Abstract

Sustainable development has gender equality as one of its primary objectives. Although many countries have implemented policy changes aimed at addressing gender inequality, the issue of limited access to employment opportunities for women remains prevalent. This study investigates (1) the underlying beliefs held by hotel managers regarding the hiring of women, (2) the role of different pressures in increasing women participation, and (3) potential conflicts between policy reforms and manager beliefs. Three studies on the hospitality sector in Egypt were conducted using a mixed-methods approach. The first study involves interviews with 32 managers, the second is a quantitative analysis of data from 200 managers, and the third consists of in-depth interviews with 20 experts. Our findings demonstrate: (1) thirteen key female-hiring beliefs, which inform hotel managers’ hiring decisions; (2) perceived policy pressures play a significant role in the hiring of more women, but managers’ attitudes remain the most important determinant; and (3) four conflicts between policy-level reforms and managerial beliefs may arise, attenuating female hiring. This research creates a scenario-based model and proposes potential remedies.

Introduction

Gender equality and sustainability are inextricably linked. According to current studies on sustainable tourism, “no tourism can be sustainable without gender equality” (Alarcón & Cole, Citation2019, p. 903). Sustainable Development Goal 5 emphasises the importance of empowering women and girls, providing equitable opportunities, and promoting inclusivity and fairness—all of which are necessary components of sustainable tourism (Alarcón & Cole, Citation2019; EEger et al., Citation2022). Eger et al. (Citation2022) highlighted the intersection of gender and sustainable tourism in a recent special issue on “Gender and Tourism Sustainability.” Ferguson and Alarcón (2015), on the other hand, observe that one of the major challenges for sustainable tourism is the unwillingness to incorporate gender analysis and equality as core principles. As a result, they advocate for gender equality in the theory and practise of sustainable tourism.

Gender equality policies—such as increasing female labour-force participation—are increasing across countries due to global political and social pressures (International Labour Organization, Citation2020; Kato, Citation2019; UNWTO, Citation2019). However, gender inequality and stereotypes still exist at the operational level (Cooper et al., Citation2021; Mickey, Citation2022; Priola & Chaudhry, Citation2021; Xiong et al., Citation2022). Extant research suggests that managers play a critical role in hiring and empowering women (Ng & Sears, Citation2020; Williamson et al., Citation2020), but managers’ attitudes towards hiring women should agree with gender equality policies (Elhoushy & El-Said, Citation2020). So far, no studies have examined whether operational-level manager beliefs support or oppose the ongoing policy reforms to increase female participation in the workforce. This is problematic, as the lack of assessment makes it difficult to determine the effectiveness of such policies and to identify potential remedies for weaknesses, thereby hindering efforts to achieve gender equality. The current study emphasises this tension and underlines potential policy-operational conflicts.

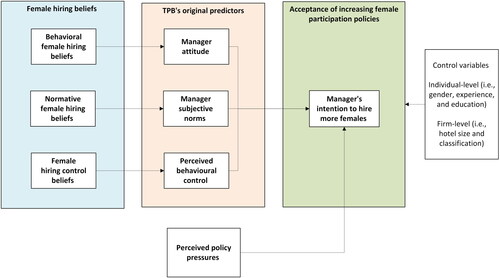

Theoretically, the current study follows a reasoned action approach that traces female hiring behaviour, through intention, to a manager’s attitudes, as well as beliefs (Ajzen, Citation1991; Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation2010). Specifically, an extended theory of planned behaviour (TPB) framework is used to examine the relationships between female-hiring beliefs and managers’ intentions to hire more female employees, given the surging pressures to increase female participation. In addition, institutional theory is expected to augment the TPB by including perceived policy pressures as an additional predictor of manager decisions (Jain et al., Citation2020). As such, this study examines managers’ acceptance of increasing female participation (i.e. intentions to hire more female employees) considering four elements: personal (i.e. attitude), social (i.e. subjective norms), contextual (i.e. perceived behavioural control (PBC)), and policy (i.e. perceived policy pressure).

This paper considers the hospitality industry in Egypt as a noteworthy setting for two reasons. First, the hospitality and tourism industry has been assigned a pivotal role in empowering women, improving their quality of life, providing a pathway to economic participation and altering the wider sociocultural perceptions of women (Figueroa-Domecq et al., Citation2022; Kato, Citation2019; Nassani et al., Citation2019; Santero-Sanchez et al., Citation2015; Tucker & Boonabaana, Citation2012; UNWTO, Citation2019). However, this industry is still experiencing severe gender inequalities (Alarcón & Cole, Citation2019; Ferguson & Alarcón, 2015; Liu et al., Citation2020), from limited access to senior positions and payment gaps (Hutchings et al., Citation2020; Nagar, Citation2021), which are universally observed issues, to the absence of women employees altogether in some regions (Rinaldi & Salerno, Citation2020). The UNWTO (Citation2021) considers the COVID-19 pandemic a feasible opportunity to revisit these issues. Specifically, the introduction of gender-responsive policies that promote the maintenance of flexible working conditions, and the use of digital technologies that were so prevalent during the crisis can reduce barriers to job and training opportunities for women in the tourism sector. Second, despite taking serious steps to protect women’s rights to work, both constitutionally and legally (McLarney, Citation2016), Egypt continues to experience low female participation, at only 15.6% of the labour force (International Labour Organization, Citation2020). Women’s participation in hospitality and tourism is especially poor, at only 5.3% (CAPMAS, Citation2021). As a result, policymakers have initiated reforms aiming to empower women and significantly increase female participation in tourism and hospitality (Egypt 2030, 2030, 2030, Citation2016). Thus, addressing female-hiring beliefs and policy reforms in this setting can contribute to closing the previously defined gap in the literature.

The objectives of the current study are threefold: (1) to explore female-hiring beliefs, at the operational level, using a qualitative approach; (2) to examine the role of beliefs in shaping female-hiring intentions and increasing women’s employment in hospitality; and (3) to explore any potential conflicts that may arise between policy-level reforms and manager beliefs. This is important in the face of the inconsistencies between external policy and internal practice highlighted in the literature (Kele & Cassell, Citation2023).

To achieve the objectives of this research, a rigorous mixed-methods approach was adopted, following the guidelines of Creswell (Citation2014) for exploratory sequential mixed methods design. In this design, Study 1 was conducted to explore and analyse the qualitative data on female-hiring beliefs held by hotel managers. Building on the results of Study 1, Study 2 collected and analysed quantitative data to investigate the effect of these beliefs on managers’ attitudes, social norms and perceived behavioural control over female hiring. Furthermore, Study 2 examined the role of four influential determinants of female-hiring intentions: managers’ attitudes (personal), subjective norms (social), perceived behavioural control (contextual) and perceived policy pressure (coercive). By taking into account multiple levels of analysis, this study addresses the complex and multifaceted nature of gender inequalities, which can exist at individual, organisational and market levels (Cooper et al., Citation2021). Lastly, Study 3 was conducted to provide a deeper understanding of the potential conflicts between policy and manager beliefs, using in-depth interviews with practitioners and academics. By drawing on the insights generated from Studies 1 and 2, as well as from the wider literature, Study 3 examines the specific conflicts that may arise when implementing policy-level reforms aimed at increasing female participation in the hotel industry. Four potential conflicts between policy reforms and manager beliefs are identified and discussed. This multi-methods approach allowed us to triangulate the data and increase the validity and reliability of the findings. Our study proposes a scenario-based model, which contributes to innovative research. In addition, we discuss scenario-based remedies and emphasise the need for managers to participate in policymaking to ensure policy acceptance.

