Abstract

Contemporary economic coercion increasingly features the use of ‘informal’ sanctions—government-directed disruption of international commerce that is not enshrined in official laws or publicly acknowledged as coercive, yet which seeks to impose costs on key firms or industries in a target country in order to achieve strategic objectives. We investigate how ‘informality’ mediates the link between economic interdependence and coercive power, leveraging the most significant contemporary case of informal sanctions: China’s apparent retaliation against South Korea’s deployment of the terminal high-altitude area defense (THAAD) missile system between 2016 and 2017. We offer three contributions. First, we introduce a new qualitative dataset that carefully documents extensive evidence of the South Korean actors and industries that experienced disruption, the mechanisms through which disruption occurred, and its apparent impacts. Second, we use that evidence in a theory-testing exercise, evaluating the utility of hypotheses from the extant literature on formal sanctions in explaining how informal sanctions are used, and which industries they target. Finding the established wisdom offers some insight but only general expectations, our third contribution is theory development: we use the THAAD case as a heuristic to conceptualize informal economic sanctions, and specify two new variables—regulatory availability and opportunism—that mediate their use and impacts.

Introduction

In July 2016, the government of South Korea announced it would jointly deploy the terminal high-altitude area defense (THAAD) missile system with the United States. Over the next 18 months, a wide range of South Korean firms and industries doing business with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) experienced various disruptions to their commercial activities and associated financial losses. The headline-grabbing cases were the closure of some 74 Lotte supermarkets for fire safety violations, and the halt of all outbound group tourism to South Korea, resulting in an almost 50 percent fall in PRC arrivals over 12 months. Numerous media reports identified disruption to a broad range of other industries as diverse as cosmetics, electric vehicle (EV) batteries and pop music as further instances of politically motivated economic coercion. Yet total bilateral trade and South Korean exports to the PRC both grew by approximately 14 percent in 2017. Disruption, therefore, appears to have been both highly selective in its impact and relatively insignificant in the context of the overall bilateral economic relationship. What lessons does the THAAD case offer regarding the contemporary dynamics of economic coercion?

Modern scholarly research into economic coercion traces back to two foundational works that theorize the sources of power arising from economic interdependence (Keohane & Nye, Citation1977) and specify the instruments of economic statecraft that governments might rely upon in a given influence attempt (Baldwin, Citation1985). In subsequent decades, a vigorous research program emerged exploring the effectiveness of formal economic sanctions (see e.g. Blanchard & Ripsman, Citation1999; Drezner, Citation2000; Early & Cilizoglu, Citation2020; Hufbauer et al., Citation2007; Kirshner, Citation1997). Yet South Korean businesses were not the target of traditional economic sanctions. The disruption to economic relations was never acknowledged as official PRC government policy nor imposed via a formal legal framework for sanctioning. We adopt the label “informal sanctions” to describe this type of economic coercion.Footnote1

In recent years the PRC has exhibited an increasing willingness to employ such sanctions when prosecuting political disagreements. Gholz and Hughes (Citation2019) document the consequences of China’s apparent imposition of unofficial export restrictions on rare earth elements to Japan in 2010 after the Japanese government detained the captain of a Chinese fishing trawler. Chen and Garcia (Citation2016) examine how (official) Norwegian salmon exports to China decreased significantly due to “subtle” sanctions after the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to a Chinese dissident, while Fuchs and Klann (Citation2013) present statistical evidence that the Chinese government has punished states whose leaders meet with the Dalai Lama by unofficially and temporarily reducing imports. Most recently, a range of Australian exports have encountered a variety of technical and regulatory obstacles to entering the Chinese market, although the Chinese government denies such disruption has anything to do with ongoing political disputes (Ferguson & Lim, Citation2021).Footnote2

During these coercive events only a select number of firms and industries experience disruptions while others go unscathed. In other words, the macroeconomic condition of interdependence does not create uniform microeconomic vulnerability within a state’s economy. Yet although informal economic sanctions by the PRC have attracted significant attention from commentators in recent years, they have received little systematic scholarly attention that can explain this variation. The literature on economic statecraft does not consider how informality might introduce novel dynamics that shape coercion. Nor does the recent research on Chinese (and Russian) “gray zone” strategies, which cites informal sanctions as one example of emerging coercive tactics that can be difficult to attribute to specific actors and which fall below the threshold of war, but does not consider how their form and outcomes might be shaped by political economy dynamics (see, e.g. Green et al., Citation2017; Mazarr, Citation2015; Morris et al., Citation2019).

This article seeks to address these issues by advancing three research objectives. The first is empirical descriptive inference. Single case studies of prominent coercive episodes present fertile opportunities to test and refine existing theories of economic coercion (see, e.g. Gholz & Hughes, Citation2019; Vekasi, Citation2019). China’s response to South Korea’s deployment of THAAD is one of the most important contemporary case studies of economic coercion, in particular because of the breadth of industries reportedly affected, speaking to the merits of cataloguing evidence in one place. To that end, we present in an accompanying appendix a new qualitative dataset, constructed according to emerging best practices in case study research design. The dataset contains a comprehensive range of publicly available English, Korean and Chinese language media reporting from July 2016–December 2019 on the South Korean industries reportedly affected by Chinese sanctions, the specific mechanism through which disruption was said to occur, and evidence of any impacts. Our descriptions and analysis of this evidence are also informed and supplemented by in-person interviews conducted in South Korea with former and current senior government officials, researchers and others with industry knowledge.

The second objective is to answer the following research question: what explains the selectivity of the economic disruptions experienced by South Korea? We begin to answer this question with a theory-testing exercise. We outline the theoretical logic of three hypotheses regarding which industries within a target state are most vulnerable. These hypotheses are derived from the formal sanctions literature, and our contribution is to test them against the evidence of informal sanctions in the THAAD case.

We find that the evidence offers partial support for the hypotheses. However, because they only specify broad categories of vulnerable industries, the hypotheses are unable to explain why one out of a variety of seemingly equally vulnerable industries will be singled out, and why restraint is apparently exercised in other cases. We leverage these discrepancies to focus on the unique dynamics of informal sanctions and turn to our third objective, theory-building, in which we consider a related research question: through what mechanisms do informal sanctions operate and how do they mediate the link between interdependence and coercive power? We draw upon insights from the THAAD episode as a heuristic case study—that is, to identify new variables, hypotheses and causal mechanisms (George & Bennett, Citation2005, p. 75). Specifically, we define and develop a typology of informal sanctions. We then ask what the case suggests about the logic and consequences of informality, where sanctions are employed outside of a formal and explicit legal framework, and in turn how informality generally conditions the use of economic coercion.

Our central finding is that the decision to sanction informally—motivated by the need to maintain plausible deniability that sanctions are occurring—introduces novel constraints on the use of economic power that allow the specification of narrower scope conditions when identifying the industries and actors most vulnerable to coercive disruption. We argue that this occurs in two ways. First, informality limits the policy tools through which governments can intervene in markets, increasing the prominence of what we call regulatory availability in determining vulnerability. Second, informality leads to greater principal-agent issues, exacerbating the possibility that what we label opportunism by domestic actors will mediate the impacts of disruption. In theorizing these mechanisms and highlighting evidence of how they appear to have operated in the THAAD case, we extend existing theories of economic coercion and shed new insights into Chinese economic statecraft.

In the following section, we review existing scholarship connecting economic interdependence to coercive power and specify three hypotheses that capture the established views of the formal sanctions literature. The third section provides an overview of the THAAD case and introduces the empirical appendix. In section four we analyze the evidence compiled in our appendix to test the explanatory power of the formal sanctions hypotheses in explaining variation in affected South Korean industries. Our research design then pivots from theory-testing to heuristic case study-driven theory development in the fifth section, where we draw upon the case to explore the theoretical implications arising out of informality. The final section discusses the implications of our findings and looks forward.

