Abstract

Prior consultation purports to mitigate socio-environmental conflict risks by creating deliberative and democratic spaces for local communities to influence decisions over newly proposed mining projects. Yet, many contest state and corporate claims to fair and inclusive decision-making, insisting that mines are often approved in violation of their human rights. Using a critical political economy of environmental governance approach, we analyze the multilevel governance regime which informs the practice of prior consultation within the global mining industry. We argue that this regime has become ‘captured’ by mining interests, as evidenced by the ‘market-enabling’ procedures which restrict communities’ capacity to exercise self-determination. Furthermore, we suggest that this leaves some local groups with little choice but to engage in risky protest action to express opposition. We utilize the Brazilian and Peruvian mining sectors as illustrative vignettes, for which data were collected from extensive fieldwork in both countries.

Introduction

Despite widespread recognition among states and corporations of the need to ensure that development respects human rights, communities across the global South confronting the prospect of industrial encroachment face mounting threats to life and livelihood. Over the past decade, observers have reported an alarming rise in the annual number of grassroots environmental activists who have been killed due to their efforts to mobilize communities against controversial mining projects (Global Witness, Citation2021), with Latin America exhibiting some of the of highest levels of socio-environmental conflict around mineral extraction (Le Billon & Lujala, Citation2020). While mega-mining can provide low- and middle-income countries with export earnings and taxable revenues to finance national poverty-reduction programs, for groups who risk displacement or other negative impacts, much is at stake in the early multi-stakeholder deliberations which surround these projects. Accordingly, industrial mining is frequently associated with socio-environmental conflict, as this economic activity acts as a focal point around which competing interests and livelihoods clash. Yet, while conflict can be expressed in different ways and emerge at any stage of the mining lifecycle, risks are elevated when a project is initially proposed (Franks et al., Citation2014). For activists, the project licensing phase is a critical juncture, as grassroots environmental justice movements are more likely to succeed at blocking proposed industrial facilities than overturn ones already in operation (Bullard, Citation1993). Still, if states mismanage the initial engagements between parties, conflict can be set along a pernicious path whereby the risk of violent confrontation heightens over time (Jaskoski, Citation2014).

To mitigate conflict risks, mining corporations have expressed a commitment to prior consultation, which entails a promise to democratically confer with impacted communities with a view towards peacefully soliciting their endorsement. Indeed, in many countries it is no longer strictly legal for these actors to bypass local groups before state authorities can grant permission to proceed with their investments. By contrast, operating licenses are now contingent upon participatory decision-making processes at the earliest possible encounter between firms and impacted communities. What is more, the industry not only considers this to be ethical, but also good for business, as it can imbue projects with greater social legitimacy and thereby render costly opposition less likely (ICMM, Citation2009a,Citationb). Here, the assumption is that ‘strategies of violence as a coercive measure … for addressing old grievances’ against companies and governments become more likely when communities are excluded from decisions on whether ‘development should proceed at all’ (EU-UN, Citation2012, p. 6, 13). While this is to say nothing of the violence states and corporations can employ to push ahead with projects (Dunlap, Citation2019), street protests and blockades can ‘translate’ communities’ perceptions of social and environmental risk to decision-makers (Franks et al., Citation2014). If only for instrumental purposes, prior consultation has now become institutionalized globally such that it is indicative of a rules-based and procedural order, or governance regime.

Nevertheless, it remains a highly contentious, if at times elusive, practice. Across the global South, communities have accused states and corporations of insincere engagements which amount to little more than lip service to their human rights, and have even risked deadly reprisals from security forces and criminal groups simply to remind parties of their minimum obligation to comply with the law (Cuffe, Citation2019; Lakhani & Nuño, Citation2023; Watts, Citation2018). Despite having become increasingly central to the democratic governance of the global mining industry, prior consultation continues to be a source of competing legitimacy claims, raising pressing questions about whose interests are ultimately served by the multilevel governance regime which now informs the authorization of mega-mining projects.

Using a critical political economy of environmental governance approach (Newell, Citation2008), we analyze the ‘market-enabling’ transformation that has occurred within this regime over time. Specifically, we observe that it has increasingly come to reflect and advance the pecuniary interests of corporations and national development imperatives of states. We contend that this is indicative of governance capture, as the global ‘rules of the game’ germane to the solicitation of community assent have become incrementally geared towards the social and legal engineering of resource extraction. Consequently, this has resulted in the procedural cards being stacked against non-extractive interests. We draw upon neo-Gramscian governance theory to argue that this process has been driven by the industry’s efforts to discursively and institutionally co-opt and adjust ‘regulatory’ instruments/interventions which could imbue local communities with veto powers. While we are cautious not to dismiss the role that national and/or local contextual factors play in conflict outbreaks, we suggest that this global governance regime has nevertheless exacerbated generic conflict risks. This is because, ceteris paribus, it makes it more difficult for grassroots actors to utilize the prevailing procedural landscape to exercise voice at the all-important project licensing stage, much less have their right to reject mining projects upheld by state managers. As a result, many are faced with little choice but to ‘take to the streets’—a move which, in some countries, entails serious risks.

In the next section, we examine the connection between mining, socio-environmental conflict, and community deliberation. Following that, we make a novel conceptual contribution by adopting a regime-level approach to account for the procedural interconnections and market-enabling shift in prior consultation practice within the global mining industry. The third section interprets this as a form of governance capture and explains it through a neo-Gramscian lens. The penultimate section utilizes the Brazilian and Peruvian mining sectors as illustrative vignettes to showcase how this regime’s political economy has created apt background conditions for conflict at the local level. The analysis throughout our paper draws upon empirical data collected from various research projects in both countries conducted between 2014 and 2019. This involved fieldwork methods, such as participant observation and more than 120 semi-structured Portuguese- and Spanish-language interviews with key informants operating at various scales.Footnote1 The final section reflects on what our findings indicate for the emerging effort to decarbonize the global economy.

Moving beyond analytical silos

While many newly proposed industrial projects (e.g. manufacturing) can trigger environmental justice mobilizations, mega-mining is highly exposed to socio-environmental conflict risks. This is because it dramatically transforms landscapes and ecosystems, while reconfiguring control over critical renewable resources (e.g. freshwater). What is more, with extractive frontiers increasingly pushing into more remote and ecologically-fragile areas, mega-mines have now also become more likely to encroach upon historically-marginalized and land-dependent communities. Indeed, its close association with conflict was exhibited during the global commodity super-cycle (2000–2014), during which time observers charted a sustained rise in the number of (violent) conflict incidents around both new and existing operations (Özkaynak et al., Citation2015; Temper et al., Citation2015). Yet, while adverse impacts are a perennial concern, conflict can be driven by multiple factors, including rent-seeking and earnest developmental expectations. Still, in many cases, genuine fears over social and environmental harms have underpinned outright opposition (Conde & Le Billon, Citation2017). This is most likely to emerge when new operations are being licensed, as it represents the first time when local communities must publicly and collectively contemplate the risks, but equally, when they ‘have the greatest opportunity to influence whether and how projects proceed’ (Franks et al., Citation2014, p. 7577). As such, states and corporations have increasingly structured the licensing process around deliberative activities with communities, as they are believed to create space for competing interests to be channeled towards the peaceful transformation or resolution of conflict.

