Abstract

Peer work with people with disability often engages people with lived experience of disability to address social exclusion and isolation experienced by their focus people. This paper discusses findings that are part of a project evaluation wherein peer workers with varied disabilities aimed to support focus people to make community connections for their focus people. Focus people lived in disability group homes in regional New South Wales, Australia, after relocating from a large-scale institution. All lived with complex support needs. Using qualitative methods, researchers interviewed seven peer workers over twelve months about their peer work experiences. Drawing on reflexive thematic analysis the authors argue that successful peer work with people with disability must acknowledge interdependencies across individuals’ identities as people with disability, the environment in which peer work takes place, the structure of support around peer workers, and the systemic drivers of social exclusion.

Points of interest

Peer workers identified with their focus people’s disability, were empathetic towards them and confident about making connections with their community;

Peer workers experienced ableist attitudes toward them and their focus people from staff in disability group homes;

Peer workers struggled to learn about and to communicate with focus people who had complex communication access needs;

Peer work objectives were modified to refocus on personal peer worker relationships rather than the project’s original objective of making community connections;

Peer workers made positive connections with their focus people by spending time with them and joining them in activities;

The research demonstrates interdependencies in peer work with people with disabilities, involving peer workers’ identification with disability, the peer work environment, the peer work model, and systemic drivers of social exclusion.

Peer work has origins in notions of advocacy, equality and mutuality in the peer relationship (Bellingham et al. Citation2018). Peer work models vary in their objectives, structure, formality, and modes of interaction with focus people (Watson Citation2019; Shaw et al. Citation2020). The most common feature across peer work models is peer workers’ lived experience, wherein peer workers seek ‘to share power and increase mutuality within relationships’ (Watson Citation2019, 685). However, systemic imperatives such as government funding conditions or organisational cultures have driven formalisation of the role, with some researchers arguing there is tension between the social role intended for peer workers and the ‘institutionalisation’ of the model (Gardien and Laval Citation2019; Voronka Citation2019). Evaluations of peer work in mental health have commonly found the role and identity of peer workers remains unclear (Gardien and Laval Citation2019; Walsh et al. Citation2018). Voronka (Citation2019), argued that the paid peer worker model has changed the meaning of ‘peer’ from a personal relationship to a professional one. In so doing, peer workers’ identity and authenticity is challenged and co-opted into the ‘inclusion imperative’ (Voronka Citation2019, 565). This position argues that those whose status and identity has historically been marginalised, and who are usually invisible and stereotyped by society, are expected as peer workers to access sufficient power to resist structural ableism. Voronka (Citation2019) argued peer workers are commodified and marginalised both in identity and in work practice. They experience a representational paradox whereby, ‘in order to be successful in their roles, they need to be or become recognizable by both professionals and participants as a peer’(Voronka Citation2019, 574). This positions peer workers as a ‘socio-political phenomenon’ (Voronka Citation2019, 565) that requires representational authenticity and workplace authority and fails to challenge systemic marginalisation. Many researchers have argued that peer workers occupy a ‘liminal space’ (Solomon Citation2004, 684) between friend and worker, or between service user and service provider or between those who are included and those who are stigmatised (Watson Citation2019). Gardien and Laval (Citation2019) described this as ‘the institutionalisation of a social role … which is built on largely informal and/or unrecognised experiential knowledge’ (Gardien and Laval Citation2019, 71).

Compared with peer work in the field of mental health, peer work with people with disability has focused less on outcomes such as recovery (Watson Citation2019) and more on shared experiences of ableism and social exclusion (Mahoney et al. Citation2020; Marks et al. Citation2019). Social exclusion is dynamic and relational, produced by the interactions of social, cultural, and political systems beyond the immediate environment in which people live (Adam and Potvin Citation2017). Peer work models based on this perspective are likely to reflect the biopsychosocial model of disability (Shakespeare Citation2013) which positions social exclusion as not a personal attribute, but rather a consequence of historical and current exclusionary mechanisms that have limited access to rights, resources and capabilities (Adam and Potvin Citation2017). In Australia, disability rights are embedded in a political discourse that denies people with disability their rights to self-determination and uses institutions to drive the redistributive mechanisms that shape disability support structures, thereby subverting intentions towards inclusion (van Toorn and Soldatic Citation2015). In this context peer work with people with disability may mostly be concerned with ‘perforating the boundaries’ of the ‘distinct social space’ (Clement and Bigby Citation2009, 265) occupied by people with disability living in disability group homes.

This paper examines findings from the evaluation of a peer worker project aiming to foster community connections for people with disability and complex support needs. The focus people receiving visits from peer workers have a long history of prior institutionalisation and social exclusion and now live in smaller disability group homes in the community. The group home environment is not conducive to social inclusion of people with disability, with financial systems and management procedures that focus on regulatory obligations rather than care and support, staff training that places little priority on person-centred practice, and informal practices adopted by relatively autonomous support workers in the absence of clear guidelines (Clement and Bigby Citation2010). Additionally, research suggests that for some people who are relocated into disability group homes from large residential institutions, largely people with profound disabilities, there is little change in their exercise of choice and control (Stancliffe and Abery Citation1997). People who live or who have lived in large residential centres typically have a range of complex support needs often related to long term deprivation and social exclusion and frequently lack family and other informal support networks to assist them to navigate their daily lives and take part in their communities (Angell et al. Citation2020).

