ABSTRACT

This article critically examines a poorly understood aspect of the European security landscape: early warning systems (EWSs). EWSs are socio-technical systems designed to detect, analyse, and disseminate knowledge on potential security issues in a wide variety of sectors. We first present an empirical overview of more than 80 EWS in the European Union. We then draw on debates in Critical Security Studies to help us make sense of the role of such systems, tapping into conceptual debates on the construction of security issues as either “threat” or “risk” related. Finally, we study one EWS – the Early Warning and Response System for infectious diseases – to understand how it works and how it reconciles risk – versus threat-based security logics. Contrary to assumptions of a clear distinction between risk- and threat-based logics of security, we show that EWSs may serve as a “transmission belt” for the movement of issues from risk into threats.

In the last decade and ostensibly as a response to a perceived need to effectively respond to crises that cross geographic and functional boundaries – so-called transboundary crises (Boin and Rhinard Citation2008) – the number of information-management platforms for early warning has proliferated in the European Union (EU). These Early Warning Systems (EWSs) are designed to detect, assemble, and disseminate knowledge relating to all kinds of potential dangers to European populations and confirm a broader trend towards anticipation and pre-emption as security in Europe has become “unbound” and subject to few limits (Huysmans Citation2014, on pre-emption, see Aradau and Van Munster Citation2007, Citation2011, Amoore Citation2013). It is most fundamentally this broadening approach to security and risk that has made it a perceived imperative to establish systems at the EU level that try to identify sources of potential dangers and disruptions to European societies.

Since EWS are unexplored in the European security landscape, this article surveys and explores EWS in both quantitative and qualitative terms. Quantitatively, we set out to systematically examine the proliferation of EWS that has taken place in the recent decade in the EU. Our research reveals that in almost every sector of European policy-making, tools have emerged to “horizon scan” for potential problems and to alert when certain trends are perceived as serious. Furthermore, and qualitatively, in order to better understand the phenomenon of early warning in the EU, we explore one of the earliest and most advanced such systems in greater detail: the Early Warning and Response System on public health hazards (EWRS).

The sheer volume of EWS in the EU might lead one to assume that these represent a risk-based approach to security, since they focus on a myriad of potential hazards – and range of systems and objects deemed worth protecting on an everyday basis – rather than a small number of clearly specified threats demanding extraordinary action. This assumption would reinforce the perception that security within the EU is mostly conceptualised in terms of risk rather than threat, following a global trend where “‘risk’ is effectively the new security” (Corry Citation2012, p. 236; and see van Munster Citation2009). To be sure, scholars have increasingly taken an interest in exploring security in terms of risk (e.g. Vedby Rasmussen Citation2004, Aradau et al. Citation2008, Corry Citation2012, Petersen Citation2012, Hammerstad and Boas Citation2015, Judge and Maltby Citation2017). Many scholars have found it heuristically useful to separate threat- and risk-based security practices (e.g. Corry Citation2012, Judge and Maltby Citation2017). However, whereas there is a rich philosophical and sociological discussion on different approaches to risk (e.g. Dillon Citation2008, Petersen Citation2012), less has been said about how these two approaches relate to each other in concrete empirical contexts. To what extent do practitioners themselves ascribe different meanings to threat and risk, and do different constructions of security issues either as risks or as threats enable different policy responses? In general, a risk-based approach to security is often assumed to prevail in bureaucratic environments and professional networks, while a threat-based one is understood as more concentrated among political elites. In this article, we assess the tenability of making such a strict analytical separation, by studying the operation of EWS in closer detail.

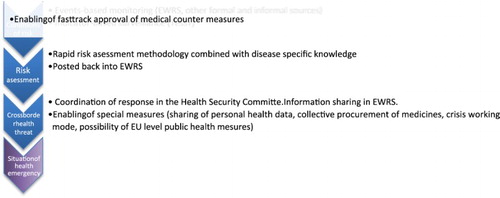

What, we ask, is the nature of the relationship between “risk” and “threat” approaches to security when they are seemingly used interchangeably to identify problems and to devise policy responses? As Felix Ciută emphasises, context is paramount when unravelling articulations of security (Ciută Citation2009). Our context is the growing phenomenon of early warning as a kind of security activity in the EU’s institutional landscape (Boin et al. Citation2014a) along with the specific context of a single system within the sector broadly referred to as health security. We explore whether and how different logics of security – risk-based approaches versus threat-based approaches – manifest themselves in the daily operation of this system and with what effect. We find that in early warning in the domain of health security cooperation, the main focus rests on identifying a wide range of potential public health hazards, in a way that reflects basic assumptions and discourses about risk management and risk mitigation. This changes when one of those hazards becomes identified as a “cross-border health threat”, however, understood as something qualitatively different and more serious than the mere prevalence of risk. A cross-border health threat calls for and enables particular crisis-related forms of policy response. These range from EU-wide declarations of a public health emergency, to fast track approval of medical counter measures and particular internal working modes referred to by officials as “war time”. In sum, a detailed examination of the meaning-making practices generated within and through the EWRS suggests that EWS may operate as mechanisms through which diffuse and omnipresent risks are translated into concrete and tangible threats. When the concepts are used among bureaucrats, to move an issue from a risk to a threat means an “intensification” in terms of its perceived dangerousness that enables extraordinary measures, i.e. a qualitatively different logic of security (cf. Williams Citation2011, p. 216).

After presenting our research design and methods, the first part of the article provides an overview of the number, nature, and growth of early warning in the EU by drawing on a comprehensive collection of systems uncovered by our previous work (described below). We chart the growth of EWS on the European continent and categorise them into sectors. We then review theoretical understandings of risk versus threat logics of security. In particular, we present what is at stake in constructing issues of security as threats or risks, a debate to which we link our findings. In the final part, we present additional empirical findings in case study form. We examine the EWRS on public health hazards in greater detail. The concluding part summarises our findings.

Research design and methods

The inventory of the EU’s EWSs which we present in the article draws on earlier work in the area of the EU’s “sense-making capacities” in crisis management (Boin et al. Citation2014a,Citationb, Backman and Rhinard Citation2017). When compiling the inventory, we searched for systems with social and material components which perform the four functions included in the United Nation’s definition of early warning (see further below). In other words, we searched for systems that engage in monitoring, assembling, and disseminating knowledge on risk and threats, as well as include some aspect of mobilising a response. By a “social component”, we refer to a group of people tasked with the inputting of information pertaining to such activities through these systems. By a “material component”, we refer primarily to information technology tools and physical networks activated for these functions. Our search included the European Commission and General Secretariat of the Council of the EU, as well as the specialised agencies within the EU. The systems are sometimes referred to as “early warning” or “rapid alert systems”, but sometimes they lack a specific name. In order to locate the systems, we used open-source material mostly found online. We also interviewed EU officials (six in total), scholars (two in total), and other experts (three in total) in order to identify systems we may have missed. A list of the systems can be found in the Appendix to this article, with further details on the information collected for each system available online at www.societalsecurity.eu. The full range of EWS is presented first in this article, in order to give the reader the full empirical contours of EWS in the EU in terms of aggregate data.

