ABSTRACT

For the past few decades, the increased perception of migration as an issue in Europe resulted in the development of the externalisation of the EU’s migration governance to third countries. EU-Turkey and EU-Libya cooperation frameworks on migration have in this perspective been established in the wake of the 2015 migration crisis and triggered major controversies. The agreements received fierce contestation from non-governmental and international actors, highlighting the poor protection of human rights through this management. This paper analyses the dynamics of politicisation of EU-Turkey and EU-Libya agreements on migration in domestic political discourse. A qualitative comparison between German, French and Polish parliamentary debates constitutes the main empirical basis of this research. The analysis focuses on the different patterns of politicisation with emphasis on contesting arguments. This paper examines members of parliaments’ stances on EU-Turkey and EU-Libya cooperation focusing on humanitarian and securitisation frames. Results demonstrate an uneven process of politicisation in national parliaments dependent on the robustness of parliamentary majority and political parties’ issue positions. Overall, the analysis of discourse on the two agreements clearly illustrates the prioritisation of security over human rights when it comes to migration management.

Introduction

Migration has been at the core of concerns in the European Union (EU) for the past few years. The 2015 migration crisis indeed resulted in a politicisation of migration perceived as a challenge for Europe (Grande et al. Citation2019), both with regards to its internal and external dimension.

Most research on the politicisation of migration – understood as intensifying discussions on a given issue in the public sphere (Hutter and Grande Citation2014) – focuses on states’ internal arena and predominantly public or media discourses (e.g. van der Brug et al. Citation2015). This contribution aims to bring a slightly different perspective by focusing exclusively on the politicisation of the external dimension of EU migration policy. Outside of the legal framework developed on migration policy, as well as the European strategy established for EU member states (EUMS) as part of a response to the migration crisis, the EU also develops ties with neighbouring countries as a way to control migration. These dynamics with partner countries make up the external dimension of EU migration policy (Lavenex Citation2004). Externalisation of migration management outside of EU borders had been developed before the 2015 migration crisis, especially since the 2000s (Lavenex Citation2006) when migration was increasingly considered a security issue (Buonfino Citation2004). Two main cooperation frameworks have been developed in the wake of the crisis: the EU-Turkey statement of March 2016 and the EU-Libya agreement of February 2017. Usually considered as providing a quick response to the crisis, the aim behind these agreements is to reduce the number of people irregularly entering the EU. Moreover, the two agreements have been subject to numerous legal considerations with regards to the authorship of the statements (Andrade Citation2018), their binding character (Aloupi Citation2019), as well as the repartition of competences between national and European levels (Carrera et al. Citation2017). Both EU-Turkey and EU-Libya relations on migration are at the centre of this paper and are treated as illustrative cases of the EU’s external migration policy.

Overall, the externalisation of EU migration policy triggers multifaceted impacts for the EU. It is indeed “symptomatic of a longer-term phenomenon with consequences for the future of the European project and the societies affected” (Oliveira Martins and Strange Citation2019, p. 201). Therefore, the EU’s relations with third countries on migration management is meaningful for the EU’s role – and perceived role – in the international and European arenas. The EU-Turkey and EU-Libya agreements faced fierce criticism, particularly from human rights organisations but also different political and international actors; most of their concerns focused on the lack of protection and respect for human rights in Turkey and Libya. Based on these considerations, this paper seeks to examine the process of politicisation that has been developed around these two controversial cooperation frameworks related to EU migration policy: To what extent are the EU-Turkey and EU-Libya agreements on migration politicised in national parliaments? Which political and parliamentary factors trigger politicisation? Which argumentative frames are mobilised by members of parliament (MPs)?

Speeches produced in the German, French and Polish parliaments have been analysed with the use of qualitative content analysis, applied on data collected from 2015 until the end of the year 2019. Whilst these three EUMS have had different reactions throughout the migration crisis and its aftermath, all three witnessed an increasing representation in parliament of political parties holding anti-migration, as well as anti-EU stances – both issues being crucially linked in parties’ discourse (Ivaldi Citation2019). This presence of nationalist, populist and/or Eurosceptic voices in parliaments is analysed in relation to how EU-Turkey and EU-Libya relations on migration are politicised.

This article aims at contributing to the academic reflection on the rising politicisation of EU foreign policy (e.g. Costa Citation2019, Neuhold and Rosén Citation2019), with a special focus on the externalisation of EU migration management. By focusing on politicisation as a discursive process observable in national parliaments, this research investigates the drivers of politicisation, as well as their justifications. This research thus tries to shed light on the role of parliaments and MPs in politicising and advancing security and/or human rights arguments. Eventually, it also provides a reflection on the links between politicisation and securitisation. Academic literature on the interplay between the two concepts indeed presents competing explanations (Bourbeau Citation2013, Castelli Gattinara and Morales Citation2017), despite a consensus on the fact that migration is a highly securitised issue in Europe (Bello Citation2020). In that regard, the results of this contribution show that the politicisation of the external dimension of EU migration policy presents a compelling case in which the security dimension already in place can lead to politicisation. The analysis reveals differences in the extent of politicisation in the three parliaments, dependent on the robustness of parliamentary majority, as well as on political parties’ stances towards European integration and migration. Against a security frame prevailing in MPs’ discourse, the externalisation of migration presents an interesting example of politicisation triggered by pro-European political parties concerned with human rights protection.

The first part of this paper explores EU-Turkey and EU-Libya relations on migration and the reasons why the agreements raised controversy. It also highlights the two argumentative frames used for analysis: security versus human rights. The following section focuses on the operationalisation of the research, especially with regards to politicisation in parliaments. The results of the empirical research are presented following the three main variables of politicisation, i.e. salience, actors and polarisation. Finally, the last part explores the implications of the results regarding domestic opposition to the externalisation of EU migration policy.

