ABSTRACT

This paper builds on an intensive and unique survey of all Czech municipalities (n = 6,258) regarding the geoparticipatory spatial tools used in the decision-making processes of local administrations and the Index of Geoparticipation derived from the dataset. Furthermore, we have collected and analysed data regarding 238 participatory budgeting events in the Czech Republic from the years 2012–2020. This paper is divided into two sections. We investigate the relationships among the municipalities’ membership in the Healthy Cities of the Czech Republic network (HCCZ), as well as the municipalities’ levels of indebtedness and their performances in the Index of Geoparticipation and their usage of participatory budgeting. Our primary theory states that membership in HCCZ and higher values in the Index of Geoparticipation will support the use of participatory budgeting, while indebtedness will discourage municipalities from implementing participatory budgeting. We deepen the knowledge of participatory budgeting in the Czech Republic, while focusing on the qualitative analysis of projects that have been approved and implemented through the tool of participatory budgeting at the municipal level. Additionally, we examine what type of projects the funds are allocated to and how the characteristics of these projects change over time.

1. Introduction

In recent years many European countries (including the Czech Republic) have opened their institutions to democratic innovations. These innovations are especially important on a municipal level as this is the closest governmental unit to its citizens as is required by the principle of subsidiarity. Local government represents a major instrument of decentralization in modern Europe, and it is a tool for improvement in the quality and efficiency of governance (Madej Citation2019). It is a modern global trend to involve citizens in financial decision-making in order to influence the division of the municipal budget, or at least part of it (e.g. Boukhris et al. Citation2016; Carrol et al. Citation2016 or Milosavljević et al. Citation2020).

In 1989 the Czech Republic (at that time Czechoslovakia) and its citizens embarked on the path of democracy. In the same year the idea of the participatory budget was introduced in the city of Porto Alegre in Brazil (Aragonés and Sánchez-Pagés Citation2009; de Olivero Dutra Citation2014; Milosavljević et al. Citation2020). The process of participatory budgeting is usually designed to involve people who are excluded from the traditional approaches to citizens’ engagement, such as low-income residents, young people and marginalized/disadvantaged groups (Participatory Budgeting Project Citation2021). This was the case in Porto Alegre, where it was mainly low-income and marginalized groups of citizens who were not satisfied with the allocation of public money, and they claimed that the majority of the municipal budget was spent on the wealthier parts of the municipality, while the most vulnerable areas were neglected. In 1988 the Brazilian Workers’ Party won the municipal elections in Porto Alegre with a programme of more equitable budget distribution. After one year in power the party introduced the first concept of participatory budgeting in the world (Fung Citation2006). In the early years the new concept of public money allocation in Brazil was met with low, but steadily rising interest from the citizens (Institute H21 Citation2017). By 1999 participatory budgeting celebrated a real success in terms of involving people typically left out of the political process. The money allocated to participatory budgeting in Porto Alegre was 60 million EUR, or 21% of the total budget in 1999Footnote1 (Local Government Association Citation2021). The process of incorporating participatory budgeting into public policy has been much slower in the Czech Republic than in Brazil, although many democratic innovations (such as a public referendum, round tables, public hearings etc.) have been introduced during the 33 years of democracy’s long journey.

Our study extends upon the Brazilian paradigm, employing a comprehensive approach that involves the aggregation and examination of Czech data pertaining to participatory budgeting. Subsequently, we derive empirical insights concerning its efficacy within the context of young post-Soviet democracy. Our research is divided into two domains – the first is to investigate the relationship between participatory budgeting implementation and networking/fiscal/participation activities of studied municipalities. The second domain is the typology of investments/projects funded by the money allocated through participatory budgeting. These two domains can be also read as What are the elements affecting the participatory budgeting implementations? and How the money is spent in participatory budgets?

According to our database, the first participatory budgeting eventsFootnote2 in the Czech Republic were introduced in 2012 in four municipalities (Nelahozeves, Pržno, Příbor and Třanovice). These municipalities also managed to sustain participatory budgeting in the years 2013 and 2014. They were truly the first pioneers of this idea in the Czech Republic, as there was no governmental or other institutional support, no previous experience to learn from, and a lack of citizen engagement in general. There was only one participatory budgeting event in 2015 (in one of the capital’s districts – Prague 7). Since 2016 there has been a linear increase in the use of participatory budgeting in the Czech Republic as more and more municipalities use this tool and see its potential benefits. By the year 2020, at least 117 municipalities have, at least once, embraced the idea of participatory budgeting, with at least 238 participatory budgeting events.

This paper is linked to an introductory chapter about participatory budgeting in the Czech Republic contained in a book about geoparticipation in the Czech Republic (see Pánek Citation2022). In that chapter we provided a general overview of the essential characteristics of participatory budgeting in the Czech Republic. We also provided quantitative statistics and information derived from the database of all participatory budgeting in the Czech Republic. Furthermore, we searched for the relationship between the municipal population and the money allocated to the participatory budgeting events. We also explored the relationship between political parties (including political movements) and the money allocated to participatory budgeting events.

This paper is divided into seven sections. The introduction gives an overall context to the topic and describes the general situation in the Czech Republic with reference to the origins of the participatory budgeting concept. The Literature Review (Section 2) provides a general definition of participatory budgeting, its theoretical background and the broader context of this tool. Objectives and Methodology (Section 3) provides an in-depth description of the methodology used and the goals of this paper. Findings of the relationships among networking, indebtedness, e-participation and participatory budgeting in the Czech Republic (Section 4) shows the results of the statistical correlation between participatory budgeting, networking, indebtedness and e-participation. The typology of the projects and basic descriptive statistics are portrayed in Section 5. We apply the categorization of projects as used by HCCZ. In the Discussion the results are discussed and compared to the pre-existing literature. The final section summarizes the article and includes the final notes of the authors.

