ABSTRACT

In a relatively short time, cybersecurity has risen to become one of the EU’s security priorities. While the institutionalisation of EU-level cybersecurity capacities has been substantial since the first EU cybersecurity strategy was published, previous research has also identified resistance from member states to allow the EU to have more control over their cybersecurity activities. Despite a growing literature on EU cybersecurity governance, there are currently extensive gaps in the understanding of this tension. This study suggests that an explanatory factor can be found in the so-far overlooked dynamic of the relative prevalence of risk vs. threat-based security logics in the EU cybersecurity approach. By distinguishing between risk and threat-based logics in the development of the EU cybersecurity discourse over time, this study highlights a shift towards an increasing threat-based security logic in the EU cybersecurity approach. The identified development highlights securitising moves enacting to a larger extent than before objects and subjects of security traditionally associated with national security. The study identifies specific areas of member state contestation accompanying this shift and concludes with a discussion on the findings in relation to the development of the EU as a security actor in the wider international cybersecurity landscape.

Introduction

Few security fields have emerged and developed so quickly and comprehensively as the cybersecurity field. In two decades, cybersecurity has gone from being a relatively minor security concern managed by experts to being at the top of security policy agendas of states, international and supranational organisations – including the European Union (EU). Reflecting its rising strategic importance, cyberspace has become an arena of national and international contestation, as different actors try to shape and influence the governance of it (Radu et al. Citation2014, Deibert Citation2016).

Meanwhile, the number of actors involved in the governance of cyberspace and the variety of institutional and legal approaches and solutions adopted to govern it have contributed to conceptual confusion around what cyberspace is, what it should be, and how it should be governed (Pawlak and Missiroli Citation2019). This diffusion is enhanced by the elusive characteristics of cyberspace, such as its tendency to blur important dichotomies (Carrapico and Barrinha Citation2017), its cross-jurisdictional and ambiguous nature (Christou Citation2016), and that it is global and transboundary, but not stateless. While being virtual, cyberspace is still tied to physical infrastructure, and its users to geographical locations.

This elusiveness has also been expanded to the concept of cybersecurity, reflected in the plethora of government perceptions of cybersecurity and how it should be managed (Pawlak and Missiroli Citation2019). Cybersecurity is a concept that is currently being defined, shaped and redefined as a public policy problem in various contexts and arenas, with implications for its governance. Despite a rising scholarly interest in studying the EU as a cybersecurity actor, relatively few studies have so far focused on exploring this ongoing process in the context of the EU. Furthermore, while previous research has indicated that ambitious EU cybersecurity initiatives have been accompanied by governance challenges and member state contestation accompanied governance challenges and member state contestation (Bendiek et al. Citation2017, p. 7, Carrapico and Barrinha Citation2017, p. 11), the specifics of this contestation have so far been extensively underexplored.

This study aims to contribute to bridging this gap by examining the relative prevalence of risk vs. threat-based security logics in the development of the EU cybersecurity discourse over time, identify specific areas of member state contestation and governance challenges accompanying this development, and explore the relationship between them. In doing so, the study seeks to contribute to the understanding of how cybersecurity as a public policy problem is being defined and redefined at the EU level, and to further explain member state resistance to specific EU cybersecurity initiatives.

The study draws data from 13 interviews with cybersecurity officials from four countries as well as practitioners previously or currently working within EU cybersecurity initiatives and/or agencies. These data are combined with analysis of key EU strategy and negotiation documents.

The EU as a cybersecurity actor

Following the rise of the EU’s ambitions and capabilities in the cybersecurity field, scholars from various strands have increasingly turned their attention to analysing the EU’s cybersecurity practices. A relatively large part of current contributions has so far come from governance perspectives, perhaps as a result of thriving cyber governance literature and debate more broadly. There are indeed considerable parallels between the current body of contributions on the EU as a cybersecurity actor and contributions within the cyber governance literature. Studies in the latter category have predominantly focused on the changed conditions for governance created by cyberspace (e.g. Brown and Marsden Citation2013, Scholte Citation2017), emerging norms in cyber space (for example, Iasiello Citation2016, Adamson and Homburger Citation2019) and contributions focusing on the nascent international cyber regime complex (Raymond Citation2016, Pawlak Citation2019). This has included the identification of internet governance as characterised by “trans-scalarity, trans-sectorality, diffusion, fluidity, overlapping mandates, ambiguous hierarchies and a post-sovereign absence of a single and consistent supreme authority” (Scholte Citation2017, p. 182).

Similarly, the literature on EU cybersecurity has had a predominant focus on what the transboundary nature of cyber means for the EU’s cybersecurity governance efforts and prospects, and to identify its emerging cybersecurity governance structures and practices. Echoing the findings of the broader cyber governance literature, authors have highlighted the difficulty for the EU to achieve coherence in a field that questions important dichotomies both vertically (national, European and global) and horizontally (internal/external, private/public and civilian/military) (Carrapico and Barrinha Citation2017, p. 2). As described by Christou (Citation2019), the EU cybersecurity governance system is underpinned by three interrelated mandates: Freedom, Justice and Security (AFSJ), the Internal Market and the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP), which exist in a complex set up within multiple spaces (Christou Citation2019, p. 279).

Within this context, much focus has been directed toward understanding the intricacy of the EU as an evolving cybersecurity actor.

