Abstract

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) is evolving, with new sustainability issues and related tasks emerging as priorities for large hotel groups. Within this institutionally complex environment, the role of CSR manager (a relatively new professional role) is becoming ever more diverse and contextualised. We unveil how CSR managers advance their work amidst logic plurality in the early stages of institutionalising CSR. Through interviews (with eight senior managers responsible for sustainability and eight sustainability experts) and pattern-inducing interpretive analysis of the resulting data, we gain a practical understanding of CSR under four institutional logics: corporate, market, professional and sustainability. Three micro-level strategies - anchoring, switching and interlinking - allow individuals to advance organisational CSR work where multiple logics are pertinent for legitimate actions. Adherence to a single frame of reference (e.g. one logic) guides most organisational practices, with managers rarely switching between logics to adapt to situations and audiences, or linking practices enacted from different logics. This results in low problematisation of the work of CSR managers, and avoidance of tensions. Implications are discussed for organisations engaging in CSR, including the organisational advantages and risks that emerge as CSR managers evolve to become hybrid professionals.

Introduction

International hotel groups face a broad range of expectations for sustainable development, which leads to different ways in which sustainability is understood and practiced (Font & Lynes, Citation2018; Guix & Font, Citation2020). Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) has made its way into board rooms as a critical strategic management task to address the demands of multiple stakeholders. Yet, CSR remains a conflict-ridden and evolving field (Brès et al., Citation2019) with constant integration of new “hot” topics, as evidenced in hospitality (Uyar et al., Citation2021). Management of CSR demands must accommodate co-existing logics that are often competing and contradictory (Ertuna et al., Citation2022), and frequently involve underlying ambiguities (Borglund et al., Citation2023). Within this increasingly complex environment, CSR managers must make decisions about organisational CSR work; the role of CSR manager needs to expand to accommodate the new sustainability topics and related new tasks (Risi & Wickert, Citation2017).

Given that logics shape “how managers interpret reality and act upon it” (Borglund et al., Citation2023), the underlying values ascribed in the multiple logics may imply differing, and sometimes contrasting, ways of comprehending and dealing with specific organisational practices. However, we do not currently understand the role of CSR managers in CSR implementation (Brès et al., Citation2019; Fatima & Elbanna, Citation2023; Wickert & De Bakker, Citation2018). Research that provides an understanding from an institutional logics perspective is scarce (Dahlmann & Grosvold, Citation2017; Greenwood et al., Citation2011) and, within the field of tourism, has only recently been introduced (Fong et al., Citation2018). In hospitality, prior literature explores institutional logics at the organisational level, uncovering institutional logics engaged in the diffusion of CSR between headquarters and its affiliated hotels (Ertuna et al., Citation2019; Citation2022). With the exception of Kiefhaber et al. (Citation2020), in small and medium sized hotels, little is known about the role of managers from an institutional logics perspective. In this article, we zoom in on the role of individuals in managing institutional complexity and ask: How can CSR managers advance organisational work in an environment where multiple logics are pertinent?

This study aims to identify institutional complexity from logic plurality around sustainability at the headquarters of multinational hotel groups and explore how CSR managers in the most senior positions with responsibility for sustainability issues and CSR experts use distinct logics to advance organisational work. Because logics can differ across time (Lounsbury et al., Citation2021), we focus on a particularly complex institutional environment in the early stages of institutionalising CSR at the time the organisation adopts the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) standard for reporting. While these two frameworks are considered to be norms that guide the CSR efforts of leader hotel groups (Ertuna et al., Citation2022), in 2022, barely half of the largest hotel groups articulate their alignment with the SDGs (UNEP & Surrey, 2022), and less than 20% publish sustainability reports following the GRI standard (de Grosbois & Fennell, Citation2022; Guix & Font, Citation2020). Low levels of CSR institutionalisation, combined with the complexities involved in managing a multitude of CSR factors, across borders and in response to diverse stakeholder pressures, make CSR managers at large hotel groups an object of study for institutional logics.

We identify a plurality of logics around sustainability as clusters of organisational practices, thus, contributing to the literature on institutional logics among CSR professionals by moving beyond the duality of logics persistent in current research (e.g. Borglund et al., Citation2023). We respond to the lack of studies that apply a micro-strategising lens to understand the actions taken by those in charge of implementing CSR (Wickert & De Bakker, Citation2018). Adopting a practice-driven institutionalism approach (Smets et al., Citation2017), we then explore how managers and experts use logics as a resource to advance organisational CSR work in a setting of low levels of CSR institutionalisation. We contribute to the nascent literature on institutional logics in hospitality (e.g. Ertuna et al., Citation2022), and add to the limited understanding of how individual actors operate across co-existing logics (e.g. Pache & Santos, Citation2013a) outside hybrid organisations (e.g. Smets et al., Citation2015).

Literature review

Institutional logics in corporate sustainability

Organisations and actors face pressures that reflect distinct institutional logics, which are “the socially constructed, historical patterns of material practices, assumptions, values, beliefs, and rules” (Thornton & Ocasio, Citation2008, p. 804). Institutional logics, as shared patterns of cognition, guide individual actors’ behaviours and collective practices, and provide them with common frames of reference to guide and give meaning to their work. Logics can be conceptualised as resources that managers strategically employ when they engage in, and negotiate, everyday organisational challenges (Lounsbury et al., Citation2021). Multiple logics are reflected in, and legitimise, organisational practices (Luo et al., Citation2017).

Thornton et al. (Citation2012) propose seven “ideal types” of institutional logics based on: the state, the market, the family, religion, the profession, the corporation and the community. Scholars identified six CSR-related institutional logics either applying the “ideal types” (e.g. Arena et al., Citation2018) or through a grounded approach (e.g. Ertuna et al., Citation2019). A regulating/compliance logic, as prescribed by the state, focuses on compliance with Environmental Social and Governance (ESG) regulations, and mandatory disclosures of non-financial information (Arena et al., Citation2018; Ertuna et al., Citation2019; Madsen & Waldorff, Citation2019). A market-based logic is finance-centric and responds to pressures for growth and profit maximisation in sustainability (Cerbone & Maroun, Citation2020; Ertuna et al., Citation2019) with reporting being a tool for legitimacy (Dahlmann & Grosvold, Citation2017) and reputation management (Arena et al., Citation2018). A professional logic is characterised by avoidance of trade-offs and tensions, collaboration with “professional” networks and adherence to codes of best practice (Arena et al., Citation2018; Borglund et al., Citation2023; Cerbone & Maroun, Citation2020; Ertuna et al., Citation2022; Kiefhaber et al., Citation2020). The environmental/sustainability logic attempts to reconcile economic, ecological and social considerations (Dahlmann & Grosvold, Citation2017; Ertuna et al., Citation2019; Madsen & Waldorff, Citation2019; Schneider, Citation2015) and closely relates to the stakeholder logic in its need to respond to various, legitimate, stakeholder information needs (Cerbone & Maroun, Citation2020; Madsen & Waldorff, Citation2019). The community logic is particularly relevant when diffusing CSR practices from the head offices to local actions with community impact (Arena et al., Citation2018; Ertuna et al., Citation2019; Citation2022). Finally, Borglund et al. (Citation2023) identified CSR managers as being “organisational professionals” who are highly embedded in the corporate logic. Overall, CSR managers require a holistic understanding of multifaceted aspects of the business, which are reflected in various institutional logics.

