ABSTRACT

Stationing of US nuclear weapons in Europe is a pillar of NATO deterrence. Despite their growing contestation, scholarly research on contemporary attitudes of both voters and political elites to the continued stationing of these weapons on their soil is lacking. We conducted original surveys of 2020 Germans and of 101 Bundestag members. Our results show scepticism about the military utility of US nuclear weapons in Germany, and aversion towards their use. At the same time, the results show a sizable support among both politicians and citizens for their removal from German territory as part of new nuclear arms control initiatives.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

Nuclear deterrence has never worked and cannot work at all because it cannot be credible. What should be the scenario in which we would use atomic bombs in Europe? […] What an absurd idea that German pilots would carry nuclear weapons from Büchel towards the East to drop them there, and in doing so kill millions of people and to contaminate the environment for generations? […] Nuclear deterrence is an aberration. NATO will have to abandon this aberration, and sooner rather than later!

Germany has been at the heart of NATO’s nuclear debate since its very beginning and the development of nuclear sharing practice was, to a large extent, a response to concerns over the potential German nuclear armament (see Freedman and Michaels Citation2019, pp. 361–377). Although the details of the sharing arrangements remain officially classified, there is sufficient information in the public domain to understand their gist. At present, the United States stores about 20 B-61 nuclear gravity bombs at German Büchel Air Base, in addition to another over one hundred nuclear weapons that are deployed at military bases in Italy, Turkey, Belgium and the Netherlands (Kristensen and Korda Citation2020).

The future of NATO’s nuclear sharing arrangement continues to be a highly pertinent issue in European security, not least given the persisting concerns over the credibility of NATO’s collective defence commitments, the resurgence of great power competition in world politics, the crisis in US–Russian arms control, and the adoption of the 2017 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW). Yet, there is a lack of rigorous scholarly research systematically examining the contemporary attitudes of both voters and political elites in European hosting states to the continued stationing of these weapons on their soil. The few scholarly works that do any in-depth investigation of European attitudes to nuclear weapons focus exclusively on public views without a corresponding survey of elites (see, for example, recent publications of the researchers at the “Nuclear Knowledges” programme of Sciences Po Paris: Pelopidas and Egeland Citation2020, Egeland and Pelopidas Citation2021).

To fill this gap, we worked with polling company YouGov to conduct surveys among a representative sample of 2,020 German citizens and a unique elite sample of 101 members of the Bundestag, the lower house of the German federal parliament. In these surveys, we asked our respondents about their views of the role and future of US nuclear weapons in Germany, particularly focusing on the interplay between the military usefulness and political value of nuclear weapons.

Our results are not only the first that link the public and the elite views on forward-deployed nuclear weapons in Europe; they also uniquely gauge the views on keeping or withdrawing these weapons. The findings of our survey show that there is considerable support among both German politicians and citizens for the removal of US nuclear weapons from German territory, particularly if they were to be withdrawn as part of new nuclear arms control initiatives between the United States and Russia. While our respondents were split in their views on the deterrent function of these weapons, we found a remarkable aversion in both groups to any kind of military use, even in response to a hypothetical Russian nuclear strike.

The article proceeds as follows. First, we situate the current German withdrawal debate into the broader context of nuclear weapon debates in Germany. Second, we discuss the strategic and political foundations of nuclear sharing practice. Third, we discuss our methodology and the characteristics of the respective public and elite samples. Fourth, we present the results of our surveys. In conclusion, we discuss the scholarly and policy implications of our findings.

The German context

The German debate on nuclear sharing, which once again emerged in 2020, is reflective of a longer discussion about nuclear weapons in Germany.Footnote2 In 1945, Germany emerged from the Second World War traumatised by the catastrophe, became war-weary and fairly anti-militaristic. While Germany’s rearmament was necessary in the eyes of the German elites, the German public strongly resisted these plans. Nuclear weapons were part of this story. The idea/act of equipping the German army with weapons that would be a part of NATO’s nuclear deterrent met with strong domestic criticism, which eventually led to the largest peace and disarmament movement of the entire post-1945 German history, dwarfing even the sizable manifestations and protests of the 1980s in response to NATO’s “double track” decision (Risse-Kappen Citation1983). When arms control negotiations between the two superpowers stagnated and nuclear weapons re-entered the headlines in the second half of the 1970s (in response to the development of the “neutron bomb”) or in the 1980s (plans for the fielding of Pershing IIs in Europe), the streets of Germany were filled with anti-nuclear demonstrations (Müller & Risse-Kappen Citation1987).

Whereas the overwhelming number of these protesters were centre-left and left, even the conservatives and liberals could not ignore the widespread concern about nuclear dangers among their own voters. The conservatives held a genuine concern about a nuclear war that would be fought out on the territories of the European allies while the superpowers’ territories would remain sanctuaries, which led to increasing resentment against shorter-range nuclear weapons deployed in Europe. In the 1980s, Alfred Dregger, the chair of the conservative caucus in the Bundestag, and Egon Bahr, a former social democrat, coined the phrase “the shorter the range, the deader the Germans” (Bahr Citation2014, Elbe Citation2016).Footnote3 This gave pointed expression to a German conservative version of “nuclear pacifism” – the view that nuclear weapons were meant to prevent war and never to be used (Der Spiegel Citation1988). In this idea of an “eternal non-use” through “eternal deterrence”, the conservative objectives converged with those of the anti-nuclear left, while the two sides continued to disagree on the tools to achieve these goals (on this conservative nuclear “philosophy”, see Dregger Citation1955).

After the end of the Cold War, the issue of nuclear weapons has gradually lost its salience. The past decade, in particular, saw little political debate about the role and future of nuclear weapons stationed on German territory. For example, German analyst and former Bundestag staffer Pia Fuhrhop recently noted that “since [2013], one may even argue that a substantive debate on nuclear deterrence does not exist at all [in Germany]” (Fuhrhop Citation2021, p. 27). Several factors played into the renewal of nuclear withdrawal discussions in Germany: the nuclear ban treaty negotiations which took place in 2017 and led to the TPNW adoption, Russia’s increasing nuclear sabre-rattling in the aftermath of its aggression against Ukraine, and the Trump Administration’s disinterest in the arms control agenda, demonstrated by a withdrawal from the INF treaty (Meier Citation2016, Volpe and Kühn Citation2017).

The political debate that started in spring 2020 nevertheless converged around a seemingly technical subject: the renewal of the dual-capable aircraft fleet, as the Tornado fighter jets, currently assigned to the nuclear task, were nearing the end of their lifetime. Germany, as opposed to other European countries, did not select the F-35 fighter jet, opting instead for studying possible cooperation with France on a pan-European solution (Binnendijk and Townsend Citation2020). As a temporary solution, in 2020, Germany decided to acquire F-18 fighter jets (Deutsche Welle Citation2020) – yet the cost of that acquisition renewed the discussion of whether Germany still needs nuclear-capable aircraft (Fuhrhop Citation2021 provides an excellent summary of this debate).

