ABSTRACT

This paper examines the response of the members of the European Council towards the EU’s sanctions policy against Russia following the 2014 Russian occupation and annexation of Crimea and the continued Ukraine crisis. The case is analysed to answer the question on the traits of the politicisation of the EU’s Russia sanctions policy. Concretely, the main research question is: what does the interplay of actor range, salience, and polarisation tell us about politicisation of CFSP in the case of sanctions policy? The secondary research question deals with how actors interact when contesting a sanctions policy to boost their success. Considering that the European Council, as the main actor in CFSP, is something of a “black box”, the paper heuristically focuses on statements (N = 223) on the sanctions policy given by its members from March 2014 till the end of 2019. The analysis shows how the politicisation of the sanctions policy seemingly entrenched itself into EUFP politics after it skyrocketed and fell in the wake of Russia’s annexation of Crimea. Finally, a latent class analysis indicates the existence of two latent coalitions with opposing views on the sanctions policy.

Introduction

The EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) is being increasingly politicised and contested. But how? By whom? When? How intensely? For how long? This exploratory paper is part of a special issue aiming to answer these basic questions about the process of EU foreign policy politicisation and contestation by operationalising the concepts of politicisation and contestation, applying them to the study of a concrete policy, and exploring if it can tell us something about the ways in which political conflict is being (re)structured in the EU.

The case we have chosen to analyse is the politicisation of the EU sanctions policy on Russia that was enacted as a response to the Russian involvement in the 2014 Ukraine crisis, especially the occupation and annexation of Crimea and Sevastopol. EU–Russia relations are, arguably, one of the most important facets of the EU’s foreign policy, and since the decision on sanctions represents a major shift in that policy, it is important to analyse the politicisation of that case.

Since the CFSP is mainly in the hands of the European Council, an EU institution whose sessions and voting are held behind closed doors, there is no way to directly study the process of politicisation of the Russian sanctions and CFSP in general. Therefore, a proxy is needed. We found it in public statements members of the European Council had given in the analysed period. Our exploratory research focused on public statements (both those contesting and supporting sanctions) made by members of the European Council as a proxy for the position the representatives held on the policy during the European Council meetings. We gathered and analysed statements (seeing them as speech acts performed) from the start of the Ukraine crisis in March 2014, up to the end of 2019, to understand what the politicisation of the sanctions policy on Russia can tell us about the nature of politicisation itself. Also, we used those statements to gauge the existence of potential coalitions of member states, which should exist according to the theory positing the existence of communitarian–cosmopolitan cleavage that drives CFSP politicisation (as cleavage cannot exist without at least two opposing sides on each side of the wedge issue).

Since politicisation and contestation of this particular case, or politicisation and contestation inside the European Council more generally, were scarcely studied, we can only make basic assumptions about the results of the study: we would expect contestation and politicisation to be tied to the situation in Ukraine (exogenous circumstances); we would also expect for contestation and politicisation to arise before the European Council meetings (endogenous circumstances).

Furthermore, although almost 70 per cent of Europeans are in favour of CFSP (Standard Eurobarometer Citation2019, p. 102), and there is evidence to support that the policy area is moving into the public domain (Koenig Citation2019), it is still not a policy field that is generally high on the list of important public policies for the Europeans, with the public interest lacking (Huff Citation2015, p. 407), and its character remaining relatively secluded (Biedenkopf et al. Citation2021, p. 20). Hence, we don’t expect to find much mass mobilisation on the sanctions policy in the citizen’s arena. Therefore, the relatively higher level of politicisation that exists is driven by something other than public pressure. What that needs is further research. For this paper it is enough to note that the actor range, which encompasses the spill-over of politicisation from one area to another, does not need to be transmitted to a mobilised public to have an influence on politicisation. The European Council, as a relatively closed system, represents an arena unto itself, with actors using their leverage, clout, and the power of persuasion to entice other actors to start contesting (or defending) a policy, thus politicising it further.

Since (various kinds of) coalition–building presents a common strategy (especially for small states) of influencing the EUFP decision-making process (Pastore Citation2013, pp. 78–79), we consider it likely we will find traces of coalition–building in the case as well. Schoeller (Citation2020) already showed how Germany took up the leadership role in handling the Ukraine crisis by default (because, among other reasons, the UK, France nor EU institutions wanted or could take the leading role).Footnote1

Finally, building on Biedenkopf, Costa and Gora’s (in this volume) hypothesis on the existence of a cosmopolitan–communitarian cleavage in EUFP and supported by Schoeller’s previous research, we explored the potential existence of such coalitions. We showed that both exogenous and endogenous factors have an important but waning influence on all elements of politicisation of the sanctions policy. With time, the politicisation seems to entrench itself into EUFP politics and follow its own dynamics. During the whole period, actors seemed to group themselves into two latent coalitions: one for and one against the policy. Finally, we contextualised these findings and pointed towards further avenues of researching the process of EUFP politicisation.

The paper will start with a brief overview of the existing theoretical and conceptual framework of politicisation of CFSP in which our research is positioned. After that, the methods used in this research will be explained; the possible shortcomings will be contemplated. The analysis will be divided into three parts – the first, focusing on descriptive statistics to study the traits of the politicisation, the second, utilising the programming language R to discover hidden patterns that could reveal latent coalitions of states regarding the sanctions policy. Finally, the results of the analysis will be contextualised in the area of politicisation of the CFSP and possible future avenues for research will be discussed.

Theoretical and conceptual framework

While the CFSP has always been contested and politicised to a degree, the dynamic of the process has shown some important novelties in the last two decades, during which we witnessed the erosion of the Western-led liberal world order, the Eurozone and refugee crises, Brexit, the Trump election and rise of populism (Cadier and Lequesne Citation2020). In this context, EUFP is increasingly being contested (especially at the intra-EU level) by new actors that form novel alliances and contest even deeply internalised foreign policy norms (Johansson-Nogués et al. Citation2020).

These dynamics have caught the attention of EU practitioners, who, in the opening paragraph of the EU’s Global Strategy, stress that the EU is being increasingly questioned (EUGS Citation2016). EU researchers, who have done individual studies (Koenig Citation2016, Costa Citation2019, Hegemann and Schneckener Citation2019), edited volumes (Góra et al. Citation2019, Johansson-Nogués et al. Citation2020), and special issues (Petri et al. Citation2020, Hackenesch et al. Citation2021) to study the politicisation of various aspects of EUFP, also point to the increased importance of the process of politicisation.