Power, interdependence and (formal) economic sanctions

What is the nature of coercive power and vulnerability within relationships of economic interdependence? Answering this question with precision requires pinpointing the industries most exposed in a bilateral relationship—those most likely to be disrupted for coercive purposes. Here we examine the existing literature on formal economic sanctions—the most studied cases of economic coercion—for possible explanations.

Consistent with beliefs that higher levels of economic pain are the surest way to extract political concessions from a target, much of the early sanctions literature focused on how a sanctioning state could maximize costs imposed (Doxey, Citation1980, pp. 77–79; Galtung, Citation1967, pp. 384–385; Hufbauer et al., Citation2007, pp. 101–106; Knorr, Citation1977, p. 103). If it is true that “the greater the cost of sanctions to the target, the greater the likelihood they will succeed” (Drury, Citation1998, p. 508), then one would expect disruption to focus upon the largest sectors of a target’s economy. However, this is plainly not the case in most coercion episodes. Rather, sanctioners are fundamentally conscious of the costs to themselves (Farmer, Citation2000; Morgan & Schwebach, Citation1997).

Mindful of such considerations, subsequent literature emphasized the exploitation of key asymmetries in dyadic relationships. Extending the pioneering work of Albert Hirschman (Citation1945), Keohane and Nye (Citation1977) theorized that states facing relatively higher costs in securing alternatives (or foregoing transactions entirely) are the most vulnerable. The existence of asymmetries founds the logic of the first hypothesis (H1): economic coercion will be concentrated on target state industries that face the highest “exit costs” relative to the sanctioning state (Peksen & Peterson, Citation2016; Peterson, Citation2014). This means the target cannot easily substitute or forego what the sanctioner normally provides (either as a buyer or seller), while the sanctioning state enjoys feasible alternatives.

H1 Target industries or actors with asymmetrically high exit costs are more likely to face disruption (‘exit costs hypothesis’).

A second explanation comes from the microfoundations approach to economic sanctions. Kirshner (Citation1997) argued that the effectiveness of economic sanctions depends not on the overall impact on the target economy, but how differentiated groups within the target suffer, and their respective capacities to influence their government’s policy.Footnote3 If the groups most harmed have no influence over the central government, then asymmetric exit costs mean little because economic pain is unlikely to translate into political costs (Blanchard & Ripsman, Citation1999, Citation2013; Lektzian & Souva, Citation2007). Given that empirical research has consistently demonstrated it is political consequences that overwhelmingly determine outcomes in sanctions episodes, one would expect a discerning coercing state to focus on imposing high political costs on the target government (H2).Footnote4 This idea dovetails neatly with the emphasis on ‘smart’ or ‘targeted’ sanctions—that target individuals or firms with close ties to the target government’s leadership, rather than the broader economy—in both scholarly and policy communities in recent decades (see Cortright & Lopez, Citation2002; Drezner, Citation2011).

H2 Target industries or actors that wield political influence over the target government are more likely to face disruption (‘target microfoundations hypothesis’).

A third literature explores how domestic factors in the sanctioning state, rather than the target, may affect sanctioning behaviour. In particular, governments may not design sanctions regimes to maximize pain on a target, but to satisfy the interests of core domestic interest groups for political gain (Drury, Citation2001; Hedberg, Citation2018; Kaempfer & Lowenberg, Citation1988, Citation1992). These “sanctioner microfoundations” operate through two different mechanisms. The first reflects an economic logic. Sanctions introduce distortions in markets, which may increase politically popular rents for domestic producers or industries that compete with actors in the target state (McLean & Whang, Citation2014). The second mechanism is ideational. Sanctions demonstrate to domestic audiences that the sanctioning government is being “tough” on the target, thereby defending normative values such as human rights, or political values such as nationalism or specific interests in a bilateral dispute (Lindsay, Citation1986; Nossal, Citation1994). While the mechanisms operate differently, we consider them together because both ultimately reflect decision-making driven by the goal of catering to the interests of core domestic constituencies. Accordingly, the hypothesis (H3) is that sanctions will target industries in order to maximize domestic political benefits to the sanctioning government itself, as determined by how its polity will react to the decision to sanction.

H3 Target industries or actors are more likely to face disruption when doing so increases domestic political benefits to the sanctioning government (‘sanctioner microfoundations hypothesis’).

In summary, these three hypotheses specify scope conditions for those industries most likely to be disrupted by formal economic sanctions. The exit costs hypothesis (H1) rules out those industries that would either be too costly for the sanctioning state, or those the disruption of which would impose negligible costs on the target state. The target microfoundations hypothesis (H2) rules out those industries lacking political influence over the target government. Finally, the sanctioner microfoundations hypothesis (H3) rules out those industries offering little domestic political benefit to the sanctioning government.

The hypotheses are not mutually exclusive, and can be complementary in delineating overlapping scope conditions. No single theory purports to explain all variation in target selection. Moreover, each emerges from research predominantly focused on sanctions that were public (governments openly acknowledged the disruption of trade with a target economy) and employed through formal legal frameworks designed for the purpose of sanctioning. Thus, while it is plausible that these theories may offer insights into the use of informal sanctions, any shortcomings would not constitute a rebuttal of their general applicability but rather point to the possibility that informal sanctions are conditioned by novel dynamics.

China’s response to THAAD in South Korea

Overview

Our case study revolves around South Korea’s decision to jointly deploy a US-led THAAD anti-ballistic missile defense system in early July 2016, and China’s subsequent retaliation across a variety of domains ostensibly designed to pressure Seoul to reverse its decision.

Beijing had consistently expressed opposition to the deployment of any US-led regional anti-ballistic missile defense system in South Korea. One prominent motivation for this resistance appears to be a belief that THAAD’s X-band radar would extend beyond the Korean Peninsula to the Chinese mainland, potentially undermining Beijing’s nuclear deterrent.Footnote5 As discussions between Seoul and Washington intensified following North Korea’s fourth nuclear test and a long-range missile test in early 2016, China’s Ambassador to South Korea Qiu Guohong warned Sino-South Korean ties would be ‘destroyed in an instant’ if THAAD were deployed.

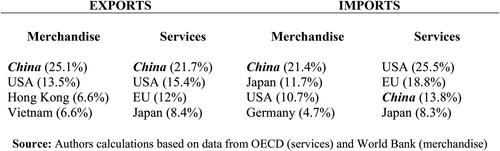

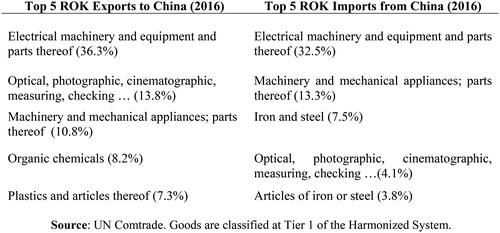

China’s retaliatory measures included various political, diplomatic and military gestures, but the most prominent instruments deployed were economic. The bilateral economic relationship offered broad coercive potential. China was (and remains) South Korea’s largest trading partner, accounting for more than 25 and 21 percent of total merchandise and service exports respectively in 2016 (). As can be seen in , the bulk of merchandise exports are processing trade in intermediate inputs. As exports contributed approximately 40 percent to South Korea’s GDP at the time,Footnote6 any disruption of Chinese trade could threaten the overall economy. Seoul also appeared particularly vulnerable because its trade dependence was relatively asymmetric—China, by contrast, only received 10 percent of its merchandise imports from South Korea, and did not rely on South Korea as a key supplier of any key services trade.

The range of South Korean products, industries and firms that reportedly experienced disruption during the dispute was extraordinarily diverse. Among others, it was reported to include electronic bidets held up in customs, the cancellation of planned Chinese performances by South Korean sopranos and boy bands, and the denial of government subsidies to electric vehicles utilizing South Korean batteries. These examples also speak to the fact that China’s apparent sanctions came in various shapes and sizes.