The opponents of nuclear sharing saw this as an opportunity to do away with this arrangement and perhaps even for Germany to join the TPNW. “Nuclear weapons in Germany do not increase our security – on the contrary”, stated the chairman of the parliamentary caucus of the German Social Democratic Party (SPD) Rolf Mützenich during an interview with Der Tagesspiegel in May 2020 in a firing shot of the debate. He continued by saying that he took “a clear position against stationing and control over – and especially against the use of – nuclear weapons” (Tagesschau Citation2020). Mützenich’s statements have been subsequently condemned by Germany’s sitting foreign minister (and Mützenich’s party colleague) Heiko Maas (Monath Citation2020), as well as representatives of the centre-right Christian Democratic Union/Christian Social Union (CDU/CSU) and the opposition liberals in the Free Democratic Party (FDP) (Zeit Online Citation2020). Yet the parliament continued to be seized on the subject, holding a contentious debate on joining the TPNW in January 2021 (Deutscher Bundestag Citation2021, p. 26188ff).

Military and political foundations of nuclear sharing

The advocates of NATO’s nuclear sharing arrangement mention military as well as political rationale for keeping US nuclear weapons in Europe.Footnote4 Whereas the military aspect of nuclear sharing has been mainly related to the deterrent and warfighting functions of these weapons in the European theatre, the political one has been linked to their alleged value as tools for signalling, commitment and influence in the Alliance politics, as well as a bargaining chip in arms control negotiations.

Military goals

Traditionally, the theorists of nuclear deterrence have argued that the stationing of nuclear weapons in Europe deters both nuclear and non-nuclear attacks against European NATO members. Already at the time of deployment in the 1950s, the chief goal of deployment was to limit the possibility of conventional Soviet attack (Dyer Citation1977, Freedman and Michaels Citation2019, pp. 361–364). The strategists at that time expected that because of Soviet military superiority, the Soviets would be able to attack the West without the need for nuclear escalation. Dyer also argued that nuclear escalation would not make sense if Soviets wanted to seize Western Europe intact (Dyer Citation1977). As Lieber and Press (Citation2020) argue, NATO adopted a nuclear escalatory posture in this period because the risk of conventional defeat was high and because the consequences of such a defeat would be catastrophic.

In the logic of the deterrence argument, forward-deployed nuclear weapons would shift the local balance of power in favour of the weaker party. Not only would they enable the destruction of the adversary’s troops, but their use would also be inherently more credible, as the deployment decisions would be in the hands of local commanders (Biddle and Feaver Citation1989, Fuhrmann and Sechser Citation2014). This made the nuclear umbrella “a key element of the containment strategy” (Gavin Citation2015, p. 31). In the views of many, the forward-deployed nuclear weapons have remained an essential element of the NATO nuclear deterrence strategy until today (Yost Citation2011, Pilat Citation2016).

However, there has been much scepticism about how believable this strategy is. To start with, there is a long-standing fear of abandonment, originating in the days of the Cold War. Once the Soviet Union gained the possibility to strike the US territory, the question of nuclear deterrence shifted to the fundamental question whether the United States would indeed be willing to attack an adversary using nuclear weapons if Washington were to face a nuclear response. For example, during a meeting with President Kennedy, French President De Gaulle famously raised a question “whether [the United States] would be ready to trade New York for Paris” (Memorandum of Conversation Citation1961). In other words, there have been serious doubts whether the United States would risk nuclear retaliation against its own territory just to protect its NATO ally.

For this reason, many scholars have considered the (low) credibility of commitments to use nuclear weapons in response to attacks against NATO allies to be the key problem of NATO’s deterrence posture (Schelling, Citation1960, Citation1966, Powell Citation1990, Danilovic Citation2001). This uncertainty is even higher once we discuss the possibility of using nuclear weapons to respond to a non-nuclear attack. For example, Fetter and Wolfstahl (Citation2018, p. 108) suggest that extended deterrence against non-nuclear attacks “is much less credible, particularly with regard to Russia or China”. Finally, some experts also question the actual military utility of US nuclear weapons in allied states and their usefulness for achieving NATO’s potential military goals in Europe (Woolf Citation2021).

Political goals

Given the concerns about the military value of US nuclear weapons in Europe, some scholars and experts argue that the main purpose of these weapons is to strengthen the ties between European allies and the United States. In this view, the presence of forward-deployed nuclear weapons constitutes a “tripwire” whose main purpose is not to defeat the enemy, but to draw the United States into the conflict in Europe (Schelling Citation1966). According to this logic, the stationing contributes to the amelioration of the alliance security dilemma at a relatively moderate cost – at least compared to the alternatives (Snyder Citation1984, Haftendorn Citation1996, Sechser Citation2016).Footnote5 From the rationalist point of view, deploying nuclear weapons to the ally’s territory ties the patron’s hands and therefore represents a “costly signal” (Fearon Citation1997, p. 69ff). By doing so, the deployment of nuclear weapons in Europe ties the two ends of the transatlantic alliance and acts as a symbol of American commitment to the defence of Europe (Suchy and Thayer Citation2014, Rudolf Citation2020). For a number of these countries, accepting US nuclear weapons might arguably serve also as a replacement for possessing their own nuclear weapons (Gerzhoy Citation2015, Nuti Citation2010).Footnote6 Today, this has been particularly relevant to allies on NATO’s eastern flank (von Hlatky Citation2014).

Another chiefly political reason to seek deployment of nuclear weapons on allied state’s territory has to do with enhancing the hosting state’s intra-alliance status. Since the beginning of the practice of nuclear sharing, the stationing of US nuclear weapons has been associated with the idea of being a “first class” ally. Historical work on the origins of nuclear sharing in the Netherlands, for example, clearly shows that the Dutch sought deployment of nuclear weapons to foster the country’s standing in the alliance (van der Harst Citation1997). Nuclear sharing, in this view, gives the hosting country a special role in NATO and establishes a unique bond with the United States. For example, Meier (Citation2020b, p. 79ff) argues that German officials see participation in NATO nuclear sharing as giving Germany a unique say in the NATO nuclear policy. This view was also iterated in an opinion piece in the influential Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung by former NATO Assistant Secretary-General Heinrich Brauß (Citation2020). Similarly, leading members of (the then-presidential candidate) Joe Biden’s national security team stated in their 2020 article in Der Spiegel that thanks to the stationing of nuclear weapons, “Germany has a seat at a very exclusive table in Brussels and plays a strong role in deciding what happens at that table” (Flournoy and Townsend Citation2020). Public pronouncements in other countries that host nuclear weapons support this view. The Dutch government’s Advisory Council for International Affairs, for example, argued in a recent report that participation in the NATO nuclear task gives the Netherlands special weight in NATO (Kabinetsreactie op AIV-adviesrapport Citation2019).