2. Literature review

Participatory budgeting is a process of democratic deliberation and decision-making. It is a broad concept that encourages local communities to express their needs, as well as to take responsibility for their environment, and a tool of increasing transparency and civil control in governing (Madej Citation2019). Participatory budgeting is usually a tool within a broader participatory governance package (Avritzer Citation2017). Carrol et al. (Citation2016) summarize the reasons why participatory budgeting is implemented, and they define six aspects that attract the most interest: democracy, transparency, education, efficiency, social justice and community. These aspects may differ in various geographical locations. There are other very important dimensions to public participation: (1) how to participate, (2) who participates, and (3) how participation is linked to public policy (Fung Citation2006). Participatory budgeting has often been celebrated as the triumph of participatory democracy, as the ‘democratic innovation’ stemming from the South, enabling the empowerment of citizens through engaging them in fiscal decision-making (Krenjova and Raudla Citation2018). According to Ewens and Voet van der (Citation2019), participatory budgeting has been one of the most important public administration innovations of the last three decades. Although the idea of participatory budgeting has many advantages, it needs to be critically examined. According to Milosavljević et al. (Citation2020) budgetary resources (compared to the size of municipal budgets) are very small in reality. This was confirmed in the Czech Republic where the money allocation per capita varied greatly (from 0.20 to 37.32 EUR) between the years 2012–2020 (see Pánek Citation2022). Milosavljević et al. (Citation2020) specify a number of prerequisites necessary for the successful implementation of participatory budgeting programmes. The most important of these is the double-sided willingness of both the municipalities and their citizens. Municipalities should be willing to implement, maintain and develop such a tool, and they should work to attract citizens to participate. Citizens should be willing to propose ideas (projects) and to participate during the long-term process which includes a public presentation of the projects, a voting period, the announcement of results and the implementation of the chosen projects.

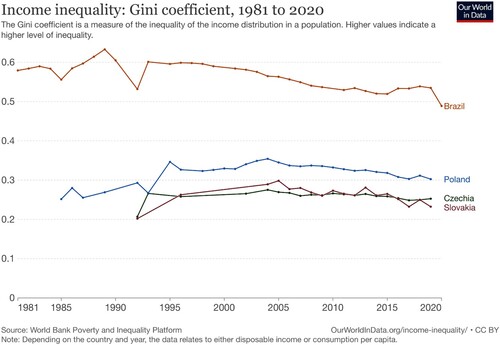

We can argue about the impetus that leads Czech municipalities to adopt participatory budgeting. The incentive of tackling social disparities, as in the case of Porto Alegre, is questionable because the Czech Republic, similarly to other central European post-Soviet democracies, is considered a socially equal society compared to Brazil (see ).Footnote3 There are many different frameworks of participatory budgeting that are adjusted to local conditions and specifications and that have evolved during the course of time as a result of legal, social, political and historical traditions (Brun-Martos and Lapsley Citation2017). Nevertheless, two basic types of participatory budgeting are internationally recognized. The first is the ‘Porto Allegre type’, which is named after the municipality already mentioned above. The ‘Porto Allegre type’ is focused on social justice issues with the aim of reducing the extreme disparities in income and quality of life that exist between the rich and the poor. The second form of participatory budgeting was implemented in Europe with some modifications, and therefore the term ‘Porto Allegre adapted in Europe’ is used (Kukučková and Bakoš Citation2019). This is linked to the typology of participatory budgeting created by (Sintomer, Herzberg, and Röcke Citation2008), where the authors use the Spanish town of Cordoba (320,000 residents) as an ideal example of the second type of participatory budgeting. This typology was also used by other researchers dealing with participatory budgeting in the Central European region (see Dzinic, Svidronova, and Markowska-Bzducha Citation2016). Unlike the Porto Alegre type of participatory budgeting, discussions around the European (adapted) type primarily deal with specific investments and projects, as opposed to a general political discussion about the quality of housing, education and traffic issues. The adapted model is specific, because in the participatory budgeting process there is significant impetus to actualize proposals that arise from the process, and local governments are obliged to honour their commitment to accepting them. While municipal councils remain formally accountable for the ultimate decisions regarding their budgets, citizens possess a de facto (co-)decision-making capacity.

Figure 1. Gini coefficient comparing Brazil with Czech Republic, Poland and Slovakia. Source: World Bank (Citation2021).

In the Czech context we can use the example of a participatory budgeting framework from Ostrava-Poruba, a city district within the city of Ostrava,Footnote4 which is the third largest city in the Czech Republic. As regards participation, Ostrava-Poruba can be considered as an example of good practice, especially in the field of participatory budgeting. Citizens can decide about specific investment projects. There are five phases in this participatory budgeting framework. A participatory budgeting event starts with proposals by citizens for specific projects. Usually there is a great variety of projects. Every citizen of Ostrava-Poruba over 15 years of age can propose their own idea. In the consultation phase, an assessment of the feasibility of individual proposals is carried out (e.g. land ownership), including an evaluation of the formal conditions of the participatory budgeting (most often this relates to meeting the maximum amount of money allocated per project). Projects that are found feasible are then promoted as promotion is the next phase. There is special webpageFootnote5 dedicated to participatory budgeting where all information is provided and promotion is being carried out. Voting is the crucial part and it is done both online and offline in order to ensure the participation of different segments of the population. Offline voting usually takes place during a so-called public forum.Footnote6 Online voting usually lasts one month. Results are published on the website and the municipality processes the project documentation and sets a deadline for when the successful proposal will be implemented.