We then consider EWS against the theoretical backdrop of debates in Critical Security Studies, finding reason to suggest that EWS may play a role in constructing security issues as either risks or threats. To evaluate that idea, we then dive deeper into the empirics, studying a specific EWS – the EWRS, which is used to monitor risk in the health field and is managed by the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). The ECDC is an EU agency linked to the European Commission’s Directorate General for Health and Food Safety (hereafter, DG SANTE). This choice can be justified on several grounds. First, the EWRS was established in 1999 and is one of the oldest EWS in the EU. Second, the system is widely used, with available evidence of its everyday use and operation during health crises. The EWRS is linked to a dense institutional environment established around DG SANTE and the ECDC, for which risk assessment and coordination of risk management constitute core tasks. Officials from these organisations engage with the EWRS as part of their everyday practices, with a considerable higher frequency as compared to other EWS. Nevertheless, even though the EWRS may in some ways be understood as representative of the phenomenon of early warning, the case selection serves not so much for enabling generalisation across other EWS as to cast light on how translations from risk to threat-based logics of security occur within a particular empirical context. The empirical material for this section draws on interviews with officials (approximately 20 in total, from the European Commission, World Health Organization, and ECDC), which were used to gain background information and a general impression of different logics of security. We also scanned and analysed official documents, available online and in paper form following interviews, from all three institutions.

The emergence of early warning in the EU

Defining EWS

EWS are in the extant academic literature frequently discussed in relation to natural disaster management, and a number of international conferences have been held on natural disaster reduction since the late 1990s, where EWS have an important role to play. In the UN’s (Citation2015) global assessment report on disaster risk reduction from 2015, early warning is singled out as the area where most progress has been made (pp. 154–160). While EWS are widely used to designate systems which gather, monitor, analyse, and disseminate knowledge on threats, dangers, and risks, most of the current literature deals with EWS in discreet issue areas, such as, i.a., earthquakes (Gasparini et al. Citation2007); famine (Brown Citation2008); geological disasters (Wenzel and Zschau Citation2014); climate change (Singh and Zommers Citation2014); and flood (Cools et al. Citation2016). Moreover, there is a body of work seeking to evaluate EWS in relation to conflict prevention (e.g. O’Brien Citation2002, Meier Citation2011). As we shall see below, EWS has in recent years rapidly expanded and are to be found in a large number of areas.

Concerned by a lack of common characteristics among different EWS, Waidyanatha (Citation2010, p. 33) has proposed the following definition:

[A] chain of information communication systems comprising sensor, detection, decision, and broker subsystems, in the given order, working in conjunction, forecasting and signalling disturbances adversely affecting the stability of the physical world; and giving sufficient time for the response system to prepare resources and response actions to minimise the impact on the stability of the physical world.

Further unpacking this generic definition, EWS are usually understood to be composed of four components: (1) the monitoring of an environment; (2) the gathering of risk knowledge; (3) the dissemination and communication on various threats; and (4) the building of capabilities that may swiftly be deployed (UNISDR Citation2006). This definition, offered by the UN’s office for disaster risk reduction, is the one we use in order to locate EWS in the EU. Moreover, it may be further refined by turning to Chiara de Franco and Christoph Meyer’s conceptual work on forecasting and warning on transnational risk. Synthesising across policy sectors, de Franco and Meyer (Citation2012) argue that there are four components involved in early warning: (1) forecasting; (2) communicating; (3) learning; and (4) mobilising some kind of action. They define forecasting as “all activities relating to making sense of the future, and here in particular, identifying risks that may affect negatively a given individual, social group, organization or state” (de Franco and Meyer Citation2012, pp. 7–8). Forecasting then has to do with both the gathering of information and the monitoring of an environment. Second, communicating risks “is concerned with the way information, interpretations and opinions about risks and their management are transmitted, discussed, amplified and transformed as they become part of a communication process involving individuals, groups and institutions” (de Franco and Meyer Citation2012, p. 9). Third, learning from warnings is understood as “a cognitive process which aims to put the best available knowledge at the service of decision making” (de Franco and Meyer Citation2012, p. 11). This aspect of early warning is omitted from the UNISDR’s definition. Finally, EWSs are linked to some capacity for mobilising action. This link may look different. Sometimes, it is merely a matter of communicating findings to a decision-making body. At other times, decision-makers may be integrally involved in early warning itself. This last component reminds us that early warning is not isolated from decision-making power. Raising an issue as a potential problem generates attention and response from those with decision-making authority.

EWS in the EU

The EU’s extensive role in early warning can be seen as part of its larger engagement in what is alternatively called “societal security” (Olsen et al. Citation2007), “protection policies” (Rhinard et al. Citation2006), and other activities linked to emergency management, disaster response, and “all-hazards” preparation. These activities are not always neatly organised into organisational and sectoral boxes. In some cases, they are easy to locate. The European Response Coordination Centre contains three 24/7 “situation rooms”, information support systems, and ready-to-mobilise teams for different kinds of crisis events. The Council’s General Secretariat houses the “Integrated Political Crisis Response” arrangements, exercised once a year to simulate a European security crisis requiring the EU to mobilise a common response. Other kinds of activities are harder to localise organisationally. Often, these have accumulated in the form of “flanking measures” associated with European policy projects. Energy grid coordination is designed to enhance economic efficiencies, for instance, but security and safety measures have been created to prevent and prepare for breakdowns. Another example includes European railroad safety provisions, which require member states to report on risk management practices and to alert European authorities regarding impending problems. One study reveals that these kinds of measures in the field of “societal security” or “protection policies” span the spectrum of prevention, preparation, response, and recovery activities traditionally associated with “crisis management” (Boin et al. Citation2013) while another argues that the array of security and safety measures resists investigation because they reside in different venues and institutional locations (Fritzon et al. Citation2007). In any case, EWS are often integral parts of such activities across a range of sectors.

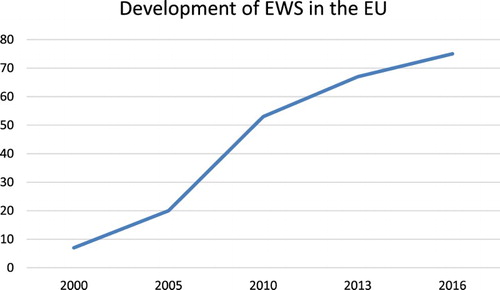

According to our findings, there are more than 80 EWSs at the EU level (see Appendix). Only a few of them have “early warning” in their official names, although other descriptors, as discussed below, leave little to doubt. What is certain, moreover, is that there has been a sharp increase in the creation and development of EWS (see ). These systems are found in almost every EU policy area, from food safety to ash cloud monitoring, and from border control to radiological leaks. Put generally, such systems aim to “horizon scan” for potential problems (either through data processing or member state input), diffusing alerts among EU institutions and agencies and the competent authorities in the member states. Few policy areas are without a specific detection system devoted to them.

