ABSTRACT

This paper explores the effectiveness of regional intervention strategies aimed at enhancing ‘low-tech’ SMEs’ sustainable competitive advantage and innovation activities, employing the food sector in Wales (UK) as a case study. It utilizes the triple helix model to analyse these interventions, emphasising collaboration between government, academia, and industry to stimulate knowledge-based economic development. The food sector represents an ideal subject for innovation-focused regional development policies because of its global importance, sustainability concerns, health impact and economic outcomes. A mixed-methods longitudinal case study approach was taken, evaluating a series of intervention programmes over an extended period (12 years in total), all funded by the European Union via the Welsh Government. Data sources included program reports, management committee reports, interviews, and case study testimonials. Frequent intervention activities included quality systems development, technical support, and skills training. They notably improved product and processing innovation for SMEs, key performance indicators revealing over 1,800 new products, safeguarding around 2,300 food sector jobs, and supporting 64 new business start-ups. Findings emphasized the value of consistent policies over an extended time period, albeit with the potential for lock-in effects. Future programme goals should be adapted for broader sustainable development outcomes – these are not uniquely Welsh challenges.

1. Introduction

Universities and their knowledge are key stimulants and foci of successful strategies for a knowledge-based economy; engaging in an active role in economic development (Pugh Citation2017), with partnerships that match the demands of the local economy. In respect of partnership collaborations, universities are recognized as being ‘unique actors’ in supporting economic development via the production of new knowledge (Fabiano, Marcellusi, and Favato Citation2020). In attempting to support the regional economy, Brem and Radziwon (Citation2017) suggested that governments stimulate ‘triple-helix’ collaboration between local firms, universities and regional institutions, focused on enhancing innovation-related activities through the cooperation of joint resources, priorities and solutions (Brem and Radziwon Citation2017; Lundberg Citation2013). In essence, using the triple-helix model as a design reference for policies to reinforce knowledge-based economic development (Rodrigues and Melo Citation2013).

In parallel, the food sector is a compelling subject for the study of innovation-focused regional development policy due to its sustainability and environmental concerns, impact on health and nutrition, and economic significance. Innovations in the food sector can address these issues and influence consumer preferences, cultural aspects, and global trade (Isaksen and Nilsson Citation2013; Manniche and Sæther Citation2017; Moragues-Faus, Sonnino, and Marsden Citation2017). The COVID-19 crisis and concerns related to food security and supply chain resilience have brought these issues into even sharper focus. Although the triple helix model has been used as a tool for national food policy and regional food sector development within Europe (exemplified by the 2003–2013 Vinnova Winn Growth programmes, developed to enhance renewal of the southern Skäne region of Sweden’s mature food industry), the evidence on its actual impact is rather scarce (Frykfors and Jönsson Citation2010). In terms of developing food policy for the European Union (EU), the sector’s importance was reflected in its status as both the largest importer and exporter of food products when it was benchmarked by the European Commission back in 2007 against the United States, Australia, Brazil, and Canada. Yet, its competitive position was weaker than the competitors, having slower growth in value-added and export volumes. Unlike larger firms, food sector SMEs had more challenges to navigate, such as legislative uncertainty, increasing retailer power, environmental policies, and raw material quotas (European Commission Citation2007). To overcome the then competitive weakness, the EU utilized the European Agricultural Rural Development Funds (EARDF) 2007–2013, and again for 2014–2020, to provide support to member states to develop and strengthen their food sectors (Campos and Coricelli Citation2017), via regional Rural Development Programmes (RDPs) that were predicated on triple-helix interventions, analogous to the Welsh case presented in this paper.

Since the inception of the EARDF in 2007, the landscape of the food sector has much changed; Moragues-Faus, Sonnino, and Marsdens' (Citation2017) European food system vulnerabilities study identified both the current main global drivers of change and those forecasted to 2050 as climate change, consumption patterns, population growth and technological innovation. Study participants included a representative range of triple helix stakeholders and experts from all phases of the production process. In the UK, food sector vulnerabilities were also compounded from 2016 onwards by BREXIT uncertainties around food legislation, quality and standards, the question of subsidies and a loss of migrant labour (Lang, Millstone, and Marsden Citation2017). Such vulnerabilities negatively affected the food manufacturing labour productivity GVA% and the health and prosperity of the nation more generally. The UK maintains the devolved regions of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland with their own distinct legislatures (Cooke and Clifton Citation2005) and policies; hence one region, Wales, was selected to be examined in depth, as it used direct rural development plan EARDF RDP funding for food sector development over an extended period. Moreover, low-technology SMEs have typically been neglected in the assessment of innovation policy, which is a knowledge gap. While there have been substantial development initiatives in the Welsh food sector over an extended period (12 years in total), a comprehensive analysis within an overarching framework has been lacking. This gap in evaluation hinders our understanding of their effectiveness and their potential applicability in broader contexts, thus limiting the scope for broader learning.

To this end, the key research question posed here is what is the effectiveness of RDP-funded triple helix programmes designed for food and drink manufacturing and processing (FDMP) small to medium enterprise (SME) development. In addressing it, the objectives are to determine firstly, where the tripartite delivery activities aligned with food sector strategies and funding aims and secondly where they contributed to regional policies for growth and sustainable development. A unique longitudinal enquiry is presented that initially details the role of the triple helix model and its application to regional food policy and sectoral development. It then progresses through the framework of evolving regional policies, sectoral strategies, funding programmes, and subsequent triple helices developed as knowledge transfer interventions for FDMP SMEs. Following the presentation of these results, the conclusions focus on the implications for policy and for research both within Wales and the food sector specifically but also more generally across other sectors and geographies. In essence, triple-helix-based interventions in the Welsh food sector have been largely successful, and demonstrate the value of policy persistence over a sustained timeframe. Moreover, succession planning from one policy programme to another is key – this is an argument for a consistent delivery mechanism, but conversely, this may also create the potential for lock-in, which needs investigating further. Going forward, economy-focused programme goals need adapting for broader sustainable development outcomes. Wales is well-placed to do this with its unique Well-being of Future Generations legislation, but this is as yet underdeveloped at an operational level.

2. Theoretical background and food industry context

This following section introduces the concept of the triple helix in relation to sectoral development and innovation policy in general, and then to the food sector in particular. It concludes with a review of the industry in the Welsh case and the associated policy climate of the last two decades.

