ABSTRACT

Therapists, judges, law enforcement, and students often believe in the existence of automatic and unconscious repression. Such a belief can be perilous as it might lead therapists to suggestively search for repressed memories leading to false memories. Recovering therapy-induced false memories of criminal acts can have serious consequences. Here, we tested whether erroneous beliefs in repressed memories can be corrected. Surveying two cohorts of Forensic and Legal Psychology Master’s students, we examined whether education about the science of (eyewitness) memory can correct erroneous beliefs in repressed memories. Students assessed memory statements before taking a course on eyewitness memory, six weeks after the course exam, and 18 or 6 months later, respectively (Ns = 33-74 per cohort and measurement). As expected, students in both cohorts on average initially strongly agreed with the statement that memories of traumatic events can be unconsciously blocked, but strongly disagreed with the statement after the course. Belief-corrections also persisted after the longer delay. These findings show that educating people about the science of (eyewitness) memory can be effective in correcting false and controversial memory beliefs in general and the existence of repressed memories in specific.

Having knowledge about the functioning of memory is important in many different settings. Police officers interviewing witnesses would benefit from knowing that memory is reconstructive and suggestive interviewing tactics can hurt memory. Therapists treating clients would profit from knowing that there is no convincing proof for the existence of unconscious repressed memories of sexual abuse. People seem to share experts’ views about some aspects of memory. For example, most laypeople agree that memory does not work like a video camera (e.g., Brewin et al., Citation2019; Houben et al., Citation2019; but see Simons & Chabris, Citation2011). However, there is also consistent evidence that people continue to believe in the existence of unconscious repressed memories (Dodier et al., Citationin press; Otgaar et al., Citation2019, in press). In the current field study, we examined whether this belief in repressed memory can be corrected by educating two cohorts of university students about the science of memory).

Repressed memory: a controversy

Repressed memories originate in the early writings of Sigmund Freud who was inspired by physician-hypnotists such as Jean-Martin Charcot (Ellenberger, Citation1970). Furthermore, the focus on repressed memories being unconscious was likely introduced by Anna Freud, Sigmund Freud’s daughter (Erdeyly, Citation2006). The underlying idea is that because of the overwhelming nature of traumatic experiences (such as sexual abuse), people use defense mechanisms as a way to cope with trauma. One of these purported defense mechanisms is repression, where a traumatic experience is blocked out of consciousness automatically and unconsciously. The consequence of repression is that people can no longer retrieve or access the traumatic experience. According to the logic of repressed memories, the blocked trauma is unconsciously stored in pristine form and therefore continues to exert a mental and physical toll, indicated by somatic and psychological symptomatology (e.g., fainting, amnesia). This idea has also been referred to as the body-keeps-the-score hypothesis that holds that trauma is mostly processed on an implicit level (van der Kolk & Fisler, Citation1995). The primary aim of therapy is then to make the implicit explicit by using various interventions (Yapko, Citation1994a, Citation1994b). In short, the concept of repressed memories involves the following: (1) People unconsciously block or repress traumatic incidents and cannot access them anymore; (2) yet, the repressed memory has adverse psychopathological consequences; and (3) recovering the implicit repressed memory is needed to reduce symptomatology.

In the 1990s, the belief in repressed memories was endemic among therapeutic communities. Therapists treating patients who did not remember having a traumatic experience would sometimes suggest that patients did in fact experience trauma, but that these experiences were unconsciously repressed. For example, when patients displayed symptoms of anxiety, mood, or personality disorders, these would be interpreted as indicators of the somatic and physical damage that occurred because of a repressed memory. To recover these unconscious memories, therapists used interventions such as dream interpretation, hypnosis, guided imagery, and diary methods. Consequently, patients started to recover memories of trauma that sometimes led to legal actions such as filing criminal lawsuits against an alleged perpetrator (Loftus, Citation1994; Loftus & Ketcham, Citation1996).

Some of the used therapeutic interventions were highly suggestive, implying that trauma should have been experienced. Meanwhile, psychological experimentation showed that suggestive pressure facilitates the formation of false memories or “memories” of non-experienced events (Loftus, Citation2005). For example, in one of the first demonstrations, Loftus and Pickrell (Citation1995) falsely suggested to student participants that as a child, they had once been lost in a shopping mall. After three suggestive interviews, a quarter of participants (n = 6) reported remembering the fictitious shopping mall incident. Following this study, many other experiments demonstrated the ease by which false autobiographical events can be implanted in memory (e.g., Scoboria et al., Citation2017).