Review of literature and theoretical background

Gender beliefs, hiring attitudes and manager behaviour

The TPB is a framework for predicting a person’s behaviour based on their intention (Ajzen, Citation1991). A person’s intention is affected by attitude, perceptions of subjective norms and PBC over that behaviour (Ajzen & Cote, Citation2010). These determinants are themselves functions of beliefs (Ajzen, Citation1991). Beliefs are the foundation of a person’s understanding of, and responses to, the world they live Ajzen & Cote, Citation2010). The TPB considers three distinct types of beliefs, namely behavioural, normative and control (Ajzen, Citation1991). Behavioural beliefs are beliefs about consequences (Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation2010), i.e. the expected outcomes of performing a particular behaviour (Ajzen, Citation1991). Normative beliefs concern the approval, or disapproval (Ajzen, Citation1991), of a person’s referents, such as friends, family and colleagues (Ajzen & Cote, Citation2010). Control beliefs are beliefs about the presence or absence of factors that can facilitate or inhibit the execution of the behaviour (Ajzen, Citation1991), such as money, capability and time (Ajzen & Cote, Citation2010).

An attitude is a person’s expectation that the outcome of a particular behaviour will be good or bad (Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation2010). Similarly, subjective norms are formed by the summation of a person’s normative beliefs (Ajzen, Citation1991). As such, subjective norms can be understood as the perceived social pressure to perform a behaviour (Ajzen & Cote, Citation2010). Similarly, PBC is formed by the summation of a person’s control beliefs (Ajzen, Citation1991). PBC can be appreciated as a person’s perception of how easy, or difficult, it is to perform a behaviour (Ajzen & Cote, Citation2010). Behavioural intention is the degree to which a person plans to perform a behaviour (Ajzen, Citation1991). The likelihood of performing a behaviour increases as intention becomes stronger (Ajzen, Citation1991).

As the TPB links behaviour to intention and accurately traces hiring intention to personal beliefs through attitudes and perceptions, it is an ideal framework to fulfil the aim of this research paper. By uncovering managers’ beliefs about female employees, and seeing how they influence managers’ attitudes about, and intentions to, hire women, the TBP will allow the authors to understand the underlying reasons for managers’ poor female-hiring behaviour in the Egyptian hospitality industry. Consequently, it will be possible to comment on the discrepancies, if any, between national policies to promote female employment and the actual hiring practices of hospitality firms.

Previous research has uncovered a range of beliefs about female workers in tourism and hospitality, many of which are negative. These include the beliefs that women are physically weaker, less competent, less committed, less flexible and more likely to suffer from work-life imbalance than men (Alberti & Iannuzzi, Citation2020; Carvalho et al., Citation2019; Hutchings et al., Citation2020). Organisational leaders and co-workers have been found to have a strong influence on hiring behaviours (Kim et al., Citation2020; Thébaud & Pedulla, Citation2016). For example, senior managers’ beliefs about diversity have a strong effect on hiring practices (Buengeler et al., Citation2018; Ng & Sears, Citation2020). Beliefs such as women need their husbands’ permission to work, certain roles are difficult for women (Carvalho et al., Citation2019; LaPan et al., Citation2022) and the masculine culture in hospitality (Calinaud et al., Citation2021; Mooney et al., Citation2017) have often been cited as inhibitors to hiring women. Conversely, the availability of support programs and family-friendly policies have been discussed as facilitating factors (e.g. Calinaud et al., Citation2021; Dashper, Citation2020)

Empirically, the impact of attitude on intention has been demonstrated in examining employer intentions to hire people with mental disabilities (Lettieri et al., Citation2021). The impact of subjective norms on intentions has, likewise, been supported in predicting employer intentions to hire visually impaired persons (McDonnall & Lund, Citation2020). Previous research has similarly supported PBC in predicting managers’ intentions to hire disabled workers (Ang et al., Citation2015). Although prior studies have used the TPB to explore female-hiring behaviours (e.g. Elhoushy & El-Said, Citation2020), these studies focused on the direct predictors of intention, while neglecting the underlying behavioural, normative and control beliefs.

Cultural and social conditions in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region can also inform hiring decisions (Barsoum, Citation2019). For example, society is still traditional, considering women’s roles to be traditional ones such as mothers and wives (Solati, Citation2017). The perceived responsibility that a woman has towards her family is identified as a key barrier to female employment (Lekchiri & Eversole, Citation2021). Employed Arab women tend to report that their work life, which may include long working hours, working nights and sleeping outside of the home (Shaya & Khait, Citation2017), interferes with their personal life, causing conflict with their husbands and parents (Barsoum, Citation2019). The weight of culture in forming managers’ decisions is highlighted by Eger et al. (Citation2022) study of Saudi Arabian firms. Although they found that managers supported, and were interested in increasing, female employment within their firms, they noticed that personal opinions on the cultural appropriateness of physical spaces and tasks restricted their ability to act. Firstly, managers believed that women and men should not work alongside each other and that offices with female employees should have segregated workspaces. Secondly, managers believed that women should not participate in physical work or meetings with male employees, and many thought that administrative and secretarial work was more appropriate.

Policy pressures for gender equality in tourism employment

Institutional theory is based on the idea of “myths,” which are the popular and widely accepted beliefs that society has about how organisations in a specific environment should be structured and behave (Meyer & Rowan, Citation1977). Businesses feel pressured to embrace myths, as failure to do so negatively influences the way their stakeholders perceive them, ultimately affecting their survival (Zucker, Citation1987). Yet, as adherence to these popular beliefs often comes at a cost to profitability, the theory also posits that businesses will only adopt myths ceremoniously (Su et al., Citation2017). That is to say, businesses will make grand and public gestures of their support and endorsement, although they may be applying very few of these beliefs to their conduct or structure (Meyer & Rowan, Citation1977). Therefore, the theory implies that businesses will systematically resist change and act with a kind of reluctance to the new myths they encounter, especially when the adoption of these popular beliefs results in some loss of resources or requires some additional investment (Zucker, Citation1987).

In response, the new institutional theory proposes that certain pressures, namely normative, mimetic and coercive, could catalyse and oblige a more genuine adoption of myths (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1983). Normative pressure refers to the desire that a group of similar organisations, such as in industry, has to establish standards and professionalise conduct for their area of activity (Liu et al., Citation2010). As a result, businesses are forced to conform to these standards if they want to be part of the industry. Mimetic pressure concerns the uncertainty that an organisation has concerning the future, and its decision to copy the behaviour and structure of others as a result (Latif et al., Citation2020). Coercive pressures represent “the formal and informal pressures exerted on organisations by other organizations upon which they are dependent” (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1983). While this usually takes the form of government-imposed requirements, it may also come from the influence that non-governmental organisations have (Sari et al., Citation2021), or the business and cultural customs dictated by suppliers and customers (Martínez-Ferrero & García-Sánchez, Citation2017). Therefore, in contrast to the TPB, in which beliefs are internal and personal (Ajzen, Citation1991), the pressures of the institutional theory are external and organisational (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1983).

Through the lens of institutional theory, the most notable coercive pressures in female hiring contexts tend to be government regulations and laws (Labelle et al., Citation2015; Mensi-Klarbach et al., Citation2021). Prior research has demonstrated the influence of these coercive pressures across different contexts, such as gender quota laws on female board membership (Rigolini & Huse, Citation2021) and anti-discrimination laws around the hiring of disabled or homosexual employees (Harcourt et al., Citation2005; Horvath & Ryan, Citation2003). The role that government-imposed rules and regulations can play has been emphasised by the United Nations, which states that “implementing new legal frameworks regarding female equality in the workplace […] is crucial to ending the gender-based discrimination prevalent in many countries around the world” (UNIFIL, Citation2021). The potential of coercive pressures is reinforced by Bobbit-Zeher (Citation2011) study on anti-discrimination workplace policies across a variety of different settings (i.e. male-only, female-only and male-female-integrated commercial firms). Although her research cannot confirm a connection between gender stereotyping and the absence of anti-discrimination policies, her results show how managers can pick and choose which policies they apply according to their own beliefs about female employment. This implies that voids in policy structures, in which application depends on individual discretion, allow gender-based discrimination to thrive.