CSR managers negotiate the meaning of institutional pressures and decide appropriate responses. An institutional logics perspective is part of a turn to actors and their agency (DiMaggio, Citation1988) that underlines the active roles of individuals in reproducing and changing institutions. Actors are seen as the carriers and enactors of social practices within a practice-driven institution (Smets et al., Citation2017). Practices, are the material enactments of institutional logics, as “patterns of activities that are given thematic coherence by shared meanings and understandings” (Smets et al., Citation2012, p. 879). This approach enables us to understand logics as “part of the ordinary, everyday nature of work” (Smets et al., Citation2017, p. 29). Logics are enacted in praxis through actors’ agency, and everything "becomes" through the relations of multiple components in the social structure (Schatzki, Citation2001). Thus, different patterns of relationships create configurations of logics that are constantly shifting. Scholars have paired two logics and portrayed them in a binary fashion, as either compatible or contradictory. Others have considered logics to be in a dynamic interplay, irrespective of their compatibilities or contradictions, and that practitioners are engaged through their praxis in constructing “dynamic patterns of complexity” (Greenwood et al., Citation2011, p. 334). This latter approach emphasises the role of individual actors in interpreting and enacting the logics. The relation between co-existing logics depends on what aspects of logics collide and on how practitioners bring situational logics together in their everyday practice.

Tensions, complexity and individual, micro-level strategies

Just as institutional logics are enacted in practice, their tensions are problematised in practitioners’ everyday praxes. Tensions emerge among institutional logics, as conflicts emanate from different societal ideals. The “encounter of incompatible prescriptions from multiple institutional logics” (Greenwood et al., Citation2011, p. 317) is known as institutional complexity. Institutional complexity complicates organisational tasks, for example, when market and nonmarket logics co-occur (Pache & Santos, Citation2013b). The demands of the market and the sustainability logic often place competing demands (Kiefhaber et al., Citation2020; Schneider, Citation2015), as in the meaning and role of integrated reporting (Cerbone & Maroun, Citation2020).

Turning our attention to individual practitioners, a review of the situatedness of their actions and the relationality of the logics they enact, assists in revealing the micro-level strategies adopted to manage complexity (Smets et al., Citation2017). Actors in their everyday work maintain strange logics separately or construct contradictory logics as compatible or as complementary (Smets & Jarzabkowski, Citation2013). There is only a nascent understanding of how individuals dynamically balance the competing demands of distinct logics (Smets et al., Citation2015). In the presence of co-existing logics, individuals show multiple responses that aim to reduce complexity or absorb complexity. Complexity reducing strategies include ignoring the prescriptions of one logic, non-consciously complying with one logic prescription or active defiance of the practices from one logic (Pache & Santos, Citation2013b). Complexity absorbing strategies aim to reap the benefits of logics that are “conflicting-yet-complementary” through logic combination as a result of blending values, norms and practices by selectively coupling intact elements drawn from different logics or developing new practices that synthesise competing logics (Pache & Santos, Citation2013b). Also, compartmentalisation serves to enact all logics while keeping them separate upon purpose, and according to audience, time and place (Pache & Santos, Citation2013b). Smets et al. (Citation2015) identified segmenting, which enables managers to maintain distinct logics by assigning their enactment to different situations and localities. Also, demarcating is over-privileging one logic over another. Finally, bridging enables managers to combine practices that are governed by competing logics to reap their complementarities. The prevalence of institutional logics, and their practical, operational tensions is particular to historical times and cultural environments (Thornton & Ocasio, Citation2008); thus, micro-level strategies adopted to manage complexity, are likely to be historically contingent. Despite the progress in management literature, there remains limited understanding of how individual actors enact simultaneous logics in the context of CSR and no knowledge of how they do so in the context of tourism and hospitality.

CSR managers as hybrid professionals

We adopt the term “CSR department” for simplicity as departments managing CSR from multinational hotel groups’ headquarters receive various names. We approach CSR managers as practitioners inside organisations who “represent” logics and continuously cope with the complexities they face (Pache & Santos, Citation2013b). In the health care sector, professionals working at the intersection of competing logics are called “hybrid professionals” (Blomgren & Waks, Citation2015; Sirris, Citation2019). They are professionals within one area of expertise who develop relational capabilities in other areas of expertise, to cope with external pressures (Noordegraaf, Citation2007). While the number of logics, and the degree to which actors are deeply embedded in these, may vary, hybrid professionals emerge in settings where different logic understandings are pertinent.

Hybrid professionals often engage in mundane and pragmatic work in coping with institutional complexity. They switch between logics and promote different discourses in their work (Zilber, Citation2011) as they choose how, where and when to enact distinct logics (Smets et al., Citation2015). An important part of their work is to construct problems and solutions that align with all the logics at play (Blomgren & Waks, Citation2015). To date, the literature about hybrid professionals has developed in the health sector, however, given that “many professional occupations require skilled individuals … to continuously work across different logics” (Smets et al., Citation2015, p. 43), it is likely that characteristics of hybrid professionals are exhibited in multiple sectors. We contend that CSR managers at multinational hotel groups, governed by diverse institutional influences such as commercial interests, professional norms and corporate control, navigate the competing demands of sustainable development and organisational goals, and, therefore, are likely to exhibit the characteristics of hybrid professionals.

Methodology

This study focused on large, well-known hotel groups because such organisations receive the most institutional pressure and scrutiny (Luo et al., Citation2017). We used purposeful, criterion-based, expert sampling to promote sample representativeness. The interview set consisted of 16 interviews (Appendix 1: Interviewee’s profile, supplementary materials), of which eight were with managers and eight with experts (defined as such due to their knowledge of CSR). Managers and experts were “representative” of a specific role. As per Borglund et al. (Citation2023), managers were required to be the most senior person responsible for sustainability in the organisation. Similar to prior research (e.g. de Grosbois & Fennell, Citation2022; Guix et al., Citation2018), we selected organisations that were part of the top 50 largest hotel groups in the world, with size defined by the number of rooms in 2015 (Hotels Magazine, Citation2015), which was the year of the promulgation of the SDGs.

Professionals in a field are “key carriers and evangelists of logics” (Lounsbury et al., Citation2021, p. 272), socialising managers with those logics that are then interpreted and reproduced. From the interviews with the CSR managers, we identified a pool of CSR field-level actors who could provide insights on: CSR logics among large hotel groups, how actors relate to those logics, and how actors use the logics to advance their work. We employed subgroup sampling to select an additional pool of expert respondents, each of whom held a senior position at either a reporting standard setter, a consultancy firm, a non-governmental organisation, or was an academic working on CSR research with one of the CSR managers being interviewed. The combination of multiple sources (CSR managers and experts) enabled us to triangulate information and enhance the validity of our findings through comparisons between results.

The study aimed to capture the institutional logics of CSR at the time of adoption of the SDGs, when such logics are relatively new to the organisation. Over time, practices and the associated logics tend to diffuse in multiple waves, and organisations neutralise the created complexity through new decisions (Shipilov et al., Citation2010). The data was collected via Skype© with interviews taking about 30–60 min on average. All interviews were audio-recorded and conducted in the respondent’s native language; 14 in English and 2 in Spanish. Interviews in Spanish were translated by a bilingual researcher and back-translated by a second researcher to verify the accuracy. The interviews were semi-structured and covered the development of sustainability management practices including reporting, the involvement of external actors and the evolution of CSR (see the interview protocol in the Appendix 2, supplementary materials). Follow-up questions were asked like “why”, “in which way”, “what happened” making the respondents develop answers.

We relied on an interpretative methodology to elucidate the complexities of CSR in hospitality (Schaffer, Citation2015), in particular, by seeking to locate co-existing institutional logics in the language surrounding hospitality CSR, i.e. how social actors make sense of corporate “sustainability walk and talk”. We identified institutional logics by employing pattern inducing interpretive analysis, used to qualitatively capture institutional logics (Reay & Jones, Citation2016). Pattern inducing was deemed the most appropriate method due to its ability to capture nuances of i) localised practices, ii) actors’ explanations of values and beliefs, and iii) the rich context of the particular understanding of the logics by the actors interviewed (Reay & Jones, Citation2016). Accordingly, we adopted a grounded approach that focused on raw data and a bottom-up process, in a similar way to previous researchers who have employed pattern inducing interpretative analysis (e.g. Dahlmann & Grosvold, Citation2017; Smets et al., Citation2012).