Based on such false memory implantation studies, experimental psychologists posited that memories that were recovered for the first time during treatment might be false memories (Lindsay & Read, Citation1995; Loftus & Davis, Citation2006). The resulting controversy on the existence of repressed memories has been labelled the Memory Wars and although the 1990s are seen as the zenith of this debate, it is clear that the debate is far from settled (Otgaar et al., Citation2019; Patihis et al., Citation2014). Nonetheless, scholars seem to agree that although recovered memories of abuse can be false, it is also possible that they refer to truly experienced events. This latter possibility arises when the event in question has been reinterpreted as a traumatic event, which can add to the feeling that memories of trauma are “recovered” (McNally & Geraerts, Citation2009). The possibility of reinterpreting experiences is vital because it has contributed to reaching some consensus on the topic of repressed memories (e.g., Ost, Citation2003).

The concept of repressed memories is difficult to align with our knowledge on how trauma affects memory. Indeed, an abundance of research has revealed that especially central aspects of traumatic events are well remembered (McNally, Citation2005). For example, surveys with survivors of concentration camps about their traumatic experiences showed that their memories were not lost, but were well remembered over time (e.g., Merckelbach et al., Citation2003; Wagenaar & Groeneweg, Citation1990). In fact, survivors of traumatic events struggle with thinking of and remembering such traumatic experiences too often, rather than being unaware of its occurrence (McNally, Citation2003). Overall, scientific evidence suggests that it is unlikely that unconscious repressed memories exist (McNally, Citation2005). Yet, laypeople and professionals working in different disciplines continue to be convinced of their existence, illustrating that the belief in repressed memory is widespread and by no means limited to a specific population.

Believing in repressed memory

Studies focusing on whether people believe in the existence of repressed memories have predominantly surveyed different groups of people on various memory-related statements including statements on the existence of repressed memories. One of the first surveys was conducted in the US (Yapko, Citation1994a, Citation1994b). More than half (59%, n = 513) of surveyed clinicians agreed that events that we know occurred but can’t remember are repressed memories. In the Netherlands, 96% (n = 25) of surveyed licensed psychotherapists believed in the existence of repressed memories (Merckelbach & Wessel, Citation1998). These studies were performed in the heyday of the Memory Wars. More recent investigations, however, have shown a similar pattern of results (Ost et al., Citation2013; Ost et al., Citation2017; Patihis et al., Citation2014). Similar patterns emerged for other professional groups, including US law enforcement and judges (Benton et al., Citation2006), Dutch police interviewers (Odinot et al., Citation2015) and undergraduate student samples (Patihis et al., Citation2014). A recent review of all published surveys reported that, on average, 58% (n = 4,745) of participants believed in the existence of repressed memories (Otgaar et al., Citation2019).

Some authors have argued that these substantial endorsements of repressed memories might merely reflect a belief in the suppression of memories, which refers to a conscious attempt to block memories rather than the controversial unconscious repression (Brewin et al., Citation2019). We argue that this view is flawed for the following reasons. First, when asked specifically about their belief in unconscious repression, participants’ agreement rates are still high, ranging from 59 to 90% (e.g., Houben et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, in a recent study, participants answered two follow-up items to indicate what they actually meant when they endorsed the view that Traumatic memories are often repressed (Otgaar et al., Citation2020). A majority indicated that such memories were inaccessible (74% of n = 909) and unconscious (81% of n = 909). This pattern of results is in line with the controversial concept of unconscious repression (see also Dodier et al., Citationin press; Otgaar et al., Citationin press).

Second, although simple stimuli such as words can temporarily become less accessible due to memory suppression (Anderson & Green, Citation2001; but see Wessel et al., Citation2020), there is no empirical evidence that autobiographical memories can consciously be suppressed. In fact, certain memory phenomena such as false memories for words are only weakly related or unrelated to false memories for more autobiographical experiences. This suggests that memory for words is somewhat different from memory for autobiographical experiences (e.g., Ost et al., Citation2013; Otgaar & Candel, Citation2011). Finally, the majority of memory scholars are skeptical about the existence of repressed memories (Benton et al., Citation2006; Patihis et al., Citation2018).

The current study

The controversial belief in repressed memories seems to be endemic across various populations (e.g., psychologists, students, judges, police interviewers). This is problematic, because believing in the existence of repressed memories can motivate therapists to engage in suggestive techniques in a well-meant attempt to recover such memories in their patients (cf. Dodier et al., Citation2019; Patihis & Pendergrast, Citation2019). Recovering memories of criminal acts that never occurred has serious real life consequences for the accused and their family members. Negative outcomes include loss of employment, financial burden, mental health issues, disruption of social family life, criminal investigation court proceedings, and imprisonment (Burnett et al., Citation2017; Rumney & McCartan, Citation2017). It is therefore a concern of societal consequence whether such erroneous beliefs can be corrected.