2.1. The triple helix strategy

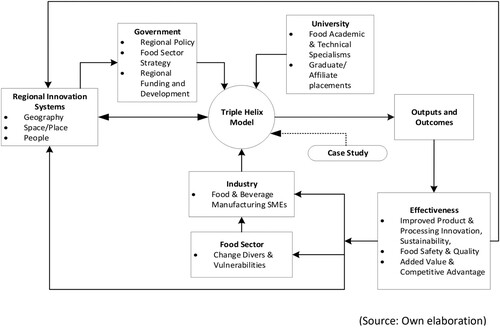

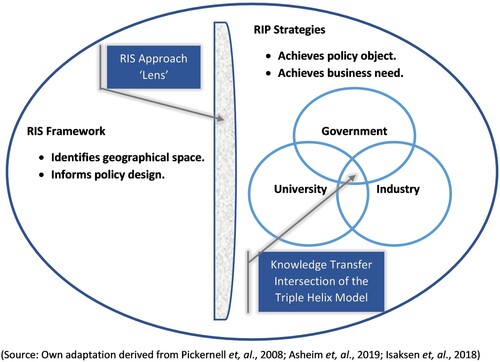

Generally, SMEs have relatively little formal R&D due to resource constraints. Moreover, they rarely define their practices as innovation, which often remains unreported or ‘hidden’ (Harel, Schwartz, and Kaufmann Citation2019). This is particularly common among SMEs in Low and Medium-Tech industries, which have typically been neglected by innovation studies (Clifton et al. Citation2020). Government-funded collaborative knowledge transfer initiatives, defined as triple helix partnerships, were determined by Etzkowitz (Citation2008) as an innovation model to encourage entrepreneurship and develop regional economic growth. Interactions among the three spheres of university, industry, and government were identified as key to realising the potential of the regional knowledge base (Cai and Etzkowitz Citation2020). The triple helix was further described by Asheim, Isaksen, and Trippl (Citation2019) as being an operationalization of a Regional Innovation System (RIS), as an explicit regional innovation policy (RIP). Isaksen, Martin, and Trippl (Citation2018) develop RIS as a widely used and powerful framework for identifying unequal geographical space for innovation and subsequent policy design for regional economies. In addition to achieving policy objectives, the triple helix model also can achieve specific business needs where knowledge transferred at the intersection of the partnership benefits all parties (Pickernell et al. Citation2008). This is outlined in ; knowledge transfer occurs at the intersection of the triple helix, with policies informed through the ‘lens’ of the RIS approach.

Figure 1. Transfer of knowledge in a triple-helix partnership between government, university, and industry.

It is this knowledge transfer intersection that brings together businesses, scientists and academia at various levels and increases competitive advantage for all, as a result of continuous knowledge transfer via the multiple channels within the collaborative partnership (Cheng Citation2021; Nielsen and Cappelen Citation2014).

Knowledge Transfer Partnerships (KTPs) are an example of such partnerships, employing graduates with university support, with an expectation that the graduate/affiliates are employed with the host company at the end of the partnership (Technology Strategy Board Citation2013). Gertner, Roberts, and Charles (Citation2011) discussed how graduate placements nurtured the relationship between the university and the company where mutual engagement, joint enterprise and shared repertoires collaborate for successful knowledge transfer, concluding that frequent and personal interactions are vital for success. For example, universities benefit from their opportunity to apply academic research to the industrial environment, something that potentially lies outside academics’ ‘comfort zone’ (Wynn and Jones Citation2017). The placement in new surroundings acts as a catalyst for knowledge transfer (Nielsen and Cappelen Citation2014) and allows universities to facilitate knowledge application to solve problems and improve competitive advantage (Cheng Citation2021). From this perspective, the graduate/affiliate gains innovation experience and knowledge in addition to a supported and structured industrial placement that prepares them for a fast-tracked career (Nielsen and Cappelen Citation2014). By transferring individuals to a business, their embedded knowledge is transferred, with labour mobility resulting in breakthrough knowledge (Bekkers and Freitas Citation2008; Fabiano, Marcellusi, and Favato Citation2020).

2.2. The food sector and knowledge linkages

The food industry sector was identified by the European Commission as the largest manufacturing sector in the EU and one of its main economic drivers (Baregheh, Hemsworth, and Rowley Citation2014). Yet, the industry faced demands for safer and higher quality products with increased external competition (Braun and Hadwiger Citation2011), and evolving consumer needs resulting in shortened product lifecycles and a competitive race for retail shelf space (Saguy and Sirotinskaya Citation2014). Nielsen and Cappelen (Citation2014) highlighted that to remain competitive in such an environment, firms must constantly improve their customer offer, be open to change and willing to innovate. Innovation in food and drink manufacturing falls into the two predominant categories of product and processing (Muscio and Nardone, Citation2012). Product innovation includes food safety, nutrition, sensory features, and convenience, whilst process innovation encompasses reduced input use, environmental impact, and increased productivity. Product and processing innovation decisions require organizational change derived from new knowledge and the capacity to implement it (Aalbers, Dolfsma, and Koppius Citation2013).

Braun and Hadwiger (Citation2011) identified the growing importance of external knowledge, particularly from universities, for food sector SMEs seeking process improvements. The research of Baregheh, Hemsworth, and Rowley (Citation2014) suggested that while food companies are low-tech relative to other sectors, knowledge transfer requirements tend to be sector-specific with a focus on food manufacturing. Companies with low technological intensity are typically (Carpio-Gallegos and Miralles Citation2018) characterized by the gradual adoption of innovation and incremental improvement of their products according to market demand; they focus on production efficiency, product differentiation and marketing. Abbate, Cesaroni, and Presenza (Citation2021), studying the Italian wine industry, determined that low-technology industries remain neglected by marketing and innovation studies, with SMEs in these sectors lacking the absorptive capacity for external knowledge use. However, this traditional view of the sector has begun to change in recent years with shifting requirements in food demand around safety, quality, and the globalization of demand (Baregheh et al. Citation2012; Minarelli, Raggi, and Viaggi Citation2015). Welsh food sector SMEs faced these challenges within a food system heavily reliant on both imports and exports due to its narrow specialization on meat and dairy products driven by climate and topography (Bowman et al. Citation2021). Regional policy that included socio-cultural reform objectives in terms of quality and public health (Bowman et al. Citation2021; Sanderson Bellamy and Marsden Citation2020) added to these challenges.

2.3. Food manufacturing and production in Wales – support policy overview

As a devolved nation within the UK, Wales constitutes an instructive case study, characterized by a ‘persistent gap in prosperity’ compared with UK and European regions in relation to GVA per capita with challenging socioeconomic circumstances (Jones, Goodwin-Hawkin, and Woods Citation2020). Its economy had traditionally been dominated by the heavy industries of coal and steel, in the southern urban districts of Swansea, Newport, and the South Wales Valleys, with Mid and North Wales being more rural and agricultural and Cardiff as the administrative centre and former port for coal exportation. Replacement industries have been typified by service sectors and light manufacturing (Henderson Citation2020). To provide some context, prior to the inception of the EARDF 2007 - 2008 period, manufacturing labour productivity as a proportion of GVA had declined year-on-year (2000–2006) from 20.7% to 16.2%. However, food manufacturing maintained a steady average of 2.3% of GVA over the same period (Office for National Statistics Citation2021). Moreover, unlike the UK as a whole, Wales’s labour productivity over the same period saw food manufacturing leading growth in comparison to other sectors.

Since devolution, the Welsh Government devised sectoral strategies to increase SME competitiveness with the intention of boosting productivity and sustainable growth in conjunction with environmental and well-being considerations. Thus, Henderson (Citation2020) regards Wales as pursuing new regional pathways via innovation policy intervention. This was in alignment with One Wales-A progressive agenda for the government of Wales (2007), One Planet, One Wales-The Sustainable Development Scheme of the Welsh Assembly Government (Citation2009) and ultimately the Well Being of Future Generations (Wales) Act (2015). The latter Act aims to promote sustainable development and improve the well-being of present and future generations by setting seven well-being goals and guiding public bodies to consider long-term implications in their decision-making processes. plots the progression and development of four food sector interventions for SMEs from policy inception through to delivery.

Table 1. Welsh government policy driven food sector intervention framework 2007 – 2020.

The framework shows an overview of the broader policy landscape within which triple helix intervention initiatives for the food sector were developed. The key themes were economic growth from improved business innovation and performance, whilst maintaining sustainability considerations for the environment, rurality and health of the nation, all within an over-arching governance structure. Recognising the benefit of strategic sectoral investment in agri-food processing, and by initially using the EARDF RDP 2007–2013 funding, the Welsh Government developed a bespoke Processing and Marketing Grant Scheme (PMG) 2007–2013 (Senedd Wales Citation2007), for food sector growth. These initiatives also had an ability to indirectly improve GVA per head by the multiplier effects (Domański and Gwosdz Citation2010) on other manufacturing and service sectors associated with food SME inputs and outputs.

