknesses that could be barriers, and propose policy recommendations to overcome these barriers and promote the development of DEE. The results of the three-step investigation present the current state of DEE in each country and find that similar constraining elements in the Digital Multi-Sided Platforms of the three countries have the most potential to systemically disrupt the DEE balance. Tailor-made policies with a holistic approach are recommended to address these constraining elements and target overall DEE growth. The results of this study are expected to motivate future research highlighting the issues surrounding multi-sided platform markets in the context of digital economic development in the European Union.

1. Introduction

Digital platforms have become an essential foundation of digital entrepreneurial ecosystems (DEE) as they shape economic interactions, mediate entrepreneurial activities, create value on a global scale, and drive ecosystem growth (Braune and Dana Citation2022; Cutolo and Kenney Citation2021). The DEE literature developed so far typically observes the activities, roles, and interactions of platform users in growing their businesses and how the externalities of these specific networks can be shaped by these interactions (Abdelkafi et al. Citation2019; Kraus et al. Citation2019; Steininger, Kathryn Brohman, and Block Citation2022; Trabucchi and Buganza Citation2021). What remains a challenge, however, is how these studies can translate their key findings into policy recommendations that meet the needs of policymakers.

The question, then, is why policy recommendations are so important and urgent in the context of DEEs. Recent studies on this topic may open our horizons to the fact that the imbalances in various DEE need tailor-made policy instruments. Fan, Schwab, and Geng (Citation2021) explored the activities of independent app developers in the entrepreneurial based ecosystem on the Facebook platform. The key findings of this study confirm that in promoting the platform, both app entrepreneurs and Facebook share similar motivations and goals, with strong background knowledge and experience in digital technology and continuous learning. However, this success can only be achieved if they are exposed to a stable and sustainable ecosystem. In another case, Cutolo and Kenney (Citation2021) point out that the actors around the platform have asymmetrical power. The platform may dominate the role in an ecosystem, but it may threaten the rights of other actors and may lead the platform to monopolistic behaviour. Ratajczak-Mrozek and Hauke-Lopes (Citation2022) point out that traditional industry entrepreneurs who use digital platform marketing methods are also faced with ecosystem imbalances where their role in this ecosystem tends to be marginalized due to their previous background in conventional business. Their dependence on the platform will threaten the existence of their business, especially if the platform is used as their only marketing medium. What is even more surprising is that even startups in the Aerospace Valley aerospace industry cluster in France that are large, established, and innovative still have strong dependencies with their primary industries (such as Air France Industries and Airbus) and have limited relational capacity to interact with global digital business networks (Gueguen, Delanoë-Gueguen, and Lechner Citation2021).

In the European context, Acs (Citation2022) uses the term European Dilemma to describe the condition of European platform economic activity in the global digital business environment. There is a concern that Europe's small role compared to the US in global digital business may be due to more systemic problems in the digital entrepreneurial ecosystem (DEE) and shortcomings in creating policy instruments to address them. In Acs et al. (Citation2020), these facts are generally shown in the Digital Platform Economy (DPE) Index 2020 study. Both studies essentially emphasize the importance of appropriate policy recommendations to address systemic issues in the European DEE. Although the issue of European platformization has been raised in previous studies, no study has yet shown what the specific conditions of digital entrepreneurship are in the member states, what systemic problems they face that may differ from each other, and what particular instruments can be used to assist these member states in generating policies that can address these systemic problems.

Against this background, this paper aims to address the gap in the DEE literature regarding the promotion of specific DEE policies and to raise the issue of platform-based economic activities in three developed and high-income European Union Member States, namely Germany, France, and Austria. The selection of the three countries is mainly motivated by their close economic, political, and socio-cultural relations and refers to the results of the DPE Index 2020 study (Acs et al. Citation2020), which indicates a strong relationship between DEE and development in the three countries. Three relevant research objectives were posed and addressed through three separate investigations. The first investigation analyzed the general profile of the Digital Entrepreneurship Ecosystem (DEE) to understand the characteristics of DEE in the three countries. The DPE sub-index level analysis was applied to identify the early symptoms that could cause an imbalance in the ecosystem. The second investigation was conducted at the pillar level of the DPE index to identify the bottleneck elements that cause ecosystem imbalance and are most likely to hinder the development of DEE. The third investigation was conducted to formulate proposed policy recommendations to overcome these bottlenecks, develop DEE or improve the DPE index. The results of this investigation show that despite the distinctive differences in the DEE profiles of the three countries, they share common problems in the digital multi-sided platform. However, each country ultimately requires different distinctive policies to overcome the related challenges, balance their DEs and EEs, or enhance future DEE development.

The next section of this paper presents the background literature on the concepts of Digital Entrepreneurial Ecosystem (DEE) and Digital Platform Economy (DPE) and the policy approach to develop DEE or improve the DPE index. The third section outlines the methodological steps to achieve the research objectives. The results of the analysis and discussion are presented in the fourth section. The paper ends with a conclusion in the fifth section.

2. Literature review

2.1. Digital entrepreneurial ecosystem (DEE) and digital platform economy index (DPE index)

The business ecosystem literature introduced by Moore (Citation1993) and Iansiti and Levien (Citation2004) was motivated by Tansley (Citation1935) original concept of ecosystems, which Nelson (Citation1985) expanded into the concept of a revolutionary economy. Subsequent ecosystem literature, such as entrepreneurial ecosystems, digital ecosystems, and platform ecosystems, developed along this main conceptual stream (Isenberg Citation2010; Rysman Citation2009; Stam Citation2015; Weill and Woerner Citation2015). Some other studies define ecosystems as places where a set of living things (biotic components) interact in complex ways within the physical environment (abiotic components) (Acs et al. Citation2020.; Acs et al. Citation2017; Szerb et al. Citation2020). This definition also assumes that the interactions of the two components in the ecosystem can be systematically analyzed to be a space for scientific practices. These perspectives then support the definition of an entrepreneurial ecosystem as a space where various individual resources are allocated and used to capture or generate new business creation opportunities and are influenced by the presence of entities or institutions (Acs, Autio, and Szerb Citation2014; Szerb, Ács, and Autio Citation2014).

In the era of digital networks, the conventional managed economy of the twentieth century has been replaced by the platform-based digital economy (digital ecosystem) of the twenty-first century (Williams Citation2021). In the managed economy, the literature on entrepreneurial ecosystems is highly developed. However, discussions tend to focus on local or regional issues and phenomena (Stam Citation2015). In contrast, the platform economy is more globalized due to the role of digital networks and technologies. Consequently, the elements of the digital ecosystem are also globally connected, which can broaden the base of users and agents.

