ABSTRACT

In February 2020, French president Emmanuel Macron invited all interested European states to a “strategic dialogue” on the supposed contribution of France’s nuclear arsenal to European collective security. While certain media commentators relayed Macron’s intervention with approbation and excitement, framing the proposal as an exciting new idea that, if implemented, might boost Europe’s clout on the world stage, the dominant reaction was one of ennui. After all, the argument for Euro-nukes is far from new. In fact, several (mostly French) actors have unsuccessfully attempted to persuade European policymakers of the necessity of European nuclear weapons cooperation for more than half a century. In this article, we investigate the history, merits, and longevity of the case for European nuclear arms. Drawing on secondary literature, policymakers’ writings, and two hitherto untapped surveys of European public opinion conducted by one of the authors, we argue that the case for Euro-nukes is critically flawed with respect to security, strategic autonomy, futurity, and democratic good governance. We maintain that the continuous resurfacing of the “zombie” case for Euro-nukes is made possible by powerful organisational interests, as well as conceptual reversification resulting in enduring contradictions between nuclear vulnerabilities and claims of protection and autonomy.

1. Introduction

“At a time when the global challenges our planet is facing should demand renewed cooperation and solidarity”, claimed the French president in February 2020, “we are witnessing an accelerated disintegration of our international legal order and institutions that structure peaceful relations between States” (Macron Citation2020a). Addressing the École de Guerre in Paris, Emmanuel Macron outlined his vision for the role of nuclear weapons in French and European security. On the one hand, the president maintained that France’s nuclear arsenal remained the bequest of the French people, and that the potential use of the force de dissuasion nucléaire should be narrowly limited to “extreme circumstances of self-defence”. On the other hand, he invited all interested European states to a “strategic dialogue” about “the role played by France’s nuclear deterrence” in the collective security of the European family of states. It was time for Europe to develop greater “autonomy”, opined Macron (see Sauer Citation2020).

The French president’s invitation to a European “strategic dialogue” on nuclear deterrence comes in the context of a marked increase in the political salience of French nuclear weapons, both within France and internationally. First, the costly modernisation of the French nuclear force has raised questions about public spending priorities and the necessity of a nuclear dyad (e.g. Le Point Citation2018). Second, the adoption and entry into force of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) have highlighted global opposition to the practice of nuclear deterrence and increased the pressure on French policymakers to honour France’s nuclear disarmament obligations (Sauer and Reveraert Citation2018). Third, deepening transatlantic fissures, accentuated by US president Donald Trump’s repeated admonitions of NATO, have fuelled arguments for increased European defence cooperation in general and Franco-German defence cooperation more specifically (Kunz Citation2020). With the United Kingdom having completed its formal exit from the European Union (EU), France is now the Union’s only nuclear-armed member.

Macron’s overture was widely reported in European media as a new and original initiative – a proposal for “a more coordinated European Union defence strategy, with France and its nuclear arsenal to play a central role” (Gaubert Citation2020. See also e.g. Rose Citation2020, Wiegel and Gutschker Citation2020). However, similar proposals have in fact been tabled by French leaders over a period of more than half a century. And while the idea of a European nuclear force has occasionally attracted cautious interest from a handful of non-French analysts and governments, its detractors have always far outnumbered its supporters. So far, there have been few if any official responses to Macron’s invitation. Historically, the only time that the notion of a French-led European nuclear deterrence arrangement was subject to public debate at the highest level of the EU, it was “roundly rejected” by the member states’ foreign ministers as an unfounded and even “awful” idea (Goldsmith Citation1995). And yet the Euro-nuke debate continues to reappear at irregular intervals, like a zombie that can never be finally put to rest. In this article, we investigate the evolution, flaws, and persistence of the case for European nuclear weapons.

The remainder of this article is divided into four parts. First, we lay out the history of the Euro-nukes idea, tracing it from the 1950s to the 2020s. Second, we assess the case for a Euro-bomb, finding it weak or faulty on key counts. Be it in the form of an independent European nuclear force or a “nuclear sharing” system run by France and possibly the United Kingdom, a Euro-nuke arrangement would not straightforwardly promote the security of Europeans or enhance Europe’s strategic autonomy. Third, we present the results of two novel surveys of European public attitudes to nuclear weapons designed by the Nuclear Knowledges programme at Sciences Po and conclude that the idea of Euro-nukes enjoys little to no support among Europeans. Fourth, we argue that the zombie-like quality of the Euro-nuke debate is a symptom of unresolved incongruities at the heart of nuclear deterrence and global nuclear order. The discursive value of prospective Euro-nukes in debates about other issues, as well as the internal inconsistencies inherent to the case, make it impervious to terminal refutation and allow disparate constituencies to re-use it for their own political purposes. The case for European cooperation on nuclear deterrence has been kept alive largely by think tanks funded by the French government and nuclear-weapon complex.

2. The Euro-bomb idea is dead, long live the Euro-bomb idea

Discussions about European nuclear weapons commenced quickly after the end of the Second World War. With informal contacts and consultations having been initiated already in the early 1950s, negotiations on European nuclear cooperation led in 1957 to the adoption by Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and West Germany of the Euratom Treaty and establishment of the European Atomic Energy Community (see Heuser Citation1997, chap. 6). While visions and motivations varied, certain participants in this process saw the purpose of such a community as the creation of a European bomb. In France, in particular, at least some key policymakers were eager to further the cause of a European nuclear force (see Mallard Citation2014). But the Euratom track would ultimately prove fruitless for the proponents of European nuclear weapons, as a confluence of international developments, institutional blockages, and principled opposition within the European community closed off all pathways to nuclear militarisation. Yet, shortly after the adoption of the Euratom Treaty, the French government opened a second European track by inviting Germany to join in wide-ranging defence cooperation. Italy would also soon be drawn in, resulting in April 1958 to an agreement between France, Germany, and Italy on the joint development and production of weapons. A secret part of the deal stipulated that Germany and Italy, in exchange for funding and scientific support, would gain access to the French nuclear weapons then under development (Moretti Citation2017). However, the nuclear aspect of Franco–German–Italian defence cooperation ground to a halt following the rise to power of Charles de Gaulle, who opposed German access to nuclear weapons, later in 1958.

Nevertheless, in 1963, just three years after the first French test of a nuclear explosive device, the French government mobilised the prospect of European cooperation on nuclear deterrence as a way of countering the US proposal of a NATO multilateral nuclear force (MLF). Following an article in the April 1963 issue of Le Monde Diplomatique by member of the European Parliament Christian de la Malène, key French officials voiced their support for the idea of a French-led Euro-nuke arrangement – Pierre Messmer (minister of the armies) and Alain Peyrefitte (minister of information) in June and Michel Habib-Deloncle (minister of foreign affairs) in September (Malis Citation2005, pp. 681–683). The latter would also tell the Council of Europe that, once Europe’s “political structure” had been strengthened, it would “be necessary to outline how France’s nuclear effort can be utilized by all the European nations for common defense” (cited in Kohl Citation1965, pp. 101–102). A number of commentators, including Jean Monnet in France and Henry Kissinger in the United States, supported the idea (Buchan Citation1963). Kissinger had long been a supporter of nuclear sharing as an antidote to anti-nuclear sentiments and what he saw as European squeamishness about nuclear weapons (Egeland Citation2020a). Yet the political integration of Europe proceeded slowly, and no other European states proved particularly interested in the French proposal. It probably did not aid the French pitch that several French policymakers and strategists, including president de Gaulle himself, had long expressed deep scepticism vis-à-vis the prospect of a country using nuclear weapons to protect anything but its most vital national interests, let alone an ally (Gallois Citation1960, de Gaulle Citation1961, Poirier Citation1976).