The PMG scheme funded the £4.3 m Knowledge Innovation Technology Exchange (KITE) food manufacturing intervention (2008–2015) in partnership with the ZERO2FIVE Food Industry Centre (Welsh European Funding Office Citation2016). In the following years between 2015 and 2020, the Welsh government provided >£11.8m for three more SME triple-helix food sector development interventions led by ZERO2FIVE. These interventions included the Food Innovation Rapid Response (FIRRP) programme, the Barriers to Accreditation (BTA) project and Project HELIX, in the main funded by EARDF RDP (Wales) 2014–2020 which also contained priorities to tackle poverty, increase resource efficiency and supporting the shift towards a low-carbon and climate-resilient economy (European Agricultural Fund Citation2014). To support this, the Towards Sustainable Growth: Action Plan 2014–2020 for the food and drink industry (see, ) was initiated, with the overall objective to grow sales of the Welsh food and drink sector by 30%, to £7b by 2020, with a corresponding growth of 10% in GVA (Welsh Government Citation2014).

3. Methods and research questions

Despite significant development programmes for the food sector in Wales over an extended time period, these have not been analysed holistically in relation to an over-arching framework, which limits understanding of their effectiveness, and their applicability in other contexts and therefore more generalizable learning. An in-depth case study was therefore aimed at determining the effectiveness of such a model in the region; to include the identification of how the design and delivery activities supported relevant regional policy and sectoral strategic aims.

The key research question posed here is what is the effectiveness of RDP-funded triple helix programmes designed for SMEs’ development. In addressing it, the objectives are to determine firstly, where the tripartite delivery activities aligned with food sector strategies and funding aims and secondly where they contributed to regional policies for growth and sustainable development. Wales constitutes the case study for this research, as a region with significant reliance on the food sector, an economy transitioning away from a heavy industrial base and seeking to increase the performance of its food manufacturing sector. It is also an asymmetrically devolved entity within a larger nation-state, with significant yet constrained regional policy-making scope. The framework employed here for applying the research question and collecting data from relevant stakeholders and sources within the Welsh case study is shown in .

To fulfil the research aims, the methodology was designed as a triangulated qualitative and quantitative mixed methods approach to increase reliability and validity (Yin Citation2009). It was initiated with a review of the literature to identify the constructs of university-led triple helices as a conduit for enacting food sector strategies. Regional policies for Wales were then assessed to identify the rationale for the ensuing food sector development strategy. This led to a review of EU, UK and Welsh Government reports and strategies for food sector development to identify similar or differing priorities. EU/Welsh Government regional development plans applicable to the period in question supplied an understanding of the objectives of the triple helices, and the subsequently developed output measurements. These focused on intermediate outcomes e.g. accreditation and quality standards, and more direct indicators, such as new product developments and where available term job creation. Conversely, data was sparse on broader sustainable development indicators (an issue discussed further in the concluding section). To increase the study validity, further understanding of how SMEs required ongoing support from triple helix interventions was obtained from semi-structured interviews conducted with SME managing directors (approximately 30 min each, n = 4). The selection criteria here was their involvement in multiple intervention partnerships (n = >14), with each representing a different food sector category, i.e. ready-to-eat meals, dairy, meat and fresh produce. Interviews covered specific industry needs in relation to programming and planning; changes to SME operation practices; new knowledge and capabilities; benefits of the triple helix model and its impacts on the business. Parallel interviews were conducted with the ZERO2FIVE’s technical delivery managers (circa 40 min each, n = 6) to establish corroborations or differences. Available media and case studies testimonials (n = >30) and funder highlight reports (n = 44) were also accessed. Data was then analysed using NVivo software for a content analysis approach according to SME perceived vulnerabilities and change drivers. The main groupings emerged as product and processing, with sub-nodes consisting of ongoing industry support, improvements in food safety, quality management, technical barriers, skills gaps, navigating legislation and adding value.

In addition, each of the (n = 4) consecutive programme closure reports (KITE, FIRRP, BTA and HELIX) provided key performance indicators, outputs and impact outcomes, for alignment with funders’ aims. The data provided in the closure reports was compiled from the ZERO2FIVE operations support and technical delivery teams who used data from local management committee quarterly minutes and reports, business review meetings and SME intervention completion documents (n = >840). The SME intervention documents were compiled throughout delivery, which totalled 510 SME-partnered interventions over the 12-year period.

4. The triple helix-based intervention programmes – findings and review

The following section presents a review of the triple helix intervention programmes within Wales over the previous two decades, outlining their key aims, delivery mechanisms and outcomes within the broader regional policy framework.

4.1. Triple helix FDMP support pre-2008

Prior to 2008, the available options for SMEs to improve productivity through upskilling and innovation knowledge transfer were to commission costly private consultancy services or participate in government-funded KTP schemes. KTPs involve a graduate assigned to a university academic supervisor being placed in a business in order to transfer knowledge for a duration of 12–36 months depending on the business need. Despite KTPs costing less than consultancy, they incur a contribution fee from the business in the region of £35,000 per annum (UK Government Citation2021). The costs were prohibitive for financially constrained FDMP SMEs, resulting in a low take-up and between 2003 and 2008 only 6 SME partners had engaged with ZERO2FIVE (KTP Online Citation2021).

4.2. The KITE triple helix 2008–2015

The KITE project was developed in 2008 to incorporate enhancements in technological and food science/safety skills, reverse the reported decline of food technologists in Wales, improve business performance, food safety/science and technical compliance, and meet the food sector’s critical need for sustainability through innovation (Redmond Citation2013). It aimed to exploit the knowledge base in food technology for commercial gain and had output metrics aligned with the RDP Processing and Marketing Grant Scheme 2007-2015, see . The programme had tailored interventions ranging in duration from three months to a year, dependent on the specific knowledge transfer requirements of the SMEs, for example, food safety, legislation, technical issues or product reformulation/innovation. The contribution cost to the programme from the SME partners equalled a KTP, but the flexible time frames made engagement more affordable for firms (Mayho et al. Citation2023).

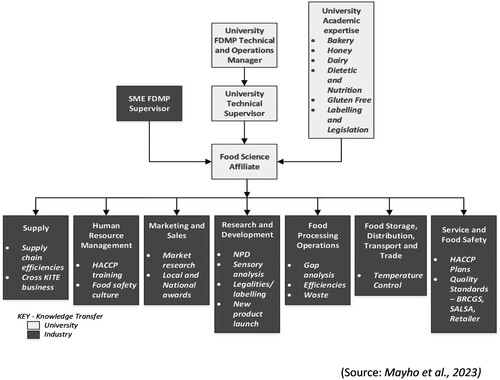

With its use of a graduate/affiliate placement, KITE aimed to achieve its output objectives of increased SME turnover, increased numbers of new products entering the competitive marketplace and improved employment numbers. The graduate/affiliate role was designed to encompass knowledge transfer to the primary and support activities of the SME microenvironment (). Primary activities were categorized as research and development, processing operations, storage, distribution and logistics, service and food safety, with support activities grouped as inward supply, human resources, marketing and sales. Firms could ‘mix and match’ activities across the categories as determined by their business needs. Selected activities were supplemented by technical and academic product and process knowledge, with delivery intervention options that included product-specific science, dietetic and nutrition, allergen, labelling and legislation expertise; some examples being salt/sugar reduction and nutritional analysis. Added value for the firms was to be gained from upskilling to supply safe and legally compliant products to the wholesale, retail and export markets. In addition, gains were also made from newly developed products for supply, operational waste reduction and processing control systems. Whilst the model was developed specifically for KITE, the adaptable framework became the basis for subsequent food sector development interventions.