Our paper builds upon knowledge from Estonia, Poland, Serbia and Slovakia, where attempts at participatory budgeting implementation have already been examined by academics. In the distinguished publication ‘Hope for Democracy’ by Dias (Citation2018) there is a chapter dedicated to Poland concerning lessons learned. Yet little is known about the context of participatory budgeting in the Czech Republic. In the online database ‘World Atlas of Participatory Budgeting’ there are only eight participatory budgeting events mentioned in the Czech Republic, while our research confirms over 200 events. See for example Sześciło (Citation2015), Makowski (Citation2019), Madej (Citation2019), Kempa and Kozlowski (Citation2020) and Lésniewska-Napierała and Napierała (Citation2020) for lessons learned in Poland. To fully examine Serbia’s experiences with participatory budgeting, see Milosavljević et al. (Citation2020). Valuable lessons and expert opinions from Slovakia can be found in Hrabinová et al. (Citation2020) and Bardovič and Gašparík (Citation2021). To perceive the experiences with participatory budgeting from Estonia, see Krenjova and Raudla (Citation2018).

We conducted the first national study of participatory budgeting in the Czech Republic. The examples from Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) are selected specifically because of those countries’ common post-soviet history and being relatively young democracies. During the communist era zero participation was expected from citizens in the decision-making process. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the situation slowly began to change and participation was expected to some extent. Participatory budgeting is a tool that was introduced to tackle social disparities in countries with high levels of inequality. On the other hand, post-communist countries in Central Europe are on the opposite side of the inequality ladder, and their societies tend to be quite egalitarian (see ). The rationale for implementing such a tool differs considerably between Latin America and Central Europe. For a more detailed review of the use of participatory budgeting outside our study area (CEE) we recommend the paper by Bartocci et al. (Citation2022).

3. Objectives and methodology

There are two main domains for this paper with a mixed method approach. The first is to investigate the relationship among the municipalities that are members of the Healthy Cities of the Czech Republic network (HCCZ), to research the municipalities’ indebtedness, their performances in the Index of Geoparticipation, and their use of participatory budgeting. Our primary theory states that membership in HCCZ and higher values of the Index of Geoparticipation will support the use of participatory budgeting, while indebtedness will discourage municipalities in the implementation of participatory budgeting. These three drivers were selected for the following reasons. Being a member of HCCZ means promoting public participation in public governance. So there is a presumption that members of HCCZ would be more likely to use the tool of participatory budgeting than non-members. Participatory budgeting presents another form of distributing public money, and in this case the authorities do not possess full control over the spending. When a municipality is in debt and the budget is tight we believe that the municipality is less willing to allocate money via participatory budgeting. The Index of Geoparticipation represents a new concept in measuring participation, transparency and communication of municipalities in the Czech Republic. In the following part a more detailed description of the Index of Geoparticipation is given, together with information about the National Network of Healthy Cities of the Czech Republic and the data sources regarding municipal indebtedness.

We have created our own dataset (n = 6,258) based on an intensive survey of all municipal websites in the Czech Republic regarding data availability, use of GIS and participatory methods etc. (Pánek Citation2022). As part of the survey we have also collected data about participatory budgeting events in the Czech Republic between the years 2012–2020 (n = 238). The Index of Geoparticipation is constructed using data that are only valid for the year 2020. That is why we have not been able to analyse all participatory budgeting events (n = 238) and we have scrutinized only 68 municipalities that implemented participatory budgeting in 2020. See for an overview of the surveyed municipalities.

Table 1. How many municipalities have been analysed?

To define what is a municipality and/or town/city in the Czech Republic, we have used the definitions of the Czech Statistical Office (Citation2021) and visualized the various values for the size of the municipalities and their overall number in and . Due to several historical reasons (some cities/towns were given their status by kings several centuries ago and this was often not related to their level of importance), there is a high variability in size and population among different categories of Czech municipalities (incl. towns and cities – see tables below). Nevertheless, regardless of the size/type of municipality in the Czech Republic, they all have a form of independent council and their own budget. They all also have the right to set the level of property tax that goes directly to the municipality budget.

Table 2. Number of municipalities as categorized by population (as of January 2021).

Table 3. Population of municipalities by status (as of January 2021).

We have already mentioned the large percentage (21%, or 60 million EUR) of the municipal budgets allocated to participatory budgeting in Porto Alegre in 1999. Such amounts are not applicable in the Czech Republic. In comparison with Porto Alegre the amounts are very modest. Speaking in absolute numbers, the highest amount was allocated by the municipality of Brno (381,346 inhabitants) in 2019 (see ). They provided 1,363,353 EUR, which was 0.21% of the municipal budget. Brno decided to implement the budgeting on the level of the whole municipality, rather than on the level of individual districts, unlike Prague for instance, where each district is responsible for the implementation of its own participatory budget. In contrast, the lowest amount was allocated by the municipality Halenkov (2,428 inhabitants) in 2019. They supported the first year of participatory budgeting with 1,948 EUR, or 0.11% of the municipal budget.

Table 4. The 5 municipalities that allocated the most (left column) and the 5 that allocated the least (right column) amounts of money (in absolute numbers) in the Czech Republic.

In relative numbers (see ), the highest percentage of the municipal budget was used by the municipality Bílá Voda (inhabited by 314 citizens) in 2017. They allocated 7,596 EUR, or 8.19% of the total budget. The lowest percentage of the municipal budget was allocated by two municipalities (Litoměřice – 24,168 inhabitants and Nový Jičín – 23,496 inhabitants). Both municipalities dedicated 0.02% of their municipal budgets, which was 8,850 EUR in the case of Nový Jičín in 2018 and 7,398 EUR in the case of Litoměřice in 2016. The low money allocation for these municipalities may be surprising, because Litoměřice has already implemented participatory budgeting five times and Nový Jičín three times. In the Czech context they can be considered as experienced implementers of participatory budgeting, as well as very active members of the Healthy Cities Network.

Table 5. The 5 municipalities that allocated the most (left column) and the 5 that allocated the least (right column) amounts of money (as a percentage of their total municipal budget) in the Czech Republic between the years 2012–2020.

