ABSTRACT

In recent decades, attention to the role of actors in regional development has shifted from the role of ‘formal and collective’ actors to the role of individuals in change agency. In doing so, individuals mobilize their capacity to act, which comprises the total volume of resources accumulated over the course of their life. However, there is a lack of studies focusing on how such capacity is then mobilized for change agency. Therefore, this study seeks to reveal the patterns of how selected agents have used their capacity for change agency and how this is implemented in the specific spatio-temporal setting of an old industrial region. Based on the results of 64 semi-structured interviews conducted with agents of change and local informants in four old industrial towns in Czechia, we identified five basic types of how resources are combined and used during the implementation of change agency – change agencies driven by embodied cultural capital, by bonding social capital, by economic capital, with support from public institutions and those accelerated by symbolic capital.

Introduction

Despite the efforts of the European Union's cohesion policies, peripheral or old industrial regions (OIR) are still lagging behind metropolitan areas, and the gap between them is growing (e.g. Kinossian Citation2019). The ‘backwardness’ of OIRs is generally caused by their specific historical, economic and social conditions that hinder change, but there is evidence that individual OIRs have different capacities to adapt to new social conditions, global market opportunities and the decline of key industries, as demonstrated by the success stories of some old industrial towns and regions (e.g. Roberts, Collis, and Noon Citation1990; Gómez Citation1998; Benneworth and Hospers Citation2006). From this perspective, the role of local social, economic and material factors is crucial for explaining of different development trajectories in OIRs (Pike, Rodríguez-Pose, and Tomaney Citation2007). Unfortunately, the role of local actors in constructing of new development paths at the micro level and their influence on economic diversity in places with similar structural preconditions is not sufficiently explained (Boschma Citation2017).

Until recently, in contrast to transition studies (which focused on the emergence of path-breaking activities), the evolutionary economic geography (EEG) literature focused on the continuity, path dependence (MacKinnon et al. Citation2019) and various forms of lock-in hindering the development of OIRs (Hassink Citation2007). However, in last years, we can observe a shift towards the role of individuals, their collectives and their ability to dismantle old structures and institutions under the label of human change agency (Grillitsch and Sotarauta Citation2020; Grillitsch, Rekers, and Sotarauta Citation2019). Such or derived concepts, were then empirically verified at the regional scale (e.g. Bækkelund Citation2021; Blažek and Květoň Citation2022; Grillitsch et al. Citation2022a and Citation2022b) and sporadically at the local scale (Rekers and Stihl Citation2021), but mostly focused on the role of local governance and firms.

Only limited space has been devoted to the examination of the real bearers of change agency – individual agents possessing different assets and characteristics that are important for carrying out change agency. Therefore, our research integrates the issue of individual capacities to act with the discussion on regional development and change agency. Thus, it focuses on the resources that build the individual capacity to change and their use in the performed change agency. In contrast to Grillitsch and Sotarauta (Citation2020), who divide transformative agency into three fundamental categories according to the type of change agency, we aim to propose an empirically grounded typology of change agencies based on the underlying resources that enable such an individual action. In doing so, we highlight also other important attributes of change agency in relation to the individual's capacity to change. In previous research, which can be regarded as complementary to this study, we have focused on the questions of what types of resources obtained through interaction with the public sector are mobilized by agents of change (Píša Citation2023) and what motivates these agents to perform a given change agency (Píša and Hruška Citation2023). It is clear from the results of both, that the capacity to act stems from the different forms of capital described by Bourdieu (Citation1986).

Therefore, in the context of previous arguments and discussions on human change agency in local/regional development, the main research questions of this study are as follows:

- How is the capacity to act of individuals constructed?

- How is this capacity mobilized in the specific spatio-temporal setting (in the interaction with other individuals and locally specific assets)?

Compared to other studies, which usually focus on economic changes in OIRs and are derived from the conceptual strand of the EEG (e.g. Boschma and Martin Citation2007), we take a broader view of development, going beyond the economic sphere to include social, political and cultural dimensions (Morgan Citation2004). Therefore, inspired by Pike, Rodríguez-Pose, and Tomaney (Citation2007), we combine these key pillars that influence the quality of life of individuals with the issue of regional economic development in order to identify agents of change in the specific context of four OIRs in Czechia.

Change agency and new development paths

This study is concerned with the concept of agents in the sense of human agency, which is the ability of people to act that emerges from conscious intentions and results in the form of observable effects in the human world (according to Gregory et al. Citation2011, 347). Although often attributed to individuals, many authors emphasize the social nature of agency and the direct influence of a community, or indirect influence trough formal and informal institutions constructed with a long-term view by a whole range of social relations, on the form and intensity of the agency (Emirbayer and Mische Citation1998). Thus, the discussion on human (change) agency has been heavily influenced by structural and institutional approaches.

According to Giddens (Citation1984), agency is primarily understood as repetitive, uncreative and routinized behaviour that arises from the trust in the stability of social processes. In this perspective, actors act consciously and reflexively because they are knowledgeable (in the sense of experience and tacit knowledge) and capable (have the power) to act. Knowledgeability enters into the processes of reproducing and transforming of structures (the structuration), which is often seen as an unintended outcome of routinized action (Giddens Citation1984). This view is often shared by regional development sciences, where human agency has a more reproductive character, contributing to the preservation of the original structures (Bækkelund Citation2021; Coe and Jordhus-Lier Citation2011; Blažek and Květoň Citation2022) and reproducing the path dependency (Martin and Sunley Citation2006; Morgan Citation2013) that is rigid to change, especially in the context of OIRs.

