ABSTRACT

This study aims to investigate the ways in which a particular digital technology, the Interactive Whiteboard (IWB), mediates preschool teachers’ teaching. Over five months in 2017 and early spring 2018, five preschool teachers and 22 children aged 4–6 were video observed. By identifying aspects of IWB as a mediational means, the findings of the study have shed light on the relationship between mediational means and teachers’ mediated teaching actions and mapped what is privileged. This study highlights seven ways that using a particular digital technology, the IWB, informs teachers’ teaching practices. This study, furthermore, maps the possible consequences of using IWB in terms of opportunities and constraints in early education.

Introduction

During the last decade, digital technologies have become an indispensable part of the educational process. The quest for educational excellence has been associated with the drive for teaching using digital technologies (Moss and Jewitt Citation2010). Swedish educational settings are no exception. In line with a similar demand for teaching excellence, the use of digital technologies in preschools has been initiated and underlined by political bodies. The Swedish curriculum, as a political document, has, accordingly, placed great emphasis on the inclusion of digital technologies in both the development and implementation of creative processes (The Swedish National Agency for Education Citation2018). The Swedish preschool curriculum (2018) places particular importance on preschool teachers’ role in providing opportunities to develop children’s digital competence wherein they are expected to develop and conduct educational activities to stimulate and challenge children’s development and learning in goal-oriented processes.

Earlier studies on the use of digital technologies are mostly focused on the ways digital technologies contribute to children’s learning rather on teachers’ teaching (see Gillen and Kucirkova Citation2018; Masoumi Citation2015). This article by examining how interactive whiteboard (IWB) mediates teachers’ teaching turns the focus of attention to teaching in preschool and thereby contributes to our understanding of teaching in the field of early childhood education.

According to The Swedish Media Council (Citation2015) all preschools in Sweden have access to the internet. Two- thirds of this internet use is related to activities with children. A majority of preschools have access to computers and tablet computers. The same report reveals that about 85% of preschools have access to big screen projectors, TVs and IWBs. The same report, particularly, states that more than 20% of the preschools have access to IWB.

The continuing rapid development of digital technologies has created an interesting set of opportunities and challenges for learning and development that has also placed new demands on teachers’ and children’s knowledge and skills (Kearney et al. Citation2018). These technologies have changed the ways teachers and children behave in their everyday lives regarding communicating, entertaining and learning. The ubiquity of the internet and digital technologies has particularly changed their experiences of using the internet (Selwyn Citation2012). The increasing infusion of digital technologies into educational settings, furthermore, has changed the ways teachers communicate with, choose and structure their educational resources and even changed their teaching practices.

As early as the late 1990s and early 2000s, debates began to emerge about the introduction of digital technologies into schools. In Citation2001, for instance, Cuban argued that using digital technologies to their full potential can make teaching and learning processes more efficient and productive. He further stated that using technologies may transform teaching and learning processes and encourage children to participate in educational activities that are more akin to real life. Most importantly, introducing digital technologies is assumed to prepare children’s digital skills, one of the core competencies for the twenty-first century information and knowledge-based society. However, introducing digital technologies, as Cuban (Citation2013) argues, may not magically transform educational practices. It may bring in new forms of inequality, bullying and commercial exploitation which can challenge children’s learning and development process (Selwyn Citation2012).

Therefore, questions about the potential and usefulness of digital technologies in educational settings can be seen as one of the key questions for teachers, stakeholders and policymakers. Preschool teachers play a critical role in integrating digital technologies to change the teaching and learning process for the better (Masoumi Citation2015; Plowman and Stephen Citation2013). There is, however, little knowledge about how these technologies make a difference to teachers’ practices, if at all. There are very few studies done about how digital technologies contribute to teachers’ practices. This study seeks to contribute to current knowledge about how the use of a particular digital technology, IWB, as a teaching artefact, affects preschool teachers’ educational practices.

Drawing on a sociocultural perspective of learning, the aim of this article is to investigate the ways in which IWB, as a teaching artefact, mediates preschool teachers’ teaching. The following more precise research questions were explored in this study:

How do IWBs mediate teaching actions?

What is privileged in the IWB-mediated teaching actions?