We can clearly see from that Brno is the municipality that continually provides the highest amount of money in absolute numbers for participatory budgeting. We mentioned earlier that Brno uses participatory budgeting on the level of the whole municipality, rather than on the level of city districts. Thus, the money allocation tends to be higher because it aims for the inclusion of more citizens and possibly also for a higher number of projects. It is also important to say that Brno is the second largest city in the Czech Republic, hence their budget is much larger than those of other municipalities.

In the first part of our research we used quantitative analysis as all calculations have been made in Stata 13. Correlation was used to determine the relationships among the municipalities that are members of the Healthy Cities of the Czech Republic network, and to find the municipalities’ indebtedness, their performance in the Index of Geoparticipation and in participatory budgeting.

3.1. Index of Geoparticipation

The Index of Geoparticipation (Burian et al. Citation2023; Pánek et al. Citation2021) is an indicator-based index divided into three dimensions (communication, participation, transparency) and it helps to evaluate the state of geoparticipation in Czech municipalities. It describes the current state of geoparticipation at the municipality level in the Czech Republic (n = 6,258) with the aim of filling a gap in the research by finding which components of geoparticipation at the municipality level are being used, and how their use is affected by the size of municipalities and their membership of Local Agenda 21 networks. Each dimension contains four indicators (see ). All indicators have the same weight. The Index of Geoparticipation has values 0 to 12, with 0 being the lowest participation rate and 12 the highest participation rate. We expect that municipalities with higher scores in the Index of Geoparticipation will be more likely to use participatory budgeting than municipalities with lower value of Index of Geoparticipation.

Table 6. Index of geoparticipation indicators.

3.2. Networking

The National Network of Healthy Cities of the Czech Republic (HCCZ) is a professional association of 135 cities, municipalities and regions. The network has a variety of members, consisting of 6 regions, 5 regional capitals, 66 cities, 29 other municipalities, 12 Prague districts, 12 microregions and 5 local action groups. In total, HCCZ represents over 6 million inhabitants (approx. 58% of Czech population). It is one of the leading organizations in the area of participation in the Czech Republic, which is the reason we have chosen this organization for our article. HCCZ has been active in the Czech Republic for almost 30 years. The activities of HCCZ are internationally certified by UN-WHO under Agenda 21. It provides hundreds of examples of good practice, mutual inspiration and sharing of successful solutions among its members. It promotes town halls on Healthy Cities TV and at a number of national conferences and seminars (HCCZ Citation2022). It focuses on engaging (participation) the local community, schools, NGOs and businesses. HCCZ can assess the quality of life and health of residents based on indicators, and it helps its members with strategies and management through projects and indicators. The network is sometimes criticized for its high level of bureaucracy, and the extent of the advantages that membership brings has been brought into question. Nevertheless, we have compared our municipal dataset of participatory budgeting with the official HCCZ membership list on their website. HCCZ promotes participation, and in the context of participatory budgeting we expect that membership in this network would result in a higher use of participatory budgeting than it would with non-members of HCCZ.

3.3. Indebtedness

The Ministry of Finance of the Czech Republic provides an official and in-depth financial databaseFootnote7 of all municipalities, regions, state-subsidised organizations, local state-subsidised organizations, ministries, cohesion regions and of the state itself. This database is publicly accessible on the government website and it is updated on a regular basis (Ministry of Finance of the Czech Republic Citation2022). We used data from this database to analyse the level of indebtedness of each municipality, and as the basis for calculating the ratio of municipal debt to average. We expect municipalities that have more debts would have less incentive to share public money with their residents through participatory budgeting than municipalities that have little or no debts. For the purpose of our analysis an individual participatory budgeting event is expressed as money per capita allocated for participatory budgeting in a municipality. The data regarding the allocation of money has been collected during the research. In order to make a fair comparison we have collected data regarding the population of each municipality that participated in participatory budgeting in the year 2020. The source of this data is the Czech Statistical Office (Citation2021). We then divided the money allocated to participatory budgeting in each municipality in 2020 by the number of citizens living in a municipality in that year. As a result, we obtained each municipality's spending on participatory budgeting per capita for the year 2020.

The second domain of this paper is to determine what type of investments/projects receive the money allocated through participatory budgeting. This part goes beyond the numbers (quantitative analysis) exploring also the typology (qualitative analysis) of funded projects. As we can see from the previous tables, the overall allocation of money via participatory budgeting in the Czech Republic is negligible in comparison with, for example, Porto Alegre in 1999. The concept of traditional budgeting still plays a key role and there are no major investments carried out via participatory budgeting in the Czech Republic. That is why we collected data from the years 2012–2020. The data collection was made via municipal websites, but not all the municipalities that implemented participatory budgets had the data available on their websites. In contrast, a few of the municipalities had created special websites solely for the purpose of informing people about participatory budgeting events. Then we carried out a crosscheck to verify our preliminary database through comparisons with other sources of information on participatory budgeting (mainly websites), especially the webpage participativni-rozpocet.cz.Footnote8 After this comparison we had the final database. Between the years 2012 and 2020 a total of 238 participatory budgeting events occurred. Of those we have been able to find detailed information about projects in 174 cases. We have adopted the categorization of the projects used by HCCZ as stated on their website.

4. Findings of the relationships among networking, indebtedness, e-participation and participatory budgeting in the Czech Republic

Participatory budgeting is a tool tailored for citizens in order to bring them closer to the decision-making process. It also brings limited control over the municipal financial resources that are acquired by taxing the citizens. In this section we explore how the funds allocated to participatory budgeting, networking, municipal indebtedness and e-participation are all related. We expect that municipalities with higher scores in the Index of Geoparticipation will be more likely to use participatory budgeting than municipalities with lower values in the Index of Geoparticipation. We also presume that membership in the HCCZ network would result in greater use of participatory budgeting than it would with non-members. Additionally, we expect municipalities that have greater debts to have less incentive to share the public budget with their residents through participatory budgeting than municipalities with little or no debts. We used the statistical program Stata 13 to find a possible correlation and thus to verify our hypothesis.