On the one hand, authors have identified an increasing institutionalisation of cybersecurity capacities at the EU level. This has included the continuous development of EU-level cybersecurity agencies and an emerging “cybersecurity community” across EU institutions (Carrapico and Barrinha Citation2017). While not wielding coercive cyber power, the EU has, as noted by Dunn Cavelty (Citation2018), developed into an institutional cyber power, with a wide range of instruments, platforms and voluntary as well as mandatory requirements at its disposal (Dunn Cavelty Citation2018, p. 315). Studies have also identified the EU as a securitising actor in the field of cybersecurity. A notable example can be found in the study by Christou (Citation2019), pointing to a continuous process of collective securitisation:

Consistent with collective securitization we have seen securitising moves by authoritative EU institutional actors as a result of a series of events and trends, in this case followed by member state agreement to new legal frameworks, mechanisms and instruments. Further to this, it can be argued that in the areas of cybersecurity there is evidence of actorness – in the sense that the EU has been able to speak and practice security with competence and authority – and, indeed, shape its identity as a cybersecurity actor. (Christou Citation2019, p. 294).

On the other hand, authors have also identified that European cybersecurity still suffers from institutional fragmentation (Deibert Citation2016), and that ambitious EU cybersecurity proposals have tended to meet with resistance from member states (Bendiek et al. Citation2017, p. 7). While some member states prefer to go further with EU cybersecurity cooperation, others prefer sub-regional cooperation (Carrapico and Barrinha Citation2017, p. 11). Moreover, as displayed by Liebetrau (Citation2019), the EU has faced difficulties when it comes to securitisation in the traditional Copenhagen School sense:

EU securitizing moves enacting objects and subjects of security traditionally associated with national security thus often work as an obstacle to successful implementation of EU extraordinary measures. On the contrary, the EU seem to be most successful in claiming and transforming security authority and European security governance through security policies and practices that are embedded within and not extricated from logics such as the Internal Market and economic integration. (Liebetrau Citation2019, p. 157)

Despite increasing scholarly interest, there are still considerable gaps in the understanding of the contents and specifics of the tension between EU cybersecurity ambition and member state contestation. This study aims to contribute to bridging this gap by exploring the relationship between the relative prevalence of security logics in the EU cybersecurity ambition and pronounced governance challenges/contestation.

A central argument of this study is that the current lack of understanding of the dynamics of risk vs. threat-based security logics in EU cybersecurity policy and practices leaves out an essential perspective to understand development, change and resistance in international cybersecurity cooperation. Common for the contributions focusing on the EU securitisation of the cybersecurity field, although insightful, has been the lack of analytical distinction between threat and risk-based security logics while studying securitisation processes. This is puzzling given that cybersecurity governance tends to be extensively influenced by aspects and approaches of risk (Dunn Cavelty Citation2008, pp. 139–140).

The parallel existence of risk and threat-based logics in governance as well as risk and threat-centred problems in practice is not unique for the cybersecurity field. Researchers have increasingly put efforts into understanding this dynamic and its consequences in other transboundary policy areas, such as, for example, climate change (Corry Citation2012, Estève Citation2021), energy security (Judge and Maltby Citation2017) and health security (Bengtsson, Borg, and Rhinard Citation2018). This turn is based on the acknowledgement that a refined analysis of the political processes surrounding transboundary and complex security issues may require an analytical approach which distinguishes between risk and threat-based logics to a larger extent than securitisation theory in a traditional sense. In general, as noted by Belzacq et al., empirical studies on energy and environment from the perspective of securitisation have shed light on the urgency of further exploring the relations between risk and securitisation (Balzacq and Dunn Cavelty Citation2016, p. 512).

While some efforts have been made to examine the link between problem conceptualisation and governance in the EU cybersecurity policies, including studies on the connection between its “security as resilience” approach and the development of the EU ecosystem for cybersecurity (Christou Citation2016), and the effects of Covid-19 on the ideational continuity connected to the EU cybersecurity policies and governance (Carrapico and Farrand Citation2020), there have been less attempts to understand governance challenges and member state contestation connected to EU cybersecurity ambition in the context of security logics.

Theoretical context: securitisation in the era of risks

The field of security studies has deepened and broadened substantially during later years. This evolution has followed modern world developments changing the basic assumptions of the traditional study of security, including globalisation the rise of new actors and a changed role of nation states in global affairs (Baylis et al. Citation2017). It also includes the arrival of transnational concerns on the global agenda (Mingst and Snyder Citation2017), increasing interdependence and the introduction of new risks and threats on the global arena (Müller 2013).

In the wake of these developments, students of security have increasingly found it challenging to exclude matters of risk and vulnerability from the study of security (traditionally more focused on threats) (Aradau, Lobo-Guerrero, and Van Munster Citation2008, Müller 2013, Chandler Citation2010, p. 436, Balzacq et al. Citation2016). As noted by Corry: “Increasingly, security practices are about prevention, probabilities, possible future scenarios and managing diffuse risks rather than about deterring foes or defending against identifiable and acute threats” (Corry Citation2012, p. 236). Combined with the trend to apply interdisciplinary theoretical and methodological approaches to study complex transnational problems, this has paved the way for an increased interest within security studies on the concept of risks, and how it relates to the concept of threats in a security context.

The scholarly contributions focusing on the broadening of security to include aspects of risk contain a broad spectrum of approaches, reflecting different ontological and theoretical assumptions and standpoints. From applications of the traditional notion of the “risk society” as understood by Beck (Citation1999) to the study of risks in relation to strategy (Rasmussen Citation2006), to conceptualisations of risk as a dispositif for governing social problems (Aradau and van Munster Citation2007).

This article focuses on the issue of risk specifically in relation to securitisation theory. Securitisation, as described by Buzan et al. (Citation1998), is at its core a more extreme form of politicisation. When an issue is securitised, it is presented as an existential threat to a referent object, which justifies actions outside the ordinary or normal political procedures (Buzan et al. Citation1998, p. 24). The process of securitisation involves one discursive and one non-discursive part. The first entails a speech act from the securitising actor aimed at achieving a shared understanding and collective acceptance for the proposed measures, and the second is the implementation of proposed measures. For a complete securitisation to happen, as argued by Emmers (Citation2010), the securitising actor must not only convince a relevant audience of the problem articulation and achieve acceptance for extraordinary action to address the existential threat, they must also adopt the proposed measures (Emmers Citation2010, p. 141).