Although the case of EU’s response to the Ukraine crisis in general (and sanctions policy in particular) has already been analysed from various perspectives, such as evaluating their political impact (Dobbs Citation2017, Gould-Davies Citation2020), economic consequences (Moret and Shagina Citation2017), foreign policy analysis (David-Cross and Karolewski Citation2017), leadership theory (Schoeller Citation2020), the reasons for imposing the sanctions (Sjursen and Rosén Citation2017) or their long persistence (Portela et al. Citation2020), there still has not been a comprehensive study of the politicisation and contestation of the policy. We feel that the sanctions policy can serve as an excellent case study for revealing important insights on the dynamics and nature of the process of politicisation of CFSP, as sanctions are an integral tool for crisis response.

In its introductory paper, the authors (Biedenkopf et al. Citation2021) provide a systematic overview of how the concepts of politicisation and contestation have (sometimes inconsistently) been used and offer a new conceptualisation of the terms that can consistently be applied to studying the contemporary trends in the politicisation of CFSP. This paper is, in part, an exercise in applying their conceptualisation to a specific CFSP case. Hence politicisation is, in this context, understood as a process of change in which the scope of conflict within the political system expands (Biedenkopf et al. Citation2021, p. 10).

First, politicisation is operationalised in terms of change along three variables: issue salience (visibility), actor expansion (range), and actor polarisation (intensity and direction) (Biedenkopf et al. Citation2021, p. 6). Contestation, on the other hand, is considered as an instance in which an actor tries to undermine or displace an accepted or emerging norm or its understanding (Biedenkopf et al. Citation2021, p. 10).

Issue salience refers to the political significance of the issue to political actors in public debates and is considered a sine qua non element of politicisation, since an issue that is not salient (as in publicly debated) cannot be considered as politicised (Biedenkopf et al. Citation2021, p. 6). In our case we will measure issue salience by looking at the number of times a statement on the sanctions was given by a member of the European Council in a given timeframe.

Second, actor range has to do with the increasing number of (types of) actors involved in public debates, an expansion that can take place within and across political arenas (Biedenkopf et al. Citation2021, p. 6). In our case, we will look at the change in actor range within an institution by considering how many members of the European Council made at least one statement on the policy in the considered period. We will consider the European Council as a field or an arena of its own and the actor range rises if more and more actors get involved in the politicisation of the policy.

We posit that there is no need for a policy to enter the citizen arena to get politicised. However, just in case we did not miss something, we analysed if there were any public protests that could sway the European Council member’s position on sanctions. To observe if the case entered the citizen arena, we focused on finding the examples of public protests in member states. We could find rare instances of protests in citizen arenas: most notably, the 2015 farmers’ protests in some member states such as France, Belgium, Finland, and Poland (Dulingo Citation2016, Ruptly Citation2016, Lewandowski Citation2017). However, these protests were not aimed at challenging the sanctions policy (Miller Llana and Davidson Citation2015) and were of a limited size and frequency. This and the fact that the representatives in the European Council had not referred to any of the protests in their statements, in which they argue for and against the sanctions policy, allows us to posit that the spill-over, while present, can be considered insignificant. Therefore, the politicisation that occurs is independent of external actors and is contained within the institution.

Third, polarisation is the distance between the positions taken by different actors involved (Biedenkopf et al. Citation2021, p. 6). We will analyse it by looking at the standard deviation of the (coded) statements per month.

In the end, we conceptualised contestation as a statement which articulates the disagreement with (an aspect of) the EU sanctions policy. To further clarify how the statements were coded and how acts of contestation were identified, the criteria by which statements were coded (along with other methods utilised in this paper) will be explained in the next part of the paper.

Contestation (as an individual act at a point in time) and politicisation (as a process of increased conflict over a period of time) do not occur independently or without any prompting. Hence, we need to figure out what is the catalyst for the rise (and fall) of both politicisation and contestation. It is logical to assume situationally, those catalysts can come from within, i.e. be endogenous, or from outside, i.e. be exogenous to the political system and the actors deciding on the policy.

In our case, we defined exogenous influences as all those circumstances occurring on the ground, mostly between Russia and Ukraine, which were strong enough to elicit a response from the European Union. After analysing the time frame of the Ukraine crisis, we noted five such circumstances and named them turning points, as they were important enough to push the crisis to another level. These turning points are the annexation of Crimea (March 2014), the downing of Malaysia Airlines flight (July 2014), the Minsk Agreements, especially Minsk II (September 2014 and February 2015, respectively), and the Kerch Strait incident (November 2018). Three of them were defined as negative turning points (annexation, airplane downing, and Kerch Strait incident), as they had negative ramification on EU–Russia relations as well as negative consequences in Ukraine. The other two were defined as positive (two Minsk agreements), as they provided an opportunity for thawing of relations between the EU and Russia, as well as offered a way out of the Ukraine crisis.

When thinking about endogenous influences we focused on institutional and procedural opportunities political actors could use to influence the policy change. Because we focused on public statements given by the members of the European Council, and considering it was the European Council’s prerogative to decide on the introduction, the continuation, and the potential end of sanctions, we decided that the meetings of the European Council would be an optimal endogenous influence on politicisation and contestation. We named them policy cycle opportunities.

Methods

The focus of our analysis was members of the European Council, since sanctions policies have been decided at the highest level of the EU. However, due to the fact the European Council meetings, and positions stated there, are not open to the public nor publicly available, there is no way to directly study what is happening in their sessions. Since Portela already operationalised contestation, in the context of member states resisting sanction policies, as “expressed through the open opposition to the existence of the norm and its application” (Portela Citation2015, p. 45), we focus on public statements of members of the European Council as they represent the only manifestation of contestation members exercise that are available to the public. Even if they are mere “cheap talk”, as there was no vetoing of the policy, it was the only act of contestation that the actors deemed appropriate or available, and (finally) the only thing we could study. Therefore, we will study the statements as a heuristic proxy for position on the sanctions that members tried to promote in the European Council.