Although diplomatic relations experienced some recovery in late 2017, key South Korean industries and firms operating on the mainland continued to report forms of disruption well into 2018 (see Financial Times, Citation2018; Yonhap, Citation2018). Yet, despite this, total bilateral trade increased by 13.6 percent in 2017 and South Korean exports to China grew by 14.1 percent (Jung, Citation2019). Disruption, therefore, appears to have been puzzlingly selective: which economic actors and industries were affected, and why them and not others?

The appendix

As one South Korean official observed in an interview, every trading relationship experiences daily frictions—miscommunications and misunderstandings, improper paperwork or simply poor-quality products—which are entirely normal and not related to the broader political relationship. Informal economic sanctions are by definition unannounced, meaning that identifying any given case requires presenting facts that, together, at best are only suggestive of politics being somehow involved.

Accompanying this article is a supplemental appendix that presents empirical descriptions of the disruptions that we posit are most likely to represent informal economic sanctions targeting South Korea during the period when THAAD was the major source of bilateral tensions. It contains five categories of affected actors and industries: (i) the conglomerate Lotte; (ii) tourism; (iii) EV batteries; (iv) motor vehicles; and (v) cultural exports. A sixth category provides shorter analyses of several other affected industries for which there was considerably less evidence, including cosmetics and food products, and the most notable unaffected industries, such as semiconductors.

Drawing on a broad range of media reports and other publications, the appendix distinguishes three types of “observations” for each South Korean industry or actor reportedly affected by disruption. The first describes the mechanism through which disruption occurred (which we group into three categories of informal sanctions, described in greater detail below). The second details the economic impact of disruption. The third documents additional evidence that sheds further light on the experience of industries or offers extra leverage for evaluating the hypotheses.

Following the observations, we draw links between the evidence and the analytic conclusions that underpin our arguments in the main paper, consistent with emerging best practices in data access and research transparency (Elman & Kapiszewski, Citation2014). We outline analytic inferences regarding the three hypotheses outlined above. In the spirit of active citation (Moravcsik, Citation2010) and in order to ensure transparency and access for text-based sources, the appendix provides extensive references to more than 250 sources that have all been backed-up to an online archive. All of the factual claims that underpin our analysis are fully laid out and referenced in the appendix, which the remainder of the article actively cross-references.

Documenting what is arguably the widest-ranging contemporary case, not just of informal economic sanctions, but of Chinese economic coercion, is one of the major research objectives of this article. Informed by the evidence contained in the appendix, we now turn to evaluating the explanatory power of the three hypotheses drawn from the literature on formal sanctions to explain this case.

Explaining industry variation in China’s response to THAAD

Hypothesis one: exit costs

Hypothesis One suggests that interference will be concentrated on South Korean actors and industries likely to face higher exit costs from the disruption of economic exchange relative to their Chinese counterparts. In particular, the exit costs hypothesis suggests that South Korean exports that can be easily foregone or substituted by Chinese importers will be particularly vulnerable.

The available evidence does not reject this expectation. In particular, each of the most prominent industries and firms affected by disruption were those producing goods or services that could generally be foregone or substituted at relatively low costs by the Chinese side. For the conglomerate Lotte, singled out for reasons discussed below, the primary disruption was to its mainland supermarket business. During the dispute, Lotte Mart was challenged by popular boycotts, fines, property seizures and, most prominently, the forced closure of 74 of 112 stores for alleged violations of Chinese health and safety regulations (Appendix 2(1); 2(2)). In total, disruption led to 87 of the 112 stores being closed for significant periods of time during the dispute. The closure of Lotte Marts, however, imposed few costs on Chinese consumers who could switch to buying their groceries at a broad range of alternatives (Appendix 2(4A)).

Likewise, alternative domestic and international travel destinations mitigated the impact of the shutdown of group tourism to South Korea. In March 2017, Chinese travel agencies were instructed to cease sales of South Korea-bound travel services (Appendix 3(1B); see also Lim et al., 2020). Due to the large percentage of Chinese travellers that rely on travel agencies to arrange their bookings, the ban had a significant impact: 2017 arrivals decreased by 48.3 percent compared to 2016 (Appendix 3(2)). The decrease in travel to South Korea coincided with strong growth in Chinese arrivals to other countries in the region—such as Japan, Vietnam and the Philippines—and an increase in domestic tourism (Appendix 3(4A)). While some Chinese travellers may have been disappointed by the lost opportunity to visit Seoul or Jeju Island, the availability of many substitutes likely dampened any political frustration about government interference in the market. Meanwhile the lack of restrictions on independent travel to South Korea (Appendix 3(3B)) meant that those Chinese whose demand was relatively inelastic and for whom non-travel would be particularly costly—perhaps due to family or business interests—could still travel.

Similar stories of substitutability are also apparent for other affected South Korean consumer goods such as motor vehicles (Appendix 5(2A)), cosmetics (Appendix 7(A)) and cultural goods such as music, television dramas and video games (Appendix 6(4)). Competitive substitutes for all of these products were readily available from domestic or foreign producers in the Chinese market. This was also true for South Korean EV batteries. Prior to the THAAD dispute, South Korean battery manufacturers LG Chem and Samsung SDI set up manufacturing facilities on the mainland with the expectation that they could benefit from a Chinese subsidy scheme that covered 40–60 percent of the cost of electric vehicle purchases. However, over the duration of the THAAD dispute, not a single vehicle utilizing South Korean batteries was approved to receive the subsidy (Appendix 4(1A)). This disrupted LG and Samsung’s production (Appendix 4(2)), but the depth of competition in the Chinese battery market meant that electric vehicle manufacturers could readily shift to domestic suppliers like CATL or BYD (Appendix 4(4A)).

The flipside of H1 is an expectation that, as the costs of disrupting a given industry rise for the coercing state, the likelihood that the industry will be affected diminishes. For South Korea, this suggests that manufacturers of the intermediate inputs that make up the bulk of China-bound exports—such as semiconductors, electrical machinery, other components and organic chemicals—should have been relatively immune. The evidence suggests this was also broadly true.

While a variety of other Lotte businesses with exposure in China experienced costly disruption, Lotte Chemical, which produces and sells petrochemical products on the mainland, saw year-over-year profits increase in 2017 (Appendix 2(3C)). As one senior executive at Lotte commented: “Chemicals is a huge contributor at a time when department stores, duty free and marts have struggled due to retaliations”. 2017 was also a profitable year for South Korean semiconductor manufacturers such as SK Hynix and Samsung Electronics, who both saw overall China exports increase (Appendix 7(F)). Oil companies, such as GS-Caltex and S-Oil, are among the largest South Korean businesses operating in China (and thus exposed to potential interference), yet even at the peak of THAAD tensions during Q1 of 2017 they reported no irregular disruption and year-over-year growth (Appendix 7(G)).

Hypothesis two: target microfoundations

Hypothesis Two expects that economic disruption will be concentrated on actors or industries that have the greatest potential to influence the target state’s central government. In this case, there is no evidence that specific individuals within the South Korean government were targeted. Nor does any evidence immediately suggest that any South Korean targets were specifically chosen because of their influence over government policy. Indeed, the largest and most influential business lobbies—the Federation of Korean Industries (FKI), Korean Chamber of Commerce and Industry (KCCI), and Korea International Trade Association (KITA)—are not specifically affiliated with any particular South Korean firms or industries.

Five names that feature prominently in the appendix are Lotte, LG, Hyundai, Samsung and SK Group. They constitute South Korea’s leading chaebol: large and typically family-controlled conglomerates known to have significant political influence due to their “cozy relationship” with government (Albert, Citation2018). Chaebols have historically channeled their influence bilaterally through direct communication with government officials, and jointly through the FKI, in which they have all played leading roles.Footnote7 Each of the conglomerates experienced various forms of disruption during the THAAD dispute—most prominently, Lotte’s mainland subsidiaries experienced regulatory interference (Appendix 2(1A)) and boycotts (Appendix 2(1C)) and its hotel and duty free businesses were affected by Chinese travel restrictions (Appendix 2(1B)(a)); Hyundai motor vehicles were boycotted (Appendix 5); and LG, Samsung and SK Group were affected by the apparent denial of subsidies to South Korean battery makers (Appendix 4). Given their potential to influence the central government, targeting the chaebols would appear to reflect H2 logic. However, the evidence that such logic motivated the disruption they experienced is thin.