Indeed, not only one but a plethora of different systems fall under each Directorate General (DG) of the European Commission. By way of example, several systems across a variety of policy sectors fall under the European Commission’s DG SANTE. The most important DG SANTE systems include: the Animal Disease Notification System; the Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed (RASFF) system for safety of food, food contact material and feed; the EUROPHYT for plant health; the Early Warning Systems (EWRS) for potential “serious cross-border threat to health”; the TRACES system that monitors dangers associated with imports of food, animals, and plants; and systems dealing with chemical, biological, and radio-nuclear threats (RAS-BICHAT) and (RAS-CHEM). The oldest one of those is the RASFF, which since 1979 alerts member state governments in the event of human food or animal feed contamination. A potential outbreak of a food- or feed-born disease is communicated to all member states, operating collectively within the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), the ECDC, and the Commission’s DG SANTE. In addition, EWS systems under other DGs may also touch upon health and safety-related concerns. One such example is the European Radiological Data Exchange Platform, which shares radiological monitoring data among EU member states via the Commission’s DG for Mobility and Transport (DG MOVE), in order to spot any early radiological leaking that may require acute action from national governments to protect citizens.

The systems of course also differ widely. Some may be seen as rather simple platforms of exchange between member states, while other systems are more complicated and carry out independent processing and assembling of data. As an example, Tariqa 3 is an EWS developed by the European External Action Service (EEAS), and consumes enormous amounts of open-source data to assist policy-makers in identifying likely “hotspots” or impending conflict zones around the world. It seeks to integrate news databases, social media data, Google trends, and live TV and radio broadcasts from 40 satellite channels. Its operators conduct interviews with EEAS desk officers to pinpoint geographical foci and then draw data together to assist in early identification of potential problems perceived as requiring a European response. Tariqa 3 operators pride themselves in being able to identify “weak signals” in terms of impending threats. In contrast, the Consular Cooperation On-Line system, also under the EEAS, is less technical. It links consular services across the EU member states as a hub for information exchange and cooperation before and during acute events, seen as requiring information exchange about consular protection of European citizens abroad. Foreign ministries, representatives in different EU diplomatic representations (EU and national delegations), and officials from the EEAS feed information into the system regarding what potential conflagrations may demand consular support and cooperation among EU consular services (European Union Citation2015).

In general, systems are particularly pronounced in areas that experienced recent attacks or events that turned into emergencies. Warning systems for energy crises – namely gas and oil – have been put in place. Following the Icelandic Ash Cloud, Eurocontrol’sFootnote1 Pilot In-Flight Reports system collects real-time information about ash cloud positions and concentrations. Potential cyber- and terrorist-attacks – the detection focus de jour – are now monitored by no less than two systems each, started in 2015. Even in the area of food policy, where multiple EWS already exist, a new IT-tool (Administrative Assistance and Cooperation System) was set up in 2015 for the very specific purpose of alerts on cases of “food fraud” following the so-called horsemeat crisis when it was discovered that horsemeat had been placed at the market as beef products.

Looking across all the systems presented in the Appendix, a few notable features emerge. First, the systems cover a wide range of policy fields from civil protection, health, border management to nuclear security, critical infrastructure, and law enforcement. Second, the policy areas with most systems include health, civil protection, and border management. Third, all systems gather information, which is done partly through Member State input, and partly through the EU’s own devices; almost all communicate information back to the Member States; and about 50% of them provide their own analysis of the gathered information. Fourth, and most relevant for our purposes here, the systems address both specific, immediate issues (e.g. oil spills, bombings) and general conditions of risk (e.g. radicalisation, health hazards). The language describing the operation of the systems tend to use the “risk” language and “threat” language alongside one another, without clear distinction or explanation of why this is the case. Furthermore, traditional security issues (e.g. territorial conflict) are scanned alongside issues generally conceived as part of the “new” security agenda (e.g. extreme weather, poverty). In short, an initial empirical review of early warning in the EU hints at risk- and security-based logics existing side-by-side and even used interchangeably. To understand what this may mean in broader theoretical perspective, and with what implications for outcomes, we now turn to the literature.

Theorising EWS

Implicitly, the proliferation of EWS is often understood as a functional response to an environment increasingly filled with risks, threats, and dangers. As de Franco and Meyer point out, to some observers EWS epitomise the victory of scientific expertise over political power (de Franco and Meyer Citation2012, p. 2). EWS, in other words, are understood as apolitical in terms of both inception and consequence. In policy communities and among EU member states, the set-up of such a system is often seen as a purely technical and non-contentious form of cooperation at expert level. In this article, we will instead understand EWS as co-constitutive of the environment that they allegedly merely monitor. By trying to make sense of the world, they enable policies and responses to issues constructed as “risky” or “threatening”. In other words, instead of understanding the EWS as simply monitoring a pre-existing environment, we examine how the practices nested in such systems generate inter-subjectively shared understandings of risks and threats. Understood as such, these systems contribute to making sense of what it means to be secure in Europe. Thus, like William Walters and Jens Henrik Haahr (Citation2005), we understand practices of early warning as partaking in the “governmentalisation” of Europe (p. 10). They are part of the construction of Europe as a particular space for attempting to govern a future characterised by contingency, unpredictability, and unknowability. However, we do not make any assessments as to the general “effectiveness” of the EWS in doing so. Although EWS are clearly about attempting to govern, understandings of their “success” of doing so is an altogether different matter.

Threats and risks

More specifically, we argue that the rise of systems for early warning speaks to the conceptual debate on constructions of security issues as either threats or risks. Waever (Citation1995) famously described securitisation as a “speech act”, focusing on the discursive construction of danger by political elites. The original securitisation approach argued that securitisation takes place when select hazards are successfully constructed as existential threats to a particular referent object, requiring exceptional responses taken outside of the realm of normal democratic policy processes (Buzan et al. Citation1998). This, the approach posited, involves high levels of political attention and the mobilisation of special (emergency) procedures and resources. Others, however, while acknowledging the value of securitisation theory, have questioned the focus on exceptionalism in the original formulation of securitisation theory and instead highlighted that “securitization works through everyday technologies, through the effects of power that are continuous rather than exceptional, through political struggles, and especially through institutional competition within the professional security field in which the most trivial interests are at stake” (Bigo Citation2002, p. 73). Jef Huysmans’s (Citation2006) work has also emphasised the character of security discourse as “a technological and bureaucratic capacity of structuring social relations through the implementation of specific technological devices in the context of specific governmental programmes” (p. 9). Particularly in the context of the EU, Didier Bigo and Huysman’s emphasis on the mundane rather than on exceptionalist nature of securitisation in Europe has been repeatedly confirmed.