The current study tested whether people can be swayed into believing that repressed memories are actually highly controversial. In the medical field, work on debunking false beliefs, for example on the link between vaccination and autism, demonstrated that providing an alternative account and emphasising scientific facts can be effective (Lewandowsky et al., Citation2012). Hence, educating people about the science of memory and stressing the existing scientific evidence might be one possible pathway to correct the belief in repressed memories. To test this idea, we surveyed two cohorts of postgraduate psychology students – potential future therapists – prior to taking a course on eyewitness memory. Two follow-ups took place six weeks after the exam and with a longer delay of six (cohort 2019) and 18 months (cohort 2018), respectively. We expected that many students would endorse the view that repressed memories existed before the course started but that after the course, a substantial amount of students would have strong reservations towards this belief. The third measurement allowed us to test whether such corrections would persist. Belief updating depends on the perceived relevance of the information and people tend to assign more weight to information that is consistent with previously held views (e.g., Kube & Rozenkrantz, Citation2020). It was therefore possible that students’ initial beliefs would persist.

Method

Participants

The samples consisted of the cohorts of 2018 and 2019 of students enrolled in the Forensic Psychology and Legal Psychology Master’s programmes at Maastricht University. The number of respondents varied between 74 and 33 across the two cohorts and three measurements. shows the sample size per cohort and measurement, and the gender and age distribution. The research line was approved by the standing ethics committee of the faculty. Data and materials are available online: https://doi.org/10.34894/DYNSCY.

Table 1. Sample size, gender and age distribution across two cohorts and three measurements.

Design

In each of the two cohorts, students assessed memory statements three times. Time 2 took place 13 weeks after time 1. Time 3 took place 18 months (cohort 2018) or six months (cohort 2019), respectively, after time 2. Our dependent measure was the endorsement of various memory beliefs. We expected to see a correction in controversial memory beliefs following enrolment in a postgraduate course on eyewitness memory (time 2) worth four ECTS (i.e., 104 h of study and self-study). At time 3, we tested whether such corrections would persist.

Materials

Memory Statements. Participants assessed nine or ten memory-related statements at three different times on a four-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). We were most interested in the statement The mind is capable of unconsciously “blocking out” memories of traumatic events. Other statements concerned the belief that memory functions like a video camera, the development and detection of false memories, permanence of memory, and the association between trauma and memory. Statements at times 1 and 2 were identical.Footnote1 The items were presented in a predetermined order, mixed across the different concepts they tested. describes the exact order. At time 3, we added variations of the statements to test for understanding rather than memorisation of the desired answer. For example, we added the statements Traumatic memories are often unconsciously repressed as a variation of the statement The mind is capable of unconsciously “blocking out” memories of traumatic events and Dissociative amnesia is an essential human response to traumatic events (e.g., combat, natural disasters, and childhood abuse) as a variation of A poor memory for childhood events is indicative of a traumatic childhood. We used the term dissociative amnesia because it has been argued to be similar to unconscious repressed memory (Otgaar et al., Citation2019). To keep the questionnaire brief, we dropped four statements at time 3. We did preserve the original wording of the original repressed memory items and some of the other memory statements. At time 3, the order of the items was different from time 1 and 2 but identical for all participants (see our materials at https://doi.org/10.34894/DYNSCY for details). provides an overview of the statements participants assessed at each measurement.

Table 2. Mean ratings and standard deviations of memory statements assessed by forensic and legal psychology students at three different measurements.

Course on Eyewitness Memory. Students followed an 8-week course on the psychology of eyewitness testimony as part of a Master in Legal Psychology or Forensic Psychology.Footnote2 In this course, students attend a lecture of roughly 90–120 min and one 3-hour tutorial-session with about 12–14 students every week. The covered topics include eyewitness memory, interviewing eyewitnesses, face recognition and facial composites, eyewitness identification, false memories, repressed memories, and trauma and memory. The exam takes place in week 8.

Procedure

The first measurement occurred during the opening lecture of a course on eyewitness memory that is part of the curriculum of the Master’s programmes in Legal and Forensic Psychology. This course is one of two that kicks off these master programmes at the beginning of the academic year. At time 1, students attending the opening lecture participated in an experiment unrelated to the current research (Sauerland et al., Citation2020). The final page of a booklet with materials that participants had received contained the memory statements. Six weeks after the course exam and 13 weeks after measurement 1, we administered the survey again, in the context of another lecture and prior to an information session about our other study (Sauerland et al., Citation2020). The questionnaire was distributed by a different lecturer than the authors and introduced with the prompt that we had asked them to answer these questions again in preparation of the presentation they would receive later on during this lecture.

