ABSTRACT

The growing process of metropolization has revealed its flip side in the last decade in the form of increasing social problems in peripheral regions. Through a comparative study of two structurally similar small cities in the Czech peripheral region, this paper explains different population trajectories as well as diverging competitive and foundational economies. Based on the original data collected during extensive fieldwork in the Moravian-Silesian Region, the paper uncovers a dualistic relationship between different types of human agency and its structural context as the key determinant, explaining the different developments. The agency of public providers (in contrast to private providers) in the foundational economy has buffered the impact of peripheralization on the well-being of residents, while the agency of companies in the competitive economy has had a major impact on path development and demographic change.

Introduction

In the last decade, both Europe and North America have seen a rise in radical political populism, which has drawn the attention of researchers, policymakers and media (Pike et al. Citation2023) to regions that, objectively or subjectively, can be described as left behind places. According to traditional regional typologies, left behind places include peripheral regions and regions specialized in traditional or declining industries (Florida Citation2021; MacKinnon et al. Citation2022; Rodríguez-Pose Citation2018). Although left behind places have been labelled ‘faddish terminology’ even by some of its proponents (Pike et al. Citation2023, 11), they consider the term valuable for redirecting one’s attention towards long-standing issues of inter-regional disparities and social problems in peripheries and their political implications in particular (ibid). At the same time, ‘research on peripheralization rarely considers the subjective perceptions … , … the agency of the residents … [and] the effects of living in opportunity-poor [peripheral] regions’ (Bernard et al. Citation2023, 107). We believe that by employing (1) peripheralization to explain the causes of the social problems in peripheries (Pike et al. Citation2023), (2) agency to highlight the ways regional actors perceive, cope with, or change structural conditions in peripheries (Kurikka et al. Citation2022; Nilsen, Grillitsch, and Hauge Citation2022) and (3) developmental framework for left behind places to emphasize the importance of perceptions and well-being of residents (MacKinnon et al. Citation2022), we can develop a novel perspective for tackling challenges in peripheries.

Amongst the most recent policy proposals aimed at development of the left behind places, MacKinnon et al. (Citation2022) have suggested shifting the focus of regional policy in peripheries from purely economic measures towards the so-called foundational economy (FE), incomes and the infrastructure for everyday civilized life. This is not to argue that the conventional economic policy should be rejected, or that the competitive economy (CE) could be jettisoned. Instead, as Hansen (Citation2022) argues, concentrating on the ‘mundane’ FE – as an alternative to a misplaced obsession with clusters of high-tech industries and R&D activities – could better help realize the key regional development objectives in peripheries (see also, Engelen et al. Citation2017). The FE directly addresses the issue of social polarization and inter-regional disparities, which may, in turn, mitigate the rise of radical populism (Dvořák, Zouhar, and Treib Citation2022).

Given that the potential for rising social problems and radical political populism is high in peripheries (Dvořák, Zouhar, and Treib Citation2022; MacKinnon et al. Citation2022) and the potential for economic growth and commercial innovation is relatively low (Farole et al. Citation2011; McCann and Ortega-Argilés Citation2015), a flourishing FE appears to be vital for development in the peripheries. In this context, the quality of public governance, and the capabilities of the public sector actors, in tandem with other stakeholders, ought to come into the spotlight. Thus, this paper examines the role of local actors and their agency in the development by presenting a comparative study of two small Czech cities that, despite the dominant neoliberal discourses in economic policy in Europe (Birch and Mykhnenko Citation2009) and ongoing strong peripheralization, demonstrated the possibilities (and limits) of FE-oriented development.

In particular, the aim is (i) to assess the agency of actors in coping with peripheralization and (ii) to scrutinize the dualistic relationship between different types of agency and its structural context. Drawing on Kühn (Citation2015), this paper answers two research questions:

How and why does agency in CE influence local path development and, in its turn, demographic trajectory?

How and why does agency in FE influence the well-being of local residents and, in its turn, the demographic trajectory?

Peripheralization

Spatial economic development, especially in the last two decades, in many high-income nations has been characterized by metropolization in the sense of the spatial concentration of economic activities (Krätke Citation2007), which draw on and strengthen the basic mechanisms of agglomeration economies (matching, learning and sharing, Puga Citation2010). The flip side of the same coin is then the process of peripheralization that exacerbates inter-regional disparities (Leibert and Golinski Citation2016). The concept of peripheralization views peripheries as a dynamic object produced and reproduced by the multi-scalar process of peripheralization (Lang Citation2012; Naumann and Reichert-Schick Citation2012). The intensity of peripheralization can be analytically captured through four basic dimensions: out-migration, decoupling, dependence and stigmatization (Kühn and Weck Citation2013). Moreover, a higher degree of peripherality (temporal, spatial, functional) increases the likelihood of negative effects of peripheralization (cf. Halás Citation2014), including impacts on path development (Nilsen, Grillitsch, and Hauge Citation2022) and well-being (Bernard et al. Citation2023).

Agency and opportunity space

Competitive economy

From the above description, it would seem that the process of peripheralization is purely structural and beyond the control of localities. However, recent research on peripheries points to the fact that employment growth cannot be solely explained through quantifiable structural preconditions alone, without considering the role played by the agency of local and regional actors (Grillitsch et al. Citation2022; Kurikka and Grillitsch Citation2021) and cultural and political determinants (Rekers and Stihl Citation2021). Human agency can be defined as ‘intentional, purposeful, and meaningful actions that are directed towards creating a change to the economy, institutions, and places’ (Grillitsch and Sotarauta Citation2020, 709). This implies that actors have the causal power to influence social structures, and although the relationship is dualistic, and structures also influence agency (Grillitsch et al. Citation2022), actors in peripheries are not predetermined by structures.

Depending on the depth of change and attitude, a distinction can be made between transformative and maintenance agency. The latter consists mainly of incremental changes to improve efficiency in existing industries and appears to be an adaptation-enhancing mechanism (Kurikka and Grillitsch Citation2021). In this sense, adaptation leads to increased specialization, favouring innovations that reproduce pre-existing structures (Grabher Citation1994), thus reinforcing the continuity of the path over its change (Martin Citation2010). By contrast, transformative agency focuses on proactively contributing to a fundamental change in the development path (Jolly, Grillitsch, and Hansen. Citation2020) with a lower degree of overlap and relatedness with existing structures and activities (Pike, Dawley, and Tomaney Citation2010). The transformative agency is further divided by Grillitsch and Sotarauta (Citation2020) into three types. First, institutional entrepreneurship focuses on changing the setting of institutions or creating new institutions. The object of change can be both formal (organizations, rules) and informal (trust, patriotism) institutions (Rekers and Stihl Citation2021). Second, innovative entrepreneurship focuses on changing the programme of entrepreneurship, typically by developing new products through the recombination of resources and knowledge. Third, place-based leadership focuses on change in a territory through cooperation with actors in the territory. It typically involves networking, where the leader must seek out and mobilize actors, find a common goal, and coordinate their activities. Thus, types of transformative agency are differentiated by the object the actors focus on, not by the area the actor comes from (Grillitsch and Sotarauta Citation2020); actors can engage in all types of agency, and one type can transition into another (Grillitsch et al. Citation2022).

