Abstract

A global campaign to end “child marriage” has emerged over the last decade as part of growing international commitments to address gender inequities and improve female wellbeing. Campaigns typically assert that young brides have negligible autonomy in the marriage process and that marrying under 18 years has resolutely negative impacts on wellbeing. Yet, surprisingly few studies explore local attitudes towards marriage and its timing within contexts where early marriage is most common. As such our understanding of motivations and potential conflicts of interest leading female adolescents into marriage remain poorly informed by viewpoints of people purportedly at risk. We present an exploratory study of attitudes to early marriage in northwestern Tanzania where marriage before or shortly after 18 years is normative. We use focus group discussions, complimented by a survey of 993 women, to investigate local views on marriage. We explore (i) why people marry, (ii) when marriage is deemed appropriate, and (iii) who guides the marriage process. Contrary to dominant narratives in the end child marriage movement, we find that women are frequently active rather than passive in the selection of when and who to marry. Furthermore, marriage is widely viewed as instrumental in acquiring social status within one’s local community. Our conclusions illuminate why rates of early marriage remain high despite potential negative wellbeing consequences and increasingly restrictive laws. We discuss our results in relation to related qualitative studies in other cultural contexts and consider the policy implications for current efforts to limit early marriage in Tanzania and beyond.

Résumé

Une campagne mondiale pour mettre un terme aux « mariages d’enfants » est apparue ces dix dernières années, dans le cadre de la volonté croissante de la communauté internationale de s’attaquer aux inégalités entre les sexes et d’améliorer le bien-être des femmes. En général, les campagnes affirment que les jeunes mariées ont une autonomie négligeable dans le process matrimonial et que se marier avant l’âge de 18 ans a des conséquences négatives certaines sur le bien-être. Pourtant, il est surprenant que très peu d’études aient exploré les attitudes locales à l’égard du mariage et de l’âge auquel il a lieu, précisément dans les contextes où le mariage précoce est le plus fréquent. C’est ainsi que notre compréhension des motivations et des conflits d’intérêt potentiels conduisant les adolescentes à se marier reste peu étayée par les points de vue des personnes supposées à risque. Nous présentons une étude exploratoire des attitudes à l’égard du mariage précoce en Tanzanie du Nord-Ouest où le mariage avant ou juste après 18 ans est la norme. Nous utilisons des discussions par groupes d’intérêt, complétées par une enquête auprès de 993 femmes sur les idées locales du mariage. Nous souhaitions savoir: i) pourquoi les gens se marient, ii) quand le mariage semble convenable, et iii) qui guide le processus matrimonial. Contrairement au discours dominant du mouvement souhaitant mettre fin aux mariages d’enfants, nous avons constaté que les femmes sont fréquemment actives plutôt que passives dans la décision sur le moment du mariage et le futur époux. De plus, le mariage est largement considéré comme déterminant pour acquérir un statut social dans la communauté locale. Nos conclusions montrent pourquoi les taux de mariage précoce restent élevés, en dépit des conséquences négatives potentielles pour le bien-être et les lois de plus en plus restrictives. Nous examinons nos résultats en rapport avec des études qualitatives apparentées dans d’autres contextes culturels et envisageons les conséquences politiques pour les efforts menés actuellement pour limiter le mariage précoce en Tanzanie et ailleurs.

Resumen

En la última década ha surgido una campaña mundial para poner fin al “matrimonio infantil” como parte de crecientes compromisos internacionales por abordar las inequidades de género y mejorar el bienestar de las mujeres. Por lo general, las campañas afirman que las novias niñas tienen autonomía insignificante en el proceso matrimonial y que casarse con menos de 18 años de edad tiene impactos resueltamente negativos en su bienestar. Sin embargo, sorprendentemente pocos estudios exploran las actitudes locales hacia el matrimonio y cuándo éste ocurre dentro de contextos donde el matrimonio precoz es lo más común. Por consiguiente, nuestra comprensión de las motivaciones y posibles conflictos de interés por los cuales las adolescentes se casan continúa mal informada por puntos de vista de personas supuestamente en riesgo. Presentamos un estudio exploratorio de las actitudes hacia el matrimonio precoz en el noroeste de Tanzania, donde el matrimonio antes o poco después de los 18 años de edad es normativo. Utilizamos discusiones en grupos focales, suplementadas por una encuesta con 993 mujeres, para investigar los puntos de vista locales sobre el matrimonio. Exploramos (i) por qué las personas se casan, (ii) cuándo el matrimonio es considerado indicado, y (iii) quién guía el proceso de matrimonio. Contrariamente a las narrativas dominantes del movimiento por poner fin al matrimonio infantil, encontramos que las mujeres frecuentemente son activas, y no pasivas, en decidir cuándo y con quién casarse. Además, el matrimonio es ampliamente considerado como fundamental para adquirir cierto nivel socioeconómico dentro de la comunidad local. Nuestras conclusiones aclaran por qué las tasas de matrimonio precoz continúan siendo altas pese a las posibles consecuencias negativas para el bienestar y a leyes cada vez más restrictivas. Discutimos nuestros resultados con relación a estudios cualitativos afines en otros contextos culturales y consideramos las implicaciones políticas para los esfuerzos actuales por limitar el matrimonio precoz en Tanzania y más allá.