Communication

Most focus people supported by the peer worker project have complex communication access needs. People with complex communication access needs, or who communicate informally may be misunderstood or ignored by communication partners (Collier, Blackstone, and Taylor Citation2012). Their rights to choice and control in their lives is a centralised principle within the United Nations Convention on Persons with Disabilities [UNCRPD] (United Nations Citation2006), as are their rights to supported decision-making (Watson Citation2016). It is the role of supporters of people with disabilities ‘to respond to the expression of will and preference of those they support’ (Watson Citation2016, 5). The research literature confirms that when supporters perceive the person they are supporting is capable of self-determination, they are more likely to guide the person to express their choice (Watson Citation2016). Conversely, negative assumptions about decision-making capacity have the effect of reducing opportunities for expressions of will and choice. (Watson Citation2016).

The peer work in this project therefore intersects with four external factors: a disability support model (disability group homes), that has often been associated with ‘dependence, segregation and infantilisation of disabled people’ (Scott and Doughty Citation2012, 1012); historical contributors to social exclusion such as previous institutionalisation and absence of family connection; the complex communication access needs of focus people; and the project’s fixed-term funding model.

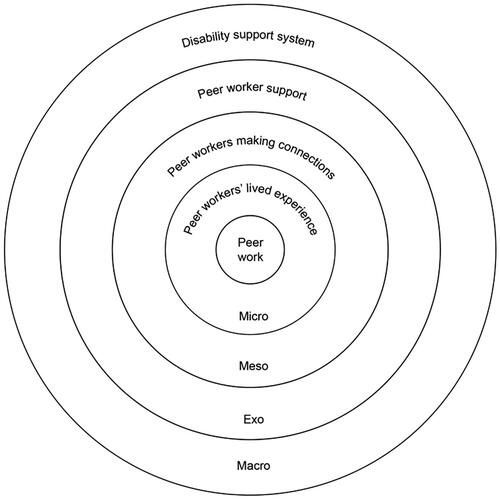

The peer workers brought to their work their lived experience of disability and their intentions to make community connections for and with their focus people. Little is known about the subjective experiences of peer workers with disability working within such a complex environment. The researchers realised that the strength of the proximal processes impacting upon the peer work model warranted the use of an ecological framework (Bronfenbrenner Citation2000) to crystalise findings within sectors and to understand cross-sector interdependencies. Bronfenbrenner (Citation2000) argued that personal characteristics and sociodemographic factors interact with environmental systems surrounding them. He classified ecological systems as micro (the individual and direct social influences), meso (interactions between two or more microsystems), exo (factors that indirectly impact the individual), and macro (societal culture, norms and laws) (Crosby et al. Citation2017). Each system is nested dynamically within the remaining 3 systems, interacting and leading to ‘changes in subjective understanding of the different contexts/systems’ (Kamenopoulou Citation2016, 516). Bronfenbrenner argued that research design using ecological systems theory

must provide a structured framework for displaying the emergent research findings in a way that reveals more precisely the pattern of the interdependencies (Bronfenbrenner Citation2000, 131).

In this paper we argue that the above intersecting contexts are present in the peer worker model and create interdependencies across ecological systems that must be met for peer workers with disability to assist their focus people. This paper reports on the evaluation of a peer worker model and explores interdependencies in the model and their impacts upon peer worker experiences.

Method

Study design

The objective of the evaluation was to identify factors in the peer worker model that impact on the skills, attitudes, confidence and understanding of peer workers and group home staff so that it could be developed into a replicable model. The model is currently being trialled by a disability organisation in regional New South Wales, Australia, with people with complex support needs who live in group homes managed by three different community-based organisations, and who had previously been relocated after living for decades in a large residential care centre.

Ethical approval for the study was provided by the Human Research Ethics Committee on 13 September 2021 at Deakin University] (HEAG-H 2021-273).

This paper draws on data collected as a part of an evaluation of the Peer Worker project. As such, the research team comprises fourresearchers, Dr Sue Taylor, Dr Louisa Smith, Professor Angela Dew and Dr Joanne Watson, Deakin University, Elizabeth Farrant, a Masters’ student supervised by Dr Louisa Smith, and co-researcher Debra Hamilton. Four researchers, Sue Taylor, Louisa Smith, Angela Dew and Joanne Watson do not have lived experience of disability but have extensive experience of working in the field of disability and doing disability research. The co-researcher lives with a disability. The team worked collaboratively with the disability organisation to co-design key evaluation aims, methods and desired outcomes. Some peer workers held other roles within the organisation and were involved in the co-design process. Other peer workers were not directly consulted in the co-design but the disability organisation itself encouraged peer worker input through project communication structures. Researchers approached the evaluation as both developmental and summative. As such, it was intended that three interviews with each peer worker would be conducted at three monthly intervals to evaluate the stages of the project.