Evaluating the explanatory power of H2 is complicated by a unique characteristic of South Korea’s political economy—chaebols dominate the production of most leading exports, from integrated circuits, steel and industrial machinery, to cars, petroleum, and auto parts. This makes it virtually impossible to disrupt South Korea-China economic exchange without, in some way, affecting the business activities of the large conglomerates. It was inevitable that they would be affected.

The target microfoundations hypothesis assumes that these companies are more likely to be targeted because of their potential to influence the central government (Kirshner, Citation1997). However, our analysis did not reveal any compelling evidence to suggest that this was ever the primary rationale. Rather, in each case, alternative explanations appear more plausible.

For example, the primary reason Lotte appears to have been targeted is because it provided land to the South Korean government for use in the deployment of the THAAD system (Appendix 2(1C)(b)). Whereas some South Korean economic interests had reported disruption as early as August 2016 (see Appendix 6(1B)(a)), Lotte experienced no problems until after it had inked the preliminary land transfer agreement with the South Korean government in late November 2016, subsequently approved by the company’s board of directors in February 2017.

Samsung (SDI), LG (Chem) and SK Group were all affected by the failure of EVs with South Korean batteries to receive approval for generous Chinese subsidies. Yet if, per H2, these chaebol were targeted because of their ability to influence the South Korean government, this was a very indirect method—battery production reflects only a narrow slice of their operations, while their most significant China exports were left undisturbed. For example, Samsung’s semiconductor sales have accounted for as much as 75 percent of its earnings in China in recent years, yet these did not face disruption, likely because of the high costs to the Chinese side (Appendix 4(4B)).

The scattershot nature of much of the disruption is inconsistent with H2’s expectation of precise targeting of actors or industries with maximum political influence. The Chinese government encouraged, or at the least tolerated, a general consumer boycott of South Korean products. Surveys by South Korean industry associations consistently revealed that a very broad range of companies—from chaebols to SMEs—experienced different forms of disruption (see, e.g. Choi, Citation2017; Kim, Citation2018; Yonhap, Citation2017). While H2 might anticipate the targeting of Lotte, it does little to explain apparently arbitrary administrative interference such as fining South Korean restaurant owners for displaying menus in Hangul.Footnote8

Finally, while H2 draws attention to large conglomerates like Lotte or Samsung, it provides no insight into which of their trade would be most vulnerable to disruption. In the case of economies dominated by a small number of highly influential firms operating a broad range of businesses, H2 offers limited explanatory power.

Hypothesis three: sanctioner microfoundations

Hypothesis Three expects the targets of disruption to be a function of domestic calculations by the sanctioning government following economic or ideational logics. It suggests China’s informal sanctions would be grounded in either an industrial policy motive, to protect or otherwise generate rents for Chinese industries that compete with South Korean firms, or an ideational motive, such as stirring nationalism by demonstrating the government’s resolve to respond firmly to a provocation.

There are reasons to suspect an industrial policy motive existed. China and South Korea are close competitors in many major export industries. In the years leading up to the dispute China became increasingly competitive in industries traditionally dominated by South Korea—including steel, shipbuilding, automobiles and consumer electronics—such that their export similarity index score rose to 0.391 in 2016.Footnote9 South Korea continued to maintain an edge in advanced electronics, including high quality semiconductors, EV batteries and OLED displays, however even these industries are considered under threat as Beijing has increased spending and introduced various new policy initiatives designed to help the PRC move up the value chain (see Harris, Citation2018). H3 would expect these latter industries to be those most likely affected by an industrial policy motive.

While it is indirect and circumstantial, there is some evidence consistent with H3 in one of these three industries—EV batteries. As foreshadowed earlier, throughout the THAAD dispute, EV designs utilizing batteries manufactured by Samsung SDI and LG Chem were consistently denied approval for Chinese government subsidies considered a prerequisite for success in the mainland market (Appendix 4). While on its face a subsidy denial might seem far less punitive than other THAAD-related economic disruptions, Samsung SDI and LG Chem had constructed factories in mainland China fully expecting to receive the subsidy and with the knowledge that subsidized local production was the only viable pathway to competing in the market. The denials caused the firms’ customers—various Chinese EV manufacturers—to cancel their battery orders and shift to Chinese suppliers, who were able to expand their market share as a result (Appendix 4(2B)).

The targeting of the EV battery industry is the most speculative of the informal sanctions reported in the THAAD case. This is principally because no electric vehicles using Korean batteries had been approved for subsidies before the THAAD announcement in July 2016. In fact, vehicles using LG and Samsung batteries had been excluded during certification rounds in January and June 2016 (Appendix 4(1A)(a)(ii)). It is possible that the subsidies were denied for technical reasons unrelated to THAAD, and it was the only industry characterized by deep competition between South Korean and Chinese companies reported to experience this kind of interference.

Nevertheless, thousands of electric vehicles using different batteries were approved over the course of the dispute. In the lead up to each round of approvals in 2016 and 2017, various industry sources went on the record to say that they expected vehicles with South Korean batteries to be approved because they satisfied all of the formal requirements (Appendix 4(1A)(a)(i)). The denials effectively put South Korean battery makers out of business during the period of the dispute, thereby giving a major boost to local producers—actions consistent with China’s goal of creating globally competitive ‘national champions’ in the EV sector (Appendix 4(3D)).

In an interview, one official with knowledge of the issue stated that the difficulties experienced by battery makers were one of the South Korean government’s top concerns (along with Lotte and tourism) arising out of THAAD tensions.Footnote10 This, and the other evidence pointing towards a connection between tensions and the denial of subsidies (see Appendix 4(1A)(a)(i)), lead us to conclude that some connection plausibly existed. Accordingly, we find that H3 receives partial support—the subsidy denial served to benefit a core sector of the domestic economy that had been prioritised for industrial policy support in the years leading up to the THAAD dispute.

The nationalist motive aspect of H3 involves generating domestic support by using sanctions for an ideational purpose. The targeting of Lotte, a well-known South Korean company with a strong public presence which was directly associated with the deployment of the THAAD system, might be considered consistent with this logic (Appendix 2(4C)). Strong public anger directed at Lotte may have increased the incentives to target the company, and leaving a state-ordered closure notice on the front door of large department stores in highly visible shopping areas was one way of demonstrating to citizens that the government was taking firm action. Shutting down outbound group tourism might be considered to have served a similar function as it affected millions of Chinese citizens (Appendix 3(4C)). Finally, targeting cultural exports, another product with high public visibility that is easily identified as South Korean, can also be said to be consistent with the logic of H3 for the purpose of signaling a strong government response to citizens (Appendix 6(4C)).

Discussion

In late 2017, the disruption reported by South Korean firms gradually began to ease. This came after the apparent political resolution of the THAAD dispute. Following the South Korean government’s announcement that they would not deploy additional THAAD batteries, not participate in any US regional missile defense system, and not enter a trilateral alliance with the US and Japan (the ‘three noes’), Seoul and Beijing agreed to restore relations to the “normal development track” on 31 October. Presidents Moon Jae-in and Xi Jinping subsequently confirmed the restoration of ties when they met at an APEC summit on 11 November. The question of whether the three noes constitute a meaningful concession from South Korea or a ‘successful’ use of economic coercion by China is beyond the scope of this paper.Footnote11 Our focus is explaining variation in the industries targeted by informal sanctions, and how well it can be explained by existing theories of formal economic sanctions.