We focused on content analysis of formal and informal statements given by members of the European Council. Firstly, we performed a qualitative content analysis which allowed us to systematically analyse data in a verifiable way. The contestation statements’ database was obtained by utilising Boolean search queries in the Google search engine.Footnote2

The inclusion criteria for the statements were: the statement directly concerns the sanctions that the European Union enacted on the Russian FederationFootnote3, the statement was given by a member of the European Council, the statement was given between 1 March 2014 and 31 December 2019, the statement had to be given in or translated into EnglishFootnote4 and reported by a mainstream/respectable media outletFootnote5 or official governmental service. After the statements were gathered, they were coded according to their contestation level (as prescribed in this paper’s codebook).

The shortcomings of this method are the exclusion of all non-English statements, the potential bias of the Google search engine, and the dangers with translating by third parties (if the statement was made in the mother tongue of a European Council member, but then it was translated into English later on).

Another shortcoming could be our focus on publicly given statements by the members of the European Council, instead of focusing on official statements given during the meetings or on minutes taken, which would show us the deliberation process linked to building the common conclusion of the observed institutions. This focus on deliberation in an international organisation or a regime (which the EU certainly is), as a mode of contestation, is part of Wiener’s (Citation2014, Citation2017) operationalisation. However, the nature of the European Council makes it difficult for us to know how the deliberation process worked. The meetings are closed, the minutes of the meetings are all but non-existent, the conclusions do not reflect the nuances of the conversation, nor do they show conflicts between actors.

Hence, public statements by members of the European Council, although problematic, remain the only viable proxy for gathering and understanding specific positions of member states represented through their heads of state or government. We consider this approach satisfactory for reaching the research goals of this paper. To secure transparency and minimise any potential mistakes in handling the statements, the dataset used in this study is publicly available (see Data availability statement).

We have gathered and analysed 223 statements on the European Union’s sanctions against Russia. The gathered statements were coded by attributing them a contestation value – a numerical scale ranging from 1 to 5, with 1 corresponding to a “completely supports sanctions” statement and 5 corresponding to a “completely opposes sanctions” statement.Footnote6 The statements were coded three times independently – once by each of the paper’s authors and once by an independent expert associate – to minimise subjectivity in coding. The coding results were afterwards compared, and in the instances of mismatch of coding, the statements and their corresponding codings were debated and ultimately a value was agreed upon by all three coders.

The database was then put through the latent class analysis (LCA) model using the poLCA package in R, which is designed to uncover hidden groupings in data (Linzer and Lewis Citation2011). More specifically, it is a way to group subjects from multivariate data into “latent classes” – groups or subgroups with similar, unobservable, membership (SHT Citation2015).

We also used descriptive statistics to analyse the coded data. We showed frequencies of the coded statements throughout the researched period, as well as the main political actors who contested and supported sanction.

Analysis

In this part of the paper we will, first, show the results for (and the interplay between) the three elements – actor range, salience, and polarisation – that are important for understanding politicisation of the sanctions policy, based on the descriptive statistics and on bivariate analysis, gauging potential correlations between the analysed elements. These results will help us answer our main research question. We will take into account exogenous (turning points) and endogenous (policy cycle) influences to see the similarities and differences between politicisation variables and to offer an explanation of their interaction.

Afterwards, we will analyse the potential existence of latent coalitions, considering that any contestation of a policy should pitch at least two (groups of) contesting sides against one another. This would, in turn, help us answer our secondary research question.

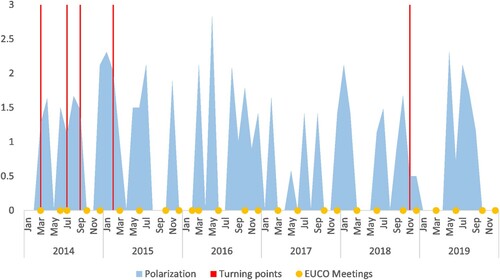

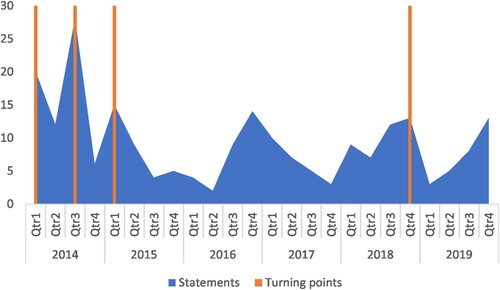

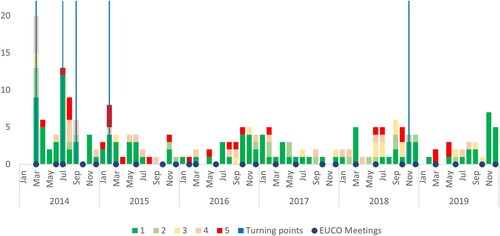

shows the statements (N = 223) regarding the Russian sanctions made by members of the European Council, from March 2014 to December 2019, together with major turning points and EUCO meetings. The data revealed several interesting facts.

Figure 1. Overview of all statements on the sanctions policy by members of the European Council, Citation2014–2019. Source: Authors’ calculations.

The salience (presented as the overall number of statements given by political actors in the public arena) of the sanctions policy remained more or less stable after it skyrocketed at the beginning of 2014 in the wake of Russia’s annexation of Crimea (see and Figure A1 in appendix). This is consistent with our expectations, as the logic leads us to see the spike in both the supporting and the contesting statements just before and just after a specific policy was set in place. In the case of the EU’s Russia sanctions policy, this happened in early 2014. Additionally, it is visible that the dates of the EUCO meetings (which can be used as opportunities for lifting the sanctions) mostly do not affect salience, as spikes occur independently of the once-in-a-quarter dynamic.

Table 1. Total number of statements given by members of the European Council regarding Russia sanctions.

However, if one focuses on temporally based variations to see more detailed spikes of politicisation and/or contestation, we posit that these are linked to major turning points based on the situation in Ukraine. To analyse the turning points’ impact on politicisation, we used quarters as a temporal measure (see Figure A1 in the appendix), based on the fact that the regular European Council meetings occur four times per year. Hence, each quarter should have at least one meeting, and therefore, at least one opportunity for political actors to contest or support policy in public. When checking our data based on these prepositions, it is obvious that four out of six quarters – Qtr1 and Qtr3 in 2014, Qtr1 in 2015, and Qtr4 in 2018 – with the highest number of statements, were those in which major turning points occurred. Therefore, in general, turning points have a bigger impact on salience than the policy cycle.