However, researchers have identified several reasons for skepticism. For instance, despite being praised for its democratic decision-making potential, states have been unable or unwilling to ensure that licensing accords with international standards of free, prior, and informed consent. While historical dependencies on primary commodities can generate structural barriers to enforcement, practical challenges have also marred implementation, including, but not limited to, identifying appropriate convening agencies, and ensuring that communities are given accurate information (Schilling-Vacaflor, Citation2013; Schilling-Vacaflor & Flemmer, Citation2015). Similarly, the public forums associated with environmental licensing do not always create adequate space for opposing ‘value systems’ to be resolved (Muradian et al., Citation2003), with state agencies either lacking adequate human and financial resources to implement them properly (Mallett et al., Citation2021), or treating them as performative exercises (Jaskoski, Citation2014). Relatedly, findings stress that corporations must do a better job at convening public forums which are procedurally-fair (Moffat & Zhang, Citation2014), can build trust (Zandvliet & Anderson, Citation2017), and remedy power imbalances (Howse, Citation2022), particularly when it comes to discussions over social and environmental protection measures (Pimenta et al., Citation2021). Corporate-convened deliberations can also exclude key groups (Bowles et al., Citation2019), superficially integrate community demands into planning measures (Dauda, Citation2022), and run parallel to efforts to silence opponents through coercion (Dunlap, Citation2019).

In short, while researchers have generated many insights into the failures of deliberative interventions at the project licensing stage, they have overlooked how the multiple mechanisms of early community engagement which constitute the licensing process are embedded within a wider multilevel governance framework, and can interrelate in ways that predispose actors to situations of conflict. Indeed, there has been a paucity of prior consultation research which theorizes interrelations across scales (cf., Gustafsson & Schilling-Vacaflor, Citation2022). This is curious given that the licensing of mega-mining projects is structured by ideas, standards, rules, and practices which have been institutionalized within intergovernmental, transnational, and national spaces. Accordingly, we cast our analytical gaze towards the regime-level, first identifying the global rules-based and procedural order which informs the various practices of prior consultation.

Towards a regime-level approach

The regime concept has a diverse lineage and evolving usage in the study of global politics. Most prominently, international relations scholars defined regimes as,

sets of implicit or explicit principles, norms, rules, and decision-making procedures around which actors’ expectations converge in a given area … Principles are beliefs of fact, causation, and rectitude. Norms are standards of behavior defined in terms of rights and obligations. Rules are specific prescriptions or proscriptions for action. Decision-making procedures are prevailing practices for making and implementing collective choice (Krasner, Citation1982, p. 186).

While early mainstream debate was dominated by neorealist and neoliberal institutionalist approaches, contrary to popular depiction, regime theory was never the exclusive purview of orthodox international relations theories. Indeed, it has long been utilized by scholars with varied ontological and epistemological commitments (Kratochwil & Ruggie, Citation1986; Ruggie, Citation1975; Young, Citation1989). Importantly for our purposes, although political economists were initially skeptical (Strange, Citation1982), subsequent work has shown that, stripped of its state-centric, positivist, and functionalist connotations, the regime concept can be usefully applied to the ‘many emergent sub-structures’ of global capitalism (Gale, Citation1998), including issue-specific governance struggles (Levy & Newell, Citation2002; Newell, Citation2008). Thus, when approached from an interpretivist perspective which conceptualizes global governance beyond the narrow confines of the inter-state system, even the classical definition outlined above can be an instructive point of analytical departure.

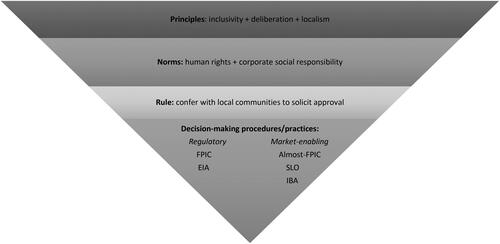

The existence of a prior consultation regime (see ) can first be inferred from the general rhetorical and behavioural isomorphism that exists among a critical mass of states, corporations, and investors on the need to directly converse with, and seek legitimation from, impacted communities before projects can be allowed to break ground. For instance, this belief has been reflected in the position statements and best-practice standards of industry associations (ICMM, Citation2013, Citation2009a,Citationb) and international organizations (OHCHR, Citation2011); the recommendations of authoritative corporate governance initiatives (UNGC, Citation2014); the loan condition policies of international financial institutions (IFC, Citation2012, Citation2006); and by national governments through international treaties (ILO, Citation1989) and declarations (UNGA, Citation2007). While expressed differently within discreet texts, all articulate a common conviction that local communities ought to be incorporated at the earliest possible stage into the decision-making processes which sanction mineral investment. Here, the principles of inclusivity, deliberation, and localism are foundational to the regime. The former two derive from dominant (liberal) democratic beliefs relating to freedom of expression, assembly, and minority rights. The lattermost originates from the ‘subsidiary principle’ of sustainable development, which is premised on the recognition that the risks of industrial activities manifest most immediately at the local level, and thus, as matters of justice and precaution, decision-making ought to occur as close to that level as possible. Applied to the issue under consideration, these principles suggest that interested parties ought to be able to peacefully debate and decide as nominal equals on the conditions under which proposed mining projects should go ahead, if at all.

Additionally, a set of interrelated global human rights and corporate social responsibility (CSR) norms have functioned to steer the behaviours of states and firms in a direction that is broadly congruent with these aims. For instance, constructivist scholarship has shown that even materially-powerful states operate within the confines of global ideational structures that inform new behaviours or prevent them from taking actions they would otherwise, as norms play both constitutive and regulatory roles (Tannenwald, Citation2007). While it is beyond the scope of this paper to catalogue all the human rights norms germane to the prior consultation regime, indigenous peoples’ right to self-determination is noteworthy. This is because mineral extraction often directly impacts upon groups for whom land is a communal asset, non-fungible, and/or the basis of collective identities, cultural practices, and livelihoods. Whether land is accessed through forced displacement or voluntary resettlement, the land grabbing associated with mega-mining can thus generate economic, social, and ontological harms (De la Cadena, Citation2015). Accordingly, indigenous peoples have been deemed worthy of special human rights protections where their lands are concerned, including the right to first define what ‘development’ means to them, and to be consulted on how their lands may be used by states and corporations, as well as openly oppose if they so choose (Anaya, Citation2013). What is more, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights has ruled that self-determination is not exclusive to indigenous communities (strictly defined), but a right that applies to all groups with traditional land claims, such as rural smallholders and Afro-descendants.Footnote2

Similarly, within transnational market space CSR norms have established voluntary, but expected, duties of care which lend themselves to participatory decision-making practices. For instance, corporations’ societal obligations have been generically framed around ‘negative’ and ‘affirmative’ duties. Whereas the former denotes a minimum obligation to do no harm, the latter implies that they ought also to do some good (Simon et al., Citation1972). In fact, interviews with some mining company representatives indicate that, if their organizations are to be distinguished as ‘modern’ corporations, they must contribute to the wellbeing of communities at the earliest possible encounter.Footnote3 Likewise, top executives now widely define CSR as the ‘beyond-law’ obligations their companies have towards the economic, social, and environmental systems within which they are embedded (Dashwood, Citation2012). This entails, among other things, ensuring that all facets of their operations respect human rights (Ruggie, Citation2013). While the sincerity of companies’ CSR proclamations ought not to be taken at face value, the fact they now endeavor to be seen as concerned with participatory decision-making is indicative of the ideational structures within which they must now operate.