Introduction

A global campaign to end “child marriage”, defined as marriage under 18 years and overwhelmingly affecting girls and young women, has emerged over the last decade.Citation1 For example, in 2011 Girls Not Brides, a global partnership now including over 1000 civil society organisations, was founded “to accelerate efforts to prevent child marriage”;Citation2 and in 2015 the Sustainable Development Goals pledged to “eliminate all harmful practices, such as child, early, and forced marriage”.Citation3 These activities reflect growing international commitments to gender equality, with attention focusing on South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, where today an estimated 50% and 40% of girls respectively marry under 18 years.Citation1 Humanitarian concern is grounded in the view that young brides lack autonomy and informed consent to marry, and that early marriage initiates a cascade of harmful consequences, including health risks of early pregnancy, low educational achievement, poor mental health, curtailment of economic opportunities, and an elevated risk of intimate partner violence.Citation4–6

Despite increasing concern surrounding “child marriage”, few studies document locally held views surrounding early transitions to marriage in cultural settings where it is most common. Consequently, present understandings of motivations leading to early marriage are arguably more grounded in moral concerns, than in the priorities and experiences of the very people purportedly at risk. This is problematic because the end “child marriage” movement rests on an externally drawn threshold (18 years) demarcating childhood innocence from adult responsibility, largely failing to acknowledge that (i) a strict barrier between “childhood” and “adulthood” depends on material and social conditions commonly absent in low-income nations;Citation7–10 and (ii) in many contexts the majority of “child marriages” occur in later adolescence (i.e. 15–17 years), a time of emerging autonomy.Citation11 We therefore hereafter avoid the term “child marriage”, instead referring to “early marriage”, or “marriage under 18 years” when referring to this threshold.

A small qualitative literature suggests that early marriage is viewed positively in certain situations, or as a logical option given local alternatives.Citation10,Citation12–16 For example, among Kenyan Maasai, some parents view early marriage as a means of securing their daughters’ futures through alliance formation in the face of changing livelihoods and limited opportunities for young girls.Citation13 Parents also report that early marriage protects daughters from social and health risks associated with premarital and/or transactional sex and childbearing.Citation10,Citation13,Citation14,Citation16–20 Moreover, young women sometimes view early marriage as improving their lives by: helping their family and themselves economically;Citation15,Citation16,Citation21 gaining independence or respect within their homes and community;Citation12,Citation14,Citation21 or protecting their health through the limitation of sexual partners.Citation22 Studies also highlight perceived costs to early marriage including violence, power imbalances between spouses, and lack of preparedness for married life.Citation19,Citation23 Collectively, these studies do not negate concerns about negative consequences of early marriage. However, they indicate that in some contexts parents and daughters view early marriage as a strategy of risk-reduction rather than a harmful behaviour.

Here, we explore attitudes surrounding early marriage in northwestern Tanzania, where female marriage before or just after 18 years is normative. The study site offers a not atypical context where early marriage is prevalent but primarily affects adolescents; 30% of 20–24-year-old Tanzanian women marry before 18 years, but the overwhelming majority of marriages take place at 15 years and over.Citation24 Bridewealth is customary, meaning conflicts of interest could arise between parents and daughters over timing of marriage. Early marriage rates have, for example, been shown to increase with extrinsic economic shocks where bridewealth is practiced, with parents presumably marrying daughters early to access capital.Citation25 But divorce and premarital sex and birth are common,Citation26 so marriage transitions may be less pivotal in defining a women’s life course compared to populations where these are less common or acceptable.

Within Tanzania broadly, the legal status of early marriage is in flux. In 2016, after some resistance,Citation27 Tanzania’s high court revised the legal age for marriage for girls from 15 years to 18 years, a move marked as a victory by the end “child marriage” movement. At the same time, it became illegal to marry or impregnate schoolgirls, but without implications for marrying girls/young women not enrolled in school.Citation28 A year later an appeal against the revised marriage age was lodged, citing contradictions with customary law and religious doctrine, and the implementation of the revised law stalled.Citation29 This situation highlights tension between development sector narratives highlighting the harms of early marriage, and cultural values that view it as intolerable only under specific circumstances.

We investigate local attitudes regarding (i) why people decide to marry, (ii) when to marry, and (iii) who decides when and whom a woman should marry. We focus on marriage generally and then timing of marriage specifically because, despite the classification of early marriage as a “harmful cultural practice”,Citation30 marriages before and after 18 years are not locally regarded as distinct forms of marriage. Rather, marriage is a practice which occurs at various ages, and the overwhelming majority of women who don’t marry before 18 years do so soon after. Through this strategy we situate marriages before 18 years within the context of marriage generally, drawing on shared drivers.

