ABSTRACT

The social restrictions during the covid-19 pandemic have challenged many aspects of preschool everyday life. Particularly vulnerable to these restrictions is the aspect of introducing new children to preschool, since preschool introduction constitutes a natural arena for establishment of preschool staff’s relationships with children and their parents. Based on analysis of open-ended survey data (N = 465), the present study explores how Swedish preschool staff has experienced and dealt with the pandemic restrictions during preschool introduction. Our qualitative analysis resulted in three categories and six subcategories, including results demonstrating that social distancing-restrictions accentuate the importance of engaging relationally with the families, while simultaneously constituting a disconcerting complication since the physical distance constrains the important relationship-building between staff and parents. Moreover, the children seem to interpret the parent-staff physical distance as relational distance, which negatively affects their emerging relationship to preschool staff. Our results also show that how parental participation is organised during preschool introduction may be of critical importance for staff-child relational establishment, providing insights for researchers and practitioners in the field valuable to consider also in a non-pandemic context.

Introduction

Attachment theory posits that early interactions with parents are fundamental for children’s socioemotional development (Bowlby [Citation1969] Citation1982, Citation1973), as common parental responses to children’s distress teach about what to expect from others in times of difficulty, and how to self-regulate one’s emotions (Groh et al. Citation2017; Psouni, DiFolco, and Zavattini Citation2015). Recent developments in the field suggest that not only relations with parents but also with other caregivers regularly interacting with children, such as preschool staff, contribute to this development (Lamb and Ahnert Citation2007). Furthermore, good-quality relationships between children and preschool staff characterise to a larger extent high-quality preschools (Vermeer et al. Citation2016). During the covid-19-pandemic, many infection control measures have constrained social contact and interactions. Simultaneously, preschool staff has had an important pedagogical task in supporting the children’s coping with the covid-19 social constraints (Heikkilä et al. Citation2020). It is therefore crucial to understand whether, and how, the pandemic-related social restrictions affect the prerequisites for facilitating good interactions between preschool staff, the children, and their parents. Because transition to preschool can be an emotionally stressful life event for children and their families (Lamb and Ahnert Citation2007), the introduction phase is of special concern. Studies have demonstrated heightened levels of the stress hormone cortisol in children during the introduction phase (Ahnert et al. Citation2004; Bernard et al. Citation2015), persisting for over five months after enrolment (Ahnert et al. Citation2004). From an attachment-theoretical perspective (Bowlby [Citation1969] Citation1982; Ainsworth et al. Citation1978), these empirical findings are expectable and meaningful, as transition to preschool entails daily separations that interrupt the important stability and emotional availability of the parent(s) in the early child–parent attachment interplay. Thus, organising the preschool introduction to enable constructive relationship-building between preschool staff and the families, is crucial.

The pandemic-related social restrictions have most likely demanded adjustments to introduction procedures, and the potential impact of these adjustments is still unknown. Given the crucial role that preschool staff have in this process, the present study investigated their descriptions of how covid-19-related restrictions were applied and dealt with in Swedish preschools, and their perceptions and reflections of how the restrictions have impacted the introduction of children to preschool.

Interactions at preschool during the covid-19-Pandemic

While the negative effects of lockdowns entailing school interruptions are documented in previous literature (de Walque Citation2011), little is known regarding the effect of covid-19-related restrictions on preschool everyday life. A notable exception is a Turkish study (Yıldırım Citation2021) based on qualitative interviews with parents and preschool staff, mainly focusing on pandemic effects of the shift to distance education on older preschool children’s academic development. In another study, a comparison of preschool staffs’ reactions and experiences in relation to the earliest covid-19-related changes in preschool everyday life in Sweden, Norway, and the USA (Pramling Samuelsson, Wagner, and Ødegaard Citation2020), pointed to some beneficial consequences of covid-19-related reorganisations. For instance, Norwegian preschools reported better prerequisites for interactions with the children because of more favourable child–adult ratios.

In contrast to most other countries, preschools in Sweden have remained open during the pandemic. Since childcare in Sweden is a right to all children from the age of one year, and publicly subsidised (The Swedish National Agency for Education Citation2021c), preschool is a natural part of most children’s everyday life. Thus, Sweden constitutes a unique context for studying effects of the covid-19-situation on preschool introduction. Despite a lack of specific guidelines concerning preschool introduction conduct (Daníelsdóttir and Ingudóttir Citation2020), a recent study points to two models: (a) over a period of 3–5 full days, with the parent as active participant in everyday activities and primary caregiver to the child, or (b) over a period of 2 weeks, with the parent adopting a more passive role in the background of everyday activities (Markström and Simonsson Citation2017). The first separation between parent(s) and child occurs after a period of familiarisation with the preschool environment, but detailed information of how this is organised in each model respectively, is lacking.