First, we found a negative correlation (p = −0.0412) between participatory budgeting and municipal indebtedness. The correlation is so weak that we can state that there is no relationship between municipal indebtedness and the allocation of money for participatory budgeting (see for overview of results statistics). This result is surprising for us. We expected that the greater a municipality’s debt, the less money it would allocate to the participatory budget. The result does not show us the expected pattern. Even municipalities with large debts are willing to share public money via participatory budgeting. This is the case in several Czech municipalities (for example, Beroun, Český Krumlov and Lanškroun). Despite being in debt (the ratio of debt to average income ranged between 30% and 64% in 2020), the municipalities still allocate money to participatory budgeting. Participatory budgeting is an increasingly popular tool among municipalities.Footnote9 One possible explanation could be that this may create a better perception of the local municipality and thus help the present incumbents’ chances of re-election.

Table 7. Basic statistical description.

Second, we obtained a positive correlation (p = 0.2303) between participatory budgeting and membership in HCCZ. This means that members of HCCZ allocate more money to participatory budgeting than non-members. Nevertheless, the correlation is quite weak. This result was expected because HCCZ emphasizes the role of participatory democracy (participatory budgeting is one of the methods used in participatory democracy) among its members. HCCZ also helps its members to conceptualize and set in place public policies that encourage participatory methods. Factors that create suitable conditions for the implementation of participatory budgeting and its continued use include; support for setting up participatory methods, pressure from HCCZ for municipalities to introduce these methods, sharing good practices among the members of HCCZ, and the willingness of municipalities to implement participatory methods. Membership in HCCZ influences how much a municipality spends on participatory budgeting, although it is not the only criterion for the implementation of a participatory budget and its continued use. According to our database, of the 54 Czech municipalities that implemented one or more participatory budgeting events, 31 decided to keep the same amount of money for the participatory budget as in the previous year, 21 increased the amount, and in one case the municipality decreased the amount compared to the previous year. There is also one unusual case; the municipality of Šluknov. The municipality of Šluknov organized participatory budgeting events over three consecutive years (2018, 2019 and 2020). In 2019 the municipality increased the allocation of money compared to 2018, but in 2020 they decreased the financial contribution to participatory budgeting. Of the 54 Czech municipalities that implemented one or more participatory budgeting events, only 17 were members of HCCZ, while 37 municipalities were not members of the organization in 2020. Alternatively, of the 21 municipalities that increased the allocation of money to participatory budgeting in consecutive years, 12 were members of HCCZ, and 9 were not members.

The third correlation, that between participatory budgeting and the Index of Geoparticipation, is also quite weak (p = 0.1680). Municipalities with a higher value in the Index of Geoparticipation allocated more money to participatory budgeting. The Index of Geoparticipation consists of three dimensions (communication, participation and transparency). A municipality that scores well in participation may fall short in the criterion of transparency, and this lowers their overall index score. That is the reason we decided to correlate the money per capita allocated to participatory budgeting individually for each dimension of the Index of Geoparticipation. We obtained correlation (p = 0.1684) between participatory budgeting and the dimension of communication. This relationship is slightly stronger than the relationship between participatory budgeting and the dimension of participation. Despite the fact that the difference is low, the results surprised us as we had expected the strongest correlation to be between participatory budgeting and the dimension of participation. This correlation had the same value as the correlation between the whole Index of Geoparticipation and participatory budgeting (p = 0.1680). Municipalities with a higher value in the dimension of participation allocated more money to participatory budgeting. However, it is also a weak correlation. We found negative correlation (p = −0.0287) between participatory budgeting and the dimension of transparency. The correlation is so weak that we can state that there is no relationship between the dimension of transparency and the allocation of money to participatory budgeting (see for an overview of the resulting statistics). It is important to note that the correlation describes the size and direction of the association between two or more variables. Correlation does not imply causation. Based on the analysis, weak correlations were found between the observed variables. The results of the analysis at least give us an indication of the direction of the relationships among the selected variables. Nevertheless, we are unable to state what caused the correlations.

5. What types of projects are financed via participatory budgeting in the Czech Republic?

After the quantitative description of participatory budgeting we focused on the qualitative aspect of the projects financed through participatory budgeting. In this section we apply the categorization of projects as used by the Healthy Cities of the Czech Republic. HCCZ maintains a webpage called dobrapraxe.cz,Footnote10 which shows examples of successful projects that have arisen from communal politics. HCCZ differentiates 11 types of projects. Each category is further specified and there are lists of the specific projects. See for an overview of the project categorization. We found evidence of 238 individual participatory budgeting events between 2012 and 2020. Of this number, we found additional information (regarding the project typology) concerning 174 participatory budgeting events. A total of 839 projects were identified from the 174 participatory budgeting events between 2012 and 2020. We have been able to assign all 839 projects to one of the 11 categories. Each project is assigned to one category only. Unfortunately, we were only able to compare 731 projects with their total cost (see Footnote11). The cost was not indicated for 108 projects out of 839. See for the overall number of research samples.

Table 8. Categorization of projects.

Table 9. Overview of participatory budgeting events and projects with (non) identified total cost between years 2015–2020Table Footnotea.

As can be seen in , there was a growing trend in the number of participatory budgeting events between 2015 and 2020. There were 4 projects in 2015, 133 in 2018, and 309 in 2020. This trend is related to the increase in participatory budgeting events between 2015 and 2020. While there were 10 participatory budgeting events in 2016, there were 26 in 2018 and 92 in 2020. This tool is gaining more and more popularity among Czech municipalities. As yet we have no data for 2021 and 2022, so we can only make assumptions about the impact of Covid-19 on participatory budgeting in the Czech Republic in those years.