Methods

Study site

Our study took place in Kisesa Ward of northwestern Tanzania, 20 km east of Mwanza. Kisesa is the site of a Health and Demographic Surveillance System (HDSS) run by the National Institute of Medical Research (NIMR) which has collected health and demographic data from the local population since 1994.Citation31 We worked within one semi-urban and one rural village. The villages were chosen to capture the extremes of a local rural–urban gradient since views on marital timing may vary with urbanisation, and associated exposures to different ideas and opportunities.

Kisesa residents are primarily Sukuma. The Sukuma make up approximately 15% of the country’s populationCitation32 and are traditionally patrilineal/local. In rural villages, farming and cattle-keeping dominate, while livelihoods in semi-urban areas are diversifying into trading, skilled and unskilled labour.Citation33 Primary school enrolment is nearly universal and approximately 50% of both sexes progress to secondary school, with progression highest in the semi-urban community.Citation33 Poverty is high in the area; half of households are classified as severely food insecure.Citation33

Marriage is nearly universal, and both divorce and remarriage are common.Citation26 Women marry early, though the median age at first marriage has risen over the past half century from 17 to 19 years.Citation34 Marriages take place formally and informally. Formal marriages involve a religious, legal, or traditional ceremony. The majority include bridewealth transfers from husband to in-laws,Citation35 negotiated prior to marriage and paid in money, cows, goats, or other currencies. Payments are typically higher for younger brides.Citation35 Informal marriages describe cohabitation without a ceremony and women’s parents may request “compensation” (a late bridewealth payment) from their daughter’s husband.

Focus group discussions

To understand views surrounding marriage, we conducted four semi-structured focus group discussions (FGD) in September 2017. FGDs were conducted separately with mothers and fathers of young girls (15 years or younger) in each community. FGDs were structured around three main questions: how do people marry; why do people marry; when do people marry? While discussions were allowed to flow, facilitators redirected participants back to the primary themes when discussions strayed too far and asked probing questions to ensure topics had been saturated within the group before moving on. FDGs were recorded digitally, transcribed and translated into English. After each discussion, facilitators and the first author discussed and recorded their first impressions of the FGD.

Participants were identified from eligible men and women from the household survey (see below). Ten to 12 potential participants were recruited per FGD to ensure that six to nine participants attended. Each FGD ended up with 9–11 participants. Male participants’ ages ranged from 30 to 72 years and women’s ages from 23 to 45 years. The majority of participants were famers; a few women identified as entrepreneurs. FGDs lasted approximately 1.5 h and all participants received a 5000 Tanzanian Shilling (∼2.23 USD) compensation.

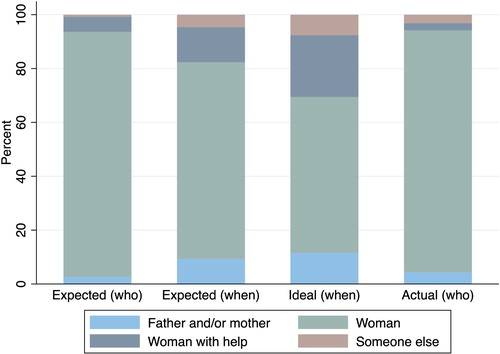

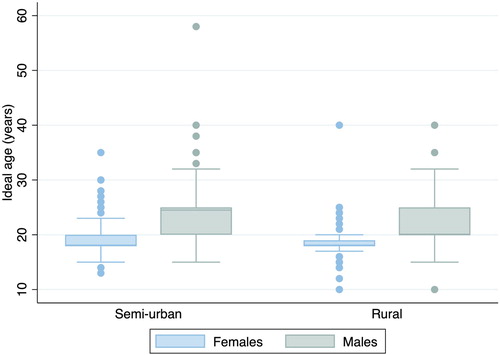

Surveys

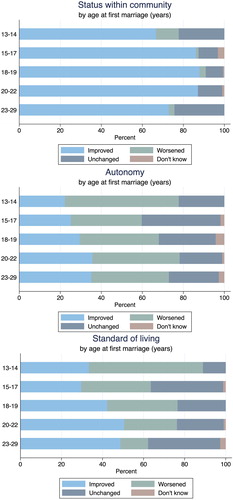

Surveys were conducted in both communities from July through October 2017 to capture women’s attitudes towards and experiences of marriage, and to build a basic demographic profile of Kisesa’s population of young women. We interviewed 993 females aged 15 through 35 years from 743 households selected randomly using the HDSS as a sampling frame. Surveys recorded women’s marital history, and their views surrounding marriage. Women identified the ideal ages for males and females to marry, and who they felt was the correct person to decide when a woman should marry (they were allowed to identify more than one person). Women who had never been married (n = 491), were asked to anticipate who would decide when and who they would marry (if they thought they would marry some day). Women who had ever been married (n = 502) were asked about changes that had occurred at the time of their marriage in terms of their status within their community, standard of living, and autonomy in household decision-making.