Background

IWB is a large touch-sensitive interactive display. This multimodal technology can either be used as a standalone touchscreen computer or a connectable device that attaches the computer’s possibilities with an interactive surface. IWB, unlike other digital technologies, has been seen as a teaching tool rather than as a learning tool. The features of IWBs, including multimedia/multimodal presentation, large display, animation, interactivity, indefinite storage and quick retrieval of educational resources, have repeatedly been highlighted in the literature (Higgins et al. Citation2012; Miller and Glover Citation2007). Deaney, Chapman, and Hennessy (Citation2009) for example, highlight the value of annotated IWB slides and other saved resources which can draw on students’ shared experiences and previously co-constructed understandings to promote the learning and teaching process. Ward et al. (Citation2016) posit that IWBs provide new types of opportunities to link children’s learning experiences, fullfille the given task collaboratively and create meaningful learning environments.

Promoting flexibility in the structure of a variety of teaching resources was another opportunity in which IWB can help teachers to create multimodal stimuli for whole-class discussions (Mercer, Hennessy, and Warwick Citation2010). Morgan (Citation2010) underlines the IWB’s potential to create playful and interactive experiences in teaching situations. Mercer, Hennessy, and Warwick (Citation2010) draw attention to the IWB’s manipulative potentials that can be stored and retrieved for future use. In the same vein, a number of the studies underline the ways that IWB can enhance teaching effectiveness and facilitate different teaching styles (see Harlow, Cowie, and Heazlewood Citation2010; Miller and Glover Citation2007). The IWB’s features can provide a range of possibilities to mediate teachers’ ways of teaching (Gillen and Kucirkova Citation2018; Heemskerk, Kuiper, and Meijer Citation2014).

Other studies, however, have found there can be challenges when using IWB in educational settings. Cutrim Schmid (Citation2008) highlights the difficulty of preparing teachers to use IWB in their teaching activities. Some of the studies claim that expectations of what IWB can bring to educational practices have been high, but very few studies can report concrete results. For instance, Kearney and Schuck (Citation2008) argue that using IWB does not transform teachers’ ways of teaching. They claim that the IWB simply replicates current educational procedures.

By examining the possible impact of IWB on students’ participation in teaching activities, Smith et al. (Citation2005) conclude that, despite the introduction of IWB, the quality of such participation did not significantly improve. In a similar vien, Cabus, Haelermans, and Franken’s (Citation2017) experimental study shows that the teachers’ use of IWB in their teaching has a small effect on students’ math proficiency. Zevenbergen and Lerman (Citation2008) underline a number of undesirable aspects of using IWBs in educational settings. They were seen to minimise interactions between students and teacher and among students themselves, promote teacher talk and facilitate a high level of teacher control. They further argue that IWB use can reduce opportunities to connect learners with their everyday lives and provide fewer autonomous learning opportunities. In the same vein, Morgan (Citation2010) argues that using IWB in the classroom supports the teachers’ level of control, tending to more instructional approaches.

The literature thus displays a diverse picture about the use of IWB in educational settings. While the literature addresses the possible opportunities that IWB can offer to transform educational practices, it also reveals the possible challenges that may come with using IWB in educational settings. There are hardly any study that empirically explore the ways digital technologies inform teachers’ teaching. This paper contributes to the current knowledge about how the use of a particular digital technology, the IWB, mediates preschool teachers’ teaching practices.

Swedish preschool

Increasing change in society has dramatically contributed to the way we live, including the fact that now, almost all children in Sweden participate in preschool activities. Swedish preschools are based on a model titled educare. This model provides a conscious balance between children’s self-generated play-based activities and preschool teachers’ structured, educational ones. Having a holistic perspective, educare introduces a framework where teaching, play and care are integrated in order to develop children’s cognitive, social and emotional learning (Sheridan, Sandberg, and Williams Citation2015).

Preschool teaching was defined for the first time in the Swedish Education Act (SFS Citation2010: 800), describing it as a goal-oriented process under the supervision of a teacher to develop children’s abilities. Accordingly, teaching is defined as a goal-driven process – preschool curriculums should have goals to strive for – to lead children to become interested and engaged in a specific content and/or phenomenon (Pramling and Wallerstedt Citation2019). Teaching in preschool, however, is a complex concept in preschool didactics (Pramling and Wallerstedt Citation2019).