The interaction between agency and structures is mediated by the opportunity space, which can be described as a specific context that is used by actors for agency or, acts as a barrier. The opportunity space encompasses the historical context (global level of knowledge and institutions), the region (economic specialization, educational and research institutions), and the actor (capabilities, resources) (Grillitsch and Sotarauta Citation2020). In peripheral regions, there are fewer actors compared to metropolitan regions, these actors have fewer resources, and their knowledge, and capabilities tend to be lower (cf. Gao et al. Citation2022; Kurikka et al. Citation2022; Nilsen, Grillitsch, and Hauge Citation2022). Narrower opportunity space in peripheries calls for a combination of maintenance agency, to keep the residents in place, while opening up the opportunity space for transformative agency in the long run (Kurikka and Grillitsch Citation2021; Rekers and Stihl Citation2021).

Foundational economy

The FE can be defined as services (e.g. healthcare, education, elder care) and infrastructures (utilities) that are essential for the fulfillment of basic human needs (Calafati et al. Citation2019). According to Hansen (Citation2022, 1034), FE ‘approach argues that economic development should directly aim to raise social standards and increase local accountability of economic actors’. A measure of the functionality of the FE is the availability and affordability of public goods of decent quality, to ensure well-being (Engelen et al. Citation2017). Proponents of the FE draw on the capability approach to well-being (Sayer Citation2019), arguing that FE generates capabilities that enable achieving valuable functionings (states of body and mind), hence individual well-being (Sen Citation1993). According to Engelen et al. (Citation2017), the FE occupies around 40% of employment in cities, and its output is used by residents with different income levels, creating the basis for stability of the city. The collective consumption of public services facilitates the reproduction of labour power, crucial for the CE (Saunders Citation1986) since it enhances labour productivity (Hicks and Streeten Citation1979). In the opposite direction of causality, employment (not only) in the CE also provides the population with income, which is one of the capabilities enabling achieving well-being (Sen Citation1993). However, almost any city struggles with FE unaffordability, a lack of resources to provide FE (Engelen et al. Citation2017), and needs to respond proactively to changing conditions and needs. For this reason, the agency of providers is crucial (Hansen Citation2022).

Now we point out some differences and limitations of our application of agency. Indeed, as proponents of the FE argue, the problem with the privatization of public services is not private actors in the role of providers but the importation of unsuitable business models, like the overemphasis on investment returns (Calafati et al. Citation2019), short-termism and market-based pricing. In contrast, public institutions in FE have traditionally been oriented towards the creation of public values (Lindholst Citation2021). For the purpose of examining agency in the FE, we will assume that transformative agency is intended to proactively change availability, affordability and quality of services (see Bernard et al. Citation2023). Alternatively, the maintenance agency, reactive or defensive in attitude, is intended to preserve the current FE and the resulting fulfilment of needs and level of well-being. Specifically, maintenance agency may focus on investment in infrastructure, but so does transformative agency, except that the investment fundamentally changes how it is used. We apply the transformative agency typology with one modification. Innovative entrepreneurship can be identified in the studied cases in the CE as well as in FE, but different normative frameworks are applied in these sectors (e.g. Froud et al. Citation2020). Thus, it is necessary for the sake of clarity to distinguish innovative entrepreneurship according to which sector we are writing about. Regardless of whether innovative entrepreneurship is pursued by a public or private actor, we will refer to this type of agency as public innovative entrepreneurship in FE and with no change in CE.

The FE is, compared to CE, a stable sector in terms of supply and demand, whose measure is not growth but rather the satisfactory fulfilment of local needs (Nygaard and Hansen Citation2020). Moreover, in the context of peripheralization, which often manifests itself by a lack of financial resources (Hansen Citation2022) and depopulation, actors of transformative agency aimed at increasing availability of services must keep in mind the economic sustainability of operation (Slach et al. Citation2019). If basic human needs, such as education and healthcare, are not met in a city, the city loses its capacity for social reproduction, the opportunity space is further narrowed, and transformative agency becomes increasingly difficult to achieve (cf. Kurikka and Grillitsch Citation2021). The importance of maintenance agency cannot be understated for consumption in many FE areas cannot be postponed (e.g. healthcare) (Engelen et al. Citation2017; Martynovich, Hansen, and Lundquist Citation2022). At the same time, transformative agency, underpinned by different intentions, is also exhibited within the FE. For example, public innovative entrepreneurship in the form of technological innovation may increase service quality and efficiency (Hansen Citation2022). Institutional entrepreneurship in the form of introducing new organizational forms such as privatization or transfer to municipal provisioning may promote quality and lower service prices (Wollmann Citation2014). Place-based leadership in the form of cooperation in the provisioning between several organizations may increase efficiency and/or the availability of services (Benito et al. Citation2015). As for the opportunity space in FE, Engelen et al. (Citation2017, 417) argued it is dependent on the availability of land, urban tax revenues and the arrangements for the provision of social services. Thus, we have identified preconditions in FE for the emergence of both maintenance and transformative agency, but which type will be predominant, and what outcomes it yields in well-being development, is open for investigation.

Data and methods

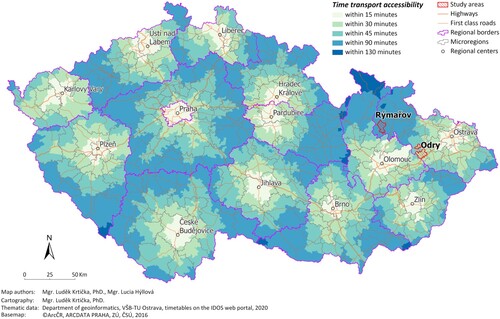

In this study, using agency theory, we investigate why structurally similar cities evolved differently in their demographic trajectories, CE and FE. Specifically, we assume the structural context enables or limits agency in the form of opportunity space, while the events and processes, such as transformation and different dimensions of peripheralization, change the structural context, which may, apart from above, also trigger or focus agency. The outcomes of these interactions are assessed through path development for CE and well-being development for FE. As the key performance indicator, we use demographic development. In particular, total population growth and net migration are indicative of the degree of peripheralization (cf. Dvořák, Zouhar, and Treib Citation2022) and of the success by the local CE and FE sectors (Nygaard and Hansen Citation2020). For the selection of cases, we used Mill's method of difference in developing the ‘most similar systems design’ of comparative research (Della Porta and Keating Citation2008; Ragin Citation2014). The selected cities of Odry and Rýmařov are located in the Moravian-Silesian region (MSR) of Czechia, an old industrial region (Ženka et al. Citation2019), while the cities themselves are part of peripheral microregions (Ženka, Slach, and Pavlík Citation2017; see ). In terms of economic structure at the beginning of the studied period, both cities showed a strong specialization in historically established low-tech manufacturing industries (Vaishar, Šťastná, and Zapletalová Citation2022; Ženka et al. Citation2015). Given that agency needs to be studied in the long term (Grillitsch, Rekers, and Sotarauta Citation2021), this study focused on the last three decades of development, choosing 1989 as the beginning, when the transformation of state socialism into capitalism began (Drahokoupil Citation2007), which fundamentally changed the context in which actors act, the composition of actors and the logic of their actions (Sýkora Citation2009).