During the covid-19-pandemic, the Public Health Agency of Sweden (Citation2021) called for a balance between serving the needs of children and precautionary actions necessary to prevent contagion. Preschools were thus advised to not practice physical distance towards the children but to organise activities in smaller groups, arrange outdoor activities, and communicate digitally with parents (Public Health Agency of Sweden Citation2020). A recent report based on interviews with 20 preschool principals and staff (The Swedish National Agency for Education Citation2021b) suggests that these reorganisations affected the relational quality between preschool staff and parents, while staff reductions due to sick-leave because of covid-19-symptoms negatively influenced the work climate and curriculum. The brief mention of the introduction phase in this report concerns prolongations and disruptions due to illness, reduced numbers of children introduced simultaneously, and increased time spent outdoors.

Although the restrictions applied in Sweden are seemingly harmless compared to preschool lockdowns, several concerns have been expressed particularly in relation to the preschool introduction phase (Lundahl Citation2021; Ringdahl Citation2021; Torro and Lindgren Citation2020), regarding mainly whether it is possible to maintain focus on interactions with both child and parent(s) while conducting the introduction phase in accordance with covid-19 guidelines. This is especially important considering that many children born during the pandemic are less used to out-of-home social contacts (Ringdahl Citation2021).

The present study

Although the Swedish covid-19-related preschool restrictions reflect a governmental awareness of the needs of small children, empirical knowledge regarding the impacts of covid-19 on the introduction phase is sparse. From an attachment-theoretical perspective, this is a much-needed knowledge since the preschool introduction may be critical for how the essential child-preschool staff relationships are built. Investigating how the preschool staff experience and evaluate organisational adjustments of the introduction will likely enable empirically informed recommendations, both in a pandemic context and for future work with introduction to preschool.

Thus, the present study collected data from preschool staff with a twofold aim. First, we wanted to address the limited information on whether, and to what degree, the introduction procedures have been affected by the covid-19-situation. For this purpose, we asked preschool staff to estimate quantitatively the pandemic impact. Second, we explored the participants’ experiences and reflections in relation to this impact, through two open-ended questions. The data collection was carried out as part of a larger study concerning preschool introduction procedures, which combined an ecological (Bronfenbrenner Citation1979) and systems theoretical perspective (Minuchin Citation1985) within an attachment theoretical framework (Bowlby [Citation1969] Citation1982).

Materials and methods

Procedure

The study protocol was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority. Data was collected online between January-March 2021, using the data collection tool REDCAP (Research Electronic Data Capture; Harris et al. Citation2009). Four preschool staff participated in a pilot study to evaluate the survey’s relevance in relation to their professional experiences. To ensure nuanced feedback, we chose pilot participants of varying age and education. Their responses indicated high face validity of the survey, while their feedback guided small adjustments.

For recruitment, the survey was announced through relevant online fora gathering preschool staff at a national level. The risk of psychological discomfort from participation was judged as minimal. In line with rules of ethical research conduct, participants were informed in detail about the study, including that participation could be terminated at any point, and consent was compulsory. An ethical consideration of special concern regarded how to protect participant anonymity, to facilitate the sharing of experiences and thoughts without risk of consequences. Therefore, to eliminate the risk of indirect identification, we did not ask which specific preschool/community participants worked in. The survey took 10–15 min to complete.

To enable transparency about sample representativeness and a contextualisation of the participants’ quantitative ratings, background data about the preschool staff was collected (age, gender, years of working experience, educational level, and geographical location of preschool). For the representativity-description, this data was compared to characteristics of the Swedish preschool staff population.

Participants

Participant (N = 465; of which n = 382 also contributed to the open-ended questions, see ‘Questions Regarding Covid-19’) age ranged from 22 to 65 years (M = 45.3, SD = 10.2 years), a distribution comparable to that of the population of licensed preschool teachers (The Swedish National Agency for Education Citation2021a). Not all participants reported their gender. Of those who did, 99% were women, aligning well with the Swedish preschool teacher population (96% women). Years of work experience in preschool ranged from 1 to 45 years (M = 18.5, SD = 11.1). Among participants, 60.3% held a preschool teacher degree. This is an overrepresentation compared to the preschool staff population in Sweden, where only 40.4% are licensed preschool teachers (Ibid.). Geographical spread of preschools corresponded well to the spread of the Swedish population (Sweden Statistics Citation2018), with close to a third of the preschools situated in urban, large cities (37.4%) and the rest in medium-large (32.1%) or in rural areas (30.5%).

Measures

Questions regarding Covid-19

Two quantitative questions regarding (a) covid-19-related influences on introduction and (b) respective influences of one’s thinking about the introduction (see ) were answered using a Likert-scale (1:‘Not at all’ to 5:‘To a high degree’), including a neutral alternative and a ‘Don’t know’ alternative, (following survey construction recommendations by Saris and Gallhofer Citation2007). Two open-ended questions invited participants to reflect freely on how introduction procedures have been impacted by the covid-19-situation: ‘Please describe how you experience that the introduction has been affected.’ and ‘Please describe how you experience that your way of thinking about the introduction has been affected.’

Table 1. Summary of quantitative ratings of covid-19 impact (N = 465).

