ABSTRACT

The literature on spatial evolution has taken a high interest in structure-agency dynamics, but how long-term discourse interacts with these dynamics in shaping new paths still lacks a systematic understanding. To advance such an understanding, this article draws on the agency, structure, institutions and discourse (ASID) framework and refocuses it on spatial evolution. By doing so, the article aims at elucidating the discursive aspects of evolutionary spatial processes and highlights in particular the role of abstract macro-level discourses and concrete imaginaries as long-term discursive foundations of spatial evolution. In this way, discourse acts as a carrier of long-term historical roots and associations. By considering the historical rootedness of the discursive foundations of paths, the framework contributes to giving history a stronger role in evolutionary economic geography. We apply this analytical framework to wine tourism in Israel’s Negev and focus particularly on the historically rooted imaginaries that underpin the development of this path.

Introduction

As a ‘developmental’ stream of evolutionary economic geography (Martin and Sunley Citation2015), the literature on regional path development (Grillitsch, Asheim, and Trippl Citation2018; Martin and Sunley Citation2006; Tödtling and Trippl Citation2013) addresses the emergence and growth of new paths in regional economies. More recently, this literature has taken a high interest in the role of agency (e.g. Grillitsch and Sotarauta Citation2020; Isaksen et al. Citation2019; Jolly, Grillitsch, and Hansen Citation2020) in a specific case of the wider structure-agency debate in the social sciences (Archer Citation1982; Giddens Citation1984; Sewell Citation1992). At the same time, interest in other factors of spatial evolution such as assets (e.g. Trippl et al. Citation2020), structural and institutional conditions (e.g. Baumgartinger-Seiringer et al. Citation2022), and discursive elements such as expectations and imaginaries (e.g. Miörner Citation2022; Steen Citation2016) have surfaced. However, how different forms of agency interact with institutional, discursive and other structural conditions in shaping new paths still lacks a systematic understanding. In particular, apart from a few exceptional studies that address how agents make sense of the history and future (e.g. Kurikka et al. Citation2022; Steen Citation2016), the role of discourse in intertemporal agentic processes (Emirbayer and Mische Citation1998) in path development has not yet been systematically examined. We argue that the agency, structure, institutions and discourse (ASID) framework (Moulaert, Jessop, and Mehmood Citation2016) provides a useful analytical lens to examine these factors of regional path development and to reveal the interrelationships between them.

This article draws on recent tendencies in the path development literature that focus on the role of agency and institutions and aims at advancing the understanding of structure-agency dynamics in spatial evolution. By refocusing the ASID framework on questions of spatial evolution, the article proposes an analytical lens for focusing on the interrelationships between agency, structure, institutions and discourse in the emergence and growth of new paths. Specifically, drawing on this evolutionary ASID framework, the article aims at fostering our understanding of the discursive aspects of evolutionary spatial processes and highlights in particular the discursive foundations of paths. As these discursive foundations are historically rooted, we respond to recent calls in the paradigm of evolutionary economic geography (EEG) for giving history a stronger role (Henning Citation2019; Martin and Sunley Citation2022). Hence, the article aims to situate discourse along with agency, structure and institutions as a factor propelling regional path development and examines the role of long-term historical roots and associations of discourse. The article explores the following research questions: generally, how do agency, structure, institutions and discourse shape spatial evolution and specifically, how do agents employ historically rooted discourses to shape the development of a regional path?

The article starts by reviewing the literature on spatial evolution. Drawing on the generic ASID framework, a more specific evolutionary framework is proposed. The empirical part applies the framework to the case of wine tourism in Israel’s Negev desert and discusses the interrelations between the components of the framework. The final section discusses the results and draws conclusions.

Spatial evolution and its factors

Drawing on EEG (Boschma and Frenken Citation2006; Essletzbichler and Rigby Citation2007) with its fundamental idea of path dependence but conceptualizing a path as a contingent process (Martin Citation2010; Martin and Sunley Citation2006) under a ‘developmental’ approach (Martin and Sunley Citation2015), the literature on regional path development has led to a nuanced understanding of the positive or negative paths regional industries can pursue (Blažek et al. Citation2020; Grillitsch et al. Citation2018; Martin and Sunley Citation2006; Tödtling and Trippl Citation2013). By doing so, the path development literature has complemented the focus of EEG on path dependence with a path-as-process perspective (Martin Citation2010; Martin and Sunley Citation2006) that considers both radical change and gradual, developmental evolution (Benner Citation2023b; Martin Citation2012). However, the factors that propel these paths and their interrelationships are not fully understood so far.

Several factors have been identified in the more recent path development literature. In what can be understood as an expression of the long-standing structure-agency debate in the social sciences (Archer Citation1982; Giddens Citation1984; Sewell Citation1992), the role of agency has attracted particular attention (e.g. Isaksen et al. Citation2019; Jolly, Grillitsch, and Hansen Citation2020; Trippl et al. Citation2020). Agency in path development can instigate transformative change (Grillitsch and Sotarauta Citation2020) but also maintain existing structures (Henderson Citation2020; Jolly, Grillitsch, and Hansen Citation2020), and it takes place either at the firm level or at the system level agency (Benner Citation2023c; Hassink, Isaksen, and Trippl Citation2019; Isaksen et al. Citation2019). As a way of definition, ‘firm-level agency has its main field of influence within one firm or organization, while system-level agency exerts influences outside its institutional and organizational borders’ (Hassink, Isaksen, and Trippl Citation2019, 1638).

In a more structuralist sense, spatial evolution is shaped by institutions and their change (Benner Citation2022b; Zukauskaite, Trippl, and Plechero Citation2017). Institutions can be distinguished along their formal or informal nature (North Citation1990), and they can both enable and constrain action (Hodgson Citation2006). Stressing the informal aspects of institutions and their embodiment in practices, Bathelt and Glückler (Citation2014) understand them as ‘stable patterns of social practice based on mutual expectations’ (346).

The relevance of institutions for regional development is well established (Gertler Citation2010; Rodríguez-Pose Citation2013), but how they shape the evolution of regional economies is anything but clear (Bathelt and Glückler Citation2014; Rodríguez-Pose Citation2020). Here again, the role of agency is important, as approaches such as institutional entrepreneurship (Battilana, Leca, and Boxenbaum Citation2009; DiMaggio Citation1988) or institutional work (Lawrence and Suddaby Citation2006) highlight, thus again leading to the interactions between agency and (institutional) structure. Indeed, institutions can be understood as a specific sub-type of the structural conditions of a regional economy (Baumgartinger-Seiringer et al. Citation2022). Further structural conditions apart from institutions include, for example, natural resources, physical infrastructure, and the regional stock of knowledge and skills (Trippl et al. Citation2020).

However, the structural side of regional economic activity is not static but shaped by dynamics beyond the reach of regional agents (Moulaert, Jessop, and Mehmood Citation2016). These structural dynamics include, in particular, opportunities that agents can seize if and when they arise. Grillitsch and Sotarauta (Citation2020) conceptualize these dynamics as opportunity spaces, Benner (Citation2022a) understands transnational policy alignment as a peculiar case of a structural opportunity space for regional development, and Kurikka et al. (Citation2022) describe how agents perceive a structurally given region-specific opportunity space.