Conversely, other authors emphasize agency as a capacity to intervene (MacKinnon et al. Citation2019), which can also disrupt existing structures and institutions. In this more possibilist approach, actors should not be understood merely as bearers of such a social structure (consisting of routines and often institutionalized behaviour), because they have the power to change its conditions (Chazel and Boudon Citation1992). Thus, from a planning and also research perspective, it is necessary to look for actors who, despite structural preconditions (Rodríguez-Pose Citation2013), bring change, novelty or innovation to their locality. This type of agency then deviates from the expected path at the regional scale (Garud and Karnøe Citation2001; Grillitsch, Rekers, and Sotarauta Citation2019). Therefore, it is important to focus on change agency ‘which aims or results to break with existing regional development paths’ (Grillitsch, Rekers, and Sotarauta Citation2019, 6) or transformative agency (e.g. Coe and Jordhus-Lier Citation2011), which is a crucial force that transforms an old development path into a new one.

CA does not occur randomly but due to a constellation of many factors that create specific temporal and spatial contexts (MacKinnon et al. Citation2019) in which change is possible. Such situations can be considered as crises (economic recession-see Friedman Citation2009, COVID-19 pandemic, etc.), critical junctures (Green Citation2016), windows of locational opportunity (Boschma Citation1997), or locally-, time-, and agent-specific opportunity spaces (Grillitsch and Sotarauta Citation2020). Thus, human agency can be understood as people's adaptation to new circumstances (Walker et al. Citation2004), and change agency as the ability to identify a need or an opportunity for change, the belief that the change is possible, the willingness to pursue it, and the availability and ability to use resources appropriately (Brown and Westaway Citation2011).

Capacity to act

In order to initiate and implement change processes, an individual must have a sufficient capacity to act. Such a capacity could be defined as an attribute of an individual that depends on tangible (financial and material resources) and less tangible (knowledge and skills) elements. Such an individualistic definition must be extended by the enabling context, such as the institutional environment, social networks and political support (Brown and Westaway Citation2011). The capacity to act is then constructed by the assets accumulated over the individual's life course, which ‘can be viewed as a multilevel phenomenon, ranging from structured pathways through social institutions and organizations to the social trajectories of individuals and their developmental pathways’ (Elder Citation1994, 5).

We therefore see the individual capacity to act as constructed at the intersection of the individual and the social. To better describe this, and to provide an analytical framework for our study, in the following sections, we build on the concepts of cultural, social and related economic and symbolic capital, derived from the work of Bourdieu (Citation1986). In our study, Bourdieu’s concepts are approached as an organizing framework rather than a strict template; therefore, his concepts of capital are enriched by the insight of other authors.

Bourdieu (Citation1986) distinguished three basic types of cultural capital. The following section focuses on only two of these, as objectified cultural capital is not relevant to our study. First, embodied cultural capital refers to an individual's character and way of thinking, which is influenced by consciously acquired knowledge, or by knowledge, norms, attitudes and experiences acquired tacitly and cumulatively (in the long run) through socialization (based on elementary social capital through family or everyday social interactions). Such cultural capital then secondarily influences the agent's attitudes and behaviour towards the environment. The source of knowledge may be formal education, but its use or access to it is influenced by the inherited social status of the agent and the symbolic capital derived from it. Embodied cultural capital is similar to human capital, which is often used in the literature on regional (economic) development and focuses on characteristics useful for economic exploitation (knowledge, skills, education and experience, e.g. Cambridge dictionary Citation2020), although other authors add more innate characteristics, such as flexibility, creativity or motivation (Maskell and Malmberg Citation1999). Human capital in the form of acquired education can then be used economically and socially to a certain extent, because institutionalized forms of human capital (such as certified education) improve the social status of individuals and their prospects in the labour market (as summarized by Aziz Citation2015).

Second, institutionalized cultural capital includes officially recognized embodied cultural capital that allows individuals to assess and compare their knowledge and skills. The institutionalization of cultural capital thus serves to some extent the objective assessment of these capabilities, because it is at least partially guaranteed by law and similar instruments. An example of this is formal education, which is sanctified by a diploma, an academic title or a specific position in the hierarchy of an organization (e.g. firms and public institutions).

Social capital, which includes social norms (informal institutions), values, trust and social networks, results from an individual's institutionalized ties within the social network. Van Deth (Citation2008) divided social capital into structural and cultural aspects. The structural aspect relates to the number of ties an individual has within various social networks, while the cultural aspects refer to their quality. These qualitative characteristics include the trust between people and institutions and the nature of regional social norms and values, such as identity and tolerance.

Social capital can be seen as individual and collective assets (Stachová Citation2008). First, its individualistic view understands social capital as a network of contacts that can be utilized by an individual for personal benefit (Bourdieu Citation1986). Its intensity is therefore related to the cultural and economic capital of individuals, since some ties help to multiply these individually owned capitals. In the case of more institutionalized groups, the social capital resulting from the combination of the capabilities of its members is often concentrated in the hands of leaders who are empowered to act on behalf of the whole group (Bourdieu Citation1986). Thus, in terms of the distinction between structure and agency, social capital can be understood as the ability of individuals to orient themselves within the structure (Coleman Citation1988). Such empowered individuals enjoy the benefits of symbolic capital (recognition, esteem, prestige and power), but its extent may be the result of other personal attributes, such as race, ethnicity and gender (Bourdieu Citation2001).