IWB use through a sociocultural lens

The theoretical perspective in this article is built upon the assumption that learning is a constant social process which takes place in cultural contexts (Vygotsky Citation1978). Human interaction with the outside world is mediated through different tools (Vygotsky Citation1978). These tools, which can be physical or psychological, are shaped by the participants of discursive practices and developed into structures for interaction in different situations. Enabling us to tackle and solve problems, these tools can extend both our physical and mental abilities.

By making the distinction between mediational means and mediated actions, Wertsch (Citation1998) demonstrates both the role which tools play in extending our abilities and the process by which they do this. Mediational means, as Wertsch (Citation1991, 119) puts forward ‘are inherently related to action. Only by being part of an action do mediational means come into being and play their role. They have no magical power in and of themselves’. The importance of these technological tools becomes truly apparent when they are unavailable to us (Wertsch Citation1998). The idea of a person-acting-with-meditational-means (Wertsch Citation1991) both expands the view of what a person can do and suggests that a person might be constrained by their situated and mediated actions. This leads to the suggestion that the ways we act in a situation or solve a problem is informed by the tools at our disposal.

Drawing on sociocultural theorising, teaching and learning are seen as situational and social processes which are operationalised by mediational means. Thus, mediational means can extend our opportunities. Wertsch (Citation1991) exemplified this extension by making a comparison with a blind man’s stick. The stick ‘goes beyond the skin’ and becomes a part of the blind man’s body, expanding his ability to understand his surroundings and move forward. The ‘agent of mediated action is seen as the individual or individuals acting in conjunction with mediational means’ (Wertsch Citation1991, 33). The concept of mediated action addresses the relationship between the mediational means, that is, the IWB, and the agent who performs the action, that is, the teacher. The mediational means shape the actions and therefore cannot be separated from mediated actions (Wertsch Citation1991). Mediation provides an analytical frame in which to understand how IWB can mediate teachers’ teaching actions in this study.

To place the IWB-mediated teaching action at the centre of my analysis, like Wertsch (Citation1991) I use privilege as a neutral concept, free from any bias and intended to address both negative and positive results of using a digital artefact. The use of this concept helped me to be open to explore the possible outcomes of a mediated teaching action – both restrictions and/or possibilities – when a specific aspect of IWB mediates teachers’ teaching actions.

Data collection and analysis

In order to understand how IWB mediates teachers’ teaching actions and what is privileged in IWB-mediated teaching actions, preschool teachers using IWB in their preschool pedagogical practices were observed. Finding preschools where teachers actively used IWB in their teaching practices and willing to participate in the study was not easy. Three preschools were found in which the use of IWB was part of their educational practices; however, two of them were not up to participating in the study.

The fieldwork continued for five months and included observations of five preschool teachers and 22 children aged four-six years old in a preschool class in a city in the central part of Sweden. The participating teachers had had different levels of pedagogical and technological expertise. They, however, had no formal education about the use of IWB in early childhood education and thus were essentially early adopters. Teaching sessions in mathematics were chosen to provide comparable teaching environments in order to explore how the use of the IWB mediated preschool teachers’ teaching.

The preschool teachers planned and conducted their teaching sessions using IWB without the researcher interventions. The participating teachers were named A, B, C, D, and E. To gather the observational data a camera was placed three metres away from the IWB in the back corner of the classroom. All activities during the teaching situations were recorded and both the teachers and the children working with the IWB were observed. Eighteen teaching situations comprising a total of 306 min were video recorded.

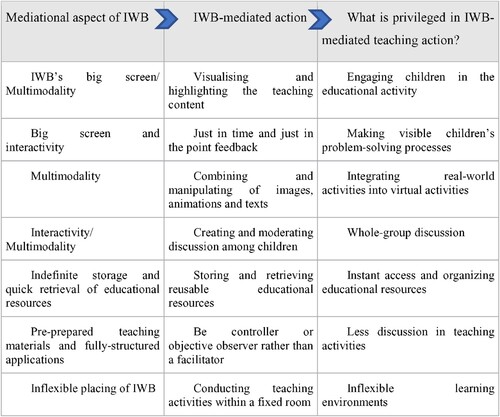

The number of observations were not determined in advance, but the observations were continued until a point where I got impression that I had sufficient empirical evidence. The video recorded teaching situations were reviewed and critical episodes identified and transcribed. The episodes were reviewed and analysed in detail. The focus was on the manner in which IWB mediated teachers’ teaching actions (see , as an illustration of the analysis procedure).