While the perspective of securitisation has been widely popular and influential within security studies, the Copenhagen School has also been criticised for its lack of refinement in regards to different logics of security (Judge and Maltby Citation2017, p. 182), including the lack of acknowledgement of risks in relationship to threats in the securitisation process (Aradau et al. Citation2008, p. 149).

Rather than arguing for a more deliberate and refined inclusion and acknowledgement of risk in securitisation theory (see for example Trombetta Citation2008), this article builds on the notion that risk politics (riskification) should be analysed and understood as separate from threat politics (securitisation). This approach, as described by Olaf Corry, implies that risk politics involves its own dangers and advantages: “Though at times interwoven, making an issue a question of risk is not the same as a securitisation nor even necessarily a precursor to it” (Corry Citation2012, p. 236). From this perspective, “riskification” can be seen as a social process with similarities to the securitisation process, but concerned with risks in both the discursive phase (speech acts) and non-discursive phase (policy implementation and collective approval of proposed measures). A key difference here is that risk-security is essentially focused on the conditions of possibility for harm, as opposed to direct causes of harm (threat-security) (Corry Citation2012, p. 238). While the notion of riskification has also received critique, prominently on the basis that it is, like securitisation, is fixated on discourse (Petersen Citation2012, p. 710), its added value arguably lies in making possible the identification of a different mentality of governing in a process that without this perspective could be (mistakenly) labelled as securitisation. Thus, it maintains the integrity of the concept of securitisation while allowing for a more refined understanding of the politics surrounding danger.

Analytical framework: distinguishing between risk vs. threat-based security logics

In applying a discursive approach to security, this article broadly adopts the Copenhagen School’s notion that security is “spoken” into reality (Buzan et al. Citation1998, p. 24). Drawing upon the work of Corry (Citation2012), this article seeks to identify distinct logics of speech acts in terms of threat vs. risk. Where a threat-based security logic from this perspective is concerned with agency and intent of conflicting parties, external threats to referent object and policy prescriptions focused on defense against direct causes of harm (antagonists), a risk-based security logic is focused on systemic vulnerability and increasing resilience of referent object from a wide range of known but unspecified threats and risks (Corry Citation2012, p. 246, Bengtsson et al. Citation2018, p. 28). The theoretical framework is separated into two analytical categories of speech acts: problem emphasis combined with proposed response and policy prescriptions. A discourse indicating a threat-based cybersecurity logic is, for example, focused on identifiable and acute cyber threats (a threatening “other” or antagonist in cyber space). A discourse indicating a risk-based cybersecurity logic is focused on traits of long term, permanent and/or future danger to societies stemming from cyberspace, which may not be based on adversarial cyber threats. Rather than activating exceptional politics or militarisation against existential threats, the policy prescriptions connected to a risk-based security logic tend to focus on longer-term societal engineering and management of causes of harm without going into the realm of emergency or exceptionality (Corry Citation2012, p. 245).

Research design, data and methods

The study is divided into two analytical parts. Part 1 aims to identify the relative prevalence of risk vs. threat-based security logics in the EU cybersecurity approach over time. Part 2, which is more inductive, aims to explore areas of contestation and governance challenges accompanying the identified security logic development.

For the first part, the study uses a combination of content analysis and qualitative text analysis of key EU cybersecurity strategy documents, with the addition of interview data. The main units of analysis are the first and second EU cybersecurity strategies (published 2013 and 2020), combined with the security strategies of the EU (published in 2015 and 2020). Cybersecurity is a complex policy field containing a plethora of policy documents at the EU level, focusing on different aspects of the field. These central (cyber)security strategies have therefore deliberately been chosen as main units of analysis on the basis that they constitute the condensed EU approach towards the policy field of cybersecurity. Additionally, other cybersecurity policy material such as the European Commission recommendation on building a joint cyber unit (2021) and European Parliament briefing on the NIS2 have been consulted. NIS 2 is the updated and revised version of the Network and Information Security Directive, the first EU-wide legislation on cybersecurity (adopted in 2016). The NIS directive is aimed at enhancing cybersecurity across the EU through a focus on national capabilities, cross-border collaboration and national supervision of critical sectors.

For the second part, the study primarily uses interview data, triangulated with Council of the European Union documents outlining the Council’s position and approaches regarding the Commission proposals for two central cybersecurity legal documents. respectively: NIS2 (the revised NIS directive) and The Cybersecurity Act.

The research design of this study included two main steps. The first started with a content analysis of the four key strategy documents, using the software tool of NVivo. The tool analysed all strategy documents for the relative word frequency of certain words relative to the total count of words. Coded words were selected according to the theoretical framework as indicators of threat-based or risk-based security (see ). Each set of coded words contained two words connected to problem emphasis and three words connected to policy prescriptions. The content analysis tool accounts for variations of the coded words in the documents (for example, plural or singular) in the analysis. While the author acknowledges that the results of this analysis cannot be a precise indicator for the prevalence of risk or threat-based security logics in the documents (not least because of the difficulty of identifying a word strictly as an indicator of a risk or threat-based security logic), the point of this part of the analysis was to provide a trend overview of the development of words that might be indicative of a change in relative presence of security logics in the overall problem emphasis and policy prescriptions (speech acts). The content analysis was followed by a qualitative text analysis of the key strategy documents guided by the operationalisation of this study (). The second step involved 13 interviews with elites (senior EU cybersecurity experts). Of these, 11 interviews were in-depth (about 1 h long each) conducted over zoom and 2 were shorter interviews conducted through email correspondence. All interviews were conducted during 2021 (except for one which was conducted in 2022).