The debate lay relatively dormant throughout much of the 1970s, but reappeared in the 1980s. In fact, successive West-German chancellors, Helmut Schmidt and Helmut Kohl, quietly approached French leaders about the issue of nuclear defence (Bozo Citation2020); the so-called Euro-missile crisis had pushed the nuclear predicament onto the top of the political agenda in Europe. In 1982, international relations theorist Hedley Bull published a much-discussed article in which he proposed the development of a “Europeanist” foreign policy involving, inter alia, the creation of a “minimum” European nuclear force (Bull Citation1982). Two years later, the German Christian Democratic Party’s spokesperson on arms control, Jürgen Todenhöfer, publically expressed interest in such an endeavour. Former French president Valéry Giscard d’Estaing reacted quickly. He proclaimed that West Germany was “a target” and should therefore be welcome to take shelter behind France’s nuclear “shield”. The incumbent government of François Mitterrand, however, was slower to respond. By the time Mitterrand had come round to initiating a multilateral dialogue on European nuclear weapons and security, German interest in nuclear deterrence had plummeted as a result of breakthroughs in US–Soviet arms control.

Following the collapse of the Warsaw Pact and, with it, an important justification for French nuclear armament, the Mitterrand government intensified its advocacy for “Europeanising” the French nuclear force. In 1992, Mitterrand argued at a colloquium on European integration that the “compatibility between the French nuclear forces and European defence would have to be addressed” (cited in Jasper and Portela Citation2010, p. 157). A few weeks later, France’s then deputy defence minister, Jacques Mellick, launched the idea of a European “concerted deterrence” arrangement (dissuasion concertée). Per the official justification, such an arrangement would allow France to informally extend a “nuclear umbrella” over other European states. From the French government’s perspective, however, the primary value of “Europeanising” the French nuclear force arguably lay in its potential as a public relations instrument: European endorsement of the French nuclear endeavour would allow France to portray the force de dissuasion nucléaire not as a relic of outdated Cold War exceptionalism, but as a generous contribution to collective European security. Unlike the United Kingdom and the United States, France eschewed the integration of its nuclear forces in NATO’s nuclear sharing arrangements in the 1960s. As a result, Paris lacked the opportunity enjoyed by London and Washington to portray its continued retention and modernisation of its weapons of mass destruction as a selfless implementation of international commitments (see Egeland Citation2020a).Footnote1 Yet, in the early 1990s, few if any European states proved particularly interested in French nuclear deterrence. On the contrary, the proposal was for various reasons rejected by several EU member states. The Mitterrand government accordingly stopped promoting the initiative, contending that “European deterrence could not come about until vital interests converged fully” (Jasper and Portela Citation2010, p. 157).

Coming into power in 1995, the Chirac government overturned some of the key nuclear policies of the previous administration. Perhaps most notably, in the face of worldwide protests, France resumed nuclear testing after a three-year moratorium. The resumption of testing was accompanied by a relaunching of the concept of dissuasion concertée. The former French defence minister, François Léotard, postulated that the new test series represented “the interests of 300 million Europeans […]. It is to a large extent in their name that we are undertaking this difficult exercise” (cited in Croft Citation1996, p. 772). Prefiguring Macron, Chirac maintained that the proposal of Europeanising the French nuclear posture was “not about unilaterally extending our deterrence […] but a gradual process open to those partners who wish to join” (quoted in Jasper and Portela Citation2010, p. 158). If the EU wanted to become an autonomous strategic actor, Chirac argued, it would have to rely explicitly on the French nuclear force. Yet, the proposal was again rebuffed by European leaders as an “unrealistic and ill-advised idea that was proposed largely to deflect criticism of French nuclear testing in the Pacific” (Goldsmith Citation1995). That said, Chirac found a partially receptive partner in Helmut Kohl. In December 1996, the two leaders reached agreement on a Franco-German “strategic concept” involving a dialogue on European nuclear deterrence (Boyer Citation1997, p. 62). However, the dialogue did not amount to much in practice, and was abandoned entirely when the Social Democratic candidate, Gerhard Schröder, replaced Kohl as German chancellor in 1998.

In 2008, the idea of a European nuclear deterrence policy was again promoted by a French president, this time Chirac’s successor, Nicolas Sarkozy. It was “a fact”, Sarkozy averred, that France’s nuclear weapons, by virtue of “their very existence”, provided “a key element in Europe’s security” (cited Jasper and Portela Citation2010, p. 161). Echoing Chirac and foreshadowing Macron, he pledged to engage willing European partners in “an open dialogue on the role of deterrence and its contribution to our common security” (cited Jasper and Portela Citation2010, p. 161). But, as before, few European states seemed interested. In the past, the Germans had been among those least opposed to the idea – occasionally they had even been quite supportive. However, the German coalition government that came into power in 2009 had made nuclear disarmament one of its key foreign policy aims. Over the course of 2009 and 2010, foreign minister Guido Westerwelle spearheaded an initiative to reduce the role of nuclear weapons in German and European security, seeking the removal of the remaining US nuclear weapons deployed to Germany (Egeland Citation2020a). There was thus less interest in the French proposal than perhaps at any time before. The Hollande government, which came into power in 2012, continued to insist that the French nuclear arsenal provided Europe with security, but refrained from renewing the invitation to engage in a European nuclear dialogue (see Hollande Citation2015).

In the most recent iteration of the Euro-nuke debate, supporters have argued that a “Euro-deterrent” would allow Europe or the EU to develop “strategic autonomy”, augment its security as the US security guarantee loses credibility (Marksteiner Citation2017, Drent Citation2018, Rapnouil et al. Citation2018a, Citation2018b, Tertrais Citation2019a), and provide a hedge against future uncertainties (Rapnouil et al. Citation2018b). Opponents have generally taken the position that a Euro-bomb would merely provide Washington with an excuse to disengage from European security affairs altogether (Ischinger Citation2017, Volpe and Kühn Citation2017). On top of this comes longstanding scepticism about the effectiveness, moral justifiability, and democratic legitimacy of nuclear deterrence strategies (see e.g. Lebow Citation2019). On 12 November 2020, President Macron gave a long interview expanding on “strategic autonomy” as a goal for Europe. In this instance, Macron did not mention nuclear weapons, possibly marking the end of the current cycle of Euro-nuke debate (Macron Citation2020b).

3. Weaknesses in the case for Euro-nukes

3.1. Security

The primary argument used by Euro-nuke proponents is that the credibility of the US nuclear security guarantee to Europe is waning and thus in need of replacing or buttressing by a European arrangement (Bandow Citation2017a, Citation2017b). In the words of one commentator, “non-nuclear European states must remain mindful of a reality in which they may not be able to rely on the NATO nuclear deterrent. Given a resurgent Russia and the shifting security landscape at large, Europe cannot afford to be without a plan”; Europe needs a nuclear “insurance policy” (Marksteiner Citation2017). Nuclear deterrence, in this view, “protects” or “shields” Europeans from foreign threats (Besch and Odendahl Citation2018, Rapnouil et al. Citation2018a, Citation2018b, Tertrais Citation2019a).

The argument that Euro-nukes would ensure the security or “protection” of Europeans rests on at least three questionable assumptions. First, there is little evidence that states engaged in nuclear deterrence arrangements are safer or less likely to be involved in wars than others (Bell and Miller Citation2015, Gartzke and Kroenig Citation2016, Lebow Citation2019), let alone that the dangers inherent to a nuclear-armed world are outweighed by the dangers of a nuclear-free one (Pelopidas Citation2015a). It also remains the case that nuclear weapons and related infrastructure would almost certainly be targeted early on in any nuclear conflict, Focusing on the question-begging notions of “deterrence” and “protection”, proponents of the nuclear-peace hypothesis invariably ignore the long history of nuclear luck and close calls – including moments when deterrence failed but without producing nuclear explosions – and the fact that nuclear threat-making has often served to aggravate tensions and animosity (Lebow and Stein Citation1994, Pelopidas Citation2017, Pelopidas Citation2020).