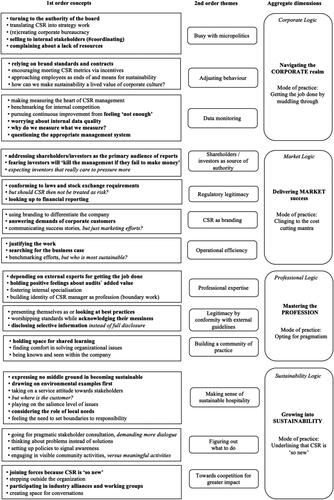

To better understand how CSR managers get their job done, we developed an iterative, three-step process of qualitative data analysis. The aim of Step 1 was to identify the practical understanding of the institutional logics present in the data. We employed the Gioia methodology, suitable for inductive process of analysis, to ensure rigour in the qualitative, interpretive enquiry (Gioia et al., Citation2013). We undertook open coding with emergent informant-centric initial data coding of 1st order terms, followed by axial coding, grouping codes into more abstract, theory-centric 2nd order themes (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1998) and, finally, distilled those into overarching dimensions through consultation with extant literature (Gioia et al., Citation2013). We coded the 11 h of transcripts simultaneously and then, through multiple rounds of going back and forth between data and theory, and discussion to reconcile any differing interpretations, we arrived at a consensual interpretation of the 1,101 segments that had been coded using software MAXQDA©. Next, we built a “data structure” of 1st-order terms, 2nd-order themes and aggregate dimensions, following convention (Gioia et al., Citation2013). We performed back-checking of the interpretations of the data to improve internal validity.

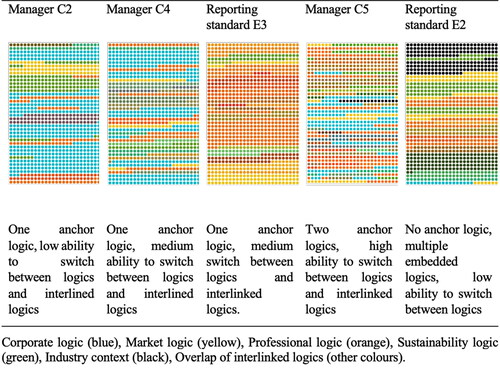

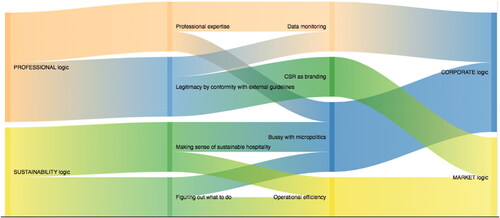

In Step 2, our intention was to explore how individuals engage in the dynamics of logics in CSR work via three micro-level strategies: i) how often they engage with each logic (anchoring); ii) how often they change from one logic to another (switching); and iii) how they connect the logics (interlinking). We adopted a novel approach to interpret and make sense of the interview data coded for institutional logics through quantification and visualisation tools. We built on practices previously used to analyse documents based on the percentage coverage of text and visualisation of the extent of variation (e.g. Guix & Font, Citation2020). We also employed visualisation artefacts (Langley & Ravasi, Citation2019), such as: i) interview portraits (), to show variation among interviewees with respect to their reliance on distinct logics; and ii) the Sankey diagram (), to show the linkage between themes of different logics.

Inevitably, interviewees provided multiple claims in one sentence that could be coded under distinct logics. We responded to this by using the claims as unit of analysis to identify different micro-level strategies. To explore how interviewees related to each logic, we calculated the percentage of codes for each logic out of the total number of coded segments on logics within each transcript (see in the results section). If we coded more than 30% of the transcript under one logic and another logic was not of relative strength, this was considered an Anchor logic. When a logic was present in more than 20% of the transcript, it was considered an Embedded logic, and if equal to or less than 20%, an Emerging logic. Logics were considered “of equal strength” among an interviewee when there was a maximum 5% difference on their score for coverage of coded segments. To identify the switching micro-level strategy, we counted the number of times that interviewees changed between logics, based on the changes in aggregate dimensions ordered by appearance. Based on a measurement of the number of switches they made, we scored each interviewee as high (60-89), medium (30-59), or low (0-29).

Table 1. Anchor, embedded and emerging logics among interviewees.

In Step 3, to identify connected logics, we re-analysed the 65 coded segments that were defined as complexity (those with overlapping first-order concepts coded from distinct logics). We scored interviewees as high (>20 connected segments), medium (10-19), or low (1-9). To identify how each interviewee framed the nature of the relationship between the first-order themes of each logic identified in the segment, we used an approach taken from Smets et al. (Citation2015), which includes arrows to indicate a relationship between the elements in terms of the direction of chronology, outcome or influence implied. Thresholds were derived inductively, based on the data, and were then applied consistently across all the transcripts. The thresholds were created to signify intensity or trends and should not be understood as expressing precise levels. Quantifications are made for creating the visual artefacts in the diagrams, as suggested by Langley and Ravasi (Citation2019), and levels depicted are indicative only and contextual to this study rather than intending to convey generalisation.

We adopted a co-constructed approach to Steps 1, 2 and 3, whereby the two researchers worked together, live and online, to code the transcripts and back-check the interpretation of the data, to build the final data structure and identify the strategies. When items of disagreement emerged, primarily when coding for micro-level strategies, they were resolved in consultation with previous literature.

As competing logics from different societal sectors potentially influence any context (Thornton & Ocasio, Citation2008), we could not ensure that other logics were not captured by the interviewee. However, the CSR professional sampling enabled us to capture a broader set of societal actors. Also, following convention (Cerbone & Maroun, Citation2020), re-analysis four months later was used and no additional logics emerged. Thus, the most significant logics that had affected CSR managers in their everyday work had been captured to answer the research question.

Results

Logics in CSR work and how they are enacted in practice

The results of the study unveiled a practical understanding of the CSR-related logics of individual actors who were bound in the hospitality sector at a time of early adoption of SDGs and reporting guidelines. The managers leaned on four logics: corporate, market, professional and sustainability ().

Figure 1. Structured coding of institutional logics of CSR in hospitality.

Standard text indicates themes from the CSR managers only. Text in italics indicates themes from the experts only. Text in bold indicates themes expressed by both the managers and experts.

Source: Authors’ own elaboration

Navigating the corporate realm

Under the CORPORATE LOGIC, CSR managers progressed CSR performance by muddling through the multinational organisation’s structure. Although the boards were not knowledgeable about CSR, they drove the managers’ work in this area and yet, often, did not provide resources: Consultant E5 explains “Very few leaders really understand the complexity of sustainability” similarly expressed by Consultant 4 “I’m going to hire somebody, give them a small team, very little resources, and they can figure it out.” Managers were busy with micropolitics, entangled in ensuring their right to exist, ‘fighting for being part of the strategy of the company’ (Manager C1), and re-creating corporate bureaucracy through the CSR governance structure (committees, working groups, processes and policies).

Managing CSR performance depended on the ability of the managers to adopt a middle ground position between securing top management support for CSR strategies and adjusting the behaviour of employees, suppliers and property owners to ensure implementation. Managers employed normative control to convince internal stakeholders who “are working with making money and selling, and if they get a little bit of time, they work with sustainability stuff” (Manager C7). More coercive practices included forcing owners to comply with sustainable brand standards (Manager C1), imposing suppliers’ code of ethics (Manager C7), or rewarding managers through CSR bonuses (Managers C2 and C4). The franchising model led to efforts as ‘how persuasive you can be’ (Manager C5), turning managers into political actors.

Employees were the means to deliver a sustainable hospitality experience through top-down educative initiatives (Manager C7), and the ends of sustainability metrics, such as a healthy environment to work in (Manager C4). NGO E1 explained, “It’s not because you have an employee volunteering programme. Because you have engaged employees, you’ve got great service.”

To make sustainability manageable, data monitoring was central. CSR managers found themselves part of the annual financial year, (in)voluntarily following a mantra of “what we measure, we can reduce” (Manager C1); they went through cycles of continuous improvement and reporting. The managers stressed “we have a long way to go” (Manager C6). They tackled unresolved decisions concerning the right measures (Consultant E4), ensured data quality (Manager C5) and set up management systems.