Egypt has a significant gender employment gap (World Economic Forum, Citation2021) as well as a high level of inegalitarian gender beliefs (Roberts & Kwon, Citation2021). Egypt, like other MENA countries, is experiencing the MENA paradox (Friedrich et al., Citation2021): despite a growing number of educated and trained women, female employment representation is disappointingly low (Barsoum, Citation2019; World Bank, Citation2013). The hospitality sector has a particularly poor representation of women. Women make up only 5.3% of employees, even though tourism is one of the pillars of the Egyptian economy (CAPMAS, Citation2021; World Tourism Organization, Citation2020). The lack of opportunities for women to advance has drawn criticism from researchers (e.g. Kattara, Citation2005) as well as policymakers and international organisations. According to Egypt’s “Vision 2030,” a notable reform has been made to raise female labour force participation to 35%. (Egypt 2030, 2030, 2030, Citation2016). The introduction of the “National Strategy for the Empowerment of Egyptian Women 2030” highlighted this goal (National Council for Women, Citation2017). Egypt is the first nation to adopt the “Gender Equality Seal” in hospitality and tourism, thanks to a collaboration with the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) (Egypt Independent, Citation2019). Egypt’s “Tourism Reform Program” was started by the Ministry of Tourism to increase female participation (Al-Mashat, Citation2018).

It is not yet clear how managers will react to these policy changes, or whether they will align with their views on female hiring. Even the most willing organisations can have difficulty implementing new policies if they contradict the myths of their institutional environment. In their research on the Arab middle east, Karam and Jamali (Citation2013) demonstrate how firms struggle to launch new corporate social responsibility initiatives to increase female employment. Despite significant pressures from actors and customers outside of the middle east, firms’ ability to act was limited by their fear of backlash from the local public and political entities, who held very different views about the role of women. The researchers concluded that the only way to overcome this barrier was through persuasion. That is to say, by tactfully working with local entities to promote female empowerment, while respectfully addressing inconsistencies or incompatibilities in social discourses about women and the economy. Accordingly, it may be that the Egyptian government’s policies to increase female participation in tourism employment may be ineffective, especially if local firms feel that the policies are based on beliefs about women that are foreign to their own environment or beliefs.

Study 1: qualitative investigation of female-hiring beliefs at the operational level

This study aims to identify salient female-hiring beliefs currently held by managers in Egyptian hotels. We followed an exploratory research design (Denzin et al., Citation2008) drawing on interviews with managers who had experience and authority over hiring employees. The goals were to identify the advantages and disadvantages of hiring female employees, and the conditions that make it easy or difficult. Accordingly, the following research questions (RQ) are addressed:

RQ1: What behavioural beliefs do Egyptian hotel managers maintain about female hiring?

RQ2: What normative beliefs do Egyptian hotel managers maintain about female hiring?

RQ3: What control beliefs do Egyptian hotel managers maintain about female hiring?

Sample and data collection

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 32 managers between August and December 2018. All participants were key hiring decision-makers, including heads of departments (e.g. HR, front office, F&B) working in major Egyptian destinations (e.g. Cairo, Alexandria, Sharm Elsheikh). Both convenience and snowball sampling techniques were applied. Potential participants were contacted via email and on social media platforms (i.e. LinkedIn and Facebook). An invitation was sent to explain the study’s purpose. The interview questions were developed based on the work of Fishbein and Ajzen (Citation2010) in English, and then, translated into Arabic (Appendix A). Interviews lasted for 45 min on average. Data saturation was a threshold for stopping the interviews when no new information was added (Boddy, Citation2016).

Analysis

The outcomes of the interviews were analysed using content analysis. Following Fishbein and Ajzen (Citation2010), data were systematically coded to identify broad categories. Similar answers were grouped as a common belief (Fraser et al., Citation2010). Then, the frequency of each item in the data was calculated. The 20% frequency was used as a threshold (i.e. the belief must be repeated by at least 20% of the sample). Fishbein and Ajzen (Citation2010, p. 103) recommend this practise under “how many of the identified beliefs to include in the modal set.” This 20% also accounted for more than 75% of all responses received from respondents, indicating that the analysis captured most of their comments. To ensure validity, two authors worked independently to group similar codes and label the broader modal beliefs. Then, the outcomes were compared, showing a high degree of convergence. Disagreements were resolved through discussion among authors.

Findings

summarises the common female-hiring beliefs. Six behavioural beliefs were salient. The top three positive beliefs are “engagement with female guests,” followed by “provide a good image” and “create a diversified workforce.” The top three negative beliefs are that female employees “face work-life imbalance,” followed by “cannot work under pressure” and “cannot work night shifts.” Regarding normative beliefs, the most important reference group are “colleagues” and “GM/top management,” respectively. The findings reveal five salient control beliefs: “poor working conditions,” which ranks as the strongest barrier to hiring women, followed by “high family responsibilities” and “lack of qualified female workers.” The facilitating conditions, however, included the availability of a “suitable vacancy” and “management support.”

Table 1. Common female-hiring beliefs (N = 32).

Other interesting (but not salient) beliefs mentioned by managers were related to “societal traditions and norms,” and “hijab restrictions.” Despite not being salient (they do not meet the 20% frequency), these beliefs are important and reflect the societal issues that could also hinder increasing female participation in the tourism workforce. (In Study 3, we further analyse these.) Notably, although managers were asked about the advantages of hiring female employees, they compared them with males in many instances. For example, “female employees are more organised than males” and “female employees are more demanding than males.” Managers also discussed beliefs about their specific departments (e.g. “In my department [food and beverage], hiring females has many advantages compared to males […]”). Interestingly, many managers cited that some jobs are more suitable for women than others (e.g. kitchen for men and public relations for women).

Overall, study 1 pinpoints 13 female-hiring beliefs (both positive and negative) that can inform hiring decisions. While positive beliefs can support the ongoing policy efforts to increase female participation. Negative beliefs may attenuate policy acceptance by managers. Industry-related beliefs (e.g. “poor working conditions”) are used as an excuse to discriminate as well. The next step is to uncover the relations between these identified beliefs and managers’ attitude, social pressures and PBC over female hiring.

Study 2: relationships between female-hiring beliefs and intentions

The behavioural, normative and control beliefs that underpin female hiring discrimination in the Egyptian hospitality industry were identified in study 1. Based on the literature in section 2.1, this study argues that these beliefs will influence managers’ attitudes and perceptions about women in the workplace, and, as a result, inform managers’ intentions to increase female hiring. For example, if managers believe that “female employees work less hard than male counterparts,” then their attitude towards hiring women will be negative, and they will have a lower intention to hire women (Coffman et al., Citation2021). Yet, while hiring decisions are made by individual managers, these decisions are governed by standards and regulations. Therefore, based on the literature in section 2.2, this study posits that, as coercive pressures, national policies on female hiring will influence managers’ intentions to hire more women. Accordingly, the model depicted in has been developed for this study, and the following hypotheses have been formulated:

H1: Behavioural female-hiring beliefs are significantly and positively related to managers’ attitudes towards hiring more female employees.

H2: Normative female-hiring beliefs are significantly and positively related to managers’ subjective norms to hire more female employees.

H3: Female-hiring control beliefs are significantly and positively related to managers’ perceived control over female hiring.

H4: Managers’ attitudes and intentions to hire more female employees are significantly and positively related.

H5: Managers’ subjective norms and intentions to hire more female employees are significantly and positively related.

H6: Managers’ perceived control and intentions to hire more female employees are significantly and positively related.

H7: Perceived policy pressures and managers’ intentions to hire more female employees are significantly and positively related.

Methods

Data collection

An online questionnaire, created and distributed using Google Forms, was used to collect data between January and March 2019. The questionnaire started with filter questions (e.g. “I participate in hiring employees in my department (yes/no)”) followed by four main sections: (1) behavioural, normative, and control beliefs over female hiring, (2) attitude, subjective norm, PBC and perceived policy pressure to hire female employees, (3) female-hiring intentions and (4) the respondent profile. The questionnaire avoided using any headings and items were ordered randomly.