The evaluation sought new knowledge requiring an in-depth understanding of peer workers’ experiences, most accessible using qualitative rather than quantitative approaches (Fossey et al. Citation2002). The researchers were guided by social constructivism throughout the study, particularly in data analysis, not seeking objective ‘truth’ about the research questions, but instead seeking to enter participants’ worlds to understand their subjective experiences. Social constructivism methodology starts from an ontological position that accepts that everyone’s reality is relative, and that each individual interprets reality according to their own experiences (Lincoln and Guba Citation2013). The researcher engages dialectically with the data in order to reconstruct or construct a shared social reality through which social phenomena may be differently understood, and conflicting paradigms or constructions may be challenged (Lincoln and Guba Citation2013). Social constructivism is primarily concerned with ‘social processes and the social construction of meaning’ (Braun and Clarke Citation2022, 2). The researcher is not an outsider in the construction of meaning but explores participants’ and other stakeholders’ ontologies and epistemologies in particular contexts. This reflexive approach to the evaluation of the peer worker project enables an understanding of what each research participant brings to peer work and the evaluation data in terms of their unique life experience as a person with disability. Analysis was aided by regular discussion of research findings with the disability organisation, which included people with disability, some of whom were also peer workers in the project.

Recruitment and participants

Seven peer workers joined the project over the evaluation period. All were informed about the evaluation by the organisation, with clear statements about not being required to participate. All participated in the evaluation. Participants provided written consent. Two peer workers withdrew from the project after the first interview, one of whom provided a follow-up interview prior to leaving. Both agreed to the ongoing use of their interview data. Participants ranged in age from mid 30s to mid 50s. Two participants were male and five were female. Following the biopsychosocial model of disability, which allows acknowledgement of limitations imposed by impairment (Scambler Citation2004; Johnston Citation1997), we asked participants to describe their disability in order to better understand their interactions with the focus people they visited. Participants’ self-described disabilities included cerebral palsy as well as complex communication access needs and/or wheelchair use, autism, deafness and blindness. The focus people all lived with complex communication access needs as well as various mobility, neurodiverse, vision and hearing disabilities.

Data collection

Each peer worker was interviewed between one and three times during the evaluation, depending upon their commencement or exit dates. Participants were interviewed by one researcher each time, with the first author [ST] conducting 11 interviews and second author [LS] conducting three. A second interviewer, [EF], a Masters student researching peer work by people with disability, participated as an interviewer with either ST or LS during three of the interviews. In the first round of interviews, the interview guide was the same for all participants. Questions explored participants’ motivation to be a peer worker, their hopes for what they might achieve in the role, their perceptions of their skills and strengths in the role, how they anticipated communicating with and getting to know focus people with little or no natural speech, their perceptions of relationships between them and other peer workers and with the disability group home staff, and what support they expected from the disability organisation managing the project. Interviews concluded with questions about their anticipated enjoyment of the peer worker role, challenges they might face and things they thought they may learn as a peer worker. The guide was sent to all participants before the interview, so that they could prepare in advance. This was advisable because three of the participating peer workers lived with complex communication access needs and needed time to prepare their responses. Alice communicated using a speech generating device, Christine lived with vision impairment and Evelyn lived with hearing impairment and communicated using Auslan and/or an interpreter. The second and third interviews followed up on issues raised by participants in their earlier interviews and therefore varied across participants. Again, the interview guide was sent to participants ahead of the interview.

In consultation with researchers, participants chose the method by which they were interviewed. Three initial interviews were conducted face to face. Researcher ST has experience in interviewing people who use speech generating devices to communicate (SGD). ST allowed sufficient time for the participant to respond to questions using her SGD and diverged as little as possible from the questions sent to the participant ahead of the interview to avoid fatiguing the participant. After one of the participants indicated in his first interview that he enjoyed using Talking Mats™, researcher (LS) suggested he may like to communicate using Talking Mats™. Talking Mats™ is a tool that establishes a partnership structure around a topic, with a visual framework using specially designed picture communication symbols that are manipulated by the person with complex communication access needs to express choices, opinions or ideas (Talking Mats Australia Citation2023). LS – who is trained in using Talking Mats – developed a specific set of visual cards from Talking Mats to support the second interview with this participant. The participant who was vision impaired was able to use her screen reader to read the interview questions. The participant who was deaf used an AUSLAN interpreter for her interview. Subsequently interviews of all participants were conducted via an online audio-visual platform because the geographic distance between researchers and participants precluded ongoing face to face interviews. Interviews averaged an hour in time, with very little variation across participants. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed by a transcription company. Interview transcripts were sent to all participants to enable them to add further comment and to suggest edits if they disagreed with the transcripts. No changes to transcripts were requested.