Finally, states might accept nuclear deployments in order to spur arms control discussions. This view is reflected in Schelling and Halperin’s (Citation1961) classic book on arms control, where they argue that states might shore up weapons to force the counterpart into negotiation and to make sure that they reap benefits from the negotiations. In a similar fashion, Egeland (Citation2020) argues that in the 1980s, European countries agreed with new deployments of US nuclear weapons for these weapons to function as bargaining chips in arm control negotiations with the Soviets. These arguments might be relevant in today’s strategic environment as well: the latest proposals for nuclear arms control negotiations between Russia and the United States included Russian demands to address tactical nuclear weapons deployed in Europe (Higgins Citation2020).

Survey of German elites and citizens

To field our surveys, we worked with YouGov, a leading pollster (for recent uses, see Gravelle et al., Citation2017, Sagan and Valentino Citation2017, Carpenter and Montgomery Citation2020). We conducted two surveys with identical questions – one on a sample of German political elites and the other one on the representative sample of the German public.

The elite survey focused on members of Bundestag, the lower house of the German federal parliament. This sample allowed us to capture the views of elites across the entire German political spectrum, including the parties outside the government. While the role of parliaments in foreign policy has traditionally been limited, it has gradually been increasing (Raunio and Wagner Citation2017). Even though the direct, formal tools of parliaments in this area are often restricted to voting on treaty ratification and troop deployment, parliaments also made their views visible via other means, such as budget approvals, discussions about strategies, hearings, or subpoena powers. This argument can be made about foreign and security policy in general and the specific case of nuclear policy in particular. Parliaments in countries possessing nuclear weapons have often sought to find tools to fulfil their democratic mandate (Born, Gill and Hänggi Citation2011). The story is very similar to the Bundestag, which plays an increasingly important role in consulting on foreign policy and exercises its influence through the power of the purse (Harnisch Citation2006, Jäger et al. Citation2009 Wagner et al. Citation2010). Because the Bundestag is where the money for F-16 replacement would have to be formally approved, the German parliament is also where the debate over the future of the nuclear sharing arrangement has been particularly active in the past year (Meier Citation2020a).

YouGov administered the elite survey between 16 June and 31 July 2020. Our final elite sample consists of 101 out of 709 members of the 19th Bundestag (for a sample size comparison, see Wonka and Rittberger Citation2014, Bayram Citation2017a, Bayram Citation2017b, Citation2017c). Our sample approximates the composition of the Bundestag with respect to party affiliation, gender and regional distribution.Footnote7

To provide a comparative elite–public perspective, we subsequently asked YouGov to run an identical survey on a representative sample of the adult German population. This survey was fielded between 23 and 26 October 2020. The 2,020 respondents were selected to approximately represent the socio-demographic composition and regional diversity of the overall German population.Footnote8

In the survey, we asked the respondents for their views on three aspects of the nuclear sharing arrangement: the purpose of the weapons, conditions under which they could be withdrawn, and conditions under which they could be used. For each question, we provided the respondents with a statement that they evaluated on a six-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree, disagree and slightly disagree to slightly agree, agree and strongly agree, with a possibility to select an “I don’t know” option. For the analysis and the presentation of our results, we dichotomised the 1–6 responses to “disagree” (1–3) and “agree” (4–6) and reported the percentage counts for each question and sample.

In addition to the battery of questions pertaining to these three issues, the respondents in the public survey provided us with information about their gender, age, region in Germany and long-term political party preference. For the elite sample, we were able to collect information about individual parliamentarians’ party affiliation, gender and their region of origin in Germany.Footnote9

German views on nuclear sharing

Political and military purpose

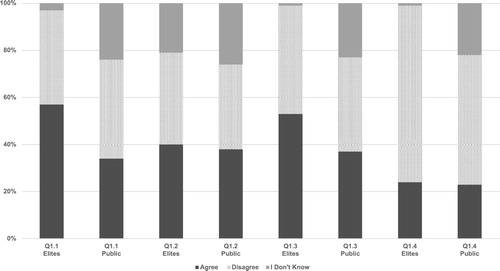

We start by looking at how respondents perceive the purpose of nuclear weapons in Germany – whether they believe in the deterrent value of these weapons, and whether they think that such stationing gives Germany a special weight within NATO and in the bilateral relationship with the United States. We asked our respondents whether they agree or disagree with the statements that the stationing of US nuclear weapons in Germany “deters nuclear attacks against NATO countries” (Q1.1) and that it “deters non-nuclear attacks against NATO countries” (Q1.2). Then we repeated this procedure with two statements related to the political purpose of these weapons: “the stationing of the US nuclear weapons in Germany gives Germany political weight within NATO” (Q1.3) and “gives Germany special influence on U.S. nuclear policy” (Q1.4).

As we show in , a majority (57%) of elite respondents in our survey were convinced that US nuclear weapons in Germany deterred nuclear attacks against NATO members (40% disagreed). Yet, the proportion of those who agreed with the statement dropped down to only 34% in the public sample (42% disagreed). The numbers then become strikingly similar once we ask the respondents about their beliefs regarding the deterrence of non-nuclear attack – 40% of the elite respondents and 38% of the public agreed that the stationing of US nuclear weapons deterred non-nuclear attacks against NATO allies, whereas 39% and 36% respectively disagreed.

About a quarter of the public respondents did not know the answer to either of the two questions. Yet, interestingly, while a relatively high number of respondents in the elite sample did not know how to respond to the statement on the deterrence of non-nuclear attacks (22%), only 3% responded “I don’t know” to a question about the deterrence of nuclear attacks. The results from our survey clearly indicate that German parliamentarians believe in nuclear deterrent effects of the weapons stationed in Germany but are relatively sceptical about the deterrence against non-nuclear attacks. The general public appears to be quite sceptical about both – only slightly more than one-third believes in either of the two.

In addition to these aggregate findings, we also identified some variation across major political parties, with the centre-right CDU–CSU and liberal FDP being more convinced about the deterrent effect of US nuclear weapons against nuclear and non-nuclear attacks, as opposed to left-wing parliamentarians and voters being more sceptical. Only in two parties – the left-leaning Die Linke and the Greens – did a majority of parliamentarians and voters disagree with the deterrence logic of US nuclear weapons in Germany.