External dimension of EU migration policy and its contestation: the EU-Turkey and EU-Libya agreements

EU migration policy has gradually evolved to an international dimension as the EU develops ties with different neighbouring countries to better control migration to its territory (Lavenex Citation2004, Lavenex and Uçarer Citation2004). Indeed, through intergovernmental and supranational policy, the EU moved its governance of migration management outside of its borders (Lavenex Citation2006). The EU’s external migration policy can now be considered as “complementary to EU foreign policy and development cooperation” (Atanassov and Radjenovic Citation2018, p. I). Security-based arguments have been at the core of externalising migration to partner countries (Chou Citation2009, Geddes Citation2014). EU relations with third countries on migration have thus been analysed through a securitisation lens in that migration perceived as a danger is “leading to attempts to ‘manage’, create ‘dialogue’ and establish ‘partnerships’” (Geddes Citation2014, p. 156). Externalisation is a form of governing from a distance (Bigo and Guild Citation2005), which has been both an important and controversial part of EU migration policy since the 2000s (Boswell Citation2003). Furthermore, in the wake of the migration crisis, externalisation has been further developed and “led to the introduction of new policy instruments for cooperation between the EU and non-EU countries on migration issues” (Reslow Citation2019a, p. 273), including the EU-Turkey and EU-Libya agreements. Indeed, facing an increasing number of migrants, refugees and asylum seekers since 2015, agreements with transit countries have been negotiated by EUMS and the EU in order to reduce the number of people coming to its territory. Libya and Turkey are amongst the most contentious ones.

The aim of the EU-Turkey statement of March 2016 was to lessen the number of people entering the EU irregularly through Greek territory from Turkey. This agreement applied to Syrian refugees: every Syrian refugee coming irregularly from Turkey must be returned to Turkey, in exchange of which a Syrian refugee would be resettled in the EU. It also implied significant EU funding for Turkey’s migration management. The EU-Turkey cooperation to deter migration and slow down the number of irregular arrivals on the European territory has been quite controversial and criticised, especially by non-governmental organisations due to the state of democracy and human rights in Turkey (Cogou Citation2017).

The EU-Libya agreement raised controversy for similar reasons (Asiedu Citation2017, Guetta Citation2017). To help Italy with incoming people through the Mediterranean Sea, an increase in cooperation on migration was decided upon with Libya, set by the Malta Declaration of February 2017. The EU aimed to improve the situation of migrants on the ground in Libya and at sea by implementing measures – through financial means – to limit the number of people coming to Europe (European Commission Citation2017). After the slave trade in Libya came to light, several reports highlighted the role of the EU, denouncing the responsibility it had in Libya, even calling European countries “complicit” (Amnesty International Citation2017).

Externalising migration is one of the solutions the EU developed in order to control migration flows, as well as to try to find a compromise between the diverging voices of EUMS. Nonetheless, this need for efficient migration management sometimes conflicted with the EU’s obligation for human rights protection (Neframi and Gatti Citation2020). Both EU-Turkey and EU-Libya agreements triggered contestation from the international community, especially organisations dealing with migration and human rights:

We cannot be a silent witness to modern day slavery, rape and other sexual violence, and unlawful killings in the name of managing migration and preventing desperate and traumatized people from reaching Europe’s shores. (OHCHR Citation2017)

Additionally, recent work on externalisation stated that “EU migration governance lacks sufficient parliamentary oversight” (Oliveira Martins and Strange Citation2019, p. 200). Whilst parliaments’ reactions towards international cooperation on migration have recently been given further academic attention (Reslow Citation2019b), parliamentary discourse has been quite overlooked in analysing EU external migration policy. Thus, this paper investigates the extent to which politicisation is at play in the parliamentary setting. Both securitisation and humanitarian frames have been studied as possible arguments brought up by MPs during their speeches in parliament.

The following section presents the process of data selection, the methodology used, as well as the concepts and hypotheses driving the analysis.

Operationalisation and data collection

Parliamentary debates have been selected to study politicisation, building on the work of several scholars in this field (e.g. national parliaments: Wendler Citation2014, Wonka Citation2016, Góra Citation2021; European Parliament: Góra Citation2021, Wagner et al. Citation2021). Depending on the legal nature of the agreements, the EU more or less has competences in this domain, which ultimately matters in terms of the scope of actions that domestic parliaments have. National parliaments tend to have restricted competences in both foreign policy issues and EU external affairs, including security and defence policy (Mello and Peters Citation2018, Herranz-Surrallés Citation2019). This lack of parliamentary oversight constrains to a certain extent the process of politicisation in domestic parliaments. Nonetheless, as the two cooperation frameworks have been significantly discussed and criticised on the international, European and national arenas, one could argue that it might have – or even should have – triggered repercussions in national parliaments. Parliaments, which are linked to discussion in the wider public sphere (Auel et al. Citation2018), are places where political parties present their ideas and possibly attempt to put the executive under pressure (Mello and Peters Citation2018). Additionally, MPs are often considered as bringing a moral perspective on issues related to international relations and holding special concerns for human rights protection (Beetham Citation2006, Stavridis and Jančić Citation2016). As parliaments are important places for discussions on current political and democratic issues, Lascoumes (Citation2009) argues that “parliamentary politicisation” occurs when important social issues are discussed by the decision-making body that is parliament. Politicisation has mostly been analysed as a discursive phenomenon (Gheyle Citation2019), generally operationalised through several underpinning empirical components, i.e. salience of the issue, expansion of actors and audience engaged in the discussion, as well as polarisation of opinions and/or interests (De Wilde et al. Citation2016, p. 4).

In focusing on parliamentary discourse, this paper primarily examines the dynamics of elite politicisation, i.e. how a discussion over an EU foreign policy issue has implications on a wider range of participants, more specifically national MPs, holding polarised views (Biedenkopf et al. Citation2021). To explore elite politicisation, the analysis particularly zooms on two key aspects underpinning this phenomenon of contested EU foreign policy: (1) the range of actors involved in the debates and (2) the polarisation triggered during discussion.