If we only look at the contestation of sanctions, it remained ever present in the examined period (Figure A2 in appendix), including in the “frozen conflict” years, between 2016 and 2019. It seems that turning points have a lower direct influence on contestation than they have on salience. Since contestation of the sanctions policy happened throughout the observed period, with turning points being only one element in the complex inter-actor, inter-state, and inter-institutional web of activities. In , we show the average support for the sanctions per year. The lower the number, the stronger the support for maintaining and/or strengthening the sanctions against Russia. The average level of support remained stable, never crossing 2.5, which means that overall, members of the European Council publicly showed support for the policy in place, even in the periods when levels of contestation and the number of contesting actors grew.

Table 2. Average support for sanctions, per year.

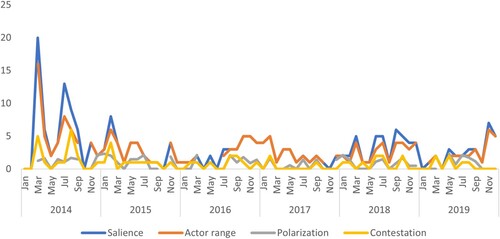

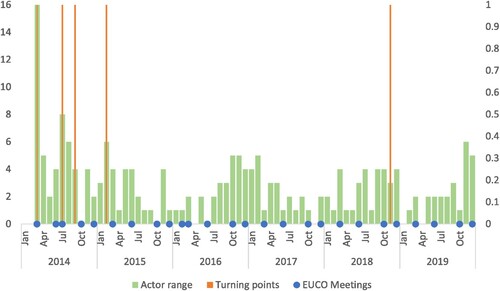

Next, we turn to analysing actor range. shows the number of members of the European Council who made at least one statement on the sanctions per quarter. We will use this as a proxy for analysing actor range in this case. Similarly to salience, the actor range was highest in the beginning of the Crimean crisis; it had two smaller, albeit prominent, spikes during the next two turning points, and then remained stable over the rest of the examined period. Hence, actor range seems to be more closely tied to turning points than the policy cycle. However, neither the turning points or the policy cycle can account for the dynamics of the actor range after 2015.

Figure 2. Number of actors who made statements on the sanctions per month. Source: Authors’ calculations.

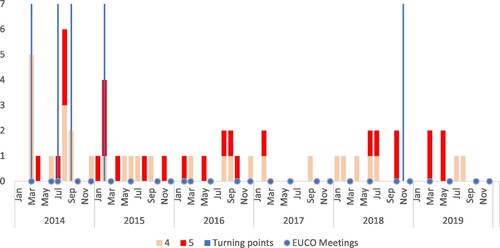

For polarisation we calculated the standard deviation of given statements per month. The lower the standard deviation, the more unity there is on the policy, and vice versa, the higher the deviation, the greater the distance between the attitudes on the policy (and, therefore, the higher the polarisation). shows the polarisation per month, revealing that the polarisation was not constant, but rather rose and fell seemingly independently from major turning points or EUCO meetings. It also did not slow down or disappear with the passing of time, continuing its own dynamic, hinting that the polarisation on key issues in CFSP was here to stay.

If one now compares the change in the three dimensions of politicisation alongside each other it looks like all three dimensions follow similar paths, although salience and actor range are more synchronised with one another than with polarisation. This is logical, as it is expected for the number of statements to rise (salience) with the increase of the number of political actors involved in contesting (or supporting) the policy (actor range). A correlation analysis (on data points per month) supports that argument. As reveals, there is a significant correlation between all three dimensions of politicisation: a strong relationship between salience and actor range, as well as a moderate relationship between polarisation and salience, as well as polarisation and actor range.

Table 3. Correlation Matrix of salience, actor range and polarisation per month (N = 72).

Since the three dimensions rise and fall during the timeline, it seems that politicisation is a reversible process: politicisation can expand as a reaction (to an exogenous or an endogenous event), then shrink (and possibly expand again) as the time passes ().

In the next part of the paper, the data will be analysed to explore if states (that is, their representatives in the European Council) can be grouped into what will be labelled “latent coalitions”. This will help us answer our secondary research question. However, we will also be able to use that answer to give support to Biedenkopf et al. (Citation2021) hypothesis of the existence of communitarian–cosmopolitan cleavage within the European Council, as the cleavage cannot exist without the existence of at least two conflicting groups of actors standing on either side of the cleavage.

The statements were analysed using the poLCA package in R.Footnote7 The fit for two latent classes (BIC(2): 2092.785) showed that, with a 91.47 per cent probability, a latent class exists with membership of the statements with a contestation value of 1 (very supportive of sanctions).

We will use this very probable latent class in the data as a proxy for our Coalition 1 – the coalition of states that actively promote the sanctions policy. As for concrete member states and their membership in Coalition 1, the LCA shows, with a strong probability, that the following states are members of the pro-sanctions Coalition 1: Estonia, Germany, UK, and the EU (the President of the European Commission and the President of the European Council). Additionally, Finland, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, and Sweden have a lower probability of being a member of Coalition 1, and also have a zero per cent chance of being in the other latent class. Therefore, we will include them in Coalition 1, as well.Footnote8

The LCA did (with a more or less significant probability) place Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Luxembourg, and Slovakia in the opposing class. However, that class, which consists of instances of lower support, has a much lower probability of existence, so we will not use it to identify our Coalition 2. Therefore, we will need to use other means in identifying our Coalition 2 – the states that actively contest the sanctions policy.