Second, the argument that Europe must replace the decreasingly dependable US nuclear security guarantee with a nuclear deterrence arrangement championed by France and/or the United Kingdom presupposes that the US nuclear security guarantee was credible, effective, and necessary to begin with.Footnote2 However, a range of officials, both in Washington and in US-allied capitals, have in closed meetings and after retirement admitted that, since the acquisition by the Soviet Union of nuclear forces capable of reaching America, the United States’ threat to use nuclear weapons on behalf of its allies is either irresponsible, incredible, or both (Beaufre Citation1965, p. 416, Enthoven and Smith Citation1971, Frydenlund Citation1982, pp. 158–159, Ravenal Citation1988, Leah and Lyon Citation2010, Shultz et al. Citation2011). In one NSC meeting, US president Richard Nixon maintained that “the nuclear umbrella [is] no longer there”. In another, he referred to the NATO nuclear guarantee as “a lot of crap” (cited in Freedman and Michaels Citation2019, p. 466). Former US secretary of defence Robert McNamara (Citation1983, p. 73) argued that the American nuclear security assurance had “lost all credibility as a deterrent to Soviet conventional aggression”. Kissinger (Citation1981, p. 240) averred that the United States’ pledge to use nuclear weapons on behalf of European states was “absurd” and “cannot be true”:

Therefore, I would say – which I might not say in office – the European allies should not keep asking us to multiply strategic assurances that we cannot possibly mean, or, if we do mean, we would not want to execute, because if we execute we risk the destruction of civilization. (Kissinger Citation1981, p. 240)

Third, the case for Euro-nukes rests on the assumption that France (and possibly the United Kingdom) would in fact be capable of effectively practicing extended nuclear deterrence in Europe. Yet any Franco-British nuclear security guarantee would be confronted with the same political hurdles as the American guarantee. To paraphrase General de Gaulle, would a French president really be prepared to sacrifice Paris for Virolahti or Marseilles for Narva? (De Gaulle Citation1961, Poirier Citation1996, p. 311) Within the paradigm of nuclear deterrence theory, it is also widely assumed that extended nuclear deterrence requires the requisite hardware for “escalation dominance” (e.g. Ross Citation2002). In this view, the relative inferiority of the French and UK arsenals vis-à-vis that of Russia (both with respect to size and flexibility of options) would more than offset the argument that France and the United Kingdom might be more resolved to use nuclear weapon in defence of European non-nuclear states than “a more distant protector” such as the United States (Tertrais Citation2019a, p. 60). Successive US administrations and most nuclear strategists have at any rate maintained that the practice of extended nuclear deterrence obliges the security patron to retain a significantly larger and more diverse nuclear arsenal than a nuclear-armed state concerned only with its own security (e.g. Perry et al. Citation2009, p. 8). It could also be argued that increased resolve would require a more unified European identity and strategic culture, including public support for the use of nuclear weapons. As discussed below, the latter requirement appears to be lacking. More generally, it should be noted that the overall credibility of any European defence posture will rest heavily on conventional response capacity, particularly in Eastern Europe.

3.2. Autonomy

The second main argument used by proponents of Euro-nukes is the contention that a Euro-nuke arrangement would provide Europe or the EU with “strategic autonomy”. According to one set of commentators, “Europeans can no longer pretend that their declared ambition of ‘strategic autonomy’ is more than an empty phrase unless they engage seriously on the nuclear dimension” (Rapnouil et al. Citation2018b, p. 2). As long as European states rely on the nuclear security guarantee of the United States, in this view, Europe will be unable to develop a robust, independent foreign policy. Desire for agency is understandable. Presumably, “strategic autonomy” would imply the ability to withstand attempts at intimidation or coercion while pursuing independently articulated strategic goals. Independent nuclear capabilities, one might hypothesise, would allow Europe to blackmail non-nuclear actors and/or resist attempts at coercion by other nuclear-armed actors. Yet there is little if any evidence that nuclear weapons provide their possessors with coercive advantage (Sechser and Fuhrmann Citation2017, Gavin Citation2018, p. 84). Contrary to much speculation in security studies, history offers few examples of successful nuclear blackmail. Accordingly, absent empirical corroboration, blanket statements that Europe requires nuclear weapons to develop strategic autonomy will remain unpersuasive.

3.3. Futurity

A third argument used by Euro-nuke advocates is that European nuclear weapons would offer a “hedge against the uncertainties of the future” (Rapnouil Citation2018b, p. 12). Indeed, since the end of the Cold War, the United States and European nuclear powers have largely justified their retention of nuclear weapons as a means of protecting themselves and their allies against unforeseeable, prospective threats that might materialise in the future (Egeland Citation2020b). Yet uncertainty does not in and of itself constitute an argument in favour of nuclear weapons. On the contrary, many conceivable and indeed likely scenarios exist in which possessing nuclear weapons would be a liability rather than an asset.

First, ongoing and future technological developments could further reduce the controllability of nuclear deterrence and escalation. Trends that appear to point in this direction include revolutions in military and dual-use technologies, the development of new cyber capabilities that increase nuclear vulnerabilities and uncertainty, increasing entanglement of nuclear and non-nuclear weapon systems, and the introduction of social media nuclear signalling and deep-fake videos (Burford Citation2019, Sechser et al. Citation2019, Acton Citation2020). As pointed out by Unal and Lewis (Citation2018, p. 2): “Many of the assumptions on which current nuclear strategies are based pre-date the current widespread use of digital technology”.

Second, there is broad consensus that ongoing global warming and environmental destruction will have profound implications for food security, economic production, and social and political relations across Europe and the world (see e.g. World Economic Forum Citation2020). These disruptions could increase resource scarcity and thereby upend the cost–benefit calculations underpinning the case for European nuclear arms. A future of runaway global heating would likely see enormous demand for measures to soften the blow of climate change, including welfare schemes, job conversion efforts, comprehensive systems to mitigate forest fires, floods, storms, and other extreme weather events, as well as procedures to tackle pandemics and other disruptive events that might become more frequent as human pressures on the natural world increases (Vidal Citation2020). At a minimum, existing nuclear bases in France and the United Kingdom are likely to be affected by sea level rise, increasing the cost of retaining nuclear weapons in a world where financial resources will be sorely needed elsewhere. Admittedly, it is possible that increased resource scarcity could also be used as an argument in favour of offsetting reduced conventional military expenditure through reliance on “cheap” Euro-nukes. Such claims would rest on the assumption that these weapons are indeed effective instruments of security and autonomy, contrary to what we established above.

In conclusion, for all its supporters’ appeals to the supposed timeless axioms and logic of nuclear deterrence theory, the case for European nuclear weapons seems closely wedded to a presentist vision of the future (see Pelopidas Citation2016). It also appears unfit to address either of the key strategic challenges identified in the 2016 European Union Global Strategy: “terrorism, hybrid threats, economic volatility, climate change and energy insecurity” (European Union Citation2016, p. 9. See Jasper and Portela Citation2010, pp. 162–163).

4. Democracy

Perhaps surprising given the highly influential narrative of Europe as a bastion of democratic norms and values (Nicolaïdis and Howse Citation2002), contributors to the Euro-nuke debate have been curiously inattentive to democratic norms and public opinion. Nuclear deterrence is commonly presented as cheap and politically convenient, as nuclear arms supposedly provide a guarantee of security at little financial and political expense to citizens. However, nuclear weapons have been conceptualised by some as inherently “despotic” due to their speed and destructiveness, the authoritarian command and control procedures through which they are governed, and the inescapable reliance of nuclear deterrence on threats against civilian populations that have not consented to being targeted (Deudney Citation2008, pp. 255–256. On the tension between nuclear deterrence credibility and leaders’ duty to tell the truth, see Cooke and Futter Citation2018). Moreover, the common framing misses at least three profound commitments that are demanded of citizens of nuclear-armed states: First, citizens are called on to fund the production and maintenance of nuclear weapons through taxes. Second, citizens are obliged to tacitly accept that their country will become a target in case of a broader nuclear conflict. And third, citizens are expected to offer tacit support for the potential implementation of a policy that would lead to the indiscriminate killing of large numbers of civilians and potentially cause lasting climatic, ecological, humanitarian, and social disruptions.