Table 1. Operationalisation of risk vs. threat-based security logics. Adopted from Corry (Citation2012, pp. 248–249) in terms of categories and key indicators for risk and threat-based security logics, respectively. Coded words have been added by the author for the content analysis part of the study.

Interviewees included senior strategic or operational cybersecurity experts/practitioners working within, or previously working within, national cybersecurity agencies (including CERTS/national cybersecurity centres) of four EU member states/EEA countries, or EU initiatives connected to NIS/CIP, cybercrime or cyber defence, including ENISA (European Agency for Information Security) and the EC3 (European Cybercrime Centre). The interviewees were allowed to remain anonymous in the study. Some of the interviews were conducted in Swedish and translated by the author (a native speaker). The interviews were conducted using a semi-structured approach, which allowed the interviews to unfold in a rather flexible fashion around the main questions. The main questions posed to the interviewees concerned their view on (1) The development of the EU cybersecurity approach in terms of problem emphasis and policy prescriptions between 2013 and 2020 (linked to the EU cybersecurity strategies). (2) Governance challenges connected to this development. (3) Prospects of policy implementation of proposed policy prescriptions.

Analysis

Part 1: development of risk vs. threat-based security logics in the EU cybersecurity approach

Problem emphasis

As defined in the operationalisation, a risk-based security logic is indicated by a problem emphasis with a strategic focus on systemic characteristics and vulnerability of societies, with an emphasis on the need to govern the constitutive and inherent causes of harm. A threat-based security logic is indicated by a problem emphasis that has a strategic focus on direct threats, with an emphasis on the need to defend against external causes of harm.

When comparing the strategies, several key differences in relation to the above can be detected. The 2013 cybersecurity strategy reflects a focus on governing the inherent causes of harm (dependence and vulnerability) rather than explicit external threats. A key indicator for this is the references to safety alongside security in the first EU cybersecurity strategy, which states that it: “... sets out the actions required based on strong and effective protection and promotion of citizens’ rights to make the EU's online environment the safest in the world” (European Commission Citation2013, p. 2). In contrast, the 2020 strategy states that it “sets out how the EU will shield its people, businesses and institutions from cyber threats, and how it will advance international cooperation and lead in securing a global and open Internet” (European Commission Citation2020a, p. 4). This is indicative of a more threat-based security logic, where the focus on safety (primarily connected to inherent dangers) has been replaced by a more strict focus on security (primarily connected to external threats).

Another contrast between the cybersecurity strategies can be found in their inclusiveness/exclusiveness of causes to cyber incidents as formulated in the introduction section of the strategies. The introduction section of the 2013 strategy states that “threats can have different origins – including criminal, politically motivated, terrorist or state-sponsored attacks as well as natural disasters and unintentional mistakes” (European Commission Citation2013, p. 3). In comparison, the 2020 strategy’s introduction section refers exclusively to cyber-attacks linked to malicious targeting as causes to cyber incidents. This reflects a move from an “all-hazards approach” where a wide variety of antagonistic and non-antagonistic threats and risks are emphasised, to an approach more associated with a threat-based logic – with a primary focus on the need to defend against antagonistic cyber threats. “The EU started off with an all-hazards approach in the cybersecurity field, recognising that downtime in digital services might well be due to a mistake or something that is not linked to an actual attack” (Interviewee 9), one interviewee explained.

When asking the interviewees about, in their view, major differences in the EU cybersecurity approach over time, a majority of the interviewees highlighted a shift towards a more antagonist focused problem formulation (Interviewee 1, Interviewee 2, Interviewee 3, Interviewee 4, Interviewee 5, Interviewee 6, Interviewee 7, Interviewee 8, Interviewee 9 and Interviewee 12). “On the supranational level, I think the biggest difference over time is that the EU has moved from an approach focusing on ensuring availability and reliability towards an approach more focused on actor-driven threats and active protection” (Interviewee 5). “It is my understanding that the EU has ‘stepped forward’ as a cybersecurity actor during the last years, and that the current focus is quite threat-oriented” (Interviewee 1).

When comparing the 2015 and 2020 EU security strategies, an overall increased focus on cybersecurity can be noted in the latter. In terms of cybersecurity, the primary focus in the first strategy is placed on cybercrime as a threat to citizen’s fundamental rights and to the economy (European Commission Citation2015, p. 13). In the 2020 security strategy, cybersecurity in a broader sense is emphasised as a strategic priority for the Union, stating that

The number of cyber-attacks continues to rise. These attacks are more sophisticated than ever, come from a wide range of sources inside and outside the EU, and target areas of maximum vulnerability. State or state-backed actors are frequently involved, targeting key digital infrastructures like major Cloud providers. (European Commission Citation2020b, pp. 7–8)

Policy prescriptions

When it comes to policy prescriptions, a risk-based security logic is indicated by a strategic focus on management and mitigation of risk, a plan of action to increase governance and resilience of referent object, and a focus on preventive measures. The characterisation of a threat-based security logic in policy prescriptions is, in contrast, a strategic focus on defending against identifiable and acute threats external to the referent object.

