ABSTRACT

This article contributes to the literature on the European border security industry with a network analysis of a new bipartite data set. The network is composed of speakers and their speech topics at a European border security conference taking place from 2008 to 2015. Speakers are linked to conferences by year of attendance and to speech topics to identify key actors and discourses using measures of centrality. A multiple regression quadratic assignment procedure (MR-QAP) is used to explain the continuity of conference speech topics. The centrality analysis reveals a number of “hubs” and the discourse analysis reveals a consistent focus on social control and surveillance over human rights. The MR-QAP regression suggests that shared discourses are driven by organisations which act as key speakers at many events, and whose discourses are prioritised over those of other actors. The article concludes with notes on the critical implications of the findings.

Introduction

The European border security industry has recently become a focus of scholarly, journalistic, and activist interest in the wake of the European migration “crisis” (e.g. Akkerman Citation2016). Since the 1980s, with the advent of carrier sanctions, migration control and border security in Europe have been outsourced and commercialised, leading to high profits for a number of non-state actors (Guiraudon and Lahav Citation2000, Leander Citation2010, Gammeltoft-Hansen and Sorensen Citation2013). With the reduction of defence spending across European Union (EU) countries since 2008 (SIPRI Citationn.d.), the market for security technologies has shifted towards so-called “dual-use” purposes, whereby defence products may have civilian uses and vice versa. Now a range of border security technologies can be bought and sold on the European market, with such technologies catalysing new social relations among various actors (Andersson Citation2016b).Footnote1

The European Commission has cast the emergent market for security technologies as profitable and full of politically neutral commodities, emphasising the creation of a common market for security technologies in order to overcome projected declines in the European market share for security technologies (Hoijtink Citation2014). Such a move has led to increased research funding and collaboration between EU institutions such as the Commission and key industrial actors such as the members of the European Organisation for Security (European Commission Citation2015). Through a harmonised border security market, the Commission aims for improved “political and institutional efficiency”, “operational effectiveness”, and “productivity and growth” (European Commission Citation2004, p. 13). As such, the “industry” of border security can be conceived broadly and “nebulously” to include both producers and users of border security products and services as well as intermediaries which contribute to the reproduction of border security (including traditional defence corporations) (cf. Boulanin Citation2012).

The global market for border security products (including only land and maritime borders) was worth approximately 29.33 billion USD in 2012, with the highest expenditure in North America (Frost & Sullivan Citation2014). The European land border market had an estimated value of 4.5–5.5 billion EUR in 2009, while the aviation and maritime security sectors of Europe have a market value of approximately 1.5–2.5 billion EUR each (Ecorys Research and Consulting Citation2009). The scale of the market for border security is expanding globally, with total growth expected to exceed 56.52 billion USD for land and maritime borders by 2022 (Frost & Sullivan Citation2014).Footnote2 The sale of arms and military services by the Top 100 largest arms-producing companies alone, by comparison, was worth 401 billion USD in 2014, a decline from previous years but still a large increase since 2002 (SIPRI Citation2016). Arms-producing companies in Europe are often the same producing civil security technologies, such as BAE Systems, Airbus, and Finmeccanica, among others (see Kumar forthcoming for a comprehensive overview).

The literature covering the border security industry is divided into three conceptual approaches – migration industries approaches, practice approaches, and industrial complex approaches. First, the migration industries approach argues that the commercialisation of migration management has been fed by the activities of private firms which are unaccountable (Gammeltoft-Hansen Citation2013). In parallel, Lemberg-Pedersen (Citation2013) demonstrates how private security companies have introduced securitised logics into EU decision-making by framing migration as in need of technological solutions, supplying border security technologies which generate their own demand through logics of risk management and promotion of technologies as a “fix”. As extension, Andersson (Citation2016a, Citation2016b) has produced in-depth insight into the “illegality industry” surrounding migration and how actors profit from undocumented migration, critically probing the harmful effects of the industry. Second, practice approaches scrutinise the diverse everyday tasks, roles, routines, interactions, discourses, and rationalities of border security professionals, including private actors (Cote-Boucher et al. Citation2014). For example, Prokkola (Citation2012) demonstrates how border security in Finland is not distinct from processes of neo-liberalisation, involving rationales of competitiveness and the market. Third, a number of scholars and activists have put forth the idea of a “security industrial complex” to refer to the partnerships between governments and industrial suppliers of security technologies which promote their own notions of security over other interests (Hayes Citation2006, Citation2009, Guittet and Jeandesboz Citation2010). The marketisation of civil security has been spurred by the security industrial complex, composed of multiple transnational business actors engaged in designing, marketing, and profiting from the selling of security technologies (Hayes Citation2006, Citation2009, Guittet and Jeandesboz Citation2010).

While these studies are crucial to our understanding of the European border security industry, by providing conceptual innovations and rich empirical context, none of the studies map key actors’ relations and discourses in a systematic or relational manner in order to understand which actors are more central or “powerful”. What is missing in the literature, and what this article provides as a fourth approach, is a “network” analytic approach which conceptualises the industry as composed of dynamic relations among diverse actors, and that these diverse relations can be observed, recorded, and analysed using appropriate methods (Soreanu and Simionca Citation2013). A network analytic approach can allow an analysis of the border security industry which reveals its relational structure, which actors are more “powerful” (i.e. central), and which events and which discourses are most prominent, pointing to why such actors and discourses are more prominent or not. Thus, this article provides a novel “network” approach to research the security industry, an approach currently lacking in the literature.

What the approaches outlined above share is reliance on qualitative methods, including ethnographic, interview-based, case study, and documentary and media analyses which do not allow us to capture the structural positions and discourses of particular actors, but does allow us to capture practices in situated contexts and the key rationalities and logics of the industry. Hills (Citation2006), for example, identifies multiple rationalities of European border security using case studies of states, but overlooks the dimension of privatisation and commercialisation of these rationalities. These methods, while very insightful, do not allow us to measure whether or not certain actors are more central or more vocal within the border security industry. Currently, the literature fails to grasp the relational network structure and discursive tropes and schemas of the border security industry even when we have detailed insights into its operation in specific contexts.

While some accounts mention actors and networks in passing (e.g. Andersson Citation2016a, pp. 7–8), none of the recent accounts of the European border security industry have employed network analytic methods to grasp the relational structure of the industry, and the literature lacks rigorous evidence that informs us about the social relations which undergird the border security industry. The implications are that studies of the border security industry may miss the relational embeddedness of political actors in network structures (Knoke Citation1994) by focusing on the rational interests of individual actors, their social practices, or the broad effects of such social fields. Furthermore, no work on the border security industry maps in detail the discourses of key actors involved. Thus, the main contribution of this article is to complement previous work with a network analytic perspective, offering new methods and new data to the field, allowing us to specify which actors have more centrality and which discourses hold sway over others in the industry.