The episode offers at least partial but varying support for all three hypotheses, suggesting that the logic of informal sanctions is similar. This is most true for Hypothesis 1, as in each case the South Korean industries targeted by Chinese coercion were ones in which the exit costs for economic interests on the Chinese side were low. Even when other motivations may have suggested the imposition of punishment, such as with Lotte Chemical, it seems that the potential costs for Chinese economic actors insulated such transactions from being affected. It is unsurprising, therefore, that the Hyundai Research Institute’s efforts to quantify the impact of THAAD-associated disruption found the costs were overwhelmingly borne by Korea: with a loss of US $7.5 billion (0.5% GDP) compared to just US $880 million (0.01% GDP) for China (Perlez et al., Citation2017).

By contrast, Hypothesis 2 received more limited support. However, this is predominantly because of the fact that the chaebol conglomerates dominate the Korean economy in such a way that, in the absence of more specific evidence, it is impossible to say whether they were affected by coincidence or design. Given what we know about this case, the former seems more likely.

Hypothesis 3 is perhaps the most interesting of the established wisdom. The research program focusing on domestic interests inside the sanctioning state has largely focused its empirical attention on the United States and characterized impacts whereby domestic industries receive protection or benefit through the imposition of sanctions as “positive externalities” (see Drury, Citation2001), rather than as strategic moves primarily directed towards the attainment of discrete economic objectives. In economies where the state plays a more prominent and activist role in the market, one can easily imagine that elements of a sanctions program, formal or informal, might be more explicitly directed towards industrial policy objectives—such as bolstering domestic EV battery manufacturers, which some evidence suggests may have happened in this case.Footnote12 The targeting of highly visible South Korean firms and industries is also broadly consistent with the ideational mechanism of appeasing core domestic constituencies by demonstrating government resolve.

Stepping back, the most notable shortcoming of the established hypotheses is that they offer only very general expectations about potential targets of informal economic coercion. If exit costs are an important determinant, what determines which of a variety of easily substitutable products or services will be targeted? Why, for example, was group tour travel restricted while independent travel was permitted? Moreover, if there are clear domestic political logics for disrupting the commerce of a variety of target firms or industries, why choose one over another? Why exercise restraint? In the next section we zoom in on the specific actors and industries affected and consider what the disruptions might reveal about the logic and consequences of informality, with a view to developing frameworks for understanding the mechanisms through which informal sanctions are operationalized.

Theorizing informal sanctions

In this final section we look to extend the sanctions research program by utilizing the THAAD case heuristically to theorize informal sanctions. We begin by defining informal sanctions and explaining their logic, and nominate two additional variables stemming from the unique constraints of informality witnessed in the THAAD case. We explain how these variables offer new insights into the relative vulnerability of industries and actors to disruption via informal sanctions.

Conceptualizing informal sanctions

Consistent with the THAAD case, we define informal economic sanctions as the deliberate, government-directed disruption of market transactions involving economic actors from a target state to further a political or strategic objective, through means that are not enshrined in official legal frameworks for sanctioning or publicly acknowledged as coercive sanctions. These are the prominent characteristics of each of the apparent sanctions we document in the appendix, and also in earlier cases where China has allegedly used economic coercion in the past decade (see, e.g. Chen & Garcia, Citation2016, pp. 32–35).

While the potential range of market disruptions is limited only by one’s imagination, this section groups three broad types of behavior that were witnessed during the THAAD dispute, each of which can be considered a ‘type’ of informal sanction.

Strategically motivated application of existing laws that regulate commerce (“strategic regulation”): Strategic regulation involves the targeted application of an existing law in order to limit commercial activity by, and consequently impose costs on, economic actors connected to target state interests. Such cost-imposing actions are implemented by government officials. Examples can include the use of health and safety standards, licensing requirements, sanitary and phytosanitary regulations, or packaging and labelling rules (see Ferguson, Citation2021). Importantly, government officials do not appear to enforce the law with complete impartiality, in the sense of fairly and consistently applying clear standards to achieve the regulatory objective defined in the relevant legal instrument. This means that action might be taken to stop commercial operations where no violation can reasonably be said to have occurred, or where the actor might technically be in violation, but enforcement is discriminatory or capricious in nature.

The most plausible cases of strategic regulation in the THAAD episode are manifest in the disruptions faced by Lotte businesses in the Chinese market. As our appendix documents, in addition to the forced closure of Lotte Marts, regulatory rules relating to issues from fire safety to advertising were allegedly deployed to close Lotte factories and suspend Lotte construction projects (Appendix 2(1A)(a)), issue fines (Appendix 2(1A)(b)), expropriate property from Lotte businesses (Appendix 2(1A)(c)), and possibly block the ordinary passage of Lotte products through Chinese customs (Appendix 2(1A)(e)). The store closures stand out—the closure of a store for “lack of proper fire alarm system functions, lack of proper sprinkler functions, partial damage to fire exits, and lack of a safety exit in the firefighting pump room” exemplifying the types of issues typically cited (Appendix 2(1A)(a)). Lotte reported significant difficulty in resolving the alleged regulatory problems with authorities when they arose (Appendix 2(3B)). While Chinese government representatives denied there were any irregularities in the application of the law (Appendix 2(3A)(b)), the evidentiary patterns that emerge present a plausible case that Lotte was singled out for punishment. Other examples of strategic regulation may include the denial of subsidies to South Korean battery producers, Chinese authorities banning South Korea-bound charter flights (Appendix 3(1A)(b)), the refusal to issue licenses to South Korean video game developers (Appendix 6(1A)), and the broad range of reports suggesting Chinese customs officers cited health and safety or other regulatory rules in order to obstruct the passage of South Korean products (Appendix 7(C)).

Government directions to commercial actors to change their market behavior (“informal blacklisting”): In this case, government actors issue informal directions to domestic commercial actors (whether government procurers, state-owned enterprises or private companies) to limit their commercial interactions with target state economic interests.Footnote13 Informal blacklisting differs from strategic regulation in that no laws are invoked, and the physical behaviors that harm target state economic interests are taken not by government regulators, but by market participants. These actions are however taken at the direction of the government, often under the threat of punishment for violation. Directions may be issued orally or in writing. A simple example would be issuing instructions to local companies to limit procurement of inputs to their own production. Informal blacklisting uses the same mechanism as orthodox economic sanctions—controlling the behavior of market actors—but does so through informal means.

The apparent instructions for travel agents to cease selling group package tours to South Korea is one example from the THAAD case. Those instructions appear to have been issued verbally by the relevant regulatory authority—the China National Tourism Association—and coupled with a threat that non-compliance would be punished through fines or license revocations (Appendix 3(1B)(a)(i)). That a widespread ban was implemented effectively overnight, with major Chinese travel agencies removing packages from their websites and cruise ships cancelling port calls, suggests top-down coordination (Appendix 3(1B)(a)(iii)). Similarly, certain South Korean cultural products seem to have been informally blacklisted. Evidence indicates that representatives from the State Administration of Radio, Film and Television verbally instructed content distributors to cease selling South Korean products and cooperating with South Korean partners (Appendix 6(1B)(b)). The Chinese government denied such bans were in place (Appendix 3(3A); 6(3C)), instead suggesting that disruption was a product of patriotic behaviour by Chinese consumers and businesses. However, again, the speed with which disruption suddenly began plausibly suggests coordination.Footnote14 The appearance of coordination, together with the broad range of sources indicating disruption (Appendix 3(1)-(2); 6(1B); 6(2)), suggests the existence of informal blacklists.

The fomentation by government actors and state-run media of consumer boycotts (“boycott fomentation”): Political tensions between countries often elicit autonomous responses from (patriotic) consumers, making the boycott fomentation mechanism—as a deliberate top-down act by governments—difficult to distinguish. Nevertheless, it is well established that consumer boycotts can impose significant costs on target country economic interests, in particular by lowering the status of buying and owning goods associated with a foreign company (Barwick et al., Citation2019). To the extent governments can manipulate boycott behaviour without introducing formal laws (such as through state media), the fomentation mechanism can be an informal coercive instrument. Evidence suggests boycotts of a variety of South Korean products and services were fomented during the THAAD dispute, including Lotte goods (Appendix 2(1C)(a)), tourism (Appendix 3(1C)), motor vehicles (Appendix 5(1A)), and cultural exports (Appendix 6(1C)). As a representative example, an op-ed in the state-run Global Times wrote in March 2017 that “Chinese consumers should become the main force in teaching Seoul a lesson, punishing the nation through the power of the market” and proposed that “ordinary people should play the major role in sanctioning South Korea” (Appendix 3(1C)(a)).