The overall cost of 731 projects between 2015 and 2020 was 15,483,503 EURFootnote12 as indicated in . The average cost of all projects was 18,455 EUR, while the median cost of all projects was 10,695 EUR. The citizens of Czech municipalities invested the most money in the category of culture and leisure; 39% (or 6,092,732 EUR) of the total amount distributed through participatory budgeting went to cultural and free-time activities. The average cost of a project in this area is slightly above the average cost of all projects (20,309 EUR). This category also has the highest number of projects (40%, or 300). The category of culture and leisure seems to be predominant. This is no surprise because the category incorporates activities that support the cultural life of local communities, and these activities do not need such large investments as the category of public health, for example, where building a physical infrastructure is usually required. The category of public health is second in absolute terms, with 3,369,786 EUR (or almost 22%) spent between 2015 and 2020. The number of projects is about one third lower than in the category of culture and leisure, while the average amount spent per project in this category was the highest of all categories – 34,038 EUR. This can be explained by the necessity of building a physical infrastructure for sporting activities. We expected this category to rank first because sports clubs with a large membership base usually have a strong mobilizing potential. Of the overall results, the small amount allocated to the category of social environment is surprising to us. We expect that this is because of the lower participation rate among the older generation. To confirm this hypothesis we would need to know the age structure of voters taking part in participatory budgeting, but unfortunately we do not have this data from the municipalities.

6. Discussion

According to Wampler et al. in Dias (Citation2018), while there is a large and growing body of literature about participatory budgeting, there are still several areas of research that are under-developed and under-theorised. One problem is the lack of reliable data, which leads to findings based on single-case studies or small-N comparisons. This paper seeks to fill this void with an extensive database of participatory budgeting in the Czech Republic, both quantitative and qualitative. This database is based on an intensive survey of all Czech municipalities (n = 6,258) regarding the levels of their participation, transparency and communication. As part of the survey we have also collected data about participatory budgeting events in the Czech Republic between 2012 and 2020 (n = 238). The data were subjected to quantitative and qualitative analysis. First, we used the statistical software Stata 13 to analyse the relationships among participatory budgeting (money allocated per capita for participatory budgeting), networking (membership in HCCZ), municipal indebtedness (municipal debt to average income ratio) and e-participation (performance in the Index of Geoparticipation). Correlations were found specifically for the year 2020, because the Index of Geoparticipation is only valid for this year. Despite this limitation we have analysed 68 Czech municipalities. We found a negative correlation (p = −0.0412) between participatory budgeting and municipal indebtedness. The correlation is so weak that we can state that there is no relationship between municipal indebtedness and money allocation for participatory budgeting. The result did not confirm our hypothesis. Even municipalities with high debts distribute public funding via participatory budgeting (for example Beroun, Český Krumlov and Lanškroun). We obtained a positive correlation (p = 0.2303) between participatory budgeting and membership in HCCZ. This means that members of HCCZ allocate more money to participatory budgeting than non-members. However, the correlation is quite weak. This result was expected since HCCZ emphasizes the role of participatory democracy (participatory budgeting is one of the methods used in participatory democracy) among its members, although some members of HCCZ are focused on the utilization of the tool rather than on the amount of money dedicated to the participatory budget. In other words, the incorporation of the citizens into the decision-making process is more important than the projects that are being implemented. This is the case in the city of Litoměřice. They have had seven participatory budgeting events since 2016, but the maximum amount of money allocated to successfully implemented projects is 200,000 CZK (8,227 EUR). This tells us that the process is more important than the projects’ outcomes. The leaders of municipality Litoměřice perceive participatory budgeting as one of the practical tools on how to approach citizens while it is considered cost-effective. They pursue participatory budgeting as a good practice that is also recommended by HCCZ. The common practice among Czech municipalities is to have a special website dedicated to promotion of participatory budgeting as mentioned in the case of Ostrava-Poruba. This statement is in compliance with Cabannes (Citation2004) who mentioned that 23 out of 25 cities studied have a website that is principally used for one way communication of budget information.

The third correlation, between participatory budgeting and the Index of Geoparticipation, is also quite weak (p = 0.1680). Municipalities with a higher value in the Index of Geoparticipation allocated more money to participatory budgeting. Due to the weakness of the correlation we decided to correlate each dimension of the Index individually. We obtained correlation (p = 0.1684) between participatory budgeting and the dimension of communication. This relationship is slightly stronger than the relationship between participatory budgeting and the dimension of participation. This correlation has the same value as the correlation between the whole Index of Geoparticipation and participatory budgeting (p = 0.1680). We found negative correlation (p = −0.0287) between participatory budgeting and the dimension of transparency. The correlation is so weak that we can state that there is no relationship between the dimension of transparency and the money allocated to participatory budgeting.