Researching the border security industry in Europe is important for three main reasons. First, the border security industry is hard to access and difficult to research, so new research on the growing industry can shed light on an emerging (and opaque) community of actors which play a key role in the privatisation of migration management. Certain actors may be more powerful than others in the industry, and understanding this distribution of power can shed light on which discourses and rationalities are deemed central (or not). Second, there is growing evidence that business actors are influencing EU policies. For example, Jones (Citation2016, p. 4) demonstrates that:

The EU’s initiatives in security are wide-ranging, but they frequently dovetail with the interests of major security and defence companies: tools for mass data-gathering and predictive analytics, continent-wide surveillance systems and databases, the increasing use of biometrics in all walks of life, and the closer integration of public authorities and private industry.

Finally, the literature on security fairs and events in particular is limited but growing. Stockmarr’s (Citation2016, p. 189) pioneering work shows that security fairs are important sites for “the development of professions, technologies, markets, and industries”. The current article assumes that border security conference networks can be analysed as crucial sites for the (re)production of the border security industry, as sites where the producers, users, and intermediaries of border security products and services congregate. Thus, this article contributes to the literature on the border security industry with a social network analysis of a novel network data set of speakers and their speech topics at a major European border security industry conference taking place from 2008 to 2015.Footnote3

The main questions addressed by this article are: How is the border security industry in Europe structured? Who are the main actors and who do they most relate to? What discourses are employed by the main actors? A number of empirical questions arise related to the network data: Which are the most central organisations presenting at border security conferences? What is the significance of the network structure? What are the key discourses in circulation at the conferences? Do certain actors share certain discourses over others? Which discourses are absent? Which factors explain the persistence of some discourses over others? Are some actors’ discourses more prevalent than others? In other words, who speaks for the European border security industry?

In order to address these questions, the article presents an analysis of bipartite actor-event and actor-topic networks constructed from public data on SMi Border Security conferences from 2008 to 2015. In the actor-event and actor-topic networks, speakers are linked to conferences by year of attendance and by speech topics to analyse relations and patterns of co-affiliation and shared discourses among actors. The bipartite networks are graphed, visualised, and analysed using measures of centrality and speech topics to explore the main actors’ relations and the main discursive trends. Following the exploratory analysis, a multiple regression quadratic assignment procedure (MR-QAP) is used to explain the continuity of conference speech topics. The article begins with a description of the data and methods, then procedures to the exploratory network analysis, and then to the MR-QAP regression. The article concludes with critical implications arising from the findings.

Data and methods

The empirical data come from a novel data set comprising two unique bipartite networks. The first is an actor-event network, and the second is an actor-speech topic network, both built from publically available data.Footnote4 Data come from publically available conference schedules for the SMi Border Security Conference from 2008 to 2015, obtained online. SMi Group is a UK-based event production company which specialises in assembling defence, security, energy, finance, and pharmaceutical conferences, workshops, and trainings.Footnote5 Since 2008 it has produced annual conferences on border security, advertised as arenas for promoting and marketing security technologies as well as security services to both governments and industry.Footnote6 SMi Border Security conferences are sponsored by a range of actors, primarily from private industry. SMi Border Security conferences are one of a range of annual conferences in the industry, the largest being the annual Border Security Expo held in the USA, and the World Borderpol Congress, held internationally, among others.Footnote7 The multi-annual speaker data for the other conferences were either incomplete or not public. The value of the current data set lies in its recording of relations among key actors within the industry which speak about the major topics of border security. The networks give us insight not into who attends, but who speaks for the border security industry, and to tease out the reasons why these actors are speaking and being heard over others.

There is a lack of available data sets on the European border security industry. In order to address this lack, we can begin to build limited data sets which give insight into the industry, its structure, main actors, and key field-configuring events. Alternative data sets, built from Frontex conferences or alternative conferences such as the North American Border Security Expo, could be possible for future work, even when the compilation and analysis of such data sets is time consuming and cumbersome. The consequences of omitting these other conferences is that we may miss specific actors and speech topics, but compared to existing research on EU FP7 projects (Baird Citation2016), the current data set provides a comparable representation of the key actors and key topics engaged with at security conferences. While other conferences may be larger, it is very difficult to determine whether SMi conferences are more or less representative – there are a number of border security conferences attended by similar actors with similar discussions, but there is no measure of the impact or importance of particular events over others. Thus, rather than attempting to generalise to the entire border security industry, the current methods allow us to make an exploratory foray into specific actors and discourses present in the European border security industry, specifically one series of events which is organised by a UK-based event production company which is attended annually by a number of key actors across Europe. In comparison with other findings in the literature, we can then make more generalised comments about the industry. Since much of the literature on the industry is qualitative, the current methods provide us a more structural and relational picture than could otherwise be represented, providing a solid complement to existing work while also going beyond it – the analysis will show how shared border security discourses are driven by powerful “hubs” which act as key speakers at many events, driving particular logics towards the centre at the expense of other discourses.

Actor-event network

Data were obtained by collecting the online and publically available conference programmes from 2008 to 2015. Regrettably, data previous to 2008 are not available. For each year, a two-mode actor-event (or bipartite) network was constructed (Borgatti and Everett Citation1997, Hanneman and Riddle Citation2005, Borgatti and Halgin Citation2011): each actor which presented and publically spoke at the conference was identified and recorded as having a tie to that year, with multiple actors having ties to multiple years as they spoke at multiple conferences. Only those who presented for the programme were identified, as full attendee lists were not publically available. Each speaker’s organisation, geographical location of their organisation, and the type of organisation were recorded alongside the tie. Individual names were not recorded, only organisational names and types.

The actor-event network data were analysed as two-mode data as it is assumed that actors speaking on conference panels are not likely to meet all the other actors speaking during that year’s conference. Thus, converting to a one-mode network is not appropriate in this case, and tie data are analysed using the two-mode relations. Analysing two-mode network data requires some modification of typical graph measures for one-mode data, as some information may be lost in projecting from two-mode to one-mode (Borgatti and Everett Citation1997, Latapy et al. Citation2008, Borgatti and Halgin Citation2011, Everett and Borgatti Citation2013, Vernet et al. Citation2014). In the current analysis, the network will be analysed as two-mode, using standard measures of two-mode centrality (Borgatti et al. Citation2013).