This shift in the debate has helped to kindle approaches that emphasise “risk” rather than stark “threats” in the various logics driving the pursuit of security. Indeed, in the last decade, the concept of risk has received considerable attention in security scholarship (e.g. Aradau et al. Citation2008, Petersen Citation2012, Hammerstad and Boas Citation2015). As Hammerstad and Boas (Citation2015) note, the question “is not whether ‘risk’ is replacing security, but whether ‘risk’ is becoming an increasingly central and accepted component of contemporary conceptualisations of security” (p. 477). For scholarship drawing on Foucault’s understanding of governmentality, risk is usually conceptualised as “a technology or practice that disciplines behaviour through … calculation” (Petersen Citation2012, p. 700). Within IR, such an understanding has been taken up by a group of scholars engaging in what Karen Lund Petersen has referred to as “critical risk studies” (Petersen Citation2012). This literature emerged as a response to attempts by Western governments to wage a ubiquitous “war on terrorism” through risk analysis (e.g. Amoore and de Goede Citation2005, Aradau and van Munster Citation2007, de Goede Citation2008). For instance, risk management has been used to separate “trusted travellers” from suspect ones with biometric technologies, thus displacing risk onto already vulnerable groups (Amoore and de Goede Citation2005).

Research on risk constructions of security dovetails with another emphasis in critically oriented security studies: anticipatory governance. Authors show that in Europe and North America in particular, security approaches are oriented towards a hypothetical (“risky”) future (e.g. Amoore and De Goede Citation2008, Adey and Anderson Citation2012). Security practices, such as those seen in the EU’s EWSs, reflect a drive towards pre-emption, understood by Marieke de Goede et al. (Citation2014) as “security practices that aim to act on threats that are unknown and recognised to be unknowable, yet deemed potentially catastrophic, requiring security intervention at the earliest possible stage” (p. 411; and see Aradau and Van Munster Citation2007, Citation2011).

Granted that risk thinking is on the rise, why does it matter? Claudia Aradau, Luis Lobo-Guerrero, and Rens van Munster have argued that it is important to distinguish between risk-based and threat-based approaches to security, since they differ both in terms of what policy prescriptions follow and the security technologies that are employed as a response:

Whereas [threat-based approaches to security] emphasize agency and intent between conflicting parties, risk-based interpretations tend to emphasize systemic characteristics, such as populations at risk of disease or environmental hazard. Moreover, threat-based interpretations rely on intelligence in an attempt to eliminate danger, while risk relies on actuarial-like data, modelling and speculations that do not simply call for the elimination of risk but develop strategies to embrace it. (Aradau et al. Citation2008, p. 148)

Figure 2. Threat-based versus risk-based perspectives on security. Adopted from Aradau et al. (Citation2008, pp. 148, 151), and Corry (Citation2012, pp. 246, 247).

Scholars have started to examine the difference that it may make whether issues are constructed as issues of threats or risks in a variety of empirical contexts. In some fields, security discourses do not follow neat theoretical models. For instance, Andrew Neal argues on the one hand that risk assessment and management rather than securitisation is characteristic of the work of Frontex. At the same time, migration is still sometimes discursively constructed in terms of threats (Neal Citation2009). Anne Hammersted and Ingrid Boas have examined the British National Security Strategy, and found that even though the concept of risk plays a more prominent part, it has not replaced threat-based security. Most importantly, a risk-based approach to security has enabled the inclusion of environmental hazards into the British security agenda. Thus, constructions of security in terms of risk have tended to broaden the British security agenda. Andrew Judge and Tomas Malby have argued the energy security may be discursively constructed either in terms of threat or risk (Judge and Malby Citation2017). Specifically, they show that the Polish government tends to view energy policy in terms of threat, largely conforming to securitisation. The British government, on the other hand, tend to perceive energy security in terms of risk. Such conflicting articulations of energy security has made it difficult for the European Commission to forge a common European position on energy security.

For the most part, however, the connection between risks and threats, and exploration of their interplay, is underexplored in the extant literature. In looking at our empirical data presented in Part 1, we see both risk and threat logics at play. Indeed, from a critical risk studies perspective, it could be tempting to see the proliferation of EWS at the EU level as a manifestation of a riskification of security in the EU (Corry Citation2012). However, we will demonstrate that both risk- and threat-based logics are present and interconnected in a specific way. When examined in detail, it becomes clear that it is not possible to say that a certain system always takes a risk- or a threat-based perspective on security. The unfeasibility of classifying the systems in such a way is also illustrated by the fact that a plethora of terms are used for the scope of the systems (“hazards”, “threats”, “risks”, “crises”, “extreme events”, “disasters” and “emergencies”), can vary, and are terms that are given different meanings in different policy sectors. Instead, we propose that EWS should be seen as systems where conditions of risk are made sense of in ways that sometimes allow for translation into a more traditional threat-based logic. As such, these two logics are then not to be seen as incommensurable, but can follow upon one another in a temporally sequential way. Sometimes, however, conditions of risks are determined as simply calling for continued monitoring or mitigation measures according to a risk-based logic of security. At other times, a particular problem may shift from being constructed as a risk towards something requiring a different logic, approach, and reaction, namely a threat. Since such dynamics are always to be understood in their context, we examine one EWS in greater detail in order to better illustrate how risk is made sense of in ways that sometimes elevates certain events to a threat-based logic.

Examining risk and threat-based logics of security through the EWRS

To explore the possible relationship between risk- and threat-based logics to security, we now draw out one EWS for closer scrutiny. We ask here how practitioners themselves understand and treat the distinction between risks and threats, and with what implications for action. Notably, we show that in the case of the EWRS, horizon-scanning for many different kinds of health problems, and the conditions of risk they entail occasionally gives rise to the designation of a single issue as a “serious cross-border threat to health” – with special implications thereafter. Following a brief overview of the EWRS, we show the process by which the everyday search for multiple risks occasionally gives rise to the prioritisation of a single threat. We then examine the policy and procedural implications of this shift.