Analysis of data

First, to offer a general idea of to what degree the covid-19-situation affected the preschool introduction organisation, we calculated descriptive statistics of the participants’ ratings of the covid-19-impact on introduction procedures and their own thinking about the introduction. Moreover, to facilitate a contextualisation of our results, we performed multivariate analysis of variance to examine whether participants’ background characteristics impacted their quantitative ratings.

Responses to the open-ended questions were in the form of free text, in total comprising 52 pages of transcripts. This material was analysed using a content-analytical approach. This method is appropriate when treating qualitative survey data derived from an otherwise quantitatively structured survey context as it can allow for a descriptive quantification of relevant categories (Vaismoradi, Turunen, and Bondas Citation2013), while simultaneously enabling an interpretation of how these categories are contextualised by the thoughts and experiences of the respondents (Graneheim, Lindgren, and Lundman Citation2017). Moreover, we used the study’s attachment-theoretical framework and empirical knowledge about preschool introduction procedures as a deductively inspired guide to the analytical process. However, due to the novelty of the study’s topic, we simultaneously chose to treat utterances that did not have immediate theoretical relevance, ‘left-over data’ (Graneheim, Lindgren, and Lundman Citation2017), as valuable information to refine and nuance the process of categorisation, enabling an expansion from the current theoretical and empirical knowledge of preschool introduction.

Adopting a critical-realistic stance (see for instance Sims-Schouten, Riley, and Willig Citation2007), we treated respondents’ answers as actual expressions of their thoughts and experiences, while simultaneously acknowledging them as being contextually produced by their sociodemographic characteristics and professional role. Our initial, statistical assessment of whether participant background characteristics affect their quantitative ratings were consulted to this end.

In the first stage of the qualitative analysis, we identified and quantified frequently occurring words and concepts to illustrate the extent of different themes in the data. Phrases such as ‘outside/outdoors’, ‘inside/indoors’, ‘time’, ‘peer group/group size’, ‘hours per day’, ‘length of introduction’ were used as key concepts to map the procedures of preschool introduction during the pandemic. For instance, words connoting ‘outside’, stated in relation to relocation of the introduction procedure from indoors to outdoors, were mentioned 319 times across the 382 responses. Next, an attachment-theoretical reading of the data revealed that words such as ‘attachment’, ‘bonding’, ‘emotional safety’, ‘relationship’, and ‘closeness’, were mentioned 214 times across responses.

As a second step of the analysis, to enable a refined categorisation of how the quantified concepts were described and thought of by the participants, the concepts were analysed in the context of (1) surrounding words and sentences and (2) central agents (children, parents, preschool staff) mentioned in relation to them. Approximately 58 expressions connoted positive experiences in relation to the impact of the covid-19-situation, in contrast to around 129 descriptions of negative experiences. Moreover, when analysing words surrounding preschool staff, expressions connoting covid-19-related consequences for the staff team (such as ‘anxiety of getting infected’; ‘cooperation’ and ‘consensus’ about introduction organisation and procedures) were mentioned 47 times. Although not directly connected to the theoretical framework of the study, this left-over data was still considered to constitute a coherent theme. Thus, it was deemed relevant to also include in the process of categorisation.

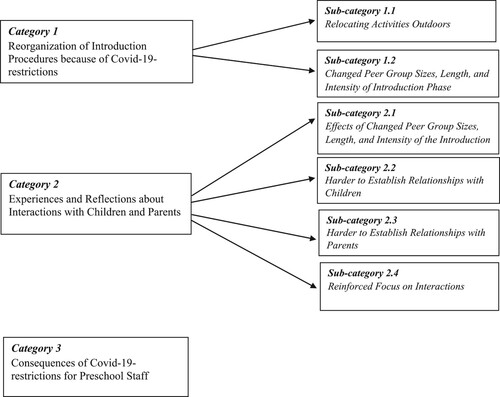

The final categorisation resulted in three categories and six sub-categories (). The words ‘few’ and ‘some’ refer to frequencies of less than 20%, ‘about half’ connotes around 50%, and ‘many’ describes a prevalence above 80%.

Results

Quantitative description of covid-19-related effects on introduction procedures

Most participants reported that introduction procedures were to some extent affected by the covid-19-situation (M = 3.79, SD = 1.23). About 60% rated the impact of the pandemic situation as substantial, while 32% reported it to be either modest or low. Furthermore, about 75% of participants reported that their way of thinking about the introduction procedures to some extent had been affected by the covid-19-situation (M = 2.91, SD = 1.32). A fifth reported no influence on their thinking about the introduction phase ().

Multivariate analysis of variance of responses concerning the degree to which covid-19 has impacted praxis and thinking revealed a significant effect of years of working experience (as continuous variable), geographical location of preschool, and whether participants held a preschool teacher degree or not (Wilks λ = 0.981; p = 0.027). Inspection of the univariate effects demonstrated that only the impact of years of experience was significant (F = 3.638; p = 0.027), with a positive correlation (r = .12; p < .01) with degree to which covid-19-situation has caused new thinking.

