ABSTRACT

This doctoral research addressed the dearth of research focussed on childminding in Ireland, despite its significant role in national childcare provision. One overarching aim was to explore childminders’ pedagogy. The research was conducted within the theoretical framework of Ecocultural Theory (ECT) against the backdrop of Irish Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) policy on the eve of mandatory regulation of childminding. A mixed method approach was adopted, using the Ecocultural Family Interview for Childminders (EFICh) , including participants’ photographs, a case study survey, researcher field notes and holistic ratings. (Tonyan, Holli A. 2017. “Opportunities to Practice What Is Locally Valued: An Ecocultural Perspective on Quality in Family Child Care.” Early Education and Development 28: 727–744. doi:10.1080/10409289.2017.1303304). The research documents a previously unidentified cultural model of pedagogy among childminders, Real Life Learning, in which the primary goal is to explore learning opportunities presented by real life experiences as they arise. The childminder prioritises flexible, child-led, relationship-driven nurture and learning emerging from everyday experiences in enriched home and outdoor environments as well as within the local community. To engage Irish childminders into the future sustainably, any proposed system of regulation and supports should be aligned with this Real Life Learning model.

Introduction: childminding in Ireland

Home-based childcare provides the largest source of non-parental childcare in Ireland (29%): an estimated 10% of children in Ireland from infancy to 12 years of age receive care from paid professional childminders (or family day carers), and a further 3% of children are with paid relatives (Central Statistics Office (CSO) Citation2017). However, national Early Years Regulations (Department of Children and Youth Affairs (DCYA) Citation2016) exempt childminders caring for three or fewer unrelated preschool children, and the new School Age Services register also exempts childminders caring for up to six children of any age (DCYA Citation2018b). This effectively excludes almost all paid childminders from the national ECEC system. In 2021, out of an estimated 15,000–33,000 childminders, (DCEDIY Citation2021, DCYA Citation2018a, Citation2019a) there were 77 childminders registered with Tusla, the national body responsible for the registration and inspection of ECEC.

There have been many calls for the proportionate regulation of childminding, appropriate for a lone worker in a home based setting (Daly Citation2010), and the Government is moving towards mandatory regulation of paid childminding (DCEDIY Citation2021, DCYA Citation2019b). It is vital that the unique nature of childminding is documented in order to develop a sustainable regulatory and support system, which honours this particular form of Early Childhood Education and Care [ECEC].

Research into childminding

The use of childminding is widespread internationally; however, childminding remains relatively under-researched in scope and in focus (Urban et al. Citation2011; Ang, Brooker, and Stephen Citation2016). Landmark studies which focused on childminding (Mooney and Statham Citation2003) have identified indicators of quality in childminding settings, such as regulation (Davis et al. Citation2012), education (Bauters and Vandenbroeck Citation2017), employment status (Letablier and Fagnani Citation2009), and support systems (Brooker Citation2016). Nonetheless, most childminding in Europe and the USA operates in the informal sector (Child in Mind Citation2017; Tonyan, Paulsell, and Shivers Citation2017). Moreover, researchers consider that few quality measures have effectively captured the potential strengths of childminding (Bromer, McCabe, and Porter Citation2013), and research documenting childminding praxis and pedagogy on the ground is very rare (Freeman Citation2011).

Theoretical framework

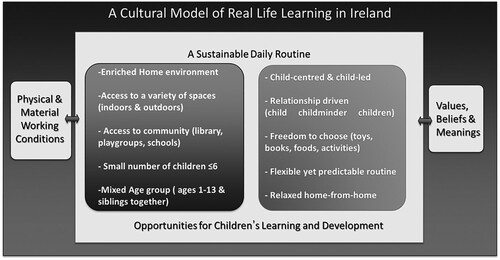

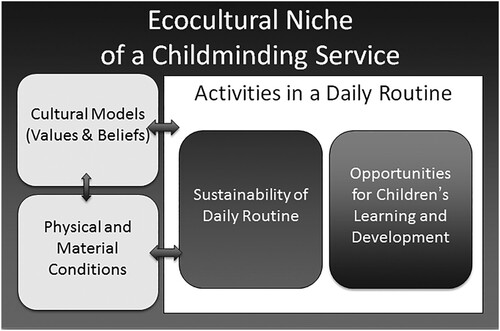

The current study in Ireland documents the daily lives and routines of childminders in the framework of Ecocultural Theory (ECT) (Tonyan Citation2015). According to ECT, in order to thrive, childminders, parents and children will make adaptations in their niche in ways that are meaningful to them in terms of their beliefs and values; congruent with the needs and characteristics of family members and service users; and sustainable for relatively long periods of time, given the constraints and opportunities of all the families involved. From an ecocultural perspective, childminding can be understood as a home-based ecological niche in which the childminder works together with children, their own family, children’s families and assistants to negotiate the project of raising children (Tonyan Citation2015, Citation2017). Since the culture of early care is not an abstract concept, but becomes visible in everyday activities (Rogoff et al. Citation2005), ECT uses the lens of the daily routine in the niche in order to describe specific cultural models (Gallimore, Goldenberg, and Weisner Citation1993) ().

Figure 1. Elements of an ecocultural niche adapted from Savage and Tonyan Citation2015.