Figure 1. Transport accessibility from municipalities to regional centres by private car transport in 2020.

Source: authors’ compilation.

The data collection phase proceeded from exploratory desktop research to uncover events, factors, and identify relevant local actors as potential explanatory variables, to semi-structured interviews (Grillitsch, Rekers, and Sotarauta Citation2021). The list of interviewees was confirmed, following several iterations of desktop research (annual reports, strategic documents, etc.). To triangulate the respondents’ accounts, between 2020 and 2022, we carried out 19 in-depth interviews (50–150 min) with local stakeholders, including top representatives, officials, and managers of local and regional governments, local public organizations and enterprises. The selection of respondents and the questions were chosen to obtain comprehensive information about their actions and to reveal any inconsistencies in the statements. The interviews focused on the actors’ motivations, what influenced the focus of their actions, barriers and opportunities for action, and the impacts (intended and unintended) of their actions. Additionally, the interviewees were asked about the perception of changes in well-being in the city in general.

Context of peripheralization in the studied cases

At the beginning of the transformation, the urban system of Czechia, and most of the post-socialist countries, was characterized by a low degree of metropolization (Musil Citation1993; Mykhnenko and Turok Citation2008). Since 1989, it has become the main driver of spatial polarization in Czechia (Hampl and Marada Citation2016). The peripheralization has affected mainly rural peripheral regions (Bernard and Šimon Citation2017), small cities in peripheral regions (Mulíček and Malý Citation2019) and old industrial regions (Šimon Citation2017), accompanied by growing support for radical populist parties (Dvořák, Zouhar, and Treib Citation2022). The process of peripheralization can be identified in all four dimensions in the study region. In the MSR, the peripheralization has manifested itself in a steady depopulation, with the main out-migration flows going to the Capital Prague Metropolitan Region. In real terms, GDP is decoupling from the main metropolitan areas, and a significant part of the production is controlled by multinational corporations (MNCs), with some parts of MSR exhibiting features of the branch plant syndrome (Ženka et al. Citation2019). The image of MSR has a long-term unfavourable character (Blažek and Bečicová Citation2014).

Sub-regionally, the distance from Odry and Rýmařov to the regional centre (Ostrava) plays a significant role. Odry benefits from a more advantageous location, further strengthened by its connection to the highway. The peripheral location of Rýmařov and the lack of transport connections contribute to the higher commuting time to Ostrava ().

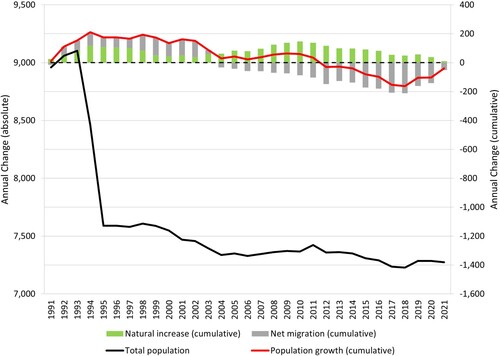

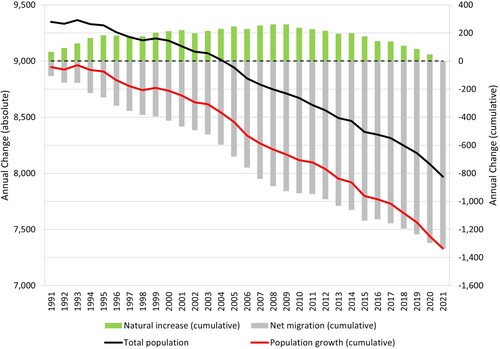

In the period 1991–2021, the population development in Odry showed a steady slight decline (), while in Rýmařov, the decline was more pronounced (). Also, the natural decline and the negative net migration rate testified to a more intensive peripheralization in Rýmařov. In both cities, the most numerous group of out-migrants was the productive age group 14–64, headed for metropolitan centres. In the 65 + category, Odry recorded significant arrivals from Ostrava, leading to a trend of double ageing. Rýmařov, in the last decade, has seen a slight increase in in-migrants from neighbouring municipalities and villages in the hinterland of regional centres (Olomouc, Ostrava).

Results

Now the results of the most significant instances of agency will be presented. The overall summary for all identified instances of agency in CE and selected FE areas is given in the following section.

Odry: competitive economy

The history of industrial production in Odry dates back to the nineteenth century when the main industry was textile production, which gradually morphed into rubber textiles, before diversifying into plastics after the arrival of Optimit company (Hubáček Citation2017). In terms of organization, Optimit had its own headquarters in Odry, including development department. At the beginning of the transformation, Odry represented a (one) company town, with Optimit exhibiting typical features of socialist production units, including low labour productivity and product quality (Clark and Soulsby Citation1999). The post-socialist restructuring of the company brought a reduction in employment of more than 50%, a narrowing of the product portfolio, and a change in customer markets (around 50% export). The restructuring also brought innovative entrepreneurship, with some of the former Optimit employees seizing the opportunity space and using their technological knowledge to establish spin-offs. In 1998, Optimit was acquired by an MNC: production has become almost fully de-localized. This is also linked to the departure of local workers who are dissatisfied with working conditions. The process of internationalization has also affected smaller companies that have been taken over by MNCs, further supported by the creation of a new industrial zone. Despite related diversification, the established development path (rubber/plastic) generated by the end of the study period around 85% of jobs in manufacturing. In sum, the agency was transformative in the 1990s, but later maintenance prevailed, corresponding to a greater dependence on extra-local decision-making. On the other hand, the loss of CE dynamism opened up space for public sector agency.

Odry: foundational economy

Since the 1990s, the city has engaged in institutional entrepreneurship, privatizing publicly owned real estate (the city now owns only 250 apartments). In recent years, the city management and a local entrepreneur have offered plots of land ready for the construction of family houses. However, given that the good quality land has been privatized, this public innovative entrepreneurship has been pushed to land burdened by environmental hazards, leading to delays in implementation. The city's utilities (water and sewerage systems) were also part of the privatization and now the municipality is forced to invest in constructing and maintaining these infrastructures 30% of its budget.