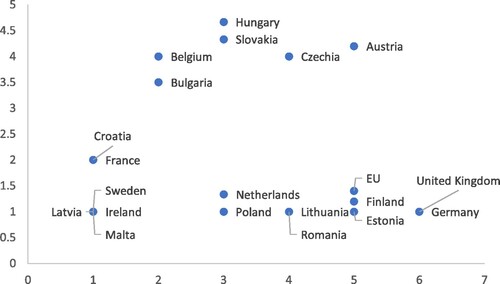

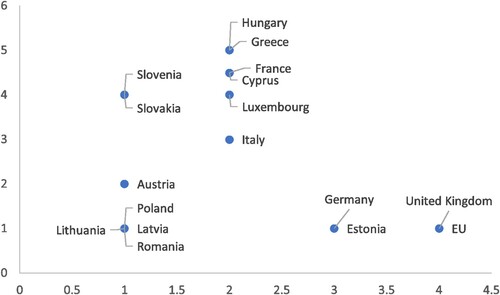

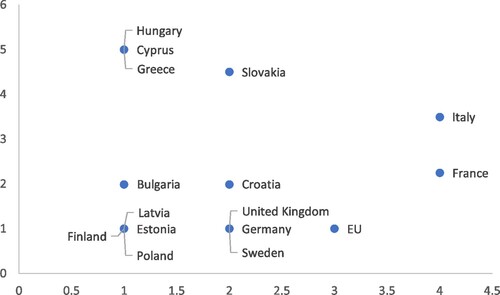

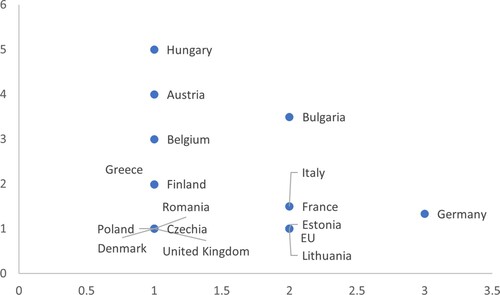

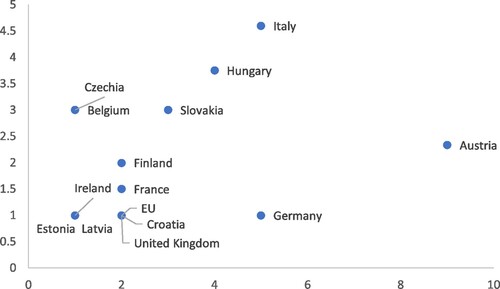

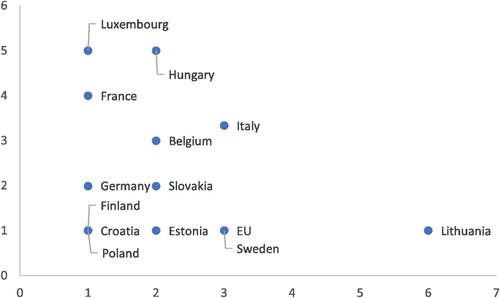

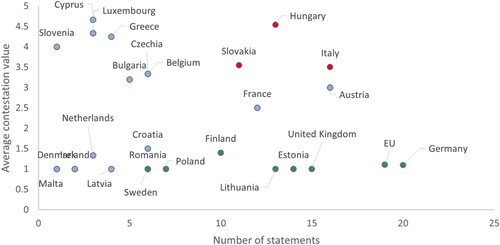

We started the search for Coalition 2 (the contesting coalition) by looking at the country-specific level of contestation. From the total number of statements given by a representative of the member state in the European Council we extrapolate the average level of contestation. The larger the average number, the higher the contestation level of sanctions. The total number, in turn, allows us to see the level of salience of that question per country, either in defence of or in opposition to the sanctions. Hence, the combination of those two values allows us to combine both contestation and politicisation and analyse the specific position of the member state on the contestation–salience matrix.

shows that most of the actors are grouped into one of the four groups. We determined two criteria of demarcation. The first is the average contestation value (high if ≥3.5, neutral if between 3.5 and 2.5, and low if ≤2.5). The second is the number of statements made, which shows the salience of the policy to a particular actor. Since there is a “natural” gap, with no member states giving between 7 and 10 statements, we took eight statements as the criteria of salience. Less than eight is interpreted as the policy not being salient for an actor (taking into account the limitation of not knowing how many statements an actor makes overall, which would maybe give us a different picture of actor’s policy salience), with more than eight statements showing ever stronger salience of the policy for a specific member state.

Figure 5. Contestation-salience matrix regarding EU’s Russia sanctions (entire period). Source: authors’ calculations.

The first group consists of member states with high levels of contestation and high levels of salience. The second group is made of member states that were highly contesting the policy but have not made many statements. The third group contains member states with low levels of contestation and low levels of salience, while the fourth group consists of those countries that were supporting sanction (low level of contestation) and were vocal about it (high level of salience).

When taken into context, the first group (marked by high contestation and high salience) can clearly be identified as the Coalition 2, the latent coalition of the European Council members who actively and vigorously contest the sanctions policy. This coalition comprises Slovakia, Hungary, and Italy.

Discussion

Taking into account the interplay between exogenous and endogenous factors influencing the sanctions policy, it is evident that in the case of the Ukraine crisis, the turning points were the drivers of the policy cycle activities. It is not surprising that the turning points (external factors) had a bigger, albeit varied, impact on salience, actor range, and contestation than on the policy cycle.

The first turning point (Crimean annexation) influenced the start of the policy cycle activities by introducing sanctions as the only viable response of the European Union to the situation on the ground. The course set by that first turning point was strengthened by the second turning point – the downing of the Malaysia Airlines flight – while the fifth turning point, the Kerch Strait incident, stopped any talk of easing the sanctions and helped the pro-sanctions actors to continue with their imposition. These three major exogenous events, in which Russia played a major negative role, had a much stronger influence on the sanctions policy than the two positive ones – the two Minsk Agreements, especially Minsk II.

This means that positive turning points, although used by sanctions contestors as an argument for ending the sanctions, could not change the course of this specific foreign policy of the EU. One of the explanations for this is that the negative turning points were much immediate, necessitated strong EU response, and threatened the established liberal order (especially the inviolability of internationally recognised state borders). On the other hand, positive turning points were seen only as promises that would potentially bear fruit in the uncertain future, with Russia gaining a lot reputationally without losing anything at the time of the signing of the agreements. The contestors of the sanctions gained no leverage from the positive turning points to convince the other political actors the sanctions should be lifted.

However, the passage of time can offer the contestors opportunity to point to how ineffective the policy is, thus offering other options (negotiations, re-evaluation) for breaking the impasse. This happened in our case, too. The rise of contestation during 2018 was cut down by the negative turning point, the Kerch Strait incident, after which any contestation completely disappeared for the next three months. The incident also cut down all polarisation, as was expected with such a steep drop of contestation of the policy.Footnote9 This leads us to conclude that with time, the windows of opportunity for internal contestation arise, which can be closed by negative external events. What would happen if there was no negative turning point? Would the contestors manage to convince the pro-sanctions actors for the need to end the sanctions policy? We cannot say with certainty, but we can show what the data allude.