Although the range of actors is somewhat restricted due to the very nature of parliamentary debates, this dimension has been considered with regards to the number of speakers talking about EU-Turkey and EU-Libya relations on migration during the selected debates, as well as their political role and affiliation.

With regards to the polarisation of opinions and ideas, this dimension of elite politicisation has been examined through in-depth qualitative analysis of the arguments and justifications provided by MPs on the two migration deals. This approach therefore explores different discursive nuances studied alongside human rights and security arguments. This polarisation of opinions is mostly conceptualised through the study of political parties inside parliaments. Indeed, the three national parliaments provide an interesting overview of parties holding pro- and anti-European views, as well as pro- and anti-immigration positions. The stance of a party towards European integration – either in favour or against – is part of the opposition to globalisation that results in the cosmopolitan–communitarian divide, which is studied in this Special Issue as a major line of contestation to CFSP (Biedenkopf et al. Citation2021).

Taking into account the cosmopolitan–communitarian divide and the opposition-majority factor inherent to parliaments, hypotheses have been formulated regarding the drivers of politicisation. Hypotheses zoom especially into opposition parties and parties opposing European integration, as being usual and expected suspects driving politicisation (respectively: Seeberg Citation2013, De Wilde Citation2019).

The first hypothesis takes into account the parliamentary factor of opposition versus majority parties as an element influencing politicisation. Foreign and security policy is usually ruled by the executive; however, parliamentarisation (Raunio and Wagner Citation2017) and/or politicisation in parliament (Neuhold and Rosén Citation2019) can occur under certain conditions. Political parties inside parliaments are indeed influenced by their ideological positions, but also their relation towards the executive in that the links between executive and legislative play an important role in foreign and security affairs (Wagner et al. Citation2017). Opposition parties might indeed seek to politicise issues in order to influence policy-making (Seeberg Citation2013). Thus, the first hypothesis posits that politicisation would rather arise from the opposition, as politicisation – and polarisation – of migration is usually enshrined in the political party competition process (Grande et al. Citation2019).

H1: An opposition party in a parliament is more likely to politicise EU-Turkey and EU-Libya relations on migration.

The second hypothesis focuses on parties’ position towards EU integration by postulating that the more opposed to the EU a party is, the more likely the party would talk about it. This point echoes previous research made on politicisation of EU affairs demonstrating that Eurosceptics are usually drivers of politicisation (Hutter and Kriesi Citation2019, Hoerner Citation2019).

H2: A political party inside a parliament which firmly opposes EU integration is more likely to politicise EU-Turkey and EU-Libya relations on migration.

These two hypotheses have been investigated based on the political actors taking a stand during the selected parliamentary debates, specifically looking into the justifications and arguments provided. Three lower chambers of parliament have been taken for analysis: the German Bundestag, the French Assemblée nationale and the Polish Sejm. The migration crisis impacted these countries to a different extent, yet all three EUMS have political parties in parliament holding pro- and anti-European views, as well as pro- and anti-immigration positions, which are expected to influence MPs’ discourse on the external dimension of EU migration policy. Furthermore, differences between countries in the involvement in and the management of the crisis are observable, as well as differences in their relations with Turkey and Libya, which provide an interesting perspective of research when analysing and comparing patterns of politicisation.

Political party ideological positions and the composition of parliaments have been taken into account for the analysis. Political parties sitting in the three studied parliaments have been considered mostly through their party position on European integration (based on ParlGov database: Döring and Manow Citation2020). The period of time researched covered two parliamentary terms in the Bundestag and the Assemblée nationale. During both 18th (2013–2017) and 19th (2017–2021) terms of the German parliament, the Christlich Demokratische Union (Christian Democratic Union – CDU) has been holding the majority and forming a government alongside the Christlich Soziale Union (Christian Social Union – CSU) and the Social Democratic Party of Germany (Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands – SPD). The far-right Eurosceptic and anti-migration party Alternative for Germany (Alternative für Deutschland – AfD) did not have any seats during the 18th term, but following the 2017 elections the party holds 92 seats in the Bundestag. During the 14th legislature (2012–2017) the majority in the Assemblée nationale was favourable to the left with the Socialist Party (Parti socialiste – PS) in the majority. The majority changed in the 15th term with the new liberal party La République En Marche! (The Republic Onwards! – REM). In Poland, the selected data encompass only the 8th term (2015–2019) with the conservative party Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (Law and Justice – PiS) holding a strong majority in the Sejm.

The present research does not exhaustively investigate all debates mentioning EU-Turkey and EU-Libya agreements but works on a specific selection of the main plenary sessions as a core illustration of discussion and arguments on the topic. The selection has been first based by searching with the keywords “Turkey” and “Libya” (in original languages and taking into account the adjective forms), and then further defined through close reading to ensure that the mentioning of Turkey or Libya refers to migration management and the EU’s external relations. The selected parliamentary activities are slightly different from one parliament to another. These differences between parliaments are already telling with regards to the salience of the issue and will be discussed in the following section, which presents the results of the qualitative analysis.

Findings and analysis

Parliamentary activities

Over the analysed timeframe (2015–2019), the majority of the selected data (see Table A1 in the appendices) covered predominantly the period from the end of 2015 to 2017, i.e. going along with the timeline of the main events of the two agreements. The salience in parliaments thus followed the external events happening on the issue. Moreover, it is important to reflect on the diversity of selected parliamentary activities during which EU-Libya and EU-Turkey relations on migration were discussed.