The logic and consequences of informality

We conjecture that there are at least four reasons why a sanctioner might opt to coerce informally. Each flows from the fact that informality provides the sanctioning government with plausible deniability that strategically motivated economic disruptions are even occurring. First, utilizing informal sanctions minimizes the risk of legal challenge and potential countermeasures under World Trade Organization or other international trade and investment rules that require clear evidence of state responsibility.Footnote15 Second, being able to plausibly deny deliberate government-led disruptions may help reduce diplomatic fallout, both with the target government, and other international observers. Third, where coercion does not appear to be succeeding, the sanctioning government has greater flexibility to wind back disruption without having to acknowledge failure and endure any associated political costs (see Chen & Garcia, Citation2016; Reilly, Citation2012). Finally, as the gray zone literature emphasizes, difficulty attributing coercive actions may complicate and delay the ability of targets to respond effectively (Green et al., Citation2017, pp. 31–33; Morris et al., Citation2019, pp. 9–10).

The use of informal sanctions, and the associated maintenance of plausible deniability, introduce new dynamics that are not captured by existing theories. Focusing on how those dynamics played out in the THAAD case, we theorize two mechanisms that shape the form and outcomes of informal economic coercion: regulatory availability and opportunism.

Regulatory availability: In principle, in order for deniability to be maintained, there must be a plausible case that any disruption to or restriction on economic activity is either (i) unrelated to the political dispute at issue; or, (ii) beyond the control of the government. The former requires an alternative and ostensibly legitimate reason to restrict commerce (such as Lotte’s alleged violation of health and safety rules, see Appendix 2(3A)(b)), while the latter necessitates that the government has scope to explain disruption by reference to the autonomous actions of market actors, despite having influenced their behaviour (as was the case with the group travel ban, see Appendix 3(3A)).

In most cases, the maintenance of either of these claims will rely on what we label regulatory availability—the existence of regulatory tools, such as laws or other policy frameworks, which can be discretionally wielded by a national government to directly or indirectly manipulate commerce within and across its borders without explicitly violating international legal rules which prohibit discriminatory restrictions on economic exchange. Often this will be direct and straightforward. Examples from the THAAD case may include many of the examples we describe as ‘strategic regulation’—officials denying vehicles that used South Korean EV batteries approval for subsidies, or the non-approval of South Korean content license applications (Appendix 6(4D)(a)). Other examples include customs officials rejecting Korean goods by reference to ambiguous paperwork or other technical requirements—at times incredulously, such as the demand to resubmit export documents correcting the Romanization of a city’s name from ‘Pusan’ to ‘Busan’ (Appendix 7(C))—or indeed health and safety inspectors abruptly shutting down supermarkets.

At other times the disruption will be more indirect. In the case of outbound travel, for example, the Chinese government did not directly restrict Chinese tourists from travelling to South Korea. Instead, regulatory tools were used to influence the behaviour of core gatekeepers in the outbound travel market: international travel agencies. This was possible due to the unique regulatory structure of China’s outbound tourism market (Appendix 3(4D)(a)). Beijing was able to compel the relatively small number of state-owned travel operators who book all group travel to cease offering services to South Korea by quietly threatening to revoke their licenses, while at the same time denying the existence of any ‘bans’ and claiming that travel operators were acting independently (Appendix 3(1B)(a)).

The tourism example also illustrates how regulatory availability can help explain some of the apparent restraint witnessed in the THAAD case. Despite the almost 50 percent reduction in Chinese tourist arrivals to South Korea, it is surprising that some four million Chinese still made the trip (Appendix 3(3B)). Why did the Chinese government only restrict group tours? It is probable that the absence of an existing regulatory tool for discreetly placing restrictions on ‘free independent travellers’—such as the daily quota system for travel to Taiwan (see Lim et al., 2020, pp. 18–19)—influenced the decision to not intervene in that section of the market. Doing so would have required escalatory and disruptive measures (such as the cancellation of commercial flights) or the creation of entirely new regulatory tools (such as a requirement for exit visas)—initiatives that would plainly undermine the veneer of plausible deniability.

Opportunism: The other consequence of informality arises out of a principal-agent problem. Formal sanctions face their own enforcement challenges, as private actors seeking economic rents often engage in “sanctions busting” behavior (Early, Citation2009), including individuals or firms within the primary sanctioning state (Morgan & Bapat, Citation2003; Bapat & Kwon, Citation2015). The challenge is to compel these domestic actors—who may be apolitical and have no interest in supporting the underlying political objectives—to cease transacting with target state firms. Governments therefore attempt to signal that sanctions-busting behavior will be both detected and punished (Bapat & Kwon, 2015, p. 135), in order to compel economic actors to limit transactions with the target.Footnote16

Informal sanctions make this task harder: retaining plausible deniability requires governments to issue instructions discreetly or indirectly (what one might call ‘unofficial official instructions’). The fact that the instructions are ‘secret’ limits the availability of institutional channels through which governments can control the behavior of market actors, or indeed their own officials. It also complicates providing clarifications or other updates, or conducting formal oversight of either officials directly implementing strategic regulation (such as health and safety or customs officers) or market participants responding to blacklists (Katz, Citation2013).

This enforcement problem muddles the mechanism linking the strategic decision to impose informal sanctions by the central government to the act of disrupting a market activity. It opens the door for opportunism. Like with formal sanctions, those actors who stand to lose from the disruption are incentivized to do what they can to get around and therefore blunt the impact of the informal sanction. However, informality also creates the novel possibility of the opposite dynamic: those who stand to benefit from disrupted exchange with target industries may do the opposite, using the cover of discreet instructions and/or broader political tensions to maximize political capital or economic rents vis-à-vis competitors from the target country. They may embrace proposed disruption and potentially advocate for—or indeed carry out—more disruptive activity, exacerbating the overall impact of the informal sanctions campaign in ways central authorities may not necessarily intend. The theoretical implication of opportunism is therefore not a clear effect in one direction, but a potentially greater degree of variance because the opportunistic behavior of market actors mediates the impact intended by the sanctioning government.

The possibility of opportunist behaviour compounds the already difficult challenge of observing informal sanctions. Opportunistic motives that blunt sanctions reduce what can be observed, while opportunism that seeks to gain overlaps with the sanctioner microfoundations hypothesis, except the behaviour is sourced at the firm or individual level. These complications were apparent in the THAAD case. For example, it is puzzling that ‘banned’ South Korean duty-free stores reported a 20 percent increase in annual sales despite the enormous loss of Chinese group tour shoppers. This may be explained by the opportunistic behaviour of so-called ‘daigou’ (代购)—Chinese nationals who seek to circumvent taxes on luxury imported goods by travelling to buy and sell international products—undermining the informal ban on South Korean duty-free stores (Appendix 3(3C); 3(4D)(b)). The flipside of this can be seen in the way that Chinese carmakers appear to have leveraged the boycott of Hyundai and Kia. Given the strong competition between South Korean and Chinese automakers, it is plausible that Chinese firms embraced political tensions and the fomentation of boycotts as a unique opportunity to expand their market shares by pressuring South Korean firms to restructure their supply chains in favour of Chinese suppliers, exacerbating the breadth and depth of disruption (Appendix 5(4D)(a)).