Cultural models

Ecocultural research seeks to describe cultural models, defined as ‘presupposed, taken-for-granted models of the world that are widely shared … by the members of a society … ’ (Holland and Quinn Citation1987, 4). Situated in the real physical and material conditions of a particular ecology (Tonyan Citation2015, Citation2017), they are shaped by beliefs reflected in religion, art, music, games and play (Weisner and Hay Citation2015). These culturally-based models of how life should be are usually only partially shared and articulated, yet they shape our scripts and routines of how children should be raised in socially organised ways (Rogoff et al. Citation2005). In this sense, cultural models form developmental pathways by which children learn for adaptation to life (Weisner Citation2002).

Methodology

The research reported in this article forms part of a doctoral study on professional childminding in Ireland. The broader study included a quantitative survey of attitudes towards professionalisation (O’Regan, Halpenny, and Hayes Citation2019), which, in turn, generated a focus on documenting childminding in practice (O’Regan, Halpenny, and Hayes Citation2020). It is this latter focus which is also addressed in the present article. Using a semi-structured interview, the Ecocultural Family Interview for Childminders (EFICh), specifically adapted to capture the ecocultural features of childminding in Ireland. The original Ecocultural Family Interview (Weisner, Bernheimer and Martini Citation2005) focussed on a family’s daily routines as these develop within their ecocultural niche. Since a childminding niche contains multiple families and operates as a business, the EFI was adapted, first for use in childminding research in California (California Child Care Research Partnership (CCCRP) Citation2014). In collaboration with a researcher from the CCCRP, the research tools were tailored for the Irish ECEC context and Hiberno-English usage (e.g. family childcare = childminding).

The EFICh comprises several components are: first, the semi-structured, conversational interview; second, childminder photographs illustrating their daily practice used as prompts in the interview, and thirdly, field notes of researcher observations of the home environment, and interactions between the childminder and the children. In addition, a background survey gathered information about the family’s economic circumstances, the childminder’s reported levels of agency, their education level, and views on early childhood.

Two visits were made to each setting: an initial visit to explain the research, deliver the background survey, and conduct a brief observation, and a second visit, during which an EFICh interview of approximately 1–1.5 h was conducted. Subsequently, holistic ratings were completed by the researcher for each childminder based on what they valued, enacted and evaluated in relation to four thematic areas: Cultural Models, Sustainability of Daily Routines, Service Needs and Use and Quality Improvement, Advocacy and Complexity, with each rating justified by supporting vignettes drawn from the field notes or the interview.

Using protocols developed for the California Child Care Research Partnership (Tonyan Citation2015), childminders were initially rated according to fit with two cultural models identified in California, Close Relationships and School Readiness (Tonyan Citation2017) as High, Medium or Low. To receive a High rating, the childminder must value a model in what she says, enact it in her daily routine activities, and see (or evaluate) its impact on the children’s outcomes in some way. A Medium rating means the childminder partially values, enacts or sees that particular model, while a Low rating means that there is little or no evidence of valuing, enacting, or seeing the model.

Subsequently, the data were coded using Dedoose®, a web-based application for analysing mixed method research with text, photos, audio, videos, and spreadsheet data (Salmona, Lieber, and Kaczynski Citation2019). This allowed for a qualitative analytic process of structured discovery, ‘during which analytic strategies remained open to unexpected processes and patterns while focusing on project-specific topics’ (Weisner Citation2014, 167). This analytic approach explores patterns through close, iterative listening, reading, and observing of the sample data, guided by project specific questions.

Ethical considerations

This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of Technological University Dublin in accordance with its policies and procedures. All participants were given full and accurate information regarding the background, nature, purpose, and outputs of the research to allow them to make an informed decision to participate or withdraw at any stage. Anonymity and confidentiality were guaranteed regarding any information disclosed; participants’ names in this article are fictional. No observations of individual children were conducted, and all photographs used as prompts during interviews were shared with parental consent. Children's identifying features were removed to ensure anonymity where necessary, and no photos of children were retained for use by the researcher afterwards.

Limitations of study

Since the research was conducted with a small, self-selecting sample of professionalised childminders, it may reflect primarily the views of childminders who were more confident about coming forward to participate. Caution should be exercised in applying the findings to Irish childminders in general. As this investigation was the work of a sole researcher, the possibility of interpretation bias must be acknowledged.

Profile of study participants

In total, 17 childminders participated in the research: only two were registered with Tusla, the national agency responsible for childcare, while 15 were members of Childminding Ireland, the national membership organisation for professional childminders. All participants were female, and the background survey showed that over 70% held the national standard qualification for centre-based ECEC practitioners, a 400-hour post-secondary certificate (See for more details). Over half of the participants had been working as childminders for less than six years, with five participants setting up in the previous two years; seven participants were childminders for nine years or more.

Table 1. Participant Profiles.

Findings: Real Life Learning

A key finding to emerge in the present study was a specific cultural model of pedagogy, named in participants’ own words as ‘Real Life Learning’. In holistic ratings, participants (n = 17) were rated Low-Medium on the School Readiness model (Tonyan Citation2015). However, the majority were rated High- Medium (n = 16) on the Real Life Learning model. (See .)

Table 2. Real Life Learning model: Holistic Ratings for Study Participants.

Findings described a Real Life Learning model whose primary goal is to explore learning opportunities presented by real life experiences as they arise, reminiscent of Hayes’ nurturing pedagogy (Hayes and Kernan Citation2008) and the flexible, child-led, emergent curriculum of Reggio Emilia (Freeman and Karlsson Citation2012). The childminder prioritises relationship-driven, child-led learning mediated through everyday experiences both in an enriched home environment and out in the community. The freedom of the low-stress home-from-home environment was emphasised, as were the value of the mixed age groups, with siblings kept together, and the flexibility and frequency of outings in the community, reminiscent of the approach in early years’ settings in Reggio Emilia (Rinaldi Citation2006).