Below, we find that European publics do not support these fundamental requirements. But before turning to the question of public opinion, it is worth pointing out the ways in which the issue of democracy is obscured or bypassed in the expert literature. First, a range of authors simply brush aside the views of the public as irrelevant or simply ignore the question of democratic support altogether (see e.g. Bandow Citation2017a, Citation2017b, Wimmer Citation2018, Vicente Citation2019). This mode of inattention is not unique to the Euro-nuke debate, but characteristic of nuclear discourse and scholarship more broadly (Pelopidas Citation2016). Second, some commentators proceed from the assumption that ordinary people lack the knowledge or capacity to determine nuclear policy issues and suggest that policymakers should therefore either ignore the public or deliberately proceed in secrecy. For example, one supporter of European nuclear sharing advises that “any productive discussion about scenarios and options to reinforce deterrence in Europe will have to be quiet and discreet” (Tertrais Citation2019a, pp. 56–57). In fact, there is no need to consult the public as long as any new activities are carried out “within the bounds of current international law and practice” (Tertrais Citation2019a, p. 47). Lastly, some observers insist that European public opinion is muddied or in fact favourable to the creation of a European nuclear force (see e.g. Mey Citation2001, Tertrais Citation2019b).

This latter claim is occasionally supported by misleading polls and figures. For example, a November 2019 poll carried out by the German Körber Foundation found significant support for a Euro-nuke arrangement among the German population. Unsurprisingly, the poll was widely circulated by Euro-nuke proponents in social and print media (e.g. Tertrais Citation2019b, Wiegel and Gutschker Citation2020). The only trouble was that the poll was based on deep methodological fallacies and, as a result, was highly misleading. Introduced to respondents with the leading assertion that the US nuclear umbrella currently “plays a crucial role for German security”, the poll obliged respondents to pick one of four options: they would either (A) “seek nuclear protection from France and the UK”, (B) “continue to rely on the US”, (C) “forego nuclear protection”, or (D) have Germany “develop its own nuclear weapons”. Unsurprisingly, large numbers of respondents opted to retain “protection”: 40% selected option (A), 22% selected option (B), 31% selected option (C), and 7% selected option (D). As we show below, this poll paints a skewed picture of German attitudes to nuclear deterrence. Not only did the Körber poll fail to provide a broad enough menu of policy options for respondents to choose from (as well as artificially forcing them to pick only one alternative), it primed the respondents by establishing that Germans are “protected” by nuclear weapons. New survey data presented below (the 2018 VULPAN and 2019 NUCLEAR surveysFootnote4) suggest that the Germans themselves do not agree with this assumption.

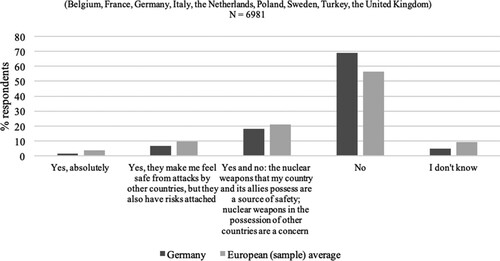

When asked whether nuclear weapons made them feel safe, a majority of German respondents to the VULPAN and NUCLEAR surveys answered with an unqualified “No” (see numbers from the NUCLEAR survey in ).Footnote5 These results are consistent with answers to similar questions, suggesting that respondents’ attitudes are consistent. For instance, 80% of German respondents reporting that nuclear weapons do not make them feel safe believe that the possession of nuclear weapons makes a country less secure. Similar attitudes were found in all countries surveyed (Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Sweden, Turkey, and the United Kingdom). These results are broadly consistent with the findings of a 2020 Munich Security Conference poll (Citation2020, p. 127), which suggested that only 31% of German citizens support nuclear deterrence (66% rejecting any role for nuclear weapons in Germany’s defence). Admittedly, within those 31%, a large majority favoured reliance on the French and UK nuclear arsenals.

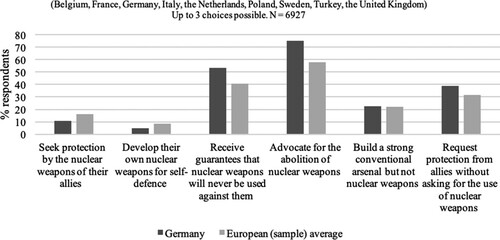

Another methodological fallacy exemplified by the Körber poll is that of not providing respondents with a broad enough menu of options. According to the NUCLEAR survey of November 2019, European and German citizens strongly prefer non-nuclear security policies (see ). In fact, of the six policy choices provided in the NUCLEAR survey, the two nuclear options were the least favoured. In the survey, only 5% of German respondents opined that it would be a good idea for states without nuclear weapons to “develop their own nuclear weapons for self-defence” and only 10% that they should seek “protection by the nuclear weapons of their allies”. 39% of German respondents suggested to “request protection from allies without asking for the use of nuclear weapons”, 22% to “build a strong conventional arsenal but not nuclear weapons”, and 53% to receive negative security assurances (i.e. invite nuclear-armed states to declare that they will never use their nuclear arms against non-nuclear-weapon states). By far the largest share of German respondents (75%) recommend to “advocate for the abolition of nuclear weapons”.

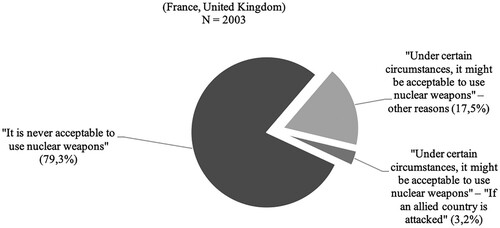

Overall, in the NUCLEAR survey, a majority of respondents expressed opposition to the basic requirements of the practice of nuclear deterrence. In France, as many as 85% of respondents expressed agreement with the notion that “It is never acceptable to use nuclear weapons” and only 15% with the notion that “Under certain circumstances, it might be acceptable to use nuclear weapons”. In the United Kingdom, the corresponding percentages were 73 and 27 (see ). Even more damning for the democratic case for Euro-nukes, of the respondents who opined that it might indeed be acceptable to use nuclear weapons under certain circumstances, only 16% selected “If an allied country is attacked” as a valid condition for the employment of nuclear arms. All told, only 3% of French and UK respondents expressed that it might be acceptable to use nuclear weapons in response to an attack against an ally. Further, the results of the NUCLEAR survey indicate that both French and UK citizens are sceptical of the use of scarce public resources on nuclear-weapon systems for their own supposed defence. In France, 51% of respondents expressed that they “somewhat” or “strongly” disagree with the statement that “I support the use of the taxes I pay to fund the maintenance of the country’s nuclear weapons even if it means less money for other policies”. Only 20.6% expressed that they “somewhat” or “strongly” agreed, with the rest reporting no opinion. In the UK, the corresponding percentages were 46 and 24.

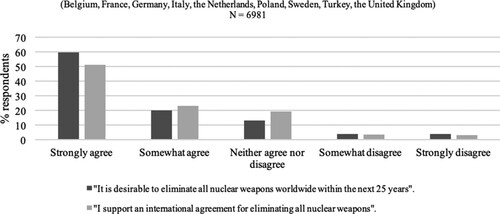

On the question of acceptance of nuclear vulnerability, European publics express opposition to the requirements of nuclear deterrence. When asked about whether “It is acceptable for this country’s residents to be targets of a nuclear attack from other countries if this is part of the country or the ally’s deterrence policy”, a large proportion of Europeans express disagreement. Across the five states hosting US nuclear weapons, an average of 56.6% of respondents to the NUCLEAR survey expressed that they “strongly” or “somewhat” disagreed, 17.9% expressed that they “strongly” or “somewhat” agreed, and 25.4% expressed no opinion. Across France and the United Kingdom, an average of 49.4% expressed that they “strongly” or “somewhat” disagreed, 19.1% expressed that they “strongly” or “somewhat” agreed, and 30.9% expressed no opinion. When asked about their agreement or disagreement with the statement “The possibility of an accident is so catastrophic that nothing makes nuclear weapons justifiable”, 80.6% of respondents across the nine European states sampled “strongly” or “somewhat” agreed. When asked about their agreement or disagreement with the statement “The possibility of an accident is acceptable if the possession of nuclear weapons protects my country from being attacked with nuclear weapons”, 65% of all respondents sampled “strongly” or “somewhat” disagreed. Lastly, European publics express overwhelming support for the goal of complete nuclear disarmament (see ) (see Pelopidas and Egeland Citation2020). Across the nine countries surveyed, enormous majorities of people support an international agreement to abolish nuclear weapons and express that it would be desirable to eliminate nuclear weapons within the next 25 years. The German population is particularly supportive of abolition. Of the German respondents, 88.4% somewhat or strongly agree that it would be desirable to eliminate nuclear weapons worldwide within the next 25 years.