To understand how the triple helix food sector intervention impacted regional development, the KITE project incorporated cumulative five-year tangible outputs as determined by the PMG scheme such as increased sales, job creation, adding value for waste products and NPD (new product development). These sector outputs were designed to align with the sustainability principles of the then One Wales – a progressive agenda for the Government of Wales 2007 policy (as seen in ), to create jobs across Wales, improve health and nutrition, develop economic prosperity from full employment and skills, enhancing skills and stimulate business growth. The policy’s derived Food and Drink Strategy for Wales 2008–2010 aimed to foster innovation and improve knowledge of market trends, consumer behaviour and business performance in response to changing market conditions. It introduced in part some of the broader Future Generation goals as seen in the One Wales – One Planet 2009 policy which subsequently morphed into the sustainability and well-being goals of the Food for Wales: Food from Wales 2010–2020 strategy.

At the firm level output and outcome metrics deemed by the business as being directly attributable to the triple helix programme were obtained from partner SMEs MDs/Owner-operators, on a monthly basis until the technical delivery ended, then cumulatively calculated by the project data collection team at the end of KITE. During the period, KITE totalled 43 industry partners across the nation, and engaged with 97 SME interventions. Of these interventions, 78 achieved 89 key performance indicators (KPIs) of food safety quality certifications such as Brand Reputation Compliance Global Standards (BRCGS) and Safe and Local Supplier Approved certifications (SALSA) which facilitated entry to new leading retailer and export markets, supporting the policy aims to stimulate enterprise and business growth (see ).

Table 2. KITE project outputs, outcomes and KPIs.

The SME managing directors showed a positive response to KITE (see ), with the key theme being that the knowledge transfer from the partnership enabled quality certification for business development and in turn added value.

Table 3. KITE SME partner testimonials.

At the close of the project, SMEs reported a cumulative £103 m in increased sales, with increased food safety and quality playing a central part. Improved performance in NPD resulted in 1,462 new products destined for existing and new markets (Bradley and Hill Citation2016), > 500 supplied to 16 leading retailers, for example in the UK, Tesco, Waitrose, Morrisons etc.; in Ireland, Dunnes and Superquinn, and Lidl in Europe. The partnered firms also reported 692 new jobs created and 1,197 jobs safeguarded in the primary and food industry sectors. Significantly, this represents around 3% of total employment in these sectors (Bradley and Hill Citation2016). There was a reported reduced wastage of £1.3 m, in the main from efficiencies for accurate weight measurements and reduced packaging. From the reported outputs and outcomes, it was observed that KITE satisfied the requirements of the EARDF RDP 2007–2013 and achieved what it originally aimed to do – ‘to exploit the knowledge base in food technology for commercial gain’. Yet, this narrow commercial focus was a potential weakness going forward against the wider projected future food system vulnerabilities and change drivers.

In due course, the adoption of the KITE approach of industry and academic collaboration with graduate placement was included in the actions of the Towards Sustainable Growth: an Action Plan for the Food and Drink Industry 2014–2020. It was then acknowledged in the following EARDF RDP (Wales) 2014–2013 as demonstrating how academic underpinning is essential to the success of the project as a means to transfer the latest knowledge and technical know-how to the sector (European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development Citation2014). Towards the completion of KITE, the Welsh Government/EU funded further knowledge transfer support for SMEs with the £12.8 m Project HELIX designed as a further enhanced triple helix collaboration, to continue to deliver technical and food safety/science knowledge transfer to the nation’s SMEs (Mayho, Redmond, and Lloyd Citation2019), see 4.4.

4.3. The FIRRP triple helix 2015–2016

In 2015, whilst Project HELIX underwent development and set-up, FIRRP became available for SMEs in the intervening year between the triple helix programmes to provide a bridge for academic knowledge transfer between the KITE programme and Project HELIX. This was in part attributable to Redmond’s (Citation2013) mid-term evaluation of the KITE programme, which recommended a seamless transition between funding streams to provide critical technical knowledge transfer support, especially in light of the new BRCGS Standard 7 to be launched in January 2015.

The ZERO2FIVE Food Industry Centre reported that the changing landscape for the food sector resulted in technical knowledge gaps in areas such as food safety, quality management systems, legislative challenges in packaging and shelf life, and NPD for new market growth. The findings highlighted that without further Welsh Government funding, SMEs would have had to resort back to either expensive consultative or KTP knowledge transfer (ZERO2FIVE Citation2015a). The design of FIRRP was to provide a technologist to address knowledge gaps and did not require a financial contribution from industry; especially relevant at a time when output growth for the sector slowed and production input costs increased to include the national living wage and rising fuel costs, coupled with BREXIT uncertainty (Food and Drink Wales Citation2015). The programme engaged with 47 Welsh SMEs and partnered in 123 interventions to deliver technical and food safety/science-facilitated knowledge transfer and reportedly enabled an increased turnover of £8 m (Lacey and Taylor Citation2016). FIRRP helped the SMEs retain vital certification standards such as BRCGS and incremented NPD to access new markets, (see ).

Table 4. FIRRP outputs and outcomes.

In the latter part of 2015, ZERO2FIVE identified a range of barriers to food safety standards certification. The barriers faced by SMEs included associated costs, increased paperwork and SMEs’ confusion over the differing certification schemes available (>30) (Evans, Lacey, and Taylor Citation2022). An appropriate pathway to obtaining BRCGS was to first engage with SALSA certification, hence the Welsh Government/EU-funded Barriers to Accreditation (BTA) project being developed and initiated. The project engaged with interventions in 8 SMEs; of these, 6 businesses gained SALSA certification from the support packages facilitated by the BTA project. HELIX then integrated the knowledge transfer support package model developed by the BTA into its delivery – at the completion of HELIX, a further 18 Welsh SMEs had engaged with 27 SALSA interventions.

4.4. Project HELIX 2016–2020

In alignment with the Towards Sustainable Growth: Action Plan 2014–2020 (see ) and to extend the provision of support to include process engineering, packaging and market distribution, a series of ZERO2FIVE stakeholder, academic and technical delivery consultations were held. This resulted in the HELIX programme expanding on the previous KITE support offered to Welsh SMEs and provided eighteen knowledge transfer activities ternary grouped as ‘Food Strategy’, ‘Food Efficiency’ and ‘Food Innovation’.

HELIX was re-modelled on KITE’s success of long-term knowledge transfer with graduate/affiliate placements (known as Product 3) but went on to include the additional mechanisms of short-term diagnostics (Product 1) and mid-term knowledge transfer (Product 2). Tripartite consultations introduced the concept of the graduate/affiliate moving from SME to SME (dependent on specific task requirements), instead of undertaking their placement in a single company for the duration of the intervention. This mobility enabled the graduate/affiliate to significantly increase their personal skills base and allowed for a better and faster transfer of industry knowledge and skills from company to company increasing the knowledge spillover effect of the programme.

At the completion of HELIX, this expanded model of engagement resulted in 283 combined Product 1, 2 and 3 delivery interventions, in 149 firms with the vast majority (121 enterprises) receiving a significant intervention (7 or more hours). SMEs’ managing directors exhibited a positive response to the initiative for technical and food safety/science-facilitated knowledge transfer (see ). From the partner testimonials, the key theme identified was their technical knowledge gap for food safety skills and focus on obtaining food safety certifications in the same vein as the prior KITE, highlighting industry’s focus on commercial success rather than wider food system vulnerabilities and change drivers.

Table 5. Project HELIX SME partner testimonials.