Optimit has historically supported cultural and social life, but this activity was curtailed during the restructuring in the 1990s. With the city lacking funds, a local entrepreneur has come forward to fill this gap by establishing formal institutions (historical association, museum). Over time, other residents and institutions have got involved, whereby the initially modest activities evolved into a place-based leadership, promoting local identity. The city’s difficult circumstances have represented an opportunity space for the engagement of actors: one’s personal interest in the history has propelled this transformative agency in the first place. Gradually, the institutional entrepreneurship could grow, thanks to a combination of business funding, the ability to administer public grant applications, cooperation with public institutions and support from similarly minded residents.

In 1992 during the restructuring of the regional healthcare system, the city management decided to provide healthcare in Odry through a municipal corporation, whereas there was (compared to Rýmařov) no pressure for privatization from the Ministry of Health due to less healthcare provision on the microregional level. Although the hospital is owned by the city, the management of the hospital has long been excluded from the decision-making about the allocation of city (and regional-level) public funds, forcing the hospital to be financially independent. At the same time, the hospital has faced a shortage of physicians and, therefore, in cooperation with the city, offers city apartments, a recruitment allowance, etc. Despite these activities, two-thirds of the physicians commute to Odry from Ostrava or the microregional centre. The low attractivity of Odry for physicians stems partly from their preference to live in family houses, unavailable due to a shortage of suitable land. Thus, the unfavourable structural conditions and the decisions taken at the beginning of transformation have forced the local actors towards maintenance rather than transformative agency.

Rýmařov: competitive economy

Until the twentieth century, Rýmařov retained its specialization in textiles and the production of wooden prefabricated houses, with the two largest companies in these sectors taking the form of branch plants (Chalupová Citation2009; Šprincová Citation1962). With the advent of capitalism, textile production has been marginalized, whereas the production of houses has been able to adapt. The economic structure after deindustrialization is highly diversified and shows relatively low unemployment. However, it brought certain dependence on the tourism sector (Ženka and Slach Citation2018). Some repurposing of the industrial legacy assets of textile factory have resulted in a creation of an exhibition on textile production; an attractive cultural offering was thus created, seeding potentially a path development in the tourism industry (cf. Ma and Hassink Citation2013).

Rýmařov: foundational economy

In the 1990s, unlike in Odry, the city management decided to keep the properties in municipal ownership. The city thus became the owner of 1250 apartments (40% of the total) and a large part of the land, engaging in institutional entrepreneurship through the establishment of a municipal corporation. The corporation’s profit is reinvested almost entirely into maintenance and new developments. As out-of-region clients buy seniors’ properties and transform them into second homes, the city then offers seniors smaller apartments with available care services and constructs homes for the elderly. Municipal land is then being prepared for the construction of family houses engaging in public innovative entrepreneurship, making available housing for an emerging social group. On the other hand, private development of recreational facilities is regulated by the city to avoid disturbing the tranquillity of residents, and increasing costs for construction and maintenance of utilities. Unlike in Odry, Rýmařov municipality has maintained ownership of utilities (water supply, sewerage and heating plant), which, combined with its ownership of housing stock, enables it to influence housing prices.

In the early 1990s, the regional museum was established on the initiative of a local historian, teacher and city councillor. In cooperation with local public institutions it develops educational and cultural activities for different age groups. In 1989, a kunsthalle was created on the initiative of local artists, which exhibits both regional artists and artists of national importance. In these examples of public innovative entrepreneurship and place-based leadership, the social position and professional authority of key leaders represented an opportunity space that enabled them to gain support. In addition to the museum, the city also operates a library, where, due to its growing senior population, a third-age university has been established. Moreover, shared equipment was purchased for cultural events, which any local organization could access for a minimal maintenance fee. Local FE actors drew on long-term personal contacts and trust, with many instances of place-based leadership leading to economies of scale and affordable cultural events.

The scope of healthcare has been decreasing since the 1990s. The hospital faced pressure from the Ministry of Health to close in 1997 but was able to resist the closure as the result of the cooperation with the city management. Nonetheless, in 2005, the city was forced to find a funding solution and, in an exercise of institutional entrepreneurship, privatized the hospital in hope of maintenance of at least some healthcare. The threat to the hospital's operations was a shortage of physicians, which the hospital addressed by maintenance – for instance, offering interest-free loans for medical equipment, and, in cooperation with the city, offering housing. Although increasingly after privatization, the availability and quality of healthcare became a major political issue, the city management did not try to negotiate with the privatized hospital; an indication of a narrowed opportunity space to tackle negative outcomes of healthcare transformation.

Although elementary schools are suffering from declining pupil numbers, this phenomenon is dampened by commuting from nearby villages since the attractiveness of the schools is enhanced by city investments. Secondary education is provided by a grammar school, to which two vocational schools have been added due to the decreasing number of students. One of them was a private school linked to tourism, which closed down for financial reasons. It was taken over by the mentioned secondary school because it considered this to be its ‘social commitment to the students, needs and demand’ in the region (R14). While the emphasis on quality primary and secondary education may help to maintain student numbers, it also sends graduates to large cities, thus inadvertently intensifying out-migration. In most cases, they do not return because of the inadequate job opportunities. The situation is also illustrated by a course that the secondary school created tailored to one of the largest local industrial companies but subsequently did not open due to low student interest, even though students would have gotten jobs in the company.

Comparison of the cases

In this section, we answer the research questions, whereas the parts related to outcomes which agency yields in the development of demography will be tackled in the Conclusion.

How the change happened and why could it emerge?

In both cities and sectors, maintenance agency prevailed as a way of managing peripheralization, with transformative agency more often being only triggered by a critical rupture (compare and ). On the one hand, the transformation has ruptured the very basis of CE and FE across Eastern Europe and opened opportunity for a radically transformative agency. On the other hand, peripheralization has progressed slowly, was easier for actors to ignore, and motivated agency only after it crossed a certain threshold. Quite often, peripheralization was seen as a direct threat to the operations of actors, motivating defensive maintenance agency, and being rarely perceived as an opportunity for proactive transformative agency. All in all, continuity has prevailed over change, a fate familiar to other peripheral regions in Czechia and beyond.

Table 1. Transformative agency.

Table 2. Maintenance agency.

