ABSTRACT

In many European countries, regional planning is an established institutional framework. In recent years we have observed a resurgent research interest in regional planning with a specific focus on governance and institutional design and on the strategic and practical relevance of regional planning in pursuing sustainable development. However, in Sweden, regional planning traditionally has a weak position in practice as well as in research. Yet over the past 15 years, we have seen an increasing political interest in experimenting with different forms and formats of regional planning. In this paper, we explore the emerging logics of non-statutory regional planning, which the majority of Swedish regions have chosen. Drawing upon a qualitative research design we identify, compare and discuss three different logics and their inherent rationales, practices, challenges and prospects. Our analysis shows that our three case regions can do very little non-statutory regional planning unless they are part of properly working multi-level networks, and have well-established regional informal arenas for interaction and political backing. More specifically, we point at a number of tensions caused by the large degree of freedom to design non-statutory regional planning, which foster conflicts, confusion and insecurity.

1. Introduction

Regions are increasingly considered as key sub-national arenas to address challenges for sustainable development as articulated by organizations such as the UN, the OECD and the EU. The main proposition is that regions offer an appropriate scale for dealing with complex and comprehensive spatial planning challenges to sustainable transformation, due to their relations to other policy levels upwards, but also downwards. In addition, it is suggested that the regional policy level offers favourable conditions for policy integration, and thus the coordination of different sectors, actors, agendas and strategies. These arguments have been well echoed in the academic debate in recent years (Haughton and Counsell Citation2004; Rodríguez-Pose Citation2008; Wheeler Citation2009). Consequently, in many European countries, regional planning is acknowledged as a key governance tool to achieve horizontal and vertical coordination and integration of those issue- or sectoral-based conflicts that have tremendous spatial implications (Alden Citation2006; Smas and Schmitt Citation2021).

In Sweden, in the last 20 years or so, a number of public inquires and reform suggestions have questioned the role and function of regions within the political administrative system (e.g. SOU Citation2007). Within this debate, regional planning has been suggested as an important governance tool for housing provision and sustainable development (SOU Citation2015). Yet the institutional arrangements and conditions for regional planning differ between the 21 Swedish regions, since only three regions practice statutory regional planning today (Stockholm, Skåne and Halland), whereas the remaining 18 regions pursue different forms and formats of non-statutory regional planning. However, even though one can argue that within statutory regional planning in Sweden the legal regulations are rather few compared to other European countries, such as Germany, Italy, France or Poland (Schmitt Citation2023), the non-statutory mode offers regions an even larger degree of liberty in defining their logic of practising regional planning. By this we mean the way how regional representatives and related actors interpret the self-given mandate concerning tasks, modes of working, challenges and prospects when practising non-statutory regional planning.

In this paper, we seek to reveal the emerging logics of non-statutory regional planning by analysing three case regions in Sweden – Blekinge region, Östergötland region and Västra Götaland region. Drawing upon a qualitative research design, we identify, discuss and compare three distinctive logics, a negotiation logic, a supporting logic and a distant logic. We argue that all of these three different logics imply a rather non-tangible form of practising regional planning. The low visibility of regional planning in these three regions can be mainly explained by a number of specific limitations and political circumstances as well as by a sensitive relation to municipal planning and to statutory regional development work, which is mandatory for all Swedish regions. These identified logics indicate the diverse ways regions can exercise spatial planning as the governance of place outside the statutory sphere (Schmitt and Wiechmann Citation2018). However, we also point at a number of tensions caused by the large degree of freedom to design non-statutory regional planning, since it also leads to fuzziness and unclarity, fostering conflict, confusion and insecurity.

In the remainder of the paper, we first revisit the recent literature discussing regional planning, with a focus on the European debate, in order to conceptualize the main differences between statutory and non-statutory regional planning. After that we explain the specific context in which non-statutory regional planning has emerged in Sweden and distil the main analytical elements for our empirical study. Next, we inform about our methodological approach. In the section after that we explore the logics of non-statutory regional planning in our three case regions. The paper is finalized with a comparative discussion of three identified logics followed by some conclusions.

2. Conceptualizing (non-statutory) regional planning

When considering recent academic debates about regional planning, it is difficult to capture a generic picture of its added values and functioning. Some qualify regional planning as rather ‘defunct’ due to its inability to respond to contemporary regional problems (Harrison, Galland, and Tewdwr-Jones Citation2021), others argue that the institutional landscape is still ‘intact’ with increasing sets of statutory planning instruments and formal organizational adjustments in recent years (Smas and Schmitt Citation2021). However, what these and other contributions usually have in common is that they consider regions as key sub-national arenas to address topical and explicit spatially relevant challenges (Alden Citation2006; Friedmann Citation1963; Friedmann and Weaver Citation1979; Neuman and Zonneveld Citation2018). Regions may offer a ‘good spatial fit’ to incorporate a number of socio-economic, environmental and functional issues, since they comprise urban, sub-urban and rural areas and their specific challenges and interrelations (Rodríguez-Pose Citation2008). Also, proponents of regional planning underscore that the region is an appropriate scale to pursue horizontal and vertical coordination and integration of those issue- or sectoral-based interests that have tremendous spatial implications, such as the management of land for housing, transport, industry and agriculture versus protection of biological diversity, cultural heritage and climate change adaptation measures (Hilding-Rydevik, Håkansson, and Isaksson Citation2011; Peskett, Metzger, and Blackstock Citation2023; Yan and Growe Citation2022). Regional planning is supposed to mediate when demands for resources and development pressures come into conflict with concerns over social and environmental issues by providing a future-oriented, long-term framework that recognizes interlinkages between and across functional territories (Frank and Marsden Citation2016; Wheeler Citation2009). Unsurprisingly, there has been a resurgent research interest in regional planning in recent years with a specific focus on governance, and institutional design and its strategic and practical relevance (Galland Citation2012; Harrison, Galland, and Tewdwr-Jones Citation2021; Lingua and Balz Citation2020; Neuman and Zonneveld Citation2018; Purkarthofer, Humer, and Mattila Citation2021).

In a European perspective, regional planning is institutionalized differently across countries and its role varies concerning how regional planning is able to actually mediate different interests in the use of land, coordinate aspirations for (economic) spatial development, safeguard environmental quality and the provision of welfare services, to name just a few of its associated tasks (Nadin et al. Citation2018). In recent years, specific attention has been given to the extent to which the formal institutional landscape has changed (Smas and Schmitt Citation2021), but also how regional planning is practised following a flexible network-based governance logic (e.g. Granqvist, Humer, and Mäntysalo Citation2021; Oliveira and Hersperger Citation2019; van Straalen and Witte Citation2018). What is striking from our reading is that Swedish regional planning is often absent or ignored in these debates and thus difficult to position in this growing body of literature, since, from a European perspective, the focus is often on countries such as the UK, Germany or the Netherlands, and from a Nordic perspective, Denmark or Finland.