Thematic categories in preschool staff’s accounts

Category 1: Reorganisation of the Introduction Procedures Because of Covid-19-restrictions. Two sub-categories were found when coding the data material describing how the covid-19-adjustments have been carried out, mainly based on frequency of occurrence.

Sub-category 1.1: Relocating Activities Outdoors. Under usual circumstances, most activity during the introduction phase occurred inside the preschool buildings, with parent(s) and child familiarising themselves with the indoors preschool environment together before initiating the first separation from parent(s). However, the most common covid-19-related adjustment was to reorganise the introduction procedure to being mainly located at the preschool yard. About one third of responses described procedures allowing one parent to follow inside the preschool.

Subcategory 1.2: Changed Peer Group Sizes, Length, and Intensity of the Introduction Phase. A second frequently occurring reorganisation concerned quantitative characteristics of the introduction procedures. Many described reorganisations regarding length and intensity of the introduction phase. About half reported lengthened introduction phases in terms of days, and/or shortened amount of hours/day spent by the family at the preschool during the introduction. Some also mentioned a reduction of group sizes and fewer children being introduced simultaneously. A common reason for prolonging the introduction phase was the zero-tolerance policy concerning symptoms of infection:

Many introductions are prolonged or time-adjusted since children often exhibit symptoms of cold when enrolling in preschool.

Less time inside, parents participating fewer hours to avoid crowdedness, fewer children introduced simultaneously.

Subcategory 2.1: Effects of Changed Peer Group Sizes, Length, and Intensity of the Introduction. Shortening the introduction phase was mostly experienced negatively, as was lengthening the introduction phase due to the zero-tolerance for symptoms of infections:

Since parents cannot participate inside, the children need to be separated from their attachment figure earlier, which may not be good for them.

Stressed parents that react negatively when their child gets sick – they get worried that the introduction will take longer time.

Shorter days has resulted in more tranquility for the whole peer group during the introduction of new children.

It has been good having parents spending more days, but shorter amount of time, at the preschool, and solely outside. It has become calmer for the newly introduced children and the rest of the peer group.

The importance of being able to be inside, in calm, small groups during most of the [introduction] phase appears now essential to me.

I feel that it takes longer time to succeed in creating an attachment [to the child] since we spend much time outside.

We were advised to do the introductions outside this fall, and it does not at all give the same prerequisites for establishing close contact, and it makes attachment [to child] more difficult.

The children who are introduced are 1 years old and have difficulties moving around with thick winter clothes.

It can be more difficult to get good contact to the smallest children at the yard [outside] with many other children present.

The children are experienced as being affected by the [restrictions] concerning social distancing and have not always met many outside the family. Many small children have never been cared for outside the home before being enrolled in preschool.

We have to keep more distance; you are not as close to each other as before. The children might perceive this as an expression of us, preschool staff and parent, not trusting each other.

The most important impact, in my opinion, is the reduced physical contact between us adults. I’m afraid that it might affect the children when we [preschool staff and parents] ‘don’t want to’ get close to each other (…).

[It is] more difficult to have a parent-active participation since we are supposed to be outside and keep our distance (…).

We have been forced to re-do the whole introduction phase from having the parents participating during 3 whole days to [an introduction procedure located] before noon during 2 whole weeks.

How should we organize it [the parent-active introduction model] in the future? Do we have to hurry to have the children enrolled into the preschool on full-time so quickly? And do the parents have to be so active?

We have developed a new introduction procedure, questioning the concept of ‘parent-active’. Us preschool staff have instead taken a more active role during the introduction (…) The parents are [advised to] have a more observing role (…).

It [the introduction] has become calmer. (…) Parents are not active but are supposed to sit down a certain place at the preschool. We [preschool staff] can approach the child faster. The other children in the peer group are calm, hence, the rest of the preschool’s activities are less affected.

I now think more than ever on the importance of building relations/attachment to the child/family. How do you most optimally do this outdoors? What methods and procedures are necessary? And how can we, based on current prerequisites [the covid-19-situation] give the new children a sense of emotional safety at our preschool?

The experience of [introductions] has been good because we have communicated more clearly to the parents about why we do what we do.

Reflections also captured consequences of the covid-19-situation for the staff team. Some participants reported worries of getting infected by the coronavirus while being at work:

I think more about the risks of getting infected now.

The introduction itself has not been significantly affected since there is a clear agenda for how to organise it.

It has become messier. Some departments of the preschool only introduce children outdoors while others keep doing it indoors with social distancing and without shaking hands with parents. There are no clear guidelines to the preschool as a whole.

We need to constantly rethink and replan our procedures in relation to the introduction since it is now longer than usually. It has had us reflecting upon whether it might be a good idea to prolong the introduction phase in total, to promote a higher sense of emotional safety of the children at their first separation [from parent].

We have a clearer plan now than we used to. Before, it was like, let’s start out like this and see what happens, but now we have a clear time plan from the beginning (…).

There are some positive sides since we ‘are forced’ to cooperate more across the different departments of the preschool and help each other out.