The EWRS in brief

The European Warning and Response System for communicable diseases and other threats to health (EWRS) is an IT-tool drawing national public health authorities in EU member states together with the Commission’s DG SANTE and the ECDC. Through the EWRS, its members can share information about events conceived of as having a possible and serious EU-level impact, and begin to coordinate their response. When established through a legal act in 1998 (Decision 2119/98/EC), the EWRS was meant as a rapid alert tool for member states to be managed by DG SANTE. Since 2005, responsibility for administering the EWRS has fallen to the ECDC. In October 2013, new legislation extended the scope of the EWRS from infectious disease to biological and chemical agents, environmental risks, and “threats of unknown origin” (Decision 1082/2013/EU).Footnote2

The EWRS system is accessible on a 24/7 basis, and used by member states or the ECDC through activation of “a case thread”; that is, a notification of a particular problem. Other member states are thus notified, and can share additional information that may be seen as relevant, including any control measures, taken or planned, using that particular “thread”. Each year roughly 90 threads are reported; each contains an average of 500–600 associated messages from other member states or the EU institutions (ECDC Annual Epidemiological Reports Citation2013). Access to the EWRS has opened up over the years to include not only EU member state authorities but also members of the European Economic Area and the European Free Trade Association. Since the entering into force of the WHO International Health Regulations in 2007 and the new legal framework at the EU level from 2013, the operation of the EWRS also works in an increasingly integrated way with its WHO equivalents.

Over the years, the scope of the EWRS has been progressively expanded beyond infectious disease into a so-called all-hazards approach. In fact, the most recent legal revision (Decision 1082/2013/EU) obliges member states to notify any potential threats of biological origin (such as biotoxins or particular strain of antimicrobial resistance), chemical origin (such as intentional or accidental release of toxic chemicals), environmental origin (such as extreme weather events), or, widening the circle considerably: “threats of unknown origin” (pg. L293/6) to the EWRS. This new, wider scope is further captured by the creation of a legal category of a “serious cross-border threat to health”, coined and codified with the 2013 framework. The definition of a “serious cross-border threat to health” in the legislation is:

a life-threatening or otherwise serious hazard to health of biological, chemical, environmental or unknown origin which spreads or entails a significant risk of spreading across the national borders of Member States, and which may necessitate coordination at Union level in order to ensure a high level of human health protection. (p. L293/7)

In essence, what matters for this all-hazards understanding of a threat is not its origin, but its effects.

Moving from risks to threats

As a platform, the EWRS is first of all a way for competent national public health authorities to report any indication of a possible hazardous “event” of cross-border potential. This may include any form of infectious disease or other health hazards, and the information uploaded, while sometimes varying, can include the steps taken at national levels in an epidemiological outbreak investigation (establishing existence, verifying a diagnosis, constructing a working case definition, etc.). The EWRS also links to other systems for the sake of horizon-scanning and “full and complete information”. For instance, the TessY system is another IT-tool used for the reporting of structured (indicator-based) surveillance data on listed infectious diseases at the EU level. Member states are required by law to report into TessY on a regular basis the level of, for example, Tuberculosis prevalence in the national population, according to certain indicators and shared case definitions. If an unexpected surge of Tuberculosis is detected in a certain group when such TessY data is assembled, this could be considered relevant for the epidemic intelligence officers and eventually fed back to the EWRS as a thread.

The content of EWRS notifications (together with other sources of information, such as internet scanning tools) are scrutinised at a daily “roundtable” meeting of the Surveillance and Response Unit and its epidemic intelligence team at the ECDC. This team of epidemic intelligence officers operates at a rotating weekly basis, on what can be intense shifts. Each day the epidemic intelligence team presents to the roundtable what the current detected events of concern are. If an event is considered sufficiently serious by the roundtable participants, a “rapid risk assessment” is produced drawing on disease specific expertise, particular methodologies, as well as other sources of information. The purpose of this process is a narrowing of focus from a wide range of events to a more limited focus on those that are deemed to be potentially serious and transboundary, thus meriting an EU-level risk assessment and coordinated action.

Indeed, it appears somewhat as a chain-like process, through which events are identified through the EWRS (drawing on a broad number of fora and systems), analysed, and when situations are deemed particularly serious, prioritised (see ).

As shown above, the first step in this process is normally the events-based monitoring carried out by the ECDC on a daily basis, drawing both on EWRS notifications and other unstructured (e.g. ad hoc, open-source) sources of information (Paquet et al. Citation2006). If an event is considered serious, it is then signalled by the epidemic intelligence team to the roundtable, which may decide to carry out a rapid risk assessment. Such risk assessments are different from the longer, more substantial ones carried out by the EFSA, for instance, before a new food additive can be placed on the market. Rather, a rapid risk assessment is conducted in a matter of days according to particular methodologies through which uncertainty has to be weighed against the perceived urgency to provide the member states with a preliminary assessment of the situation. If the rapid risk assessment concludes that there is a low level of risk, the chain of events stops here – and is not elevated to a threat-based security logic.

Sometimes, however, the results of the rapid risk assessments are found by the ECDC risk assessors as of more serious concern. Such events are thus alerted and brought up for discussion at a higher level, and it is around this stage in the process that conditions of risk or potentially risky events are translated into something similar to a threat-based logic of security. The forum for coordination in relation to such phenomena is the so-called Health Security Committee, which brings together designated high-level representatives from the member states and is chaired by DG SANTE. Established by the Council after the anthrax attacks in the U.S. in 2001 (i.e. a “bioterrorism” attack), this body was later formalised and brought under the European Commission as an advisory group following the 2013 reform (Decision 1082/2013/EU). The Health Security Committee also contains sub-networks, such as one for risk communication, which are meant to further streamline member state action during major crises. Although the Health Security Committee is ultimately the most important forum through which shared understandings of the nature of a particular “health threat” are shaped, the related EWRS threads and the readiness of the ECDC staff to provide additional risk assessments are active shapers of discussion within the Committee (Santos-O’Connor et al. Citation2014).

The logic of a “serious cross-border threat to health” is different from a merely risk-based logic of security in several aspects. Most importantly, it differs in terms of the perceived severity, urgency, and cross-border nature of the problem, in contrast to a situation concerning just prevalence of risk. Moreover, if a health threat does not originate in an outbreak of communicable disease or spread of pathogens but in intentional release, different control measures can be seen as required and need to be prepared for in cooperation with other sectors. Many experts also understand “serious cross-border threats to health” not only as mere health concerns to be watched, but as crises that can disrupt other fundamental societal functions. In general, the notion of “serious cross-border threat to health” therefore also calls for all-hazards preparation for the unknown through “generic preparedness” i.e. build-up of capacity for crisis management and response that can be implemented across sectors in dynamic ways. Finally, another way in which the conceptualisation of a “serious cross-border threats to health” differs from a risk-based logic of security is that it enables certain kinds of emergency measures and working modes that are outlined in the following sections below.