When comparing the first and second EU cybersecurity strategies from a policy prescription perspective, several key changes can be detected. A foundational one is a shift from cybersecurity to be an area to “step up within” in the 2013 strategy to cybersecurity being an integral (and prioritised) part of European security in general. This has also included increasingly high ambitions in the field. As one interviewee explained:

The EU has developed higher and higher ambitions in the field of cybersecurity. This is indicated by the reinforced mandate of ENISA under “The cybersecurity Act”. The proposal for the renewed NIS-directive (NIS 2) is also far more ambitious than the first NIS-directive. (Interviewee 2)

Beyond a generally increased ambition, two major themes of policy prescriptions stand out in the 2020 strategy compared to the 2013 strategy. The first is the increase in policy prescriptions directed at EU involvement in responsive and technical/operational cybersecurity and cyber crisis management activities. This includes, for example, the proposal of creating a European Cyber Shield to enhance the technical/operational defence against cyber-attacks and build a network of Security Operations Centres across the EU (European Commission Citation2020a, p. 6). It also includes the proposal of creating a Joint Cyber Unit. This structure would provide the opportunity for technical and operational capabilities (primarily experts and equipment) ready to be deployed to member state in case of need (European Commission Citation2021). According to the Commission recommendation of building the Joint Cyber Unit, it would also be a hub of information sharing:

The physical platform should be combined with a virtual platform composed of collaboration and secure information sharing tools. Those tools will leverage the wealth of information gathered through the European Cyber-Shield, including Security Operation Centres (“SOCs”) and Information Sharing and Analysis Centres (“ISACs”). (European Commission Citation2021)

Interviewees for this study also commented on this development: “It seems that the EU is heading towards developing its reactive abilities in addition to the preventive measures that exists” (Interviewee 3).

The first EU cybersecurity strategy had a rather preventive focus, the whole field was quite immature. From that point, a lot has happened, and the EU has developed more reactive and operational abilities, as well as a new focus on issues like democracy and space development. (Interviewee 4)

The second “new” theme of policy prescriptions in the 2020 strategy compared to the 2013 strategy consists of measures aimed at enhancing EU capacities and capabilities in terms of cyber defence, diplomacy and deterrence. According to the new strategy, malicious cyber activities should be tackled by a joint EU diplomatic response, using the full range of measures available at the EU level (European Commission Citation2020b, p. 16). To support this ambition, the strategy points to the “cyber diplomacy toolbox”, a collection of legal and operational measures aimed at preventing, discouraging, deterring and responding to malicious cyber activities. There is also an ambition to enhance intelligence cooperation between member states concerning cyber threats through the establishment of a member state’s EU cyber intelligence working group residing within the EU Intelligence and Situation Centre (INTCEN) to advance strategic intelligence cooperation on cyber threats and activities. The group is to work with existing structures including, where necessary, those covering the wider threat of hybrid and foreign interference (European Commission Citation2020a:, p. 17).

Additionally, the 2020 cybersecurity strategy articulates an ambition for the EU to further define its cyber deterrence posture. According to the strategy, the deterrence posture should outline how the EU and member states could improve their ability to attribute malicious cyber activities and utilise various tools (including political, diplomatic, economic, legal and strategic communication) in response to them (European Commission Citation2020a, p. 17).

This focus can also be noted in the 2020 security strategy, stating that the EU’s cybersecurity capability building now builds on an approach proposed in 2017 with resilience-building, rapid response and effective deterrence at its core (European Commission Citation2020b, p. 8). Compared to the 2015 security strategy’s focus on combatting cybercrime, the 2020 strategy reflects a shift in proposed measures towards a more operational and defence-oriented focus, for example, through the creation of a Joint Cyber Unit. Indeed, the EU reaffirmed already in 2017 that cybersecurity is increasingly becoming part of its external policy, including its emerging defence policy (European Court of Auditors Citation2019, pp. 12–13). In addition to developing operational capabilities, the recommendation on the creation of the Joint Cyber Unit includes the ambition to acquire key cyber defence capabilities which would reinforce national cyber defence preparedness (European Commission Citation2021).

Moreover, the 2020 strategy introduce a new focus compared to the 2015 strategy on the need for a joint EU diplomatic response to malicious cyber activities, as well as the need for building and maintaining robust international partnerships to prevent, deter and respond to cyber-attacks (European Commission Citation2020b, p. 9).

These key new themes of policy prescriptions in both 2020 strategies indicate a shift towards an increased strategic focus associated with a threat-based security logic, including a new plan of action to defend against threats external to the referent object (the EU and its member states). However, both strategies also include measures more indicative of a risk-based security logic, including a strategic focus on decreasing vulnerability based on digital societal dependence and the need to prevent and build resilience from a wide range of threats and risks. For example, the proposal for the new NIS directive is explicitly aimed at enhancing cyber resilience (European Commission Citation2020a, p. 5), and there are various suggestions for new or enhanced measures focused on reducing societal and individual vulnerability from cyber risks and threats in the 2020 strategy. This suggests that rather than replacing the risk-based security logic that was predominant in the problem emphasis and policy prescriptions of the 2013 cybersecurity strategy, a threat-based security logic has been added to the EU cybersecurity approach. That said, interviewees also expressed a concern that an increased focus on antagonist attacks as causes of major cyber incidents or attacks may (and perhaps even have) deflected attention and resources from managing other common causes of cyber incidents, including failures and mistakes (Interviewee 2, Interviewee 6, Interviewee 12).

Content analysis

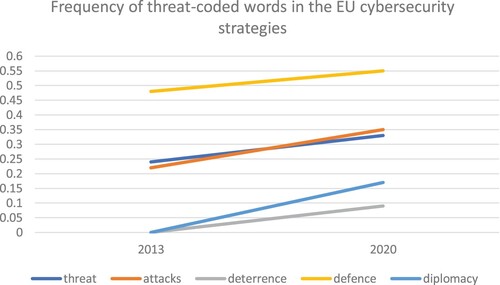

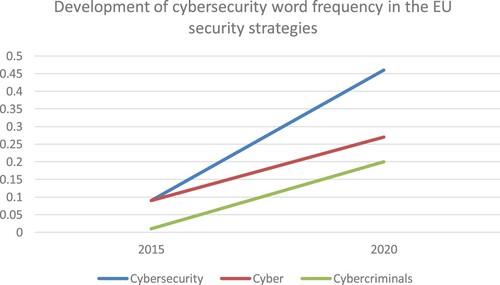

displays an overall increase in cybersecurity word frequency between the 2015 document (the European Agenda on Security) and the 2020 document (the EU Security Union Strategy). While this increase does not tell us specifics on the security logics involved in these articulations, it indicates that cybersecurity has been increasingly integrated and has become an increasingly important part of the EU’s overall security approach.

