ABSTRACT

Feedback information can be a powerful influence on learning, yet there is currently insufficient understanding of the cognitive mechanisms responsible for these effects. In this exploratory study, students (N = 279) received teacher feedback on a practice exam paper, and a few days later we assessed the amount and type of feedback information they successfully remembered. Overall, students performed relatively poorly, recalling on average just 25% of the coded feedback comments they had received. We found that students were more likely to remember critique comments over praise, and more likely to recall critique that was process-focused rather than task-focused. In contrast with recent laboratory studies, though, we found minimal evidence of a memory advantage for evaluative critique over directive critique. We call for greater understanding and measurement of learners’ cognitive processing of feedback information, as a means to develop more robust scientific accounts of how and when feedback is impactful.

KEYWORDS:

Educators invest extraordinary time and effort in providing feedback to the learners they teach (Department for Education, Citation2016; Richards & Richardson, Citation2019). This investment, research tells us, is worthwhile because feedback is one of the most powerful drivers of learning (Hattie & Timperley, Citation2007; Kluger & DeNisi, Citation1996). And yet the very same educators regularly see signs of their feedback having no apparent impact, sometimes even being ignored altogether (Brown et al., Citation2016; Gibbs & Simpson, Citation2004; Price et al., Citation2011). Considering both the value and the costs of giving feedback, it is important to study how and when students cognitively process the feedback they receive, so that we might reach a fuller understanding of the mechanisms through which we can realise feedback’s potential (Lui & Andrade, Citation2022; Panadero, Citation2023; Winstone & Nash, Citation2023). In this exploratory study we explored the amount and kinds of feedback information that students received and retained in memory, just a matter of days after receiving this valuable guidance from their teachers. We also conducted analyses to explore the influence of individual differences in students’ memory for feedback.

Whereas the links between feedback and performance are well-established, there is also increasing recognition that the task of translating teachers’ advice into better skills or grades requires significant cognitive processing on the student’s part (Lui & Andrade, Citation2022). This processing takes numerous forms, which we might consider as the cognitive mechanisms via which the benefits of feedback are realised. For instance, feedback receivers must attend to and encode feedback information, must cognitively appraise the information as accurate, unbiased, and worthwhile, must set short- or long-term goals for implementing the suggestions, and must be able to recognise the relevance of the advice at a later time when the opportunity arises to use it directly (see Winstone & Nash, Citation2023 for detailed discussion). Among these mechanisms and processes, memory for feedback information is especially important because the literature provides countless examples of students reading their teachers’ feedback once and then failing to revisit it in the future (e.g. Nash & Winstone, Citation2017; Robinson et al., Citation2013). Thus, in order for feedback to serve its formative function in directing students’ learning and supporting their future performance, it must often be remembered (Osterbur et al., Citation2015).

The simplest question we might ask about students’ memory for feedback information is how much is remembered overall. Some research indicates that in general, students’ recall of feedback information is poor (e.g. Buckley, Citation2012; Butler & Roediger, Citation2008). In one small study, Elfering et al. (Citation2012) explored how much 43 Masters students remembered from their supervisor’s verbal feedback after giving oral presentations of their thesis proposals. A recording clerk took notes of the feedback given, and students were asked to email their supervisor later that day with everything they could remember from the feedback, which was then compared with the clerk’s notes. On average, despite the relatively short retention interval, the students recalled only 56% of the feedback information they had received. Other research suggests that learners’ memory for feedback is considerably poorer when their grades are included alongside those comments (Butler, Citation1987); indeed, having foreknowledge of grades can discourage students from reading their written feedback at all (Kuepper-Tetzel & Gardner, Citation2021; Mensink & King, Citation2020).

Beyond the absolute amount of feedback remembered, a more nuanced question that we might ask is whether students are likely to remember certain types of feedback more than others. For example, a simple distinction can be drawn between feedback comments that serve as praise, and those that serve instead as critique. In social psychological studies that explore people’s recall of self-referential feedback, people commonly demonstrate a ‘mnemic neglect effect’, selectively forgetting self-threatening, critical personality feedback more readily than they forget self-affirming, positive feedback (e.g. Sedikides, et al., Citation2016). This effect might lead us to expect superior memory for praise over critical feedback comments, and indeed there is recent evidence that people remember ‘success’ feedback more readily than equally informative ‘failure’ feedback (Eskreis-Winkler & Fishbach, Citation2019). Yet other research in learning contexts suggests the opposite, finding that people demonstrate superior memory for error feedback over feedback indicating correct performance (e.g. Van der Borght, et al., Citation2015). One potential explanation is that errors can be surprising, leading to greater focus on the information conveyed by the feedback in this case (e.g. Fazio & Marsh, Citation2009). Further evidence of a memory advantage for critique over praise comes from a study by Cutumisu and Schwartz (Citation2018), in which 13- to 14-year-old students designed posters in a digital environment. Students could choose to receive critical (i.e. negative) or confirmatory (i.e. positive) feedback on their poster, and could then choose whether or not to revise their poster in light of the feedback. After receiving feedback comments, students completed an unexpected memory test in which they attempted to reconstruct as much as they could remember from the feedback on their poster. Participants’ memory for critical feedback was superior to that for confirmatory feedback. In short, psychological theory and empirical studies give us contrasting predictions over whether praise or critique would be recalled best in a naturalistic context.