These opportunities are shaped not only by ‘material practices’ but also by ‘symbolic constructions’ (Friedland and Alford Citation1991, 248) and, hence, by elements of discourse. Accordingly, Beer, Barnes, and Horne (Citation2023) identify ‘discourse as a process and driver of change at critical junctures’ (987) and consider discourse as a cross-cutting dimension that structures opportunity spaces for change agency. Discourse can take different forms. In a more abstract sense, macro-cultural discourses (Lawrence and Phillips Citation2004) are relevant as the wider discursive arena in a society. By redrawing the shift from whaling to whale-watching, Lawrence and Phillips (Citation2004) provide a convincing account of how the macro-cultural shift from the frightening ‘Moby Dick’ to the sensitive ‘Free Willy’ affected this path. Similarly, Zerubavel (Citation2019) elaborately recounts how the role of the desert in Israeli popular imagination and culture evolved from a desolate ‘empty space’ (7) towards a diverse space rife with adventure, spirituality, and recreation.

Discourses affect different social levels and are (re)interpreted at each of them, including in processes of institutionalization (Zilber Citation2009). More specifically, agents operationalize abstract macro-cultural discourses in path development activities as concrete and intertemporal visions, narratives, or imaginaries (Beer, Barnes, and Horne Citation2023; Benner Citation2020, Citation2022a, Citation2023a; Binz and Gong Citation2022; Miörner Citation2022; Sotarauta Citation2018) that in turn shape agents’ expectations (Borup et al. Citation2006; Steen Citation2016). Imaginaries can be generically defined as ‘collectively available symbolic meanings and values’ (Van Lente Citation2021, 23). Addressing imaginaries in tourism, Salazar (Citation2012) proposes the more elaborate definition of ‘socially transmitted representational assemblages that interact with people’s personal imaginings and are used as meaning-making and world-shaping devices’ (864). Through narratives, visions, and expectations (Borup et al. Citation2006; Sotarauta Citation2018; Steen Citation2016), discourse helps agents exert intertemporal agency (Emirbayer and Mische Citation1998) and furnishes a lens to ‘see how the cumulative consequences of past actions constrain and limit future action’ (Martin and Sunley Citation2022, 77). Hence, discourse provides an important driver for the historical evolution of economic activity that Henning (Citation2019) as well as Martin and Sunley (Citation2022) place at the heart of EEG.

A specific ASID framework for spatial evolution

The various factors of regional path development discussed in the preceding section can be conceptualized along the ASID (agency, structure, institutions, discourse) framework proposed by Moulaert, Jessop, and Mehmood (Citation2016). This framework assumes that (multiscalar) ‘structure is (…) a product of path-dependent institutionalization and path-shaping (collective) agency’ while agency is ‘discursively and materially reproduced and transformed’ (Moulaert, Jessop, and Mehmood Citation2016, 167). By combining aspects of path dependence and path shaping, the framework is compatible with the fundamental procedural and agentic perspective of path development (Martin Citation2010; Martin and Sunley Citation2006) but adds a discursive element that is important for regional transformative processes (Beer, Barnes, and Horne Citation2023; Steen Citation2016).

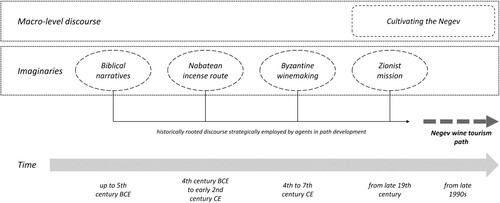

Since the ASID framework is a meta-theoretical heuristic that requires concretization for particular analytical purposes (Moulaert, Jessop, and Mehmood Citation2016), it can be applied to processes of spatial evolution by combining its elements with concepts known from the path development literature. Generally, the usefulness of the ASID framework for regional development and transformation has been demonstrated by Suitner and Ecker (Citation2020) who apply it to energy transitions and by Beer, Barnes, and Horne (Citation2023) who draw on different types of change agency and opportunity spaces and add three broad types of discourse referring to government, markets, and partnerships. Despite the merits of such an approach, the multiple and complex ways in which agency can unfold (Benner Citation2023c) including the role of non-change types of agency such as maintenance and reproductive agency (Bækkelund Citation2021; Henderson Citation2020; Jolly, Grillitsch, and Hansen Citation2020) and the fuzziness often involved in institutional definition and analysis (Bathelt and Glückler Citation2014; Hodgson, Citation2006) call for a more nuanced framework. We find it useful to propose a more specific framework for spatial evolution that distinguishes different levels of agency, structural conditions and their change through (multiscalar) opportunities, formal and informal institutions and discursive elements. sketches such an evolutionary ASID framework for the analysis of regional paths.

Table 1. Conceptual framework for ASID in spatial evolution.

In the ‘agency’ column of , we follow the firm/system-level distinction that captures a wide range of actions (Benner Citation2023c; Hassink, Isaksen, and Trippl Citation2019; Isaksen et al. Citation2019). The ‘structure’ column addresses structural conditions that define the context of a regional economy (Baumgartinger-Seiringer et al. Citation2022; Trippl et al. Citation2020) with the exception of institutions that are seen as specific ‘socialized structure’ (Moulaert, Jessop, and Mehmood Citation2016, 169). In a dynamic perspective, structure is affected by higher-order changes that confront agents with particular opportunities (Benner Citation2022a; Grillitsch and Sotarauta Citation2020) but also crises and other disruptions (Beer, Barnes, and Horne Citation2023; Suitner and Ecker Citation2020) as part of what Moulaert, Jessop, and Mehmood (Citation2016, 172) call ‘conjunctural dynamics’. The ‘institution’ column refers to both formal and informal institutions (Bathelt and Glückler Citation2014; Gertler Citation2010; Hodgson Citation2006; North Citation1990). Finally, the ‘discourse’ column draws attention to both abstract macro-cultural discourses (Lawrence and Phillips Citation2004; Zerubavel Citation2019) and more concrete imaginaries that guide agents’ actions in path development (Miörner Citation2022; Sotarauta Citation2018; Steen Citation2016; Suitner and Ecker Citation2020). The meanings conveyed by macro-cultural discourses and imaginaries can reach far into the past and take a long-term historical dimension (e.g. Azaryahu Citation2005; Shilo and Collins-Kreiner Citation2019, Citation2022; Zerubavel Citation2019). Hence, following Swidler (Citation1986), discourse can be understood as a rich cultural repertoire that contains a number of ‘symbolic vehicles of meaning’ (273) with varying ranges and scopes.

A weakness of the ASID framework that is partly due to its meta-theoretical character is that it remains vague on the precise interactions between its elements. While Moulaert, Jessop, and Mehmood (Citation2016) stress the mediating role of institutions between structure and agency, the role of discourse is less clear, although evidence suggests that discourse can affect institutions and both are shaped by agency in turn (Benner Citation2022a, Citation2023a; Lawrence and Phillips Citation2004; Swidler Citation1986). Elucidating these interactions is critical for sharpening the evolutionary dimension of the ASID framework. While structure and agency interact (Giddens Citation1984), we follow Archer's (Citation1982) morphogenetic approach that assumes structure predates agency. Hence, structure is rooted in the past and exhibits features of path dependence, although not in a ‘canonical’ way but in a contingent sense (Martin Citation2010; Martin and Sunley Citation2006). The same holds true for institutions as a more specific expression of structure. They will typically exhibit a considerable degree of ‘institutional hysteresis’ implying their short-term exogeneity (Setterfield Citation1993). At the same time, in the long run structures and institutions are shaped by agency (Archer Citation1982; Giddens Citation1984; Setterfield Citation1993) which consists of past, present, and future aspects (Emirbayer and Mische Citation1998). These intertemporal aspects of agency are reinforced by discourse which helps agents connect the past and future through meaning-making imaginaries which are, in turn, used and shaped strategically and sometimes controversially by agents (Benner Citation2022a; Binz and Gong Citation2022; Shilo and Collins-Kreiner Citation2019) who choose from the cultural repertoires available to them (Swidler Citation1986). These cultural repertoires include long-term historical roots and associations which carry history over into the development of a new path (Henning Citation2019; Martin and Sunley Citation2022).