The absence of popular support is a major weakness of the case for Euro-nukes. The publics in France, the United Kingdom, and hosts of US nuclear weapons are far from supportive of the fundamental requirements of the practice of (European) nuclear deterrence, including the use of taxpayers’ money to fund the arsenal, the material vulnerability associated with becoming potential counterforce targets of other states’ nuclear weapons, and the legitimacy of using nuclear weapons under any circumstances – let alone to defend another country.

5. Why the Euro-nuke proposal refuses to go away

As discussed above, the case for Euro-nukes suffers from serious flaws and weaknesses. It has never attracted widespread support among European governments. So why does it keep resurfacing? We suggest that the persistence of the Euro-nuke debate owes to two main factors. First, the case for European nuclear weapons is couched in a discourse plagued by fundamental contradictions and conceptual “reversification”. Second, the case for Euro-nukes is artificially kept afloat by politicised discourse about nuclear non-proliferation and military spending as well as think tanks funded by the French government and companies involved in the production of nuclear weapon systems.

5.1. Contradictions and reversification as rhetorical resources

As the more general debate on nuclear deterrence, the Euro-nuke debate is couched in a series of internal contradictions and inconsistencies. Analysts of the French case for Euro-nukes noted internal contradictions in the argument already the 1960s: The French proposal “contained an inherent contradiction, since the Gaullist idea of a confederal Europe of cooperating, but not integrated states is hardly compatible with the kind of centralized European political authority required to make use of European nuclear armament” (Kohl Citation1971, pp. 283–284. See also Heuser Citation1997, pp. 152–156).Footnote6 Normally, of course, internal contradictions would constitute a liability for those seeking to make a political case. However, in the case of Euro-nukes, contradictions are frequently turned into assets. As one cannot rebuke both sides of a contradiction at once, supporters of Euro-nukes can always rely on whichever side of the contradiction has not been undermined to revive their case. For example, French proponents of Euro-nukes constantly veer between two mutually exclusive positions, the first being that a French-led Euro-nuke arrangement would be compatible with full French sovereignty over its force de dissuasion nucléaire and the second being that Euro-nukes would give Europe or the EU increased agency and autonomy vis-à-vis other actors, thus implying a transfer of nuclear sovereignty from Paris to Brussels or Berlin.

A further obstacle to terminal refutation is “reversification”. Through reversification, the specialised meaning of a term becomes the opposite of its everyday or original meaning, creating an extra layer of confusion and apparent complexity. This phenomenon has been well documented in the realm of finance. For example,

A “bailout” is slopping water over the side of a boat. It has been reversified so that it means an injection of public money into a failing institution. Even at the most basic level, there is a reversal – taking something dangerous out turns into putting something vital in – “Credit” has been reversified: it means debt. “Inflation” means money being worth less. (Lanchester Citation2014, p. 30)

A first reversed concept in nuclear discourse is “protection”. As discussed above, nuclear deterrence practices are invariably justified as means of “protecting” or “shielding” the population. Yet since the introduction of nuclear-armed ballistic missiles in the late 1950s, and especially since the emergence of ballistic-missile submarines in the 1960s, “protection” against nuclear attacks in the conventional sense of the term has become impossible. Despite the allocation of vast resources to the development of missile defence over a period of several decades, interception of long-range missiles remains virtually impossible at any appreciable scale. It has also been acknowledged that civil defence efforts would prove ineffective, and that any medical or humanitarian response capacity would be inadequate in the case of a nuclear attack (Schroeder Citation2018, Geist Citation2019, p. 244). The French practice of nuclear deterrence, then, relies not on “protection” but on valuing the mutual inability to protect as a supposed condition for security. When facing an adversary with a large enough nuclear arsenal to engage in counterforce targeting, this “protection” immediately makes you higher on the target list of this adversary. The metaphors of a nuclear “umbrella” or “shield” – presenting nuclear weapons as protective screens – are in this view deeply flawed. A third common metaphor for extended nuclear deterrence, that of the “insurance policy”, also displays reversification. While insurance policies accept the possibility and likelihood of losses and exist to compensate them ex post facto, the public justification for nuclear deterrence, as the “shield” and “umbrella” metaphors suggest, is to defend against and prevent losses ex ante. If nuclear war were to happen, there would be no compensation beyond the losses inflicted upon the adversary in revenge (see McDermott et al. Citation2017).

Another reversed concept in Euro-nuke debate is “autonomy”. As laid out above, Euro-nuke proponents often suggest that a European nuclear force will lend Europe autonomy and clout on the world stage. However, much like the concept of “protection”, the term “autonomy” is used to describe what is effectively the reverse of what it means in regular parlance. After all, if autonomy is understood as sovereign agency to decide the fate of your citizens, the practice of mutual deterrence produces the very opposite of autonomy, namely an extreme form of dependency. To wit, any nuclear deterrence relation turns on what has been referred to as a system of reciprocal hostage holding (Lee Citation1985); in a situation of mutual nuclear deterrence, both parties exist at their adversary’s mercy.

5.2. Vested interests, think tanks, and incantation

In both Europe and America, think-tank analysts play a crucial role in raising and sustaining the Euro-nuke argument. In many cases, the relevant think tanks are funded by nuclear-armed states and nuclear defence contractors with material and/or political interests in the nuclear enterprise (see Walt Citation1987, p. 157). For example, one of the most involved think tanks – the French Foundation for Strategic Research (FRS) – is funded by the French Ministry of Defence, the French Atomic Energy Commission (CEA), and a range of companies involved in the production and maintenance of (French) nuclear-weapon systems, including Thales, MBDA, Airbus, Safran, and Dassault Aviation (FRS Citation1992, Citation2019, Boncourt et al. Citation2020, pp. 145–148). Another think tank that helps sustain the argument for Euro-nukes is the European Council on Foreign Relations, which receives funding from many of the same sources, including the French Ministry of Defence, the French CEA, and missile manufacturers Airbus and Thales (ECFR Citation2019). Another is the London-based Centre for European Reform, which receives funding from BAE Systems, Lockheed Martin, and Boeing (CER Citation2020).

For the French national security establishment, European nuclear dialogue and/or sharing is seen as a means by which France might legitimise its nuclear arsenal and cultivate “the emergence of a common European strategic culture” in its own image (Tertrais Citation2019a, p. 47). Eager to resist calls for disarmament and the potential isolation of France as the only European possessor of weapons of mass destruction, high-level French policymakers have sought to further a new strategic narrative by marrying the notion of European nuclear deterrence with ideas of a European community of values. “By rendering French nuclear weapons an essential constituent of the defence posture of ‘civilian power Europe’”, the French rhetoric grants nuclear weapons “additional moral justification and legitimacy as ‘weapons of the good’” (Jasper and Portela Citation2010, p. 161).

In Germany, one of the most prominent supporters of the Euro-nuke proposal is the German Council on Foreign Relations (DGAP), which receives funding from Lockheed Martin and Airbus (DGAP Citation2019a, Citation2019b). Analysing the German case, Tristan Volpe and Ulrich Kühn (Citation2017, p. 8) find that the most recent iteration of the debate about German nuclear armament and Euro-nukes has been raised by a small group of pundits, scholars, journalists, and a single member of the German Bundestag. The magnitude of public German attention to this small group’s nuclear musings, they argue, “has no recent historical precedent in the country”. The nature of the topic, in particular given German history, draws media organisations to the story. According to Volpe and Kühn, German proponents of independent or European nuclear weapons are well aware that their arguments are unlikely to be persuasive in the short term, but nevertheless continue to raise the argument in order to habituate the German public to pro-nuclear language. The discussion about nuclear armament “is not primarily intended to garner traction among government officials – at least not now. Rather, as [Bundestag member] Kiesewetter admitted, it is a longer educational effort to remove ‘thought taboos’ held by ordinary Germans about assessing nuclear policy issues” (Volpe and Kühn Citation2017, p. 9).