We might also expect that memory for critique would depend on what kind of critique is given. In a recent programme of experimental research, Nash and colleagues found that people who received ostensibly personalised critique – and indeed, people who read critique that belonged to another student – were consistently better at remembering those comments expressed using past-oriented, evaluative wording, in contrast with similar comments expressed using future-oriented, directive wording (Gregory et al. Citation2020; Nash et al., Citation2018, Citation2021). This so-called ‘evaluative recall bias’ seems at odds with research in the field of education – and with received wisdom in popular culture – from which educators are routinely advised that future-oriented feedback is superior (e.g. Hirsch, Citation2017; Sadler et al., Citation2023). To date though, none of these laboratory studies have provided clear evidence of the cognitive mechanism that causes the bias. Gregory et al. (Citation2020), for instance, found no difference in participants’ visual attention towards evaluative vs. directive comments during reading. Likewise, Nash et al. (Citation2021) hypothesised that people remembered evaluative and directive feedback comparably, but are selectively more likely to report evaluative information. But their data offered no support for this interpretation of the memory bias, either. In short, the evaluative recall bias has proven highly replicable in controlled laboratory studies, but it remains unclear – especially in the absence of understanding the cognitive mechanism(s) at play – to what extent the same bias would arise naturalistically in real classrooms. In the prior experimental studies, the exact same feedback comments were given to all participants, and indeed, there was relatively little for participants to gain from studying the comments closely. There is therefore a need to explore these memory effects in more ecologically-valid settings, wherein genuine feedback is provided by genuine teachers, and where attending to and applying the feedback has high stakes for learners.

There are, of course, many other ways in which we might codify different critique comments, beyond whether they are evaluative or directive in focus. Another common distinction in educational research considers the type of information provided to learners, by contrasting task-level feedback with process-level feedback (Hattie & Timperley, Citation2007). In this context, task-level feedback focuses on the specific piece of work the student has completed, including information concerning their understanding and the accuracy of their responses. In contrast, process-level feedback provides information on the effectiveness or appropriateness of the strategies the student has used (or should use) to complete the task. Understanding the ways in which feedback comments are most commonly framed is important; several studies have indicated that teachers provide task-level feedback information more frequently than process-level feedback (Brooks et al., Citation2019; Hattie & Timperley, Citation2007; Máñez et al., Citation2024), yet process-level feedback is believed to be more effective than task-level feedback in promoting attainment and deep learning (Hattie & Clarke, Citation2019; Hattie, Citation2021), and more generalisable to future work (Hattie & Timperley, Citation2007).

To our knowledge, no studies have examined students’ relative likelihood of remembering task- vs. process-level feedback, but in principle one might predict that process feedback would be better remembered. For example, process feedback is considered more relevant than task-feedback to how learners approach subsequent tasks, and psychological research shows that people tend to show superior memory for information if they believe they will be need to act upon it at a later time (Chasteen et al., Citation2001; Goschke & Kuhl, Citation1993; McDaniel et al., Citation2008). However, it is interesting to note that this same line of reasoning had led Nash et al. (Citation2018) to predict – incorrectly – that directive, future-oriented feedback comments would be recalled better than evaluative, past-oriented feedback (i.e. they had predicted a directive recall bias). Insofar that process-level feedback has conceptual similarities to directive feedback – whereas task-level feedback is conceptually similar to evaluative feedback – Nash et al.'s work might therefore lead us to predict that task-level feedback would be recalled best (Gregory et al., Citation2020; Nash et al., Citation2018, Citation2021).

Finally, it is also important to acknowledge that myriad individual differences could moderate students’ tendency to remember feedback information. In particular, students’ various beliefs about or conceptions of feedback have been shown to correlate with the extent to which they engage with feedback information (Han, Citation2017; Winstone et al., Citation2021), yet to our knowledge none of the few past studies that explored memory for feedback have also explored individual differences of this sort. In the present study we therefore gathered exploratory data using a small number of potentially relevant individual difference measures, to look for evidence of systematic variability in feedback memory between students.