Within CE, the actors most often used their knowledge (agent-specific opportunity space) for agency, which they could apply due to a market opportunity (region-specific opportunity space). In FE, financial resources (external and internal) played the most important role in enabling or constraining agency (the region- and agent-specific opportunity spaces). Another crucial factor for coping with peripheralization was the unequal distribution of power, decision-making authority, and resources, with the national-level actors having the most. Moreover, peripheralization in the MSR has also been strengthened by the spatial and thematic investment priorities of the MSR government and the exclusion of local authorities from regional decision-making: whilst the cities demanded the FE support, the region promoted tourism. As a result, the cities had to rely on their own resources or apply for subsidies at the national level. However, within the subsidies framework, the opportunity space of cities remained narrow, frequently described by the interviewees as being ‘too big for a village, too small for a city’.

Now we turn to differences between the emergence of agency in the two cases. Given the higher intensity of peripheralization in Rýmařov, it is not surprizing that agency was more often induced by the peripheralization in both sectors. More specifically, in Odry, due to the market opening and presence of a development department in the dominant company, there was a spillover of knowledge into related sectors through innovative entrepreneurship. The companies in Rýmařov were dependent on external decision-making, which disabled innovative entrepreneurship. The second largest Rýmařov company, although still dependent on external knowledge through foreign-licensed design, was able to strengthen its decision-making independence, which enabled a relatively successful restructuring (maintenance). Nevertheless, the different level of dependence, hence peripherality, differentiated the opportunity space of companies. The critical rupture affected also the FE. Throughout the post-socialist space in the 1990s, the public sector was characterized by knowledge and financial deficiencies, neoliberal thinking, and a preference for private sector activities (Maier Citation1998). This, along with the peripheralization, constituted constraining opportunity space and might be added to the prevalence of maintenance. The most significant transformative agency occurred in housing, where Odry proceeded to privatize publicly owned real estate, matching the pattern at the national level (Sunega and Lux Citation2013). Institutional entrepreneurship stood out all the more in Rýmařov, where the management decided to retain real estate and utilities. Although both cities faced the same time-specific opportunity space, the differentiation was caused by the region-specific opportunity space, which resulted from the opportunity to rely on the CE after transformation, and the agent-specific opportunity space, consisting of the risk appetite of key public agents. Moreover, the management in Rýmařov saw housing as a tool to keep residents in the city, strengthened by the fact that 80% of local government revenue in Czechia comes from state-redistributed revenue from shared taxes, which is largely calculated from the number of residents (Zhou, Koutský, and Hollander Citation2022).

What were the outcomes of agency in CE and FE?

The impact of agency on the path development in the CE of the two cities has been profound. By deploying maintenance during the critical rupture, 50% of jobs were retained in the dominant company in Odry, with 35% of them being restored in spin-offs and 15% due to the arrival of MNCs. In Rýmařov, the dominant company retained 2% of its employees, while the second largest company retained 50% of its employees. Thus, the industrial labour market in Rýmařov became dependent on commuting to regional companies, whereas companies in Odry had to import workers from the region and even from abroad. The second maintenance outcome was an increase in international competitiveness within the established path, manifested through the market share increase and attractiveness for MNCs. In Odry, the dominant company, which was taken over by an MNC, demonstrated competitiveness in the global market, while the largest company in Rýmařov was confined to the European market. There was also a difference in the success of maintenance in the form of establishing industrial zones, where the labour market (and domestic companies) in Odry were attractive under the established path, while in Rýmařov, the industrial zone was long empty and eventually occupied by industries unrelated to the previous path. However, these examples of maintenance increased economic dependence, hence peripheralization. Due to innovative entrepreneurship, there was related diversification and new growth in Odry. Rýmařov experienced small-scale innovative entrepreneurship, which led to related diversification in tourism. Although the number of tourists in Rýmařov increased, it was mostly the outcome of public innovative entrepreneurship (see bellow) and natural attractiveness. However, tourists were more beneficial to businesses than the city and residents, which was also matched by the somewhat reserved attitude of the city management towards tourism. In contrast, Odry was not considered attractive for tourists (Odry Citation2021). In sum, the near absence of innovative entrepreneurship in Rýmařov’s industrial specialization led to path-exhaustion and unrelated diversification through growing shares of public and commercial services. The different growth potentials of the rubber/plastic and textile sectors also played an important role.

Institutional entrepreneurship within the FE across the two cities has primarily involved the choice between privatization and public provision. In many instances, the perception by residents of availability, affordability and quality of public services in the FE areas of healthcare, housing, utilities, culture and education appear to have worsen post-privatization. Municipal ownership, for example, in Odry’s healthcare sector was said to have a more positive outcome than in Rýmařov, which privatized the service. It also resulted in greater independence of decision-making at the local level in Odry and vice versa. According to resident surveys, the quality and availability of healthcare were rated as the most negative aspect of well-being in Rýmařov (Rýmařov Citation2020), while in Odry, at least half of the residents were satisfied (Odry Citation2021). The poorer results of the privatized hospital may have been due to excessive efforts in making a profit.

A similar outcome can also be reported in other major FE area. In Odry, where housing was privatized, its availability and affordability, ranked as the second lowest aspect of well-being, leading to out-migration of younger residents (Odry Citation2021), hindering in-migration of industrial workers, physicians, families and the elderly, which were, paradoxically the groups that city management was trying to attract. By contrast, in Rýmařov, where real estate was transferred to the municipality, housing has not become a problem (Rýmařov Citation2020). Moreover, Rýmařov has recorded in-migration from within the MSR and beyond. The interviewees have confirmed that in the 1990s, Rýmařov was not an attractive place, but has become ‘more sophisticated’, with amenities and better-quality infrastructure. The local authority respondents believe ‘they have a huge leverage on how the city looks’ by keeping the housing in municipal ownership. Having the land available for new house building, Rýmařov was also able to attract new residents, whilst in Odry, the privatization had a negative impact on migration, restricting the city’s opportunity space to cope with peripheralization.

Overall, public cultural institutions in Rýmařov focused transformative agency on meeting the changing needs of the diverse population, the focus of private organizations (dominating culture in Odry) reflected the hobbies of their (older) founders without much regard for the needs of other groups. Whilst the lack of cultural offerings for the youth has been a frequent complaint in both cities, in Odry the issue was ranked as the third most negative aspect of well-being (Odry Citation2021; Rýmařov Citation2020). While the public schools in Rýmařov, through a combination of transformative and maintenance agency, supplied graduates to the regional labour market according to demand, despite declining student numbers, the private school ceased operations when student numbers (and profitability) declined.

In sum, public institutions, dominating FE in Rýmařov, better fulfilled local needs, thus generating more well-being than private organizations, dominating in Odry.