The dynamics of global nuclear politics and expertise also regularly provide incentives to invoke the Euro-nuke idea – and thereby give it attention and oxygen – for vicarious reasons. For example, proponents of decreased US defence spending occasionally present the idea of a European nuclear force as a welcome means by which the United States could disengage from European security affairs and thereby reduce its military expenditure (e.g. Bandow Citation2017a, Citation2017b). By contrast, in the non-proliferation literature, the Euro-nuke debate is frequently invoked to substantiate the theory that the global nuclear order is just about to collapse or, more specifically, that the non-proliferation regime will break down if the United States fails to perpetuate a large nuclear arsenal and provide its allies with robust nuclear assurances (Payne Citation2017, p. 15, Lanoszka Citation2018, Credi Citation2019, p. 6). US nuclear security guarantees, in this view, have allowed a range of countries to forego independent (or regionalised) nuclear armament. While the empirical accuracy of this narrative may be disputed (Pelopidas Citation2015b), it is routinely deployed for a range of political purposes, such as arguing for increased spending on nuclear weapons in the United States, to make particular US presidential administrations look incompetent, or to justify the continued deployment and modernisation of US nuclear weapons deployed in Europe (Pelopidas Citation2015b, Egeland Citation2020a). In this way, what is in reality a fringe proposal is artificially sustained and amplified due to its rhetorical value in other debates.

6. Conclusion

Overall, the ceaseless reappearance of the proposal for European nuclear weapons over seven decades is puzzling. In this article, we have first established that the current case is defective on all fronts: in terms of security, autonomy, consistency with its imagined futures, and democracy. While there does appear to be support among European publics for increased defence cooperation in general (Shilde et al. Citation2019), such support does not extend to the nuclear domain. We have argued that the consistent re-emergence of the case for Euro-nukes is a result of enduring contradictions, conceptual reversification, rhetorical incantation by vested interests, and the rhetorical value of prospective Euro-nukes in other debates.

If the phenomenon characterised as “populism” is understood as popular resentment against unfulfilled promises by elites and expressing a desire for recognition and sovereign agency in contemporary politics (Epstein et al. Citation2018, pp. 792–793), the implementation of the case for Euro-nukes would only deepen the decades old “democratic deficit” of the European Union adding on top of it the democratic abyss of nuclear weapons policymaking. That would continue the trend of the parallel rise and reciprocal fuelling of technocracy and populism in Europe (Bickerton Citation2012, pp. 183–190). Therefore, it seems that proponents as well as opponents of Euro-nukes should join forces in assessing one of the fundamental preconditions for a European nuclear force: the existence and possible construction of a political and strategic community, without which any extension of nuclear deterrence pledges would not make sense. In an era of populism, such a community cannot possibly be built on the denial of European publics and continued depolitisation which has characterised nuclear weapons politics so far.

For the future of European strategy and autonomy, citizens and elected officials deserve a discussion in which proposed policies are connected with clear and consistent justifications. Creating the space for such a discussion is the responsibility of scholarship (Pelopidas Citation2016, Citation2020). This requires identifying and exposing nuclear vulnerabilities in their material as well as epistemic dimensions, identifying the constitutive effect of imagined futures on choices available in the present, assessing the levels of knowledge and attitudes of the public vis-à-vis those choices, and articulating a set of consistent justifications for each of those. Practices of reversification and incantation should be fiercely combatted, the effects of conflicts of interest on the production of expert discourse assessed and addressed. This effort calls for a more sustained dialogue between European studies and nuclear studies which so far have operated largely on a basis of mutual neglect. The (re)production, legitimation, and contestation of nuclear vulnerabilities would be a particularly productive locus for this dialogue as they have come into being in parallel with the process of state transformation from “nation state” to “member state” and the attempt at creating a post-national polity. Short of such an effort, we are condemning not only scholars but also citizens and elected officials to be haunted by zombie debates.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Sébastien Philippe, Christian Lequesne, Clara Portela, Fabrício Fialho, Anna Konieczna, Sanne Verschuren, Valerie Arnhold, Thomas Fraise, Florent Parmentier and European Security’s anonymous reviewers for helpful comments and assistance at various stages of the research process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Kjølv Egeland

Dr Kjølv Egeland is Marie Skłodowska-Curie Postdoctoral Fellow and Lecturer in International Security at the Center for International Studies (CERI) at Sciences Po in Paris, affiliated to the Nuclear Knowledges programme focusing on strategic narratives and nuclear weapons politics. His research has appeared in Diplomacy & Statecraft, Global Governance, Survival, and International Affairs. He is a Research Fellow at the Norwegian Academy of International Law (NAIL).

Benoît Pelopidas

Professor Benoît Pelopidas is the founding director of the “Nuclear Knowledges” programme at Sciences Po (CERI) and an affiliate of the Center for International Security and Cooperation (CISAC) at Stanford University. Nuclear Knowledges is the first scholarly research programme in France on the nuclear phenomenon that refuses funding from stakeholders both of the nuclear weapons enterprise and antinuclear activists in order to problematize conflicts of interest and their effect on knowledge production. It offers conceptual innovation and unearths untapped primary sources worldwide to grasp nuclear vulnerabilities and rethink possibilities in the realm of nuclear weapons policies.

Notes

1 In 1974, NATO’s North Atlantic Council agreed that the nuclear forces of France and the United Kingdom were capable of performing a “deterrent role” on behalf of the alliance as a whole (NATO Citation1974). However, France refused to join NATO’s Nuclear Planning Group and retained significant distance to NATO with respect to nuclear policy.

2 It also ignores the “entrapment” of European allies in costly US-led wars in the Middle East and Asia (see Ringsmose Citation2010, Oma and Petersson Citation2019, pp. 105–106).

3 Admittedly, the United States military retained thousands of tactical nuclear weapons in certain European countries, often deploying them close to the border to the Warsaw Pact. It is thus possible that a nuclear explosion could have happened in the absence of political authorisation in Washington. The relevant weapons have long since been withdrawn.

4 The June 2018 “VULPAN” survey was conducted in Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Sweden, Turkey, and the United Kingdom. The samples ranged from N = 753 to N = 1012, combining for a total of 7323 respondents. The respondents were aged from 18 to 50. Each sample was representative of that country’s age group in terms of age and gender. The November 2019 “NUCLEAR” survey was conducted in the same countries, with samples ranging from N = 700 to N = 1003, combining for a total of 6938 respondents. The respondents for this survey were aged above 18. The integrated panel for the 2019 survey was representative in terms of age, gender, socio-professioal category, and geographic location of respondents. The surveys thus include data for the two (West) European nuclear-armed states, the five European hosts of US nuclear weapons, and two additional states (Sweden and Poland). It is possible that a different selection of countries would have yielded somewhat different results. For example, it is usually assumed that states located in Eastern Europe, in close proximity to Russia, are more sceptical of nuclear disarmament than countries located in Western Europe. That said, the data presented here does not support this view. In fact, Polish respondents were on average more supportive of “an international agreement for eliminating all nuclear weapons” (total 83.6% support) than any other population sampled. On the question “It is desirable to eliminate all nuclear weapons worldwide within the next 25 years”, Poland showed the tied third strongest support (with Sweden), behind Germany and Italy (82.4% support). Both surveys were designed by Benoît Pelopidas and Fabrício Fialho, under grant agreements 17-CE39-0001-01 “VULPAN” (ANR) and 759707 “NUCLEAR” (ERC Horizon 2020), respectively. The VULPAN survey was carried out by YouGov and the NUCLEAR survey by IFOP.

5 68% of German respondents to the NUCLEAR survey submitted an unqualified “no” to the question of whether nuclear weapons made them feel safe. In the VULPAN survey, 57% of German respondents submitted “no” (restricting the age range in the NUCLEAR survey to the same as that of the VULPAN survey yields 54% “no”).

