ABSTRACT

This article evaluates the presence of framing mechanisms in Dutch media reporting on the Second Karabakh war. The paper is led by the following questions: To what extent, and why, does the reporting of the Dutch press favour/undermine certain actors in the conflict? What kind of framing patterns are involved in generating such partiality? And did the frames change over the course of the war? In order to evaluate the presence of framing mechanisms in Dutch media reporting on the second Karabakh war, this research conducted a qualitative data analysis of 188 articles on the topic in nine major national Dutch news media. The paper finds that Dutch newspapers created a rather stereotypical, simplified picture of the Second Karabakh war. There are instances where the reporting gave the impression of a possible bias or overemphasis on certain dimensions.

Introduction

Media and conflict have often been studied in relation to one another. Journalists can shape the way we see conflicts and crises, by constructing, framing and maintaining the realities of conflicts (Wahl-Jorgensen and Hanitzsch Citation2009). For instance, news frames can make the stories of conflicting parties more salient or silent in a communicating text.

One of the recent conflicts that has received significant international media attention is the 44-day war between Armenia and Azerbaijan over Nagorno-Karabakh and surrounding regions, which began on 27 September 2020. The war ended on 9 November 2020, when the Presidents of Azerbaijan and Russia and the Prime Minister of Armenia signed a trilateral agreement. The war took the lives of both Armenian and Azerbaijani civilians; as well as around 4000 Armenian soldiers and 3000 soldiers on the Azerbaijani side (TASS Citation2021; Amnesty International Citation2021).

The amount of media attention for the war in Dutch news was quite unusual. Armenia and Azerbaijan had already tested their militaries before, with strong clashes in 2008, 2014, 2016, and July 2020. Yet, in those cases, the conflict had received little attention in the Netherlands. One could argue that until September 2020, the conflict had remained underreported in Dutch media. This changed in the Autumn of 2020 when a significant number of articles were published on the situation in the region. Through this reporting, journalists of Dutch newspapers aimed to interpret and explain what is a very complex conflict with contested causes and history, for their audiences. This research found, however, that the studied media did not present a diversity of views and opinions while reporting on the Second Karabakh war. Moreover, there were instances where the reporting gave the impression of a possible bias or overemphasis on certain dimensions.

Dutch news media are generally considered to be trustworthy and unbiased by the Dutch public. The perception of national media offering “a diversity of views and opinions” is highest in the Netherlands among all the EU member states, namely according to 86% of respondents of the 2019 Eurobarometer on media (Publications Office of the European Union Citation2019, p. 40, 80). Similarly, a majority of Dutch respondents consider national media to provide “trustworthy information”, namely, 84%, with only Finland scoring higher with 86% (Publications Office of the European Union Citation2019). However, literature on Dutch media reporting on conflicts has found that there often does tend to be a bias (see e.g. Obermann & Dijkink Citation2008, Ruigrok Citation2008, Fengler et al. Citation2020).

This has led us to ask whether or not this was also the case for Dutch media reporting on the Second Karabakh War of 2020. Generally, not much has been published on Dutch media and conflict, in contrast to studies on Anglo-Saxon media coverage of conflicts (Van der Hoeven & Kester Citation2020, p. 2). Furthermore, there have been very few (Geybullayeva Citation2012, Goltz Citation2012, Atanesyan Citation2020) scholarly assessments of the media coverage of the N-K war thus far. Beyond the empirical contribution, this case study can also help us to gain further insight into conflict reporting in countries beyond a nation's immediate involvement or interest, making the chances of a bias less likely.

This paper is led by the following questions: to what extent, and why, does the reporting of the Dutch press favour/undermine certain actors in the conflict? What kind of framing patterns are involved in generating such partiality? Did these newspapers rely on information from the Armenian or Azerbaijani governments? And did the frames change over the course of the war? The paper builds on a detailed content and framing analysis of all articles on the conflict in nine major Dutch news outlets published for the duration of the conflict.

The article is divided into six more parts. The following section briefly provides background information on the Karabakh conflict. The subsequent part introduces the conceptual framework on which the analysis will be based. The third section sets out the chosen methodology. The fourth and main section of the article discusses the results of the newspaper analysis. The conclusion presents the article’'s findings and also identifies its limitations; and in the final section, it briefly reflects on further steps and aspects for consideration.Footnote1

Context of the conflict

This paper will not go into the historical details of the Karabakh conflict itself, as there are already a large number of works in existence that comprehensively address the historical details from different perspectives (e.g. Abasov and Khachatrian Citation2006, Abushov Citation2010, Geukjian Citation2012, De Waal Citation2013, Broers Citation2019, Gasparyan Citation2019, Makili-Aliyev Citation2019, Guliyev and Gawrich Citation2021). This paper will, however, briefly address the background to the Second Karabakh war which erupted in September 2020, as this context is likely to have had an effect on the way national as well as international media have reported on the war.

The Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh (N-K) and seven surrounding districts, which dates back to 1988 in its modern form, has been one of the most complicated and longest-running disputes in wider Europe. It involves an array of political, economic, legal, social and historical factors. “In May of 1994, the first Karabakh war between Azerbaijan and Armenia was ended by the Bishkek Protocol, which was signed by both countries under the supervision of Russia” (Bayramov Citation2016, p. 117). Between 1991 and 1994, Armenian forces occupied Nagorno-Karabakh as well as seven surrounding regions (Lachin, Kelbajar, Agdam, Jabrayil, Fuzuli, Qubatly and Zangelan) (Rossi Citation2017). This was condemned by several United Nations Resolutions 822, 853, 874 and 884, which mentioned the deterioration of the relations between Armenia and Azerbaijan and called on all occupying forces to release the regions. The conflict produced an economic, humanitarian and political catastrophe for both countries. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR Citation2009), at the time of the ceasefire in 1994, Azerbaijan hosted an estimated 250,000 Azerbaijani refugees from Armenia and more than 600,000 internally displaced persons (IDP). According to the Armenian government, there are more than 360,000 Armenian refugees as a result of the first Karabakh war (as cited by International Crisis Group Citation2009, p.1).

Mediation over a longer-term solution commenced in 1992, led by the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) Minsk Group. These mediation efforts are, however, considered to have been futile. On the one hand, the OSCE Minsk Group proved itself an inefficient mediator (Rossi Citation2017) among others caused by the fact that the Azerbaijani government considered some of the Co-Chairs to be biased in favour of Armenia (Bölükbaşı Citation2011). Since the signing of the Bishkek-Protocol, the hostility between the two countries has risen significantly. The Azerbaijani government made large investments into its military, using energy revenues and enhanced its (political, economic and military) relations with Turkey (Altstadt Citation2017), while the Armenian government has received security guarantees and military support from Russia (De Waal Citation2013). As a result, violent clashes between the two armies occurred at several points in time. Despite the scale and cost of these periodical clashes, the international community turned a blind eye to the conflict resolution process, with both the West and Russia having taken a minimalist approach.

