?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The USA is one of the “geopolitical others” of the European Union. Different geopolitical worldviews and normative commitments, therefore, often clash when relations with the USA are at stake. Whereas most analyses focus on differences between EU member states and their foreign policy traditions, this paper examines to what extent and in what way politicisation is driven by party politics by studying roll call votes in the European Parliament (EP) between 2004 and 2019. We find evidence that transatlantic relations have become more politicised. We show that voting behaviour is influenced first and foremost by MEPs’ affiliation with one of the political groups, not by their nationality. Furthermore, we demonstrate that support for the USA follows a bell-curve where centrist political groups are most supportive of the USA and political groups at the far ends of the left/right spectrum are most critical. Policies towards the USA are also related to the “new politics” dimension that pits cosmopolitans against nationalists, but the correlation is weaker than the one with the traditional left/right dimension. We examine the arguments brought forward in support for political groups’ voting behaviour by analysing the parliamentary debates preceding key votes on EU-US relations.

Introduction

A growing body of research has been debating whether the foreign policy of the European Union (EU) has become more politicised (see, among others, Costa Citation2019, Hegemann and Schneckener Citation2019, Neuhold and Rosén Citation2019, Biedenkopf et al. Citation2021). This paper contributes to this debate by examining the politics in the 6th, 7th and 8th European Parliament (EP) towards one of the EU’s principal “geopolitical others”: the USA. The EU and the USA are each other’s most important trading partners. At the same time, many, but not all EU member states, share a mutual defence commitment with the USA by common membership in NATO. Taken together, transatlantic relations are characterised by “intense interdependences” (Dominguez and Lafrance Citation2020, p. 1) as well as by differing member state policies, especially in security and defence policy (see the contributions in Joly and Haesebrouck Citation2021).

The Parliament is a particularly interesting institution for the study of politicisation because in contrast to the Commission or the (European) Council, it represents the full spectrum of political views in the EU. Moreover, the positions of members of the European Parliament (MEP) are influenced by their nationality as well as by their affiliation with a transnational ideology, institutionalised by membership in one of the political groups. Studying MEPs’ voting behaviour over a period of 15 years can thus help answer a series of questions that are relevant for understanding politicisation of transatlantic relations. First, on the level of the Parliament as a whole, we can examine whether votes on transatlantic relations have become politicised over time. Second, we can analyse whether MEPs vote along national or ideological lines and to what extent political groups have coherent policy positions. Although politicisation can take on other forms as well, distinct policy alternatives by political groups have been considered as an important indicator of politicisation, especially when the distance between these alternatives increases (Lefkofridi and Katsanidou Citation2018, Biedenkopf et al. Citation2021). Third, and finally, roll call votes reveal the underlying “grammar” of contestation. Specifically, we explore the explanatory weight of both the traditional left/right dimension and a “new politics” dimension that pits green/alternative/libertarian parties against traditionalist/authoritarian/nationalist ones (Hooghe et al. Citation2002).

In the next section, we discuss the state-of-the-art and formulate five propositions that structure the subsequent analyses. We then introduce our methodology and present the results of our analysis. We find support for the notion that there is a recent trend towards increasing levels of politicisation. Our analyses suggest that contestation is structured along ideological, not intergovernmental lines and that political groups – with the exception of the Eurosceptic right – are coherent in occupying a distinct position on transatlantic relations. Finally, we find that the political space is first and foremost structured by the traditional left/right dimension. A new politics dimension is also discernible but its impact on the political space has been weaker.

Theorising politics on transatlantic relations in the European Parliament

Our first proposition focuses on levels of politicisation over time. By and large, EU-US relations have had a relatively low level of conflict (Dominguez and Lafrance Citation2020, p. 1). Some studies of European policies towards the USA – and external relations more broadly – assume that policies are driven by commonly shared European norms and values (Manners Citation2002). The clear majority of post-Second World War US presidents have displayed solid support for European integration, the notable exception being the presidency of Donald Trump. Divisions over the 2003 Iraq War (Mello Citation2012) and over the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) (De Bièvre Citation2018) likewise suggest that policies towards the USA have become more politicised. However, such developments are potentially linked to the higher levels of politicisation of the EU as a whole, including the gradual deepening and diversification of its foreign and security policies. The more the decisions of the EU matter, both inside and outside of its borders, the more we should expect contestation related to those decisions (Zürn Citation2014). Also the EP is more involved in the EU’s external relations: it enjoys after the Lisbon Treaty substantial legislative rights in international trade and international agreements, and through its budgetary and legislative powers, MEPs can also wield at least indirect influence in Common Foreign and Security Policy / Common Security and Defence Policy (CFSP/CSDP). Furthermore, while the clear majority of MEPs have always been pro-integrationist, ideological diversity inside the Parliament has increased due to enlargements and the politicisation of integration, with various Eurosceptical voices becoming gradually more numerous in the institution. This diversity should impact all votes, including those on EU-US relations. Our data do not allow the tracing of levels of politicisation since the first direct EP elections in 1979, but we cover a period of 15 years, spanning the 6th, 7th and 8th legislative terms between 2004 and 2019. Our first proposition therefore reads as follows:

Proposition 1: Relations with the USA have become more politicized over time.

Most studies that question a common European interest point to the diversity of national interests and traditions amongst member states (see, among many others, Lundestad Citation2008). The distinction between “atlanticist” and “Europeanist” member states has a long tradition, and has been used to explain intra-European conflict over transatlantic relations. Although we do not discard the prevalence of political conflict between member states, we add another dimension by assuming that such national interests are politicised and contested domestically. Although the degree of politicisation over external relations is often lower than over issues of domestic policies (Kupchan and Trubowitz Citation2007, Wagner et al. Citation2018, p. 547, Wagner Citation2020), the “politics stops at the water’s edge” idiom is deceptive as it glosses over the variety of views that exist within states and often transcend state boundaries.

Instead of studying exclusively figurations of interests amongst member states, this paper focuses on the party politics of EU-US relations. In contrast to an intergovernmental approach, a party politics perspective not only captures those social forces that are represented in national governments but the full spectrum of ideas and positions within European societies. Understanding the positions of both governing and opposition parties towards the USA, one of the EU’s principal “geopolitical others”, provides a more nuanced picture of the politics of EU external relations and may also contribute to anticipating future developments in European foreign policy as a result of changing power relations between the major political groups.