In the next section, we use the empirical case of wine tourism in Israel’s Negev desert to examine and clarify the interactions between the elements of the evolutionary ASID framework in an attempt to demonstrate how a systematic conceptualization of discourse can help better understand processes of spatial evolution.

Wine tourism in the NegevFootnote1

At about 60 per cent of Israel’s territory, the Negev desert in Israel’s south covers a large part of the country (Teschner, Garb, and Tal Citation2010). In terms of population, the Be’er Sheva subdistrict that includes the Negev had just above 800,000 inhabitants (less than ten percent of Israel's population) but witnessed enormous growth up from only 14,000 in 1948 (Central Bureau of Statistics Citation2022). The arid, rural Negev belongs to the country’s periphery, is socio-economically lagging, and is addressed by long-standing national spatial planning policies such as the government’s ‘Negev 2015’ strategic plan dating from 2005 that, among other goals, aimed at growing the regional population by 200,000 inhabitants, improving the socio-economic status of the Bedouin minority, and developing tourism (Hillel, Belhassen, and Shani Citation2013; Teschner, Garb, and Tal Citation2010; Zerubavel Citation2019). Indeed, despite or maybe precisely because of being regarded as a desolate space far removed from urban civilization (Azaryahu Citation2005; Zerubavel Citation2019), for more than a decade the Negev has seen a boom in desert tourism, drawing on a discourse that combines distance and emptiness with desires for adventure, respite, and spirituality (Schmidt and Uriely Citation2019; Zerubavel Citation2019). The combination of the region’s peripheral status, its importance for socio-economic development in Israel, its rich history, and the rise of desert tourism make Negev wine tourism an interesting case for studying the role of historically-rooted discourse in spatial evolution, given the underused potential for tourism centred on authentic Negev agricultural produce (Hillel, Belhassen, and Shani Citation2013).

In line with a boom in winemaking and a spread of boutique wineries in Israel, during the past roughly two decades the Negev has seen the rise of a winemaking industry facilitated by drip irrigation technologies (Jaffe and Pasternak Citation2004; Rogov Citation2012). Some of the Negev winemakers have diversified towards complementary offers such as tourism. This path mirrors the increasing popularity of wine tourism both in Israel (Jaffe and Pasternak Citation2004; Shor and Mansfeld Citation2012) and internationally (Cambourne et al. Citation2004; Getz et al. Citation2008; Mitchell and Hall Citation2006).

Wine tourism is particularly suited as a lever for regional development in rural regions and is often organized and marketed under the framework of wine routes (Cambourne et al. Citation2004; Hall and Mitchell Citation2000; Hall, Johnson, and Mitchell Citation2004). Studies on wine routes suggest they can lead to tourism-driven growth in rural regions (e.g. Vázquez Vicente, Martín Barroso, and Blanco Jiménez Citation2021) but at the same time can face institutional challenges as coordinating stakeholders in wine routes and encouraging their collaboration may suffer from unclear definitions of the wine route (Bregoli et al. Citation2016) or weak interactions with public-sector promotion agents (Festa et al. Citation2020). In Israel, while the development of a wine industry and wine tourism are fairly recent phenomena, they allude to a long history (Cambourne et al. Citation2004; Hall and Mitchell Citation2000), given that ‘Israel is one of the birthplaces of wine, having established the industry some 4300 years ago’ (Jaffe and Pasternak Citation2004, 238).

Another trend visible in the Negev is the attempt to harness the region’s rich past for culturally-based forms of tourism, building on a number of archeological sites dating from the Nabatean period such as Avdat, Mamshit, Nitzana and Shivta but also Roman and Byzantine archeological heritage (Fuks et al. Citation2020; MDPNG and NDA Citationn.d.; Zerubavel Citation2019). The fourth century BCE saw a prospering incense trade with Nabatean merchants carrying frankincense and myrrh along the trade routes between the Arabian Peninsula and the Roman Empire (Amar Citation2021; Ben-David Citation2021; Shilo and Collins-Kreiner Citation2022). The Nabateans as one of the tribes residing on the Arabian Peninsula played a key role in the ancient incense route economy which flourished up to the year 106 CE when the Nabatean kingdom was annexed by the Roman empire (Rosenthal-Heginbottom Citation2003; Shilo and Collins-Kreiner Citation2022). Frankincense and myrrh were a valuable and regularly used good for Pagan worship rituals, and the Nabatean kingdom became a local power whose economic success was built on frankincense and myrrh (Amar Citation2021; Ben-David Citation2021; Shilo and Collins-Kreiner Citation2022). This history provides an important historical background for today’s tourism in the Negev as the ancient Nabatean incense route was recognized as UNESCO world heritage in 2005 (MDPNG and NDA Citationn.d.; Zerubavel Citation2019).

It was particularly during the late Roman and Byzantine periods that the south of the country became a prominent winemaking region (Rogov, Citation2012). According to new archeological evidence, between the 4th century to the mid-6th century CE, the Negev wine industry for export culminated (Fuks et al. Citation2020). The famous white wines of the Negev, known as ‘Gaza wine’ due to its shipment from Gaza port, were sent to markets across Europe, and the vineyards in the Negev highlands flourished (Fuks et al. Citation2020).

Wine tourism and the archeological and historical heritage are complementary in tourism development in the Negev. According to Getz et al. (Citation2008), due to their consumer characteristics, ‘wine tourists also want a range of cultural and outdoor experiences’ (265). Given that archeological interest is considered a suitable and complementary way to augment wine tourism in Israel (Jaffe and Pasternak Citation2004), the touristic valorization of historical imaginaries such as the Nabatean incense route and the Byzantine heritage provides a discursive background to the path development of wine tourism in the Negev.

Zerubavel (Citation2019) traces the emergence of the Negev wine route which was based on the establishment of up to thirty individual farms in the Negev during the late 1990s and early 2000s (see also Hillel, Belhassen, and Shani Citation2013). According to her, the programme of establishing this route of farms ‘foregrounded the agricultural component and evoked an association with wine tourism as well as with the ancient Nabbatean [sic] Incense Route’ (132) in an attempt to both settle and economically develop the peripheral region, albeit the programme met considerable resistance by environmental groups (Zerubavel Citation2019). In addition, the Sfat haMidbar programme promoted agritourism including winemaking in the Negev town of Mitzpe Ramon (Schmidt and Uriely Citation2019; Zerubavel Citation2019). In recent years, wine tourism has been part of the regional tourism marketing efforts, along with the Negev’s natural and archeological heritage including the Nabatean incense route (MDPNG and NDA Citationn.d.; Zerubavel Citation2019). However, Hillel, Belhassen, and Shani (Citation2013) lament the lack of regional authenticity in marketing the Negev’s agricultural produce (including wine) in tourism, as well as the weak links between wine and other regional food products.