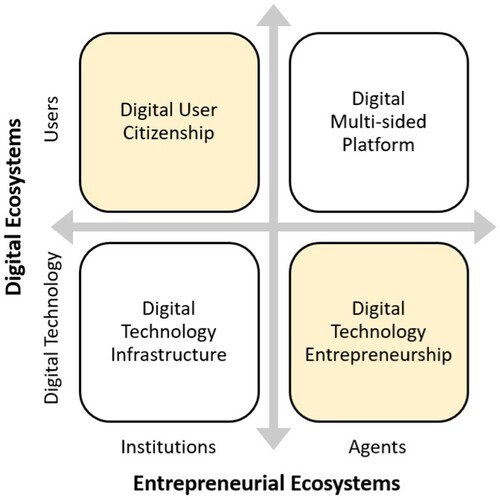

While the literature on these two ecosystems is growing, there is still a gap in the literature on how entrepreneurial ecosystems relate and interact with digital ecosystems (Cantner et al. Citation2021; Robertson, Pitt, and Ferreira Citation2020). Sussan and Acs (Citation2017) identified this gap and proposed a concept and framework for digital platform-based entrepreneurial ecosystems, called Digital Entrepreneurial Ecosystem (DEE). DEE integrates two major streams of literature, namely digital ecosystem (DE) and entrepreneurial ecosystem (EE). In the DEE framework, biotic entities (users and agents) are represented by individuals, while abiotic entities (digital technologies and institutions) build the business environment supported by various digital infrastructures. This framework was later reconfigured and refined by Song (Citation2019), who introduced a multi-sided platform that mediates the demand side and acts like a matchmaker to reduce transaction costs. Acs et al. (Citation2020) further developed this configured DEE framework into an empirical measure of the entrepreneurial ecosystem in relation to the digital ecosystem, called the Digital Platform Economy (DPE) Index.

The DPE Index is divided into four main elements (sub-indices), namely Digital User Citizenship (DUC), Digital Technology Entrepreneurship (DTE), Digital Multi-sided Platform (DMSP) and Digital Technology Infrastructure (DTI). DUC positions users on the demand and supply side. In this element, privacy is critical to be considered and protected. The trust of digital platform users is an essential asset in the digital platform ecosystem, because with trust, digital platform activities will be dynamic and sustainable. DTEs are application developers who create value on digital platforms. They also stimulate innovation in the ecosystem, disseminate knowledge and improve platform efficiency. DMSPs are intermediaries that facilitate the activities of agents and users in the ecosystem. Business competition on digital platforms is moving very fast. Highly competitive platforms will quickly deliver solutions to millions of users. Even those that are new and massively moving can replace established businesses (McAfee and Brynjolfsson Citation2017). DTI is a form of rules and regulations created by the government for the economic sustainability of digital platforms. It aims to ensure that activities in the ecosystem are conducive, safe, transparent, and maintain mutual trust. The four sub-indices of the DPE Index are shown in below.

Figure 1. Platform-based ecosystem. Source: (Song Citation2019) p.576.

2.2. Key components of the digital platform economy (DPE) index

This subsection outlines the components of the Digital Platform Economy (DPE) index (Acs et al. Citation2020). shows four sub-indices in the DPE Index (the super-index), each of which has three main pillars, for a total of twelve pillars. Each pillar comprises variables representing digital and entrepreneurial elements, making up 24 variables. A full description of all these components with its 61 indicators can be found in the appendix of Acs et al. (Citation2020).

2.2.1. Digital technology infrastructure (DTI)

Digital technology infrastructures (DTIs) create and govern the activities of all actors on a digital platform. The reconfiguration of DTI elements proposed by Song (Citation2019) emphasizes the importance of protecting digital access within a country from cyberattacks and hacks, which can threaten the security of user data and national digital security. This emphasis is consistent with the concept of openness and transparency in digital access proposed by Sussan and Acs (Citation2017). Strong data privacy protection must complement openness and transparency in digital platforms. This is due to the many uncertainties related to cybersecurity in digital platforms, which can also threaten the development of digital technology.

Creating a sustainable Digital Entrepreneurial Ecosystem (DEE) is one of the responsibilities of the government as a state manager and policy maker. Policy can improve the efficiency of the ecosystem, but it can also create inefficiencies through lengthy regulations. Therefore, regulation should promote economic productivity on digital platforms. Some examples of the critical role of regulation in DTI can be seen in the experiences of Russia and China, where the government closely monitors and controls the use of digital technology. On the one hand, the government directs digital platforms to create security and convenience for their users. On the other hand, an excessive role can stifle innovation in digital technology. Therefore, the rules set by the government need to keep up with the latest technological developments. Data protection that is too strict can make it difficult to use data to create digital technological progress and innovation.

2.2.2. Digital user citizenship (DUC)

Digital User Citizenship (DUC) is an element that connects the two sides of platform users, namely demand and supply. In a digital platform environment, demand and supply are carried out by highly heterogeneous individuals, so digital platforms can contain more than one user at a time (Rochet and Tirole Citation2003). Imagine Airbnb as a multi-sided platform where customers or potential guests are on the demand side, while hosts or property owners offering homes and services are on the supply side. Another example is Facebook. The demand and supply sides are represented by users moving from friend to friend, from business to business, and between app developers and advertizers (Evans and Schmalensee Citation2016). These two examples illustrate the multi-sided nature of digital platforms, where users conduct their activities through digital platforms on their digital or mobile devices, regardless of their position on the demand or supply side.

To keep digital platforms safe and conducive, before using various services or features on digital platforms, users are usually required to agree to the contract (terms and conditions) provided by the platform, which is regulated by the government. Platforms must maintain public trust and not misuse personal information provided by users. By maintaining these values, the participation of platform users will always increase sustainably.

2.2.3. Digital multi-sided platform (DMSP)

Platform-based digital businesses such as Airbnb and Facebook have grown significantly from startups to multi-billion-dollar unicorns (Cusumano, Gawer, and Yoffie Citation2019; Parker, van Alstyne, and Choudary Citation2016). They operate a business model as an intermediary or connector between two users (Parker and van Alstyne Citation2005; Rysman Citation2009). In the management literature, this business model is called a two-sided platform, which refers to the concept of a two-sided market (Rochet and Tirole Citation2003). Two-sided platforms are characterized by the presence of two or more (multi-sided) groups of users or customers (the external side), connecting them to the internal network of the digital platform (Trabucchi and Buganza Citation2020, Citation2022). From a two-sided market, initially known in the digital world as a two-sided platform, it has dynamically evolved into a multi-sided platform. Two-sided and multi-sided platforms are like landlords who manage resources that are not their own. Although it does not own the ‘original land’, this multi-sided platform can mediate and manage various external factors (from the side of customers and users) and invite them to comply with the rules in the internal environment of the platform.