This study applied convenience sampling due to the lack of a predefined list of contacts for managers working in the Egyptian hotel industry. Thus, the questionnaire was distributed in three ways. First, the authors used the Egyptian Hotel Guide and sent invitation emails to a list of hotels registered in the guide. Second, using the hotels’ websites, the authors extracted emails from contact details and sent an invitation email to those hotels. Last, to increase sample size and representation, the authors used personal connections on social media (i.e. LinkedIn, and Facebook) to identify potential respondents. In all cases, the cover letter explained the purpose of the study, assured confidentiality and asked people to participate by filling out the survey or forwarding it to others. Two reminders were sent, after two weeks and then again after another week.

In total, more than 1000 invitations were sent and 259 responses were received. To be included, respondents needed to have hiring power in their hotels in Egypt. After screening against this criterion, 200 responses were retained for further analysis. This criterion is relevant to ensure that respondents participate in recruiting, interviewing and hiring decisions. The respondents are, therefore, close to the operation and are better positioned to assess its needs and working conditions, and reflect on future orientation. The adequacy of the sample size was supported by running the post-hoc power analysis. Post-hoc Statistical Power for the sample size of 200 observed R2 ranging from .649 to .961, and a probability level of .05 resulted in the statistical power of 1, substantially above Cohen’s Cohen (Citation1988) recommendations, justifying the adequacy of the sample.

Measures

Measures for the 8 construct-model () were built based on validated scales from existing literature and outcomes from study 1. Appendix B provides a full list of the questionnaire items and scales.

Beliefs

For behavioural beliefs, 12 items were used to measure the strength of each belief and its outcome evaluation. The final scores for behavioural beliefs were obtained following the expectancy-value model (Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation2010), in which the strength of each belief, is multiplied by its outcome evaluation. For example, for each behavioural belief, the belief strength score on a 7-point scale (1= likely, 7 = unlikely) is multiplied by the relevant outcome evaluation score on a −3 to +3 scale (-3 = extremely bad, +3 = extremely good). This is expressed by the following equation: behavioural belief score = (BB1 x OE1). Where BB1 refers to behavioural belief 1 and OE1 reflects its outcome evaluation. Similarly, normative beliefs were measured with four items, two for reference groups and two for motivation to comply. For control beliefs, eight items were used to measure the strength and power of each belief. The same expectancy-value model is used to calculate the scores of normative and control beliefs (Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation2010).

Direct predictors

Manager attitude was measured using 5 items on a 7-point bipolar scale (Ajzen, Citation2002), while subjective norms (6 items), and PBC (4 items) were measured using a 7-point Likert-type scale (Ajzen, Citation2002). Perceived coercive pressure was measured using a 7-point Likert scale by asking participants about the extent to which they feel pressured to hire women, considering hotel and country policies. The subjective nature of this variable is consistent with other predictors and the study’s focus on manager-perceived pressure to hire more female employees.

Outcome variable

Female-hiring intention was measured using three items (Ajzen, Citation2002) and defined in terms of the target (hiring), action (more women), context (department) and time (forthcoming months).

Control variables

This study included control variables at both the firm and the individual levels. First, firm size can influence hiring discrimination behaviour (Fraser et al., Citation2011), thus firm size was controlled and measured using the number of guest rooms. Second, hotel classification was controlled for, as the hotel category can play a role in shaping hiring routines (Pinar et al., Citation2011). On the individual level, this study accounts for same-gender preference measured as a dummy with 1 for female respondents and 0 otherwise. As men with higher education are likely to hold more gender-equitable attitudes (El Feki et al., Citation2017), we control for education level. Finally, as Marlowe et al. (Citation1996) found that hiring biases decrease when experience increases, this study accounts for managers’ years of experience.Footnote1

Data screening

Screening tests were conducted to check for skewness and kurtosis and multicollinearity. The skewness and kurtosis values were far below the threshold of ±2 and ±7 respectively, confirming an acceptable distribution of the data (Hair et al., Citation2019). The multicollinearity test result also indicates that the variance inflation factor of each independent variable is below-accepted thresholds (O’brien, Citation2007).

Common method bias

First, the survey items appeared under general sections rather than being grouped by construct, preventing respondents from identifying items capturing a particular construct or guessing hypothesised links. The survey also clearly stated that there were no right or wrong answers. Second, Harman’s one-factor test was employed, and the findings revealed that no single factor accounted for more than 40% of the variance. This indicates that common method bias is not a threat (Podsakoff & Organ, Citation1986).

Social desirability bias

Due to the sensitivity of the topic, the authors took precautions to limit the possibility of social desirability bias (Krumpal, Citation2013). These precautions included confirming the anonymity of responses, avoiding direct questions on the consequences of hiring or not hiring female employees, and using neutral language to avoid negative or positive cues. In addition, this paper applied mixed methods across studies, which can mitigate this issue.

Statistical analysis

The analysis was carried out using the AMOS 24 program. First, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to assess the reliability and validity of the variables. Factor loadings, Cronbach’s alpha, average variance extracted (AVE), composite reliability (CR) and inner construct correlations were used to ensure the adequacy of the measurement model. Second, a structural model was assessed to test the hypotheses (Anderson & Gerbing, Citation1988).

Results

Descriptive statistics

The respondents (200 in total) have various levels of experience, distributed as 10 years or less (23.5%), 11–15 years (22%) and above 15 years of experience (54.5%). Most respondents (68%) hold a university degree, followed by high studies (14.5%), diplomas (10.5%) or high school (5%). Respondents work in small (3%), medium (60.5%), and large hotels (36.5%), with less than 100 rooms, 100–500 rooms, and more than 500 rooms respectively. Most respondents work in 5-star hotels (86.5%) and 4-star hotels (13.5%). Female respondents were the minority at 12%, while most respondents (88%) were male. This unbalanced gender representation is not surprising as women are less represented in managerial positions.

The respondents showed above-average intentions to hire female employees (M = 5.03, SD= 1.67), positive attitude (M = 5.61, SD= 1.34) and favourable subjective norms to hire female employees (M = 5.32, SD= 1.26). They also perceived moderate policy pressure (M = 4.08, SD= 1.77) and high PBC (M = 5.75, SD= 1.29). In terms of beliefs, the average overall behavioural, normative and control beliefs were moderately positive (see ).

Table 2. Means, standard deviations for study variables.

Effects of individual beliefs

This section further examines the role of beliefs to gain a better understanding of the links between individual beliefs (i.e. expectancy-value scores) in each set (i.e. behavioural, normative and control), and their corresponding variable (i.e. attitude, subjective norms and PBC, respectively).

Overall, behavioural beliefs explain 82% of the variance in attitude towards female hiring. In the context of the study, the relationships between attitude and the six behavioural beliefs (i.e. 6 expectancy-value scores) show that certain beliefs are more important than others. Specifically, four out of six beliefs were statistically significant (see Appendix C). First, “engagement with female guests” contributes positively to managers’ attitudes towards hiring women. This means that managers expect that female guests will feel more at ease when interacting with female employees, which leads to higher engagement. This also adheres to the belief system that favours gender segregation (Hutchings et al., Citation2020). Second, through “providing a good image,” managers expect that hiring female employees for certain jobs, such as reception, guest relations, and food and beverage, contributes to improving the hotel’s image, which will attract a broader range of customers. This resonates with the notion that managers may hire females for achieving specific operational benefits and certain vacancies (Pinar et al., Citation2011). Third, managers also expect that hiring female employees contributes to “creating a diversified workforce,” which is beneficial for the hotel’s competitiveness and innovation. However, fourth, “facing work-life imbalance,” as described by managers, implies that female employees face difficulties balancing work and family responsibilities, which negatively affects their decisions to hire females.