In the German Bundestag six plenary debates were selected for analysis, all of them discussing EU-Turkey and/or EU-Libya relations. Out of the six plenary sessions, one debate was strictly focused on Libya (with 41 occurrences), the rest of the plenaries instead dealt with EU’s relations with Turkey (with 405 occurrences). This prominence of EU-Turkey relations might be explained by Germany’s historical links with Turkey, as well as the country’s involvement in the negotiation of the EU-Turkey agreement. Furthermore, the dataset includes one debate called Aktuelle Stunden, which is a topical debate requested either by a parliamentary group or at least five percent of MPs. It usually reflects MPs’ interest on a current issue without necessarily going into the law-making process. Two selected plenaries were government statements (Regierungserklärung) in preparation to the European Council: the German Chancellor then explains the main points that will be raised during the meeting with other European Heads of States and Governments. The other three debates selected are Anträge, i.e. motions proposed by MPs. Two motions were proposed by the parliamentary group Bündnis 90/Die Grünen (Alliance 90/Greens – B90/Gru), whilst the other one was initiated by Die Linke (The Left). Thus, based on the initiators of the discussion in the Bundestag, it seems that either the executive or rather pro-European political parties from the opposition were more likely to trigger discussion on the topic.

In the French Assemblée nationale, EU-Turkey and EU-Libya relations were not subject to a full plenary session during the period of time researched. However, the two agreements were discussed during the question sessions addressed to the government – most usually to the ministers of European or Foreign Affairs. The data selected from the French parliament include a total of 16 questions to the government during nine specific plenaries: four questions were focusing on Turkey (with 66 occurrences), whilst the other 12 questions were discussing Libya (with 94 occurrences). France’s relations with and involvement in Libya might indeed explain this more salient discussion on the country’s situation. In addition, it is interesting to see that the questions were primarily initiated by pro-European right-wing political parties from the opposition, i.e. Les Républicains (The Republicans – LR) and Union des démocrates et indépendants (Union of Democrats and Independents – UDI).

As for the Polish Sejm, there was no full debate on the issue, nor specific questions asked by MPs. However, during the review of European affairs taking place in plenary setting every semester, both EU-Turkey and EU-Libya have been mentioned and discussed. During the four sessions that have been selected for analysis, Turkey was overall more addressed (27 occurrences) than Libya (eight occurrences) and each time the subjects were first brought up by the executive making a statement on European affairs, then further discussed by MPs.

This review of parliamentary activities regarding EU-Turkey and EU-Libya cooperation on migration already demonstrates that salience follows the adoption of the agreements. Besides, the salience and extent of politicisation differ between parliaments. The debate on Turkey was more prominent in the German parliament, whilst Libya was more debated in the French parliament. Both issues were not at the core of any specific debates in Poland.

Actor range

Whilst the expansion of actors is generally developed as the involvement of non-political actors, notably from civil society, the nature of parliamentary debates does not allow this type of analysis, as mostly members from the executive and MPs following specific parliamentary rules of procedures take the floor during parliamentary debates (Proksch and Slapin Citation2014). This paper thus focuses on elite politicisation as the involvement of national political actors in an EU foreign policy discussion. Indeed, one could argue that the involvement of MPs in a discussion on foreign policy, which most of the time is dealt with by the executive, already shows a broadening of the discussion in the domestic political arena.

A total of 73 different speakers – who might be speaking several times during selected debates – were discussing EU-Turkey and EU-Libya agreements: 42 in the Bundestag, 18 in the Assemblée nationale and 13 in the Sejm. Amongst them, seven speakers were from outside of parliaments, mostly representatives from the respective governments, e.g. Chancellor, Prime Minister, ministers of European or Foreign Affairs. The involvement of state officials, i.e. representatives from the executive power in foreign policy, is not very surprising. Furthermore, as demonstrated in Table A2, the increased salience was especially noticeable in 2016 for Turkey and in 2016–2017 for Libya, with a rise in the number of occurrences, speeches and speakers – notably MPs. Thus, the salience in parliament occurred simultaneously to the conclusions of the agreements.

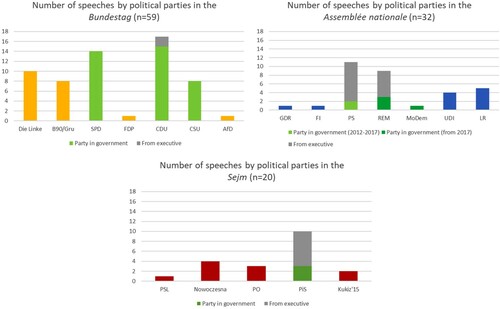

Overall, 111 speeches containing references to Libya and Turkey were analysedFootnote1; the repartition of speeches by political parties is shown in Figure A1 in the appendices. As demonstrated, debates on the EU-Turkey and EU-Libya agreements were addressed by pro-European parties on the left side of the political spectrum in the German and Polish parliaments. On the contrary, the same issue was mentioned by relatively pro-European parties from the right side of the political spectrum in the French parliament. This difference follows the majority-opposition dimension inside parliament. Indeed, the majority in France during the analysed timeframe was predominantly held by the Socialist party, whilst the majority was instead held by right-wing parties in Germany and Poland. Eurosceptic right-wing parties – less represented in selected parliaments – were less active on the topic. The German left-wing party Die Linke, which shows limited support towards European integration, was however quite active.

The next part presents the results of the qualitative analysis of speeches, focusing especially on the MPs’ stances in favour or against the agreements, as well as their justifications based on the previously described humanitarian and securitisation frames.

Polarisation of opinions and argumentative frames

MPs as well as government representatives put forward various discursive arguments on the two agreements. First, one has to note that both agreements triggered very similar justifications. Therefore, the third country at play was not part of the contesting dimension; MPs instead opposed the agreements due to the involvement of the EU or the very foundation of the agreement with third country.