According to Trabucchi and Buganza (Citation2020, Citation2022), platforms have two basic structures: Transactional and Orthogonal. In the transactional structure, platforms are seen as an operational choice to create business due to the advancement of digital technology. In the case of platforms such as Airbnb, platforms are viewed as an operational choice to create business by acting as an intermediary between the demand and supply sides. In an orthogonal structure, platforms are seen as an opportunity to create a variety of value-added services to enhance the sustainability of the business. In an orthogonal structure, there is no direct transaction on the platform. Two parties connect through the platform to be directed to monetized services (Evans and Schmalensee Citation2016; Parker and van Alstyne Citation2005; Teece Citation2018). For example, the Google search engine, where users are indirectly the source of opportunities for the platform to cover operating costs through the next party, the advertizers.

Digital multi-sided platforms (DMSPs) are digitally enabled, demand-driven intermediaries that organize the activities of agents and users on digital platforms through their matching capabilities to reduce search costs. Users are the source or matching base (e.g. potential Uber passengers) that create value on the platform (Evans and Schmalensee Citation2016; Teece Citation2018). In addition, the role of technology, mediated by the platform owner, helps users or intermediaries’ access, and take advantage of opportunities or transactions (Claussen, Kretschmer, and Mayrhofer Citation2013; Ghazawneh and Henfridsson Citation2013; Rohn et al. Citation2021). Platforms can grow through user feedback. Feedback interactions can be an important knowledge transfer channel for platform growth (Nambisan and Zahra Citation2016). User-driven diffusion of digital technologies accelerates this process. Network effects then arise from millions of user interactions, which create value for themselves and potentially attract other users.

2.2.4. Digital technology entrepreneurship (DTE)

Digital Technology Entrepreneurship (DTE) is any form of entrepreneurial activity that uses digital technology, innovation, experimentation, and value creation with digital technology. Experimentation, innovation, and value creation are the main activities that take place on a digital platform. These activities are generally carried out by application developers who build products according to the needs of the platform and provide various features, functions, benefits, and advantages to the users (Ekbia Citation2009; Kallinikos, Aaltonen, and Marton Citation2013). Major application developers, such as Apple with its App Store or Google with its Google Play, have adopted this process for digital platform companies (platformization). The goal is to reduce the costs of experimentation and product distribution for digital technology companies, and to meet the needs or provide solutions for users. The platformization process of Apple and Google also contributes to entrepreneurial innovation through the knowledge transfer process resulting from the interaction between users and digital platforms, such as customer feedback. With today's technology, the knowledge transfer process can be done without waiting for a long time. A user can provide feedback directly to the platform by rating or suggesting a comment (Hess and Ostrom Citation2007; Tapscott and Williams Citation2008).

The ability of digital platform firms to absorb critical knowledge from their user environment can pave the way for unlimited user-driven (demand-side) entrepreneurship opportunities. It should also be noted that platformization processes, such as those undertaken by Apple and Google, can stifle entrepreneurship, innovation, and profit opportunities. One of the reasons is the exorbitant costs that keep developers away, reducing the existing customer base and market. Not to mention, there is government interference in the platformization process, with various regulations that bind both developers and platform companies (Popiel and Sang Citation2021). Therefore, the platformization process should always be open to innovation to improve platform efficiency and build a sustainable DEE.

below shows the structure of the DPE Index with its sub-indices, pillars, and variables. The four main components outlined in this subsection reflect the general structure of the DPE Index.

Table 1. DPE Index structure.

Based on the descriptions in this subsection and referring to some of the Digital Entrepreneurial Ecosystem (DEE) phenomena described in the introduction, this research proposes two initial propositions that can reflect the relationship between the elements of the DPE Index and the profile of DEE in the three selected countries (Germany, France, and Austria). These propositions are related to the research objectives. The first proposition is to assume certain similarities or differences in the DEE profile in the three selected countries based on four sub-index elements of the DPE index. The second proposition is to assume similarities or differences in the profile of the DEE in the three countries based on the most prominent weaknesses in twelve pillars of the DPE Index that could potentially hinder the development of the DEE or disrupt the balance between the Entrepreneurial Ecosystem (EE) and Digital Ecosystem (DE).

2.3. Policy recommendations to develop the DEE or enhance the DPE index

The DPE Index is specifically designed to provide a holistic view of DEE performance at the country level (Acs et al. Citation2020). Symptoms that a country's DEE is not in a healthy state can be identified through the performance of the DPE Index by identifying gaps and bottlenecks in the ecosystem that require specific methods to address. By measuring the DPE Index, the Digital Ecosystem (DE) and Entrepreneurial Ecosystem (EE) profiles can be identified simultaneously in one system. The balance between DE and EE is optimal when all pillars are at the same level. Gaps identified in the structure of the DPE index are considered as constraints, indicating a low efficiency of the ecosystem. The worst performing element is considered to have the most significant inefficiency impact on the ecosystem. However, improving these bottleneck elements or pillars has a multiplier effect and will simultaneously and systemically improve the DPE index.

Furthermore, the DEE policy formulation is focused on allocating DE and EE resources to address the bottleneck pillars. This thinking is based on the concept of public policy in addressing market failures, where policy intervention can be applied to the weakest elements of a system. Thus, the application of bottleneck analysis to assess the performance of digital entrepreneurship in this case also has the potential to generate similar policy efficiencies (Autio et al. Citation2018; Mason and Brown Citation2014). Based on this description and with reference to the third research objective, the third proposition of the study is that the development of the DEE or the improvement of the DPE index can be made through policy recommendations that lead to holistic efforts to address the most prominent bottleneck pillars, the weakest, and the most potential to disrupt the balance of the ecosystem.

3. Research methodology

The study in this paper builds on the previous measurement results of the DPE Index 2020 for 116 countries. Using the same measurement methods and analysis techniques, this paper focuses on digital entrepreneurship in three EU member states: Germany, France, and Austria. To achieve the research objectives, three investigative steps are applied.

Investigation 1 analyzes the profile or state of digital entrepreneurship in the three countries. The previously conducted measurement of the 2020 DPE Index in 116 countries was referred to. The first twenty ranks of the 2020 DPE Index were analyzed, which the three countries were included in this group. The DEE profiles of the three countries by rank and index score are discussed here. In Investigation 1, the relationship between the DPE Index and development in the three countries, proxied by GDP per capita, is briefly presented.

In Investigation 2, the twelve pillars of the DPE Index, which represent all elements of the Digital Ecosystem (DE) and the Entrepreneurial Ecosystem (EE), are analyzed in more detail. This is a critical examination where bottleneck pillars are identified. The weakest pillar is considered to be the most significant bottleneck that has the potential to disrupt the balance of the ecosystem. Finding these weakest pillars is crucial for recommending policies to develop the DEE or improve the DPE index.