On normative grounds, colleagues and senior management explain 94% of the variance in subjective norms. These beliefs had statistically significant effects, suggesting that managers believe their senior management and colleagues expect them to hire female employees. This strong impact highlights the important role of social pressures in hiring contexts, where managers seek approval for their decisions (McDonnall & Lund, Citation2020).

Four control beliefs, which explain 65% of the variance in PBC, were also statistically significant. These are management support, poor working conditions, family responsibilities and availability of qualified female workers. This finding supports the prevalent finding of Study 1, in which managers pointed to external factors that prohibit them from hiring more female employees. Managers in remote tourist destinations, for example, are unable to employ women due to a lack of qualified applicants.

Measurement model

Using CFA, the initial model showed an acceptable fit to the data. However, one survey item from the PBC (i.e. Item 4) variable exhibited low factor loading. As such, we decided to remove it. After rerunning the CFA, the model showed a better fit to the data (χ2 = 210.585, df = 139, χ2/df = 1.515; CFI = 0.980; TLI = 0.975; RMSEA = 0.052; PCLOSE =.445). This means that the proposed theoretical model appears to adequately explain the relationships between the observed variables. The qualities of the measurement model are summarised in and .

Table 3. Reliability and validity indices.

Table 4. The square root of the AVE and inter-construct correlations.

First, shows that all latent variables have Cronbach’s alpha and CR values higher than the threshold of .7, confirming the reliability of the measures (Hair et al., Citation2019). This means that the measures used to assess the latent variables are consistently related to each other, indicating that they are measuring the same construct. Second, convergent validity was assessed using AVE values, which were higher than .5 for all variables. In addition, factor loadings were higher than .6 (Hair et al., Citation2019). This means that the measures used in the study to assess each latent variable are measuring the same construct and that each indicator has a strong relationship with its corresponding latent variable. Third, discriminant validity was assessed by comparing the square root of the AVE for each variable with its correlation with other variables (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). shows the AVE values and provides evidence for discriminant validity. This suggests that each variable has good discriminant validity because it is more strongly related to its own indicators than to other variables in the model.

Structural model results

A structural model was assessed to examine the proposed hypotheses. The model showed a good fit with the data (χ2 = 668.149, df = 414, χ2/df = 1.614; CFI = 0.946; TLI = 0.939; RMSEA = 0.056; PCLOSE=.119). Path coefficients (β), T-values, P-values, and R2 were used to assess the model and hypotheses. The structural model results are shown in .

Table 5. Path coefficients (β) and hypotheses testing.

The results show that behavioural beliefs have a significant and positive relationship with attitude towards hiring female employees (β = 0.905, t = 10.014, p<.001). Thus, H1 is supported. Similarly, normative beliefs are significantly and positively related to managers’ subjective norms (β = 0. 971, t = 9.842, p<.001). Thus, H2 is supported. Control beliefs have a significant positive link with PBC over female hiring (β = 0.804, t = 4.948, p<.05), thus H3 is supported. The results also show that female-hiring intentions are a positive function of managers’ attitudes (β = 0. 298, t = 3.337, p<.001), subjective norms (β = 0.244, t = 2.421, p<.001), PBC (β = 0.240, t = 2.979, p<.01) and perceived policy pressures (β = 0.211, t = 3.337, p<.05). Thus, H4–H7 are supported.

Study 3: potential conflicts between managers’ beliefs and policy reforms

The third study complements the first two studies. Study 1 identified 13 positive and negative female-hiring beliefs that may influence managers’ intentions to hire female employees. In the second study, the results showed that these beliefs inform managers’ attitudes, subjective norms and PBC over female hiring. Due to the significance of managers’ beliefs in hiring female employees, the purpose of study 3 is to reveal potential conflicts, if any, between policy and beliefs held by managers at the operational level. We used semi-structured interviews with practitioners and academics (Galletta, Citation2013). Participants were encouraged to share their thoughts on female hiring, considering both managers’ beliefs (study 1) and the specific policy of increasing female participation to 35%.

Sample and data collection

Using convenience sampling, 20 semi-structured individual interviews were conducted (Galletta, Citation2013), both face-to-face and remotely (by phone) when preferred by the participants due to COVID-19. Interviews lasted 25 min on average. An interview guide was prepared (see Appendix D) to ensure consistent and systematic execution of the interviews (Patton, Citation2015). The fourth author ran the interviews in September 2021 until theoretical saturation was reached (Boddy, Citation2016). The final sample included 10 academics and 10 practitioners, consisting of 4 male and 6 female employees. (Appendix D) presents the characteristics of the interviewees.

Analysis

All interviews were recorded and transcribed, then analysed using thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). Two authors independently coded the data (O’Connor & Joffe, Citation2020). To discover emerging themes, authors started by reading the data (step 1), analysing the text to identify initial codes (step 2), summarising the codes into broader themes (step 3), reviewing the outcomes with a third author to resolve discrepancies (step 4), discussing the thematic structure among authors and refining final themes (step 5), and writing the results and including supporting comments (step 6).

Findings

The findings show that the interviewees hold different views on the effectiveness of policy reforms in boosting female participation in hospitality. As illustrated by the following quotes, some interviewees considered the policy approach to be effective for gender equality, while others explained that achieving this goal is challenging, because it requires hotels to change long-held beliefs and standards.

I believe the policy approach is the most effective way to increase women’s participation […], especially in hotels that must focus on the candidate’s quality rather than gender (Interviewee10, female, academic).

These policies cannot force hotels to increase the percentage of women. Working in hotels is hard, both physically and mentally […] and hotels can employ more women in certain departments, such as guest relations, but not kitchen or security (Interviewee 6, male, practitioner).

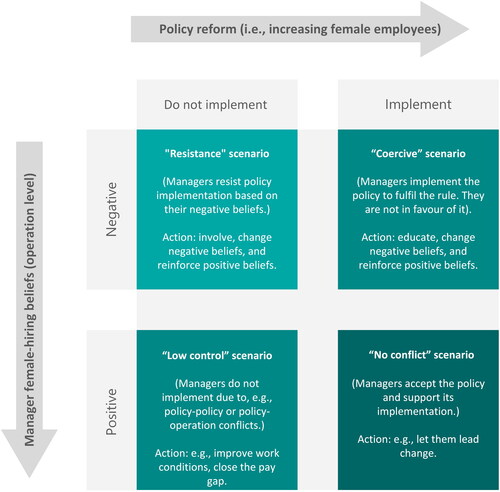

Almost all participants agreed that positive beliefs about female employees can complement and facilitate policy acceptance. Yet, managers’ beliefs are not fully in line with the ongoing policy reforms, and negative female-hiring beliefs will make it difficult to increase female participation, leading to potential conflicts. As summarised in , four themes emerged from the data.

Table 6. Potential conflicts and remedies.

First, female-hiring beliefs were seen by interviewees as a source of conflict. That is, the process of increasing female participation in hotels is confronted with many negative beliefs about women in general, and, particularly in hospitality, which requires nightwork and other challenging work.

The concept of gender equality could be disturbing for many, especially those who believe that a woman do not have what it takes […] to manage a situation or a crisis as good as a man’ (Interviewee 2, female, academic).

I prefer hiring males. I would say 80% males and 20% female employees for the front office and housekeeping […] because males have higher physical power (Interviewee 3, male, practitioner).

Second, interviewees revealed that working conditions could attenuate policy acceptance. Also, pushing hotels to increase female participation may cause operational problems, according to some managers, and the lack of qualified female employees would make it even more difficult.

Hotels are looking for work stability […] female employees could leave the job due to poor working conditions, long working hours. (Interviewee 4, male, practitioner)

This policy can be applied in government jobs […]. In hotels, managers will continue hiring those they believe are more suitable (Interviewee 3, male, practitioner)

Third, still perceiving working in hotels as “shameful” and considering women only as wives and mothers makes it difficult to convince fathers and husbands to join or continue working in hospitality.