Taken together, these principles and norms have informed a global rule of extractive development: For mega-mining activities to take place, governments and corporations should first confer with local communities with a view towards peacefully soliciting their approval. To operationalize this, a variety of analytically-distinct, but overlapping, decision-making procedures and practices have emerged over the past three decades. Chief among them include: Free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC); environmental impact assessments (EIAs); almost-FPIC; the social license to operate (SLO); and impact-benefit agreements (IBAs). For heuristic purposes, we contend that the salient cleavage among them pertains to whether they exhibit ‘regulatory’ or ‘market-enabling’ logics and characteristics.Footnote4

FPIC was introduced into the mining industry’s global governance architecture in 1989 through the International Labour Organization’s (ILO) Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention (No. 169). Although the treaty was only ratified by 22 states, 144 expressed a non-binding commitment to FPIC in 2007 through the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. For those subject to the ILO treaty, FPIC must be formally enshrined in national law, thereby requiring central governments to act as the primary guarantors of local communities’ right to self-determination. While the ILO treaty refrained from providing an implementation blueprint, FPIC entails that appropriate national agencies convene public forums with communities before their lands can be offered-up for concession. At minimum, they should be unencumbered by material inducements and coercive threats, and ensure that local communities be able to deliberate with full and accurate information which has been communicated to them in a culturally-appropriate manner. Failing this, the judicial arm of the state has a duty to intervene to prevent ‘unauthorised intrusion’ upon local lands (ILO, Citation1989, art. 18). Naturally, the thorniest issue has pertained to what ‘consent’ implies from a procedural standpoint. For instance, some suggest strict consensus is an unrealistic measure of community approval and that a simple- or super-majority could suffice (Goodland, Citation2004, p. 68), while others argue that, regardless of numerical threshold, validity requires consent to be formally registered through ‘positive’ and ‘demonstrable’ legal acts, such as signatures or ballots (Szablowski, Citation2010, pp. 118–119). Although much ink has been spilled over whether the spirit of the law implies communities possess veto powers (Barelli, Citation2012), corporations have interpreted it to signify precisely that (Szablowski, Citation2010). Still, even though FPIC prevents states from simply invoking eminent domain, community opposition can be overridden if it can be shown through courts that such actions are ‘necessary’ for the public good and will be implemented in a manner that is ‘least restrictive from a human rights perspective’ (Cariño & Colchester, Citation2010, pp. 429). In sum, due to the transaction costs it generates for states and corporations, and importantly, its potential to ensure that community opposition is enforceable by law, FPIC has been described as one of the most robust regulatory mechanisms within the mining industry’s global governance architecture (Filer et al., Citation2020). However, despite being widely proclaimed in licensing processes, FPIC has not been adequately implemented by states, if at all (Broad, Citation2014; Szablowski, Citation2010).

Similarly, EIAs represent another regulatory mechanism through which local communities can be consulted and have the potential to halt newly proposed projects. EIAs proliferated internationally following the 1972 United Nations Conference on the Human Environment, with many global South countries enshrining them in national laws during the 1980s and 1990s (Glasson et al., Citation1994). Like FPIC, they are to be conducted at the project level and administered by the relevant national authority (e.g. environment ministry), but differ in that they generally occur after corporations have received concession permits. On one hand, they are technocratic exercises in risk management, but on the other, they have increasingly come to function as participatory decision-making instruments whereby interested parties publicly debate the wider social value of newly proposed projects. This has been particularly true in Latin America, where several national governments have responded to environmental justice movements by introducing laws which require impacted communities to have a seat at the table in the EIA review process (Urkidi & Walter, Citation2011). This has acted, moreover, as a vertical check-and-balance against institutionalized biases within some countries, including the powers of environmental review being held by the very ministries which promote mineral development (Bebbington, Citation2012). While the procedural terrain upon which EIAs are conducted may not be as advantageous to local communities as FPIC, since states have already signaled some provisional support for projects, they can nevertheless facilitate the possibility for evidence to come to light, or social pressure to galvanize, which empower them to demand better terms and conditions, or press state authorities to reject them outright. In sum, EIAs are intended to distil the struggles of competing interest groups ‘into a single outcome’ on whether a development project will be ‘built in a particular way, or is not built’ (Hochstetler, Citation2011, p. 353). Crucially, since most countries have not ratified ILO Convention 169, they often represent one of the few regulatory mechanisms local communities have at their disposal to engage in a participatory decision-making process which approximates FPIC.

In response, the global mining industry has advanced a set of market-enabling mechanisms which do not entail the same levels of state oversight, much less risks of community veto. For instance, despite acknowledging the imperative to ‘respect the individual and collective rights’ of communities, and importance of ‘work[ing] to obtain consent’ (ICMM, Citation2010, pp. 28–29), corporations have increasingly promoted an ‘ambiguous hybrid’ version of the FPIC standard best described as ‘almost-FPIC’ (Szablowski, Citation2010, pp. 118–119). In short, while it broadly acknowledges ILO Convention 169, it is not designed to support deliberation over the type of development communities desire, but to ‘facilitate project development’ by relaxing the threshold of assent (ibid). The origins of almost-FPIC can be traced to the World Bank’s Extractive Industries Review, which sought to establish ‘free, prior, and informed consultation’ as a standard operating procedure, while encouraging companies to acquire ‘broad support’ for their projects (World Bank, Citation2004, p. vi). The Bank’s private sector lending arm, the International Finance Corporation (IFC), subsequently enshrined this interpretation in both iterations of its influential Performance Standards for Social and Environmental Sustainability (IFC, Citation2006, Citation2012). While industry actors have since used the terms ‘consultation’ and ‘consent’ interchangeably, the former implies that the viability of a project need not be grounded in what a community collectively thinks of it, but simply by the attempt to confer with them. But equally, by using ‘broad support’ as a marker of approval, firms can more easily influence state managers by signaling that they have received a community’s ostensible blessing, as this woolly term lends itself to ‘less visible and more passive’ expressions of acceptance, such as informal or private agreements with select stakeholders (Szablowski, Citation2010, pp. 118–119). Consequently, some argue almost-FPIC gives communities the right to approve, but not reject, mining projects (Cariño & Colchester, Citation2010, p. 432).

Similarly, firms have utilized their discretionary community relations activities to facilitate early dialogues aimed at garnering the elusive ‘social permission’ of the groups they deem to be key arbiters of mineral development. Here, the SLO and IBAs represent two interrelated practices that have guided corporations in their approach to community assent. Unlike a state permit, the SLO is a ‘de facto rather than de jure requirement’ for project approval (Constanza, Citation2016, p. 98). Broadly, it refers to the social contract corporations seek to construct and maintain with fence-line communities, and which is now used as a rhetorical signal to state authorities that local acceptance has been achieved (Prno & Slocombe, Citation2012). While informal, it can hinge upon the extent to which they engage communities in a transparent, culturally-sensitive, and procedurally-fair manner (Moffat & Zhang, Citation2014). Still, obtaining a SLO is rarely the result of an unadulterated tête-à-tête, as corporations have also sought to send credible signals that communities will gain materially if they support their investments. Here, IBAs have played an instrumental role in manufacturing consent. As the name implies, they represent negotiated settlements with select local groups pertaining to the transfer of material goods/services in exchange for acquiescence. Since IBAs are typically negotiated in the absence of state or third-party oversight and protected by non-disclosure agreements, content analyses remain scant. However, it is believed that they generally reference windfall payments, employment/training programs, and infrastructure projects (Caine & Krogman, Citation2010). In short, while IBAs entail a bargaining process which communities can utilize to influence the terms and conditions of project approval, they do not entail possibilities for debate over alternative development opportunities. Thus, they not only restrict deliberative space, but can also function as side-payments which fragment the collective power communities could otherwise exercise.

All said, a regime-level approach can allow observers to better theorize the contradictions of prior consultation, including the ways in which it, seemingly paradoxically, aggravates conflict.

A critical political economy of governance capture

While a critical political economy of environmental governance approach conceptualizes regimes as multi-stakeholder and multilevel phenomena, it does not treat them as pluralist spaces wherein state, market, and civil actors influence outcomes on an even keel. On one hand, it acknowledges that civil society can wield discursive powers that challenge and shape ideational structures within discrete issue areas (Gale, Citation1998). Yet, on the other, it recognizes that environmental governance is ‘embedded within broader relations of political and economic power which determine the limits of the possible’ (Newell, Citation2008, p. 529). Furthermore, it is critical in the sense that it conceptualizes regimes not as rational-functional responses to specific problems, but contentious compromises which ultimately reflect and advance particular interests (Cox, Citation1981). In short, it theorizes regimes as arenas of constant discursive, organizational, and institutional struggle within the wider ideational and material structures of global capitalism.