In Investigation 3, the position of each country is grouped into quadrants based on two categories: the composition between the Digital Ecosystem (DE) and the Entrepreneurial Ecosystem (EE), and the composition between the actual DPE Index score and the implied trend line of the DPE Index development. The formulation of policy suggestions to be proposed was set by targeting a 10% increase in the DPE Index. Based on this, the directions and efforts required to develop the overall DEE component are proposed.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Investigation 1: basic analysis

below shows the position of the three countries, where the light blue colour marks the three countries analyzed.

Table 2. Top 20 DPE Index 2020.

shows that Germany (rank 14, DPE index = 64.4) is ahead of France (rank 15, DPE index = 63.6) and Austria (rank 20, DPE index = 57.0). The other four EU member states in this second top 10 are Ireland, Iceland, Belgium, and Estonia. Then there is a Pacific country, New Zealand, a non-EU country, Luxembourg, and an Asian country, Hong Kong. These countries are classified as developed, innovative and high-income countries. also shows that the three countries selected in this study are far behind other strong countries in the European Union, such as the Scandinavian countries and Switzerland. The difference in scores between Germany and France is only 0.8. Meanwhile, Austria has a significant score difference of 7.4 from Germany and 6.6 from France.

To identify what makes these three countries different, we need to look at the sub-index components that make up the DPE index. below shows the sub-index scores of the three countries.

Table 3. The sub-index scores of the three countries.

shows that Germany ranks first in Digital Technology Infrastructure (DTI) and Digital User Citizenship (DUC), but second in Digital Technology Entrepreneurship (DTE) and Digital Multi-Site Platform (DMSP) (lowest score). France ranks second in DTI and DUC, but first in DTE and DMSP (lowest score). Meanwhile, Austria is at the bottom of all sub-indices and, like the other two countries, has the lowest score for DMSP. Germany and France look similar on all four sub-indices, but what distinguishes them is Germany's DMSP score, which is 4 points lower than that of France. This condition indicates more problems in the DMSP elements in Germany than in France. The difference between the Austrian and French DMSP scores is 10.3 points. Germany could be a benchmark for the DTI and DUC sub-indexes as it has the highest score. France is 2.4 points behind on DTI and 7.0 points behind on DUC. Austria is furthest behind on DUC (9.7 points) and DTI (6.9 points).

Apart from the two different sub-indices of DUC and DTE, the three countries have similarities in the other two, DTI and DMSP. DTI ranks first among the three indices, while DMSP ranks last. If we consider the status of the three countries, there is no doubt how the development of digital technology infrastructure in these countries. As mentioned in Acs et al. (Citation2020) and Sussan and Acs (Citation2017), DTI is a governance-related issue that aims to create appropriate institutional standards for the development of digital technology. It is essential that every citizen has adequate access to digital technologies, and the development of digital technologies should be supported by freedoms and clear rules and laws that can protect digital users and digital technology developers from cybercrime. Undoubtedly, this kind of infrastructure is well-developed in these countries.

On the other hand, there are still concerns and this research shows that multi-sided platforms could have been better developed in the EU market. For example, Germany, which is a leader in many respects, has significant shortcomings compared to France and Austria when it comes to multi-sided markets. In terms of infrastructure, all three countries are highly developed. However, when it comes to using this infrastructure for DEE development, there is still a noticeable gap in activity on multi-sided platform. As configured by Song (Citation2019), multi-sided platforms are a crucial element of the platform economy. Not only should the network within the platform develop, but the externalities of the network formed within the platform also perform well. The measures used in the DMSP focus on the platform's activities as a matchmaker in the multi-sided market for agents and users. Ultimately, the platform's role is to facilitate the formation of business and consumer networks for social and financial interactions, and externalities effects such as knowledge sharing, innovation, and value creation should also be part of the platform's activities. At this point, this research investigation shows that these effects are still weak in all three countries.

The results of the first investigation confirm the first proposition, which assumes similarities and differences among the three countries in the Digital Entrepreneurial Ecosystem (DEE) profile based on the four main elements of the Digital Platform Economy (DPE) index.

4.2. Investigation 2: twelve pillars analysis

In the second investigation, the analysis was conducted in more detail based on the twelve pillars that make up the DPE index. shows the grouping of countries based on the twelve pillars analysis. Countries are grouped into Leaders, Followers, Gainers, and Laggards. The average DPE Index scores of each group are 77.7, 61.3, 35.9, and 17.4. There are seven countries in the Leaders group, 20 countries in the Followers group, and 35 countries in the Gainers group. Germany, France, and Austria are in the Followers group based on this grouping.

Table 4. The four groups of the countries and average pillar scores based on the twelve pillars.

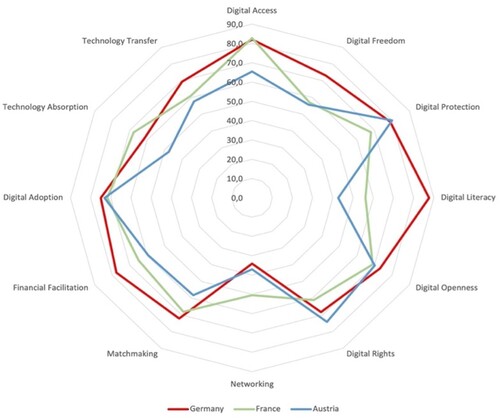

below shows the performance of the twelve pillars for Germany, France, and Austria.

Table 5. Perform of twelve pillars of three countries.

Across the three pillars of the Digital Technology Infrastructure (DTI) sub-index, all three countries show similar weaknesses in terms of Digital Freedom. Germany performs better, while France and Austria lag behind. The same is found in the Digital Multisided Platform (DMSP) pillars. All three countries have similar weaknesses in the Networking pillar. France performs better than the other two countries, followed by Austria and Germany. At this point, all three countries have the same characteristics in the Digital Technology Infrastructure (DTI) and Digital Multisided Platform (DMSP) pillars. The Networking pillar, which is part of the DMSP sub-index, is the most prominent weakness.

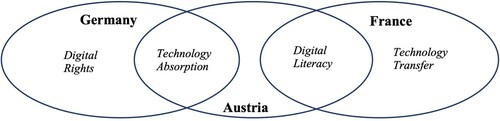

The three countries differ in their characteristics on the Digital User Citizenship (DUC) and Digital Technology Entrepreneurship (DTE) subindices. For DUC, Germany is weak in the digital rights, while France and Austria are weak in the digital literacy. For DTE, Germany and Austria are weak in the technology absorption, while France is weak in the technology transfer. It can also be stated that Germany is weak in the Digital Rights and Technology Absorption, France is weak in Digital Literacy and Technology Transfer, and Austria is weak in Digital Literacy and Technology Absorption.

This condition is consistent with what is stated in Acs et al. (Citation2020), where one of the characteristics of the Followers group is the weakness of the country on the Digital Literacy and Technology Absorption, while the Gainers group is usually weak on the Networking and Technology Absorption. In other words, Technology Absorption is the greatest weakness for the Followers and Gainers groups. Since the three countries do not have identical weaknesses, but there are intersections in certain pillars, below shows the weakest pillars of the three countries in the DUC and DTE sub-indices.

shows another form of weakness in the pillars of the three countries described above.