Adjustments and delays to project implementation caused the disability organisation, project staff (including some peer workers) and the researchers to liaise closely about impacts upon the project and upon the evaluation. Elements of the project changed considerably, challenging project staff. For instance, the program of peer work visits to focus people had to cease twice because of COVID19 restrictions in social contact. Also, interviews with peer workers for the evaluation were delayed by COVID19 because peer work activity had temporarily stopped. Reflections on the consequences of project changes were critical to evaluation findings. As a result, it was agreed both by researchers and by the disability organisation that project meeting discussions would be included in project data. This amendment to research ethics was approved on 6 May 2021 by Deakin University Human Research Ethics Committee (HEAG-H 2021-273)

Data analysis

The data from individual interviews and meetings between researchers and the disability organisation were entered by ST into NVIVO20™ software for data management and to assist with coding. Despite the use of different communication systems by some participants, the data produced was consistent in depth and reflexivity from all participants, arguably because they were skilled in using their communication methods and devices. No communication difficulties were raised with researchers during or after interviews, either by participants or by the disability organisation. The participant who used an SGD to communicate, as well as the participant who used an AUSLAN interpreter, had pre-prepared some lengthy responses to questions prior to the interview as well as substantial responses during interview. Using the Talking Mat did support the participant to rank different factors that they had discussed in the first interview. Authors ST and LS collaborated on data analysis using reflexive thematic analysis. As summarised by Braun and Clark (Braun and Clarke Citation2022), reflexive thematic analysis uses researcher subjectivity to both immerse the researcher in the data and to allow time for reflection. Themes developed by the researcher are ‘patterns of meaning anchored by a shared idea or concept (central organizing concept), not summaries of meaning related to a topic’ (Braun and Clarke Citation2022, 7). Reflexive thematic analysis allows themes to develop recursively during the coding process, either inductively or deductively, or both (Braun and Clarke Citation2021a). The researcher commences coding early in the data collection and analysis process, and develops themes iteratively (Braun and Clarke Citation2021b). Because the researcher is a resource in the analysis and knowledge production process researcher subjectivity and contextuality of the research is accepted (Braun and Clarke Citation2021a).

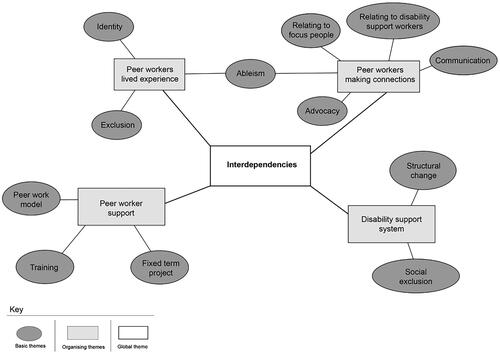

Following the method used by Attride-Stirling (Attride-Stirling Citation2001) thematic network analysis was used to organise the data into codes and themes according to a hierarchy of Basic Themes, Organising Themes and Global Themes (). After initial analysis, the researchers organised themes into a framework based on ecological systems theory (Bronfenbrenner Citation2000) (). The ecological framework was used to map the interdependencies that shape peer worker experiences.

Coding procedures

The first author coded the data line by line to identify groups of codes that contributed to themes. First round, second round and third round interview data were coded independently to track any thematic progression. demonstrates how codes and themes connect to show interdependencies in the data. Themes were then positioned within an ecological systems framework for further analysis ().

Results

Analysis indicated clusters of organising themes around stories of peer worker relationships and connecting with contextual matters such as the peer worker model, the disability support system, and structural influences. The ecological framework clarified the interactions and interdependencies that impact upon peer workers. Below we discuss findings in terms of the ecological framework. The people with disability who were the subject of peer worker visits are referred to throughout this paper as focus people. The names of peer worker participants have been anonymised below to ensure confidentiality.

Microsystem: peer workers’ lived experience

All peer workers had lived experience of disability, including mobility impairment, blindness, deafness, cerebral palsy, and complex communication access needs. Everyone had personal and professional experience of peer work prior to joining the project. Most spoke of experiencing discrimination and exclusion in their lives because of their disabilities. Some had experienced segregated schooling, and some had not been treated well when younger by their families and communities. This perhaps contributed to their empathy for those they were supporting and their awareness of the powerlessness experienced by their focus people:

I can appreciate what it’s like to lose or never have a sense of self. (Andrew, interview 1)

I think I have to offer having a go and try anything, patience and understanding of being non-verbal. (Alice, interview 1).

The lived experiences of the people we’re supporting … are my experiences. (Andrew, interview 1)

Everyone with lived experience even of the same disability is going to be different, but still having that foundational knowledge there. (John, interview 1)

Peer workers lived independently with support and only one (John) had experience of disability group homes. Their reactions to the disability group home environment in which their focus people lived were emotional:

I was naïve before, it’s been a shock to the system to realise the house is really an institution. (Diane, interview 2)

It’s about the fact that they’re disconnected from their society…seeing these peoples’ lives be so mapped out for them. (Barbara, interview 1)

The experience of someone who is not in an institution compared to someone who is in an institution is vastly different. We’re the same but we have very different experiences. (Andrew, interview 1)

Mesosystem: peer workers making connections

Peer workers were expected to develop a relationship with their focus people in the unfamiliar and difficult environment of disability group homes, where there was little support for or even understanding of their role. Arrangements for their visits were often not communicated across group home staff, and so they were often unexpected and/or unwelcome when they arrived. At times they had to leave without seeing their focus person because the group home routine did not accommodate their visit. These obstacles suggested general (but not total) lack of respect for and acceptance of the Community Connections Project by group home management and staff. Project staff discussed with researchers the frustrations caused by gatekeeping and collective risk management in group homes, as well as the delays caused by COVID19 shutdowns. The Project Manager expressed her frustrations that despite structures and systems in place, the objective of the project – ‘to just get alongside people and be human together’ – had been difficult to achieve.