Relationship-driven learning

One key feature of the Real Life Learning model identified how childminders focus on getting to know each child in their small group ‘inside out’, being child-centred, which then forms the basis of child-led activities, as the following illustrates:

So, it's lovely, I have a one-on-one with him … that's all led by him, you know what I mean? I don't sit down with a one-and-a-half-year-old and go, ‘Right now for the next hour, we'll be doing this … ’ I'd be on the floor playing dinkies, or at the bay, whatever he decides, you know? – Marianne.

Learning from everyday experiences

Childminders in the study placed considerable emphasis on the value of ordinary experiences for the children in their care, as their photographs (n ≤ 10 per participant) highlighted children preparing food, growing vegetables, climbing trees, helping with laundry, and on regular outings to local playgrounds, libraries, and schools. One photograph showed a three-year-old child chopping vegetables with a real knife for the evening meal, and the phrase ‘real life experience’ arose; to emphasise, the same participant showed a photograph of children playing on a tyre swing:

I just think children need to have real life experiences instead of something that's orchestrated, so that they can't climb, they can't experience what it's like to climb up a tyre and sit on the swing or up a tree, or up on climbing frames … –Nicky.

Mixed age learning

Another significant aspect of this Real Life Learning model is mixed age groups with a wide range of ages. Of 17 study participants, 13 worked with a mixed age group of children, varying from babies and toddlers to school-goers of 12–13 years of age, many of whom were also siblings. Drawing heavily on the theory of Vygotsky and the concept of scaffolding, Rogoff (Citation1990) describes guided participation in cultural activity, noting how such environments ‘provide many benefits, including the opportunity to practice teaching and nurturance with younger children and the opportunity to imitate and practice role relations with older children’ (Citation1990, 164).

The possibilities for mixed age groups facilitating bi-directional learning were emphasised in the study narratives. In particular, the development of empathy and a sense of responsibility towards younger children was identified, for example, in how older children took care of younger ones when out on a walk or in the playground. Younger children were represented as copying things that older children do and wanting nothing more than to be involved in their play. For example, in one home, two school age children were observed playing shop with two younger toddlers, where each was assigned the role of shop assistant or customer, with ‘goods’ exchanging hands and plenty of ‘money’ being counted; this role play gave the toddlers an opportunity to learn and practice new vocabulary, including numbers, and the skill of turn-taking.

According to Gray (Citation2011), bi-directional learning occurs most frequently when the difference in status between tutor and learner is not too great. Thus, when older children explain concepts, such as turn-taking, to younger ones in mixed age play, they must turn their previously implicit, unstated knowledge into words that younger children can understand (and question), so that both ‘tutor’ and ‘learner’ are helping each other to learn. Much of this practice is reminiscent of that in Reggio Emilia preschools, where small mixed-age groups are used, rather than homogenous groups, in order to harness these dynamics in the service of a child-led emergent curriculum (Katz Citation1998).

Enriched home learning environments (HLE)

In this study, the home learning environment (HLE) provided by the participating childminders was linked to both daily routine activities and the presence of enriching materials inside and outside the home, affording opportunities for educationally oriented activities. Prior research has established the relationship between the development of language, vocabulary, and early cognitive attainment and the HLE, conceptualised as the frequency of educationally oriented activities undertaken by parents with their young children within the home (Sammons et al. Citation2015).

Observations revealed enriched home learning environments, developed with the help of the Childminder Development Grant, a small capital grant (€1,000) designed to improve safety and quality, providing for the purchase of equipment, toys or minor adaptations (DCYA Citation2008). In each home, at least two rooms were used for childminding: a kitchen/ dining area, where children eat their meals and do crafts or homework, and either a playroom or a living room, usually well equipped with a rich variety of toys, books and craft supplies, with low-level shelving to give the children easy access to books and toys. In addition, participants used at least one bedroom where babies and toddlers could nap in their own cot, and the bathrooms were equipped with a nappy changing station, along with potties, toilet steps, and toddler toilet seats. Outside there was a variety of push–pull toys, scooters, swings and jungle gyms, as well as football nets, sand pits and paddling pools, along with a shed to store the equipment/toys and allow for rotation.

In this research, childminders highlighted the freedom the children have to play in the garden at any time, increasing opportunities for physically active play, which impacts on children’s motor skills and fitness (Fjørtoft Citation2001). Messy, unstructured outdoor play was presented as a healthy thing for children’s development. Children had easy access to run in and out to the garden often during the day, unrestricted by a schedule. Often the children kept wellingtons and outdoor play gear at the childminders to facilitate this:

If the weather is good, we're outside, we have the wellies and everything with them, they leave them here. So, we'd have the outside, we'd be down round looking at the leaves and the apple trees, and all the rest of them. -Cathy

This in the summer was veg(etables), and now it's the winter garden and in there are daffodils and winter pansies. And that'll be it then until we start off again in the springtime. –Áine

Out in the community

Another particular finding was the emphasis which participants placed on routine outings with the children in the local area. Almost all study childminders mentioned how they went out daily on routine drop offs and collections at schools and preschools, or simply out for a walk to a local playground, park or green, the shops or a library. Time outside and on outings was perceived as essential for the children’s physical and mental well-being, in line with the emphasis in Aistear and Síolta on environments which provide a range of developmentally appropriate, challenging, diverse, creative, and enriching experiences (NCCA Citation2015). The following excerpt is typical:

Every day I would try to get out, either for a walk or just to the garden … I have the double buggy so I can take them for walks if we’re not going away somewhere, then I take them for a walk, we go down to the shops or the play park … or we go out to the forest cos it’s only like five minutes down the road. –Shona.