According to Acs et al. (Citation2020), competition is crucial for the development of a digital multi-sided platform (DMSP). A sustainable DMSP can be created by preventing digital platforms from engaging in monopolistic behaviour, as it disrupts market competition and hinders entrepreneurial activities. However, the opposite has recently been confirmed in Europe, where Google has been sanctioned three times for antitrust issues (Hovenkamp Citation2021; Iacobucci and Ducci Citation2019; Monti Citation2022). Google directs users to use its shopping platform and blocks its competitors from advertising opportunities. If the government does not intervene to control the market, similar problems could occur not only with a company as powerful as Google, but also with other platforms. Since one of the main functions of platforms is to act as a matchmaker that allows users and agents to access different opportunities, antitrust violations have the potential to disrupt the ecosystem (Gleiss, Degen, and Pousttchi Citation2023; Sandner and Kaiser Citation2023; Vergne Citation2020). This can lead to negative feedback that hinders knowledge transfer and innovation on the platform (Nguyen Citation2021; Nguyen and Malik Citation2020; Sun et al. Citation2019). The negative interactions will ultimately have a negative impact on the platform's business network or the digital ecosystem. There will be less new value creation, and fewer users will come to the platform. This will certainly have a significant impact on the DEE balance.

Another issue that may contribute to low economic activity on multi-sided platforms is the low participation of users and agents in the use of social networks (virtual professionals and social media) in business (B2B and B2C) (Loux et al. Citation2020; Muzellec, Ronteau, and Lambkin Citation2015; Wallbach et al. Citation2019). Internet technologies may be highly developed in Europe. However, users’ and agents’ trust in the platform still needs to be improved. In the results of this second investigation, not only did the Networking pillar emerge as the weakest element in the DMSP or the DPE in general, but the same weakness was also found in the Digital Freedom pillar, which is a constituent element of the DTI. At the same time, DTI is also the strongest sub-index in all three countries. This phenomenon indicates that the digital infrastructure in the three countries has not realized the optimal externalities of a multi-sided platform. These weaknesses could potentially disrupt the equilibrium or hinder the development of DEE.

The results of this investigation confirm the second proposition, which assumes the existence of the most prominent weakness (bottleneck pillar) within the twelve constituent pillars of the DPE Index.

4.3. Investigation 3: policy recommendations

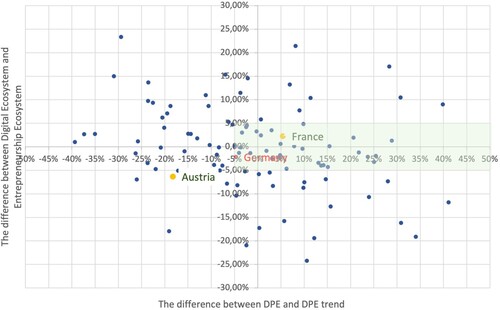

shows the position of the three countries in the quadrants that separate the Digital Ecosystem (DE) and the Entrepreneurial Ecosystem (EE) by the X-axis, and that separate the countries based on the actual development of the DPE relative to the development trend of the DPE Index by the Y-axis. Countries above the X-axis have a better Digital Ecosystem (DE) than Entrepreneurial Ecosystem (EE) and vice versa. Countries considered to have a balanced and optimal DEE are indicated by their position above the trend line, and the difference between the DPE trend and their actual DPE is within +/- 10%.

Figure 4. Positions of Germany, France and Austria based on the difference in DE and EE scores and deviations from the implied trendline of the DPE Index development. Source: data elaborated.

Of the three countries, only France has a better DE than its EE (above the x-axis). Germany and Austria are below the x-axis, indicating that both countries need to improve their DE more. For DPE, France and Germany are above the trend line, while Austria is below the trend line. France is best positioned in these plots, with its DE better than its EE, and its DPE trend above the trend line. Germany is also above the DPE trend line, but unfortunately its DE is no better than its EE. Meanwhile, Austria is weak in both categories.

The balance between DE-EE and deviation from the DPE index trend line is then used as a guideline to formulate policy recommendations for the three countries, as shown in .

Table 6. Suggested policy recommendations.

The formulation shown in is used if the three countries intend to formulate a policy that targets a 10% increase in the DPE index. The average increase in the DPE index that can be achieved by implementing this policy is a total increase of 0.6 points. In this case, Germany needs a full push to improve the Networking pillar, which could then increase the DMSP sub-index by 1.02 points, while the other three sub-indexes would increase without significant effort. By implementing this policy, Germany's DPE index is expected to increase by 6.4 points (DPE index = 70.8).

Table 7. Policy suggestion formulation targeting a 10% increase in DPE-Index score.

On the other hand, France will need a policy push to improve two pillars of the DTI sub-index, namely Digital Freedom and Digital Protection. Digital Literacy and Digital Rights in the DUC sub-index also need a significant boost. The most notable effort is required for the Networking pillar. In the case of France, it is noteworthy that the implementation of these policy recommendations will require significant efforts in all subindices and almost all pillars to reach the target of increasing the DPE index by 6.3 points (DPE index = 69.9). Austria needs a policy push to improve the Digital Literacy, Networking and Technology Adoption. The Networking pillar requires the most effort, as it has the lowest score both within the country and across countries. These efforts would increase Austria's DPE index by 5.7 points (DPE index = 62.7).

The main goal and expectation of most DEE studies is how to address different ecosystem imbalances with tailored policies or policies that can address systemic problems that affect the whole ecosystem rather than ‘one-size-fits-all’ policies (Mason and Brown Citation2014; Ortega-Argilés Citation2022; Szerb et al. Citation2022). Discussing DE and EE as a whole context in DEE will provide more benefits, although we still need to study and observe each component separately (Zhai et al. Citation2023). Let's take the case of Germany, where Germany implicitly shows a stronger EE condition than its DE in this study. This is natural given its highly developed and innovative entrepreneurial development background (Audretsch et al. Citation2019; Bischoff Citation2021). However, Germany still faces challenges in developing its DE, which has led to suboptimal growth in its DEE. Then, in the case of France, its position is quite favourable based on the results. However, to achieve optimal DEE growth, France needs to make significant efforts in almost all its DE and EE components, while Germany can achieve its optimal DEE growth target by focusing all its efforts on only one of the components (Networking - DMSP), while allowing the other elements to grow without a significant push. Austria seems to be unlucky in this respect. Despite having the same main inhibiting element as the other two countries, Austria faces an imbalance in another very fundamental pillar: Digital Literacy and Technology Adoption. In the context of local innovation and entrepreneurship systems, Brunetti et al. (Citation2020) call this a multidimensional digital transformation challenge. With the same target to improve the DPE index (10%), Germany and France could swap positions in the future, but Austria still has a long way to go to catch up.