We also targeted the qualitative aspects of the projects financed via participatory budgeting. We have applied the categorization used by HCCZ, which distinguishes 11 categories. We found evidence of 238 individual participatory budgeting events between 2012 and 2020. From this number we found additional information (regarding the project typology) about 174 participatory budgeting events. A total of 839 projects were identified from the 174 participatory budgeting events between 2012 and 2020. The percentage of municipal budget allocated to participatory budgeting ranges from 0.02% to 8.19% according to our findings. The highest percentage occurs in the small village Bílá Voda (population under 300 citizens). This amount occurred only once and it was a clear exception. Most municipalities allocate less than 1% of their budget. This finding is similar to the results of Kempa and Kozlowski (Citation2020). They found that Polish city Sopot allocates 1% to participatory budgeting. We assigned all 839 projects to one of the 11 categories. Each project was only assigned to one category. Unfortunately, we have been able to compare just 731 projects with their total cost. The cost is not indicated for 108 projects out of 839. The overall cost of 731 projects between 2015 and 2020Footnote13 was 15,483,503 EUR, as indicated in . The average cost of all projects was 18,455 EUR, while the median cost of all projects was 10,695 EUR. The citizens of Czech municipalities invested the most money in the category of culture and leisure. 39% (or 6,092,732 EUR) of the total amount distributed through participatory budgeting went to cultural and free-time activities. The category of public health is second in absolute terms with 3,369,786 EUR (or almost 22%) spent between 2015 and 2020. The number of projects is about two thirds lower than in the category of culture and leisure, while the average amount per project spent in the category of public health is the highest of all categories – 34,038 EUR. Our findings regarding the types of projects selected and implemented are generally consistent with the findings of Madej (Citation2019), as they involve lifestyle rather than quality of life.

Table 10. Which categories are the funds allocated to?

7. Conclusion

Participatory budgeting has gained popularity among municipalities in the Czech Republic over recent years, although only a very small part of the public budget has been spent through this instrument. Municipal indebtedness is not an obstacle to the implementation of this instrument. Municipalities that more fully utilize Index of Geoparticipation allocate more money to participatory budgeting. Municipalities that are members of HCCZ are also more generous when allocating funds to participatory budgeting. Specific small-scale projects prevail over large-scale investments due to the negligible amounts of money spent via participatory budgeting compared to the amounts spent on traditional concepts of public budgeting. The average cost of all projects was 18,455 EUR, while the median cost of all projects was 10,695 EUR. The most money allocated via participatory budgeting went to the category of culture and leisure. During the early months of 2020 Covid-19 started to spread around the country, affecting people’s lives. This also affected the utilization of participatory budgeting, as some municipalities decided to either postpone (for instance the city district Prague 10) or completely cease ongoing projects, and some decided not to implement any new projects during 2020 (as is the case of the municipality Hranice). Unfortunately, we do not have data for 2021 and 2022, which would have enabled us to see the impact of Covid-19 on participatory budgeting in the Czech Republic. The deteriorating economic situation (and thus the likely prioritization of public spending) may contribute to a possible reduction in spending on participatory budgeting. Another possible limit to the expanding utilization of public funds through participatory budgeting may be participatory budgeting fatigue. By fatigue we mean a decreasing interest in this instrument after a few years of its use. It would be interesting to obtain data about who votes in a participatory budgeting process and to see the percentage of citizens who vote, as well as their educational, age and other characteristics (as recommended by Wampler et al. in Dias Citation2018). In our further research we would like to focus on the motivations of municipalities; why they implemented participatory budgeting and whether they perceive it to be a tool for tackling social inequalities, a democratization tool or something completely different. We also believe it would be beneficial to implement a cross-national study, for example with Poland and/or Slovakia. Another area for research could focus on internal settings of participatory budgeting and possible inclusion of private finances into this tool.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 We can compare this amount with the highest value from our Czech dataset in order to illustrate its significance. According to our dataset, the highest ratio of budgeting allocated to participatory budgeting was used by the municipality Bílá Voda (inhabited by 314 citizens) in 2017. They allocated 7,596 EUR, which was 8.19% of the total budget.

2 By ‘event’ we mean one participatory budgeting incident – usually one year-long process from the beginning (ideas generation), via project selections (participatory voting) to grant awards/project realisations.

3 The Gini coefficient of the Czech Republic was 0.253 in 2019 in comparison with Brazil where the coefficient reached the value of 0.489 in the same year (World Bank Citation2021).

4 There are 289,629 citizens living in Ostrava, while in the district Poruba it is 64,727 (both as of 2018; Czech Statistical Office, Citation2021).

6 Public forum is an event promoted by HCCZ.

7 Official name is Monitor – kompletní přehled veřejných financí.

9 According to our database there were 10 participatory budgeting events in 2016 in the Czech Republic, 36 in 2018 and 92 in 2020.

10 The Czech term ‘dobrá praxe’ can be translated into English as ‘good practice’. Link to the webpage is www.dobrapraxe.cz.

11 We have not been able to secure any additional information about participatory budgeting events from 2012–2014. Therefore Table 4 starts from 2015.

12 The amount of 376,403,959 CZK (the Czech crowns) was recalculated to Euros (EUR) at the exchange rate of 24.31 CZK=1 EUR.

13 We have not been able to secure any additional information about participatory budgeting events from 2012–2014. That is why we only used data from 2015–2020.

References

- Aragonés, E., and S. Sánchez-Pagés. 2009. “A Theory of Participatory Democracy Based on the Real Case of Porto Alegre.” European Economic Review 53 (1): 56–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2008.09.006.

- Avritzer, L. 2017. “Participation in Democratic Brazil: From Popular Hegemony and Innovation to Middle-Class Protest.” Opininao Pública, Campinas 23 (1), https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-0191201723143.

- Bardovič, J., and J. Gašparík. 2021. “Enablers of Participatory Budgeting in Slovakia During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Scientific Papers 29 (1), https://doi.org/10.46585/sp29011248.

- Bartocci, L., G. Grossi, S. Mauro, and C. Ebdon. 2022. “The Journey of Participatory Budgeting: A Systematic Literature Review and Future Research Directions.” International Review of Administrative Sciences 0 (0), https://doi.org/10.1177/00208523221078938.

- Boukhris, I., R. Ayachi, Z. Elouedi, S. Mellouli, and N. Amor. 2016. “Decision Model for Policy Makers in the Context of Citizens Engagement: Application on Participatory Budgeting.” Social Science Computer Review 34 (6): 740–756. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439315618882.