To test for a long-term effect, we invited participants for a third measurement via email about 18 months (cohort 2018) or 6 months (cohort 2019) after time 2, respectively. The invitation text acknowledged that students had taken the course on eyewitness memory in our Master’s programme and that we were interested in students’ opinion on memory, now that some time had passed. Students received one invitation via email and two reminders within four weeks. At time 3, students responded online via Qualtrics.

Results

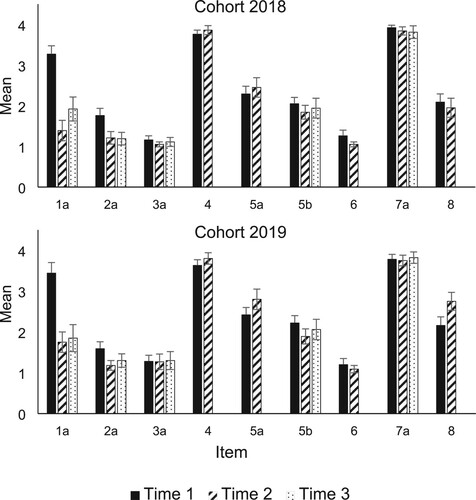

displays the mean ratings and standard deviations across the three measurements. displays the mean survey statement ratings for both cohorts. Due to skewness and kurtosis in the distribution of the responses for most items, we report non-parametric tests when applicable. Participants in all three cohort 2018 measurements came from the same pool of master’s students. Overlap in participants across the three measurements therefore is substantial. However, data were not paired in the strict sense of the term that indicates linking several measurements to one particular participant. Data were paired in the cohort 2019. Therefore, different approaches to analyses were necessary. For cohort 2018, we computed independent samples Welch’s t tests or Kruskal Wallis tests. For cohort 2019, we computed paired samples t tests or Friedman Two-Way Analysis of Variance by Ranks.

Figure 1. Mean survey statement ratings at three different measurements for cohort 2018 (upper panel) and cohort 2019 (lower panel). Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Items: 1a = The mind is capable of unconsciously “blocking out” memories of traumatic events; 2a = A poor memory for childhood events is indicative of a traumatic childhood; 3a = Memory is like a video-camera, accurately recording events as they actually occurred; 4 = It is possible for an individual to develop false memories of non-traumatic events; 5a = Very vivid memories are more likely to be accurate than vague memories; 5b = It is possible for an individual to distinguish between true and false memories; 6 = Memories from the first year of life are accurately stored and retrievable in adulthood; 7a = Memory is influenced by suggestion; 8 = The more emotion with which a memory is reported, the more likely it is to be accurate.

Views on memory

presents the inferential statistics for the comparisons of agreement rates at each measurement. For some statements, students’ views were in line with experts’ views throughout (Benton et al., Citation2006; Patihis et al., Citation2018; Simons & Chabris, Citation2011). For example, students across all measurements agreed with the statements that It is possible for an individual to develop false memories of non-traumatic events and that Memory is influenced by suggestion. Students also largely agreed with a transfer statement that was added at time 3 (Memory can change over time). Likewise, students generally disagreed with the statement that Memory is like a video camera, accurately recording events as they actually occurred at each measurement. Unexpectedly, there seemed to be less understanding of the content of a transfer statement added at time 3 (If an experience was encoded well, the memory of that experience is preserved like a recording for later retrieval) than of the original statement in both cohorts, Friedman test ps < .001.

Table 3. Inferential statistics for comparisons of agreement rates for two different cohorts at three different measurements

Views on repressed memories

As expected, at time 1, students on average strongly agreed with the controversial idea that The mind is capable of unconsciously “blocking out” memories of traumatic events. After the course, students on average strongly disagreed with the possibility to repress memories. At time 3, the effects of the course were still present in both cohorts, with students on average disagreeing with the possibility to repress memories. Disagreement was, however, significantly stronger at time 2 than time 3 in cohort 2018. This was not the case for cohort 2019. Students also generally disagreed with the transfer statement Traumatic memories are often unconsciously repressed at time 3. The original statement and the transfer statement were positively correlated in cohort 2018, r(34) = .46, p = .005, and cohort 2019, r(31) = .66, p < .001.