Overall, amidst the bureaucracy and micropolitics of large corporations, the CSR managers were getting the job done by muddling through strategising, adjusting behaviours, measuring and reporting on practices, to demonstrate performance.

Delivering market success

The need to demonstrate financial performance guided the MARKET LOGIC whereby the managers addressed the needs of the shareholders and investors as the main source of authority. CSR managers were “busy with profitability challenges… The other stakeholders are not getting high on their agenda” (Academic E7). Shareholders were seen to hold enough power to “kill the management of companies that fail to make money” (Reporting organisation E2). Thus, investor pressure was a resource for pushing the sustainability agenda or bringing unsustainable efforts to a halt: “not enough investors are asking for this yet” (Manager C5).

CSR managers sought regulatory legitimacy through compliance with non-financial, market-based regulations as the ESG disclosure on Hong Kong Stock Exchange: “we are obliged” (Manager C3). However, while the managers praised financial reporting for its appealing format and sound routines (Managers C3 and C4), the experts called for CSR to be treated more as a financial risk with tighter disclosure and standardised metrics. For example, on guests’ carbon footprints, Reporting organisation E2 stated there were “horrible numbers,” while Manager C1 observed “compared to other industries, our carbon footprint is peanuts.”

Sustainability reporting was framed as an art of communicating success stories “(the) big story on reduction” (Manager C1). Reputation and CSR branding, focused CSR efforts on differentiating the company from its competitors (Manager C7) and attracting customers and employees (Manager C3). Experts saw reports as a dubious marketing effort (Academic E8, NGO E1): “if you seem to have great performance somehow every year, then there’s something wrong” (Consultant E4).

Operational efficiency provided the means to achieving profit maximisation. Practices such as “energy cost reductions” (Consultant E4) had been around “long before any sustainability strategy was officially developed” (Manager C5). Experts were concerned that easy and low-cost practices were chosen in place of more substantial ones (Consultant E6). Often managers sought to portray and legitimise their efforts by “improving the bottom line” simply because “it’s hard to have a focus on sustainability if you are not making money” (Manager C7). Despite the cost-cutting mantra, proof of delivering market success seemed unattainable, as expressed by Academic E8 ‘They have a nice overall CSR report and sustainability goals but if you look at the individual hotels, I do not see why they are green’.

A few of the interviewees took a broader view, toward value creation:

The big challenge is that consumers, employees and investors choose you because you are a sustainable hotel… This will be the end of the story… but still we are not making money out of this (Manager C1).

Mastering the profession

The PROFESSIONAL LOGIC was mainly adopted for sustainability reporting when CSR managers depended on professional expertise. External experts served as knowledgeable guides; when managers “feel a little bit extreme in making policies” (Manager C7) or they gave assurances through data validation. The external experts were socialisation agents for the managers, enabling them to gain the necessary professional expertise to develop a professional identity. Consultants valued the strong professional relationships being aware that “in the hotel industry you don’t have many sustainability managers to understand the topic very well” (Consultant E5).

CSR managers worked at the intersection of finance, marketing, quality control and maintenance departments. To extend the boundaries of their roles and to get the necessary metrics delivered, CSR managers coordinated internal specialists between departments to support their reporting practices: “About 80 different people from across the company… based on their own knowledge of their areas” (Manager C5).

Managers sought legitimacy through conformity with external guidelines, aiming for best practices in recognised external standards as a signal of their professionalism: “We are the only hotel company that participated in the tests” (Manager C3); “We were the first hotel company reporting to that standard” (Manager C1). While worshiping standards, they acknowledged their messiness due to a need for “streamlined reporting from multiple frameworks and the SDGs” (Manager C4). Yet, despite adhering “as much as possible” to the standards, or perhaps because of them, there was a shared sense of disclosing selective information because, as Manager 5 admitted, “in CDP, an honest answer on a challenge can lead to a loss of points.” Somewhat at odds with the idea of best practices, it was still “really hard for an investor to actually know who are the true sustainability leaders” (Reporting standard E3).

Looking for professional allies went beyond expert consultants and colleagues. Building a community of practice across organisations opened space for shared learning and helped CSR managers to enter their new, and sometimes overwhelming, roles: “For me, I was really blind in the beginning” (Manager C1). The community of CSR managers developed into a support network that enabled its members to “see the key issues collectively to the industry” (Consultant E4). Engagement fed back into the organisational roles, strengthening the positions of CSR managers as experts. However, participation in industry alliances was not free from frustration: “they are the only ones benefiting from it” (Manager C7).

Whether it is the use of experts and colleagues or turning to available standards and best practices “from golden companies” and “copying them” (Reporting Organisation E2), working under the professional logic meant to opt for a pragmatic approach to CSR management; one that facilitated the fast adoption of a new set of practices.

Growing into sustainability

A practical understanding of the SUSTAINABILITY LOGIC revolved around central questions about the process of “becoming” sustainable, such as, which ends to pursue and how to define success; which issues and stakeholders to consider; which means to employ.

In making sense of sustainable hospitality, the sustainability logic triggered unresolved questions, such as, how far the responsibility of a single organisation goes (Academic E7, E8), or whether business growth should allow for more greenhouse gas emissions (Manager C1, C8, NGO E1). Managers considered balancing the triple-bottom-line to be central to the sustainability logic. Some narrowed the scope by sticking to environmental sustainability and treating the other dimensions as either too costly (“It costs too much money” Manager C8) or of lower relevance (“The social side, it’s anecdotal stuff” NGO E1). Experts called for a service attitude towards customers and local communities. Exploring “what the customer wants” (Academic E8), adapting targets “to be more specific for the destination” (Manager C6), or defining community programmes for “properties to find something that is appropriate to the local communities” (NGO E1) were emerging practices.

In their attempts to figure out what to do, managers prioritised “what is more practical” (Manager C1). They engaged in pragmatic consultation acknowledging that “we have to learn and expect more about how to work with stakeholders” (Manager C7). Experts called for more dialogue with owners to “get them involved in the hotels” sustainability discussions’ (Consultant E4). Another practice readily available was developing policies to signal awareness of salient issues (Manager C7). Still, the experts (such as NGO E1) noted a struggle between meaningful impact through “how you are operating your business” and visible practices such as “standalone philanthropy.”

When discussing means to achieve sustainability, actors often drew on structural deficits of the industry as low EBITDA or the necessity of air travel under a narrative that “CSR is so new” (Manager C1). Collective efforts towards coopetition for greater impact relied on collaborations with partners outside the corporation, such as the industry “hotel carbon and the water measurement initiatives” (Manager C5), which turned actors’ mindsets towards solutions. Collaborating with peers in industry alliances, the individuals “learned from each other” (Reporting Organisation E2) and “worked around the topics of interest” (Manager C5).

Overall, underlying the newness of CSR in the corporate realm at that time, was what defined the sustainability logic; where conversation, collaboration and learning became central practices to clarify the objectives and practices of sustainable hospitality.

Actor’s strategies to advance their everyday work

Having identified the co-existing logics in CSR, and the practices enacting each, we turn to the strategies that managers used to “get their work done.” CSR managers used three strategies: anchoring, switching and interlinking (). Anchoring captured 92% of the interview statements that were coded under a single logic with no overlap of codes from different logics. Switching captured the amounts of times that actors changed their frames of reference, i.e. the logic they used to describe their work. Interlinking revolved around the statements that showed the actors’ abilities to connect two logics when talking about their work.

Figure 2. Visualisation of exemplary individual-level strategies: anchoring, switching and interlinking.

Source: Authors.