The following steps details the study’s analysis procedure:

Mediation in this article is an analytical tool used to understand how the IWB as a mediational means mediates teachers’ teaching actions. The mediational aspects of IWBs (a specific aspect of IWB) were initially identified, resulting in seven mediational aspects.

The next step was to identify how these mediational aspects of IWBs mediated teachers’ teaching actions. In this phase teachers’ actions in relation to the specific aspect of IWB were specified.

By mapping the relationship between mediational means and teachers’ teaching actions, the privileged IWB-mediated actions were identified.

Ethical considerations

The ethical considerations were made in accordance with the Swedish ethical regulations for research (The Swedish Research Council Citation2017). The participants were, accordingly, informed orally and in writing about the aim and design of the study, what their participation would involve and the terms and conditions of their contribution. A protocol was developed that provided a framework for recording, storing, analysing, disseminating and future use of the video-recorded data.

Thereafter, the written consent of both the teachers and the children’s guardians to take part in the study was sought and received. Furthermore, the preschool children’s consent to participate in the study and to be video recorded was sought by explaining the aim of the study and asking them if they would like to participate in the study. The children were also informed that they could cancel their participation in the study at any time.

Results

This section shows how teachers’ teaching actions are meditated by mediational aspects of IWB and what is privileged in the IWB-mediated teaching actions.

outlines the seven ways that IWB-mediated teaching actions privilege teaching practices. What is privileged can be desirable/undesirable and intended/unintended consequences of using IWBs in preschool educational practices and illustrate how IWBs inform preschool teachers’ teaching. For instance, IWB’s big screen and multimodality as mediational aspects mediated teachers’ actions through visualising and highlighting the given teaching content. This visualisation and highlighting content on IWB’s big screen (which privileges teachers’ teaching practices) could engage children in various teaching situations.

Engaging children in educational activities

Two mediational aspects of IWB found to mediate teaching actions were the big screen and multimodality. The identified mediated teaching action here was visualizing and highlighting the teaching content for children. These IWB-mediated teaching actions privilege engagement of the children in teaching situations.

Manipulating objects, colouring, animating, dragging and dropping are an aspect of IWB multimodality. This aspect makes it possible for teachers to deliver a range of opportunities to highlight the desired teaching objects and bring them into view.

In most of the observed teaching situations, the big screen and multimodality of the IWB provide teachers with opportunities to visualise and highlight the intended content. Teachers highlighted the given objects through colouring, dragging and moving, and in so doing promoted the engagement of the whole group of children in the specified teaching activity. For instance, in a teaching situation about size and order, three dimensional giraffes in three different sizes were displayed on the screen. At the bottom of the page there was a black line where children were asked to place the given objects in order according to their size.

Excerpt 1. Teacher E, size and order.

As indicated in the excerpt above, teacher E makes use of the IWB’s big screen and multimodal resources to visualise the intended learning content. By highlighting the visualised content on the big screen, the teacher engages all the children in the activity while addressing challenging questions about animals, the differences between them and the ways in which they can be classified. This is particularly illustrated in Excerpt 1, where a child is invited to classify the given animals according to their size.

Making visible children’s problem-solving processes

The mediational aspects of IWB found to mediate teaching actions were the big screen and interactivity. The identified mediated teaching action here was providing just in time and just in the point feedback to both individuals and the whole group. This IWB-mediated teaching action privileges making visible children’s problem-solving processes. Teachers’ physical proximity to the IWB’s screen makes it possible assist children to explore and fulfil the intended activity and help them with technical issues. Teachers’ feedback takes different forms including affirming, asking questions, challenging children’s thoughts or solutions, and confirming.

In particular, three forms of feedback were noticed in the observed situations: (1) feedback from teacher to children using IWB; (2) feedback from child to child using IWB; and, (3) immediate feedback from the IWB’s interactive display to children and teachers. For instance, in the following excerpt, teacher B works with a group of children using an application about numeracy and order. The application displays the numbers from zero to nine on the board along with many big and small dots. The children are expected to drag and match the number of dots with the given number.

Excerpt 2. Teacher B, number and order.

As highlighted in this excerpt, the IWB’s big screen enables teacher B and even other children in the group to follow the entire problem-solving process and the way child 2 explores the given task. This privileges teachers’ opportunities to provide concrete and just on time and point feedback to children.