Important characteristics of networks are the connections of their most central actors. I calculated two key measures of centrality: eigenvector and betweenness centralities (Borgatti and Everett Citation1997, p. 253 ff). The following loose definitions of centralities apply to the current analysis. While degree centrality is a measure of the number of links (i.e. edges) connected to an actor (i.e. vertex/node), eigenvector centrality measures the degree of a node in proportion to the surrounding nodes’ degrees. In other words, more nodes will have higher eigenvector centrality due to their connection with other well-connected nodes. In this case, a high degree centrality would indicate that an actor attends a conference with many other actors, while eigenvector centrality indicates that an actor attends conferences which are attended by well-connected actors which attend many conferences. Betweenness centrality measures the number of geodesic paths that pass through a node, with nodes that have many paths criss-crossing them acting as “brokers” between communities of nodes (Stovel and Shaw Citation2012). In this case, a higher betweenness means an actor attends many conferences which are attended by many other actors.

Actor-topic network

The article also analyses the discourses employed by the speakers at the conferences. On the flyers for each conference, speakers were listed with speech topics and short bullet-point abstracts of the main points and content of their talks. These speech topics were recorded by actor and by year in order to determine which discourses are most prevalent (continuity) and to uncover if any particular topics are missing or are receiving more attention than others (rupture) (Mutlu and Salter Citation2013). Since the data come from speech topics and summarised contents and not the full content of speeches themselves, some bias in results may arise: words may be over-represented in the title compared to the content of the speeches, and speakers may use different definitions for similar words. With these limitations in mind, the actor-topic data do reveal which keywords are being used by which actors, demonstrating how certain actors are linked with particular discourses and their trends.

The main topics were put into a list form using the Word Cruncher tool in atlas.ti 7.5.4, using a standard stop list of common words, in order to obtain a yearly list of keywords by frequency. The yearly list of keywords was then treated as a bipartite actor-topic edge list and converted to a weighted matrix using Ucinet 6.523 (Borgatti et al. Citation2002). The resulting weighted matrix was graphed and analysed using degree centrality to determine the most well-connected topics, that is, the most discussed, in order to understand discursive continuity across conferences. Rupture, or missing discourses, was analysed by looking at which keywords received very little or no attention according to the Word Cruncher output. The main limitation of the discourse network is that the Word Crunch does not parse for phrases but only for individual words, which unbundles sentences and phrases into individual word chunks. The output in the sections below will discuss the findings further.

Quadratic assignment procedure correlation and regression

In order to understand the persistence of some discourses in the network, in other words which factors contribute to actors sharing speech topics and thus which actors’ discourses are prioritised, a quadratic assignment procedure (QAP) correlation and multiple regression (MR-QAP) were performed.

QAP correlation is used to correlate matrices by reshaping the matrices into columns and then calculating standard regression coefficients (Borgatti et al. Citation2013, p. 128). Significance is calculated by constructing thousands of permutations of independent matrices which resemble the observed matrices and then solving for the proportions of correlations among the independent matrices compared to the observed matrices (Borgatti et al. Citation2013, pp. 128–129). A large number of permutations are necessary in order to calculate a more accurate p-value. The results of the correlations show the extent to which ties are related between two matrices. The QAP correlation allows us to see which actors are likely to share speech topics depending on network and attribute variables (see below).

While the QAP correlation points us in the direction of important variables which may explain the persistence of speech topics, network dependence can be modelled using a related permutation strategy called the MR-QAP (Borgatti et al. Citation2013, pp. 129–133). Since network ties are not independent (and thus not suitable for parametric statistical methods which assume independence), MR-QAP is a non-parametric approach to network dependence relying on a comparison of the observed matrices with permutations of random matrices in order to compute p-values, while regression coefficients are calculated using Ordinary Least Squares (Krackhardt Citation1987, Dekker et al. Citation2007). Results can be interpreted as would a standard multiple regression, and p-values estimate the probability that the correlation coefficients could have been calculated by chance among the permuted random matrices. If coefficients of the random permuted matrices are a result of sampling error, then the probabilities would be high. Low p-values mean that the observed correlation has a low probability of being random. MR-QAP has been shown to produce unbiased coefficients (Krackhardt Citation1988). Results were not corrected for heteroscedasticity (Lindgren Citation2010).

In this article, the MR-QAP is used to assess the impact of six network structural and organisational attribute variables on speech topic ties. Calculations were done using Ucinet 6.523 using the Double Dekker Semi-Partialling MR-QAP algorithm (Borgatti et al. Citation2002, Dekker et al. Citation2007). In order to carry out the QAP regression, the two-mode networks were converted using the affiliations function in Ucinet. The affiliations function assumes a tie between two actors if they both attend the same event or both speak about the same topic (i.e. use the same topic word). Attributes of the various actors, including their type of organisation, location of headquarters, or whether they were an invited speaker, were recorded and converted to one-mode matrices. Network attributes, such as whether an actor attended the same event, and their centralities were also converted into one-mode networks in order to correlate the matrices.

lists the descriptive statistics of the main variables used in the QAP regression, modelling the effect of two sets of independent variables (network structure variables and organisational attribute variables) on the dependent variable of shared speech topics. Shared speech topics were measured using co-affiliation if actors were linked to the same topic word.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for dependent and independent variables.

The network variables capture the effect of structural position within the network. Event co-attendance is based on the two-mode actor-event network. This article assumes that if actors have ties to the same events, they are likely to have strong ties to the same topic words, and asks whether speaking at the same event means you are speaking about the same topic. Eigenvector and betweenness centralities are meant to capture the “power” of a particular actor based on their position in the network, with more “powerful” actors, that is, more central and between, assumed to share more speech topics than others. The centrality matrices were calculated using the identity coefficient, which measures the correlation of each actor with itself. The other matrices were calculated using sums of overlaps.

The attribute variables are meant to capture various characteristics of speakers. Do similar actors share similar discourses? For example, do private actors tend to speak about the same topics at conferences? We would expect that more similar actors would adopt more similar discourses. Actors were classified by type of organisation. Type of organisation was coded using fourteen categories: academic research organisation, applied research organisation, defunct, EU agency, governmental (national organisation), individual/independent of an organisation, inter-corporate organisation (such as a business federation), intergovernmental military alliance (NATO), intergovernmental organisation (i.e. UNHCR), non-profit, for-profit private firm, quasi-governmental (e.g. public–-private partnership organisations), research and development projects, and think tanks. The location of an organisation’s headquarters was coded using nationality, and is meant to assess the extent to which particular national contexts influence speech topics. Are certain national discourses more important than others? Finally, many speakers are invited to participate in conferences, while others apply to speak. To capture these selection mechanisms – whether speakers are socially selected or self-select to speak at a conference – speakers were coded by whether or not they held important positions, that is, were chairman, held a keynote speech, gave a special address, gave a host nation address, at the conference or not. This final variable is labelled as “invited speaker” to denote the selection mechanisms of speakers.