Second, through the lens of regional development, the social and spatial perspectives need to be considered, as social capital is a feature of the social structure (e.g. norms, trust and networks) that affects the coordination of the agency across society. Putnam (Citation1995) defined bonding and bridging social capital. The former can be thought of as internal and intensive relationships, very often at the lowest spatial level (e.g. household and neighbourhood). The latter is less intensive and frequent, but contributes to the transfer of resources between bounded structures. The ability to combine external experience with strong regional knowledge held by local agents (Fitjar and Rodríguez-Pose Citation2017) offers good potential for introducing change (Sotarauta and Mustikkamäki Citation2014). A high level of trust can increase one's symbolic capital, which is expressed by a superior position within a given hierarchy. The power gained in this way can significantly multiply the impact of their agency. However, this power may be determined not only by the position of the actor (e.g. the head of a firm or a political leader), but also by the ability to promote actor-specific (individual and collective) interests within networks of actors and spatial and social structures of different scales (Griffin Citation2012).

Cultural and social capital are, to a considerable extent interrelated and inseparable (e.g. Pileček, Chromý, and Jančák Citation2013; Coleman Citation1988). For example, the basic sources of embodied cultural capital, such as family and elementary education, which influence the possibilities of further education and the development of the actor, are, to a large extent, decisive for the social capital of an individual and vice versa (Teachman, Paasch, and Carver Citation1997). As with other forms of capital, Bourdieu acknowledged that both economic and symbolic capital are the result of the possession of social and cultural capital.

Study area and methodology

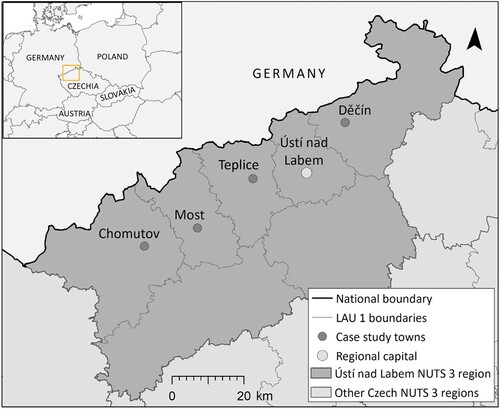

We selected four old industrial towns located in the NUTS III Ústí nad Labem Region in Czechia for our research. Chomutov, Most, Teplice and Děčín (see ) have a similar population of 49,000–66,000 and occupy the same position in the settlement and administrative hierarchy. A common feature of all these towns is their strong industrial specialization inherited from the socialist era (1948–1989). The economy of the Ústí nad Labem Region was dominated by lignite mining (Chomutov, Most and Teplice), textiles (Děčín), glass industry (Teplice) and non-ferrous metallurgy (Chomutov and Děčín). On the other hand, the economic profile of Teplice and Děčín has been diversified by services: Teplice is known as a spa town and Děčín as an important transport hub. The regional deindustrialization accelerated significantly in the early 1990s as a result of the retreat from the state socialism and integration into the global market economy. The decline of key industries led to radical increase in economic (e.g. high unemployment rate which has gradually fallen to the current level of 5% – despite this, the problem of a lack of skilled jobs persists), social (e.g. growing social exclusion and brain drain) and environmental (e.g. urban decay and the emergence of brownfield sites) problems. As a result, all the towns under investigation and the whole Ústí nad Labem Region might be labelled as an old industrial region (Koutský Citation2011; Blažek and Květoň Citation2022) with typical problems and development barriers and strong political and cognitive lock-in (Grabher Citation1993; Hassink Citation2007).

To identify the ‘agents of change’, we proposed a framework based on the negatively perceived aspects of the structure of OIRs. Thus, they were identified as people whose activities could be described as change agency as they address local problems and help their locality to find a new development path. From an economic perspective, such change agency should foster innovation, increase economic diversity and create skilled jobs. From a social perspective, it should facilitate social cohesion while avoiding social exclusion, or increase participation in local decision-making, while reducing political and cognitive lock-in. Finally, in terms of the spatial (in the material and/or mental sense) attributes of the locality, change agency should support the revitalization and re-use of brownfields and declining urban environments according to new societal needs, create new spaces for informal networking and community building, or improve the image of the locality and the region.

Following this framework, we looked for such ‘agents of change’ in the selected towns. There were many potential candidates for our research because there are many positions, that could have a transformative character (e.g. positions in the local administration, government, firm’s management). In many cases, such positions are an important power prerequisite for the implementation of change agency, but they do not automatically guarantee that an actor will become an agent of change. For example, many political leaders and managers of firms are criticized for their passivity and for maintaining the current negative (sometimes locked-in) situation of the firm, region or locality, whereas others contribute to the construction of a new development path (and as such, in the context of this study, they are perceived as agents of change). It is therefore not a question of what position agents occupy, but whether they use it for change agency.

To identify agents of change, we combined the analysis of regional newspapers with a set of 21 semi-structured interviews (conducted from March to July 2020) with local and regional informants. Using these methods in combination with snowball sampling, we identified 43 agents of change which were interviewed between September 2020 and August 2021. describes the distribution of agents according to their dominant sphere of change agency. Although it was not intended, the interviewees were evenly distributed across the surveyed towns: 11 interviewees in Chomutov, 11 in Most, 10 in Teplice and 11 in Děčín. With the consent of the participants, the interviews were recorded (except for one interview when written notes were taken). The duration of the interviews varied between 30 and 150 min. The interview recordings were first transcribed, and then subjected to thematic analysis.

Table 1. Distribution of agents of change based on the categories of change agency.

Results

This section analyses what kinds of capital build the capacity to act of agents of change, and how these forms of capital have been mobilized as resources for the implementation of change agency. We highlight different ways of acquiring cultural, social, economic and symbolic capital. In this study, all forms of capital are understood primarily as assets that enable change agency. Therefore, in the text below, we propose a classification of five types of change agency combined with specific constellations of capitals. These types are based on the dominant drivers enabling the implementation of change agency. We also show that these types differ significantly in terms of their temporal nature and the role of locally specific factors influencing the character of change agency.