When formulating policies to improve the DPE index or DEE growth, we cannot consider all DEE elements and then develop them into a ‘one-size-fits-all’ policy because not all elements are equally important (Torres and Godinho Citation2022). Therefore, Investigation 1, which showed that DMSP is a weak sub-index, is a useful way to detect early problems in the ecosystem. We can see components of a country's DEE that show symptoms that can weaken and affect the DEE systemically.

To delve deeper into the causes of weak DMSP components, Investigation 2 should be applied to find the bottleneck elements in the ecosystem. We chose an appropriate step to formulate future policy advice based on the holistic paradigm of identifying the bottleneck pillars that disrupt the ecosystem (Khatami et al. Citation2021; Xu and Dobson Citation2019). Using this paradigm and following the policy formulation pattern of Acs et al. (Citation2020), we aim to increase the DPE index while referring to the DEE conditions of each country found in the previous two stages of the investigation. Ultimately, the resulting policy recommendations address the truly problematic elements.

Each country may have different constraining elements, resulting in different policy recommendations. In the case of our three countries, although they all have the same problem on the Networking pillar/sub-index of DMSP, due to the different conditions of DE, EE, and the development trend of DPE, it ultimately results in different policy suggestions. At this point, the third proposition of this study has been validated.

5. Conclusion

This paper analyzes the state of the Digital Entrepreneurial Ecosystem (DEE) in the context of EU Member States using the latest empirical measure of DEE, the Digital Platform Economy (DPE) Index 2020. Three developed and high-income countries, Germany, France, and Austria, were selected to uncover the profile of DEEs in the three countries, identify the most prominent barriers, and propose policy recommendations to overcome the barriers and foster DEE development. Using a three-step investigation, the main findings were outlined.

The first investigation revealed that while the level of Digital Technology Infrastructure (DTI) is the superior sub-index in the three countries, they also share the same weakness in Digital Multi-Sided Platform (DMSP), which contains critical elements for the platform economy. Lack of trust due to weak protection of digital freedoms potentially leads to negative interactions on digital platforms. This in turn leads to low activity, participation, and lack of massive network formation within the platform ecosystem, as discussed in the second investigation. Policy formulation in the third investigation with a holistic approach and the same DEE development target may result in specific and different policy recommendations in the three countries, even though the three countries have the same weaknesses. This is due to the different profiles of DEEs and other bottleneck pillars. The policy formulation applied in this study focused on the weakest constraints in the ecosystem and did not take into account all elements. However, in the end, the existing conditions of DEEs in these countries will determine which elements need to be improved and how much effort they should put in to increase the DPE index to the target.

Based on the investigation conducted in this paper, previous research claiming a strong correlation between DEE and a country's economic development raises further questions. This is because France has the lowest GDP per capita among the three countries and has performed well in the digital platform ecosystem. In contrast, Germany and Austria have higher GDP per capita and have serious challenges in their digital platform ecosystems. Future studies are strongly recommended to address the multi-sided platforms concerning economic development in EU countries, a limitation that this paper cannot tackle.

This paper tries to fill the gap in DEE studies by addressing the causes of imbalances that have systemic impacts on ecosystems and how to recommend policies specifically designed to overcome these barriers. Other studies using the DPE index and addressing the issue of European platformization have begun to develop, and this paper is expected to be one of the motivating ones. Although this paper attempts to present its own construct, it is advisable to relate this paper to existing research on the measurement of the DPE index. While this study takes the context of developed countries in the EU and finds serious concerns related to the platform economy, future studies may raise the same issue in the context of less developed countries or countries with transitional economies in the EU.

Author biography

Eristian Wibisono holds a master’s degree in Economics from Jambi University (Indonesia). He is currently pursuing his PhD in Regional Development at the University of Pecs, Hungary and is a research fellow on the Policies for Smart Specialization (POLISS) consortium research project funded under the European Union's H2020 Research and Innovation Programme. He is also a civil servant at the Jambi Province Industry and Trade Office, Indonesia. His research interests are regional economics, innovation and technology, entrepreneurship, and European regional research and innovation policies.

Acknowledgment

The author gratefully acknowledges the support provided by POLISS (https://poliss.eu), the funded project under European Union’s H2020 Research and Innovation Programme, Grant Agreement No. 860887. Views and opinions are only those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

The author would also like to thank Professor Laszlo Szerb, Professor Tamás Sebestyén, and two anonymous reviewers for their constructive criticism and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abdelkafi, N., C. Raasch, A. Roth, and R. Srinivasan. 2019. “Multi-Sided Platforms.” In Electronic Markets, (Vol. 29, 553–559). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-019-00385-4

- Acs, Z. 2022. “The Digital Platform Economy and the Entrepreneurial State: A European Dilemma.” In Questioning the Entrepreneurial State: Status-quo, Pitfalls, and the Need for Credible Innovation Policy, 317–344. Cham:Springer International Publishing Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-94273-1_17

- Acs, Z., E. Autio, and L. Szerb. 2014. “National Systems of Entrepreneurship: Measurement Issues and Policy Implications.” Research Policy 43 (3): 476–494. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2013.08.016.

- Acs, Z., E. Stam, D. Audretsch, and A. O’Connor. 2017a. “The Lineages of the Entrepreneurial Ecosystem Approach.” Small Business Economics 49 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1007/s11187-017-9864-8.

- Acs, Z., L. Szerb, A. Song, E. Komlosi, and E. Lafuente. 2020. The Digital Platform Economy Index 2020. Barcelona: The Global Entrepreneurship and Development Institute.

- Audretsch, D., J. Cunningham, D. Kuratko, E. Lehmann, and M. Menter. 2019. “Entrepreneurial Ecosystems: Economic, Technological, and Societal Impacts.” The Journal of Technology Transfer 44: 313–325. doi:10.1007/s10961-018-9690-4.

- Autio, E., L. Szerb, É Komlósi, and M. Tiszberger. 2018. The European index of digital entrepreneurship systems. Publications Office of the European Union (Ed.), JRC Technical Reports, 153.

- Bischoff, K. 2021. “A Study on the Perceived Strength of Sustainable Entrepreneurial Ecosystems on the Dimensions of Stakeholder Theory and Culture.” Small Business Economics 56: 1121–1140. doi:10.1007/s11187-019-00257-3.

- Braune, E., and L. Dana. 2022. “Digital Entrepreneurship: Some Features of new Social Interactions.” Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences / Revue Canadienne des Sciences de L'Administration 39 (3): 237–243. doi:10.1002/cjas.1653.