Some pedagogues think that corona must be prioritized above all planning. This has led to new discussions which has complicated our work.

Discussion

The present study is, to our knowledge, the first to describe the experiences of preschool staff regarding the impact of covid-19-related restrictions on the introductory phase to preschool. Our qualitative analysis reveals difficulties with establishing contact with families during the pandemic, negatively affecting both parents and children. In addition, preschool staff demonstrated a tendency to reevaluate the way parental participation is organised during the preschool introduction. Seen together, our results indicate a renewed awareness of the importance of reflexively defined procedures for preschool introduction.

Role division as a key factor during Introduction

Our analysis revealed a change in the extent and nature, and a revaluation, of the role of parent-participation in the child’s introduction to preschool. This revaluation was primarily contributed by preschool staff working with a ‘parent-active’ introduction (Markström and Simonsson Citation2017). In the present study, preschools practicing a parent-active introduction before covid-19, perceiving it as positive, report having changed the role of the parent back to observing, and describe this as beneficial. While the active parental role may be theoretically meaningful, as it can create a synergetic effect on the child adjustment to preschool (Bronfenbrenner Citation1979), in the present study, a more passive role is reported to facilitate the child-staff relation-building. Indeed, a somewhat more passive parent in the background allows the child to use the parent as safe haven if distressed (Bowlby [Citation1969] Citation1982), while successively familiarising themselves with the staff and the preschool environment (Broberg, Hagström, and Broberg Citation2012) during exploration.

Thus, while preschool staff in a pre-covid-19 interview-study (Markström and Simonsson Citation2017) reported a high level of satisfaction with the parent-active procedure, our results suggest that preschool staff reassess the parental role, as they notice its impact on their own interactions with the children. This highlights the complex ways in which role division between preschool staff and parents influences the introduction phase. Moreover, it has repeatedly been shown that how preschool quality is affected by common preschool-structural factors, such as peer group size and adult–child ratios, depends on the co-existence with other important factors (Pramling Samuelsson, Williams, and Sheridan Citation2015; Lamb and Ahnert Citation2007), specific to the process they are meant to facilitate (Persson Citation2015b). Since our results suggest that the role division between parents and preschool staff may be of key importance to the introduction phase, future research ought to treat this as an important co-working factor with other, structural factors during the introduction.

Distance to parents; distance to children

Participants report that they often had to carry out many of the introduction activities outdoors. Consequently, introduction to the pedagogical milieu indoors was hampered. As previous studies have suggested, aspects of the pedagogical indoors environment, such as toys and size of playroom, can be central for building relationships (Vermeer et al. Citation2016; Simonsson Citation2015). Given the well-established connection between child-preschool staff relational quality and the child’s socio-emotional development (for overviews, see Ahnert, Pinquart, and Lamb Citation2006; Beckh and Becker-Stoll Citation2016) and preschool quality (Vermeer et al. Citation2016; Lamb and Ahnert Citation2007; Persson Citation2015a), it is worrying that the present participants report the outdoors activities to be especially problematic when it comes to relational establishment with the youngest children. Moreover, our results show that social distancing-restrictions and worries of getting infected resulted in difficulties establishing relationships also with parents, aligning with results found in a recent Swedish report (The Swedish National Agency for Education Citation2021b). This is disconcerting since, as has been recently shown, the quality of the relationship between parents and preschool staff, ‘the cocaring relationship’, also influence child adjustment (Lang et al. Citation2020). The difficulties interacting with parents in the traditional way during the introduction phase are especially troublesome since the introduction phase normally constitutes a significant possibility for staff to initiate the parent-staff relationship.

Our results indicate that the preschool staff experienced the covid-19-related restrictions interfering with relationship-building at preschool as particularly disturbing for the introduction process. Thus, the covid-19-situation seems to have resulted in increased awareness of the critical role of interactions with families during the preschool introduction. Indeed, our quantitative ratings demonstrate that about 75% of the respondents changed their way of thinking about the introduction phase. This heightened awareness can be viewed as a fortunate consequence of the experienced restrictions, especially in light of current trends of ‘schoolarization’ of the preschool curriculum (Ackesjö and Persson Citation2019), a movement which might deemphasize the importance of child-staff relationships in preschool everyday life.

Finally, the participants in our study express that social distancing between staff and parents also results in distance from the children. Perhaps even more problematic, children are described to perceive the distance between parents and staff as a sign of distrust. Consequently, not only has the social distancing complicated the cocaring relationships, but it might also have negatively impacted the child-staff relationship, as the child interprets the distancing as relational distance and lack of trust.