Society traditions prevent females from continuing their career […] many females quit hotels after marriage because they have to’ (Interviewee 4, female, academic).

Although working night shifts in a hospital seems to be an honourable job, telling your family that you have a night shift in a hotel is shameful (Interviewee 10, female, academic).

Fourth, interviewees highlighted that some hotel policies are not in line with the ongoing reforms. For example, most hotels do not accept hijab, which is worn by most women in Egypt. This hotel policy may create a compromise for females who need to choose between keeping their hijab or getting a job. Wage inequalities also continue to make hospitality employment unattractive to females.

Hijab is not allowed here […]. In the last 10 years, I met many candidates wearing hijabs. The hotel policy forces me to dismiss them. […] some candidates said they are willing to remove their hijab while working and wear it after work. This does not seem fair (Interviewee 3, male, practitioner).

I have been working here, (hotel name), for three years […]. But when a new employee arrived, he got a higher salary despite me having more years of experience than him […]. That is all because I am a female! (Interviewee 8, female, practitioner).

In summary, four conflicts could arise between increasing female participation and managers’ current beliefs about female employees, working conditions, society and the industry. It could be concluded that managers who maintain negative beliefs about women are less likely to accept gender equality policies.

Discussion and implications

We followed a mixed-method design across three studies and (1) identified the most common female-hiring beliefs held by hotel managers at the operational level, (2) examined how these beliefs relate to female-hiring attitudes, subjective norms, PBC and intentions, and (3) investigated the role of policy pressures and pinpointed four potential policy/belief conflicts.

The results from Study 1 show both positive and negative female-hiring beliefs. Many stereotypical perceptions were salient among managers. Interestingly, managers’ beliefs seem to reflect an instrumental approach to equality—that is, managers hire females for certain benefits rather than because of an organisational commitment to equality. Although this business case for gender equality is imperative, other important drivers, such as social integration, wellbeing, justice and moral views, are still relegated to a negligible role (Warren et al., Citation2019). This approach can trigger contradictions between policy and practice (Kele & Cassell, Citation2023). The results also show that managers tend to discriminate against women based on poor working conditions in hospitality, which are less attractive to female employees (Santero-Sanchez et al., Citation2015). To hire more female employees, managers need management support and suitable vacancies, as female employees are considered appropriate for specific jobs. This is consistent with the patterns of employment ghettos phenomenon: some departments are filled by men and others by women (Pinar et al., Citation2011). This result also agrees with that of Coffman et al. (Citation2021), where managers prefer to hire males over female employees for male-typed tasks. Overall, our results pinpoint key female-hiring beliefs that can be used to design effective behavioural change interventions (Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation2010).

Study 2 builds on the findings of the first study and demonstrates that managers’ behavioural, normative, and control beliefs are positively related to their attitudes, subjective norms and PBC over female hiring, respectively. That is, the more a manager believes that female employees bring benefits to their department, the more positive their attitude towards hiring women. Likewise, the more a manager believes that colleagues and top management are in favour of hiring female employees, and the working conditions are supportive, the stronger their subjective norms and perceptions of control over female hiring. These results underline the role of managers’ beliefs in increasing female participation. The results also show that attitude is the strongest predictor of intention to hire more female employees, followed by subjective norms and PBC. These results complement previous studies in other contexts (e.g. Lettieri et al., Citation2021; McDonnall & Lund, Citation2020). In addition, managers’ perceived policy pressures contribute significantly to their female-hiring intentions, over and above attitudes, subjective norms and PBC. This finding reinforces the role of institutional pressures on managers’ decisions in female-hiring contexts (Horvath & Ryan, Citation2003; Rigolini & Huse, Citation2021).

Study 3 highlights that although hotels are pushed to increase female participation, hiring more female employees is not necessarily favoured by managers. This third study investigates female-hiring beliefs and attitudes from studies 1 and 2 concerning policy reforms. The findings show four potential conflicts, which are not mutually exclusive. First, a policy-belief conflict that arises when hiring more female employees is faced with negative gender beliefs. For example, a manager believes female employees work less hard than men, but may hire them to follow the policy. Second, a policy-operation conflict appears when managers perceive that their working conditions are not suitable for female employees. In this situation, even if managers hold positive beliefs about female employees, they face difficulties hiring more or can discriminate based on these conditions. Third, a policy-society conflict that arises when working in hotels is perceived as shameful and could prevent female employees from pursuing hospitality careers. Finally, a policy-policy conflict appears when hiring more female employees as a national policy is faced with discouraging hotel policies (e.g. Hijab is not allowed). This conflict can attenuate gender equality, especially in a community where the majority of women wear the hijab. These results add to the complexity of the MENA paradox (Friedrich et al., Citation2021), where policy-based interventions alone are not enough to make a difference in increasing women’s employment at the operational level.

Theoretical contributions

The results contribute to the literature in three ways. First, previous applications of the TPB tend to focus on the direct predictors of (hiring) intentions, while ignoring the role of beliefs (Elhoushy & El-Said, Citation2020). This study’s results demonstrate strong and significant relationships between managers’ behavioural, normative and control beliefs, and their attitudes, subjective norms and perceived control over hiring female employees, respectively. As such, this study validates the commonly disregarded propositions of Ajzen’s theory (1991; 2015) and concludes that managers’ hiring beliefs regarding women can have a substantial impact on the progress, or lack thereof, of gender equality efforts. The study’s results indicate that, as shown in , both positive and negative beliefs held by managers can be used to design effective behaviour-change interventions aimed at promoting gender equality in the workplace. A possible behaviour change intervention to address the belief that females are perceived as less hardworking than males by hotel managers could be to provide evidence-based information that challenges the accuracy of this belief. This could include highlighting successful female leaders and their accomplishments in the industry.

Second, this study examined managers’ perceived pressures to hire female employees at various levels. At the personal level, the results position manager attitude as the most important predictor of female hiring in hospitality. At the social level, the results show that subjective norms are the second most important driver of intentions. At the contextual level, the results show that control beliefs are associated with significant variations in hiring intentions. At the policy level, which considers pressures from government regulations and industry policies, this study uniquely reveals a significant link between perceived policy pressures and managers’ intentions to hire more female employees. This multilevel consideration is in line with that of Cooper et al. (Citation2021), who show that gender inequalities are embedded at the individual, organisational and market levels. The results also support the extended TPB model, which includes elements of the institutional theory (Ajzen, Citation1991; DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1983).

Third, a significant contribution of this study is the identification and distinction of four conflicts between policy-level reforms and manager beliefs. When policy reforms are met with negative beliefs, policy implementation by managers at the operational level may suffer. Our findings highlight both the challenges and solutions to increasing female participation in the hospitality industry, where managers still have the upper hand. depicts and explains the intersections between manager beliefs (positive vs. negative) and policy implementation (implement vs. do not implement).

Managerial and policy implications

This study provides potential remedies for addressing various conflicts, as highlighted in . Although it may be difficult to cover this matter fully within the scope of this paper, a multilevel approach that considers policy, societal norms and operational practises is critical to avoid conflicts. For example, promoting equal opportunities for employment for women in the tourism and hospitality industries necessitates addressing the cultural conflict regarding the hijab. To accomplish this, policies allowing the wearing of the hijab should be implemented, societal attitudes towards working in these sectors should be improved and inclusive work environments that embrace diversity should be created.

The results offer insights to policymakers to address the conflicts caused by female-hiring beliefs. As suggests, different actions are needed based on each scenario. In the first “resistance scenario,” managers hold negative beliefs and resist hiring more female employees. Those managers should be involved in the decision and policy-making process. Focusing on managers’ attitudes is a priority, as this factor had the strongest relationship with hiring intention. Thus, interventions should focus on changing negative and cultivating positive gender beliefs and identities (Warren et al., Citation2019).