Therefore, when the Second Karabakh war erupted between Armenia and Azerbaijan on 27 September 2020, this did not come as a surprise to observers familiar with the developments in recent years. Azerbaijan liberated the seven regions surrounding N-K, as well as a substantial part of N-K itself, including the strategically-located and hugely symbolic city of Shusha (Shushi in Armenian sources) (De Waal Citation2021). The trilateral agreement that ended the war on 9 November constitutes more than a mere ceasefire but is much less than an actual peace agreement (Broers Citation2020). In the aftermath, there still is uncertainty about the long-term prospects for the part of N-K that is still under Armenian control, about the role and presence of Russian peacekeepers, and the future of relations between Armenia and Azerbaijan. Additionally, the near absence of the United States (US) and European Union (EU) during and after the war strengthened the Russian power position in the region further, and confirmed Turkey's role as a regional security actor. Euro-Atlantic neglect and passivity throughout the war are reflected by the deal's sidelining of France, the US, the Minsk Group, and OSCE. All have lost immeasurable standing during the conflict (Broers Citation2020). Since then, the Minsk Group's prospects have looked ever more uncertain.

Conceptual framework

Media coverage of conflicts has been studied extensively, and there is vast literature on the topic. Although significant research has been done on the partial reporting of Anglo-Saxon war journalists, Dutch newspapers’ war reporting has received limited academic attention. By using the journalism of attachment concept, Ruigrok (Citation2006, Citation2008) illustrated that Dutch media played an important role in creating a rather stereotypical, simplified picture of the Bosnian conflict. My conceptual framework is inspired by the works of Bell (Citation1995), Ruigrok et al. (Citation2005), Ruigrok (Citation2008), van Oppen (Citation2009). In light of this, the journalism of attachment concept will be the main lens through which the paper will analyse the Dutch media reporting on the Second Karabakh conflict. Adding to the war reporting and conflict literature, I pursue two objectives: First, to show whether the reporting of the Dutch press favours/undermines certain actors in the Second Karabakh conflict. What kind of framing patterns are involved in generating such partiality? In other words, I show whether the Dutch newspapers followed similar journalism of attachment patterns in the Karabakh conflict. Secondly, I argue that the behaviour of partial reporting is not only restricted to Anglo-Saxon war journalists, but it can also be seen in different European/Western newspapers.

Journalism of attachment

Ruigrok (Citation2005, Citation2006) identifies three characteristics of journalism of attachment. First, Ruigrok et al. (Citation2005, p. 160) state that “conflict-related news focuses not just on causes of the conflict, but also on its victims: good people to whom bad things happen”. According to Bell (Citation1995, 99)

speaking from his own experience in former Yugoslavia, media personalized the conflict, so that people elsewhere could relate to it more easily as if it were their homes and families being targeted, and not some foreign conflict of no consequence.

Ruigrok (Citation2008) further claims that attached journalists take sides with what they consider to be the main victims of war when reporting on it. In doing so, the conflict is portrayed in such a way that “good guys” and “bad guys”, “good” versus “evil” are clearly distinguished. When practicing journalism of attachment, they are actively getting involved in the discussion, distinguishing “right” and “wrong” according to their own views and proposing their own chosen solution to the conflict at hand (Ruigrok Citation2008). In this regard, attached journalists can play a dominant role in creating and promoting a specific frame. For advocates of this style of journalism, objectivity and accuracy are still “sacred” (Vulliamy Citation1999). However, in conflicts where there are no “good guys” and “bad guys”, the focus on individual suffering forms an alternative for journalists. These reports produce human-interest stories, which draw the audience attention to a conflict that might otherwise be regarded as irrelevant (Ruigrok Citation2006).

Ruigrok et al. (Citation2005, p. 158) have applied this notion to their studies on Dutch media reporting on the Bosnian war “finding that Dutch media played an important role in creating a rather stereotypical, simplified picture of the Bosnian conflict”. Obermann and Dijkink (Citation2008) found similar results in their article on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict; and Fengler et al. (Citation2020) found that the Dutch newspapers paid very limited coverage to the Ukrainian conflict in 2014.

Second, according to Kepplinger et al. (Citation1991, p. 250), “attached journalists, who already have a framework in mind about the conflict to cover, use ‘instrumental actualisation’, up- or downplaying certain events or statements of experts in order to support their own opinions”. In doing so, attached journalists select different events and present them in a different way without giving their explicit opinion about the events at hand. Kepplinger et al. (Citation1991) argue that news selection is an intentional act to achieve the individual aims of the journalist involved. Their research concludes that journalists’ subjective beliefs account for about one-third of the variance in decisions during the news selection process. This is in line with Entman’s (Citation2007) research on the selection and reporting of news. According to Entman (Citation2007, p. 163), journalists present “a few elements of perceived reality and assembling a narrative that highlights connections among them to promote a particular interpretation”. As a result, they cover the events in such a way as to motivate public action to do something about the situation. According to Ruigrok (Citation2008), attached journalists in Bosnia had a clear goal in mind with their news coverage: triggering a military intervention to set free the victims of the war. With a specific goal in mind, attached journalists exhibit a functional model of journalistic practice. As explained above, this research is interested in the way in which Dutch journalist constructed their frames about the Second Karabakh war.

Another aspect of attachment can be “the selection of sources by using opportune witnesses” (Hagen, Citation1993, p. 320). Hagen (Citation1993, p. 320) argues that “journalists prefer to quote sources that support the journalist's political stance or their editorial line. By selecting sources that put forward a certain opinion, journalists can convey the impression that experts share their personal views”. According to Van Gorp (Citation2005), this process includes identified metaphors, catch phrases, lexical choices, graphics, stereotypes, dramatic characters and visual images. These sources contribute greatly to “the (political) work that creates and defines the public's beliefs about the causes of social issues, and they thereby justify the action of certain actors” (Van Gorp, Citation2005, p. 485). By selecting specific quotes, journalists make a piece of information more noticeable, meaningful, or memorable to audiences (Entman Citation1993, p. 52). Additionally, by selecting and reporting, news media influence not so much “what we think, but it tells us what to think about” (Ruigrok et al. Citation2005). Therefore, “much of what readers learn may have little to do with the facts, names, and figures that journalists try to present so accurately” (Bird and Dardenne Citation1988, p. 190).

It is important to consider the different forms of news coverage, namely factual news coverage and op-eds to trace journalism of attachment in news coverage. The framework that attached journalists have in mind is most clearly presented in editorials and op-ed pieces by journalists on the forum pages. However, Ruigrok (Citation2008, p. 45) argues that “attached journalists do not confine their opinions to the op-ed pieces and editorials, but their opinions will also pervade the straight news coverage”. In this regard, the coding groups will include both op-ed articles and straight news coverage.