Analysis

This section presents the visualisations and results of an exploratory network analysis of the two networks before proceeding to the QAP regression.

Actors and relations

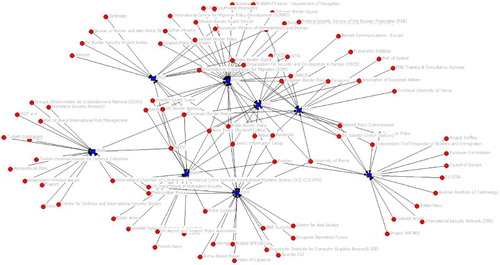

The centrality data show that the most central actors in the network are mainly governments (primarily border police), private firms, EU agencies, academic research organisations, and intergovernmental organisations. Non-central actors include applied research organisations and other research and development projects, think tanks, quasi-governmental organisations, inter-corporate organisations (such as business federations), individuals, and defunct organisations. It is perhaps surprising that we do not see representatives of other EU institutions such as the European Parliament at the conferences, given the important roles Members of the European Parliament have played in shaping border control policies (Huber Citation2015). In we see the graph of the bipartite actor-event network. The number of actors in the network is 87 and the number of events is 8, with a density of 0.214. In we can see the top ten organisations by multiple measures of centrality. Eigenvector centrality measures the centrality of a node based on its connections with its neighbour nodes. Well-connected organisations which attend conferences with other well-connected organisations will have higher eigenvector centralities. Eigenvector centrality gives us a sense of the “rank” of the organisation within the network (Heemskerk et al. Citation2013). Betweenness centrality measures the position of a node between different parts of the network, or the degree to which an organisation may act as a “broker” between different events and organisations (Stovel and Shaw Citation2012). High betweenness means that the organisation attends many events which are also attended by many actors.

Figure 1. Graph of the two-mode actor-event network.

Table 2. Top 10 organisations ranked by eigenvector and betweenness centralities.

In order to see if a node is both well-connected within a part of the network and acts as a bridge, or a “broker”, between other parts of the network, we can combine two network measures – eigenvector centrality and betweenness centrality (Heemskerk et al. Citation2013). In we can see those organisations which have both high eigenvector centralities and high betweenness by their grey shade. These organisations are both centrally connected to other well-connected organisations and act as brokers between different parts of the network. We can think of these organisations as “hubs” through which information, norms, or discourses of the border security industry emerge from and pass through to other organisations (Heemskerk et al. Citation2013). Primarily government organisations (border police), private firms, Frontex (the European Agency for the Management of Operational Cooperation at the External Borders of the Member States of the EU), and NATO act as hubs within the network. These types of organisations both speak at many events and are well-connected at the events they do speak. In addition, some organisations are highly central but not between (they do not broker), or are between (they broker) but are not highly central. These findings are important for the discussion of the factors that influence the sharing of discourses, discussed below in the section on discourses.

In the degree centralities of the events rise until 2011, then fall, meaning more speakers were presenting at SMi Border Security conferences until 2011 and then less speakers have presented since then. This finding suggests that the popularity of the Border Security conference improved until 2011, and has been in relative decline since then, or that the event promoters have been unable to pay for more speakers since 2011 ().

Table 3. Degree centralities for yearly border security conferences.

Table 4. Top 10 locations of organisational headquarters.

The locations of headquarters of organisations speaking at SMi Border Security events are diverse and trans-European. Organisations based in Eastern Europe are well represented (primarily Poland and Romania, as well as others, see also ), as well as organisations based in countries with active border security industries (UK, Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands, among others). The strong presence of Eastern European organisations reveals that new Member States are playing an increasingly important role in the European border security industry. Note that the location of Frontex is located in Warsaw, perhaps exerting influence on the network structure through geographic proximity.

Organisations from the USA are also well represented at conferences, as the US border security market is robust, and the main speakers from the USA include almost exclusively the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and private firms (Arinc Emea (Rockwell Collins), Jane’s Information Group, Cisco, and Southwest Microwave). This suggests that US-based organisations potentially inhabit structurally important positions within the “European” border security industry.

Discourses

Mutlu and Salter (Citation2013) argue that there are three dominant strategies to analyse discourses, concentrating on the themes of continuity and rupture. “Plastic” discourse analysis focuses on continuity, or “the identity of linguistic signs and tropes or the persistence of a particular metaphorical schema” (Mutlu and Salter Citation2013, p. 114). In this article, the analysis of continuity explores the most central speech topics in the bipartite (speech-year) discourse network in order to understand the dominant signs employed within the border security assemblage. In parallel, “genealogical” discourse analysis “seeks ruptures, silences, breaks, marginalized voices or subjugated knowledges” (Mutlu and Salter Citation2013, p. 114). The focus on ruptures is done by looking at which speech topics are absent or which topics receive very little attention among actors at border security conferences. The key results are discussed below.

Continuity

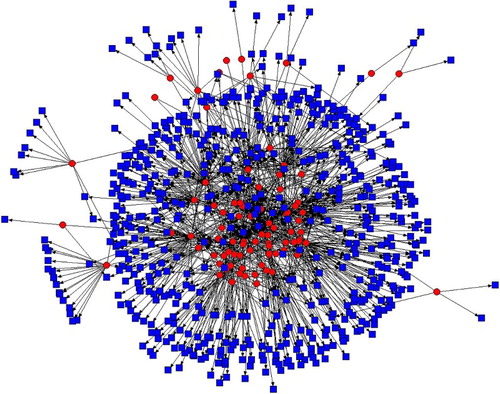

In we see the graph of the bipartite actor-topic network. The number of actors in the network is 87 and the number of speech topics is 585, with a density of 0.024. In we see the continuities among different speech topics in the border security assemblage across yearly events. When we look at the common underlying themes, we find a focus on signifiers of control and management, cooperation and integration, surveillance and information, threats and challenges and risks, among others. These continuous discourses can be seen as the “master signifiers” of the border security industry which have remained dominant over time and across conferences (Mutlu and Salter Citation2013, p. 115).

Figure 2. Graph of the two-mode actor-topic network.

Table 5. Top 25 speech topics ranked by degree centrality.