Within this context, the case study applies the conceptual framework for ASID in spatial evolution () to the development of the wine tourism path in the Negev and explores how discourseFootnote2 and its long-term historical roots and associations interact with agency, structure and institutions in processes of spatial evolution.

Methods

Wine tourism in the Negev serves as a paradigmatic case study (Flyvbjerg Citation2006; Yin Citation2018) to examine the role of discourse in spatial evolution. Following Martin and Sunley’s (Citation2022) recommendation, we aim at providing a narrative account in a logic of appreciative theorizing that ‘stays close to the empirics of a particular case’ (77). For our research interest in revealing the role of discourse as a carrier of history, the Negev is particularly well-suited because of its long and meaning-charged history and modern efforts to reconnect with this history and its cultural meanings to promote regional tourism (Zerubavel Citation2019).

The case study is based on a series of twelve semi-structured interviews (Flick Citation2014; Helfferich Citation2019) conducted between June and October 2022. Of the thirteen intervieweesFootnote3, twelve represented vineyards and/or wineries while one represented an intermediary organization,Footnote4 all of them related to winemaking and/or wine tourism in the Negev. Most of the vineyards or wineries represented were small, family-led wineries and most of the winemakers interviewed were their owners. Interviewees were sampled according to one author’s (S.) knowledge in the field as a tourism developer and consultant, and the number of interviews reflects the threshold at which theoretical saturation can typically be expected (Guest, Bunce, and Johnson Citation2006). Interviews were conducted in Hebrew. The first interview was conducted by one author (S.) accompanied by two students, each subsequent interview was conducted by one of these students, respectively, and the last interview was conducted by the same author and the two students together. All interviews followed an interview guideline prepared by the authors. Most interviews were held as online video conferences but three were held face to face in full and one in part.Footnote5 As all interviewees stated their informed consent to recording, all interviews were recorded and transcribed by the students. Both authors listened to the recordings and checked the transcripts.Footnote6 One author (B.) subsequently analyzed the transcripts through coding along a deductive coding structure (Mayring and Fenzl Citation2019) derived from the conceptual framework (), using MaxQDA coding software (Kuckartz and Rädiker Citation2019). To deepen familiarization with the context and facilitate the interpretation of results, the analyzing author visited the websites of the wineries and/or read older wine guide entries (Rogov Citation2012) where available, respectively. In sum, the empirical work produced almost ten recorded hours and 129 transcript pages.Footnote7

Results

The results presented cover the development of winemaking and wine tourism in the Negev since 1995 when the first of the vineyards was established. The processes propelling path development are analyzed below along the ASID framework but with a particular focus on the historical roots of discourse.

Agency

On the firm level, entrepreneurial activity, innovation, and experimentation is apparent in the development first of winemaking (vineyards and/or wineries) and second of wine tourism. Engaging in wine tourism by offering winery tours, seminars, or tastings seemed logical from the perspective of winemakers, as occasional references to internationally known wine regions or countries such as Napa Valley or Australia suggest, but concrete motivations included also marketing wines directly to customers or making wine more accessible to them. For some entrepreneurs, wine tourism is complemented by food or accommodation offers or by other agricultural produce such as olive oil.

System-level agency includes the national Ministry of Tourism with its marketing and tourism development activities in the Negev in general. More specifically for wine tourism, system-level agency is exerted particularly by the Merage Foundation, a philanthropic organization that promotes winemaking in the Negev through the setup of a network, the ‘Negev Wineries Club’. Some interviewees considered this initiative to have contributed to more cooperation among winemakers in the Negev, and one interviewee expressed the opinion that this cooperation works only because of the support provided by the foundation. However, another interviewee considered the foundation’s work on wine tourism in the Negev still too recent to evaluate its impact. This private system-level support somewhat contrasts with official tourism policy which is evaluated differently among interviewees. While one interviewee highlighted the support for wine tourism by the tourism ministry, another rather critical one considered the efforts undertaken by tourism policy insufficient:

The only ones pushing the subject of wine tourism are like the Merage Foundation plus all sorts of similar, small organizations. The Ministry of Tourism does not promote wine tourism. I never saw an ad [saying], ‘come taste the wine of Israel’. (interview #3)

Structure

At the nexus between firm-level agency and structure, the buildup of a regional stock of human skills and knowledge seem to have been a decisive factor in the development of winemaking and wine tourism. Some interviewees stated having learned about winemaking in the winemaking courses offered by a winery in the centre of the country or drawing on suitable knowledge of family members. Nevertheless, the acquisition of needed skills was not always without difficulty, particularly when entrepreneurs diversified towards less related knowledge, which hints at the structural obstacles they encountered:

When I decided to establish the winery, I understood that I needed to learn how to make wine. The issue of the vineyards was easier because I was born as a farmer, I know agriculture from bottom to top, although it was vegetables, but converting to vineyards was very easy, (…) the hardest part to me was [setting up] the winery itself. (interview #12)

Somewhat surprisingly, the COVID-19 pandemic turned out to be a major structural opportunity for wine tourism in the Negev. One interviewee explained how during the COVID-19 pandemic, demand for online wine courses among Israeli consumers looking for entertainment activities at home increased, reinforcing interest in wine at large. At the same time, restrictions on foreign travel increased the attractiveness of wine tourism within the country, and the attractiveness of wine tourism specifically in the Negev was additionally underpinned by the imaginary of the region’s remoteness from dense and pandemic-strained urban life. For example, celebrating open-air weddings in a vineyard fitted the conditions of the pandemic. Taken together, one interviewee summarized the effect of the pandemic on domestic wine tourism:

During the corona period, the wineries in particular discovered that they would be the first that could emerge out from the crisis because many people came out of their homes, the lockdown was over, it was permitted to move around, but there were no restaurants. Yet, it was permitted to enter a winery. So post-Covid wine tourism was created that helped many wineries to find an income. (interview #8)

Notwithstanding, the relative lack of a critical mass in wine tourism and, as a consequence, the large distances between wineries in the Negev as well as the reliance on independent travellers and lack of organized offers are structural problems raised:

I don’t think that to date, (…) there is something that can be called wine tourism in the Negev, (…) it’s not like you travel, say, on the Golan heights, although there is no wine route, or in (…) Mateh Yehuda [near Jerusalem], you feel [it’s] full of wineries (…). What have we got here? Hardly any wineries. (interview #12)

Wine tourism, that’s mass, that’s a shuttle, that’s a bus that someone must organize on a regular basis, that would leave every day from Tel Aviv with 50 people in a luxurious bus, with a professional guide that talks all along the way about Israeli wine in the Negev highlands, and the bus would stop in several places on the same day. (interview #8)

Institutions

When it comes to formal institutions, several interviewees complained about the bureaucratic burden involved in winemaking and wine tourism. Despite the tourism ministry’s efforts at promoting tourism, complaints about bureaucratic hurdles (e.g. against constructing buildings on vineyards) could be interpreted as a fragmented governmental approach to tourism due to contradictory institutional and regulatory remits of government agencies. For example, one interviewee stated the impression that ‘there is perhaps opposition by the state because this is agricultural land and on agricultural land it is forbidden to do tourism’ (interview #5), a problem rooted in spatial planning and contradicting the very rationale of the Negev wine route. These institutional contradictions are also evident in another interviewees’ perception:Footnote8

The problem is that you need a permit for this and a permit for that and a permit for that … you can plan as much as you want, but if one organization or one government ministry does not give its permit, that ruins everything, [there is] too much bureaucracy. (interview #3)

We are also discovering many wineries. We did not know they exist and suddenly, from ten that we were in the beginning in the [activities of the] Merage Foundation, suddenly it turns out that there are 30. (…) As people get to know others, they develop friendships and that helps them. (interview #2)

Discourse

The imaginary of the Negev wine route was not uncontroversial among interviewees. For example, one interviewee expressed criticism against it, saying that ‘I don’t know what that is, the Negev wine route. I saw a sign twenty years ago. (…) There are many routes [but] there’s not much wine’ (interview #3). Another interviewee downplayed the importance of the wine route for branding wine tourism in the Negev and another one considered regional efforts to valorize the wine route for tourism not successful so far. In a similar vein, an interviewee expressed sympathy for the imaginary of a wine route but stated that it is not yet operational because ‘a wine route, that’s not just wineries, that’s a path, and where do you sleep and where do you eat’ (interview #6) which would call for a more organized effort. These different interpretations reveal a certain ambiguity about how the imaginary is understood, for example as the original programme, a brand, a support scheme, or simply a map of Negev wineries. Nevertheless, current efforts to achieve a geographical indication for Negev wines hint at a certain complementarity with the Negev wine route imaginary.

Beyond the Negev wine route as such, historically rooted discourses were widespread in the interviews. The Nabatean incense route is one of those imaginaries that figure prominently in the discourse on winemaking in the Negev:

Basically, we are sitting on almost the same routes which were traveled in the past by traders, pilgrims, or tourists. (interview #7)

I believe that the story of the Nabateans is fundamental. With us that was really a part of the story that everybody who comes to the winery also hears. (interview #2)

We have an old tradition of growing vines in the Negev. (…) And then they discovered the terraces that were [built by] the Nabateans and suddenly you plant the vineyards on the terraces. (…) You understand that there was something before. (…) So there’s a very important role of this history. (interview #6)

I believe that people are excited about hearing that the history began many years ago and wine is still made here. (interview #2)

As there was the spice [incense] route there was also an ancient wine route that is not documented (…). On this route [between Arad and Mitzpe Ramon] there were tens of Nabatean growers that made wine and tourism, (…) there were no tourists then as [there are] today, but there was tourism of traders (…) [that came] to do business. (interview #8)

You can buy a bottle of wine everywhere, at a supermarket, (…) but [customers] do look for the story (…) of (…) the Nabateans. (interview #9)

That’s a brand (…), that’s something that everyone knows and hears, even if they don’t know what it is. (interview #10)

Another imaginary that became apparent in several interviews was the Zionist mission of winemaking in the Negev that is historically rooted, inter alia, in the interest of Israel’s first prime minister David Ben Gurion in developing the region, and that is well documented in the macro-cultural discourse about the desert in Israeli society which can in turn be traced back to historical narratives of the Exodus and the Jewish diaspora (Zerubavel Citation2019). One interviewee explicitly linked winemaking in the Negev to a motivation to ‘make the wilderness bloom’ (interview #5) which belongs to the long-standing Israeli macro-cultural discourse (Shapira Citation2015; Zerubavel Citation2019). This imaginary seems widespread among Negev winemakers and relates to feelings of authenticity (see also Hillel, Belhassen, and Shani Citation2013) among domestic wine tourists who seek ‘to see with their eyes the vineyard and the farmer, (…) they also strongly connect to this on the Zionist level’ (interview #5). Interestingly, one interviewee referred to citizens evacuated from the Sinai and Gaza strip after the Israeli withdrawals from these territories, respectively, as performing a Zionist mission in settling in the neighbouring Negev and performing some kind of agriculture there.

Another imaginary that surfaced was Israel’s history as one of the ancient cradles of winemaking (see also Rogov Citation2012) which is evident, for example, in one winemaker’s collaboration with a university that aims at re-cultivating ancient grape varieties. This imaginary is often joined with reminiscences of the viticultural tradition during the Byzantine era,Footnote9 as these two winemakers explained:

The Byzantines made great wine here, now we are not Byzantines indeed but we make great wine. That’s the link I would make. (…) I’m sitting on a 1,500 year-old agricultural estate. (interview #4)

This region was considered one of the regions with the best wine in all of the Byzantine empire. (interview #10)

If there’s a winery of one and a half million liters from the Byzantine era, that has to be a place that thousands of people come to see. (…) But that doesn’t fit our story, so we conceal it [in tourism policy]. (interview #3)

I am not an industrialist. I’m not even a producer. I’m a person who lives in the middle of the most authentic desert in the world, the cradle of worldwide culture, the cradle of the Tanakh [Hebrew Bible]. Everything happened here, everything began here, and we have got the privilege and the gift of living here, (…) and giving tourists the atmosphere that Abraham gave to his guests. (interview #8)

Discussion and conclusions

According to the terminology of the path development literature (Grillitsch, Asheim, and Trippl Citation2018), the initial setup of individual farms along the Negev wine route can be classified as a combination of partial path importation insofar as entrepreneurs came from the centre of the country to the Negev and path branching as some of them diversified into winemaking from other agricultural products. Although the idea of linking tourism to wine was inherent to the original plan of the Negev wine route (Zerubavel Citation2019), the development of tourism offers on vineyards and in wineries was a gradual process of path diversification into an activity that required new skills and knowledge (Grillitsch, Asheim, and Trippl Citation2018). The difficulty of diversification towards more unrelated activities is underlined evocatively by entrepreneurs’ efforts in upgrading their knowledge and skills. This, together with physical distances and administrative fragmentation, confirms some of the barriers to wine tourism enumerated by Hall (Citation2005).

Figure 1. Timeline of historical roots of discourse in Negev wine tourism. Source: authors’ elaboration with historical dates drawing on Amar (Citation2021), Ben-David (Citation2021), Fuks et al. (Citation2020), Rosenthal-Heginbottom (Citation2003), Shapira (Citation2015), Shilo and Collins-Kreiner (Citation2022), and Zerubavel (Citation2019).

Table 2. Agency, structure, institutions, and discourse in the development of wine tourism in the Negev.

The interaction between structure and agency is particularly visible in the coincidence of the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and the increasing interest in wine among domestic consumers on the one hand and the Merage Foundation’s support for networking among winemakers on the other hand. While this coincidence was accidental, it demonstrates how agency fills emerging opportunity spaces (Grillitsch and Sotarauta Citation2020), thus confirming the role of a system-level ‘champion’ in wine tourism (Hall Citation2005). The institutional patterns visible suggest that different stages of path development bring with them specific institutional patterns in that the initial cohesion may weaken as the path grows and eventually can be rebuilt by system-level agency while the contradictory policy and planning environment (see also Teschner, Garb, and Tal Citation2010) suggests a fragmented institutional infrastructure (Baumgartinger-Seiringer, Miörner, and Trippl Citation2021; Baumgartinger-Seiringer et al. Citation2022).

When it comes to discourse, although winemakers disagreed about which imaginaries are important, their role in strategically employing imaginaries taken from a cultural repertoire (Swidler Citation1986) as discursive devices in spatial evolution becomes clear. Still, how winemakers engage with the Negev wine route imaginary varies considerably and might call for dedicated system-level agency in reaching a common understanding of what precisely it means and how it can be used to promote wine tourism, consistent with research on Italian wine routes (Bregoli et al. Citation2016). Further, there is considerable disagreement about which part of the Negev’s history to primarily draw on (e.g. Nabatean, Byzantine, or Jewish periods), although as subsequent historical eras these imaginaries are clearly complementary. This suggests a need for additional awareness building and promotional efforts to create a common understanding on how to market the Negev wine route and thus highlighting the regional authenticity of Negev winemaking and embedding it into an authentic wider food tourism product (Hall Citation2005; Hillel, Belhassen, and Shani Citation2013).

This article sought to explore how discourse serves as a carrier of long-term history in spatial evolution embedded in structure-agency dynamics through the analytical heuristic of a specific ASID framework. Nevertheless, by drawing on a single case, the article has its limitations that call for further research. The Negev wine tourism case is instructive because of its strong roots in historical imaginaries and the peripheral, rural area covered which makes it particularly interesting for other rural areas with a rich cultural and historical repertoire. Future multiple-case research along these lines would be useful, particularly in rural regions across countries that seek to develop tourism at the intersection between culture and agriculture in arid areas and under difficult climatic conditions.

In sectoral terms, wine tourism provides an idiosyncratic case whose conclusions are difficult to generalize beyond the tourism industry. Nevertheless, the specific ASID framework for spatial evolution we propose can be useful for analyzing the role of historical imaginaries underpinning the evolution of other industries in other regions. For instance, the emerging geography of sustainability transitions (Hansen and Coenen Citation2015) could benefit from the framework by examining how sustainability-focused fringe discourses such as the one on organic or natural winemaking observed are historically rooted. More wide-ranging research is certainly welcome to understand how paths are built and developed by agents drawing on historical heritage that can reach back to times far preceding the industrial era.

Acknowledgments

Both authors are grateful to Hila Nisan and Oren Or for conducting and transcribing the interviews. M. Benner is grateful to Michaela Trippl and Erika Faigen for suggestions or comments. Further, the authors are grateful to two reviewers for their useful comments, and to the editor. Of course, all errors and omissions are the authors’ alone, as are any opinions expressed.

Disclosure statement

S. Shilo is involved in promoting tourism in the Negev as the head of the Friendly Negev Desert destination management organization as well as in tourism development in Israel as a consultant to the Ministry of Tourism. He also has partial family ties to one of the Negev wineries.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Insofar as the case study addresses imaginaries about the Negev in general and tourism policy there, it draws on Benner (Citation2022a, Citation2023a).

2 For a wider analysis of the role of discourse in gastronomic tourism in the Negev at large, see Hillel, Belhassen, and Shani (Citation2013).

3 One interview covered two interviewees.

4 Drawing on two interviewee types (winemakers and intermediaries) can be regarded as an element of data triangulation (Denzin Citation2009; Flick Citation2014).

5 Due to an interruption, one interview was held on two dates, one online and the other face to face.

6 Transcriptions were slightly simplified (e.g. by leaving out repetitions, filling words, digressions, or interviewer explanations).

7 Interview quotes taken from the transcripts were translated into English by the authors and, in some instances, the English language translation was slightly modified to enhance readability.

8 Israel’s land rules and laws were shaped during the early years of the state and reflect the primary importance of agriculture compared to a low priority for tourism for the young state (see also MARD Citation2015).

9 In a similar vein, one interviewee referred to the Crusader era.

References

- Amar, Z. 2021. “Myrrh and Frankincense: The Incense Components on the Nabatean-Arab Trade Routes.” In The Perfume Routes 2020 (in Hebrew), edited by H. Ben-David and D. Pery, 19–29. Jerusalem: Magnes.

- Archer, M. 1982. “Morphogenesis Versus Structuration: On Combining Structure and Action.” The British Journal of Sociology 33: 455–483. doi:10.2307/589357.

- Azaryahu, M. 2005. “The Beach at the end of the World: Eilat in Israeli Popular Culture.” Social & Cultural Geography 6: 117–133. doi:10.1080/1464936052000335008.

- Bækkelund, N. 2021. “Change Agency and Reproductive Agency in the Course of Industrial Path Evolution.” Regional Studies 55: 757–768. doi:10.1080/00343404.2021.1893291.

- Bathelt, H., and J. Glückler. 2014. “Institutional Change in Economic Geography.” Progress in Human Geography 38: 340–363. doi:10.1177/0309132513507823.

- Battilana, J., B. Leca, and E. Boxenbaum. 2009. “How Actors Change Institutions: Towards a Theory of Institutional Entrepreneurship.” Academy of Management Annals 3: 65–107. doi:10.5465/19416520903053598.

- Baumgartinger-Seiringer, S., L. Fuenfschilling, J. Miörner, and M. Trippl. 2022. “Reconsidering Regional Structural Conditions for Industrial Renewal.” Regional Studies 56: 579–591. doi:10.1080/00343404.2021.1984419.

- Baumgartinger-Seiringer, S., J. Miörner, and M. Trippl. 2021. “Towards a Stage Model of Regional Industrial Path Transformation.” Industry and Innovation 28: 160–181. doi:10.1080/13662716.2020.1789452.

- Beer, A., T. Barnes, and S. Horne. 2023. “Place-based Industrial Strategy and Economic Trajectory: Advancing Agency-Based Approaches.” Regional Studies 57: 984–997. doi:10.1080/00343404.2021.1947485.

- Ben-David, H. 2021. “The History of the Trade in Perfumes.” In The Perfume Routes 2020 (in Hebrew), edited by H. Ben-David and D. Pery, 11–17. Jerusalem: Magnes.

- Benner, M. 2020. “Mitigating Human Agency in Regional Development: The Behavioural Side of Policy Processes.” Regional Studies, Regional Science 7: 164–182. doi:10.1080/21681376.2020.1760732.

- Benner, M. 2022a. “A Tale of Sky and Desert: Translation and Imaginaries in Transnational Windows of Institutional Opportunity.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 128: 181–191. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.12.019.

- Benner, M. 2022b. “Retheorizing Industrial–Institutional Coevolution: A Multidimensional Perspective.” Regional Studies 56: 1524–1537. doi:10.1080/00343404.2021.1949441.

- Benner, M. 2023a. “Legitimizing Path Development by Interlinking Institutional Logics: The Case of Israel's Desert Tourism.” Local Economy: 1–20. doi: 10.1177/02690942231172728.

- Benner, M. 2023b. “Revisiting Path-as-Process: Agency in a Discontinuity-Development Model.” European Planning Studies 31: 1119–1138. doi:10.1080/09654313.2022.2061309.

- Benner, M. 2023c. “System-level Agency and its Many Shades: Path Development in a Multidimensional Innovation System.” Regional Studies, doi:10.1080/00343404.2023.2179614.

- Binz, C., and H. Gong. 2022. “Legitimation Dynamics in Industrial Path Development: New-to-the-World Versus new-to-the-Region Industries.” Regional Studies 56: 605–618. doi:10.1080/00343404.2020.1861238.

- Blažek, J., V. Květoň, S. Baumgartinger-Seiringer, and M. Trippl. 2020. “The Dark Side of Regional Industrial Path Development: Towards a Typology of Trajectories of Decline.” European Planning Studies 28: 1455–1473. doi:10.1080/09654313.2019.1685466.

- Borup, M., N. Brown, K. Konrad, and H. Van Lente. 2006. “The Sociology of Expectations in Science and Technology.” Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 18: 285–298. doi:10.1080/09537320600777002.

- Boschma, R., and K. Frenken. 2006. “Why is Economic Geography not an Evolutionary Science? Towards an Evolutionary Economic Geography.” Journal of Economic Geography 6: 273–302. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbi022.

- Bregoli, I., M. Hingley, G. Del Chiappa, and V. Sodano. 2016. “Challenges in Italian Wine Routes: Managing Stakeholder Networks.” Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal 19: 204–224. doi:10.1108/QMR-02-2016-0008.

- Cambourne, B., C. Hall, G. Johnson, N. Macionis, R. Mitchell, and L. Sharples. 2004. “The Maturing Wine Tourism Product: An International Overview.” In Wine Tourism Around the World: Development, Management and Markets, edited by C. M. Hall, L. Sharples, B. Cambourne, and N. Macionis, 24–66. Oxford: Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Central Bureau of Statistics. 2022. “Population, by District, Sub-district and Religion.” https://www.cbs.gov.il/he/publications/doclib/2022/2.shnatonpopulation/st02_15x.pdf.

- Denzin, N. 2009. The Research act: A Theoretical Introduction to Sociological Methods. New Brunswick: Aldine Transaction.

- DiMaggio, P. 1988. “Interest and Agency in Institutional Theory.” In Institutional Patterns and Organizations: Culture and Environment, edited by L. Zucker, 3–21. Cambridge: Ballinger.

- Emirbayer, M., and A. Mische. 1998. “What is Agency?” American Journal of Sociology 103: 962–1023. doi:10.1086/231294.

- Essletzbichler, J., and D. Rigby. 2007. “Exploring Evolutionary Economic Geographies.” Journal of Economic Geography 7: 549–571. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbm022.

- Festa, G., S. Shams, G. Metallo, and M. Cuomo. 2020. “Opportunities and Challenges in the Contribution of Wine Routes to Wine Tourism in Italy – a Stakeholders’ Perspective of Development.” Tourism Management Perspectives 33: 100585. doi:10.1016/j.tmp.2019.100585.

- Flick, U. 2014. An Introduction to Qualitative Research. 5th ed. London: SAGE.

- Flyvbjerg, B. 2006. “Five Misunderstandings About Case-Study Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 12: 219–245. doi:10.1177/1077800405284363.

- Friedland, R., and R. Alford. 1991. “Bringing Society Back in: Symbols, Practices, and Institutional Contradictions.” In The new Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis, edited by W. W. Powell and P. J. DiMaggio, 232–263. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Fuks, D., G. Bar-Oz, Y. Tepper, T. Erickson-Gini, D. Langgut, L. Weissbrod, and E. Weiss. 2020. “The Rise and Fall of Viticulture in the Late Antique Negev Highlands Reconstructed from Archaeobotanical and Ceramic Data.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117: 19780–19791. doi:10.1073/pnas.1922200117.

- Gertler, M. 2010. “Rules of the Game: The Place of Institutions in Regional Economic Change.” Regional Studies 44: 1–15. doi:10.1080/00343400903389979.

- Getz, D., J. Carlsen, G. Brown, and M. Havitz. 2008. “Wine Tourism and Consumers.” In Tourism Management: Analysis, Behaviour and Strategy, edited by A. G. Woodside and D. Martin, 245–268. Wallingford: CABI.

- Giddens, A. 1984. The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Grillitsch, M., B. Asheim, and M. Trippl. 2018. “Unrelated Knowledge Combinations: The Unexplored Potential for Regional Industrial Path Development.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 11: 257–274. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsy012.

- Grillitsch, M., and M. Sotarauta. 2020. “Trinity of Change Agency, Regional Development Paths and Opportunity Spaces.” Progress in Human Geography 44: 704–723. doi:10.1177/0309132519853870.

- Guest, G., A. Bunce, and L. Johnson. 2006. “How Many Interviews Are Enough?” Field Methods 18: 59–82. doi:10.1177/1525822X05279903.

- Hall, C. 2005. “Rural wine and food tourism cluster and network development.” In Rural tourism and sustainable business, edited by D. Hall, I. Kirkpatrick, and M. Mitchell, 149–164. Clevedon: Channel View.

- Hall, C., G. Johnson, and R. Mitchell. 2004. “Wine Tourism and Regional Development.” In Wine Tourism Around the World: Development, Management and Markets, edited by C. M. Hall, L. Sharples, B. Cambourne, and N. Macionis, 196–225. Oxford: Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Hall, C., and R. Mitchell. 2000. “Wine Tourism in the Mediterranean: A Tool for Restructuring and Development.” Thunderbird International Business Review 42: 445–465. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6874(200007/08)42:4<445::AID-TIE6>3.0.CO;2-H.

- Hansen, T., and L. Coenen. 2015. “The Geography of Sustainability Transitions: Review, Synthesis and Reflections on an Emergent Research Field.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 17: 92–109. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2014.11.001.

- Hassink, R., A. Isaksen, and M. Trippl. 2019. “Towards a Comprehensive Understanding of New Regional Industrial Path Development.” Regional Studies 53: 1636–1645. doi:10.1080/00343404.2019.1566704.

- Helfferich, C. 2019. “Leitfaden- und Experteninterviews.” In Handbuch Methoden der Empirischen Sozialforschung. 2nd ed., edited by N. Baur and J. Blasius, 669–686. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Henderson, D. 2020. “Institutional Work in the Maintenance of Regional Innovation Policy Instruments: Evidence from Wales.” Regional Studies 54: 429–439. doi:10.1080/00343404.2019.1634251.

- Henning, M. 2019. “Time Should Tell (More): Evolutionary Economic Geography and the Challenge of History.” Regional Studies 53: 602–613. doi:10.1080/00343404.2018.1515481.

- Hillel, D., Y. Belhassen, and A. Shani. 2013. “What Makes a Gastronomic Destination Attractive? Evidence from the Israeli Negev.” Tourism Management 36: 200–209. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2012.12.006.

- Hodgson, G. 2006. “What are Institutions?” Journal of Economic Issues 40: 1–25. doi:10.1080/00213624.2006.11506879.

- Isaksen, A., S. Jakobsen, R. Njøs, and R. Normann. 2019. “Regional Industrial Restructuring Resulting from Individual and System Agency.” Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research 32: 48–65. doi:10.1080/13511610.2018.1496322.

- Jaffe, E., and H. Pasternak. 2004. “Developing Wine Trails as a Tourist Attraction in Israel.” International Journal of Tourism Research 6: 237–249. doi:10.1002/jtr.485.

- Jolly, S., M. Grillitsch, and T. Hansen. 2020. “Agency and Actors in Regional Industrial Path Development. A Framework and Longitudinal Analysis.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 111: 176–188. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.02.013.

- Kuckartz, U., and S. Rädiker. 2019. Analyzing Qualitative Data with MaxQDA: Text, Audio, and Video. Cham: Springer.

- Kurikka, H., J. Kolehmainen, M. Sotarauta, H. Nielsen, and M. Nilsson. 2022. “Regional Opportunity Spaces – Observations from Nordic Regions.” Regional Studies, doi:10.1080/00343404.2022.2107630.

- Lawrence, T., and N. Phillips. 2004. “From Moby Dick to Free Willy: Macro-Cultural Discourse and Institutional Entrepreneurship in Emerging Institutional Fields.” Organization 11: 689–711. doi:10.1177/1350508404046457.

- Lawrence, T., and R. Suddaby. 2006. “Institutions and Institutional Work.” In The SAGE Handbook of Organization Studies. 2nd ed., edited by S. R. Clegg, C. Hardy, T. B. Lawrence, and W. R. Nord, 215–254. London: SAGE.

- MARD. 2015. “Rural Planning Document of Agricultural and Rural Planning Policy in Israel, Vol 1 (in Hebrew).” Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, https://www.gov.il/BlobFolder/policy/document_of_agricultural_and_rural_planning_policy_in_israel/he/rural-planning_document_of_agricultural_and_rural_planning_policy_in_israel_vol_1.pdf.

- Martin, R. 2010. “Roepke Lecture in Economic Geography-Rethinking Regional Path Dependence: Beyond Lock-in to Evolution.” Economic Geography 86: 1–27. doi:10.1111/j.1944-8287.2009.01056.x.

- Martin, R. 2012. “(Re)Placing Path Dependence: A Response to the Debate.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 36: 179–192. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2011.01091.x.

- Martin, R., and P. Sunley. 2006. “Path Dependence and Regional Economic Evolution.” Journal of Economic Geography 6: 395–437. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbl012.

- Martin, R., and P. Sunley. 2015. “Towards a Developmental Turn in Evolutionary Economic Geography?” Regional Studies 49: 712–732. doi:10.1080/00343404.2014.899431.

- Martin, R., and P. Sunley. 2022. “Making History Matter More in Evolutionary Economic Geography.” ZFW 66: 65–80. doi:10.1515/zfw-2022-0014.

- Mayring, P., and T. Fenzl. 2019. “Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse.” In Handbuch Methoden der Empirischen Sozialforschung. 2nd ed., edited by N. Baur and J. Blasius, 633–648. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- MDPNG, NDA. n.d. “The Friendly Negev Desert. Ministry for the Development of the Periphery, the Negev and the Galilee, Negev Development Authority.” https://negev.co.il/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Tourist_brochure.pdf.

- Miörner, J. 2022. “Contextualizing Agency in New Path Development: How System Selectivity Shapes Regional Reconfiguration Capacity.” Regional Studies 56: 592–604. doi:10.1080/00343404.2020.1854713.

- Mitchell, R., and C. Hall. 2006. “Wine Tourism Research: The State of Play.” Tourism Review International 9: 307–332. doi:10.3727/154427206776330535.

- Moulaert, F., B. Jessop, and A. Mehmood. 2016. “Agency, Structure, Institutions, Discourse (ASID) in Urban and Regional Development.” International Journal of Urban Sciences 20: 167–187. doi:10.1080/12265934.2016.1182054.

- North, D. 1990. Institutions, Institutional Change, and Economic Performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. 2013. “Do Institutions Matter for Regional Development?” Regional Studies 47: 1034–1047. doi:10.1080/00343404.2012.748978.

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. 2020. “Institutions and the Fortunes of Territories.” Regional Science Policy & Practice 12: 371–386. doi:10.1111/rsp3.12277.

- Rogov, D. 2012. The Ultimate Rogov's Guide to Israeli Wines. 8th ed. Jerusalem: Toby Press.

- Rosenthal-Heginbottom, R. ed. 2003. The Nabateans in the Negev. Haifa: Haifa University.

- Salazar, N. 2012. “Tourism Imaginaries: A Conceptual Approach.” Annals of Tourism Research 39: 863–882. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2011.10.004.

- Schmidt, J., and N. Uriely. 2019. “Tourism Development and the Empowerment of Local Communities: The Case of Mitzpe Ramon, a Peripheral Town in the Israeli Negev Desert.” Journal of Sustainable Tourism 27: 805–825. doi:10.1080/09669582.2018.1515952.

- Setterfield, M. 1993. “A Model of Institutional Hysteresis.” Journal of Economic Issues 27: 755–774. doi:10.1080/00213624.1993.11505453.

- Sewell, W., Jr. 1992. “A Theory of Structure: Duality, Agency, and Transformation.” American Journal of Sociology 98: 1–29. doi:10.1086/229967.

- Shapira, A. 2015. Israel: A History. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- Shilo, S., and N. Collins-Kreiner. 2019. “Tourism, Heritage and Politics: Conflicts at the City of David, Jerusalem.” Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research 24: 529–540. doi:10.1080/10941665.2019.1596959.

- Shilo, S., and N. Collins-Kreiner. 2022. “The Return of the ‘Black Swan’? Christian Pilgrimage to the Holy Land and the Covid-19 Pandemic.” Journal of Qualitative Research in Tourism 3: 1–13. doi:10.4337/jqrt.2022.0002.

- Shor, N., and Y. Mansfeld. 2012. “Wine Consumption and Wine Tourism: Spatial Behavior of Israeli Wine Tourists.” Horizons in Geography 79/80: 100–117.

- Sotarauta, M. 2018. “Smart Specialization and Place Leadership: Dreaming About Shared Visions, Falling Into Policy Traps?” Regional Studies, Regional Science 5: 190–203. doi:10.1080/21681376.2018.1480902.

- Steen, M. 2016. “Reconsidering Path Creation in Economic Geography: Aspects of Agency, Temporality and Methods.” European Planning Studies 24: 1605–1622. doi:10.1080/09654313.2016.1204427.

- Suitner, J., and M. Ecker. 2020. “‘Making Energy Transition Work’: Bricolage in Austrian Regions’ Path-Creation.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 36: 209–220. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2020.07.005.

- Swidler, A. 1986. “Culture in Action: Symbols and Strategies.” American Sociological Review 51: 273–286. doi:10.2307/2095521.

- Teschner, N., Y. Garb, and A. Tal. 2010. “The Environment in Successive Regional Development Plans for Israel's Periphery.” International Planning Studies 15: 79–97. doi:10.1080/13563475.2010.490664.

- Tödtling, F., and M. Trippl. 2013. “Transformation of Regional Innovation Systems: From old Legacies to new Development Paths.” In Re-framing Regional Development: Evolution, Innovation and Transition, edited by P. Cooke, 297–317. London: Routledge.

- Trippl, M., S. Baumgartinger-Seiringer, A. Frangenheim, A. Isaksen, and J. Rypestøl. 2020. “Unravelling Green Regional Industrial Path Development: Regional Preconditions, Asset Modification and Agency.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 111: 189–197. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.02.016.

- Van Lente, H. 2021. “Imaginaries of Innovation.” In Handbook on Alternative Theories of Innovation, edited by B. Godin, G. Gaglio, and D. Vinck, 23–36. Northampton: Elgar.

- Vázquez Vicente, G., V. Martín Barroso, and F. Blanco Jiménez. 2021. “Sustainable Tourism, Economic Growth and Employment—The Case of the Wine Routes of Spain.” Sustainability 13: 7164. doi:10.3390/su13137164.

- Yin, R. 2018. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods. 6th ed. London: SAGE.

- Zerubavel, Y. 2019. Desert in the Promised Land. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Zilber, T. 2009. “Institutional Maintenance as Narrative Acts.” In Institutional Work: Actors and Agency in Institutional Studies of Organizations, edited by T. B. Lawrence, R. Suddaby, and B. Leca, 205–235. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Zukauskaite, E., M. Trippl, and M. Plechero. 2017. “Institutional Thickness Revisited.” Economic Geography 93: 325–345. doi:10.1080/00130095.2017.1331703