The present study

The present study served to address two main aims. First, we sought to replicate Cutumisu and Schwartz’s (Citation2018) finding that critique is recalled better than praise. Second, we sought to extend the scope of prior research on memory for critique, both by examining whether the evaluative recall bias could be replicated in a real-world, high-stakes feedback context, and by examining the relative recall of task- vs. process-level critique. To address these main aims, we undertook a field study in which learners received feedback from their teachers after completing a practice exam, and we then tested students’ subsequent memories for this feedback after a few days’ delay. In addition to these two main aims, we gathered exploratory individual difference data from the students, as well as their assessment grades, and we evaluated the extent to which these measures were associated with their recollection of feedback.

Method

Participants

A total of 279 students from two post-compulsory education colleges in the South East of England (64% identified as female; 35% as male; 1% opted not to disclose their gender) completed the study in full. Students were aged between 16 and 19 (Mage = 17.0, SDage = 0.6). Individual students participated within just one of the courses they were studying, and a range of subjects were represented: psychology, sociology, biology, classic civilisation, geography, music technology, philosophy, religious studies, and Spanish. Ethical approval was granted by an institutional review board (University of Surrey, ref: UEC2018097DHE), and as all participants were aged 16 or over, they gave informed consent themselves. Each participating college received a financial donation towards their purchase of educational resources; individual students were not compensated.

Materials and procedure

As part of their routine educational activity, participants completed a benchmark assessment in their subject during class time. The benchmark assessment is a formal, practice examination paper undertaken once per term under controlled conditions, designed to establish students’ progress towards objectives and prepare them for final, summative assessments. As a formative task, the benchmark assessment did not count towards students’ final course grades. These examinations varied in style and content between subject areas, were normally 60–80 minutes in duration, and were completed per the college’s and subject area’s usual practices. After completion of the benchmark assessment, teachers marked their students’ papers and prepared written feedback comments in their usual way. Next, a research assistant visited the college to photocopy each student’s exam script (including the teacher’s feedback comments), and they recorded the percentage grade that the teacher had assigned to each student. Marked exam papers with feedback comments were returned to students in their subsequent lessons 2–3 days later, again in accordance with ‘business as usual’. Teachers provided informed consent for their feedback to be used for the purposes of the study.

In the next lesson after the feedback had been returned, another 2–3 days later, the research assistant visited the classroom and provided information about the study. Students were asked for individual consent to participate, and for us to use their benchmark assessments and feedback as part of our data collection. Our plan was to delete the photocopied benchmark assessment data for any students who declined to take part, and for those who were absent from class on the day of testing; however, in practice all students consented to take part and so we only deleted the benchmark data for absent students. All participants then completed a questionnaire packet during their lesson time. Specifically, they were first asked to provide basic demographic information, and then given the following instructions:

We would like you to think back to the feedback you recently received on your [benchmark] assessment. In the box below, please write, in as much detail as possible, everything you can remember from that feedback. We obviously don’t expect that you’ll be able to remember it word-for-word. Nevertheless, try to be as accurate as possible about the general meaning of what was written. Try to reconstruct your feedback so that if another person read your description, they would understand what feedback you were given. You will have 10 minutes to complete this task.

Information avoidance scale

The Information Avoidance Scale (Howell & Shepperd, Citation2016) is an 8-item measure scored on 6-point Likert scales, which assesses people’s tendency to avoid learning information about themselves, for example ‘I would rather not know what teachers think about my written work’. This measure is potentially important as people’s reported tendency to avoid information has been demonstrated to predict, for example, people’s decisions to receive (or not receive) health information feedback (e.g. Taber et al., Citation2015), albeit similar relationships have not yet been demonstrated in educational contexts. In our sample, this scale had good internal consistency (α = .80).

Consideration of future consequences

The Consideration of Future Consequences Scale (Petrocelli, Citation2003) is a 12-item measure scored on 5-point Likert scales, assessing whether individuals tend to predominantly consider the immediate or the more distal consequences of their actions, for example ‘Often I engage in a particular behaviour in order to achieve outcomes that may not result for many years’. In our sample, this scale had good internal consistency (α = .82).

Conception of feedback

The full Student Conception of Feedback Scale (Irving & Peterson, Citation2006) is a 42-item measure scored on a 6-point Likert scales, assessing students’ beliefs and behaviours in the context of assessment feedback. We used two subscales that characterise learners’ engagement with feedback: students’ active use of feedback (7 items; e.g. ‘I actively use feedback to help me improve’), and the extent to which feedback is ignored (5 items; e.g. ‘I ignore bad grades or comments’). The latter subscale seemed especially pertinent to our aims. In our sample, the ‘active use of feedback’ subscale had good internal consistency (α = .86), but Cronbach’s alpha was less-than-optimal for the ‘ignore feedback’ subscale (α = .59). To contain the length of the survey, we chose only those subscales that were most pertinent to the study’s aims and context, excluding subscales (e.g., the value of feedback from peers) that did not relate to the context of the benchmark assessment.

After completing the questionnaire packet, students’ classes were debriefed and had the opportunity to ask questions about the study’s aims.