Peer workers had to manage lack of respect and ableism in negative responses by disability group home support workers towards themselves and their focus people.

they’ll say ‘what group home do you come from? (Andrew, interview 1)

they don’t think the same as we do, they often say stuff [like] ‘it was easier when we were in the institutions’ (Alice, interview 1).

Peer workers spoke of struggling with the challenge of advocating with disability support workers for their focus person in relation to the person’s care and support. For instance Christine, Andrew, and Evelyn were upset when they separately witnessed group home practices that were disrespectful of their focus person:

it was a really incredible piece of evidence that the devolution was as bad as we thought, it was unfortunately evidence that it’s not working for people. (Christine, interview 2).

there is something that happened the last week, that I was extremely concerned about, and I brought it up with [project manager] already. (Andrew, interview 1)

I had a particular visit with [focus person] that was particularly hard. It was just not a nice experience and that one quite upset me, and I actually was beating myself up quite a bit about the fact that it really upset me. (Evelyn, interview 1)

We find if you push the group homes too far or if you cause too much paperwork, they will just close the door and we’ll never get back in there again. (Andrew, interview 1).

There was no clarity in the exchange of information between disability group homes and the project about whether focus people had undergone speech assessments or had communication profiles to clarify how they communicated. It was also unknown to the project in advance whether any focus people had experience of using communication aids such as augmentative and alternative communication devices. The way disability group homes communicated with their focus people upset some peer workers:

that’s been quite distressing for me to witness because what I’m seeing is the person saying, “I’m trying to say something here,” and no one around her is listening or not taking her seriously. (Barbara, interview 1).

He communicates if he wants to send a positive communication to you he will hold your hand, so we do that a lot. If he’s upset, he’ll try and grab you and pull you in and he did that to me the first time. (Andrew, interview 1)

…to understand that no means no, however sometimes no means ‘not today’ or ‘I don’t like it that way’ and ‘I want to try it again another way’. Again, we need to listen, I think that is most important. (Alice, interview 1).

[my focus person] and myself now have gotten to a place where no matter what’s going on in the group home or in my life, we are both present in that time. (Andrew, interview 2).

The other day I had her one on one, it was awesome, I feel she actually wanted me there. (Alice, interview 2).

Some peer workers witnessed good disability support practices in the group homes in which their focus person lived:

With the new woman her community participation worker is awesome she loves to share everything about the woman, especially around her communication. (Alice, interview 2).

Diane tried similarly to help her focus person to express ‘yes’ or ‘no’ and exert some choice and control in her day-to-day decisions by introducing her to a yes/no button to express herself. However, despite her focus person using the device it was disregarded by support workers. Evelyn, who lived with hearing impairment, hoped to introduce AUSLAN (Australian sign language) to her focus people and also to engage support workers to learn AUSLAN.

I know that there are a lot of people out there in group homes that don’t have staff who communicate with them well. It’s so disappointing to see, so I’d like to see more staff take it up but that’s not something I can really enforce. But it is disappointing to see these individuals living in their own homes in such isolation. (Evelyn, interview 1).

Communication was therefore an ongoing challenge for peer workers that they met with persistence.

For most peer workers the primary objective of the peer work, to establish community connections with and for their focus person, was difficult. Peer workers’ goals for activities that might facilitate communication and bring community connection included baking, making jewellery, listening to music, and playing on a piano. However, peer workers found it took a longer time than anticipated to get to know their focus people before they could start to develop goals with them. Recognising this over time, peer workers placed less emphasis on developing goals for their focus person and more emphasis on the peer relationship. For most peer workers, the relationship became the goal.

As a team we have done a lot of thinking. What’s more important? Spending time with people to get to know who they are, or objectives? (Alice, interview 2)

Peer workers were confronted by the challenges of ableism, limited agency, communication barriers and project interruptions but found support in formal and informal peer worker-to-peer worker support and project supervision.

Exosystem: peer worker support

The project had a fixed term of eighteen months, after which project funding was to cease. The original project design was for peer workers to use person centred workshops to train the support teams who support the focus people in their disability group homes to plan for community connections. The objectives of the training were for disability support workers to better understand their role in supporting people living in the group home, and to develop strategies and tools to support them to make community connections. However, the onset of COVID19 and its impact on disability group home residents and staff meant this component of the project was dropped and was ultimately introduced close to the end of the project through a parallel project which was not part of this evaluation. As a result, the project finished with no prospect of reliable formal continuing support for the focus people’s community connections by disability support workers. Peer workers were disappointed, but philosophical, about the prospect of support for focus people being abruptly withdrawn. Their perspective was that the interruptions to the project had meant visits were not reliable, and it was unclear what the focus people had been told about what was happening. They thought this was likely to be the case again when the project ceased:

It isn’t like we’ve been going every week for 3-4 years. If some of them miss seeing us. You know however they don’t know us well. Are they told we aren’t coming? Do they know what they are missing? Some would, not everyone… the negative is the stop and start nature of the project … Every week is different. (Alice, interview 2).

When this project is over, I don’t want there to not be any connections anymore, she needs to have people so that this doesn’t just finish. (Diane, interview 2).