In this vein, we suggest that the concept of governance capture provides an apt characterization for understanding the implications of the market-enabling mechanisms previously outlined. Moreover, we believe its application to the global mining industry can make a novel empirical contribution to international political economy, as ‘capture’ scholarship has focused primarily on the international banking/financial sector (Goldbach, Citation2015; Lall, Citation2012; Young, Citation2012). In short, ‘capture’ accounts for how the proverbial ‘rules of the game’ designed to safeguard vulnerable groups from the deleterious effects of the market can systematically skew towards the advantage of entrenched capitalist interests. For instance, state capture describes a process whereby a central government apparatus is seized by economic elites for particularistic gain. While the concept was originally developed to explain corruption and cronyism within post-Soviet transition economies (Hellman et al., Citation2000), it can also apply to consolidated democracies (You, Citation2021). This is because central governments need not be hijacked far-and-wide for regulatory frameworks to reflect systematic bias, as it is often sufficient to target only those agencies and processes responsible for the ‘rules of economic game’ (Crabtree & Durand, Citation2017). Equally, business interests can undermine the disciplinary capacity of regulation through entirely legal methods, such as lobbying, or because so-called ‘revolving doors’ exist between the public and private sectors (Dal Bó, Citation2006). What is more, the structural power of capital can indirectly influence the willingness of state managers to enforce laws on the books, as they may fear losing out on opportunities for foreign direct investment (Strange, Citation1988). Importantly for our purposes, capture need not be conceptualized as an exclusively domestic regulatory phenomenon, as it can also occur within intergovernmental and transnational spaces, and thereby bias multilevel governance frameworks as well (Baker, Citation2010).

Accordingly, we interpret the prior consultation regime as having become increasingly subject to governance capture, as the introduction of market-enabling mechanisms effectively stacks the cards against the very groups and interests it was intended to safeguard in the first place. While broadly congruent with the regime’s first principles and norms, they make it more difficult for grassroots environmental actors and local opponents of mining to work through the prevailing procedural landscape to influence licensing outcomes. However, we do not attribute this skewing of the procedural terrain to bribery, lobbying, or revolving doors per se, but to the discursive and institutional powers this global industry has exercised in response to the reputational and operational threats posed by the regime’s first principles, norms, and regulatory mechanisms. To account for this, we draw upon neo-Gramscian governance theory, as it is attentive to how discursive and institutional contestation and accommodation intersect to induce incremental shifts within regimes.

From the perspective of neo-Gramscian governance theory, transnational struggles which involve social and regulatory threats to entrenched capitalist interests can be understood as broadly analogous to the processes of constructing and resisting hegemonic orders (Levy & Egan, Citation2003; Levy & Newell, Citation2002). According to Gramsci (Citation1971), hegemony described a situation of ideological rule whereby elites sought to manufacture active consent for unequal power relations. The most durable exercise of power was achieved when their core interests had penetrated civil societies to such an extent that an ‘uncritical conception of the world’ became the prevailing ‘common sense’ (Birchfield, Citation1999, p. 44). However, unbridled hegemony could never be guaranteed in practice, as the ideas and social relations which strung hegemonic orders together were subject to constant resistance, including in the form of a ‘passive revolution’ which involved incremental and ostensibly modest ideological and institutional challenge (Gramsci, Citation1971). As such, elites had to hedge against oppositional forces and actors through seemingly conciliatory acts, and coalitions purporting a mutuality of interests. Crucially, they had to exercise a ‘moral and intellectual leadership’ role by engaging progressively with critique (Robinson, Citation2005, p. 564). Here, Gramsci’s concept of ‘trasformismo’ is instructive for understanding the strategic logic underpinning market-enabling procedures/practices, as it accounts for how mining corporations endeavor to manage ideational and regulatory changes that risk altering capitalist power relations.

Trasformismo describes a strategy whereby capitalist elites proactively engage with critical ideas and related practices in a bid to reproduce the status quo. On one hand, it recognizes that, for all their material and organizational advantages, they cannot simply run roughshod over the values, beliefs, and demands of civil society. Yet, on the other, it recognizes that those very things are instrumental for consensual legitimacy. Thus, trasformismo involves elites accepting that preservation of the status quo requires acceding to modest institutional reforms which do not significantly disrupt underlying capitalist power relations. But, rather than simply mollifying critics through tokenistic concessions, it also entails actively ‘assimilating and domesticating potentially dangerous ideas by adjusting them to the policies of the dominant coalition’ with a view to ‘obstruct[ing] the formation of organized opposition to established social and political power’ (Cox, Citation1983, pp. 166–167). In short, this strategy of political accommodation is about neutralizing oppositional forces and actors through discursive and institutional pathways.

While neo-Gramscian theory has been used to explain hegemonic power at the macro-level of world orders (Cox, Citation1983; Gill & Law, Citation1989), it can also be applied to their respective meso- and micro-levels (Constanza, Citation2016; Gale, Citation1998). For instance, it has been used to account for how the global automotive and oil and gas sectors have sought to preempt policymakers from prioritizing carbon taxation as a means for reducing emissions (Levy & Newell, Citation2002). Similarly, it has been used to show how the emerging global green energy transition is likely to ‘reinforce a market liberal approach’ which focuses primarily on technological innovation, as opposed to ‘more sweeping transformations’ centered around production and consumption (Newell, Citation2019, p. 29). Like these studies, we treat the essence of governance struggle within the prior consultation regime as one which involves the exercise of discursive and institutional powers from ‘above’ and ‘below’, with corporations seeking to maneuver around potentially threatening regulatory interventions within the social and legal parameters set by transnational norms. For this reason, the regime’s market-enabling mechanisms can be understood as manifestations of a trasformismo strategy, which has been executed primarily in response to the risks of community veto associated with FPIC and EIAs.

As noted, the prior consultation regime is founded upon a set of principles and norms which have prompted states and corporations to solicit the views of local communities, and moreover, give them fair consideration when deciding whether, or under what conditions, to formally authorize projects. On one hand, its ideational foundations are a testament to the agency of indigenous peoples, environmental justice movements, and human rights advocates in ‘naming and shaming’ mining corporations, and lobbying states and intergovernmental organizations for safeguard measures. Combined, their activism and moral entrepreneurship has created a global social environment whereby it is now a reputational and legal risk for states and corporations to openly eschew the self-determination of local communities, as many had done for much of the 19th and 20th centuries. Yet, in response, the global mining industry has also exercised precisely the type of ‘moral and intellectual leadership’ associated with hegemonic power, as evidenced by the multi-pronged effort to co-opt the very idea of community ‘consent’. For instance, rather than simply reject FPIC outright—an act which could elicit social opprobrium or the loss of institutional investors—firms have instead worked through an authoritative international organization (i.e. World Bank) to subtly adjust its very meaning such that it can be redirected towards legitimating mining without robust deliberation. On one level, almost-FPIC achieves this simply by relaxing how state managers ought to measure community assent or by providing them with a rhetorical foil for legitimating otherwise predetermined investment decisions. But more fundamentally, by engaging with a practice deemed to be socially responsible, corporations can bolster their private authority and prompt states to defer to market-enabling governance mechanisms. What is more, by engaging proactively with critique, firms can construct what amounts to a ‘common sense’ around prior consultation, as some evidence suggests that even communities have now become more likely to conflate the SLO with FPIC (Overduin & Moore, Citation2017). Finally, consistent with trasformismo’s divide-and-rule strategy, IBAs can allow corporations to better cultivate sympathetic local agents who can be deployed to disarticulate collective anti-mining positions that would otherwise have to be considered within the EIA review process. This is because the direct transfer of material benefits can alter the rational calculations local recipients make when contemplating whether to join anti-mining opposition as the ‘perceived costs’ of publicly criticizing projects increase (Haslam, Citation2021).