The identified types are as follows: (1.) Change agency driven by embodied cultural capital is mainly based on personal capabilities of the agent. (2.) Change agency driven by bonding social capital is strongly supported by family and friends of agents, while bridging social capital was a key resource for the type of change agency driven with support of public institutions (3.). Although the following type – of change agency accelerated by symbolic capital (4.) might seem similar to the previous type, it is different regarding its evolution – it usually started as the type 1 or 2 but was significantly accelerated after the agent had received a significant attention from the local public. In the case of change agency driven by economic capital (5.), the input of financial investment of the agent or his/her organization is more important than in the other types (see for a summary).

Table 2. Comparation of identified types of change agency.

Below, we also stress some specific features of change agency emerging from our research. First, we explain the importance of the agent's previous life path for the implementation of change agency. Second, we assess the radicality of change agency (does change agency initiate radical or rather incremental changes at the local scale?). Third, we consider the role of the locally specific factors (to what extent do different locational assets influence the implementation of change agency?).

Type 1: Change agency driven by embodied cultural capital

The first type includes initiatives that are driven by embodied cultural capital (e.g. personal energy and skills) of one key person (or a small group of people). The group of agents that fall into this type (14 agents of change) appears heterogeneous at first glance, being founders of local businesses or non-profit organizations. What links them, however, is the fact that they bring some form of innovation to the towns under study. While local enterprises create new regional industries (i.e. foundation of the first fashion studio in the region, software company) and introduce new production and management techniques (development of innovative municipal waste treatment technology combining local tradition of chemical industry with modern findings of waste management; production of decoys of army technique compiling locally declining textile industry with experiences of external military experts), leaders of cultural and interest groups promote new specific types of social activities that contribute to the development of new communities and place attachment. Here, such NGOs act as pioneers in tackling local problems, especially the social exclusion (they provide work consultancy and leisure activities for the socially excluded groups such as Roma minority, handicapped people and youth from orphanages).

Typical elements used as resources for change agency relate to embodied cultural capital, which includes diverse knowledge, experiences and skills accumulated during the agent's previous life. Agents in NGOs promoting social inclusion are more likely to be characterized by knowledge acquired through formal education (tertiary education). For agents in cultural NGOs and local enterprises, it is more likely to be a combination of experience gained through a previous hobby, a former professional position, or inspiration from places visited in other regions and abroad:

From the age of 16 or 17 I did things like painting exhibitions and DJing in a local tearoom. So, it was nothing new for me to set something up, to reach out to some people, to put it together. Also, when I went somewhere, whether it was Lisbon or Australia or whatever, I just kept my eyes open and looked at things that somehow interested me. Then I thought if it would be possible to apply in Most. (organiser of community events such as a festival or guided tours focused on the local architecture)

The above list implies, in part, that this type is relatively strongly dependent on the agent's previous life course, since it is the capacities accumulated in the past that ultimately allow the agent to perform this type of change agency. Nevertheless, from an individual perspective, this type cannot be considered as a routinized behaviour that corresponds to a previous career path or education. From the perspective of local development, it can be considered as radical changes because the actors are pioneers of a particular activity in a given place. The role of the place where change agency emerges is therefore crucial and can be considered as an enabling factor, as it is based on a niche identified by the agent that needs to be filled by a particular business or social activity. Thus, the characteristics of OIR in the case of individually driven change agencies imply an important enabling resource for their emergence.

Type 2: Change agency driven by bonding social capital

A characteristic feature of the second type of change agency in terms of enabling resources is collaboration with close actors among the agent's family members or friends. This type is based on five empirically observed stories of agents of change that build on a community-based way of working and usually aim to improve the place or to build communities and place attachment. This is an example of local NGOs organising community building events (such as thematic local walks; debates on famous local people and historical events; exhibitions of local artists) and creating meeting places for local people (i.e. in the revitalized building of historical barracks). Other change agencies are operated by local entrepreneurs, whose primary interests are economic, but community building (of new entrepreneurs through a co-working centre; actors in education through programmes for the inclusion of people at risk of social exclusion) and entrepreneurial innovation are also an intended consequence of their activities.

Although family and friends are also important in the other types of the change agency (especially individually driven), the initiatives included in this type would not have come about without the contribution of close relatives. In this case, the agent is the main ‘worker’ embodying change agency. However, financial and knowledge support based on bonding social capital are essential elements of change agency, without which the initiatives could not be started or carried out. In addition, the family and friends of the agents interviewed are usually an important source of motivation, inspiration and specific ideas about how a particular place or initiative should develop.

In contrast to other types, this one relies on a mosaic of cultural capitals of different agents, which are intertwined thanks to bonding social capital, and the resulting effect can thus be considered as collective change agency. Previous school, university or work experience of the agents in terms of acquired knowledge and skills had little influence on their agency compared to ties with their close relatives. On the other hand, these experiences have sometimes been recognized as resources of social bonds with collaboratives, as its noted by the representative of one of the NGOs:

During my university studies in Prague, a high school classmate and I met in a pub. We agreed that we saw our future in the social or environmental field and that we were not tempted to be a drop in the ocean somewhere in Prague. Instead, we were tempted to return to the region, where we considered ourselves as much more important. And then this debate hit several other people. They were mostly our friends or classmates from high school. And we decided to return (to the hometown) and do something for the neglected town.