Data Analysis

We used a framework analysis approach to analyse FGD data, allowing themes to emerge from our three main questions and participants’ narratives.Citation36,Citation37 The authors familiarised themselves with the FGD data by reading notes taken at the discussions and the translated transcripts. Using the FGD structure (made up of three research questions) as a starting point, ideas and concepts were drawn from the data to develop categories and themes; quotes were indexed and sorted manually. Where possible women’s survey data, analysed in Stata 15.0, are drawn in to address correspondence between what parents (in FGDs) and what young women say about marriage (surveys).

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the University of California, Santa Barbara (Human Subjects Committee #1-17-0405) and NIMR (Lake Zone IRB #MR/53/100/463). Informed consent was obtained verbally from participants prior to data collection. Consent statements were read and then given to the participants along with contact information for the researchers who participants were encouraged to contact with any questions or concerns. For minors, parents/guardians provided consent for their daughters’ participation after which the minor provided her assent.

Results

Why marry?

When asked why one gets married, initial responses from FGD participants were short and expressed with self-evidence. Many suggested that marriage was the law – with references to natural law, God’s law, and Sukuma law. When asked to elaborate on why one marries in the local community, three main themes emerged.

Childbearing

FDG participants nearly universally cited childbearing as a reason for marrying: “You give birth and feel good. When you give birth and make your home with your children, it is a pleasure for the family, children and relatives” [Woman, rural]; “A man marries in order to get children. That’s when he feels happy” [Woman, rural]. Not being able to have children was seen as a major hardship experienced within marriages. If either partner were infertile, then conflict between the spouses ensues and one partner may decide to have children outside of the relationship to fulfil this need.

Though children are closely linked to happiness within marriage, having children outside of marriage is common in this area.Citation26 Among survey participants, approximately one-third of women who had ever given birth were unmarried at the time of their first birth.

Partnership

Women and men commonly cited partnership as a reason to marry – in terms of love and council, and in sharing life’s responsibilities. Through marriage each partner gains a helper; women take on responsibilities like cooking food and fetching water, while males become responsible for earning money which is used by his wife to fulfil her responsibilities. In addition to practical responsibilities shared by a couple, they also share ideas: “The man depends on a woman and a woman depends on the man. That’s why I decided to marry – so that we can exchange ideas. One person’s ideas cannot work out like two people’s ideas. That is what I understand” [Man, semi-urban]. If love and partnership break down, this can lead to infidelity or abuse.

Respect and status

Finally, marriage brings respect and status within one’s family and community. Both men’s and women’s views gain weight within their community by being married; their views will be sought in community decision-making and their contributions sought in community activities. Not being married may be detrimental for men or women:

“You will be counted on the issue of making decisions in the community [if you are a married man] and you will be respected. But if you don’t have a wife, people will disrespect you even on making decisions. Even when you have a good contribution, it will look like rubbish since you don’t have a family. You as a man cannot run your own life without a wife.” [Man, semi-urban]

“I may decide not to marry and I start my own business and make a large profit that will satisfy my life but the problem is I don’t have a man, so I won’t be respected in society. They will say ‘this lady is not married’. They will say ‘she can’t be married; maybe she has some problems’. You see, they won’t know what is inside my mind, it is difficult to know why I didn’t marry.” [Woman, semi-urban]

When to marry

The discussion of the “correct” time to marry centred not only around age, but also circumstances that make a given age the “right” or “wrong” time. Respondents were aware of circumstances which prompt a mistimed marriage for both males and females. Mistimed marriages come with consequences, but were viewed as unavoidable in certain circumstances.

The “right” time to marry

Among survey participants, the median stated ideal age at marriage was 18 years for women (IQR = 18, 20) and 22 years for men (IQR = 20, 25) (). In all FDGs parents clearly indicated that ages at and over 18 years were the “right” time to marry for both males and females, though similarly to survey participants, they noted that males should be older than females. Some justified the view that over 18 years was the right time to marry because it is the age after which males and females are physically mature and will desire the opposite sex; others referenced Tanzanian Law (note: at the time of the FGDs the legal 18-year minimum age at marriage only applied to males).

Figure 2. Ideal ages at marriage for females and males as reported by 15–35-year-old women surveyed in semi-urban and rural communities (n = 993)

Circumstances other than age, however, can indicate the “right” time to marry. For females, girls are considered ineligible for marriage so long as they are students, but when they leave school (through completion or drop-out) marriage is appropriate even if they are not yet 18 years: “If she fails her form two exams, then she can be married” [Woman, rural]. Others expressed that if a girl/woman is not in school, then she should marry to become “productive”. If she were to stay at home, unmarried, and not in school she would be unproductive.