Strategy 1: anchoring

Anchoring consisted of actors adhering, to different degrees, to institutional logics, with the anchor logic becoming the frame of reference to discuss their everyday practices. shows the actors’ levels of adherence to different logics when discussing their CSR practices or those of the managers. For most CSR managers, CSR was seen as an issue in the corporate domain, thus, the “anchor” logic that dominated their narratives, and that they repeatedly returned to, was the corporate logic. Yet, all the interviewees touched on multiple logics, including logics they seemed familiar with (embedding logics) and logics that seemed new to them (emerging logics). Some actors adhered strongly to just one logic (the corporate logic) and weakly to other logics (Managers C2, C6, C7) while others had no dominant logic, so their narratives exposed high centrality of co-existing logics in their job (Manager C1, Reporting standard E2, Consultant E4). The emergence of the sustainability logic suggested low socialisation of CSR managers in that logic, with only one manager (C3) and two experts (NGO E1 and Academic E7) exposing sustainability as an anchor logic. Only two other managers adopted sustainability as an embedding logic, which supported its “newness,” as expressed by the managers. Adherence levels offered an understanding of how individuals used familiar frames of reference when talking about their work.

Strategy 2: switching between logics

Switching captured how individual actors exerted agency when choosing which logics to use, adjusting to particular situations by flexibly jumping from one logic to another. As seen in , having a bigger repertoire of logics (i.e. having a more diverse set of anchor and embedding logics illustrated in ) did not necessary lead to a higher agility to switch between those logics. Only three interviewees showed high switching between logics (Managers C1 and C5, and NGO E1) and a further three interviewees showed low switching (Managers C2 and C6, and Reporting standard E2).

Table 2. Switching between logics and engaging in complexity through interlinked logics.

Strategy 3: interlinked logics

Interlinking was based on the number of statements reflecting interlinked logics. Interlinking was a minor strategy, which tended to relate one logic with the person’s anchors’ logic through three distinct tactics (organised by less to more balance between logics): Borrowing, Narrowing and Integrating complementarities. Appendix 3 (supplementary materials) provides a list of practices, and illustrative quotes. shows a visualisation of the most frequent relationships.

Figure 3. Sankey diagram of exemplary interlinked logics, including second order themes.

Note: The width of bands indicates the frequency of occurrence of links between logics.

Tactic 1, narrowing, consisted of reducing the set of possible practices or the scope of a practice associated with one logic to fit it to another logic. Narrowing was the tactic most commonly employed and, in practice, led to prioritising practices from one logic over another. This micro-level strategy helped managers to narrow down (reduce) practices to fit the corporate logic, thus, making the job more manageable. For example, reducing the scope of sustainability issues or the extent of stakeholder engagement to fit corporate bureaucracy. Other practices reduced the market logic to fit the corporate needs, making CSR benchmarking manageable or narrowing the use of professional standards only to reporting. The narrowing tactic was used to fit practices under a market logic for making the job successful, such as prioritising sustainability issues through a market lens. Also, managers narrowed down the scope of disclosure from the professional logic to fit the branding and reputation of the market logic (e.g. “Avoiding reporting red footprints”). Thus, narrowing was employed to fit a reduced practice, or scope of practices, associated with the sustainability or the professional logics, to the corporate or market logics.

Tactic 2, borrowing, consisted of temporarily importing a practice from another logic, usually the professional logic, to get the job done in such a way that each element from the distinct logics remained separate. Interaction among logics remained limited and time-bound, with no true identification with the logic borrowed nor any underlying changes to the practices. Borrowing was used to bring elements from the professional logic (external assuror, GRI indicators) to the corporate logic, temporarily, in support of the end-of-year reporting cycle (e.g. “Employing an external assuror to control data accuracy”). Practices also showed borrowing standards and ESG ratings from the professional by the market logic for reputation purposes (e.g. “Using standards to sell sustainable hotels”). Borrowing was the least employed tactic and was only used among the CSR managers.

Tactic 3, integrating complementarities, consisted of logic interactions that changed the resulting practices more permanently and was usually associated with the corporate logic. CSR managers incorporated elements from the sustainability logic to the corporate logic. For example, infusing bureaucratic planning, typical in the corporate logic, with community concerns such as “Leveraging destination needs to adjust corporate strategy,” or “Organising work through specialist teams at the country level.” Those actions widened the scope of a given practice (for example, strategising or organising) by being flexible and open to integrating bottom-up approaches. Another common strategy was integrating complementary elements from the professional to the corporate logic, such as “Using subject matter experts for incremental goal setting” or “Using standards to evolve CSR work.” There was a resulting change in the corporate practice from integrating specialisations and standards, rather than borrowing them temporarily. Experts often used integrating complementarities when they wish to use the standards to improve performance management.

Overall, CSR managers advanced organisational work through three strategies: i) anchoring - having a referent logic, a go-to logic to make sense of their work; ii) switching - being able to adapt their discourse to the situational fit; and iii) interlinking - bringing logics together by: reducing the set of possible practices to make a job manageable or successful (narrowing), importing a practice from another logic temporarily to get the job done (borrowing), or widening the scope of a given practice (integrating complementarities).

Discussion

We provide insights into the extent to which there is a multiplicity of logics in CSR work among large hotel groups and we offer a practical understanding of the logics at a specific time, i.e. in the early stages of CSR institutionalisation. Moving beyond the predominant duality of logics in prior research (e.g. Smets et al., Citation2015), we contribute to a more realistic appreciation of the interdependence of logics by identifying four CSR-related logics among large hotel groups. As logics are value-laden, and associated with distinct registers of, and reasons for, legitimate actions (Lounsbury et al., Citation2021), our results suggest that legitimate CSR work responds to executive board’s demands and, also, follows certifications and reporting standards, marked-based regulations and industry best practices.

As the most senior persons responsible for sustainability in the organisations, CSR managers condition and shape organisational practices by enacting separate or joined institutional logics; it is important to note that the emerging organisational practices that materialise will change, depending on the logics enacted. We uncover the relationality of the logics when CSR managers and experts describe organisational practices through three micro-level strategies: anchoring, switching and interlinking logics.

We contribute to the literature on co-existence of multiple logics (Ocasio et al., Citation2017) by revealing, contrary to prior research, that CSR managers in hotel groups do not necessarily engage in CSR work as a situation in which multiple logics lead to perceived contradiction and tensions. The common assumption in a field with institutional pluralism is that professionals are guided by a single logic (Dunn & Jones, Citation2010). Our results partially align, in that we identify that CSR managers operate around a dominant logic that helps guide their job (Anchoring). CSR among large hotel groups is an organisational issue, contrary to most CSR studies on institutional logics (e.g. Arena et al., Citation2018; Dahlmann & Grosvold, Citation2017) including studies within the hospitality industry (e.g. Ertuna et al., Citation2022). The need to implement new CSR topics and tasks within an organisation, during the early adoption phases of CSR, may explain the importance, at that time, of the corporate logic, thus, echoing that logics can differ across time (Lounsbury et al., Citation2021). To ease the implementation of CSR within large hotel groups, CSR managers introduce CSR governance structures and internal bureaucracy (policies and processes) that mimic existing organisational practices within other departments. Such practices can arguably support a consistent deployment of a CSR strategy across hotel group’s expansion (González-Rodríguez et al., Citation2019). Data monitoring also occupies much of a CSR manager’s practices, consistent with a response to normative pressures from reporting standards (de Grosbois & Fennell, Citation2022) and a focus on measurable performance in newly developing professions (Noordegraaf, Citation2007). Thus, the highly embedded, corporate logic may reflect the multinational component of the hotel groups, in which bureaucracy and hierarchy are critical to effectively managing increasingly asset-light business models. Anchoring on a single logic on its own with a lack of exposure and understanding of other CSR-related logics could lead in the long term to a narrow focus of attention on potential choices and courses of action and the neglect of specific legitimate concerns.