- Brunetti, F., D. Matt, A. Bonfanti, A. De Longhi, G. Pedrini, and G. Orzes. 2020. “Digital Transformation Challenges: Strategies Emerging from a Multi-Stakeholder Approach.” The TQM Journal 32 (4): 697–724. doi:10.1108/TQM-12-2019-0309.

- Cantner, U., J. Cunningham, E. Lehmann, and M. Menter. 2021. “Entrepreneurial Ecosystems: A Dynamic Lifecycle Model.” Small Business Economics 57: 407–423. doi:10.1007/s11187-020-00316-0.

- Claussen, J., T. Kretschmer, and P. Mayrhofer. 2013. “The Effects of Rewarding User Engagement: The Case of Facebook Apps.” Information Systems Research 24 (1): 186–200. doi:10.1287/isre.1120.0467.

- Cusumano, M., A. Gawer, and D. Yoffie. 2019. The Business of Platforms: Strategy in the age of Digital Competition, Innovation, and Power (Vol. 320). New York: Harper Business.

- Cutolo, D., and M. Kenney. 2021. “Platform-dependent Entrepreneurs: Power Asymmetries, Risks, and Strategies in the Platform Economy.” Academy of Management Perspectives 35 (4): 584–605. doi:10.5465/amp.2019.0103.

- Ekbia, H. 2009. “Digital Artifacts as Quasi-Objects: Qualification, Mediation, and Materiality.” Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 60 (12): 2554–2566. doi:10.1002/asi.21189.

- Evans, D., and R. Schmalensee. 2016. Matchmakers: The new Economics of Multisided Platforms. Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business Review Press.

- Fan, T., A. Schwab, and X. Geng. 2021. “Habitual Entrepreneurship in Digital Platform Ecosystems: A Time-Contingent Model of Learning from Prior Software Project Experiences.” Journal of Business Venturing 36 (5): 106140. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2021.106140.

- Ghazawneh, A., and O. Henfridsson. 2013. “Balancing Platform Control and External Contribution in Third-Party Development: The Boundary Resources Model.” Information Systems Journal 23 (2): 173–192. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2575.2012.00406.x.

- Gleiss, A., K. Degen, and K. Pousttchi. 2023. “Identifying the Patterns: Towards a Systematic Approach to Digital Platform Regulation.” Journal of Information Technology 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/02683962221146803

- Gueguen, G., S. Delanoë-Gueguen, and C. Lechner. 2021. “Start-ups in Entrepreneurial Ecosystems: The Role of Relational Capacity.” Management Decision 59 (13): 115–135. doi:10.1108/MD-06-2020-0692.

- Hess, C., and E. Ostrom. 2007. Understanding Knowledge as a Commons: From Theory to Practice. Cambridge, Massachusetts: JSTOR.

- Hovenkamp, H. 2021. “Antitrust and Platform Monopoly.” YALE LAW JOURNAL 130(8), 1952–2050. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/agispt.20210716050117

- Iacobucci, E., and F. Ducci. 2019. “The Google Search Case in Europe: Tying and the Single Monopoly Profit Theorem in two-Sided Markets.” European Journal of Law and Economics 47: 15–42. doi:10.1007/s10657-018-9602-y.

- Iansiti, M., and R. Levien. 2004. “Strategy as Ecology.” Harvard Business Review 82 (3): 68–78. https://europepmc.org/article/med/15029791

- Isenberg, D. 2010. “How to Start an Entrepreneurial Revolution.” Harvard Business Review 88 (6): 40–50. In press.

- Kallinikos, J., A. Aaltonen, and A. Marton. 2013. “The Ambivalent Ontology of Digital Artifacts.” Mis Quarterly, 357–370. doi:10.25300/MISQ/2013/37.2.02.

- Khatami, F., V. Scuotto, N. Krueger, and V. Cantino. 2021. “The Influence of the Entrepreneurial Ecosystem Model on Sustainable Innovation from a Macro-Level Lens.” International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-021-00788-w

- Kraus, S., C. Palmer, N. Kailer, F. Kallinger, and J. Spitzer. 2019. “Digital Entrepreneurship: A Research Agenda on new Business Models for the Twenty-First Century.” International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research 25 (2): 353–375. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-06-2018-0425

- Loux, P., M. Aubry, S. Tran, and E. Baudoin. 2020. “Multi-sided Platforms in B2B Contexts: The Role of Affiliation Costs and Interdependencies in Adoption Decisions.” Industrial Marketing Management 84: 212–223. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2019.07.001.

- Mason, C., and R. Brown. 2014. “Entrepreneurial Ecosystems and Growth Oriented Entrepreneurship.” Final Report to OECD, Paris 30 (1): 77–102. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/260870819_ENTREPRENEURIAL_ECOSYSTEMS_AND_GROWTH_ORIENTED_ENTREPRENEURSHIP_Background_paper_prepared_for_the_workshop_organised_by_the_OECD_LEED_Programme_and_the_Dutch_Ministry_of_Economic_Affairs_on

- McAfee, A., and E. Brynjolfsson. 2017. Machine, Platform, Crowd: Harnessing our Digital Future. New York, NY: WW Norton & Company.

- Monti, G. 2022. “Taming Digital Monopolies: A Comparative Account of the Evolution of Antitrust and Regulation in the European Union and the United States.” The Antitrust Bulletin 67 (1): 40–68. doi:10.1177/0003603X211066978.

- Moore, J. 1993. “Predators and Prey: A new Ecology of Competition.” Harvard Business Review 71 (3): 75–86. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/13172133_Predators_and_Prey_A_New_Ecology_of_Competition

- Muzellec, L., S. Ronteau, and M. Lambkin. 2015. “Two-Sided Internet Platforms: A Business Model Lifecycle Perspective.” Industrial Marketing Management 45: 139–150. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2015.02.012.

- Nambisan, S., and S. Zahra. 2016. “The Role of Demand-Side Narratives in Opportunity Formation and Enactment.” Journal of Business Venturing Insights 5: 70–75. doi:10.1016/j.jbvi.2016.05.001.

- Nelson, R. 1985. An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Nguyen, T. 2021. “Four-dimensional Model: A Literature Review in Online Organisational Knowledge Sharing.” VINE Journal of Information and Knowledge Management Systems 51 (1): 109–138. doi:10.1108/VJIKMS-05-2019-0077.

- Nguyen, T., and A. Malik. 2020. “Cognitive Processes, Rewards and Online Knowledge Sharing Behaviour: The Moderating Effect of Organisational Innovation.” Journal of Knowledge Management 24 (6): 1241–1261. doi:10.1108/JKM-12-2019-0742.

- Ortega-Argilés, R. 2022. “The Evolution of Regional Entrepreneurship Policies: “no one Size Fits all”.” The Annals of Regional Science 69 (3): 585–610. doi:10.1007/s00168-022-01128-8.

- Parker, G., and M. van Alstyne. 2005. “Two-Sided Network Effects: A Theory of Information Product Design.” Management Science 51 (10): 1494–1504. doi:10.1287/mnsc.1050.0400.