Data coding

A research assistant transcribed every substantive feedback comment that teachers had written on examination scripts. We included only those comments which would retain meaning when removed from the context of the student’s written work, thus excluding all non-verbal feedback (e.g. underlining; checkmarks; lone question marks; the word ‘Yes’) and specific corrections of spelling or grammar. Separately, the research assistant transcribed each student’s free recall of the feedback comments they received.

Both authors parsed the teachers’ feedback into meaningful units or comments. For example, the following feedback was parsed into three codable units, as indicated by the oblique marks ‘The essay is a bit narrow//- needs to look at more subcultural theorists//and compare similarities and differences to [Theory X]’. A single coder, blind to the study’s aims, then coded every parsed comment as either (1) praise, (2) critique, or (3) other comments. For those comments coded as critique, the coder also attempted to classify the critique along two further dimensions. First, they judged whether the critique was evaluative, that is, pertaining to how the assessment had been completed (e.g. The way it is currently written could mean you only get 2 marks), or whether it was directive, that is, advising students on how they might improve next time (e.g. Make a clear outline of the differences as well). Second, they judged whether the critique was task-focused, that is, pertaining to the specific exam paper that had been completed or to the exam questions or topics themselves (e.g. Review evaluation points for labelling theory); or whether it was process-focused, that is, pertaining to the general processes used when undertaking these kinds of task (e.g. Include evidence from specific studies to support discussion in 10 mark questions).

Finally, the same coder compared each participant’s free recall text against the list of parsed comments their teacher had provided. The coder made a binary judgement of whether or not each of these comments had been recalled, with these judgements based on overall gist rather than requiring any degree of literal matching in wording. To check the reliability of the main coder’s judgements, a second coder examined 200 individual parsed comments (i.e. approximately 18% of the data), and attempted to code each as either praise, critique, or other. The two coders agreed on 99% of these judgements. For all comments that the second coder had classified as critique, they also attempted to code each as evaluative or directive, and as either task-level or process-level. The inter-coder agreement was again very high for cases where the main coder had identified evaluative critique (100%), directive critique (100%), task-level critique (99%), and process-level critique (97%). We also assessed the reliability of the main coder’s gist-based judgement of whether comments had been recalled, by having a second coder examine the recall of 56 participants (20% of the sample) and use the same coding process to decide whether each of the comments these participants received had been recalled. The two coders agreed on 97% of these comment-level judgements (N = 227 comments, Cohen’s kappa = .90). Our analyses below are therefore based solely on the main coder’s judgements.

Results

Feedback given

Before turning to our main aim of assessing students’ recall of their feedback, we first provide a descriptive picture of the feedback they received from their teachers. Participants received between 1 and 15 feedback comments in total (M = 4.08, SD = 2.31, Median = 4). The vast majority of these comments could be categorised as either praise or as critique, but a small proportion (4.1% of the comments given) could not and were instead coded as ‘other’; the majority of these ‘other’ comments were question prompts (e.g. ‘Does it have any flaws?’), some of which might have been considered ‘self-regulation’ feedback within Hattie and Timperley’s (Citation2007) framework. As the first column of data in shows, participants overall received more critique (M = 2.87 comments, SD = 1.79, Median = 2) than praise (M = 1.04, SD = 1.29, Median = 1), Wilcoxon Z = 10.96, p < .001, r = .66.

Table 1. Total number of each type of feedback comment given to participants, summed across the whole sample (N = 279), and the number (and percentage) of these comments that students successfully recalled in the memory test.

Looking solely at the critique that teachers gave, participants received significantly more process-level critique (M = 1.57 comments, SD = 1.44, Median = 1) than task-level critique (M = 1.30, SD = 1.20, Median = 1), Wilcoxon Z = 2.02, p = .04, r = .12. Most but not all of the critique comments could also be coded as either evaluative or directive in style; we found that participants received significantly more directive critique (M = 1.99 comments, SD = 1.55, Median = 2) than evaluative critique (M = 0.70, SD = 0.94, Median = 0), Wilcoxon Z = 9.98, p < .001, r = .60. Note that whereas teachers’ evaluative critique was task-level more often than process-level, χ2 (1, N = 195) = 4.31, p = .04, w = .15, their directive critique was process-level more often than task-level, χ2 (1, N = 554) = 20.28, p < .001, w = .19. That is to say, these two dimensions of coding the critique comments were not statistically independent; for thoroughness, in we therefore report the descriptive data separately for each of the four cells of this 2 × 2 categorising of critique.

Feedback remembered

We now turn to our main focus, namely which of these feedback comments participants successfully recalled in the memory test. As the top row of data in shows, participants recalled only a quarter of the feedback they had received overall, successfully reproducing between 0 and 4 comments (M = 1.03, SD = 1.05, Median = 1).