The IWB’s big screen aspect further mediates the ways children support each other’s reflections. This contribute to create a learning environment wherein children support and give feedback to each other’s actions.

Excerpt 3. Teacher A: Numbers and Order.

As exemplified in the above-mentioned excerpt, the IWB’s big display and its interactivity mediates the ways children support and provide feedback to each other.

Finally, the interactivity aspect of IWB provides direct response to children’s actions. In some teaching situations, IWB provides direct feedback when children fulfil an activity or when a specified object is handled. Depending on the application, the IWB can offer positive feedback, such as applauding, or negative feedback, such as the disappearance/reappearance of wrong/right answers.

Integrating real-world and virtual activities

A mediational aspect of IWB found to mediate teaching actions was its multimodality. The identified mediated teaching actions were the combining and manipulating of images, animations and texts from a broad range of sources directly on the IWBs screen. These IWB-mediated teaching actions privilege integrating real-world activities into virtual activities.

In a teaching situation about measurement, for instance, teacher E asked children to measure their height with plastic unit cubes. The teacher and each of the children measured their height with unit cubes, then each of them showed his/her height on the IWB using a staple diagram. In this activity each child was able to choose their own distinct colour for their staple. Using drag and drop the children ordered their unit staple on the IWB. Then, indicating their staples, each one had the opportunity to compare and relate their height to others. Mixing virtual and physical activities on the IWB in this way allows preschool teachers to connect and visualise these abstract concepts by assigning each coloured staple according to the children’s height.

Whole-group discussion

The interactivity and multimodality aspects of IWBs was found to mediate teaching actions throughout the conducted observations. One kind of mediated teaching action was creating and moderating discussion among children wherein teacher and children can explore problems together. These mediated teaching actions were found to privilege whole class dialogue.

In one application, for instance, four different animals are placed over a thick line. Under this line there is a teddy bear on the left side and a recycle bin on the right side. Upon clicking the teddy bear, an instruction appears asking, ‘which object should be removed? Find one object which is different from the others and throw it in the bin’. Whenever the right object is dragged and thrown in the bin, the object disappears, but when a wrong object is thrown away, it remains in the bin.

Teacher B uses the IWB’s multimodality to put the different objects over the bin, not in it. Such multimodality makes it possible for teacher B to challenge whole-class dialogue about characterising qualities among the given animals. This also contributes to solving, and even defining, problems differently. As teacher B highlights, she does not care about right or wrong answers. Rather, she wants to understand how children think and the motivations behind their answers. Having a teacher pointing to pictures of the animals on the IWB challenges children to characterise animals based on their different qualities such as number of legs, where they live and whether they are wild or domesticated. In another teaching situation, teacher B works with another version of the application about classifying animals.

Excerpt 4. Teacher B: Classifying animals.

As indicated in excerpt 4, the IWB’s multimodality and interactivity promote discussion among children wherein children and teacher can explore and criticise each other’s thoughts based on what happened on the board. Teacher B makes sure that all of the children actively participate in the discussion and that they support each other’s thoughts and ideas.

Instant access and organising educational resources

The IWB’s indefinite storage and quick retrieval of educational resources aspect was found to mediate teaching actions. The identified mediated teaching action here was storing and retrieving reusable educational resources. Providing a great number of teaching resources, IWBs offer a variety of digital experiences collected in one place which privileges instant access and organising teaching resources. These resources are developed and saved on the IWB and can be reused with different groups of children (see pictures below).

The collected teaching materials were categorised in folders on the IWB. Some of the folders, for example, those used in the observed teaching situations, were dedicated to themes such as numeracy, whole and part, order and size, classification, positioning, numerical values of money, geometrical shapes, pairing and measurement. In alignment with the intended learning outcomes, preschool teachers easily selected the associated teaching activities simply by clicking on the respective folder on the IWB and opening the relevant file. This allowed for the use/reuse of the developed teaching resources with different groups of children.

Having all of the necessary teaching resources on the IWB, in a form that can easily be reused and further developed, mediates what and how preschool teachers structure their teaching activities. Thus, preschool teachers do not need to bring additional teaching resources to the classroom or prepare educational materials once they have arrived. This IWB-mediated teaching action makes it possible to shift easily from task to task and to move on to the next activity with only a few pauses.