- Parker, G., M. van Alstyne, and S. Choudary. 2016. Platform Revolution: How Networked Markets are Transforming the Economy and how to Make Them Work for you. New York, NY: WW Norton & Company.

- Popiel, P., and Y. Sang. 2021. “Platforms’ Governance: Analyzing Digital Platforms’ Policy Preferences.” Global Perspectives 2 (1), doi:10.1525/gp.2021.19094.

- Ratajczak-Mrozek, M., and A. Hauke-Lopes. 2022. “Digital Entrepreneurial Ecosystems of Traditional Companies – A Case Study.” Problemy Zarządzania - Management Issues 20 (1/2022 95): 67–86. doi:10.7172/1644-9584.95.3.

- Robertson, J., L. Pitt, and C. Ferreira. 2020. “Entrepreneurial Ecosystems and the Public Sector: A Bibliographic Analysis.” Socio-Economic Planning Sciences 72: 100862. doi:10.1016/j.seps.2020.100862.

- Rochet, J., and J. Tirole. 2003. “Platform Competition in Two-Sided Markets.” Journal of the European Economic Association 1 (4): 990–1029. doi:10.1162/154247603322493212.

- Rohn, D., P. Bican, A. Brem, S. Kraus, and T. Clauss. 2021. “Digital Platform-Based Business Models – An Exploration of Critical Success Factors.” Journal of Engineering and Technology Management 60: 101625. doi:10.1016/j.jengtecman.2021.101625.

- Rysman, M. 2009. “The Economics of Two-Sided Markets.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 23 (3): 125–143. doi:10.1257/jep.23.3.125.

- Sandner, P., and M. Kaiser. 2023. “Decentralized Marketplace Structures as Protection Against Information Asymmetries: How Platform Business Models Can be Challenged With Blockchain Architectures and How Companies Can Monetise Data in This Scenario.” In The Monetization of Technical Data: Innovations from Industry and Research, 393–405. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-66509-1_23

- Song, A. 2019. “The Digital Entrepreneurial Ecosystem—A Critique and Reconfiguration.” Small Business Economics 53 (3): 569–590. doi:10.1007/s11187-019-00232-y.

- Stam, E. 2015. “Entrepreneurial Ecosystems and Regional Policy: A Sympathetic Critique.” European Planning Studies 23 (9): 1759–1769. doi:10.1080/09654313.2015.1061484.

- Steininger, D., M. Kathryn Brohman, and J. Block. 2022. “Digital Entrepreneurship: What is new if Anything?” Business & Information Systems Engineering 64 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1007/s12599-021-00741-9.

- Sun, Y., X. Zhou, A. Jeyaraj, R. Shang, and F. Hu. 2019. “The Impact of Enterprise Social Media Platforms on Knowledge Sharing: An Affordance Lens Perspective.” Journal of Enterprise Information Management. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEIM-10-2018-0232

- Sussan, F., and Z. Acs. 2017. “The Digital Entrepreneurial Ecosystem.” Small Business Economics 49 (1): 55–73. doi:10.1007/s11187-017-9867-5.

- Szerb, L., Z. Ács, and E. Autio. 2014. Entrepreneurship Measure and Entrepreneurship Policy in the European Union: The Global Entrepreneurship Index Perspective Entrepreneurial Ecosystems in Developing Countries View project Entrepreneurship, Technology, Industrialisation, and Sustainable Development View project Entrepreneurship measure and entrepreneurship policy in the European Union: The Global Entrepreneurship Index perspective. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/282133745.

- Szerb, L., E. Komlosi, Z. Acs, E. Lafuente, and A. Song. 2022. The Digital Platform Economy Index 2020. New York: Springer.

- Szerb, L., E. Lafuente, G. Márkus, and Z. Acs. 2020. Global Entrepreneurship Index 2019.

- Tansley, A. 1935. “The use and Abuse of Vegetational Concepts and Terms.” Ecology 16 (3): 284–307. doi:10.2307/1930070.

- Tapscott, D., and A. Williams. 2008. Wikinomics: How Mass Collaboration Changes Everything. New York: Penguin.

- Teece, D. 2018. “Profiting from Innovation in the Digital Economy: Enabling Technologies, Standards, and Licensing Models in the Wireless World.” Research Policy 47 (8): 1367–1387. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2017.01.015.

- Torres, P., and P. Godinho. 2022. “Levels of Necessity of Entrepreneurial Ecosystems Elements.” Small Business Economics 59 (1): 29–45. doi:10.1007/s11187-021-00515-3.

- Trabucchi, D., and T. Buganza. 2020. “Fostering Digital Platform Innovation: From two to Multi-Sided Platforms.” Creativity and Innovation Management 29 (2): 345–358. doi:10.1111/caim.12320.

- Trabucchi, D., and T. Buganza. 2021. “Entrepreneurial Dynamics in two-Sided Platforms: The Influence of Sides in the Case of Friendz.” International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research 28 (5): 1184–1205. doi:10.1108/IJEBR-01-2021-0076.

- Trabucchi, D., and T. Buganza. 2022. “Landlords with no Lands: A Systematic Literature Review on Hybrid Multi-Sided Platforms and Platform Thinking.” European Journal of Innovation Management 25 (6): 64–96. doi:10.1108/EJIM-11-2020-0467.

- Vergne, J. 2020. “Decentralized vs. Distributed Organization: Blockchain, Machine Learning and the Future of the Digital Platform.” Organization Theory 1 (4). https://doi.org/10.1177/2631787720977052

- Wallbach, S., K. Coleman, R. Elbert, and A. Benlian. 2019. “Multi-Sided Platform Diffusion in Competitive B2B Networks: Inhibiting Factors and Their Impact on Network Effects.” Electronic Markets 29: 693–710. doi:10.1007/s12525-019-00382-7.

- Weill, P., and S. Woerner. 2015. “Thriving in an Increasingly Digital Ecosystem.” MIT Sloan Management Review 56 (4): 27. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/thriving-increasingly-digital-ecosystem/docview/1694712973/se-2?accountid=16746

- Williams, L. 2021. “Concepts of Digital Economy and Industry 4.0 in Intelligent and Information Systems.” International Journal of Intelligent Networks 2: 122–129. doi:10.1016/j.ijin.2021.09.002.

- Xu, Z., and S. Dobson. 2019. “Challenges of Building Entrepreneurial Ecosystems in Peripheral Places.” Journal of Entrepreneurship and Public Policy. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEPP-03-2019-0023

- Zhai, Y., K. Yang, L. Chen, H. Lin, M. Yu, and R. Jin. 2023. “Digital Entrepreneurship: Global Maps and Trends of Research.” Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing 38 (3): 637–655. doi:10.1108/JBIM-05-2021-0244.