Our findings also reveal that other embedded logics guide most CSR managers’ practices, showing a defining characteristic of hybrid professionals (Sirris, Citation2019). Even though firmly anchored in the corporate logic, CSR managers show “a simultaneous capacity to find their way into, and relate to, several logics” (Blomgren & Waks, Citation2015, p. 97). Results support prior findings indicating that “the degree to which the professionals are deeply embedded in logics may vary” (Blomgren & Waks, Citation2015, p. 83). As context influences the strengths of logics in any given environment (Pache & Santos, Citation2013b) and prior socialisation with each logic shapes the availability of the logics to each actor (Thornton et al., Citation2012), CSR managers arguably experience different degrees of pressure, and internalise the co-existing logics to different extents. Familiarity with specific logics shapes the capacity of both CSR managers and experts to craft distinct practices and justifications. For example, while all the managers we interviewed worked for hotel groups that participated in collaborative industry initiatives (e.g. the Sustainable Hospitality Alliance) and in sustainability market indexes (e.g. the Down Jones Sustainability Index) only some of the managers chose to relate those aspects when explaining their CSR work.

The repertoire of logics available to CSR managers determines what they do and how they do it within an organisation. Practices show increasingly fragmented associations with multiple logics, arguably resulting from attempts by the CSR managers to link work to the organisation and its outside reality, a characteristic of hybrid professionals (Noordegraaf, Citation2007). The incursion of the market logic into the corporate understanding of CSR showed a numbers-centred way of thinking about how and why CSR should be implemented, the permissible costs involved, and what the company could expect to receive in return. Thus, our results reflect that CSR managers prioritise cost-effective actions and focus on demonstrating the CSR contribution to the organisation’s overall financial performance (Font & Lynes, Citation2018). Also, the prominence of environmental exemplifications may be evidence of the underlying market logic and its preoccupation with increasingly stringent environmental regulations.

Hybrid managers connect to other experts (Noordegraaf, Citation2007), which is seen through their reliance on internal specialist teams and external professionals under the professional logic. CSR managers try, step by step, to professionalise, which is a tricky task, given the multidisciplinary dimensions of CSR (Brès et al., Citation2019): “looking for a roadmap that I never came across, I’ve been doing it on my own, just studying on my own, and trying to find the best practices and just following the leaders” (Manager C1). CSR managers rely on tools for sustainability reporting, showing concern about securing professional processes as hybrid professionals (Noordegraaf, Citation2015).

The incoming sustainable logic suggests that sustainable hospitality is something unstable and always “becoming” through an ongoing amalgamation of practices that are enacted by CSR managers who try to make sense of, and act upon, institutional logics in the field of CSR. This finding is consistent with recent research on CSR professionals (Borglund et al., Citation2023). We find that hotel group sustainability logic is flexible, and consists of expanding the competence of the CSR managers, which may help the managers respond to broader issues (Uyar et al., Citation2021). The sustainability logic focuses managers on unresolved questions about sustainable hospitality and how best to achieve it. While CSR needs to reach a local understanding (Ertuna et al., Citation2022), our results echo prior research that found organisations seldom acknowledge destination-level actors (González-Rodríguez et al., Citation2019; Guix & Font, Citation2020). In leaning towards collective action to seek a shared sense of direction and belonging, CSR managers echo the practices of hybrid managers (Noordegraaf, Citation2015). However, because the anchor logic largely preconditions actors’ choices, the low centrality of the sustainability logic may limit hybrid managers’ strategic decisions on the scope and depth of the sustainability agenda, ways of implementing, managing, and measuring it, and their ability to recognize trade-offs and seek opportunities for sustainable development.

Given the availability of the multiple logics discussed above, managers have agency in choosing which logic they rely on for interaction. Switching is the result of the accessibility of logics, what “comes to mind in specific situations” and the activation, by managers, of those logics that “are used in social interaction” (Thornton et al., Citation2012, pp. 83-84). CSR managers only show a limited capacity to relate to multiple logics when looking for a situational fit. Some CSR managers switch between logics and promote different discourses in their work, which suggests they choose how, where and when to enact distinct logics (Smets et al., Citation2015). An ability to adhere to multiple logics, and to use them in different contexts and situations, arguably contributes to managing sustainability in an institutionally complex setting, such as within international hotel groups (Ertuna et al., Citation2022). While agility in switching between logics is considered a central characteristic of hybrid professionals (Zilber, Citation2011), most managers rarely adopt this strategy in the early stages of institutionalising CSR. Switching can be a valuable micro-level strategy for managers to individually tailor their approaches when interacting with others to gain the support of specific target audiences (Wickert & De Bakker, Citation2018). We contribute to the literature on how individuals manage complexity (e.g. Gümüsay et al., Citation2020) by defining the switching strategy as being the ability of managers to change their reference points in response to situational changes. Switching enables individuals to manage the fluctuating salience of competing demands effectively using logics as strategic tools for securing legitimacy. However, excessive reliance on the switching strategy without a clear and coherent underlying action may lead CSR managers to fall into isolated, ad hoc rationalisations and advance inconsistent and contradictory narratives and practices.

In the case of experts, adherence to logics shows how they reproduce existing institutions by socialising CSR managers with their anchor logic. For example, one interviewee who managed a reporting framework addressing investors’ information needs evidenced being anchored in a market logic whereas another who worked for a diverse reporting standard showed a broader repertoire of embedded sustainability, market and professional logics. Similarly, some consultant narratives showed a high level of familiarity with the corporate logic, which may be necessary for them to successfully influence the practices of the CSR managers through relating to the latter’s anchor logic (DiMaggio, Citation1988; Thornton et al., Citation2012). CSR professionals offer a critical voice to CSR managers practices expressing tensions within the “practical understanding” of logics. Differing views between managers and experts echo tensions inherent in CSR management (Høvring & Andersen, Citation2021).

Yet, in the early stages of institutionalising CSR, we find that CSR managers have limited engagement in tensions. Contrary to prior research (e.g. Smets et al., Citation2015), our results show that balancing demands from co-existing logics is only a small part of a CSR manager’s work. CSR managers experience and address complexity tangentially to their work, focusing on responding to institutional demands through separate practices that are each associated with different logics. In such a way, managers keep tensions between logics low and framed in a way that appears to be relatively free of tension. Our results, thus, support the view that “logics are not inherently conflicting or complementary, but are constructed as such in light of the nature of work that brings them together” (Smets et al., Citation2015, p. 43). We find that, when interlinking logics, CSR managers accommodate different logic prescriptions through three different tactics: narrowing, borrowing and integrating complementarities.

Managers often use narrowing, through which they reduce the set of possible practices, or the scope of those practices, to fit: i) the corporate logic - making the job more manageable; or ii) the market logic - making the job more successful. When narrowing the set of possible practices, the extent to which managers prioritise one logic over the others determines whether they give greater priority to that one logic, which could spark conflict between actors (Smets et al., Citation2015). Moreover, the narrowing strategy can become risky if a CSR manager persistently restricts the practices enacted for the sustainability logic to fit the corporate and market logic demands, because so doing may jeopardise their own legitimacy in the eyes of the sustainability logic representatives (Smets et al., Citation2015).

When borrowing elements temporarily from the professional logic to either the corporation or market logic, the chosen elements to combine are inherently unproblematic and enable a new practice without contradictions. Temporarily combining logics helps managers to advance practices by enacting one logic to facilitate another logic’s means, ends or values (Smets et al., Citation2015). We contend that borrowing can assist managers to advance CSR work at a given moment in time. When interlinking occurs, the choice of relationships of logics they construct (mostly, narrowing or borrowing) enables managers to avoid perceived contradictions. In the long term, relying on borrowing on its own carries the risk of neglecting critical but complex decisions on trade-offs between conflicting aspects of CSR and among actions to pursue, thus, limiting the capacity of CSR action to engage in a holistic approach to sustainable development.