Less discussion in teaching activities

The pre-prepared teaching materials and fully-structured applications are another mediational aspect which mediates teachers’ teaching actions. The identified mediated teaching action here was the teacher’s role as a controller or objective observer rather than as a teacher. This IWB-mediated teaching action privileges less discussion between teacher and children and among children.

Fully-structured applications provide the right answer based on a predefined schema. Such automated responses to children’s interactions with the activities, mediate the teacher’s teaching actions to act as a controller or objective observer rather than as a teacher. The teacher’s role is, accordingly, limited to approval or rejection of the children’s responses. In a teaching situation about measurement, for instance, the children were asked to find the tallest or shortest. As soon as the children clicked on the correct answer (a picture), two hands appeared, applauding. Whenever children clicked the wrong answer, a cross appeared over the picture. The following excerpt exemplifies the ways that an automated answer from the IWB constrains the teaching.

Excerpt 5. Teacher D, size and order.

The immediate response given by the application, as noted in excerpt 5, closes down possible conversations in which children’s thinking could be challenged. In working with such fully-structured applications, the preschool teacher’s role is limited to basic group control functions such as inviting and guiding children to the board and choosing the order in which children carry out the activity.

Inflexible learning environments

The inflexible placing of IWB was another mediational aspect which was found to mediate teachers’ teaching actions. The identified mediated teaching action here is conducting teaching activities within a fixed room / learning environment. This IWB-mediated teaching action privileges fixed and inflexible learning environments.

In the studied preschool there was one single IWB which was installed in a large area. There were more than seven small working spaces in this area. A number of the spaces were separated by thin partitions. In each space, a group of children were working with their teachers. Each group could hear and see the activities of the others, as children ran, talked and passed through the room. The children, as a result, could easily be distracted by other groups’ activities. In one instance, a group of children were working with building blocks when suddenly one block was thrown into the space where another teacher and her group of children were working with the IWB. These circumstances limit the teacher’s opportunities to create calm and focused learning environments.

Discussion

Over the past two decades the digitalisation of preschools has been in a state of flux. On the one hand, the literature demonstrates the opportunities presented by digital technology and the ways digital technology can transform teachers’ educational practices. On the other hand, there are voices that underline the possible challenges and harms which the introduction of digital technology can directly or indirectly cause. Digitalising in preschool, accordingly, is either considered a panacea, which can create opportunities to transform early education and prepare children for the information society, or a threat which can cause serious problems for children’s development. The key question is how – not if – using digital technologies can contribute to preschool teacher teaching. Teaching with technologies in preschool, however, is very different from the way it is used at primary or secondary school.

This study in reference to the identified gaps in the literature aims to expand and deepen our understanding of the ways in which a particular digital technology, the IWB, mediates preschool teachers’ teaching in its actual uses in preschools. By approaching the IWB’s features as mediational means, the study has shed light on the relationship between mediational means and teachers’ mediated teaching actions and mapped those that are privileged. The seven ways that IWB-mediated teaching actions privilege teaching practices display desirable/undesirable and intended/unintended consequences of using IWBs in preschool educational practices and illustrate how IWBs inform preschool teachers’ teaching. Thus, preschool teachers need to critically consider those aspects and/or applications of the IWB in educational settings that might, through their use, lead to any intended/unintended consequences.

The starting point of this article was the ongoing debate about if and how IWBs transform preschool teachers’ goal-oriented teaching practices. It is not surprising that the IWB as a teaching artefact has changed preschool teachers’ teaching more than other small screen devices. However, this change mostly depends on the IWBs’ features, its application and how it is pedagogically exploited in preschool educational practices. The findings of the study, for instance, suggest that the fully structured applications and pre-prepared teaching materials contribute to increased teacher control of the process of teaching and learning. Using fully structured applications can change not only the possible communications and interactions between teachers and children and among children, but can also minimise teachers’ opportunities to motivate, challenge and take into account children’s needs and perspectives (Zevenbergen and Lerman Citation2008). Further, in their study, Miller and Glover (Citation2007) clearly show that using IWB can promote a teacher-centred approach. Consistent with the International Society for Technology in Education Standards for Educators (ISTE Citation2017), it can be said that teachers cannot simply rely on marketed applications and pre-prepared digital materials, but they need to design learner-driven activities and environments that recognise and accommodate children’s needs and interests.