Figure 1. Weighted Percentage (%) – frequency of the word relative to the total words counted in the EU security strategies, respectively (2015 and 2020).

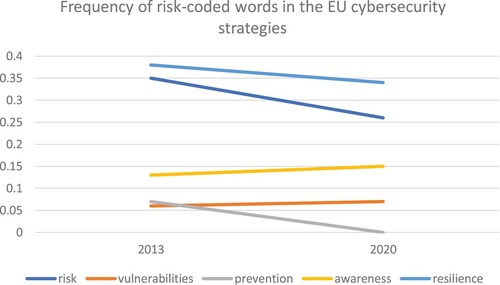

indicates a slight decrease of risk-coded words (compiled) between the documents. While the words prevention and risk decrease most between the documents, the words vulnerabilities and awareness saw a very slight increase. Notably, the word prevention moved from a low frequency in the 2013 document to being unreferred to in the 2020 document. In general, however, no substantial trend development between the strategies in terms of the relative frequency of risk-coded words could be detected.

Figure 2. Words coded as indicators of a risk-based security logic. Weighted Percentage (%) – frequency of the word relative to the total words counted in the EU cybersecurity strategies, respectively (2013 & 2020).

displays a slight increase of all analysed threat-coded words between the documents. The word defence tops the chart, which is also the most frequent word of all analysed words in total (risk-coded words included). Notably, the words deterrence and diplomacy were introduced for the first time in the 2020 strategy, from being unreferred to in the 2013 strategy. The results from the charts in total indicate a trend towards an increase in the frequency of words coded as indicators for a threat-based security logic connected to the documents, while the words coded as indicators for a risk-based security logic indicate a trend towards a very slight decrease. Parallel, as displayed in , cybersecurity has been increasingly integrated into the overall discursive security approach of the EU.

Part 2: governance challenges and contestation

Moving into the second part of the study, focus is now shifting to exploring areas of contestation and governance challenges. Before moving into the identified areas of contestation, it is important to acknowledge that the adoption of the EU Cybersecurity Act (in 2019) and the expected adoption of the NIS 2 (in 2022) is indicative of an extent of member states’ acceptance of a more threat-based cybersecurity approach (through the broad adoption of the policy prescriptions set out in the new EU cybersecurity strategy). Nevertheless, interview data and analysis of Council positions connected the Commission’s suggestions for these legal documents also point to specific areas of contestation and governance challenges accompanying the identified security logic development.

The first is centred on the increased EU involvement in the operational cybersecurity layer (which constitutes the “first line of defence” to cyber threats) and member states joint cyber crisis management efforts. As one interviewee explained:

There is an ongoing ambition to try to increase the pan-EU capacity to manage large-scale cyber crises, for example through the new initiative CyCLONe (Cyber Crises Liaison Organisation Network). However, there has been some resistance both from the strategic level actors who questions the creation of specific cyber crises structures (instead of just incorporating it in generic crisis management structures) and the technical/operational level actors, who are reluctant to have more EU involvement and structures. (Interviewee 9)

Another issue of contestation is centered on information sharing. In the negotiations of the proposed “EU Cybersecurity Act”-regulation (which outlines an extension of the mandate of ENISA and a framework for the establishment of European cybersecurity certification schemes) member states wished to clarify and emphasise the voluntary nature of information sharing and sharing of technical solutions (Council of the European Union Citation2018, p. 15). Interviewees also emphasised that cybersecurity information sharing often requires mutual trust (because of its sensitive nature), which causes member states to use other venues than the EU ones to do more substantial information sharing, often in regional settings with trusted partners (Interviewee 6 and Interviewee 7). As one interviewee explained:

Reporting in general is essential for situational awareness, but maybe is not as efficient now because of the lack of maturity in some cooperation formats. In some circles (csirts/computer security incident response teams), the trust is high among the members, and they share a fairly great amount of information, but more informally. (Interviewee 13)

Data also point to some pushback from member states in terms of the extent of scope in the new EU cybersecurity initiatives. In response to the suggested extension of mandate and tasks of ENISA in the Cybersecurity Act, member states emphasised the role of the agency as supporting operational cooperation on requests of member states rather than it being the performer of operational tasks (European Council Citation2018, p. 15). One of the main concerns expressed by member states in connection to the NIS 2 proposal was the significant increase in the number of entities covered by the directive. As a result, member states wished to further clarify that the directive does not apply to entities that mainly carry out activities in the areas of defence, national security public security or law enforcement or to activities concerning national security or defence (the exclusion clause) (Council of the European Union Citation2021, p. 6). Several interviewees pointed out that there is a difficult balance between supranational initiatives to meet shared cybersecurity challenges and member states’ sovereignty in security matters (Interviewee 6 and Interviewee 9). “A major cyber crisis will always be about national security and involve actors that work with national security. It does not go well with the idea of an EU taskforce including staff from different member states”, one interviewee argued (Interviewee 3).

Some interviewees further highlighted that member state acceptance towards increasing EU involvement in cybersecurity issues can vary substantially across the union depending on the cybersecurity maturity of member states. As one interviewee mentioned: “In general, the smaller or less cyber-mature member states are more positive towards increased EU cybersecurity initiatives and involvement than the more powerful and cyber-mature member states” (Interviewee 9). One interviewee from a national CERT highlighted the new “CyCLONe” as an example of an initiative that impacts differently on different member states depending on their cyber-maturity.