The importance of outings for children was also linked to making connections beyond the home with the broader community. The daily routine of drop offs and pickups from local schools and preschools helped children feel secure and welcome in these settings when it was their turn to go to ‘big school’; they had already seen or met the teachers and some of the children too, facilitating their own transition to preschool or school (Ang, Brooker, and Stephen Citation2016). Many study participants used their photographs to tell the story of their difference from centre-based care emphasising this ordinary, routine contact in the community. The following description of a photograph taken during a school run illustrates this:

… it kind of symbolizes that the children really come with me for everything. You know, if I do shopping, they come along, for the school run they come along, if we have to go to the post office, they come along. So, they are comfortable in the environment really, because they are there every day so … –Rianne

Home-from-home

Childminders in this study were keen to emphasise the home-from-home environment, where children could relax, as opposed to more institutional, centre-based services: ‘Again this was, this was them, it just captures the freedom of how the kids feel at home. It's like a home-from-home environment’. [Sonia]. The environment, routines and people within a home provide rich opportunities for expanding and enhancing young children’s learning (Hayes, O’Toole, and Halpenny Citation2017).

In this context, the development of everyday, practical and useful skills was highlighted. Cooking and baking were favourite activities; some were baking scones or cookies regularly, others were helping make their dinner for the day, peeling and chopping carrots or other vegetables. Other household jobs included helping to pack the dishwasher or do grocery shopping at the local supermarket – all things they would do if they were at home with their own parents. In this way, the children were learning not only practical skills, but also how to share the burden of care and the mutually supportive roles in home life. For the children, further home-from-home routines included going to afterschool activities, such as swimming, football or dancing, as they would with their own parents, participating in the local community of children.

Another home-from-home practice involved supporting children to take responsibility, as part of a maturing process appropriate for children at a certain age. For example, the privilege of walking back to the childminder’s home from school with a buddy, without adult supervision, was seen as a mark of respect by the children, a coveted privilege and an acknowledgment of their increasing competence. Commenting on age-appropriate, unsupervised play on the local green with other children in the neighbourhood, one participant opined:

I think they (parents) just feel that they have this home-from-home environment, that if they were at home in their own house that they would do the same things, you know. And they need to have risky play and to climb a tree down there and, you know, not have an adult looking at them the whole time. – Mary

Discussion

The description of a cultural model of Real Life Learning is a significant finding in this research, as it provides ecocultural documentation of a distinctive pedagogy of childminding in Ireland, as summarised in . The primary goal is exploring the learning opportunities presented by real life experiences, mediated through child-led play and explorations in a relationship-driven home learning environment. This model was pointedly differentiated by certain participants from perceptions of school readiness often associated with centre-based preschool settings in Ireland (Ring et al. Citation2016). It also presents significant contrasts with the School Readiness model found among childminders in California (Tonyan Citation2017), even though many similarities were found with the Close Relationships model described in the US study (Tonyan Citation2017; O’Regan, Halpenny, and Hayes Citation2020).

It is important to understand the link between childminders’ pedagogy and the structural parameters of group size and adult–child ratio. In California, a small-scale family childcare licence allows for up to eight children, and large-scale licence allows up to 14 children with an assistant. Tonyan and Nuttall (Citation2014) explicitly link aspirations to open a centre among large-scale licence holders to bureaucratic models of preschool care (Bromer and Henly, Citation2004), such as the School Readiness model. These large-scale providers more closely resemble the Irish solo preschool provider, who offer a sessional service for up 11 children under the free preschool programme, sometimes in home-based environments (). However, the key structural difference in adult–child ratio and group size may help to explain how low the School Readiness model was rated among childminders: the sole High rating went to a rural childminder who provided the government funded free preschool programme as a sessional childminding service.

The Real Life Learning model seems to function optimally in the more intimate settings of childminders with smaller group size. By virtue of being more intimate, these settings allow for higher levels of adult attention and more frequent interaction with each child in a relational, nurturing pedagogy (Hayes and Kernan Citation2008). Smaller group size has been associated with higher process quality (Laevers et al. Citation2016); with smaller numbers, childminders can be more flexible with regards to routine, allowing the child’s needs and interests to be prioritised more easily in a child-led, emergent curriculum (Rinaldi Citation2006). Caring for small numbers of children also facilitates freedom for outings in the local area, giving children access to a wider variety of affordances in the local community.

Smaller numbers facilitate relationship-driven learning, which is central to the Real Life Learning model. The close, intimate relationship between the childminder and the child mediates bi-directional learning: in this context, seeing, knowing, and understanding each child holistically was a point of professional pride, as Tonyan (Citation2017) has also described. Intersubjectivity, most simply understood as the interchange of thoughts and feelings between two persons facilitated by empathy, is at the heart of this awareness of the child’s being, and forms the core of a child-led approach to learning. Trevarthen and Delafield-Butt speak of a ‘responsive pedagogy’ (Citation2017, 3) which respects the infant’s meaning making initiatives, where responding to the young child’s overtures can build shared narratives of meaning. Similarly, Hayes (Citation2007) proposes a nurturing pedagogy that focuses on shared, two-way, active engagement between child and adult in bi-directional interactions, with connotations of rich, nourishing warmth and care in the relationship.