Studies of voting behaviour in the European Parliament find that MEPs’ voting behaviour is driven by their affiliation with one of the political groups,Footnote1 rather than with one of the national delegations (Hix et al. Citation2007). One reason for individual MEPs and national parties to vote with their group most of the time is policy influence. Cohesive action is essential for the achievement of a group’s objectives, and cooperative behaviour within groups helps individual MEPs to pursue their own goals. As the Parliament has acquired more legislative powers, party groups thus have a stronger incentive and need to act cohesively.

Another explanation focuses on the institutionalisation of the political groups. The groups of the centre-right Christian democrats and conservatives, social democrats, and liberals have existed in the chamber since the 1950s, with the groups of the greens (including the regionalists) and the radical left also displaying longevity and stability. The conservative and Eurosceptical groups have been much less stable in terms of the composition and names of the groups. The political groups have thus decades of experience from building unitary group positions and from reaching compromises in the committees and plenary of the Parliament. Moreover, given the enormous number of amendments and final resolutions voted upon in plenary sessions, the voting cues provided by groups and particularly by group members in the responsible EP committee are an essential source of guidance for MEPs (Ringe Citation2010).

Raunio and Wagner (Citation2020b, Citation2021) show that external relations are no exemption to the general findings about plenary voting behaviour: when voting on foreign affairs, trade or development policy, the cohesion of the political groups is much higher than the cohesion of national delegations. The cohesion of political groups in votes on EU’s external relations is essentially the same as in the totality of votes held in the plenary. Our second proposition reads:

Proposition 2: MEPs’ voting behaviour in votes on EU-US relations is first and foremost influenced by their affiliation to a political group, rather than to a national delegation. We therefore expect cohesion of political groups to be higher than cohesion of national delegations.

To further understand politicisation and polarisation in the Parliament, we explore what accounts for differences in group cohesion. Group size and national fractionalisation have been discussed as two group characteristics that impact on its cohesion (Raunio Citation1997, Hix et al. Citation2007, pp. 95–101): the larger a group is, the more likely it is to influence policy outcomes, and these increased stakes in votes come with a strong incentive to vote cohesively. In contrast, the higher the national fractionalisation or diversity of a group, i.e. the more parties of roughly equal size are members of the group, the bigger the collective action problems in agreeing on a common position and the lower the expected coherence. Hix et al. also tested for ideological diversity with a view to parties’ positions on the left/right dimension but did not find this factor to be relevant. We discuss these factors to establish to what extent differences in political groups’ coherence can be explained by these more formal characteristics and to what extent they point to genuine political disagreements over transatlantic relations. Our third proposition is phrased as a null-hypothesis:

Proposition 3: Political groups’ voting cohesion in votes on EU-US relations does not differ systematically along the left/right axis.

Our final two propositions analyse the structure of the political space in the European Parliament in transatlantic relations. We are thus interested in the dividing lines that juxtapose supporters and opponents of an US-friendly EU policy. The most firmly established political cleavage is of course the left/right dimension, with the structure of the EP party system based on the main party families found in the EU member states. However, beginning in the 1960s, the satisfaction of sustenance needs for increasingly large parts of the population (Inglehart Citation1977), the expansion of secondary and higher education and “an information explosion through the mass media” (Dalton Citation1984, p. 265) has created space for “postmaterialist” concerns such as “as protection of the environment, the quality of life, the role of women, the redefinition of morality, drug usage, and broader public participation in both political and non-political decision-making” (Inglehart Citation1977, p. 13). These concerns were articulated by new social movements and “green” parties that entered the parliaments in Western European democracies in the 1980s. Their political success, however, provoked a reaction among older and less secure strata who feel threatened by the erosion of traditional values (Norris and Inglehart Citation2019). This cultural backlash, spurred by growing economic inequality and by immigration, contributed to the emergence of xenophobic and authoritarian parties at the far right.

Taken together, the emergence of green parties, on the one hand, and far right parties, on the other hand, gave rise to a “new politics dimension” that has not been absorbed by the traditional left/right dimension but is orthogonal to it (for an excellent recent overview see Ford and Jennings Citation2020). Zürn and de Wilde argue that

the process of globalization leads to a new cleavage between those wanting to further “integrate” beyond the national state and allow border crossings of goods, people, values, etc. on the one hand, and those advocating a closure or “demarcation” of the state on the other hand. (Zürn and De Wilde Citation2016, p. 280)

But how would we expect these two main dimensions of conflict – the left/right and the “new politics” dimensions – to manifest themselves in foreign and security policy, or in the external relations of the EU? The challenge lies in the diversity of foreign policy, as the range of items covers a lot of ground from condemnations of human rights violations in distant countries to trade and development policy, military operations, and relations with neighbouring countries. This implies potentially significant differences in party-political contestation between individual policy questions. Noël and Thérien (Citation2008) and Rathbun (Citation2004, Citation2007) argued that in global politics the difference between parties of the left and right stems from different core values, such as hierarchy and equality, with the left advocating more egalitarian policies both in terms of economy and security that are more effectively reached through stronger international rules and institutions. However, more in-depth studies show that such ideological worldviews tend to be moderated by national contexts. Two prominent examples are Rathbun (Citation2004) and Hofmann (Citation2013). Both analysed British, French, and German parties, showing how their responses to conflicts in the Balkans or the development of CFSP/CSDP were shaped by factors such as their own historical trajectories, government-opposition dynamics or electoral considerations.

Most of the empirical studies have focused on the use of force, with research on the US and comparative papers mainly confirming that “hawks” are more often found among right-leaning legislators and “doves” on the left (for overviews of the literature, see Raunio and Wagner Citation2020a, Wagner Citation2020, Hofmann and Martill Citation2021). Party positions in international trade and development aid are also linked to the left-right dimension, with preferences explained by the core values and constituents of the parties. Centre-right parties are more supportive of free trade than leftist parties that are more in favour of foreign aid and willing to use protectionist measures to safeguard social, consumer, industrial or environmental interests (e.g. Thérien and Noel Citation2000, Hiscox Citation2002, Milner and Judkins Citation2004, Milner and Tingley Citation2015, Dietrich et al. Citation2020).