The EWRS should not be seen as serving merely as a platform of notifications. Once a rapid risk assessment is produced by the ECDC, it is also posted back to the EWRS in order for the member states to draw on this assessment for their own risk management. Member states are then also expected to report to the EWRS which such measures are taken at the national level. The EWRS is thus both a source of information that might be picked up for the EU-level risk assessment, as well as an IT-tool through which both ECDC risk assessments and national control measures can be shared. On some occasions, the ECDC can also carry out scientific assessment of the effectiveness of certain measures (such as vaccination), which are then distributed back to member states. In sum, the EWRS can be seen as a platform that, in sifting through a wide range of potential health problems in a process of designating what is deemed a “serious threat”, is also bridging the divide that some health policy experts believe is important to maintain – the separation of risk assessment from risk management.

What happens when a risk is turned into a threat?

The process of elevating a risk to a threat is a constructed process, of course, by which a certain set of knowledge claims are used to shape and reshape how issues are viewed and managed. There are material, practical indications of this process taking shape, too, in the form of a notification to the Health Security Committee, upon which high-level officials are expected to act upon an urgent and “serious threat”. Another is the triggering of an action reserved only for exceptional circumstances: the right of the Commission to proclaim a “situation of public health emergency” (European Union Citation2013, p. L293/11). Previously, this capacity at the international level was only held by the WHO, but since the reform in 2013, this option is also available for the EU addressing specifically the European rather than global context. The audience of such a proclamation should be seen as the general European public as well as national and supranational institutions, and just like in the WHO case it serves as a general warning but also a call to collectively mobilise a response in the event of a particularly “serious cross-border threat to health”. This designation, provided for in the most recent legal framework of 2013, is similar to a classic speech act in the Copenhagen School sense (but at the point of writing has yet to be used formally by the Commission). As shall be seen below, the proclamation of a “situation of public health emergency” in the EU can be used to enable exceptional measures relating to the EU-level authorisation of pharmaceutical products. However, other exceptional measures can also be mobilised for “serious cross-border threats to health”, without the triggering of the formal emergency proclamation. Both kinds of mechanisms and their corresponding measures are outlined below.

A “serious cross-border threat to health” can on some occasions enable the adoption of “common temporary public health measures” at the EU level to complement member state action. According to the legal framework, such a situation arises only when coordination of national response is deemed insufficient, and “where the protection of the health of the population of the Union as a whole is jeopardised” (European Commission Citation2011). Even though the enabling of such measures does not require a formal EU declaration of a “public health emergency”, the possibility of implementing response measures at the EU level can nevertheless be considered extraordinary, since it effectively implies a suspension of the normal division of competences between the EU and the member states in terms of risk assessment and risk management. It is thus an exception to the normally very limited legal mandate of the EU in public health.

Another extraordinary measure beyond the “normal” legal regime also comes into view when a serious threat is designated: the possibility for member states to collectively procure vaccines and medical counter measures. The idea that member states should be able to order pharmaceutical products as a group rather than separately gained strength after the H1N1 pandemic in 2009, when some member states resorted to stockpiling against the interests of their European neighbours. The 2013 legislation previously mentioned included a provision which allows for collective procurement of medicines on behalf of a group of member states in emergency situations. This legal innovation went beyond the EU legal framework and required the signing of an inter-governmental “collective procurement agreement” between the member states who chose to participate in this form of enhanced cooperation together with the Commission (European Commission Citation2014). Now that this new arrangement for inter-state cooperation has entered into force, it allows member states to go beyond the existing legal framework and collectively procure large amounts of pharmaceutical products in the event of a serious cross-border threat to health.

Another effect of the move from risk to threat is the binding of member states to particular obligations relating to cooperation and information sharing more generally. Member states are not only obliged to coordinate their national public health measures such as control or contact tracing measures, but are also required to exchange sometimes sensitive information about the health of individuals (both confirmed or suspected cases) (p. L 293/12). Rules relating to data protection at the EU level limit the scope of such exchange, and the data are protected through a function in the EWRS restricting exchange only to those member states involved in contact tracing (p. L 293/12).

In the event of a proclamation of a “public health emergency” by the European Commission, further measures are made available. Such measures include a fast track market authorisation by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) of medicinal products for emergency situations (EC No 507/2006, EC No 1234/2008). This sidestepping of EU pharmaceutical legislation can be done even if the WHO level has not yet proclaimed a “public health emergency of international concern”. It implies a process where the safety requirements of vaccines or counter measures are weighed against the perceived urgency to protect the EU population (European Commission Citation2011). During the 2009 H1N1 “swine flu” pandemic, the Commission coordinated such a procedure, allowing pharmaceutical companies to quickly place several vaccines on the market in the EU (European Commission Citation2017). At the time, however, a shortened emergency procedure still relied on an WHO emergency declaration (in particular, since it related to an influenza pandemic, the EU had to wait for the WHO to raise its assessment to “pandemic level 6”) (European Medicines Agency Citation2011). As with the other measures described so far, this provision contributes to the construction of a European space of security distinguished from both the national level as well as the overlapping global regime of the WHO.

Apart from the provisions above, the logic of a “serious cross-border threat to health” also comes with the designation of particular internal working modes in both the ECDC and the European Commission. At the Commission’s DG SANTE, this emergency working mode involves the use of crisis facilities and particular management structures, referred to as the Health Emergencies Operations Facility (HEOF) (European Commission Citation2007). As an example, during the H1N1 pandemic, this internal working mode was active 24/7, including weekends and bank holidays, in order to produce updates on the epidemiological situation as well as to coordinate response measures and information to the European public. These activities were channelled and coordinated both via the EWRS focal points in the member states as well as the member state representatives in the Health Security Committee. The Health Emergency and Diseases Information System information tool was also activated in order to provide the member states with a comprehensive overview of news, scientific advice, maps, communications material, and a log book with all actions taken so far to tackle the pandemic.

In the ECDC, the corresponding emergency working mode is referred to as entry into a “Public Health Event”, which comes in two levels (PHE1 and PHE2). The idea of this working mode is similar but not identical to the HEOF at the level of DG SANTE. The entry into such a mode in the ECDC can be intense and is referred to internally in the organisation as “war time”. Just like in the Commission, the agency adopts a different organisational set-up centred around the physical structures of its Emergency Operations Room (EOC). During this working mode, the EOC serves as a hub both for human resources mobilised as well as for the technical systems used to support monitoring, rapid risk assessment, and information sharing. A particular management structure is launched, by which a “Public Health Manager” is designated in order to be in charge of a team of staff with particular roles on a rotating basis. All ECDC staff receive compulsory “PHE training” and are encouraged to familiarise with the structures of the EOC also in “peace time”, as a constant preparation for potential future “serious cross-border threat to health”.