Type 3: Change agency driven with support of public institutions

The third type of change agency is based on the use of a well-anchored agent within the structure of formal institutions. In some ways it is very similar to the change agency accelerated by symbolic capital, but the dominant driving force here is not the decision-making power of the individual per se, but rather the ability to navigate and exploit the legal framework of the relevant thematic and geographic area. Therefore, this category is more diverse in terms of the position from which agents perform change agency (local politician and entrepreneur, heads of a social service company, municipal chateau, state enterprise or municipal department). They usually engage in the revitalization of the public space (the chateau revitalization; open-cast lignite mine reclamation) and social inclusion (leadership of strategies avoiding social exclusion).

The capacity to act in this case is mainly built through the combination of two basic forms of capital – institutionalized cultural capital and bridging social capital. The two forms are inextricably linked, since institutionalized cultural capital is a formal prerequisite for directing change agency (it gives the agent a mandate to act), while bridging social capital enables its smooth functioning through well-organised and effective formal cooperation between the agent and other actors or organizations:

I think in the case of this town it is not about personal relationships and sympathies. It is the competence. That is, the competence of the consultant (a representative of the Agency for Social Inclusion of the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs), who has been working for us for the last few years. She forms an excellent tandem with the head of the municipal social department. And the political leadership also supports this cooperation. So, the cocktail has been well mixed here in recent years. (the representative of local department of development).

Type 4: Change agency accelerated by symbolic capital

The fourth type includes those change agencies whose development has been greatly accelerated by agents’ improved access to institutionalized power. It comprises only four actors who, in their efforts to intensify their change agency, have managed to gain access to local political leadership and, through this position, strengthen their own capacity to act. The objectives of their change agency are essentially the same (reconceptualization of the local policy or approach to avoid social exclusion) but specific instruments achieve this vary considerably. While two politicians focus on the provision of affordable housing for residents at risk of social exclusion, the third one promotes more restrictive measures to prevent social tensions and social pathologies (such as crime, disruption of public order).

The key asset for this type of change agency is the institutionalized cultural capital that comes from achieving a political position. However, this position arises from the symbolic capital, as the agents became known and respected through their previous activities, sometimes unrelated to the issue of social exclusion. For example, one politician became known as the manager of a popular ice hockey team:

I had a very good relationship with the whole fan community, with the people who went to the ice hockey matches. At that time, when we got involved in local politics, the club was at its peak. There used to be a full stadium, almost 5,000 people every week. And if nothing else, those 5,000 people knew that there was someone with my name.

Type 5: Change agency driven by economic capital

For this type of agency, the role of input investment of agents is its key element. The 11 agents of change belonging to this group include eight managers and founders of local firms and three managers of local branches of large TNCs. Of course, entrepreneurial activities of individual firms are an important financial resource for the development of change agency. In this case, change agency consists of the product and management innovation (i.e. establishing a corporate development department, motivational tools for employee engagement) and creation of skilled jobs for local people. In addition, these enterprises often have an impact on the material and social development of a place by regenerating brownfield sites and by sponsoring charitable and community activities of other actors.

This type is primarily driven by the economic capital controlled by the agent. Two subcategories of investments in change agency can be distinguished, although in some cases they overlap. On the one hand, some agents of this type carry out their change agency as an initiative that goes beyond their previous or parallel business activity and consider it as an investment of the money earned, considering the possibility of future profit and development of the place where they work:

I founded my maintenance and management firm in the 1990s with just myself and one employee. I sold the company in 2007 when I had 550 employees. So, I'd achieved the American dream, and I didn't know what to do with the money because there was a lot of it, which is nice. So, somebody told me: Just put it in a house. So, I started looking around, and because my property management company also managed, for example, shopping centres, I knew how they worked. Then it was very easy to find out which town had a shopping centre, and which didn't. (local entrepreneur who revitalized old brownfield)

The second category includes internal investment in the firm's activities to increase its competitiveness (various forms of product innovation, diversification of activities). It should be added that economic capital in this type is usually accompanied by strong embodied cultural capital (in the case of local entrepreneurs who direct the developmental impact of change agency) or institutionalized cultural capital (managers of firms use their position in the firm management for the same purpose). In addition, such change agencies are often accompanied by additional institutional support in the form of grants, often from EU and national funds to support research and development. The results of these projects are then implemented in the daily business practice of companies.

In this case too, change agency depends heavily on the previous work or study experience of the agents of change. Some have directly studied a subject relevant to their business or business management in the sector. Others draw on previous employment or other business activities they have undertaken in the past. This experience brought not only financial resources but also contacts and knowledge (bridging social and embodied cultural capital). The effects of this type change agency tend to be more long-term, as agents gradually introduce rather small innovations that affect the internal environment of the firm and only implicitly affect the development of the region (e.g. innovative firms are seen as ‘good’ employers offering skilled jobs). Occasionally, however, some larger projects emerge from this trend, which could be seen as a locally radical event (e.g. opening of a new spa facility, community café, microbrewery with a restaurant).

For this type, the locality where change agency takes place is an enabler. Some entrepreneurial activities are based on old industries that still survive to some extent thanks to innovations generated by agents and their firms. Other initiatives are based on knowledge of the local history and the value of the buildings in which the agent invests in line with identified niches in the local market.

Discussion and conclusions

Although this study methodically focuses on individual capacity to act, it is necessary to recognize that agents have always been situated in a complex network of social relations (Elder Citation1994) that influenced the direction and success of their change agency. Our results confirm that the capacity to act and to initiate and lead change agency in the structural conditions of OIR is the result of the combination of different forms of capital described by Bourdieu (Citation1986). In general, all agents of change have the inherent ability to mobilize these forms of capital (Brown and Westaway Citation2011). However, the importance of various capitals mobilized as resources of change agency (Píša Citation2023) differs significantly across five identified types of change agency. These types also vary in terms of development impacts and objectives, temporality and their place embeddedness.