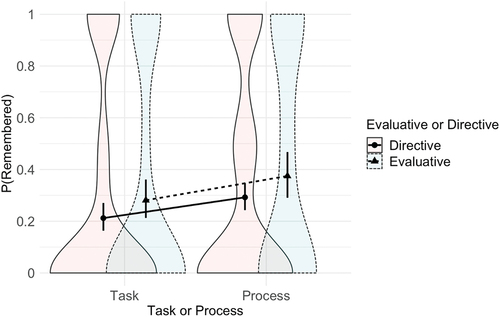

As individual feedback comments were nested within participants; that is to say, the observations were not independent, we used jamovi v.1.6.23.0 to analyse the data using two generalised linear mixed model (GLMM) logistic regressions, each model with random intercepts for participants, and each model predicting individual feedback comment recall (yes vs. no) as the outcome variable (see ). In the first GLMM analysis we entered comment type (praise vs. critique) as the only fixed effects variable, and found that critique was recalled significantly better than praise, b = 0.74, SE = 0.19, z = 3.84, p < .001. In a second model we focused only on memory for the critique comments, and we included evaluative vs. directive, task-level vs. process-level, and their interaction, as fixed effects. This second model showed that process-level critique was recalled better than task-level critique, b = 0.45, SE = 0.20, z = 2.26, p = .02. Evaluative critique was recalled slightly better relative to directive critique, but this difference was not statistically significant, b = 0.37, SE = 0.20, z = 1.89, p = .06, albeit the regression coefficient for this effect was similar to the coefficient for the comparison of task and process critique. The interaction effect was not significant, b = 0.09, SE = 0.39, z = 0.22, p = .83.

Figure 1. Violin plot illustrating the proportion of critique comments recalled by participants, as a function of whether the comments were task- or process-level, and whether they were evaluative or directive in focus. The data are based on a GLMM with participants treated as a random factor; error bars represent 95% confidence intervals from this model.

When we added students’ achieved grades plus our four individual difference variables (i.e. information avoidance, consideration of future consequences, ignore feedback, and active use of feedback) as simultaneous covariates in each of the two GLMMs described above, none of these additional variables were significant overall predictors of recall in either model (all zs <1.7. all ps > .10). Furthermore, adding these five variables did not change the conclusions described above, with the exception that in the critique model, the slightly greater recall of evaluative critique over directive critique was statistically significant, b = 0.40, SE = 0.21, z = 2.01, p = .04.

Additional findings concerning individual differences

Although not relevant to our main research questions, we also looked for systematic individual differences in the kinds of feedback students received and remembered. Participants’ grades in their assessed pieces of work ranged from 14% to 100% (M = 54.9%, SD = 17.4%, Median = 55%; two participants’ grades were missing). Participants with higher grades received fewer feedback comments in total, rspearman (275) = −.16, p < .01. Specifically, these participants received less critique, rs (275) = −.19, p < .01—especially evaluative critique, rs (275) = −.33, p < .001, and process-level critique, rs (275) = −.13, p = .03, although the patterns were similar for directive critique, rs (275) = −.12, p = .053, and task-level critique, rs (275) = −.10, p = .10—but they tended to receive slightly (but not significantly) more praise, rs (275) = .10, p = .11.

Participants who achieved higher grades also tended to score more highly on Active Use of Feedback, rs (275) = .15, p = .01, and Consideration of Future Consequences, rs (275) = .17, p < .01, and scored lower on Information Avoidance, rs (275) = −.12, p = .047, and Ignore Feedback, rs (275) = −.12, p = .052. Looking at these other individual difference measures, we found no statistically significant associations with any measure of either feedback received, or feedback recalled, with the sole exception that – counterintuitively – participants with higher Ignore Feedback scores tended to recall significantly more of the feedback they received, rs (277) = .13, p = .03. It is important to keep in mind that all of the significant correlations described here are very modest in size, that the Ignore Feedback measure had poor internal reliability in this sample, and that there is a considerable likelihood of false positives given the number of exploratory correlations tested.

Discussion

Feedback information can be an invaluable learning aid, yet its effectiveness in many cases hinges on whether or not the learner can subsequently remember it. In the present study, less than one week after receiving important feedback from their teachers, our participants were able to successfully reproduce only one quarter of the information they had been given. Yet we found that this recall rate differed statistically between different kinds of feedback. Specifically, the students in this study were especially unlikely to recall praise as compared with critique, and were most likely to remember critique when it was process-focused rather than task-focused. We deal with each of these findings in turn.