The results in show that metaphors of (in)security, associated with the discourses of “threat”, “challenge”, and “risk”, are consistent at the conferences. The embracing of the language of (in)security over alternative discourses has become a discursive resource for rendering an “uncertain future securable (as opposed to secure)” (Amoore Citation2013, p. 72). We see a parallel focus on institutional collaboration, from the language of interoperability to integration to management. These discourses are spoken alongside a consistent focus on “cooperation”. Based on the organisations employing such terms, the language of interoperability and integration and management is primarily one of state actors, EU agencies (especially Frontex, tasked with operational coordination), and international organisations (such as NATO) seeking greater cooperation and coordination among themselves to enhance control of European external borders and “manage” migration using (para)militarised means. Further evidence demonstrates that Frontex activity contributes to the securitisation of migration through its practices (Léonard Citation2010), with the current discursive findings in support of earlier findings. Similarly, the language of surveillance coincides with the establishment of the European Border Surveillance System in 2013.Footnote8 Such a focus indicates reliance on a language of reconnaissance and technological observation, with new ways of “seeing” arising alongside such discourses.

Finally, discourses of effectiveness appear. Various phrases refer to divergent meanings of efficiency and effectiveness throughout the speeches. For example, where the Bulgarian Police refer to “Cooperation with neighboring countries: an efficient tool in combating illegal migration and increasing border security”, signalling a logic of operational efficiency, Panasonic refers to a market logic when saying “Mobile Technology drives efficiency”. However, various phrases are employed by both market and state actors interchangeably over the years, such as “Cost-efficiency at borders”; “Maximise efficiency and minimise risk”; “effective European cooperation”; “Effective security”; “Ways to improve efficiency while maintaining security”; “Strategic, operational, and tactical levels for sustainable and effective border management”; and “Effective communication”. The interchangeable use of each phrase among state and market actors points to the multiple ways in which efficiency and effectiveness are conceived, not only as market tools, but also as organisational logics to produce a particular vision of border security. Birch and Siemiatycki (Citation2016, p. 187) suggest that “rationalities of efficiency and inefficiency and value for money (VFM) are related to one another, although distinct in that the former reflect a rationality of market actors and the latter a rationality of the state”. However, the analysis of discursive continuity presented here suggests a related trend: discourses are shared between diverse public–private and civilian–military organisations, lending support to the theses that the fields of public–private relations and civilian–military relations are more blurred (Bigo Citation2006).

Rupture

The search for discursive “silence” within the network reveals a number of inconsistencies and absences of topics (Mutlu and Salter Citation2013). For example, there is an inconsistent and low proportion of discourse of rights and ethics: while the average percentage of all words appearing in the network is roughly 0.002 (with the average percentage of top 25 words being 0.014), the languages of “rights” appear less than the overall average (0.001) and ethics less than the top 25 average (0.004). The language of rights is confined to a topic engaging with balancing rights and security (UNHCR) and the rights of those who have been trafficked (Council of Europe). While the discourse of “protection” is present, and rises, it is primarily associated with border protection and data protection, not refugee protection or human rights protection, with one exception: UNHCR refers to the “Balance between protecting borders and protecting the rights of those in need of protection” and “Europe as a region of migration and protection”. The discourses of accountability, responsibility, and transparency are completely missing from the speech topics, perhaps reproducing the multiple legal uncertainties present at the southern European borders (Del Sarto and Steindler Citation2015). In addition, the language of “emergency” and “crisis” is largely lacking, even in the midst of the financial and migration “crises” confronting Europe. With the increasing number of migrant deaths in the Mediterranean and in light of claims surrounding Eurosur as a life-saving system (Rijpma and Vermeulen Citation2015), more research is needed to uncover the extent to which actors use discourses of saving lives. However, in an environment where business actors profit from technologies used in the control of vulnerable populations (which may result in rights violations), it is important to note that business actors have important obligations to respect human rights, according to Principle 11 of the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (United Nations Office of the Commissioner for Human Rights Citation2011). These obligations imply that actors in the border security industry have a duty to discuss human rights openly at their commercial events.

QAP correlation and MR-QAP regression

A number of questions arise from the preceding exploratory analysis. How can we explain discursive continuity within the border security industry? Which actors speak about the same topics? Which factors influence the sharing of a speech topic? Do “hub” actors share certain speech topics? What are the implications for powerful actors sharing similar speech topics? These questions are addressed using the QAP regression method outlined in the Data and Methods section.

The results of the QAP correlation are reported in as Pearson correlations with probabilities in parentheses. The results indicate a moderate positive and probable correlation with shared speech topics with event co-attendance and betweenness (two network variables), and slightly moderate positive and probable correlations with type of organisation and invited speakers. The findings support our assumptions that certain “hubs” share speech topics and that the type of organisation and selection matter, but further modelling to check the strength of the correlations is needed.

Table 6. QAP correlations among main variables.

reports the results of the MR-QAP, which are interpreted with the aid of Hanneman and Riddle (Citation2005). The coefficients are tested through three models. The first model tests all sets of variables, with models two and three testing the network variables and the attribute variables, respectively. The results of each model indicate that both network structure and organisational attributes are associated with the sharing of speech topics. Model one’s adjusted R-square indicates that network structure and organisational attributes together influence the sharing of speech topics by about 26%. The intercept shows that if these variables were not present, then the probability that actors share speech topics is very low. With the two sets of variables present, 26% of the variation of speech topics is explained, with other outside factors explaining the rest of the variance. Overall, event co-attendance, betweenness centrality, and being an invited speaker are most important in determining the extent to which organisations share speech topics, with the type of organisation also retaining some importance.

Table 7. MR-QAP regression models: standardised regression coefficients.

Event co-attendance is an important predictor of shared speech topics for two reasons. First, conferences and panels are organised around particular discursive themes, meaning that actors presenting at certain conferences and on certain panels will share topics (the sharing of topics on panels was not measured, however; only conference-level speaking was measured). Second, some actors speak at conferences because of the particular themes, meaning they choose to speak about certain topics over others (such a dynamic is also captured by the “invited speaker” variable). Thus, event co-attendance and speech topics are more likely than other variables to strongly associate due to the fact that certain conferences deal with certain discursive themes and not others.

Betweenness centrality measures the structural positions of “brokers” within the network (Stovel and Shaw Citation2012), in this case representing the value of attending multiple conferences where many others attend. Brokers are structurally positioned within the network to benefit from the sharing of topics among disparate parts of the network. By bridging network ties, a broker “trades on gaps in social structure” and “helps goods, information, opportunities, or knowledge flow across that gap”, thereby acting as catalysts for the sharing of particular speech topics (Stovel and Shaw Citation2012, p. 141). Private firms, EU agencies, governments, intergovernmental military alliances (NATO), and universities act as the main types of organisational brokers in the network (), as opposed to non-brokers such as applied research organisations, think tanks, quasi-governmental organisations, inter-corporate organisations (such as business federations), individuals, and defunct organisations. This suggests that certain “hub” actors mentioned above may drive the sharing of speech topics within the industry.