In one of the few studies focussed on the pedagogy of childminding, Freeman (Citation2011) describes childminders’ approach in socio-cultural terms as ‘authentic pedagogy’ in a ‘warm, active environment of belonging’ (Citation2011, 228) with a focus on child-led play, referencing Reggio Emilia in describing childminders’ responsiveness and reflection. In the Real Life Learning model, these responsive interactions between child(ren) and childminder within the everyday routines of life create the socialisation of trust and form the pathways of child development (Weisner Citation2002, Citation2014). The unique nature of each individual childminding setting in the study reflected the complex interactions between the specific interests, abilities and characteristics of the minded children and the particular interests, knowledge and skills of the childminder in a process, which generates new knowledge and transforms the environment in bi-directional synergy according to the Bio-Ecological Model of Development (Hayes, O’Toole, and Halpenny Citation2017).

A noteworthy component of the Real Life Learning model identified in this study was children’s freedom to access environmental affordances, indoors and outdoors. This contrasts with Lynch’s (Citation2011) finding that access to the outdoors was lacking in typical Irish homes in her study of children’s home play environments. It also contrasts with Kernan and Devine’s (Citation2010) finding that the outdoors was increasingly marginalised in young children’s everyday experience in early childhood settings in Ireland. Implicit in rich learning environments is the provision of opportunities for children to engage in progressively more complex reciprocal interactions with the people, objects and symbols (Bronfenbrenner and Morris Citation2006). The meaning-making process between the child and the environment (Gibson Citation1977) is stimulated through affordances which children value, which invite exploration and imagination. This reinforces the importance of the environment in relation to the child’s agency in his/her unfolding development (Kernan Citation2015).

In an enriched home environment, some of the activities in the childminders’ daily routines echo those of the HLE Index developed in the Effective Provision of Preschool Education project (Melhuish et al. Citation2008). In terms of children’s outcomes, higher than average scores in verbal ability and emotional self- regulation have been found among three year olds with childminders in the Study of Early Education and Development (Melhuish et al., Citation2017; Otero and Melhuish, Citation2015) and also in the longitudinal Growing Up in Ireland study (McGinnity, Russell, and Murray Citation2015; Russell, Kenny, and McGinnity Citation2016).

Another significant feature of the Real Life Learning model is the mixed ages of children in these small groupings. In contrast to an increasingly age-stratified school environment, the childminding setting affords natural scaffolding, allowing for rich role-play and social learning (Gray Citation2011). The childminder actively supports the joint learning between younger and older children, as each develops new skills: increasing and honing vocabulary for the younger child, while growing empathy and responsibility in the older one.

A particularly striking feature of the Real Life Learning model is the daily outings and excursions, and regular contact with schools and community groups. Children’s contact with the community outside the childminding home in toddler groups and on school drop offs and collections provide opportunities for learning to live together with the local community (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Citation2006). In exploring children’s experiences in childminding settings in the USA and Sweden, Freeman and Karlsson (Citation2012) also note how childminders can form part of a local community network, mediating children’s relationships with the everyday world, building stable and substantive relational ties, with continuity between childminders, parents and neighbourhood schools. Routine collections from local schools and preschools have been found to give children opportunities to make connections with the broader community of children beyond the home, supporting their transitions into these settings (Ang, Brooker, and Stephen Citation2016). By participating in everyday activities in the local area with their childminder, children absorb enduring messages from people, the environment and the wider community helping to create a sense of place, identity and belonging, as encouraged by Irish national early years frameworks (NCCA Citation2015). This value for community connections, ‘learning to be together’ (OECD Citation2006) continues to typify Irish culture (Fitzpatrick Citation2019), and can be seen also in the ecocultural Real Life Learning model among childminders.

Freedom and flexibility are key values identified in this model: freedom for child-led, flexible interactions with the environment formed a significant element of childminders’ conceptualisation of their pedagogy. For example, the freedom for outings constituted a key component of childminding for study participants, echoing the Reggio Emilia approach, which gives children the freedom both to explore the hundred languages of childhood in play and to use these skills of everyday life (Edwards et al.,Citation1998). This freedom was evidenced by the relaxed informality of childminder praxis in the present study, where apart from the registered childminders, there were almost no written observations or other forms of documentation in evidence except for photos.

This relaxed approach is similar to childminding practice in France, where the main goal is ‘éveil’ (awakening), understood as accompanying the child’s unfolding development at all levels in the daily routine of everyday life, while enculturating the children in locally valued ideals, such as encouraging a large, expressive vocabulary and sitting at table for long meals (Observatoire National de la Petite Enfance,Citation2018). Such flexible, unstructured freedom to learn at the child’s own pace contrasts with the trend towards schoolification in early childhood learning in recent years (Ang, Citation2014), even as many early childhood educators contest this emphasis on school readiness, assessment, and the achievement of normative goals for very young children). In this context, the Real Life Learning model could be considered evidence of an older, more traditional approach, where care and nurture are prioritised in practice, and where learning to be, learning to learn, and learning to live together (OECD Citation2006) are deeply rooted values underpinning the daily routine of activities in childminding homes. In changing times, such continuity of values across generations (Gallagher and Fitzpatrick Citation2018) can contribute to a stable, substantial, relational foundation for young children’s lives.