In demonstrating a memory advantage for critique over praise, our data align with the previous findings of Cutumisu and Schwartz (Citation2018), and thus add to growing evidence that so-called mnemic neglect’—the disproportionate forgetting of critical (self-referential) feedback (Sedikides et al., Citation2016)—is not a domain-general characteristic of how people recall feedback. In learning contexts it is clearly advantageous for learners to remember critical comments readily: whereas praise can provide a confidence boost and serve a motivational function, critique typically provides more information that could inform future improvement. That said, both here and when considering the other findings from the present study, we should be careful to consider a distinction between which feedback students reproduced in the memory test, and which they could remember per se. When students failed to recall certain feedback comments in this study, this might mean that those comments were forgotten, or it might reflect the retrieval or reporting strategies used. Students may, for instance, have believed it irrelevant to mention the praise they received, despite remembering it perfectly. Alternatively, praise may have been available less readily in students memories yet still cognitively accessible, in principle, with sufficient effort or cueing. These are important theoretical questions for future study. But irrespective of the causal mechanism, our present data do point towards a tendency – explicit or implicit – for students to treat praise as less relevant or worthy of consideration relative to critique.

The second dimension of feedback we explored in this study was to look for differences in memory between different types of critique. Specifically, we asked to what extent process-level critique would be recalled better than task-level critique; we also assessed the extent to which the ‘evaluative recall bias’ – that is, people’s tendency to recall evaluative feedback better than directive feedback – would replicate in this naturalistic dataset, given that the bias has heretofore only been tested in controlled experimental studies. Here, our data demonstrate that learners were indeed more likely to remember critique that focused at the process level rather than the task level. Whereas task-level comments can have immediate utility in correcting misunderstandings or clarifying understanding of the subject of the task, such comments typically have limited transfer to other future tasks, whereas in contrast, comments at the process level may possess greater utility in supporting future learning tasks. Hence, it may be more advantageous for learners to remember process critique. Hattie and Timperley (Citation2007, p. 91) argued that ‘ … too much feedback only at the task level may encourage students to focus on the immediate goal and not the strategies to attain the goal’ (Hattie & Timperley, Citation2007, p. 91), but our data hint that students might often respond to task-level feedback not by changing their goal or strategies, but instead by devoting less cognitive processing towards the feedback itself.

In terms of the evaluative recall bias, our data provide only weak evidence: evaluative comments were indeed recalled at a higher rate than directive comments, but this difference was not statistically significant in our primary analysis. Further naturalistic studies will therefore be needed to determine more conclusively to what extent the evaluative recall bias occurs outside the lab, nevertheless the present data do align with the experimental data in disconfirming the common expectation that learners treat directive feedback as more important or worthy of attention than evaluative feedback (Nash et al., Citation2018).

Despite this initial evidence that students’ feedback memory can depend on the type of feedback given, we caution teaching practitioners against resolving uncritically to give those poorly-recalled kinds of feedback comment less frequently. Indeed, the effects seen in this exploratory study were relatively small, and arguably the most striking feature of our data was that memory was poor for all kinds of feedback information. Our data cannot speak to the potential learning value of the different types of feedback comment had they been remembered and applied; one cannot rule out the possibility that task-focused critique, for example, would be more valuable than process-focused critique if teachers could only guarantee it due attention from students. To improve students’ retention (and in turn their application) of feedback information, it is important to scaffold their opportunities to process that information in depth, and consider in concrete terms how they can apply it to future work. Our findings indicate that sole reliance on students reading written feedback information as a mechanism for impact is unlikely to be effective. The practice of Dedicated Improvement and Reflection Time (or ‘DIRT’) is growing in many schools, where students are supported to engage with and implement feedback—and sometimes adjust their work accordingly—during routine classroom activities (Winstone & Winstone, Citation2021). In light of our findings, approaches such as DIRT might be valuable for supporting the kinds of deeper engagement with feedback that lead to stronger retention and application of the information.

Limitations and future research directions

The present study represents an important extension of lab-based research into memory for feedback to real-world learning contexts. However, as an exploratory field study, many elements of the feedback process were not under our control in this study and these limit the conclusions that can be drawn. Notably, there was considerable diversity in the feedback comments that teachers provided: some annotated the work with single comments, some appeared to have a pre-prepared bank of comments which they applied to the work of different students, and some gave personalised and elaborative comments. This feature of the dataset is an advantage insofar that it allowed us to model real-world diversity in feedback comments, yet it does mean that all students were not afforded equivalent opportunities to receive and to remember detailed advice. Furthermore, without full experimental control, we cannot determine whether superior memory for some types of feedback over others stems from those types of comments being inherently easier to remember, or from some other feature of the comments such as their linguistic style or concreteness.

One further limitation of the present work, and of most related experimental studies, is that by focusing solely on the simple recall of feedback comments, we did not consider behavioural outcomes, that is, which types of comments learners were more likely to enact when undertaking future tasks. Doing so would be an important next step in understanding the role of memory as a key mechanism in the feedback process. Future work might ideally combine our naturalistic approaches with experimental methods that afford greater control and causal inference, for example by rewriting teachers’ feedback comments in a particular way (e.g. as either evaluative or directive) before they are received by students.