Conclusion

We have found a clear pattern of agency outcomes in studied cases: Odry was more successful in terms of its CE’s path development, but performed poorly in the FE, whereas Rýmařov’s FE generated much better well-being outcomes, but its CE did not perform as well. What, then, was the role of agency – in its different forms – in coping with peripheralization? Given the same size, geographical proximity, and similar industrial legacies of the two cities, it may be apparent that the agency of actors operating in the CE has had more impact on the demographic trajectory than the agency in the FE. This conclusion is supported by previous research in Czech microregions that found the strength of CE (entrepreneurial activity, job opportunities) and the major capability for well-being derived from employment in the form of income to be associated with out-migration (Frantál et al. Citation2022).

Nonetheless, based on the data presented above, we believe that, holding other things constant, the successful functioning of the CE is conditioned by the FE, in the long-run, as it ensures social reproduction. If Rýmařov’s FE were to perform poorly, it would have engendered even faster depopulation, whereas if Odry had a more successful agency within FE, the city could have turned its population trajectory to growth much faster. Indeed, most recently, Odry’s city managers, who disregarded the FE for over two decades, have come to realize that an underdeveloped FE severely hinders local development overall, including further expansion of its CE. Furthermore, in a market-based economy, local public actors have a limited opportunity space for agency in the CE, other than indirectly influencing it through their FE activities, making agency in FE (probably) the only available development option for public authorities. Therefore, we conclude that exercising human agency in the FE is necessary, but not sufficient leverage to steer small cities away from (further) peripheralization and (potential) depopulation.

This paper’s findings have clear research and policy implications. Despite frequent appeals to agency in evolutionary economic geography, not enough attention is being paid to the temporal dimension and the relationship between transformative and maintenance agency. This study has highlighted the vital importance of maintenance within the FE, which, when exercised within the CE is typically interpreted as real handicap. The contribution of the paper is also in the, not yet performed, application of the three types of transformative agency to the FE (for certain exception, see Wirth et al. Citation2023), highlighting the need for following a long-term vision and ensuring adaptability also in the FE, although, compared to CE, FE is more stable. Methodically, we have shown the importance of not excluding unintended and unwanted outcomes of agency from the analysis.

Since Eastern European peripheries are competitive in medium low-tech manufacturing (cf. Vaishar, Šťastná, and Zapletalová Citation2022) with a strong dependency on external decision-making of dominating MNCs, the opportunity space for innovative entrepreneurship is limited, contrasting with a higher incidence of transformative agency in FE, fostered by a more highly skilled workforce (Froud et al. Citation2020; Nilsen, Grillitsch, and Hauge Citation2022). Thus, although seldom considered in the FE literature, improving residential attractiveness and well-being for FE employees is vital. Moreover, the development of the silver economy has a significant growth potential in small peripheral cities (see Steinführer and Grossmann Citation2021), and local authorities which retain the decision-making power over, and ownership of the real estate are better conditioned to benefit from this opportunity. Although, as evidenced by demographic trajectories of our cases, the proper working of CE cannot be fully substituted by FE, agents of place-based leadership can strengthen the impact of FE in coping with peripheralization by coordinating between CE and FE, and also within the FE. Whilst the FE generates the potential for ‘shrinking with dignity’ in peripheries and small cities (Martynovich, Hansen, and Lundquist Citation2022, 21; Vaishar, Šťastná, and Zapletalová Citation2022), the austerity measures may limit this possibility, as FE, which is more prominent in peripheries, is partly dependent on transfers (Martin Citation2012).

What is also clear is that privatization in the FE may deepen peripheralization, narrow the opportunity space for action and reduce the level of well-being locally. Furthermore, the public sector FE may not only provide services of decent quality in adequate quantity and at an affordable price but also actively respond to the needs of different social groups through its transformative agency, while coping with peripheralization via maintenance agency. Hence, the arguments about inefficiency, rigidity, the lack of innovation in the public sector, and in favour of privatization may not always reflect the actual performance of providers in the FE. With a weaker supply-side competition in the FE in comparison to the CE generally (De Boeck et al. Citation2019), and especially in a small-size market on the periphery, privatization could result in monopoly, with a detrimental impact on availability, affordability and quality of FE services (Benito et al. Citation2015). If the private provider is not bound by a social licence with explicit social obligations (Calafati et al. Citation2019), the adverse impact of profit-seeking on well-being of local residents cannot be fully ruled-out. Moreover, even the presence of a growing industry or a large company does not guarantee positive outcomes for the overall city development. Since not only the quantity of jobs, but also the working conditions affects out-migration, we would appreciate the research into the agency in the CE to cover the impact on the well-being of local residents. This study has concentrated on local-level conditions, while relations of local actors with the central state, particularly important for agency in FE, were considered only briefly; these deserve more attention in future research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Benito, B., M. Guillamón, and F. Bastida. 2015. “Public Versus Private in Municipal Services Management.” Lex Localis – Journal of Local Self-Government 13 (4): 995–1018. doi:10.4335/13.3.995-1018(2015).

- Bernard, J., A. Steinführer, A. Klärner, and S. Keim-Klärner. 2023. “Regional Opportunity Structures: A Research Agenda to Link Spatial and Social Inequalities in Rural Areas.” Progress in Human Geography 47 (1): 103–123. doi:10.1177/03091325221139980.

- Bernard, J., and M. Šimon. 2017. “Vnitřní Periferie v Česku: Multidimenzionalita Sociálního Vyloučení ve Venkovských Oblastech.” Sociologický časopis 53 (1): 3–28.

- Birch, K., and V. Mykhnenko. 2009. “Varieties of Neoliberalism? Restructuring in Large Industrially Dependent Regions across Western and Eastern Europe.” Journal of Economic Geography 9 (3): 355–380. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbn058.

- Blažek, J., and I. Bečicová. 2014. “Moravian-Silesian Region (Subregion Nuts 3) as an Example of a Successful Transformation–Case Study Report.” GRINCOH Working Paper Series 6 (3): 1–3.

- Calafati, L., J. Froud, S. Johal, and K. Williams. 2019. “Building Foundational Britain: From Paradigm Shift to New Political Practice?” Renewal: A Journal of Labour Politics 27 (2): 13–23.

- Chalupová, Z. 2009. Čtyřicet let Domů z Rýmařova. Olomouc: RD Rýmařov.

- Clark, E., and A. Soulsby. 1999. “The Adoption of the Multi-Divisional Form in Large Czech Enterprises: The Role of Economic, Institutional and Strategic Factors.” Journal of Management Studies 36 (4): 535–559. doi:10.1111/1467-6486.00148.

- De Boeck, S., D. Bassens, and M. Ryckewaert. 2019. “Making Space for a More Foundational Economy: The Case of the Construction Sector in Brussels.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 105: 67–77. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.07.011.

- Della Porta, D., and M. Keating. 2008. Approaches and Methodologies in the Social Sciences: A Pluralist Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Drahokoupil, J. 2007. “Analysing the Capitalist State in Post-Socialism: Towards the Porterian Workfare Postnational Regime.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 31 (2): 401–424. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2007.00727.x.