Recently scholars have begun to incorporate the “new politics” dimension into their models. Studies on military interventions have shown that the left-right dimension and the “new politics” dimension are best understood as a bell-curve, rather than a linear function, with support for the missions strongest in the centre of these dimensions. The evidence so far is rather thin, but it indicates that the “new politics” dimension holds less explanatory power than the left/right axis (see Cicchi et al. Citation2020, Haesebrouck and Mello Citation2020, Wagner Citation2020). At the conservative end of the “new politics” dimension are populist or nationalist challenger parties that contest the expansion of international authority (Ecker-Ehrhardt Citation2014, Norris and Inglehart Citation2019). The rise of such parties may destabilise established patterns of international trade, regional integration, and security cooperation – but can also result in stronger defence of internationalism by centrist parties.

Previous research on the EP has underlined the importance of the left/right dimension. This means that any two political groups are more likely to vote the same way, the closer they are to another on this socioeconomic dimension. The anti/pro-integration dimension, strongly linked to the “new politics” dimension, constitutes the secondary axis of competition in the chamber, particularly since the start of the euro crisis (Otjes and Van der Veer Citation2016, Blumenau and Lauderdale Citation2018). However, procedural aspects and policy incentives also matter. For many issues, there is an absolute majority requirement (50% plus one MEP) that facilitates cooperation between the two main groups, EPP and S&D, which between them controlled around two-thirds of the seats until the 2014 elections. Cooperation between the main centrist groups is also influenced by inter-institutional considerations, because representatives from these same party families are in the clear majority in the Council and the Commission (Kreppel Citation2002). And often the Parliament tries to reach high level of institutional unity in the hope of its voice being heard better. In fact, the clear majority of votes are passed with large super majorities, constituting thus the so-called “hurrah votes” (Bowler and McElroy Citation2015).

Also EU-US relations cover a lot of ground, although votes on TTIP constitute a large share of our data set (see supplemental data online). Both the left/right and the “new politics” dimensions can be linked to EU policy towards the USA. Chryssogelos argues that partisan views on the USA are linked to those on Russia and form an “Atlanticism-Europeanism’ cleavage”. While EPP members are “historically suspicious of Russia’s role in European security and think that Europe has to stand side by side with the US” (Chryssogelos Citation2015, p. 230), S&D was sympathetic to détente during the Cold War and has supported “European unity in foreign policy, both as a complement and a counterbalance to the US when needed” (Chryssogelos Citation2015, p. 232). Chryssogelos generally finds that “atlanticism is receding as one moves from right to left” (Citation2015, p. 234). However, the three core party families, the EPP, S&D, and ALDE groups, all

see the presence of NATO in Europe as necessary, acknowledge that relations and ties with the US are very important, accept that Europe has to promote some distinct values and norms in the international scene (human rights, multilateralism), understand that dialogue with Russia is difficult but necessary, and promote a more effective representation of the EU internationally. This set of common assumptions creates a very narrow space within which these party families differ. (Chryssogelos Citation2015, p. 234)

Proposition 4: The centrist political groups display US-friendly voting behaviour, with opposition coming mainly from the left and far right groups.

Proposition 5: The left-right dimension structures the political space more strongly in votes on EU-US relations than the “new politics” dimension.

Data and methods

To assess whether and in what way the EU’s policies towards the USA have been contested amongst political parties in the European Parliament, we study roll call votes from the 6th, 7th and 8th legislative terms, as provided by votewatch.eu. In contrast to party manifestos or expert surveys, roll call votes reveal the preferences of parliamentarians on actual policy issues. While other parliaments rarely record votes (Saalfeld Citation1995), the EP does so rather often. In addition to final votes on decisions made on the basis of a report,Footnote2 votes are recorded at the request of a political group or a respective number of MEPs. Political groups can also request to have split the vote, i.e. to have a separate vote on individual provisions of the respective motion. Recorded votes have been criticised for not being representative because the very act of recording indicates that the issue in question is controversial (Carrubba et al. Citation2008). This bias, however, remains constant across parliaments and issues, and we can, therefore, make inferences about differences over time and across issues, groups and delegations.

In the 2004–2019 Parliament, MEPs voted 178 times on motions (or provisions thereof) on the USA (see ). As the list of votes in the online supplemental data shows, the large number of votes in the 8th EP results from a large number of proposed amendments to a resolution on TTIP. This underlines the salience – and thus politicisation – of TTIP in European politics.

Table 1. Overview of the number of votes under study.

For each of the 178 votes, we calculated the Agreement Index (AI), developed by Hix et al. (Citation2007, pp. 91–95), for the Parliament as a whole and for every political group. The Agreement Index draws on the often-used index of Rice (Citation1928), but differs from it by taking into account abstentions as MEPs have three voting options (Yes, No, Abstain).Footnote3 The AI ranges from 0 to 1. When all party group members vote the same way, the score is 1. If the party group is completely divided, with a third of the members voting “yes”, a third voting “no” and a final third abstaining, the score is 0. The lower the AI, the higher the level of polarisation. The Agreement Index is difficult to interpret in absolute terms because “hurrah votes” may inflate the level of agreement. In the subsequent analyses we, therefore, focus on changes and development over time and across issues and political groups.

To assess the positions of the political groups towards the USA and get a sense of their friendliness/accommodationism towards the USA, we devised a “Support and Cooperation Index” (SCI). All EP 7 and EP 8 votes were coded as favourable, unfavourable or indeterminate towards the USA.Footnote4 12 motions were favourable, 97 were unfavourable and 25 were indeterminate. Voting “yes” on a favourable motion and voting “no” on an unfavourable motion indicate a positive attitude towards the country in question. Similarly, a “yes” vote on an unfavourable motion and a “no” vote on a favourable one suggest a negative stance towards the USA. The SCI was subsequently calculated as follows: for a favourable motion, the share of “yes” votes is divided by the sum of all votes. In the case of an unfavourable motion, the share of “no” votes is divided by the total number of votes. Possible values of the index range from 0 to 1, with 0 indicating the lowest level of support and cooperation. Votewatch provides voting data on the level of party groups for the 7th and the 8th EP and on the level of national parties for the 8th EP.

To explore the political space on transatlantic relations, we plot parties’ SCI scores against their position on the left/right and on the “new politics” dimensions and we calculate correlation coefficients for linear and curvilinear relationships between them. We use data from the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES, see Bakker et al. Citation2020) to estimate positions on the left/right dimension (“rile”) and the “new politics” dimension (“gal/tan”).Footnote5 Our analyses follow the availability of data from votewatch (see above): we plot and calculate coefficients for national party-level data for the 8th EP. For the 6th and 7th EP, we use weighted averages of rile and gal/tan values for the political groups.

The Support and Cooperation Index provides a straightforward measure of a party’s position towards the USA. However, it remains silent about the underlying reasons for the position taken. We, therefore, selected two key votes from the 6th and 8th Parliament and examined the corresponding debates in the plenary. We looked into the debates on the state of EU-US relations in March 2009 and in September 2018.

Findings

Roll call votes

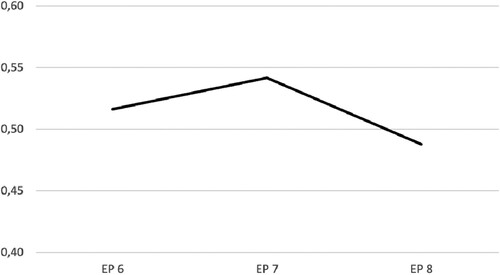

We first examine the overall level of politicisation for the parliament as a whole (). While we do not have average cohesion scores for all external relations votes in the 8th EP, we can compare the agreement indices for votes on transatlantic relations in the 6th and 7th EP with those for all external relations votes, as calculated by Raunio and Wagner (Citation2020b). This comparison shows that votes on relations with the USA were more politicised than external relations in general.Footnote6 Furthermore, shows that politicisation was, on average, highest in the 8th EP (2014–2019). Although this is in line with our first proposition, this finding needs to be treated with caution for two reasons. First of all, also clearly shows that there is no linear trend towards politicisation as the level of politicisation in EP 7 (2009–2014) is lower than in EP6 (2004–2009). Moreover, levels of politicisation, in part, result from the issues on the agenda in a given time period. In this context it is interesting to note that the high level of politicisation in the 8th EP was not driven by particularly polarised votes on TTIP but by a set of votes on the use of torture by the CIA in 2016.

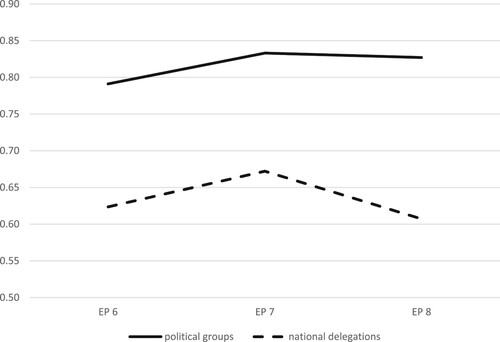

Our data also confirm our second proposition. As demonstrated in , political groups have, on average, a higher agreement index than national delegations. This is consistently the case across the three legislative terms for votes on the USA.

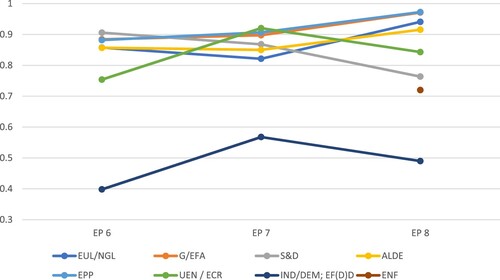

shows the average AI of the political groups in the 6th, 7th and 8th Parliament for votes on (relations with) the USA. The figure by and large confirms our third proposition that political groups’ positions on the left/right axis do not have a systematic impact on voting coherence. The outlier is clearly the Eurosceptic right.

reports the size (i.e. the share of its MEPs in relation to the overall number of MEPs), fractionalisation (following the formula in Hix et al. Citation2007, p. 97) and internal ideological diversity for each of the political groups.Footnote7

Table 2. Political groups’ size, fractionalisation and internal ideological diversity.

Interestingly, IND/DEM-EFD-EFDD’s fractionalisation was always lower than average, so there is no support for the notion that a large number of parties (or the absence of a hegemonic one) can account for the low coherence. At the same time, IND/DEM-EFD-EFDD was always amongst the smallest party groups. Combined with its position at the far end of the left/right spectrum, the unlikeliness of influencing the final outcome may well contribute to the low coherence in voting. also shows that IND/DEM-EFD-EFDD scores high on ideological diversity, especially in the 8th Parliament when both UKIP (9.14 on CHES’ 10-point left/right-scale) and the Italian Five Star Movement (4.66 on the same scale) were both in the group. The exceptionally low degree of agreement over policies towards the USA may thus result from genuine ideological differences. This finding confirms the qualitative study by McDonnell and Werner about populist parties in the EP. They describe the EFDD as a “marriage of convenience” (McDonnell and Werner Citation2020, p. 108), with a deliberate absence of any group discipline and report that the Five Star Movement, in contrast to UKIP, aimed at reforming the EU and fully engaging in the workings of parliament (McDonnell and Werner Citation2020, p. 113).

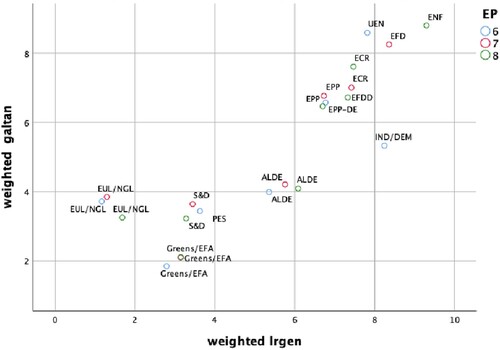

Finally, we explore the structure of the political space. shows the political space in the 6th, 7th and 8th Parliament on the basis of CHES data. Groups’ positions result from the weighted averages of two variables in the CHES surveys: the left/right dimension and the so-called gal/tan dimension that juxtaposes “green/alternative/libertarian parties” with “traditionalist/authoritarian/nationalist” ones.

shows that most political groups occupy remarkably stable positions over the course of the three legislative terms. Moreover, the figure shows that the left/right and the “new politics” dimensions overlap to a significant extent. Tellingly, one of the largest changes in position, between EFD in the 7th and EFDD in the 8th term, was a move towards the centre on both dimensions. However, especially at the far ends, the rank order of political groups differs: Whereas EUL/NGL is the far end of the left/right scale, the Greens/EFA are the far end of the gal/tan dimension. On the left/right scale, the Greens are in-between EUL/NGL to their left and S&D to their right, whereas on the gal/tan-scale, S&D and EUL/NGL occupy almost identical positions. On the opposite end of the two dimensions, ENF occupies the most extreme position. In contrast to the 7th EP, the position of the EFD-EFDD on the left/right dimension has become less extreme and differences with ECR, therefore, almost disappear. On the gal/tan dimension, ECR moves towards the tan-end and positions itself in-between EFD-EFDD and ENF.

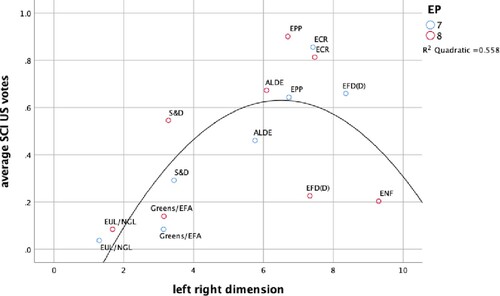

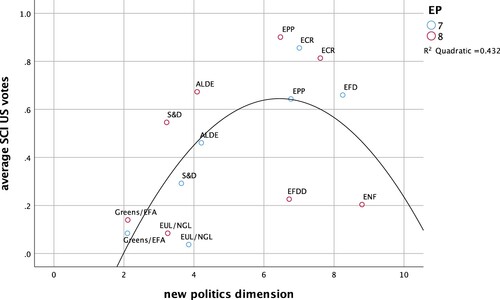

and plot the average Support and Cooperation Index against political groups’ positions on the left/right dimension () and the “new politics” dimension () in the 7th and 8th Parliament, respectively.Footnote8

Figure 5. Political groups’ support and Cooperation index plotted against their position on the left/right dimension.

Figure 6. Political groups’ support and Cooperation index plotted against their position on the new politics’ dimension.

shows a skewed bell curve with sympathies for the USA lowest in the EUL/NGL and the Greens and highest among Christian Democrats and Conservatives. The far right ENF group scores low again on the SCI. The bell curve has a high r2 (0.56; p < 0.01). In contrast, the linear function (not shown) has a lower explanatory value (r2 = 0.36; p < 0.05).

plots political groups’ SCI against their position on the “new politics” dimension. Again, the resulting curve is bell-formedFootnote9 and statistically significant (p < 0.05). However, the variation explained by a group’s gal/tan value is lower than the one explained by its left/right position. Although parties’ policies towards the USA correlate with their degree of post-materialism (although not in a linear but curvilinear way), the left/right axis remains the best predictor for positions on transatlantic relations.

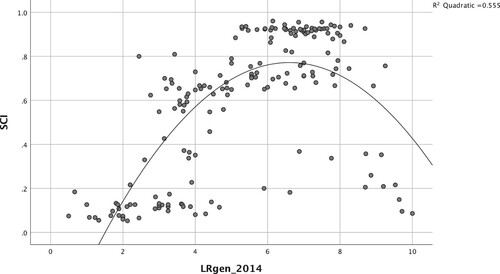

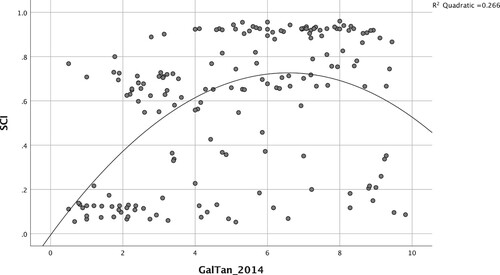

Because votewatch.eu provides for EP 8 voting data on the level of national parties, we have also plotted the SCI scores of 179 national parties against their positions on the left/right () and gal/tan dimensions (). Our findings confirm what we had found on the level of political groups: the relationship between both political dimensions and the support for the USA is curvilinear, rather than linear with support lowest on the far left and highest at the centre-right. The left/right dimension has a higher explanatory power than the new politics dimension (r2 is 0.56 for the curvilinear left/right dimension, compared to 0.27 for the curvilinear gal/tan dimension).Footnote10

Based on our analyses on the levels of national parties and political groups, we can thus largely confirm our fourth and fifth propositions. The left/right dimension is the best guide to transatlantic politics in the European Parliament. Support for the United States is strongest among the centrist party groups, peaking at the centre-right, and weakest particularly among the far left MEPs.

Plenary debates

To obtain a more in-depth understanding of the party groups’ positions towards the (EU’s relationship with) the USA, we considered two debates in which resolutions on the state of the transatlantic relationship were discussed. These debates were held in the 6th and 8th parliamentary terms, and both consider EU-US relations in light of the American presidency at the time. Firstly, we examine a debate held on the 25th of March 2009. The resolution under consideration in this debate (2008/2199(INI)) looks at the election of President Barack Obama, describing this as an opportunity to re-strengthen the relationship between the USA and the EU.Footnote11 While it states that there have been “some differences in the last years” (p. 2), the foundation of the transatlantic partnership is said to “remain strong”. The resolution largely emphasises the importance of the relationship and expresses an ambition to strengthen it in areas such as foreign, economic, cultural and security policy, transatlantic parliamentary dialogue, space programmes and energy relations. The second debate we study was held on the 12th of September 2018, which centres around a resolution on the transatlantic relationship in light of the Trump presidency (2017/2271(INI)).Footnote12 While the report contains elements of open criticism of the Trump administration, it strongly emphasises the importance of the transatlantic relationship and need to strengthen it further in the future. Compared to the resolution from 2009, it expresses more criticism towards the USA and its president.

These debates were selected because they cover the transatlantic relationship in general and a broad range of issues. The analysis serves to illustrate the findings from the previously discussed quantitative analyses. In particular, it provides more insight into political groups’ scores on the Support and Cooperation Index, and what their (lack of) “support” and “cooperation” entails. The findings from both debates are discussed per political group, moving along the political scale from the left to the right.

EUL/NGL took a clear critical stance towards both the 2009 and the 2018 resolutions. In contrast to other groups, members of the EUL/NGL group did not speak positively about the importance or future of the transatlantic relationship, but rather criticised both US policy and the EU’s stance towards the USA. In both the 2009 and the 2018 debates, MEPs from the group criticised the resolutions for not addressing and condemning the US war in Afghanistan. In 2018, Helmut Scholz (Germany, Die Linke) and Sofia Sakorafa (Greece, MeRA25) denounced the EU’s dependence on the USA. They argued that the EU has been dominated by the USA, ceasing to be a “partner”, and that the EU should take a more independent stance on foreign policy issues. The critical stance speakers from EUL/NGL took in the debates confer an image very similar to the one presented by the SCI data, which showed that EUL/NGL had the lowest level of support and cooperation towards the USA out of all party groups, scoring only 0.08 (all reported SCI values in this section are from EP8).

According to the SCI data, the second most unsupportive and uncooperative group was Greens/EFA, which scored 0.14. In the 2009 debate, this critical stance is confirmed by the contribution of the group’s Joost Lagendijk (Netherlands, GroenLinks) whose speaking time was mostly filled with criticism of US policy: not only did he call out US practices on torture and rendition, he also described the Americans’ refusal to cooperate with the International Criminal Court as “shameful”. Nevertheless, while Lagendijk described previous transatlantic relations under the George W. Bush presidency as “badly damaged”, he described the election of president Obama as an opportunity for change and improved relations. The contribution from the Greens/EFA group to the 2018 debate continues on this more positive note. Although Reinhard Bütikofer (Germany, Bündnis 90/Die Grünen), who spoke on behalf of his group, argued that the EU should “enlarge its partnerships beyond the West”, and that the transatlantic relationship needs redefinition, he also stressed that the relationship should be invested in. He ended on a proposal to “create a dialogue representative for the enhancement of our dialogue with our American friends” [24:11–24:20].

While members of the S&D stressed the importance of the transatlantic relationship, in both debates they did not shy away from criticising the partnership in its current form. MEPs from S&D recognised the good historical ties and shared values between the EU and the USA, and also argued that the EU should become more independent from the USA, defending its own interests and preventing an unbalanced relationship. In 2009, S&D speakers expressed clearly that the election of President Obama brought with it a renewed willingness to cooperate with the USA after “difficult relations” under the Bush presidency. For instance, Martí Grau i Segú (Spain, Partit dels Socialistes de Catalunya) argued that Obama is “on completely the same wavelength as Europe” in terms of political action. The Trump presidency was evaluated rather differently in 2018: President Trump is criticised and the transatlantic relationship is described as “strained” and “disturbed”. Nevertheless, all S&D speakers in 2018 agreed that the EU should continue cooperation and dialogue with the USA. The expressed support for good relations and continued cooperation with the USA, albeit not unconditional, seems to be consistent with the SCI data: the S&D group showed relatively supportive voting behaviour towards the USA, with a SCI score of 0.55.

Consistent with its SCI score of 0.67, speakers of the ALDE group emphasised the importance of the transatlantic relationship, while also expressing some critique of the USA and the EU’s dependence on the country. In the 2009 debate, ALDE members described the election of President Obama as an opportunity for deepened cooperation. In 2018, ALDE views the partnership as strained; Urmas Paet (Estonia, Eesti Reformierakond), who addressed the Parliament on behalf of his group, expressed regret at the unilateral actions from the USA with regard to foreign policy, emphasising a need for transatlantic cooperation on global conflict resolution. Despite ALDE’s support for cooperation and partnership with the USA, in both debates it is pointed out by speakers that the EU’s interests do not always fully align with those of the USA, and therefore the EU should strengthen its autonomy and stand more for its own interests.

The EPP scored 0.90 on the SCI and was found to have the highest SCI score of all political groups. This positive attitude towards the USA is reflected in the statements of the EPP’s members during both debates, in which virtually all speakers emphasised the importance of the transatlantic relationship, which was argued to be based on strong historical ties, shared values and common challenges, such as tensions with Russia. Many speakers from the EPP argued that the relationship needs to be strengthened, deepened and further institutionalised. While the group acknowledged that the EU-US relationship has become strained under the Trump presidency, its MEPs emphasised that the EU should work towards re-improvement of the relationship. This can be illustrated by a statement from Eduard Kukan (Slovakia, independent): “The current strain on transatlantic relations is hard to ignore, but it is important now to work together towards the de-escalation of tensions and to bring back certainty in transatlantic relations” [47:35–47:51]. Nevertheless, in both debates a few EPP speakers argue that the EU should become more independent from the USA, as the Union has its own, sometimes diverging interests which it must defend when necessary. In 2009, this argument was also linked to the Lisbon Treaty, which Elmar Brok (Germany, CDU) and Íñigo Méndez de Vigo (Spain, Partido Popular) connected to the ability of the EU to act and be a strong and independent actor in foreign policy. Additionally, in 2009 EPP MEPs from Romania and Bulgaria adopted a critical tone towards the USA for its requirement for citizens of some EU member states to acquire a visa to travel to the USA, which was called out as unfair policy.

Members of the conservative ECR group and its predecessor UEN expressed their support for a strong transatlantic relationship in both debates, in line with their high SCI score of 0.81. Its MEPs pointed to the necessity of cooperation with the USA, especially in the face of global challenges such as terrorism and tensions with Russia. ECR members paid attention to the strained nature of the transatlantic relationship under Trump’s presidency, but emphasised that the USA remains one of the EU’s “key allies” and the relationship needs to be invested in. As Charles Tannock (United Kingdom, Conservative Party) stated on behalf of ECR, “(…) there is an America beyond Trump and in dealing with his unorthodox approach, we must not allow this to overshadow the wider picture” [22:11–22:19]. In 2009, UEN also argued that the EU-US partnership should not be disturbed by differences of opinion. Whereas S&D and EPP argued that the EU should defend positions which diverge from the American stance, Konrad Szymański (Poland, Prawo i Sprawiedliwość) stated on behalf of UEN that the EU’s cooperation with the USA should be “pragmatic”. Therefore, MEPs should “exercise moderation” with advice on issues where positions might diverge, such as the International Criminal Court or the death sentence. At the same time, fellow UEN member Bogusław Rogalski (Poland, Naprzód Polsko) did criticise the American policy on visas.

The most surprising findings come from the ENF group and its predecessor IND/DEM. While ENF had a relatively low SCI of 0.20 towards the USA, in both the 2009 and the 2018 debate ENF and IND/DEM speakers were very positive about cooperation with the USA, which is said to be based on shared values and of “ultimate importance” to the EU. In contrast to other political groups, IND/DEM representative Bastiaan Belder (the Netherlands, ChristenUnie) did not argue in favour of a strong stance from the EU towards the USA: instead he argued that the EU must recognise that its role is “simply to support Washington”, because the EU needs the USA to a much greater extent than vice versa. In 2018, ENF representative Jean-Luc Schaffhauser (France, Rassemblement National) also took a clear pro-American stance, congratulating President Trump on his policy choices and ending his speech on “Vivent les États-Unis!” [26:58].

The ENF group is the only one where the arguments brought forward during the two debates deviate from the SCI. For all other political groups, MEPs’ speeches match the SCI scores: criticism is strongest at the far left and least pronounced at the centre-right. Where critique is voiced, it mostly concerns the US’ military interventions and its policies towards the liberal international order, as exemplified by the International Criminal Court.

Conclusion

Our analyses suggest that EU policies towards the USA are contested within the European Parliament. What is more, the 8th Parliament (2014–2019) reached the highest level of contestation among the three EPs we studied. More in-depth research is needed before any robust conclusions about overall trends of politicisation can be reached, and additional data from the first five electoral terms (1979–2004) would be a valuable addition to such an analysis. Our preliminary evidence suggests, however, that politicisation has been increasing over transatlantic relations.

Furthermore, our analyses show that the political space in the European Parliament is organised along party-political lines. The one exception is the Eurosceptic right which has a much higher degree of internal disagreement than the other political groups. The left/right dimension remains dominant in structuring the political space when it comes to transatlantic relations. What is important to note, however, is the curvilinear nature of the relationship between the left/right axis and US-friendly policies: opposition is strongest at the radical left and also present at the radical right. The centrist groups, the centre-right in particular, are the friendliest towards the USA. The “new politics” dimension is also correlated to policy positions on the USA but the correlation is weaker. It remains to be seen whether this dimension becomes more prominent in the future, but for the time being, the left/right dimension appears remarkably resilient in capturing the political space.

At the time of writing, the 9th European Parliament has been elected with Eurosceptical and nationalist parties as well as the Greens gaining at the expense of the two traditionally largest groups, the EPP and the Social Democrats. Our analyses suggest that this may change politics in the European Parliament towards a more US-critical position. However, at the same time the election of Joe Biden as the new US president should overall smoothen edges in transatlantic relations.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ben Crum for sharing data on the party-political composition of the 7th and 8th European Parliament, Lukas Nagel for the valuable assistance and the participants of the COST Action ENTER (EU Foreign Policy Facing New Realities) workshops “The determinants of EU Foreign Policy contestation” in Porto in July 2019 and “Contestation and politicization of EU foreign policy: New realities or same old?” in Vienna, 26/27 February 2020.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The number, names and composition of the political groups in the European Parliament changes frequently. The use of French as well as English acronyms can add to the confusion about them. Throughout this paper, we will refer to the groups by the English names and abbreviations used at the time. When we discuss a group in general, we will use the names and abbreviation used in EP 8. Because the Gaullist-dominated UEN and the British Conservatives-dominated ECR occupy comparable positions on the left/right axis between the Christian Democrats and the far right, we treat the UEN as a predecessor of the ECR. From left to right, the political groups we examine are the European United Left/Nordic Green Left (EUL/NGL), the Greens/European Free Alliance (Greens/EFA), the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D; previously Party of European Socialists), the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats in Europe (ALDE); the European People’s Party (EPP; previously European People’s Party-European Democrats (EPP-ED)); the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR; previously Union for Europe of the Nations (UEN)), Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy (EFDD; previously Independence/Democracy groups (IND/DEM) in EP 6 and Europe of Freedom and Democracy (EFD) in EP 7); and the Europe of Nations and Freedom (EFN).

2 Rules of Procedure, Rule No 179.

3 The precise formula is

4 We did not code EP6 votes because votewatch.eu provides links to the documents being voted on only for EP 7 and EP8.

5 According to the CHES codebook,

“Libertarian” or “postmaterialist” parties favor expanded personal freedoms, for example, access to abortion, active euthanasia, same-sex marriage, or greater democratic participation. “Traditional” or “authoritarian” parties often reject these ideas; they value order, tradition, and stability, and believe that the government should be a firm moral authority on social and cultural issues. (p. 14)

6 The AIs for all external relations votes were 0.65 (EP6) and 0.66 (EP7) whereas those for votes on the US were 0.52 (EP 6) and 0.54 (EP 7).

7 With the exception of the ENF group in the 8th Parliament, data always refer to the first session of the new parliament. Because the ENF group only formed later, calculations are made on the basis of 2018 data. We use the same formula for calculating ideological diversity as Hix et al., but we take the CHES data instead of the MARPOR data to measure a party’s position on the left/right dimension.

8 A group’s position on the left/right dimension (rile) results from the weighted average of all rile-values of the members of this group, i.e. the rile value multiplied by the share of seats within the political group.

9 The linear function is also statistically significant (p < 0.05) but has a lower r2 (0.28).

10 R2 is 0.33 for the linear left/right dimension and 0.17 for the linear gal/tan dimension. All correlations are statistically significant at the 0.005 level. In a further test, we correlated party positions on transatlantic relations with their position on European integration, as provided in the CHES data. However, the correlation is weak (r2 is 0.14 for the quadratic and for the linear model) and only the linear function is statistically significant. In addition, we calculated distinct SCI averages for the periods of the Obama and Trump administrations that overlapped with the 8th EP, uncovering a general trend of wavering support as the average SCI dropped from 0.58 during Obama’s term to 0.48 during Trump’s presidency.

11 The analysis is based on the official English minutes of the debate, which can be found here: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?type=CRE&reference=20090325&secondRef=ITEM-007&language=EN&ring=A6-2009-0114.

12 The analysis is based on a video recording of the debates with English interpretation of the speeches, as from December 2012 onwards, minutes of the debates are only recorded in the language they are conducted in. The video recording can be found here: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/CRE-8-2018-09-11-ITM-016_EN.html.

References

- Bakker, R., et al. 2020. 2019 chapel hill expert survey. Version 2019.1. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina. Available from: chesdata.eu

- Biedenkopf, K., Costa, O., and Gora, M., 2021. Shades of contestation and politicization on EU foreign policy. European security.

- Blumenau, J. and Lauderdale, B.E., 2018. Never let a good crisis go to waste: agenda setting and legislative voting in response to the EU crisis. The journal of politics, 80 (2), 462–478.

- Bowler, S. and McElroy, G., 2015. Political group cohesion and “hurrah” voting in the European Parliament. Journal of European public policy, 22 (9), 1355–1365.

- Carrubba, C., Gabel, M., and Hug, S., 2008. Legislative voting behavior, seen and unseen: a theory of roll-call vote selection. Legislative studies quarterly, 33 (4), 543–572.

- Chryssogelos, A.-S., 2015. Patterns of transnational partisan contestation of European foreign policy. European foreign affairs review, 20 (2), 227–246.

- Cicchi, L., Garzia, D., and Trechsel, A.H., 2020. Mapping parties’ positions on foreign and security issues in the EU, 2009–2014. Foreign policy analysis, 16 (4), 532–546.