The second statement that tested views on repression was A poor memory for childhood events is indicative of a traumatic childhood. At time 1, students already generally disagreed with the statement. At time 3, students also on average disagreed with the transfer statement Dissociative amnesia is an essential human response to traumatic events (e.g., combat, natural disasters, and childhood abuse). The ratings for the two statements were only weakly and negatively correlated and did not reach statistical significance in cohort 2018, r(34) = -.14, p = .418, and cohort 2019, r(31) = -.04, p = .849.

Discussion

Can controversial beliefs about memory be corrected? In the current study, we examined whether people’s belief in repressed memory could be corrected by presenting them with information concerning the science of memory. Specifically, at the beginning of their postgraduate education, two cohorts of Forensic and Legal Psychology Master’s students mostly agreed with the notion that memories of traumatic events can be unconsciously blocked (cf. Patihis et al., Citation2014). As expected and in line with earlier work (Lewandowsky et al., Citation2012), six weeks after taking a course on eyewitness memory, students’ opinion had largely turned into disagreement. In a follow-up six or 18 months later, this effect was still prevalent. Although there was a rebound effect between measurements 2 and 3 in cohort 2018 (but not 2019), students in either cohort did not return to their baseline belief in repressed memories and on average still disagreed with the notion of repressed memories at measurements 3.

These findings show that educating students about the science of (eyewitness) memory can be effective in correcting false and controversial beliefs about memory in general and the existence of repressed memories in specific. Three aspects of the findings are reassuring: (1) at the follow-ups, students not only expressed disagreement with the idea that memories of traumatic events can be unconsciously blocked, but they also largely disagreed with a transfer statement (Traumatic memories are often unconsciously repressed). This illustrates students’ deeper understanding and their ability to apply their knowledge to related but different statements. (2) The long-term effects of the course on students’ beliefs six and 18 month after the course exam demonstrate that the course was effective beyond the exam, revealing a viable pathway to effectively debunking false beliefs about repressed memories. Indeed, students on average still disagreed with the notion of memory repression, despite a rebound effect in cohort 2018, where the third measurement took place after 18 months. Of note, there was no rebound effect in cohort 2019, six months following the exam. (3) The pattern of results for both cohorts resemble one another, strengthening the legitimacy of any conclusions drawn from this work.

Prior to taking the course on eyewitness memory, students already expressed views that were in line with the experts’ opinions about different aspects of memory (Benton et al., Citation2006; Patihis et al., Citation2018; Simons & Chabris, Citation2011). For example, students were aware of the reconstructive nature of memory, that it does not function like a video camera, its proneness to suggestion, and the existence of false memories. This is not surprising, because many undergraduate courses and studies in psychology cover important theories of and empirical findings on the functioning of memory. Yet, our findings also demonstrate that these studies do not educate students sufficiently about the topic of repressed memory.

The current omission in psychology curricula to educate students about repressed memory has important implications for educational policy: psychology students in general, but certainly those who might become therapists later on in their careers, should be educated about the current state of knowledge about repressed memories and ideally at multiple stages during their psychology studies. Such education can help prevent victimisation of both patients and those wrongfully accused of abuse as a result of recovering repressed memories in therapy (e.g., Dodier et al., Citation2019; Loftus, Citation2005; Loftus & Davis, Citation2006; McNally, Citation2005; Patihis & Pendergrast, Citation2019). To ensure the long-term effectiveness of such interventions, it is important to take into account rebound effects, the phenomenon that people initially adapt to the new information, but later fall back to their initial views (Thorson, Citation2016; Walter & Tukachinsky, Citation2020). This literature and the rebound effect observed in the cohort 2018 underscore a need for additional training of therapists later on and repeatedly in their careers.

The current findings also have implications for the training of those who are involved in the investigation and prosecution of crimes. Like students, police, jurors, and judges also frequently believe in the existence of repressed memories (Benton et al., Citation2006; Odinot et al., Citation2015). Consequently, they are likely to accept previously repressed memories as evidence in investigative interviews and in the courtroom. The ramifications of such erroneous beliefs are manifold (Burnett et al., Citation2017; Rumney & McCartan, Citation2017), the most severe being wrongful conviction. Educating those involved in the investigation and prosecution of crimes about the science of (eyewitness) memory could help prevent such injustices. Importantly, the persuasiveness of such efforts will likely depend on recipients’ motivation and the credibility (Petty & Brinol, Citation2008) of those conveying the message and their ability to address recipients’ reasons for resistance (e.g., Lilienfeld et al., Citation2013).