Yet, for all its discursive and institutional dynamics, the governance struggle involving prior consultation also has existential implications. As we illustrate, in countries where corporate or national development interests are privileged, some local groups who oppose mining can be left with few options but to take risky actions to exercise voice.

Inauspicious beginnings

Here, we consider Brazil and Peru as illustrative vignettes. When examined together, they approximate a most different systems selection strategy. This is because, for much of the past two decades, Brazil and Peru diverged in terms of their extraction-led development models. Between 2003–2016 Brazil pursued a ‘post-neoliberal’ approach, whereby leftist governments promoted export-oriented development, but attempted to ensure the state played an ‘enhanced’ regulatory and redistributive role, while also championing the rights of marginalized communities (Grugel & Riggirozzi, Citation2012). By contrast, since the early 1990s Peru has been a proponent of the neoliberal approach to export-oriented development, which has included the state offloading several of its responsibilities for mediating mineral development to the market (Szablowski, Citation2007). Yet, despite this salient contextual difference, violent conflicts involving the self-determination claims of local communities have persisted in both countries, suggesting that contextual factors alone do not account for the similarities.

Brazil

For many decades, Brazilian legislation has mandated environmental licensing. For example, in 1970 the Special Secretary for the Environment was created, which, despite its limited authority, oversaw environmental management activities. Moreover, the National Environmental Policy of 1981 further enshrined environmental licensing practices. Later, the Federal Constitution of 1988 required that impact assessments be conducted prior to all industrial projects taking place (MMA, Citation2023). In 2002, Brazil ratified ILO Convention 169, and in 2007 signed the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. From 2003–2016 center-left administrations sought to strike a balance between reaping the windfalls associated with the global commodity super-cycle and remaining attentive to the socio-environmental consequences of extractive development. However, the increasing ‘reprimarization’ of the economy also served to bolster extractive interests (Cooney, Citation2021). Indeed, this was true for many left-leaning Latin American governments that pursued ‘progressive neoextractivism’, as their legitimacy hinged, in part, upon the expansion of social welfare programs financed by raw commodities (Gudynas, Citation2009). Environmental licensing procedures in Brazil have therefore been beset by administrative deficiencies, which have resulted in projects with substantial risks being approved (Duarte et al., Citation2017). Thus, it has been criticized as a formality which seldom results in the cancellation of projects (Santos and Milanez, Citation2017). Within this wider context of biased management and structural constraint there has been a rise in socio-environmental conflicts. For example, in 2021 observers reported 840 conflicts which affected more than 750,000 people, many of which involved mega-mining projects that encroached upon indigenous and quilombola (Afro-descendant) communities, and involved various forms of physical violence (CNDTFM, 2021).

Problematic processes of prior consultation have also been a salient factor in the elevation of conflict risks—an observation supported by interviews with community activists. For instance, while advancements have been made in recent years in terms of ensuring that some type of consultation takes place, many companies are often regarded as having already ‘clear[ed] the terrain’ before deliberations occur, effectively preventing parties from debating alternative development opportunities. Moreover, mining companies are believed to frequently procure interlocutors who do not adequately/accurately represent communities’ interests, but are pre-inclined to extractive development.Footnote5 IBAs have also been a useful tool in this regard, as regular cash handouts have been used to win over some local leaders and strengthen the political position they exercise within their respective communities due to their ability to distribute material resources.

In a similar vein, concessions for large-scale projects are rarely based on robust dialogue with communities, but rather are typically conducted after ground has already been broken. As one indigenous leader highlighted:

When the idea surges, it is already very matured … and most of the major projects are planned in this way. We understand that if there were more involvement on behalf of the communities, be they indigenous, quilombolas or ribeirinhos, communities that would either be directly or indirectly impacted by certain projects, and this participation was from the very conception of the idea, and the discussions were open, frank, transparent, and characterized by accessible information, then maybe many of the impacts which the projects generate afterwards, in the implementation phase – which is when the communities normally aren’t consulted today – would be much smaller in relation to the specific project. And the social movements – especially the indigenous movement from which I come – react because of this. It is a strong and blunt reaction, especially in relation to projects in the Amazon, because they [communities] are not consulted, and they are not heard, and not engaged in these discussions.Footnote6

Recent cases of controversial mining projects indicate the role of weak prior consultations in conflict. For example, this was evident at the Fundão project in Mariana, which led to a disastrous tailings dam failure in 2015 that killed 18 people and generated environmental damage so widespread that it was roundly declared the worst mining disaster in Brazilian history. Despite evidence of structural problems with the dam in the years preceding the collapse, the company, Samarco, did not have its legal license to operate revoked. By contrast, it received awards for its business conduct and ostensibly high level of transparency. Between the time of Fundão’s inauguration in 1996 and the 2015 disaster, Samarco accumulated a total of 19 legal infractions for a variety of environmental offences. However, the fines were merely performative, with subsequent state inspections marred by allegations of undue corporate influence. This situation ultimately reflects the wider structural and instrumental power mining companies have exercised, with elected officials from the local to federal levels having received campaign finance from companies linked to Samarco’s owner, the Vale Group (Milanez et al., Citation2016). In the absence of strict public regulatory measures, Samarco relied strongly on its purported SLO, even though it had not conducted robust consultations with local communities before it was approved. In line with the SLO strategy, targeted but otherwise limited efforts were made to obtain community legitimation, with some arguing that it was complicit in covering-up the grave socio-environmental risks posed by the operation (Demajorovic et al., Citation2019). Following the disaster, in 2015 protests targeted what was viewed as a situation of impunity and insufficient compensation, but were met with violent responses from local police forces (Motta, Citation2016). In this case, state actors acted in dereliction of their environmental regulatory duties, and further reflected corporate interests by repressing citizens who attempted to hold Samarco to account for the disaster.

The Volta Grande Project along the Xingu River provides another example of how attempts to bypass robust prior consultation procedures have sparked community protests. Located at the ‘big bend’ of the Xingu River, the project is slated to commence after the Belo Monte Dam has finished diverting the river’s natural water flow. The project’s Canadian owner, Belo Sun, presented its EIA in 2012. However, local indigenous communities accused the company of inadequate consultation efforts. Since then, licenses have been granted and subsequently revoked, with local authorities locked in a conflict with the central government. If developed, it would be the largest open-pit gold mine in Brazilian history. In its official sustainability report, Belo Sun claims to have followed international best-practice standards for constructing a SLO stating that ‘ongoing cooperation and acceptance of our impacted communities is an utmost priority’ and that it has ‘established a climate of transparency and confidence with our communities’ since it acquired the concession in 2003 (Belo Sun, Citation2022). Belo Sun has also adopted different IBA-style practices, including through the construction of community facilities and local hiring and acquisition policies (ibid). Still, the project has faced staunch resistance from communities throughout the region, especially the Juruna Yudjá indigenous people who claim that the state and company have not consulted them in a manner consistent with FPIC. Despite court rulings against the project, it received strong support from the executive branch of government during the presidency of Jair Bolsonaro (2019–2023), which made significant efforts to attract international mining investment to the Amazon region. What is more, during the deadliest years of the COVID-19 pandemic, the state tried to push ahead with the project by insisting that prior consultations be conducted in-person despite the obvious health threats posed to local indigenous populations from the virus (Mantovanelli, 2021). The project has also raised serious concerns about the possible forced displacement of populations in nearby villages, and threats against locals have been made by armed security guards hired by Belo Sun (Amazon Watch, Citation2022). In recent years, this has led to protests, as rural workers, indigenous groups, and riverine communities have occupied the lands under concession to draw international attention to the need for more robust prior consultation procedures and for the state and company to respect their territorial rights (Junqueira, Citation2022). Despite court orders mandating that the project be suspended, Belo Sun continues its prospecting activities and has consistently downplayed the significance of these legal decisions. This has contributed to accusations against the company for breaches of the disclosure requirements under the Canadian Securities Act, with allegations that it has also disseminated misleading/incomplete information to investors (Bloomberg, Citation2021). The Volta Grande project not only illustrates the alliance between international capital and central authorities, but the state’s selective and strategic use of prior consultation procedures.