- Dvořák, T., J. Zouhar, and O. Treib. 2022. “Regional Peripheralization as Contextual Source of Populist Attitudes in Germany and Czech Republic.” Political Studies, 1–22. doi:10.1177/00323217221091981.

- Engelen, E., J. Froud, C. Johal, A. Salento, and K. Williams. 2017. “The Grounded City: From Competitivity to the Foundational Economy.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 10: 407–423. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsx016.

- Farole, T., A. Rodríguez-Pose, and M. Storper. 2011. “Cohesion Policy in the European Union: Growth, Geography, Institutions.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 49 (5): 1089–1111. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5965.2010.02161.x.

- Florida, R. 2021. “Discontent and its Geographies.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 14 (3): 619–624. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsab014.

- Frantál, B., J. Frajer, S. Martinát, and L. Brisudová. 2022. “The Curse of Coal or Peripherality? Energy Transitions and the Socioeconomic Transformation of Czech Coal Mining and Post-Mining Regions.” Moravian Geographical Reports 30 (4): 237–256. doi:10.2478/mgr-2022-0016.

- Froud, J., C. Haslam, S. Johal, and K. Williams. 2020. “(How) Does Productivity Matter in the Foundational Economy?” Local Economy: The Journal of the Local Economy Policy Unit 35 (4): 316–336. doi:10.1177/0269094220956952.

- Gao, J., X. Hu, Y. Li, R. Zhuo, and Ch. Chen. 2022. “Entrepreneurial Agents, Asset Modification and New Path Development in Rural China: The Study of Gengche Model, Jiangsu Province.” Journal of Rural Studies 95: 482–494. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2022.09.030.

- Grabher, G. 1994. Lob der Verschwendung: Redundanz in der Regionalentwicklung; ein Sozioökonomisches Plädoyer. Berlin: Edition sigma.

- Grillitsch, M., B. Asheim, A. Isaksen, and H. Nielsen. 2022. “Advancing the Treatment of Human Agency in the Analysis of Regional Economic Development: Illustrated with Three Norwegian Cases.” Growth and Change 53 (1): 248–275. doi:10.1111/grow.12583.

- Grillitsch, M., J. Rekers, and M. Sotarauta. 2021. “Investigating Agency: Methodological and Empirical Challenges.” In Handbook on City and Regional Leadership, edited by M. Sotarauta, and A. Beer, 302–323. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Grillitsch, M., and M. Sotarauta. 2020. “Trinity of Change Agency, Regional Development Paths and Opportunity Spaces.” Progress in Human Geography 44 (4): 704–723. doi:10.1177/0309132519853870.

- Halás, M. 2014. “Modelling of Spatial Organization and the Dichotomy of Centre–Periphery.” Geografie 119 (4): 384–405. doi:10.37040/geografie2014119040384.

- Hampl, M., and M. Marada. 2016. “Metropolization and Regional Development in Czechia During the Transformation Period.” Geografie 121 (4): 566–590. doi:10.37040/geografie2016121040566.

- Hansen, T. 2022. “The Foundational Economy and Regional Development.” Regional Studies 56 (6): 1033–1042. doi:10.1080/00343404.2021.1939860.

- Hicks, N., and P. Streeten. 1979. “Indicators of Development: The Search for a Basic Needs Yardstick.” World Development 7: 567–580. doi:10.1016/0305-750X(79)90093-7.

- Hubáček, A. 2017. Optimit Odry. Příběh Továrny a Města. Odry: Muzeum Oderska.

- Jolly, S., M. Grillitsch, and T. Hansen. 2020. “Agency and Actors in Regional Industrial Path Development. A Framework and Longitudinal Analysis.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 111: 176–188. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.02.013.

- Krätke, S. 2007. “Metropolisation of the European Economic Territory as a Consequence of Increasing Specialisation of Urban Agglomerations in the Knowledge Economy.” European Planning Studies 15 (1): 1–27. doi:10.1080/09654310601016424.

- Kurikka, H., and M. Grillitsch. 2021. “Resilience in the Periphery: What an Agency Perspective Can Bring to the Table.” In Economic Resilience in Regions and Organisations, edited by R. Wink, 147–174. Wiesbaden: Springer.

- Kurikka, H., J. Kolehmainen, M. Sotarauta, H. Nielsen, and M. Nilsson. 2022. “Regional Opportunity Spaces – Observations from Nordic Regions.” Regional Studies: 1–13. doi:10.1080/00343404.2022.2107630.

- Kühn, M. 2015. “Peripheralization: Theoretical Concepts Explaining Socio-Spatial Inequalities.” European Planning Studies 23 (2): 367–378. doi:10.1080/09654313.2013.862518.

- Kühn, M., and S. Weck. 2013. “Peripherisierung–ein Erklärungsansatz zur Entstehung von Peripherien.” In Peripherisierung, Stigmatisierung, Abhängigkeit? edited by M. Bernt, and H. Liebmann, 24–46. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Lang, T. 2012. “Shrinkage, Metropolization and Peripheralization in East Germany.” European Planning Studies 20 (10): 1747–1754. doi:10.1080/09654313.2012.713336.

- Leibert, T., and S. Golinski. 2016. “Peripheralization: The Missing Link in Dealing with Demographic Change?” Comparative Population Studies 41 (3-4): 255–284. doi:10.12765/CPoS-2017-02en.

- Lindholst, A. 2021. “Addressing Public-Value Failure: Remunicipalization as Acts of Public Entrepreneurship.” Journal of Economic Policy Reform 24 (3): 380–397. doi:10.1080/17487870.2019.1671192.

- Ma, M., and R. Hassink. 2013. “An Evolutionary Perspective on Tourism Area Development.” Annals of Tourism Research 41: 89–109. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2012.12.004.

- MacKinnon, D., L. Kempton, P. O’Brien, E. Ormerod, A. Pike, and J. Tomaney. 2022. “Reframing Urban and Regional ‘Development’ for ‘Left Behind’ Places.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 15 (1): 39–56. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsab034.

- Maier, K. 1998. “Czech Planning in Transition: Assets and Deficiencies.” International Planning Studies 3 (3): 351–365. doi:10.1080/13563479808721719.

- Martin, R. 2010. “Roepke Lecture in Economic Geography-Rethinking Regional Path Dependence: Beyond Lock-in to Evolution.” Economic Geography 86 (1): 1–27. doi:10.1111/j.1944-8287.2009.01056.x.

- Martin, R. 2012. “Regional Economic Resilience, Hysteresis and Recessionary Shocks.” Journal of Economic Geography 12 (1): 1–32. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbr019.

- Martynovich, M., T. Hansen, and K. Lundquist. 2022. “Can Foundational Economy Save Regions in Crisis?” Journal of Economic Geography 23: 1–23. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbac027.