Males also should not marry while in school, but a more commonly cited indicator of the “right” time for males to marry was financial independence. A man must be able to provide for a family and he (or his family) should be able to pay a bridewealth. These abilities are not necessarily tied to his age:

“[A man needs a] bed. A bed, maybe and other things like a bed cover, a house to live in. It is not good to marry and bring a wife to live at your home and you are still sleeping at your father’s house … You are calling yourself a man. Yes, you are a man, but it is not good to do that since it is not the right time. Although the age may be right to marry, … the time is not right.” [Man, rural]

“Too early” and “too late”

Some circumstances prompt a marriage to occur earlier or later than stated ideals. For both sexes, marrying before physical maturity is “too early”. Respondents commonly noted that a man’s body matures around 18 years: “He is capable of getting a woman pregnant. His sperm will be mature” [Man, rural]. On the other hand, respondents noted that females can be physically mature before 18 years: “At 14 a girl may look adult-like because of her body” [Man, rural]. Being physically mature may inspire a young man or woman to seek a partner sometimes earlier than is desirable:

“The body morphology may make a person marry even if they are too young to marry. When a boy or girl goes through puberty, they become attractive and that influences him or her to marry although the time may not be right.” [Man, rural]

“Even though the time is not right, since there is not a helper in the family but there are cows [for bridewealth] he should start a family so that she [his new wife] can help his mother. People may say that you married too early, but people from outside don’t know about the responsibilities at home.” [Man, rural]

“My husband will not be respected by my family like other men who have paid bridewealth to their in-laws, and this is the same to women. You will be disrespected.” [Woman, semi-urban]

“There is something called poverty and a difficult environment. As a parent, you may feel that maybe through [your] child you will be able to get relief. Therefore, you will assign her relative to find her a man to marry her.” [Man, semi-urban]

“I disagree with the issue you are calling desire of parents [for their daughters to marry]. No, you may find the child who is twelve, thirteen, fourteen up to fifteen is pregnant and as a parent you didn’t know … Nowadays children are impregnated.” [Man, semi-urban]

Marrying “too early” or “too late” comes with consequences. By remaining unmarried, young people’s authority or adulthood is undermined. A woman remaining unmarried may be called “msichana wa gunila” (worthless girl) and cannot gain respect from her community through other roles. Males who do not marry are perceived as avoiding responsibilities (“you will be considered as a person who likes pleasure” [Man, semi-urban]). On the other hand, a man who marries too early risks not being able to provide for his wife or children, thus undermining his status. Men and women who marry too early also risk having too many children (according to local ideals).

Adulthood and marriage

Marriage is integrally linked to local concepts of adulthood but adulthood is only partially linked to age. Many participants expressed that if one is an adult, then they should marry. Turning 18 years can mark the beginning of adulthood and thus the appropriate time to prepare for marriage. However, adulthood can occur before 18 years. Similarly to marriage, puberty marks the lower limit of adulthood, but if a woman under age 18 years feels that she is an adult then she can marry: “Others [females] are married at 13. Just two years ago it happened in town. A girl decided that she was an adult [so she was married]” [Woman, rural]; “If she feels that she is mature even at fourteen or fifteen, she can be married” [Woman, rural]. In such cases, these minors would use their marriage as a way of “announcing” their adulthood. In this way, adulthood can also be the consequence of marriage, rather than the cause. Men and women take on new responsibilities at marriage which transition them into adulthood: “Those responsibilities [that come with being married] make you an adult. You change from being a girl and become a woman/mother” [Woman, semi-urban]; “When you are married you will be considered as an adult so you have to participate in all community activities as an adult” [Man, rural].

Who decides when/who to marry?

The process of marriage – its timing and choosing a partner – was described as guided by the couple to be married, though parents help facilitate the process. FGD participants reported that marrying couples should decide when and who to marry, with males initiating the process: “it is the man and the woman who are responsible for their marriage” [Woman, rural]; “both the man and the woman should agree … you have to come to an agreement together” [Man, semi-urban]. Once the couple agrees to marry, then parents negotiate bridewealth. In informal marriages, the couple simply begin cohabitating. In some instances, women’s parents seek compensation from the husband, essentially a late bridewealth.

Some suggested that couple-directed (as opposed to parent-directed) marriage was a recent development. This perception was paired with the common notion that today’s youths marry earlier than they used to in the past, despite evidence to the contrary.Citation34 Reasons for this perceived change included moral degradation, harmful effects of exposure to Western cultures, a lack of fear of God, and changing norms regarding parents’ involvement in their children’s lives. The mismatch between a real rising age at first marriage and a perceived child-led decrease in age at first marriage could reflect changing norms and decreased parental involvement in choosing their children’s mates. Parents may see young people taking control of the marital process and conflate this independence with young people getting married earlier these days.