Peer workers were encouraged by formal aspects of the peer work model such as payment of peer workers, peer worker supervision and Community of Practice to consider themselves to be professional peer workers. Indeed, when asked, Alice was adamant that their role was more professional than personal. Nonetheless, aspects of the model suggest an informal peer worker model, primarily due to the lack of peer worker training. The project’s approach was to individualise training with each peer worker in relation to the focus person they were supporting. However, some peer workers expressed the need for training in trauma-informed responses to their focus people, in working more effectively with disability support staff, and communicating with focus people who have complex communication access needs.

There needs to be a lot of capacity building around preparing an employee to be a peer worker … I think your lived experience is only valuable if you can communicate or put that into practice in an environment. (Andrew, interview 2).

So you’ve got to have that skill building, training. You’ve got to have sort of complex training, dealing with people who have no communication, so having that training in communication. (John, interview 1).

Conversely, the Project Manager and some peer workers preferred peer workers to prioritise their lived experience and ability to ‘trust their capacity for a hunch’ (Meeting notes, 03/03/2022) in conducting their peer work. In line with this philosophy, the peer worker role was not formalised by the organisation, neither were there guidelines for peer workers in relation to practices such as advocacy with group homes on behalf of focus people, safety of peer workers, and mandatory reporting responsibilities. Peer workers were encouraged to practice in the way that suited them, with guidance from the Project Manager, who often joined peer workers when they visited focus people.

Peer workers were supported in their work by their relationships with other peer workers. Peer workers debriefed with each other either formally or informally.

it’s my experience that there’s pretty much always a really lovely relationship between peer workers. (Christine, interview 2).

I work with some of the most fantastic people I’ve ever met I’m very lucky, we’re all very lucky to have each other. That’s why peer work is so good… (Alice, interview 3)

Macrosystem: disability support system

Some peer workers expressed strong view about governments’ history of placing people with disabilities in institutions:

The doctors telling parents to put children with disabilities in institutions straight away. I don’t know where that comes from… (John, interview 1)

… maybe leaving some structural changes in place in the group homes. (Andrew Interview 1)

I would like to see more engagement with the house staff to be able to create changes from the inside and challenge those assumptions and misconceptions about the people in the group homes that they [group home staff] have. (Barbara, interview 1)

Peer workers were sensitive to the extreme isolation and social exclusion experienced by their focus people, who had little or no contact with their families or anyone outside their group home:

they’ve been so disenfranchised with their own family [by] being put in institutions… (Barbara, interview 1)

Their lives have been stolen from them. (Barbara, interview 3).

Discussion

An ecological systems framework clarifies interdependencies that either empower or disempower peer workers using their lived experience for the benefit of their focus people. The power, authority and agency of the disability group home environment presented challenges to the peer worker project and to the peer workers themselves. This was accentuated by the informality of the peer worker model. The challenge came largely from the culture of a disability service system that has contributed to the social isolation of the focus people (Clement and Bigby Citation2010; Stancliffe and Abery Citation1997). Our findings confirm previous research in the mental health area that peer workers find themselves in a liminal space between their focus people and the professionals alongside whom they work (Watson Citation2019; Solomon Citation2004). In this instance, liminality applied both to the disability organisation and the individual peer workers. Although peer workers were employed by the disability organisation, their work occurred in isolation from their disability colleagues and within an unreceptive group home environment. Peer workers perceived and reacted to the extreme lack of choice and control experienced by their focus people, and the apathy of most disability group home support workers toward their peer work and toward their focus people. The peer work project was based on the belief, shared both by the disability organisation and the peer workers themselves, that lived experience of disability is the key attribute needed for peer work. However, peer workers were unprepared for the impact upon themselves and their focus people of the group home environment. Consequently, the objective of the peer work, to make community connections with and for their focus people within the limited timeframe of the project, was by default replaced by an objective of getting to know their focus people by spending time with them. The challenge faced by peer workers was accentuated by their own personal histories of marginalisation and the dilemma of wanting to, but being unable to, confront systemic barriers. The project was not designed to challenge structures in the disability support system, but rather to ameliorate the isolation of their focus people – referred to by Voronka as the ‘inclusion imperative’ (Voronka Citation2019). Added to this was the project’s equivocal position on the extent to which peer workers should advocate for their focus people. Peer workers therefore drew on the support of each other and the Project Manager to maintain their strength and commitment.

Effective peer work was dependent upon peer workers being empowered in several ways that did not occur because of project design. Firstly, their lack of orientation to the group home environment, introductions to support workers, or the establishment of respectful relationships. Secondly, they were not always assisted by the Project Manager or group home Managers to gain access to knowledge about their focus people’s likes and dislikes and how they communicated, which would have allowed peer workers to make the best use of the limited time they had in the project. Thirdly, informality in many aspects of the project, such as peer workers’ rights of access to their focus people and approaches to peer worker training, impeded relationship building and peer worker safety. Additionally, the planned training for disability group home support workers about making community connections may, if it had gone ahead, have contributed to an understanding by support workers about the value of the peer worker project, the skills brought to the project by peer workers, and the benefits to the focus people of making community connections.