In the second “low control scenario,” managers hold positive beliefs about female employees, but they do not hire more female employees due to perceived (contextual) difficulties. Strengthening managers’ perceived control over such difficulties is critical, as this factor is significantly related to hiring more female employees. The government should cooperate with hospitality enterprises and assist female hospitality workers in fostering workplace conditions that facilitate female hiring. For example, policymakers could establish training and mentorship programs to increase the pool of qualified female employees. Tourism and hospitality firms need to provide transparent schemes that ensure equal payment and promotion opportunities. Employment contracts that consider family responsibilities and ensure the work-life balance are key steps forward. Importantly, changes in hotel policies are needed to ensure that a female candidate is not rejected based on religious discrimination (e.g. hijab). While it is understandable that hotels use uniforms and dress codes to reflect the brand, in a country like Egypt, accommodating cultural aspects is a key step towards gender equality.

In the third “coercive scenario,” managers hold negative beliefs but still show a willingness to hire more female employees. Although this might seem to be on the right track towards increasing female participation, its long-term effectiveness (i.e. retaining talent) is questionable. Thus, policymakers should cultivate positive beliefs about female employees and alter negative ones. For example, policymakers could establish an association of “Gender Equality Ambassadors” with representatives from different firms, considering “men as champions” (Warren et al., Citation2019). This association can lead to change by disseminating positive beliefs, interviewing female workers, documenting their experiences and day-to-day routines, and emphasising their achievements. This can also contribute to altering the poor image related to working in hotels.

The last, the “no conflict” scenario, represents an optimal context for equality. Managers with positive beliefs should be empowered to lead change. Campaigns that feature hospitality leaders discussing the contribution of both men and women to the workforce could be broadcast on national television and social media.

Limitations and further research

The generalisation of our empirical results is influenced by two limitations. First, data were collected from a single country that ranks low on the Gender Equality Index. Thus, the findings should be understood in the context of countries with similar challenges. Second, data were collected from a single informant in each firm. Thus, research employing multi-informant designs or direct observation would be useful to extend the results.

Although study 3 collected data during the COVID-19 pandemic, no potential effects of the pandemic were considered. Similarly, no data were collected on the number of female employees in each department. Thus, future studies could examine departmental effects and investigate manager beliefs from both cultural and department-based views. Researchers could take a longitudinal approach or use panel data to examine the impact of policy reforms over time. Future studies could also build upon the potential remedies for the four conflicts identified in this study, with researchers employing qualitative methods to co-create and experiment with context-specific solutions in consultation with relevant stakeholders.

Conclusion

This study employs a mixed-methods approach to identify common female-hiring beliefs and to demonstrate the relationships between managers’ beliefs and female hiring. The findings highlight the importance of managers’ attitudes in increasing female labour-force participation. However, the role of policies is arguable, and various conflicts can arise between policy-level reforms and operational-level beliefs. This study advances the discussion by highlighting specific belief/policy conflicts and proposing scenario-based solutions. The findings provide a foundation for future research and serve as a benchmark against which future results from other countries and industries can be compared.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (40.6 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Journal Editor, Prof. Xavier Font, as well as the reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sayed Elhoushy

Sayed Elhoushy, Ph.D. is a Lecturer in Marketing at Queen Mary University of London, UK. His research interests include sustainability marketing and consumer behavior. Sayed’s research papers are published in high-quality journals. He had research experience as a visiting research fellow at SHTM, University of Surrey, UK, and FEP, University of Porto, Portugal.

Osman Ahmed El-Said

Osman Ahmed El-Said earned a Bachelor of Science in Tourism and Hospitality in 2002, a Master of Science in Service Quality Management in 2008, and a PhD in Innovation Management in 2011. He published several research articles in a variety of fields, including human resources, marketing, innovation management, CSR and Entrepreneurship.

Michael Smith

Michael Smith graduated from the German University of Technology in Oman in 2020 with a Bachelor of Science in International Business and Service Management. He has since been employed in the tourism industry, collaborated in a government funded research project, and co-authored several publications in the fields of hospitality and corporate social responsibility.

Hesham Mohamed Dar

Hesham Mohamed Dar got a Bachelor of Hospitality Management in 2011, Master’s degree in Human Resources Management in 2015 researching the negative effects of workplace bullying among Egyptian hotel employees. And got the PhD in Maritime Hospitality in 2021 researching the hospitality services that are introduced to offshore vessel employees during their stay onboard. He has a record of research articles in Human Resources, Maritime Hospitality and Sustainability in Human Resources

Notes

1 Notably, in this study, all control variables have a non-significant relationship with intention, except for manager experience (β = 0.152, t = 3.510, p<.001).

References

- Ajzen, I. (2002). Constructing a TPB questionnaire: Conceptual and methodological considerations. Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/0574/b20bd58130dd5a961f1a2db10fd1fcbae95d.pdf?_ga=2.32273206.949905743.1582934700-299135995.1582934700.

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behaviour. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Ajzen, I., & Cote, N. G. (2010). Attitudes and the prediction of behavior. In W. D. Crano, & R. Prislin (Eds.), Attitudes and attitude change (pp. 289–311). Psychology Press.

- Alarcón, D. M., & Cole, S. (2019). No sustainability for tourism without gender equality. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(7), 903–919. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1588283

- Alberti, G., & Iannuzzi, F. E. (2020). Embodied intersectionality and the intersectional management of hotel labour: The everyday experiences of social differentiation in customer‐oriented work. Gender, Work & Organization, 27(6), 1165–1180. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12454

- Al-Mashat, R. (2018, November). Egypt-tourism reform program. Retrieved from Egyptian Tourism Authority: http://egypt.travel/media/2338/egypt-tourism-reform-program.pdf

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

- Ang, M. C., Ramayah, T., & Amin, H. (2015). A theory of planned behavior perspective on hiring Malaysians with disabilities. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 34(3), 186–200. https://doi.org/10.1108/EDI-02-2014-0012

- Barsoum, G. (2019). ‘Women, work and family’: Educated women’s employment decisions and social policies in Egypt. Gender, Work & Organization, 26(7), 895–914. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12285

- Bobbit-Zeher, D. (2011). Gender discrimination at work: Connecting gender stereotypes, institutional policies, and gender composition of workplace. Gender & Society, 25(6), 764–786.

- Boddy, C. R. (2016). Sample size for qualitative research. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 19(4), 426–432. https://doi.org/10.1108/QMR-06-2016-0053

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Buengeler, C., Leroy, H., & De-Stobbeleir, K. (2018). How leaders shape the impact of HR’s diversity practices on employee inclusion. Human Resource Management Review, 28(3), 289–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2018.02.005

- Calinaud, V., Kokkranikal, J., & Gebbels, M. (2021). Career advancement for women in the British hospitality industry: The enabling factors. Work, Employment and Society, 35(4), 677–695. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017020967208

- CAPMAS. (2021). Annual - Egypt in figures - work 2021. Retrieved from Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics: https://www.capmas.gov.eg/Pages/Publications.aspx?page_id=5104&Year=23592

- Carvalho, I., Costa, C., Lykke, N., & Torres, A. (2019). Beyond the glass ceiling: Gendering tourism management. Annals of Tourism Research, 75, 79–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2018.12.022

- Coffman, K. B., Exley, C. L., & Niederle, M. (2021). The role of beliefs in driving gender discrimination. Management Science, 67(6), 3551–3569. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2020.3660

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. (2nd ed.). Lawrence Earlbaum Associates.

- Cooper, R., Mosseri, S., Vromen, A., Baird, M., Hill, E., & Probyn, E. (2021). Gender matters: A multilevel analysis of gender and voice at work. British Journal of Management, 32(3), 725–743. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12487

- Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage Publications.

- Dashper, K. (2020). Mentoring for gender equality: Supporting female leaders in the hospitality industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 88, 102397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.102397

- Denzin, N. K., Lincoln, Y. S., & Smith, L. T. (Eds.) (2008). Handbook of critical and indigenous methodologies.