- Costa, O., 2019. The politicization of EU external relations. Journal of European public policy, 26 (5), 790–802.

- Dalton, R.J., 1984. Cognitive mobilization and partisan dealignment in advanced industrial democracies. The Journal of politics, 46 (1), 264–284.

- De Bièvre, D., 2018. The paradox of weakness in European trade policy: contestation and resilience in CETA and TTIP negotiations. The international spectator, 53 (3), 70–85.

- Dietrich, S., Milner, H.V., and Slapin, J.B., 2020. From text to political positions on foreign aid: analysis of Aid mentions in party manifestos from 1960 to 2015. International studies quarterly, 64 (4), 980–990.

- Dominguez, R. and Lafrance, J.W., 2020. The United States and the European Union. Oxford research encyclopedia of politics. Available from: https://oxfordre.com/politics/view/https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228637-e-1125

- Ecker-Ehrhardt, M., 2014. Why parties politicise international institutions: on globalisation backlash and authority contestation. Review of international political economy, 21 (6), 1275–1312.

- Ford, R. and Jennings, W., 2020. The changing cleavage politics of Western Europe. Annual review of political science, 23, 295–314.

- Haesebrouck, T. and Mello, P.A., 2020. Patterns of political ideology and security policy. Foreign policy analysis, 16 (4), 565–586.

- Hegemann, H. and Schneckener, U., 2019. Politicising European security: from technocratic to contentious politics? European security, 28 (2), 133–152.

- Hiscox, M.J., 2002. International trade and political conflict: commerce, coalitions, and mobility. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Hix, S., Noury, A.G., and Roland, G., 2007. Democratic politics in the European Parliament. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hofmann, S.C., 2013. European security in NATO’s shadow: party ideologies and institution building. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hofmann, S. and Martill, B., 2021. The party scene: new directions for political party research in foreign policy analysis. International affairs, 97 (2), 305–322.

- Hooghe, L., Marks, G., and Wilson, C.J., 2002. Does left/right structure party positions on European integration? Comparative political studies, 35 (8), 965–989.

- Inglehart, R., 1977. The silent revolution: changing values and political styles Among Western publics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Jančić, D., 2017. TTIP and legislative-executive relations in EU trade policy. West European politics, 40 (1), 202–221.

- Joly, J. and Haesebrouck, T., eds., 2021. Foreign policy change in Europe since 1991. London: Palgrave-Macmillan.

- Kreppel, A., 2002. The European Parliament and supranational party system: a study in institutional development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kriesi, H., et al., 2012. Political conflict in Western Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kriesi, H., et al., 2008. West European politics in the age of globalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kupchan, C.A. and Trubowitz, P.L., 2007. Dead center: the demise of liberal internationalism in the United States. International security, 32 (2), 7–44.

- Lefkofridi, Z. and Katsanidou, A., 2018. A step closer to a transnational party system? Competition and coherence in the 2009 and 2014 European Parliament. Journal of common market studies, 56 (6), 1462–1482.

- Lundestad, G., 2008. Conclusion: the United States and Europe. Just another crisis? In: G. Lundestad, ed. Just another major crisis? The United States and Europe in the 2000s. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 298–320.

- Manners, I., 2002. Normative power Europe: a contradiction in terms? Journal of common market studies, 40 (2), 235–258.

- McDonnell, D. and Werner, A., 2020. International populism: the radical right in the European Parliament. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mello, P.A., 2012. Parliamentary peace or partisan politics? Democracies’ participation in the Iraq War. Journal of international relations and development, 15 (3), 420–453.

- Milner, H.V. and Judkins, B., 2004. Partisanship, trade policy, and globalization: is there a left–right divide on trade policy? International studies quarterly, 48 (1), 95–119.

- Milner, H.V. and Tingley, D., 2015. Sailing the water’s edge: the domestic politics of American foreign policy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Neuhold, C. and Rosén, G., 2019. Introduction to “Out of the shadows, into the limelight: parliaments and politicisation”. Politics and governance, 7 (3), 220–226.

- Noel, A. and Thérien, J.-P. 2008. Left and right in global politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Norris, P. and Inglehart, R., 2019. Cultural backlash: Trump, Brexit, and authoritarian populism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Otjes, S. and Van der Veer, H., 2016. The eurozone crisis and the European Parliament’s changing lines of conflict. European Union politics, 17 (2), 242–261.

- Rathbun, B.C., 2004. Partisan interventions: European party politics and peace enforcement in the Balkans. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Rathbun, B.C., 2007. Hierarchy and community at home and abroad: evidence of a common structure of domestic and foreign policy beliefs in American elites. Journal of conflict resolution, 51 (3), 379–407.

- Raunio, T. and Wagner, W., 2020a. The Party politics of foreign and security policy. Foreign policy analysis, 16 (4), 515–531.

- Raunio, T. and Wagner, W., 2020b. Party politics or (supra-) national interest? External relations votes in the European Parliament. Foreign policy analysis, 16 (4), 515–531.

- Raunio, T. and Wagner, W., 2021. Contestation over development policy in the European Parliament. Journal of common market studies, 59 (1), 20–36.

- Raunio, T., 1997. The European perspective: transnational party groups in the 1989–94 European Parliament. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Rice, S.A., 1928. Quantitative methods in politics. New York: A.A. Knopf.

- Ringe, N., 2010. Who decides, and how?: Preferences, uncertainty, and policy choice in the European Parliament. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Saalfeld, T., 1995. On dogs and whips: recorded votes. In: H. Döring, ed. Parliaments and majority rule in Western Europe. Frankfurt am Main: Campus, 528–565.

- Thérien, J.-P. and Noel, A., 2000. Political parties and foreign aid. American political science review, 94 (1), 151–162.

- Van den Putte, L., De Ville, F., and Orbie, J., 2015. The European Parliament as an international actor in trade: from power to impact. In: S. Stavridis and D. Irrera, eds. The European Parliament and its international relations. New York: Routledge, 52–69.

- Wagner, W., 2020. The democratic politics of military interventions. political parties, contestation and decisions to use force abroad. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Wagner, W., et al., 2018. Party politics at the water’s edge: contestation of military operations in Europe. European political science review, 10 (4), 537–563.

- Zürn, M., 2014. The politicization of world politics and its effects: eight propositions. European political science review, 6 (1), 47–71.

- Zürn, M. and De Wilde, P., 2016. Debating globalization: cosmopolitanism and communitarianism as political ideologies. Journal of political ideologies, 21 (3), 280–301.