This might work well for the member states that do not have this kind of function in place, but for the member states that already have something similar established, this initiative will just add more work to an already intense workload on the operational responders during a large-scale incident. (Interviewee 3)

Discussion

For the EU to move towards a more threat-based cybersecurity logic, including securitising moves enacting to a larger extent than before objects and subjects of security traditionally associated with national security, is to some extent surprising – even considering that most of the EU cybersecurity initiatives (including those reflecting a more threat-based security logic) are still voluntary. Earlier research on the EU as a cybersecurity actor has identified that it faces structural and institutional barriers when it comes to securitisation in a traditional Copenhagen School sense (Liebetrau Citation2019, p. 157). As indicated by the data for this study, the shift towards a more threat-based cybersecurity approach has been accompanied by several areas of member state contestation, including the extent of EU involvement in operational cybersecurity activities and cyber crisis management efforts, as well as the issues of cybersecurity information sharing and incident reporting duties. Moreover, the EU still faces considerable governance challenges such as the disparity of member state cybersecurity maturity and the variety of cybersecurity institutional arrangements across the union, as well as differences across the union in terms of the desired extent of EU involvement in member state cybersecurity activities. Additionally, the EU cybersecurity cooperation is still on a rather nascent level. As described by the 2020 EU cybersecurity strategy, there is currently only limited mutual operational assistance between member states, and the EU still lacks collective situational awareness of cyber threats as a result of a lack of information collection and information sharing from national authorities (European Commission 2020, pp. 3–4).

These findings call for a brief discussion on the potential driving forces behind the identified development. Such an attempt inevitably draws attention to contextual factors and to the development of the EU as a security actor beyond cybersecurity.

During the last decades, the global security environment has transformed, and with it the EU’s security architecture and ambitions. As argued by Shepherd (Citation2021), this has included a development towards an integrated approach in response to transboundary threats, seeking to transcend the traditional dichotomy of internal security and external defence. Despite struggles to adjust its institutional architecture to transcend the internal–external divide, this has included externalisation of internal security policies within several issue areas, including counterterrorism, organised crime and immigration (Shepherd Citation2021, p. 16). From this perspective, then, the move towards a more threat-based cybersecurity approach and ambition could be understood as an externalisation process of the issue area of EU cybersecurity, following the EU’s continuous efforts to convince member states of its added value as a security actor managing modern transboundary threats and security problems.

This development must also be seen in the context of the deteriorating global security landscape in cyber space (Turell et al. Citation2020), and the experience of increasing instances of cyber crises and large-scale cyber incidents (Backman Citation2020). Indeed, several interviewees argued that the current geopolitical development and deteriorating international cybersecurity environment in combination with the experience of cyber crises (including, for instance, the ones stemming from the WannaCry and NotPetya-attacks) have contributed to the EU moving towards increasing cybersecurity initiatives and a more threat-focused cybersecurity approach (Interviewee 5, Interviewee 8 and Interviewee 6).

Another contextual aspect that might have had an impact is the development of cybersecurity conceptualisations on the national level. An increasing number of states are now developing more offensive cyber stances in their national cybersecurity approaches, including the use of offensive cyber tools. An example of this can be found in the U.S “defending forward”-approach presented in 2018, which included a shift towards a more active, and external threat-oriented cyber strategy (Department of Defense Citation2018). Such a shift in cybersecurity strategy and conceptualisation on the national level will unlikely has no impact on the conceptualisation of cybersecurity on the international level, including the EU. This development can also hardly be analytically removed from the securitisation and militarisation of cyber space more broadly, in which the presence of cyber anxiety and fear (Dunn Cavelty Citation2008), a booming cybersecurity and cyber defense industry (Singer and Friedman Citation2014) and the idea that offensive cyber tools offer a cheap but powerful advantage to states have animated global discourse (Valeriano et al. Citation2018, Burton and Christou Citation2022) and contributed to threat-inflation in the international cybersecurity landscape over time.

Conclusion

The results of this study point to a development towards an increasingly threat-based security logic in addition to a still existing risk-based security logic in EU cybersecurity problem formulations and policy prescriptions over time. The identified development highlights securitising moves enacting to a larger extent than before objects and subjects of security traditionally associated with national security (however, primarily on a voluntary basis). While there are indicators of an extent of member state acceptance of this development, the study could also identify specific areas of member state contestation and governance challenges accompanying it. The results were discussed in context of the securitisation of cyberspace globally and the development of the EU as a security actor in relation to transboundary issue areas.

The results of the study suggest that processes of securitisation and riskification do not need to follow each other in a linear manner. Rather, as displayed in the study, they can co-exist and run parallel. Distinguishing between threat and risk-based logics in the study of the EU political processes connected to the governance of dangers can shed new light on the EU as a security actor and contribute to explaining its governance challenges, including member state contestation. This approach may be particularly useful to understand the politics of complex, multilayered and transboundary policy issues, such as cybersecurity.

List of interviewees

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aradau, C., Lobo-Guerrero, L., and Van Munster, R., 2008. Security, technologies of risk, and the political: guest editors’ introduction. Security dialogue., 39 (2-3), 147–154.

- Aradau, C., and van Munster, R., 2007. Governing terrorism through risk: taking precautions, (un)knowing the future. European journal of international relations, 13 (1), 89–115.

- Adamson, L., and Homburger, Z., 2019. Let them roar: small states as cyber norm entrepreneurs. European foreign affairs review, 24 (2), 217–234.

- Backman, S., 2020. Conceptualizing cyber crises. Journal of contingencies and crisis management, 29, 429–438.

- Balzacq, T., Léonard, S., and Ruzicka, J., 2016. ‘Securitization’ revisited: theory and cases. International relations, 30 (4), 494–531.

- Beck, U., 1999. World risk society. Polity. Cambridge: Polity Press, 184.

- Bendiek, A., Bossong, R., and Schultze, M., 2017. The EU's revised cybersecurity strategy: half-hearted progress on far-reaching challenges. Berlin: Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik (SWP) Deutsches Institut für Internationale Politik und Sicherheit.