6 The Gaullist idea of Europe as an intergovernmental project is clearly visible in de Gaulle’s veto of the 1961 version of the Fouchet plan, backed by the FRG, Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxemburg and Italy that aimed for the creation of a common defence policy.

References

- Acton, J., 2020. Cyber warfare & inadvertent escalation. Dædalus, 149 (2), 133–149.

- Bandow, D., 2017a. Time for a European nuclear deterrent? The National Interest, 13 Jan. Available from: https://nationalinterest.org/feature/time-european-nuclear-deterrent-19053?nopaging=1 [Accessed 12 Dec 2019].

- Bandow, D., 2017b. The case for a European nuke. Foreign Affairs, 27 Mar. Available from: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/europe/2017-03-27/case-european-nuke?cid=int-lea&pgtype=hpg [Accessed 12 Dec 2019].

- Beaufre, A., 1965. The sharing of nuclear responsibilities. International affairs, 41 (3), 411–419.

- Bell, M.S. and Miller, N.L., 2015. Questioning the effect of nuclear weapons on conflict. Journal of conflict resolution, 59 (1), 74–92.

- Besch, S. and Odendahl, C., 2018. The good European? Centre for European Reform, Feb. Available from: https://www.cer.eu/sites/default/files/pbrief_german_agenda_21.2.18.pdf [Accessed 14 Dec 2019].

- Bickerton, C., 2012. European integration: from nation-states to member states. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Boncourt, T., et al., 2020. Que faire des interventions militaires dans le champ académique? 20/21. Revue d’Histoire, 145 (1), 135–150.

- Boyer, Y., 1997. European defense and nuclear deterrence. Asia-Pacific review, 4 (1), 57–68.

- Bozo, F., 2020. The sanctuary and the glacis (part I). Journal of Cold War studies, 22 (3), 119–179.

- Buchan, A., 1963. Partners and allies. Foreign affairs, 41 (4), 621–637.

- Bull, H., 1982. Civilian power Europe: a contradiction in terms? Journal of common market studies, 21 (2), 149–164.

- Burford, L., 2019. A global commission on military nuclear risk. European Leadership Network, 25 June. Available from: https://www.europeanleadershipnetwork.org/commentary/a-risk-driven-approach-to-nuclear-disarmament/ [Accessed 5 June 2020].

- CER (Centre for European Reform), 2020. Corporate donors. Available from: https://www.cer.eu/advisory-board#tabs [Accessed 8 June 2020].

- Cooke, S. and Futter, A., 2018. Democracy versus deterrence. Politics, 38 (4), 500–513.

- Credi, O., 2019. US non-strategic nuclear weapons in Europe. American Security Project. Available from: https://www.americansecurityproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Ref-0226-US-NSNWs-in-Europe.pdf [Accessed 8 June 2020].

- Croft, S., 1996. European integration, nuclear deterrence and Franco-British nuclear cooperation. International affairs, 72 (4), 771–787.

- De Gaulle, C., 1961. Discussion with John F. Kennedy, 31 May, Paris. Available from: https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1961-63v14/d30 [Accessed 17 Nov 2020].

- Deudney, D., 2008. Bounding power. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- DGAP, 2019a. DGAP Jahresbericht 2018/19. Available from: https://dgap.org/sites/default/files/static_page_downloads/dgap_jahresbericht_2018-2019.pdf [Accessed 28 June 2019].

- DGAP, 2019b. An independent DGAP. Available from: https://dgap.org/en/council/patrons [Accessed 28 June 2019].

- Drent, M., 2018. European strategic autonomy. Clingendael Institute, 11 Oct. Available from: https://www.clingendael.org/publication/european-strategic-autonomy-going-it-alone-0 [Accessed 14 Dec 2019].

- ECFR (European Council on Foreign Relations), 2019. Our funding. Available from: https://www.ecfr.eu/about/donors [Accessed 12 Dec 2019].

- Eden, L., 2004. Whole world on fire. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Egeland, K., 2020a. Spreading the burden: how NATO became a “nuclear” alliance. Diplomacy & Statecraft, 31 (1), 143–167.

- Egeland, K., 2020b. Who stole disarmament? History and nostalgia in nuclear abolition discourse. International affairs, 96 (5): 1387–1403.

- Ellsberg, D., 2017. The doomsday machine. London: Bloomsbury.

- Enthoven, A.C. and Smith, K.W., 1971. How much is enough? New York, NY: Harper & Row.

- Epstein, C., Lindemann, T., and Sending, O.J., 2018. Frustrated sovereigns. Review of international studies, 44 (5), 787–804.

- European Union, 2016. European Union global strategy. EU Publications Office. Available from: http://eeas.europa.eu/archives/docs/top_stories/pdf/eugs_review_web.pdf [Accessed 20 Dec 2019].

- Freedman, L. and Michaels, J., 2019. The evolution of nuclear strategy. 4th ed. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- FRS (Fondation pour la Recherche Stratégique), 1992. Statuts. Available from: https://www.frstrategie.org/sites/default/files/documents/frs/presentation//statuts.pdf [Accessed 12 Dec 2019].

- FRS (Fondation pour la Recherche Stratégique), 2019. Presentation. Available from: https://www.frstrategie.org/en/frs/presentation [Accessed 12 Dec 2019].

- Frydenlund, K., 1982. Lille land – hva nå? Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Gallois, P.M., 1960. Stratégie de l’âge nucléaire. Paris: Calmann-Lévy.

- Gartzke, E. and Kroenig, M., 2016. Nukes with numbers. Annual review of political science, 19 (1), 397–412.

- Gaubert, J., 2020. Macron calls for coordinated EU nuclear defence strategy. France 24, 8 Feb. Available from: https://www.france24.com/en/20200207-macron-unveils-nuclear-doctrine-warns-eu-cannot-remain-spectators-in-arms-race [Accessed 10 Feb 2020].

- Gavin, F.J., 2018. Rethinking the bomb. Texas national security review, 2 (1), 74–101.

- Geist, E., 2019. Armageddon insurance. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Goldsmith, C., 1995. EU foreign ministers reject France’s nuclear umbrella. Wall Street Journal, 11 Sep.

- Heuser, B., 1997. NATO, Britain, France and the FRG: nuclear strategies and forces for Europe, 1949–2000. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hollande, F., 2015. Speech by the President on the nuclear deterrent. Istres, 19 Feb. Available from: https://www.francetnp.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/discours_pr_istres_eng.pdf [Accessed 14 Feb 2020].

- Ischinger, W., 2017. How Europe should deal with Trump. Project Syndicate, 15 Feb. Available from: https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/european-security-relations-with-trump-by-wolfgang-ischinger-2017-02?barrier=accesspaylog [Accessed 12 Dec 2019].

- Jasper, U. and Portela, C., 2010. EU defence integration and nuclear weapons. Security dialogue, 41 (2), 145–168.

- Kissinger, H.A., 1981. For the record: selected statements, 1977–1980. Boston, MA: Little, Brown.

- Kohl, W.L., 1965. Nuclear sharing in NATO and the multilateral force. Political science quarterly, 80 (1), 88–109.

- Kohl, W.L., 1971. French nuclear diplomacy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Kunz, B., 2020. Switching umbrellas in Berlin? The Washington quarterly, 43 (3), 63–77.

- Lanchester, J., 2014. How to speak money? London: Faber.

- Lanoszka, A., 2018. Alliances and nuclear proliferation in the Trump era. The Washington quarterly, 41 (4), 85–101.

- Leah, C. and Lyon, R., 2010. Three visions of the bomb. Australian journal of international affairs, 64 (4), 449–477.

- Lebow, R.N., 2019. A democratic foreign policy. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lebow, R.N. and Stein, J.G., 1994. We all lost the Cold War. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Lee, S., 1985. The morality of nuclear deterrence. Ethics, 95 (3), 549–566.

- Le Point, 2018. La coûteuse modernisation de la dissuasion nucléaire. AFP, 21 June. Available from: https://www.lepoint.fr/societe/la-couteuse-modernisation-de-la-dissuasion-nucleaire-21-06-2018-2229213_23.php [Accessed 8 June 2020].