Conclusion

This article has identified and explored a new and rapidly proliferating phenomenon in European security: EWSs. We identified over 80 such systems involved in monitoring, gathering, making sense of, and disseminating knowledge on potential dangers in almost every sector of EU policy-making. In general, such systems have been understood by practitioner communities as apolitical, technocratic responses to a natural need to monitor an increasingly risky external environment. However, scholarship in Critical Security Studies, as reviewed in the second section of this article, reminds us that security constructions are neither inevitable nor innocent. In this article, in addition to exploring the phenomenon of early warning in the EU, we contributed to the debate on if and how it matters whether security issues are constructed as threats or risks. The main conclusion to come out of our study is that it does indeed matter: when issues are moved from mere risks to concrete threats, different measures are legitimated. Intriguingly, EU bureaucrats themselves understand risk and threat-based logics of security in fairly similar terms as the literature suggests. The distinction between threat and risk therefore should not be seen as for instance belonging to different actors or levels of the political system (cf. van Munster Citation2009).

Close examination of the EWRS for infectious diseases confirms the co-existence of two kinds of security logic: one in which the focus rests on the surveillance and management of a broad range of potential problems, framed by the grammar and logic of “risk” management as outlined by Corry (Citation2012); the other which emphasises the extraordinary nature of a select few hazards, requiring exceptional measures and attention that connotes more traditional notions of “threat” and related processes of securitisation. These two logics are revealed in both official descriptions and everyday operation of the system, during which, at cursory glance, the two seem to intermingle. Further study of the EWRS, however, allows us to see that there is, indeed, a “logic” to the relationship of the logics. The relationship might be described as sequential. The EWRS is engaged in the everyday search for risks, pooling together different kinds of potential problems gathered using different sources, on a daily basis. Those problems are regularly reviewed and analysed by officials. Occasionally, officials choose to elevate some of those risks into threats requiring extraordinary action. This dynamic seems akin to a transmission belt by which a pool of risks is narrowed down into select number of threats. While the two logics behind the construction of security issues clearly differ, as proposed by much of the literature, we can show here that they are inter-related in a clear and consistent way. Further research is needed to see whether other EWS in the EU system work as “transmission belts” in a similar manner, and if they do so in sectors of a different nature; for instance, do the findings of our health security-related EWS also apply to understandings of risk and threats in the fields of counter-terrorism or cyber security in the EU? Our theoretical apparatus was constructed in such a way that we should expect no significant differences between issues areas. To repeat our expectation, EWS engage in rigorous scanning for any-and-all potential risks in a specific sector, before elevating some problems into “threats” requiring concerted EU action. That expectation is generic enough to expect similar findings across issue areas, but future research could usefully evaluate that question.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the useful feedback and helpful criticism offered by Federica Bicci, J. Peter Burgess, Tom Lundborg, Karen Lund Petersen, Mark Salter, Karen Smith, and Dan Öberg, and two autonomous reviewers, all of which helped to improve the quality of this article. We are grateful to Sarah Backman and Ylva Pettersson, who both provided excellent research assistance. Any errors or shortcomings are the responsibility of the authors alone.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Louise Bengtsson is a PhD Candidate in International Relations in the Department of Economic History at Stockholm University. Her research addresses security logics in European and international public health policies.

Stefan Borg is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow in International Relations at the Department of Economic History, Stockholm University. His research area is located at the intersection of European security, border politics, and contemporary rights claiming. His work has recently appeared in Review of International Studies, Journal of Common Market Studies, and Journal of International Political Theory.

Mark Rhinard is a Professor at Stockholm University and Senior Research Fellow at the Swedish Institute of International Affairs. He earned his MPhil and PhD degrees from Cambridge University. His latest research on internal security was published in Theorising Internal Security Cooperation in the European Union (2016, Oxford University Press).

Notes

1 Although not formally an EU agency, Eurocontrol has been delegated parts of the implementation of EU airspace policy.

2 The EWRS has since then been linked to other rapid alert systems such as those for food safety and chemicals, in order to rapidly generate information on a wide range of events. The EWRS is also increasingly integrated with the IT system for systematic, ongoing collection of structured (i.e. indicator-based) public health data (TessY) (Santos-O’Connor et al. Citation2014, p. 48).

References

- Adey, P. and Anderson, B., 2012. Anticipating emergencies: technologies of preparedness and the matter of security. Security dialogue, 43 (2), 99–117. doi: 10.1177/0967010612438432

- Amoore, L., 2013. The politics of possibility. Risk and security beyond probability. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Amoore, L. and de Goede, M., 2005. Government, risk, and dataveillence in the war on terror. Crime, law, and social change, 43 (2), 149–173. doi: 10.1007/s10611-005-1717-8

- Amoore, L. and de Goede, M., eds., 2008. Risk and the war on terror. London: Routledge.

- Aradau, C. and Van Munster, R., 2007. Governing terrorism through risk: taking precautions, (un)knowing the future. European journal of international relations, 13 (1), 89–115. doi: 10.1177/1354066107074290

- Aradau, C. and Van Munster, R., 2011. Politics of catastrophe: genealogies of the unknown. London: Routledge.

- Aradau, C., Lobo-Guerrero, L., and Van Munster, R., 2008. Security, technologies of risk, and the political, guest editors’ introduction. Security dialogue, 39 (2–3), 147–154. doi: 10.1177/0967010608089159

- Backman, S. and Rhinard, M., 2017. The European Union's capacities for managing crises. Journal of contingencies and crisis management, Published 24 Aug 2017 (Early View). doi:10.1111/1468-5973.12190

- Bigo, D., 2002. Security and immigration: toward a critique of the governmentality of unease. Alternatives: global, local, political, 27 (1), 63–92. doi: 10.1177/03043754020270S105

- Boin, A. and Rhinard, M., 2008. Managing transboundary crises: what role for the European Union? International studies review, 10 (1), 1–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2486.2008.00745.x

- Boin, A., Ekengren, M., and Rhinard, M., 2013. The European Union as crisis manager: problems and prospects. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Boin, A., Ekengren, M., and Rhinard, M., 2014a. Making sense of sense-making: the EU’s role in collecting, analysing, and disseminating information in times of crisis. Stockholm: Swedish National Defence College, Acta B Series No. 44.

- Boin, A., Ekengren, M., and Rhinard, M., 2014b. Sensemaking in crises: what role for the European Union? In: P. Pawlak and and A. Ricci, eds. Crisis rooms: towards a global network? Paris: European Union Institute for Security Studies (EU-ISS), pp. 118–128.

- Brown, M., 2008. Famine early warning systems and remote sensing data. Berlin: Springer.

- Buzan, B., Wæver, O., and de Wilde, J., 1998. Security: a new framework for analysis. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner.