The importance of a well-defined Introduction phase

Our results suggest that preschools with already well-established and defined procedures for their introduction activities experienced the reorganisations of the introduction phase as less challenging. On the other hand, our results indicate that preschools with a lower grade of organisational structure around the introduction phase have been given an unexpected opportunity to discuss and reflect upon organisational procedures, forcing staff to cooperate to find new ways of working. For some, this intensified need of reflecting upon the procedures led to an increased awareness of the importance of a well-defined introduction phase. The role of a well-structured introduction phase, based on this kind of conscious reflexivity amongst the staff regarding the choice of introductory methods, has indeed been suggested to have beneficial effects on the feeling of engagement of preschool staff (The Danish Evaluation Institute Citation2021). Conscious reflexivity, or reflective awareness, amongst teachers around their pedagogical practice is, moreover, associated with enhanced professional development (McArdle and Coutts Citation2010). Interestingly, our quantitative analysis shows that working experience was significantly linked to more reflection around the covid-19-situation. Perhaps the ability to reflect upon one’s professional role develops with longevity in the pedagogical profession, as a mechanism to maintain occupational engagement and development. Simultaneously, our results suggest that the increased need of reflecting on the organisation of the introduction procedures for some preschools seemed to complicate their introductory work. Thus, constructively reflecting together as a team might be critical if staff are to benefit even from well-defined introduction procedures. This is noteworthy, not least from the perspective of staff wellbeing, since quick reorganisations of job assignments during the pandemic has led to increased levels of stress (The Swedish National Agency for Education Citation2021b).

Methodological considerations and limitations

The large number of participants and feedback from several respondents suggest a high face validity of the study, and trustworthiness in individual participant responses. However, although it is unlikely that a person outside the preschool occupation would have the motivation to participate, we cannot, due to the anonymity requirement, guarantee that the respondents were indeed preschool staff. Moreover, self-selection bias cannot be ruled out, constituting perhaps a backside of having ‘hit a nerve of interest’ in the target group. Furthermore, although the sample representativeness was satisfactory, a higher proportion among respondents held a preschool teacher degree, compared to the national population. It should be noted, however, that no significant association was found between having a preschool teacher degree and how covid-19-related effects were rated. Still, generalizability in the area of preschool research is difficult due to different cultural understandings and conditions for childcare (Lamb and Ahnert Citation2007), and Sweden constitutes a unique research context both regarding preschool as institution and regarding the covid-19-situation, posing limitations to generalisation.

The theoretical framework of our qualitative analysis secures its relevance in relation to established knowledge in the field. At the same time, treating leftover data as important contributions, has hopefully reduced the risk of excluding important themes outside the framework. Moreover, our critical-realistic stance allowed a consideration whether our data was influenced by the sociodemographic context of the sample (Sims-Schouten, Riley, and Willig Citation2007). To achieve this, we integrated results from the quantitative analysis of participant background information in the discussion. This analysis cannot, however, rule out the risk of the data being influenced by covid-19-related discourses rather than the participants ‘pure’ experiences. By using written responses instead of face-to-face interviews, possible interactional discursive effects that would otherwise have been present (Barbour Citation2007) has, however, been avoided. Finally, although systematically conducted, the analysis was still the result of us researchers as subjects, contextualised in and of our field of practice. Aware of this limitation, we prioritised a transparent description of the methodological process, and discussed extensively the procedure of, and disagreements during, coding and categorisation (Henwood and Pidgeon Citation1992).

Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to explore preschool introduction procedures in the unique context of a global pandemic. The results might be useful regarding adjustments of pandemic-related restrictions, such as the use of social distancing, should this be of continuing relevance. Social distancing appears to hamper the establishment of staff-parent relationships, while children seem to interpret the staff-parent physical distance as relational distance, which might affect their ability to develop trust in the staff, a significant prerequisite for the important child-preschool staff relational quality.

Furthermore, the question of role division between parents and staff during the introduction phase has emerged as an important factor to consider when organising the introductory activities, also in a non-pandemic context. From an attachment-theoretical perspective, the parent’s role in the introduction should be restricted to functioning as a safe haven to the child, to allow space for the child to build relationships to preschool staff. Particularly staff working with the parent-active introduction model offered several reflections with respect to this. Thus, the need for an empirically based evaluation of parent-participation and its effects on the outcome of introduction to preschool becomes clear.

Moreover, our results underscore the importance of having reflexively defined methods when introducing children to preschool, to promote engagement of preschool staff. Whether it is significant also for the relational establishment between preschool staff, the children, and the parents to have defined procedures during the introduction ought to be empirically evaluated in future research.

Finally, there are no guidelines for how to introduce children to preschool, neither in Sweden and other Nordic countries (Daníelsdóttir and Ingudóttir Citation2020) nor, to our knowledge, elsewhere. More importantly, empirical knowledge about the effect of different introduction procedures on the child, parents, and preschool staff is very limited. Thus, due to this lack of evidence, it is difficult to predict how proposed adjustments, for instance like the ones related to the pandemic, are likely to affect children during the sensitive transition of the preschool introduction. It is therefore advisable for future research to focus on the strengths and weaknesses of different procedures of introducing children to preschool for different children in different families.