Since four of the five turning points occurred within a year of the start of the crisis, there was a long period of time when exogenous factors could not directly affect the level of politicisation (through its three dimensions). In this period, there are other factors that could have driven politicisation, which had seemingly developed its own dynamics during 2016, 2017 and most of 2018.

Considering that politicisation existed in that period as well, and that policy cycle, per analysis, did not play a major role in that period either, we concluded that, like in many similar situations, the policy developed an autonomous life of its own and turned into a phase of entrenched politicisation. As the conflict in Ukraine entered the frozen conflict period, the contestors had no exogenous factors to use to overturn the policy, while the pro-sanctions side just had to rely on the nature of the policies to maintain status quo in the face of no visible (or even symbolic) change that would compel them to act differently and change their course (take into account the long life of US sanctions against Cuba, or the decade-long Western sanctions against the Milosevic regime in Serbia/Yugoslavia). At the same time, other events and crises (Brexit, the refugee issues, terror attacks) asked more and more time of the members of the European Council, thus pushing the Russia sanctions question to the margins of the policy cycles.

To conclude this part of the research and to answer the main research question, we posit that, overall, European Council members supported the sanctions (if viewed by the average support per year). The continuation of the sanctions was linked to the fact that the pro-sanctions coalition was larger and more powerful. At the same time, the polarisation had its own dynamics and can be used to explain the existence of entrenched politicisation that keeps occurring more and more in the conflict between member states and EU institutions in establishing and maintaining important policies and creating coalitions of actors in EUFP.

Correlation between three dimensions of politicisation exists and is understandable. The more actors there are who debate a specific issue, the more statements there will be, and the more the chance that there will be statements which differ, i.e. that are polarising. At this point, of course, we cannot show which element causes the rise in others, but we know that correlation among them exists.

To fully understand the findings and implications of the analysis, it is necessary to contextualise it. The debate on the Russian sanctions is defining EU foreign and defence policy towards, and relationship with, the most important third country on its borders. The stakes are, arguably, very high and individual member states’ (both short- and long-term) interests are sometimes clashing.

The analysis revealed the existence of that clash in regard to the sanctions policy in the existence of two opposing latent coalitions of members. The first, Coalition 1, consists of Estonia, Germany, UK, the EU (the President of the Commission and the President of the European Council), Finland, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, and Sweden. This coalition encompasses some of the politically and economically most powerful EU member states. By sheer number, let alone by the population and the economic power, it is by several degrees of magnitude more powerful than Coalition 2, which consists of Slovakia, Hungary, and Italy.

We showed that the member states were grouped in two distinct clusters. This means that sanctions policy towards Russia birthed two potential, or latent coalitions of countries, pushing for opposing policies, similar to what Schoeller (Citation2020) posited in his paper.

The actor range (of members of the European Council who made statements on the sanctions) hit a high in 2014, dropped and, while fluctuating from quarter to quarter, stayed consistent in the remaining years similarly to what happened with the salience level. Additionally, the level of polarisation between statements was constantly changing, revealing a dynamic that was strictly tied neither to the major turning points in Ukraine nor to the EU policy cycle.

All these characteristics lead us to the conclusion that the case reached an elite politicisation level, that is: “a CFSP debate involving an expanded range of participants can be seen as one that is salient among state representatives” (Biedenkopf et al. Citation2021, p. 12). Furthermore, lack of interest for the policy outside the elite level stopped the spill-over effect to other levels, most notably the level of the general public, where the politicisation of the policy would deal a completely new variable into contestation practice. While there are some instances of the public’s involvement in the debate over the sanctions policy (through protests), which would technically put this case somewhere in between the elite politicisation and mass mobilisation stage, those instances were sparse and relatively uninfluential. Therefore, utilising the typology of the contestation of European integration described in the theoretical framework of this paper, we argue that our example falls (in varying degrees) in the elite politicisation category.

Conclusion

The core finding of this paper is that both exogenous and endogenous factors have an important but waning influence on the sanctions policy as the time passes. Since that start of the crisis and the introduction of the sanctions, politicisation (as observed through the changes occurring in its three dimensions) becomes more divested from both the turning points and the policy cycles. It sustains itself autonomously, mostly through institutional and policy inertia. Hence, the case we analysed could be considered an example of entrenched politicisation.

Another, more methodological conclusion is that by studying the public statements it is possible to understand the process of politicisation and see that it is only loosely linked to the situation in Ukraine, that it is continuous, and that it reveals the existence of two coalitions on the issue.

Furthermore, while there were some instances of politicisation of the policy in the citizens arena, they were arguably not sufficient for labelling this case as reaching the mass mobilisation stage of politicisation. The politicisation mostly remained within the confines of the European Council and was marked by the existence of two latent coalitions. In them, actors exposed two opposing views on the sanctions policy. We, hence, identify this case as an example of elite politicisation.

There are several novel elements in our paper that give added value to the current body of knowledge on the topic. First, we study the case (but indirectly the institution of the European Council, as well) in the context of EUFP politicisation and we analyse public statements in a way that yields findings that can provide insights into the process of politicisation (its findings are in line with other studies, which boosts trustworthiness).Footnote10 This method, hence, can be used in other cases and advance the field.

Next, our overview of the process showed that the longer the crisis lasts and the longer the sanctions policy is in its place, the politicisation has less to do with the situation on the ground and with internal factors, developing instead an autonomous nature of its own and becoming entrenched.

Finally, our discovery of the existence of two coalitions could point to the existence of the communitarian–cosmopolitan cleavage in EU politics. This, in turn, could help prove an important element as theorised by Biedenkopf, Costa, and Gora (2021) in the introductory article to this special issue. However, further research is needed to claim the existence of the cleavage confidently.

On the other hand, there are several limitations of our study, as well. Using public statements as a proxy of the position of an actor in the European Council might lead to false conclusions, as those actors can espouse one idea in public, while another behind closed doors. Methodological weaknesses, especially the focus on statements in English, have already been covered, but must be taken into account.

The limitations of this research are most strongly linked to the limited sample of the statements that the authors were able to collect and analyse. With more resources perhaps statements from all members of the European Council (given in their national language to their national media) could be collected and, therefore, make the sample more representative.