Survey data corroborate the preference for self/couple-directed marriages (): unmarried girls/women overwhelmingly expected to decide on their own or in conjunction with someone else (usually a parent) when and who to marry (86% and 97% respectively); and among all women, 80% reported that a woman should decide when to marry on her own (58%) or with someone else (23%). These preferences are reflective of ever-married women’s reports: 90% selected their first husband, while 6% picked their husband with parental help.

Discussion

Development narratives surrounding early marriage often take for granted that marriages before age 18 years lack meaningful consent and are resolutely harmful to wellbeing. Girls are routinely portrayed as forced into marriage with older men for the economic gain of parents (especially fathers) and patrilineal kin. Our findings suggest that reality is more complex; in this area of Tanzania the benefits of marriage generally may make early marriage specifically an attractive option for some young women. Two findings have particular relevance to the end “child marriage” movement: (1) women experience a high degree of autonomy over the marital process; and (2) marriage is a means of gaining respect and status within one’s community. Together these factors may help explain why early marriages are common in this community.

Female autonomy over the marital process

Campaigns to eradicate early marriage frequently emphasise that such marriages are driven by parents not young people, equating early marriage to forced marriage.Citation38,Citation39 However, we found a strong preference among both FGD and survey participants for young people selecting their own partners and deciding when to marry. These ideals and expectations are reflected in the experiences of women who had ever married. This finding corresponds to other studies from Tanzania which note autonomy among couples in guiding their marriage process,Citation40,Citation41 and more generally, autonomy in sexual and reproductive decision-making among young people.Citation41,Citation42

While some participants did suggest that poverty causes parents to push daughters to marry early, this situation was considered rare. Even without any parental interventions, however, poverty could constrain women’s choices and prompt them to marry earlier than otherwise preferable. For example, in harsh environments, collective (family) interests may take precedence over individual interest.Citation7,Citation12,Citation13 In such environments, a daughter may see marrying as a means of supporting her family (and maybe even herself).Citation15,Citation16,Citation21 In Kisesa specifically, young women experiencing poverty may see marriage as a means of generating income and pride for her parents through a bridewealth transfer.

Some would argue women under 18 years are not capable of making fully informed decisions about marriage. However, the boundary between childhood innocence and adult responsibility is flexible; in some cases, an accelerated entry to adulthood could be used to women’s advantage. A female survey participant who married before 15 years was orphaned early in life and lived with an abusive foster family. She used marriage to an older man to accelerate her entry to adulthood, thus emancipating herself from her abusive family. Such findings parallel those from the United States where for some minors staying unmarried may equate to a continued exposure to risk rather than a means of protection or preserving innocence.Citation43

Thus, rather than fixating on the arbitrary threshold of 18 years, humanitarian concern surrounding early marriage may be better refocused on circumstances more reliably predictive of infringements to female autonomy: in areas where very early marriage is common (<15 years), where parents exert full control over the marital process, or when divorce cannot be used to leave marriages. We must also be mindful that marital choices at any age are never fully informed or free from constraints. Choices are always constrained by locally available optionsCitation16 and individual characteristics (e.g. race, class, gender).Citation14 To conflate marriages before 18 years with forced marriage, is to ignore local options, voices, life courses, and complexities.

Marriage as a strategy to gain respect and status in community

Why is marrying, sometimes early, an attractive path for women? Gaining status and respect from the community is one strong explanation. Within Kisesa, being a student is a respected role for unmarried girls/young women.Citation33 Following education, however, marriage remains an essential pathway for women to gain status and respect. Marriage also facilitates entry to adulthood. As elsewhere in Tanzania,Citation10,Citation12 the boundary between childhood and adulthood is not tied strictly to 18 years in Kisesa, varying with physical maturity and student status. In the absence of alternative respected roles for women and girls not in school, marrying remains the primary option for some women to become an adult, gain respect, and integrate into the Kisesa community even before 18 years without obvious costs to her wellbeing (see Schaffnit et al.Citation35 for an analysis of relationships between marital timing and women’s wellbeing).

This finding contrasts with common assumptions that early marriage curtails women’s opportunities to participate in the local economy and community.Citation6,Citation44 A young woman quoted previously highlighted that marriage may in fact permit her to fully participate in her community economically; remaining unmarried would cause community members to question her abilities, and exclude her from participating in activities outside the home. In other areas in Tanzania, where women’s work outside the home is less common than in Kisesa, marriage also provides women economic independence, albeit via a husband’s financial support.Citation12,Citation14

Community respect is unlike the other cited reasons to marry: children and partnership. The latter are not guaranteed with marriage. In contrast, respect and status following a marriage is reliable. Even if her relationship is “bad” a married woman will have respect from her family and community: “It is a respect. Even if she is beaten and mistreated, so long as she is married it’s okay” [Woman, rural]. As such, it is unsurprising that in the absence of viable alternative pathways to respect and status, marriage is an attractive decision for young women, and in more extreme cases a means of leveraging themselves from harmful situations (as previously shown).Citation10,Citation45,Citation46

Limitations

The number of FGDs was limited due to budgetary constraints, yet the themes/topics arising within each discussion (among males/females in rural/semi-urban communities) were remarkably similar. Quantitative surveys addressed similar themes as FGDs, and often corroborated findings. We are thus confident that our study is broadly representative of attitudes within these communities. Participants may have been untruthful in responses regarding preferences for and actual ages at marriage. However, laws on marriage ages were not widely known, enforcement was not mentioned during fieldwork, and we emphasised to each participant that responses were confidential.