We then asked the parliamentarians and voters to what extent they agreed with the statements that the stationing of US nuclear weapons gives Germany a political weight in NATO (Q1.3.) and a special influence over US nuclear policy (Q1.4.). The parliamentarians seem to be more convinced about the claim that nuclear sharing elevates the hosting state’s status within the alliance (53% agreed, 46% disagreed) than the respondents in the public sample (37% agreed, 40% disagreed). Both the German elite respondents and the public appear to be rather sceptical about the idea of maintaining any special leverage over US nuclear policy as a consequence of stationing these weapons – only 24% of parliamentarians agreed with this statement and 75% disagreed, whereas 23% of citizens agreed and 55% disagreed. Once again, respondents affiliated with right-wing parties (particularly the CDU/CSU) tend to be, on average, more inclined to believe in the political influence granted by these weapons, whereas the left-leaning respondents (particularly Die Linke) remain largely unconvinced.

Prospective withdrawal of weapons

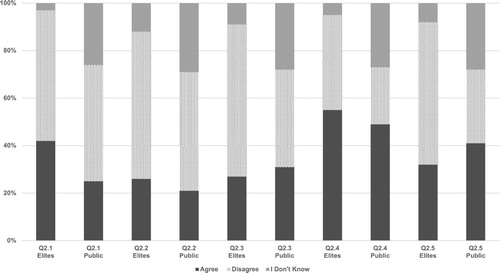

In the second part of the survey, we presented five statements on the conditions for the prospective withdrawal of US nuclear weapons from Germany. First, the respondents expressed their (dis)agreement with the most conservative statement that “the U.S. nuclear weapons in Germany should not be withdrawn under any circumstances” (Q2.1). To see whether our respondents would be receptive to the “trade-off logic,” we asked whether “U.S. nuclear weapons in Germany can be withdrawn if there are additional reinforcements by U.S. troops” (Q2.2) or “if NATO European countries including Germany strengthen their conventional capabilities” (Q2.3). To assess the relevance of the aforementioned bilateral arms control process between Washington and Moscow, we asked whether “U.S. nuclear weapons in Germany can be withdrawn if the U.S. and Russia agree on further arms control steps” (Q2.4). Finally, to investigate the level of support for unconditional withdrawal, we asked whether “U.S. nuclear weapons should be withdrawn without any preconditions” (Q2.5).

As we show in , the most status quo-oriented option – that the weapons should not be withdrawn under any circumstances (Q2.1) – was supported by 42% of elite respondents (55% disagreed) and 25% of the public (49% disagreed). Both elites and the general public therefore appear to be open to the possibility of withdrawal of US nuclear weapons from Germany.

Neither of the two “trade-off” options – withdrawing US nuclear weapons in exchange for conventional reinforcements provided by the United States (Q2.2) or the strengthening of conventional capabilities in European NATO countries (Q2.3) – received much support in the elite or public sample. Only 26% of elite respondents and 21% of the public supported the former policy (62% of parliamentarians and 50% of the public disagreed) and 27% of the elites and 31% of the public supported the latter (64% of parliamentarians and 41% of the public disagreed).

The option that clearly received the most support among both parliamentarians and ordinary citizens was the idea that nuclear weapons would be withdrawn as a part of a new arms control agreement between Russia and the United States (Q2.4). A total 55% of respondents in the elite sample (40% disagreed) and 49% of the public (only 24% disagreed) agreed with this proposition. In all caucuses (except for the Greens), a majority of parliamentarians agreed with this proposal, and the voters are similarly supportive: the support ranges from 49% among the AfD voters to 59% among Die Linke voters. This scenario is in line with the arms control arguments, which argue that the European countries agree to the deployment of nuclear weapons on their territory in part to spur arms control with Russia.

The last scenario portrayed a straightforward withdrawal of US nuclear weapons from Germany without any preconditions (Q2.5), to which 32% of parliamentarians in our sample agreed and 60% disagreed. The support for this policy was significantly higher in the public sample, where 41% opted for unconditional withdrawal and only 31% opposed it. Among the parliamentarians, the agreement rose above 40% among the Greens, Die Linke and AfD, while among the voters, 69% of Die Linke sympathisers supported the policy, followed by 48% of Greens, 44% of the AfD voters, 39% of Social Democrats, 32% FDP and 30% CDU/CSU. On balance, the voters clearly appear to be much more unilateralist compared to their representatives in the Bundestag. This elite reluctance towards unilateralism can also be observed ahead of the 2021 elections in the draft manifesto of the Greens, who argue for the withdrawal of nuclear weapons, but only in consultation with allies (Bündnis Citation90/Die Grünen Citation2021).

Nuclear weapon use

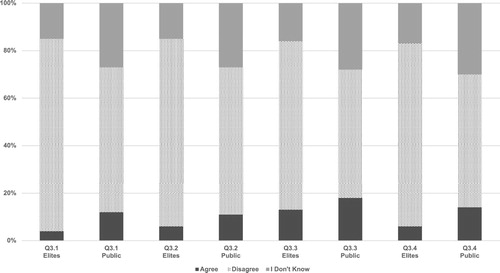

In the third and final part of our survey, we asked our respondents to imagine that there was a military conflict between NATO and Russia in the Baltics. Given the range of US nuclear weapons stationed in Germany, it is currently difficult to conceive of any other credible military use for these weapons but their employment against the Russian Federation on NATO’s eastern flank (see, for example, Suchy and Thayer Citation2014, McCrisken and Downman Citation2019).Footnote10 In the survey, the respondents expressed their degree of agreement with four statements on the conditions under which it could be legitimate to employ nuclear weapons in that conflict. The first scenario entailed “a demonstrative explosion over an unpopulated area to de-escalate in an attempt to stop an ongoing Russian invasion of the Baltic countries” (Q3.1). The second scenario involved the use of nuclear weapons “to target Russian military units and thereby gain a military advantage over Russia in the conflict” (Q3.2). The third scenario would see “a demonstrative explosion over an unpopulated area to respond to a similar demonstrative nuclear explosion conducted by Russia” (Q3.3). In the fourth scenario, US nuclear weapons in Germany would be used “to target Kaliningrad as a response to a Russian nuclear strike against NATO troops, in an attempt to stop an ongoing Russian invasion of the Baltic countries” (Q3.4).Footnote11

In , we present the results in relation to four scenarios that involved the employment of US nuclear weapons that are stationed in Germany. Unlike the opinions on the purpose of US nuclear weapons or US withdrawal, where the opinions seem to be split along party lines, a significant majority of respondents in both the elite and public surveys disagreed with the use of nuclear weapons under any condition. In fact, in all four scenarios, the most common response was to “strongly disagree” with nuclear weapon use. While the general aversion to the use of nuclear weapons in any of our scenarios applies to both the elite and the public samples, the elite respondents nevertheless consistently expressed stronger anti-nuclear sentiments than the public. On average, across the scenarios, 7% of parliamentarians agreed with nuclear weapon use (and 77% disagreed), whereas 14% of the public agreed (and 58% disagreed). The option that received relatively the highest support in both the elite and public sample was Q3.3 (a demonstrative nuclear explosion in response to a similar Russian nuclear demonstration): 13% of elites agreed with nuclear use and 71% disagreed, whereas 18% of the public agreed and 54% disagreed.

These findings suggest that given the current range of these weapons, it does not seem too far-fetched to claim that neither a majority of German citizens nor a majority of political elites see a legitimate military mission for the US nuclear weapons stationed in Germany.Footnote12 Our data on public attitudes also stand in contrast with recent surveys of citizens’ attitudes to nuclear use in the United States, which suggest a somewhat lower “atomic aversion” among the general public than we found in the case of Germany (Press et al. Citation2013, Sagan and Valentino Citation2017, Carpenter and Montgomery Citation2020, Rathbun and Stein Citation2020, Smetana and Vranka Citation2021).

Implications and conclusions

Throughout the previous section, we highlighted a number of views in which the German elites and general public differ when it comes to the nuclear weapons. Our results show that the German public is much more sceptical than the elites about the deterrent effect of US nuclear weapons against nuclear threats and less convinced that participating in the nuclear sharing arrangement grants Germany a special position within NATO. Overall, the scepticism about the value of these weapons is also reflected in the higher support for the unconditional withdrawal of these weapons, as well as resistance against the current status quo. These findings speak to the recent discussion about “nuclear guardianship,” the idea that nuclear weapons are removed from the democratic debate and that nuclear weapons policies often do not reflect public views and do not follow the norms of good democratic governance (see, for example, Scarry Citation2014, Pelopidas Citation2019, Pelopidas and Fialho Citation2019, Baron et al. Citation2020, Egeland and Pelopidas Citation2021).Footnote13

However, we also identified a number of important areas where the political elites and the citizens find common ground. Both groups are similarly sceptical about the deterrent effect of US nuclear weapons against non-nuclear threats. They are both supportive of their withdrawal in the context of the future arms control negotiations between the United States and Russia. They are also strongly averse to any kind of military employment of these weapons.

Our findings highlight the paradoxical nature of how individuals think about nuclear weapons and nuclear deterrence. On the one hand, a majority of German parliamentarians and about one-third of German citizens in our sample believe that nuclear weapons deter nuclear attacks against NATO members. On the other hand, many of the same respondents fundamentally disagree with practically any conceivable military use of such weapons, even in the face of prospective Russian aggression against European NATO allies and even when Russia is the first to employ nuclear weapons in the conflict. This contradiction underlines the claim that nuclear weapons mainly fulfil – at least in the minds of Germans – a political signalling function rather than strictly military objectives. This is exactly in line with the view that the nuclear weapons stationed in Europe are primarily political rather than military tools (Rudolf Citation2020).

Such findings have, nevertheless, potentially important implications for the effectiveness of NATO’s extended deterrence in Europe, as they seriously question the purported willingness to employ nuclear weapons once deterrence fails.Footnote14 The logic of deterrence theory dictates that if enemies do not perceive commitments to retaliate with nuclear weapons as credible, they will be tempted to exploit this credibility gap and engage in aggression with impunity. Given the ongoing modernisation of the Russian nuclear arsenal, the continued reliance on nuclear weapons for Russia’s international prestige and security (Fink and Oliker Citation2020), and the US and NATO’s concerns about an alleged Russian nuclear “escalate-to-deescalate” doctrine (Ven Bruusgaard Citation2016, Citation2020, Department of Defense Citation2018, Kroenig Citation2018, Oliker and Baklitskiy Citation2018, Smetana Citation2018), the credibility of allied commitments arguably continues to be highly relevant also in today’s strategic environment.

The long-standing German aversion towards nuclear weapons, which we discussed earlier in this article, might help to explain the aforementioned paradox. However, in our surveys, we also found that while German elites are more convinced about the effects of nuclear deterrence, they are simultaneously even more opposed to the use of nuclear weapons than the general public. This may be related to the fact that political elites are more socialised with informal prohibitory non-use norms, whether they are based on the moral “sense of revulsion” (Tannenwald Citation2002), or the rule of prudence and rational strategic calculation (Sagan Citation2004, Paul Citation2009). In their political functions, the parliamentarians are more exposed to the prevailing diplomatic discourse about the unacceptability of any nuclear weapon use, and they are also more knowledgeable about the potential real-world consequences of the employment of nuclear weapons (Smetana and Wunderlich Citation2021). As such, our findings also conform to the claim that the nuclear taboo is “increasingly an elite phenomenon” (Tannenwald Citation2021).

Finally, the strong support for the withdrawal of US nuclear weapons from Germany as a part of the future arms reduction agreement between Washington and Moscow underscores the continued support for nuclear arms control among Europeans. When the Trump administration announced the withdrawal from the INF treaty and later hesitated with the extension of the New START treaty, European allies expressed their strong support for multilateral solutions (European External Action Service Citation2019). Based on our data, we can demonstrate that German parliamentarians and voters across the political spectrum see it as “fair game” if the nuclear weapons in Germany are withdrawn as a consequence of such steps. Russian diplomats repeatedly pointed to the withdrawal of US nuclear weapons from Europe as a necessary precondition for negotiating a follow-up treaty to New START that would address all nuclear warheads, strategic and non-strategic (Diakov et al. Citation2021, Pifer Citation2021). US President Joe Biden expressed his clear “commitment to arms control for a new era” (Biden Citation2020), whereupon he extended New START and expressed willingness to negotiate a follow-up treaty with Moscow to replace it. The removal of US nuclear weapons from Europe in the context of forthcoming bilateral arms control initiatives therefore appears to be not just the most likely pathway but also the one that would probably be most highly supported in the hosting state. In fact, the German government recently co-funded a project to examine the possibilities for a withdrawal of non-strategic nuclear weapons from Europe.Footnote15 Our results suggest that there is a lot of internal political buy-in for this step, both among the German public and the political elites.

Acknowledgements

We thank the European Security editor and two excellent reviewers, as well as Harald Müller, Matthew Kroenig, Morgan L. Kaplan, Oliver Meier, Falk Ostermann, Liviu Horovitz, Mauro Gilli, Monika Sus, Richard Maher, Marek Vranka, Ondrej Rosendorf, Michal Parizek, Kamil Klosek, Jakub Tesar, Jan Ludvik, Irena Kalhousova, Vojtech Bahensky, Tomas Weiss, Jakub Zahora, Tomas Bruner and Krystof Kucmas for valuable comments, ideas and recommendations. Hannah van den Brink helped us with research assistance. All errors remain our own.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 For an overview of the new round of this debate that opened in spring 2020, see Meier (Citation202Citation1), Fuhrhop (Citation2021) and Smetana, Onderco, and Etienne (Citation2021).

2 We are very thankful to Harald Müller for his comments, ideas and a number of specific suggestions for this section.

3 As one of the reviewers of this article rightly pointed out, the actual authorship of this quote has been contested, highlighting that both conservatives and social democrats shared similar views on this issue.

4 It is worth noting that official public justifications for different kinds of nuclear weapon policies have often been at odds with the decision makers’ real rationale behind such policies. See, for example, Gavin (Citation2001), Rosenberg (Citation1983), or Eden (Citation2011).

5 The same fear was held by Central European allies after joining NATO, which led them to seek an American nuclear umbrella (see Horovitz, Citation2014).

6 For a scholarly critique of the idea that extended deterrence is an effective non-proliferation instrument, see Pelopidas, Citation2015.

7 See the appendix for a detailed comparison of our sample with the population of the 19th Bundestag. YouGov invited all members of the Bundestag to participate in the research via an invitation to an online survey. Non-responders were contacted by telephone in order to complete the survey and reach our desired number of one hundred completes.

8 See https://yougov.co.uk/about/panel-methodology/ for more details about YouGov’s sampling technique.

9 Nine parliamentarians preferred not to disclose their party affiliation and gender in the survey. We account for this when we discuss the results with respect to these factors.

10 For a critical discussion of the nuclear aspects of the Russian threat to the Baltics, see Lanoszka, Citation2019

11 To ensure a diversity of conditions as well as sufficient real-world relevance, we consulted these hypothetical scenarios with experts on nuclear weapons and NATO-Russia military relations. We are particularly grateful to Matthew Kroenig for his valuable feedback and recommendations.

12 We did not include a scenario that would involve the use of forward-deployed U.S. nuclear weapons in response to a direct (whether nuclear or conventional) Russian attack on German territory. While it is conceivable that the use of nuclear weapons would be supported more by the respondents in such scenario than in those four that we included, a direct attack of Russia on Germany does not seem to be a credible possibility in the near future and neither NATO nor Germany itself are seriously discussing it as a potential near-term threat.

13 We are thankful to one of the reviewers of this paper for suggesting this linkage to us.

14 Admittedly, it is the German government rather than the German parliament that would be making the decision over the use of these weapons (together with American counterparts) in the event of war. Nevertheless, our survey convincingly demonstrates a strong aversion to nuclear weapon use among parliamentarians irrespective of political affiliation. Given such homogeneity in (non-)use attitudes among German political elites and the fact that the German government mostly consists of career politicians, it appears unlikely that the average opinion of cabinet members would significantly differ on this issue from the opinions of current parliamentarians.

15 See the reference in https://twitter.com/Gottemoeller/status/1383124800416088065

References

- Bahr, E., 2014. The shorter the range, the deader the Germans. In: W. Ischinger, ed. Towards mutual security. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 113–118.

- Baron, J., Gibbons, R. D., and Herzog, S., 2020. Japanese public opinion, political persuasion, and the treaty on the prohibition of nuclear weapons. Journal for Peace and Nuclear Disarmament, 3 (2), 299–309.

- Bayram, A.B., 2017a. Cues for integration: foreign policy beliefs and German parliamentarians’ support for European integration. German politics and society, 35 (1), 19–41.

- Bayram, A.B., 2017b. Due deference: cosmopolitan social identity and the psychology of legal obligation in international politics. International organization, 71 (S1), S137–S163.

- Bayram, A.B., 2017c. Good Europeans? How European identity and costs interact to explain politician attitudes towards compliance with European Union law. Journal of European public policy, 24 (1), 42–60.

- Biddle, S.D., and Feaver, P., 1989. Battlefield nuclear weapons: issues and options (Vol. 5). Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

- Biden, J.R., 2020. Why America must lead again: rescuing U.S. Foreign policy after Trump. Foreign Affairs. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2020-01-23/why-america-must-lead-again.

- Binnendijk, H., and Townsend, J. 2020. German F-35 decision sacrifices NATO capability for France-German industrial cooperation. Defense One. https://www.defensenews.com/opinion/commentary/2019/02/08/german-f-35-decision-sacrifices-nato-capability-for-franco-german-industrial-cooperation/.

- Born, H., Gill, B., and Hänggi, H., 2011. Governing the bomb: civilian control and democratic accountability of nuclear weapons. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Brauß, H., 2020. Atomdebatte in der SPD: Rolf Mützenich hat Unrecht. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. https://www.faz.net/aktuell/politik/inland/atom-debatte-in-der-spd-rolf-muetzenich-hat-unrecht-16757761.html?printPagedArticle=true#pageIndex_2.

- Bündnis 90/Die Grünen. 2021. Deutschland. Alles Ist Drin. Programmentwurf Zur Bundestagswahl 2021. https://cms.gruene.de/uploads/documents/2021_Wahlprogrammentwurf.pdf.

- Carpenter, C., and Montgomery, A.H., 2020. The stopping power of norms: saturation bombing, civilian immunity, and U.S. attitudes toward the laws of war. International security, 45 (2), 140–169.

- Danilovic, V., 2001. The sources of threat credibility in extended deterrence. Journal of conflict resolution, 45 (3), 341–369.

- Department of Defense., 2018. Nuclear posture review. Washington, DC: Office of the Secretary of Defense.

- Der Spiegel., 1988. … desto deutscher die Toten. https://www.spiegel.de/spiegel/print/d-13527931.htm.

- Deutsche Welle., 2020. Germany considers nuclear-capable F-18 to replace its aging fleet. https://www.dw.com/en/germany-considers-nuclear-capable-f-18-to-replace-its-aging-fleet/a-53202359.

- Deutscher Bundestag., 2021. Stenografischer Bericht. 207. Sitzung. Berlin, Freitag, den 29. January 2021. Plenarprotokoll 19/207. https://dipbt.bundestag.de/dip21/btp/19/19207.pdf.

- Diakov, A., Miasnikov, E., and Kadyshev, T., 2021. Nuclear reductions after new START: obstacles and opportunities Arms Control Today. https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2011-05/nuclear-reductions-after-new-start-obstacles-opportunities#21.

- Dregger, A., 1955. Für eine wirksamere Nichtverbreitungs- und Abrüstungspolitik. Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte, 6 (3), 21–26.

- Dyer, P.W., 1977. Tactical nuclear weapons and deterrence in Europe. Political Science quarterly, 92 (2), 245–257.

- Eden, L., 2011. The U.S. nuclear arsenal and zero: sizing and planning for use – past, present, and future. In: C. Kelleher and J Reppy, eds. Getting to zero: the path to nuclear disarmament. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 69–89.

- Egeland, K., 2020. Spreading the burden: how NATO became a “nuclear” alliance. Diplomacy & statecraft, 31 (1), 143–167.

- Egeland, K., and Pelopidas, B., 2021. European nuclear weapons? Zombie debates and nuclear realities. European security, 30 (2), 237–258.

- Elbe, F., 2016. Je kürzer die Reichweite, desto toter die Deutschen. Gedanken zum Ableben von Hans-Dietrich Genscher,. Welttrends No.114. https://frankelbe.files.wordpress.com/2016/05/nachruf-genscher-in-welttrends.pdf.

- European External Action Service., 2019. EU Statement – United Nations Preparatory Committee for the Treaty on Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT): Cluster I issues. https://eeas.europa.eu/headquarters/headquarters-homepage/61677/eu-statement-united-nations-preparatory-committee-treaty-non-proliferation-nuclear-weapons-npt_en.

- Fearon, J.D., 1997. Signaling foreign policy interests. Journal of conflict resolution, 41 (1), 68–90.

- Fetter, S., and Wolfsthal, J., 2018. No first use and credible deterrence. Journal for peace and nuclear disarmament, 1 (1), 102–114.

- Fink, A.L., and Oliker, O., 2020. Russia’s nuclear weapons in a multipolar world: guarantors of sovereignty, great power status & more. Daedalus, 149 (2), 37–55.

- Flournoy, M., and Townsend, J., 2020. Striking at the Heart of the Trans-Atlantic Bargain. Der Spiegel International. https://www.spiegel.de/international/world/biden-advisers-on-nuclear-sharing-striking-at-the-heart-of-the-trans-atlantic-bargain-a-e6d96a48-68ef-49ab-8a0c-8a979abf2bb4.

- Freedman, L., and Michaels, J.H., 2019. The evolution of nuclear strategy (Fourth ed.). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Fuhrhop, P., 2021. The German debate: The Bundestag and nuclear deterrence. In: A. Morgan and A. Péczeli, eds. Europe’s evolving deterrence discourse. Livermore, CA: Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, 27–38.

- Fuhrmann, M., and Sechser, T.S., 2014. Signaling alliance commitments: hand-tying and sunk costs in extended nuclear deterrence. American journal of political science, 58 (4), 919–935.

- Gavin, F.J., 2001. The Myth of flexible response: United States strategy in Europe during the 1960s. The international history review, 23 (4), 847–875.

- Gavin, F.J., 2015. Strategies of inhibition: U.S. grand strategy, the nuclear revolution, and nonproliferation. International security, 40 (1), 9–46.

- Gerzhoy, G., 2015. Alliance coercion and nuclear restraint: How the United States thwarted West Germany's nuclear ambitions. International Security, 39 (4), 91–129.

- Gravelle, T.B., Reifler, J., and Scotto, T.J., 2017. The structure of foreign policy attitudes in transatlantic perspective: comparing the United States, United Kingdom, France and Germany. European journal of political research, 56 (4), 757–776.

- Haftendorn, H., 1996. NATO and the nuclear revolution: a crisis of credibility, 1966-1967. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Harnisch, S., 2006. International politics and constitution: the domestication of German security and European policy. Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft.

- van der Harst, J., 1997. Kernwapens? Geen bezwaar. Transaktie, 26 (4), 295–517.

- Higgins, A., 2020. U.S. rebuffs Putin bid to extend nuclear arms pact for a year. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/16/world/europe/putin-nuclear-new-start-treaty.html.

- von Hlatky, S., 2014. Transatlantic cooperation, alliance politics and extended deterrence: European perceptions of nuclear weapons. European security, 23 (1), 1–14.

- Horovitz, L., 2014. Why do they want American nukes? Central and Eastern European positions regarding US nonstrategic nuclear weapons. European security, 23 (1), 73–89.

- Jäger, T., et al., 2009. The salience of foreign affairs issues in the German Bundestag. Parliamentary Affairs, 62 (3), 418–437.

- Kabinetsreactie op AIV-adviesrapport., 2019. Kernwapens in een nieuwe geopolitieke werkelijkheid [Brief van de ministers van buitenlandse zaken en van defensie]. https://www.tweedekamer.nl/downloads/document?id=fb2b0d74-bbb3-4039-9fae-d5bbe764c341&title=Kabinetsreactie%20op%20AIV-adviesrapport%20%22Kernwapens%20in%20een%20nieuwe%20geopolitieke%20werkelijkheid%22.pdf.

- Kristensen, H.M., and Korda, M., 2020. United States nuclear forces, 2020. Bulletin of the atomic scientists, 76 (1), 46–60.

- Kroenig, M., 2018. A strategy for deterring Russian de-escalation strikes. Atlantic Council. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Nuclear_Strategy_WEB.pdf.

- Lanoszka, A., 2019. Nuclear blackmail and nuclear balance in the Baltic region. Scandinavian journal of military studies, 2 (1), 84–94.

- Lieber, K.A., and Press, D.G., 2020. The myth of the nuclear revolution: power politics in the atomic age. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- McCrisken, T., and Downman, M., 2019. “Peace through strength”: Europe and NATO deterrence beyond the US nuclear posture review. International affairs, 95 (2), 277–295.

- Meier, O. 2016. Germany and the role of nuclear weapon: between prohibition and revival. SWP Comments. https://www.swp-berlin.org/fileadmin/contents/products/comments/2016C02_mro.pdf.

- Meier, O., 2020a. German politicians renew nuclear basing debate. Arms Control Today. https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2020-06/news/german-politicians-renew-nuclear-basing-debate

- Meier, O., 2020b. Why Germany won’t build its own nuclear weapons and remains skeptical of a Eurodeterrent. Bulletin of the atomic scientists, 76 (2), 76–84.

- Meier, O., 2021. Debating the withdrawal of US nuclear weapons from Europe: what Germany expects from russia. Vestnik of Saint Petersburg University. International relations, 14 (1), 82–96.

- Memorandum of Conversation., 1961. PRESIDENT’S VISIT, Paris, May 31-June 2, 1961. Foreign Relations of the United States, 1961–1963, Volume XIV, Berlin Crisis, 1961–1962. https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1961-63v14/d30.

- Monath, H., 2020. Maas reagiert auf Mützenichs Atomwaffen-Forderung: „Unsere Außen- und Sicherheitspolitik darf nie ein deutscher Sonderweg sein“. Der Tagesspiegel. https://www.tagesspiegel.de/politik/maas-reagiert-auf-muetzenichs-atomwaffen-forderung-unsere-aussen-und-sicherheitspolitik-darf-nie-ein-deutscher-sonderweg-sein/25794166.html.

- Müller, H., and Risse-Kappen, T., 1987. Origins of estrangement: the peace movement and the changed image of America in West Germany. International security, 12 (1), 52–88.

- Nuti, L., 2010. Negotiating with the enemy and having problems with the allies: The impact of the Non-Proliferation Treaty on transatlantic relations. In: J.M. Hanhimäki, G.-H. Soutou, and B. Germond, eds. The Routledge handbook of transatlantic security. London: Routledge, 89–102.

- Oliker, O., and Baklitskiy, A., 2018. The nuclear posture review and Russian “De-Escalation”: a dangerous solution to a nonexistent problem. War on the Rocks. https://warontherocks.com/2018/02/nuclear-posture-review-russian-de-escalation-dangerous-solution-nonexistent-problem/.

- Paul, T.V., 2009. The tradition of non-use of nuclear weapons. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Pelopidas, B., 2015. A bet portrayed as a certainty: reassessing the added deterrent value of nuclear weapons. In: J. Goodby and G. Shultz, eds. The war that must never be fought. Dilemmas of nuclear deterrence. Stanford: Hoover Press, 5–55.

- Pelopidas, B., 2019. Europeans facing nuclear weapons challenges: what do they know? What do they want? Vienna Center for Disarmament and Non-Proliferation. https://vcdnp.org/european-facing-nuclear-weapons-challenges-what-do-they-know-what-do-they-want/

- Pelopidas, B., and Egeland, K., 2020. What Europeans believe about Hiroshima and Nagasaki – and why it matters. Bulletin of Atomic Scientists. https://thebulletin.org/2020/08/what-europeans-believe-about-hiroshima-and-nagasaki-and-why-it-matters/.

- Pelopidas, B., and Fialho, F.M., 2019. Democracy, political vulnerability and nuclear weapons: reassessing the case for guardianship and popular attitudes towards nuclear weapons in Europe. Paper presented at the ISA Annual Conference, Toronto.

- Pifer, S., 2021. Where next on nuclear arms control? Brown journal of world affairs, 27 (1), 231–245.

- Pilat, J.F., 2016. A reversal of fortunes? Extended deterrence and assurance in Europe and East Asia. Journal of strategic studies, 39 (4), 580–591.

- Powell, R., 1990. Nuclear deterrence theory: the search for credibility. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Press, D.G., Sagan, S.D., and Valentino, B.A., 2013. Atomic aversion: experimental evidence on taboos, traditions, and the non-use of nuclear weapons. American political science review, 107 (1), 188–206.

- Rathbun, B.C., and Stein, R., 2020. Greater goods: morality and attitudes toward the use of nuclear weapons. Journal of conflict resolution, 64 (5), 787–816.

- Raunio, T., and Wagner, W., 2017. Towards parliamentarisation of foreign and security policy? West European politics, 40 (1), 1–19.fa

- Risse-Kappen, T., 1983. Déjà Vu: deployment of nuclear weapons in West Germany historical controversies. Bulletin of peace proposals, 14 (4), 327–336.

- Rosenberg, D.A., 1983. The origins of overkill: nuclear weapons and American strategy 1945-1960. International security, 7 (4), 3–71.

- Rudolf, P., 2020. Deutschland, die Nato und die nukleare Abschreckung SWP-Studie 2020/S. https://www.swp-berlin.org/10.18449/2020S11/.

- Sagan, S.D., 2004. Realist perspectives on ethical norms and weapons of mass destruction. In: S. H. Hashimi and S. P. Lee, eds. Ethics and weapons of mass destruction: religious and secular perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 73–95.

- Sagan, S.D., and Valentino, B.A., 2017. Revisiting Hiroshima in Iran: what Americans really think about using nuclear weapons and killing noncombatants. International security, 42 (1), 41–79.

- Scarry, E., 2014. Thermonuclear monarchy: choosing between democracy and doom. New York & London: WW Norton.

- Schelling, T.C., 1960. The strategy of conflict. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Schelling, T.C., 1966. Arms and influence. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Schelling, T.C., and Halperin, M.H., 1961. Strategy and arms control. New York: The Twentieth Century Fund.

- Sechser, T.S., 2016. Sharing the bomb: how foreign nuclear deployments shape nonproliferation and deterrence. The nonproliferation review, 23 (3–4), 443–458.

- Smetana, M., 2018. A nuclear posture review for the third nuclear age. The Washington quarterly, 41 (3), 137–157.

- Smetana, M., and Vranka, M., 2021. How moral foundations shape public approval of nuclear, chemical, and conventional strikes: new evidence from experimental surveys. International interactions, 47 (2), 374–390.

- Smetana, M., Onderco, M., and Etienne, T., 2021. Do Germany and the Netherlands want to say goodbye to US nuclear weapons? Bulletin of the atomic scientists (forthcoming).

- Smetana, M., and Wunderlich, C., 2021. Forum: nonuse of nuclear weapons in world politics: toward the third generation of “nuclear taboo” research. International studies review.

- Snyder, G.H., 1984. The security dilemma in alliance politics. World politics, 36 (4), 461–495.

- Suchy, P., and Thayer, B.A., 2014. Weapons as political symbolism: the role of US tactical nuclear weapons in Europe. European security, 23 (4), 509–528.

- Tagesschau., 2020. Forderung von SPD-Fraktionschef: Streit über US-Atomwaffen in Deutschland. https://www.tagesschau.de/inland/nukleare-teilhabe-streit-101.html.

- Tannenwald, N., 2002. The nuclear taboo the United States and the non-use of nuclear weapons since 1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Tannenwald, N., 2021. Public support for using nuclear weapons on Muslims: a response to Sagan, Valentino, and press. International studies review.

- Ven Bruusgaard, K., 2016. Russian strategic deterrence. Survival, 58 (4), 7–26.

- Ven Bruusgaard, K., 2020. Russian nuclear strategy and conventional inferiority. Journal of Strategic Studies, 44 (1), 3–35.

- Volpe, T., and Kühn, U., 2017. Germany’s nuclear education: why a few elites are testing a taboo. The Washington quarterly, 40 (3), 7–27.

- Wagner, W., Peters, D., and Glahn, C., 2010. Parliamentary war powers around the world, 1989–2004. A new dataset [Occassional Paper No. 22]. Geneva: Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces.

- Wonka, A., and Rittberger, B., 2014. The ties that bind? Intra-party information exchanges of German MPs in EU multi-level politics. West European politics, 37 (3), 624–643.

- Woolf, A.F. 2021. Nonstrategic nuclear weapons. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/nuke/RL32572.pdf.

- Yost, D.S., 2011. The US debate on NATO nuclear deterrence. International affairs, 87 (6), 1401–1438.

- Zeit Online. 2020. SPD-Fraktionschef fordert Abzug von Atombomben in Deutschland. https://www.zeit.de/politik/deutschland/2020-05/atomwaffen-us-stationierung-deutschland-sicherheitsrisiko-ralf-muetzenich-spd.