Some policy implications

To engage childminders effectively, the proposed childminding regulations in Ireland must honour the unique features of childminding and support childminders to maximise the benefits of the Real Life Learning model, without imposing unnecessary demands such as formal observations and child assessments. The new regulations should respect the values of flexibility and freedom by supporting daily outings and spontaneous excursions, rather than restricting them with cumbersome health and safety assessments. In addition, childminder education must be developed to respectfully encourage and extend the cultural model of Real Life Learning, with accessible, blended and community-based learning for childminders who often work long hours in relative isolation. Ultimately, the new Irish childminding system of regulation, education and supports must be aligned with childminders’ pedagogy of Real Life Learning, if is to prove meaningful, congruent, and sustainable for childminders, families and children into the future.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ang, Lynn, Elizabeth Brooker, and Christine Stephen. 2016. “A Review of the Research on Childminding: Understanding Children’s Experiences in Home-Based Childcare Settings.” Early Childhood Education Journal 45 (2): 1–10. doi:10.1007/s10643-016-0773-2.

- Ang, Lynn. 2014. “Preschool or Prep School? Rethinking the Role of Early Years Education.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood 15 (2): 185–99. https://doi.org/10.2304/ciec.2014.15.2.185.

- Bauters, Valerie, and Michel Vandenbroeck. 2017. “Bauters & Vandenbroeck The Professionalisation of Family Day Care in Flanders France and Germany.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 25: 386–397. doi:10.1080/1350293X.2017.1308164.

- Bromer, Juliet, Lisa A. McCabe, and Toni Porter. 2013. “Special Section on Understanding and Improving Quality in Family Child Care: Introduction and Commentary.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 28 (4): 875–878. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2013.08.003.

- Bromer, Juliet, and Julia R. Henly. 2004. “Child Care as Family Support: Caregiving Practices across Child Care Providers.” Children and Youth Services Review 26 (10): 941–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2004.04.003

- Bronfenbrenner, U., and P. A. Morris. 2006. “The Bioecological Model of Human Development.” Handbook of Child Psychology 1: 793–828. doi:10.1002/9780470147658.chpsy0114.

- Brooker, Liz. 2016. “Childminders, Parents and Policy: Testing the Triangle of Care.” Journal of Early Childhood Research 14: 69–83. doi:10.1177/1476718X14548779.

- CCCRP. 2014. The Ecocultural Family Interview For Family Child Care Providers.

- CECDE. 2006. “Síolta. The National Quality Framework for Early Childhood Education,” no. April: 1–19.

- Child in Mind. 2017. “Child In Mind Evidence-Based Learning Outcomes for Informal Childminders.” http://www.childinmind-project.eu/assets/pdf/CiM_O1-A3_Evidence Based Learning Outcomes Report_2017-04-19.pdf.

- CSO. 2017. “CSO Quarterly National Household Survey Module on Childcare2017.”

- Daly, Mary. 2010. “An Evaluation of the Impact of the National Childminding Initiative on the Quality of Childminding in Waterford City and County.” Waterford City & County Childcare Committees, and Health Service Executive South.

- Davis, Elise, Ramona Freeman, Gillian Doherty, Malene Karlsson, Liz Everiss, Jane Couch, Lyn Foote, et al. 2012. “An International Perspective on Regulated Family Day Care Systems.” Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, no. December.

- DCEDIY. 2021. “National Action Plan for Childminding 2021-2028.”

- DCYA. 2008. National Guidelines for Childminders. http://www.dcya.gov.ie/viewdoc.asp?fn=/documents/Publications/National_Guidelines_for_Childminders_Revised_August_2008.pdf.

- DCYA. 2016. CHILD CARE ACT 1991 (EARLY YEARS SERVICES) REGULATIONS 2016. Department of Children and Youth Affairs. Vol. 1991.

- DCYA. 2018a. “Pathway to a Quality Support & Assurance System for Childminding: Summary Report of the Working Group on Reforms and Supports for the Childminding Sector.” https://assets.gov.ie/26359/04ec2e05e5284b849ae0894e65d4ce8f.pdf.

- DCYA. 2018b. Registration of School Age Services. http://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/2018/si/575/made/en/pdf.

- DCYA. 2019a. “Draft Childminding Action Plan August 2019.”

- DCYA. 2019b. “First Five Implementation Plan 2019-2021.” https://www.dcya.gov.ie/documents/earlyyears/20190522First5ImplementationPlan22May2019.pdf.

- Edwards, Carolyn P., Lella. Gandini, and George E. Forman. 1998. The Hundred Languages of Children: The Reggio Emilia Approach–Advanced Reflections. One Hundred Languages of Children. Ablex Pub. Corp.

- Fitzpatrick, Anne. 2019. “Towards a Pedagogy of Intergenerational Learning.” In Intergenerational Learning in Practice: Together Old and Young, edited by Margaret Kernan, and Giulia Cortellesi, 1st ed .1–20. London: Routledge.

- Fjørtoft, Ingunn. 2001. “The Natural Environment as a Playground for Children: The Impact of Outdoor Play Activities in Pre-Primary School Children.” Early Childhood Education Journal 29 (2): 111–117. doi:10.1023/A:1012576913074.

- Freeman, Ramona. 2011. “Reggio Emilia, Vygotsky, and Family Childcare: Four American Providers Describe Their Pedagogical Practice.” Child Care in Practice 17 (3): 227–246. doi:10.1080/13575279.2011.571236.