The HELIX outputs, outcomes and KPIs metrics were collected by the ZERO2FIVE data team for Products 2 and 3, (Product 1 being too short term to evaluate) and were measured and reported (by the SME operator) as being a direct consequence of the partnership at the intervention closure. The results were cumulatively totalled to measure the success of the programme and reported 214 new jobs created, and 129 new markets accessed. The project’s key performance indicators included 1,120 jobs safeguarded, the development of 305 new products and 89 instances of food safety quality certifications such as BRCGS (see ). Examples of delivery activities include nutritional analysis of dietetic foods, developing gluten, dairy and meat-free foods, control analysis for levels of protein in milk products destined for school children and new product development from alternative sources of insect protein. At the time of writing, however, final Welsh Government/EU programme evaluations were not yet available, meaning output metrics are presumed to be calculated as gross (UK Government Citation2014), rather than net.

Table 6. Project HELIX outputs, outcomes and KPIs.

Throughout the project, the SMEs reported the key output of >£96.5 m increased product sales, contributing to the Welsh Government’s strategic target of a £7b turnover for the sector (Welsh Government Citation2020). While not directly attributable, labour productivity GVA for food manufacturing overall incremented from £872 m in 2008 to £1,370 m in 2019 (StatsWales Citation2021), revealing increased manufacturing efficiencies (Jackson Citation2017).

4.5. Summary

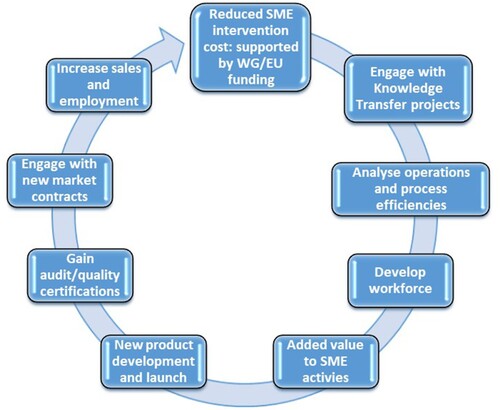

Welsh Government/EU continual funding of programmes and projects between 2008 and 2020, ensured that SMEs received technical and food science knowledge transfer support for a period of twelve years that was financially viable for their organizations. Findings suggested that when knowledge transfer is channelled through triple helix activities, a continual cycle of benefits emerges that impacts the microenvironment of SMEs; from cost-effective interventions, improved internal capacity and added value, through accreditation to new product development, new markets, and broader multiplier effects (as represented in ).

SMEs that reported increased sales and jobs growth from the triple helix support for product and process innovation ultimately required greater levels of inputs, not only tertiary stock but plant, equipment, technology, distribution and maintenance, impacting supplier growth in various sector supply chains including local supply networks and direct/indirect international or global supply chains. An example of this can be seen in the bakery manufacturing sector (predominant KITE and HELIX knowledge transfer intervention category), where for each additional £1 m demand the multiplier GVA impact was determined to be £3.2 m (Office for National Statistics Citation2022). Job creation and retention ensured a flow of disposable income into other locally traded goods and services such as retail, transport, housing, building and construction, leisure and hospitality. Using the bakery sector as an example, a £1 m increase in demand creates 9.5 full-time equivalent jobs with a multiplier of 1.8, resulting in a multiplier effect of 16.8 indirect jobs created (Census21 Citation2019). Although reaching beyond individual firm performance, these measures are still broadly framed within economic outcomes, at a time when broader societal outcomes are becoming a priority for regional development and innovation policy (Laatsit, Grillitsch, and Fünfschilling Citation2022). This is particularly pertinent given the requirement to move towards the Well-being of Future Generations outcomes in Wales (Jones, Goodwin-Hawkin, and Woods Citation2020). This is a point we return to in the concluding section of the paper.

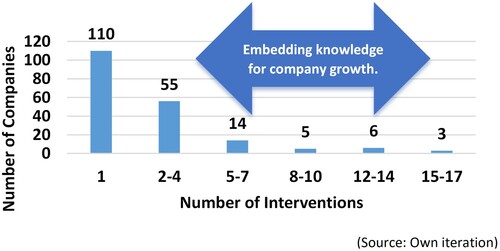

Findings also highlighted a trend of 83 SMEs engaging in two or more interventions over the twelve years. Of the 110 companies having single interventions, 73 engaged with the HELIX diagnostic Product 1 and of those, 64 were reported as new business start-ups (see ). This suggests that a financially viable pathway for businesses to engage with the triple helix model facilitated the developmental benefit cycle and aided SMEs to recognize that growth could be achieved from embedding knowledge transfer by cyclical engagement in multiple interventions. There is however a debate to be had on potential trade-offs of a multi-cycle triple helix intervention model for SMEs around dependency and displacement; again, we return to this point below.

5. Discussion and conclusions

The learnings from the case study of Wales generally conclude that university-led triple helix food sector interventions worked favourably to add competitive advantage for SMEs, particularly in improved technical and food safety/science knowledge. The attention to design, particularly in the case of the HELIX programme, developed by consultation exercises with industry, academics and technical delivery teams, negated a problematic ‘one size fits all’ approach (Pugh Citation2017) for sectoral innovation and development policy. One such example is the improved delivery options for financially constrained SME partners, which saw increasing engagements from the KITE programme to the HELIX programmes, with the inclusion of fledgling start-up businesses. With regard to knowledge exchange, HELIX has been presented to a range of international policy makers (e.g. Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, China). The triple helix food intervention concept more broadly has been presented in Austria, Holland, Italy and Denmark to policy stakeholders and academics.

SMEs recognized the benefits that can be gained from comparatively low-priced knowledge transfer interventions to support product and/or process innovation, identifiable by their multiple partnership interventions over the 12-year period. The use of FIRRP and BTA as transition projects between the close of KITE and the start of project HELIX saw a continual knowledge transfer support option that produced a cycle of benefits for SMEs that maximized contributions towards achieving economic growth targets (Welsh Government Citation2010 and 2014) and uninterrupted access to university-based knowledge. However, there are now contradicting change drivers at play for these SMEs following the post-BREXIT loss of EU funding support. For example, the UK is a net importer of food and the new Atlantic and Indo-Pacific trade agreements will have implications for food safety, legislation, animal welfare and environmental impacts (Smith Citation2023). More specifically with regard to the Welsh food sector, while potentially able to source cheaper inputs from non-EU countries, conversely Welsh producers are exposed to lower cost global competition. While the balance varies by subsector, relative to the UK as a whole a high proportion of Welsh food and drink exports were previously dependent on EU markets. There are also issues related to workforce availability, and the likely need in the future to better connect domestic agriculture and food policy post-BREXIT (Welsh Economy Research Unit Citation2017).

In order to gauge the wider socio-economic benefits of triple helices on Welsh policies it is recommended that improvements are made to measure the ‘hidden innovation’ associated with food sector products and processing for future food sector triple helix initiatives. A greater focus on business model innovation – accelerated by necessity within the food and hospitality sectors during the COVID-19 pandemic but persisting afterwards – would be beneficial. A further recommendation is to expand the triple helix model to include interventions with large FDMPs as these have the production capabilities and resources to potentially make more radical advancements in innovation (Aziz and Samad Citation2016) and can make additional wider benefits for impacts on social and economic change within their localities, for example, employment levels and local manufacturing inputs. State aid rules precluded such interventions within the European-funded programmes; this is no longer an issue within the UK. However, the scale and scope of replacement ‘levelling-up’ funding streams remain uncertain, both at the Wales and UK levels and thus future targeting will likely need to be selective across all sectors (Martin et al. Citation2022). Potentially post-SME delivery intervention follow-up could also be a precursor to identifying companies with the mindset for growth potential.

As noted earlier, regional innovation systems represent the foundational institutional, organizational, and technological infrastructure of regional production systems. The RIS framework emphasizes the pivotal role of institutions, comprising routines, rules, norms, and laws, as highlighted by Lundvall (Citation1992). It implies institutions are of equal importance in fostering innovation (Asheim, Grillitsch, and Trippl Citation2016). Therefore, longstanding and iterative knowledge-based interactions as represented by the KITE to HELIX programmes are consistent with developing a stronger RIS, reinforcing coherence and unified function (Weidenfeld, Makkonen, and Clifton Citation2021).

However, on this latter point, some further research would be useful; while ostensibly a positive outcome, a counter interpretation could be such multiple interventions constitute evidence of a dependency culture, with consequent displacement of other market-based supporting services (which are in turn likely to be knowledge-based, higher value-adding services). More generally policymakers should guard against any capture of support programmes by small numbers of ‘insiders’, with the reciprocal un-critical client management of good news stories on their part. That said, a particular strength of the HELIX intervention was the introduction of peripatetic technologists which facilitated horizontal knowledge transfer between SMEs, which offers a model for similar programmes in other sectors and indeed other peripheral economies seeking to improve knowledge transfer.

Innovation outcomes were typically at the applied end of the spectrum – marketing, and process improvements; conversely, there was a relatively low rate of conversion into new products actually launched. However, the technical and food safety/science improvements in product and process activities across all interventions, ultimately contributed to the broader aims of creating jobs, enhancing employability skills, and stimulating enterprise growth. Certifications which aided FDMPs to gain supermarket contracts and thus access high consumer buying power, were particularly important in this respect. This indirectly created new technical and operational jobs and retained existing jobs counter to the reverse migration of food sector workers, loss of skills and labour shortages in Wales arising due to BREXIT (Lang, Millstone, and Marsden Citation2017). These outcomes are in isolation economic rather than addressing broader sustainable development goals; however, improved process efficiency and better collaboration within the food sector are consistent with reduced food waste and indeed progress to a more circular economy, and by extension living within environmental limits and ensuring a more health society (Tamasiga et al. Citation2022).

Moreover, we can also think of process measures (number of firms assisted, BRCGS / SALSA accreditations gained, etc) as appropriate intermediate outcomes – indicators of a direction of travel from which improved longer-term outcomes (better firms, a more competitive regional economy), can be expected. These assumed pathways from intermediate to long-term outcomes are however in need of further verification (e.g. how sure are we that improved accreditation in the short term is a valid signal of long-term competitiveness?), particularly over time as market conditions change. This would be a valuable area of further research (detailed individual firm cases for example), undertaken on a periodic basis. The ‘innovation biographies’ method could be useful here to detail the development, evolution, and impact of specific innovations, inventions, or technologies (Butzin and Widmaier Citation2016). These biographies typically trace the journey of an innovation from its inception, including the individuals or organizations involved, the challenges they faced, and the broader societal or economic effects of the innovation. More specifically, a set of post-intervention interviews post HELIX to ascertain exactly which elements of the technical/food safety and science knowledge transfer became embedded into their organizational activities, i.e. knowledge absorption and transformation (Zahra Citation2002), would be beneficial.

The study presented here does have some limitations as a case study of a single set of university-led triple helix interventions, albeit over an extended time period. In addition, recorded outcome data related to jobs is presented gross rather than the net (UK Government Citation2014). Conversely, there will likely be economic impacts beyond the food sector that are under-recorded; multiplier effects should be integrated more effectively into future policy design. Evidence on an international comparative basis, focusing on the links between actors is a priority here. Going forward, intervention programmes such as those analysed here will need to engage with sustainable development goals more directly beyond the economic; the means to do this in Wales exists within the Wellbeing of Future Generations Act and its associated indicators, but these as yet are lacking in impact at the operational level. Indeed, one of the main issues identified by Nesom and MacKillop (Citation2020) is the lack of analysis of sustainable development policy implementation at the local level. Additionally, the Act has been criticized for its vague and aspirational nature, lacking clarity in its formulation, which hampers effective implementation (ibid). These are not uniquely Welsh challenges for such frameworks (Zeigermann Citation2018). Although implicit in programmes analysed here, an explicit logic model should be developed for future interventions, to increase clarity between inputs/resources (e.g. funding, personnel, materials), activities/processes (the actions taken), outputs (direct results), and outcomes (long-term impacts). Ultimately if interventions are to be more strategic and lead to broader transformational change beyond given sectors, a broader constellation of actors will be required, also incorporating knowledge from beyond a single region. To this end, future evaluations should be more formative in approach.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the ZERO2FIVE teams for the delivery of the programmes.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required for the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aalbers, R., W. Dolfsma, and O. Koppius. 2013. “Individual Connectedness in Innovation Networks: On the Role of Individual Motivation.” Research Policy 42 (3): 624–634. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2012.10.007.

- Abbate, T., F. Cesaroni, and A. Presenza. 2021. “Knowledge Transfer from Universities to low- and Medium-Technology Industries: Evidence from Italian Winemakers.” The Journal of Technology Transfer 46 (4): 989–1016. doi:10.1007/s10961-020-09800-x.

- Asheim, B. T., M. Grillitsch, and M. Trippl. 2016. “Regional Innovation Systems: Past - Present -Future.” In Handbook on the Geographies of Innovation, edited by R. Shearmu, and D. Doloreux, 455–466. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Asheim, B, T., Isaksen, A. and M. Trippl. (2019). Advanced Introduction to Regional Innovation Systems, 29–31. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Aziz, N., and S. Samad. 2016. “Innovation and Competitive Advantage: Moderating Effects of Firm Age in Foods Manufacturing SMEs in Malaysia.” Procedia Economics and Finance 35: 256–266. doi:10.1016/S2212-5671(16)00032-0.

- Baregheh, A., D. Hemsworth, and J. Rowley. 2014. “Towards an Integrative View of Innovation in Food Sector SMEs.” The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation 15 (3): 147–158. doi:10.5367/ijei.2014.0152.

- Baregheh, A., J. Rowley, S. Sambrook, and D. Davies. 2012. “Food Sector SMEs and Innovation Types.” British Food Journal 114 (11): 1640–1653. doi:10.1108/00070701211273126.

- Bekkers, R., and I. Freitas. 2008. “Analysing Knowledge Transfer Channels Between Universities and Industry: To What Degree do Sectors Also Matter?” Research Policy 37 (10): 1837–1853. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2008.07.007.

- Bowman, A., J. Froud, C. Haslam, S. Johal, K. Morgan, and K. Williams. 2021. What can Welsh Government do to increase the number of grounded firms in food processing and distribution? p5. Accessed November 6, 2023. https://www.gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2022-07/what-can-welsh-government-do-to-increase-the-number-of-grounded-sme-firms-in-food-processing-and-distribution.pdf

- Bradley, D., and B. Hill. 2016. Wales Rural Development Plan Processing and Marketing Grant Scheme 2007-13 - Ex-Post Evaluation. Accessed July 25, 2020. https://gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2020-02/ATISN%2013697%20-%20Doc%202.pdf

- Braun, S., and K. Hadwiger. 2011. “Knowledge Transfer from Research to Industry (SMEs) – An Example from the Food Sector.” Trends in Food Science & Technology 22 (1): S90–S96. doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2011.03.005.

- Brem, A., and A. Radziwon. 2017. “Efficient Triple Helix Collaboration Fostering Local Niche Innovation Projects – A Case from Denmark.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 123: 130–141. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2017.01.002.

- Butzin, A., and B. Widmaier. 2016. “Exploring Territorial Knowledge Dynamics Through Innovation Biographies.” Regional Studies 50 (2): 220–232. doi:10.1080/00343404.2014.1001353.

- Cai, Y., and H. Etzkowitz. 2020. “Theorizing the Triple Helix Model: Past, Present, and Future.” Triple Helix Journal 7 (2-3): 1–38. doi:10.1163/21971927-bja10003.

- Campos, N., and F. Coricelli. 2017. “EU Membership, Mrs Thatcher’s Reforms and Britain’s Economic Decline.” Comparative Economic Studies 59: 169–193. . https://link.springer.com/article/10.1057s41294-017-0023-7

- Carpio-Gallegos, J., and F. Miralles. 2018. “Absorptive Capacity and Innovation in low-Tech Companies in Emerging Economies.” Journal of Technology Management & Innovation 13 (2): 3–11. doi:10.4067/S0718-27242018000200003.

- Census21. 2019. "Input-Output Analytical Tables-Type 1 FTE Effects and Multipliers reference year 2019." Accessed November 2, 2023. https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/nationalaccounts/supplyandusetables/adhocs/1254ftemultipliersandeffectsreferenceyear2019

- Cheng, E. 2021. “Knowledge Transfer Strategies and Practices for Higher Education Institutions.” VINE Journal of Information and Knowledge Management Systems 51 (2): 288–301. doi:10.1108/VJIKMS-11-2019-0184.

- Clifton, N., R. Huggins, D. Pickernell, D. Prokop, D. Smith, and P. Thompson. 2020. “Networking and Strategic Planning to Enhance Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises’ Growth in a Less Competitive Economy.” Strategic Change 29 (6): 699–711. doi:10.1002/jsc.2382.

- Cooke, P., and N. Clifton. 2005. “Visionary, Precautionary and Constrained ‘Varieties of Devolution’ in the Economic Governance of the Devolved UK Territories.” Regional Studies 39 (4): 437–451. doi:10.1080/00343400500128457.

- Domański, B., and K. Gwosdz. 2010. Multiplier Effects in Local and Regional Development. QUAGEO 29(2), 27–37. Adam Mickiewicz University Press: Poznań.

- Etzkowitz, H. 2008. The Triple Helix: University-Industry-Government Innovation in Action. New York: Routledge.

- European Agricultural Fund. 2007. Rural development plan for Wales 2007-2013.” https://ec.europa.eu/enrd/enrd-static/fms/pdf/D4BF9642-B053-1ECD-883A-14297B0DBCB1.pdf Accessed 6th November 2023

- European Agricultural Fund. 2014. United Kingdom – Rural Development Programme (Regional) – Wales, 154–156. Accessed 6th November 2023. https://gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2019-07/rural-development-programme-document-2014-to-2020.pdf

- European Commission. 2007. “Competitiveness of the European Food Industry: An economic and legal assessment.” Accessed November 6, 2023. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/3d89001e-b613-4f7f-bb27-82c4bade8a10

- Evans, E., J. Lacey, and H. Taylor. 2022. “Identifying Support Mechanisms to Overcome Barriers to Food Safety Scheme Certification in the Food and Drink Manufacturing Industry in Wales, UK.” International Journal of Environmental Health Research 32 (2): 377–392. doi:10.1080/09603123.2020.1761011.

- Fabiano, G., A. Marcellusi, and G. Favato. 2020. “Channels and Processes of Knowledge Transfer: How Does Knowledge Move Between University and Industry?” Science and Public Policy 47 (2): 256–270. doi:10.1093/scipol/scaa002.

- Food and Drink Wales. 2015. “Economic Appraisal of the Welsh Food and Drink sector – 2015.” https://businesswales.gov.wales/foodanddrink/sites/foodanddrink/files/Food%20-%20Research%20-%20Economic%20Appraisal%20-%202015%20-%20Summary%20of%20sub%20sectors%20-%20FINAL.pdf

- Frykfors, C., and H. Jönsson. 2010. “Reframing the Multilevel Triple Helix in a Regional Innovation System: A Case of Systemic Foresight and Regimes in Renewal of Skåne's Food Industry.” Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 22: 819–829. doi:10.1080/09537325.2010.511145.

- Gertner, D., J. Roberts, and D. Charles. 2011. “University-Industry Collaboration: A CoPs Approach to KTPs.” Journal of Knowledge Management 15 (4): 625–647. doi:10.1108/13673271111151992.

- Harel, R., D. Schwartz, and D. Kaufmann. 2019. “Small Businesses are Promoting Innovation!! Do we Know This?” Small Enterprise Research 26 (1): 18–35. doi:10.1080/13215906.2019.1569552.

- Henderson, D. 2020. “Institutional Work in the Maintenance of Regional Innovation Policy Instruments: Evidence from Wales.” Regional Studies 54: 429–439. doi:10.1080/00343404.2019.1634251.. https://www.wwf.org.uk/sites/default/files/202003/WWF_Full%20Report_Food_Final_3.pdf

- Isaksen, A., R. Martin, and M. Trippl. 2018. New Avenues for Regional Innovation Systems – Theoretical Advances, Empirical Cases and Policy Lessons.

- Isaksen, A., and M. Nilsson. 2013. “Combined Innovation Policy: Linking Scientific and Practical Knowledge in Innovation Systems.” European Planning Studies 21 (12): 1919–1936. doi:10.1080/09654313.2012.722966.

- Jackson, T. 2017. Prosperity Without Growth. Foundations for the Economy of Tomorrow. London and New York: Routledge.

- Jones, R., Goodwin-Hawkins, B. and Woods, M. (2020). From Territorial Cohesion to Regional Spatial Justice: The Well-Being of Future Generations Act in Wales. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 44, 894-912. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12909

- KTP Online. 2021. Accessed December 31, 2022. https://info.ktponline.org.uk/action/search/complete_res.aspx?srchtype=simple&tech=18&sic=−1&kbp=2786&loc=XX

- Laatsit, M., M. Grillitsch, and L. Fünfschilling. 2022. “Great expectations: the promises and limits of innovation policy in addressing societal challenges. Centre for Innovation Research (CIRCLE), Lund University.” http://wp.circle.lu.se/upload/CIRCLE/workingpapers/202209_laatsit.pdf

- Lacey, J., and H. Taylor. 2016. (Unpublished Results). Food Innovation Rapid Response - End of Project Report.

- Lang, T., E. Millstone, and T. Marsden. 2017. A Food Brexit: Time to get Real – A Brexit Briefing. Brighton, UK: University of Sussex Science Policy Research Unit. Accessed December 31, 2022. http://www.sussex.ac.uk/spru/newsandevents/2017/publications/food-brexit

- Lundberg, H. 2013. “Triple Helix in Practice: The key Role of Boundary Spanners.” European Journal of Innovation Management 16 (2): 211–226. doi:10.1108/14601061311324548.

- Lundvall, B-Å. 1992. National Systems of Innovation: Towards a Theory of Innovation and Interactive Learning. London: Pinter.. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1hj9zjd.9

- Manniche, J., and B. Sæther. 2017. “Emerging Nordic Food Approaches.” European Planning Studies 25 (7): 1101–1110. doi:10.1080/09654313.2017.1327036.

- Martin, R., A. Pike, P. Sunley, P. Tyler, and B. Gardiner. 2022. “‘Levelling up’ the UK: Reinforcing the Policy Agenda.” Regional Studies, Regional Science 9 (1): 794–817. doi:10.1080/21681376.2022.2150562.