In addition to selection and salience, this paper argues that journalism of attachment can also imply the act of silencing a group's voice in practice or in discourse. While highlighting a particular aspect of the conflict, attached journalists silence other parts of the conflict. According to Dingli (Citation2015, p. 160)

silence in its strict definition, is the complete absence of voice or sound and a state in which one abstains entirely from speech. She argues that the silent issues in global politics are not physically voiceless; rather, they are politically silenced by external actors.

silences are not only absences; silences are exclusions. More specifically, any successful framing implies as a consequence the exclusion of other possible constructions of meaning. This means the inability of those who have been silenced to “speak” because their voices are either volume-less or unintelligible.

The code groups that will be assessed in light of the journalism of attachment and silence literature are those concerning historical facts, the use of city names, the use of sources, perceptions, and references to international decisions.

Methodology

In order to evaluate the presence of framing mechanisms in Dutch media reporting on the Second Karabakh war, this research conducted a qualitative data analysis of 188 articles (8 op-eds and 180 news articles) on the topic in nine major national Dutch news media. To trace journalism of attachment in news coverage, this article will consider the different forms of news coverage: the news in which journalists put forward their own opinions; the news in which they bring facts; and the news in which journalists allow stakeholders to speak. Journalism of attachment can be researched on an individual and collective level (surface phenomenon). When a group of newspapers becomes attached, the effects of their combined coverage can be far more significant. In such a situation, journalism of attachment can be seen as a surface phenomenon occurring throughout the total news coverage of a newspaper (Ruigrok Citation2006). In this study, I will concentrate on journalism of attachment as a surface phenomenon.

The news media were selected based on the size of their readership (Ministerie van Onderwijs, Cultuur en Wetenschap S.D., latest data from 2017, FDMG Citation2021). They include (in order of readership): De Telegraaf, Algemeen Dagblad, de Volkskrant, NRC Handelsblad, Trouw, het Financieele Dagblad, and the online news media NU, RTL Nieuws, and NOS.Footnote2 A distinction can still be made between more left-wing, central, and right-leaning media, and in the analysis I will check whether or not any obvious patterns can be discerned. More specifically, De Volkskrant and Trouw would be more left-wing; NRC liberal-conservative; and Telegraaf and AD are considered right-wing (Bakker & Vasterman in Terzis Citation2007, p. 147).

During the period between 27 September and 10 November 2020, 188 articles were published across these newspapers. When looking at the number of articles published by each medium, I can already observe some differences between them, with NRC Handelsblad publishing 45 news articles during the analysed period, and RTL and Financieele Dagblad only 8 each.

Each of these articles was coded using the codes established on the basis of the abovementioned literature. The coding process was divided into two stages. First, the draft coding book was produced with codes divided in coding groups. The code book was also open to creating new codes where needed during the coding process. Second, the content of the articles was coded, using Atlas.ti software. Coding was done at the paragraph level, which means a code or coding group may have been applied multiple times per article. This research is based on an independent coding of all articles and each article and coding were double-checked by another Dutch native speaker. The final dataset consisted of 1444 quotations across 83 codes, divided in 13 code groups. In order to explain and visualise the data and coding groups I used graphs in the results part.

Results

Frames on the nature of the conflict

The research started its investigation of the textual framework by examining how Dutch newspapers frame the Karabakh conflict. As mentioned above, it is “one of the most complex conflicts in the post-Soviet space as it reflects political, legal, ethnic and historical factors” (Abushov Citation2010). Therefore, it is important to investigate whether the Dutch media understands its complexity and how results explain it to their audience (see below ).

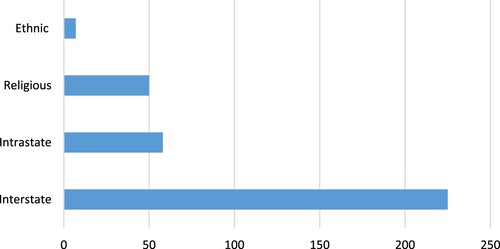

As mentioned, attached journalists play an important role in creating and promoting a specific frame and tone. The paper found four main frames that were used to different degrees to explain the conflict: interstate (a conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan); intrastate (a conflict between N-K as a separatist region and Azerbaijan), religious (Christian Armenia versus Muslim Azerbaijan) and geopolitical (the conflict being closely linked to regional or global power dynamics). First, the newspapers referred to the interstate frame 64% (217 times) to explain the conflicting parties. One reason why this was so often used is that the ceasefire and peace negotiations were conducted between the Armenian and Azerbaijani governments.

In contrast, the intrastate frame was only used 19% (61 times). This mostly happened when they provided background information or if they referred to the statements of the de facto authorities in N-K. However, the news media used this framework in a confusing way by mixing intrastate and interstate aspects within the same article. For example, NRC (October Citation28, Citation2020b) mentions that “Nagorno-Karabakh is recognized as part of Azerbaijan but in practice, it is an independent region where mainly Armenians live. Both Azerbaijan and Armenia believe that Nagorno-Karabakh belongs to them”. Additionally, the regions surrounding N-K were only mentioned in 10% (directly 11 times, and another 19 times indirectly). This is a simplification of the conflict situation because the conflict includes both Nagorno-Karabakh and seven surrounding districts.

While the studied newspapers made the interstate, intrastate and religious frameworks more salient, the ethnic aspect of the conflict was mentioned only in 2% (7 times). This was only done by the AD (1 time), NRC (2), Telegraaf (2) and Trouw (2). According to Allen and Seaton, conflicts presented as being concerned with ethnicity and difference have an immediate distancing effect on media audiences, for ethnicity is seen as something that those strange and wild people have, not “us”.

The religious framework was present much more prominently and was mentioned both directly and implicitly, by all outlets 15% (50 times). For example, according to the RTL Middle East correspondent “[ … ] the conflict is not just about land. More importantly, it's also about religion”. Or: “It is also a conflict between (Armenian) Christians and (Azerbaijani) Muslims. That makes this so incredibly sensitive and painful” (RTL, Citation27 September Citation2020). NRC referred to the conflict as “the most recent exchange of violence in a decades-old conflict over the territory between mainly Orthodox Christian Armenia and predominantly Muslim Azerbaijan” (NRC, September Citation27, Citation2020a). The newspapers also used the religious frame to refer to the competition between Turkey and Russia. For example, De Volkskrant mentioned that “the war puts global powers against each other. Islamic Azerbaijan is provided with modern weapons by NATO member Turkey. Russia supports Christian Armenia” (Volkskrant, October Citation26, Citation2020a). The conflict is not considered a religious one, however, by most experts and even government officials (see e.g. De Waal Citation2013, p. 9, Armenpress, December Citation24, Citation2021). According to Armen Sarkissian, the former President of Armenia, “the conflict was never, never a religious war. Armenia has wonderful relations with a lot of states where Islam is a major religion” (Armenpress, December Citation24, Citation2021). Similarly, the Azerbaijani government and local Muslim leaders mentioned that the Second Karabakh war had no religious dimension (The State Committee on Religious Associations of the Republic of Azerbaijan, October Citation15, Citation2020). Broers (Citation2019) argues that framing the conflict in religious terms serves more to locate an obscure conflict than to accurately convey its nature. The religious framework is one of the important misinterpretations of the conflict resulting from journalistic oversimplification, ignorance and stereotypical assumptions.