Conclusion

To improve young women’s lives it is essential to consider the motivations to marry early despite purported harmful consequences. In Kisesa, where many women report high autonomy over the marital process, marriage is a means of becoming an adult after schooling, gaining status within the community, and bringing financial help and pride to one’s family. So long as viable alternatives for achieving these ends are lacking, early marriage will be an attractive path for some women when “childhood” roles expire and/or offer less desirable circumstances than marriage. It is essential to engage with the reality that marrying early is attractive to young people in some contexts, while in other contexts marriage may indeed infringe upon women’s autonomy regardless of their age. A myopic focus on an arbitrary 18-year threshold dividing ostensibly harmful from not harmful marriages, and childhood innocence from adult responsibility may lead to missed opportunities to support girls and women regardless of their marital status. We thus advocate for more nuance, and culturally-sensitive perspectives in future policy and academic discourse on early marriage.

Acknowledgements

We thank the directors of the National Institute of Medical Research, Anushé Hassan, and our fieldwork team: Maureen Malyawere, Joyce Mbata, Paskazia Muyanja, Rebecca Dotto, Holo Dick, Concillia John, Issac Sengerema, Sunday Kituku, Christopher Joseph, Naha Lelesio, Nikodem Kawedi, Minija Rose, Dotto Elilana, and Rebecca Dotto. We also thank Sophie Hedges, Jim Todd and Rebecca Sear.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Susan B. Schaffnit http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7886-7614

David W. Lawson http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1550-2615

Additional information

Funding

References

- Hodgkinson K. Understanding and addressing child marriage. 2016:1–76.

- Girls Not Brides. About Girls Not Brides. Girls Not Brides. 2017. [cited 2017 Dec 5]. Available from: https://www.girlsnotbrides.org/about-girls-not-brides/#mission-statement.

- UN General Assembly. Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. A/RES/70/1; 2015.

- Nour NM. Health consequences of child marriage in Africa. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1644–1649. doi: 10.3201/eid1211.060510

- Raj A. When the mother is a child: the impact of child marriage on the health and human rights of girls. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95:931–935. doi: 10.1136/adc.2009.178707

- Marphatia AA, Ambale GS, Reid AM. Women’s marriage age matters for public health: a review of the broader health and social implications in South Asia. Front Public Heal. 2017;5:1–23.

- Hart J. Saving children: what role for anthropology? Anthropol Today. 2006;22:5–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8322.2006.00410.x

- Lancy DF. Why Anthropology of childhood? A short history of an emerging discipline. Anthropo Child. 2012;1:1–17.

- Rosen DM. Child soldiers, international humanitarian law, and the globalization of childhood. Am Anthropol. 2007;109:296–306. doi: 10.1525/aa.2007.109.2.296

- Mtengeti KS, Jackson E, Masabo J, et al. Report on child marriage survey conducted in Dar es Salaam, Coastal, Mwanza and Mara Regions; 2008.

- Dixon-Mueller R. How young is “too young”? Comparative perspectives on adolescent sexual, marital, and reproductive transitions. Stud Fam Plann. 2008;39:247–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2008.00173.x

- Stark L. Early marriage and cultural constructions of adulthood in two slums in Dar es Salaam. Cult Health Sex. 2017: 1–14. doi:10.1080/13691058.2017.1390162.

- Archambault CS. Ethnographic empathy and the social context of rights: “rescuing” Maasai girls from early marriage. Am Anthropol. 2011;113:632–643. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-1433.2011.01375.x

- Stark L. Poverty, consent, and choice in early marriage: ethnographic perspectives from urban Tanzania. Marriage Fam Rev. 2018;4929:1–17.

- Montazeri S, Gharacheh M, Mohammadi N, et al. Determinants of early marriage from married girls’ perspectives in Iranian setting: a qualitative study. J Environ Public Health. 2016;2016:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2016/8615929

- Boyden J, Pankhurst A, Tafere Y. Child protection and harmful traditional practices: female early marriage and genital modification in Ethiopia. Dev Pract 2012;22:510–522. doi: 10.1080/09614524.2012.672957

- Pereznieto P, Tefera B. Social justice for adolescent girls in Ethiopia: tackling lost potential; 2013.