- McCann, P., and R. Ortega-Argilés. 2015. “Smart Specialization, Regional Growth and Applications to European Union Cohesion Policy.” Regional Studies 49 (8): 1291–1302. doi:10.1080/00343404.2013.799769.

- Mulíček, O., and J. Malý. 2019. “Moving Towards More Cohesive and Polycentric Spatial Patterns? Evidence from the Czech Republic.” Papers in Regional Science 98 (2): 1177–1194. doi:10.1111/pirs.12383.

- Musil, J. 1993. “Changing Urban Systems in Post-communist Societies in Central Europe: Analysis and Prediction.” Urban Studies 30 (6): 899–905. doi:10.1080/00420989320080841.

- Mykhnenko, V., and I. Turok. 2008. “East European Cities — Patterns of Growth and Decline, 1960–2005.” International Planning Studies 13 (4): 311–342. doi:10.1080/13563470802518958.

- Naumann, M., and A. Reichert-Schick. 2012. “Infrastrukturelle Peripherisierung: Das Beispiel Uecker-Randow (Deutschland).” disP – The Planning Review 48 (1): 27–45. doi:10.1080/02513625.2012.702961.

- Nilsen, T., M. Grillitsch, and A. Hauge. 2022. “Varieties of Periphery and Local Agency in Regional Development.” Regional Studies 57: 1–14. doi:10.1080/00343404.2022.2106364.

- Nygaard, B., and T. Hansen. 2020. “Local Development through the Foundational Economy? Priority-Setting in Danish Municipalities.” Local Economy: The Journal of the Local Economy Policy Unit 35 (8): 768–786. doi:10.1177/02690942211010380.

- Odry. 2021. Život ve městě Odry z pohledu občana: vyhodnocení dotazníkového šetření. Odry: The City of Odry.

- Pike, A., V. Béal, N. Cauchi-Duval, R. Franklin, N. Kinossian, T. Lang, T. Leibert, et al. 2023. “‘Left Behind Places’: A Geographical Etymology.” Regional Studies, 1–13. doi:10.1080/00343404.2023.2167972.

- Pike, A., S. Dawley, and J. Tomaney. 2010. “Resilience, Adaptation and Adaptability.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 3 (1): 59–70. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsq001.

- Puga, D. 2010. “The Magnitude and Causes of Agglomeration Economies.” Journal of Regional Science 50 (1): 203–219. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9787.2009.00657.x.

- Ragin, C. 2014. The Comparative Method. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Rekers, J., and L. Stihl. 2021. “One Crisis, one Region, two Municipalities: The Geography of Institutions and Change Agency in Regional Development Paths.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 124: 89–98. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.05.012.

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. 2018. “The Revenge of the Places That Don’t Matter (and What to Do about it).” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 11 (1): 189–209. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsx024.

- Rýmařov. 2020. Strategický plán rozvoje města Rýmařova do roku 2030. Rýmařov: The City of Rýmařov.

- Saunders, P. 1986. Social Theory and the Urban Question. London: Routledge.

- Sayer, A. 2019. “Moral Economy, the Foundational Economy and De-carbonisation.” Renewal: A Journal of Labour Politics 27 (2): 40–46.

- Sen, A. 1993. “Capability and Well-Being.” In The Quality of Life, edited by M. Nussbaum, and A. Sen, 41–71. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Slach, O., V. Bosák, L. Krtička, A. Nováček, and P. Rumpel. 2019. “Urban Shrinkage and Sustainability: Assessing the Nexus between Population Density, Urban Structures and Urban Sustainability.” Sustainability 11 (15): 4142. doi:10.3390/su11154142.

- Steinführer, A., and K. Grossmann. 2021. “Small Towns (Re)growing Old. Hidden Dynamics of Old-Age Migration in Shrinking Regions in Germany.” Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 103 (3): 176–195. doi:10.1080/04353684.2021.1944817.

- Sunega, P., and M. Lux. 2013. “Systémová Rizika na Trhu Bydlení v ČR.” E + M Ekonomie a Management 16 (4): 55–70.

- Sýkora, L. 2009. “Post-Socialist Cities.” In International Encyclopedia of Human Geography, edited by R. Kitchin, and N. Thrift, 387–395. Oxford: Elsevier.

- Šimon, M. 2017. “Multi-scalar Geographies of Polarisation and Peripheralisation: A Case Study of Czechia.” Bulletin of Geography. Socio-Economic Series 37: 125–137. doi:10.1515/bog-2017-0029.

- Šprincová, S. 1962. “Hospodářská Geografie Severní Moravy a Severozápadního Slezska.” Acta Universitatis Palackianae Olomucensis, Facultas Rerum Naturalium 14: 127–322.

- Vaishar, A., M. Šťastná, and J. Zapletalová. 2022. “Small Industrial Towns in Moravia: A Comparison of the Production and Post-Productive Eras.” European Planning Studies, 1–21. doi:10.1080/09654313.2022.2110377.

- Wirth, S., P. Tschumi, H. Mayer, and M. Bandi Tanner. 2023. “Change Agency in Social Innovation: An Analysis of Activities in Social Innovation Processes.” Regional Studies, Regional Science 10 (1): 33–51. doi:10.1080/21681376.2022.2157324.

- Wollmann, H. 2014. “Public Services in European Countries: Between Public/Municipal and Private Sector Provision – and Reverse?” In Fiscal Austerity and Innovation in Local Governance in Europe, edited by C. N. Silva, and J. Buček, 49–76. London: Routledge.

- Zhou, K., J. Koutský, and J. Hollander. 2022. “URBAN SHRINKAGE IN CHINA, THE USA AND THE CZECH REPUBLIC: A Comparative Multilevel Governance Perspective.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 46 (3): 480–496. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.13030.

- Ženka, J., J. Novotný, O. Slach, and V. Květoň. 2015. “Industrial Specialization and Economic Performance: A Case of Czech Microregions.” Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift – Norwegian Journal of Geography 69 (2): 67–79. doi:10.1080/00291951.2015.1009859.

- Ženka, J., and O. Slach. 2018. Rozmístění služeb v Česku. Ostrava: University of Ostrava.

- Ženka, J., O. Slach, and A. Pavlík. 2019. “Economic Resilience of Metropolitan, Old Industrial, and Rural Regions in Two Subsequent Recessionary Shocks.” European Planning Studies 27 (11): 2288–2311. doi:10.1080/09654313.2019.1638346.

- Ženka, J., O. Slach, and A. Sopkuliak. 2017. “Typology of Czech Non-metropolitan Regions Based on Their Principal Factors, Mechanisms and Actors of Development.” Geografie 122 (3): 281–309. doi:10.37040/geografie2017122030281.