NOS (11 times), De Volkskrant (7), and NRC (7) most frequently highlighted the religious frame the most among all the studied media. This framework is present in the op-ed and news articles. One of the possible reasons for this religious framing is that some newspapers assigned non-expert, and mainly the Middle East, journalists to the South Caucasus, who may not actually be familiar with the regional context of the South Caucasus, which is substantially different from that in the Middle East. Therefore, these journalists already had a (religious) framework in mind about the conflict to cover. For example, while reading the articles in De Volkskrant, I found that one of the journalists was based in the Middle East and had never reported about the Karabakh conflict before. When asked by a fellow respondent in De Volkskrant “How did you, our Middle East correspondent, end up in Nagorno-Karabakh?” the journalist replied that:

Due to the covid restrictions, Tom [the journalist responsible for the South Caucasus] cannot leave Moscow at the moment. [ …] These are crazy times, which force you to make strange choices. But I talked a lot about the conflict with Tom and coincidentally, I also have a lot of Armenian contacts. In Beirut, where I live, you have a large Armenian community. (Bahara, Citation2020)

Framing: geopolitical context

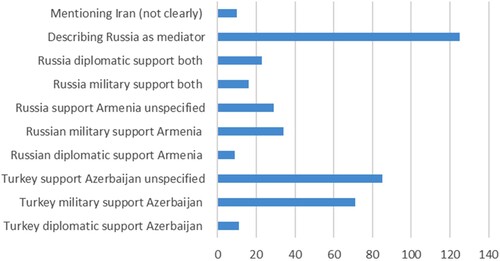

The geopolitical frame was a very dominant one. Rather than focusing on the war as a conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan, or between Azerbaijan and N-K, the newspapers additionally framed the conflict as a geopolitical struggle between regional powers, particularly Turkey and Russia. Turkey was presented as the main regional power supporting Azerbaijan. For example, Trouw (November Citation8, Citation2020) mentioned that “Azerbaijan can count on the support of ‘brother state’ Turkey in the conflict”. NOS (October Citation17, Citation2020a) reported that “Ankara supports Islamic Azerbaijan”, thereby including an indirect religious frame as well ().

The type of support provided by either Russia or Turkey was sometimes specified, and sometimes kept vague. While reporting on Turkey's support for Azerbaijan, the newspapers (50%/85 times) did not specify the type of support. The newspapers also did not always specify Russia's support (12.7%/29 times).

Turkey's military support for Azerbaijan was mentioned quite frequently (41%/71 times), specifically by Telegraaf (19 times), Trouw (12) and NRC (11). In addition to reporting on the delivery of weapons, it was incorrectly mentioned by the Volkskrant (Citation23 October Citation2020b) that Turkey had also sent money to Azerbaijan. Azerbaijan has military trade relations with several countries, namely Russia, Israel, Ukraine, Belarus, and Turkey. According to the Stockholm Peace Research Institute (SPRI) (Kuimova et al. Citation2021), “Turkey accounted for 2.9 per cent of Azerbaijan's imports of major arms over the decade 2011–20”.

While Turkey's military support to Azerbaijan was emphasised, the newspapers gave less attention to the Russian military support for Armenia (14.9%/34 times). There was also relatively little attention to the fact that Russia has provided military support to both Armenia and Azerbaijan. Yet, Kuimova et al. (Citation2021) show that “despite Russia acting as a leading mediator in the conflict between the two countries, in 2011–20, it accounted for 94% of Armenia's imports of major arms and 60% of Azerbaijan's”.

In contrast to military support, the research found that both Turkey’s diplomatic support to Azerbaijan, and Russia’s diplomatic support to Armenia specifically, received less attention from the newspapers (namely 6.5%/11 times regarding Turkey’s diplomatic support; 1.7%/3 times regarding Turkey’s mediating role; and 3.9%/9 times of the coded quotations concerning Russian diplomatic support).

While Turkey's role in the conflict has been described in mostly negative terms, the newspapers mainly described Russia in a more positive manner, particularly as a mediator (51%/125 times) in the conflict. Russia did play a very active and diplomatic role, and since Russia is a Co-Chair of the OSCE Minsk group, one may argue that it is only natural to highlight this role. However, the research found that media often did not mention Russia in light of the Minsk group at all.

According to Vladisavljević (Citation2015), by selecting and reporting news, the media highlights some problems, different sets of facts and people, and not others. One of the main disturbances I found is that the role of Iran in the region received very limited attention (namely, 2.8%/11 times) of the coded quotations. Yet, Iran did play a role in the conflict by offering to mediate, and it also has relations with Armenia and, to a lesser extent, with Azerbaijan (Broers Citation2019). More specifically, Iran has direct borders with both parties to the conflict and has sought to prevent any expansion of the conflict into its territories since the outset of the conflict. Iran is also interested in prolonging the status quo established by the Bishkek agreement, and blocking the intervention of the non-regional powers (e.g. Israel and the US). Therefore, Iran unsuccessfully attempted to achieve a ceasefire between Armenia and Azerbaijan in the early 1990s. Furthermore, the world's largest single community of ethnic Azerbaijanis lives in Iran. However, Iran's relations with Armenia are rhetorically warmer than with Azerbaijan because of Baku's close relations with Israel, and its energy agreements with the West (Mahammadi and Huseynov Citation2022). While Turkey closed its land borders with Armenia in the 1990s because of the first Karabakh war, Iran provided Armenia with an open southern border and an important resource in overcoming the blockade (Mahammadi and Huseynov Citation2022). Additionally, Armenia has solved its acute energy problems thanks to the gas pipeline from Iran (De Waal Citation2013). Considering these factors, one can argue that Iran's role in the conflict should have been highlighted.

Nevertheless, AD, Trouw, RTL, FD, NU did not mention Iran at all. This might indicate a form of silencing. This is what Wolfsfeld (Citation1997, p. 34) calls the “narrative fit between incoming information and existing media frames”. Nevertheless, this geopolitical framing downplays the significance and independent agency of local actors, which resulted in an inaccurate representation of developments in the conflict.