A division between left and right-wing parties can be noted, respectively opposing or favouring the agreements; yet, this division was less sensible when left-wing parties were in government, i.e. in the French case. This line of division follows the general views on migration that political parties hold and triggered human rights or security-driven arguments. Indeed, all three governments and parties from the majority in parliament supported both agreements in the prospect of reducing the number of migrants coming, as well as securing Europe and its external borders:

To this day, due to political difficulties in Libya, it is difficult to repeat the successful experience of the European Union-Turkey agreement, but the direction of these changes, the direction of this policy is fully supported by the Polish government. These are, in fact, the only instruments that can bring the desirable, I believe, state of full control of the external border and migration movement in the European Union. (Konrad Szymański, Secretary of State for European Affairs, PiS, PL_12-10-2017)Footnote2

Despite all justified criticism of President Erdogan and his policies, one has to note that: Syrian refugees are safe in Turkey. Turkey provides protection and security to more Syrians than all other European countries combined. (Thomas Oppermann, MP, SPD, DE_16-03-2016)

Similar security concerns were expressed in the French and German parliaments, especially stressing that the situation in these countries was an “element of our own security” (Nicole Ameline, MP, LR, FR_16-12-2015). Concerns over the migration crisis were perceived as more important, thus strengthening the support for the agreement:

[I]n my view, the agreement between the EU and Turkey on March 18 is significantly better than it is presented to the public. It is much better than its reputation. I do not want to overstate it, but I believe that this agreement is an important building block in the entire toolbox for combating and coping, which is now being used in the refugee crisis. (Stephan Mayer, MP, CSU, DE_12-05-2016)

Turkey is a strategic partner of France and the European Union: we must start from this observation. With this great country, we must have relations that are both clear, confident and demanding – in particular, as you have just mentioned, on the principles which are those of the European Union: the rule of law, the independence of powers, freedom of opinion and freedom of the press. We will not give it up at any cost. (Jean-Marc Ayrault, Minister of Foreign Affairs and International Development, PS, FR_27-04-2016)

The CNN report broadcasted in November 2017 on the existence of slave markets of migrants in Libya triggered much discussion in the French parliament from different political parties, all of them raising the question of the EU and France’s response to the situation in order to “put an end to these horrors as soon as possible” (Max Mathiasin, MP, MD, FR_21-11-2017). The French executive, whilst discursively condemning slave trade in Libya, focused on providing Libya with humanitarian aid and supporting the actions from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees on the ground. Furthermore, the government asked for greater EU involvement:

We also call for a strengthening of the civilian police missions deployed by the European Union to the southern borders of Libya to combat smugglers. This fight against human traffickers also involves European sanctions against them, and therefore through stronger cooperation between our police services to establish and share the lists of individuals and networks who flout the most fundamental human values. (Nathalie Loiseau, Minister for European Affairs, REM, FR_21-11-2017)

But if cooperation with Turkey is our opportunity to open legal channels to Europe, put an end to the smugglers and come to a unified policy in Europe, then it is well worth the effort, then the talks with Turkey are worthwhile, and then it makes sense and is right. (Eva Högl, MP, SPD, DE_16-03-2016)

It is essential that our European allies join our mobilisation in the face of the magnitude of the human challenge. Europe must be able to deploy a response commensurate with its political project. (Sereine Mauborgne, MP, REM, FR_21-11-2017)

In the [EU-Turkey] deal that threatens us, refugees are no longer individuals whose vulnerability is examined in individual cases. There are only arithmetic variables in the barter between the European Union and Turkey, in which, for example, Afghans and Iraqis are completely ignored. That is inhuman. That is unworthy of Europe and it is unacceptable. Therefore: Stop that, Ms. Merkel! (Anton Hofreiter, MP, B90/Gru, DE_16-03-2016)

But, Mr Oppermann, it is not about “arrogant” or “condescending” if we find it wrong to make Turkey a European doorman, knowing that Erdogan uses this unconditionality with which we approach him to us to silence when it comes to its inhumane domestic and foreign policy actions. And that is exactly what is happening right now. (Luise Amtsberg, MP, B90/Gru, DE_16-03-2016)

[T]he extraordinary summit which was held on Monday between the European Union and Turkey acted on a triple renunciation, of unprecedented gravity: that of a Europe which renounces the right of asylum by driving back migrants because it has not been able to agree on a common migration and security policy; that of a Europe that haggles for the relaunch of the accession process in exchange for an illusory bulwark against the victims of conflicts that we have not been able to manage; finally, that of a France whose silence is guilty. (François Rochebloine, MP, UDI FR_2016-03-09)

[T]he agreement with Turkey has led to fewer refugees in Europe - some of you think that is good - but that they are by no means a solution for and in Europe. This agreement did not lead to more solidarity in Europe, but shifted the issue to our borders. This agreement primarily affects those seeking protection who are left standing at the gates of Europe. For them it means: out of sight, out of mind. (Luise Amtsberg, MP, B90/Gru, DE_24-06-2016)

For example, the EU plans to work with Libya to help protect refugees - a country where you cannot agree on a government where warlords and Islamist groups are at war with each other. You really ask yourself: where are the European values, where are the democratic values when you negotiate with such countries to ward off refugees? There are now plans for agreements similar to those with Turkey. Here too, attempts are being made to build up a foreclosure front. (Ulla Jelpke, MP, Die Linke, DE_28-04-2016)

But that is exactly what is happening through the German federal government. The visa question is part of this dirty EU-Turkey deal that we deeply reject. We do not want visa liberalisation, for which the price is silence about Erdogan’s crimes against the civilian population in Turkey. (Sevim Dağdelen, MP, Die Linke, DE_12-05-2016)

Politicisation in parliament

All three parliaments demonstrated common argumentative frames for the two agreements and appealed either to human rights or security concerns. Nonetheless, the degree of presence of these arguments varied with the presence of political parties and the robustness of the parliamentary majority.

