ABSTRACT

This paper contributes to art marketing and consumption literature by studying how art market participants from Brazil – a market considered “emergent” – position themselves in the global art market. Drawing on qualitative interviews with 60 art market participants and participant observation in Sao Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, the paper shows how position and validation gains are understood as entailing practices of (ex)change (or troca in Portuguese) at the individual and field level. Beyond the extension of their social networks and circulation in art market circuits outside Brazil, art market participants understood their positioning gains as dependent on changes to (the perceptions of) art market practices and operating context, and the negotiation of alternative valuations of Brazilian contemporary art in the global art market, addressing power inequalities.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the global art market has been characterized by a heightened commercial and aesthetic interest in art from “emerging art markets,” translating in a rising share in global market transactions involving contemporary art from countries such as Brazil, China, India and Russia (McAndrew Citation2012; Robertson Citation2011; Kraeussl and Logher Citation2010; Velthuis and Baia Curioni Citation2015). The notion of emergence is not without contestation: it is symptomatic of persisting wider inequalities and hierarchies in the cultural industries, as Europe and North America top the ranks of symbolically and commercially consecrated art market participants (Hesmondhalgh Citation2012; Quemin Citation2013; Velthuis and Baia Curioni Citation2015; see also Sidaway and Pryke Citation2000). Moreover, in the case of Brazil, the notion of such a recent “emergence” is at odds with the longer standing history of the Brazilian contemporary art market, with roots going back to the Post-War (Durand Citation1989; see also Joy and Sherry Citation2004; Kharchenkova Citation2018; Brandellero Citation2015). This paper, therefore, sets out to address questions of growing interest in marketing and consumption studies, notably how art market participants position themselves and extend their market in an international setting (Rodner and Thomson Citation2013; Preece, Kerrigan, and O’Reilly Citation2016; Rodner and Preece Citation2016; see also Parmentier, Fischer, and Reuber Citation2013). Globalization, defined as the multiplication and intensification of flows and exchanges of people and goods in the market for contemporary art, has meant that – just like other fields of cultural production – the boundaries between local and global art fields have blurred (Crane Citation2002; Janssen, Kuipers, and Verboord Citation2008; Kuipers Citation2011). Structures of roles and logics which are internal to the local contemporary art market are tied up in a web of interdependent relations to other geographically proximate and more distant fields (see Fligstein and McAdam Citation2011). Therefore, it is interesting to explore how, when striving for positioning in a global market, art market participants become embedded in practices, social relations and art worlds of varying geographical scope (Bourdieu Citation1977; see Fligstein Citation2001; Fligstein and McAdam Citation2011).

My research question is: how do art market participants from an art market considered emergent experience and enhance their positioning in the global art market? To answer this question, I draw on secondary and interview data, and participant observation research during eight months, involving art gallerists, artists, art curators and collectors based in Sao Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, the two largest centres for the contemporary art market in Brazil. The timing of the research in 2013 captures a phase of expansion of the Brazilian art market, regarding galleries’ revenue and exports of contemporary art marketed by themFootnote1 (ABACT Citation2015). Moreover, it was a time of considerable international attention for Brazil, not least because of the potential nation branding opportunities to be leveraged by its hosting of two sport mega-events: the FIFA World Cup and the Olympic Games (see Knott, Fyall, and Jones Citation2015). I analyse the way art market participants understand the relational, operational and symbolic implications of the growing interconnectedness of the Brazilian contemporary art market, as well as the micro and field level changes that accompany such interconnectedness.

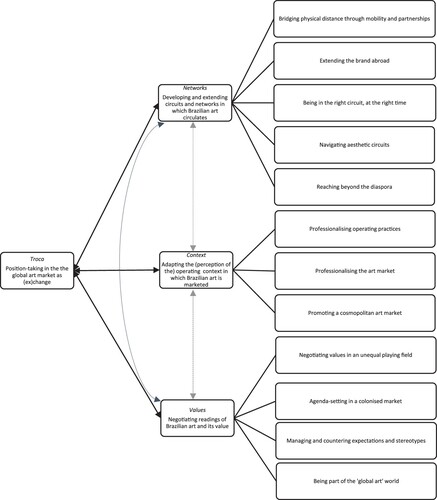

My paper shows how art market participants understand their position-taking validation in the global art market as entailing individual and collective practices of (ex)change on multiple levels – networks, context and values. The notion of troca, a term meaning change and exchange, was often repeated in the field and served to capture this experience. Contributing to studies that have focused on the importance of how art market actors enhance their position and generate value by operating the art machine (Rodner and Thomson Citation2013), this study shows how art market actors experience limitations to their own agency – for example when faced with power disbalances in the global art market – and how they overcome these by engaging in individual and field-level practices of change.

The paper’s contributions can be framed as follows. Firstly, I seek to understand the experience and implications of the positioning of the Brazilian contemporary art market internationally, from the lived experience of participants in an “emerging art market,” contributing to marketing research that explores how emerging market actors navigate the global macro-context in which they circulate (Rodner and Preece Citation2016; see also Buchholz Citation2016). Secondly, this article bridges the gap between two strands of research on art markets: studies that focus on country hierarchies – and centre-periphery inequalities – in the global art field, for example looking at national trends and persisting inequalities in exhibitions, auction results and collections (Buchholz Citation2018; Velthuis and Baia Curioni Citation2015; Quemin Citation2013); and research that zooms into the “material practices and symbolic constructions” of participating institutions (Friedland and Alford Citation1991, 248–249), centred on the lived experience of participants in an art market in ascendance in the global field (see also Joy and Sherry Citation2003; Komarova and Velthuis Citation2018; Sooudi Citation2016). Building on this point, I use my findings to contribute to the understanding of how art markets from a market considered emergent navigate hierarchies in the global art market. Art markets are status markets (Velthuis Citation2007) with specific validation dynamics and institutional “cogs” (Rodner and Thomson Citation2013) supporting value generation and positioning. This paper enhances our understanding of the networked and collaborative nature of value-creation in the art market, attending to global field dynamics and inequalities (Bourdieu Citation1977; Fligstein Citation2001; Velthuis Citation2007; Preece, Kerrigan, and O’Reilly Citation2016).

2. Literature review

2.1. Status and positioning in art markets

To study the positioning of incumbents in the global art market requires acknowledging its peculiarities as a specific type of market. Indeed, a distinction is generally made between markets that stabilize around standards and status (Aspers Citation2009; Friedland and Alford Citation1991, 248). In the former, the standard is an “entrenched social construction,” based on the interaction of producers and consumers and resulting in an objective valuation of the traded objects (Aspers Citation2009, 379). In the latter, quality ranks are co-constituted through the interaction of objects and actors (Aspers Citation2009). Art markets epitomize status markets (Velthuis Citation2007), insofar as the economic and symbolic valuation of artworks is intrinsically linked to the reputation of the actors and intermediaries who trade them, as opposed to inherent in the qualities of the artworks themselves.

Art markets are also characterized by an ecosystem of actors and institutions that collectively contribute to value creation (Becker Citation1982; Preece, Kerrigan, and O’Reilly Citation2016). At the micro-level, agents within the art machine can seek to influence their position by their improving their operational skills (Rodner and Thomson Citation2013). In particular, when positioning themselves in established fields, incumbents need to strike a balance between “standing out” and “fitting in” (Parmentier, Fischer, and Reuber Citation2013). Standing out entails demonstrating one’s unique contribution to a field, for example through one’s track record or portfolio, while also demonstrating knowledge, skills and status-affording affiliations. Fitting in, on the other hand, involves knowing and conforming to the expectations, conventions and tastes of a field (Parmentier, Fischer, and Reuber Citation2013). Moreover, art market incumbents need to reflect on the temporality of their positioning, in other words appreciating that they must also be “at the right place at the right time” (Preece, Kerrigan, and O’Reilly Citation2016, 1383), understanding their position in a market as being contingent to a specific time, place and social arrangement (Beckert Citation2010). Market participants striving for positioning in a market will tend to adjust their mix of resources and capabilities, and therefore networks, to the configuration of that market (Storbacka and Nenonen Citation2011). Yet the knowledge of what mix works can only be gained by participating in the market itself, entailing a certain level of resource investment and risk-taking (Abolafia Citation1998; Aspers Citation2009).