Lastly, integrating complementarities, the least strategy used, represents the CSR manager’s most advanced effort of balancing logics and results in a widened scope of practices typically associated with the company/corporation that resonates with the “both-and” thinking of two logics (Smets et al., Citation2015). For example, CSR managers integrate the corporate and sustainability logics (strategising CSR to be flexible to the destination needs), or integrate the corporate with the professional logics (organising CSR through specialisation, managing CSR using standards for performance management). As the corporate is the predominant anchor logic for most managers, our study concurs with Pache and Santos (Citation2013b) that actors combine different logics when their adherence to each logic is strong. Integrating complementarities echoes the concept of “bridging” discussed by Smets et al. (Citation2015) in which an actor combines practices governed by competing logics to reap the benefits of their complementarities. In furthering sustainability efforts through the interlinking strategy, integrating complementarities seems a more permanent, complex, but promising avenue for progressing and institutionalising CSR work.

We contribute to the discussion in the literature on whether the common assumption of tensions between logics (that characterise institutional complexity) in the literature (e.g. Smets et al., Citation2017), is valid in the early stages of institutionalisation of CSR among multinational hotel groups, and if practices implemented reflect a problematisation of CSR managers’ work found in other contexts (Borglund et al., Citation2023). We argue that the three actor’s strategies discussed above offer functional ways for managers to avoid the complexity of tensions between competing demands in the short term. As a result of taking a referent logic, and less often switching the logic repertoire according to the situation, and avoiding balancing practices from distinct logic prescriptions, the CSR work remains unproblematised by managers. However, relying excessively on such a course of action in further institutionalising CSR within their organisation may threaten the hotel groups’ coherence, legitimacy and holistic contribution to sustainable development, as discussed above. Finally, it is essential to note that CSR managers do not exist in a vacuum and, thus, their agency through micro-level strategies is likely to be conditioned and shaped by macro-contextual and organisational factors, as suggested in recent research (Hunoldt et al., Citation2020; Lounsbury et al., Citation2021). While some logics may be accessible and hold legitimacy in CSR management and reporting, in some cases may be beyond the reach of CSR managers within their organisations.

Conclusion

Drawing on practice-driven institutionalism (Smets et al., Citation2017; Smets & Jarzabkowski, Citation2013), which considers how individual actors shape organisational practices, we unveil how CSR managers, a relatively new professional role among international hotel groups, experience and navigate the plurality of logics in CSR. We extend the understanding of institutional logics in the hospitality literature by offering empirical insights into multiple institutionalised logics in the CSR field, which has seldom been researched previously (Ertuna et al., Citation2019, Citation2022). We focus on individual actors with key roles in the diffusion of CSR practices (Risi & Wickert, Citation2017), to respond to the calls for attention to the micro-processes of institutional complexity (Gond & Moser, Citation2021) and to acknowledge how individuals operate across co-existing logics (Goodrick & Reay, Citation2011; Smets et al., Citation2017). Moving beyond the traditional binary focus on logics, common in prior CSR research (e.g. Dahlmann & Grosvold, Citation2017), we contribute to a more realistic appreciation of the “practical understanding” and interdependence of logics present in CSR.

Our study contributes to understanding the agency of CSR managers in furthering the sustainability efforts of multinational hotel companies. It expands the knowledge of how individual actors relate and use coexisting institutional logics to advance their work in evolving, institutionally complex environments via three micro-level strategies: anchoring, switching and interlinking. We discuss the importance and risks of these strategies that allow individuals to advance organisational CSR work in a context where multiple logics are pertinent for legitimate actions. These three strategies contribute to the limited management literature that studies how practitioners dynamically manage complexity in an attempt to balance demands from distinct logics or to keep them separate (Gümüsay et al., Citation2020; Pache & Santos, Citation2013b; Smets et al., Citation2015). Through these strategies, managers respond “in parallel” to different pressures with limited efforts to balance different logics through hybrid practices. We find that answering in parallel minimises the CSR managers’ engagement with tensions from competing demands, which is contrary to prior research in other settings (Borglund et al., Citation2023). Importantly, this behaviour enables progress in organisations with low levels of CSR institutionalisation. The focus on strategies to navigate multiple logics captures how CSR managers and experts enact their work and what the possibilities and limits of CSR work are in multinational hotel groups.

We propose that CSR managers are evolving towards hybrid professionals managing in the intersection of coexisting logics, thereby linking the literature on CSR professionals (e.g. Borglund et al., Citation2023; Brès et al., Citation2019) with that of hybrid professionals (Blomgren & Waks, Citation2015; Sirris, Citation2019). As hybrid professionals, CSR managers understand the multiple values and institutional pressures, and use their knowledge in a way that is likely to translate practices and processes across multiple logics. Skilful navigation of the complex context requires senior sustainability managers to engage with different logics and function as hybrid managers capable of linking different worldviews.

From a methodological perspective, we used a staged process for data analysis that combined a meaning-centric, and a more formalised, measurement approach. The meaning-centric approach enabled us to identify logics as clusters of organisational practices using an inductive technique. The formalised measurement approach enabled us to study the actors’ uses of those logics both when co-occurring and in sequence. The combination of both approaches reflects a unique data analysis strategy that delivers in-depth insights on how participants reflect on organisational practices. We demonstrate the value of quantification and visualisation tools (a novel approach in tourism and hospitality literature) to support the analysis and interpretation of qualitative data, and to represent and communicate theoretical insights (Langley & Ravasi, Citation2019). Visualisation enables the illustration of actor-specific configurations of logics; it makes patterns observable on how actors use and construct relationships between logics, revealing patterns of organisational work associated with distinct reasons for legitimate actions.

From a managerial point of view, we contend that knowledge of the three micro-level strategies we identify could support managers in most hotel groups who are at the early stages of institutionalising the SDG agenda and sustainability reporting (UNEP & Surrey, Citation2022). Logics shape attention and have constitutive power in shaping actions and their rationalisation. A practical understanding of the role of institutional logics in CSR work can provide a resource for managers as they navigate everyday interactions with stakeholders representing multiple, different institutional pressures. Using a frame of reference (anchoring) can facilitate unproblematised responses in everyday work within organisations. Switch between logics, according to the demands of each situation and audience, can successfully secure endorsement by field-level actors, for example, using the market logic when relating to investors or the corporate logic with board members. Similar to when a person adapts language to different circumstances, a change of logic, to fit a specific audience’s values, can assist in aligning rationales for action. In coping with different pressures, multiple logics must be enacted in various ways and situations to master the totality and complexity of CSR work. Becoming hybrid professionals capable of: harnessing knowledge vis-à-vis expertise in other areas, enacting practices embodied with different logic prescriptions, and combining different elements across logics through interlinking, can assist managers to deliver effective, legitimate performance across institutional domains.

The cross-sectional nature of this study limits our ability to understand how CSR managers skilfully navigate the different stages of institutionalisation and professionalisation over time. Future research using a longitudinal case study is pertinent. Similarly, a study exploring the factors that influence and shape the micro-level strategies can increase understanding of the possibilities and limits of CSR mangers’ agency. This research arguably contributes to the tourism sub-sector that has received the most attention in CSR literature (Wut et al., Citation2022), and further research would do well to focus on understanding institutional logics among less studied sub-sectors. Also, as co-existing logics are likely to be present for any middle management role (Høvring & Andersen, Citation2021), further research may wish to focus on CSR champions, how they navigate the competing demands on their time and how they balance their CSR responsibilities alongside their daily work.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (27 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Mireia Guix

Mireia Guix is a lecturer in tourism at the UQ Business School, The University of Queensland. She has consulted in projects for United Nations Environmental Programme, the Inter-American Development Bank, the European Commission, and national tourism government agencies. Her research focuses on sustainability accounting and corporate social responsibility for the tourism industry.

Tanja Petry

Tanja Petry works for a large social service provider in Austria as accommodation manager for refugees with disabilities. She is a doctoral student at the Department of Strategic Management, Marketing and Tourism at the University of Innsbruck and has published in outlets such as The International Journal of Human Resource Management, Employee Relations and Current Issues in Tourism. With a background in Organization Studies, her main research interests are employer-employee relationships, sustainable management and crisis management.