- Baylis, J., Smith, S., and Owens, P. eds. 2017. The Globalization of World Politics: An Introduction to International Relations. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bengtsson, L., Borg, S., and Rhinard, M., 2018. European security and early warning systems: from risks to threats in the European Union’s health security sector. European security, 27 (1), 20–40.

- Brown, I., and Marsden, C., 2013. Regulating code: good governance and better regulation in the information Age. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

- Burton, J., and Christou, G., 2021. Bridging the gap between cyberwar and cyberpeace. International affairs, 97 (6), 1727–1747.

- Buzan, B., Wæver, O., and Wilde, J.D., 1998. Security: a new framework for analysis. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner.

- Carrapico, H., and Barrinha, A., 2017. The EU as a coherent (cyber)security actor?. JCMS: Journal of common market studies, 55, 1254–1272. doi:10.1111/jcms.12575.

- Carrapico, H., and Farrand, B., 2020. Discursive continuity and change in the time of COVID-19: the case of EU cybersecurity policy. Journal of European integration, 42, 8.

- Chandler, D., 2010. Review article: risk and the biopolitics of global insecurity. Conflict, security & development, 10 (2), 287–297.

- Christou, G., 2019. The collective securitisation of cyberspace in the European Union. West European politics, 42 (2), 278–301.

- Christou, G., 2016. Cyber security in the European Union: resilience and adaptability in governance policy. Houndmills. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Claessen, E., 2020. Reshaping the internet – the impact of the securitisation of internet infrastructure on approaches to internet governance: the case of Russia and the EU. Journal of cyber policy, 5 (1), 140–157.

- Corry, O., 2012. Securitisation and ‘riskification’: second-order security and the politics of climate change. Millennium: Journal of international studies, 40 (2), 235–258.

- Council of the European Union. 2018. Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on ENISA, the “EU Cybersecurity Agency”, and repealing Regulation (EU) 526/2013, and on information and communication technology cybersecurity certification (“Cybersecurity Act”) - General approach.

- Council of the European Union. 2021. Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on measures for a high common level of cybersecurity across the Union, repealing Directive 2016/1148- General Approach.

- Department of Defence, United States of America. 2018. The 2018 Department of Defense Cyber Strategy.

- Deibert, R., 2016. Cyber-security. In: M. Dunn Cavelty, and T. Balzacq, eds. Routledge handbook of security studies. (2nd ed.). Abingdon: Routledge, 172–182.

- Dunn Cavelty, M., 2018. Europe's cyber-power. European politics and society, 19 (3), 304–320.

- Dunn Cavelty, M., 2008. Cyber-security and threat politics: US efforts to secure the information age. London & New York: Routledge.

- Emmers, R., 2010. Securitization. In: A Collins, ed. Contemporary security studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 136–151.

- Estève, A., 2021. Preparing the French military to a warming world: climatization through riskification. International politics, 58, 600–618.

- European Commission. 2013. Cybersecurity strategy of the European Union: an open, safe and secure cyberspace.

- European Commission. 2015. The European agenda on security.

- European Commission. 2020a. The EU's cybersecurity strategy for the digital decade.

- European Commission. 2020b. The EU security union strategy.

- European Commission. 2021. Commission Recommendation (EU) 2021/1086 of 23 June 2021 on building a Joint Cyber Unit.

- European Court of Auditors. 2019. Review No 02/2019: challenges to effective EU cybersecurity policy (Briefing Paper).

- Iasiello, E., 2016. What happens if cyber norms are agreed to? Georgetown Journal of international affairs, 17 (3), 30–37.

- Judge, A., and Maltby, T., 2017. European energy union? Caught between securitisation and ‘riskification’. European journal of international security, 2 (2), 179–202.

- Liebetrau, T., 2019. EU cybersecurity governance: redefining the role of the internal market. Dissertation (PhD). University of Copenhagen, Department of Political Science.

- Mueller, M., 2010. Networks and states: the global politics of Internet governance. Cambridge: MIT press.

- Mingst, K. and Snyder, J., (2017). Essential readings in world politics (6th ed.). New York: Norton.

- Pawlak, P., 2019. The EU’s role in shaping the cyber regime complex. European foreign affairs review, 24 (2), 167–186.

- Pawlak, P., and Missiroli, A., 2019. Introduction: trends, patterns, and challenges for international cooperation in cyberspace. European foreign affairs review, 24 (2), 125–134.

- Petersen, K.L., 2012. Risk analysis – a field within security studies? European journal of international relations, 18 (4), 693–717.

- Radu, R., Chenou, J., and Weber (red.), R.H., 2014. The evolution of global Internet governance: principles and policies in the making. Berlin: Springer.

- Rasmussen, M., 2006. The risk society at war: terror, technology and strategy in the twenty-first century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Raymond, M., 2016. Managing decentralized cyber governance: the responsibility to troubleshoot. Strategic studies quarterly, 10 (4), 123–149.

- Scholte, J., 2017. Polycentrism and democracy in internet governance. In: U Kohl, ed. The net and the nation state: multidisciplinary perspectives on Internet governance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 165–184.

- Shepherd, A.J.K., 2021. The EU security continuum: blurring internal and external security. London: Routledge.

- Singer, P.W., and Friedman, A., 2014. Cybersecurity and cyberwar: what everyone needs to know. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Trombetta, M., 2008. Environmental security and climate change: analysing the discourse. Cambridge review of international affairs, 21, 4.

- Turell, J., Su, F., and Boulanin, V., 2020. Cyber-incident management: identifying and dealing with the risk of escalation. Stockholm: SIPRI.

- Valeriano, B., Jensen, B.M., and Maness, R.C., 2018. Cyber strategy: the evolving character of power and coercion. New York: Oxford University Press.