It is an empirical question how much education is needed to debunk people’ controversial beliefs in repressed memories. We delivered an intense and extensive course on eyewitness memory spanning eight weeks. This might not be feasible for professionals working in the field such as therapists, lawyers, and police officers. Meanwhile, therapists sometimes do receive brief trainings and workshops on the functioning of memory,Footnote3 but it is unclear whether such trainings are sufficiently effective in correcting views on repressed memory.

This work is not without limitations. Not all students participated at each measurement. At times 2 and 3, ns equalled 76% and 49% (cohort 2018) and 88% and 66% (cohort 2019), respectively, of participants at time 1. Attrition at time 2, however, is unrelated to our study. Participant numbers at time 2 simply reflect presence at a lecture. This number was lower at time 2 than 1, partly because of study drop-out, which was higher in cohort 2018 than 2019. This is typical for cohorts that start out relatively large, as was the case in 2018. For time 3, we cannot rule out that selection effects might have led to an over- or underestimation of the rebound effect between time 2 and time 3. Indeed, we do not know why 36% (cohort 2018) and 25% (cohort 2019) of students, who participated at time 2, did not do so at time 3. One plausible explanation for cohort 2018 is that students simply did not check their university email account, for example, because they had graduated about 10 months earlier. Students may also have been less inclined to respond to our survey at time 3 (May and June 2020), because of the COVID-19 pandemic and the associated burden this crisis had on many. Another limitation to this work is that participants might have guessed which responses were expected from them. We think this is most likely true for time 2, but less so for time 1 and 3. At time 1, the memory-related statements were presented at the end of participating in a study related to expert witness work and students most likely saw these statements as being linked to that study. The purpose of the memory-related statements was therefore most likely concealed by the other study. For cohort 2018, time 3 occurred 18 months following time 2. Although possible, it seems unlikely that students still remembered which of the memory statements were subject to controversy. In all likelihood, the exact circumstances of learning about (false) memories had turned from remembering to knowing by that point (Conway & Dewhurst, Citation1995; Rajaram, Citation1993). For cohort 2019, the time 3 measurement occurred six months following time 2, deeming it somewhat more likely that students still remembered some details about the in-class discussions about the topic and the content of the controversy revolving around repressed memories. Yet, the similarity of result patterns observed across both cohorts and between time 2 and 3 allow for some confidence that our findings are not solely based on demand characteristics but students’ actual opinion formation. Finally, we did not ask participants what they meant specifically when endorsing unconscious repression. For example, did such endorsement mean that they believed that memories became inaccessible and were difficult to retrieve or did participants have different views on unconscious repression? Future research could add follow-up questions that allow participants to specify what their understanding of the concept of unconscious repression is (e.g., Dodier et al., Citationin press; Otgaar et al., Citation2020, Citationin press).

To conclude, the current work shows that intense training can correct students’ controversial memory beliefs in the short and long term. This knowledge is relevant for educational and legal policy and has important implications for educating bachelor (psychology) students, clinicians, police, and legal decision makers. Changing those groups’ erroneous beliefs about memory in general and repressed memories in particular has the potential to prevent wrongful accusations and prosecution of innocents.

Acknowledgement

We thank Astrid Bastiaens for her help in collecting the data.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 There was one exception: we dropped The more confidence with which a memory is reported, the more likely it is to be accurate for cohort 2019, because we realised in hindsight that the statement would need clarification to elicit expert consensus. We will therefore not report means or comparisons for this item.

References

- Anderson, M., & Green, C. (2001). Suppressing unwanted memories by executive control. Nature, 410, 366–369. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/35066572

- Benton, T. R., Ross, D. F., Bradshaw, E., Thomas, W. N., & Bradshaw, G. S. (2006). Eyewitness memory is still not common sense: Comparing jurors, judges and law enforcement to eyewitness experts. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 20, 115–129. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1171

- Brewin, C. R., & Andrews, B. (2017). Creating memories for false autobiographical events in childhood: A systematic review. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 31, 2–23. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3220

- Brewin, C. R., Li, H., Ntarantana, V., Unsworth, C., & McNeilis, J. (2019). Is the public understanding of memory prone to widespread “myths”? Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 148, 2245–2257. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000610

- Burnett, R., Hoyle, C., & Speechley, N.-E. (2017). The context and impact of being wrongly accused of abuse in occupations of trust. The Howard Journal, 56, 176–197. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/hojo.12199

- Castelli, P., & Goodman, G. S. (2014). Children's perceived emotional behavior at disclosure and prosecutors’ evaluations. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38, 1521–1532. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.02.010

- Conway, M. A., & Dewhurst, S. A. (1995). Remembering, familiarity, and source monitoring. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology Section A, 48, 125–140. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14640749508401380

- Dodier, O., Gilet, A., & Colombel, F. (in press). What do people really think of when they claim to believe in repressed memory? Methodological middle ground and applied issues. Memory. Manuscript accepted for publication.