Conclusion

Students’ perception of and response to their teachers’ feedback is critical because ‘while feedback may generate learning effects, these may not be automatically translated into better performance on future assessments’ (Brown et al., Citation2016, p. 608). The successful impact of feedback on students’ subsequent performance is most likely to occur when students internalise (e.g. remember) their feedback. This point aligns with an emerging paradigm shift in the literature on assessment and feedback, away from focusing on the one-way transmission of feedback from educator to student, and towards a dialogic model (e.g. Carless, Citation2015). Our data demonstrate that whereas students’ overall recall for feedback comments was weak, there were systematic differences in the types of comments that learners were likely to remember, with critique remembered better than praise, and process-level critique remembered better than task-level critique. Understanding the role of memory in the processing of feedback is an important step towards the broader goal of understanding the psychological mechanisms through which feedback delivers benefits to learners (Winstone & Nash, Citation2023).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Naomi E. Winstone

Naomi E. Winstone is Professor of Educational Psychology and Director of the Surrey Institute of Education at the University of Surrey, UK. As a cognitive psychologist, Naomi’s research focuses on the processing and impact of instructional feedback and the influence of dominant discourses of assessment and feedback in policy and practice on the positioning of educators and students in feedback processes. Naomi is a Principal Fellow of the Higher Education Academy and a UK National Teaching Fellow.

Robert A. Nash

Robert A. Nash is a Reader in Psychology at Aston University in Birmingham, UK. He completed his BSc and PhD degrees in Psychology at the University of Warwick, and he is a Senior Fellow of the Higher Education Academy. His main areas of expertise are applied cognitive psychology, and the pedagogy and psychology of learners’ (and people’s) engagement with feedback.

References

- Brooks, C., Carroll, A., Gillies, R. M., & Hattie, J. (2019). A matrix of feedback for learning. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 44(4), 14–32. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2018v44n4.2

- Brown, G. T., Peterson, E. R., & Yao, E. S. (2016). Student conceptions of feedback: Impact on self‐regulation, self‐efficacy, and academic achievement. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 86(4), 606–629. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12126

- Buckley, P. (2012). Can the effectiveness of different forms of feedback be measured? Retention and student preference for written and verbal feedback in level 4 bioscience students. Journal of Biological Education, 46(4), 242–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/00219266.2012.702676

- Butler, R. (1987). Task-involving and ego-involving properties of evaluation: Effects of different feedback conditions on motivational perceptions, interest, and performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 79(4), 474. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.79.4.474

- Butler, A. C., & Roediger, H. L. (2008). Feedback enhances the positive effects and reduces the negative effects of multiple-choice testing. Memory & Cognition, 36(3), 604–616.

- Carless, D. (2015). Excellence in University assessment. Routledge.

- Chasteen, A. L., Park, D. C., & Schwarz, N. (2001). Implementation intentions and facilitation of prospective memory. Psychological science, 12(6), 457–461.

- Cutumisu, M., & Schwartz, D. L. (2018). The impact of critical feedback choice on students’ revision, performance, learning, and memory. Computers in Human Behavior, 78, 351–367.

- Department for Education. (2016). Eliminating unnecessary workload around marking: Report of the independent workload review group. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/511256/Eliminating-unnecessary-workload-around-marking.pdf

- Elfering, A., Grebner, S., & Wehr, S. (2012). Loss of feedback information given during oral presentations. Psychology Learning & Teaching, 11(1), 66–76. https://doi.org/10.2304/plat.2012.11.1.66

- Eskreis-Winkler, L., & Fishbach, A. (2019). Not learning from failure—the greatest failure of all. Psychological Science, 30(12), 1733–1744.

- Fazio, L. K., & Marsh, E. J. (2009). Surprising feedback improves later memory. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 16(1), 88–92.

- Gibbs, G., & Simpson, C. (2004). Conditions under which assessment supports students’ learning. Learning and Teaching in Higher Education, 1, 3–31.

- Goschke, T., & Kuhl, J. (1993). Representation of intentions: Persisting activation in memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory & Cognition, 19(5), 1211–1226.

- Gregory, S.E.A., Winstone, N.E., Ridout, N., & Nash, R.A. (2020). Weak memory for future-oriented feedback: Investigating the roles of attention and improvement focus. Memory, 28(2), 216–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2019.1709507

- Han, Y. (2017). Mediating and being mediated: Learner beliefs and learner engagement with written corrective feedback. System, 69, 133–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2017.07.003

- Hattie, J., & Clarke, S. (2019). Visible learning: Feedback. Routledge.