- Macron, E., 2020a. Speech of the President on the defense and deterrence strategy. Paris, 7 Feb. Available from: https://www.elysee.fr/en/emmanuel-macron/2020/02/07/speech-of-the-president-of-the-republic-on-the-defense-and-deterrence-strategy [Accessed 10 Feb 2020].

- Macron, E., 2020b. Interview to Le Grand Continent. 12 Nov. Available from: https://www.elysee.fr/emmanuel-macron/2020/11/16/interview-du-president-emmanuel-macron-a-la-revue-le-grand-continent [Accessed 17 Nov 2020].

- Malis, C., 2005. Raymond Aron et le débat stratégique français. Paris: Economica.

- Mallard, G., 2014. Fallout: nuclear diplomacy in an age of global fracture. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Marksteiner, A., 2017. Alternative futures. Atlantic Council, 18 July. Available from: https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/alternative-futures-rethinking-the-european-nuclear-posture/ [Accessed 12 Dec 2019].

- McDermott, R., Lopez, A.C., and Hatemi, P.K., 2017. “Blunt not the heart, enrage it”: the psychology of revenge and deterrence. Texas national security review, 1 (1), 68–88.

- McNamara, R.S., 1983. The military role of nuclear weapons. Foreign affairs, 62 (1), 59–80.

- Mey, H.M., 2001. Nuclear norms and German nuclear interests. Comparative strategy, 20 (3), 241–249.

- Miclot, I., 2011. L’OTAN, les civils et la “guerre future”. Les champs de mars, 21 (1), 101–119.

- Moretti, M., 2017. A never-ending story. In: E. Bini and I. Londero, eds. Nuclear Italy. Trieste: EUT Edizioni Università di Trieste, 105–118.

- Munich Security Conference, 2020. Zeitenwende – wendezeiten. Oct. Available from: https://securityconference.org/assets/01_Bilder_Inhalte/03_Medien/02_Publikationen/MSC_Germany_Report_10-2020_De.pdf [Accessed 12 Nov 2020].

- NATO, 1974. Declaration on Atlantic relations. Brussels: North Atlantic Council.

- Nicolaïdis, K. and Howse, R., 2002. ‘This is my Eutopia … ’: narrative as power. Journal of common market studies, 40 (4), 767–792.

- Oma, I.M. and Petersson, M., 2019. Exploring the role of dependence in influencing small states’ alliance contributions. European security, 28 (1), 105–126.

- Payne, K.B., 2017. Thinking anew about US nuclear policy toward Russia. Strategic studies quarterly, 11 (2), 13–25.

- Pelopidas, B., 2015a. A bet portrayed as certainty. In: G.P. Schultz and J.E. Goodby, eds. The war that must never be fought. Stanford, CL: Hoover Institution Press, 5–55.

- Pelopidas, B., 2015b. The nuclear straitjacket. In: S. von Hlatky and A. Wenger, eds. The future of extended nuclear deterrence. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 73–105.

- Pelopidas, B., 2016. Nuclear weapons scholarship as a case of self-censorship in security studies. Journal of global security studies, 1 (4), 326–336.

- Pelopidas, B., 2017. The unbearable lightness of luck. European journal of international security, 2 (2), 240–262.

- Pelopidas, B., 2020. Power, luck and scholarly responsibility at the end of the world(s). International theory, 12 (3), 459–470.

- Pelopidas, B., and Egeland, K., 2020. What Europeans believe about Hiroshima and Nagasaki—and why it matters. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 3 Aug. Available from: https://thebulletin.org/2020/08/what-europeans-believe-about-hiroshima-and-nagasaki-and-why-it-matters/.

- Perry, W., et al., 2009. America’s strategic posture. Washington, DC: United States Institute for Peace Press.

- Poirier, L., 1996. Stratégies Théoriques III. Paris: Economica.

- Poirier, L., 1976. Le deuxième cercle. Le Monde Diplomatique, July.

- Rapnouil, M.L., Varma, T., and Witney, N., 2018a. Can Europe become a nuclear power? European Council on Foreign Relations, 3 Sep. Available from: https://www.ecfr.eu/article/commentary_can_europe_become_a_nuclear_power [Accessed 14 Dec 2019].

- Rapnouil, M.L., Varma, T., and Witney, N., 2018b. Eyes tight shut. European Council on Foreign Relations, Dec. Available from: https://www.ecfr.eu/page/-/ECFR_275_NUCLEAR_WEAPONS_FLASH_SCORECARD_update.pdf [Accessed 12 Dec 2019].

- Ravenal, E.C., 1988. Extended deterrence and alliance cohesion. In: A.N. Saborsky, ed. Alliances in U.S. foreign policy. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 19–42.

- Ringsmose, J., 2010. NATO burden-sharing redux. Contemporary security policy, 31 (2), 319–338.

- Rose, M., 2020. Amid arms race, Macron offers Europe French nuclear wargames insight. Reuters, 7 Feb.

- Ross, R.S., 2002. Navigating the Taiwan strait. International security, 27 (2), 48–85.

- Sauer, T., 2020. Power and nuclear weapons: the case of the European Union. Journal for peace and nuclear disarmament, 3 (1), 41–59.

- Sauer, T. and Reveraert, M., 2018. The potential stigmatizing effect of the treaty on the prohibition of nuclear weapons. The nonproliferation review, 25 (5–6), 437–455.

- Schilde, K.E., Anderson, S.B., and Garner, A.D. 2019. A more martial Europe? Public opinion, permissive consensus, and EU defence policy. European security, 28 (2), 153–172.

- Schroeder, L., 2018. The ICRC and the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement. Journal for peace and nuclear disarmament, 1 (1), 66–78.

- Sechser, T.S. and Fuhrmann, M., 2017. Nuclear weapons and coercive diplomacy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sechser, T.S., Narang, N., and Talmadge, C., 2019. Emerging technology and strategic stability in pacetime, crisis, and war. Journal of strategic studies, 42 (6), 727–735.

- Shultz, G.P., et al., 2011. Deterrence in the age of nuclear proliferation. The Wall Street Journal, 7 Mar. Available from: https://media.nti.org/pdfs/NSP_op-eds_final_.pdf [Accessed 10 Apr 2020].

- Tertrais, B., 2019a. Will Europe get its own bomb? The Washington Quarterly, 42 (2), 47–66.

- Tertrais, B., 2019b. Braucht Europa einen eigenen Nuklearschirm? Welt, 29 Nov. Available from: https://www.welt.de/politik/ausland/article203903222/Verteidigungsstrategie-Braucht-Europa-einen-eigenen-Nuklearschirm.html?wtmc=socialmedia.twitter.shared.web [Accessed 11 Dec 2019].

- Unal, B. and Lewis, P., 2018. Cybersecurity of nuclear weapons systems. Chatham House, Jan. Available from: https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/publications/research/2018-01-11-cybersecurity-nuclear-weapons-unal-lewis-final.pdf [Accessed 5 June 2020].

- Vicente, A., 2019. European nuclear deterrence and security cooperation. In: C.A. Baciu and J. Doyle, eds. Peace, security and defence cooperation in post-Brexit Europe. Cham: Springer, 163–190.

- Vidal, J., 2020. “Tip of the iceberg”: is our destruction of nature responsible for Covid-19? The Guardian, 18 Mar.

- Volpe, T. and Kühn, U., 2017. Germany’s nuclear education. The Washington quarterly, 40 (2), 7–27.

- Walt, S., 1987. The search for a science of strategy. International security, 12 (1), 140–165.

- Wiegel, M. and Gutschker, T., 2020. Ein europäischer Atomschirm? Frankfurter Allgemeine, 6 Feb.

- Wimmer, F., 2018. European nuclear deterrence in the era of Putin and Trump. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 8 Jan. Available from: https://thebulletin.org/2018/01/european-nuclear-deterrence-in-the-era-of-putin-and-trump/ [Accessed 10 Apr 2020].

- World Economic Forum, 2020. The global risk report 2020. Insight report, 15th ed. Available from: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Global_Risk_Report_2020.pdf [Accessed 10 Apr 2020].