As regards the first research question focused on the individual capacity to act, in our research, agency is understood as the activity of the individual – the agent of change. Thus, when implemented as change agency in the structural context of OIR, it can be understood as the exploitation of the agent-specific opportunity space (Grillitsch, Rekers, and Sotarauta Citation2019) and as the potential that arises from the different forms of capital held by locally acting agents. While the type of change agency driven by embodied cultural capital is primarily mobilized by the capacities and skills of the agent of change itself, it is clear that these capacities arise from the different contexts and impulses that the agent has absorbed over the course of its life. In terms of the constitutive elements that form embodied cultural capital, this type is the most diverse.

Indeed, it is not innate qualities (such as flexibility and creativity), as described by Maskell and Malmberg (Citation1999), that are important in building change agency, but rather the bonding social capital in the form of family background that fundamentally shapes the agent's worldview. However, formal education and bridging social capital is also an important element, as the agent draws inspiration and experience from extra-regional structures, which he/she then valorizes in change agency (Aziz Citation2015).

An agent's high degree of embeddedness in the local social network (as described by Van Deth Citation2008) at the level of family or close friends (Putnam Citation1995) and good local knowledge, which enables good orientation within local structures (Coleman Citation1988), play a role especially in the change agency driven by bonding social capital. Conversely, the ability to operate across structures outside agents’ close social networks (bridging social capital), considered a key element of change by Fitjar and Rodríguez-Pose (Citation2017) and Sotarauta and Mustikkamäki (Citation2014), is an important aspect of the change agency driven with support of public institutions and the change agency accelerated by symbolic capital.

For the former, the enabling element is the agent's formal education related to change agency, and both types depend heavily on the agent's leadership position in the organization (especially political leadership or management of a local government department). According to Bourdieu (Citation1986), these factors can be seen as elements of institutional social capital, but in the case of the change agency accelerated by symbolic capital, this was reinforced by the trust of the local electorate, which gave the agent the confidence and power to make decisions on local development issues (Griffin Citation2012).

Economic capital is necessary to some extent for all types of change agency, and its availability is largely dependent on other types of capital (Bourdieu Citation1986). However, what characterizes the change agency driven by economic capital is that the agents who possess it have already achieved a successful entrepreneurial or professional career (also dependent on social and cultural capital – Pileček, Chromý, and Jančák Citation2013), which allows them to invest their own or the firms’ money in further business or local development.

The second research question focused on the locally-specific and temporal setting shaping the individual change agency. In light of the results of this study and building on previous research (Kinossian Citation2019; Roberts, Collis, and Noon Citation1990; Gómez Citation1998; Benneworth and Hospers Citation2006), it can be argued that the specific locked-in structures of OIR that influence the actions of local agents cannot be understood in the context of resources for change agency as merely constraining factors that inhibit change (MacKinnon et al. Citation2019). In our study, we focus more on the specific notion of structures that have the character of enablers of change agency. This refers to social capital, which is sometimes extra-regional in nature (when the agent is inspired by actors from other places or benefits from the support of external actors), but is usually based on locally embedded ties (to family, friends and other actors in the region).

The cultural capital of agents themselves and others involved in change agency includes detailed local knowledge, including local history and traditional industries. These are particularly important for the change agency driven by bonding social capital and the change agency driven by economic capital. In addition, what we might normatively consider negative characteristics of OIR, such as the lack of services and innovative enterprises or the presence of brownfields, are turned by agents into an opportunity and thus a source of change agency (typical of the change agency driven by embodied cultural capital and by economic capital). For other agents, local social and material problems are even the main driving force in the form of motivation (the change agency driven with support of public institutions and the change agency accelerated by symbolic capital), which pushes the agent to carry out a specific initiative addressing local problems (more on the role of motivation for change agency in Píša and Hruška Citation2023). Thus, material and social specificities of a place always play an important role (according to Boschma Citation2017) of locally specific opportunity spaces (Grillitsch, Rekers, and Sotarauta Citation2019), defining the nature of development processes embodied in specific forms of change agency (Pike, Rodríguez-Pose, and Tomaney Citation2007).

We approached the temporality of change agency from the perspective of individual agents and from the perspective of the dynamics of local development. First, the concept of path dependency used to describe the trajectory of regional development (Martin and Sunley Citation2006) appears to be applicable at the individual level as well, since all types of change agency are significantly dependent on the previous life course (as suggested by Elder Citation1994) of the agents under study. This is manifested in the case of building embodied cultural capital through education and previous work experience of agents of change (change agency driven by economic capital and change agency driven with support of public institutions), long-term inspiration by other actors (change agency driven by bonding social capital and change agency accelerated by symbolic capital), or a mosaic of experiences from previous life phases (change agency driven by embodied cultural capital). Especially here it became obvious that the capacity to act could not only be gathered locally – very often the agent gained relevant sources through his/her stay outside the region. The specific constellation of these resources can be seen as an agent-specific opportunity space or capacity to act (Grillitsch and Sotarauta Citation2020), whose mobilization also depends on motivations (Píša and Hruška Citation2023), the ability to recognize a need or opportunity, and the willingness to promote change (Brown and Westaway Citation2011).