Perhaps surprisingly, the coefficients for eigenvector centrality are slightly negative, with a slightly higher probability (in comparison) that the results are random. These results suggest that attending a conference with many others who are well connected does not necessarily mean you will share speech topics. Being popular does not mean you will speak about popular topics. Simply speaking with other well-connected actors does not mean you will necessarily share discourses, as you may be connected with actors with differing topics from your own (imagine a panel comprising diverse organisations speaking about different aspects of border security; for example, how many actors speak at an event to hear the other side rather than speak about the same thing?). However, if you speak at many conferences and speak alongside other actors who speak at the same conferences (thus having high betweenness), you are more likely to speak about the same topics.

Whether or not your organisation is governmental or private or an EU agency may matter, but is not as important as other attributes. In some cases, it may be that private firms share the same discourses, but this is not necessarily the case. Nevertheless, the organisational similarity does matter to some degree, unlike the location of one’s organisational headquarters, which has a coefficient which is neither strong nor significant. These results suggest that where a particular type of organisation is based is not so important in determining when speech topics are shared. We could infer from these results that other transnational factors are more important in determining speech topics, such as the characteristics of the transnational border security regime in Europe.

Being an invited speaker is an important indicator whether an organisation will share speech topics with others. This implies that self-selected speakers speak about topics which resonate with many other organisations. Invited speakers are likely perceived as more powerful, or perceived to have important insight, or perceived to be leaders within the industry, so what they speak about may be seen as a primary source by other organisations and by other invited speakers in the industry. Alternatively, invited speakers are more likely to share speech topics with other invited speakers because the themes of invited speeches are similar. This is not necessarily the case when we look at the types of topics of invited speakers, which is diverse. Thus, certain invited speakers “lead the discursive way” or “set the discursive tone” for other organisations by formulating topics in particular ways.

In sum, discourses about border security exhibit more continuity among actors which, by level of effect (1) act as brokers (i.e. have high betweenness), (2) attend many events, (3) are socially selected (i.e. are invited speakers), and (4) are organisationally similar (i.e. private actors speak about similar topics as other private actors and so on). Other factors are less important, such as the geography (the location of an organisation’s headquarters) and popularity (measured by eigenvector centrality). In other words, shared border security discourses are driven by powerful “hubs” which act as key speakers at many events.

While these results indicate discursive trends in the border security industry, there are some important caveats. First, the findings suggest association, not causality. Second, when interpreting the R-squared we should keep in mind that the network variables may be overestimated because of the structure of the data: event co-attendance is related to centrality as centrality scores are calculated based on event co-attendance. Third, actors in the industry may belong to similar communities (Baird Citation2016), implying that actors adopt similar discourses because they use common concepts circulating in the community, rather than adopting discourses because of the power of actors in the community. The results of the MR-QAP regression, however, point to the influence of powerful actors on the adoption of discourses, but more research using community detection methods is needed to address the issue of which discourses are adopted by particular communities. Nevertheless, the results point to some intriguing associations between social structure and organisational attributes in explaining which actors are likely to share discourses about security, as well as why and when.

Conclusion

This paper introduces new network data to the debate on the border security industry in Europe. The analysis helps us to understand how public speeches by key actors in the border security industry shape European border security discourses. Compared to existing knowledge, the current analysis provides the first systematic outline of discursive trends in the border security industry, and complements existing work on the structure of the border security industry (Baird Citation2016). Compared to other literature on the topic, the article is the first to highlight the role that central actors play in shaping topics of discourse within the border security industry and map these actors, their relations, and specific speech topics. Additional findings concerning the topics of speeches provide corroboration that a discourse of human rights and protection is sidelined in debates on border security in Europe, and that the interests of industry supersede those of other actors promoting fundamental rights norms (Bigo, Jeandesboz, Martin-Maze, and Ragazzi Citation2014). Furthermore, this article can offer other fields of study of European security – such as biometrics, environmental security, counterterrorism, energy security, or non-proliferation – methods and insights which are relevant to mapping and measuring key actors and discourses across fields. Understanding which actors are more central and which discourses drive these alternative fields could shed light into common discursive trends which traverse communities of security professionals.

The main importance of this article lies in the significant associations between shared speech topics and the positions and characteristics of key actors speaking at European border security conferences. Discourse within the border security industry can be partly attributed to two types of factors: (1) structural network factors related to the position of speakers who co-attend border security conferences and (2) attribute factors related to the characteristics of organisations which attend border security conferences. The principal finding of the study is that similar organisations which act as “hubs” or brokers, and invited speakers which speak at many events, are more likely to share discourses about border security than other organisations with different network positions and attributes.

There are three critical implications of such a finding for the literature on the border security industry. First, as argued in the introduction, the literature on the security industry is largely dominated by qualitative methods, and this article complements the literature by adopting a “network” approach. The novel application of social network analysis opens up new avenues for research on the security industry. With security technologies being bought and sold globally, we can research the network structure, discourses, and effects of actors operating in alternative contexts, as in the case of Mauritania (Frowd Citation2014).

Second, the results suggest that actors which share certain positions and characteristics are likely to speak about the same or similar topics, meaning discourses among such actors are more convergent than divergent. In the case of border security conferences, the findings suggest that convergent discourses of risk, surveillance, efficiency, and social control far supersede and thus limit a discourse of human rights and refugee protection. Private firms, state actors, and EU agencies use discourses of control and surveillance, while intergovernmental organisations focus on a discourse of human rights and production in the network. If there is a strong convergence between the discourse of governments, private firms, and EU agencies, convergent discourses limit the possibilities for speaking about alternative topics, leading to particular discursive “lock-in” effects whereby the discursive framing of an issue is limited, closing off important avenues for political action. Furthermore, the lack of civil society organisations in the network, in the form of non-governmental organisations concerned with fundamental rights, may exacerbate current tendencies of the “illegality industry” to have harmful effects (Andersson Citation2016a). Businesses have obligations to respect human rights, and the security industry is not an exception to this norm. There is thus a need to emphasise divergent and alternative discourses in the border security debate in Europe if we are to enhance the protection of human rights.

Finally, by focusing on the relational structure and the effects of structure and attributes on discourse, we gain valuable insight into the border security industry not captured by approaches focusing on practices or social fields (Cote-Boucher, Infantino, and Salter Citation2014). These approaches are complementary, and network analysis provides us valuable tools to unpack the social structure and effects of the border security industry. Perhaps future work could combine these approaches to achieve novel combinations of methods involving ethnographic practice-based approaches with network analysis that pays critical attention to the harmful effects of the border security industry. By mapping which actors hold structurally central positions, combined with an ethnographic insight into social processes, we could begin to uncover which actors may be accountable for rights violations when they occur.