In addition to micro-level considerations, when vying for status gains, participants need to account for the fact that markets develop in a relational way, signalling the contingent nature of their emergence and development (Aspers Citation2009; Bathelt and Glückler Citation2014). Giuffre’s (Citation1999) depiction of the art market as a sandpile where changes in the position of one actor influence the relative standing of others is a particularly poignant metaphor of such relational field. Embeddedness in particular networks affords a “capacity to exercise” power, through the regulation of access to resources or processes of inclusion or exclusion of others (Dicken et al. Citation2001). This is even truer in the case of markets trading commodities of uncertain value (Podolny Citation1990), of which art is an exemplar. As a result, market participants might disembed themselves from institutions or particular social relations in cases when the latter start having a hindering effect (Beckert Citation2009; DiMaggio Citation1988; Leca and Naccache Citation2006). Status in art markets is therefore not fixed or permanent, but it is subject to attempts at its order and hierarchy, in an effort to control the premium afforded to the singularity of products (Callon, Méadel, and Rabeharisoa Citation2002).

2.2. Dynamics of change in a globalizing art market: networks, operational contexts and value hierarchies

The growing international interconnectedness of national art markets brought about by globalization widens the socio-cultural context in which actors operate, opening up new affiliations, relationships and status dynamics through which value co-creation can occur (see Preece, Kerrigan, and O’Reilly Citation2016). Understanding position-taking in the global art market entails accounting for the social capital, operational and symbolic shifts that such opening up engenders.

Firstly, accounting for the operation of the “art machine” (Rodner and Thomson Citation2013) requires the acknowledgement of the socially and spatially complex nature of the actors’ modus operandi, as the circuits in which art circulates become more intricate. The multiplication of art fairs and biennials signals such trend (Velthuis and Baia Curioni Citation2015). Art fairs constitute a significant networking event where valuable information is exchanged on how to position oneself and fit into a market (Yogev and Grund Citation2012); for instance, they offer an arena of observation, price fixing, and study of the competition (Morgner Citation2014a). Their multiplication in recent years is a testimony to the continued relevance of proximity in trust-intensive transactions (Morgner Citation2014a; Yogev and Grund Citation2012), as well as to their role in regulating “entry into symbolically (and sometimes spatially) delimited arenas of association” (Lizardo Citation2012, 305). Art fairs support reputation building, price construction and aesthetic judgement formation in art markets (Joy and Sherry Citation2003; Morgner Citation2014b). Certain arenas are more exclusive than others, as the status premium afforded by access to Art Basel suggests (Fournier and Roy-Valex Citation2002; Morgner Citation2014a; Velthuis Citation2013).

Secondly, research into the impact of globalization on the daily practices and institutions in different national fields points to the emergence of a transnational professional habitus as professionals working across national borders learn and emulate each other’s practices – for example how to run a gallery or to develop an artistic track record (Kuipers Citation2015; Kharchenkova Citation2018; Komarova and Velthuis Citation2018). On a cognitive level, the diffusion of new propositions of shared market understandings can be a powerful tool at the disposal of market actors, potentially causing a shift in market valuations (Storbacka and Nenonen Citation2011; Jensen Citation1996; Wijnberg and Gemser Citation2000; White and White Citation1965). Meanwhile the persisting level of diversity of national institutions suggests the endurance of locally specific norms and practices (Kuipers Citation2015; Velthuis and Baia Curioni Citation2015; Sooudi Citation2015).

Thirdly, we also need to account for how “global transformations affect the structure of hierarchy among countries in realms of cross-border cultural production” (Buchholz Citation2018, 18). The emergence of the notion of contemporary art is seen as encapsulating a transition from the centre-periphery universalizing script of a Westernizing modernity project to a conceptualization of art that contains its own antagonism: contemporary art is at once flux and borderless, yet also plural and embedded in local contexts (Belting Citation2013; Juneja Citation2011). This transition has allegedly chipped away at the art historical “master narrative” perspective and its accompanying aesthetic canon (Belting Citation2013). Yet Crane (Citation2009) notes the rising pertinence of validation tied to performance in art fairs or auctions as well as gravitation towards high profile private collections, often reproducing centre-periphery inequalities. Thus, how participants experience art market emergence offers the possibility to explore potentially contradictory “fitting in” positionings. For instance, that of a “borderless” art worlds where local uniqueness is valued, but also the notion that validation might be moderated by particular centres or events (e.g. art fairs) and be dependent on certain field standards and tastes.

3. Methodology

3.1. Context – art market development in Brazil

Brazil has a long-standing yet somewhat troubled history of cultural and commercial institutions in the field of modern and contemporary art: indeed, the country’s socio-economic and political development and crises were mirrored in sequential phases of art market’s expansion and contraction (Durand Citation1989; Fioravante Citation2001; Morais Citation1996; Brandellero Citation2015). The post-war was characterized by a burgeoning institutional nascence, with the opening of modern art museums in the two largest cities and the inauguration of the world second oldest biennial in São Paulo in 1951 – while auctions and galleries started budding in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, often led by immigrants (Durand Citation1989; Fioravante Citation2001). Morais (Citation1996) recounts the convivial nature of the early art galleries, and details their varied profiles: some were tied to the Arts Academy, others to cultural centres linked to foreign embassies – but many were an assemblage of various services and commodities. Art was discussed and traded alongside antiquities and artistic supplies, as epitomized by the Galeria Montparnasse in Rio. The early years of the dictatorship brought some of these developments to a halt, pushing the art world towards more informal circuits or indeed into exile (Lopes Citation2009). During the 1980s, the art market picked up once more, building on a renewal of artistic creativity, crystallized by Rio’s golden generation – the Geração 80, but also spurred on at the macro-level by the anti-inflationary measures foreseen by Cruzado Plan (Basbaum Citation2013; Fioravante Citation2001; Brandellero Citation2015), as well as the Lei Rouanet, providing fiscal incentives to investments in the arts and culture (Bulhões, Fetter, and Vargas da Rosa Citation2018). Comparably to other emerging economies (Joy and Sherry Citation2003; Komarova and Velthuis Citation2018; Sooudi Citation2015), the growth and stabilization of the art market paralleled the rise of economic elites in Brazil and their quest for identity and status signalling commodities (Bourdieu Citation1984; Veblen Citation[1899] 2007). Institutions were often modelled on European or North American counterparts, suggesting a combination of mimetic and coercive isomorphism – whereby emulating existing practices is at once an efficiency measure for dealing with uncertainty as well as a requirement for gaining access to certain art market circuits (DiMaggio and Powell Citation1991; Komarova and Velthuis Citation2018; Brandellero Citation2015). Market actors share a concern of “low marketness” (Storbacka and Nenonen Citation2011) experienced as the need to enhance the perception of the art market as a valid and stable circuit of value creation. Such concern is notably addressed in terms of incipient relational and institutional structures, unstable value creation dynamics, as well as limited infrastructure for the arts, including museums, education, and art criticism (Fetter Citation2016; Brandellero Citation2020).