Peru

Peruvians often describe their country as a país minero (mining country) due to the centrality that minerals and mining interests have played in its long-run institutional and economic development. While mining was largely responsible for fueling the country’s strong growth performance between 2002–2013, during which time the national poverty rate was cut by more than half (World Bank, Citation2017), it has also been criticized for the violence it generates in host regions.Footnote8 Indeed, most socio-environmental conflicts recorded annually by the national ombudsman have been associated with mega-mining projects (Defensoría del, Citation2019). At the national level, a major factor underpinning this has been the fervor with which central authorities in Lima have protected mining interests. Since the country’s neoliberal turn in the early 1990s, the state has effectively been transformed into a defender of foreign direct investment (Crabtree & Durand, Citation2017), with successive presidents also making ‘legal and ideological commitments to limit the regulatory burden placed on extractive firms’ (Szablowski, Citation2010, p. 113). Still, one of the most egregious indicators of the state’s willingness to protect mining interests has been the passing of laws which, according to one local activist, allow corporations to treat public security forces ‘as if they were their own mercenary armies’.Footnote9 For example, in 2009 a presidential decree (No. 004-2009-IN) permitted mining corporations to formally sub-contract police and military units to provide them with protection related services above and beyond those which they already received from private security contractors. In 2010, another law (No. 1095) permitted military personnel to assist police with managing public demonstrations against so-called ‘strategic installations’. Finally, in 2014 a law was passed (No. 30151) to protect police and military personnel from being tried in civilian courts if their actions during protests led to the unlawful death and/or abuse of citizens. In short, the Peruvian state has been anything but a neutral mediator when managing the competing interest of foreign capital and local communities.

While the material-economic concerns of local communities have driven many conflicts at operational mines (Orihuela et al., Citation2022), when and where new investments have been proposed, demands for self-determination and related calls for the state to respect ‘alternative’ visions of development have also acted as salient triggers (McDonell, Citation2015). These grievances have even led to violent confrontations despite the multi-stakeholder deliberation procedures the state formally has in place to integrate local groups into project licensing. For example, it ratified ILO Convention 169 in 1993 and signed the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in 2007. Furthermore, in 2011 it passed Latin America’s first prior consultation law, which explicitly recognized that decision-making processes pertaining to mega-projects should strive towards ‘agreement or consent between the State and [affected] peoples or natives [i.e. indigenous groups]’ (Law No. 29785). Equally, since 1993 project approval has been conditional upon EIA review (Law No. 016-93-EM), a process which, in 2002, integrated local talleres (workshops) and audiences públicas (public hearings) as participatory mechanisms for communities to influence decision-making outcomes (Law No. 596-2002-EM). Nevertheless, in practice the state has often sought to shirk its international obligations, including by using the Fujimori-era Constitution to assert the power of eminent domain on behalf of foreign business interests (Coxshall, Citation2010). Furthermore, despite incorporating local communities into the EIA review process and increasingly seeking technical support from the environment ministry, the country’s mining ministry exercises final say over the status of proposed projects, and moreover, has been criticized for regularly ignoring strong evidence of environmental risk to local communities.Footnote10 Finally, the Peruvian state has, more broadly, pursued a regulatory strategy of ‘selective absence’, whereby it ‘more or less covertly’ allows mining corporations to assume key resource governance functions under the guise of CSR, including those pertaining to prior consultation (Szablowski, Citation2007, p. 74). Combined, these factors have generated a procedural environment that is highly antagonistic to non-extractive interests. Still, local opponents of mining have, at times, been able to halt controversial projects through protest action.

Indeed, emblematic cases of socio-environmental conflict not only exemplify the salience of competing claims to prior consultation at the project licensing stage, but also indicate how, as a result, local actors have been left with little choice but to take risky action to draw attention to procedural injustices, or force central authorities to respect their right to say ‘no’. For instance, in 2004 residents of the town of Tambogrande in the region of Piura prevented the Canadian mining company, Manhattan Minerals, from developing a gold and copper mine worth an estimated US $315 million. Tensions were high from the moment the concession was awarded in 1999, as no formal FPIC procedure had taken place—a curiosity given that the project required half of the town’s 16,000 residents to be relocated to access the deposit. Residents not only rejected the project’s proposed resettlement measures, but argued that, if developed, it would consume and pollute groundwater from the San Lorenzo valley, which many families relied upon for small-scale agricultural and pastoral activities. Due to a combination of grievances surrounding governance failures and socio-environmental impacts, residents openly protested in late-February 2001, but were met with heavy police repression. This state response triggered an escalation that led to the company’s main offices in the town being sacked and equipment destroyed. One month later, a prominent environmental activist was murdered in a thinly-veiled attempt to deter further protest. To ease tensions and reestablish lines of communication in the wake of these events the company agreed to participate in EIA deliberations mediated by the national ombudsman, which it insisted would be democratic and respond to the concerns expressed by community representatives (Haarstad & Fløysand, Citation2007, p. 300). But it also conducted parallel ‘consultations’ through a local radio program in an attempt to construct a SLO (Paredes, Citation2016, p. 1051). Still, many residents argued that both interventions were largely performative and ignored popular will, which was firmly against the mine. Thus, in 2002, with the help of an international NGO, they organized a ‘community referendum’ branded ‘illegal’ by state officials and Manhattan Minerals in which 98% of voters rejected the project. Not only was this an important symbolic act, but also indicative of the need for opponents to operate outside the procedural landscape to exercise self-determination. While some argue that this case stands out for the efficacy with which locals constructed a broad-based coalition capable of levying (inter)national opprobrium against the project (Haarstad & Fløysand, Citation2007), one observer who closely covered the events intimated that the ever-present threat of direct action also played a key role, as central authorities cancelled the project fearing further escalation and reputational damage.Footnote11

Similarly, throughout 2011–2012 mass protests erupted throughout the region of Cajamarca in response to the approval of the Conga gold mining project. Valued at approximately US $5 billion, it was billed as the largest mining investment in Peruvian history. However, to access the deposit, the mine’s multinational owner, Minera Yanacocha, would have to drain two high altitude lakes, and convert two others into tailings ponds. Many rural and urban communities surrounding the concession insisted the lakes were headwaters that supplied numerous stakeholders downstream, and that Yanacocha’s planning and impact mitigation measures lacked an ‘ecosystemic focus’.Footnote12 While this outbreak of protests was the latest escalation of a two-decades long conflict between the residents of Cajamarca and the company (De Echave & Diez, Citation2013), procedural injustices in the licensing process were a contributing trigger as no FPIC procedure took place before the concession was awarded, with the project’s EIA review being criticized as a mere formality aimed at authorizing an otherwise predetermined investment decision.Footnote13 Still, despite these criticisms, Yanacocha insisted that it had obtained a SLO through its ‘Days of Dialogue’ program, which it claimed involved deliberations with approximately 16,000 residents from several districts immediately surrounding the project (Newmont Mining Corporation, n.d.). One company insider argued, furthermore, that its activities adhered to the IFC’s Performance Standards and were thus consistent with prevailing international norms governing prior consultation.Footnote14 However, some residents challenged the very validity of the company’s activities:

What happened on the dialogue days? They spoke about things that had nothing to do with the Conga project! They talked about swine flu, or how to improve local businesses. I know because I participated and refused to sign their agreement saying that we granted a social license … Those ‘dialogues’ were a sham … Our people are fighting to be properly included in consultations about the project.Footnote15

Conclusion

The global mining industry’s prior consultation regime has become incrementally geared towards the social and legal engineering of resource extraction. At the procedural level, it bears the hallmarks of corporate capture, strategically marginalizing the very groups and interests it was intended to incorporate and safeguard in the first place. While a testament to the collective agency of civil society actors in cajoling corporations and states into recognizing the need for inclusivity and deliberation in local decision-making, it has subtly shifted to legitimize extractivism. Indeed, this observation accords with other recent findings on how business interests reproduce their dominant position through seemingly progressive engagement with global discourses and governance arrangements (Le Billon & Spiegel, Citation2022; Newell, Citation2019). Our analysis also suggests that the regime has become violently entangled with place-based struggles, as local actors who reject mineral development now confront a procedural landscape which is much more antagonistic to their interests. While the regime reflects hegemonic power, this does not mean local communities are, ipso facto, condemned to dispossession and despoliation, as evidence indicates that they can, and do, succeed in exercising their right to self-determination. However, such victories are likely to come at a price, as decisions to halt projects are usually taken only after local lives have been brutally extinguished, and reputational harms to governments and companies have become too great to ignore.