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095101

- Eger, C., Fetzer, T., Peck, J., & Alodayni, S. (2022). Organizational, economic or cultural? Firm-side barriers to employing women in Saudi Arabia. World Development, 160, 106058. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2022.106058

- Eger, C., Munar, A. M., & Hsu, C. (2022). Gender and tourism sustainability. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(7), 1459–1475. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1963975

- Egypt 2030. (2016). 2030 vision of Egypt. Retrieved from Egypt 2030: https://egypt2030.gov.eg/?lang=en

- Egypt Independent. (2019, May 30). Egypt becomes the world’s first country to adopt UNDP’s ‘Gender Equality Seal’. Retrieved from Egypt Independent: https://egyptindependent.com/egypt-becomes-the-worlds-first-country-to-adopt-undps-gender-equality-seal/

- El Feki, S., Heilman, B., & Barker, G. (2017). Understanding masculinities: Results from the international men and gender equality survey (IMAGES)-Middle East and North Africa. Cairo and UN Women and Promundo-US.

- Elhoushy, S., & El-Said, O. A. (2020). Hotel managers’ intentions towards female hiring: An application to the theory of planned behaviour. Tourism Management Perspectives, 36, 100741. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2020.100741

- Ferguson, L., & Alarcon, D. M. (2015). Gender and sustainable tourism: Reflections on theory and practice. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 23(3), 401–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2014.957208

- Figueroa-Domecq, C., Kimbu, A., de Jong, A., & Williams, A. M. (2022). Sustainability through the tourism entrepreneurship journey: A gender perspective. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(7), 1562–1585. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1831001

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (2010). Predicting and changing behavior: The reasoned action Taylor & Francis Group. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/gmulebooks/detail.action?docID=66850. Created from gmul-ebooks on 2023-03-25 11:32:23.

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Fraser, R., Ajzen, I., Johnson, K., Hebert, J., & Chan, F. (2011). Understanding employers’ hiring intention in relation to qualified workers with disabilities. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 35(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3233/JVR-2011-0548

- Fraser, R., Johnson, K., Hebert, J., Ajzen, I., Copeland, J., Brown, P., & Chan, F. (2010). Understanding employers’ hiring intentions in relation to qualified workers with disabilities: Preliminary findings. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 20(4), 420–426. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-009-9220-1

- Friedrich, C., Engelhardt, H., & Schulz, F. (2021). Women’s agency in Egypt, Jordan, and Tunisia: The role of parenthood and education. Population Research and Policy Review, 40(5), 1025–1059. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-020-09622-7

- Galletta, A. (2013). Mastering the semi-structured interview and beyond: From research design to analysis and publication. (Vol. 18). NYU Press.

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2019). Multivariate data analysis. (8th ed.). Cengage Learning EMEA.

- Harcourt, M., Lam, H., & Harcourt, S. (2005). Discriminatory practices in hiring: Institutional and rational economic perspectives. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 16(11), 2113–2132. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190500315125

- Horvath, M., & Ryan, A. M. (2003). Antecedents and potential moderators of the relationship between attitudes and hiring discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. Sex Roles, 48(3/4), 115–130. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022499121222

- Hutchings, K., Moyle, C-l., Chai, A., Garofano, N., & Moore, S. (2020). Segregation of women in tourism employment in the APEC region. Tourism Management Perspectives, 34, 100655. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2020.100655

- International Labour Organization. (2020). Country profiles: Egypt. Retrieved from ILOSTAT: https://ilostat.ilo.org/data/country-profiles/

- Jain, S., Singhal, S., Jain, N. K., & Bhaskar, K. (2020). Construction and demolition waste recycling: Investigating the role of theory of planned behavior, institutional pressures and environmental consciousness. Journal of Cleaner Production, 263, 121405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121405

- Karam, C. M., & Jamali, D. (2013). Gendering CSR in the Arab middle east: An institutional perspective. Business Ethics Quarterly, 23(1), 31–68. https://doi.org/10.5840/beq20132312

- Kato, K. (2019). Gender and sustainability–exploring ways of knowing–an ecohumanities perspective. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(7), 939–956. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1614189

- Kattara, H. (2005). Career challenges for female managers in Egyptian hotels. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 17(3), 238–251. https://doi.org/10.1108/09596110510591927

- Kele, J. E., & Cassell, C. M. (2023). The face of the firm: The impact of employer branding on diversity. British Journal of Management, 34(2), 692–708. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12608

- Kim, W. G., McGinley, S., Choi, H.-M., & Agmapisarn, C. (2020). Hotels’ environmental leadership and employees’ organizational citizenship behavior. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 87, 102375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.102375

- Krumpal, I. (2013). Determinants of social desirability bias in sensitive surveys: A literature review. Quality & Quantity, 47(4), 2025–2047. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-011-9640-9

- Labelle, R., Francoeur, C., & Lakhal, F. (2015). To regulate or not to regulate? Early evidence on the means used around the world to promote gender diversity in the boardroom. Gender, Work & Organization, 22(4), 339–363. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12091

- LaPan, C., Morais, D. B., Wallace, T., Barbieri, C., & Floyd, M. F. (2022). Gender, work, and tourism in the Guatemalan Highlands. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(12), 2839–2859. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1952418

- Latif, B., Mahmood, Z., Tze San, O., Mohd Said, R., & Bakhsh, A. (2020). Coercive, normative and mimetic pressures as drivers of environmental management accounting adoption. Sustainability, 12(11), 4506. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114506

- Lekchiri, S., & Eversole, B. A. (2021). Perceived work-life balance: Exploring theexperiences of professional Moroccan women. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 32(1), 35–53. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.21407

- Lettieri, A., Díez, E., & Soto-Pérez, F. (2021). Prejudice and work discrimination: Exploring the effects of employers’ work experience, contact and attitudes on the intention to hire people with mental illness. The Social Science Journal, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/03623319.2021.1954464

- Liu, H., Ke, W., Wei, K. K., Gu, J., & Chen, H. (2010). The role of institutional pressures and organizational culture in the firm’s intention to adopt internet-enabled supply chain management systems. Journal of Operations Management, 28(5), 372–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2009.11.010

- Liu, T., Li, M., & Wu, M.-F. (2020). Performing femininity: Women at the top (doing and undoing gender). Tourism Management, 80, 104130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104130

- Marlowe, C. M., Schneider, S. L., & Nelson, C. E. (1996). Gender and attractiveness biases in hiring decisions: Are more experienced managers less biased? Journal of Applied Psychology, 81(1), 11–21. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.81.1.11

- Martínez-Ferrero, J., & García-Sánchez, I. M. (2017). Coercive, normative and mimetic isomorphism as determinants of the voluntary assurance of sustainability reports. International Business Review, 26(1), 102–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2016.05.009

- McDonnall, M. C., & Lund, E. M. (2020). Employers’ intent to hire people who are blind or visually impaired: A test of the theory of planned behavior. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 63(4), 206–215. https://doi.org/10.1177/0034355219893061

- McLarney, E. (2016). Women’s rights and equality: Egyptian constitutional law. In F. Sadiqi (Ed.), Women’s movements in post- “Arab Spring” North Africa (pp. 109–126). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mensi-Klarbach, H., Leixnering, S., & Schiffinger, M. (2021). The carrot or the stick: Self-regulation for gender-diverse boards via codes of good governance. Journal of Business Ethics, 170(3), 577–593. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04336-z

- Meyer, J. W., & Rowan, B. (1977). Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. American Journal of Sociology, 83(2), 340–363. https://doi.org/10.1086/226550

- Mickey, E. L. (2022). The organization of networking and gender inequality in the new economy: Evidence from the tech industry. Work and Occupations, 49(4), 383–420. https://doi.org/10.1177/07308884221102134