One of the perceived barriers to the strengthening of Brazil’s art market is the country’s protectionist taxation system, whereby hefty taxes are imposed on imported goods (Tejo Citation2018). The yearly negotiations of temporary suspensions of part of the import tax during the international art fairs SP Arte in São Paulo and Arte Rio in Rio de Janeiro is perceived as offering a welcome respite and antidote against the insularity of the market (Fialho Citation2019). The fairs have, more generally, been credited with bringing dynamism to the art market. SP Arte for instance attracted 30,000 visitors and 134 exhibitors in 2017 (Skate’s Art Market Research, cited in Tejo Citation2018, 48). Another initiative that has helped enhance the interconnectedness of the Brazilian art market is the Latitude initiative. The Latitude initiative was set up in 2007, financed by the Brazilian government’s foreign trade promotion agency (Apex-Brasil), in partnership with the Association of Brazilian Contemporary Art Galleries (ABACT) which was set up in the same year. Latitude at expanding the market for Brazilian art abroad (see Fetter Citation2016; Fialho Citation2019), by providing subsidies for galleries’ participation in fairs abroad, and supporting networking activities and “art immersion” tours in Brazil, aimed at foreign curators and critics. The tours typically take place before or after one of the art fairs or the Sao Paulo Biennial, and consist of gallery and studio tours, as well as visits to public and private art institutions. Within its framework, several studies on the state of the Brazilian art market have been published as well, covering a variety of organizational and financial matters. Over the years, ABACT has aimed to “professionalise and reduce bureaucracy,” while facilitating “cultural exchanges” in the art market.Footnote2 A private non-profit association, ABACT now counts almost 50 member galleries. It publishes regular sectoral studies on the state of the art market, additionally monitoring the visibility of Brazilian contemporary art abroad (Fialho Citation2019).

3.2. Data collection and analysis

The article is based on qualitative fieldwork in the market for contemporary art in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro over the course of 2013. My selection of 60 contemporary art market participants (including gallerists, artists, curators and collectors – see for an overview) is based on theoretical purpose and relevance (Glaser and Strauss Citation2017). The process of data collection was continuously readjusted and tailored to the theory generative objective of the research, following the grounded theory method (Glaser and Strauss Citation2017). My research centred on participants active in the primary market for contemporary art. The local Arts Map (Mapa das ArtesFootnote3) proved a very handy reference to help me familiarize with the São Paulo contemporary art market. It was a bi-monthly, widely circulated, print-based (now available online) guide, published since 2002, offering information on vernissages, finissages, talks, museum exhibitions, local art fairs preview and general public opening days. Moreover, I took a course on Brazilian contemporary art collecting practices, aimed at local art collectors, and I regularly attended public lectures and debate sessions organized by art institutions and galleries. The recursive nature of some of my visits was dictated by the need to identify and study scripts and practices: this can only be done in a recursive and longitudinal manner, picking up on the “processes of encoding and enacting institutional scripts into action, as well as the processes of replicating, revising, and objectifying these scripts through action” (Bathelt and Glückler Citation2014, 357). The scripts helped me to identify ideal types of institutional logics operating in the Brazilian contemporary art market (see Thornton and Ocasio Citation1999). My selection was based on theoretically relevant criteria: therefore, I chose to include contemporary art market participants with different degrees and length of participation in the local and global art market and different status – drawn from my analysis of the galleries’ histories, artists’ exhibition track record for instance. I interviewed contemporary art gallerists with a high level of participation at international fairs and representing Brazilian “blue chip” artists, present in prestigious international collections (based on prior data collected via Artfacts), but also those with limited or no participation in national or international fairs, representing emerging artists. The gallery ages ranged from one to 39 years, and the majority worked with a range of contemporary art media (painting, sculpture, installations, performance, video, etc.). Artists were selected based on their connection to one of the sampled galleries – either approached independently or based on a suggestion from the art dealer.Footnote4 Their longevity as professional artists varied from three years to five decades since the first gallery exhibition. offers an overview of the respondents. Sampling was based on theoretical saturation, therefore I stopped looking for further respondents once I felt that a category was empirically saturated (Glaser and Strauss Citation2017).

Table 1. Sample composition.

During the interviews with art dealers and artists, which were conducted in Portuguese or English and lasted between 40 min and two hours, I used an interview guide to gauge their experiences of the “opening up” of the Brazilian art market to the global art market (see Kuipers Citation2011), as well as engaging them on a reflection on what participating in an internationalizing art market entails for them and for the Brazilian art market more generally. Art dealers were asked to describe and reflect upon their networks and art fair participation history and future plans, and in so doing, they were prompted to consider the significance of their choices to their position-taking in the local and global art market. Artists and dealers were also asked to reflect on how Brazilian contemporary art was valued in the global art market according to them, and what implications this had on their own work. Moreover, they considered how resource differentials – ranging from track record, financial backing to credibility (see Maguire, Hardy, and Lawrence Citation2004) – shaped their strategies, giving insights into prevailing scripts and logics of action underlying their choices. I also interviewed four art curators, three managers of independent art spaces, and four private art collectors. Interviews were audio recorded, transcribed and coded using Atlas-ti. I created and revised code families relating to understandings, experiences with and motivations for internationalization; experiences with fitting in and standing out in the global art market; and the impact of internationalization on the Brazilian art market and their own position and validation therein. I anonymized quotes in the text using an identifying number.Footnote5

4. Findings

My analysis explicates three ways in which art market participants experience and attempt to enhance their own positioning and validation within the global art field. Specifically, participants understood extending their market as involving the practice of troca, meaning (ex)change. Art market participants expressed engaging in “troca” on three levels: (a) networks, through exchanges and transactions with international counterpart, extending the circuits in which Brazilian art and market participants circulate; (b) context, changing (the perceptions of) the operating context in which Brazilian art is marketed; and finally, (c) values, through the negotiation of alternative readings and values of Brazilian contemporary art (see ). By engaging in these levels of (ex)change, and by virtue of the interactions between these levels of exchange, participants in the Brazilian art market co-constitute “fitting in” and “standing out” practices (Parmentier, Fischer, and Reuber Citation2013), extending the circuits of positioning and validation of Brazilian contemporary art, adapting to emerging field-specific norms, and negotiating aesthetic hierarchies and tastes in the global art market.

4.1. Network (ex)change or troca: developing and extending international networks and circuits

For most respondents, positioning themselves in the global art market required building international connections and networks, linking up to intermediaries in different circuits. This was motivated by the need to overcome an experience of peripherality and physical distance from the global art market, but it was also connected to specific brand building strategies. Extending international networks entailed resource investments and the development of partnerships, as well as reflexivity about market preferences and how particular works would resonate in different circuits.

4.1.1. Bridging physical distance through mobility and partnerships

It’s very difficult to have a project, to have an internationalization strategy when you come from a country like Brazil, that is super peripheral. Large, enormous, but peripheral. When you are in the in the axis Europe, United States […] you are in the middle of a network. It’s cheaper, it’s easier. (8)

Beyond own mobility, partnerships and collaborations were another way to extend the circuits in which Brazilian contemporary art would circulate. Dealers reported engaging in collaborations with counterparts abroad, for example by developing joint ventures or by agreeing to exhibit each other’s artists at different fairs or in their gallery space (5;28). For example, galleries sharing the representation of artists would reach practical arrangements whereby while one gallery travelled and showed the artworks at fairs, the other would take care of production costs and local exhibitions (34).

We live in the twenty-first century. You cannot do anything alone, it's a big world, ah, it's an intense and fast world. The artist needs more people to talk about them, to, to promote them, so it's always a goal to have collaborators. (28)

4.1.2. Extending the brand abroad

Mobility was not just about overcoming physical distance; but it was also part of an active brand-building strategy. For gallerists in particular, being active in the global art market meant “extending the gallery name” and its brand abroad (37), and “reaching the best exposure” for artists and their works (28). An up-and-coming São Paulo gallerist commented on how this had become his full-time job, a continuous effort to “reach the right people” that would help give a boost to their position and that of his team of artists:

It's about what you're willing to build. If you're willing to build a contemporary art primary market gallery, I would say that you have to be proactive. Otherwise, things will take so much longer. It's about being proactive every single day, every single hour, it's about writing to someone that is in Spain, that is in Majorca, in Tokyo or in Oslo and presenting an artist and presenting a piece and presenting an opportunity of acquiring something that is amazing and connects to their collection and everything. This with museums, with curators, with museum directors, with everyone, with collectors. (28)