The Polish parliament proved to have a solid view across political parties that both EU-Turkey and EU-Libya agreements were beneficial for the country and Europe in reducing the number of migrants. The PiS government – which holds anti-migration views and is rather Eurosceptic – had a strong majority in the parliament, which seemed to result in a lack of clear opposition to the agreements. One must note that migration has been one of the key concerns in Poland, especially in the wake of the 2015 migration crisis (Frelak Citation2019). No political party at that time in the Sejm was in favour of a liberal migration policy, and migration has been strongly securitised in both discourse and policy practices (Fomina and Kucharczyk Citation2018). In the context of EU-Turkey and EU-Libya relations on migration, the EU was praised for its external migration policy in the Polish parliament. In the French parliament, more contestation can be noted from parties that were in opposition, especially regarding the EU-Libya agreement. Whilst there were some concerns about human rights from left-wing parties, the parliament overall demonstrated a rather positive vision of the agreements. Strong opposition to the agreements can be noted from two political parties in the German Bundestag. Indeed, opposition parties fiercely disapproved of Germany’s and the EU’s involvement with third countries with a questionable democratic situation. This increased debate and strong opposing arguments in the French and German parliaments demonstrated that EU-Turkey and EU-Libya agreements triggered elite politicisation in national parliaments, with a deeper polarisation to be noted in the German case.

Overall, when the lack of regard for human rights protection was pointed out by MPs, it resulted in a clear opposition against the government’s actions, as well as the EU. Although the parties that criticised the EU in this context favour European integration, they were the only ones opposing the EU on this issue, highlighting the lack of responsibility towards migrants and refugees, as well as respect for its own values. On the other hand, the three parliamentary majorities – alongside governments – showed strong security concerns over the migration crisis and therefore framed the EU-Turkey and EU-Libya agreements as a positive answer to decrease the number of migrants coming to Europe. The democratic and human rights situation in the partner country was disregarded in the name of security. In this perspective, the EU’s actions in these agreements were seen as positive and praised, even by political parties which usually hold a quite Eurosceptic stance.

Regarding the set of working hypotheses, the results of the analysis confirm H1 as in the German and French parliaments, the opposition – disregarding the left-right or pro- and anti-European integration divide – is politicising EU-Turkey and EU-Libya relations on migration. However, H2 is refuted by the results, as in selected parliaments the drivers of politicisation were mostly pro-EU integration parties and not Eurosceptics. The Polish parliament thus happened to be the one in which the two migration agreements were the least – if at all – politicised, as the parliament as a whole held a rather Eurosceptic and anti-migration stance. Eventually, this paradoxical finding of pro-European parties seeking to politicise EU external relations on migration demonstrates the complexity of the links between politicisation and securitisation. Whilst politicisation does not automatically equal securitisation, different hypotheses have been developed on the relations between the two concepts, notably “intensification and contestation” (Bourbeau Citation2013, p. 143). Intensification implies that politicisation triggers greater securitisation, whilst on the contrary the securitisation process in place generates politicisation according to the contestation hypothesis. In the case of EU-Turkey and EU-Libya agreements on migration, the security dimension is at the core of the externalisation. The construction of security discourse, especially from the side of Eurosceptic and (far) right-wing parties, was therefore anticipated. Nonetheless, the discursive act of politicising migration by left-wing and especially pro-European integration parties – for instance in the Bundestag – demonstrates the willingness to oppose securitisation and bring a human rights perspective in the debate on the externalisation of EU migration policy.

Concluding remarks

Whilst criticism and contestation so far did not stop EU’s externalisation of migration policy to third countries (Reslow Citation2019a, Scarpello Citation2019), it is interesting to see that such a process exists in national parliaments.

This contribution examined the process of politicisation of EU-Turkey and EU-Libya migration agreements as illustrative examples of the EU’s externalisation of migration policy. This paper demonstrated an uneven process of politicisation in the three parliaments of analysis. Whilst both agreements received little attention in the Polish Sejm, the politicisation in both German and French parliaments was more prominent. Furthermore, contestation was especially fierce in the Bundestag.

Based on a set of hypotheses on the drivers of politicisation inside parliaments, this research postulates that EU-Turkey and EU-Libya migration agreements attest to an almost antithetical process. Indeed, although enshrined in the cosmopolitan–communitarian divide, the discussion on the externalisation of migration policy witnesses pro-European integration parties being drivers for politicisation and polarisation, and not Eurosceptics. This stems from the fact that pro-EU parties – also mainly favourable of a liberal migration policy – contest the EU’s actions through the agreements. They hence disapproved of the EU’s lack of self-respect for its own values when externalising migration. Eurosceptic right-wing parties on the contrary view the agreements positively for being an adequate response to the security situation in Europe regarding migration. On this point, Reslow (Citation2019b) demonstrates that parliaments as “moral tribunes” might be challenged by the presence of (far) right-wing parties. As shown through the focus on humanitarian and securitisation frames, this phenomenon of politicisation of an issue touching upon human rights protection highlights the contentious character of migration, in which security – considered as a necessity – often overtakes other concerns.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the editors of the Special Issue, as well as all contributors, for their valuable comments and for convening the interesting exchanges which led to this Special Issue. I would also like to thank Prof. Helene Sjursen for her constructive feedback on the early stage of this paper and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Elodie Thevenin

Elodie Thevenin is a PhD candidate in Political Science at the Doctoral School in the Social Sciences of the Jagiellonian University in Kraków. She also works at the JU Institute of European Studies as a research assistant on the EU Horizon 2020 project “EU Differentiation, Dominance and Democracy (EU3D)”. Her academic interests encompass subjects related to migration, parliamentary discourse and identity. Her doctoral research focuses on the discussion on migration in national parliaments and the European Parliament in relation to the development of European integration. She is a fellow of the Europaeum Scholars Programme (2020/2021).

Notes

1 Speeches have been conceptualised as a set of arguments on the issue containing “Libya” and/or “Turkey”, small interactions inside parliament have not been considered in the analysis.

2 Translations from German, French and Polish to English have been made by the author of the paper, as well as emphases in italics. All quotes from parliamentary debates are presented with the name of the speaker, the political function of the speaker in the debate, her/his national party affiliation, the national affiliation and the date of the debate.

References

- Aloupi, N., 2019. L’« accord » UE-Turquie: approche critique. In: C. Haguenau-Moizard and F. Gazin, eds. Les réformes du droit de l’asile dans l’Union européenne. Strasbourg: Presses universitaires de Strasbourg, 47–62.