In other examples, the suspicions expressed by interviewed South Korean officials and analysts combined with some circumstantial evidence point to the possibility that industry bodies or even enterprising bureaucrats in China may have enthusiastically embraced sanctions to achieve industrial policy goals. This may have influenced the targeting of EV batteries (Appendix 4(4D)(b)), South Korean duty-free operators (Appendix 3(3D)) or even South Korean video games (Appendix 6(4D)(b)). However, there is not enough evidence to verify or draw confident inferences. Nevertheless, the very fact of informality as a guiding principle in implementing this type of economic coercion introduces the possibility that individual actors will take matters into their own hands and look to nullify or exploit a situation in the pursuit of narrower interests.

Our argument in this section is that the THAAD case offers heuristic value to theorize two novel mechanisms that mediate the operation of informal sanctions—regulatory availability and opportunism—with two caveats. First, empirically observing these mechanisms in action poses a major research challenge, and requires humility in reading observational data. We cannot (and would not) draw pinpoint inferences or future predictions from the evidence documented in the appendix—indeed, decisive evidence of government-inspired disruptions is rare. Rather, our argument is that the case offers further evidence to justify developing a research program into informal sanctions, as both mechanisms have meaningful implications for the extent to which the Chinese (or any) government is able to direct a large-scale campaign of economic coercion or sanction specific target industries in an increasingly interdependent world. Moreover, our heuristic case study provides insights into the kinds of mediating processes that come into play with informal sanctions, and in doing so offers the basis for specifying scope conditions and making probabilistic claims about more and less vulnerable industries, narrowing (and in the case of opportunism, potentially broadening) how scholars and policymakers should think about coercive power and vulnerability in economic statecraft.

Conclusion

China’s apparent use of informal sanctions against South Korea during the THAAD dispute provides fertile ground for revisiting the dynamics of economic coercion in a contemporary context. This paper leverages the case to make three contributions. First, we present an empirical appendix documenting extensive evidence of the South Korean industries and actors alleged to have experienced disruption during the THAAD dispute, the mechanisms through which disruption occurred, and its apparent impacts. Second, we employed that detail toward a theory-testing research objective: evaluating the utility of the established wisdom from the literature on formal sanctions in the context of informal sanctions to explain selectivity in the industries and actors targeted in episodes of economic coercion. We find that the logic of formal economic sanctions remains partially applicable, however the insights from the existing hypotheses offer only very general and incomplete expectations about vulnerability to informal sanctions.

Zooming in on the underexplored micro-level dynamics, we then make a third contribution: theory-building, employing the THAAD case study as a heuristic for increasing our understanding of the way that informality conditions the use of economic coercion. After offering a conceptual definition of informal economic sanctions, we introduced a typology that identified three prominent instruments through which they are operationalized: strategic regulation, informal blacklisting, and boycott fomentation. We specified two new variables that potentially mediate the use of informal sanctions and the mechanisms through which they operate: the availability of regulatory tools conducive to maintaining plausible deniability (regulatory availability), and the independent actions of self-interested domestic actors that undermine and/or reinforce the sanctions by taking advantage of their ‘unofficial’ status (opportunism). In doing so, we extend existing theories of economic coercion by identifying new scope conditions that appear to have plausible consequences for vulnerability to disruption. Both of these processes, we argue, satisfy the threshold that justifies further research.

Our arguments have implications for research streams beyond the literature on economic sanctions. First, for scholars of Chinese economic statecraft, we provide new analytical tools that provide a more granular account of the dynamics that shape disruption to economic exchange during political disputes between China and other actors in world politics. These tools can be easily picked up, tested, and refined in new case studies as they continue to emerge. Our arguments about the way that domestic regulatory frameworks may shape the use of informal sanctions also advance the emerging research emphasising the role of domestic political institutions in economic statecraft (Kalyanpur & Newman, Citation2019; Farrell & Newman, Citation2019). Finally, in elucidating two novel mechanisms that arise where plausible deniability is pursued, we provide insights into some of the microfoundational dynamics that may shape the form and outcomes of gray zone tactics that involve governments disguising their involvement in coercion.

Understanding the logic and consequences of informal economic sanctions as a method of ‘weaponizing’ interdependence is increasingly important. They have apparently been used with growing frequency in the years since the THAAD dispute, most recently in Chinese disputes with Canada and Australia (see McNish, Citation2019; Ferguson & Lim, Citation2021). However, scholarly understanding of the factors that influence their operation and impacts remains limited. Part of the reason for this is the research challenges involved in observing political actions that are not ‘officially’ being undertaken, and the mechanisms through which they seek to manipulate the behaviour of a broad range of actors with mixed motives in different economic sectors. The pursuit of plausible deniability, and the fact that target governments are often unwilling to put evidence on the public record due to concerns about escalating disputes with Beijing, means that drawing even humble inferences will require extensive research that carefully scrutinizes reporting and industry data before utilizing fieldwork to triangulate evidence. In presenting an extensive database of the THAAD case, conceptualizing informal economic sanctions and identifying two new variables that shape their use and impacts, this article provides a stepping stone for further research into their increasingly prominent role as instruments of economic statecraft in the twenty-first century.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (1.6 MB)Acknowledgements

The authors, who contributed equally to the article, would like to thank Evelyn Goh, Benjamin Goldsmith, Jana von Stein, the members of the ANU Geoeconomics Working Group, and three anonymous reviewers for comments on earlier drafts. The authors are also grateful to those who participated in interviews during fieldwork in South Korea.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Darren J. Lim

Darren J. Lim is a Senior Lecturer in the School of Politics and International Relations at the Australian National University. His research spans the fields of international political economy and international security, with a focus on geoeconomics.

Victor A. Ferguson

Victor A. Ferguson is a PhD Candidate in the School of Politics and International Relations at the Australian National University. His research concentrates on the intersection of international political economy, international security, and international economic law.

Notes

1 We define “informal sanctions” with greater precision below. While this paper focuses on China's alleged use of such sanctions, it is not the only country said to employ them. For Russian examples see, eg, Morris et al. (Citation2019); Doraev (Citation2015).

2 For other examples, see, eg Davis and Meunier (Citation2011); Reilly (Citation2012); Norris (Citation2016); Lai (Citation2018).

3 The so-called ‘punishment’ theory of economic sanctions—that aggregate economic harm will lead citizens to put pressure on their governments to comply with the sanctioner’s demands—has been criticized by various scholars who note that sanctions often generate ‘rally-round-the-flag’ effects where citizens blame the sanctioning country, rather than their national government, for their economic woes (see, eg, Galtung, Citation1967; Pape, Citation1997; Weiss, Citation1999).

4 For a discussion of the domestic and international conditions that are most salient in determining the political cost of economic sanctions see Blanchard and Ripsman (Citation1999, Citation2013).

5 On possible explanations for China’s opposition to THAAD deployment see Watts (Citation2018).

6 Authors’ calculations from World Bank data.

7 It is notable that the FKI’s influence diminished during the THAAD dispute. The lobby was embroiled in the corruption scandal that brought down Park Geun-hye’s presidency in late 2016, causing conglomerates such as Samsung and LG to withdraw their membership. See Yamada (Citation2017).

8 This was one of a variety of miscellaneous examples given by one interview participant. Interview with South Korean government official working on international economic relations, Sejong City, South Korea, 13 September 2018.

9 Scores closer to 1 indicate higher similarities in export structures and thus stronger competition. See Jung (Citation2019).

10 Interview with South Korean government official working on international economic relations, Sejong City, South Korea, 13 September 2018.

11 On these questions, see eg, Yang (Citation2019) and Paradise (Citation2019).

12 It has been argued that this logic drives some of Beijing’s use of anti-dumping and countervailing duties. See Moore and Wu (Citation2015).

13 On formal blacklisting see Eggenberger (Citation2018).

14 This was particularly true for the tourism ban. The appearance of coordination was noted in interviews with South Korean government officials. See Appendix 3(1B)(a)(iii).

15 A detailed discussion of the mechanisms that lead to compliance with international law is beyond the scope of this paper. Motivation could be driven by a variety of factors, such as concerns about retaliation, reputational consequences, or norm violation. See, eg, Nunez-Mietz (Citation2016, pp. 15–18).