4.1.3. Being in the right circuit, at the right time

Testing new markets abroad entailed financial risks, but galleries suggested some mitigating strategies. Curated solo shows at art fairs, such as those organized at Frieze Focus “dedicated to fostering a community of the most exciting emerging galleries,”Footnote6 afforded the opportunity to gain some market exposure, without the risks entailed in putting together a consistent artistic team for a bigger and pricier stand (5). Moreover, with the multiplication of art fairs in recent decades, even the smaller art galleries felt they could target an art fair that was commensurable with their status and position in the art market (14,18,27,32,40). This finding resonates with earlier works suggesting that a structural mechanism of homophily appears to guide galleries to participate in art fairs attended by galleries with a similar profile to their own (Yogev and Grund Citation2012). For peripheral market participants, the presence of such homologous market spaces constituted an important resource for reputation and legitimacy building, as it enabled them to marshal the support of similarly predisposed peers and thus enhance their credibility and likelihood of success (see Cattani, Ferriani, and Allison Citation2014). Yet gaining credibility and status abroad was compared to building a “house of cards” (37), a painstaking and delicate process. Building up a CV and choosing the right networks was important because artists and galleries accumulate a history of past associations which helps to build (or tarnish) their reputation (Giuffre Citation1999). This was echoed in my conversations with artists, where any foreign gallery making an approach for an exhibition or representation abroad was thoroughly vetted, if not turned down (12,23,33,72):

You have to be careful where you go. […] It doesn’t matter if it’s London, New York or Paris. It [the exhibition] has to be in a good gallery, a cool gallery. […] The important thing is to be well represented outside of Brazil. (23)

4.1.4. Navigating aesthetic circuits

There is no go-to reference where you can learn. You just have to go and observe, observe, observe, observe, see what they are exhibiting. (8)

Gallerists reflected on how to navigate such aesthetic networks. Aesthetic incompatibilities could be overcome through patience and taking the time to build up connections (22), but also by understanding what to bring where and when (8,12,37), for instance by knowing when a certain artist was ready for international exposure at a particular place and time. Having the same artists represented by different galleries at the same fair was also seen as a win-win situation, whereby everybody benefited from the increased exposure to the artist, helping to “lift” the market (19; see also Fournier and Roy-Valex Citation2002). Some gallerists reported studying the market and offering something unique, for example by “rescuing” Brazilian artists from previous, forgotten, generations (17,18,25,37). For others, taking on already established foreign artists was a way of attracting the attention of foreign buyers and introducing them to the Brazilian market by association (25,29,61). Recounting their experience at ArteBA, the art fair in Buenos Aires, a São Paulo-based gallerist explained how their booth only included Argentinian artists as a way to entice the attention of local collectors (29). Such strategies resonated the search for a shared language and cultural rituals discussed by Hoang (Citation2018) as a mechanism to overcome uncertainty surrounding emerging markets.

4.14. Reaching beyond the diaspora

(Ex)changing the networks in which Brazilian art circulated also triggered reflections on art collectors. Art collectors are seen as having the ability to bestow prestige and legitimacy to their collection through their own reputational capital and social validation, as well as a track record of choosing art “wisely” (Rodner and Thomson Citation2013, 64). My respondents pointed towards perceived inequalities in the legitimating power of collectors along national lines. When it came to extending the market for Brazilian contemporary art abroad, artists and gallerists reported that a sign of their enhanced position and validation in the global art market was their ability to reach beyond the “hardcore” base of support of co-national collectors living abroad (6,15,48). This would sometimes lead them to deny sales to co-nationals abroad in the hope to entice foreign collectors (15). One conceptual artist with a curriculum of exhibitions and sales abroad juxtaposed local to “real collectors” abroad – the latter being considered more likely to have a more extensive knowledge of art and a higher propensity to buy more difficult, conceptual pieces (48). Few Brazilian collectors were seen as having the “power” (29) to buy important international pieces. While the national diaspora constituted a significant part market share abroad, my findings suggest that art market participants perceived that their associations with collectors were subject to unequal status and validation gains along national lines.

Widening one’s network and exposure in different circuits, therefore, affords opportunities to leverage relationships with experts and peers, as important avenues to creating and affirming value through such interactions (Preece, Kerrigan, and O’Reilly Citation2016). Yet building fruitful exchange is only possible if matching partners are found, and with no rulebook at hand, doing so comes with the experience of being in the market, learning and observing peers and reflecting on one’s own position. This leads us to the second way in which the notion of troca was utilized in the field.

4.2. Context (ex)change or troca: adapting the operating context in which art is marketed

Confirming previous research on art market emergence, art market participants reported adapting to and functioning according to widely accepted conventions and practices that are diffused in Europe and North America (Kharchenkova Citation2018; Velthuis and Baia Curioni Citation2015; Brandellero Citation2015). Positioning and valorizing Brazilian art in the international market required adapting the operating context in which Brazilian art is marketed, aligning with shared notions of professionalism and cosmopolitanism. Here two understanding of (ex)change or troca were often paired: participating in the global art market required marketing according to professional standards and practices, and adopting and signalling an open attitude. This involved taking action at the level of individual gallerists and artists, but also stimulating collective efforts, such as those spurred by the Association of gallerists ABACT.

4.2.1. Professionalizing operating practices

The art market, and marketing art, in my view, from my experience, it’s a question of personal credibility. […] If your brand name, if your gallery name resonates, if it is often mentioned, because you have a programme of activities that is known, this facilitates your trajectory, it facilitates contacts, it facilitates the effectuation of sales and so on. And for this you need to gain maturity. You can’t just open a gallery […] and expect a big collector to turn up the next day. (37)

Gallerists who had been active in the market for longer recalled how professionalization went hand in hand with their market development and growth: reflecting on the previous ten years and her gallery’s trajectory, a dealer recalled the transition from more “family structures” to “more structured, entrepreneurial” businesses (8). As a more experienced dealer put it, “the difference nowadays [is that] the way we used to work is not possible anymore, it was easier because we were small and we didn’t have so [many] obligation[s] […] and now we must professionalize” (25, also 8,59). Ultimately, this change also made gallerists’ work easier: reflecting on the impact of the standardization of documentation, invoicing, certificates of authenticity on his business, one gallerist concluded that “it’s very hard to work in a market with no rules” (29). Yet some gallerists resisted the change: they preferred to keep their structures more intimate and familial, foregoing opportunities for strengthen their market abroad (1).

4.2.2. Professionalizing the art market

A professional and formal attitude were discursively explained as helping to stimulate confidence and trust in the market as a whole. The greater the international exposure, the stronger the “responsibility [and the urge to] have a postura [stance, attitude], a behaviour, to go on with all these situations” (25). Fitting into the professional rules of the global market provided a powerful script to allay the fear of risky investments that otherwise stymie an emerging market (Hoang Citation2018). Moreover, it was a preventive measure to avoid being “swallowed up” by the competition (8, 29), something which was made more pressing by the opening of a White Cube branch (since closed) in São Paulo shortly before my fieldwork. The Association of Galleries ABACTFootnote7 was credited by many as playing an active and supportive role in preparing galleries for fairs at home and abroad, helping with applications as well as facilitating networking events and hosting visits by international curators and museum directors (8,17,59). Moreover, ABACT offered advice on accounting, taxation and red tape, in the form of information sessions, publications, while also facilitating networking among members for a more informal support network. This didactic role was generally appreciated: the impression was that while in Brazil, there were few opportunities to learn how to run a gallery through formal training programmes, while counterparts in Europe or the USA could count on more courses and schools.

Art fairs play were considered as important moments to signal and showcase the professionalization of the local art market (see also Fetter Citation2016). Especially higher status gallerists emphasized the significance of such instances of “representation” of the market (59) during which confidence and trust could be strengthened. Local collectors’ own growing awareness of and interaction with European and North American art market participants during international fairs also translates into expectations of a more business-like structure and service at home (3,4,7,8,32,60).Footnote8

4.2.3. Promoting a cosmopolitan art market

I think it is great [having international artists in my gallery], because it signals the importance of culture in the world, in the same way that I want to go abroad [with my artists]. It’s not possible to want to go out of Brazil [with Brazilian artists] and at the same time for Brazil not to open up. It’s a two-way street. (8)

At the same time, signalling openness to international art was seen as a way to reciprocate attention from art market counterparts abroad. Indeed, openness towards art from abroad was seen as going in tandem with enticing foreign interest in Brazilian art (59,25): troca in this context signified that signalling and nurturing an interest in artists from abroad in Brazil (40, 29) was a way to “return the favour” of the attention bestowed upon Brazilian contemporary art (2). As wider communities develop skills, competence and sophistication on Brazilian art, the anticipation was that the value of the artworks would also increase (cf. Joy and Sherry Citation2003; Schau, Muñiz Jr, and Arnould Citation2009) ultimately yielding returns on investment in terms of creating new market opportunities and exchanges with counterparts (see Kuipers Citation2011). Learning about other art markets was credited with “opening minds” (20,59), pre-empting critiques of “provincialism” (6) or insularity (8) that were seen to mar a more inward-looking attitude. Local art collectors were encouraged to train their eye and learn more about foreign art, also through travel and research (29; Brandellero Citation2020). Local gallerists reported that marketing art to local collectors was a combination of commercial and cultural endeavours, entailing “makeshift practices” (Sooudi Citation2016) that sought to develop the local art world, as well as a taste for art, in the context of cultural institutions often lacking the means for stronger interventions (Sooudi Citation2016; Brandellero Citation2020). Travelling outside of Brazil also opened opportunities for cultural exchanges. Artists reflected on the importance of going abroad as a way of exchanging ideas, learning about foreign art and developing a deeper knowledge of art that was fundamental to improving their work:

When you are making art, there is a question of knowledge, that builds up through research in books, trips and so on, and this interexchange is important, this exchange [troca], this thing of travelling to another country, to go to a museum, to learn … Because here in Brazil, we train with books, we don’t have such a strong institutional culture […] for a Brazilian artist, this search for knowledge is important. (12)

is the reason why I am able to welcome you [the interviewer] here today, it is a constant exchange [troca]. It is a way of exchanging culture, of mixing cultures. I believe art is plural and hybrid. It’s obvious that we also hope to be able to place this art in the world and convert into cash, money, so that we can keep working on other projects. (2)

Thus, as an emerging art market, Brazil needed to not only to invest in the development and professionalization of their own local market, but also be more open to exchanges with foreign counterparts and art. The change – or troca – in art market professional practices and the signalling of openness to ideas and art from abroad were indeed crucial to creating (trust in) the market and its capacity to sustain and reciprocate growing international interest and demand.

4.3. Value (ex)change or troca: negotiating values and readings of Brazilian contemporary art in the global art market

Extending the circuits and networks in which Brazilian art circulates confronts art market actors with the ontological question of how Brazilian art is defined and valued in the global art market. Respondents reported how they negotiated the tension between incommensurable readings and valuations of Brazilian art. They also reflected on the underlying power differentials that they experienced, as well as on their individual and collective agency to redress them.

4.3.1. Negotiating values in an unequal playing field

They are consecrated [Adriana Varejão and Beatriz Milhazes, two of the most highly renowned Brazilian contemporary artists], but there are double standards. A consecrated English artist is worth 20 million. A consecrated Brazilian [artist] is worth two million. (7)

Respondents lamented a lack of knowledge of or limited experience with Brazilian art and its rich history (12,43). As the gallerist quoted above said, such limited knowledge was more often perceived as a power differential rather than an aesthetic or artistic question. The power differentials inspired some to engage in a struggle to resist and to generate own narratives and validation (43,77), while ensuring Brazilian art’s rightful place in global art history (50,15,20).

Various proactive solutions to tackle these shortcomings were envisaged by gallerists, curators and artists. Books and publications on Brazilian art in English were seen as playing an important role in “doing the groundwork” (29), and ABACT had recently sponsored a publication on Brazilian contemporary artists. Beyond collective projects, a gallerist told me about the importance of getting people talking about Brazilian artists, taking on a “storyteller” role (28). Another gallerist emphasized the need to “coach a relation to the country” and its art (25). As Preece and Kerrigan (Citation2015) argued, artistic careers are co-created through the interaction of different stakeholders and relationships that add value to artistic brands. My findings suggest that participants from art markets considered emergent encounter an unequal playing field when extending their market internationally, as they experience that local socialization and cultural, economic and social value attributions do not necessarily translate into commensurable global recognition.

4.3.2. Agenda-setting in a “colonised market”

The question of diverse value attributions and gatekeeper and audience priorities in Brazilian and global art worlds raised some critical considerations. A museum curator articulated the concern that the Brazilian art market was operating as a “colonised market” in which participants were “not trusting their own opinion” enough (35). Similar concerns were signalled by artists and gallerists (12,17,29,52) who bemoaned what they experienced as a “colonized country syndrome” (12). This dynamic was seen as working in two ways. Firstly, international validation and recognition was seen by some as trumping local consecration. The attention bestowed upon the Brazilian art market by foreign market actors and curators was seen as endowing the Brazilian contemporary art market with a greater sense of security, offering an “extra guarantee” of the value (25,17) and “quality” (14), while also boosting the confidence of local collectors (29) and offering a “shortcut” to national success (52). While diffusion of branding on the international art market is often seen as the pinnacle of a process beginning with local and national visibility (Rodner and Preece Citation2016), my data shows a feedback loop whereby international visibility could serve to strengthen credibility and branding locally.

Secondly, international validation and recognition were seen as influencing agenda-setting in local consecration and endorsement processes. As a curator expressed:

It’s not an agenda we conquered [referring to the international attention to Brazilian contemporary art]. It’s an agenda that is being made […]. But then there is this attention to Brazil, and to America, and to the BRICs, and this attention starts getting, highlighting subjects, highlighting people, highlighting careers and then these people are getting more and more opportunities and being recognized as Brazil. This is still a very unbalanced game. (77)

is not creating a Brazilian art history that is external to our history. It’s not that it has no historical value, but it creates a vision that becomes accepted here. […] We have to maintain an equilibrium and not be led by an international agenda of artists that are successful [abroad]. (43)

This show [in the New York Museum of Modern Art] wasn’t done because of my stature in Brazil, it was done because they saw my work […]. So they have experienced it first-hand [at the São Paulo Biennial], it wasn’t something that was mediated by anyone. (6)

4.3.3. Managing and countering expectations and stereotypes

Such agenda-setting influence of international gatekeepers raised concerns. For some, international attention to Brazilian contemproary art was experienced as focusing on a “limited repertoire” – a particular “globalized vision of Brazilian art” (43). Similarly to Rodner and Preece’s (Citation2016) findings, art market participants regretted an emphasis on a collective identity of Brazilian art, often experienced through “cultural stereotypes” reproduced in Brazilian or Latin American group shows abroad. Such collectivist tendency focused on particular aesthetics and materialities, a brand image of Brazilian art that included bright colour palettes, exoticism, tropicalism, simple or natural materials, precarity, urban and political topics (24,32,47,48,52). One artist told of how she and two other artists had refused to attend the opening of a group exhibition of Brazilian contemporary art of which they were part, because a samba group had been invited to the event (48): “That’s why it was so important for me to be part of international shows that weren’t Brazilian art shows, “cuz then I could really just be my work, just me!.” As a teacher as well, she rather cynically lamented the influence of what she described as “rules” on how to be a successful Brazilian artist abroad on the younger generations of artists:

You have to be precarious, you do, you work with cheap materials, you do slightly, ah, very, very subtle interferences and […] you have a discourse of modernity and the […] fail[ure] of utopia and tataam you are there. It’s just like that. That’s why there are so many young artists that are hipsters of the moment in Brazil, because it’s so easy to do what foreigners want from us. (48)

4.3.2. Being part of the “global art” world

I think we are part of the globe, but the globe does not really perceive you, you know. I think the segmented areas [are] very dangerous in the art world, and I think it is something created by the centre of the world, because they didn’t look at what’s around, and this is much more politic[al] than artistic problem, you know? (59)

The findings showed that imaginaries of collective identities, as framed in group shows along national lines for example, offered opportunities for visibility abroad. Yet art market participants sought to “strike a balance” between managing external expectations of collective identity in an unequal playing field, and developing their own independent identity in a borderless art world. This was achieved by not complying to expectations and perceived rules, but also by sharing knowledge and alternative readings of Brazilian art, emphasizing the importance of personal relationships and partnerships in wider social circuits.

5. Discussion

This paper sheds light on the experience of market emergence in an unequal field, by looking at how Brazilian art market participants position themselves in the global art market. It answers the following research question: how do art market participants from an art market considered emergent experience and enhance their positioning in the global art market? Previous studies of art market emergence have generally been focused on how art from emerging markets fares in European and North American-dominated hierarchies and reference frameworks (Banks Citation2018; Buchholz Citation2018; Buchholz and Wuggenig Citation2005; Quemin Citation2013; Velthuis and Baia Curioni Citation2015). These studies have highlighted the persisting inequalities in the art market, as showcased through auction results or global rankings for instance, which tend to be dominated by European or North American artists. This paper has advocated for a more fine-grained approach to the study of globalization in the art market, one that accounts for how individual art market participants navigate the “the macro-level context in which [art] is produced, distributed, and consumed” (Rodner and Preece Citation2016, 128), and how they reflect on their own and collective agency when reflecting on their position-taking and validation. In so doing, this paper adds to our understanding of art marketing in a global perspective, by focusing on how art market participants aimed to improve their own status and position, while navigating a transnational field characterized by power and resource differentials.

The findings show how successful market emergence is experienced as the practice of troca, meaning (ex)change, on three levels: networks, context, and values.

The first level of troca concerns network (ex)change: positioning Brazilian art in the global art market entailed extending the social networks and circuits in which it is placed. In a literal sense, it involved overcoming a sense of peripherality through carefully planned physical mobility, notably through art fair participation. Mobility created opportunities for exposure to and exchanges with international “cogs” in the art machine (see Rodner and Thomson Citation2013). Knowing where, when and how to extend international networks self-reflection, extensive research and observation, and patience – avoiding trial and error and reputational faux-pas. “Fitting in” and “standing out” (Parmentier, Fischer, and Reuber Citation2013) required understanding what would work and resonate in different circuits and international settings, calibrating efforts to desired outcomes. Indeed placing art in international circuits could afford status gains and windfalls, yet financial and time investments were required. Moreover, certain networks afforded more status gains than others, as noted in the ambivalent discussion of the role of the Brazilian diaspora in enhancing legitimation of Brazilian contemporary art abroad. Contributing to art marketing literature that views value creation in the art market as occurring in an ecosystem of relationships (Rodner and Thomson Citation2013), this research shows how such relationships are spatially refracted. Position gains in a national context required renegotiation in a global “multi-scalar architecture” of relationships (Buchholz Citation2016), as respondents encountered different circuits with their own logics of access, competition and aesthetic receptivity to the contemporary art on offer. My findings lend credence to prior research that has theorized the co-construction of value in the visual arts as “dispersed, situational, and in-flux” (Preece, Kerrigan, and O’Reilly Citation2016, 1377), while attending to the strategies and resources that participants deployed to enhance their chances of success in particular places and at particular times.

The second level of troca concerned context (ex)change: position-taking in the global art market also involved changes to the participants’ operating context, notably by adapting professional practices and adopting a more open and cosmopolitan stance. Such contextual changes were seen as congruent with gains in individual and collective market trust and credibility, as well as greater reciprocity in international transactions. Previous research has noted how market emergence is achieved through a collective and normative push to professionalize and formalize practices around widely accepted standards (DiMaggio and Powell Citation1991). In my research, the professionalization of local operating practices – e.g. how to run a gallery, set up a stand at a fair – were at once necessary for growth and desirable, signalling the belonging to the global art market. The practice of troca also meant opening up to international counterparts in a cosmopolitan market, reciprocating their attention to Brazilian contemporary art. Expanding the global art market share of Brazilian art went hand in hand with growing local demand for art more generally, irrespective of its country of origin. This reciprocity worked on two levels: on the one hand, it helped to place Brazilian art in a more international context at home; on the other, it served to signal the market’s maturity. While participants discussed how they could play their individual part in adapting the market context, emerging structures such as the gallery association ABACT provided fora to develop organizational alignment and market openness further.

The third level of troca concerned values (ex)change: enhancing the positioning of Brazilian contemporary art required changes to the values attributed to it in an international context. Respondents contended with the fact that Brazilian contemporary art is relatively less visible and valorized internationally relative to its quality and compared to more hegemonic national art markets (see Quemin Citation2013). Moreover, some voiced concerns of a “colonized market,” whereby local validation processes were experienced as being increasingly influenced by how contemporary artists resonated in the global art market. This raised concerns about the scope for local curators and cultural institutions to set their own agenda, and contribute to cultural branding of the Brazilian art world, autonomously from international attention and success. On the level of artistic production, art market participants contended with two seemingly conflicting art discourses, that shaped the opportunities for Brazilian contemporary art to “fit” into the global art market. One discourse reproduced a dominant cultural branding imaginary, involving particular aesthetics and framings of Brazilian art embedded in Western legitimation structures and ecosystems (see Robertson Citation2011). This discourse resulted in the diffusion of self-orientalising practices in the local art world, whereby artistic production would be made in response to demands for exoticized aesthetics. In contrast, a “global art” discourse upheld deterritorialized reading of artistic production and cultural branding, which transcended national boundaries. Opening up the global art market to Brazilian contemporary art involved confronting particular global art and cultural branding paradigms, that could support or hinder the validation of particular works (Robertson Citation2011; Rodner and Preece Citation2016).

Summarizing, this paper contributes to extant art marketing literature in various ways. First and foremost, it enriches to our understanding of the “art machine” as an interlocking set of actors and stages that together operate “in the cooperative (if not competitive) construction of symbolic and financial value” (Rodner and Thomson Citation2013, 67). It does so by accounting for a situation in which art market participants work across diverse spatial settings and status hierarchies, effectively negotiating multiple strata of the art machine. In so doing they contend with the unequal distribution of power in the global art world, whereby more central (both in terms of status and location) muster a greater ability to shape the symbolic and financial value of art. Extending Rodner and Preece’s (Citation2016) analysis of the interrelated spheres of art branding to encompass a global setting, my research shows how my respondents perceived their global art market counterparts as having the power to shape individual artist branding by setting out a particular “globalised vision of Brazilian art” (for example, by reproducing particular exoticized framings of Brazilian contemporary art in group shows, or by favouring particular aesthetics). Following such vision might accrue positioning gains, but at a cost of artistic autonomy. Respondents also reflected on how global art market gatekeepers’ wielded the ability to “take their pick” and bestow international visibility, with ripple effects on the national artworld level and cultural branding. Hence my findings show how the diffusion process of brand identities among gatekeepers and audiences in international settings entails managing diverse priorities and cultural, social and economic values, while negotiating in a condition of differential agenda-setting powers (Preece and Kerrigan Citation2015).

Moreover, this paper, deconstructs the negotiation of positioning in the transition from local to global art machine, as involving three interdependent levels of (ex)change (see ). Changing and widening the circuits in which Brazilian contemporary art circulated went hand in hand with adapting the operating context. This was out of necessity (e.g. being able to cope the organizational requirements of art fair participation abroad) but also connected to isomorphic tendencies in the global art market, where access to certain circuits was dependent on adapting to shared market standards. Widening networks for and changing values of Brazilian contemporary art had a reciprocal relationship too. Networks were valuable for spreading and enhancing knowledge about Brazilian contemporary art amongst counterparts – while by access to position-enhancing connections and interdependencies with international counterparts was also dependent on negotiating value hierarchies and boosting the appreciation of Brazilian art in the global art market. Such interdependencies triggered reflections on the individual agency of Brazilian art market participants and structural changes required to counter power inequalities. While some well-heeled galleries could mobilize time and financial resources to develop their circuit and promote Brazilian art in the global art market, they also experienced an unequal level playing field, whereby transnational curators and hegemonic institutions could exert more power in filtering access to more exclusive arenas of association. Meanwhile, smaller and less endowed galleries reflected on how they struggled to “fit into” even the local art fairs, as they were becoming more competitive and internationally-oriented.