Overall, our results allow us to give conclusions on the nature of the EU’s CFSP and the power of the European Council to shape it in the climate of increased politicisation. It is obvious that every policy can be politicised, including those dealt with at the highest level of the political system. Politicisation of foreign and security policy is helped by the division in the European Council, practised through implicit or explicit coalition–building among conflicted member states. It is as successful as the leaders of those coalitions are successful in keeping the contested policy on the table. However, how these informal coalitions are built and why they exist in the first place cannot be posited from this research.

The future research on this topic needs to focus on connecting instances of politicisation with other relevant events such as voting in the European Council (to see if a contesting statement, if not followed with a vote against the sanction, even matters), the position of other major international actors, as well as official meetings between members of the European Council (in their capacity as national leaders, either bilaterally or multilaterally) and their Russian counterparts.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Lana Bojanić from the University of Manchester for her help on the latent class analysis in the paper. Also, a special thanks to Valentino Petrović, a Masters student at the Central European University, who was the third coder in this paper, for his help in coding the statements database. In the end, the authors would like to thank Oriol Costa Fernandez and Magdalena Gora, as well as the attendees of Porto and Vienna COST workshops, for their valuable inputs.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13238015.v1.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Schoeller (Citation2020, p. 1109) conducted interviews and found that in July 2014, “Poland, the Baltic states, Sweden, Denmark, and partly the UK were in favour of further [N.B. economic] sanctions, a counter–coalition including Italy, France, Austria, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Bulgaria, Greece, and Cyprus initially opposed them”. We, therefore, expect to find two prominent coalitions, one pro sanctions (Poland, the Baltic States, Sweden, Denmark, and, perhaps, the UK) and one against sanctions (Italy, France, Austria, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Bulgaria, Greece, and Cyprus).

2 For each member of the European Council the corresponding search term in the form “full name”+russia+sanctions (e.g. viktor+orban+russia+sanctions) was used. Data range was set from 1 March 2014 to 31 December 2019. The search results were narrowed down to only include results in English. Similarly, to determine if the politicisation of the sanctions reached the public domain, a Boolean search query (EU+Russia+sanctions+protest) was performed. Protests (as a political act) would indicate clear public involvement in the politicisation of the sanctions.

3 And not, for instance, the U.S. sanctions on Russia enacted in 2017.

4 Statements in English are chosen for two reasons. The first reason is technical in nature. Due to time and finance restrictions, we could not include all European languages. However, this should be done at some point. The second reason was the nature of contestation. Due to discrepancies between how some political actors acted in the European Council (voting for sanctions) and how they acted in public when commenting it (criticising sanctions), combined with overall lack of polarisation the topic of Russian sanctions opened on the domestic level of member states, our position is that English language statements were aimed at the Russian counterparts as well as potential partners among member states.

5 By mainstream/respectable media we consider national and international news agencies, as well as those media of both national and international renown which affords them the opportunity to be considered “the papers of record”.

6 The intensity of the statement merited the position on the scale. If it could be derived from the statement that an actor completely opposed (or supported) sanctions, the statement was attributed with maximum values. If an actor supported sanctions but opposed further steps in the process or was against sanctions but supported specific action taken as a response to an event on the ground, we attributed intermediate (2, 4) values to those statements. If the statement was neutral as to the direction the sanctions policy should go, we coded it as 3.

7 The full results of the LCA can be found in the appendix of this paper.

8 Some member states’ statements were not frequent enough for them to be placed in one of the classes. That is why Croatia, Czechia, Denmark, Ireland, Latvia, Malta, the Netherlands, and Slovenia are between two classes based on the LCA. The case of France is peculiar as well. It is not a part of either of the coalitions (average values of 2,5), which can be explained by the lack of consistency in statements due to exogenous reasons (elections brought the change of the president). Portugal and Spain were not included in the analysis because no statements of their members of the European Council regarding the sanctions policy could be found in English.

9 Similar things did not occur after the second turning point, because, unlike the Kerch Strait incident, it was not immediately apparent who the culprit was. Although at the time many insisted that Russia was to blame, directly or indirectly, for the downing of the Malaysia Airlines plane, Putin regime vehemently denied it, giving the contestors of the sanctions policy opportunity to continue to politicise the issue further.

10 It also has some advantages over, for instance, doing elite interviews, which have numerous drawbacks such as unavailability of the interviewers, unreliability of their answers, the fact that this is just a snapshot in time, and can hardly reveal anything about the process of politicisation. Our method, on the other hand, is standardised, the statements are public, easily replicable, does not rely on the memory or honesty of the interviewee and can paint a picture of the whole process of politicisation.

References

- Biedenkopf, K., Costa, O., and Gora, M., 2021. Introduction. Shades of contestation and politicisation of CFSP. European Security, 30 (3).

- Cadier, D. and Lequesne, C. 2020. How populism impacts EU Foreign Policy. EU-Listco: Policy paper series, 8.

- Costa, O., 2019. The politicization of EU external relations. Journal of European public policy, 26 (5), 790–802.

- Davis-Cross, M.K. and Karolewski, I.P., 2017. What type of power has the EU exercised in the Ukraine-Russia crisis? A framework for analysis. JCMS: Journal of common market studies, 55 (1), 3–19.

- Dobbs, J. 2017. “The Impact of EU-Russia Tensions on the Politics of the EU and Its Member States: Insecurity and Resolve.” In L. Kulesa, I. Timofeev, and J. Dobbs, eds., Russia Damage Assessment. London: European Leadership Network, 31–38.

- Dulingo, R., 2016. EU policy towards Russia increases euroscepticism. Global Risk Insights, 13 May. Available from: https://globalriskinsights.com/2016/05/euroscepticism/ [Accessed 20 September 2020].

- European Council, 2014. Joint statement on Crimea by President of the European Council Herman Van Rompuy and President of the European Commission José Manuel Barroso. European Council. Available from: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_Data/docs/pressdata/en/ec/141566.pdf [Accessed 24 June 2019].

- EUGS, 2016. Shared vision, common action: a stronger Europe. A global strategy for the European Union’s foreign and security policy. Brussels: European External Action Service.

- Góra, M., Styczyńska, N., and Zubek, M., eds., 2019. Contestation of EU enlargement and European neighbourhood policy. Actors, arenas and arguments. Copenhagen: Djøf Publishing.

- Gould-Davies, N., 2020. Russia, the West and sanctions. Survival, 62 (1), 7–28.