The findings of this study, however, reveal some instances that show teachers’ ways of using IWB can promote children’s engagement in the teaching activities. The observations provide examples of pedagogies where multimodal aspects of IWB mediate teachers’ teaching actions to create play-like activities. In these play-like activities, the teaching and learning activities are provided within the frame of play where IWBs support manipulation of activities to do ‘what if’ scenarios on IWBs big screen. This is aligned with the current Swedish curriculum (The Swedish National Agency for Education Citation2018, 14) which gives prominence to play, noting that ‘the preschool should provide each child with the conditions to develop curiosity, creativity and a desire to play and learn’. Unlike a small screen device – such as a tablet, and now widely available in Swedish preschools – my findings demonstrate that IWBs support both group and individual teaching, allowing teachers to encourage interaction among children and between teacher and children. However, the use of IWB in goal-oriented preschool practices mostly depends on the ways the different features of the IWB are used to create opportunities for teachers’ teaching actions.

The results of the study confirm that teachers’ physical proximity to the IWB’s large display enhances teachers’ opportunities to provide just in time feedback. Providing feedback to children using the IWB in terms of questioning to elicit a children’s thoughts (Initiation-Response-Feedback pattern) has been discussed in the previous literature (Mercer, Hennessy, and Warwick Citation2010). My study’s findings introduce two more patterns of feedback mediated by the IWB. The interactive nature of the IWB makes it possible to provide direct and automated feedback when teachers or children fulfil an activity or a specified object is handled on the IWB. The IWBs automated and direct feedback is articulated in a variety of ways, including positive feedback and negative feedback. The IWB’s big screen can further enhance children’s opportunities to provide feedback to each other’s work in the process of problem solving.

The findings of this study draw attention to how preschool teachers’ teaching can be affected by a specific digital technology now commonly used in early education. Mapping the consequences of using these technologies in terms of possible opportunities and constraints can contribute to ongoing discussions about how digital technologies can be integrated into preschools’ educational practices in alignment with the current Swedish preschool curriculum. The findings are also important since the results of this study can contribute to the strengthening of teachers’ digital competencies. What is significant from a Swedish perspective is that digital technologies are becoming an important part of preschools’ educational practices. The integration of these digital technologies, as this research shows, serves to transform preschool teachers’ existing teaching practices rather than entirely replacing them.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Cabus, Sofie, Carla Haelermans, and Sonja Franken. 2017. “SMART in Mathematics? Exploring the Effects of in-Class-Level Differentiation Using SMARTboard on Math Proficiency.” British Journal of Educational Technology 48 (1): 145–161. doi:10.1111/bjet.12350.

- Cuban, Larry. 2001. Oversold and Underused : Computers in the Classroom. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Cuban, L. 2013. Inside the Black Box of Classroom Practice: Change Without Reform in American Education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Cutrim Schmid, Euline. 2008. “Potential Pedagogical Benefits and Drawbacks of Multimedia Use in the English Language Classroom Equipped with Interactive Whiteboard Technology.” Computers and Education 51 (4): 1553–1568.

- Deaney, Rosemary, Arthur Chapman, and Sara Hennessy. 2009. “A Case-Study of One Teacher’s Use of an Interactive Whiteboard System to Support Knowledge Co-Construction in the History Classroom.” Curriculum Journal 20 (4): 365–387. doi:10.1080/09585170903424898.

- Gillen, Julia, and Natalia Kucirkova. 2018. “Percolating Spaces: Creative Ways of Using Digital Technologies to Connect Young Children’s School and Home Lives.” British Journal of Educational Technology 49 (5): 834–846. doi:10.1111/bjet.12666.

- Harlow, Ann, Bronwen Cowie, and Megan Heazlewood. 2010. ““Keeping in Touch with Learning: The Use of an Interactive Whiteboard in the Junior School.” Technology, Pedagogy and Education 19 (2): 237–243. doi:10.1080/1475939X.2010.491234.

- Heemskerk, Irma, E. Kuiper, and J. Meijer. 2014. “Interactive Whiteboard and Virtual Learning Environment Combined: Effects on Mathematics Education.” Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 30 (5): 465–478. doi:10.1111/jcal.12060.

- Higgins, Steve, Emma Mercier, Liz Burd, and Andrew Joyce-Gibbons. 2012. “Multi-Touch Tables and Collaborative Learning.” British Journal of Educational Technology 43 (6): 1041–1054. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8535.2011.01259.x.

