ABSTRACT

The paper unpacks the relationship between local culture and agency to enhance our understanding of local variations of agency. The paper studies two former old industrial places in Sweden; one place characterized by an entrepreneurial culture (Borås), the other with a company town culture (Kiruna). Both cases experienced structural crisis around 1970s. A study period of more than 30 years is used to analyse actions and actors present in different phases of development, using 38 semi-structured interviews. The concepts of change agency and reproductive agency are used to analyse agentic patterns. Cultural transformation is mapped using values, heroes, symbols and rituals. The paper finds that the entrepreneurial culture is an enabling condition for change agency, whereas the company town culture is hampering change agency. The paper also finds that lock-ins can continue to affect actors after a crisis and that opportunities for change agency therefore is actor-specific, i.e. that local agency varies between actors and over time. Reproductive agency is present in both regions to maintain the cultural identity, but the company town culture is more resistant to institutional changes. Yet, both local cultures have changed, and in both cases the changes have opened for more change agency.

1. Introduction

The purpose of this paper is to understand the relationship between agency and local culture. Economic geography has long focused on structural factors to explain regional development. Recently, a growing community seek to go beyond this by exploring the role of agency (Blažek and Květoň Citation2022; Grillitsch, Rekers, and Sotarauta Citation2021), including when and how change agency alters regional development (Grillitsch and Sotarauta Citation2020) and when and how reproductive agency preserves existing development (Bækkelund Citation2021; Jolly, Grillitsch, and Hansen Citation2020). The study of agency is relevant for our understanding of why old industrial places and regions with similar pre-conditions develop differently (Blažek and Květoň Citation2022). With a stronger focus on local leaders (Barca Citation2019) and entrepreneurs (Hassink and Kiese Citation2021) in place-based policy approaches, it is also important to learn more about actors’ willingness and capability to create change. Rekers and Stihl (Citation2021) find that local institutional context conditions change agency and that the perceived opportunities for change agency can be different even within the same small labour market. They call for further research on the linkages between institutions and change agency.

Institutions have for decades been considered important in theories of regional inequalities and economic development (Marques and Morgan Citation2021; Rodríguez-Pose Citation2013). However, there is a knowledge gap concerning how different institutions shape agency in regional development, especially informal institutions (Rodríguez-Pose Citation2020). The paper addresses this gap by focusing on one form of informal institution, namely local culture, to gain deeper understanding of local variations of agency and how local cultures affect agency. Local culture is here defined as a ‘a collective programming of the mind’ (Hofstede Citation2001, 9) that distinguishes different groups from each other and is manifested through values, heroes, symbols and rituals. The paper’s main geographical focus lies on the local scale, yet institutions are set in a multi-scalar relationship. Regional, national and international institutions also shape and affect local institutions (Marques and Morgan Citation2021).

The paper studies two former old industrial places from the same national context; one characterized by an entrepreneurial culture, the other one a company town. Both cases – Borås, an entrepreneurial region within textile and trade and Kiruna, a company town within mining – experienced restructuring during the 1970s, forcing local actors to adapt. However, Borås continue to spin forward and Kiruna to dig deeper. The two industries remain, but in upgraded form and complemented through diversification. Although the places’ economic base has greatly developed, the local culture tied to their history, still affect local actors and power structures. Entrepreneurs are considered drivers of change (Wigren-Kristoferson et al. Citation2022), whereas company towns are not. However, culture is not static (Hofstede Citation2001) and a changing culture could affect agency patterns. To unpack the relationship between local culture and agency, a study period of more than 30 years is used to analyse actions and actors present in different phases of development. The paper explores:

How do different local cultures affect change agency and reproductive agency?

How have local cultures and agency patterns changed over time?

The paper builds on the extensive literature addressing entrepreneurship culture (Andersson and Koster Citation2011; Beugelsdijk Citation2007; Stuetzer et al. Citation2018) and company towns (Borges and Torres Citation2012; Moonesirust and Brown Citation2021; Porteous Citation1970) and connects it to the burgeoning literature on change agency (Grillitsch and Sotarauta Citation2020) and reproductive agency (Bækkelund Citation2021; Jolly, Grillitsch, and Hansen Citation2020). The paper finds that the entrepreneurial culture in Borås is an enabling condition for change agency, whereas the company town culture in Kiruna is hampering it. However, the paper also finds that opportunities for change agency are actor-specific and that lock-ins can continue to affect actors long after restructuring, even in an entrepreneurial culture. This means that, in the same region, agency varies between actors and across time. There are periods when some local actors engage actively in change agency, while others do not perceive to have any agency at all. Reproductive agency is present in both regions to maintain the cultural identity, but the company town culture is more resistant to institutional changes. Yet, both local cultures have changed, and in both cases, the changes have opened up for more change agency.

2. Conceptual framework

2.1. Local culture

There are various sets of structures that influence agency. Within economic geography, structures can be seen as formal institutions (regulations, laws, directives) and informal institutions (routines, norms, values) as well as resources from current and previous industry paths (infrastructure, competence, skills, etc.). Both formal and informal institutions shape individuals’ behaviour (in ways that are not always obvious to the actors themselves), but do not determine behaviour (Gertler Citation2018). Previous research show that culture influence regional growth (see e.g. Saxenian Citation1996), but we know less of how it affects agency.

The paper recognizes local culture as an informal institution and define it like Hofstede (Citation2001, 9), i.e. ‘a collective programming of the mind that distinguishes the members of one group or category of people from another’, where the mind refers to a persons’ thinking, feeling and acting. As opposed to values (where the unit of analysis is the individual), a culture assumes collectivity and is hence studied on a societal level (Hofstede Citation2001). The value system (or system of societal norms) develops and maintains formal institutions. These then reinforce and reproduce informal rules and norms (Hofstede Citation2001). In open societies, institutions change over time when interacting with external cultures. Culture shall therefore be considered a process, and not static.

According to Hofstede (Citation2001), a culture is manifested in values, symbols, heroes and rituals. The value system is the least susceptible to change. Even though formal institutions might change, this does not automatically lead to changes in values. The three latter are more superficial and more susceptible to change. Symbols relates to particular words, gestures, pictures and objects that carry complex meaning, recognized by those who share the culture. Heroes refers to role models (alive, dead, or imaginary) that model behaviour. Rituals are collective activities that are not technically necessary, but important for the culture. In this paper, these concepts will be used to map culture, potential changes and who has the power to influence local culture. It should be noted that not all individuals in a locality will be part of a culture, neither does in-migrants automatically become a part of it. The most effective way of changing the mental programing is to start with changing the behaviour (Hofstede Citation2001). This can be done when outsiders or external forces start modelling other types of behaviour.