- Mayho, S., E. Redmond, and D. Lloyd. 2019. Food Safety Management and Technical Innovation in Welsh Food-Sector SMEs: Impact of Project HELIX. Presentation. 33rd EFFost International Conference – Sustainable Food Systems. https://www.effost.org/effost+international+conference/past+effost+conferences/33rd+effost+international+conference+2019/default.aspx

- Mayho, S, Redmond, E., Mumford, D., and Lloyd, D. (2023). Value Chain Activities Small and Medium Food Manufacturers in Wales, United Kingdom. International Journal on Food System Dynamics. 14(1): 95–109. www.centmapress.org

- Minarelli, F., Raggi, M., and Viaggi, D. (2015). Innovation in European Food SMEs: Determinants and Links Between Types Bio-Based and Applied Economics 4(1): pp. 33-53, ISSN 2280-6180 (print) © Firenze University Press, ISSN 2280-6172 (online) doi:10.13128/BAE-14705

- Moragues-Faus, A., R. Sonnino, and T. Marsden. 2017. “Exploring European Food System Vulnerabilities: Towards Integrated Food Security Governance.” Environmental Science & Policy 75: 184–215. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2017.05.015.

- Muscio, A., and G. Nardone. 2012. “The Determinants of University–Industry Collaboration in Food Science in Italy.” Food Policy 37 (6): 710–718. doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2012.07.003.

- Nesom, S., and MacKillop, E. (2020). What matters in the implementation of sustainable development policies? Findings from the Well-Being of Future Generations (Wales) Act, 2015. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 23(4): 432–445. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2020.1858768.

- Nielsen, C., and K. Cappelen. 2014. “Exploring the Mechanisms of Knowledge Transfer in University-Industry Collaborations: A Study of Companies, Students and Researchers.” Higher Education Quarterly 68 (4): 375–393. doi:10.1111/hequ.12035.

- Office for National Statistics. 2021. Labour productivity GVA.” https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/labourproductivity.Accessed: 20th July 2021

- Office for National Statistics. 2022. FTE multipliers and effects, reference year 2017. Accessed May 5, 20iplp. https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/nationalaccounts/supplyandusetables/adhocs/13359ftemultipliersandeffectsreferenceyear2017

- Pickernell, D., G. Packham, B. Thomas, and R. Keast. 2008. “University Challenge? Innovation Policy and SMEs in Welsh Economic Development Policy.” The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation 9 (1): 51–62. doi:10.5367/000000008783563064.

- Pugh, R. 2017. “Universities and Economic Development in Lagging Regions: ‘triple Helix’ Policy in Wales.” Regional Studies 51 (7): 982–993. doi:10.1080/00343404.2016.1171306.

- Redmond, E. 2013. (Unpublished results). KITE Evaluation Report 2008-2011.

- Rodrigues, C., and A. Melo. 2013. “The Triple Helix Model as Inspiration for Local Development Policies: An Experience-Based Perspective.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 37: 1675–1687. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2012.01117.x.

- Saguy, S., and V. Sirotinskaya. 2014. “Challenges in Exploiting Open Innovation's Full Potential in the Food Industry with a Focus on Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs).” Trends in Food Science & Technology 38 (2): 136–148. doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2014.05.006.

- Sanderson Bellamy, A., and Marsden, T. 2020. A Welsh Food System fit for Future Generations. Cardiff: U:WWF Cymru.

- Senedd Wales. 2007. Rural Development Funding in Wales https://senedd.wales/Research%20Documents/Rural%20Development%20Funding%20in%20Wales%20-%20Quick%20guide-24072006-186958/qg06-0002-English.pdf

- Smith, F. 2023. “A New Dawn? The UK’s Emergent Agri-Food Trade Strategy After Brexit.” King's Law Journal 34: 30–49. doi:10.1080/09615768.2023.2188880.

- Stats Wales. 2021. “Gross Value Added in Wales by industry.” Accessed October 3, 2021. https://statswales.gov.wales/Catalogue/Business-Economy-and-Labour-Market/Regional-Accounts/Gross-Value-Added-GDP/gvainwales-by-industry

- Tamasiga, P., T. Miri, H. Onyeaka, and A. Hart. 2022. “Food Waste and Circular Economy: Challenges and Opportunities.” Sustainability 14 (16): 9896–9896. doi:10.3390/su14169896.

- Technology Strategy Board. 2013. “Knowledge Transfer Partnerships: Achievements and Outcomes p11-12.” Accessed March 22, 2023. https://static.ktponline.org.uk/assets/2012/pdf/KTP-AR-201112.pdf

- UK Government. 2014. Homes and Communities Agency: Additionality Guide Fourth Edition. Accessed March 31, 2022. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/378177/additionality_guide_2014_full.pdf

- UK Government. 2021. “Knowledge Transfer Partnerships: what they are and how to apply.” Accessed June 17, 2021. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/knowledge-transfer-partnerships-what-they-are-and-how-to-apply

- Weidenfeld, A., T. Makkonen, and N. Clifton. 2021. “From Interregional Knowledge Networks to Systems.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 171: 120904. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120904.

- Welsh Economy Research Unit. 2017. "EU Transition and Economic Prospects for Large and Medium Sized Firms in Wales." Available at https://www.gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2019-06/eu-transition-and-economic-prospects-for-large-and-medium-sized-firms-in-wales.pdf

- Welsh European Funding Office. 2016. An Evaluation of the Processing and Marketing Grant Scheme SQW." Accessed April 10, 2019. https://gov.wales/docs/wefo/publications/170216-pmgseval finalreport.PDF/

- Welsh Government. 2009. One Planet, One Wales: The Sustainable Development Scheme of the Welsh Assembly Government.” https://senedd.wales/Laid%20Documents/GEN-LD7521%20-%20One%20Wales%20One%20Planet%20-%20The%20Sustainable%20Development%20Scheme%20of%20the%20Welsh%20Assembly%20Government-22052009-130462/gen-ld7521-e-English.pdf

- Welsh Government. 2010. “Food for Wales, Food from Wales 2010-2020.” https://business.senedd.wales/Data/Plenary%20%20Third%20Assembly/20100706/Agenda/A%20Food%20strategy%20for%20Wales%20%20Food%20for%20Wales,%20Food%20from%20Wales.pdf Accessed 25th July 2020

- Welsh Government. 2014. “Towards Sustainable Growth: Action plan for the Food and Drink Industry.” Accessed 30th December 2022. https://www.farminguk.com/content/knowledge/Towards-Sustainable-Growth-Action-Plan-for-Welsh-Food-and-Drink-Industry-2014-2020(2869-8134-7981-7076).pdf

- Welsh Government. 2020. “Economic Appraisal 2020 Data.” Accessed March 30, 2020: https://businesswales.gov.wales/foodanddrink/welsh-food-drink-performance/economic-appraisal-welsh-food-and-drink-sector

- Wynn, M., and P. Jones. 2017. “Knowledge Transfer Partnerships and the Entrepreneurial University.” Industry and Higher Education 31: 267–278. doi:10.1177/0950422217705442.

- Yin, R. K. 2009. Case Study Research (pp. 18-21). Fourth Edition, Sage Publications Inc., London. https://books.google.co.uk/books/about/Case_Study_Research.html?id=FzawIAdilHkC&redir_esc=y

- Zahra, S., and G. George. 2002. “Absorptive Capacity: A Review, Reconceptualization, and Extension.” The Academy of Management Review 27 (2): 185–203. doi:10.2307/4134351.

- Zeigermann, U. 2018. “Governing Sustainable Development Through ‘Policy Coherence’? The Production and Circulation of Knowledge in the EU and the OECD.” European Journal of Sustainable Development 7 (1): 133–133. doi:10.14207/ejsd.2018.v7n1p133.

- ZERO2FIVE. 2015. (Unpublished Results). Food Innovation Rapid Response Programme. Final Report for Welsh Government.