Acknowledgements

Conceptualisation, MAS, EP; methodology, MAS, EC, EP; formal analysis, MAS, EC, EP; investigation, MAS; writing – original draft preparation, MAS, EC, EP; writing – review and editing, MAS, EC, EP; supervision, EC, EP; project administration, EP; funding acquisition, EP. All authors have approved the final manuscript. Note. MAS: Martina Andersson Søe, ES:Elinor Schad, EP: Elia Psouni.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ackesjö, Helena, and Sven Persson. 2019. “The Schoolarization of the Preschool Class – Policy Discourses and Educational Restructuring in Sweden.” Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy 5 (2): 127–136. doi:10.1080/20020317.2019.1642082.

- Ahnert, Lieselotte, Megan R. Gunnar, Michael E. Lamb, and Martina Barthel. 2004. “Transition to Child Care: Associations With Infant-Mother Attachment, Infant Negative Emotion, and Cortisol Elevations.” Child Development 75 (3): 639–650. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00698.x.

- Ahnert, Lieselotte, Martin Pinquart, and Michael E. Lamb. 2006. “Security of Children's Relationships With Nonparental Care Providers: A Meta-Analysis.” Child Development 77 (3): 664–679. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00896.x.

- Ainsworth, Mary, D. Salter, Mary C Blehar, Everett Waters, and Sally Wall. 1978. Patterns of Attachment: A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation. Oxford: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Barbour, Rosaline. 2007. Doing Focus Groups. London: Sage Publications.

- Beckh, Kathrin, and Fabienne Becker-Stoll. 2016. “Formations of Attachment Relationships Towards Teachers Lead to Conclusions for Public Child Care.” International Journal of Developmental Science 10 (3-4): 99–106. doi:10.3233/DEV-16197.

- Bernard, Kristin, Elizabeth Peloso, Jean-Philippe Laurenceau, Zhiyong Zhang, and Mary Dozier. 2015. “Examining Change in Cortisol Patterns During the 10-week Transition to a New Child-Care Setting.” Child Development 86 (2): 456–471. doi:10.1111/cdev.12304.

- Bowlby, John. (1969) 1982. Attachment and Loss: Vol. 1. New York: Basic Books.

- Bowlby, John. 1973. Attachment and loss. Vol. 2. Basic Books.

- Broberg, Malin, Birthe Hagström, and Anders Broberg. 2012. Anknytning i förskolan. Vikten av trygghet för lek och lärande. Stockholm: Natur and Kultur.

- Bronfenbrenner, Urie. 1979. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Daníelsdóttir, Sigrún, and Jenný Ingudóttir. 2020. The First 1000 Days in the Nordic Countries: A Situation Analysis. Copenhagen: Nordic Counsil of Ministers.

- The Danish Evaluation Institute. 2021. Børns start i vuggestue og dagpleje. Praksisser, erfaringer og oplevelser blandt dagtilbud og forældre. Copenhagen.

- de Walque, Damien. 2011. “Conflicts, Epidemics, and Orphanhood: The Impact of Extreme Events on the Health and Educational Achievements of Children.” In No Small Matter: The Impact of Poverty, Shocks, and Human Capital Investments in Early Childhood Development, edited by H. Alderman, 85–113. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Graneheim, Ulla H., Britt-Marie Lindgren, and Berit Lundman. 2017. “Methodological Challenges in Qualitative Content Analysis: A Discussion Paper.” Nurse Education Today 56: 29–34. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2017.06.002.

- Groh, Ashley M., R. M. Pasco Fearon, Marinus H. van IJzendoorn, Marian J. Bakermans-Kranenburg, and Glenn I. Roisman. 2017. “Attachment in the Early Life Course: Meta-Analytic Evidence for Its Role in Socioemotional Development.” Child Development Perspectives 11 (1): 70–76. doi:10.1111/cdep.12213.

- Harris, A. Paul, Robert Taylor, Robert Thielke, Jonathon Payne, Nathaniel Gonzalez, and G. Jose Conde. 2009. “Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap)—A Metadata-Driven Methodology and Workflow Process for Providing Translational Research Informatics Support.” Journal of Biomedical Informatics 42 (2): 377–381.

- Heikkilä, Mia, Ann-Christin Furu, Anette Hellmann, Anne Lillkvist, and Anna Rantala. 2020. “Barns deltagande i förskole- och daghemskontext under inledningen av coronavirusets utbrott i Finland och Sverige.” BARN - Forskning om Barn og Barndom i Norden 38: 13–28. doi:10.5324/barn.v38i2.3703.

- Henwood, Karen L., and Nick F. Pidgeon. 1992. “Qualitative Research and Psychological Theorizing.” British Journal of Psychology 83 (1): 97–111. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8295.1992.tb02426.x.

- Lamb, Michael E, and Lieselotte Ahnert. 2007. “Nonparental Child Care: Context, Concepts, Correlates, and Consequences.” In Handbook of Child Psychology: Child Psychology in Practice, edited by K. A. Renninger, I. E. Sigel, W. Damon, and R. M. Lerner, 950–1016. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

- Lang, Sarah, Lieny Jeon, Sarah Schoppe-Sullivan, and Michael Wells. 2020. “Associations Between Parent–Teacher Cocaring Relationships, Parent–Child Relationships, and Young Children’s Social Emotional Development.” Child & Youth Care Forum 49. doi:10.1007/s10566-020-09545-6.