Acknowledgements

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the Dutch Association for Migration Research (DAMR)/Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek- en Documentatiecentrum (WODC) Spring Meeting, Ministry of Security and Justice, the Hague, 27 May 2016. Thanks to the attendees for the discussion and comments. Thanks to Martijn Stronks and Margarita Fourer at VU Amsterdam for discussion and insight, and thanks to the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions and comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes on contributor

Theodore Baird is a post-doc researcher working in the Migration Law Section at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. His book Human Smuggling in the Eastern Mediterranean is published by Routledge.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Examples of border security technologies include a range of sensors, scanners, and detectors (video/visual, x-ray, acoustic, thermal, and kinetic); radars (land-based, sea-based, and space-based); mobile biometric devices (such as fingerprint and facial scanners); heartbeat and CO2 detection equipment; unmanned aerial vehicles (drones); fences and fence-mounted devices; integrated IT solutions (data storage, analysis, and networking); solar power; and a range of other devices designed for integrated use for border and infrastructure protection.

2. It should be noted that estimates for the size of the border security market provided by Frost & Sullivan and Ecorys are broadly incomparable, using different methods to arrive at alternative estimates. Estimates should be treated with caution. An estimate which covers only the control of international migration does not exist – typically estimates are broken down by type of border (land, air, and sea), not type of control. Furthermore, border security technologies are not exclusively used to control international migration, but are multipurpose, being used in the control and prohibition of a range of practices (customs, terrorism, piracy, organised crime, etc.).

3. By speech topics I do not refer to speech acts as theorised in the literature on securitisation, or a conceptualisation of speech acts which move an issue from the realm of everyday politics to the exception. My use of speech topic is more pedestrian, referring simply to the topics of speeches given at border security conferences and fairs.

4. Only the elements of social network analysis directly relevant for the current analysis will be covered. For an introductory discussion to social network analysis in security studies, see Knoke and Yang (Citation2008), Soreanu and Simionca (Citation2013). For general introductions to the topic, consult the following: Borgatti et al. (Citation2013), Scott and Carrington (Citation2011), and Wasserman and Faust (Citation1994).

5. According to the SMi Group Ltd. website, available online at: https://www.smi-online.co.uk/ [Accessed 16 July 2015].

6. For example, see conference materials available online at: https://www.smi-online.co.uk/defence/europe/border-security [Accessed 16 July 2015].

7. See, for example: http://www.bordersecurityexpo.com/, http://www.borderpol.org/, http://world-border-congress.com/, http://www.smarterborders.com/, http://www.beyond-border.com/, and http://www.airportsecurityconference.com/.

8. Regulation (EU) No 1052/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 October 2013 establishing the European Border Surveillance System (Eurosur), OJEU L 295/11-26, 6 November 2013.

References

- Akkerman, M., 2016. Border wars: the arms dealers profiting from Europe’s refugee tragedy. Transnational Institute (TNI) and Stop Wapenhandel, 4 July [online]. Available from: https://www.tni.org/en/publication/border-wars [Accessed 07 Dec 2016].

- Amoore, L., 2013. The politics of possibility: risk and security beyond probability. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Andersson, R., 2016a. Europe’s failed “fight” against irregular migration: ethnographic notes on a counterproductive industry. Journal of ethnic and migration studies, 42 (7), 1055–1075. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2016.1139446

- Andersson, R., 2016b. Hardwiring the frontier? The politics of security technology in Europe’s “fight against illegal migration”. Security dialogue, 47 (1), 22–39. doi: 10.1177/0967010615606044

- Baird, T., 2016. Surveillance design communities in Europe: a network analysis. Surveillance & society, 14 (1), 34–58.

- Bigo, D., 2006. Internal and external aspects of security. European security, 15 (4), 385–404. doi: 10.1080/09662830701305831

- Bigo, D., et al., 2014. Review of security measures in the 7th research framework programme FP7 2007-2013. Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs (LIBE), Directorate General for Internal Policies, Policy Department C: Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs, Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs (PE 509.979).

- Birch, K. and Siemiatycki, M., 2016. Neoliberalism and the geographies of marketization: the entangling of state and markets. Progress in human geography 40 (2), 177–198. doi: 10.1177/0309132515570512

- Borgatti, S.P., 2002. NetDraw software for network visualization. Lexington, KY: Analytic Technologies. Available from: https://sites.google.com/site/netdrawsoftware/home [Accessed 07 Dec 2016].

- Borgatti, S.P. and Everett, M.G., 1997. Network analysis of 2-mode data. Social networks, 19 (3), 243–269. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8733(96)00301-2

- Borgatti, S.P., Everett, M.G., and Freeman, L.C., 2002. Ucinet for windows: software for social network analysis. Harvard, MA: Analytic Technologies. Available from: https://sites.google.com/site/ucinetsoftware/home [Accessed 07 Dec 2016].

- Borgatti, S.P., Everett, M.G., and Johnson, J.C., 2013. Analyzing social networks. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Borgatti, S.P. and Halgin, D.S., 2011. Analyzing affiliation networks. In: J. Scott and P.J. Carrington, eds. The SAGE handbook of social network analysis. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications, 417–433.

- Boulanin, V., 2012. Defence and security industry: which security industry are you speaking about? Paris Papers. 2012 No. 6. Paris: Institut de Recherche Strategique de l’Ecole Militaire (IRSEM).

- Cote-Boucher, K., Infantino, F., and Salter, M.B., 2014. Border security as practice: An agenda for research. Security dialogue 45 (3), 195–208. doi: 10.1177/0967010614533243

- Dekker, D., Krackhardt, D., and Snijders, T.A., 2007. Sensitivity of MRQAP tests to collinearity and autocorrelation conditions. Psychometrika, 72 (4), 563–581. doi: 10.1007/s11336-007-9016-1

- Del Sarto, R.A., and Steindler, C., 2015. Uncertainties at the European Union’s southern borders: actors, policies, and legal frameworks. European security, 24 (3), 369–380. doi: 10.1080/09662839.2015.1028184

- Ecorys Research and Consulting, 2009. Study on the competitiveness of the EU security industry. Framework Contract for Sectoral Competitiveness Studies – ENTR/06/054, Client: Directorate-General Enterprise & Industry Brussels, 15 November.

- European Commission, 2004. Research for a secure Europe: report of the group of personalities in the field of security research. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

- European Commission. 2015. The European agenda on security. Communication from the commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, COM(2015) 185 final, Strasbourg, 28 April.