Peer workers experienced disability group homes as places where the normative values that dominate societal power structures prevail. They were confronted by ableism towards themselves, and experienced little or no differentiation between themselves and their focus people, which caused them to reflect on their self-perceptions. Resistance is an option for exercising agency when opposing dominance and oppression. Crenshaw (Citation1991) argued that identity is a site of resistance, and that ‘the most critical resistance strategy for disempowered groups is to occupy and defend a politics of social location rather than to vacate and destroy it’(Crenshaw Citation1991, 129). Whilst they felt they were unable to make structural change in the group home environment, peer workers resisted being marginalised in the disability group homes they visited and used their presence in the environment try to raise awareness about the rights and competencies of their focus people. They were better able to do so when they drew strength and affirmation from supervision and from peer worker to peer worker support. Peer workers were also able to perceive that they had made some differences to their focus people’s lives. Some perceived small changes in aspects of group home support for their focus people, which validated peer workers’ intuitive understanding that patience and persistence were necessary ingredients, perhaps a reflection of their own life experiences.

The ecological framework used in this analysis underscores the liminality of the peer worker project and the incremental impacts upon peer workers of the environment within which they worked and the challenges they faced in making personal connections with their focus people. The framework also helps to identify the pervasive impact of systemic factors throughout all aspects of the peer worker project, from the fixed term nature of project funding through to the limitations imposed by the disability service system and isolation of those who depend upon it. The framework also clarifies ways peer workers used their common lived experiences of exclusion but also of persistence to find ways to support each other and to establish relationships with their focus people. For public policy to expand the capabilities of people with disability these interdependencies and their positive and negative effects on systems, environments and people must be better understood. Rather than fixed term funding of peer worker projects such as this, recurrent funding would remove time pressures that impose false dichotomies in peer worker practice of choice between getting to know their peers properly and finding sustainable ways to make community connections.

Limitations

As discussed above, COVID-19 lockdowns impacted severely upon the project, with extensive periods of time during which no visits to focus people were possible. Breaks in the project meant evaluation data collection was paused, which ultimately reduced the amount of data reported in this paper. Recruitment of peer workers was also interrupted by project breaks.

Conclusion

Paradoxically, deficits in the disability service system were drivers for the peer worker project but were also barriers making it difficult for peer workers to achieve community connections with and for their focus people. The informal peer work model that was adopted presupposes skill, empathy, and self-confidence on the part of peer workers, but also a high level of organisational support to ensure peer workers with diverse and varied disabilities are accommodated by the environment in which they work, are physically and emotionally safe, and are equipped to communicate with their focus people. Added to this was a fixed term and short-term funding model that placed pressure on peer workers. All human interaction contains interdependencies, and this is especially important when the intent is to ‘perforate a boundary’ (Clement and Bigby Citation2009, 265) in an institutionalised model of care. Peer workers experienced these interdependencies across their identities as people with disability, the environment in which peer work took place, the structure of support around them, and the systemic drivers of social exclusion that are part of their daily experience.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no declarations of conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adam, Caroline, and Louise Potvin. 2017. “Understanding Exclusionary Mechanisms at the Individual Level: A Theoretical Proposal.” Health Promotion International 32 (5): 778–789. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daw005

- Angell, A. M., L. Goodman, H. R. Walker, K. E. McDonald, L. E. Kraus, E. H. J. Elms, L. Frieden, A. J. Sheth, and J. Hammel. 2020. “Starting to Live a Life": Understanding Full Participation for People with Disabilities after Institutionalization.” The American Journal of Occupational Therapy: Official Publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association 74 (4): 7404205030p1–7404205030p11. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2020.038489

- Attride-Stirling, Jennifer. 2001. “Thematic Networks: An Analytic Tool for Qualitative Research.” Qualitative Research 1 (3): 385–405. https://doi.org/10.1177/146879410100100307

- Bellingham, Brett, Niels Buus, Andrea McCloughen, Lisa Dawson, Richard Schweizer, Kristof Mikes-Liu, Amy Peetz, Katherine Boydell, and Jo River. 2018. “Peer Work in Open Dialogue: A Discussion Paper.” International Journal of Mental Health Nursing 27 (5): 1574–1583. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12457

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2021a. “Can I Use TA? Should I Use TA? Should I Not Use TA? Comparing Reflexive Thematic Analysis and Other Pattern-Based Qualitative Analytic Approaches.” Counselling and Psychotherapy Research 21 (1): 37–47. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12360

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2021b. “One Size Fits All? What Counts as Quality Practice in (Reflexive) Thematic Analysis?” Qualitative Research in Psychology 18 (3): 328–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2022. “Conceptual and Design Thinking for Thematic Analysis.” Qualitative Psychology 9 (1): 3–26. https://doi.org/10.1037/qup0000196

- Bronfenbrenner, Urie. 2000. “Ecological Systems Theory.” In Encyclopedia of Psychology, Vol. 3, edited by Alan E. Kazdin and Alan E. Kazdin, 129–133. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, Oxford University Press.

- Clement, T., and C. Bigby. 2010. Group Homes for People with Intellectual Disabilities: Encouraging Inclusion and Participation. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. Book.