- Sabbe A, Oulami H, Hamzali S, et al. Women’s perspectives on marriage and rights in Morocco: risk factors for forced and early marriage in the Marrakech region. Cult Health Sex. 2014;17:135–149. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2014.964773

- Nasrullah M, Zaka R, Zakar M, et al. Knowledge and attitude towards child marriage practice among women married as children – a qualitiative study in urban slums in Lahore, Pakistan. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1148. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1148

- Wamoyi J, Fenwick A, Urassa M, et al. ‘Women’s bodies are shops’: Beliefs about transactional ex and implications for understanding gender power and HIV prevention in Tanzania. Arch Sex Behav 2011;40:5–15. doi: 10.1007/s10508-010-9646-8

- Knox SEM. How they see it: young women’s views on early marriage in a post-conflict setting. Reprod Health Matters. 2017;25:S96–S106. doi: 10.1080/09688080.2017.1383738

- Clark S, Poulin M, Kohler H. Marital aspirations, sexual behaviors, and HIV/AIDS in rural Malawi. J Marriage Fam. 2009;71:396–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00607.x

- Urrio LI, Mtengeti K, Jackson E, et al. Peer research report on child marriage in Tarime District, Mara Region, Tanzania; 2009.

- Ministry of Health, et al. Tanzania demographic and health survey and malaria indicator survey (TDHS-MIS) 2015–16; 2016.

- Corno L, Voena A. Selling daughters: age of marriage, income shocks and the bride price tradition; 2016.

- Boerma JT, Urassa M, Nnko S, et al. Sociodemographic context of the AIDS epidemic in a rural area in Tanzania with a focus on people’s mobility and marriage. Sex Transm Infect 2002;78:i97–i105. doi: 10.1136/sti.78.suppl_1.i97

- Merry SE, Wood S. Quantification and the paradox of measurement. Curr Anthropol 2015;56:205–229. doi: 10.1086/680439

- Makoye K. Tanzania launches crackdown on child marriage with 30-year jail terms. Reuters World News. 2016.

- Akwei I. Tanzania’s AG appeals against court ruling raising marriage age for girls to 18 | Africanews. Africanews; 2017.

- Longman C, Bradley T. Interrogating harmful cultural practices: gender, culture, and coercion. London: Routledge; 2015.

- Kishamawe C, Isingo R, Mtenga B, et al. Health & demographic surveillance system profile: The Magu health and demographic surveillance system (Magu HDSS). Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44:1851–1861. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv188

- Garenne M. Age at marriage and modernisation in sub-Saharan Africa. South African J Demogr. 2004;9:59–79.

- Hedges S, Sear R, Todd J, et al. Trade-offs in children’s time allocation: mixed support for embodied capital models of the demographic transition in Tanzania. Curr Anthropol. 2018;59:644–654. doi: 10.1086/699880

- Marston M, Slaymaker E, Cremin I, et al. Trends in marriage and time spent single in sub-Saharan Africa: a comparative analysis of six population-based cohort studies and nine demographic and health surveys. Sex Transm Infect 2009;85:i64–i71. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.034249

- Schaffnit SB, Hassan A, Urassa M, et al. Parent-offspring conflict unlikely to drive ‘child’ marriage in northwestern Tanzania. Nat Hum Behav; in press.

- Rabiee F. Focus-group interview and data analysis. Proc Nutr Soc 2004;63:655–660. doi: 10.1079/PNS2004399

- Krueger R. Focus groups: a practical guide for applied research. London: Sage Publications; 1994.

- Girls Not Brides. Theory of change on child marriage; 2014 . Available from https://www.girlsnotbrides.org/theory-change-child-marriage-girls-brides/

- UNFPA. Child marriage. [cited 2017 Dec]. Available from http://www.unfpa.org/child-marriage.

- Kudo Y. Female migration for marriage: implications from the land reform in rural Tanzania. World Dev. 2015;65:41–61. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.05.029

- Wamoyi J, Fenwick A, Urassa M, et al. Socio-economic change and parent-child relationships: implications for parental control and HIV prevention among young people in rural north western Tanzania. Cult Heal Sex. 2011;13:615–628. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2011.562305

- Nnko S, Pool R. Sexual discourse in the context of AIDS: dominant themes on adolescent sexuality among primary school pupils in Magu district, Tanzania. Heal Transit Rev. 1997;7:85–90.

- Syrett NL. American child bride: a history of minors and marriage in the United States. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press; 2016.

- Carmichael S. Marriage and power: Age at first marriage and spousal age gap in lesser developed countries. Hist Fam 2011;16:416–436. doi: 10.1016/j.hisfam.2011.08.002

- Schlecht J, Rowley E, Babirye J. Early relationships and marriage in conflict and post-conflict settings: vulnerability of youth in Uganda. Reprod Health Matters. 2013;21:234–242. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(13)41710-X

- Wodon Q. Early childhood development in the context of the family: the case of child marriage. J Hum Dev Capab. 2016;17:590–598. doi: 10.1080/19452829.2016.1245277