Salience and silence

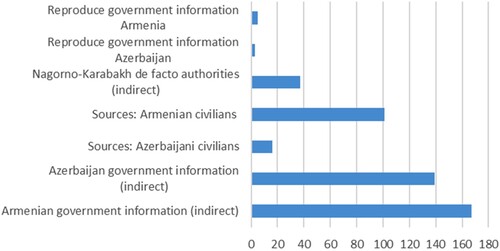

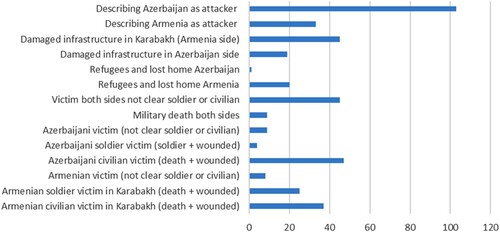

Looking at the use of sources, one can see that government sources were cited quite frequently, but nearly always in an indirect manner, for example, by reporting on decisions announced by either side or by mentioning that the different authorities had made accusations or denied those. Parts of press conferences were translated and selected and put into context and were therefore considered as “indirect use of government sources”, in the analysis. However, the overall number of coded quotations referring to government information was not balanced as the newspapers referred to the Azerbaijani government 41.5%/139 times but they referred to the Armenian government and the de facto Karabakh authorities combined 58.5%/196 times. In line with Hagen’s (Citation1993) argument, one could argue that sources were selected on an unequal and imbalanced basis ().

According to Wolfsfeld (Citation1997, p.4), antagonists in conflicts “compete over access to the news media and they compete over media frames”. There were only very few instances where information from either government was directly reproduced by the news media without editing (8 in total, 5 photos and 3 Tweets). Most of the reproduced information could be found in De Telegraaf (5), which would for instance re-tweet President Aliyev's tweets, or display pictures of military action, released by the Armenian or Azerbaijani Ministries of Defence. This does suggest a critical stance towards government-produced visuals and information by most Dutch media.

In addition to government information, several articles also shared views of civilians. Having conversations with “regular citizens” is a popular means for Western media to “contextualise” conflicts but obviously tends to be unrepresentative (Luyendijk Citation2006, p. 54). A few articles (14%/16 quotations) displayed the views of Azerbaijani citizens, be it in Azerbaijan itself or of Azerbaijanis living in the Netherlands. However, the overall majority (86%/101 quotations) of “citizens views” were from Armenian civilians, again both in Karabakh, Armenia, and the Netherlands. Individuals were, for example, interviewed to express their concerns and share their personal stories. A few news articles told the stories of Armenian soldiers fighting at the front. However, there was much less attention for the “people behind the conflict” on the Azerbaijani side. The news medium that stood out in this regard is Algemeen Dagblad (AD), with 38 instances where Armenian civilians were directly used as a news source; versus 5 Azerbaijani civilians. For the Volkskrant, this was 23 instances citing Armenian civilians versus none citing Azerbaijani citizens. NRC, RTL and Telegraaf also cited only Armenian, and no Azerbaijani civilian sources. In line with the journalism of attachment, these findings illustrate that Dutch newspapers only focused on one part of the events and mainly quoted Armenian people in their coverage. These examples also illustrate the use of opportune witnesses because Volkskrant, NRC, RTL and Telegraaf chose specific stakeholders to cite in their publications. This means that journalists chose participants to direct the public discussion in a certain direction.

Implicit instrumental actualisation: historical context

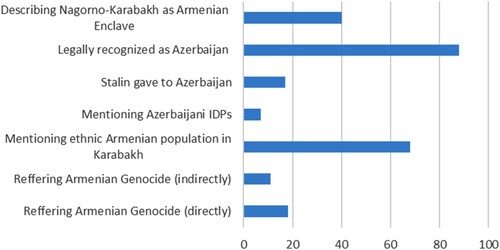

Most news coverage included very brief references to the historical context of the N-K conflict. They would, for instance, take the first war of 1988–1994 as a historical reference point. The conflict goes back further in time than 1988, however. A handful of articles (6%/17 times) from De Volkskrant, Trouw, NOS and NRC referred to developments in the 1920s, specifically to the argument that is sometimes posed, that Stalin would have given the region of N-K to Azerbaijan, implying that the historical claim to the land could therefore be disputed – but this argument has not been proved (Saparov Citation2018).

As mentioned, attached journalists can either up- or downplay certain sub-themes and contesting parties in their articles. While describing the historical, ethnic composition of the region, the studied newspapers mostly mentioned ethnic Armenians 24.3% (68 times), while not mentioning the Azerbaijani population that lived and lives in the region. In contrast to this, some of the articles referred several times (2.5%) to Azerbaijani Internally Displaced People (IDP), who were displaced during the first war (de Volkskrant 3 times, Trouw 1 time and RTL 3 times). Considering this, it can be argued that while highlighting a particular aspect of the Karabakh conflict, attached journalists silenced other parts of the conflict ().

Regarding the status of N-K, there generally appears to be quite a lot of confusion. On the one hand, 31.5%/88 times stated that the international community recognises Nagorno-Karabakh as part of Azerbaijan. On the other, most media (except for RTL and Telegraaf) simultaneously referred to N-K as an “Armenian enclave” (14.3%/40 times). NRC (18) and FD (9) used the term the “Armenian enclave” most frequently. Besides the contradiction, some have made the point that using the term “enclave” is incorrect when speaking about N-K, in the first place (Goltz Citation2012). According to the Oxford Public International law,

an enclave in international law is an isolated part of the territory of a State, which is entirely surrounded by the territory of only one foreign State—the surrounding, enclaving, or host State—so that it has no communication with the territory of the State to which it belongs—the mother or home State—other than through the territory of the host State.

Portrayed roles of conflicting parties

As explained in the conceptual part of this paper, “journalism of attachment” predominantly refers to the representation of conflicting parties as “right” and “wrong”, of “victims” or “aggressors” (Ruigrok Citation2008). In practice, this can for instance result in using certain sources but not others; or in making the suffering of some more visible than that of others. Citizens on both sides of this conflict have suffered greatly. Many civilians have died, have been wounded, have lost their homes or had to flee; and there were many deaths and wounded among the soldiers from both warring parties.

As said, there were civilian casualties on both sides of the conflict. International estimates are that 11 Armenian civilians and 72 Azerbaijani civilians lost their lives during the 2020 war (Amnesty International Citation2021, p. 7 and p. 13). Reporting on civilian victims on both sides of the conflict was relatively even, with 38% (48 mentions) from Azerbaijan, and 29% (37 mentions) from Karabakh and Armenia. Often, media would also simply refer to “casualties” without specifying on which side mentions.

Military casualties were estimated to be 3773 on the Armenian side and 2908 on the Azerbaijani side (Radio Free Europe, August 24, 2021; MoD Azerbaijan, October 21, 2021). Military deaths and wounded were reported much more frequently when it concerned Armenian soldiers 19.8% (25 times), versus 5.5% (7 mentions) regarding Azerbaijani soldiers; alongside 7% (9 instances) where military deaths on both sides were reported, but this could possibly be due to the fact that the Azerbaijani government did not issue official information on military casualties. This aspect is thus also linked to the issue of government control over information.