- Everett, M.G. and Borgatti, S.P., 2013. The dual-projection approach for two-mode networks. Social networks, 35 (2), 204–210. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2012.05.004

- Frost & Sullivan, 2014. Global border and maritime security market assessment. Frost & Sullivan, M965-16 [online]. Available from: http://images.discover.frost.com/Web/FrostSullivan/GlobalBorderandMaritimeSecurity.pdf [Accessed 27 May 2015].

- Frowd, P.M., 2014. The field of border control in Mauritania. Security dialogue, 45 (3), 226–241. doi: 10.1177/0967010614525001

- Gammeltoft-Hansen, T., 2013. The rise of the private border guard: accountability and responsibility in the migration control industry. In: T. Gammeltoft-Hansen and N.N. Sorensen, eds. The migration industry and the commercialization of international migration. Abingdon: Routledge, 128–151.

- Gammeltoft-Hansen, T. and Sorensen, N.N., eds., 2013. The migration industry and the commercialization of international migration. London: Routledge.

- Guiraudon, V. and Lahav, G., 2000. A reappraisal of the state sovereignty debate: The case of migration control. Comparative political studies, 33 (2), 163–195. doi: 10.1177/0010414000033002001

- Guittet, E.-P. and Jeandesboz, J., 2010. Security technologies. In: J.P. Burgess, ed. The Routledge handbook of new security studies. London: Routledge, 229–239.

- Hanneman, R.A. and Riddle, M., 2005. Two-mode networks. Introduction to social network methods [online]. Riverside: University of California. Published in digital form at: http://faculty.ucr.edu/~hanneman/ [Accessed 07 Dec 2016].

- Hayes, B., 2006. Arming big brother: The EU’s security research programme. Amsterdam: Transnational Institute (TNI).

- Hayes, B., 2009. NeoConOpticon: the EU security-industrial complex. Transnational Institute (TNI) in association with Statewatch, 28 September [online]. Available from: http://www.statewatch.org/analyses/neoconopticon-report.pdf [Accessed 07 Dec 2016].

- Heemskerk, E.M., Daolio, F., and Tomassini, M., 2013. The community structure of the European network of interlocking directorates 2005-2010. PloS one, 8 (7): e68581. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068581

- Hills, A., 2006. The rationalities of European border security. European security, 15 (1), 67–88. doi: 10.1080/09662830600776702

- Hoijtink, M., 2014. Capitalizing on emergence: the “new” civil security market in Europe. Security dialogue, 45 (5), 458–475. doi: 10.1177/0967010614544312

- Huber, K., 2015. The European parliament as an actor in EU border policies: its role, relations with other EU institutions, and impact. European security, 24 (3), 420–437. doi: 10.1080/09662839.2015.1028188

- Jones, C., 2016. The visible hand: the European Union’s security industrial policy. Statewatch Analysis, August.

- Knoke, D., 1994. Political networks: the structural perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Knoke, D. and Yang, S., 2008. Social network analysis, second edition. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Krackardt, D., 1987. QAP partialling as a test of spuriousness. Social networks, 9 (2), 171–186. doi: 10.1016/0378-8733(87)90012-8

- Krackhardt, D., 1988. Predicting with networks: nonparametric multiple regression analysis of dyadic data. Social networks, 10 (4), 359–381. doi: 10.1016/0378-8733(88)90004-4

- Kumar, R., forthcoming. Security Inc.: mapping the field of border technologies in the European Union. PhD Dissertation in Politics and International Relations. University of Kent Brussels School of International Studies (BSIS).

- Latapy, M., Magnien, C. and Vecchio, N.D., 2008. Basic notions for the analysis of large two-mode networks. Social networks, 30 (1), 31–48. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2007.04.006

- Leander, A., 2010. Commercial security practices. In: J.P. Burgess, ed. The Routledge handbook of new security studies. London: Routledge, 208–216.

- Lemberg-Pedersen, M., 2013. Private security companies and the European borderscapes. In: T. Gammeltoft-Hansen and N.N. Sorensen, eds. The migration industry and the commercialization of international migration. New York: Routledge, 152–172.

- Léonard, S., 2010. Eu border security and migration into the European Union: FRONTEX and securitisation through practices. European security, 19 (2), 231–254. doi: 10.1080/09662839.2010.526937

- Lindgren, K.-O., 2010. Dyadic regression in the presence of heteroscedasticity – an assessment of alternative approaches. Social networks, 32 (4), 279–289. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2010.04.002

- Mutlu, C.E. and Salter, M.B., 2013. The discursive turn. In: M.B. Salter and C.A. Mutlu, eds. Research methods in critical security studies. London: Routledge, 113–119.

- Prokkola, E.K., 2012. Neoliberalizing border management in Finland and Schengen. Antipode, 45 (5), 1318–1336.

- Rijpma, J. and Vermeulen, M., 2015. Eurosur: saving lives or building borders? European security, 24 (3), 454–472. doi: 10.1080/09662839.2015.1028190

- Scott, J. and Carrington, P.J., 2011. The SAGE handbook of social network analysis. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications.

- SIPRI, 2016. SIPRI yearbook 2016: armaments, disarmament and international security [online]. Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, 8 September. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Available from: https://www.sipri.org/yearbook/2016 [Accessed 07 Dec 2016].

- SIPRI, n.d. SIPRI military expenditure database [online]. Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, SIPRI databases. Available from: https://www.sipri.org/databases/milex [Accessed 07 Dec 2016].

- Soreanu, R. and Simionca, A., 2013. Social network analysis. In: L.J. Shepherd, ed. Critical approaches to security: an introduction to theories and methods. London: Routledge, 181–195.

- Spijkerboer, T., 2007. The human costs of border control. European journal of migration and law, 9 (1), 127–139. doi: 10.1163/138836407X179337

- Stockmarr, L., 2016. Security fairs. In: R. Abrahamsen and A. Leander, eds. Routledge handbook of private security studies. Abingdon: Routledge, 187–196.

- Stovel, K. and Shaw, L., 2012. Brokerage. Annual review of sociology, 38, 139–158. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-081309-150054

- United Nations Office of the Commissioner for Human Rights. 2011. Guiding principles on business and human rights: implementing the United Nations “protect, respect and remedy” framework. Vol. HR/PUB/11/04. New York: United Nations.

- Vernet, A., Kilduff, M. and Salter, A., 2014. The two-pipe problem: analysing and theorizing about 2-mode networks. In: D.J. Brass et al., eds. Contemporary perspectives on organizational social networks. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 337–354.

- Wasserman, S. and Faust, K., 1994. Social network analysis: methods and applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.