- Brun-Martos, M., and I. Lapsley. 2017. “Democracy, Governmentality and Transparency: Participatory Budgeting in Action.” Public Management Review 19 (7): 1006–1021. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2016.1243814.

- Burian, J., R. Barvíř, D. Pavlačka, J. Pánek, J. Chovaneček, and V. Pászto. 2023. “Geoparticipation in the Czech Municipalities: Index Based Quantitative Approach.” Journal of Maps 19 (1): 2231006. https://doi.org/10.1080/17445647.2023.2231006

- Cabannes, Y. 2004. Participatory Budgeting: A Significant Contribution to Participatory Democracy. Environment and Urbanization 16 (1).

- Carrol, C., T. Crum, C. Gaete, M. Hadden, and R. Weber. 2016. Democratizing Tax Increment Financing Funds Through Participatory Budgeting. Chicago: University of Illionis. http://www.pbchicago.org/uploads/1/3/5/3/13535542/tif-pb-toolkit-june-2016.pdf

- Czech Statistical Office. 2021. Population of Municipalities – 1st January 2021. https://www.czso.cz/csu/czso/population-of-municipalities-1-january-2021.

- de Olivero Dutra, O. 2014. Preface, [in:] Hope for Democracy. 25 years of Participatory Budgeting Worldwide.

- Dias, N., ed. 2018. Hope for Democracy: 30 Years of Participatory Budgeting Worldwide.

- Dzinic, J., M. Svidronova, and E. Markowska-Bzducha. 2016. “Participatory Budgeting: A Comparative Study of Croatia, Poland and Slovakia. Network of Institutes and Schools of Public Administration in Central and Eastern Europe.” NISPAcee Journal of Public Administration and Policy 9 (1): 31. https://doi.org/10.1515/nispa-2016-0002

- Ewens, H., and J. Voet van der. 2019. “Organizational Complexity and Participatory Innovation: Participatory Budgeting in Local Government.” Public Management Review 21 (12): 1848–1866. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2019.1577908.

- Fung, A. 2006. “Varieties of Participation in Complex Governance.” Public Administration Review 66 (s1): 66–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00667.x.

- HCCZ (Healthy Cities of the Czech Republic). 2022. “Dobrá praxe.” https://dobrapraxe.cz/cz/priklady-dobre-praxe.

- Hrabinová, A., K. Babiaková, and E. Balážová. 2020. X+1 otázok a odpovedí o participatívnom rozpočte. Úrad splnomocnenca vlády SR pre rozvoj občianskej spoločnosti. ISBN: 978-80-89051-60-1.

- Institute H21. 2017. Realizované projekty participativního rozpočtování v ČR: Komparativní analýza 19 měst, městských částí a obvodů k roku 2017.

- Kempa, J., and A. Kozlowski. 2020. “Participatory Budget as a Tool Supporting the Development of Civil Society in Poland.” Journal of Public Administration and Policy 8 (1): 61–79. https://doi.org/10.2478/nispa-2020-0003.

- Krenjova, J., and R. Raudla. 2018. “Policy Diffusion at the Local Level: Participatory Budgeting in Estonia.” Urban Affairs Review 54 (2): 419–447. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087416688961.

- Kukučková, S., and E. Bakoš. 2019. “Does Participatory Budgeting Bolster Voter Turnout in Elections? The Case of the Czech Republic.” NISPAcee Journal of Public Administration and Policy 12 (2): 109–129. https://doi.org/10.2478/nispa-2019-0016.

- Lésniewska-Napierała, K., and T. Napierała. 2020. “Participatory Budgeting: Creator or Creation of a Better Place? Evidence from Rural Poland.” Bulletin of Geography. Socio-Economic Series 48: 65–81. https://doi.org/10.2478/bog-2020-0014

- Local Government Association. 2021. Participatory Budgeting. https://www.local.gov.uk/topics/devolution/devolution-online-hub/public-service-reform-tools/engaging-citizens-devolution-5.

- Madej, Malgorzata. 2019. “Participatory Budgeting in the Major Cities in Poland – Case Study of 2018 Editions.” Politics in Central Europe 15 (2): 257–277. https://doi.org/10.2478/pce-2019-0017.

- Makowski, K. 2019. “Participatory Budgeting in Poland AD 2019: Expectations, Changes and Reality.” Polish Political Science Yearbook 4 (48): 642–652. https://doi.org/10.15804/ppsy2019409.

- Milosavljević, M., Ž. Spasenić, S. Benković, and V. Dmitrović. 2020. “Participatory Budgeting in Serbia: Lessons Learnt from Pilot Projects.” Lex Localis – Journal of Local Self-Government 18 (4): 999–1021. https://doi.org/10.4335/18.3.999-1021(2020).

- Ministry of Finance of the Czech Republic. 2022. Monitor - přehled veřejných financí. https://monitor.statnipokladna.cz/.

- Pánek, J., ed. 2022. Geoparticipatory Spatial Tools. Local and Urban Governance. Cham: Springer. ISBN 978-3-031-05546-1.

- Pánek, J., V. Pászto, J. Burian, J. Bakule, and J. Lysek. 2021. “What is the Current State of Geoparticipation in Czech Municipalities?” GeoScape 15 (1): 90–103. https://doi.org/10.2478/geosc-2021-0008.

- Participatory Budgeting Project. 2021. What is PB? https://www.participatorybudgeting.org/.

- Sintomer, Y., C. Herzberg, and A. Röcke. 2008. “Participatory Budgeting in Europe: Potentials and Challenges.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 32 (1): 164–178. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2008.00777.x.

- Sześciło, D. 2015. “Participatory Budgeting in Poland: Quasi-Referendum Instead of Deliberation.” Croatian and Comparative Public Administration 15 (2): 373–388. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.875.6458&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

- World Bank. 2021. “Gini Index.” The World in Data. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI?end=2021&most_recent_year_desc=false&start=2017.