Second, the definitions of Grillitsch, Rekers, and Sotarauta (Citation2019) and Coe and Jordhus-Lier (Citation2011) imply that change agency always has a transformative character, which we followed when selecting the interviewees. Moreover, change agencies under investigation can be divided into two basic groups in terms of the speed of change. Change agency driven by bonding social capital and change agency driven with support from public institutions are more characteristic of long-term work of agents with an incremental character of change. The long-term nature of this process is partly caused by the limited financial resources of the agents, but above all by the need and necessity of coordination with other actors. This requires a lot of time, despite the existence of high-quality bridging or bonding social capital. On the other hand, there is the change agency driven by embodied cultural capital, which brings about radical change in the form of the introduction of new local services, cultural initiatives and economic diversification. Agents of the other types combine both forms, however, all recognized types of change agency cannot be understood as an immediate mobilization of capital in response to external crises, as suggested by Friedman (Citation2009), but rather as long-term activities that contribute to weakening the path dependency and locked-in position of the locality, as described by MacKinnon et al. (Citation2019) and Hassink (Citation2007).

Despite the possible limitations of our research (specific structural conditions of OIR in the post-socialist environment, complex and to some extent still subjective selection of interview partners, conducting interviews in the time of the COVID pandemic) our research highlights the diversity of change agency in the structural conditions of OIR in terms of their bearers and the resources they use for their implementation. Hereby, we aimed to shift the existing debate on change agency in a different direction than the dominant economic one, in order to take a more comprehensive view of development of OIR. In this respect, precisely because of the complexity of the actors, there is plenty of room for further research (also outside OIR), which would lead to the development of further typologies or refinement of the typology we have proposed. Further, attention should be paid to the ways how to systematically upgrade change agency of individuals into a collective agency and subsequently to a new development path of regions. Such upgrading will require a complete set of steps performed in collaboration with public bodies, educational institutions, firms and NGOs.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aziz, A. 2015. “The Operational Value of Human Capital Theory and Cultural Capital Theory in Social Stratification.” Citizenship, Social and Economics Education 14 (3): 230–241. doi:10.1177/2047173416629510.

- Bækkelund, N. 2021. “Change Agency and Reproductive Agency in the Course of Industrial Path Evolution.” Regional Studies 55 (4): 757–768. doi:10.1080/00343404.2021.1893291.

- Benneworth, P., and G. Hospers. 2006. “The New Economic Geography of Old Industrial Regions: Universities as Global — Local Pipelines.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 25 (6): 779–802. doi:10.1068/c0620.

- Blažek, J., and V. Květoň. 2022. “Towards an Integrated Framework of Agency in Regional Development: The Case of old Industrial Regions.” Regional Studies 57 (4): 1–16.

- Boschma, R. 1997. “New Industries and Windows of Locational Opportunity. A Long-Term Analysis of Belgium.” Erdkunde 51 (1): 12–22. doi:10.3112/erdkunde.1997.01.02.

- Boschma, R. 2017. “Relatedness as Driver of Regional Diversification: A Research Agenda.” Regional Studies 51 (3): 351–364. doi:10.1080/00343404.2016.1254767.

- Boschma, R., and R. Martin. 2007. “Editorial: Constructing an Evolutionary Economic Geography.” Journal of Economic Geography 7: 537–548. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbm021.

- Bourdieu, P. 1986. “The Forms of Capital.” In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, edited by J. Richardson, 46–58. New York, NY: Greenwood Press.

- Bourdieu, P. 2001. Masculine Domination. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Brown, K., and E. Westaway. 2011. “Agency, Capacity, and Resilience to Environmental Change: Lessons From Human Development, Well-Being, and Disasters.” Annual Review of Environment and Resources 36: 321–342.

- Cambridge dictionary. 2020. “Human Capital: Meaning in the Cambridge English Dictionary.” https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/human-capital.

- Chazel, F., and R. Boudon. 1992. “Traité de Sociologie. Paris, PUF, 195–226.” In Sociologie modernity: itinerář 20. století, edited by D. Martuccelli, 195–226. Brno: Centrum pro studium demokracie a kultury.

- Coe, N., and C. Jordhus-Lier. 2011. “Constrained Agency? Re-Evaluating the Geographies of Labour.” Progress in Human Geography 35 (2): 211–233. doi:10.1177/0309132510366746.

- Coleman, J. 1988. “Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital.” American Journal of Sociology 94: S95–S120. doi:10.1086/228943.

- Elder, G. 1994. “Time, Human Agency, and Social Change: Perspectives on the Life Course.” Social Psychology Quarterly 57 (1): 4–15.

- Emirbayer, M., and A. Mische. 1998. “What is Agency?” American Journal of Sociology 103 (4): 962–1023. doi:10.1086/231294.

- Fitjar, R., and A. Rodríguez-Pose. 2017. “Nothing is in the air.” Growth and Change 48 (1): 22–39. doi:10.1111/grow.12161.

- Friedman, M. 2009. Capitalism and Freedom. Chicago: University of Chicago press.

- Garud, R., and P. Karnøe. 2001. “Path Creation as a Process of Mindful Deviation.” In Path Dependence and Creation, edited by R. Garud and P. Karnøe, 1–38. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence, Earlbaum Associates.

- Giddens, A. 1984. The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Gómez, M. 1998. “Reflective Images: The Case of Urban Regeneration in Glasgow and Bilbao.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 22 (1): 106–121. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.00126.

- Grabher, G. 1993. “The Weakness of Strong Ties; the Lock-in of Regional Development in Ruhr Area.” In The Embedded Firm; on the Socioeconomics of Industrial Networks, edited by G. Grabher, 255–277. London: Routledge.

- Green, D. 2016. How Change Happens. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gregory, D., R. Johnston, G. Pratt, M. Watts, and S. Whatmore, eds. 2011. The Dictionary of Human Geography. Vancouver: John Wiley & Sons.