- International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE). 2017. ISTE Standards for Educators: A Guide For Teachers And Other Professionals. Accessed 15 April 2019 https://www.iste.org/standards/for-educators.

- Kearney, Matthew, and Sandy Schuck. 2008. “Exploring Pedagogy with Interactiue Whiteboards in Australian Schools.” Australian Educational Computing.

- Kearney, Matthew, Sandy Schuck, Peter Aubusson, and Paul F. Burke. 2018. “Teachers’ Technology Adoption and Practices: Lessons Learned from the IWB Phenomenon.” Teacher Development 22 (4): 481–496. doi:10.1080/13664530.2017.1363083.

- Masoumi, Davoud. 2015. “Preschool Teachers’ Use of ICTs: Towards a Typology of Practice.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood 16 (1): 5–17. doi:10.1177/1463949114566753.

- Mercer, Neil, Sara Hennessy, and Paul Warwick. 2010. ““Using Interactive Whiteboards to Orchestrate Classroom Dialogue.” Technology, Pedagogy and Education 19 (2): 195–209. doi:10.1080/1475939X.2010.491230.

- Miller, Dave, and Derek Glover. 2007. “Into the Unknown: The Professional Development Induction Experience of Secondary Mathematics Teachers Using Interactive Whiteboard Technology.” Learning, Media and Technology 32(3): 319-331. doi:10.1080/17439880701511156.

- Morgan, Hani. 2010. “Teaching with the Interactive Whiteboard: An Engaging way to Provide Instruction.” Focus on Elementary 22 (3): 3–7.

- Moss, Gemma, and Carey Jewitt. 2010. “Policy, Pedagogy and Interactive Whiteboards: What Lessons Can Be Learnt from Early Adoption in England?” In Interactive Whiteboards for Education: Theory, Research and Practice. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-61520-715-2.ch002.

- Plowman, Lydia, and Christine Stephen. 2013. “Guided Interaction: Exploring How Adults Can Support Children’s Learning with Technology in Preschool Settings.” Hong Kong Journal of Early Childhood 12 (1): 15–22.

- Pramling, Niklas, and Cecilia Wallerstedt. 2019. “Lekresponsiv undervisning – ett undervisningsbegrepp och en didaktik för förskolan.” Forskning om undervisning och lärande 7 (1): 7–22.

- Selwyn, Nils. 2012. Skolan och digitaliseringen: Blir utbildningen bättre med digital teknik. Göteborg: Daidalos.

- SFS. 2010. 800. “Skollag (Education Act).” Government Offices of Sweden. Accessed November 12, 2018. http://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokumentlagar/dokument/svenskforfattningssamling/skollag2010800_sfs-2010-800#K8.

- Sheridan, Sonja, Anette Sandberg, and Pia Williams. 2015. Förskollärarkompetens i förändring. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Smith, Heather J, Steve Higgins, Kate Wall, and Jen Miller. 2005. “Interactive Whiteboards: Boon or Bandwagon? A Critical Review of the Literature.” Computer Assisted Learning 21: 91–101. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2729.2005.00117.x.

- The Swedish Media Council. 2015. Kids & Media”. Accessed September 24, 2019. Stockholm: https://statensmedierad.se/download/18.126747f416d00e1ba946903a/1568041620554/Ungar%20och%20medier%202019%20tillganglighetsanpassad.pdf.

- The Swedish National Agency for Education. 2018. Revised Curriculum for the Preschool. Stockholm: Skolverket.

- The Swedish Research Council. 2017. Good Research Practice. Stockholm: Skolverket.

- Vygotsky, Lev Simkhovich. 1978. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge: Harvard University.

- Ward, Jennifer, Stephanie Branson, Megan D Cross, and Ilene R Berson. 2016. “Exploring Developmental Appropriateness of Multitouch Tables in Prekindergarten: A Video Analysis.” Journal of Research on Technology in Education 48 (3): 227–238. doi:10.1080/15391523.2016.1175855.

- Wertsch, J. V. 1991. Voices of the Mind: A Sociocultural Approach to Mediated Action. Cambridge: MA: Harvard University Press.

- Wertsch, James V. 1998. Mind as Action. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Zevenbergen, Robyn, and Steve Lerman. 2008. “Learning Environments Using Interactive Whiteboards: New Learning Spaces or Reproduction of Old Technologies?” Mathematics Education Research 20 (q): 108–126.