- Dodier, O., Patihis, L., & Payoux, M. (2019). Reports of recovered memories of childhood abuse in therapy in France. Memory, 27, 1283–1298. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2019.1652654

- Ellenberger, H. (1970). The discovery of the unconscious. Basic Books.

- Erdeyly, M. H. (2006). The unified theory of repression. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 29, 499–551. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X06009113

- Houben, S. T. L., Otgaar, H., Roelofs, J., Wessel, I., Patihis, L., & Merckelbach, H. (2019). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) practitioners’ beliefs about memory. Psychology of Consciousness: Theory, Research, and Practice. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/cns0000211

- Kube, T., & Rozenkrantz, L. (2020). When beliefs face reality: An integrative review of belief updating in mental health and illness. Perspectives on Psychological Science. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620931496

- Laney, C., & Loftus, E. F. (2008). Emotional content of true and false memories. Memory (Hove, England), 16, 500–516. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09658210802065939

- Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K. H., Seifert, C. M., Schwarz, N., & Cook, J. (2012). Misinformation and its correction: Continued influence and successful debiasing. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 13, 106–131. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100612451018

- Lilienfeld, S. O., Ritschel, L. A., Lynn, S. J., Cautin, R. L., & Latzman, R. D. (2013). Why many clinical psychologists are resistant to evidence-based practice: Root causes and constructive remedies. Clinical Psychology Review, 33, 883–900. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2012.09.008

- Lindsay, D. S., & Read, J. D. (1995). “Memory work” and recovered memories of childhood sexual abuse: Scientific evidence, and public, professionals, and personal issues. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 1, 846–908. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1348/135532508X298559

- Loftus, E. F. (1994). The repressed memory controversy. American Psychologist, 49, 443–445. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.49.5.443.b

- Loftus, E. F. (2005). Planting misinformation in the human mind: A 30-year investigation of the malleability of memory. Learning & Memory, 12, 361–366. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1101/lm.94705

- Loftus, E. F., & Davis, D. (2006). Recovered memories. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 2, 469–498. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095315

- Loftus, E. F., & Ketcham, K. (1996). The myth of repressed memory: False memories and allegations of sexual abuse. Macmillan.

- Loftus, E. F., & Pickrell, J. E. (1995). The formation of false memories. Psychiatric Annals, 25, 720–725. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3928/0048-5713-19951201-07

- McNally, R. J. (2003). Remembering trauma. Belknap Press/Harvard University Press.

- McNally, R. J. (2005). Debunking myths about trauma and memory. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry / La Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie, 50, 817–822. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/070674370505001302

- McNally, R. J., & Geraerts, E. (2009). A new solution to the recovered memory debate. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4, 126–134. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01112.x

- Merckelbach, H., Dekkers, T., Wessel, I., & Roefs, A. (2003). Amnesia, flashbacks, nightmares, and dissociation in aging concentration camp survivors. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 41, 351–360. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(02)00019-0

- Merckelbach, H., & Wessel, I. (1998). Assumptions of students and psychotherapists about memory. Psychological Reports, 82, 763–770. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1998.82.3.763

- Odinot, G., Boon, R., & Wolters, L. (2015). Het episodisch geheugen en getuigenverhoor. Wat weten politieverhoorders hiervan? [Episodic memory and eyewitness interviewing. What do police interviewers know about this?]. Tijdschrift Voor Criminologie, 57, 279–299. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5553/TvC/0165182X2016058003004

- Ost, J. (2003). Seeking the middle ground in the ‘memory wars’. British Journal of Psychology, 94, 125–139. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1348/000712603762842156

- Ost, J., Blank, H., Davies, J., Jones, G., Lambert, K., & Salmon, K. (2013). False memory ≠ false memory: DRM errors are unrelated to the misinformation effect. PLoS ONE, 8, e57939. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0057939

- Ost, J., Easton, S., Hope, L., French, C. C., & Wright, D. B. (2017). Latent variables underlying the memory beliefs of chartered clinical psychologists, hypnotherapists, and undergraduates. Memory (Hove, England), 25, 57–68. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2015.1125927

- Ost, J., Wright, D. B., Easton, S., Hope, L., & French, C. C. (2013). Recovered memories, satanic abuse, dissociative identity disorder and false memories in the UK: A survey of clinical psychologists and hypnotherapists. Psychology, Crime & Law, 19, 1–19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2011.598157

- Otgaar, H., & Candel, I. (2011). Children's false memories: Different false memory paradigms reveal different results. Psychology, Crime & Law, 17, 513–528. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10683160903373392

- Otgaar, H., Howe, M. L., Dodier, O., Lilienfeld, S. O., Loftus, E. F., Lynn, S. J., Merckelbach, H., & Patihis, L. (in press). Belief in unconscious repressed memory persists. Perspectives on Psychological Science.