This research occurred at a time of greater optimism and growth, with the prospect of two major sport events firmly placing Brazil in the global art market imaginary. Since then, the political and economic situation of the country has evolved. Recent developments suggest that a number of galleries are recentering their activities of some galleries outside of Brazil, might constitute a next stage in art market consolidation. A number of blue chip art dealers have in fact opened spaces in Brussels, Lisbon, Miami and New York (Fialho Citation2019). The São Paulo gallery Mendes Wood DM opened an exhibition space in New York in 2017, followed by a space in Brussels. The latter is also conceived as an artistic residency.Footnote9 These developments involve art dealers with greater financial or symbolic capital, and the motivations for setting up and diversifying their international presence is intriguing. Further research could benefit from a richer and more in-depth narrative analysis of fewer cases, in order to gain insights into how present-day choices are contextualized in relation to past practices and strategies. Moreover, additional comparative cases could help to shed more light on the impact of “globalized readings of art” on local value co-creation ecosystems, tracing the influence of perceived dominant readings on current artistic production, styles and techniques.

Acknowledgements

The author also wishes to acknowledge the helpful feedback of the journal Editors and three anonymous reviewers, as well as Marc Verboord, Kees van Rees, Olav Velthuis and the “Culture Club” at the Sociology department of the University of Amsterdam, as well as participants at the TIAMSA “The art market and the global South” conference.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Amanda Brandellero

Amanda Brandellero is Associate Professor at the Erasmus School of History, Culture and Communication, at Erasmus University Rotterdam. Her research focuses on cultural and artistic production and marketing in urban settings, attending to questions of cultural globalization and sustainability.

Notes

1 According to the art market study commissioned by the Association of Brazilian Art Galleries ABACT in 2015, the year 2013 was marked by a spike in art market exports (see ABACT Citation2015, 35).

3 Mapa das Artes is now available online at: https://www.mapadasartes.com.br/#!/home.

4 I also had informal conversations with early career artists with no gallery representation.

5 The numbering is based on the archiving of the interview transcripts. Since more interviews were conducted than are used in this article, this explains why some interview codes have a number higher than the total number of interviews used in this study.

7 At the time of my fieldwork, ABACT had a secretariat with employed staff, as well as an executive board including representatives from member galleries.

8 Undoubtedly, and particularly for some of the longer standing galleries, opening up to the global market was contextualized against a history of dictatorship, from which the country emerged in the mid-1980s.

9 Source: http://mendeswooddm.com/en/info, last accessed 28 February 2020.

References

- ABACT. 2015. Sectoral Study. The Contemporary Art Market in Brazil. Fourth Edition. Accessed February 25, 2020. http://www.latitudebrasil.org/pesquisa-setorial/.

- Abolafia, M. Y. 1998. “Markets as Cultures: An Ethnographic Approach.” The Sociological Review 46 (1_suppl): 69–85.

- Aspers, P. 2009. “Knowledge and Valuation in Markets.” Theory and Society 38 (2): 111–131.

- Banks, P. A. 2018. “The Rise of Africa in the Contemporary Auction Market: Myth or Reality?” Poetics 71: 7–17.

- Basbaum, R. 2013. Manual do artista-etc. Rio de Janeiro: Beco do Azougue.

- Bathelt, H., and J. Glückler. 2014. “Institutional Change in Economic Geography.” Progress in Human Geography 38 (3): 340–363.

- Becker, H. 1982. Art Worlds. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Beckert, J. 2009. “The Great Transformation of Embeddedness: Karl Polanyi and the new Economic Sociology.” In Market and Society: The Great Transformation Today, edited by C. Hann and K. Hart, 38–55. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Beckert, J. 2010. “How do Fields Change? The Interrelations of Institutions, Networks, and Cognition in the Dynamics of Markets.” Organization Studies 31 (5): 605–627.

- Belting, H. 2013. “Contemporary art as Global art. A Critical Estimate.” In The Global Contemporary and the Rise of new art Worlds, edited by H. Belting, A. Buddensieg, and P. Weibel, 38–73. Karlsruhe, Germany: ZKM/Center for Art and Media; Cambridge, MA: London, England: The MIT Press.

- Bourdieu, P. 1977. Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. 1984. Distinction. Translated by Richard Nice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Brandellero, A. 2015. “The Emergence of a Market for Art in Brazil.” In Cosmopolitan Canvases: The Globalization of Markets for Contemporary Art, edited by Olav Velthuis and Stefano Baia Curioni, 215–237. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Brandellero, A. 2020. “Inside and Outside the Market for Contemporary Art in Brazil, through the Experience of Artists and Gallerists.” Arts 9 (11): 1–16.

- Brandellero, A., and O. Velthuis. 2018. “Reviewing Art from the Periphery. A Comparative Analysis of Reviews of Brazilian Art Exhibitions in the Press.” Poetics 71: 55–70. doi:10.1016/j.poetic.2018.10.006.

- Buchholz, L. 2016. “What is a Global Field? Theorizing Fields Beyond the Nation-State.” The Sociological Review 64 (2_suppl): 31–60.

- Buchholz, L. 2018. “Rethinking the Center-Periphery Model: Dimensions and Temporalities of Macro-Structure in a Global Field of Cultural Production.” Poetics 71: 18–32.

- Buchholz, L., and U. Wuggenig. 2005. Cultural Globalization Between Myth and Reality: The Case of the Contemporary Visual Arts. Art-e-Fact Strategies of Resistance, Glocalogue (04).

- Bulhões, M. A., B. Fetter, and N. Vargas da Rosa. 2018. Arte além da arte. Anais do primeiro simpósio internacional de relações sistêmicas da arte. Porto Alegre: Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul. https://1simposioirsablog.wordpress.com/.

- Callon, M., C. Méadel, and V. Rabeharisoa. 2002. “The Economy of Qualities.” Economy and Society 31 (2): 194–217.

- Cattani, G., S. Ferriani, and P. D. Allison. 2014. “Insiders, Outsiders, and the Struggle for Consecration in Cultural Fields: A Core-Periphery Perspective.” American Sociological Review 79 (2): 258–281.

- Crane, D. 2002. “Culture and Globalization: Theoretical Models and Emerging Trends.” In Global Culture: Media, Arts, Policy, and Globalization, edited by D. Crane, N. Kawashima, and K. Kawasaki, 1–25. London: Routledge.

- Crane, D. 2009. “Reflections on the Global art Market: Implications for the Sociology of Culture.” Sociedade e Estado 24 (2): 331–362.

- Currid, E. 2007. “How art and Culture Happen in New York: Implications for Urban Economic Development.” Journal of the American Planning Association 73 (4): 454–467.

- Dicken, P., P. F. Kelly, K. Olds, and H. Wai-Chung Yeung. 2001. “Chains and Networks, Territories and Scales: Towards a Relational Framework for Analysing the Global Economy.” Global Networks 1 (2): 89–112.

- DiMaggio, P. 1988. “Interest and Agency in Institutional Theory.” In Research on Institutional Patterns: Culture and Environment, edited by L. G. Zucker, 3–21. Cambridge: Ballinger Publishing Company.

- DiMaggio, P., and W. Powell. 1991. “The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields’.” In The new Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis, edited by W. Powell and P. DiMaggio, 63–82. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Durand, J. C. G. 1989. Arte, privilégio e distinção: artes plásticas, arquitetura e classe dirigente no Brasil, 1855/1985(Vol. 108). Editora Perspectiva.

- Fetter, B. W. 2016. Narrativas conflitantes e convergentes: as feiras nos ecossistemas contemporâneos da arte. Doctoral dissertation. Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul. Instituto de Artes. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Artes Visuais.

- Fialho, A. L. 2019. “Mercado de arte global, Sistema desigual.” Revista do Centro de Pesquisa e Formaçao 9: 8–41.

- Fioravante, C. 2001. O marchand como curador. São Paulo: Casa das Rosas.

- Fligstein, N. 2001. The Architecture of Markets: An Economic Sociology of Twenty-First-Century Capitalist Societies. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Fligstein, N., and D. McAdam. 2011. “Toward a General Theory of Strategic Action Fields.” Sociological Theory 29 (1): 1–26.