- Amnesty International, 2017. Libya: European governments complicit in horrific abuse of refugees and migrants [online]. Available from: https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2017/12/libya-european-governments-complicit-in-horrific-abuse-of-refugees-and-migrants/ [Accessed 14 March 2019].

- Andrade, P.G., 2018. External competence and representation of the EU and its member states in the area of migration and asylum. [online]. EU Migration and Asylum Law and Policy. [online]. Available from: http://eumigrationlawblog.eu/external-competence-and-representation-of-the-eu-and-its-member-states-in-the-area-of-migration-and-asylum/ [Accessed 14 July 2020].

- Asiedu, M., 2017. The EU-Libya migrant deal: a deal of convenience [online]. E-International Relations. Available from: http://www.e-ir.info/2017/04/11/the-eu-libya-migrant-deal-a-deal-of-convenience/ [Accessed 10 Avril 2019].

- Atanassov, N., and Radjenovic, A., 2018. EU asylum, borders and external cooperation on migration [online]. European Parliamentary Research Service [online]. Available from: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/46ea7280-c5f1-11e8-9424-01aa75ed71a1/language-en [Accessed 12 July 2020].

- Auel, K., Eisele, O., and Kinski, L., 2018. What happens in parliament stays in parliament? Newspaper coverage of National Parliaments in EU affairs. JCMS: Journal of common market studies, 56 (3), 628–645.

- Beetham, D., 2006. Parliament and democracy in the twenty-first century: a guide to good practice. Geneva: Interparliamentary Union.

- Bello, V., 2020. The spiralling of the securitisation of migration in the EU: from the management of a ‘crisis’ to a governance of human mobility? Journal of ethnic and migration studies, 1–18.

- Biedenkopf, K., Costa, O., and Góra, M., 2021. Shades of contestation and politicisation of CFSP. European security. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09662839.2021.1964473

- Bigo, D., and Guild, E., 2005. Introduction: policing in the name of freedom. In: D. Bigo and E. Guild, eds. Controlling frontiers: free movement into and within Europe. Aldershot: Ashgate, 1–13.

- Bigo, D., 2002. Security and immigration: toward a critique of the governmentality of Unease. Alternatives: global, local, political, 27 (Special Issue), 63–92.

- Boswell, C., 2003. The “external dimension” of EU immigration and asylum policy. International affairs, 79 (3), 619–638.

- Bourbeau, P., 2013. Politisation et sécuritisation des migrations internationales: une relation à définir. Critique internationale, 4 (4), 127–145.

- Buonfino, A., 2004. Between unity and plurality: the politicisation and securitisation of the discourse of Immigration in Europe. New political science, 26 (1), 23–48.

- Carrera, S., den Hertog, L., and Stefan, M., 2017. It wasn’t me! The Luxembourg court orders on the EU-Turkey refugee deal. CEPS [online], 15. Available from: https://www.ceps.eu/ceps-publications/it-wasnt-me-luxembourg-court-orders-eu-turkey-refugee-deal/ [Accessed 14 July 2020].

- Castelli Gattinara, P., and Morales, L., 2017. The politicization and securitization of migration in Western Europe: public opinion, political parties and the immigration issue. In: P. Bourbeau, ed. Handbook on migration and security. Northampton: Edward Elgar, 273–295.

- Chou, M.H., 2009. The European security agenda and the ‘external dimension’ of EU asylum and migration cooperation. Perspectives on European politics and society, 10 (4), 541–559.

- Cogou, K., 2017. The EU-Turkey deal: Europe’s year of shame [online]. Amnesty International. Available from: https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2017/03/the-eu-turkey-deal-europes-year-of-shame/ [Accessed 13 June 2019].

- Costa, O., 2019. The politicization of EU external relations. Journal of European public policy, 26 (5), 790–802.

- De Wilde, P., et al., 2019. The struggle over borders: cosmopolitanism and communitarianism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- De Wilde, P., Leupold, A., and Schmidtke, H., 2016. Introduction: The differentiated politicisation of European governance. West European politics, 39 (1), 3–22.

- Döring, H., and Manow, P., 2020. Data from: Parliaments and governments database (ParlGov): Information on parties, elections and cabinets in modern democracies. Development version [dataset]. Available from: http://www.parlgov.org/ [Accessed 1 July 2020].

- European Commission, 2017. EU action in Libya on Migration [online]. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/what-we-do/policies/european-agenda-migration/20171207_eu_action_in_libya_on_migration_en.pdf [Accessed 15 April 2018].

- Fomina, J., and Kucharczyk, J., 2018. From politics of fear to securitisation policies? Poland in the face of migration crisis. In: J. Kucharczyk and G. Mesežnikov, eds. Phantom menace. The politics and policies of migration in central Europe. Prague: Institute for Public Affairs and Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung, 185–202.

- Frelak, J.S., 2019. Migration politics and policies in Poland. In: U. Guérot and M. Hunklinger, eds. Old and new cleavages in polish society. Krems: Edition Donau-Universität Krems, 117–132.

- Geddes, A., 2014. The European Union’s international migration relations towards Middle Eastern and North African countries. In: M. Bommes, H. Fassmann, and W. Sievers, eds. Migration from the Middle East and North Africa to Europe. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 139–158.

- Gheyle, N., 2019. Conceptualizing the parliamentarization and politicization of European policies. Politics and governance, 7 (3), 227–236.

- Góra, M., 2021. Its security stupid! Politicisation of the EU's relations with neighbours. European security. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09662839.2021.1957841

- Grande, E., Schwarzbözl, T., and Fatke, M., 2019. Politicizing immigration in Western Europe. Journal of European public policy, 26 (10), 1444–1463.

- Greussing, E., and Boomgaarden, H.G., 2017. Shifting the refugee narrative? An automated frame analysis of Europe’s 2015 refugee crisis. Journal of ethnic and migration studies, 43 (11), 1749–1774.

- Guetta, B., 2017. Le Goulag libyen [online]. France Inter. Available from: https://www.franceinter.fr/emissions/geopolitique/geopolitique-15-novembre-2017 [Accessed 18 January 2018].

- Harrell-Bond, B., 2002. Can humanitarian work with refugees be humane? Human rights quarterly, 24, 51–85.

- Herranz-Surrallés, A., 2019. Paradoxes of parliamentarization in European security and defence: when politicization and integration undercut parliamentary capital. Journal of European integration, 41 (1), 29–45.

- Hoerner, J.M., 2019. Adding fuel to the flames? politicisation of EU policy evaluation in National Parliaments. Politische vierteljahresschrift, 60 (4), 805–821.

- Horsti, K., 2013. De-ethnicized victims: mediatized advocacy for asylum seekers. Journalism, 14 (1), 78–95.

- Hutter, S., and Grande, E., 2014. Politicizing Europe in the national electoral arena: a comparative analysis of five west European Countries, 1970-2010. Journal of common market studies, 52 (5), 1002–1018.

- Hutter, S., and Kriesi, H., 2019. Politicizing Europe in times of crisis. Journal of European public policy, 26 (7), 996–1017.

- Ivaldi, G., 2019. De Le Pen à Trump : le défi populiste. Bruxelles: Editions de l’Université de Bruxelles.

- Lascoumes, P., 2009. Les compromis parlementaires, combinaisons de surpolitisation et de souspolitisation: L’adoption des lois de réforme du Code pénal (décembre 1992) et de création du Pacs (novembre 1999). Revue française de science politique, 59 (3), 455–478.

- Lavenex, S., and Uçarer, E.M., 2004. The external dimension of Europeanization: the case of immigration policies. Cooperation and conflict: journal of the nordic international Studies association, 39 (4), 417–443.

- Lavenex, S., 2004. EU external governance in ‘wider Europe’. Journal of European public policy, 11 (4), 680–700.

- Lavenex, S., 2006. Shifting up and out: the foreign policy of European immigration control. West European politics, 29 (2), 329–350.

- Lemberg-Pedersen, M., 2019. Manufacturing displacement. Externalisation and postcoloniality in European migration control. Global affairs, 5 (3), 247–271.

- Mello, P.A., and Peters, D., 2018. Parliaments in security policy: involvement, politicisation, and influence. The British journal of politics and international relations, 20 (1), 3–18.

- Neframi, E., and Gatti, M., 2020. Externalisation de la politique migratoire et identité de l’Union européenne. In: M. Benlolo Carabot, ed. Union européenne et migrations. Bruxelles: Bruylant, 249–273.

- Neuhold, C., and Rosén, G., 2019. Out of the shadows, into the limelight: parliaments and politicisation. Politics and governance, 7 (3), 220–226.

- OHCHR, 2017. UN human rights chief: suffering of migrants in Libya outrage to conscience of humanity [online]. Available from http://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=22393&LangID=E [Accessed 18 December 2018].

- Oliveira Martins, B., and Strange, M., 2019. Rethinking EU external migration policy: contestation and critique. Global affairs, 5 (3), 195–202.

- Proksch, S.-O., and Slapin, J.B., 2014. The politics of Parliamentary Debate: parties, rebels and representation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Raunio, T., and Wagner, W., 2017. Towards parliamentarisation of foreign and security policy? West European politics, 40 (1), 1–19.

- Wagner, W., Herranz-Surrallés, A., Kaarbo, J., and Ostermann, F., 2017. The party politics of legislative-executive relations in security and defense policy. West European politics, 40 (1), 20–41.

- Wagner, W., Pelaez, L., Raunio, T., and van de Koppel, M., 2021. The party politics of the EU's relations with the USA. Evidence from the European parliament. European security. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09662839.2021.1947803

- Reslow, N., 2019a. EU external migration policy: taking stock and looking forward. Global affairs, 5 (3), 273–278.

- Reslow, N., 2019b. Human rights, domestic politics, and informal agreements: parliamentary challenges to international cooperation on migration management. Australian journal of international affairs, 73 (6), 546–563.

- Roman, E., 2019. EU’s migration policies in the eyes of “partner” countries’ civil society actors: the case of Tunisia. Global affairs, 5 (3), 203–219.

- Scarpello, F., 2019. The “Australian model” and its long-term consequences. Reflections on Europe. Global affairs, 5 (3), 221–233.

- Seeberg, H.B., 2013. The opposition’s policy influence through issue politicization. Journal of public policy, 33 (1), 89–107.

- Stavridis, S., and Jančić, D., 2016. Introduction. The rise of parliamentary diplomacy in international politics. The hague journal of diplomacy, 11, 105–120.

- Strange, M., and Oliveira Martins, B., 2019. Claiming parity between unequal partners: how African counterparts are framed in the externalisation of EU migration governance. Global affairs, 5 (3), 235–246.

- Triandafyllidou, A., and Kouki, H., 2013. Muslim immigrants and the Greek nation: the emergence of nationalist intolerance. Ethnicities, 13 (6), 709–728.

- van der Brug, W., et al., 2015. The politicisation of migration. London: Routledge.

- Wagner, W., et al., 2017. The party politics of legislative–executive relations in security and defense policy. West European politics, 40 (1), 20–41.

- Wæver, O., 1995. Securitisation and desecuritisation. In: R.D. Lipschutz, ed. On security. New York: Columbia University Press, 46–87.

- Wendler, F., 2014. Debating Europe in national parliaments. Justifications and political polarization in debates on the EU on Austria, France, Germany and the United Kingdom. OPAL onlinepaper series, 17, 3–34.

- Wonka, A., 2016. The party politics of the Euro crisis in the German Bundestag: frames, positions and salience. West European politics, 39 (1), 125–144.

Appendices

Table A1. Overview of selected parliamentary debates.

Table A2. Number of occurrences of “Turkey” and “Libya”, number of speeches containing the occurrences and number of speakers in selected parliamentary debates.