Looking forward, our analysis can also shed light on what is at stake for those at the peripheries of the global system in the green energy transition. Currently, global policymakers have prioritized a market-friendly decarbonization model which relies heavily upon the worldwide proliferation of wind, solar, hydro, and geothermal power systems, and related consumer products (e.g. electric vehicles). Yet, for all the benefits these technologies can have in the fight against climate change, it is projected to be ‘mineral-intensive’, as renewables require key mineral inputs, such as aluminum, copper, lithium, and nickel (Hund et al., Citation2020). To meet demand, many global South countries are likely to face renewed pressures to ramp-up mineral production, which may also entail having to explore new and highly controversial extractive frontiers (e.g. deep-sea mining). Thus, despite its benign popular image, the dominant green energy paradigm is predicated upon the intensification of industrial mining activities.

To ensure that communities positioned at the lower rungs of green energy supply chains are not thereby rendered subordinate to the ‘greater global good’ of decarbonization, but equally, that their right to self-determination is given due consideration, a reinvigoration of the regime’s first principles is necessary. Indeed, there remains little prospect for a maximally ‘just transition’ if the procedural inequalities and failings within the global governance architecture of the very industry which underpins the green energy paradigm are not first rectified. What is more, by re-empowering local voices in this process, discursive space is more likely to be created for serious policy discussions over ‘alternative’ development opportunities, as prior consultation struggles often entail ontological and epistemological clashes between actors who espouse ‘deep’ ecological worldviews and hegemonic environmentalisms. If states robustly abide by their international obligations to protect local communities’ right to self-determination, then the prior consultation regime has the potential to contribute to a more inclusive, democratic, and transformational low-carbon future.

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend our sincerest thanks to the three anonymous reviewers for their insightful and constructive feedback, as well as those who attended the ‘Private Sector’s Role in Inclusive Governance’ panel at the 2019 ISA Toronto Conference, where an earlier version of this paper was presented. We are also deeply indebted to numerous friends and colleagues for their support and guidance during the drafting process, but particularly Jana Evans and Scott Lavery.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jonathan Kishen Gamu

Jonathan Kishen Gamu is an Assistant Professor in International Politics at the University of Sheffield, England. His research examines the intersections of corporate power, resource extraction, and the environmental politics of violence.

Niels Soendergaard

Niels Soendergaard is an Assistant Professor in International Relations at the University of Brasilia, Brazil. His research focuses on political economy, with an interest in commodity production, trade, and governance.

Notes

1 Fieldwork/interviews received ethical clearance from the first author’s institution.

2 See the 2007 Saramaka People v Suriname ruling.

3 Interviews: mid-level CSR manager, Lima, Peru 28 April 2014; mid-level community relations manager, Lima, Peru 8 May 2014; senior sustainability manager, Toronto, Canada 13 April 2016.

4 We use these stylized distinctions to understand the extent to which decision-making procedures and practices function to empower the interests of grassroots actors or private capital. Regulatory procedures and practices are grounded in a ‘social protection’ ethic and more likely to place constraints on corporate activity by invoking the interventionist powers of the state. Market-enabling procedures and practices are grounded in a ‘laissez-faire’ ethic and less likely to constrain corporate activity as they assume that the market can self-regulate against harm (Levy & Prakash, Citation2003; Polanyi, Citation1944).

5 Interview: environmental NGO representative, Brasília, Brazil, July 1, 2019.

6 Interview: indigenous leader, Brasília, Brazil, July 1, 2019.

7 ibid.

8 Interview: national Ombudsman representative, Lima, Peru 21 March 2014.

9 Interview: local activist, Celendín, Peru, 12 September 2014.

10 Interview: former senior Environment Ministry official, Lima, Peru 20 February 2016.

11 Interview: journalist and documentarian, Cusco, Peru 13 June 2014.

12 Interview: former senior Environment Ministry official, Lima, Peru 5 May 2014.

13 Interview: regional Ombudsman representative, Cajamarca, Peru 15 September 2014.

14 Interview: local CSR manager, Cajamarca, Peru, 19 September 2014.

15 Interview: local activist, Celendín, Peru, 3 July 2014.

References

- Amazon Watch. (2022). The risks of investing in Belo Sun. https://amazonwatch.org/news/2022/1209-the-risks-of-investing-in-belo-sun

- Anaya, J. (2013). UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. 68th Session of the General Assembly October 21, 2013. New York.

- Baker, A. (2010). Restraining regulatory capture? Anglo-America, crisis politics and trajectories of change in global finance governance. International Affairs, 86(3), 647–663. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2346.2010.00903.x

- Barelli, M. (2012). Free, prior and informed consent in the aftermath of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples: Developments and challenges ahead. The International Journal of Human Rights, 16(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642987.2011.597746

- Bebbington, A. (2012). Extractive Industries, Socio-Environmental Conflicts, and Political Economic Transformations in Andean America. In A. Bebbington (Ed.), Social Conflict, Economic Development, and the Extractive Industry: Evidence from South America., 3–26. Routledge.

- Belo Sun. (2022). Responsibility: Environment, responsibility, governance. https://belosun.com/responsibility/overview

- Birchfield, V. (1999). Contesting the hegemony of market ideology: Gramsci’s ‘good sense’ and Polanyi’s ‘double movement. Review of International Political Economy, 6(1), 27–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/096922999347335

- Bloomberg. (2021). Investor alert: Belo Sun discloses misleading information to investors regarding controversial gold mining project. Bloomberg Business, July 29.

- Bowles, P., MacPhail, F., & Tetreault, D. (2019). Social license versus procedural justice: Competing narratives of (il)legitimacy at the San Xavier mine, Mexico. Resources Policy, 61, 157–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2019.02.005

- Broad, R. (2014). Responsible mining: Moving from buzzword to real responsibility. The Extractive Industries and Society, 1(1), 4–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2014.01.001

- Bullard, R. (Ed.). (1993). Confronting Environmental Racism: Voices from the Grassroots. South End Press.

- Cariño, J., & Colchester, M. (2010). From dams to development justice: Progress with ‘free, prior, and informed consent’ since the World Commission on Dams. Water Alternatives, 3(2), 423–437.

- Comitê Nacional Em Defesa Dos Territórios Frente À Mineração (CNDTFM). (2022). Conflitos da Mineração no Brasil 2021: Relatório Anual, publicação do Comitê Nacional em Defesa dos Territórios Frente à Mineração, no âmbito do Observatório dos Conflitos da Mineração no Brasil. Brasil, novembro de 2022.

- Conde, M., & Le Billon, P. (2017). Why do some communities resist mining while others do not? The Extractive Industries and Society, 4(3), 681–697. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2017.04.009

- Constanza, J. (2016). Mining conflict and the politics of obtaining a social license: Insight from Guatemala. World Development, 79, 87–113.