- Otgaar, H., Howe, M. L., Patihis, L., Merckelbach, H., Lynn, S. J., Lilienfeld, S. O., & Loftus, E. F. (2019). The return of the repressed: The persistent and problematic claims of long-forgotten trauma. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14, 1072–1095. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691619862306

- Otgaar, H., Wang, J., Dodier, O., Howe, M. L., Lilienfeld, S. O., Loftus, E. F., Lynn, S. J., Merckelbach, H., & Patihis, L. (2020). Skirting the issue: What does believing in repression mean? Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 149, 2005–2006. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000982

- Patihis, L., Ho, L. Y., Tingen, I. W., Lilienfeld, S. O., & Loftus, E. F. (2014). Are the “memory wars” over? A scientist-practitioner gap in beliefs about memory. Psychological Science, 25, 519–530. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613510718

- Patihis, L., Ho, L. Y., Loftus, E. F., & Herrera, M. E. (2018). Memory experts' beliefs about repressed memory. Memory. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2018.1532521

- Patihis, L., & Pendergrast, M. (2019). Reports of recovered memories of abuse in therapy in a large age-representative U.S. National sample: Therapy type and decade comparisons. Clinical Psychological Science, 7, 3–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702618773315

- Petty, R. E., & Brinol, P. (2008). Persuasion: From single to multiple to metacognitive processes. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3, 137–147. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6916.2008.00071.x

- Porter, S., Yuille, J. C., & Lehman, D. R. (1999). The nature of real, implanted, and fabricated memories for emotional childhood events: Implications for the recovered memory debate. Law and Human Behavior, 23, 517–537. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022344128649

- Rajaram, S. (1993). Remembering and knowing: Two means of access to the personal past. Memory & Cognition, 21, 89–102. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03211168

- Rumney, P. N. S., & McCartan, K. F. (2017). Purported false allegations of rape, child abuse and non-sexual violence: Nature, characteristics and implications. The Journal of Criminal Law, 81, 497–520. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0022018317746789

- Sauerland, M., Otgaar, H., Maegherman, E. F. L., & Sagana, A. (2020). Allegiance bias in statement reliability evaluations is not eliminated by falsification instructions. Zeitschrift für Psychologie, 228, 210–215. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1027/2151-2604/a000416

- Sayfan, l., Mitchell, E. B., Goodman, G. S., Eisen, M. L., & Qin, J. (2008). Children's expressed emotions when disclosing maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect, 32, 1026–1036. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.03.004

- Scoboria, A., Wade, K. A., Lindsay, D. S., Azad, T., Strange, D., Ost, J., & Hyman, I. E. (2017). A mega-analysis of memory reports from eight peer-reviewed false memory implantation studies. Memory (Hove, England), 25, 146–163. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2016.1260747

- Simons, D. J., & Chabris, C. F. (2011). What people believe about how memory works: A representative survey of the U.S. Population. PLoS ONE, 6, e22757. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0022757

- Thorson, E. (2016). Belief echoes: The persistent effects of corrected misinformation. Political Communication, 33, 460–480. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2015.1102187

- van der Kolk, B. A., & Fisler, R. (1995). Dissociation and the fragmentary nature of traumatic memories: Overview and exploratory study. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 8, 505–525. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02102887

- Wagenaar, W. A., & Groeneweg, J. (1990). The memory of concentration camp survivors. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 4, 77–87. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.2350040202

- Walter, N., & Tukachinsky, R. (2020). A meta-analytic examination of the continued influence of misinformation in the face of correction: How powerful is it, why does it happen, and how to stop it? Communication Research, 47, 155–177. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650219854600

- Wessel, I., Albers, C., Zandstra, A. R. E., & Heininga, V. E. (2020). Early attempts at replicating memory suppression with the Think/No-Think task. Memory.

- Yapko, M. D. (1994a). “Suggestibility and repressed memories of abuse: A survey of psychotherapists’ beliefs”: response. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 36, 185–187. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00029157.1994.10403066

- Yapko, M. D. (1994b). Suggestions of abuse: True and false memories of childhood sexual trauma. Simon & Schuster.