References

- Arena, M., Azzone, G., & Mapelli, F. (2018). What drives the evolution of Corporate Social Responsibility strategies? An institutional logics perspective. Journal of Cleaner Production, 171, 345–355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.09.245

- Blomgren, M., & Waks, C. (2015). Coping with contradictions: Hybrid professionals managing institutional complexity. Journal of Professions and Organization, 2(1), 78–102. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpo/jou010

- Borglund, T., Frostenson, M., Helin, S., & Arbin, K. (2023). The professional logic of sustainability managers: Finding underlying dynamics. Journal of Business Ethics, 182(1), 59–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-021-05000-1

- Brès, L., Mosonyi, S., Gond, J.-P., Muzio, D., Mitra, R., Werr, A., & Wickert, C. (2019). Rethinking professionalization: A generative dialogue on CSR practitioners. Journal of Professions and Organization, 6(2), 246–264. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpo/joz009

- Cerbone, D., & Maroun, W. (2020). Materiality in an integrated reporting setting: Insights using an institutional logics framework. The British Accounting Review, 52(3), 100876. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2019.100876

- Dahlmann, F., & Grosvold, J. (2017). Environmental managers and institutional work: Reconciling tensions of competing institutional logics. Business Ethics Quarterly, 27(2), 263–291. https://doi.org/10.1017/beq.2016.65

- de Grosbois, D., & Fennell, D. A. (2022). Determinants of climate change disclosure practices of global hotel companies: Application of institutional and stakeholder theories. Tourism Management, 88, 104404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104404

- DiMaggio, P. (1988). Interest and agency in institutional theory. In L. G. Zucker (Ed.), Institutional patterns and organizations culture and environment (pp. 3–21). Ballinger.

- Dunn, M. B., & Jones, C. (2010). Institutional logics and institutional pluralism: The contestation of care and science logics in medical education, 1967–2005. Administrative Science Quarterly, 55(1), 114–149. https://doi.org/10.2189/asqu.2010.55.1.114

- Ertuna, B., Gu, H., & Yu, L. (2022). “A thread connects all beads”: Aligning global CSR strategy by hotel MNCs. Tourism Management, 91, 104520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2022.104520

- Ertuna, B., Karatas-Ozkan, M., & Yamak, S. (2019). Diffusion of sustainability and CSR discourse in hospitality industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(6), 2564–2581. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-06-2018-0464

- Fatima, T., & Elbanna, S. (2023). Corporate social responsibility (CSR) implementation: A review and a research agenda towards an integrative framework. Journal of Business Ethics, 183(1), 105–121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-022-05047-8

- Fong, V. H. I., Wong, I. A., & Hong, J. F. L. (2018). Developing institutional logics in the tourism industry through coopetition. Tourism Management, 66, 244–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.12.005

- Font, X., & Lynes, J. (2018). Corporate social responsibility in tourism and hospitality. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(7), 1027–1042. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1488856

- Gioia, D. A., Corley, K. G., & Hamilton, A. L. (2013). Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia methodology. Organizational Research Methods, 16(1), 15–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428112452151

- Gond, J.-P., & Moser, C. (2021). Critical essay: The reconciliation of fraternal twins: Integrating the psychological and sociological approaches to ‘micro’corporate social responsibility. Human Relations, 74(1), 5–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726719864407

- González-Rodríguez, M. R., Martín-Samper, R. C., Köseoglu, M. A., & Okumus, F. (2019). Hotels’ corporate social responsibility practices, organizational culture, firm reputation, and performance. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(3), 398–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1585441

- Goodrick, E., & Reay, T. (2011). Constellations of institutional logics: Changes in the professional work of pharmacists. Work and Occupations, 38(3), 372–416. https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888411406824

- Greenwood, R., Raynard, M., Kodeih, F., Micelotta, E. R., & Lounsbury, M. (2011). Institutional complexity and organizational responses. Academy of Management Annals, 5(1), 317–371. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2011.590299

- Guix, M., Bonilla-Priego, M. J., & Font, X. (2018). The process of sustainability reporting in international hotel groups: An analysis of stakeholder inclusiveness, materiality and responsiveness. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(7), 1063–1084. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1410164

- Guix, M., & Font, X. (2020). The Materiality Balanced Scorecard: A framework for stakeholder-led integration of sustainable hospitality management and reporting. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 91, 102634. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102634

- Gümüsay, A. A., Claus, L., & Amis, J. (2020). Engaging with grand challenges: An institutional logics perspective. Organization Theory, 1(3), 263178772096048. https://doi.org/10.1177/2631787720960487

- Hotels Magazine. (2015). 325 hotels. Hotels Magazine, July/August. [Retrieved from http://www.hotelsmag.com]

- Høvring, C. M., & Andersen, S. E. (2021). Navigating multidirectional CSR tensions: A micro perspective on CSR middle managerial practice. Academy of Management Proceedings, 2021(1), 12993. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMBPP.2021.12993abstract

- Hunoldt, M., Oertel, S., & Galander, A. (2020). Being responsible: How managers aim to implement corporate social responsibility. Business & Society, 59(7), 1441–1482. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650318777738

- Kiefhaber, E., Pavlovich, K., & Spraul, K. (2020). Sustainability-related identities and the institutional environment: The case of New Zealand owner–managers of small-and medium-sized hospitality businesses. Journal of Business Ethics, 163(1), 37–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-3990-3

- Langley, A., & Ravasi, D. (2019). Visual artifacts as tools for analysis and theorizing. In The production of managerial knowledge and organizational theory: New approaches to writing, producing and consuming theory. Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Lounsbury, M., Steele, C. W., Wang, M. S., & Toubiana, M. (2021). New directions in the study of institutional logics: From tools to phenomena. Annual Review of Sociology, 47(1), 261–280. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-090320-111734

- Luo, X. R., Wang, D., & Zhang, J. (2017). Whose call to answer: Institutional complexity and firms’ CSR reporting. Academy of Management Journal, 60(1), 321–344. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2014.0847

- Madsen, C. U., & Waldorff, S. B. (2019). Between advocacy, compliance and commitment: A multilevel analysis of institutional logics in work environment management. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 35(1), 12–25.

- Noordegraaf, M. (2007). From “pure” to “hybrid” professionalism: Present-day professionalism in ambiguous public domains. Administration & Society, 39(6), 761–785. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399707304434

- Noordegraaf, M. (2015). Hybrid professionalism and beyond:(New) Forms of public professionalism in changing organizational and societal contexts. Journal of Professions and Organization, 2(2), 187–206. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpo/jov002

- Ocasio, W., Thornton, P. H., & Lounsbury, M. (2017). Advances to the institutional logics perspective. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, T. B. Lawrence, & R. E. Meyer (Eds.), The Sage handbook of organizational institutionalism (Vol. 2, pp. 509–531). SAGE Publications.

- Pache, A.-C., & Santos, F. (2013a). Embedded in hybrid contexts: How individuals in organizations respond to competing institutional logics. In Institutional logics in action, part B (Vol. 39, pp. 3–35). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Pache, A.-C., & Santos, F. (2013b). Inside the hybrid organization: Selective coupling as a response to competing institutional logics. Academy of Management Journal, 56(4), 972–1001. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.0405

- Reay, T., & Jones, C. (2016). Qualitatively capturing institutional logics. Strategic Organization, 14(4), 441–454. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476127015589981

- Risi, D., & Wickert, C. (2017). Reconsidering the ‘symmetry’between institutionalization and professionalization: The case of corporate social responsibility managers. Journal of Management Studies, 54(5), 613–646. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12244

- Schaffer, F. C. (2015). Elucidating social science concepts: An interpretivist guide. Routledge.

- Schatzki, T. (2001). Introduction: Practice theory. In T. Schatzki, K. Knorr-Cetina, & E. V. Savigny (Eds.), The practice turn in contemporary theory. Routledge.

- Schneider, A. (2015). Reflexivity in sustainability accounting and management: Transcending the economic focus of corporate sustainability. Journal of Business Ethics, 127(3), 525–536. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2058-2