2.1.1. Entrepreneurial culture

Entrepreneurs can be characterized as having a need for autonomy, independence, achievements, and locus of control, and being opportunistic, innovative, creative, risk-taking, and having a high self-confidence (Beugelsdijk Citation2007; Hayton and Cacciotti Citation2013). Entrepreneurs need and perceive to have the power to control their own future (Beugelsdijk Citation2007) and are considered drivers of change (Wigren-Kristoferson et al. Citation2022). This suggests that they have a strong agency.

An entrepreneurial culture can therefore be defined as a collective programming oriented towards individualism, independence, innovation, motivation for achievement and risk taking (Fritsch and Wyrwich Citation2014). It is an informal institution that positively shapes the legitimacy of entrepreneurship (Fritsch and Wyrwich Citation2014; Stuetzer et al. Citation2018). Current or former entrepreneurs can act as role models and increase local entrepreneurial learning and act in ways that others can imitate (Andersson and Koster Citation2011). As role models, they can increase the acceptance of an entrepreneurial lifestyle and increase the demand for it. This can promote more resources to be dedicated to such activities. Seen in this way, it can become continuously reinforced and create long-term effects (Fritsch and Wyrwich Citation2014). It can endure regionally even beyond crisis phases and longer periods of changed formal institutions (Fritsch and Wyrwich Citation2014).

In the literature, having an entrepreneurial culture has long been suggested to have a positive effect on employment growth as well as indirect and direct effects on economic success. Stuetzer et al. (Citation2018) find a statistically significant positive relationship confirming it, a relationship that grows stronger with time. Nevertheless, living in an entrepreneurial region does not determine whether someone becomes an entrepreneur. Economic environment, family background, employment history, organizational experiences, social networks, national culture and personality traits are all factors that affect if a person acts entrepreneurial or not (Beugelsdijk Citation2007).

2.1.2. The culture of company towns

Company towns can be found globally and is ascribed many names: single enterprise communities, mill towns, factory villages, enclaves, colonias industrials (Spain), cités ouvrières (France), Arbeitersiedlungen (Germany), bruk (Sweden), villas obreras and cidadesempresa (South America) (Borges and Torres Citation2012). Company towns can be defined as a settlement built around a single enterprise to accommodate its workers, and where company control extend beyond its organizational boundaries into workers’ daily family life (Moonesirust and Brown Citation2021). Housing, schools and religious buildings were often built or associated with the company and its control extended into private life through social programmes (Garner Citation1992). The companies controlled physical planning, often leading to socially segregated residential areas and creating a local social control over workers. Workers’ characters were molded by the company through a paternalistic leadership, leaving little room for change agency for residents. Loyalty to the company was promoted over individualism (Porteous Citation1970). Most company towns appeared between 1830 and 1930 (Garner Citation1992). Though parts of the culture changed in the west with the rise of the welfare state and unions (Bursell Citation1997; Porteous Citation1970), company towns have remained in a modernized form, often in peripheral areas (Porteous Citation1970).

The industry that grew in Sweden during early twentieth century was to a large extent based on exploitation and processing of raw materials. Industrial development therefore mainly grew in small, scattered communities in the periphery, dominated by single companies. The culture in company towns was dominated by patriarchal and hierarchical power structures with a silent agreement over responsibilities and functions. The company ensured work and social services, and the residents were a stable work force over generations. The communities had a clear social stratification where inhabitants did not socialize between social groups. Individuals’ initiatives and entrepreneurial activities was discouraged and there was a reluctance to change (Isacson Citation1997). Positive characteristics were solidarity, focus on the collective, and the construction of the welfare state.

The culture in company towns is still shaping development in many localities (Moonesirust and Brown Citation2021). The work-identity has been embedded to exercise control over residents, leading to intertwined relationships extending beyond traditional organizational boundaries such as family, union, corporation, school etc. (Moonesirust and Brown Citation2021). The cultural programming (e.g. how opportunities are understood) has survived beyond industrialization and continues to coexist in a post-industrial culture (Byrne Citation2002; Forsberg Citation1997). Empirical evidence from British regions with former large-scale industries, continue to show lower levels of entrepreneurial activity (Stuetzer et al. Citation2016). This indicates long-term effects of low levels of entrepreneurship as well.

2.2. Agency

Structure and agency are iteratively developing: some structures are reproduced, while others are transforming. Emirbayer and Mische (Citation1998) define three analytical dimensions of agency to capture the temporal changes of structure and agency, in order to highlight how actors adapt to structural constraints and previous knowledge (iteration), the present (practical-evaluative), and the actor’s perception of the future (projective) when acting. By examining actors’ changes in agentic orientation, we can analyse their maneuverability, inventiveness and choices in relation to constraining and enabling factors. This requires us to study agency in a flow of time, over longer time periods (Grillitsch and Sotarauta Citation2020). This paper defines human agency within this temporal dynamism developed by Emirbayer and Mische (Citation1998).

In its simplest expression, agency can be seen in individuals’ everyday actions. Individuals’ capacity is intrinsically social and relational due to its construction in the engagement and disengagement with other actors in various contexts (Emirbayer and Mische Citation1998). Actors within the same context can therefore have different inherited powers based on their status. This influences their capacity both to act and have an effect (Coe and Jordhus-Lier Citation2011). Actors can strengthen their capacity through practical evaluation, and even actors with seemingly less power or obvious position can create effect (Ebbekink Citation2017). Individuals have limited information and with high cost of processing information on your own, they often act collectively (Bristow and Healy Citation2014). When scaling up from the individual level to the local level, there is a variety of actors who use their agency to influence local development. Firms are usually seen as important actors. However, as the firm consists of people, the firm itself should also be unpacked (Dawley Citation2014). Additionally, there are multiple non-firm actors such as Government authorities, support organizations and universities that can drive (and hinder) change (Hassink, Isaksen, and Trippl Citation2019; MacKinnon et al. Citation2019). Finally, a locality is made up by its residents who individually might not have enough agency to change local development. However, by joining forces, they can build capacity to create effect. Local actors, together with endogenous resources, can play important roles in creating positive change (Gunko et al. Citation2021). In old industrial places, that are often strongly shaped by their legacy (e.g. location, industrial specialization, local resources) and suffer from cognitive, functional and political lock-ins (Grabher Citation1993), opportunities for change or renewal are dependent on local actors’ willingness and ability to use their agency to recontextualize resources in alternative ways (Barca Citation2019). Lacking strong public actors, non-governmental actors can become drivers of change and challenge traditional power structures (Gunko et al. Citation2021).

Human agency can be unpacked using either types of actors or agency. I choose to use the agency-focused concepts change agency (Grillitsch and Sotarauta Citation2020) and reproductive agency (Bækkelund Citation2021; Jolly, Grillitsch, and Hansen Citation2020). The trinity of change agency identifies three types of agency that drive regional development (Grillitsch and Sotarauta Citation2020), which is often much needed in old industrial places. Innovative entrepreneurship describes actions aimed at seeking new path-breaking innovations that lead to new specializations or new transformations, which can break functional lock-ins. Place-based leadership captures actions aimed at gathering regional actors under joint goals. Institutional entrepreneurship captures actions that challenges existing rules and practices and aims at creating or transforming existing institutions, which can break cognitive or political lock-ins. When studying agency and actions, rather than actors, one can highlight that different actors can play different parts in development. Firms are most often connected with innovative entrepreneurship but can also operationalize other types of agency such as place-based leadership. Public actors on the other hand are most naturally linked to place-based leadership but can also act in other manners. As both Jolly, Grillitsch, and Hansen (Citation2020) and Bækkelund (Citation2021) point out, far from all actions in a locality intends to, or create change. Instead, much agency is attributed (consciously or unconsciously) to strengthen and maintain existing structures and specializations. Reproductive agency captures both actions that resist novel activities (Jolly, Grillitsch, and Hansen Citation2020) and stabilize acts through slow, incremental development (Bækkelund Citation2021). Change agency and reproductive agency should be observed alongside each other in a continuum, as actors change between the two in different arenas or time periods.

When agency and regional development are discussed, the end goal is often employment growth. To create long-term regional growth, regions must constantly seek new opportunities (Kurikka et al. Citation2022). From a critical realist perspective, actors always have agency and there are always opportunities available, whether you see them or not. As actors use their imagination and expectation to project and define future possibilities, these also become opportunities to test, adjust and realize. Opportunities are region-, time-, industry- and actor-specific. Different actors in a locality will perceive different opportunities due to their social filters (social conditions and social hegemonic ways) (Kurikka et al. Citation2022). However, I argue that just because actors have agency or opportunities in theory, it does not mean that it is experienced in practice. Old industrial places are often connected to negative lock-ins (Grabher Citation1993; Hassink Citation2010) that can create blinders blocking future projections. Periods of lock-ins occur (consciously or unconsciously) through reproducing existing structures and behaviour. I argue that these periods, are dominated by reproductive agency and lacks change agency partly due to a lack of perceived agency. When actors feel powerless and locked-in, it is difficult to perceive a different future, and hence no opportunities are discovered to act on.

2.3. How local culture and agency play together

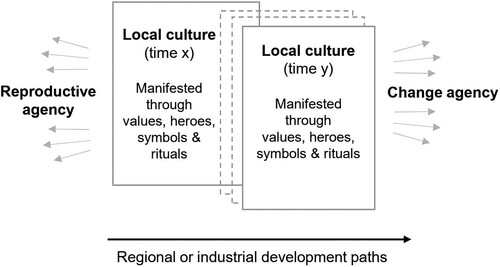

Local culture shapes the actors present in a place and their perceived agency. There is an inertia in local culture, and illustrates how local culture and agency slowly interact and evolve. Reproductive agency reproduces structures and development paths to stabilize the current, to resist novelty or due to a lack of perceived agency. As multiple actors act reproductively it pulls local culture to maintain its current form. When actors use change agency to transform structures or paths by acting on available opportunities, they instead pull local culture towards transformation. Changes in values, symbols, heroes and rituals, or changes in agency, suggest cultural change. This occurs in a flow of time, where industrial development paths are also evolving through actors’ engagement and structural developments. As both local culture and local agency are shaped by external factors, the ‘local’ should also be considered as placed in a multi-scalar network of other structures and actors.

Although old industrial places are often grouped together as one type of place, they can have different types of local culture and hence different agentic patterns. Over time, an entrepreneurial culture can foster more residents to become entrepreneurs through actors modelling entrepreneurial behaviour. The defining characteristics of entrepreneurs and entrepreneurial culture, suggest that residents in such a culture would be more prone to use change agency. Furthermore, this culture can further build local capacity by creating a larger pool of actors, thus reducing risk of long periods of perceived lack of agency. In a locality shaped by a company town culture there is instead a risk of a continuation of a few dominant actors, who through an existing power asymmetry, discourages change. A locality with this type of culture is therefore instead expected to be dominated by reproductive agency.

3. Methodology

The material basis for this paper is two in-depth case studies. While considered extreme cases, the two were chosen because of their long industrial tradition, similar timing in structural crisis and different ways of going forward. Kiruna was selected through a quantitative approach (see Grillitsch et al. Citation2021) and Borås through a qualitative approach to find a suitable complement. To capture local agentic patterns, data collection was guided by questions such as when was change agency exercised, why, by whom, with what effects and with what enablers and constraints. Data mainly consists of 38 semi-structured interviews (21 in Kiruna conducted December 2019–April 2020 and 17 in Borås conducted March 2021–August 2022) with key actors that have been active in the localities between 1990 and 2022. Informants were chosen because they represent positions or organizations that have the power to influence local development and/or culture. A total of 46 h of interviews was collected (38–125 minutes per interview) (see Appendix 1 for more information). An extensive pool of secondary sources (reports, books, strategy documents, statistics, news) was used for background and triangulation of results. Two small local workshops in December 2022 made it possible to verify and discuss findings with local actors. Due to geographical distance and the pandemic, 55% of the interviews were conducted online or by phone. The interviews were audio-recorded and summarized using inscriptions (covering quotes/themes/events/organizations discussed during interviews). Using two cases from the same nation, coincidingly going through structural crisis, avoid effects from differing formal regulations and planning systems. The local governments, with important roles for development, should formally have the same mandate to act, i.e. that they have the same legal framework to adapt to and the same responsibilities. However, their local conditions and capacities differ as they vary in population size (influencing e.g. income tax base and potential no. of people to engage in a locality) and hold different types of actors. Borås received a university college following the structural crisis which Kiruna did not. This can be considered a limitation to the study in terms of differing pre-conditions. Nevertheless, the actors’ agency can add up to a local agency greater than the sum of the individual actors.

The overall case studies were analysed using path tracing (Sotarauta and Grillitsch Citation2023). The narrative of the different local cultures was described in the interviews both in terms of how informants spoke of their own region, and their region in comparison to others. The local cultures have also been covered in previous studies (Ahnlund and Brunnström Citation1992; Brorström, Edström, and Oudhuis Citation2008; Edström et al. Citation2010). Following Kuckartz (Citation2013), the interview inscriptions were first coded (using CAQDAS) using a few main themes: the four manifestations of local culture and enablers and constraints of cultural change. Both semantic and latent codes were used. In the second round of coding, sub-themes were generated for deeper analysis. The data coded as rituals was too thin and has therefore been excluded from further analysis.

There are a few methodological challenges to consider in this paper. First of all, as Rodríguez-Pose (Citation2013, 1040) states, ‘ … measuring institutions – and, most of all, informal institutions – is virtually impossible’. Hofstede’s (Citation2001) manifestations of culture is used to manage this. Second, we need to consider ecological fallacy when studying local culture (Hofstede Citation2001). In practice this mean that it is not possible to draw conclusions about individuals based on what is known of the dominating culture. Residents do not need to belong to the dominant culture, neither do in-migrants automatically align with it.

4. Background

The municipalities of Borås and Kiruna are in different locations in Sweden (see ) and of different size. Kiruna is area wise very large but has a population of only 23,000 inhabitants and located in the periphery. Borås is smaller in terms of area, has a population of 114,000 residents, and located closer to a larger city. Yet, the distance has been described by informants as perceived as longer during parts of the study period. The cases are joined by their industrial heritage and through undergoing structural crisis during the same period and the same national political leadership. The textile and garment industry (TEKO) was during their heyday the largest industry for female industrial workers and the mining industry was equally important for male industrial workers.

4.1. Kiruna

When established in 1900, Kiruna was the first company town above the Arctic Circle in Scandinavia. It was planned as a model company town and the company built both housing and services. The company promoted education, morality and neatness through providing good schools, music and art events for workers and summer jobs for local children (Ahnlund and Brunnström Citation1992). Generations of Kiruna residents have worked in the company and the residents have developed a company town culture. Over the years the company and the municipality have also formed a strong bond, described in interviews as a marriage. The company became fully state-owned in 1976. The steel crisis in the 1970s forced the mining company to cut 2/3 of their staff between 1976 and 1983 and pushed it to upgrade their process and company brand from being just an extraction company into an iron ore processing company. The iron ore mining is conducted underground and highly technologically advanced. Today, the firm is one of the Swedish state’s most profitable companies.

In the shadow of the mine, two additional industries have grown. Space industry and research has developed, especially since the 1990s and related to Esrange Space Center. Although it is dependent on Kiruna’s location, it is mainly embedded in external networks and cooperation. Tourism, targeting mainly exclusive winter tourism, has also grown substantially with the establishment of the Icehotel in 1989 as a key event (Stihl Citation2022). Spurred by the crisis and the following depopulation, the municipality started supporting diversification of the local economy during mid-90s and early 2000s (Informant K18; Kiruna kommun Citation2003) through the reorganization of business support organizations. Nevertheless, the mine and Kiruna town have grown closely together, geographically as well. In 2004, the mining company informed the municipality that Kiruna town centre, with all establishments and 6000 residents would have to move due to land deformations from future underground mining. Today, 20 years later, the relocation is still ongoing. It has proven to be a highly complex process and has taken the municipality’s focus away from diversification efforts. The narrative of the move has been that it is essential, unstoppable and will bring a better and more sustainable future (Nilsson Citation2010). There has been very little opposition towards the move (Nilsson Citation2010), only some criticism voiced about moving practicalities. Nilsson (Citation2010) explains this as the continued strong company town culture creating a subordinate relationship between the dominant core firm, and residents and municipal government.

4.2. Borås

Borås is considered to have an entrepreneurial culture which explains the general economic success of the whole surrounding Sjuhärad region (Brorström, Edström, and Oudhuis Citation2008; Edström et al. Citation2010). The entrepreneurial spirit is often explained through the lean soil. Inhabitants became walking tradesmen (called ‘Knallar’) and craftsmen since they could not be farmers. The ‘Knalle spirit’ is a local cultural programming manifested in a tradition of entrepreneurship, a skillfulness in realizing good business ideas in a cost-efficient way, a tradition of independence and sense of responsibility, and a pride among entrepreneurs and policy makers in dealing with difficulties themselves. Traditionally, taking action and accomplishing results have been valued higher than education (Brorström, Edström, and Oudhuis Citation2008). Although entrepreneurs in general are expected to be risk-taking, entrepreneurs from Borås address risks with precautions, aiming for using their means in sensible ways. A negative side of the local culture has been the lack of networks and cooperation as well as the negative attitude towards higher education (Brorström, Edström, and Oudhuis Citation2008).

Manufacturing of textile and garments started almost 200 years ago in the area, initiating a large in-migration. The period following WWII was especially expansive. To be able to expand enough, firms recruited immigrants from abroad. During the 1960s, 80% of workers in the Borås region worked in TEKO (Borås industri- och handelsklubb Citation1999). But Swedish wage levels sent the industries into a series of crisis during the 1960s–1970s. To save the garment industry, the Swedish state formed a giant state-owned garment company from struggling firms. However, the protectionist approach was abandoned during the early 1980s. Following the crisis, the state further supported Borås by placing a university college (HEI) and the National Board for Measurement and Testing here.

Garment production was almost completely outsourced after the crisis. This reduced the labour force significantly and induced a large out-migration (population loss of 19% between 1970 and 1990 in Borås town). The local culture is used partly to explain why the industry still managed to survive after the crisis. As the large factory owners went bankrupt, new entrepreneurs could make use of the material resources and competencies freed by the crisis. Production was outsourced, but headquarters, design, marketing, value-added services and logistics stayed put. The School of Textiles (now department in HEI) is another part of the explanation. It was an important bearer of the TEKO brand and in the upgrading of TEKO paths in terms of skill-base development and R&D.

After the long crisis phase, the municipality struggled from 1985 (and 15–20 years onwards), with finding their way forward. During the 2000s there were several initiatives that altered local cooperation and strengthened the local self-esteem and TEKO paths further. Local businesses and the municipality started cooperating over spatial planning projects and sculptures. The municipality also built a new football arena (and the local team won the national league the following year). The industry and HEI started cooperating on developments related to Smart textiles and various TEKO actors (private businesses, HEI and public organizations) moved into an old textile factory to start building a triple helix. Together, these initiatives have paved a more positive way forward for Borås. Edström et al. (Citation2010) finds that the traditional ‘Knalle spirit’ is weakening. Instead, there are new local entrepreneurial role models who push for cooperation between the municipality, HEI, support structures and other firms. The next chapter will follow the changing nature of agency and local culture.

5. Findings

5.1. Changing agency

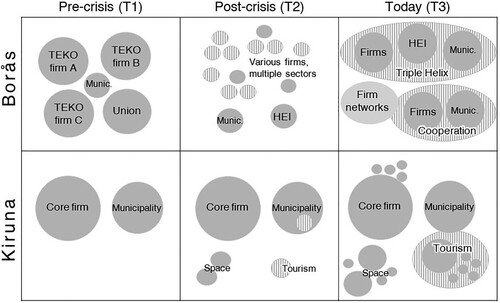

Local cultures’ influence on agency and distribution of power starts in the actors’ landscape. gives a schematic image of central actors engaged in local development in three phases: before structural crisis, the circa 20 years that followed, and today. The figure clearly shows that the structural preconditions gave the two places different starting points. In Borås (BT1), several strong firms had grown within textile and garment production. These set the agenda and pace of local development. The local unions also had strong power, e.g. in terms of controlling how many immigrants the firms employed. Large firms and unions acted independently to secure the future of the industry in Borås and resisted development of other industries through reproductive agency, supported by the municipality. Kiruna, like many other company towns, had only two dominant actors (KT1), the core firm and the municipality with the former as the strongest actor. Reproductive agency dominated the pre-crisis period to keep status-quo.

Figure 3. Active local actors during three phases. Grey fill = mainly reproductive agency. Grey hatching = change agency.

During the structural crisis, the Swedish state tried to save both industries through different protective and supportive measures. The state-owned mining firm in Kiruna survived, whereas many of the TEKO production firms in Borås did not. As the large firms went bankrupt and were sold off, pieces of infrastructure, brands, skills and competences, within business areas where Borås could still compete (such as design, marketing, logistics, distribution, computer systems and value-added services), were bought by other entrepreneurs (some former middle-management in the large firms). These formed a new net of smaller firms. These new entrepreneurs developed the firms, using change agency (innovative entrepreneurship), into new market niches, upgrades or made them branch out and diversify into both related and unrelated industries. Hence, during the second phase it is within the private firms that local agency is used to transform the locality. Additionally, a national strategy in the late 1970s was to develop university colleges outside traditional university cities. One was placed in Borås, and the existing local textile education was integrated into it. When considering key actors after the crisis (BT2), we find several firms within different industries and sectors growing in parallel, and the new HEI under development. However, following crisis and for the coming 15 years, the municipality lacked perceived room for agency and their agency was characterized by reproductive behaviour. They remained a weak actor in terms of business support and local development yet owned some of the old factory buildings. During the end of BT2, the planning office started seeing these buildings as resources that could be renewed and repurposed (cheaper than new constructions).

In Kiruna, the core firm and the municipality remained the dominant actors after crisis (KT2). Agency expressions was continuously dominated by reproductive agency aiming at protecting the mine. However, in the mid-90s the municipality actively engaged in change agency (place-based leadership) with the aim of supporting other industries through reorganizing business support structure (Kiruna kommun Citation2003). The crisis made it apparent for some people within the municipality that the dominant mine had left Kiruna vulnerable for external chocks. However, apart from a small firm growth within tourism, there was little change, and firms and industries continue to operate in separate silos. Residents were described to be suspicious towards entrepreneurship and reluctant to cooperate with each other (Informant K2; K18). During this period, the exclusive Icehotel was launched by an in-migrating entrepreneur. The innovation challenged local culture in terms of what could and should be done. A civil servant (K18) explained the resistance to Icehotel with:

Kiruna had a history of, since day one, social democratic rule and past social democracy. . . was not like. . . [today’s] social democracy. . . One did not build for tourism or shopping or anything else that was not available for all. You did not build or invest in something that was only available for a few .Footnote1

We must compete with incentive tourism. For those who want something very special, something that is very labour intensive, we need job opportunities . . . Not try to build a mass-tourism that is very low in labour intensity and where the revenue per tourist is low. We cannot manage it infrastructure wise. . . [Previously] the municipality owned the city hotel, ski facility, camping site, so, they owned all the [tourism] infrastructure themselves and it was a big leap to let it go and start thinking differently.

The two first phases left Kiruna and Borås with different sets of actors (BT3 and KT3). For Borås, the period of growing number of firms (BT2) can be seen as a capacity building phase. The crisis gave the municipality and its residents a lack of confidence, leaving the municipality passive in terms of business development. Yet, during the third phase they started engaging more in transformative agency. After 2000, the municipality experienced a general economic rise with a growing population and a rising national economic trend. This allowed them to invest in the physical space (a river-side piazza and a football stadium) and encourage cooperation with the local business life. When the municipality examined their business structure in 2005 (Borås stad Citation2005), they discovered that Borås’ firms were still successful within TEKO!

In 2006, a private developer, using innovative entrepreneurship and place-based leadership, wanted to create a centre for textile in one of the old factory buildings. The municipality encouraged this by moving their own textile-related organizations there, signing a long-term lease for the building and pushing the HEI to move in. The HEI was initially very reluctant to move since their activities extend beyond TEKO. Nevertheless, since its launch in 2013 the centre has developed into a functioning triple helix, which have strengthened local TEKO to claim a bigger role nationally and internationally (Informant B5; B11; B12). In this process, the municipality have acted uniting and enabling through place-based leadership. As for the firms, many of their leaders (both inside and outside TEKO) started taking a more active role in local development and invest financially in it (e.g. public sculptures) after the piazza-project and the public-private cooperation has deepened since. There are also several business networks (formal and informal) where entrepreneurs across industries and sectors meet and share ideas. These ‘form the basis for the direction in which things go’ (Informant B11). It is the same people in the different networks and ‘good ideas are discussed more’ (Informant B11). The municipality and representatives from local businesses have formed a ‘cooperation arena’ where they meet twice a year to push different important themes for Borås. The HEI encourages and supports development within TEKO industry through close cooperations with firms and business support organizations. The many networks enable local actors to join forces (fiscal resources, competence, networks) and act more united and forcefully when engaging both in change agency for developing Borås and reproductive agency for securing the set direction. ‘The community is a strong weapon’ (Informant B5). However, this also means that it is difficult for actors within the community to break away from the agreed direction (Informant B5; B16).

In Kiruna, the landscape of actors has expanded during the last period. Following (i) the municipal initiatives in early 2000s to support diversification and (ii) informal networks formed between the Icehotel and several other firms (acting as suppliers), a formal network/association was developed within the tourism industry to strengthen it. The association helps smaller firms develop but the industry still doesn’t act in unison. Their agency is scattered, especially in comparison to the mining company that has a strong united voice. Apart from the initial support to local businesses and support to the local tourism industry association, the municipality reproduces the mining company’s local power, through e.g. starting the moving process prior to the decision of the mine's expansion (causing the deformations). Additionally, the municipal’s room for agency is cropped as the national state owns the land surrounding the original town, and national regulation hinders them from selling it (to protect usufructuary rights of an indigenous group and other national interests). Yet, the state-owned mining company’s planned expansion is pushing for the move. Until 2022, local networks across industries have been scarce. The space industry/research continue to grow, but foremost engages in external networks. The mining company has local suppliers, but not organized in formal networks. The analysis shows large changes in the actor landscape, is it the same for local culture?

5.2. Changing culture

Based on previous research in Kiruna (Ahnlund and Brunnström Citation1992; Nilsson Citation2010) and Borås (Brorström, Edström, and Oudhuis Citation2008; Edström et al. Citation2010), we know that the two old industrial places have two different local cultures. However, from the literature we also know that local culture change (Hofstede Citation2001). lists key manifestations of local culture in the two cases (Appendix 2 gives a in-depth account of it). In Borås the local heroes have changed similarly to the change in actor landscape. Before the crisis, successful, self-made entrepreneurs were considered heroes together with the mythical ‘Knalle’. Today, local heroes come from a more diverse set of positions and organizations. What joins them is that they make use of their own capacities (internal and external networks, material resources, knowledge) with the intention of either supporting Borås (through showcasing that successes can still be built in Borås or investing in local initiatives) or promoting cooperation (through initiating or engaging in the different formal and informal networks). But the heroes are not only a few individuals. Informants describe a fine network of entrepreneurs that assist new entrepreneurs within networks and through financial support. One entrepreneur described how the local culture has transformed from the self-made man into appreciating ‘we-made’ success (Informant B16). An interesting detail is that several key actors mentioned during interviews are in-migrants or second generation living in Borås. This shows that you do not need deep roots in the locality to be let in.

Table 1. Mapping of manifestations of culture (extended version with references in Appendix 2).

In Kiruna, the company town culture has been sustained through reproductive agency keeping the company, and its CEOs, as heroes. However, a broader set of heroes exist today. The first company patron remains actively in memory as his name is given to buildings and educational programme, etc., but he is no longer seen as a hero. It is instead entrepreneurs within tourism, who challenged the local culture and built successful businesses outside mining industry, that model behaviour. Noteworthy is that the most frequently mentioned individuals are not originally from Kiruna, but in-migrants. Another interesting observation is that the Kiruna-material also includes anti-heroes, i.e. policy makers that aim to challenge the local culture, but in ways that are not accepted locally. The mining company’s ability to act as one body enforces its power locally. No other actor or network manages to do the same. Instead, others act scattered in smaller groupings with less powerful agency.

The heroes mentioned in Borås, are to a large extent regarded as heroes due to their central position in creating new symbols for Borås. Since early 2000, it has been a local strategy to work with creating physical symbols to instil pride in residents. This work has also been a way for local actors to improve cooperation across organizational boundaries. The municipality took the lead (initiative and financial resources) in the first project (a piazza). The creation of symbols that followed were either funded by private (old and new money) or public funds. What unites them is that they were created through joint efforts, and that private-public cooperations have built further cooperations and developed new formal networks. Through forming a joint agenda and joining forces, the local agency has been strengthened. The informants speak of the symbols as important for reproducing the narrative of the strong, independent and entrepreneurial Borås. This can be exemplified with the new football stadium, that the municipality chose to build cheaply without any sponsorship to be able to name it Borås Arena (and not a company name). A local evaluation showed that the investments in symbols had, at least temporary, an effect on the residents attitude towards their own city (IMA Marknadsutveckling Citation2011). A former civil servant (B17) expressed that ‘a couple of successful projects is enough’ to start turning a negative trend. The informants seem to agree on that the different symbols have been important for lifting Borås from a downward spiral with little perceived agency and a negative heritage, into a proud municipality ready to act. The development cannot be attributed to a particular event but rather described as that ‘all the pieces in a puzzle finally fell into place’ (Informant B13) around 2005–2010. However, the symbol of the crisis, is still lingering and the negative effects it had on the residents’ everyday life. A politician (B8) expressed that the crisis is a bond that encourages local actors to find consensus, to avoid a new crisis. However, the politician added that the bond weakens with new generations.

The symbols in Kiruna show the inertia of local culture. The stable symbols are related to the mine, where the company through branding and projects related to the move reproduce existing symbols with only incremental change. The clearest symbol of change is the Icehotel and its founder, symbolizing that a different future is possible outside mining and challenging previous suspiciousness of entrepreneurship. Compared to Borås there is less changes in symbols, they are of a different kind (less material) and informants speak less unanimous of them. Several of the symbols have multiple meanings, highlighting the complexities and conflicts inherited in the place, such as the pros and cons of the mining company and competing interests over the surrounding landscape. Some of these conflicts can be explained by the existence of multiple local cultures. An indigenous group lives in the area. This has created tensions dating back to the establishment of the mine. With the new town centre officially opening in September 2022, a long-awaited milestone, the local workshop in December 2022 indicated that the new centre is becoming a new symbol.

In Borås, the informants agree that the changes in heroes and symbols have influenced the values forming the local culture. The manifestations have positively changed how residents value Borås; it has instilled pride and the best thing with Borås is no longer ‘the train to Gothenburg’ (Informant B10). Although there has been national support over the years (e.g. establishment of HEI), the narrative of that Borås needs, and can, make it on its own, remains. This is perhaps best exemplified with the report from 2005 (Borås stad Citation2005, 49) where the municipality highlight their agency when concluding, ‘We must remember that it is us that create the future’. The ability is explained by the entrepreneurial Borås. The description and the label of what this means has however changed from the ‘Knalle spirit’, into a more cooperating and networking culture.

In Kiruna, there are several key characteristics of the company town culture that remains, but there are also changing values such as a growing appreciation of entrepreneurship and cooperations. As the tourism industry has grown, so has the local industry association. One of its members (Informant K19), described how the opportunity to cooperate between firms has always been there, it was just never perceived. The association became an ‘eyeopener’ (Informant K19). The initial moving process instead exemplifies the company town culture as the municipality, hindered by formal constraints set by at the national level, waited for a long time for the national government to step-in and assist in the complex process. But assistance never came. The municipality’s agency is cropped from several angles by the state. However, the lack of state-support has forced the municipality to discover and use their existing agency to a larger extent, increasing their power. Additionally, this is also where increased cooperation can be found. Despite these changes, local culture keeps reproducing support for the company and other actors keep acting in smaller groupings, instead of joining agency.

6. Conclusions

Understanding agency in old industrial places is considered an important step to understand why places with seemingly similar pre-conditions develop differently (Blažek and Květoň Citation2022). Additionally, previous research (Marques and Morgan Citation2021; Rekers and Stihl Citation2021) has indicated that institutions are an important piece of the puzzle of regional development. In this paper local culture, an informal institution, and its relation to agency, has been under scrutiny in two case studies: Borås, ascribed as an entrepreneurial place, and Kiruna, a company town. The paper aimed to answer the following research questions: How do different local cultures affect change agency and reproductive agency? How have local cultures and agency patterns changed over time?

Previous research on entrepreneurs and entrepreneurial culture (see e.g. Beugelsdijk Citation2007; Fritsch and Wyrwich Citation2014; Wigren-Kristoferson et al. Citation2022) creates an expectation that inhabitants in such a culture, would be more likely to use change agency to transform the place, while continuously reproducing entrepreneurial behaviour. Research on company towns (see e.g. Isacson Citation1997; Moonesirust and Brown Citation2021) instead indicated that inhabitants in company towns would mainly use reproductive agency to support the core firm and its role in the community. The analysis showed that a broad brushed conclusion could verify these expectations, but that the real answer is more complex.

The two cultures created different preconditions in the local actors’ landscape and following the structural crisis the differences grew even bigger. Borås already had a greater number of actors and with an entrepreneurial culture, the resources set free by the crisis were reused and repurposed by new entrepreneurs using innovative entrepreneurship. The number of actors increased, as did local capacities. In Kiruna, the mining firm and the municipality were considered the main actors both prior to the crisis and after. However, the mining firm’s power is stronger and continuously reproduced locally. It should be noted that the two industry types in the two cases create different pre-conditions for transformation. The labour intensive TEKO industry is more flexible than the capital-intensive mining industry with large sunk costs (Hu and Hassink Citation2015). Nevertheless, based on the analysis we cannot conclude that an entrepreneurial culture creates more opportunity for change agency for all its inhabitants. The material shows actor-specific differences. In both cases the municipalities/local governments remained cognitively locked-in for years after the crisis expressed through a lack of perceived agency. So, while new entrepreneurs in Borås activated their change agency, the municipality passively reproduced existing structures. This finding resonates with Blažek and Květoň (Citation2022), who also find a time-lag between firms dealing with a structural change and more pervasive change on societal level. Kiruna municipality start breaking the lock-in earlier than Borås and start working towards diversification during mid-90s. There, the restructuring had created less change in the industry structure and actor landscape. On the other hand, once Borås municipality started using place-based leadership, their entrepreneurs had built a larger capacity which could be put into play through different public-private initiatives. Today, actors in Borås have a joint narrative of fixing problems themselves and their local agency come across as stronger and more united than Kiruna’s.

The unity in Borås can partly be explained by the change in their local culture. Although an overall entrepreneurial culture remains, a new type of heroes (who additionally model cooperation and networking) and a new set of symbols have transformed the local culture into being more cooperative and prouder over the city and its heritage. Kiruna has experienced less cultural transformation but is not without change. Innovative entrepreneurship followed by institutional entrepreneurship within the tourism industry have created more local acceptance for entrepreneurship. Furthermore, the lack of state support with the complex town move in the end instilled more perceived room for agency in the local municipality. Yet, apart from the core firm, the actors in Kiruna still act less united, making their agency (and hence their power) more scattered.

To conclude, old industrial places often suffer from different structural constraints and lock-ins, and these influence opportunities for change agency in both local cultures. The entrepreneurial culture in Borås creates more opportunity for change agency than the company town culture in Kiruna, but the opportunities for change agency are actor-specific. Reproductive agency is found in both cases to stabilize local culture, but hinders institutional change to a greater extent in the company town culture. Still, local culture has transformed in both, and this has opened for more opportunity for change agency as the places transforms further away from lock-ins and the restructuring phase. Hence, Borås keeps on spinning and Kiruna keeps on digging deeper, both as a result of local and external actors’ engagement. The two cases show how different local cultures can be in old industrial places and how this influence agentic patterns in them. Future research is therefore needed to understand this diverse set of places better and adapt policy recommendations accordingly.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (36.1 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (18.2 KB)Acknowledgements

First of all, I want to thank the informants for sharing their time and their stories. I also wish to thank Markus Grillitsch, Brita Hermelin, Ann-Helene Isherwood, Josephine Rekers and two anonymous reviewers for comments on earlier draft of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 All quotes are translated from Swedish into English by the author.

References

- Ahnlund, M., and L. Brunnström. 1992. “The Company Town in Scandinavia.” In The Company Town: Architecture and Society in the Early Industrial Age, edited by J. Garner, 75–108. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Andersson, M., and S. Koster. 2011. “Sources of Persistence in Regional Start-up Rates--Evidence from Sweden.” Journal of Economic Geography 11 (1): 179–201. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbp069.

- Bækkelund, N. 2021. “Change Agency and Reproductive Agency in the Course of Industrial Path Evolution.” Regional Studies 55 (4): 757–768. doi:10.1080/00343404.2021.1893291.

- Barca, F. 2019. “Place-based Policy and Politics.” Renewal (0968252X) 27 (1): 84–95.

- Beugelsdijk, S. 2007. “Entrepreneurial Culture, Regional Innovativeness and Economic Growth.” Journal of Evolutionary Economics 17 (2): 187–210. doi:10.1007/s00191-006-0048-y.

- Blažek, J., and V. Květoň. 2022. “Towards an Integrated Framework of Agency in Regional Development: The Case of Old Industrial Regions.” Regional Studies, doi:10.1080/00343404.2022.2054976.

- Borås industri- och handelsklubb. 1999. “Borås industri- och handelsklubb 50 år: historia, nutid, framtid.” Klubben.

- Borås stad. 2005. Borås Näringslivs struktur och framtida utmaningar. Borås Stad.

- Borges, M., and S. Torres. 2012. “Company Towns: Concepts, Historiography and Approaches.” In Company Towns. Labor, Space and Power Relations Across Time and Continents, edited by M. J. Borges, and S. B. Torres, 1–40. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bristow, G., and A. Healy. 2014. “Regional Resilience: An Agency Perspective.” Regional Studies 48 (5): 923–935. doi:10.1080/00343404.2013.854879.

- Brorström, B., A. Edström, and M. Oudhuis. 2008. Knalleandan - drivkraft och begränsningar (Vetenskap för profession, Issue 3). Borås: University of Borås.

- Bursell, B. 1997. “Bruket och bruksandan.” In Bruksandan - hinder eller möjlighet? Vol. 1, edited by E. Bergdahl, M. Isacson, and B. Mellander, 10–20. Smedjebacken: Ekomuseum Bergslagen.

- Byrne, D. 2002. “Industrial Culture in a Post-Industrial World: The Case of the North East of England.” City 6 (3): 279–289. doi:10.1080/1360481022000037733.

- Coe, N., and D. Jordhus-Lier. 2011. “Constrained Agency? Re-Evaluating the Geographies of Labour.” Progress in Human Geography 35 (2): 211–233. doi:10.1177/0309132510366746.

- Dawley, S. 2014. “Creating New Paths? Offshore Wind, Policy Activism, and Peripheral Region Development.” Economic Geography 90 (1): 91–112. doi:10.1111/ecge.12028.

- Ebbekink, M. 2017. “Cluster Governance: A Practical Way out of a Congested State of Governance Plurality.” Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 35 (4): 621–639. doi:10.1177/0263774X16666079.

- Edström, A., T. Ljungkvist, M. Oudhuis, and B. Brorström. 2010. Knalleandan i gungning? (Vetenskap för profession, Issue 14). Borås: University of Borås.

- Emirbayer, M., and A. Mische. 1998. “What Is Agency?” American Journal of Sociology 103 (4): 962–1023. doi:10.1086/231294.

- Forsberg, G. 1997. “Reproduktionen av den patriarkala bruksandan.” In Bruksandan - hinder eller möjlighet? Vol. 1, edited by E. Bergdahl, M. Isacson, and B. Mellander, 59–64. Smedjebacken: Ekomuseum Bergslagen.

- Fritsch, M., and M. Wyrwich. 2014. “The Long Persistence of Regional Levels of Entrepreneurship: Germany, 1925-2005.” Regional Studies 48 (6): 955–973. doi:10.1080/00343404.2013.816414.

- Garner, J. 1992. “Introduction.” In The Company Town: Architecture and Society in the Early Industrial Age, edited by J. Garner, 75–108. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Gertler, M. 2018. “Institutions, Geography, and Economic Life.” In The New Oxford Handbook of Economic Geography, edited by G. L. Clark, M. P. Feldman, M. S. Gertler, and D. Wójcik, 230–242. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Grabher, G. 1993. “The Weakness of Strong Ties. The Lock-in of Regional Developments in the Ruhr Area.” In The Embedded Firm. On the Socioeconomics of Industrial Networks, edited by G. Grabher, 255–277. London & New York: Routledge.

- Grillitsch, M., M. Martynovich, R. Dahl Fitjar, and S. Haus-Reve. 2021. “The Black Box of Regional Growth.” Journal of Geographical Systems 23: 425–464. doi:10.1007/s10109-020-00341-3.

- Grillitsch, M., J. Rekers, and M. Sotarauta. 2021. “Investigating Agency: Methodological and Empirical Challenges.” In Handbook on City and Regional Leadership, edited by M. Sotarauta, and A. Beer, 302–323. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Grillitsch, M., and M. Sotarauta. 2020. “Trinity of Change Agency, Regional Development Paths and Opportunity Spaces.” Progress in Human Geography 44 (4): 704–723. doi:10.1177/0309132519853870.

- Gunko, M., N. Kinossian, G. Pivovar, K. Averkieva, and E. Batunova. 2021. “Exploring Agency of Change in Small Industrial Towns Through Urban Renewal Initiatives.” Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 103 (3): 218–234. doi:10.1080/04353684.2020.1868947.

- Hassink, R. 2010. “Locked in Decline? On the Role of Regional Lock-ins in Old Industrial Areas.” In The Handbook of Evolutionary Economic Geography, edited by R. Boschma, and R. Martin, 450–468. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Hassink, R., A. Isaksen, and M. Trippl. 2019. “Towards a Comprehensive Understanding of New Regional Industrial Path Development.” Regional Studies 53 (11): 1636–1645. doi:10.1080/00343404.2019.1566704.

- Hassink, R., and M. Kiese. 2021. “Solving the Restructuring Problems of (Former) Old Industrial Regions with Smart Specialization? Conceptual Thoughts and Evidence from the Ruhr.” Review of Regional Research 41 (2): 131–155. doi:10.1007/s10037-021-00157-8.

- Hayton, J., and G. Cacciotti. 2013. “Is There an Entrepreneurial Culture? A Review of Empirical Research.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 25 (9-10): 708–731. doi:10.1080/08985626.2013.862962.

- Hofstede, G. 2001. Culture's Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviours, Institutions, and Organizations Acress Nations. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

- Hu, X., and R. Hassink. 2015. “Explaining Differences in the Adabtability of Old Industrial Regions.” In Routledge Handbook of Politics and Technology, edited by U. Hilpert, 162–172. London & New York: Routledge.

- IMA Marknadsutveckling, A. 2011. Attitydmätning (Självbild). Borås: Borås stad.

- Isacson, M. 1997. “Bruksandan - hinder eller möjlighet?” In Bruksandan - hinder eller möjlighet?. Vol. 1, edited by E. Bergdahl, M. Isacson, and B. Mellander, 120–132. Smedjebacken: Ekomuseum Bergslagen.

- Jolly, S., M. Grillitsch, and T. Hansen. 2020. “Agency and Actors in Regional Industrial Path Development. A Framework and Longitudinal Analysis.” Geoforum 111: 176–188. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.02.013.

- Kiruna kommun. 2003. Lokalt tillväxtprogram för Kiruna kommun 2003-2007. Kiruna: Kiruna kommun.

- Kuckartz, U. 2013. Qualitative Text Analysis: A Guide to Methods, Practice & Using Software. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Kurikka, H., J. Kolehmainen, M. Sotarauta, H. Nielsen, and M. Nilsson. 2022. “Regional Opportunity Spaces – Observations from Nordic Regions.” Regional Studies, 1–13. doi:10.1080/00343404.2022.2107630.

- MacKinnon, D., S. Dawley, A. Pike, and A. Cumbers. 2019. “Rethinking Path Creation: A Geographical Political Economy Approach.” Economic Geography 95 (2): 113–135. doi:10.1080/00130095.2018.1498294.

- Marques, P., and K. Morgan. 2021. “Getting to Denmark: The Dialectic of Governance & Development in the European Periphery.” Applied Geography 135), doi:10.1016/j.apgeog.2021.102536.

- Moonesirust, E., and A. Brown. 2021. “Company Towns and the Governmentality of Desired Identities.” HUMAN RELATIONS 74 (4): 502–526. doi:10.1177/0018726719887220.

- Nilsson, B. 2010. “Ideology, Environment and Forced Relocation: Kiruna – a Town on the Move.” European Urban and Regional Studies 17 (4): 433–442. doi:10.1177/0969776410369045.

- Porteous, J. 1970. “The Nature of the Company Town.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 51: 127–142. doi:10.2307/621766.

- Rekers, J., and L. Stihl. 2021. “One Crisis, One Region, Two Municipalities: The Geography of Institutions and Change Agency in Regional Development Paths.” Geoforum 124: 89–98. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.05.012.

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. 2013. “Do Institutions Matter for Regional Development?” Regional Studies 47 (7): 1034–1047. doi:10.1080/00343404.2012.748978.

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. 2020. “Institutions and the Fortunes of Territories†.” Regional Science Policy & Practice 12 (3): 371–386. doi:10.1111/rsp3.12277.

- Saxenian, A. 1996. “Inside-Out: Regional Networks and Industrial Adaptation in Silicon Valley and Route 128.” Cityscape (Washington, DC) 2 (2): 41–60.

- Sotarauta, M., and M. Grillitsch. 2023. “Path Tracing in the Study of Agency and Structures: Methodological Considerations.” Progress in Human Geography 47 (1): 85–102. doi:10.1177/03091325221145590.

- Stihl, L. 2022. “Challenging the set Mining Path: Agency and Diversification in the Case of Kiruna.” The Extractive Industries and Society 11, doi:10.1016/j.exis.2022.101064.

- Stuetzer, M., D. Audretsch, M. Obschonka, S. Gosling, P. Rentfrow, and J. Potter. 2018. “Entrepreneurship Culture, Knowledge Spillovers and the Growth of Regions.” Regional Studies 52 (5): 608–618. doi:10.1080/00343404.2017.1294251.

- Stuetzer, M., M. Obschonka, D. Audretsch, M. Wyrwich, P. Rentfrow, M. Coombes, L. Shaw-Taylor, and M. Satchell. 2016. “Industry Structure, Entrepreneurship, and Culture: An Empirical Analysis Using Historical Coalfields.” European Economic Review 86: 52–72. doi:10.1016/j.euroecorev.2015.08.012.

- Wigren-Kristoferson, C., E. Brundin, K. Hellerstedt, A. Stevenson, and M. Aggestam. 2022. “Rethinking Embeddedness: A Review and Research Agenda.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 34 (1-2): 32–56. doi:10.1080/08985626.2021.2021298.