- Ciuta, F., 2009. Security and the problem of context: a hermeneutical critique of securitisation theory. Review of international studies, 35 (2), 301–326. doi: 10.1017/S0260210509008535

- Cools, J., Innocenti, D., and O’Brien, S., 2016. Lessons from flood early warning systems. Environmental science and policy, 58, 117–122. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2016.01.006

- Corry, O., 2012. Securitisation and “riskification”: second-order security and the politics of climate change. Millennium: journal of international studies, 40 (2), 235–258. doi: 10.1177/0305829811419444

- de Goede, M., 2008. The politics of preemption and the war on terror in Europe. European journal of international relations, 14 (1), 161–185. doi: 10.1177/1354066107087764

- de Goede, M., Simon, S., and Hoijtink, M., 2014. Performing pre-emption. Security dialogue, 45 (5), 411–422. doi: 10.1177/0967010614543585

- Dillon M., 2008. Underwriting security. Security dialogue, 39 (2–3), 309–332. doi: 10.1177/0967010608088780

- ECDC annual epidemiological report, reporting on 2011 surveillance data and 2012 epidemic intelligence data in 2013, 2013. Available from: http://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/annual-epidemiological-report-2013.pdf [Accessed 13 May 2016].

- European Commission, 2007. The commission health emergency operations facility: for a coordinated management of public health emergency at EU level. Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/health/ph_threats/com/preparedness/docs/HEOF_en.pdf [Accessed 17 August 2015].

- European Commission, 2011. Q&A: health security in the EU. Available from: http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-11-884_en.htm [Accessed 15 August 2015].

- European Commission, 2014. Joint procurement agreement: considerations on the legal basis and the legal nature of the joint procurement agreement. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/preparedness_response/docs/jpa_legal_nature_en.pdf [Accessed 10 June 2017].

- European Commission, 2017. Pandemic influenza (H1N1). Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/health/communicable_diseases/diseases/influenza/h1n1_en#fragment4 [Accessed 10 June 2017].

- European Medicines Agency, 2011. Pandemic report and lessons learned outcome of the European medicines agency’s activities during the 2009 (H1N1) flu pandemic. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Report/2011/04/WC500105820.pdf [Accessed 10 June 2017].

- European Union, 2013. Decision No 1082/2013/EU of the European parliament and of the council of 22 October 2013 on serious cross-border threats to health and repealing Decision No 2119/98/EC, OJ L L293/1; November 5.

- European Union, 2015. Council Directive (EU) 2015/637 of 20 April 2015 on the coordination and cooperation measures to facilitate consular protection for unrepresented citizens of the Union in third countries and repealing Decision 95/553/EC, OJ L 106; April 24.

- de Franco, C. and Meyer, C., eds., 2012. Forecasting, warning and responding to transnational risks. London: Palgrave.

- Fritzon, Å., Ljungkvist, K., Boin, A., and Rhinard, M., 2007. Protecting Europe’s critical infrastructures: problems and prospects. Journal of contingencies and crisis management, 15 (1), 30–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5973.2007.00502.x

- Gasparini, P., Gaetano, M., and Zschau, J., 2007. Earthquake early warning systems. Berlin: Springer.

- Hammerstad, A. and Boas, I., 2015. National security risks? Uncertainty, austerity and other logics of risk in the UK government’s national security strategy. Cooperation and conflict, 50 (4), 475–491. doi: 10.1177/0010836714558637

- Huysmans, J., 2006. The politics of insecurity. Fear, migration and asylum in the EU. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Huysmans, J., 2014. Security unbound. Enacting democratic limits. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Judge, A. and Maltby, T., 2017. European energy union? Caught between securitisation and “riskification”. European journal of international security, 2 (2), 179–202. doi: 10.1017/eis.2017.3

- Meier, P., 2011. Early warning systems and the prevention of violent conflict. In: D. Stauffacher, B. weekes, U. Gasser, C. Maclay, and M. Best, eds. Peacebuilding in the information age: sifting hype from reality. Geneva: ICT4Peace Foundation, 12–15.

- Neal, A. 2009. Securitization and risk at the EU border: the origins of FRONTEX. JCMS: journal of common market studies, 47 (2), 333–356.

- O’Brien, S., 2002. Anticipating the good, the bad, and the ugly. An early warning approach to conflict and instability analysis. Journal of conflict resolution, 46 (6), 791–811. doi: 10.1177/002200202237929

- Olsen, O.E., Kruke, B.I., and Hovden, J., 2007. Societal safety: concept, borders and dilemmas. Journal of contingencies and crisis management, 15 (2), 69–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5973.2007.00509.x

- Paquet, C., et al., 2006. Epidemic intelligence: a new framework for strengthening disease surveillance in Europe. Euro surveillance : European communicable disease bulletin, 11 (12), 212–214.

- Petersen, K., 2012. Risk analysis – a field within security studies? European journal of international relations, 18 (4), 693–717. doi: 10.1177/1354066111409770

- Rhinard, M., Ekengren, M., and Boin, A., 2006. The European Union’s emerging protection space: next steps for research and practice. Journal of European integration, 28 (5), 511–527. doi: 10.1080/07036330600979821

- Santos-O’Connor, F., Pukkila, J., and Varela-Santos, C., 2014. The health security framework in Europe. In: B. Rechel and M. McKee, eds. Facets of public health in Europe. New York: Open University Press, 43–69.

- Singh, A. and Zommers, Z., eds., 2014. Reducing disaster: early warning systems for climate change. Berlin: Springer.

- United Nations, 2006. International strategy for disaster reduction. Platform for the promotion of early warning. Bonn. Available from: http://www.unisdr.org/2006/ppew/whats-ew/basics-ew.htm [Accessed 20 May 2017].

- United Nations, 2015. The global assessment report on disaster risk reduction. Available from: http://www.preventionweb.net/english/hyogo/gar/2015/en/home/GAR_2015/GAR_2015_6.html [Accessed 20 May 2017].

- van Munster, R., 2009. Securitizing immigration. The politics of risk in the EU. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Vedby Rasmussen, M., 2004. “It sounds like a riddle”: security studies, the war on terror and risk. Millennium: journal of international studies, 33 (2), 381–395. doi: 10.1177/03058298040330020601

- Wæver, O., 1995. Securitization and desecuritization. In: R. Lipschutz, ed. On security. New York: Columbia University Press, 46–86.

- Waidyanatha, N., 2010. Towards a typology of integrated functional early warning systems. International journal of critical infrastructures, 6 (1), 31–51. doi: 10.1504/IJCIS.2010.029575

- Walters, W. and Haahr, J.H., 2005. Governing Europe: discourse, governmentality and European integration. London: Routledge.

- Wenzel, F. and Zschau, J., eds., 2014. Early warning for geological disasters scientific methods and current practice. Berlin: Springer.

- Williams, M.C., 2011. The continuing evolution of securitization theory. In: T. Balzacq, ed. Securitization theory: how security problems emerge and dissolve. London: Routledge, 212–222.