- Lundahl, Matilda. 2021. “Inskolning blir ute-skolning.” Pedagog Malmö, 2021-02-18.

- Markström, Ann Marie, and Maria Simonsson. 2017. “Introduction to Preschool: Strategies for Managing the Gap Between Home and Preschool.” Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy 3 (2): 179–188. doi:10.1080/20020317.2017.1337464.

- McArdle, Karen, and Norman Coutts. 2010. “Taking Teachers’ Continuous Professional Development (CPD) Beyond Reflection: Adding Shared Sense-Making and Collaborative Engagement for Professional Renewal.” Studies in Continuing Education 32 (3): 201–215. doi:10.1080/0158037X.2010.517994.

- Minuchin, Patricia. 1985. “Families and Individual Development: Provocations from the Field of Family Therapy.” Child Development 56 (2): 289–302. doi:10.2307/1129720.

- Persson, Sven. 2015a. En likvärdig förskola för alla barn - innebörder och indikatorer. Stockholm: Swedish Research Council (Vetenskapsrådet).

- Persson, Sven. 2015b. “Pedagogiska relationer i förskolan.” Vetenskapsrådets rapport: Förskola tidig intervention 119–143.

- Pramling Samuelsson, Ingrid, Judith T. Wagner, and Elin Eriksen Ødegaard. 2020. “The Coronavirus Pandemic and Lessons Learned in Preschools in Norway, Sweden and the United States: OMEP Policy Forum.” International Journal of Early Childhood 52 (2): 129–144. doi:10.1007/s13158-020-00267-3.

- Pramling Samuelsson, Ingrid, Pia Williams, and Sonja Sheridan. 2015. “Stora barngrupper I förskolan relaterat till läroplanens intentioner.” Tidskrift for nordisk barnehageforskning 9 (7): 1–14.

- Psouni, Elia, Simona Di Folco, and Giulio Cesare Zavattini. 2015. “Scripted Secure Base Knowledge and its Relation to Perceived Social Acceptance and Competence in Early Middle Childhood.” Scandinavian Journal of Psychology 56 (3): 341–348. doi:10.1111/sjop.12208.

- Public Health Agency of Sweden. 2020. Förskolan är viktig under pandemin. Public Health Agency of Sweden (Folkhälsomyndigheten).

- Public Health Agency of Sweden. 2021. Förskolor. Public Health Agency of Sweden (Folkhälsomyndigheten).

- Ringdahl, Lotta. 2021. “Hur skolar man in ett barn som knappt varit utanför hemmet? .” Förskolan, 2021-02-19.

- Saris, Willem E., and Irmtraud N. Gallhofer. 2007. Design, Evaluation and Analysis of Questionnaires for Survey Research. New York: Wiley.

- Simonsson, Maria. 2015. “The Role of Artifacts During Transition into the Peer Group: 1- to 3-year-old Children's Persepective on Transition Between the Home and the Preschool in Sweden.” International Journal of Transitions in Childhood 8: 14–24.

- Sims-Schouten, Wendy, Sarah Riley, and Carla Willig. 2007. “Critical Realism in Discourse Analysis: A Presentation of a Systematic Method of Analysis Using Women's Talk of Motherhood, Childcare and Female Employment as an Example.” Theory & Psychology 17: 101–124. doi:10.1177/0959354307073153.

- Sweden Statistics. 2018. Tätorter 2018: Arealer och befolkning.: Sweden Statistics (Statistiska centralbyrån).

- The Swedish National Agency for Education. 2021a. Barn och personal i förskola 2020. The Swedish National Agency for Education (Skolverket).

- The Swedish National Agency for Education. 2021b. Covid-19-pandemins påverkan på skolväsendet. Delredovisning 3 – Tema förskolan. The Swedish National Agency for Education (Skolverket).

- The Swedish National Agency for Education. 2021c. Rätt till förskola. The Swedish National Agency for Education (Skolverket).

- Torro, Tuula, and Camilla Lindgren. 2020. “Introduktion av nya barn i coronatider.” Förskoleforum, 2020-08-03.

- Vaismoradi, Mojtaba, Hannele Turunen, and Terese Bondas. 2013. “Content Analysis and Thematic Analysis: Implications for Conducting a Qualitative Descriptive Study.” Nursing & Health Sciences 15 (3): 398–405.

- Vermeer, Harriet J., Marinus H. van Ijzendoorn, Rodrigo A. Cárcamo, and Linda J. Harrison. 2016. “Quality of Child Care Using the Environment Rating Scales: A Meta-Analysis of International Studies.” International Journal of Early Childhood 48 (1): 33–60. doi:10.1007/s13158-015-0154-9.

- Yıldırım, Bekir. 2021. “Preschool Education in Turkey During the Covid-19 Pandemic: A Phenomenological Study.” Early Childhood Education Journal, doi:10.1007/s10643-021-01153-w.