- Griffin, L. 2012. “Where is Power in Governance? Why Geography Matters in the Theory of Governance.” Political Studies Review 10 (2): 208–220. doi:10.1111/j.1478-9302.2012.00260.x.

- Grillitsch, M., B. Asheim, A. Isaksen, and H. Nielsen. 2022a. “Advancing the Treatment of Human Agency in the Analysis of Regional Economic Development: Illustrated with Three Norwegian Cases.” Growth and Change 53: 248–275. doi:10.1111/grow.12583.

- Grillitsch, M., J. Rekers, and M. Sotarauta. 2019. Trinity of Change Agency: Connecting Agency and Structure in Studies of Regional Development (No. 2019/12). Lund University, CIRCLE-Center for Innovation, Research and Competences in the Learning Economy.

- Grillitsch, M., and M. Sotarauta. 2020. “Trinity of Change Agency, Regional Development Paths and Opportunity Spaces.” Progress in Human Geography 44 (4): 704–723. doi:10.1177/0309132519853870.

- Grillitsch, M., M. Sotarauta, B. Asheim, R. Fitjar, S. Haus-Reve, J. Kolehmainen, L. Stihl, et al. 2022b. “Agency and Economic Change in Regions: Identifying Routes to New Path Development Using Qualitative Comparative Analysis.” Regional Studies 57 (1): 1–16.

- Hassink, R. 2007. “The Strength of Weak Lock-ins: The Renewal of the Westmünsterland Textile Industry.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 39 (5): 1147–1165. doi:10.1068/a3848.

- Kinossian, N. 2019. “Agents of Change in Peripheral Regions.” Baltic Worlds 12 (2): 61–66.

- Koutský, J. 2011. “Old Industrial Regions – Development Tendencies and Opportunities.” Doctoral dissertation, Masarykova univerzita, Přírodovědecká fakulta, Brno.

- MacKinnon, D., S. Dawley, A. Pike, and A. Cumbers. 2019. “Rethinking Path Creation: A Geographical Political Economy Approach.” Economic Geography 95 (2): 113–135. doi:10.1080/00130095.2018.1498294.

- Martin, R., and P. Sunley. 2006. “Path Dependence and Regional Economic Evolution.” Journal of Economic Geography 6 (4): 395–437. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbl012.

- Maskell, P., and A. Malmberg. 1999. “Localised Learning and Industrial Competitiveness.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 23 (2): 167–185. doi:10.1093/cje/23.2.167.

- Morgan, K. 2004. “Sustainable Regions: Governance, Innovation and Scale.” European Planning Studies 12 (6): 871–889. doi:10.1080/0965431042000251909.

- Morgan, K. 2013. “Path Dependence and the State: The Politics of Novelty in old Industrial Regions.” In Re-Framing Regional Development: Evolution, Innovation and Transition, edited by P. Cooke, 318–340. London: Routledge.

- Pike, A., A. Rodríguez-Pose, and J. Tomaney. 2007. “What Kind of Local and Regional Development and for Whom?” Regional Studies 41 (9): 1253–1269. doi:10.1080/00343400701543355.

- Pileček, J., P. Chromý, and V. Jančák. 2013. “Social Capital and Local Socio-Economic Development: The Case of Czech Peripheries.” Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie 104 (5): 604–620. doi:10.1111/tesg.12053.

- Píša, J. 2023. “How Individuals Become Agents of Change in old Industrial Regions.” Regional Studies, Regional Science 10 (1): 592–602. doi:10.1080/21681376.2023.2219723.

- Píša, J., and V. Hruška. 2023. “It was my Duty to Change This Place’: Motivations of Agents of Change in Czech old Industrial Towns.” Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, doi:10.1080/04353684.2023.2208580.

- Putnam, R. 1995. “Bowling Alone: America’s Declining Social Capital.” Journal of Democracy 6 (1): 65–78. doi:10.1353/jod.1995.0002.

- Rekers, J., and L. Stihl. 2021. “One Crisis, One Region, Two Municipalities: The Geography of Institutions and Change Agency in Regional Development Paths.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 124: 89–98. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.05.012.

- Roberts, P., C. Collis, and D. Noon. 1990. “Local Economic Development in England and Wales: Successful Adaptation of old Industrial Areas in Sedgefield, Nottingham and Swansea.” In Global Challenge and Local Response: Initiatives for Economic Regeneration in Contemporary Europe, edited by W. B. Stöhr, 135–162. London: Mansell Publishing.

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. 2013. “Do Institutions Matter for Regional Development?” Regional Studies 47 (7): 1034–1047. doi:10.1080/00343404.2012.748978.

- Sotarauta, M., and N. Mustikkamäki. 2014. “Institutional Entrepreneurship, Power, and Knowledge in Innovation Systems: Institutionalization of Regenerative Medicine in Tampere, Finland.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 33 (2): 342–357. doi:10.1068/c12297r.

- Stachová, J. 2008. “Občanská společnost v regionech České republiky.” Praha: Sociologický ústav AV ČR.

- Teachman, J., K. Paasch, and K. Carver. 1997. “Social Capital and the Generation of Human Capital.” Social Forces 75 (4): 1343–1359. doi:10.2307/2580674.

- Van Deth, J. 2008. “Measuring Social Capital.” In The Handbook of Social Capital, edited by D. Castiglione, J. W. Van Deth, and G. Wolleb, 150–176. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Walker, B., C. Holling, S. Carpenter, and A. Kinzig. 2004. “Resilience, Adaptability and Transformability in Social-Ecological Systems.” Ecology and Society 9: 5. doi:10.5751/ES-00650-090205.