- Freeman, Ramona, and Fildr Malene Karlsson. 2012. “Strategies for Learning Experiences in Family Child Care: American and Swedish Perspectives.” Childhood Education 88 (2): 81–90. doi:10.1080/00094056.2012.662116.

- Gallagher, Carmel, and Anne Fitzpatrick. 2018. “‘It’s a Win-Win Situation’–Intergenerational Learning in Preschool and Elder Care Settings: An Irish Perspective: Practice.” Journal of Intergenerational Relationships 16 (1–2): 26–44. doi:10.1080/15350770.2018.1404403.

- Gallimore, Ronald, Claude N. Goldenberg, and Thomas S. Weisner. 1993. “The Social Construction and Subjective Reality of Activity Settings: Implications for Community Psychology.” American Journal of Community Psychology 21 (4): 537–560. doi:10.1007/BF00942159.

- Gibson, James J. 1977. “The Theory of Affordances.” In The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception edited by J.J. Gibson, 56–60. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. https://doi.org/10.2307/429816.

- Gray, Peter. 2011. “The Special Value of Children’s Age-Mixed Play.” American Journal of Play 3 (4): 500–522. https://www.psychologytoday.com/files/attachments/1195/ajp-age-mixing-published.pdf.

- Hayes, Nóirín. 2007. “Perspectives on the Relationship between Education and Care in Early Childhood: A Research Paper.” Aistear: The Early Childhood Curriculum Framework Background Papers.

- Hayes, N., and Margaret Kernan. 2008. Engaging Young Children: A Nurturing Pedagogy. Dublin: Gill & Macmillan Ltd.

- Hayes, Noirin, Leah O’Toole, and Ann Marie Halpenny. 2017. Introducing Bronfenbrenner: A Guide for Practitioners and Students in Early Years Education. Routledge: Taylor & Francis Group.

- Holland, Dorothy, and Naomi Quinn, eds. 1987. Cultural Models in Language and Thought. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1987.89.4.02a00810.

- Katz, Lilian G. 1998. “What Can We Learn from Reggio Emilia?” One Hundred Languages of Children: The Reggio Emilia Approach, 27–45. https://www.theartofed.com/content/uploads/2015/05/What-We-Can-Learn-From-Reggio.pdf.

- Kernan, Margaret. 2015. “Learning Environments That Work : Softening the Boundaries.” Early Educational Alignment: Reflecting on Context, Curriculum and Pedagogy, no. October: 1–20.

- Kernan, M., and D. Devine. 2010. “‘Being Confined within?’ Constructions of a ‘Good’ Childhood and Outdoor Play in Early Childhood Education and Care Settings in Ireland.” Children and Society 24 (5): 386–400. https://www.nber.org/papers/w15827.pdf.

- Laevers, Ferre, Evelien Buyse, Mieke Daems, and Bart Declercq. 2016. “Welbevinden En Betrokkenheid Als Toetsstenen Voor Kwaliteit in de Kinderopvang. Implicaties Voor Het Monitoren van Kwaliteit.” BKK. https://lirias.kuleuven.be/handle/123456789/572800.

- Letablier, Marie-Thérèse, and Jeanne Fagnani. 2009. “EUROPEAN ALLIANCE FOR FAMILIES European Expert Group on Demography Best Practice Meeting on Child Care by Child Minders in France Childminders in the French Childcare Policy.”

- Lynch, Helen. 2011. “Infant Places, Spaces and Objects: Exploring the Physical in Learning Environments for Infants Under Two.” Dublin Institute of Technology. https://doi.org/10.21427/D73W37

- McGinnity, Frances, Helen Russell, and Aisling Murray. 2015. “Growing Up in Ireland NON-PARENTAL CHILDCARE AND CHILD COGNITIVE OUTCOMES AT AGE 5: Results from the Growing Up in Ireland Infant Cohort.”

- Melhuish, Edward, Mia Phan, Kathy Sylva, Pam Sammons, Iram Siraj-Blatchford, and Brenda Taggart. 2008. “Effects of the Home Learning Environment and Preschool Center Experience upon Literacy and Numeracy Development in Early Primary School.” Journal of Social Issues 64 (1): 95–114. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.2008.00550.x.

- Melhuish, Edward, Julian Gardiner, and Stephen Morris. 2017. Study of Early Education and Development (SEED): Impact Study on Early Education Use and Child Outcomes up to Age Three.” Study of Early Education and Development (SEED)- Impact Study on Early Education Use and Child Outcomes up to Age Three Research report. https://e-space.mmu.ac.uk/618814/1/

- Mooney, Ann, and June Statham. 2003. “Family Day Care. International Perspectives on Policy, Practice and Quality.” In Family Day Care. International Perspectives on Policy, Practice and Quality, edited by Ann Mooney, and June Statham, 41–58. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- NCCA. 2009. Aistear: The Early Childhood Curriculum Framework. www.ncca.ie.

- NCCA. 2015. Aistear Síolta Practice Guide: Introduction. http://www.ncca.ie/en/Practice-Guide/About/Introduction/AistearSiolta-Practice-Guide-Introduction.pdf.

- Observatoire National de la Petite Enfance. 2018. “Résultats Du Rapport 2018 de l’Observatoire National de La Petite Enfance.” https://www.caf.fr/sites/default/files/cnaf/Documents/Dser/observatoire_petite_enfance/AJE_2018_bd.pdf

- OECD. 2006. Starting Strong II. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13398-014-0173-7.2.