However, one aspect in which I did observe a clear discrepancy is the reporting on infrastructure damage and refugees. There are more references to damage on the Armenian side, with 70%/47 mentions referring to instances in Karabakh; and 30%/27 mentions regarding instances on the Azerbaijani side. However, this cannot be fully accounted for by the location of combat. The damage in residential parts of the Azerbaijani city Ganja, was mentioned several times, but not discussed in terms of the people affected: the implications for Azerbaijani civilians were only mentioned in terms of damage to infrastructure, whereas in the case of N-K, the focus was more on human suffering. According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Center (Citation2021, p. 47), the Second Karabakh war led to 84,000 new displacements in Azerbaijan in 2020. Many news media provided rather personalised accounts of Armenian people caught up in the conflict within Karabakh, and that personalised dimension appears to be the biggest difference in the reporting when it comes to victims of the war. This corresponds to the research findings regarding the use of civilian sources, where I also observed that there was more space for the viewpoints of Armenian citizens than for Azerbaijanis. Considering this, one may also argue that took sides in this conflict, by pointing out who is to blame for the conflict and who is the main victim in need of protection ().

Although not always transparent, the phenomenon of taking sides with the underdog often occurs when journalists frame conflicts (Ruigrok Citation2006). These are often portrayed in such a way that “attacker” versus “victim” are clearly distinguished. In line with this, the way the warring parties were described, often either as an attacker, or the attacked, was also inconsistent. Azerbaijan was described as attacker much more frequently than was Armenia (75%/103 times and 25%/33 times, respectively), especially by De Volkskrant and NRC. For example, NOS (Citation28 September Citation2020b) mentions that “the armed forces of oil-rich Azerbaijan are much stronger than those of impoverished Armenia”.

Discussion

As stated by Bird and Dardenne (Citation1988), newspapers retell stories in different ways. The findings illustrate that the Dutch newspapers’ reporting on the Second Karabakh War of 2020 was often oversimplified and lacked nuance. Specifically, the religious framework is one of the important misinterpretations in my opinion; and there was substantial contradiction over the status of Karabakh and the seven surrounding regions. The geopolitical frame overemphasised the role of Russia and Turkey at the expense of understanding the dynamics between Armenia and Azerbaijan. In doing so, the newspapers treated Armenia and Azerbaijan as mere pawns rather than as agents in their own right. Furthermore, the positive portrayal of Russia as a mediator overlooked that Russia is the largest exporter of arms to both Armenia and Azerbaijan. In general, Turkey's role was described in rather negative terms. Based on Obermann and Dijkink's work on the impact of large political events on news reporting of other issues, one explanation to be explored is that relations between Turkey and the Netherlands have deteriorated quite significantly over the past years, and this negative attribution may therefore come forward in news articles on Karabakh, too (Obermann & Dijkink Citation2008, p. 160). Possibly, an even broader factor may play a role in the reporting on Azerbaijan, namely a more negative view towards Islam, which might explain why religion is consistently mentioned when referring to Azerbaijan. An analysis of the frames on the historical context showed how little context was often provided in news articles, and how selective these were. As part of the frames, salience was given disproportionally to accounts of suffering of Armenian civilians, over those of Azerbaijani citizens. Journalism of attachment, lastly, became apparent when looking at the reporting of casualties, victims, and attackers, with more attention for the “human” dimension in Armenia and N-K, as opposed to in Azerbaijan.

One may ask whether the frames changed over the course of the war, and whether media were able to represent the regional context more accurately as time progressed? The short answer to this question is both yes and no. On the one hand, the religious frame was maintained throughout time (especially by NOS, NRC and De Volkskrant). Other references that, in my opinion, are not conducive to accurate reporting, such as the references to genocide, or the historical argument about Stalin's decisions, were also still used towards the end of the conflict. A cross-check analysis shows that both news and op-eds articles in NRC and reports by De Volkskrant, applied several of these frames simultaneously, using the following references: “religion”, “Stalin”, “genocide”, “Armenian enclave”, “aggressive Azerbaijan”.

In a similar vein, while Telegraph, NRC, NOS, Trouw and de Volkskrant kept highlighting Turkey's (2.6%) military trade with Azerbaijan throughout their stories, Russia's military relations with both countries (60% Azerbaijan, 93% Armenia) were mentioned only either in the first or in the last articles. Trouw paid significant attention to the role of Turkey. As mentioned, the seven surrounding districts and the four UN resolutions received very limited coverage: either in their first or last articles. Although AD, Trouw, De Volkskrant and NU stopped referring to N-K as an Armenian enclave from approximately the middle of the war, NRC and the FD kept this incorrect reference throughout their reporting.

While a significant degree of bias could be found in every news medium that I examined, there appear to be some variations across the media. As was shown in the analysis above, government information was reproduced only very infrequently; but in most instances (5 out of 8) this was done by the Telegraaf. AD, NRC, NOS, Trouw and de Volkskrant did give more space to Armenian (government and civilian) sources in general. As a result, the facts and figures from the Azerbaijani side were silenced, namely Azerbaijani city names in Karabakh and Internally Displaced People. Therefore, in contrast to the 2019 Eurobarometer's findings on Dutch media, the paper found that the studied media did not always present a diversity of views and opinions while reporting on the Second Karabakh war.

Conclusion

This article has analysed Dutch media reporting on the Second Karabakh War. The article was based on nine newspapers and 188 articles in the Dutch media between 27 September 2020 and 10 November 2020. The paper investigated the tone of the reporting and the framing. In contrast to the 2019 Eurobarometer's findings on Dutch media, this paper found that the studied media did not present a diversity of views and opinions while reporting on the Second Karabakh war. Although the studied newspapers covered civilian victims from both sides, they presented Azerbaijan as an aggressor and Armenia as a weak side in the conflict. Overall, the article illustrated that the studied newspapers gave more space to the Armenian side of stories and less space to the Azerbaijani side of stories. Similar to the previous studies on Dutch media (e.g. Ruigrok et al Citation2005, Obermann & Dijkink Citation2008, Ruigrok Citation2008, Fengler et al. Citation2020), the article illustrated that Dutch newspapers created a rather stereotypical, simplified picture of the Second Karabakh war. The research also found that the predominantly negative tone towards Azerbaijan was limited to opinion pieces.

Although this research was based on documents from only the Netherlands during a specific time, the findings contribute to a more nuanced discussion about the Western media coverage of Post-Soviet conflicts. The findings suggest that journalists could work harder to highlight both sides on opinion pages, if they are concerned about the objective representation of their work in the media. For a foreign conflict, of which the Dutch public has little knowledge, balanced news coverage of the events is important in achieving a comprehensive understanding of the conflict.

In terms of the limitations of this article, this paper has focused particularly on the Second Karabakh war and nine Dutch newspapers, which has left other newspapers, the First Karabakh War and peace process unexamined. In this regard, further research is necessary to address whether other newspapers also followed similar reporting strategies, and how they reported the First Karabakh war or other Post-Soviet conflicts (e.g. Georgia-Abkhazia).