- Hackenesch, C., Bergmann, J., and Orbie, J., 2021. Development policy under fire? The politicization of European external relations. JCMS: Journal of common market studies, 59 (1), 3–19.

- Hegemann, H. and Schneckener, U., 2019. Politicising European security: from technocratic to contentious politics? European security, 28 (2), 133–152.

- Huff, A., 2015. Executive privilege reaffirmed? Parliamentary scrutiny of the CFSP and CSDP. West European politics, 38 (2), 396–415. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2014.990697.

- Johansson-Nogués, E., Vlaskamp, M.C., and Barbé, E., 2020. EU foreign policy and norm contestation in an eroding Western and intra-EU liberal order. In: E. Johansson-Nogués, M. Vlaskamp, and E Barbé, eds. European Union contested. Norm research in international relations. Cham: Springer, 1–17.

- Koenig, N., 2016. Multilevel role contestation: the EU in the Libyan crisis. In: C. Cantir and J. Kaarbo, eds. Domestic role contestation, foreign policy, and international relations. New York: Routledge, 157–173.

- Koenig, N., 2019. Bolstering EU foreign and security policy in times of contestation. Berlin: Jacques Delors Institutes.

- Lewandowski, W., 2017. EU sanctions against Russia, and their future. Livingston, 6 February. Available from: https://www.livingstonintl.com/eu-sanctions-russia-future/ [Accessed 20 September 2020].

- Linzer, A. and Lewis, J.B., 2011. poLCA: An R package for polytomous variable latent class analysis. Journal of statistical software, 42 (10), 1–29.

- Miller Llana, S. and Davidson, C. 2015. How a farmers’ strike in France is challenging EU core ideals. The Christian Science Monitor, 13 August. Available from: https://www.csmonitor.com/World/Europe/2015/0813/How-a-farmers-strike-in-France-is-challenging-EU-core-ideals [Accessed 20 September 2020].

- Moret, E. and Shagina, M., 2017. The impact of EU-Russia tensions on the economy of the EU. In: L. Kulesa, I. Timofeev, and J. Dobbs, eds. EU-Russia damage assessment. London: European Leadership Network, 17–24.

- Pastore, G., 2013. Small new member states in the EU foreign policy: toward “small state smart strategy”? Baltic journal of political science, 0 (2), 67–84.

- Petri, F., Thevenin, E., and Liedlbauer, L., 2020. Contestation of EU foreign policy. Global affairs, 6 (4-5), 323–328.

- Portela, Clara, 2015. Member states resistance to EU foreign policy sanctions. European foreign affairs review, 20 (2015), 39–61.

- Portela, C., Pospieszna, P., Skrzypczyńska, J., and Walentek, J., 2020. Consensus against all odds: explaining the persistence of EU sanctions on Russia. Journal of European Integration, doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2020.1803854

- Ruptly, 2016. Finland: Finnish farmers protest financial woes as Russia sanctions start to bite [video file]. YouTube, 11 March. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E7QpoYVWzWY [Accessed 24 June 2019].

- Schoeller, M.G., 2020. Tracing leadership: the ECB’s “whatever it takes” and Germany in the Ukraine crisis. West European politics, 43 (5), 1095–1116.

- Sjursen, H. and Rosén, G., 2017. Arguing sanctions. On the EU’s response to the crisis in Ukraine. JCMS: Journal of common market studies, 55 (1), 20–36.

- Standard Eurobarometer 92, 2019. Europeans’ opinions about the EU’s priorities. Brussels: European Commission.

- Statistics How To. 2015. “Latent Class Analysis/Modeling: Simple Definition, Types”. Statistics How To, 31 July. Available from: https://www.statisticshowto.com/latent-class-analysis-definition/ [Accessed 21 June 2021].

- Wiener, A., 2014. A theory of contestation. Mannheim: Springer.

- Wiener, A., 2017. A theory of contestation – a concise summary of its argument and concepts. Polity, 49 (1), 105–125.

Appendix

Latent Class Analysis

Conditional item response (column) probabilities, by outcome variable, for each class (row)

$StateNo

Pr(1) Pr(2) Pr(3) Pr(4) Pr(5) Pr(6) Pr(7) Pr(8) Pr(9) Pr(10)

class 1: 0 0.1606 0.071 0.0591 0.0153 0.0355 0.0591 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

class 2: 0 0.0175 0.000 0.0000 0.0340 0.0000 0.0072 0.0072 0.1011 0.1372

Pr(11) Pr(12) Pr(13) Pr(14) Pr(15) Pr(16) Pr(17) Pr(18) Pr(19) Pr(20)

class 1: 0.0000 0.0833 0.0000 0.0473 0.1537 0.0000 0.1503 0.0000 0.0000 0.0355

class 2: 0.0722 0.0358 0.1445 0.0000 0.0000 0.0144 0.0238 0.0289 0.0939 0.0000

Pr(21) Pr(22) Pr(23) Pr(24) Pr(25) Pr(26) Pr(27) Pr(28)

class 1: 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 0.1175 0.0118 0.0000 0.0000

class 2: 0.0072 0.0217 0.0506 0.0433 0.0077 0.0000 0.0433 0.1084

$CV

Pr(1) Pr(2) Pr(3) Pr(4) Pr(5)

class 1: 0.0000 0.1249 0.2129 0.3548 0.3075

class 2: 0.9174 0.0826 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

Estimated class population shares

0.3792 0.6208

Predicted class memberships (by modal posterior prob.)

0.3857 0.6143

=========================================================

Fit for 2 latent classes:

=========================================================

number of observations: 223

number of estimated parameters: 63

residual degrees of freedom: 76

maximum log-likelihood: -858.4955

AIC(2): 1842.991

BIC(2): 2057.643

G^2(2): 83.12604 (Likelihood ratio/deviance statistic)

X^2(2): 75.18546 (Chi-square goodness of fit)

> levels(data$State)

[1] “Austria” “Belgium” “Bulgaria”

[5] “Croatia” “Cyprus” “Czechia” “Denmark”

[9] “Estonia” “EU” “Finland” “France”

[13] “Germany” “Greece” “Hungary” “Ireland”

[17] “Italy” “Latvia” “Lithuania” “Luxembourg”

[21] “Malta” “Netherlands” “Poland” “Romania”

[25] “Slovakia” “Slovenia” “Sweden” “United Kingdom”