- Clement, T., and C. Bigby. 2009. “Breaking out of a Distinct Social Space: Reflections on Supporting Community Participation for People with Severe and Profound Intellectual Disability.” Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 22 (3): 264–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3148.2008.00458.x

- Collier, Barbara, Sarah W. Blackstone, and Andrew Taylor. 2012. “Communication Access to Businesses and Organizations for People with Complex Communication Needs.” Augmentative and Alternative Communication (Baltimore, Md.: 1985) 28 (4): 205–218. https://doi.org/10.3109/07434618.2012.732611

- Crenshaw, Kimberle. 1991. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color.” Stanford Law Review 43 (6): 1241–1299. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039

- Crosby, Shantel D., Carl L. Algood, Brittany Sayles, and Jayne Cubbage. 2017. “An Ecological Examination of Factors That Impact Well-Being among Developmentally-Disabled Youth in the Juvenile Justice System.” Juvenile and Family Court Journal 68 (2): 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfcj.12091

- Fossey, Ellie, Carol Harvey, Fiona McDermott, and Larry Davidson. 2002. “Understanding and Evaluating Qualitative Research… Second Article in an Occasional Series.” The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 36 (6): 717–732. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1614.2002.01100.x

- Gardien, Eve, and Christian Laval. 2019. “The Institutionalisation of Peer Support in France: Development of a Social Role and Roll out of Public Policies.” L’institutionnalisation de l’accompagnement par les pairs en France: entre développement d’un rôle social et déploiement de politiques publiques (French) ALTER, European Journal of Disability Research,13 (2): 69–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alter.2018.09.002

- Johnston, Marie. 1997. “Integrating Models of Disability: A Reply to Shakespeare and Watson.” Disability & Society 12 (2): 307–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599727407

- Kamenopoulou, Leda. 2016. “Ecological Systems Theory: A Valuable Framework for Research on Inclusion and Special Educational Needs/Disabilities.” Pedagogy (0861-3982) 88 (4): 515–527.

- Lincoln, Yvonna S., and Egon G. Guba. 2013. The Constructivist Credo. Walnut Creek, CA: Routledge. Book.

- Mahoney, Natasha, Nathan J. Wilson, Angus Buchanan, Ben Milbourn, Ciarain Hoey, and Reinie Cordier. 2020. “Older Male Mentors: Outcomes and Perspectives of an Intergenerational Mentoring Program for Young Adult Males with Intellectual Disability.” Health Promotion Journal of Australia: Official Journal of Australian Association of Health Promotion Professionals 31 (1): 16–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpja.250

- Marks, B., J. Sisirak, R. Magallanes, K. Krok, and D. Donohue-Chase. 2019. “Effectiveness of a Health Messages Peer-to-Peer Program for People with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities.” Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 57 (3): 242–258. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-57.3.242

- Scambler, Graham. 2004. “Re-Framing Stigma: Felt and Enacted Stigma and Challenges to the Sociology of Chronic and Disabling Conditions.” Social Theory & Health 2 (1): 29–46. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.sth/8700012

- Scott, Anne, and Carolyn Doughty. 2012. “Care, Empowerment and Self-Determination in the Practice of Peer Support.” Disability & Society 27 (7): 1011–1024. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2012.695578

- Shakespeare, Tom. 2013. Disability Rights and Wrongs Revisited. [Electronic Resource]. 2nd ed. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis.

- Shaw, Robert B., Sarah V. C. Lawrason, Kendra R. Todd, and Kathleen A. Martin Ginis. 2020. “A Scoping Review of Peer Mentorship Studies for People with Disabilities: Exploring Interaction Modality and Frequency of Interaction.” Health Communication 36 (14): 1841–1851. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2020.1796293

- Solomon, Phyllis. 2004. “Peer Support/Peer Provided Services Underlying Processes, Benefits, and Critical Ingredients.” Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 27 (4): 392–401. https://doi.org/10.2975/27.2004.392.401

- Stancliffe, Roger J., and Brian H. Abery. 1997. “Longitudinal Study of Deinstitutionalization and the Exercise of Choice.” Mental Retardation 35 (3): 159–169. https://doi.org/10.1352/0047-6765(1997)035

- Talking Mats Australia. 2023. "About Talking Mats." Accessed September 1, 2023. https://talkingmatsaustralia.com.au/pages/about-talking-mats.

- United Nations. 2006. "Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities." Accessed April 27, 2018. https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html.

- van Toorn, G., and K. Soldatic. 2015. “Disability, Rights Realisation, and Welfare Provisioning: What is It about Sweden?” Research and Practice in Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 2 (2): 109–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/23297018.2015.1089185

- Voronka, Jijian. 2019. “The Mental Health Peer Worker as Informant: Performing Authenticity and the Paradoxes of Passing.” Disability & Society 34 (4): 564–582. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2018.1545113

- Walsh, Peter E., Sara S. McMillan, Victoria Stewart, and Amanda J. Wheeler. 2018. “Understanding Paid Peer Support in Mental Health.” Disability & Society 33 (4): 579–597. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2018.1441705

- Watson, Emma. 2019. “The Mechanisms Underpinning Peer Support: A Literature Review.” Journal of Mental Health (Abingdon, England) 28 (6): 677–688. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2017.1417559

- Watson, Joanne. 2016. “Assumptions of Decision-Making Capacity: The Role Supporter Attitudes Play in the Realisation of Article 12 for People with Severe or Profound Intellectual Disability.” Laws 5 (1): 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws5010006