- Hattie, J., Crivelli, J., Van Gompel, K., West-Smith, P., & Wike, K. (2021). Feedback that leads to improvement in student essays: Testing the hypothesis that “where to next” feedback is most powerful. Frontiers in Education, 6, 645758.

- Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487

- Hirsch, J. (2017). The feedback fix: Dump the past, embrace the future, and lead the way to change. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Howell, J. L., & Shepperd, J. A. (2016). Establishing an information avoidance scale. Psychological Assessment, 28(12), 1695–1708. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000315

- Irving, S. E., & Peterson, E. R. (2006). Conceptions of Feedback (CoF) inventory (Version 2). University of Auckland.

- Kluger, A. N., & DeNisi, A. (1996). The effects of feedback interventions on performance: A historical review, a meta-analysis, and a preliminary feedback intervention theory. Psychological Bulletin, 119(2), 254–284.

- Kuepper-Tetzel, C. E., & Gardner, P. L. (2021). Effects of temporary mark withholding on academic performance. Psychology Learning & Teaching, 20(3), 405–419. https://doi.org/10.1177/1475725721999958

- Lipnevich, A. A., Lopera-Oquendo, C., & Cerdán, R. (2024). Examining pre-service teachers’ feedback on low-and high-quality written assignments. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 36(2), 225–256.

- Lui, A. M., & Andrade, H. L. (2022). The next black box of formative assessment: A model of the internal mechanisms of feedback processing. Frontiers in Education, 7, 751548. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.751548

- McDaniel, M. A., Howard, D. C., & Butler, K. M. (2008). Implementation intentions facilitate prospective memory under high attention demands. Memory & Cognition, 36, 716–724.

- Mensink, P. J., & King, K. (2020). Student access of online feedback is modified by the availability of assessment marks, gender and academic performance. British Journal of Educational Technology, 51(1), 10–22.

- Nash, R. A., & Winstone, N. E. (2017). Responsibility-sharing in the giving and receiving of assessment feedback. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1519.

- Nash, R. A., Winstone, N. E., & Gregory, S. E. (2021). Selective memory searching does not explain the poor recall of future-oriented feedback. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 10(3), 467–478.

- Nash, R. A., Winstone, N. E., Gregory, S. E. A., & Papps, E. (2018). A memory advantage for past-oriented over future-oriented performance feedback. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 44(12), 1864–1879. https://doi.org/10.1037/xlm0000549

- Osterbur, M. E., Hammer, E. Y., & Hammer, E. (2015). Does mechanism matter? Student recall of electronic versus handwritten feedback. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching & Learning, 9, 7.

- Panadero, E. (2023). Toward a paradigm shift in feedback research: Five further steps influenced by self-regulated learning theory. Educational Psychologist, 58(3), 193–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2023.2223642

- Petrocelli, J. V. (2003). Factor validation of the consideration of future consequences scale: Evidence for a short version. The Journal of Social Psychology, 143(4), 405–413. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224540309598453

- Price, M., Handley, K., & Millar, J. (2011). Feedback: Focusing attention on engagement. Studies in Higher Education, 36(8), 879–896.

- Richards, G., & Richardson, R. (Eds.). (2019). Reducing teachers’ marking workload and developing pupils’ learning. Routledge.

- Robinson, S., Pope, D., & Holyoak, L. (2013). Can we meet their expectations? Experiences and perceptions of feedback in first year undergraduate students. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 38(3), 260–272.

- Sadler, I., Reimann, N., & Sambell, K. (2023). Feedforward practices: A systematic review of the literature. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 48(3), 305–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2022.2073434

- Sedikides, C., Green, J. D., Saunders, J., Skowronski, J. J., & Zengel, B. (2016). Mnemic neglect: Selective amnesia of one’s faults. European Review of Social Psychology, 27(1), 1–62.

- Taber, J. M., Klein, W. M., Ferrer, R. A., Lewis, K. L., Harris, P. R., Shepperd, J. A., & Biesecker, L. G. (2015). Information avoidance tendencies, threat management resources, and interest in genetic sequencing feedback. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 49(4), 616–621.

- Van der Borght, L., Schouppe, N., & Notebaert, W. (2016). Improved memory for error feedback. Psychological Research, 80, 1049–1058.

- Winstone, N. E., Hepper, E. G., & Nash, R. A. (2021). Individual differences in self-reported use of assessment feedback: The mediating role of feedback beliefs. Educational Psychology, 41(7), 844–862.

- Winstone, N. E., & Nash, R. A. (2023). Toward a cohesive psychological science of effective feedback. Educational Psychologist, 58(3), 111–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2023.2224444

- Winstone, N. E., & Winstone, N. (2021). Harnessing the learning potential of feedback: Dedicated Improvement and Reflection Time (DIRT) in classroom practice. In Y. Zi and Y. Lan (Eds.), Assessment as learning: Maximising opportunities for student learning and achievement (pp. 206–216). Routledge.