- O’Regan, Miriam, Ann Marie Halpenny, and Nóirín Hayes. 2019. “Childminding in Ireland: Attitudes Towards Professionalisation.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, October, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2019.1678716.

- O’Regan, Miriam, Ann Marie Halpenny, and Nóirín Hayes. 2020. “Childminders’ Close Relationship Model of Praxis: An Ecocultural Study in Ireland.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 28 (5): 675–689. doi:10.1080/1350293X.2020.1817239.

- Otero, Maria Pia, and Edward Melhuish. 2015. “Study of Early Education and Development (SEED): Study of the Quality of Childminder Provision in England,” no. September: 1–62.

- Rinaldi, Carlina. 2006. Contesting Early Childhood: Listening, Researching and Learning. London and New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203317730

- Ring, E., M. Mhic Mhathúna, M. Moloney, N. Hayes, D. Breathnach, P. Stafford, D. Carswell, et al. 2016. “An Examination of Concepts of School Readiness Among Parents and Educators in Ireland Overview of Project,” 184. https://www.dcya.gov.ie/documents/earlyyears/20170118AnExaminationOfConceptsOfSchoolReadinessAmongParentsEducatorsIreland.PDF.

- Rogoff, B. 1990. Apprenticeship in Thinking: Cognitive Development in Social Context. New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.3946/kjme.2009.21.2.197.

- Rogoff, B., L. Moore, B. Najafi, A. Dexter, M. Correa-Chavez, and J. Solis. 2005. “Childrens Development of Cultural Repertoires through Participation in Everyday Routines and Practices.” In Handbook of Socialization, edited by J. Grusec and P. Hastings, 1–48. New York: Guilford Press.

- Russell, Helen, Oona Kenny, and Frances McGinnity. 2016. Childcare, Early Education and Socio-Emotional Outcomes At Age 5 Evidence From the Growing Up in Ireland Study.

- Salmona, M., E. Lieber, and D. Kaczynski. 2019. Qualitative and Mixed Methods Data Analysis Using Dedoose. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Sammons, Pam, Katalin Toth, Kathy Sylva, Edward Melhuish, Iram Siraj, and Brenda Taggart. 2015 “The Long-Term Role of the Home Learning Environment in Shaping Students’ Academic Attainment in Secondary School.” Journal of Children's Services 10 (3): 189–201. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCS-02-2015-0007.

- Savage, Susan, and Holli Tonyan. 2015. Quality Improvement Efforts in Family Child Care.” https://slideplayer.com/slide/10642105/.

- Tonyan, Holli A. 2015. “Everyday Routines: A Window into the Cultural Organization of Family Child Care.” Journal of Early Childhood Research 13 (3): 311–327. doi:10.1177/1476718X14523748.

- Tonyan, Holli A. 2017. “Opportunities to Practice What Is Locally Valued: An Ecocultural Perspective on Quality in Family Child Care.” Early Education and Development 28: 727–744. doi:10.1080/10409289.2017.1303304.

- Tonyan, Holli A, and Joce Nuttall. 2014. “Connecting Cultural Models of Home-Based Care and Childminders’ Career Paths: An Eco-Cultural Analysis.” International Journal of Early Years Education 22 (1): 117–138. doi:10.1080/09669760.2013.809654.

- Tonyan, Holli A., Diane Paulsell, and Eva Marie Shivers. 2017. “Understanding and Incorporating Home-Based Child Care Into Early Education and Development Systems.” Early Education and Development 28 (6): 633–639.

- Trevarthen, Colwyn, and Jonathan T. Delafield-Butt. 2017. “Intersubjectivity in the Imagination and Feelings of the Infant: Implications for Education in the Early Years.” In Under-Three Year Olds in Policy and Practice, edited by E. J. White, and C. Dalli. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-2275-3.

- Urban, Mathias, Michel Vandenbroek, Arianna Lazzari, Jan Peeters, and Katrien van Laere. 2011. “Competence Requirements in Early Childhood Education and Care (CoRe) Final Report.”

- Weisner, Thomas S. 2002. “Ecocultural Understanding of Children’s Developmental Pathways.” Human Development 45: 275–281.

- Weisner, T. S. 2014. “The Socialization of Trust.” In Different Faces of Attachment: Cultural Variations on a Universal Human Need, edited by Hiltrud Otto, and Heidi Keller. Cambridge University Press. http://www.tweisner.com/yahoo_site_admin/assets/docs/Weisner_T_2015_22The_Socialization_of_Trust22_In_Different_Faces_of_Attachment.192202452.pdf.

- Weisner, Thomas S. 2014. “Why Qualitative and Ethnographic Methods Are Essential for Understanding Family Life.” In Emerging Methods in Family Research, edited by S. M. McHale. Vol. 4. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-01562-0.

- Weisner, Thomas S., Lucinda P. Bernheimer, and Mary Martini. 2005. “Sustainablity of Daily Routines as a Family Outcome.” In Learning in Cultural Context: Family, Peers and School, edited by Ashley Maynard, and Mary Martini. New York: Kluwer/Plenum. https://doi.org/10.1007/0-387-27550-9.

- Weisner, Thomas S., and C. M. Hay. 2015. “Practice to Research: Integrating Evidence-Based Practices with Culture and Context.” Transcultural Psychiatry 52 (2): 222–243. doi:10.1177/1363461514557066.