- Cooney, J. (2021). Paths of Development in the Southern Cone: Deindustrialization and Reprimarization and their Social and Environmental Consequences. Springer.

- Cox, R. (1983). Gramsci, hegemony and international relations: An essay in method. Millennium: Journal of International Studies, 12(2), 162–175. https://doi.org/10.1177/03058298830120020701

- Cox, R. (1981). Social forces, states and world orders: Beyond international relations theory. Millennium: Journal of International Studies, 10(2), 126–155. https://doi.org/10.1177/03058298810100020501

- Coxshall, W. (2010). ‘When they came to take our resources’: Mining conflicts in Peru and their complexity. Social Analysis, 54(1), 35–51. https://doi.org/10.3167/sa.2010.540103

- Crabtree, J., & Durand, F. (2017). Peru: Elite Power and Political Capture. Zed Books.

- Cuffe, S. (2019). Indigenous Xinka march over contested Guatemalan mine. Aljazeera, February, 27. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/2/27/indigenous-xinka-march-over-contested-guatemalan-mine

- Dal Bó, E. (2006). Regulatory capture: A review. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 22(2), 203–225.

- Dashwood, H. (2012). The Rise of Global Corporate Social Responsibility: Mining and the Spread of Global Norms. Cambridge University Press.

- Dauda, S. (2022). Earning a social license to operate (SLO): A conflicted praxis in Sub-Saharan Africa’s mining landscape? The Extractive Industries and Society, 11, 101141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2022.101141

- De Echave, J., & Diez, A. (2013). Más allá de Conga. CooperAcción. https://cooperaccion.org.pe/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/00164.pdf

- De la Cadena, M. (2015). Earth Beings: Ecologies of Practice Across Andean Worlds. Duke University Press.

- Defensoría del, P. (2019). Adjuntía para la prevención de conflictos sociales y la gobernabilidad. Reporte de Conflictos Sociales No. 190 Gobierno del Perú.

- Demajorovic, J., Lopes, J. C., & Santiago, A. L. F. (2019). The Samarco dam disaster: A grave challenge to social license to operate discourse. Resources Policy, 61, 273–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2019.01.017

- Duarte, C. G., Dibo, A. P. A., & Sánchez, L. E. (2017). O Que Diz a Pesquisa Acadêmica Sobre Avaliação De Impacto E Licenciamento Ambiental No Brasil? Ambiente & Sociedade, 20(1), 261–292. https://doi.org/10.1590/1809-4422asoc20150268r1v2012017

- Dunlap, A. (2019). ‘Agro sí, mina NO!’ The Tía Maria copper mine, state terrorism and social war by every means in the Tambo Valley, Peru. Political Geography, 71, 10–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2019.02.001

- European Union-United Nations Partnership (EU-UN). (2012). Extractive Industries and Conflict. EU-UN.

- Filer, C., Mahanty, S., & Potter, L. (2020). The FPIC principle meets land struggles in Cambodia, Indonesia and Papua New Guinea. Land, 9(3), 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9030067

- Franks, D., Davis, R., Bebbington, A., Ali, S., Kemp, D., & Scurrah, M. (2014). Conflict translates environmental and social risk into business costs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111(21), 7576–7581. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1405135111

- Gale, F. (1998). Cave: ‘Cave: Hic dragones’: A neo-Gramscian deconstruction and reconstruction of international regime theory. Review of International Political Economy, 5(2), 252–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/096922998347561

- Gill, S., & Law, D. (1989). Global hegemony and the structural power of capital. International Studies Quarterly, 33(4), 475–499. https://doi.org/10.2307/2600523

- Glasson, J., Therivel, R., & Chadwick, A. (1994). Introduction to Environmental Impact Assessment: Principles and Procedures, Processes, Practices and Prospects. University College London Press.

- Global Witness. (2021). Last line of defense: The industries causing the climate crisis and attacks against land and environmental defenders.

- Goldbach, R. (2015). Asymmetric influence in global banking regulation: Transnational harmonization, the competition state, and the roots of regulatory failure. Review of International Political Economy, 22(6), 1087–1127. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2015.1050440

- Goodland, R. (2004). Free, prior, and informed consent and the World Bank Group. Sustainable Development Law & Policy, 4(2), 66–74.

- Gramsci, A. (1971). Selections from the Prison Notebooks. (Q. Hoare & G. Nowell, Eds. & Trans.). Lawrence & Wishart.

- Grugel, J., & Riggirozzi, P. (2012). Post-neoliberalism in Latin America: Rebuilding and reclaiming the state after crisis. Development and Change, 43(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.2011.01746.x

- Gudynas, E. (2009). Diez Teses Urgentes Sobre el Nuevo Extractivismo: Contextos y Demandas Bajo el Progresismo Sudamericano Actual. In J. Schuldt. (Eds.), Extractivismo, Política y Sociedad., 187–225. Centro Andino de Acción Popular.

- Gustafsson, M., & Schilling-Vacaflor, A. (2022). Indigenous peoples and multiscalar governance: The opening and closure of participatory spaces. Global Environmental Politics, 22(2), 70–94. https://doi.org/10.1162/glep_a_00642

- Haarstad, H., & Fløysand, A. (2007). Globalization and the power of rescaled narratives: A case of opposition to mining in Tambogrande, Peru. Political Geography, 26(3), 289–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2006.10.014

- Haslam, P. (2021). The micro-politics of corporate social responsibility: How companies shape protest in communities affected by mining. World Development, 139, 105322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105322

- Hellman, J., Jones, G., & Kaufman, D. (2000). Seize the state, seize the day: State capture, corruption, and influence in transition. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 2444. World Bank Group.

- Hochstetler, K. (2011). The politics of environmental licensing: Energy projects of the past and future in Brazil. Studies in Comparative International Development, 46(4), 349–371. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-011-9092-1

- Howse, T. (2022). Trust and the social license to operate in the Guatemalan mining sector: Escobal mine case study. Resources Policy, 78, 102888. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2022.102888

- Hund, K., La Porta, D., Fabregas, T., Laing, T., & Drexhage, J. (2020). Minerals for climate action: The mineral intensity of the clean energy transition. International Bank for Reconstruction and Development. World Bank Group.

- International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM). (2013). Indigenous peoples and mining: Position statement. ICMM.

- International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM). (2010). Good practice guide: Indigenous peoples and mining. ICMM.

- International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM). (2009a). Handling and resolving local level concerns and grievances. ICMM.

- International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM). (2009b). Human rights in the mining and metals industry: Overview, management approach and issues. ICMM.

- International Finance Corporation (IFC). (2012). Performance standards on environmental and social sustainability. World Bank Group.

- International Finance Corporation (IFC). (2006). Performance standards on environmental and social sustainability. World Bank Group.

- International Labour Organization (ILO). (1989). C169 – Indigenous and tribal peoples convention 1989: Convention concerning indigenous and tribal peoples in independent countries. ILO.

- Jaskoski, M. (2014). Environmental licensing and conflict in Peru’s mining sector: A path-dependent analysis. World Development, 64, 873–883. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.07.010

- Junqueira, D. (2022). Camponeses e indígenas ocupam área de reforma agrária cedida para mineradora Belo Sun. Reporter Brasil, June 9. https://reporterbrasil.org.br/2022/06/camponenses-e-indigenas-ocupam-area-de-reforma-agraria-cedida-mara-mineradora-belo-sun/

- Caine, K. J., & Krogman, N. (2010). Powerful or just plain power-full? A power analysis of impact and benefits agreements in Canada’s North. Organization & Environment, 23(1), 76–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086026609358969

- Krasner, S. (1982). Structural causes and regime consequences: Regimes as intervening variables. International Organization, 36(2), 185–205. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818300018920