16 For recent research exploring how these issues might affect Chinese economic statecraft through the lens of principal-agent theories, see Norris (Citation2016) and Reilly (Citation2021).

References

- Albert, E. (2018, May 4). South Korea’s chaebol challenge. Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/south-koreas-chaebol-challenge.

- Baldwin, D. A. (1979). Power analysis and world politics: New trends versus old tendencies. World Politics, 31(2), 161–194. https://doi.org/10.2307/2009941

- Baldwin, D. A. (1985). Economic statecraft. Princeton University Press.

- Bapat, N. A., & Kwon, B. R. (2015). When are sanctions effective? A bargaining and enforcement framework. International Organization, 69(1), 131–162. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818314000290

- Barwick, P. J., Li, S., Wallace, J., & Weiss, J. C. (2019, April 5). Commercial casualties: Political boycotts and international disputes. Working Paper. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3417194.

- Blanchard, J.-M F., & Ripsman, N. M. (2013). Economic statecraft and foreign policy: Sanctions, incentives and target state calculations. Routledge.

- Blanchard, J.-M., & Ripsman, N. (1999). Asking the right question: When do economic sanctions work best? Security Studies, 9(1–2), 219–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/09636419908429400

- Chen, X., & Garcia, R. J. (2016). Economic sanctions and trade diplomacy: Sanction-busting strategies, market distortion and efficacy of China’s restrictions on Norwegian salmon imports. China Information, 30(1), 29–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/0920203X15625061

- Choi, K. (2017, May 2). S. Korea mid-sized firms expect no improvements in exports. Yonhap. https://web.archive.org/web/https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20170502005200320.

- Cortright, D., & Lopez, G. (2002). Smart sanctions: Targeting economic statecraft. Rowman and Little.

- Davis, C. L., & Meunier, S. (2011). Business as usual? Economic responses to political tensions. American Journal of Political Science, 55(3), 628–646. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2010.00507.x

- Doraev, M. (2015). The “memory effect” of economic sanctions against Russia: Opposing approaches to the legality of unilateral sanctions clash again. University of Pennsylvania Journal of International Law, 37(1), 355–419.

- Doxey, M. (1980). Economic sanctions and international enforcement (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Drezner, D. W. (2000). Bargaining, enforcement, and multilateral sanctions: When is cooperation counterproductive? International Organization, 54(1), 73–102. https://doi.org/10.1162/002081800551127

- Drezner, D. W. (2011). Sanctions sometimes smart: Targeted sanctions in theory and practice. International Studies Review, 13(1), 96–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2486.2010.01001.x

- Drury, A. C. (1998). Revisiting economic sanctions reconsidered. Journal of Peace Research, 35(4), 497–509. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343398035004006

- Drury, A. C. (2001). Sanctions as coercive diplomacy: The US President’s decision to initiate economic sanctions. Political Research Quarterly, 54(3), 485–508. https://doi.org/10.2307/449267

- Early, B. R. (2009). Sleeping with your friends’ enemies: An explanation of sanctions-busting trade. International Studies Quarterly, 53(1), 49–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2478.2008.01523.x

- Early, B. R., & Cilizoglu, M. (2020). Economic sanctions in flux: Enduring challenges, new policies, and defining the future research agenda. International Studies Perspectives, 21(4), 438–440. https://doi.org/10.1093/isp/ekaa002

- Eggenberger, K. (2018). When is blacklisting effective? Stigma, sanctions and legitimacy: The reputational and financial costs of being blacklisted. Review of International Political Economy, 25(4), 483–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2018.1469529

- Elman, C., & Kapiszewski, D. (2014). Data access and research transparency in the qualitative tradition. PS: Political Science & Politics, 47(1), 43–47.

- Farmer, R. D. (2000). Costs of economic sanctions to the sender. The World Economy, 23(1), 93–117. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9701.00264

- Farrell, H., & Newman, A. (2019). Weaponized interdependence: How global economic networks shape state coercion. International Security, 44(1), 42–79. https://doi.org/10.1162/isec_a_00351

- Ferguson, V., & Lim, D. J. (2021). Economic power and vulnerability in Sino-Australian relations. In L. Jaivin, J. Golley, & S. Strange (Eds.), China story yearbook: Crisis (pp. 258–275). ANU Press. https://doi.org/10.22459/CSY.2021.09

- Ferguson, V. (2021). Economic lawfare: The strategic use of law to exercise economic power. Working Paper. Australian National University.

- Financial Times. (2018, January 25). Diplomatic breakthrough fails to lift Korean brands in China. https://web.archive.org/web/https://www.ft.com/content/513e9004-0047-11e8-9650-9c0ad2d7c5b5

- Fuchs, A., & Klann, N. (2013). Paying a visit: The dalai lama effect on international trade. Journal of International Economics, 91(1).

- Galtung, J. (1967). On the effects of international economic sanctions: With examples from the case of Rhodesia. World Politics, 19(3), 378–416. https://doi.org/10.2307/2009785

- George, A., & Bennett, A. (2005). Case studies and theory development in the social sciences. MIT Press.

- Gholz, E., & Hughes, L. (2019). Market structure and economic sanctions: The 2010 rare earth elements episode as a pathway case of market adjustment. Review of International Political Economy. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2019.1693411

- Green, M., Hicks, K., Cooper, Z., Schaus, J., & Douglas, J. (2017). Countering coercion in maritime Asia: The theory and practice of gray zone deterrence. CSIS/Rowman & Littlefield.

- Harris, B. (2018, August 19). South Korea: The fear of China’s shadow. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/c2d6dad0-a13e-11e8-85da-eeb7a9ce36e4.

- Hedberg, M. (2018). The target strikes back: Explaining countersanctions and Russia’s strategy of differentiated retaliation. Post-Soviet Affairs, 34(1), 35–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/1060586X.2018.1419623

- Hirschman, A. (1945). National power and the structure of foreign trade. University of California Press.

- Hufbauer, G. C., Schott J. J., Elliot K. A., & Oegg, B. (2007). Economic sanctions reconsidered, 3rd ed. Peterson Institute for International Economics.

- Jung, S.-Y. (2019, May 13). South Korea and China in direct competition in 37% of their export items: KIET. BusinessKorea. https://web.archive.org/web/http://www.businesskorea.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=31742.

- Kaempfer, W., & Lowenberg, A. (1988). The theory of international economic sanctions: A public choice approach. The American Economic Review, 78(4), 786–793.

- Kaempfer, W., & Lowenberg, A. (1992). International economic sanctions: A public choice perspective. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Kalyanpur, N., & Newman, A. L. (2019). Mobilizing market power: Jurisdictional expansion as economic statecraft. International Organization, 73(1).

- Katz, R. (2013). Mutually assured production: Why trade will limit conflict between China and Japan. Foreign Affairs, 92(4), 18–24.

- Keohane, R., & Nye, J. (1977). Power and interdependence: World politics in transition. Little, Brown & Co.

- Kim, J.-H. (2018, March 19). KITA bemoans unfair market access in China. Korea JoongAng Daily. https://web.archive.org/web/https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/news/article/article.aspx?aid=3045845

- Kirshner, J. (1997). The microfoundations of economic sanctions. Security Studies, 6(3), 32–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/09636419708429314

- Knorr, K. (1977). International economic leverage and its uses. In K. Knorr & F. N. Trager (Eds.), Economic issues and national security (pp. 99–126). Regents Press of Kansas.

- Lai, C. (2018). Acting one way and talking another: China's coercive economic diplomacy in East Asia and beyond. The Pacific Review, 31(2), 169–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/09512748.2017.1357652

- Lektzian, D., & Souva, M. (2007). An institutional theory of sanctions onset and success. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 51(6), 848–871. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002707306811

- Lim, D. J., Ferguson, V., & Bishop, R. (2020). Chinese outbound tourism as an instrument of economic statecraft. Journal of Contemporary China, 29(126), 916–933. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2020.1744390