Coding_book_final.docx

Download MS Word (16.8 KB)Acknowledgement

For helpful comments on earlier versions of the contribution, the author would like to thank Mustafa Ali Sezal, Seiki Tanaka, and Senka Neuman-Stanivukovic as well as the reviewers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Research into any conflict is inherently sensitive. I want to add that as an author, I do not take a stance on the conflict. My view is that there has been terrible suffering on both sides, and that civilians on both sides have been the victims of this conflict.

2 NOS, NU.nl, and RTL are broadcasting media rather than newspapers, and have been included on grounds of them having among the highest readership.

References

- Abasov, A., and Khachatrian, H., 2006. Karabakh conflict: variants of settlement: concepts and reality. Munster: Noyan Tapan.

- Abushov, K., 2010. Regional level of conflict dynamics in the south Caucasus: Russia's policies towards the ethno-territorial conflicts (1991-2008). Diss. Westfälischen Wilhems-Univeristät.

- Altstadt, A., 2017. Frustrated democracy in post-Soviet Azerbaijan. Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson Center Press and New York: Columbia University Press.

- Amnesty International., 2021. Azerbaijan/Armenia: scores of civilians killed by indiscriminate use of weapons in conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh. Available from: https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/press-release/2021/01/azerbaijan-armenia-scores-of-civilians-killed-by-indiscriminate-use-of-weapons-in-conflict-over-nagorno-karabakh/ [Accessed February 2021].

- Armenpress., 2021. Nagorno Karabakh war has never been a religious war – Armenian president tells ArabNews, 24 December. Available from: https://armenpress.am/eng/news/1071588.html#.Yctc9P4w59M.twitter [Accessed 26 December 2021].

- Atanesyan, A., 2020. Media framing on armed conflicts: limits of peace journalism on the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. Journal of intervention and statebuilding, 14 (4), 534–550.

- Bahara, Hassan., 2020. Armeniërs zien een val van Nagorno-Karabach met veel angst tegemoet, het trauma van de genocide zit hier diep. Available from: https://www.volkskrant.nl/nieuws-achtergrond/armeniers-zien-een-val-van-nagorno-karabach-met-veel-angst-tegemoet-het-trauma-van-de-genocide-zit-hier-diep~b4d67ae1/ [Accessed November 2020].

- Bayramov, A., 2016. Silencing the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict and challenges of the four-day war. Security and human rights, 27 (1-2), 116–127.

- Bell, M., 1995. In harm’s way: memories of a war zone thug. London: Hamish Hamilton.

- Bird, S. E., & Dardenne, R. W. 1988. Myth, chronicle, and story - exploring the narrative qualities of news. In J.W. Carey (Ed.), Media, myths, and narratives - television and the press. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, 67–86.

- Bölükbaşı, S., 2011. Azerbaijan: a political history. London: I. B. Taurus.

- Broers, L., 2019. Armenia and Azerbaijan: anatomy of a rivalry. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Broers, L., 2020. Russia’s peace imposed on Armenia-Azerbaijan bloodshed. Chatham House. Avaiable from: https://www.chathamhouse.org/2020/11/russias-peace-imposed-armenia-azerbaijan-bloodshed [Accessed Date November 2020].

- Colby, B.N., 1975. Culture grammars: an anthropological approach to cognition may lead to theoretical models of microcultural processes. Science, 187 (4180), 913–919.

- De Waal, Th, 2013. Black garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan through peace and war. 2nd ed. London: New York University.

- De Waal, Th, 2021. Unfinished business in the Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict. 11 February. Available from: https://carnegieeurope.eu/2021/02/11/unfinished-business-in-armenia-azerbaijan-conflict-pub-83844 [Accessed 17 August 2021].

- Dingli, S., 2015. We need to talk about silence: re-examining silence in international relations theory. European journal of international relations, 21 (4), 721–742.

- Entman, R.M., 1993. Framing: towards clarification of a fractured paradigm. Mcquail’s reader in mass communication theory, 57 (1), 390–397.

- Entman, R.M., 2007. Framing bias: media in the distribution of power. Journal of communication, 57 (1), 163–173.

- FDMG., 2021. Het FD. Available from: https://fdmg.nl/merken/fd/ [Accessed 3 November 2021].

- Fengler, S., et al., 2020. The Ukraine conflict and the European media: a comparative study of newspapers in 13 European countries. Journalism, 21 (3), 399–422.

- Gasparyan, A., 2019. Understanding the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict: domestic politics and twenty-five years of fruitless negotiations 1994-2018. Caucasus survey, 7 (3), 235–250.

- Geukjian, O., 2012. Ethnicity, nationalism and conflict in the south Caucasus: Nagorno-Karabakh and the legacy of Soviet nationalities policy. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Geybullayeva, A., 2012. Nagorno Karabakh 2.0: how new media and track two diplomacy initiatives are fostering change. Journal of muslim minority affairs, 32 (2), 176–185.

- Goltz, Th, 2012. The success of the spin doctors: western media reporting on the Nagorno Karabakh conflict. Journal of muslim minority affairs, 32 (2), 186–195.

- Guliyev, F., and Gawrich, A., 2021. OSCE mediation strategies in eastern Ukraine and Nagorno-Karabakh: a comparative analysis. European security, 30 (4), 569–588.

- Hagen, L.M., 1993. ‘Opportune witnesses: an analysis of balance in the selection of sources and arguments in the leading German newspapers’ coverage of the census issue’. European journal of communication, 8 (3), 317–343.

- Internal Displacement Monitoring Center, 2021. Internal Displacement Index Report. Available from: https://www.internal-displacement.org/publications/internal-displacement-index-2021-report

- Internal Displacement Index Report, 2021. Available from: https://www.internaldisplacement.org/sites/default/files/publications/documents/IDMC_Internal_Displacement_Index_Report_2021.pdf.

- International Crisis Group., 2019. Digging out of deadlock in Nagorno-Karabakh. International Crisis Group. Available from: https://d2071andvip0wj.cloudfront.net/255-digging-out-of-deadlock.pdf [Accessed Date November 2021].

- Kepplinger, H.M., Brosius, H.B., and Staab, J.F., 1991. Instrumental actualization: a theory of mediated conflicts. European journal of communication, 6 (3), 263–290.

- Kuimova, A., Smith, J., and Wezeman, D.P. 2021. Arms transfers to conflict zones: The case of Nagorno-Karabakh. SIPRI.

- Li, L., 2021. “How to think about media policy silence. Media, culture & society, 43 (2), 359–368.

- Luyendijk, J. 2006. Het zijn net mensen [People Like us]. Amsterdam: Podium.