Another key issue in the debate on regional planning is the question of to what extent the boundaries of regions coincide with the intended planning interventions or in other words, how relational and dynamic perspectives on regions can be reconciled with the existing political jurisdictions and the territorial logics of the related layers of government (Jones and Paasi Citation2013). As Smas and Schmitt (Citation2021, 780) observe, the ‘evolving loss of territorial synchrony […] stimulated debates around soft and hard spaces, and about the extent to which practices in spatial (or regional) planning are able to navigate between those governmental institutions that are supposed to guarantee democratic legitimacy and accountability and those that allow for more flexible approaches in order to bind together different territories, multiple actors and different levels of spatial governance’. This relational perspective is also caused by a rather growth-oriented policy rationale (Mattiuzzi and Chapple Citation2023; Olesen Citation2012), often induced by devolution and re-scaling processes (Galland Citation2012; Roodbol-Mekkes and Anden Brink Citation2015) and orchestrated through network governance, including a wide range of stakeholders representing different sectoral interests (Schmitt and Wiechmann Citation2018). As a side-effect, new functional, strategic and institutional rationales emerge that may result in identifying alternative regional spatial constellations or re-discovering certain regions for regional planning (Grundel Citation2021). As a consequence, as Purkarthofer and Granqvist (Citation2021, 312) put it, ‘[…] spatial planning is today partly taking place in non-statutory or informal planning spaces and processes, which operate alongside the spaces and processes of the statutory system of planning’.

Statutory planning is literally planning under the law, often also characterized as hard-planning. In a European perspective, despite some distinct variations between countries, legislative frameworks usually stipulate a catalogue of tasks, aims and the scope of planning by referring to the prevailing administrative structures and hierarchical orderings, and by defining a number of planning instruments and concepts as well as formal procedures and processes, for instance regarding civic participation. Statutory planning is often criticized for its inadequacy in following economic, political, cultural and social change, and its legal rigidity and bureaucratic procedures (Harrison, Galland, and Tewdwr-Jones Citation2021). In contrast, non-statutory planning approaches offer a more flexible approach to focus on specific strategic key areas, topics and projects, to identify and gather key actors and allow their (multi-level) voluntary involvement by often forming informal partnerships and alliances, which also offer exit options for them. However, non-statutory planning, in recent years also often termed ‘soft planning’, is criticized for its limited effectiveness, questionable non-tangible outcomes, and unclear legitimacy. Also, the coexistence of statutory and non-statutory elements implies great complexity to our planning systems, which may overstrain planning professionals in their daily work (e.g. Granqvist, Humer, and Mäntysalo Citation2021; Mattila and Heinilä Citation2022; Mäntysalo et al. Citation2015).

Non-statutory planning is often characterized as being more agile, since it is supposed to engage more promptly with a number of key characteristics stemming from the strategic spatial planning discourse (e.g. Albrechts Citation2006; Albrechts and Balducci Citation2013). However, one needs to underline that some strategic planning elements have been widely incorporated in statutory regional planning instruments (Smas and Schmitt Citation2021). Across Europe we can identify a wide spectrum of different strategic regional planning approaches, which vary in regard to their substantial tasks, but also concerning the concrete institutional designs in which statutory and non-statutory planning is supposed to unfold (Oliveira and Hersperger Citation2019; Ziafati Bafarasat Citation2015) and to co-exist (Mäntysalo et al. Citation2015). Non-statutory planning practices can also be legally institutionalized after a while and thus gain statutory validity, as the examples of Skåne (Scania) and Halland in southern Sweden show (see below). Other examples are the recent re-introduction of statutory regional spatial planning strategies in England (Ziafati Bafarasat, Oliveira, and Robinson Citation2023) and the gradual formalization of informal city-regional planning in Finland (Mattila and Heinilä Citation2022). However, the distinction between statutory and non-statutory (regional) planning has to be considered with caution (Granqvist, Humer, and Mäntysalo Citation2021), since, as we will discuss in the next section, the related specific opportunities and limitations as well as the scope of coexistence of these two modes of planning are dependent on the prevailing national institutional and legal context and thus require empirical informed investigations.

3. Contextualizing the conditions for non-statutory regional planning in Sweden

The Swedish planning system is in general characterized by a strong municipal autonomy, which means the role of the national state is limited to providing legal frameworks and some policy programmes (e.g. to promote sustainable urban development), and to safeguarding national interests (e.g. in regards to nature protection, defence, critical infrastructure), but otherwise the national state is not allowed to interfere in municipal planning affairs. As a result, also statutory regional planning has a rather weak position according to the Planning and Building Act compared to many other European countries (Smas and Schmitt Citation2022), which corresponds to the overall limited role of the regional policy level in Swedish politics (Blom, Johansson, and Persson Citation2022). In addition, statutory regional planning is legally validated only in three out of 21 regions across the country, namely in Stockholm, Skåne and Halland.

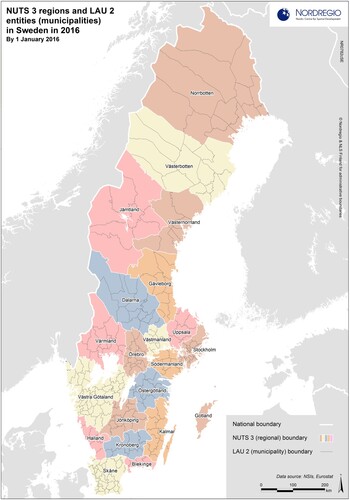

As in many other countries, the national state had a strong interest after World War II in creating regional planning associations in order to safeguard national interests at the regional level (Alden Citation2006; Friedmann Citation1963). However, later, in the preparatory work for the Planning and Building Act of 1987, it was argued that the national state-run regional planning approach did not work well, since it was limited to the documentary and inventory work undertaken within physical national planning (Nilsson Citation2018; Strömgren Citation2007). In addition, two territorial reforms reduced the number of municipalities significantly; in 1952, the 2,400 municipalities were merged into 800 and then in 1974 finally into 284. In terms of land area, by European standards, these comparatively very large municipalities (see ) reduced the need for inter-municipal coordination. Today, Sweden has 290 municipalities, many of which are larger concerning their land area than planning regions in many European countries. Hence, municipal planning inevitably often takes into consideration issues which are of regional scope, such as urban-rural interactions, technical and social infrastructure provision, and ecosystem services (Schmitt Citation2023).

The only Swedish region having a long tradition in statutory regional planning that is conceptualized and practised by regional legitimated institutions, is Stockholm, with a first regional plan adopted in 1958 (an earlier non-statutory forerunner was produced as early as in 1936) and the latest, the eighth one, is from 2018. The Gothenburg region, located on the Swedish west coast (see ), is the second largest city-region in Sweden and has a rather chequered history in this respect. Similar to Stockholm, a first non-statutory regional plan was produced rather early in 1940. Since then, the municipal association, called Gothenburg region, which comprises 13 municipalities, has only worked with non-statutory regional planning. This is noteworthy, since in 1987 this organization became legally a regional planning authority (regionplaneorgan) according to the Planning and Building Act, and was intended to produce statutory regional plans. However, the municipal association continued working only with strategic informal planning documents instead. The legal status to produce a regional plan according to the Planning and Building Act was then taken away in 2018 from this municipal association, with the argument that, due to some legal changes undertaken in the meantime, a democratic legitimized regional institution is required to practice statutory regional planning. As a response to this, the democratic legitimized Västra Götaland region, in which the Gothenburg region is located, attempted to become a formalized regional planning institution. However, the decision was rejected by the municipalities of the region. In this context it is noteworthy that the Västra Götaland region, with the city of Gothenburg as its capital, was formed as late as 1999 by merging three counties (län), as these sub-national institutions were formerly called.

In the meantime, statutory regional planning was introduced in the Skåne region in 2019, in the very south of Sweden and in the Halland region in 2023. The latter is located on the west coast – sandwiched between Skåne and the aforementioned Västra Götaland region (see ). However, similar to the Gothenburg region, the Skåne and Halland regions have practised non-statutory regional planning over many years by using informal strategic planning documents to coordinate transport, green belt and regional development issues, for instance. A number of other regions across the country have undertaken similar non-statutory strategic planning approaches in recent years as we will discuss below. Overall, it should be noted that regional plans, as statutory instruments according to the Planning and Building Act, must specify the basic features for the use of land and water areas and the guidelines for the built environment and structures that are significant for the region. In addition, the regional plan must provide guidance for decisions on municipal comprehensive plans that cover the entire municipal territory as well as detailed plans and area regulations for smaller parts of the municipality. However, it is important to underline that a statutory regional plan, which currently only exists in the Stockholm and Skåne region (Halland is about to produce its first of such plans), is non-legally binding. As such, a regional plan in accordance with the Planning and Building Act offers municipalities and other planning actors (only) indicative strategic guidelines (Schmitt Citation2023).

In recent decades, a number of public inquires and suggestions for reform have questioned the role and function of regions within the political administrative system in Sweden (e.g. SOU Citation2007). In this debate, statutory regional planning has been suggested as an important governance tool for housing provision and sustainable development (SOU Citation2015). This debate has not led to mainstream statutory regional planning in all 21 regions so far. It is up to the regions themselves, as politically legitimized institutions, to apply if they want to become a regional planning authority and thus to practice statutory regional planning (as Skåne and Halland did recently) or to follow the non-statutory mode instead. The approval of such an application is up to the national parliament, since it requires an amendment of the Planning and Building Act.

The fact that statutory regional planning is currently performed in only three regions also mean that the remaining 18 regions can practice non-statutory regional planning differently (Fredriksson et al. Citation2023). These differences can certainly be explained by the varying institutional arrangements and geographic conditions, but also by the political ambitions to engage with regional planning outside the Planning and Building Act. Or to put it differently, the non-statutory regional planning mode allows the remaining 18 regions to experiment and thus to define their own, what we call in the following, ‘logic’ practising regional planning. In our analysis, we are interested in three fundamental analytical elements that shall help us to disclose these logics (see ). For instance, we are interested in how these three regions understand their overarching mandate; what policy areas are targeted and what the relation is to municipal planning. Another analytical element focuses on the understanding of tasks and modes of working, i.e. the scope and character of assignments and what strategies and routines emerge. Finally, we explore the challenges and prospects of practising non-statutory regional planning.

Table 1. Analytical elements for exploring the logics of non-statutory regional planning.

Before turning to our investigation of the logics of non-statutory regional planning in three Swedish regions, we need to shed light on another related task that Swedish regions are concerned with, namely regional development. Regional development is currently governed by a different legal framework than statutory regional planning, namely the act on regional development (from 2010) and the regulations on regional growth work (from 2017). The underpinning rationale of these two legal frameworks is to enable regions ‘to promote sector-wide cooperation between actors at local, regional, national and international level, while economic, social and environmental sustainability must be an integral part of analyses, strategies, programmes, and efforts’ (Schmitt Citation2023). In contrast to statutory regional planning, which is only practised in three out of 21 regions, regional growth work is to be practised in all Swedish regions, and it includes producing and implementing regional development strategies (regionala utvecklingsstrategier). Another mandatory regional instrument for all 21 regions is a transport plan, which has rather an investment instead of a coordinative character as in the case of regional development strategies. The strategies, similar to statutory regional plans and the regional transport plans, are reviewed by the respective county administrative boards. These are national institutions installed in each of the 21 regions across the country to ensure that national goals are met, while taking regional conditions into account. In other words, regional spatial issues are basically dealt with by two institutionally divided frameworks, which also, unsurprisingly, have developed parallel communities of practice (Emmelin and Nilsson Citation2016). However, there are a number of examples where this institutional divide between regional planning, either following a statutory or non-statutory mode, and regional development is bridged in practice (Boverket Citation2017).

4. Methodological notes

To investigate the logics of non-statutory regional planning we applied semi-structured interviews during spring 2023, exploring how planning professionals reflected upon tasks and challenges they face as well as their understanding of the overarching mandate that regional planning should address (see ). Regarding the latter, it was key how our interviewees positioned non-statutory regional planning in relation to the statutory work with regional development and statutory municipal planning. Our interviewees represented three exemplary regions where non-statutory regional planning is practised (see below) as well as the Government Offices of Sweden, which is an integrated public authority comprising the Prime Minister’s Office (here the government ministries and the Office for Administrative Affairs). In addition, we interviewed the public agency Boverket, which is the Swedish National Board of Housing, Building and Planning, and planners from main cities of our three case regions. After the interviews (eight in total) had been transcribed, a thematic analysis was carried out with the help of our analytical elements (see ) in order to construe the underlying logics of practising non-statutory regional planning. Our analysis was complemented by participative observation during the Forum for Sustainable Regional Development in February 2023. This is a biannual event where all non-political director generals of the 21 regions are present and which was arranged by the Ministry of Rural Affairs and Infrastructure and the Government Offices of Sweden together with the Swedish Agency for Economic and Regional Growth (Tillväxtverket). On this occasion, the current state and future of regional planning in Sweden were discussed. In addition, we also consulted the regional development strategies of each of the three regions, since, at least in some cases, these policy documents are also used to express regional planning ambitions. Hence, we used these strategies in particular in order to investigate to what extent the three regions have formulated regional planning objectives and how they position these in relation to their regional development work.

Our selection of the three case regions (see ) was informed by two recent surveys on the current state of regional planning in Sweden (Bergkvist Andersson Citation2023; Fredriksson et al. Citation2023). The key criterion for us has been to identify contrasting cases that represent a wide scope of non-statutory regional planning approaches based on some initial analysis. The Östergötland region intends to develop and expand its spatial planning competence and particularly to influence policies relating to regional development. The Blekinge region is depicted in the two surveys as an example that to a large extent already practices non-statutory regional planning in close relation to its regional development work. The Västra Götaland region was chosen because of its historical background, since, as mentioned earlier, one part of the region, the Gothenburg region, has a long tradition of regional planning. Also, its rather complex geography and the fact that the region was formerly separated in three counties make it an interesting case.

Figure 2. Three Swedish case regions for analysing non-statutory regional planning. Source: Creative Commons (2023, amended by the authors), https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en

5. Exploring the logics of non-statutory regional planning in three Swedish regions

5.1. The negotiation logic – the case of Blekinge region

Blekinge region is located in the southeast of Sweden, bordering the region of Skåne in the south and Kalmar in the north. It covers a relatively small territory and consists of five municipalities (see and ). Population-wise Blekinge region is the third smallest of the 21 regions in Sweden, with almost 160,000 inhabitants at the end of 2022.

According to our analysis, the region practices a negotiation logic in its approach to non-statutory regional planning. This logic is based on the assumption that cooperation and flexibility in the relationship between municipalities and the region is needed to remain competitive, due to the region’s limited demographic size and economic assets. The region identifies spatial planning as one key policy area in which it can create societal and economic added value by increasing its organizational capacity and knowledge related to strategic spatial planning on the one hand, and by proactively working as a networking actor on the other. The region’s representative was adamant in explaining that the traditional hierarchical understanding of the Swedish planning and administrative system, in which regions have a rather weak position, does not apply to Blekinge region. Instead, the region views its position rather from a horizontal perspective by aiming to lessen the impact of municipal borders and by creating opportunities for cooperation with several regional actors as well as stimulating inter-municipal cooperation within the area of spatial planning. This negotiation logic is motivated by the polycentric context of the region, with no obvious major core or city. Since Blekinge region’s geographical area is small compared to other Swedish regions with only five municipalities, cooperation is easier compared with most other regions in Sweden. The adjacent region Skåne with 33 municipalities most likely faces other difficulties in terms of inter-municipal cooperation (Informant, Blekinge region 03-03-2023). In this vein, our respondent considers the region to be a flexible, modern and innovative partner within the institutional spatial planning landscape in Sweden. Yet municipalities are still considered to be the true authorities of spatial planning, but the region searches for a role in which its coordinating and networking capacities can be of use. ‘We have tried to blur the lines between municipalities (…) in order to reduce intra-regional competition’ (informant, Blekinge region, 03-03-2023). The idea of the region as an informal partner is also shared by the representative of Ronneby municipality, who calls the region an ‘invaluable partner (…) with whom we can discuss different things in a freer way compared to the more formal County Administrative Board’ (Informant, Ronneby municipality, 03-20-2023).

Tasks that fall within the Blekinge region’s understanding of non-statutory regional planning include the creation and maintenance of informal networks as noted before, educational actions to raise awareness of the opportunities of a regional planning approach and the development and communicative application of a strategic image (strukturbild). The structural image in Blekinge’s regional development strategy manifests the negotiation logic insofar as it depicts strategic nodes and important cores in a rather abstract way in order to avoid conflicts with municipalities. Instead, the underlying idea is to invite discussions and reflections among municipalities rather than to guide incentives in prioritized areas (Informant, Blekinge region, 03-03-2023).

The negotiation logic of the Blekinge region faces challenges that revolve around the ability to allocate adequate resources to the region’s regional development and regional planning units. Another challenge relates to the controversial terminology for regions practicing regional planning exclusively outside of the statutory planning system. In practice, one of our informants pointed to the fact that a number of different Swedish terms are used elsewhere across the country (such as regional planering, regional utvecklingsplanering or regional strategisk planering) with slightly different connotations in order to avoid the legal term used for statutory regional planning, namely regional fysisk planering in Swedish. The latter would not be accepted by a number of municipalities as they would feel restricted in their planning monopoly. As a consequence, representatives of the Blekinge region have chosen to use their own home-made terms, namely ‘co-planning’ (samplanering) and ‘strategic community planning’ (strategisk samhällsplanering) (Informant, Blekinge region, 03-03-2023).

5.2. The supporting logic – the case of the Östergötland region

The Östergötland region, like Blekinge region, is located in the south-east of Sweden (see and ) and comprises 13 municipalities and slightly over 470,000 inhabitants (end of 2022). The region has two major urban centres, Linköping and Norrköping, with around 165,000 and 145,000 inhabitants respectively.

The region calls its current spatial planning ambitions an explorative process, meaning that the regional planning unit is actively seeking to identify a suitable role that will be accepted by the other actors in the region, in particular the municipalities. According to our analysis the region practices a supportive logic in its approach to non-statutory regional planning, since its main objective is to assist municipalities in their strategic spatial planning work. Our regional informant argues that the region demonstrates a strong variability in its urban and rural composition and place-based resources and thus identifies its role as balancing out the uneven distribution of competitive assets and capabilities (Informant, Östergötland region, 01-03-2023).

The region’s intentions to increase activities in non-statutory spatial planning began in 2016, when a first strategic image was included in the regional development strategy. In 2023, the work with a so-called regional spatial strategy (rumslig strategi) started in order to clarify the region’s spatial planning projects in close cooperation with the municipalities. The reason for this work is that the existing regional development strategy is considered unable to properly communicate the place-based assets of the region and to guide the strategic planning work of the municipalities. Therefore, according to our informants, the region strives for further integrating concepts of regional planning in their statutory regional development work (Informant, Linköping municipality, 28-03-2023).

Challenges that the supportive logic faces in the Östergötland region include the uneven levels of ambition and interest among the municipalities to consider the region as a supportive partner, the varying levels of resources available to municipalities and the risk of overstretching the self-defined mandate for practising non-statutory regional planning with the self-defined tasks centred around supporting the municipalities. The regional spatial strategy is not intended to encroach on the municipal planning monopoly, but rather to clarify the region’s role as a unifying actor, as a knowledge producer of useful material and as a reasonable partner in spatial planning matters for the municipalities (Informant, Östergötland region, 01-03-2023). The region’s approach to spatial planning, while supporting and guiding the spatial planning work of the municipalities, is otherwise primarily intended to create an understanding of the region’s territory and to identify the role the region may enact within the field of spatial planning.

Like the Blekinge region, the logic of the Östergötland region seeks to utilize its less formal role compared to the County Administrative Board. ‘We are a more reasoning actor when it comes to questions of spatial planning, even if the County Administrative Board officially handles them’ (Informant, Östergötland region, 01-03-2023). Another rationale that has been put forward is that municipal borders play a limited role in the daily life of Östergötland’s inhabitants today. The blurring of borders is exemplified by the municipalities Linköping and Norrköping, currently developing their second mutual comprehensive inter-municipal plan to cover their shared territories.

Indeed, the region’s supportive and to some extent explorative logic means that it enjoys relative freedom, but our informant expressed some frustration in regards to the lack of guidance from the national level. Since non-statutory regional spatial planning is contingent on the ambition and interest of multiple partners, the Östergötland region identifies challenges in the uneven levels of interest by other actors. The existing region-wide networks generally fluctuate depending on the willingness to participate of the individual municipal planners (Informant, Östergötland region, 01-03-2023).

5.3. The distant logic – the case of Västra Götaland region

The Västra Götaland region, located in the southwestern part of Sweden (see and ), is in terms of population the second largest Swedish region (after Stockholm region) and had more than 1.75 million inhabitants at the end of 2022. It comprises 49 municipalities and also has Sweden’s second-largest city, Gothenburg, with almost 600,000 inhabitants. The region’s municipalities are organized within four municipal associations (Kommunalförbund), creating an additional sub-regional actor sandwiched between the municipal and the regional level. As mentioned earlier, the Gothenburg region, which covers only a small but comparatively populous part of the Västra Götaland region, has a long but discontinuous history of regional planning.

Our analysis reveals a clearly different approach to non-statutory regional planning compared to the other two case regions, which we qualify as a distant logic. One reason for this logic is the fact that a number of municipalities impede any efforts undertaken by the region. For instance, our informant described some cases in which projects proposed by the region have been rejected by the concerned municipalities. Instead, activities that may fall under the category of non-statutory regional planning are left to the municipal associations. One of them, the Skaraborg municipal association, has for instance identified seven strategies connected to spatial planning in an informal policy document, which is called structural image Skaraborg – the network-city (Strukturbild Skaraborg – nätverksstaden, Skaraborg kommunalförbund Citation2015). Another example is the Gothenburg region, which has worked for many years with producing strategic informal planning documents. The latest of this kind of document is from 2008. Similar to Skaraborg, the document is entitled as a structural image with the overarching goal to coordinate the member municipalities’ land-use planning. In addition, this policy document is supposed to guide the dialogue with national public agencies and the further development of main transport links, for instance (Göteborgsregionens kommunalförbund Citation2008).

Nonetheless, our informants articulated that the Västra Götaland region still recognizes a need for more coordination in relation to a number of spatial planning-related policy fields (such as energy provision), but there is no political will to transfer some coordinating capacities to the regional level. Hence, the region’s approach towards non-statutory regional planning can be described as contingent on resources and political ambitions, which are currently lacking. Our informants pointed at the rather complex institutional composition across the region, with a comparatively high number of municipalities and the four municipal associations. Also, the region’s geography creates a number of challenges, such as its diverse and scattered distribution of urban and rural centres with different economic profiles and sub-regional identities that can be difficult to connect with transport infrastructures due to the numerous islands along the coast line and the different types of landscapes and nature reserves. These challenges, it is argued by our informants, are apparently better tackled by smaller institutional settings, such as the municipal associations offer, than by the Västra Götland region. However, a counter argument from the regional level is that since the municipal associations consist of political representatives from municipalities, regional planning issues are not within the control of democratically legitimized regional politicians. Hence, our interviewee expressed concern about the current limitations on practising non-statutory regional planning. Therefore, they focus their work on what they are formally responsible for, namely regional development and public transport (Informant, Västra Götaland region, 20-03-2023).

5.4. On the interconnection of regional planning and regional development

Despite the differences between the three case regions, the interconnection of regional planning and regional development is a central aspect articulated by all of our informants. For instance, during the Forum for Sustainable Regional Development, the regional representatives agreed that regional planning is an important means of achieving regional development. A number of current issues that have been discussed during the forum, e.g. the Swedish energy crisis, the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic, climate change adaptation and national security are all issues that require a strong regional planning perspective. However, these issues are formally separated into responsibilities to be dealt with by two different bodies of governance, namely municipalities and the county administrative boards. Yet the regional representatives clearly demonstrated during the forum their ambition to increase their involvement with these issues, in particular in matters such as climate change adaptation and energy stability. During this informal forum and in our interviews, it also became clear that both national and regional representatives share an understanding that municipalities are not fully capable of meeting these contemporary challenges mentioned above. Hence, it was suggested that a re-scaling of governance is required, specifically with a view to better connect regional development issues with regional planning. ‘Planning and development are interconnected. But there are so many different interpretations of how to work with this (…) What happens outside of the Planning and Building Act is also an important part of the planning process. But, it’s far from being clear’ (Informant, Boverket, 19-04-2023). However, bridging regional development and regional planning communities is traditionally tricky (Emmelin and Nilsson Citation2016; Hermelin and Persson Citation2021), since these two are not only institutionally divided, due to different legal frameworks, but also mentally. ‘Traditionally (…) either you were educated as a planner or an architect and then worked with planning, or you were educated as a human geographer or in other fields of social science and then worked with development issues’ (Informant, Government Offices, 31-03-2023).

Moreover, our interviewees from our three case regions complained about the traditionally low support of regional planning in general and non-statutory regional planning in particular at the national level. However, this criticism is well known to national planning institutions such as Boverket and the Government Offices. Yet the national level appears to prefer regional planning as adapted to local conditions, especially to unite the practices and results of regional planning and regional development: ‘Different parts of Sweden face different challenges’, one informant of the Government Offices said. ‘(…) Planning is very important if you want to have good regional development’ (Informant, Government Offices, 31-03-2023). However, at the national level, the current versatility and changeability of non-statutory practices in Swedish regions are considered both as an asset and as a weakness in regard to the perceived need for increased regional planning competences.

6. Comparative discussion of three identified logics of non-statutory regional planning

The three cases have revealed that non-statutory regional planning practices can take different forms. The following table synthesizes the main practices and rationales that lead to the three distinct logics of non-statutory regional planning.

Our analysis demonstrated that Blekinge region, which represents the negotiating logic, seeks to provide an informal arena for interaction for the region’s municipalities, the national level and other regional actors. For this, the responsible regional planners produce maps and other material to stimulate discussions. The negotiating logic considers the regional development strategy a suitable policy in which spatial planning can be incorporated. The supportive logic, here exemplified by the Östergötland region, seeks to assist the region’s municipalities in their spatial planning. In doing so, similar to Blekinge region, regional planners offer analytical material and other additional documents in order to clarify the region’s spatial strategy. The supportive logic, like the negotiating logic, strives to fill the institutional void at the regional level of the formal planning system and as such the two logics share a few similarities (see ). The distant logic, here represented by the Västra Götaland region is the result of lacking political support and ambition, a complex institutional setting due to the historic context and a complicated geography that makes it difficult to identify a common denominator for working with spatial planning at the regional scale of the entire region. Instead, at least to some extent, spatial planning is coordinated within smaller spatial units above the municipal level, namely by municipal associations. Also, the distant logic leans strongly on the municipal planning monopoly discourse, which makes it difficult to mobilize resources to move towards rather similar logics as represented by the other two case regions.

Table 2. Three distinct logics of non-statutory regional planning.

Overall, we recognize that all three case regions are examples of a rather experimental approach towards non-statutory regional planning. This also means that the three case regions are still in a process of identifying how best to continue practising regional planning in the near future. This causes a number of challenges. The negotiating logic, which is exemplified by the Blekinge region, faces challenges of resource allocation and use of proper terminology due to tensions in the relationship between municipalities and the region. The supportive logic, exemplified by the Östergötland region, faces challenges by developing its spatial profile in a complementary document to the regional development strategy. Delineating the region’s spatial profile is supposed to be helpful for the municipalities in the first place, but should not contradict or limit their spatial planning ambitions. The Västra Götaland region’s distant logic towards non-statutory regional planning can be construed as regressive compared to former times. As noted above, the region is limited in its ability to practice regional planning due to lacking political interest even though it is considered necessary by regional planning professionals. To direct the non-statutory mandate to municipal associations is considered as a constrained compromise, but is reasonable due to the complex historic and geographical context.

While these practices and the underlying logics differ across the three case regions, some approaches are more or less ubiquitous. One example is the use of so-called structural images (strukturbilder). These are often archetypical maps highlighting functional connections, important nodes and different types of transport flows, for instance. These images are either future-oriented, visionary or have rather an analytical-descriptive character. Using the analytical-descriptive character can be interpreted as a way for regions to avoid conflicts with municipalities, since a visionary and thus normative image inevitably illuminates prioritized areas and neglects other parts of the region (Bergkvist Andersson Citation2023). Otherwise, these structural images have the potential to create a common understanding within the region under consideration on what regional planning is or should be (Fredriksson et al. Citation2023) and partly serve as symbolic images for the non-statutory regional planning approach as such. Another typical non-statutory regional planning practice is the formation, or at least discussion, of a model for cross-sectoral region-wide collaboration. Thereby, as a recent survey has suggested, regions aim to construct networks with different actors, in particular with the municipalities, the County Administrative Board as a national institution operating at the regional level, neighbouring regions as well as other organizations representing sectoral and spatial interests (Fredriksson et al. Citation2023).

Overall, it can be recognized that all of the identified logics of non-statutory regional planning are difficult to trace, since they rather operate in the background (e.g. using educational actions, forming informal networks), instead of proactively promoting regional planning issues, such as the exploitation of land for housing, transport, industry and agriculture versus protection of biological diversity, cultural heritage and climate change adaptation measures. For instance, even the incorporations of maps and/or arguments on spatial prioritizations have been integrated in regional development strategies only after long-lasting battles, as one member of the Forum for Regional Development put it. In addition, due to the non-tangible character of non-statutory regional planning it is difficult to establish a clear terminology within the field of non-statutory regional planning. Hence, a multitude of different terms were used in an arbitrary way and only vaguely defined during the interviews. To some extent, regional planning professionals seem to be afraid of using terms like regional planning for their work, as they do not want to displease municipalities as their representatives would rather feel constricted instead of inspired. In other words, although at least two of the three case regions follow a pronounced logic of practising non-statutory regional planning (here Blekinge and Östergötland region), they cannot advertise this fact. Furthermore, organizational differences between regions, such as the administrative division between professional planners and development strategists and the formation of two different types of communities (Smas and Schmitt Citation2022), make it rather difficult to establish an advanced understanding of the potential added value that non-statutory regional planning may offer. Hence, unsurprisingly, the interviewed regional planning professionals articulated some frustration due to the invisibility of their work and their unclear mandate on how to navigate between statutory regional development work and loosely defined non-statutory regional planning ambitions.

7. Conclusions

From a Swedish point of view, we can discern that the spatial planning perspective at the regional level has gained new interest in recent years (Fredriksson et al. 2023; Smas and Schmitt Citation2021), which is also the case in many other European countries (Purkarthofer, Humer, and Mattila Citation2021; Smas and Schmitt Citation2021). In principle, the 18 Swedish regions that are practising non-statutory regional planning are encouraged to apply to become statutory regional planning authorities. However, the interest among such Swedish regions in following the statutory mode appears to be lower than at the national policy level, with the majority of regions either choosing to develop further their regional development strategies by integrating clearer territorial dimensions or, as at least two of our three case regions have shown by developing in addition other collaborative formats, informal strategic documents or knowledge-based material to address regional planning matters and objectives (Bergkvist Andersson Citation2023). Overall, there is a clear preference for many Swedish regions to continue working with non-statutory regional planning (Fredriksson et al. Citation2023). However, this work is often not very tangible and thus adds to the complex and indistinct nature of Swedish regional planning. This leads to various tensions and challenges, not least regarding non-statutory regional planning, because, as our sample of three regions has shown, regions interpret their mandates, roles, tasks and also challenges in various ways, which conflates into what we refer to here as logics. In contrast to Fredriksson et al. (Citation2023), who described Swedish regions as moving through phases from ‘no planning ambition’ to a ‘finished’ regional planning institution, we do not see any signs of regions converging in a chronological timeline. Rather, we assume we will see the emergence of further logics in the new future concerning how to pursue regional planning in a non-statutory manner. Overall, these logics indicate the diverse ways regions can exercise spatial planning as the governance of place outside the statutory sphere. It also became clear that regions can do very little non-statutory regional planning unless they are part of proper multi-level networks, and have political backing and well-established regional informal arenas for interaction. While the large degree of freedom to design non-statutory regional planning was often mentioned as beneficial in our interviews, it also leads to fuzziness and unclarity, which foster conflict, confusion and insecurity.

The generally low level of interest among Swedish regions in becoming statutory regional planning institutions resonates well with the notion of regions as versatile governance environments (Paasi and Metzger Citation2017). With little support from the national level and two parallel legal frameworks, where one framework stipulates regional development work as mandatory and the other one regional planning as an option if there is a political majority, most Swedish regions have decided to engage and thus experiment rather with non-statutory regional planning. Those regions thus seek to fill an institutional void by carefully sounding the opportunities, but also the limitations, specifically in view of avoiding conflicts with the region’s municipalities. However, as we have shown and discussed, they do this in rather an invisible manner and it takes some effort to reveal what logics are actually emerging. Hence, we see an enormous need for further research to make this invisibility more tangible, not only in a Swedish context, but also beyond. In other words, we want to encourage further research that explores the underlying rationales, pursued practices and strategies (or simply logics) of regional planning in order to better understand what terms like ‘non-statutory’, ‘soft’ or ‘informal (strategic)’ planning really mean.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Albrechts, L. 2006. “Bridge the Gap: From Spatial Planning to Strategic Projects.” European Planning Studies 14 (10): 1487–1500. doi:10.1080/09654310600852464.

- Albrechts, L., and A. Balducci. 2013. “Practicing Strategic Planning: In Search of Critical Features to Explain the Strategic Character of Plans.” disP - The Planning Review 49 (3): 16–27. doi:10.1080/02513625.2013.859001.

- Alden, J. 2006. “Regional Planning: An Idea Whose Time has Come?” International Planning Studies 11 (3–4): 209–223. doi:10.1080/13563470701203801.

- Bergkvist Andersson, H. 2023. Sveriges regioner – lägesbild över regional planering. Näringsdepartementet, Enheten för regional utveckling och landsbygdsutveckling. Unpublished Report.

- Blom, A., J. Johansson, and M. Persson. 2022. Regionboken - Sverige på Regional Nivå. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Boverket. 2017. Regional Fysisk Planering i Utveckling – Fyra Exempel. Karlskrona: Boverket. https://www.boverket.se/globalassets/publikationer/dokument/2017/regional-fysisk-planering-i-utveckling.pdf

- Emmelin, L., and J. Nilsson. 2016. “Fysisk Planering - att Forma ett ämne.” In Femtio år av Svensk Samhällsplanering: Vänbok Till Gösta Blücher, edited by L. Emmelin, J.-E. Nilsson, and F. von Platen, 301–322. Karlskrona: Jan-Evert Nilsson Analys.

- Frank, A., and T. Marsden. 2016. “Regional Spatial Planning, Government and Governance as Recipe for Sustainable Development?” In Metropolitan Ruralities - Research in Rural Sociology and Development, vol. 23, edited by K. Andersson, S. Sjöblom, L. Granberg, P. Ehrström, and T. Marsden, 241–271. Leeds: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. doi:10.1108/S1057-192220160000023011

- Fredriksson, C., S. Hedman, J. Sundelöf, J. Franklin, and K. Kronlid. 2023. Kartläggning Rumslig Regional Planering. Stockholm: WSP. https://www.boverket.se/contentassets/1623fb8b2daf46d5bb7bf100a7ad0baa/kartlaggning-regional-rumslig-planering.pdf

- Friedmann, J. 1963. “Regional Planning as a Field of Study.” Journal of the American Institute of Planners 29 (3): 168–175. doi:10.1080/01944366308978061.

- Friedmann, J., and C. Weaver. 1979. Territory and Function. The Evolution of Regional Planning. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Galland, D. 2012. “Is Regional Planning Dead or Just Coping? The Transformation of a State Sociospatial Project Into Growth-Oriented Strategies.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 30 (3): 536–552. doi:10.1068/c11150.

- Göteborgsregionens kommunalförbund. 2008. Strukturbild för Göteborgsregionen. Göteborg: Göteborgsregionens kommunalförbund. https://goteborgsregionen.se/download/18.5d8a5cd41793ff87c4e725/1620290970608/Strukturbild%20G%C3%B6teborgsregionen.pdf

- Granqvist, K., A. Humer, and R. Mäntysalo. 2021. “Tensions in City-Regional Spatial Planning: The Challenge of Interpreting Layered Institutional Rules.” Regional Studies 55 (5): 844–856. doi:10.1080/00343404.2019.1707791.

- Grundel, I. 2021. “Contemporary Regionalism and The Scandinavian 8 Million City: Spatial Logics in Contemporary Region-Building Processes.” Regional Studies 55 (5): 857–869. doi:10.1080/00343404.2020.1826419.

- Harrison, J., D. Galland, and M. Tewdwr-Jones. 2021. “Regional Planning is Dead: Long Live Planning Regional Futures.” Regional Studies 55 (1): 6–18. doi:10.1080/00343404.2020.1750580.

- Haughton, G., and D. Counsell. 2004. “Regions and Sustainable Development: Regional Planning Matters.” The Geographical Journal 170 (2): 135–145. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3451590.

- Hermelin, B., and B. Persson. 2021. “Regional Governance in Second-Tier City-Regions in Sweden: A Multi-Scalar Approach to Institutional Change.” Regional Studies 55 (8): 1365–1375. doi:10.1080/00343404.2021.1896693.

- Hilding-Rydevik, T., M. Håkansson, and K. Isaksson. 2011. “The Swedish Discourse on Sustainable Regional Development: Consolidating the Post-Political Condition.” International Planning Studies 16 (2): 169–187. doi:10.1080/13563475.2011.561062.

- Jones, M., and A. Paasi. 2013. “Guest Editorial: Regional World(s): Advancing the Geography of Regions.” Regional Studies 47 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1080/00343404.2013.746437.

- Lingua, V., and V. Balz, eds. 2020. Shaping Regional Futures. Designing and Visioning in Governance Rescaling. Cham: Springer.

- Mattila, H., and A. Heinilä. 2022. “Soft Spaces, Soft Planning, Soft Law: Examining the Institutionalisation of City-Regional Planning in Finland.” Land Use Policy 119: 106156. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2022.106156.

- Mattiuzzi, E., and K. Chapple. 2023. “Epistemic Communities in Unlikely Regions: The Role of Multi-Level Governance in Fostering Regionalism.” Journal of Planning Education and Research 43 (3): 682–696. doi:10.1177/0739456X20937287.

- Mäntysalo, R., K. Jarenko, K. Nilsson, and I. Saglie. 2015. “Legitimacy of Informal Strategic Urban Planning—Observations from Finland, Sweden and Norway.” European Planning Studies 23 (2): 349–366. doi:10.1080/09654313.2013.861808.

- Nadin, V., A. Fernández Maldonado, W. Zonneveld, D. Stead, M. Dąbrowski, K. Piskorek, A. Sarkar, et al. 2018. COMPASS: Comparative Analysis of Territorial Governance and Spatial Planning Systems in Europe. Luxembourg: ESPON EGTC. https://www.espon.eu/sites/default/files/attachments/1.%20COMPASS_Final_Report.pdf

- Neuman, M., and W. Zonneveld. 2018. “The Resurgence of Regional Design.” European Planning Studies 26 (7): 1297–1311. doi:10.1080/09654313.2018.1464127.

- Nilsson, K. 2018. “The History of Swedish Planning.” In Nordic Experiences of Sustainable Planning: Policy and Practice, edited by S. Kristjánsdóttir, 127–137. London: Routledge.

- Olesen, K. 2012. “Soft Spaces as Vehicles for Neoliberal Transformations of Strategic Spatial Planning?” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 30 (5): 910–923. doi:10.1068/c11241.

- Oliveira, E., and A. Hersperger. 2019. “Disentangling the Governance Configurations of Strategic Spatial Plan-Making in European Urban Regions.” Planning Practice & Research 34 (1): 47–61. doi:10.1080/02697459.2018.1548218.

- Paasi, A., and J. Metzger. 2017. “Foregrounding the Region.” Regional Studies 51 (1): 19–30. doi:10.1080/00343404.2016.1239818.

- Peskett, L., M. Metzger, and K. Blackstock. 2023. “Regional Scale Integrated Land Use Planning to Meet Multiple Objectives: Good in Theory but Challenging in Practice.” Environmental Science & Policy 147: 292–304. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2023.06.022.

- Purkarthofer, E., and K. Granqvist. 2021. “Soft Spaces as a Traveling Planning Idea: Uncovering the Origin and Development of an Academic Concept on the Rise.” Journal of Planning Literature 36 (3): 312–327. doi:10.1177/0885412221992287.

- Purkarthofer, E., A. Humer, and H. Mattila. 2021. “Subnational and Dynamic Conceptualisations of Planning Culture: The Culture of Regional Planning and Regional Planning Cultures in Finland.” Planning Theory & Practice 22 (2): 244–265. doi:10.1080/14649357.2021.1896772.

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. 2008. “The Rise of the “City-Region” Concept and its Development Policy Implications.” European Planning Studies 16 (8): 1025–1046. doi:10.1080/09654310802315567.

- Roodbol-Mekkes, P., and A. Anden Brink. 2015. “Rescaling Spatial Planning: Spatial Planning Reforms in Denmark, England, and the Netherlands.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 33 (1): 184–198. doi:10.1068/c12134.

- Schmitt, P. 2023. Sweden. An Overview of the Swedish Planning System. https://www.arl-international.com/knowledge/country-profiles/sweden

- Schmitt, P., and T. Wiechmann. 2018. “Unpacking Spatial Planning as the Governance of Place.” disP - The Planning Review 54 (4): 21–33. doi:10.1080/02513625.2018.1562795.

- Skaraborgs kommunalförbund. 2015. Strukturbild Skaraborg – nätverksstaden. Skaraborg: Skaraborgs kommunalförbund. https://skaraborg.se/globalassets/regional-utv/hallbar-samhallsplanering/strukturbild-skaraborg_20151023-rapport-hr.pdf

- Smas, L., and P. Schmitt. 2021. “Positioning Regional Planning Across Europe.” Regional Studies 55 (5): 778–790. doi:10.1080/00343404.2020.1782879.

- Smas, L., and P. Schmitt. 2022. “Region + Planering = Regionplanering - en Komplicerad Ekvation.” In Regioner och Regional Utveckling i en Föränderlig tid, edited by I. Grundel, 42–62. Ödeshög: Ymer.

- SOU – Statens Offentliga Utredningar. 2007. Hållbar Samhällsorganisation med Utvecklingskraft. SOU 2007:10, Stockholm. https://www.regeringen.se/contentassets/7f73e037630a4ef185a4c6d7ede1a323/hallbar-samhallsorganisation-med-utvecklingskraft-sou-200710

- SOU – Statens Offentliga Utredningar. 2015. En ny Regional Planering – ökad Samordning och Bättre Bostadsförsörjning. SOU 2015:59, Stockholm. https://www.regeringen.se/contentassets/885f8c5f74644868a5c3fa88e5047450/sou-201559-en-ny-regional-planering–okad-samordning-och-battre-bostadsforsorjning-del-12

- Strömgren, A. 2007. Samordning, Hyfs och Reda: Stabilitet och Förändring i Svensk Planpolitik 1945 - 2005. Uppsala: Uppsala University.

- van Straalen, F., and P. A. Witte. 2018. “Entangled in Scales: Multilevel Governance Challenges for Regional Planning Strategies.” Regional Studies, Regional Science 5 (1): 157–163. doi:10.1080/21681376.2018.1455533.

- Wheeler, S. 2009. “Regions, Megaregions, and Sustainability.” Regional Studies 43 (6): 863–876. doi:10.1080/00343400701861344.

- Yan, S., and A. Growe. 2022. “Regional Planning, Land-Use Management, and Governance in German Metropolitan Regions—The Case of Rhine–Neckar Metropolitan Region.” Land 11 (11): 2088. doi:10.3390/land11112088.

- Ziafati Bafarasat, A. 2015. “Reflections on the Three Schools of Thought on Strategic Spatial Planning.” Journal of Planning Literature 30 (2): 132–148. doi:10.1177/0885412214562428.

- Ziafati Bafarasat, A., E. Oliveira, and G. Robinson. 2023. “Re-introducing Statutory Regional Spatial Planning Strategies in England: Reflections Through the Lenses of Policy Integration.” Planning Practice & Research 38 (1): 6–25. doi:10.1080/02697459.2022.2061687.