- Fournier, M., and M. Roy-Valex. 2002. “Art contemporain et internationalisation: les galeries québécoises et les foires.” Sociologie et Sociétés 34 (2): 41–62.

- Friedland, R., and R. R. Alford. 1991. “Bringing Society Back in: Symbols, Practices, and Institutional Contradictions.” In The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis, edited by W. W. Powell, and P. J. DiMaggio, 223. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Giuffre, K. 1999. “Sandpiles of Opportunity: Success in the art World.” Social Forces 77 (3): 815–832.

- Glaser, B. G., and A. L. Strauss. 2017. Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. London: Routledge.

- Hesmondhalgh, D. 2012. The Cultural Industries. London: SAGE.

- Hoang, K. K. 2018. “Risky Investments: How Local and Foreign Investors Finesse Corruption-Rife Emerging Markets.” American Sociological Review 83 (4): 657–685.

- Janssen, S., G. Kuipers, and M. Verboord. 2008. “Cultural Globalization and Arts Journalism: The International Orientation of Arts and Culture Coverage in Dutch, French, German, and US Newspapers, 1955 to 2005.” American Sociological Review 73 (5): 719–740.

- Jensen, R. 1996. Marketing Modernism in fin-de-siècle Europe. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Joy, A., and J. Sherry. 2003. “Disentangling the Paradoxical Alliances Between art Market and art World.” Consumption, Markets and Culture 6 (3): 155–181.

- Joy, A., and J. Sherry. 2004. “Framing Considerations in the PRC: Creating Value in the Contemporary Chinese art Market.” Consumption Markets & Culture 7 (4): 307–348. doi:10.1080/1025386042000316306.

- Juneja, M. 2011. “Global art History and the ‘Burden of Representation.” In Global Studies: Mapping Contemporary Art and Culture, edited by H. Belting and J. T. S. Binter, 274–297. Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz.

- Kharchenkova, S. 2018. “The Market Metaphors: Making Sense of the Emerging Market for Contemporary art in China.” Poetics 71: 71–82.

- Knott, B., A. Fyall, and I. Jones. 2015. “The Nation Branding Opportunities Provided by a Sport Megae-Event: South Africa and the 2010 FIFA World Cup.” Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 4 (1): 46–56.

- Komarova, N., and O. Velthuis. 2018. “Local Contexts as Activation Mechanisms of Market Development: Contemporary art in Emerging Markets.” Consumption Markets & Culture 21 (1): 1–21.

- Kraeussl, R., and R. Logher. 2010. “Emerging art Markets.” Emerging Markets Review 11 (4): 301–318.

- Kuipers, G. 2011. “Cultural Globalization as the Emergence of a Transnational Cultural Field: Transnational Television and National Media Landscapes in Four European Countries.” American Behavioral Scientist 55 (5): 541–557.

- Kuipers, G. 2015. “How National Institutions Mediate the Global: Screen Translation, Institutional Interdependencies, and the Production of National Difference in Four European Countries.” American Sociological Review 80 (5): 985–1013.

- Leca, B., and P. Naccache. 2006. “A Critical Realist Approach to Institutional Entrepreneurship.” Organization 13 (5): 627–651.

- Lizardo, O. 2012. “Culture and Stratification.” In Handbook of Cultural Sociology, edited by John R. Hall, Laura Grindstaff, and Ming-Cheng Lo, 305–315. London: Routledge.

- Lopes, F. 2009. A experiência Rex. “Éramos o time do Rei”. São Paulo: Alameda.

- Maguire, S., C. Hardy, and T. B. Lawrence. 2004. “Institutional Entrepreneurship in Emerging Fields: Hiv/AIDS Treatment Advocacy in Canada.” Academy of Management Journal 47 (5): 657–679.

- McAndrew, C. 2012. TEFAF Art Market Report. Maastricht, TEFAF.

- Morais, F. 1996. “Petite Galerie.” In Petite Galerie. Uma visão da arte brasileira, edited by Paço Imperial, 49–55. Rio de Janeiro: Paço Imperial.

- Morgner, C. 2014a. “The Art Fair as Network.” The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society 44 (1): 33–46.

- Morgner, C. 2014b. “The Evolution of the Art Fair.” Historical Social Research/Historische Sozialforschung 39 (3): 318–336.

- Parmentier, M. A., and E. Fischer. 2021. “Working it: Managing Professional Brands in Prestigious Posts.” Journal of Marketing 85 (2): 110–128.

- Parmentier, M. A., E. Fischer, and A. R. Reuber. 2013. “Positioning Person Brands in Established Organizational Fields.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 41 (3): 373–387.

- Plattner, S. 1996. High art Down Home: An Economic Ethnography of a Local art Market. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Podolny, J. 1990. “On the Formation of Exchange Relations in Political Systems.” Rationality and Society 2 (3): 359–378.

- Power, D., and J. Jansson. 2008. “Cyclical Clusters in Global Circuits: Overlapping Spaces in Furniture Trade Fairs.” Economic Geography 84 (4): 423–448.

- Preece, C., and F. Kerrigan. 2015. “Multi-stakeholder Brand Narratives: An Analysis of the Construction of Artistic Brands.” Journal of Marketing Management 31 (11-12): 1207–1230.

- Preece, C., F. Kerrigan, and D. O’Reilly. 2016. “Framing the Work: The Composition of Value in the Visual Arts.” European Journal of Marketing 50 (7/8): 1377–1398.

- Quemin, A. 2013. “International Contemporary art Fairs in a ‘Globalized’art Market.” European Societies 15 (2): 162–177.

- Robertson, I. 2011. A New Art from Emerging Markets. Surrey: Lund Humphries.

- Rodner, V. L., and C. Preece. 2016. “Painting the Nation: Examining the Intersection Between Politics and the Visual Arts Market in Emerging Economies.” Journal of Macromarketing 36 (2): 128–148.

- Rodner, V. L., and E. Thomson. 2013. “The art Machine: Dynamics of a Value Generating Mechanism for Contemporary art.” Arts Marketing: An International Journal 3 (1): 58–72.

- Schau, H. J., A. M. Muñiz Jr, and E. J. Arnould. 2009. “How Brand Community Practices Create Value.” Journal of Marketing 73 (5): 30–51.

- Sidaway, J. D., and M. Pryke. 2000. “The Strange Geographies of ‘Emerging Markets’.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 25 (2): 187–201.

- Sooudi, O. K. 2015. “Morality and Exchange in the Mumbai Contemporary Art World.” In Cosmopolitan Canvases: The Globalization of Markets for Contemporary Art, edited by O. Velthuis, and S. Baia Curioni, 264–284. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Sooudi, O. K. 2016. “Making Mumbai's Emerging Art World Through Makeshift Practices.” South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies 39 (1): 149–166.

- Storbacka, K., and S. Nenonen. 2011. “Scripting Markets: From Value Propositions to Market Propositions.” Industrial Marketing Management 40 (2): 255–266.

- Tejo, C. 2018. Guia do artista visual: inserçao e internacionalizaçao. Brasília: UNESCO/Ministério da Cultura. http://www.cultura.gov.br/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Guia-do-artista-visual.pdf.

- Thornton, P. H., and W. Ocasio. 1999. “Institutional Logics and the Historical Contingency of Power in Organizations: Executive Succession in the Higher Education Publishing Industry, 1958–1990.” American Journal of Sociology 105 (3): 801–843.

- Veblen, T. [1899] 2007. The Theory of the Leisure Class. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Velthuis, O. 2007. Talking Prices: Symbolic Meanings of Prices on the Market for Contemporary Art. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Velthuis, O. 2013. “Globalization of Markets for Contemporary art: Why Local Ties Remain Dominant in Amsterdam and Berlin.” European Societies 15 (2): 290–308.

- Velthuis, O., and S. Baia Curioni, eds. 2015. Cosmopolitan Canvases: The Globalization of Markets for Contemporary Art. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- White, H. C., and C. A. White. 1965. Canvases and Careers: Institutional Change in the French Painting World: With a New Foreword and a New Afterword. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.