- Mahammadi, M., & Huseynov, V. 2022. Iran's Policies Toward the Karabakh Conflict. In The Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict (pp. 381-401). Routledge.

- Makili-Aliyev, K., 2019. Contested territories and international Law: a comparative study of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict and the Aland Islands Precedent. New York: Routledge.

- Ministerie van Onderwijs, Cultuur en Wetenschap, (S.D.). Landelijke en regionale dagbladen, oplages. Available from: https://www.ocwincijfers.nl/sectoren/cultuur-en-media/kengetallen-media/landelijke-en-regionale-dagbladen-oplages.

- Ministry of Defence, Azerbaijan., 2021. List of the servicemen fallen shehids in the patriotic war. Available from: https://mod.gov.az/en/news/list-of-the-servicemen-fallen-shehids-in-the-patriotic-war-38076.html [Accessed Date November 2021].

- NOS., 2020a. Erdogan: ‘Turkije met heel zijn hart en alle middelen’ achter Azerbeidzjan. NOS, Netherlands. Available from: https://nos.nl/artikel/2350154-erdogan-turkije-met-heel-zijn-hart-en-alle-middelen-achter-azerbeidzjan [Accessed Date September].

- NOS., 2020b. Azerbeidzjan meldt burgerdoden na Armeense aanval, Armenië ontkent Available from: https://nos.nl/artikel/2352657-azerbeidzjan-meldt-burgerdoden-na-armeense-aanval-armenie-ontkent [Accessed Date October].

- NRC., 2020a. Geweld weer opgelaaid tussen Armenië en Azerbeidzjan. NRC, Netherlands. Available from: https://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2020/09/27/geweld-weer-opgelaaid-tussen-buurlanden-armenie-en-azerbeidzjan-a4013708 [Accessed 27 September].

- NRC., 2020b. Derde poging bestand Nagorno Karabach bijna direct weer gebroken. Available from: https://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2020/10/27/derde-poging-bestand-nagorno-karabach-bijna-direct-weer-gebroken-a4017506 [Accessed 27 October].

- Obermann, L., and Dijklnk, G., 2008. Reframing international conflict after 9/11: an analysis of Dutch news about the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. Journal of international communication, 14 (2), 159–181.

- Publications Office of the European Union., 2019. Media use in the European Union. Available from:https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/c2fb9fad-db78-11ea-adf7-01aa75ed71a1/language-en [Accessed Date November 2021].

- Rossi, Ch, 2017. Nagorno-Karabakh and the Minsk group: the imperfect appeal of soft law in an overlapping neighborhood. Texas international Law journal, 52 (1), 45–70.

- RTL., 2020. Slepend militair grensconflict tussen Armenië en Azerbeidzjan escaleert. RTL Nieuws, Netherlands. https://www.rtlnieuws.nl/nieuws/artikel/5186488/armenie-azerbeidzjan-nagorno-karabach-grens-conflict-doden-militair-kaukasus#:∼:text=De20bergachtige20regio20Nagorno2DKarabach,9020financieel20gesteund20door20ArmeniC3AB [Accessed Date November 2021].

- Ruigrok, P. C. 2006. Journalism of attachment: Dutch newspapers during the Bosnian war. University of British Columbia Press.

- Ruigrok, N., 2008. Journalism of attachment and objectivity: Dutch journalists and the bosnian War. Media, war & conflict, 1 (3), 293–313.

- Ruigrok, Nel, de Ridder, Jan A., and Scholten, O., 2005. News coverage of the bosnian War in Dutch newspapers. In Philip Seib eds. Media and conflict in the twenty-first century. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 157–183.

- Saparov. A. 2018. Q&A with Arsène Saparov: No Evidence that Stalin “Gave” Karabakh to Azerbaijan. Available at: https://armenian.usc.edu/qa-with-arsene-saparov-no-evidence-that-stalin-gave-karabakh-to-azerbaijan/

- TASS., 2021. Pashinyan says about 4,000 Armenian troops killed in Nagorno-Karabakh. Published on 14.04.2021 at https://tass.com/world/1277921.

- Terzis, G. (Ed.). 2007. European media governance: National and regional dimensions. Intellect Books.

- The State Committee on Religious Associations of the Republic of Azerbaijan., 2020. Prezident İlham Əliyev: “Bizim hədəflərimiz arasında heç bir tarixi və ya dini hədəf yoxdur” Available from: https://scwra.gov.az/az/view/news/9565/prezident-ilham-eliyev-bizim-hedeflerimiz-arasinda-hech-bir-tarixi-ve- [Accessed Date June 2021].

- Trouw., 2020. Zware gevechten verwoesten strategische stad in Nagorno-Karabach. Available from: https://www.trouw.nl/buitenland/zware-gevechten-verwoesten-strategische-stad-in-nagorno-karabach~b9dff19a/ [Accessed Date June 2021].

- UNHCR., 2009. Azerbaijan: Analysis of gaps in the protection of internally displaced persons (IDP). UNHCR, The UN Refugee Agency. https://www.unhcr.org/4bd7edbd9.pdf.

- Van der Hoeven, R., and Kester, B., 2020. Demythologizing war journalism: motivation and role perception of Dutch war journalists. Media, war & conflict, 1–17.

- Van Gorp, Baldwin, 2005. Where is the frame? victims and intruders in the Belgian press coverage of the asylum issue. European journal of communication, 20 (4), 484–507.

- Von Oppen, K. 2009. Reporting from Bosnia: reconceptualising the notion of a ‘journalism of attachment’. Journal of Contemporary European Studies, 17 (1), 21–33.

- Vladisavljević, N., 2015. Media framing of political conflict: a review of the literature. Working Paper. MeCoDEM. Available from: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/117315/1/Vladisavljevic%202015_Media-%20framing%20of%20political%20conflict.pdf

- Volkskrant., 2020a. Ouderwetse loopgravenoorlog in Nagorno-Karabach, aan de rand van Europa. Available from: https://www.volkskrant.nl/nieuws-achtergrond/ouderwetse-loopgravenoorlog-in-nagorno-karabach-aan-de-rand-van-europa~b80d04d6/ [Accessed Date June 2021].

- Volkskrant., 2020b. Armeniërs zien een val van Nagorno-Karabach met veel angst tegemoet, het trauma van de genocide zit hier diep. Available from: https://www.volkskrant.nl/nieuws-achtergrond/armeniers-zien-een-val-van-nagorno-karabach-met-veel-angst-tegemoet-het-trauma-van-de-genocide-zit-hier-diep~b4d67ae1/ [Accessed Date June 2021].

- Vulliamy, E. 1999. “Neutrality” and the Absence of Reckoning: A Journalist's Account. Journal of International Affairs, 603–620.

- Wahl-Jorgensen, K., and Hanitzsch, T., 2009. The handbook of journalism studies. New York: Routledge.

- Wolfsfeld, G., 1997. Media and political conflict: news from the Middle East. Cambridge: Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge.